Introduction

a. Historical and Functional Role of Working Dogs

Canines have been part of human society and culture for millennia, with archaeological evidence indicating domesticated dogs dating back 33,000 years.Reference Wang, Zhai and Yang 1 Canines have historically served as companions and working animals, playing diverse roles such as herding, hunting, and protection.Reference Wang, Zhai and Yang 1 Archaeological records illustrate that dogs have been involved in these activities for nearly 10,000 years, with the first documented use of war dogs dating to Greece in 600 BC.Reference Hall, Johnston and Bray 2 The domestication, development, and training of canines is arguably the first use of animal biotechnology.Reference Bethke and Burtt 3

In the modern age, many dog breeds have transitioned to the role of companion animals. However, several breeds, including the German Shepherd, the Belgian Malinois, the Labrador Retriever, the Golden Retriever, and the Bloodhound, are still commonly employed for work.Reference Otto, Darling and Murphy 4 –Reference Ridgway 6 These breeds are valued and bred for their work drive, agility, keen sense of smell, and trainability, although any breed can be trained for work.Reference Otto, Darling and Murphy 4 Canines possess an extraordinary olfactory ability, detecting odors as low as one part per trillion.Reference Singletary and Lazarowski 7 Their sense of smell far exceeds the sensitivity of traditional analytic chemistry equipment, which typically detects odors at one part per billion.Reference Otto, Cobb and Wilsson 8 The working canines’ detection capabilities, alongside traits such as on-command aggression and overall trainability, render them irreplaceable and virtually unmatched by modern technology.

b. Current Challenges in Operational K9 Medical Support

The demand in the United States for specially trained working dogs has surged in the 21st century due to increased military operations as well as human-made and natural disasters.Reference Hanel, Palmer and Baker 9 –Reference Kryda, Mitek and McMichael 11 Operational Canines (OpK9s) are working canines that are specifically trained to support federal and local law enforcement, the military, and other special operations. They engage in tactical operations, including detection, security, and search and rescue.Reference Otto, Darling and Murphy 4 , Reference Palmer 10 , 12 Once trained and deployed under the direction of a Canine Handler (K9 Handler), OpK9s function as disaster relief force multipliers, sustaining Search and Rescue(SNR) recovery operations, enhancing law enforcement’s efficiency and effectiveness, and amplifying governmental agencies’ abilities to protect and serve the public.Reference Palmer 10 , 12 –Reference Schoenfeld, Thomas and Palmer 14 It is estimated that approximately 50,000 OpK9s are deployed in the United States.Reference Schoenfeld, Thomas and Palmer 14 However, training these animals is resource-intensive, requiring significant time, personnel, and financial investments. The cost of a fully-trained working dog can exceed $65,000.Reference Ridgway 6 , Reference Palmer 10 , 12 , 15

Although each OpK9 represents a significant investment, their roles within law enforcement, SAR, and disaster deployment place them at high risk of suffering a debilitating physical injury.Reference Hanel, Palmer and Baker 9 , Reference Comitre, Palmer and Bacek 16 OpK9s are integral members of the disaster deployment teams, with the first canines being used for SAR in Switzerland as early as the 1700s.Reference Fenton 17 In recent history, OpK9s have been deployed to disasters including 9/11, Hurricane Katrina, and wildfires, including those in Bastrop County, Texas and the California Camp Fire.Reference Bauer 18 –Reference Gordon and Ho 21 To safeguard these investments and maintain their operational readiness, it is essential that OpK9s receive basic wellness care such as regular veterinarian physical examinations, core vaccinations, and parasite prevention before entering the field and, when necessary, emergency treatment while in the field.

Comprehensive wellness monitoring via a veterinarian promotes overall physical and behavioral health and can mitigate or even prevent some field emergencies, such as gastric dilatation and volvulus (GDV).Reference Ridgway 6 Other field emergencies, such as gunshot wounds, are unavoidable and require immediate medical attention. In emergency field situations, veterinary personnel are often unavailable, and immediate response falls to whoever is on scene. Most often, immediate response is conducted by K9 Handlers. However, it is important to note that during an emergency deployment, SNR operation, or other OpK9 emergency field situation, K9 handlers may be incapacitated, become separated from their K9 partner, or lack necessary medical supplies or knowledge to treat an injured OpK9. It is at this point other Law Enforcement Officers (LEOs) and Emergency Medical Service (EMS) personnel who have the equipment and are also present on scene would administer emergency care to OpK9s.Reference Comitre, Palmer and Bacek 16 , Reference Palmer 22 Care should be administered in adherence to ethical oversight and animal welfare regulations to ensure humane and professional standards during field interventions; however, these are complex regulations which are context-specific and highly dependent on a number of individual factors.Reference Cobb, Otto and Fine 23

