Introduction

The Cantabrian Region

The Cantabrian Region (comprising today, from west to east, the modern autonomous regions of Asturias, Cantabria and the coastal Basque provinces of Vizcaya and Guipuzcoa, plus the northernmost part of Navarra) displays one of the most abundant and diverse archaeological records in southwestern Europe that spans the late Middle Pleistocene to the Holocene. There is a long tradition in Paleolithic research from the late 19th century, beginning with the discovery of Altamira paintings and continuing during the early 20th century with the work of Obermaier, Breuil and Alcalde del Rio that led to the discovery of many new archaeological sites, some with important cave art manifestations (e.g., Alcalde del Río et al. Reference Alcalde del Río, Breuil and Sierra1911; Breuil and Obermaier Reference Breuil and Obermaier1914; Sanz de Sautuola Reference Sanz de Sautuola1880). There are several key sites for understanding the Middle to Upper Paleolithic transition and the use of the region as a refugium for human populations during MIS 3 and MIS2 that have been studied with a multidisciplinary approach (for an updated state of the art syntheses, see Straus 2015, 2018a, 2018b, despite the scarcity of finds of human remains (Fu et al. Reference Fu, Posth, Hadjinjak, Petr, Mallick, Fernandes, Furtwängler, Haak, Meyer and Mittnik2016; Straus et al. Reference Straus, González Morales, Carretero and Marín-Arroyo2015).

