Introduction

2021 seemed like a year of parallel universes during which the government engaged in further reconstructing of the Hungarian institutional framework, focusing on education and culture and carefully constructing its new campaign strategy that incorporates targeting the LGBTQ community, while opposition parties negotiated ways to cooperate before the upcoming election in 2022.

Election report

There were no major elections in 2021.

Cabinet report

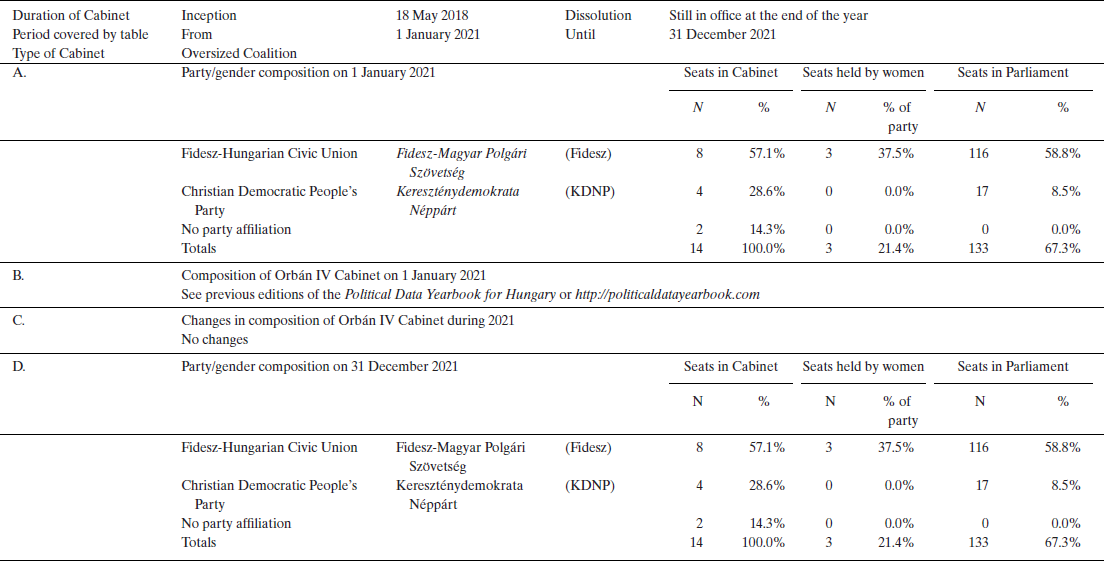

The working of the Hungarian government in 2021 was very similar to the previous year, as no major changes occurred in its structure and personnel (Table 1) and the Cabinet continued to operate in a state of emergency. Following the first and second states of emergency initiated in 2020, the government declared a new, third state of emergency in February 2021, and Parliament adopted the Third Authorization Act (Act I of 2021 on the Containment of the Coronavirus Pandemic) allowing the government to rule by decrees to a much greater extent compared with non-emergency times (for an extensive overview of Hungary's emergency regimes, see Hungarian Helsinki Committee, 2022). The Orbán government did indeed use the opportunity: in 2021, 832 government decrees were adopted, which signals a significant increase when compared with the 2019 pre-emergency state year when only 371 government decrees came into effect. Not only the number but also the proportion of decrees rose as they represented more than half of all the adopted legislation in 2021. While increased legislative activity is expected during times of crisis, only 244 out of the 832, so approximately 30 per cent, of government decrees allude to the state of danger directly (data retrieved from Jogtar, 2022), which signals that the lack of oversight allowed the government to extend its legislative power during this period.

Table 1. Cabinet composition of Orbán IV in Hungary in 2021

Sources: Website of the Hungarian government, 2022, www.kormany.hu; and website of the Hungarian National Assembly, 2022, www.parlament.hu.

Parliament report

The strengthening of the executive power resulted in the loss of parliamentary capacity of legislation and oversight. As Bolleyer and Salát (Reference Bolleyer and Salát2021) have demonstrated in their comparative European study, the Hungarian Parliament's policymaking power was removed in the context of the crisis. Their analysis also pointed out that the emergency procedures adopted during the COVID-19 crisis became applicable in other type of emergencies, and thus remain a fixture in the Hungarian legal system. While opposition parties kept on thematizing this issue on the parliamentary floor, no juridical steps were taken against it.

