Introduction

Since the Second World War, the liberal international economic order has depended on compensatory policies to mitigate the distributional effects of trade (Ruggie Reference Ruggie1982; Mansfield and Rudra Reference Mansfield and Rudra2021). In the United States, for example, Trade Adjustment Assistance supports workers who lose their jobs because of trade, while the European Globalisation Adjustment Fund serves a similar purpose in the EU. Other measures used to buy off the losers from globalization – and thereby avoid a backlash to globalization (Walter Reference Walter2021) – include generous unemployment benefits, subsidies, vocational training, and public investments to support struggling domestic industries. Governments may also impose temporary trade barriers to curb losses from imports. These compensatory policies serve as a tool to safeguard the liberal international order from popular discontent. However, this strategy may fail if the policies implemented by political elites do not align with the measures the public prefers.

In this study, we examine the attitudes of political elites and the public toward compensatory policies. The more similar the attitudes of the two groups toward different compensatory policies, the more likely it is that elites will implement policies that effectively mitigate a backlash against globalization. Conversely, a gap between elite and public preferences increases the risk that compensatory policies fail to achieve their intended purpose. Indeed, despite the widespread availability of such policies in many Western countries, we continue to observe a backlash against globalization (Walter Reference Walter2021) and subsequent structural economic change (Stutzmann Reference Stutzmann2025) and growing support for protectionist political parties (García-Viñuela, Motz, and Riera Reference García-Viñuela, Motz and Riera2024).

We anticipate an elite–public gap in preferences for compensatory policies for three key reasons. First, legislators are more directly exposed to lobbying. Second, they typically have greater access to information about policy consequences. Third, they are personally less affected by fluctuations in trade flows or the implementation of compensatory policies. As a result, we expect political elites, compared to the public, to show greater support for subsidies and infrastructure investments but less support for tax cuts. Additionally, we anticipate that, relative to the public, they will be less inclined to endorse trade barriers that restrict the trade flows that negatively affect certain segments of society. What is more, we expect political elites to exhibit stronger ideological differences in their attitudes toward compensatory policies than members of the public.

We test these expectations using original data from a survey of 625 legislators across various European countries and public opinion surveys in three European countries. Respondents were asked about their support for four compensatory policies: infrastructure projects, (wage) subsidies, tariffs, and tax cuts. While this is not a comprehensive list of compensatory policies, we chose these as they capture distinct logics of compensation: from avoiding the losses (tariffs), via direct (subsidies) and indirect (infrastructure projects) financial contributions, to a solution that reduces the role of the state (tax cuts). In terms of direct financial contributions, we opted for subsidies rather than unemployment benefits because doing so allowed us to distinguish between support directed at firms and support directed at workers (namely wage subsidies). We rely on hierarchical cumulative link models to investigate differences in support for each of these items by actor type (legislator or general public).

Our findings confirm an elite–public gap in compensation attitudes. Compared to legislators, the public is more supportive of tax cuts and tariffs but less supportive of infrastructure projects. We find no significant difference in support for subsidies. As expected, moreover, economic ideology is a stronger predictor of elite attitudes than public attitudes for three of the four policies analyzed. While our results indicate an elite–public gap, this divide is relatively small compared to the overall variation in support for different compensatory policies. Both elites and the public broadly favor infrastructure investments and tax cuts, while they hold mixed opinions on subsidies and tariffs.

Our research contributes to a substantial literature on compensatory policies. This research shows that globalization increases demand for compensation (Hays Reference Hays2009; Walter Reference Walter2010; Beesley Reference Beesley2020). On the supply side, US Trade Adjustment Assistance is responsive to trade shocks (Kim and Pelc Reference Kim and Pelc2021b), and legislators representing winners tend to support compensation (Rickard Reference Rickard2015), though who benefits also depends on geography and electoral institutions (Menendez Reference Menendez2016). When implemented, compensation shapes vote choice and political attitudes (Ehrlich and Hearn Reference Ehrlich and Hearn2014; Margalit Reference Margalit2011; Ritchie and You Reference Ritchie and You2021; Rickard Reference Rickard2023; Blanchard, Bown, and Chor Reference Blanchard, Bown and Chor2024), generally boosting support for incumbents and reducing opposition to globalization. Finally, work comparing different compensatory policies shows that compensation can take multiple forms (Spilker, Schaffer, and Bernauer Reference Spilker, Schaffer and Bernauer2012) and that compensatory and protectionist policies often act as substitutes (Kim and Pelc Reference Kim and Pelc2021a).

Our results go beyond this literature in several ways. We do not only show that different forms of compensation exist but also can rank different forms of compensation in terms of their acceptance by the public. What is more, our data allow us to show differences in similarities in compensation preferences between political elites and the public, something that has not yet been done. In so doing, while we do not share the present literature’s focus on the effectiveness of compensation, our study may help understand why, in the words of Rodrik (Reference Rodrik2024, i1077), ‘compensation never quite works in practice’ (see also the idea of ‘compensation failure’ in Frieden Reference Frieden, Catão and Obstfeld2019).

Relatedly, we contribute to the literature on the globalization backlash (Walter Reference Walter2021; Colantone, Ottaviano, and Stanig Reference Colantone, Ottaviano and Stanig2022). Compensatory policies are intended to mitigate opposition to globalization by offsetting or reducing the losses from trade. However, the growing support for political parties and candidates who reject the open trading system suggests that these policies do not fully achieve this goal. We explore one possible explanation: the divergence in attitudes toward compensatory policies between political elites and the public. Our findings indicate that, at the aggregate level, the elite–public gap is not large enough to fully account for the backlash. However, this aggregate perspective conceals an important nuance: legislators at both ends of the ideological spectrum hold positions that diverge significantly from the average policy preferences of the public. As a result, when right- or left-wing legislators implement policies aligned with their own views, a backlash is possible. Moreover, even if attitudes shape trade policy choices (Dür, Huber, and Stiller Reference Dür, Huber and Stiller2024b) and, in turn, the design of compensatory measures, real-world constraints may prevent legislators from enacting policies that align with both their own preferences and those of the public.

Finally, we add to recent research on differences and similarities in the political attitudes of elites and members of the public (Kertzer Reference Kertzer2022; Dellmuth, Scholte, Tallberg et al. Reference Dellmuth, Scholte, Tallberg and Verhaegen2022; Smetana and Onderco Reference Smetana and Onderco2022). These studies, just as our study, tend to find some differences between elites and the public in their political attitudes, although the particular composition of elites seems to explain at least part of these differences (Dellmuth, Scholte, Tallberg et al. Reference Dellmuth, Scholte, Tallberg and Verhaegen2022; Kertzer Reference Kertzer2022). We complement this research by focusing on trade policy and because of the large number of legislators it can draw on to gain a picture of the political attitudes of that specific type of elite. It also suggests that even when there are differences in attitudes between the elite and the public, the size of these differences can easily be exaggerated.