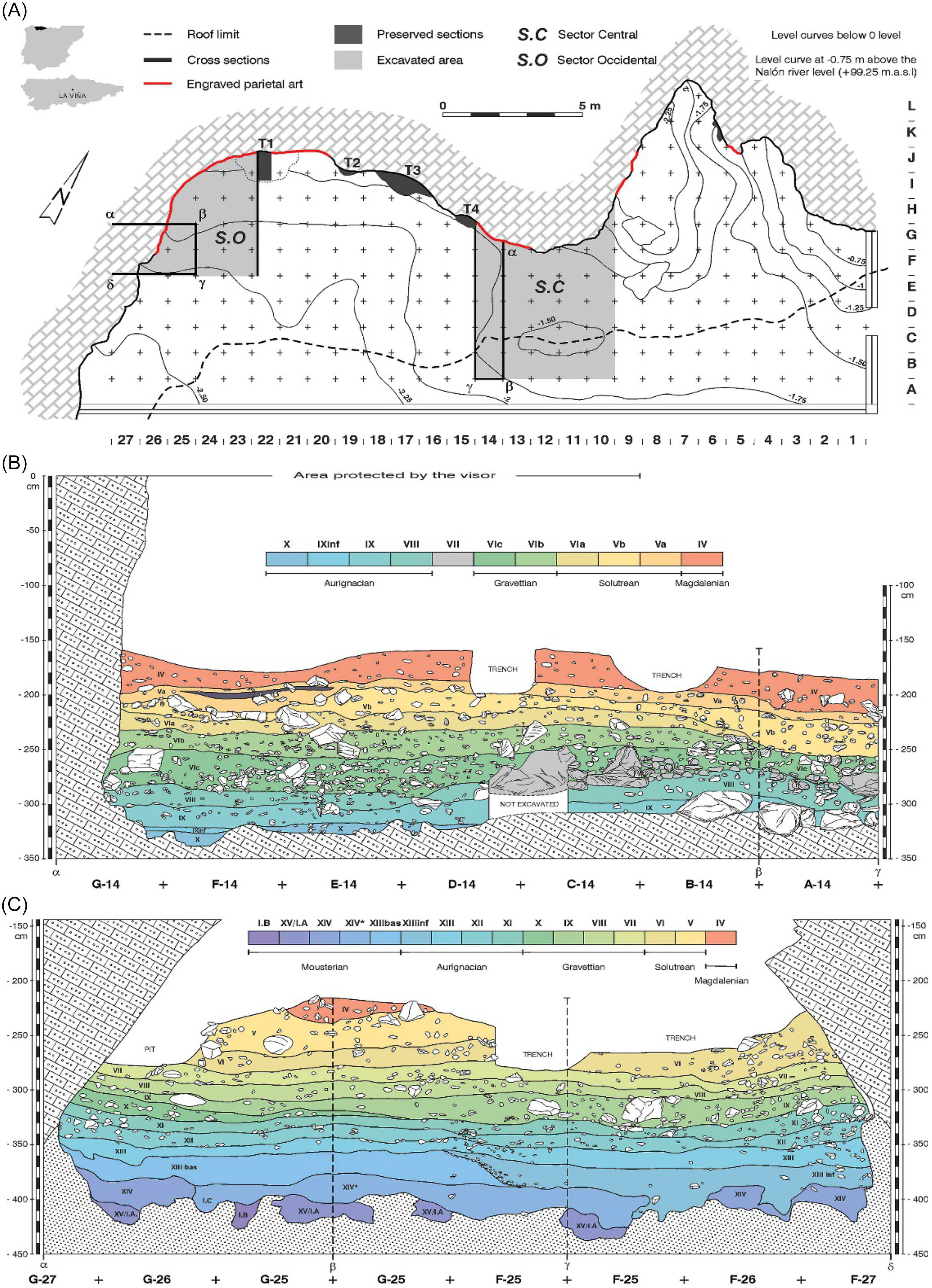

Here, we present the complete radiocarbon-dated sequence of La Viña rock shelter, aided with two Bayesian models used to assess precision for the start and end dates of each of the Upper Palaeolithic cultures defined at the site and to evaluate their consistency within the accepted scheme of regional cultural techno-complexes. La Viña, is one of the most important sites in the Cantabrian region because it contains evidence of continuous human occupation since the late Mousterian, through the culture—historical periods known as the Aurignacian, Gravettian, Solutrean and Magdalenian (Figure 1). Although it was excavated between 1980 and 1996 by the late Professor Javier Fortea, the upper part of the stratigraphic sequence in the western sector and the lower part in the central sector had remained poorly dated (Fortea Pérez Reference Fortea Pérez1990, Reference Fortea Pérez1992, Reference Fortea Pérez1995, Reference Fortea Pérez1999, Reference Fortea Pérez and Noiret2001). Recent radiocarbon dates done with new ultrafiltration methods on bone collagen and ABOx-SC on charcoal on the Mousterian and Early Upper Paleolithic levels were applied to test the chronology for the Mousterian in level XIII (basal) and to provide a more secure chronology for the Aurignacian assemblages (Wood et al. Reference Wood, Arrizabalaga, Camps, Fallon, Iriarte-Chiapusso, Jones, Maroto, Rasilla, Santamaría and Soler2014), however exclusively in the western sector. This paper presents 16 additional radiocarbon dates for the western and central sectors that, together with the previous dates, provide the data for building thorough Bayesian models of the chronological sequence of the formation of the whole archaeostratigraphic sequence in each sector. The complete set of 57 radiocarbon dates obtained from the 1980s until today is analysed and evaluated.

Figure 1. Top left: location of La Viña rock shelter and other archaeological sites in central Asturias mentioned in the text. Top right. View of La Viña from the outside. Bottom left: general view of the rock shelter. Bottom right: stratigraphy and engravings from the first graphical horizon of the central sector.

Site description

La Viña rock shelter is located near Oviedo, in La Manzaneda village (UTM30 (ETRS 89) X= 270726 m; Y= 4799478 m; Z= 292 m a.s.l.) in the autonomous region of Asturias, dominating the south bank of the Rio Nalón valley. It is in a limestone massif developed during the Visean and Namurian geological periods, 500 m from and 100 m above the Nalón river. Its S-SE orientation together with its large dimensions (30 m in length and a surface area of approximately 225 m2), made it an extraordinary place to live during the Middle and Upper Palaeolithic (Santamaría et al. Reference Santamaría, Duarte, González-Pumariega, Martínez, Suárez, Fernández de la Vega, Santos, Higham, Wood, Rasilla, Salas, Carbonell, Bermúdez de Castro and Arsuaga2014). Along the same valley, there are several caves and rock shelters with, in some cases, long, well-preserved deposits from the Middle and Upper Palaeolithic (some including rock art) have been found, such as the caves of El Conde, Las Caldas, La Paloma, La Lluera and Peña de Candamo (Corchón Reference Corchón2017; Corchón et al. Reference Corchón, Garate and Rivero2017; Fortea Pérez, Reference Fortea Pérez2000–2001; Hoyos et al. Reference Hoyos, Martínez-Navarrete, Chapa, Castaños and Sanchiz1980; Rodríguez Asensio et al. Reference Fernández de la Vega and Rasilla2012).