c. Need for a National Standardized Training Program

Despite OpK9s’ utility and the investment required to train them, there are no nationally standardized pre-veterinary care standards, emergency treatment protocols, or training programs for personnel tasked with treating them while injured in the line of duty.Reference Hanel, Palmer and Baker 9 , Reference Schoenfeld, Thomas and Palmer 14 This lack of nationally standardized protocols forces OpK9s to work in austere environments without access to emergency care, jeopardizing their health and safety.

The Canine Tactical Combat Casualty Care (C-TCCC) principles, used for Military Working Dogs (MWDs), have provided a foundation for developing OpK9 emergency training protocols. 24 However, C-TCCC has limitations when applied to civilian OpK9s (non-military working dogs).Reference Hanel, Palmer and Baker 9 , 24 First, C-TCCC was developed for use in the military context, where the types of danger and availability of resources may be significantly different compared to civilian contexts. 24 Because C-TCCC was based on human combat casualty care principles, it also does not address life-threatening conditions that are unique to or significantly more common in OpK9s, such as heat-related injuries, GDV, and exposure to illicit drugs or explosive compounds. 24

To address these gaps, the K9 Tactical Emergency Casualty Care (K9-TECC) working group was established in 2014 under the oversight of the Committee for Tactical Emergency Casualty Care.Reference Hanel, Palmer and Baker 9 , Reference Palmer and Yee 25 K9-TECC developed first aid guidelines for OpK9s, designed for first responders such as K9 Handlers, LEOs, and EMS personnel.Reference Palmer and Yee 25 , 26 Additionally, in 2016, the American College of Veterinary Emergency and Critical Care’s Veterinary Committee on Trauma (VetCOT) published the Best Practice Recommendations for Prehospital Veterinary Care for Dogs and Cats Guidelines, recognizing the need for standardized field care for injured animals.Reference Hanel, Palmer and Baker 9 Both the K9-TECC and VetCOT guidelines are intended to be used not only by veterinary personnel but also by qualified first responders such as K9 Handlers, LEOs, and EMS personnel who have received appropriate training to provide the best outcome for an injured OpK9 during a medical emergency.Reference Hanel, Palmer and Baker 9 , Reference Palmer and Yee 25

Although the VetCOT and K9-TECC guidelines are more applicable to OpK9s than C-TCCC, VetCOT and K9-TECC are still not recognized as national standards. As discussed in more detail below, EMS personnel were legally prohibited from providing emergency treatment to OpK9s in most states until very recently, limiting the guidelines’ applicability. Additionally, VetCOT guidelines mainly focus on pre-veterinary care for non-tactical companion animals; they do not take into account some constraints of providing trauma care during high-threat situations.Reference Hanel, Palmer and Baker 9 , 24 By contrast, the K9-TECC guidelines were meant to apply to both OpK9s and MWDs. 26 Due to this broad scope, some aspects of K9-TECC training are less relevant to OpK9s. Table 1 provides a comparative summary of existing OpK9 guidelines.

Table 1. Comparison of existing OpK9 guidelines

There exists a pressing need for a nationally standardized training program for first responders to ensure species-specific emergency care is available to OpK9s during disaster events. This article proposes such a program, which was developed in collaboration with veterinary professionals and key stakeholders and builds upon established guidelines from K9-TECC and VetCOT. The proposed training curricula are more narrowly tailored to OpK9s than either VetCOT or K9-TECC, allowing participants to focus on the emergencies and interventions most likely to occur or be needed in the field. The curricula are also tailored to the unique knowledge and skill sets of the target audiences to maximize the training’s effectiveness.Reference Schoenfeld, Thomas and Palmer 14 , Reference Palmer 22 Finally, the proposed program capitalizes on the recent legislative appetite to ensure that OpK9s receive emergency treatment in the field, providing a solution for first responders who are currently underprepared. This national curriculum for first responders can serve as a basis for stakeholders to revise and adapt for state-specific legal standards and emergency situational contexts.

