Introduction

The European elections of 2024 were frequently portrayed as a contest between pro‐EU (European Union) mainstream parties and their anti‐EU challengers (Camut, Reference Camut2023; Jones, Reference Jones2023). The preceding European elections had already been framed similarly (Hernández & Kriesi, Reference Hernández and Kriesi2016; Hobolt & De Vries, Reference Hobolt and De Vries2016; Treib, Reference Treib2021). On the one hand, this stark juxtaposition of pro‐ and anti‐EU positions may raise the stakes in these second‐order elections and mobilize voters, as shown by the increased turnout in 2019 and 2024. On the other hand, it risks overlooking the increasingly differentiated positions among generally pro‐EU mainstream parties, that is, the parties that routinely alternate between government and opposition (De Vries & Hobolt, Reference Vries and Hobolt2012, Reference Vries and Hobolt2020).

A growing literature has shown that mainstream parties have embedded their stances on European integration into their general ideological positioning (Prosser, Reference Prosser2016; Schäfer et al., Reference Schäfer, Popa, Braun and Schmitt2021; Whitefield & Rohrschneider, Reference Whitefield and Rohrschneider2019). They also emphasize specific policies more than their Eurosceptic challengers who focus primarily on constitutive polity issues (Braun et al., Reference Braun, Hutter and Kerscher2016). Less is known, however, about the logic behind this embedding of EU integration issues into mainstream parties’ general positioning. In this paper, we seek to tease out the differences between mainstream parties and the factors that shape their competition over EU issues.

The ‘polycrisis’, that is, the ‘confluence of multiple, mutually reinforcing challenges facing the EU’ (Zeitlin et al., Reference Zeitlin, Nicoli and Laffan2019, p. 973) in the 15 years since the global financial crisis, has highlighted mainstream parties’ disagreements over Europe and propelled matters of redistribution into the limelight. The creation of Eurobonds, the relocation of refugees and conflicts at the EU's borders – these issues not only moved the hearts and minds of citizens but also led to shifts and adaptations in parties’ assessments of and positionings on the integration process. In the crisis, we claim, two fundamental understandings of European integration have come to structure the public discourse and political competition over the future of the EU. On the one hand, the supporters of ‘European solidarity’ (Katsanidou et al., Reference Katsanidou, Reinl and Eder2022; Waas & Rittberger, Reference Waas and Rittberger2023; Wallaschek, Reference Wallaschek2020) promote a Union that supports member states in need by creating novel forms of redistribution such as the Corona recovery fund ‘NextGenEU’, the short‐term unemployment benefit scheme ‘SURE’ or a relocation scheme for asylum seekers. On the other hand, the proponents of ‘national self‐reliance’ support a form of European integration that strengthens the resilience of member states by setting and enforcing common standards but avoids redistribution due to its encouragement of ‘moral hazard’. We conceptualize this dynamic as a competition between the two pro‐European but otherwise distinct polity ideas of a ‘redistributive polity’ and a ‘regulatory polity’ (Freudlsperger & Weinrich, Reference Freudlsperger and Weinrich2024; Genschel & Jachtenfuchs, Reference Genschel and Jachtenfuchs2018). The result of this competition is the emergence of different varieties of pro‐Europeanism among mainstream parties. What determines mainstream party support, we therefore ask, for either of these two polity ideas?

Our paper makes a twofold theoretical contribution to analyse the emerging varieties of pro‐Europeanism among mainstream parties. First, it combines a conceptualization of two ideal‐typical polity ideas with a discussion of their requirements for transnational solidarity. Second, it theorizes the determinants of mainstream party support for policies in line with either of these polity ideas. In general, due to their domestic preference for communal burden‐sharing and attachment to universalistic values, economically left and culturally progressive parties should be more inclined to promote transnational solidarity than economically right and culturally conservative parties. However, we expect notable differences in the dynamics of mainstream party competition over European redistribution across domestic contexts and different policy domains. Mainstream parties, we suggest, now disagree visibly over issues of transnational redistribution, but their competition varies with their ideological commitments, domestic context and the policy domain in question.

We test our expectations on data provided by the ‘EUandI’ voting advice application (Cicchi et al., forthcoming; Reiljan et al., Reference Reiljan, daSilva, Cicchi, Garzia and Trechsel2020), which contains party positions on core EU policies for all member states for the four European Parliament (EP) elections in 2009, 2014, 2019 and 2024. Our analysis focuses on ‘core state power’ (Genschel & Jachtenfuchs, Reference Genschel and Jachtenfuchs2014) integration, namely fiscal, taxation, migration and security policy. Core state domains were most affected by the polycrisis, forcing a choice between national self‐reliance and transnational solidarity. Various model specifications support our general expectation that progressive and left parties are more likely to support redistribution than conservative and right parties. This support, however, interacts with domestic considerations and varies strikingly across policy domains. On the one hand, the domestic salience of a policy accentuates parties’ positioning. The more salient a policy, the higher the likelihood that left and progressive parties come out in support of redistribution. At the same time, this general dynamic is conditioned by a country's net‐payer status. Left mainstream parties from net‐paying member states, in particular, are less likely to support solidarity than left mainstream parties from net‐receiving member states, given the potential fiscal and electoral costs of transnational solidarity (Beramendi, Reference Beramendi2012). Across policy domains, we notably find that mainstream party competition over redistribution in migration policy is driven by the cultural dimension alone and that, in matters of security and defence, economically right parties support European solidarity more than their left competitors.

Our findings advance the literature on the party politics of European integration as they show that mainstream parties largely continue to support integration but differ markedly in their substantive understandings of the EU. The crisis‐induced debates about European solidarity and redistribution have led to a discernible differentiation of integration positions between mainstream parties across ideological fault lines. The polycrisis, our paper demonstrates, has revealed different varieties of pro‐Europeanism among mainstream parties: Even though support for redistribution varies across policy domains and is conditioned by domestic factors, progressive and left parties broadly support transnational solidarity while conservative and right parties support an EU that strengthens national self‐reliance. These findings are crucial as they demonstrate that voters have a meaningful choice beyond just voting for pro‐ or anti‐European forces and that EU elections can be understood as a contest between distinct understandings of Europe beyond the binary distinction between integration and disintegration.

Mainstream party ideologies and different substantive notions of Europe

The central role of mainstream parties in EU‐level and domestic policymaking calls for thorough scrutiny of their evolving positions on European integration. The polycrisis pushed mainstream parties towards developing clearer and more distinct positionings on European integration (Carrieri, Reference Carrieri2024; Dolezal & Hellström, Reference Dolezal, Hellström, Hutter, Grande and Kriesi2016; Hellström & Blomgren, Reference Hellström and Blomgren2016). As the parties that regularly hold governmental duties, they had long shied away from publicly and prominently emphasizing their general support for the EU (Aspinwall, Reference Aspinwall2002; Hellström, Reference Hellström2008; Hooghe et al., Reference Hooghe, Marks and Wilson2002), instead seeking to downplay and depoliticize the issue (Braun & Grande, Reference Braun and Grande2021). This tendency towards ‘benign neglect’ was due to European integration's status as a wedge issue, which enables Eurosceptic challengers to sow division among mainstream parties’ membership and electorate (De Vries & Hobolt, Reference Vries and Hobolt2020; Hobolt & de Vries, Reference Hobolt and Vries2015; Hooghe & Marks, Reference Hooghe and Marks2018; van de Wardt et al., Reference Wardt, De Vries and Hobolt2014). This provided mainstream parties with strategic disincentives to emphasize their EU positions (Green‐Pedersen, Reference Green‐Pedersen2012). As a result, beyond offering vague support for integration, which kind of Europe mainstream parties preferred long remained a more or less open question.