After being discovered in 1978, two different areas of excavation were established: the western and central sectors. The western sector yielded a continuous sequence of more than 4 m from the Mousterian to the Magdalenian, which was excavated between 1980 and 1996 (Fortea Pérez, Reference Fortea Pérez1990, Reference Fortea Pérez1992, Reference Fortea Pérez1995, Reference Fortea Pérez1999, Reference Fortea Pérez and Noiret2001). Both sectors were selected for excavation, as they were contiguos to parietal engravings on the back wall of the rock shelter where two thick calcareous masses preserved archaeological remains after level IV, which formed the current rock shelter floor. The excavations yielded a remarkable archaeological deposit which included abundant lithic and bone industries, faunal and charcoal remains, ornaments, and portable art. Apart from the major archaeological sequence, the excavations revealed an important set of wall engravings clustered consisting of both non-figurative lines and animal representations. Based on the graphical repertoire and topographical work, two different graphical horizons were identified: the first horizon pertaining to the Evolved Aurignacian and the second to the Solutrean (González-Pumariega et al. Reference González-Pumariega, Rasilla, Santamaría, Duarte and Santos2017a, Reference González-Pumariega, Rasilla, Santamaría, Duarte and Santos2017b).

In the floor plan of the rock shelter, the western sector encompasses an area of around 13m2 between the F-J and lines 22 and 27 rows (Figure 2). Levels III and IV were excavated in extension down to the top of level V in squares H/J-22-26. From level V to bedrock, the excavation was focused on squares F/G-25-27 that correspond to an area of ∼6 m2. In this sector, a modern trench had been dug up to guano to fertilize nearby fields, and a connected pit was dug by clandestine looters, both of which destroyed some of the archaeological materials. Fortea removed the mixed materials before focusing on squares F/G-25-27. In this western sector, the stratigraphy reveals the maximum stratigraphic of the shelter deposit: Level I (without cultural assignment), Level II (Upper Magdalenian), Level III (Middle Magdalenian), Level IV (Middle Magdalenian), Level V (Upper Solutrean), Level VI (Middle Solutrean), Level VII (Late Gravettian), Levels VIII, IX and X (Gravettian with Noailles burins), Level XI (Late Aurignacian), Level XII (Evolved Aurignacian), Level XIII (Early Aurignacian), Level XIII inf (Proto-Aurignacian), Levels XIII basal, XIV, XV/IA and IB (Mousterian) and Level RA (altered bedrock).

Figure 2. A: Spatial view of La Viña rock shelter showing both excavation sectors: central sector (S.C.) in the centre of the rock shelter and the western sector (S.O.). B: Archaeostratigraphic sequence of the central sector C: Archaeostratigraphic sequence of the western sector.

The central sector encompasses an area of ∼26m2 between the B-H/10-14 squares. In this sector, level III was only found in a minuscule section, which is still preserved attached to the wall, named “Testigo 4”. Level IV was the first level that could be excavated in extension down to the top of level V (Figure 2). From level V to X, the excavation was focused on an area of almost 6 m2, exclusively located in the B/G-14 squares until the bedrock. The stratigraphy is well-preserved, although Fortea noted a partially disturbed zone in levels IV and V due to a trench dug for modern agricultural purposes together with some disturbances in the area that is not currently covered by the current rock shelter overhang, affecting the B and some of the C squares (Figure 2). The stratigraphy contains a continuous Upper Palaeolithic sequence: Level I (without cultural assignment), Level II (Upper Magdalenian), Levels III and IV (Middle Magdalenian), Level V (Upper Solutrean), Level VI (subdivided in VIa—Middle Solutrean; VIb—Gravettian with Gravette points and microgravettes; VIc and VIc inf—Gravettian with Noailles burins), Level VII (rockfall from collapse of the overhang, sterile), Level VIII (Aurignacian), Level IX (Early Aurignacian), Level X (undetermined initial Upper Palaeolithic) and Level XI (limestone bedrock) (Duarte and Rasilla Reference Duarte, Rasilla, Straus and Langlais2020; Fortea Pérez, Reference Fortea Pérez1995; Martínez Reference Martínez2015; Martínez and Rasilla Reference Martínez, Rasilla Vives, Heras Martin, Lasheras Corruchaga, Arrizabalaga Valbuena and Rasilla Vives2012; Santamaría Reference Santamaría2012).