Discussion

Training the K9 Handler and Law Enforcement Officers

K9 Handlers are responsible for the continuous care, conditioning, and training required to maintain their OpK9s’ health, operational readiness, and certification standards. The bond between a K9 Handler and their OpK9 is exceptionally strong, with the K9 Handler being the individual most familiar with the OpK9’s behavior and needs. In an OpK9 emergency, the K9 Handler will likely be the first on-site and is best equipped to safely manage the animal, making them the logical starting point for training.Reference Otto, Darling and Murphy 4 –Reference Ridgway 6 , 12 Others who frequently work alongside OpK9 teams should also receive training to provide additional support for K9 Handlers and act as the first responder if the K9 Handler is injured or unavailable.

The proposed training curriculum for first responders (K9 Handlers and LEOs) builds on their preexisting knowledge and skill sets while filling crucial gaps. Although some K9 Handlers have emergency medical training for humans, such as Basic Life Support, many K9 Handlers receive little to no training in wellness care, first aid, or trauma care for canines.Reference Hanel, Palmer and Baker 9 , Reference Palmer 22 , Reference Lagutchik, Baker and Balser 27 To maintain their OpK9s’ health and reduce the possibility of a preventable emergency arising in the field, K9 Handlers must be educated on the importance of regular wellness care, but they specifically need training in canine first aid and trauma care to address emergencies that arise in the field.

Table 2 outlines a proposed OpK9 Emergency Medical Training Curriculum for First Responders (K9 Handlers and LEOs), including specific learning objectives and skill sets.Reference Hanel, Palmer and Baker 9 , Reference Palmer 22 , Reference Pappal, St. Jean and Engle 28 –Reference Fletcher, Boller and Brainard 30 The proposed curriculum focuses on preventative wellness care and basic emergency first aid, with intervention training tailored to the participants’ skill level and background. This training is not intended to replace veterinary care. Instead, the training goal is to provide first responders with the knowledge and skills to maintain the OpK9’s health prior to entering the field and administer emergency treatment in the field until the OpK9 can receive definitive care from a veterinary professional. Unlike previous initiatives and trainings which were either too broad (K9-TECC) or too narrow (C-TCCC), the proposed curriculum represents a national baseline for emergency medical training for OpK9s and recognizes the importance of the real-world environment where OpK9s are utilized in field operations.

Table 2. Proposed OpK9 emergency medical training curriculum for first responders (K9 Handlers and Law Enforcement Officers (LEOs)) Reference Hanel, Palmer and Baker 9 , Reference Fenton 17 , Reference Palmer 22 – 24

CPR = cardiopulmonary resuscitation; EMS = Emergency Medical Service; GDV = gastric; dilatation and volvulus; K9 Handler = Canine Handler; LEO = Law Enforcement Officer; OpK9 = Operational Canine.

* The acronym M3ARCH2, used in canine casualty assessment, was created for the U.S. Army’s Tactical Combat Casualty Care Handbook.Reference Palmer 22 M3ARCH2, however, only considers the assessment of hypothermia. M3ARCH3 allows for the addition of hyperthermia to the assessment.

The OpK9 Emergency Medical Training Curriculum for First Responders (K9 Handlers and LEOs) prioritizes safety considerations of providers of emergency medical care. These include K9 Handlers, LEO, and EMS personnel. OpK9s can exert a bite force of up to 800 psi and are trained to release only on command,Reference Kryda, Mitek and McMichael 11 necessitating proper handling and restraint techniques before attempting any intervention. The K9 Handler is always the primary option for handling and restraining the OpK9.Reference Lagutchik, Baker and Balser 27 While K9 Handlers are skilled at managing the daily operations of OpK9s, additional training is required to handle an injured animal. Even with a known K9 Handler, injured animals can act erratically and aggressively.Reference Hall, Johnston and Bray 2 Improper restraint techniques can cause further injury to the OpK9 and harm the person administering care. K9 Handlers must be competent in correctly using leashes and muzzles and be able to direct emergency personnel in their application.Reference Lagutchik, Baker and Balser 27 It is also important to prepare K9 Handlers for scenarios where they may need to handle dogs other than their own, such as when another K9 Handler is incapacitated and unable to handle their injured OpK9. In such cases, another trained K9 Handler is the safest and most appropriate individual to manage the injured OpK9. When no trained K9 Handlers are available, other first responders who have received this training should attempt to restrain and treat the OpK9.