This dynamic changed with the public salience of the polycrisis and the concomitant rise of Eurosceptic parties, which compelled mainstream parties to take a clearer stance (Maier et al., Reference Maier, Jalali, Maier, Nai and Stier2021). Issues of solidarity and redistribution, which were at the core of the heated public debates during the Euro area or the migration crisis, have galvanized mainstream party competition over Europe. In the crisis context, it became more difficult for mainstream parties to refrain from developing a distinct understanding of European integration. Where an issue is highly salient among the electorate, mainstream parties ignore it at their own electoral cost (Schmitt & Thomassen, Reference Schmitt and Thomassen2000). Late‐night summits, high‐stakes decisions and public protests all pushed mainstream parties towards taking sides and presenting voters with clearer choices (Braun & Grande, Reference Braun and Grande2021, p. 1137). As mimicking Eurosceptic parties’ positions contains significant electoral risks (Meijers & Williams, Reference Meijers and Williams2020; Williams & Hunger, Reference Williams and Hunger2022) and exit visions lost attractiveness in the wake of the Brexit referendum (Malet & Walter, Reference Malet and Walter2024; Martini & Walter, Reference Martini and Walter2024), mainstream parties were under pressure to spell out crisis‐proof ideas for integration within the existing institutional framework of the EU.

A growing literature has shown that mainstream parties have embedded their stances on the EU into their general ideological positioning (Prosser, Reference Prosser2016; Whitefield & Rohrschneider, Reference Whitefield and Rohrschneider2019). When it comes to the fundamentals of parties’ ideological commitments, contemporary theories of party competition usually assume a two‐dimensional space (Hooghe et al., Reference Hooghe, Marks and Wilson2002; Kriesi et al., Reference Kriesi, Grande, Dolezal, Helbling, Höglinger, Hutter and Wüest2012). Parties’ views on material and economic issues place them on the economic left‐right dimension, while value‐based cultural and social issues locate them on the cultural dimension ranging from progressive to conservative. In the post‐Maastricht period, the cultural dimension has become increasingly central for parties’ positioning on matters of EU integration, with progressive parties adopting increasingly pro‐European stances and conservative parties becoming gradually less integrationist (Schäfer et al., Reference Schäfer, Popa, Braun and Schmitt2021). Pro‐EU mainstream parties furthermore place more emphasis than their Eurosceptic challengers on specific policies than on constitutive polity issues (Braun et al., Reference Braun, Hutter and Kerscher2016). How this incorporation of EU policy issues into their general ideological positioning varies across generally pro‐European mainstream parties, however, has been of lesser concern to the extant literature.

The substantive nature of mainstream parties’ understandings of the future of the EU, that is, which kind of Europe they support, remains insufficiently understood. Large‐N studies of the link between mainstream parties’ integration stances and their ideological positionings (Prosser, Reference Prosser2016; Whitefield & Rohrschneider, Reference Whitefield and Rohrschneider2019) are usually not concerned with the substantive type of integration but operationalize their dependent variable as some variant of the pro‐ to anti‐integration continuum. In our view, this specification of the outcome variable overlooks a good part of the variance in mainstream parties’ substantive positions on European integration beyond their general support for the EU. To give but one example, while the German liberal party FDP and their Green party counterpart have consistently held similar pro‐integration scores in the Chapel Hill Expert Survey (CHES; Jolly et al., Reference Jolly, Bakker, Hooghe, Marks, Polk, Rovny, Steenbergen and Vachudova2022), their outlook on the future of the EU and their emphasis on the value of transnational solidarity differs drastically (Freudlsperger & Weinrich, Reference Freudlsperger and Weinrich2024). By systematically investigating the factors and conditions underpinning mainstream parties’ endorsement of different substantive ‘polity ideas’ (Hooghe & Marks, Reference Hooghe, Marks, Kitschelt, Lange, Marks and Stephens1999; Jachtenfuchs, Reference Jachtenfuchs2002; Parsons, Reference Parsons2003), we thus fill a gap in the existing literature on the party politics of European integration.

Polity ideas on European integration

The contemporary emergence of distinct substantive notions of the future of the EU, we argue, is intrinsically linked to the post‐Maastricht integration of ‘core state powers’ (Bremer et al., Reference Bremer, Genschel and Jachtenfuchs2020; Genschel & Jachtenfuchs, Reference Genschel and Jachtenfuchs2014; Kuhn & Nicoli, Reference Kuhn and Nicoli2020), that is domains close to the core of national sovereignty. Different ideas about the finalité of European integration have long existed (Hooghe & Marks, Reference Hooghe, Marks, Kitschelt, Lange, Marks and Stephens1999; Parsons, Reference Parsons2003), but the integration of core state powers altered the dynamics of European integration. While the European Communities of the 1980s and early 1990s were primarily occupied with the technical regulation of the internal market (Dyson, Reference Dyson2021; Jabko, Reference Jabko2006), the post‐Maastricht EU entered into domains that had previously been conceived as the hallmarks of the modern territorial state: internal security and defence, border and migration policy and monetary and fiscal affairs. This propelled the EU from a market‐based international organization on par with other organizations in the European political space (Patel, Reference Patel2020) to an encompassing supranational polity matching the substantive scope of the territorial nation‐state (Leuffen et al., Reference Leuffen, Rittberger and Schimmelfennig2022).

As the European integration of core state powers is prone to politicized crisis, it has required mainstream political actors to take a stance. First, foreign and defence, monetary and taxation or border and migration policies are more hotly debated among citizens than product safety regulations, intellectual property rights or liberalized telecommunications markets. Consequently, the EU and its impact on member states have become much more visible than in the ‘old days’ of market integration. The transition from the tacit acceptance of integration among indifferent European electorates to the politicization of recent years (de Wilde, Reference Wilde2011; de Wilde et al., Reference Wilde, Leupold and Schmidtke2016; Kriesi, Reference Kriesi2016) was thus driven by the EU's push beyond the market. Second, due to their distinct logic of integration, core state domains have been riddled with crisis. Rather than creating state‐like fiscal, administrative and coercive capacities (Freudlsperger & Jachtenfuchs, Reference Freudlsperger and Jachtenfuchs2021; Genschel & Jachtenfuchs, Reference Genschel and Jachtenfuchs2014, Reference Genschel and Jachtenfuchs2016), the EU held on to its tried and tested regulatory template even beyond market integration. It created a common currency but refrained from forging a common fiscal policy. It abolished internal borders but shied away from establishing a common control of its external borders. The crises of the past 15 years exposed the instability of this institutional fair‐weather constellation.