La Viña, despite being one of the main sites for the Cantabrian Palaeolithic, was relatively little published due to Fortea’s untimely death. The ongoing multidisciplinary research (Rasilla et al. Reference Rasilla, Duarte, Cañaveras, Santos, Carrión, Tormo, Sánchez-Moral, Marín-Arroyo, Jones and Agudo2018, Reference Rasilla, Duarte, Cañaveras, Sanchis, Marín-Arroyo, Carrión, Real, Tormo, Sánchez-Moral and Gutiérrez-Zugasti2020, Reference Rasilla, Duarte, Cañaveras, Santos, Carrión, Sánchez-Moral, Marín-Arroyo, Torres-Iglesias, Gutiérrez-Zugasti, López-Tascón and González-Pumariega2022), along with the studies published in the last few years (Arenas-Sorriqueta et al. Reference Arenas-Sorriqueta, Marín-Arroyo, Terlato, Torres-Iglesias, Agudo Pérez and Rasilla2023; Duarte and Rasilla Reference Duarte, Rasilla, Straus and Langlais2020; Duarte et al. Reference Duarte, Utrilla Miranda, Mazo Pérez and Rasilla Vives2012; Fernández de la Vega and Rasilla Reference Fernández de la Vega and Rasilla2012; González-Pumariega et al. Reference González-Pumariega, Rasilla, Santamaría, Duarte and Santos2017a, Reference González-Pumariega, Rasilla, Santamaría, Duarte and Santos2017b; López-Tascón et al. Reference López-Tascón, Pedergnana, Ollé, Rasilla and Mazo2020; Marín-Arroyo et al. Reference Marín-Arroyo, Rios-Garaizar, Straus, Jones, de la Rasilla and González Morales2018; Santamaría et al. Reference Santamaría, Duarte, González-Pumariega, Martínez, Suárez, Fernández de la Vega, Santos, Higham, Wood, Rasilla, Salas, Carbonell, Bermúdez de Castro and Arsuaga2014; Suárez Ferruelo Reference Suárez Ferruelo2013; Torres-Iglesias et al. Reference Torres-Iglesias, Marín-Arroyo and Rasilla2022, Reference Torres-Iglesias, Marín-Arroyo, Welker and Rasilla2024; Wood et al. Reference Wood, Arrizabalaga, Camps, Fallon, Iriarte-Chiapusso, Jones, Maroto, Rasilla, Santamaría and Soler2014), including five PhD dissertations (López-Tascón Reference López-Tascón2022; Martínez Reference Martínez2015; Santamaría Reference Santamaría2012; Sanz-Royo Reference Sanz-Royo2023; Torres-Iglesias Reference Torres-Iglesias2023) has revealed key evidence about the site formation processes, the chronology of the human occupation, as well as other aspects important for the reconstruction of the life of hunter-gatherers who frequented the site such as the lithic raw materials, technology, shell ornaments along with indicators of human subsistence strategies and paleoenvironmental reconstructions. Figure 2 shows the stratigraphic sequence of both sectors and their spatial location within the rock shelter.