Argument

Trade generates net benefits for countries as a whole, but some groups within countries tend to lose – in the sense of experiencing economic harm resulting from adjustment costs – from an increase in imports (Alt, Frieden, Gilligan et al. Reference Alt, Frieden, Gilligan, Rodrik and Rogowski1996).Footnote 1 Among the losers from trade are businesses that face greater import competition and thus may go bankrupt or at least see a decline in profits. When capital invested in these businesses is not easily redeployable, this will cause losses for some capital owners. Moreover, greater imports may cause some workers to face lower demand for their specific skill set on the labor market (Autor, Dorn, and Hanson Reference Autor, Dorn and Hanson2016). This may lead to lower wages for them or even job losses. If the jobs are linked to people’s identities, the harm done may extend beyond financial loss.Footnote 2 According to Pierce and Schott (Reference Pierce and Schott2020), 47, the negative consequences of trade liberalization for individuals can be so severe that they lead to ‘deaths of despair’, namely a higher mortality due to drug overdoses.

The losers from trade may become politically active in opposition to the trade policy responsible for their losses. A key tenet of the international trading system after the Second World War has thus been that countries should compensate the losers from trade to maintain support for an open trading system. This approach has been called ‘embedded liberalism’ (Ruggie Reference Ruggie1982). Examples of such compensation measures for the losers of globalization are tax cuts, (wage) subsidies, public spending (eg on infrastructure) to increase domestic demand, unemployment benefits, and Trade Adjustment Assistance. Temporary trade restrictions to ease adjustment may also form part of the measures used to placate the losers from trade.

Some of these measures target the losers directly (eg subsidies or trade restrictions), whereas others may affect them only indirectly (eg tax cuts or infrastructure spending). When compensation is defined narrowly, trade restrictions are an alternative to compensation, as they reduce or eliminate the cause of the losses rather than reimburse the losers. From the perspective of the losers from trade, however, trade barriers are one possible response to their predicament, making trade compensation and trade protection substitutes (Kim and Pelc Reference Kim and Pelc2021a). We thus also subsume this policy option under the label compensation. In line with the embedded liberalism thesis, these compensation mechanisms can increase support for trade liberalization (Hays, Ehrlich, and Peinhardt Reference Hays, Ehrlich and Peinhardt2005; Ehrlich and Hearn Reference Ehrlich and Hearn2014), reduce calls for protection (Kim and Pelc Reference Kim and Pelc2021a), and make voters more likely to vote for the incumbent (Margalit Reference Margalit2011; Ritchie and You Reference Ritchie and You2021; Blanchard, Bown, and Chor Reference Blanchard, Bown and Chor2024).

Events such as Brexit and the two-time election of Donald Trump as US President, however, suggest that despite existing compensatory measures, many (Western) countries experience a backlash against globalization (Walter Reference Walter2021; Colantone, Ottaviano, and Stanig Reference Colantone, Ottaviano and Stanig2022). Moreover, import shocks have been associated with the rise of nationalist and radical right-wing parties in Europe (Colantone and Stanig Reference Colantone and Stanig2018) and worse electoral results for incumbents (Margalit Reference Margalit2011; Dür, Huber, and Stiller Reference Dür, Huber and Stiller2024a). These political effects of trade indicate that either the compensation offered does not fully offset the losses incurred or the compensatory policies offered by political elites are not the measures that members of the public would like to see implemented.

We thus ask how similar or different the attitudes of elites and the public are with respect to compensatory policies. The concrete political elites that we focus on are legislators who have a large influence over compensatory policies as they decide on the laws that underlie these policies.Footnote 3 Neither legislators nor the public are a homogeneous group in terms of policy preferences. What we compare across these two groups, then, are mean preferences. Below, we also consider differences within groups by analyzing the moderating role of economic ideology.

The assumption underlying the argument that we develop is that people (including both political elites and members of the public) are most concerned about how economic policies affect their personal income or wealth. That is, conditional on the information they have about the consequences of different policies, they exhibit greater support for policies that offer them larger economic gains than for policies that offer them lower economic gains. This is not to say that people do not also care about the benefits and losses of other people (or even non-material concerns such as identity). Rather, in assessing different options, we expect that people put a larger weight on their personal utility than on that of others. Policies that mostly promise to produce winners such as public spending on infrastructure thus should be supported by more people than policies that produce many losers (eg tariffs that can lead to higher prices). While this assumption makes it relatively easy to derive expectations about how people rank order different compensatory policies, we want to go a step further and explain how relative support for or opposition to policies may differ between legislators and the public.

Legislator and public preferences regarding compensatory policies might align for some reasons. In democracies, elected parliamentarians typically reflect voters’ preferences, as elections allow voters to choose representatives whose views are similar to their own. Additionally, concerns about re-election can prompt legislators to adjust their positions in response to shifts in public opinion (Soontjens and Sevenans Reference Soontjens and Sevenans2022; Meyerrose and Watson Reference Meyerrose and Watson2024). Consequently, democratic systems generally tend to exhibit high responsiveness between legislators and the public, at least when the public cares (Burstein Reference Burstein2014). Furthermore, political elites can influence public opinion (Soontjens and Sevenans Reference Soontjens and Sevenans2022; Meyerrose and Watson Reference Meyerrose and Watson2024), which may further strengthen the alignment between elite and public attitudes.

We still expect an elite–public gap with respect to attitudes toward compensatory policies for at least three reasons, namely lobbying, information, and affectedness. First, legislators are more directly exposed to lobbying by actors – especially firms and business associations – that anticipate concentrated costs or benefits from certain policies. While interest groups also engage in outside lobbying (aimed at the public) (Dür and Mateo Reference Dür and Mateo2016), inside lobbying (aimed at decision-makers) generally tends to dominate (eg De Bruycker and Beyers Reference De Bruycker and Beyers2019, 65). This may affect legislators’ views on compensation, with the direction of the influence depending on the balance of lobbying efforts from different actors (eg the relative strength of free trade and protectionist lobbying).

Second, legislators can be expected to have better information about the consequences of specific policy choices, particularly those with an international dimension.Footnote 4 For example, the possibility of foreign countries retaliating against protectionist policies may be less apparent to the general public than to legislators. The same applies to the link between free trade and lower consumer prices, which does not tend to feature prominently in media reports about trade (Guisinger Reference Guisinger2017, 47–48).

Third, the public is also more directly affected by the distributional effects of trade, as legislators’ jobs are not in direct competition with imports. By contrast, even in developed countries, a majority of workers are not highly skilled, meaning that they often fill jobs that are potentially threatened by imports (Bearce and Moya Reference Bearce and Moya2020, 380, FN3). In other words, compensatory measures matter relatively more for the income of the median member of the public.