The highly salient and polarized debates during the polycrisis brought to the fore a dualism between two competing notions of the EU, one based on the core value of ‘European solidarity’ (Katsanidou et al., Reference Katsanidou, Reinl and Eder2022; Oana & Truchlewski, Reference Oana and Truchlewski2023; Sangiovanni, Reference Sangiovanni2013; Stjernø, Reference Stjernø2009; Waas & Rittberger, Reference Waas and Rittberger2023; Wallaschek, Reference Wallaschek2020) and the other embracing national self‐reliance. A variety of contributions have framed this development as a competition between the notions of a solidarity‐based ‘redistributive polity’ (Citi & Justesen, Reference Citi and Justesen2021; Freudlsperger & Weinrich, Reference Freudlsperger and Weinrich2024; Genschel & Jachtenfuchs, Reference Genschel and Jachtenfuchs2018; Nicoli, Reference Nicoli2017) and a ‘regulatory polity’ (Majone, Reference Majone1996) centred on self‐reliance. The distinction builds on the longstanding market‐centred dualism between a ‘neoliberal European project’ and a European ‘project of regulated capitalism’ (Hooghe & Marks, Reference Hooghe, Marks, Kitschelt, Lange, Marks and Stephens1999; cf. Jabko, Reference Jabko2006). While neoliberal Europe relied on minimal regulation, the latter understanding focused on market correction. The distinction between a ‘regulatory’ and a ‘redistributive’ polity translates and extends these notions to the era of core state power integration.

Both these notions are integrationist, that is, proponents of both the regulatory and redistributive polity support continued European integration. Neither supports a roll‐back or even dismantling of the status quo of EU authority. In terms of their normative fundament and their practical policy implications, however, these two understandings of Europe are clearly distinct. Moreover, as regulation has to date been the dominant and default mode of core state power integration (Genschel & Jachtenfuchs, Reference Genschel and Jachtenfuchs2014, Reference Genschel and Jachtenfuchs2018), redistributive capacities are usually created in addition to regulatory measures and the EU arguably requires elements of both to overcome the challenges it faces in core state power integration. In this paper, we thus put a particular emphasis on the extent to which mainstream parties move beyond mere support for regulation and endorse redistributive policies.

In analysing the varieties of mainstream parties’ pro‐EU positions, we build upon Freudlsperger and Weinrich's (Reference Freudlsperger and Jachtenfuchs2021, Reference Freudlsperger and Weinrich2024) ideal‐typical distinction between a regulatory and a redistributive polity ideal type (cf. Table 1). The assumption is that generally pro‐European mainstream parties position themselves somewhere between these two ideal types by means of the EU‐level policies they support. Proponents of the redistributive polity support European solidarity through burden‐sharing among member states. They regard the EU as a transnational political community that produces and provides scarce collective goods to states and citizens. Supporters of the classic notion of the regulatory polity, on the other hand, see the EU as a market‐centred organization to manage externalities between states. EU institutions, in this view, are important to monitor and enforce EU rules, but the member states are solely responsible for adapting to common European standards and mobilizing the necessary resources to enhance the welfare of their citizens. To provide a specific example of the pro‐European nature of these otherwise distinct polity ideas: while proponents of the redistributive polity regarded the creation of Eurobonds or of a European Deposit Insurance Scheme as a necessary ingredient of a solidary solution to the Euro crisis, supporters of a regulatory idea of Europe proposed giving EU institutions far‐reaching monitoring and oversight powers, for example, through a ‘Super‐Commissioner’ to veto national budgets (Schoeller, Reference Schoeller2017).

Table 1. Main features of a ‘regulatory’ and a ‘redistributive’ polity, building on Freudlsperger and Weinrich (Reference Freudlsperger and Weinrich2024)

Freudlsperger and Weinrich (Reference Freudlsperger and Weinrich2021, Reference Freudlsperger and Weinrich2024) analyse the emergence of these varieties of pro‐Europeanism solely for the case of Germany and refrain from theorizing their occurrence beyond parties’ general ideological positioning. We add to the existing literature by analysing mainstream party competition over European redistribution across all EU member states. This allows us to gauge whether the distinction between a regulatory and a redistributive polity has come to drive the polycrisis‐era politics of EU integration beyond the single case of Germany. Furthermore, it allows us to theorize and investigate how the ideological underpinnings of mainstream party support for either of the two ideas interact with strategic considerations and how it plays out across different policy domains. Our approach thus enables a better understanding of the conditions under which mainstream parties across the EU and across various policy domains endorse a normative understanding of European integration centred on the fundamental value of either transnational solidarity or national self‐reliance.

Theorizing the varieties of pro‐Europeanism among mainstream parties

To theorize the varieties of pro‐Europeanism among mainstream parties, we combine this conceptual distinction between two fundamental polity ideas with the literature on the party politics of European integration. The latter has highlighted the role of both ideological and strategic factors in the formation of mainstream party positions on European integration (Prosser, Reference Prosser2016). In this perspective, mainstream parties might oppose transnational solidarity either for ideological reasons, for example, because a proposed EU‐level burden‐sharing policy conflicts with their domestic ideological stance, or for strategic reasons, for example, because they deem EU‐level burden‐sharing to run counter to the ‘national interest’ or because they expect backlash from challenger parties. While our primary emphasis here lies on mainstream parties’ ideological commitments and how they translate into different normative understandings of European integration, ideology does not occur in a vacuum and parties always weigh their ideological convictions against their strategic interests. In line with the extant literature, we assume that ideological and strategic perspectives are complementary (Prosser, Reference Prosser2016). To arrive at a better understanding of mainstream parties’ substantive conception of the EU polity, our paper thus analyses the effect of their ideology and the ways in which it interacts with their strategic considerations, that is, the salience of a policy issue and the practical implications of solidarity.

Our analysis proceeds in three steps. We formulate two general expectations on mainstream party competition over European redistribution (Hypotheses 1 and 2) before theorizing the impact of strategic domestic considerations (Hypotheses 3 and 4) and the effect of specific policy domains (Hypothesis 5). We turn to our general expectations first. Parties, the literature has shown, embed their positions on European integration into their domestic positioning. That is, they regard EU policies through the prism of their worldview (Hooghe et al., Reference Hooghe, Marks and Wilson2002; Hooghe & Marks, Reference Hooghe and Marks2018). Our hypotheses on the effects of ideology on parties’ adherence to a specific EU polity idea build on the general assumption of a two‐dimensional political space in which mainstream parties hold distinguishable positions on economic and cultural issues (Hooghe et al., Reference Hooghe, Marks and Wilson2002; Kriesi et al., Reference Kriesi, Grande, Dolezal, Helbling, Höglinger, Hutter and Wüest2012).