This curriculum also trains participants in key aspects of routine health care, which can increase the OpK9’s overall health and decrease the likelihood of some preventable emergencies arising in the field. K9 Handlers must work closely with veterinarians to ensure that OpK9s receive routine physical examinations, blood work, infectious disease testing, appropriate housing and travel conditions, immunizations and documentation, parasite control, sterilization, and gastropexies.Reference Ridgway 6 , Reference Lagutchik, Baker and Balser 27 Special attention must be given to the prevention of GDV, a life-threatening condition in canines, the fifth leading cause of death in MWDs, and a potential outcome during OpK9 fieldwork.Reference McGraw and Thomas 5 , Reference Ridgway 6 A preventive gastropexy, which surgically affixes the stomach to the abdominal wall, can significantly reduce the risk of GDV.Reference McGraw and Thomas 5 , Reference Ridgway 6 Blood typing must also be considered. The animal’s blood type information can be placed on the animal’s collar or tags for easy reference by veterinary professionals. K9 Handlers must be able to convey all wellness information to veterinary professionals during emergency care.

Along with safety and wellness training, the proposed curriculum educates first responders, particularly K9 Handlers and LEOs, on recognizing abnormal canine behavior while in the field, which can be a sign that the OpK9 is experiencing an acute injury. Upon recognizing signs of an injury, K9 Handlers will learn how to obtain a cursory physical examination and vitals on the OpK9 and assess with M3ARCH3. The proposed curriculum will develop the K9 Handler’s ability to identify a variety of potential emergencies and apply situational-specific emergency interventions. Once situational emergencies are identified, K9 Handlers can begin life-saving interventions.

Because medical equipment is required to adequately treat many field emergencies, participants will also learn about what supplies should be included in an OpK9 First Aid Emergency Kit. To ensure quality emergency care, all K9 Handlers should carry an OpK9 First Aid Emergency Kit with the recommended supplies listed in Table 3. 12 , Reference Palmer and Yee 25 , Reference Lagutchik, Baker and Balser 27

Table 3. OpK9 first aid pack list for K9 Handlers with recommended equipment, sizes, and quantities 12 , Reference Bauer 18 , Reference Migala and Brown 20

in = inch; IV = intravenous; ga = gauge; K9 Handlers = Canine Handlers; mL = milliliter; mm = millimeter; OpK9 = Operational Canine.

Finally, the proposed curriculum provides training on poison control resources. K9 Handlers should familiarize themselves with the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals Animal Poison Control Center and the Pet Poison Control Hotline, both of which offer consultation services for an average fee of $90. 31 , 32 It is advisable for first responders to establish preexisting accounts with these services, ensuring that K9 Handlers, LEOs, and trained EMS personnel can quickly access poison control advice in the field without delay.

The OpK9 Emergency Medical Training Curriculum for First Responders (K9 Handlers and LEOs) should be taught by a licensed veterinarian, veterinary nurse, or veterinary technician. Refresher courses should be offered regularly, especially for K9 Handlers, to maintain and refine their skills.

Training EMS Personnel

Given the infrequency of OpK9 field emergencies, achieving comprehensive proficiency in OpK9 emergency interventions may be impractical for some EMS personnel. However, EMS personnel are often present on the scene for OpK9 field emergencies, 24 and their medical training and equipment make them well-suited to provide emergency treatment. Establishing a nationally recognized and standardized first responder training curriculum or certification program for OpK9 field emergencies is essential to ensure that OpK9s receive competent, species-specific emergency care before they can be seen by veterinary personnel. Given the limited occurrence of OpK9 emergencies and the constraints of time and funding for training, priority should be given to first responders who frequently interact with OpK9s, such as tactically embedded EMS teams or those operating in areas prone to disasters.

When designing an OpK9 emergency care curriculum for EMS personnel, it is important to recognize their extensive training in human emergency medicine. EMS personnel are highly trained in areas such as anatomy, pharmacology, phlebotomy, fluid management, and Prehospital Trauma Life Support, which can be adapted to a certain extent for OpK9 care.Reference Hanel, Palmer and Baker 9 , 33 Additionally, EMS personnel are often on-site and typically have access to much of the equipment and supplies required for pre-veterinary emergency interventions, including many of the items described in Table 3.