How, then, should legislator and public attitudes toward compensatory policies differ? To start, we expect the public to be less supportive of big government than legislators in response to trade-related losses. This means that members of the public have a relatively lower preference for targeted spending policies (subsidies, infrastructure spending) and a relatively greater preference for tax cuts.Footnote 5 Each of the three reasons for an elite–public gap mentioned before plays a role in this.

First, targeted spending policies make it easier for legislators to secure a steady stream of resources from interest groups.Footnote 6 Indeed, for legislators, lobbying tends to entail a ‘legislative subsidy’ (for this term, see Hall and Deardorff Reference Hall and Deardorff2006). That is, when lobbying, interest groups exchange resources for access and influence, which benefits legislators. For legislators, for two reasons a large government is more likely to ensure a constant flow of legislative subsidies than tax cuts. For one, subsidies or infrastructure projects are easily designed to require repeated lobbying. By contrast, a tax cut is more likely a one-off policy. Moreover, since both subsidies and investments tend to be more tailored toward specific interest groups than tax cuts, collective action problems also are lower, and hence more lobbying should take place. Overall, therefore, legislators have an interest in offering a larger government to interest groups rather than tax cuts.

Second, information also matters. Legislators should be more aware of fiscal constraints. Although some public spending can be financed via debt, on average, elites likely know that tax cuts also mean less spending. Given that they benefit from the constant lobbying that targeted spending policies entail, this should make them relatively less supportive of tax cuts than members of the public.

Third, legislators and the public are also differently affected by large government. An increase in the size of government swells the importance of legislators’ role. By contrast, when given the choice, members of the public should prefer having higher net salaries or paying less to being taxed so that the government can spend the money. This should be so, not least because taxation produces considerable deadweight losses, with estimates for certain taxes going up to 63% (Tran and Wende Reference Tran and Wende2021). As calculated by Rodrik (Reference Rodrik2024), even with an excess burden of tax transfers of just 10%, this burden may offset any gains from trade liberalization. In support of this reasoning, public opinion data from 17 highly developed countries show that two-thirds of respondents would prefer lower taxes (Barnes Reference Barnes2015, 14). Moreover, Bremer and Bürgisser (Reference Bremer and Bürgisser2023) present evidence from experiments that shows that citizens generally prefer lower taxes, unless these taxes apply only to the better off.

Before formulating a hypothesis, we tackle two potential objections to our argument. The first is that redistributive policies actually enjoy substantial public support. Our response to this is that we do not argue that the public, on average, opposes subsidies or infrastructure projects. We just suggest that support for these policies is relatively lower among the public than among legislators. The second possible objection is that both voters (Barnes Reference Barnes2015) and legislators (Anderson, Butler, Harbridge-Yong et al. Reference Anderson, Butler, Harbridge-Yong and Agustin Markarian2023) disagree among themselves on the optimal level of spending and taxation (within and across countries). While we agree with this point, this does not invalidate our expectation, as our argument relates to the average preference about the size of government within both groups. We thus arrive at the following hypothesis:

H1: Members of the public prefer a smaller government, meaning less taxation and less targeted spending, than legislators.

We also expect the public to exhibit a greater preference for trade barriers to reduce the costs from imports than legislators. Of the three factors mentioned above as driving an elite–public gap, we expect especially information and affectedness to lead to different views on trade barriers.Footnote 7 Starting with information, legislators likely possess greater awareness of the negative consequences of protectionist policies, such as foreign retaliation or higher consumer prices. In terms of affectedness, as stated, members of the public are more directly affected by the negative consequences of a surge in imports, as their jobs may be at stake. Legislators’ jobs, by contrast, are not directly threatened by imports – only indirectly, if voters hold them accountable for the trade policies they support.Footnote 8 This greater affectedness of the public to the distributional effects of trade should make them relatively more supportive of tariffs because keeping one’s current job is likely preferable to relying on unemployment benefits or retraining for a new position. Moreover, greater direct affectedness also should make people prefer to address the root causes of economic losses directly, as they are skeptical of compensation promises. Indeed, Bisbee, Mosley, Pepinsky et al. (Reference Bisbee, Mosley, Pepinsky and Peter Rosendorff2020) argue that insufficient compensation in the past has disillusioned trade’s losers, leading them to oppose economic openness. Based on this reasoning, our second hypothesis is as follows:

H2: Members of the public exhibit greater support for trade barriers than legislators.

So far, we have treated the public and legislators as homogeneous blocs. Within both groups, however, individuals vary significantly in terms of their preferences over compensatory policies. Political ideology is a core factor that can lead to such differences. Generally, economically left-leaning persons (both among the public and legislators) should be more supportive of big government and less concerned about upholding free trade. Support for large government implies that a left-wing ideology should be negatively associated with support for tax cuts and positively associated with support for higher spending on subsidies or infrastructure.Footnote 9

Legislators, however, are more ideologically consistent than the public. Already in 1964, Converse (Reference Converse2006, 47) described voters as ‘innocent of “ideology”’ and only classified 3.5% of voters as ‘ideologues’ (p. 17). Converse’s conclusion has not gone unchallenged (for a review, see Clawson and Oxley Reference Clawson and Oxley2020), but also more recent research has found that only a minority of voters can be considered ideologically consistent (13%, according to Lewis-Beck, Norpoth, Jacoby et al. Reference Lewis-Beck, Norpoth, Jacoby and Weisberg2009, 279). In any case, our argument is only relative: that elites have more consistent ideological positions than the public, not that the public is not ideologically consistent at all. This relative assessment is supported by research that found legislators to have very stable ideological positions (Poole and Rosenthal Reference Poole and Rosenthal2007). Moreover, a few studies have tried to assess this difference directly, supporting the point of an elite–public difference in terms of ideological consistency (Jennings Reference Jennings1992; Kinder and Kalmoe Reference Kinder and Kalmoe2017).

We expect these arguments to travel beyond the context of the United States, in which this debate has generally played out. An elite–public divide hence should also exist in terms of ideological consistency in other countries. Applied to our question, this means that legislators’ attitudes toward compensatory policies should be more reflective of their ideology than the attitudes of members of the public. This does not mean that the promise of office may not entice legislators to compromise on their ideology, just that their attitudes toward compensatory policies are more ideologically consistent (for a discussion, see eg Strom and Müller Reference Strom, Müller, Müller and Strom1999). We hence expect:

H3: The influence of ideological differences on support for or opposition to specific compensatory policies is greater among legislators than among members of the public.

Beyond the reasons mentioned so far for an elite–public gap with respect to compensation measures, compositional differences may also lead to divergent preferences between political elites and the public. Political elites tend to be older, wealthier, more highly educated, and more male than the public (Kertzer Reference Kertzer2022). Elites and the public also differ in terms of their psychological traits (Hafner-Burton, Leveck, Victor et al. Reference Hafner-Burton, Leveck, Victor and Fowler2014). To isolate the effects of the lobbying, information, and affectedness channels we outlined above, we control for important demographical characteristics of our respondents in the empirical analysis. Nevertheless, we also show that our results are substantially the same in the absence of these controls.