In the domestic realm, economically left mainstream parties are ideologically closer to a position of solidarity and communal or societal burden sharing. With respect to the European integration of core state powers, we thus expect left parties to translate this domestic position into a preference for transnational solidarity and to adhere more closely to the idea of a redistributive polity. Parties of the mainstream right, on the other hand, have traditionally placed more emphasis in their domestic discourse on individual autonomy and the welfare‐enhancing effects of competition. They should also apply this domestic conviction to the transnational politics of core state power integration and align more closely with the value of national self‐reliance and thus the idea of a European regulatory polity. From this perspective, we expect parties of the mainstream left to exhibit a stronger tendency to support the creation of a redistributive polity, while parties of the mainstream right should support the strengthening and expansion of the regulatory polity.

Hypothesis 1: Mainstream parties of the economic left are more likely to support a solidarity‐based redistributive polity than mainstream parties of the economic right.

We now turn towards the impact of the cultural dimension of party competition on parties’ integration stances (Hooghe et al., Reference Hooghe, Marks and Wilson2002; Hooghe & Marks, Reference Hooghe and Marks2018; Prosser, Reference Prosser2016; Schäfer et al., Reference Schäfer, Popa, Braun and Schmitt2021). In general, culturally progressive parties have been shown to be more integrationist than culturally conservative ones (Prosser, Reference Prosser2016). In this vein, Hooghe and Marks (Reference Hooghe and Marks2018, p. 123) see a new transnational cleavage at work, which was reinforced by the recent crises of European integration and pits ‘libertarian, universalistic values against the defence of nationalism and particularism’. We thus expect a cultural logic to equally underpin mainstream parties’ support for the two polity ideas. Whereas progressive parties tend to define their political community in universal, cosmopolitan terms, conservative parties regard the national community as the vantage point of democratic politics (Beramendi et al., Reference Beramendi, Häusermann, Kitschelt and Kriesi2015). Consequently, in core state power domains, progressive parties that take universalistic and cosmopolitan positions on domestic cultural issues should translate them into a preference for transnational community and solidarity and a support for the build‐up of a redistributive polity on the EU level. Culturally conservative parties whose domestic platforms are more particularistic and centred on the national community, in turn, should translate them into an opposition to transnational solidarity and a preference for the European regulatory polity.

Hypothesis 2: Culturally progressive mainstream parties are more likely to support a solidarity‐based redistributive polity than culturally conservative parties.

We now look beyond these general patterns and delve deeper into their interaction with strategic considerations. One expectation is that mainstream parties only show their true colours proactively when they feel compelled to. We thus expect salience to affect mainstream parties’ propensity to support European solidarity. EU politics tends to be a ‘wedge issue’ that threatens mainstream parties with severe intra‐party conflict and a divided electorate and therefore provides challenger parties with a promising entry point into domestic party competition (de Vries & Hobolt, Reference Vries and Hobolt2020; Hobolt & de Vries, Reference Hobolt and Vries2015; van de Wardt et al., Reference Wardt, De Vries and Hobolt2014). Mainstream parties thus usually shy away from specifying their positions on EU integration beyond vague support to avoid alienating voters or restricting their leeway in EU‐level negotiations (de Vries, Reference Vries2007; Green‐Pedersen, Reference Green‐Pedersen2012). By default, their interest is to depoliticize the issue. Mainstream parties, we hold, only face a strong incentive to carve out distinct substantive positions for themselves when and where voters begin to base their domestic electoral choices on EU issues. In other words, they respond to the public salience of European integration (Beyers et al., Reference Beyers, Dür and Wonka2018; de Wilde et al., Reference Wilde, Leupold and Schmidtke2016; Rauh & de Wilde, Reference Rauh and Wilde2018). As a crucial factor underpinning mainstream parties’ strategy on European issues, salience interacts with their ideological positioning. More concretely, we expect that increases in salience further enhance the support for transnational solidarity among economically left and culturally progressive parties while exacerbating the opposition of economically right and culturally conservative parties.

Hypothesis 3: An increased salience of a given EU policy domain in the national public strengthens left and progressive mainstream parties' support for a solidarity‐based redistributive polity and weakens support among right and conservative mainstream parties.

In accordance with the idea of a redistributive polity, capacity creation in core state domains tends to produce visible material costs and comes with redistributive consequences (Genschel & Jachtenfuchs, Reference Genschel and Jachtenfuchs2018). While some countries stand to profit from European solidarity, others, at least in the short term, contribute more than they receive. Supporting redistribution can thus also be electorally costly if it is widely perceived as not in the ‘national interest’ since a given country stands to lose rather than gain from European solidarity. We therefore expect mainstream parties’ positioning on the future of Europe to interact with their country's position as either a net contributor or net recipient of European solidarity. An often‐used heuristic to estimate a country's redistributive position, especially in the public debate, consists of a country's net payer status in the EU multiannual budget (Beramendi et al., Reference Beramendi, Häusermann, Kitschelt and Kriesi2015; Rodden, Reference Rodden2005; Schelkle, Reference Schelkle2017), which is calculated based on member states’ economic output. In net‐contributing member states, the public debate often revolves around a perceived role as the ‘paymaster’ of Europe, rendering it more difficult for mainstream parties to endorse measures of transnational redistribution. This equally applies to left and progressive parties in net‐contributing member states, which should thus prefer ‘interpersonal’ or domestic over ‘interregional’ or European forms of redistribution (Beramendi, Reference Beramendi2012). In countries that are usually net recipients of European money flows, mainstream parties are likely to be less reticent with respect to transnational redistribution and the institutionalization of European solidarity. We contend that a country's net‐contributor position is also a reliable heuristic for the costs of solidarity beyond fiscal and taxation matters. In security policy, the assumption that wealthy and thus more capable member states contribute more to a common European defence is plausible. The pooling and sharing of military capacities is a form of solidarity between differently capable states. Even in migration policy, the various solidarity mechanisms adopted or proposed between 2015 and 2024 relied primarily on the size of individual member states’ economy and their population.Footnote 1

Hypothesis 4: Mainstream parties from net‐contributing member states are less likely to support a solidarity‐based redistributive polity than mainstream parties from net‐receiving member states.