Table 4 outlines a proposed OpK9 Emergency Medical Training Curriculum for First Responders (EMS Personnel), detailing specific learning objectives and essential skills to be covered.Reference Hanel, Palmer and Baker 9 , Reference Palmer 22 , Reference Barr, Haughan and Gianotti 29 , Reference Fletcher, Boller and Brainard 30 The curriculum for EMS personnel aligns with the curriculum developed for K9 Handlers and LEOs, but with greater emphasis on safety when working with animals and providing medical interventions. Initial training focuses on safely restraining canines, recognizing anatomical landmarks, conducting baseline assessments, obtaining vital signs, and mastering basic intervention techniques.

Table 4. Proposed OpK9 emergency medical training curriculum for first responders (EMS personnel)Reference Hanel, Palmer and Baker 9 , Reference Fenton 17 , Reference Cobb, Otto and Fine 23 , 24

CPR = cardiopulmonary resuscitation; EMS = Emergency Medical Service; GDV = gastric dilatation and volvulus; IV = intravenous; K9 Handler = Canine Handler; LEO = Law Enforcement Officer; OpK9 = Operational Canine.

EMS personnel typically lack training in managing an OpK9, making safety considerations the top priority of any training program. As previously discussed, injured OpK9s can present a significant danger to anyone attempting an emergency intervention.Reference Kryda, Mitek and McMichael 11 If the primary K9 Handler cannot restrain the OpK9, employing another first responder, such as a K9 Handler or other trained LEO, is the recommended alternative. When EMS personnel must handle the OpK9 without a K9 Handler or other trained LEO, they should never act alone and only proceed with the animal muzzled and with extreme caution. No intervention should be attempted if EMS personnel cannot safely muzzle the OpK9. Proper muzzle placement is also vital to the OpK9’s health, as panting is the primary mechanism for heat dissipation in canines. Improper muzzle selection or placement could harm the animal further. EMS personnel must be trained in properly using and placing muzzles and leashes and recognizing animal behavior to ensure safe and effective treatment of an injured OpK9.

Like the curriculum for K9 Handlers and LEOs, the curriculum for EMS personnel should be taught by licensed veterinary professionals, such as a veterinarian, veterinary nurse, or veterinary technician. After participating in an initial training, EMS personnel should receive regular continuing education to refine and reinforce their skills.