Research design

Samples

Our empirical approach is based on original data from public opinion surveys and a survey of legislators. The public opinion surveys were fielded by Bilendi in Poland and Spain in 2022 and in the United Kingdom in 2023. From Poland and Spain, we have 3000 respondents each and from the United Kingdom, 2128. The surveys were designed to be representative of adult citizens of these countries with respect to age, gender, and region (and in Poland and Spain, also with respect to income).

The legislator survey was fielded between April 2021 and March 2022. For practical reasons, we were unable to field the legislator survey and the public opinion surveys exactly at the same time, but the time lag is small. We included legislators from 47 democracies across the globe in this survey. From these countries, we contacted all legislators from the parliamentary chambers for which official email addresses were publicly available. In this study, we only use the data from European countries. We do so to keep the samples of legislators and the public similar. This leaves us with responses from 625 legislators from 19 countries, including 86 legislators from Spain and the United Kingdom, whereas our sample does not include any Polish legislators.Footnote 10

The countries included in our sample vary in terms of electoral (majoritarian versus proportional) and welfare state systems (liberal, Southern and hybrid). In principle, therefore, our results should be generalizable to a broad set of countries. At the same time, all of them are relatively highly developed democracies in Europe. We thus expect our results to hold for all democracies in Europe.

We contacted the legislators via email and sent reminders after about one month. The questionnaire was available in eight languages so that most legislators in our sample could respond in the official language of their country.Footnote 11 The number of responses that we got varies considerably across countries. Figure 1 shows that the largest numbers are from Italy, Switzerland, and Spain, whereas the numbers are small for the Nordic countries. By contrast, for other respondent characteristics, the response rates were similar (see online Supplementary Materials section A).

Figure 1. Number of legislators by country.

Experimental and survey design

Moving on to the survey design, the public opinion and the legislator surveys contained the same question that we use to assess our hypotheses. Concretely, this question read:

Trade agreements often lead to losses for [businesses]/[workers] via increased international competition. To help these [businesses]/[workers], please tell us how much you would support or oppose the following measures:

-

(a) Direct []/[wage] subsidies

-

(b) Higher tariffs on imports

-

(c) Tax cuts

-

(d) Infrastructure projects

For each of the four measures, respondents could choose their answer on a five-point scale from ‘Would completely oppose’ (recoded to 0) to ‘Would completely support’ (recoded to 4). The question randomly varied whether businesses or workers bear the losses from trade agreements (and would be helped by government action). While we do not theorize this variation, it serves to ensure that the results are not influenced by different connotations associated with the potential beneficiaries of compensation. In the robustness checks, we analyze the direct and moderating impact of the two different wordings and find only small differences (see section G in the Supplementary Materials).

We selected these measures because they reflect different logics of compensation. Tariffs eliminate the imports that generate economic losses, whereas the other measures preserve trade openness while seeking to mitigate its effects. Subsidies and tariffs can be relatively easily targeted at those directly harmed by trade, while tax cuts and infrastructure projects are more diffuse in their impact and harder to target precisely. The measures also differ in the role they assign to the state: while subsidies, infrastructure investment, and tariffs expand the state’s involvement in the economy, tax cuts reduce it. Finally, the policies vary in type: subsidies, infrastructure projects, and tax cuts are distributive, whereas tariffs constitute a regulatory intervention. These dimensions of variation are central to our argument.

To test Hypothesis 3, we need a measure of respondents’ political ideology. In the public opinion surveys, we asked respondents the following question to gauge their ideology:

In politics people often talk of ‘left’ and ‘right’. Individuals who place themselves toward the left in economic terms want the government to play a large role in the economy. They desire higher taxes, more regulation, and public spending as well as an extension of the welfare state. Individuals who place themselves toward the right in economic terms want the government to play a small role in the economy. They desire lower taxes, less regulation, and public spending as well as a smaller welfare state. Where would you place yourself on this scale?Footnote 12

Respondents could indicate their position on a scale from 0 (left) to 10 (right). We simplified this to a five-point scale (where 0–1 was coded 1, 2–3 as 2, 4–6 as 3, and so on) to match the data for the legislators. As could be expected, most respondents locate themselves toward the middle of the scale, but (in the simplified version) 11% indicated that they are far-left and 7% that they are far-right.

For legislators, we relied on the economic left-right position of their political party. Concretely, we took the economic left-right variable (the value for the last election before our survey) from the V-Party dataset (Lindberg et al. Reference Lindberg, Düpont, Higashijima, Kavasoglu, Marquardt, Bernhard, Döring, Hicken, Laebens and Medzihorsky2022). This variable defines economically left parties as ones that ‘want government to play an active role in the economy. This includes higher taxes, more regulation and government spending and a more generous welfare state’. By contrast, economically right parties are characterized as wanting ‘a reduced economic role for government: privatization, lower taxes, less regulation, less government spending, and a leaner welfare state’. The wording of the question that we asked in the public opinion survey, hence, is very similar to the wording used to code parties in the V-Party dataset. We recoded this variable from the original seven-point scale to a five-point scale by combining the two lowest values (0 and 1) and the two highest values (5 and 6). We then filled some missing values using variable V4 from the Global Party Survey (Norris Reference Norris2020), which classifies the current stance of a party on economic issues such as privatization, taxes, regulation, government spending, and the welfare state. Among legislators, 18% were classified as far-left and 13% as far-right.

Ideally, we would have ideology data for the individual legislator. For four reasons, however, this was not possible. First, the survey needed to be short, to maximize the number of responses we get. Second, in such a short survey, there was a considerable danger of a question on ideology influencing the answers to the substantive questions (if we ask about ideology at the beginning) or the substantive questions influencing the answer to the question on ideology (if we ask about ideology at the end). Third, legislators (more so than members of the public) may answer a question on ideology strategically, for example, by avoiding extreme values. Finally, across countries, legislators’ conceptions of what it means to be ‘left’ or ‘right’ can differ (Laver Reference Laver2014). As a result, comparing legislators’ self-assessments across countries may be more problematic than relying on expert coding following strict criteria. In any case, the fact that we use party ideology as a proxy should make it more difficult for us to find support for H3 and the results conservative.

Estimation strategy

For the analysis, we pool the data for the public and for legislators. We estimate cumulative link models to account for the fact that the dependent variable is ordinal. In tests of Hypotheses 1 and 2, we regress the four measures included in our question on the actor type (public or legislator) and the control variables. For the test of Hypothesis 3, we interact the actor type and the ideology variable.