Finally, the economic and the cultural dimension vary not only in their focus on economic and material aspects but also in social and value questions, respectively. They are furthermore linked to specific areas of political action (Hooghe et al., Reference Hooghe, Marks and Wilson2002; Kriesi, Reference Kriesi1998). While it is generally possible to politicize any policy issue from a material or a value perspective, existing analyses have linked the former dimension to, for example, party positions on taxation and the welfare state and the latter to, for instance, personal freedoms and societal stability (Bakker & Hobolt, Reference Bakker, Hobolt, Evans and de Graaf2013; Jolly et al., Reference Jolly, Bakker, Hooghe, Marks, Polk, Rovny, Steenbergen and Vachudova2022). In other words, some policy areas are systematically related to the economic dimension and others to the cultural dimension. We expect that these linkages also apply to core state power integration. Hence, mainstream party positions on the integration of taxation and fiscal policies should be driven more by their economic than their cultural stance. This, we expect, is because, in both policy areas, the material consequences of policies are directly visible. In turn, a mainstream party's position on the cultural dimension should have a stronger effect on its support for redistribution in the areas of migration (Carvalho & Ruedin, Reference Carvalho and Ruedin2020) and security policy (Cicchi et al., Reference Cicchi, Genschel, Hemerijck and Nasr2020) as both policy fields are closely tied to identity‐ and value‐based considerations. European solidarity in the field of migration is driven by humanitarian convictions and universalistic considerations of fundamental and human rights, that is, values oftentimes associated with culturally progressive parties. Solidarity in the area of defence, on the other hand, is directed at protecting the community of Europeans from outside threats, that is, potentially using national defence resources to defend other member states in the community. While European solidarity in defence could also be affected by longstanding pacifist leanings among economic left mainstream parties, we expect it to chime in well with the universalistic and cosmopolitan convictions of progressive mainstream parties.

Hypothesis 5: While mainstream party competition on taxation and fiscal issues is predominantly driven by the economic dimension, the cultural dimension predominantly drives their competition on migration and external security issues.

Data and method

To construct our dependent variable, that is, a party's position on EU redistribution, we use the Reiljan et al. (Reference Reiljan, daSilva, Cicchi, Garzia and Trechsel2020) longitudinal dataset on party positioning in the EU. The data stems from party positions in voting advice applications for the European Parliament elections in 2009 (‘EU Profiler’), 2014, 2019, and 2024 (‘EUandI’) in all member states (Cicchi et al., forthcoming).Footnote 2 Party positions were collected from parties and coded by country experts at the European University Institute for all member states of the EU. Based on data derived from the latest version of the ‘Political Parties, Presidents, Elections, and Governments’ (Krause et al., Reference Krause, Stelzle and Berlin2024) database, we excluded all non‐mainstream parties that had never been in government at the time of a given EP election (De Vries & Hobolt, Reference Vries and Hobolt2012).Footnote 3 For the 2024 election, we manually checked whether parties had entered government for the first time since the latest Political Parties, Presidents, Elections and Governments data from Summer 2023. All in all, our data contains 2570 positions of mainstream parties in support of either a position of European redistribution and solidarity or national self‐reliance. The individual statements are situated on a policy level. We claim that, in an era of European integration driven by revisions of secondary rather than primary law, political actors primarily disclose their polity ideas by supporting or opposing specific EU policies. These statements thus lend themselves neatly to an analysis of the varieties of pro‐Europeanism among mainstream parties.

For our study, we use items from Reiljan et al. (Reference Reiljan, daSilva, Cicchi, Garzia and Trechsel2020) that touch upon the four core state domains borders and migration, external security, fiscal and monetary policy and taxationFootnote 4 and hold clear redistributive consequences. We identified two questions in 2009, six in 2014, five in 2019 and eight in 2024 with redistributive consequences.Footnote 5 The dataset indicates whether a party fully disagrees, tends to disagree, is neutral, tends to agree or fully agrees with a statement. As we are interested in whether a party explicitly supports a redistributive approach to core state power integration, for our logistic regression models, we transformed these positions into binary values, coding all positions in agreement or in full agreement as support for the redistributive polity and all other positions as a lack of support. Our dependent variable for redistributive positioning (red) thus indicates whether a party supports a redistributive statement (tends to agree, fully agrees) or does not express explicit support (neutral, tends to disagree, fully disagrees).Footnote 6 As a robustness check, we also compute ordinal logistic regression and ordinary least square (OLS) regression models that utilize all five levels of the dependent variable and provide the results in the online Appendix (cf. Tables A4 and A5). We further compute models that exclude individual policies and mainstream parties widely considered as Eurosceptic (cf. Tables A6 and A7 in the online Appendix).Footnote 7

To operationalize our independent variables on party ideology for Hypotheses 1 and 2, we use data from the CHES to measure a party's position on the economic (lrecon) and cultural dimension (galt) (Jolly et al., Reference Jolly, Bakker, Hooghe, Marks, Polk, Rovny, Steenbergen and Vachudova2022). The CHES codebook defines the lrecon measure as the ‘position of the party in [a given year] in terms of its ideological stance on economic issues’ and the galt measure as the ‘position of the party in [a given year] in terms of their views on social and cultural values’. Both variables range from 0 (extreme left; progressive) to 10 (extreme right; conservative). We use the 2010 wave for the 2009 election and the 2014 and 2019 waves for the respective elections in these years. For 2024, we use the latest data from the 2023 speed CHES on Ukraine. At 0.28, the correlation between our two main independent variables, that is, a given mainstream party's economic and cultural positioning is modest (cf. Figure A1 in the online Appendix) and hence we should not encounter serious issues with the stability or interpretation of our models.

To examine Hypothesis 3, we employ Eurobarometer data to measure the public salience of a core state power domain (iss_sal). We use the share of respondents within a member state that perceive a policy area as the most important political issue facing their own country. We use the Eurobarometer wave in the quarter before each EP election. The value of this variable can range from 0 to 100.Footnote 8 For Hypothesis 4, we include a dummy variable indicating whether a country is a net contributor to the EU budget (net_payer) at the time of an EP election.Footnote 9 We derive member states’ net‐contributor positions from European Commission data (2024). For the 2024 elections, a country's net contributor position includes revenues from the NextGenerationEU fund.

We control for strategic and country‐specific factors. First, mainstream parties in government might be more reticent in taking redistributive positions because they might be held electorally accountable for their country's position on the EU level (Schneider, Reference Schneider2019). We, therefore, control for a party's participation in government at the time of an EP election (gov). Second, the success of challenger parties might put electoral pressure on mainstream parties (de Vries & Hobolt, Reference Vries and Hobolt2020; Meijers, Reference Meijers2017). We control for this pressure by adding the vote share challenger parties obtained at the respective EP election in a party's member state (chall_result). Even though mainstream parties cannot know the exact vote share challenger parties will obtain at the next election, they will be aware of polling data that anticipate the support for these parties. Using election results reduces the risk of incoherent polling standards across member states.Footnote 10 Third, we control for the level of integration in a core state power domain (int_lvl). It is arguably likelier to support redistributive integration in an already integrated policy area such as monetary and fiscal policy than in a less integrated field such as taxation (Genschel & Jachtenfuchs, Reference Genschel and Jachtenfuchs2014). We employ Leuffen et al.’s (Reference Leuffen, Rittberger and Schimmelfennig2022) measurement of integration across fields. Finally, we also control for the member state and the year in which a given position was taken by means of country‐ and year‐fixed effects, respectively.Footnote 11, Footnote 12