Key Considerations

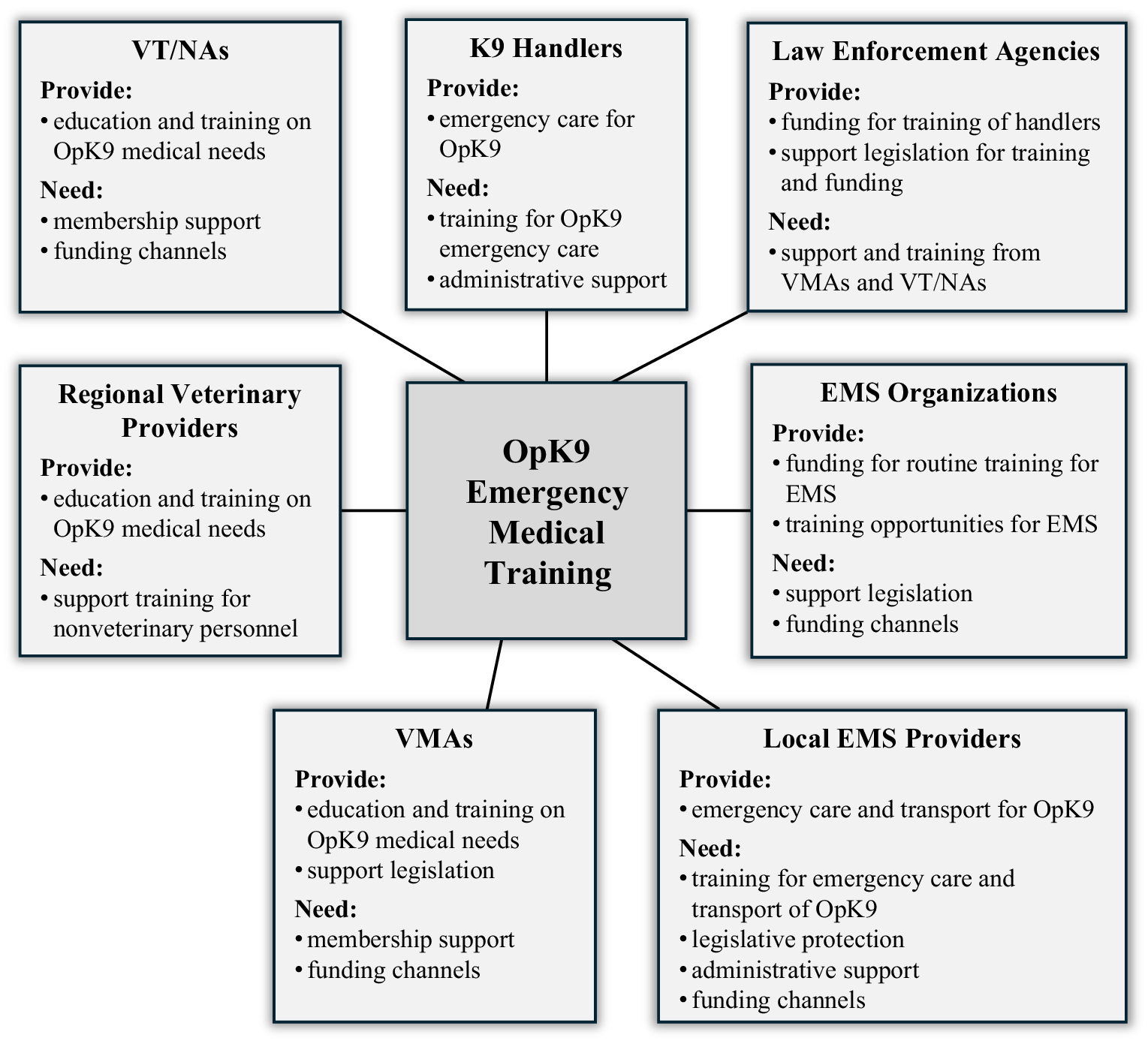

Critical concepts must be considered when developing a nationally standardized training curriculum for First Responders. First, it is essential to recognize that OpK9s (along with any animal) are legally considered property of the agency, organization, or individual who owns them. 34 Acquiring prior permission to treat the OpK9 in an emergency establishes protocols that define permissible emergency interventions. Second, due to legal restrictions on nonveterinary personnel providing medical care to canines, EMS personnel must be aware of relevant legislation specific to their state of employment.Reference Hanel, Palmer and Baker 9 , Reference Kryda, Mitek and McMichael 11 A third consideration is fostering collaboration between key stakeholders, including law enforcement, local EMS providers, EMS organizations such as the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration Office of EMS, veterinary medical associations (VMAs), veterinary technician/nurse associations (VT/NAs), and regional veterinarians. Figure 1 highlights the roles of key stakeholders in canine emergency medical training. Each bubble explains the stakeholder’s role in caring for OpK9s and what needs should be met to ensure this care is provided.

Figure 1. Roles of key stakeholders in OpK9 emergency medical training.

Collaborative efforts across these stakeholders should focus on establishing and disseminating standardized care protocols for canine emergency medical training, implementing practical skills training for first responders and EMS personnel, and advocating for legislation permitting EMS personnel to administer potentially life-saving care to OpK9s in emergencies. Additionally, continuous collaboration is required to secure sustainable funding to maintain these training programs and resources.

Limitations

The ability of K9 Handlers, LEOs, and EMS personnel to provide an OpK9 with emergency care while in the field has several limitations. One major obstacle is legislation that prevents EMS personnel from rendering emergency care to OpK9s.Reference Hanel, Palmer and Baker 9 –Reference Kryda, Mitek and McMichael 11 , Reference Weir, Mitek and Smith 35 To protect its residents, each state requires those who wish to practice veterinary medicine to obtain a license.Reference Flemming 36 While there are slight differences in states’ definitions of “practice of veterinary medicine,” directly providing medical treatment to an animal owned by a third party falls squarely within each state’s definition.Reference Bethke and Burtt 3 Thus, absent an exception, EMS personnel are generally prohibited from providing emergency treatment to OpK9s.Reference Palmer 10 , Reference Kryda, Mitek and McMichael 11 , Reference Schoenfeld, Thomas and Palmer 14 , Reference Flemming 36 Nevertheless, state legislatures have increasingly come to recognize the value of allowing EMS personnel to provide emergency treatment for OpK9s, causing a notable legislative shift within the past 11 years. In 2014, Colorado became the first state to pass a law allowing EMS personnel to provide emergency treatment for OpK9s. 37 As of 2025, 17 states allow EMS personnel to provide pre-veterinary care to an OpK9 in the event of a canine field emergency, and 15 states authorize EMS personnel to transport injured OpK9s to a veterinary clinic. 37 – 61