As we want to disentangle our argument about the elite–public gap from compositional differences, next to ideology, in all models we control for gender and education (university degree or not).Footnote 13 Indeed, we have a far greater share of men among the legislators than among the respondents in the public opinion surveys (64% as compared to 49%; see Table A1 of the Supplementary Materials). The same applies to education levels (76% of legislators have a university degree, as compared to 44% of the public). Moreover, although the assignment of respondents to the text with workers or business losing was random, we also control for the treatment. In fact, because we randomized the treatment across countries and drop the non-European respondents for this study, our sample includes a slightly larger share of legislators that received the business treatment. Finally, in all models, we add random effects at the country level to account for the fact that both legislators and the public are nested in countries. In robustness checks, we also run the models with respondents only from Spain and the United Kingdom and a jackknife test, without this changing the substantive results. Table A1 in the Supplementary Materials offers summary statistics for all variables used in the analysis, separately by actor type.

Results

Descriptive evidence

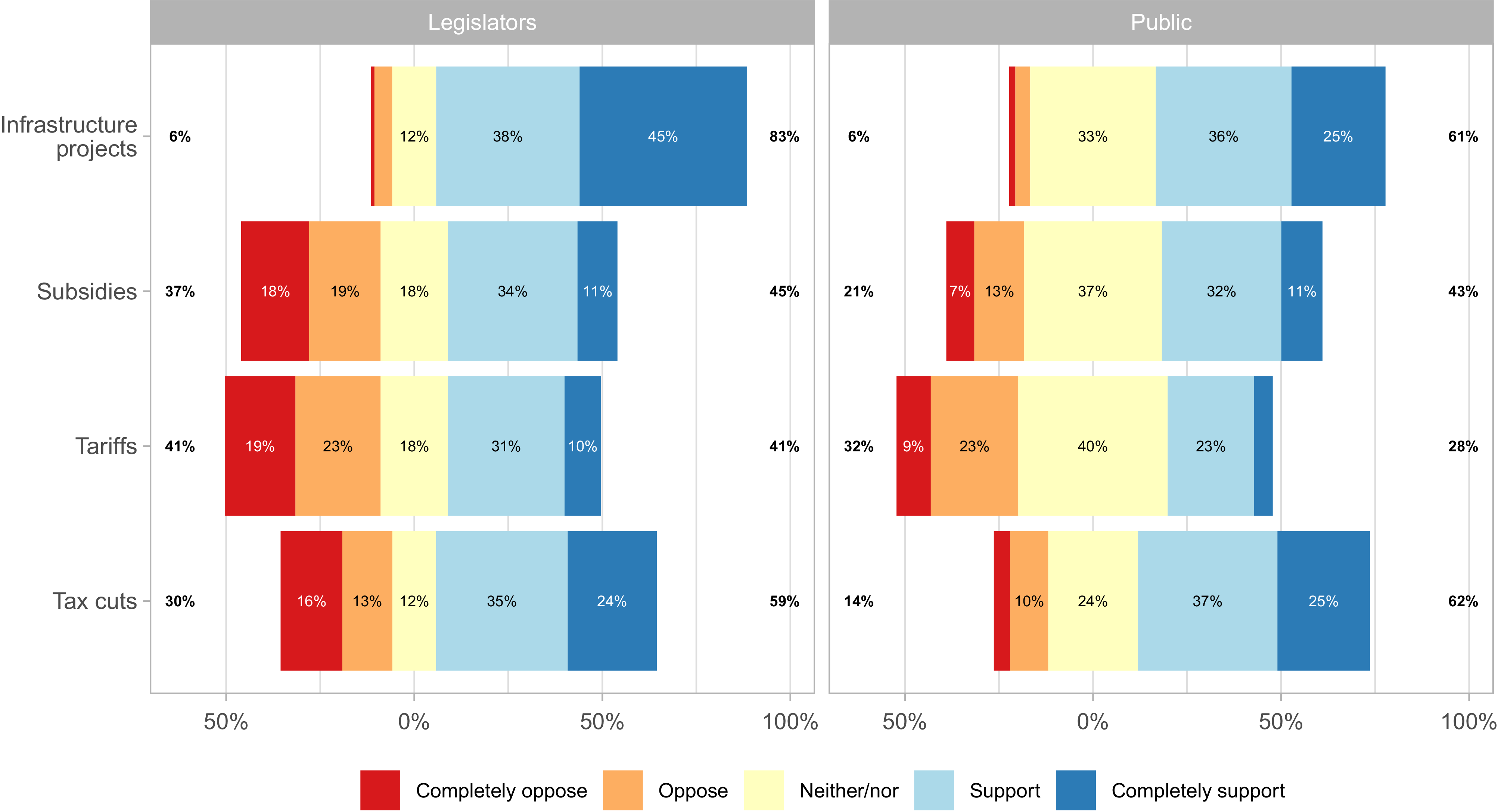

Figure 2 shows the distribution of responses to the survey question, separately for legislators and the public. As can be seen, infrastructure projects receive most net support (ie support minus opposition) from both types of actors, whereas higher tariffs on imports receive least net support. Only two of the measures, infrastructure projects and tax cuts, are supported by a majority of both legislators and the public. Of importance for an assessment of our hypotheses, the figure also shows some differences between legislators and the public in the evaluation of these measures. Infrastructure projects clearly are seen more positively by legislators than by the public, whereas for subsidies, tariffs and tax cuts legislators exhibit more opposition. In the absence of controls, this evidence offers only limited support for Hypotheses 1 and 2. The indifference shown by a significant number of respondents from the public leaves open the possibility that, as expected in H3, ideology plays a larger role for legislators. The key take-away from this first look at the data, however, is that the differences between the attitudes of legislators and the public with respect to compensatory policies are minor relative to the differences in support for different measures by both types of actors.

Figure 2. Support for compensatory measures by actor type.

Note: The total percentages shown in the margins omit the middle category.

Figure 3 further disaggregates the evidence shown in Figure 2 by ideology. For this, we consider respondents left-wing if they score below 3 on the scale that ranges from 1 to 5 and right-wing if they score above 3. The remaining observations are coded as center.Footnote 14 The figure shows that (a) support for different measures varies strongly by ideology and (b) this variation by ideology looks differently for legislators than the public. The exception to this are infrastructure projects (first row), which are strongly supported by legislators and citizens independent of their ideological leaning. No combination of type (legislator or public) and ideology sees lower support than 57%.Footnote 15

Figure 3. Support for compensatory measures by actor type and ideology.

Note: The total percentages shown in the margins omit the middle category.

For the other three measures, we find support for the expectation set out in Hypothesis 3. For each of them, we do not only see variation in support by ideology, but also that this variation is stronger for legislators than for members of the public. Left-wing legislators support both subsidies and tariffs, but this support turns into majority opposition for right-wing legislators. Members of the public also see a shift in the same direction, but far less pronounced. As a result, purely descriptively, for these two measures right-wing voters are not well represented by right-wing legislators. For tax cuts, we observe strong opposition among left-wing legislators turning into strong support among right-wing legislators. By contrast, members of the public across the full ideological spectrum overwhelmingly support tax cuts. While we also see a correlation between ideology and the attitudes of members of the public with respect to tax cuts, it is far less pronounced than for legislators. For three of the four compensatory policies, therefore, this descriptive evidence supports Hypothesis 3.