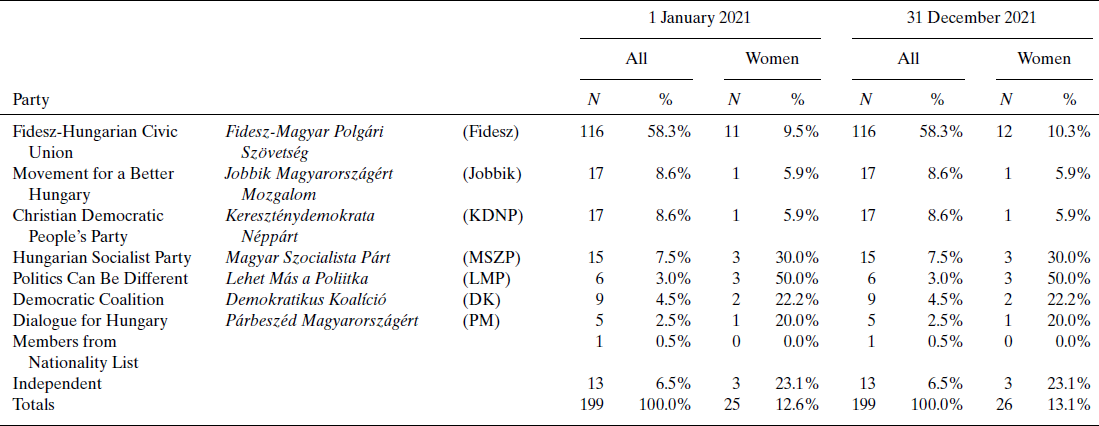

For data on the composition of the Hungarian Parliament, see Table 2.

Table 2. Party and gender composition of the Parliament (Magyar Országgyűlés) in Hungary in 2021

Source: Official website of the Hungarian National Assembly, www.parlament.hu, 2022.

Political party report

During the last election in 2018, it became clear that cooperation between opposition parties was not only necessary under the current electoral system but also desired by voters who initiated a tactical vote campaign in single-member districts (SMDs) where several opposition candidates ran last time. Thus, the decision by opposition parties – namely Democratic Coalition/Demokratikus Koalíció (DK), The Movement for a Better Hungary/Jobbik Magyarországért Mozgalom (Jobbik), Politics Can Be Different/Lehet Más a Poliitka (LMP), the Hungarian Socialist Party/Magyar Szocialista Párt (MSZP), Momentum and Dialogue for Hungary/Párbeszéd Magyarországért (PM) – to create a joint party list, a joint programme and to nominate a joint candidate in each district, as well as for the prime ministerial position, was welcomed at the end of 2020 by opposition voters. While the political will was clearly present, the parties were still rivals in many respects, which prompted lengthy negotiations to agree on the rules of cooperation. Organizing primaries as a means to choose joint candidates had already been tested, and succeeded, at the 2019 mayoral race in Budapest, so parties opted for a similar framework. By the end of the summer of 2021, the parties agreed on the basic rules of the primaries, which were the following: a primary was organized in all SMDs with first-past-the-post voting. Not only were members of the opposition alliance allowed to run, as the race was open to nominees from other parties and to independent candidates (if they succeeded in collecting the necessary 400 signatures for running and signed an agreement with one of the alliance members about joining their parliamentary group if elected). Parallel to the election of single-member-constituency candidates, a nationwide, two-round primary for electing the prime ministerial candidate was launched. The first round of primaries was organized between 18 and 28 September, while the second was between 10 and 16 October. As the current Hungarian electoral system is a mixed system, the opposition parties decided to create a common party list as well, but it was not to be defined by voters in primary elections but by the parties themselves. Voting was possible both in person and online at the primaries.