Table 5 provides an overview of current laws regarding the involvement of EMS personnel in OpK9 medical emergencies, including when each law was enacted and what it contains or authorizes: emergency treatment, transportation of the canine to a veterinary facility, specific authorized medical interventions, immunity for care providers, and naloxone administration. 37 – 61 These laws represent a substantial change and highlight the increasing need for a nationally standardized training program on canine emergency first aid. However, most of this legislation lacks standardized treatment protocols or training recommendations. This absence of clear legislative guidance allows for the continuation of undue environmental risk for the OpK9. Collectively, these laws demonstrate a gradual policy shift from restriction to regulated empowerment of EMS providers, yet the absence of standardized training guidance hampers implementation. The legal landscape is constantly evolving and changing, which further highlights the desperate need for a national curriculum which serves as a baseline that can then be adapted to fit state restrictions.

Table 5. State laws regarding the provision of pre-veterinary treatment or transportation by EMS personnel 37 – 61

EMS = Emergency Medical Service.

* The law generally authorizes “emergency treatment” and lists specific interventions, such as cardiopulmonary resuscitation, in the context of authorizing ambulance services to develop policies regarding training on these interventions.

† The law discusses naloxone in the context of authorizing ambulance services to develop policies regarding training.

‡ The law offers limited immunity, allowing for liability in certain cases.

§ The law authorizes EMS to administer an “overdose reversal drug” without specifying naloxone.

Funding insufficiency may also be a barrier to widespread implementation of this proposed nationally standardized curriculum, especially for EMS providers and agencies. While the Department of Homeland Security offers grant funding for agencies that own working dogs, these funds are not specifically allocated for OpK9 emergency medical training. 62 The grant recipient would have to choose to use the funding for OpK9 emergency training, rather than for other eligible purposes. Additionally, EMS resources used during OpK9 emergencies are typically not reimbursed, with costs likely falling on the OpK9’s owner or managing agency.

Successful implementation of this proposed nationally standardized curriculum relies on securing the commitment and support of key stakeholders. Some, such as veterinary professionals and emergency management agencies, have expressed reservations about allowing nonveterinary personnel to treat OpK9s, citing concerns about liability and training. However, the reality is that OpK9s are regularly deployed in dangerous situations, so at least some field emergencies will occur. Because K9 Handlers, other LEOs, and EMS personnel are the most likely first responders in an OpK9 field emergency, it is imperative that they be trained on how to effectively treat OpK9s while keeping the animals and themselves safe. Based on legislative trends over the past 11 years, this will only grow more true as states increasingly authorize EMS personnel to provide emergency treatment to OpK9s. Neglecting to train K9 Handlers, LEOs, and EMS personnel not only risks the health and safety of valuable investments (the OpK9s) but it also puts the first responders themselves at risk. Future studies should assess the effectiveness of the proposed curriculum through pilot implementation and longitudinal evaluation of K9 handler and EMS competency in providing emergency medical care.

Conclusion

A nationally standardized training program for first responders such as K9 Handlers, LEOs, and EMS personnel is needed to render species-specific emergency medical care to OpK9s. Currently, no such standardized training exists, leaving a critical gap in the ability of K9 Handlers, LEOs, and EMS personnel to manage medical crises involving OpK9s effectively. This lack of uniform training increases the risk to these valuable working animals during emergencies. Developing a nationally recognized training curriculum for first responders is urgently needed to address this issue as previous curriculums have focused on either military dogs or working dogs more broadly, leaving a significant gap related to OpK9s who may be injured in the course of their duties. Utilizing existing training frameworks and focusing on the real-world context of OpK9s, this curriculum represents a culmination of best practices and offers a baseline for training that can be adapted to state-specific laws and regulations. Integration of this program within existing training structures could streamline adoption and ensure sustainability. The standardized curriculum proposed in this article can be effectively implemented through collaboration among key stakeholders, including law enforcement, emergency management, and veterinary medicine professionals.

Author contribution

Anna Santos: Conceptualization, Writing—Original Draft, Visualization; Alexander Lott: Writing—Review and Editing; Curt Harris: Writing—Review and Editing, Supervision; Morgan Taylor: Writing—Review and Editing, Supervision.

Competing interests

None.

Sources of support

There are no sources of support that require acknowledgement.

IRB statement

No IRB is required since no human research was involved.