Main models

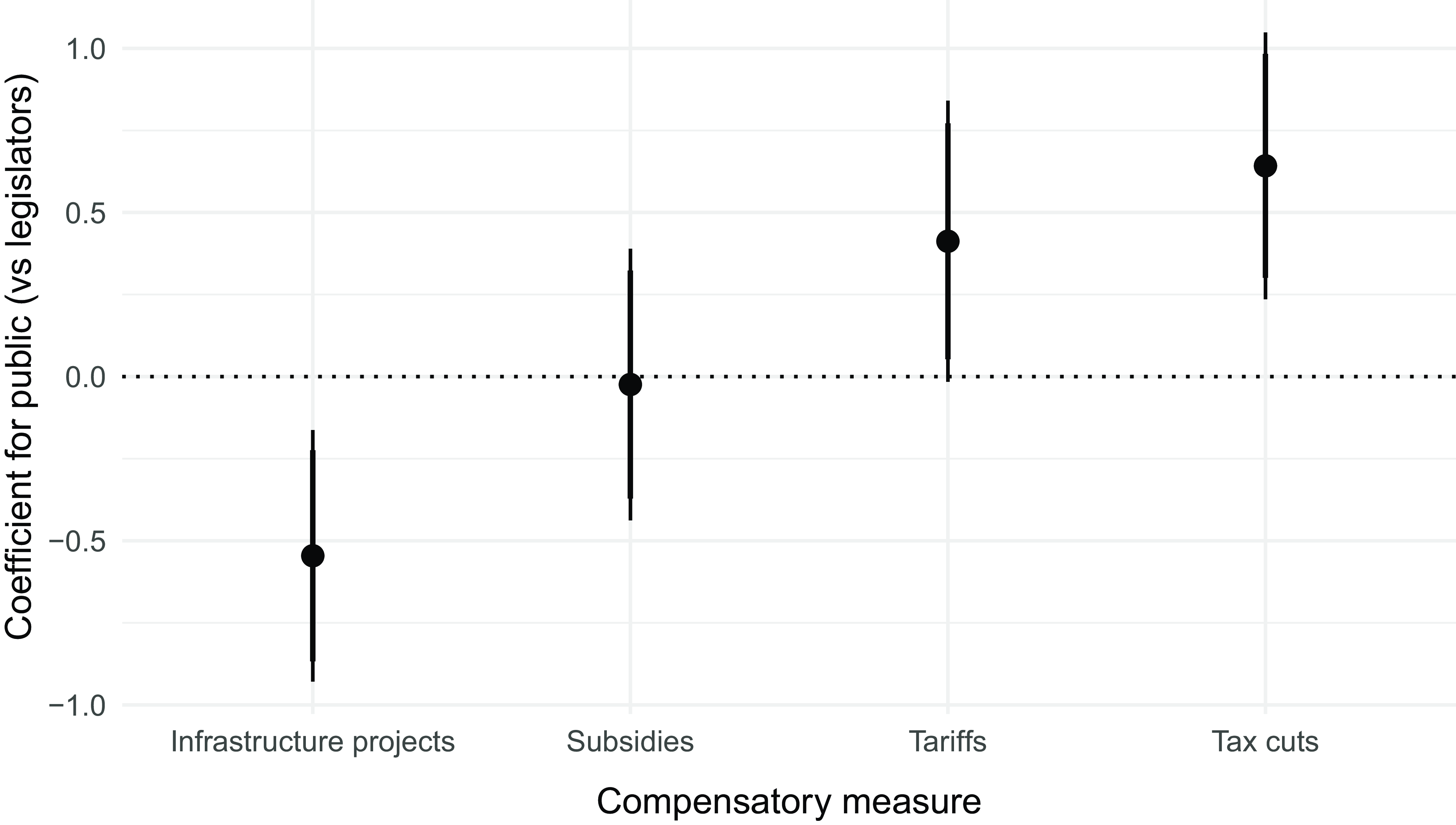

Going beyond this descriptive evidence, we move on to test the relationship between actor type, ideology, and support for compensatory measures more systematically.Footnote 16 Hypotheses 1 and 2 expect that legislators and members of the public differ in their preferences over compensatory policies. Specifically, we anticipate that the public is less supportive of large government (subsidies and infrastructure projects together with taxes) and more supportive of tariffs. To test this, Figure 4 shows the regression coefficients and standard errors for a dummy that captures whether an observation is from a member of the public or a legislator (reference category). As expected in Hypothesis 1, members of the public exhibit greater support for tax cuts and less support for infrastructure investments. However, we do not find a substantive difference in legislators’ and the public’s views on subsidies.

Figure 4. The elite–public gap with respect to compensatory policies.

Note: Ranges show 90% and 95% confidence intervals. The models are estimated with random effects at the level of countries to account for unobserved heterogeneity across countries. Full results are shown in Table C2 in the Supplementary Materials.

In line with Hypothesis 2, moreover, members of the public are more supportive of the introduction of new tariffs to compensate losers of trade. For the three measures where we find differences between legislators and the public, the size of these differences is relevant. In concrete numbers, for tax cuts the public have an 11.7% higher probability of picking the category indicating complete support (and 14.8% for support and completely support) according to this model. For tariffs, citizens have an 8.7% higher probability to pick a supporting category. Finally, concerning infrastructure projects, we observe the (expected) opposite picture. The probability to pick the highest category is 12.4% higher for legislators than for members of the public. These effects are not small, but still smaller than the differences across policy measures found in Figure 2. Overall, these findings largely back Hypothesis 1 and fully support Hypothesis 2.

Moving on to Hypothesis 3, we rely on predictions from a model interacting actor type and ideology to demonstrate differences between legislators and the public.Footnote 17 In Figure 5, the horizontal facets represent the response category for each policy item, which ranges from ‘completely oppose’ to ‘completely support’. The vertical facets show the different compensation policy options. The x-axis shows the different levels of ideology (from 1, very left, to 5, very right). On the y-axis, we show the predicted probability of selecting a specific response for each combination of policy item, support level, ideology, and actor type. The different actors are indicated by colors of the ribbons. The estimates are bootstrapped from 1000 redrawn samples to obtain a measure of uncertainty. In the Supplementary Materials, we also show the marginal effects by actor type as an alternative illustration of these effects (see Figure C1).

Figure 5. Predicted choices by the public and legislators by ideology.

Note: The ribbons indicate 95% confidence intervals. The models are estimated with random effects at the level of countries to account for unobserved heterogeneity across countries. Full results are shown in Table C2 in the Supplementary Materials.