Material and methods

Sample selection and radiocarbon dating

As part of a broader project to reconstruct the human subsistence and the local and regional environmental and climatic conditions that late Neanderthals and Homo sapiens faced in the Cantabrian region during Marine Isotopic Stages 3 and 2 (MIS3-MIS2), using archaeozoology and taphonomy together with stable isotope analyses (δ13C, δ15N and δ34S) on animal remains consumed by humans, we conducted a complete review of the chronological data from thirteen regional sites (Marín-Arroyo et al. Reference Marín-Arroyo, Rios-Garaizar, Straus, Jones, de la Rasilla and González Morales2018). La Viña was one of the sites included in this project by selecting the undated Gravettian levels X, VIII and VII, Solutrean VI and V and Magdalenian IV and III from the western sector. In parallel, Torres-Iglesias initiated her PhD research dealing with the Magdalenian and Solutrean subsistence by analysing the archaeofaunal assemblages from western and central sectors, while Sanz-Royo analysed fauna from the lower levels of the central sector. This led to the necessity of dating both sectors to understand the site’s formation through time and possible stratigraphic correlations between sectors, identify any taphonomic process that occurred through time and might otherwise remain invisible, and confirm how the alteration that some postdepositional processes such as modern agricultural activities and clandestine looting had affected the deposit and accurately date the various periods of human occupation of the site.

From the central sector, 13 bone samples from eleven different levels were selected belonging to the Middle Magdalenian (level IV), Upper (level V/Va) and Middle Solutrean (level VIa), Gravettian (level VIb and VIc), Aurignacian (level VIII), Early Aurignacian (level IX and IXinf) and Upper Palaeolithic (level X). From the western sector, 5 bone samples from 4 levels were selected: the Upper (level III) and Middle (level IV) Magdalenian, Upper (level V) and Middle Solutrean (level VI). Selected bones had evidence of human manipulation, such as cut marks, fresh bone breakages or percussion impact marks, to directly relate the dated objects with human activity in each level (Table 1). Bones were selected from squares and spits undisturbed by modern alterations identified during excavation and posterior technological studies.