Empirical analysis

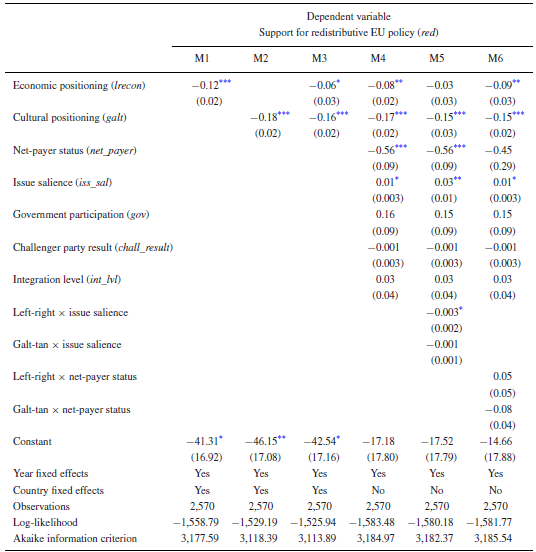

In the first step of the empirical analysis, we employ logistic regression to investigate mainstream party support for redistributive policies across all core state domains in the EUandI data. Models 1 and 2 examine our two ideological variables individually without any controls except for the fixed effects for the country and EP election year. Model 3 includes both independent variables. Model 4 is the full model with our two independent variables issue salience (iss_sal) and a country's net‐payer status (net_payer) as well as our control variables. Finally, Models 5 and 6 include the hypothesized interaction effects between our two ideological independent variables and our two strategic variables issue salience and net‐payer status, respectively. All models include fixed effects for the year of an EP election. The models without a country's net‐payer status also include country‐fixed effects (Models 1–3). Table 2 summarizes the results.

Table 2. Support for redistributive European policies among mainstream parties, 2009–2024

* p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

Individually, both the economic (lrecon) and the cultural party positioning (galt) show the hypothesized directions and are significant in Models 1 and 2, respectively. The further to the right a party is positioned on the economic dimension (i.e., the higher its lrecon score), the less likely it is to lend support to European redistribution. Similarly, for the cultural dimension, the more a mainstream party is positioned towards the culturally conservative end of the spectrum (i.e., the higher its galt score), the lower its likelihood to support redistribution. The effects of both variables remain significant in Model 3 which includes both independent ideology variables. When further including issue salience (iss_sal), net payer status (net_payer) and our controls in the full Model 4, the significant effects persist. The findings thus lend support to our general Hypotheses 1 and 2: Economically left and culturally progressive mainstream parties across the EU are more likely to support European solidarity and the redistributive polity than economically right and culturally conservative parties.

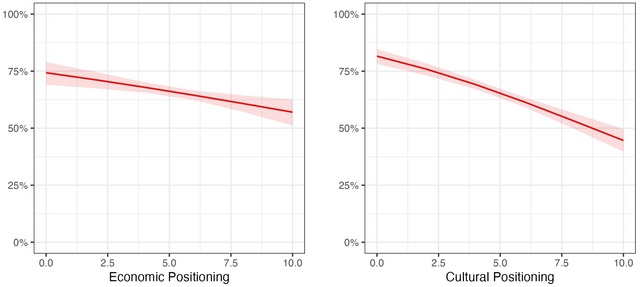

To better gauge effect sizes, we examine the average marginal effects (AMEs) of our independent variables (Figure 1). This analysis reveals that the negative marginal effect of a one‐unit change towards the conservative pole of the cultural dimension is larger than for a move towards the right pole of the economic spectrum. The confidence intervals of both AMEs do not overlap. This indicates that the observation that culturally conservative parties support European redistribution comparably less than economically right‐wing parties is significant. While both the cultural and the economic dimension are significantly correlated with mainstream parties’ positionings on European redistribution, the cultural dimension thus has a larger effect than the economic dimension, confirming previous findings in the literature (Prosser, Reference Prosser2016). Furthermore, over the entire 11‐point scale of our two ideological variables, the marginal effects of both the cultural and the economic dimension are larger than for our binary measure for a member state's net‐payer status, the sole other significant independent variable in our model. The ideological placement of a mainstream party thus has a considerably larger effect on its positioning concerning the redistributive polity than the strategic calculation of the prospective costs of European solidarity.

Figure 1. Average marginal effects of independent variables and controls on party support for redistributive policies (red), Model 4.

Figure 2 further supports these observations. Based on our full Model 4, it plots the predicted probabilities for supporting a redistributive policy across the entire spectrum of the two ideological dimensions. For mainstream parties at the centre of both ideological dimensions, we find very similar predicted levels of support for redistribution. Likewise, mainstream parties towards the economically left and the culturally progressive pole display a similar likelihood to support a redistributive statement, while parties on the culturally progressive pole exhibit a slightly higher likelihood. On the other ends of the two spectrums, the differences are more pronounced. Mainstream parties on the economic right pole still show a likelihood significantly above 50 per cent to support a redistributive statement, while the likelihood of culturally conservative parties drops below 50 per cent. As to be expected from Figure 1, the culturally induced variation on our dependent variable is larger than the economically induced variation. Nonetheless, the change in the probability of support for redistribution is sizable for both dimensions. Over the entire cultural scale, for instance, the probability of supporting European redistributive policies drops from a level above 75 per cent for the most progressive to below 50 per cent for the most conservative parties. Overall, these observations lend further support to Hypotheses 1 and 2: we find more general support for the redistributive polity among economically left and culturally progressive parties than among their competitors from the economically right and culturally conservative pole.

Figure 2. Predicted probabilities of party support for redistributive policies (red) for two main independent variables, economic (lrecon, left) and cultural (galt, right) positionings, based on Model 4.

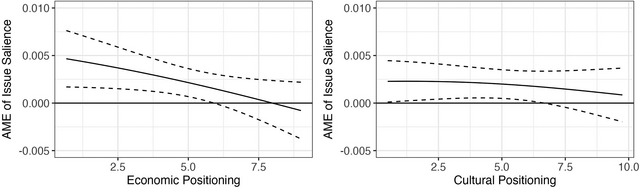

We now probe further into these varieties of pro‐Europeanism among mainstream parties by leveraging strategic domestic‐ and policy‐level differences, as theorized in Hypotheses 3–5. We first examine the hypothesized interaction between issue salience and mainstream party positioning (Hypothesis 3). In Model 5, only the interaction between issue salience and a mainstream party's economic placement is significant. The interaction between salience and a mainstream party's cultural placement, in turn, remains insignificant. To better understand these interactions, Figure 3 plots the AMEs of issue salience on mainstream party support for a redistributive statement across the spectrum of economic and cultural placements. We observe that issue salience has a significant positive effect on mainstream parties left of the centre of this dimension. The effect of salience on mainstream parties on the economic right, however, is insignificant. Our findings thus imply that Hypothesis 3 applies to a mainstream party's economic placement. Even though issue salience has an ambiguous effect on centre‐right and right‐wing mainstream parties, it has a significant and positive effect on mainstream parties towards the left of the political spectrum. An increase in the public salience of a policy domain leads economically left parties, which are already more likely to support redistribution (cf. Hypothesis 1), to lend even more support to redistributive policies. In other words, in times of crises that considerably increase the salience of an issue and require mainstream parties to position themselves on European integration, left‐wing parties are even more likely to put forth solutions in line with the redistributive polity idea than their right‐wing competitors.