Starting with the first row (infrastructure), we observe that both legislators and the public are generally supportive of infrastructure projects to compensate the losers from trade agreements. Legislators are even a bit more enthusiastic about this policy tool but, contrary to our expectation in Hypothesis 3, ideology does not moderate this relationship. The elite–public gap occurs across the underlying left-right placement of legislators and members of the public. Additionally, ideology does not seem to have a direct effect, since all lines in Figure 5 are basically flat. Left- and right-wing actors do not differ in their levels of support for infrastructure spending.

Moving on to subsidies (second row of Figure 5), the model suggests that both legislators and the public are most likely to select the middle category. We also see that ideology has a direct effect on support for subsidies, since right-wing respondents are more likely to oppose subsidies and less likely to support them. Importantly for our assessment of Hypothesis 3, the coefficient for the interaction in Table C2 is positive and statistically significant. This indicates that, as expected, members of the public and legislators follow different trajectories. Nevertheless, as shown in the figure, the differences are not very large.

We do find strong support for Hypothesis 3 with respect to tariffs and tax cuts in Figure 5. Starting with tariffs, members of the public are generally – and throughout their left-right placement – unlikely to oppose tariffs. Legislators, in contrast, share similar views with the public when they are left-wing, but right-wing legislators are substantially more likely to oppose this measure, accounting for roughly 60% of their responses. Hence, on tariffs legislators are clearly more driven by their ideological leaning than the public. Figure C1 in the Supplementary Materials drives home this point by demonstrating that center to right-wing legislators systematically and significantly differ from the public. The right-hand side of Figure 5 (ie the ‘support’ and ‘completely support’ response options) mirrors this pattern. Hence, support for tariffs as a compensatory measure is clearly a combination of actor type and ideology, lending support to Hypothesis 3.

Finally, we also observe a significant moderation concerning support for tax cuts (last row in Figure 5). Left-wing legislators strongly oppose tax cuts, whereas left-wing members of the public express less opposition. Concerning support for tax cuts, the direct effect of ideology dominates. That is, both right-wing members of the public and legislators are substantially more willing to support tax cuts, in contrast to their left-wing counterparts. Figure C1 confirms this relationship and demonstrates that the difference between the public and legislators occurs on the left-wing of the ideological distribution.

Overall, these findings offer mixed support for Hypothesis 3. For tariffs and tax cuts, fully in line with our expectation, ideology plays a considerably larger moderating role for legislators than for members of the public. The effect is in the direction expected and statistically significant for subsidies, but in terms of effect size rather small. Contrary to our expectation, however, ideology has the same (zero) effect on legislators and members of the public for infrastructure spending.

Robustness checks

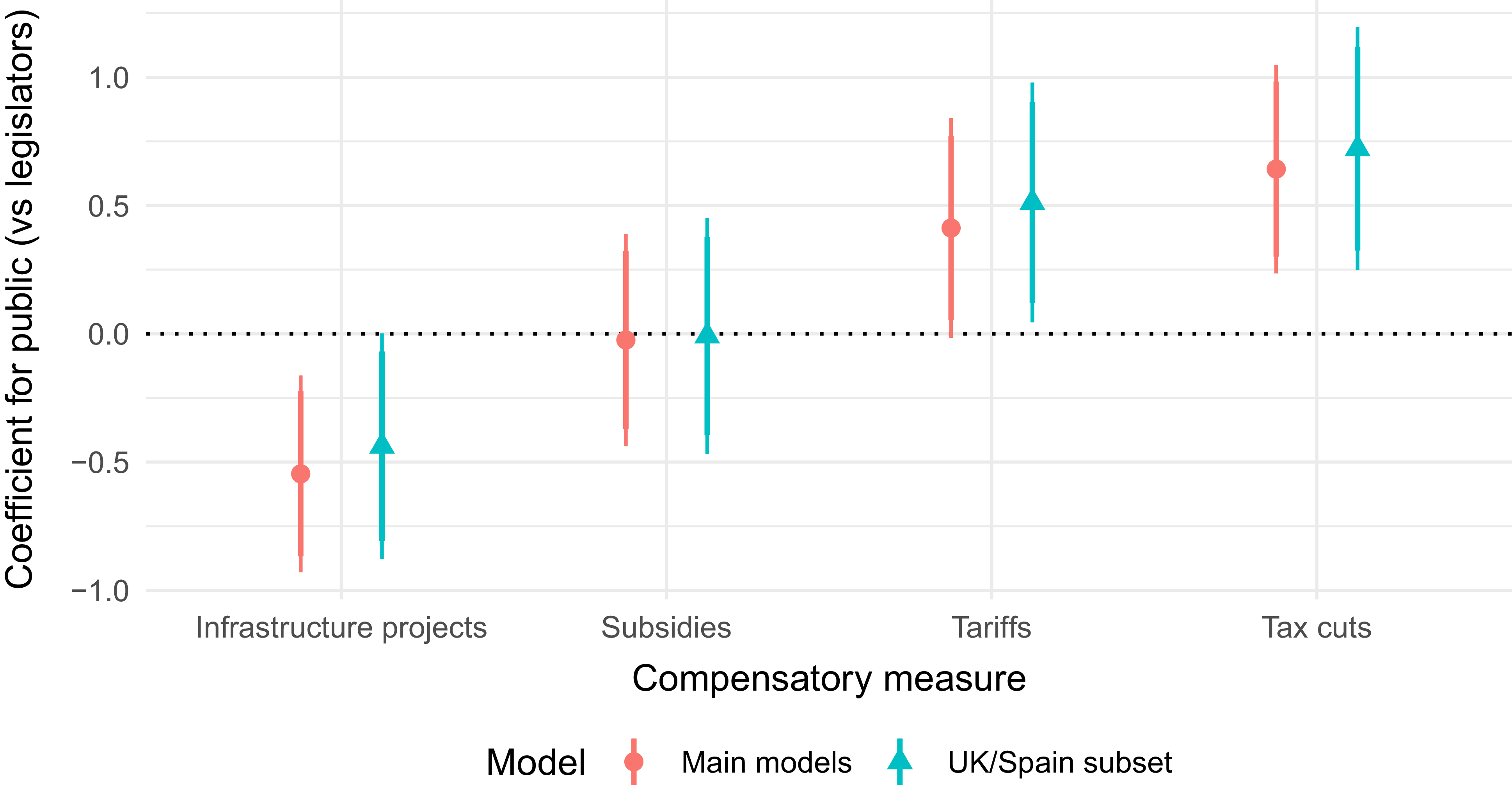

We conduct a series of checks to probe the robustness of our findings. First, our elites data is substantially more heterogeneous in terms of countries covered than our public opinion data. While we restrict our legislator sample to European countries, this may nonetheless bias our results. Hence, in Figure 6, we show the key coefficients from models in which we restricted our sample to the United Kingdom and Spain (Table E1 in section E of the Supplementary Materials shows the full results). The red ranges show the results from the main models discussed above, whereas the turquoise ranges show the estimates from the subset of British and Spanish respondents. We do not observe sizeable differences in the substantive results. As before, we see a negative coefficient for the public for infrastructure spending and positive coefficients for tariffs and tax cuts (whereas the coefficient for subsidies is not statistically significant). Moreover, as before, the interaction for public and ideology is statistically significant and positive for subsidies and tariffs, and statistically significant and negative for tax cuts (see Table E2).