At the prime ministerial race, five candidates ran: the DK nominated Klára Dobrev, who served as a Member of the European Parliament and is also wife of Ferenc Gyurcsány, ex-Prime Minister of Hungary and a rather controversial figure in the Hungarian political sphere. Jobbik nominated its party leader Péter Jakab as well; the Momentum Movement/Momentum Mozgalom nominated András Fekete-Győr, president of the party, as the prime ministerial candidate. Gergely Karácsony, Mayor of Budapest, entered the race with the support of PM, LMP and MSZP. Péter Márki-Zay was the only non-partisan candidate running, supported by the Everyone's Hungary Movement/Mindenki Magyarországa Mozgalom, a movement that served as a framework of cooperation for many non-partisan candidates, often coming from a civil background.

As for the SMD candidates, the official nomination period started at the end of July, but some opposition parties had begun negotiations about joint nominations before that point. The PM and MSZP were the first to announce that they would only nominate joint candidates, while other parties such as DK and Jobbik did not make such public statement but still withdrew candidates to support each other in numerous cases. Depending on the constituency and candidates, there were SMD primaries where only one party-supported candidate run at the first round (11 per cent of constituencies), and the proportion of SMDs where only two party-supported candidates were nominated was just shy of 50 per cent (Gyimesi, Reference Gyimesi2021).

According to the Budapest-based think-tank 21 Kutatóintézet (2021), 634,000 participants were involved in the first round of the primary elections, making up 8 per cent of all eligible voters. This can be considered a success even compared with international results. The report also argues that the campaign increased the visibility of the candidates as well as the opposition parties, although mobilization was much more effective in Budapest than in the countryside (21 Kutatóintézet 2021: 4–5). Tóka and Popescu paint a similar skewed picture by stating that volunteer efforts were greater in urban areas, where it was also easier to vote, and that while the online media sphere offered surprisingly insightful campaign materials, traditional media outlets were dismissive of the campaign (Tóka & Popescu Reference Tóka and Popescu2021: 680–681). While the online voting system was closed down during the first two days due to technical difficulties, at the end about 20 per cent of voters voted online.

In terms of SMD candidates, the DK won 30 per cent of constituencies, while Jobbik won 27 per cent, MSZP won 17 per cent, Momentum in 14 per cent, PM in 7 per cent and LMP in 5 per cent. As for the prime ministerial candidates, Klára Dobrev gained most of the votes (35 per cent) followed by Gergely Karácsony (27 per cent) and Péter Márki-Zay (20 per cent). The third place of Péter Márki-Zay was a surprise, since Péter Jakab (Jobbik) was expected to perform much better than his 14 per cent, having been the most popular politician on social network sites. András Fekete-Győr also delivered a negative surprise, winning only 3 per cent of votes for Momentum. The rules of the prime ministerial race allowed for three candidates to proceed to the second round in case they reached at least 15 per cent of the votes. Despite having three places in the run-off, Karácsony and Márki-Zay were under great pressure to negotiate their support for each other and a potential withdrawal, as Dobrev was considered a risky candidate due to her closeness to former Prime Minister Ferenc Gyursány. Karácsony announced his withdrawal rather abruptly, leaving Márki-Zay as the wild-card candidate in the race. The second round of voting, which mobilized even more voters, was won by Márki Zay, who became in charge of leading the opposition to the 2022 general elections.

The self-proclaimed conservative Márki-Zay was believed to be capable of addressing non-left-wing voters as well as mobilizing opposition voters based on the credentials of the primaries. Lacking the support of established opposition parties seemed to undermine his leading position, as he struggled to reach a compromise on the joint party list and on the joint programme of the opposition during the fall of 2021.

Institutional change report

In terms of the Hungarian institutional framework, the most significant change occurred in the sector of higher education with the privatization of previously state-owned universities. The change was accompanied by a reconfiguration of the university's power balance and certain rights were shifted from the senate to the newly created board of trustees who are nominated by the government. According to Kováts and Rónay (Reference Kováts and Rónay2021: 23):

It is the board which can (and usually does) decide on the selection of the rector, the appointment of other senior university leaders (vice-rectors, chancellor, finance director), the budget, and the adoption of the university's organizational and operational rules (this includes the university's organizational structure but also the rules on employment of academics, and the selection and evaluation of students).