Figure 3. Average marginal effects of issue salience (iss_sal) on the likelihood of supporting a redistributive position for different economic (lrecon, left) and cultural (galt, right) positionings of mainstream parties, based on Model 5.

In Figure 3, we observe a similar effect on the cultural positioning of mainstream parties. An increase in the salience of an issue has a positive effect on the likelihood of progressive mainstream parties to support a redistributive statement. In turn, there is no significant effect on mainstream parties on the conservative side. This finding also lends some support to Hypothesis 3 as it implies that culturally progressive parties, which are significantly more likely to support the redistributive polity than their culturally conservative competitors (cf. Hypothesis 2), are even more likely to position themselves in favour of redistributive proposals in the wake of events that increase the salience of an issue.

Next, we examine the effect of a given country's national interest, that is, its expectation of costs and benefits associated with European redistribution. Model 6 examines the interaction between a country's net‐contributing position and mainstream parties’ ideological positionings on their support for redistributive integration (Hypothesis 4). At first, both interactions appear statistically insignificant in our analysis. To gain a better understanding, Figure 4 plots the predicted probabilities of the likelihood of mainstream party support for a redistributive statement across different economic and cultural positionings and a country's net‐payer status.

Figure 4. Predicted probabilities of a redistributive position (red) for interactions between economic (lrecon, left) and cultural (galt, right) positionings of mainstream parties and a country's net‐payer status (net_payer), based on Model 6.

We observe that being in a net‐payer position has a negative effect on mainstream parties’ support for European solidarity across a broad range of the left‐right spectrum. This effect is significant for mainstream parties around the centre of the economic left‐right dimension. However, while this negative effect is significant for all left mainstream parties except for the very left pole, the effect is insignificant for much of the right pole. Both centre‐left and centre‐right mainstream parties from net‐contributing member states are thus less likely to endorse redistribution than their counterparts from net‐receiving member states. The expectation to exercise rather than benefit from transnational solidarity thus reduces the positive effect of a mainstream party's position to the economic left on its likelihood to support a redistributive statement (Hypothesis 1). For right mainstream parties, which generally lend less support to European solidarity anyway, a country's net‐contributing position has a less discernible effect. On the right end of the ideological spectrum, opposition to the redistributive polity does not seem contingent on whether the party's member state would financially benefit or not. Concerning mainstream parties’ cultural positions, the interaction with a country's net‐contributing position is reversed. We do not observe a significant effect of a country's net‐payer status for very progressive mainstream parties. In other words, while culturally progressive mainstream parties are generally more likely to support redistribution than culturally conservative ones (Hypothesis 2), this applies irrespective of their countries’ status as either a net contributor or net receiver from the EU budget. However, we find a significant negative effect of hailing from a net‐contributing country for culturally centrist to conservative parties, the strength of which increases the further we move towards the conservative pole of this dimension. We can thus confirm Hypothesis 4 for centrist to left parties on the economic dimension and for centrist to conservative parties on the cultural dimension. These findings sketch out a coalition in support of European redistribution that comprises left mainstream parties from net‐receiving member states as well as progressive mainstream parties across the EU. Left parties from net‐contributing states, however, are significantly warier to support European solidarity.

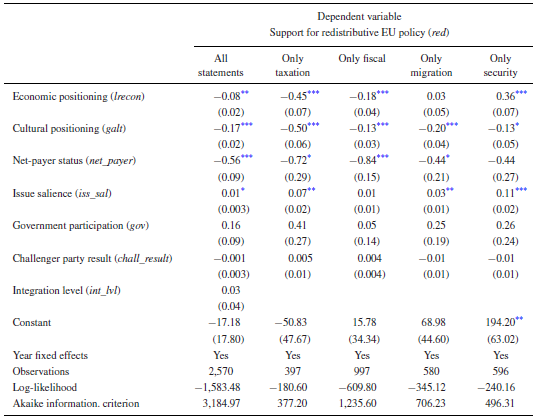

In the final step of our analysis of the varieties of pro‐Europeanism among mainstream parties, we probe further into the differences between the four policy domains which are parts of our dataset. Mainstream party support for redistribution in value‐based domains such as migration and security, we expect, should be driven more strongly by parties’ cultural placement whereas material domains such as fiscal and taxation policy are more strongly tied to parties’ economic stance (Hypothesis 5). Table 3 shows five regression models: the full model (cf. M4 in Table 2) across all statements in our dataset and individual models with mainstream party positions concerning each individual policy domain.

Table 3. Support for redistributive policies across policy domains, 2009–2024

* p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

We turn to the material domains of fiscal and taxation policy first. In both policy areas, mainstream parties’ economic left‐right placement has the expected statistically significant effect (cf. Table 3). While left mainstream parties are more likely to endorse an autonomous tax‐raising power for the EU and redistributive fiscal policies such as Eurobonds, parties of the mainstream right are less likely to support such policies. The cultural positioning, in turn, also has a highly statistically significant effect on parties’ positions on EU tax policy, and less so in the domain of fiscal policy. Figure 5 plots the AMEs of the two ideological variables for our four different policy models. On the issue of taxation, we observe a stronger negative AME of the cultural position than of the economic position. We find the inverse of fiscal policy issues. In both cases, however, the differences between the two dimensions’ AMEs are not significant. This indicates that mainstream party support for redistribution in material policy domains is driven not only by their economic but also by their cultural placement (Hypothesis 5). While parties to the progressive end of the cultural spectrum and the left end of the economic spectrum have a similar probability to support redistribution on taxation, left parties have a higher probability to support redistribution on fiscal and monetary issues than progressive parties (cf. Figures A6 and A7 in the online Appendix) and vice versa. Overall, party positions on the material domains of fiscal and taxation policy are driven by both ideological dimensions. While the cultural dimension has a slightly stronger effect on EU tax policy, the economic dimension has a slightly stronger effect on fiscal policy.

Figure 5. Average marginal effects of economic (lrecon) and cultural (galt) ideological positioning on party support for redistributive policies (red) models with statements from individual policy domains.

We now turn to the value‐based domains of migration and external policy. The dynamics we observe in migration policy conform with our initial theoretical expectations (Hypothesis 5). While the economic placement of a mainstream party has no discernible statistical effect on its support for redistributive migration policies, such as the mandatory relocation and redistribution of refugees in the Schengen area, its cultural placement is statistically significant (cf. Table 3). On external policy, in turn, our initial expectations are contradicted in two manners. First, while the cultural positioning is statistically significant as expected, the effect on redistribution in external security policy is also driven by the economic position. Second, the direction of the effect turns out to be large and inverse from the other domains of core state power integration. While progressive parties indeed favour more European solidarity in matters of security and defence, the mainstream right looks more favourably towards European solidarity in this domain than the mainstream left. These observations are further corroborated by the AMEs (cf. Figure 5) and predicted probabilities (cf. Figures A6 and A7 in the online Appendix) for both dimensions. For migration, while the AME of the economic placement is insignificant, the effect of the cultural dimension is particularly strong. On external security policy, mainstream parties’ cultural and economic placements are both significant, albeit working in different directions. Redistributive EU migration policies thus create mainstream party competition on the cultural dimension rather than the economic one, while external security policy creates mainstream party competition on both the economic and the cultural dimension, with the right favouring more solidarity than the left.