Figure 6. The elite–public gap with respect to compensatory policies (British and Spanish respondents).

Note: Ranges show 90% and 95% confidence intervals. The models are estimated with random effects at the level of countries to account for unobserved heterogeneity across countries. Full results are shown in Table E1 in the Supplementary Materials.

Second, we discussed variation in elites’ response rates across countries in our research design. As a result, it could be that individual countries strongly drive our results. To scrutinize this, we jackknifed the analyses and dropped one country per iteration. Figure F1 in section F in the Supplementary Materials suggests that the results are not driven by individual countries. Third, we ran the main models without control variables to check whether the elite–public differences we observe only emerge once controlling for compositional differences. The results, however, are very similar to those we reported before (see section D in the Supplementary Materials).

Finally, the question wording we used varied whether businesses or workers lose from international competition and hence could benefit from the measures taken by government. While the randomization of this element of the question wording should eliminate systematic differences across legislators and the public, in this robustness check we have a closer look at whether this wording matters for our results. Figures G1 and G2 in section G of the Supplementary Materials suggests that – as expected – the framing of beneficiaries has limited effects on the differences between the public and legislators. While there are mild differences, such as for subsidies, where the public is more supportive of subsidies for workers and legislators are more supportive of subsidies for firms, they fail to reach statistical significance. Figure G2 additionally shows that the overall pattern of support does not vary by the treatment condition. Figures G4 and G5 also outline the limited effect of ideology as a moderating factor. By and large, the effects of actor type are constant throughout the treatment conditions. Some mild differences appear, particularly when it comes to subsidies, where right-wing members of the public are substantially more supportive of the worker condition, but we observe no difference between legislators and the public in the firm condition. Overall, these findings suggest that the results presented are robust and not driven by the treatment condition.

Conclusion

Do political elites and the public share the same preferences for compensating the losers of international trade? Drawing on novel data on the compensation preferences of legislators and the public, we have found evidence of an elite–public gap concerning attitudes toward compensatory policies. Specifically, legislators are more supportive of infrastructure projects and less supportive of tariffs and tax cuts than the general public. Moreover, legislators’ attitudes toward tax cuts, tariffs, and (to a lesser extent) subsidies are shaped more strongly by their ideological leanings than those of the public. While these findings are indicative of an elite–public gap, we also found that in terms of size, this gap is considerably smaller than variation in support across different compensatory policies, with infrastructure spending receiving much more backing from both legislators and the public than tariffs.

Our findings carry several important implications. First, they might help understand why compensation has not been able to avoid a backlash to globalization in many countries. Several studies indicate that compensation does not work well in practice (Rodrik Reference Rodrik2024; Bisbee, Mosley, Pepinsky et al. Reference Bisbee, Mosley, Pepinsky and Peter Rosendorff2020; Davidson, Matusz, and Nelson Reference Davidson, Matusz and Nelson2007; Frieden Reference Frieden, Catão and Obstfeld2019) and may be conditional on citizens’ perceptions of the government (Garritzmann, Neimanns, and Busemeyer Reference Garritzmann, Neimanns and Busemeyer2023). Different preferences over which policies to rely on in the face of trade-induced losses provide one possible explanation for this observation. We find systematic differences between legislators and the public for most compensatory policies. Nevertheless, we are skeptical that the aggregate differences we find are large enough to have much of a real-world impact. Following our data, legislators would want to spend on infrastructure to boost the economy in response to an import shock and the public would welcome this policy choice. However, once considering the ideological leaning of legislators, a larger elite–public gap emerges that might contribute to the backlash to globalization.

Second, while some earlier research suggests that elite opinions often align with public opinion (Kertzer Reference Kertzer2022), few systematic studies have examined the extent of this elite–public congruence or divide. Our study contributes to a growing body of research addressing this gap (Kertzer Reference Kertzer2022; Dellmuth, Scholte, Tallberg et al. Reference Dellmuth, Scholte, Tallberg and Verhaegen2022; Smetana and Onderco Reference Smetana and Onderco2022). To our knowledge, it is the first to do so in the context of attitudes toward compensatory policies for trade-related losses. Our findings reveal only moderate differences between elites and the public, positioning them between claims of close alignment (Kertzer Reference Kertzer2022) and those of a substantial gap (Smetana and Onderco Reference Smetana and Onderco2022). Moreover, the size of this gap varies across policies and ideological groups. This suggests that the globalization backlash may, in part, stem from a mismatch between the policy preferences of certain elites and those of the public they represent.

Third, and relatedly, our findings suggest a shared preference by both legislators and the public for compensation over protectionism. This is an encouraging sign for the liberal international order, which faces increasing challenges globally (Lake, Martin, and Risse Reference Lake, Martin and Risse2021). The policy consensus around compensatory measures may serve as a stabilizing force in the face of growing skepticism toward globalization and international institutions.

Our findings open up several avenues for further inquiry. One promising direction is to explore cross-country differences in the elite–public divide. It remains unclear whether the patterns observed here are generalizable to non-Western contexts or whether cultural, institutional, or economic differences shape the preferences of elites and the public in distinct ways. Moreover, it would be interesting to delve deeper into how people weigh the trade-off between compensation and protection. While we find that generally both elites and the public prefer compensation to protection, this preference may depend on whether individuals expect to personally win or lose from trade. Finally, it would be interesting to analyze whether our findings travel to compensation preferences related to other policies that also produce losers (eg decarbonization policies, see Gaikwad, Genovese, and Tingley Reference Gaikwad, Genovese and Tingley2022) or technological change (Busemeyer and Tober Reference Busemeyer and Tober2023).

In short, our study sheds light on the determinants of elite and public preferences regarding compensatory policies. The recent politicization of trade and the backlash against economic openness in many countries highlight the importance of addressing this question. Better understanding elite and public attitudes toward compensatory policies may help policymakers respond to the challenges to the liberal international order.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1475676526100796

Data availability statement

A full replication package can be downloaded from the Open Science Foundation at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/VACXOD.

Acknowledgements

This research has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the EU’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program (grant agreement No 724107). We are grateful for helpful comments from Cal Le Gall, the EJPR’s editorial team, and three anonymous reviewers on earlier versions of this paper.

Competing interests

This article was co-authored by a member of the EJPR editorial team prior to their appointment. The editorial process adhered to the journal’s standard independent peer review procedures to ensure fairness and transparency.