The first university to undergo the restructuration process was the Corvinus University of Budapest in 2019, when it was transformed from a state-financed institution to a private one financed by a designated non-profit foundation. In the later months, several other universities followed the privatization path, often not without conflict (for the case of the University of Theatre and Film Arts (SZFE), see Várnagy Reference Várnagy2021). In April 2021 a new type of institution, the ‘public trust funds performing a public function’, was created serving as a legal frame for the privatization process of the Hungarian higher education. Out of the 30 funds enlisted, 21 are in charge of universities, while others manage cultural institutions and similar establishments. Regarding the financing of the funds, the privatization process included a significant transfer of state-owned assets in the form of company shares, stocks and property assets. Most of these funds are managed by a board of trustees that are currently staffed by the government, and the funds’ directors can only be displaced by a two-thirds parliamentary majority, resulting in an indirect governmental oversight of these institutions. By the end of 2021, the majority of Hungarian universities are run by these funds, with only five universities remaining state-owned.

Issues in national politics

In the first half of 2021, the COVID-19 pandemic was deemed defeated due to an early and rather massive vaccination wave achieved through the approval of the Sputnik V (Russian) and Sinopharm (Chinese) vaccines. Later in the year, with the fourth wave of the pandemic hitting, the public discourse focused on the economic aspect of crisis management and allowed for an almost restriction-free everyday life. While vaccination rates plateaued, the availability of the vaccine (meaning that those who wish to do so can get vaccinated) overrode any other consideration.

In the beginning of 2021, the Hungarian public debate was rather focused on the conflict between the governing Fidesz and its European party family, the European People's Party (EPP). As the EPP grew more and more critical of Fidesz, mainly regarding of the rule of law in Hungary, the Hungarian governing party got increasingly vocal in its own criticism of the EPP. The final straw came in March when the EPP adopted a new rule allowing the party group the exclusion of members. Orbán was quick to react by asking all Fidesz MEPs to resign from EPP due to the hostile movement. Later in the year, Orbán continued his efforts to form an alternative alliance within the European Union, but only arrived to issue a declaration against the nationless construction of Europe signed in July by 16 European right-wing parties, among others the French National Rally, the Polish Law and Justice, and the Italy's League and Brothers of Italy.

Concerns about the quality of Hungarian democracy aggravated, as in July it was revealed that a military spyware, Pegasus, was used in many countries, including Hungary, to hack the smartphones of journalists, lawyers and activists. The presence of the spyware was confirmed on the smartphones of several journalists working for non-government-affiliated media outlets and, thus, the event was interpreted as another attack on media freedom in Hungary.

In the summer, controversial LGBTQ legislation further fuelled critics, as it banned access to pornographic materials for minors along with access to trans- and homosexuality-related content. The Act LXXIX of 2021 on ‘taking more severe action against paedophile offenders and amending certain Acts for the protection of children’ focuses on child sex abuse, and in fact increased sentences for paedophiles to protect children. However, the law also brought about restriction on portrayals of homosexuality and transgender people in a rather obscure way, without offering a definition of gay content or of ‘popularization’ as an activity, which suggests that the bill served as a tool for the government's anti-gay propaganda. Targeting the LGBTQ community continued throughout the year, as adoption by homosexual couples was made impossible and legal recognition of gender change became prohibited. The government seemed to build up the agenda for the upcoming 2022 elections when it promised to hold a referendum about the protection of children. Until then, Fidesz launched a new round of national consultations, a government-sponsored survey in which voters are invited to share their opinions by answering manipulated questions about the need to increase the minimum wage and about organizations financed by George Soros that promote sexual propaganda.

Despite the extensive efforts of the government to dominate the political and the public agenda, from September 2021 the opposition parties succeeded in capturing voters’ interest as they launched their first primaries (see Political party report). However, the inner conflicts of the opposition (Panyi et al, Reference Panyi, Pethő, Szabó, Matyasovszki and Szőke2022) and the prolonged negotiations resulted in the opposition losing its momentum and the success of primaries fading by the end of 2021.