Discussion and conclusion

In response to the salience and polarization of the polycrisis, the benign indifference with which mainstream parties had long treated issues of European integration has given way to a systematic competition about the preferable path towards a future EU. Matters of solidarity and redistribution, whether concerning Eurobonds during the crisis of the common currency or permanent relocation during the crisis of the Schengen area, served as crystallization points of mainstream party competition, dividing them between those demanding European solidarity and those supporting national self‐reliance. Mainstream parties, our paper shows, now compete over European redistribution and cling to different varieties of pro‐Europeanism.

The substantive notion of Europe embraced by mainstream parties is crucially shaped by their ideological commitments. At the most general level, the kind of Europe supported by the progressive left differs quite drastically from the kind of Europe endorsed by the conservative right. Across the EU, more economically right‐wing and more culturally conservative mainstream parties are significantly less likely to support European solidarity in core state domains such as fiscal, taxation, border, and migration policy. Strategic country‐level factors act as moderators of this relationship. For one, during highly salient crises of integration, progressive and left parties double down on their support for transnational solidarity, demonstrating the newfound sincerity with which mainstream parties compete over issues of redistribution. On the other hand, if a country is a net contributor to the EU budget, this ‘national interest’ tends to suppress parties’ support for European solidarity due to the expected domestic fiscal and ultimately electoral costs. This applies particularly to parties of the mainstream left which otherwise strongly support European redistribution. Culturally progressive parties from net‐contributing member states, however, are unmoved by their countries’ expected solidarity costs. In other words, progressive mainstream parties’ stronger support for redistribution is less contingent on considerations of the ‘national interest’.

Furthermore, we find differing logics of mainstream party competition across different fields of core state power integration. In taxation and fiscal policy, both the cultural and the economic dimension have a significant impact on mainstream party positions on European solidarity, with the expected dynamic between left and progressive parties and right and conservative parties. On matters of asylum and migration, the cultural dimension alone drives mainstream party competition. Matters of external security, in turn, are the sole policy field where parties of the mainstream right are more supportive of European solidarity than their left‐wing contenders. This points towards an unusual coalition of culturally progressive and economic right‐wing parties that favour European solidarity in the domain of security and defence. Our findings thus suggest the existence of varieties of pro‐Europeanism among mainstream parties across different policy domains of European integration. While culturally conservative parties support the regulatory status quo and culturally progressive parties endorse more European solidarity in all domains, economic left parties focus on material policy areas such as fiscal and taxation policy and parties of the economic right emphasize solidarity in matters of security and defence. The latter aspect is particularly relevant against the backdrop of conflicts in the EU's neighbourhood such as Russia's war against Ukraine.

Our findings have broader implications for the future of European integration. First, if mainstream parties support distinct notions of the EU and if they differentiate their understanding of the EU across different policy domains, they provide their electorate with clearer choices. This holds the potential of reducing some of the Eurosceptic challenger parties’ electoral appeal by providing genuine and consistent alternatives within a generally pro‐EU frame. Second, while an increasing rift between mainstream parties holds the potential of increasing deadlock within EU institutions and thus for voters’ frustration with European politics, it might also provide opportunities for new coalitions around European solidarity. On matters of fiscal policy, for instance, left parties in net‐contributing member states are in a pivotal position. While they are significantly less supportive of redistributive integration than left parties from net‐receiving countries, the salience of integration crises could counteract and partly offset this effect. Moreover, progressive parties’ support for fiscal redistribution depends less on narrow considerations of the national interest. In instances of severe crisis, economic left and culturally progressive parties could thus push for redistributive fiscal policies even if their own member state would need to contribute more in the short‐run than it receives.

We currently see four paths to further substantiate our findings in future studies. First, the ‘EUandI’ vote advice application provides unique data that allows for an in‐depth comparison of party positions on substantive issues of European integration across all member states. However, its main focus is not on core state power integration and redistributive issues. Systematically gathering data on mainstream party competition over European solidarity could thus further substantiate our findings. Second, future research ought to further explore the differences we discern across policy domains. Mainstream party positionings on transnational solidarity differ significantly across value‐driven and materially driven areas of integration, with external security being the sole domain in which right‐wing mainstream parties support solidarity more than the left. A full analysis of the drivers and effects of this pattern is beyond the scope of this article and should be attempted in further analyses of the party politics of European solidarity. Third, it has recently been shown that recipient characteristics and especially rule of law concerns have a significant impact on citizens’ support for transnational solidarity (Heermann et al., Reference Heermann, Koos and Leuffen2023). While the rule of law does not figure among the classic definitions of core state powers (Genschel & Jachtenfuchs, Reference Genschel and Jachtenfuchs2014) and the issue is difficult to locate on the spectrum between regulation and redistribution, concerns about the rule of law in recipient countries could act as a decisive moderator of mainstream party support for European solidarity. This aspect should be factored in in future analyses of dyadic data on European redistribution. Fourth, it would be important to identify the effects of these varieties of pro‐Europeanism regarding redistribution on the actual dynamics of European integration. Although parties’ positions are driven by ideological factors, once they enter government, they face cross‐pressures that might lead them to attenuate their convictions on transnational solidarity. For the EU to integrate core state powers in a more sustainable and less crisis‐prone manner (cf. Genschel & Jachtenfuchs, Reference Genschel and Jachtenfuchs2018), however, it would be important that mainstream parties across the spectrum not only talk the talk of European solidarity but also walk the walk when in positions of power.

Data Availability Statement

Data and replication files are available here: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/23IQZB.

Acknowledgements

This article would not have come to pass without the tremendous work of the EUandI project team (especially Álvaro Canalejo‐Molero, Lorenzo Cicchi, Frederico Ferreira da Silva, Diego Garzia, Andres Reiljan, and Alexander Trechsel). We are particularly grateful for their generosity in providing us with their, as of yet unpublished, data on the 2024 European Parliament election. We gratefully acknowledge the dedicated research assistance by Elizabeth Schilpp. We also want to extend our sincere thanks to Sophia Hunger, Andrea Lenschow, Jana Lipps, Giorgio Malet, Eva Ruffing, Frank Schimmelfennig, the members of the European politics research group at ETH Zurich and the EU politics colloquium at the University of Osnabrück, and the audiences at the EPSA conference in Glasgow (2023), the ECPR General Conference in Prague (2023), and the SGEU conference in Lisbon (2024). We are grateful for the tremendously helpful advice we received from the five reviewers and the editorial team of the European Journal of Political Research.

Online Appendix

Additional supporting information may be found in the Online Appendix section at the end of the article:

Supporting Information