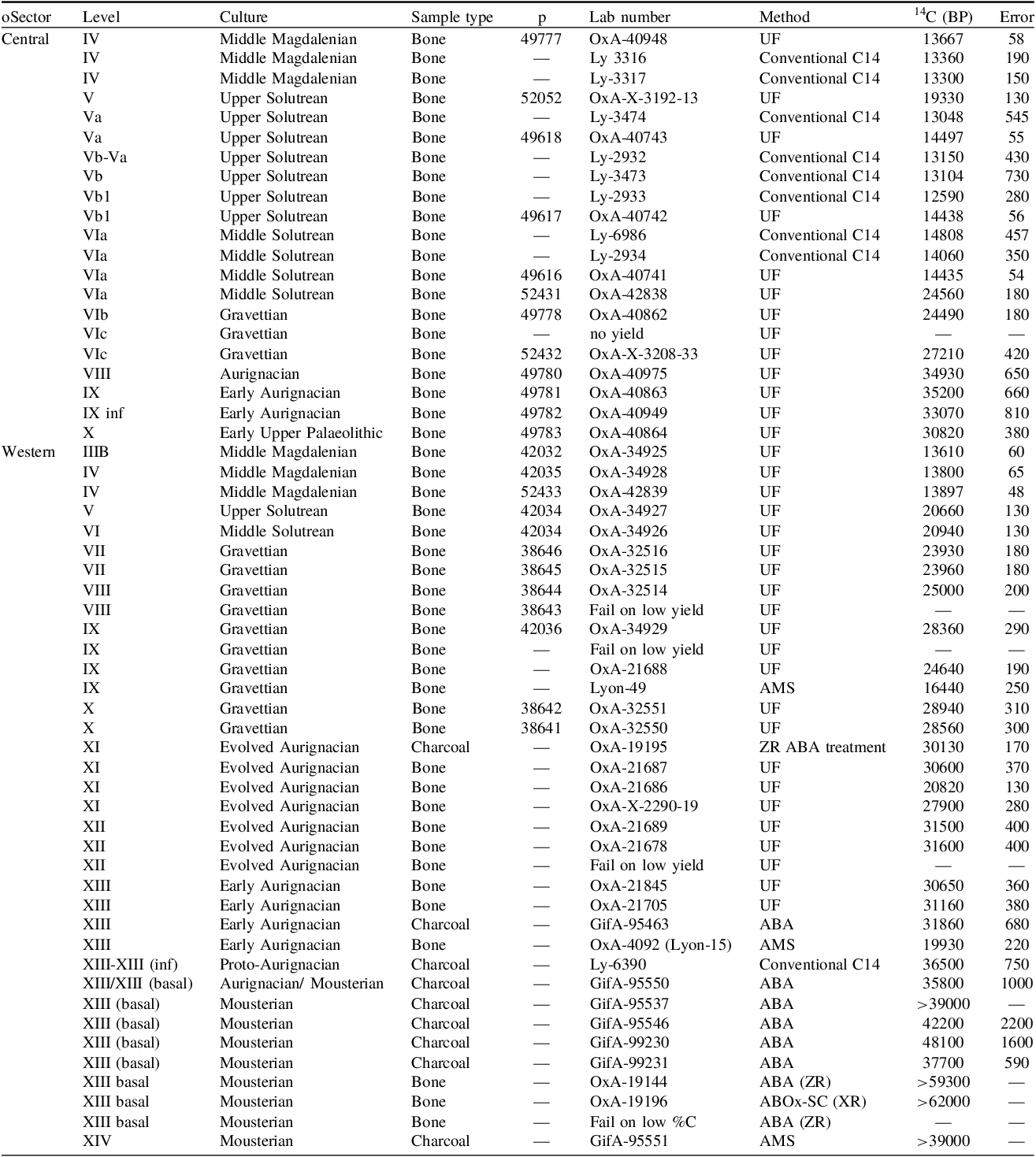

Table 1. Radiocarbon dates from La Viña rock shelter. The ZR protocol is an acid-base acid (ABA) pretreatment, the XR protocol is an ABOx-SC pretreatment and the UF protocol is an ultrafiltration method. Complete information for each sample, with details of their taxonomy and taphonomy, yield, %C, ẟ13C V-PDB (‰), ẟ15N AIR (‰), C/N atomic ratios and publication references is shown in SI Table 1.

Previous radiocarbon dates had been obtained at the site by Fortea (Reference Fortea Pérez1990, 1996, Reference Fortea Pérez1999, Reference Fortea Pérez and Noiret2001) and published years later by Soto-Barreiro (Reference Soto Barreiro2003) and Santamaría et al. (Reference Santamaría, Duarte, González-Pumariega, Martínez, Suárez, Fernández de la Vega, Santos, Higham, Wood, Rasilla, Salas, Carbonell, Bermúdez de Castro and Arsuaga2014). Recently, Wood et al. (Reference Wood, Arrizabalaga, Camps, Fallon, Iriarte-Chiapusso, Jones, Maroto, Rasilla, Santamaría and Soler2014), Marín-Arroyo et al. (Reference Marín-Arroyo, Rios-Garaizar, Straus, Jones, de la Rasilla and González Morales2018) and Torres-Iglesias et al. (Reference Torres-Iglesias, Marín-Arroyo and Rasilla2022) presented new dates that completed the set of radiocarbon dates of the site. The initial dates that Fortea obtained on animal bones and charcoal remains, were done when conventional and AMS pretreatment protocols were used (i.e., before the development of ultrafiltration methods). Over the years, samples were pretreated and dated at Centre de Datation et d’Analyses Isotopiques at the Université de Lyon and at the Gif sur Yvette (GIF) Tenadetron AMS Facility. Since 2014, dates have been undertaken at the Oxford Radiocarbon Accelerator Unit (ORAU), with respective lab-code prefixes “Ly”, “GifA”, and “OxA”.

Eight charcoal samples were pretreated with the Acid–Base–Acid (ABA) pretreatment protocol, which used 1M HCl and 0.1M NaOH at GifA laboratory and 5% HCl (≈1.4M HCl) and “diluted” NaOH at CAIS. Seven were measured at GifA and one at Lyon. These samples were treated before ABOx-SC procedures (Bird et al. Reference Bird, Ayliffe, Fifield, Turney and Cresswell1999). Only one charcoal sample from level XI from the western sector was treated with the latter pretreatment method (Wood et al. Reference Wood, Arrizabalaga, Camps, Fallon, Iriarte-Chiapusso, Jones, Maroto, Rasilla, Santamaría and Soler2014).

All new dates presented in this paper were animal bones pretreated and dated at the ORAU, following archaeozoological study. Ultrafiltration has been revealed as an effective method of removal of low-molecular-weight contaminants from bone collagen (Brock et al. Reference Brock, Higham and Ramsey2010; Bronk Ramsey et al. Reference Bronk Ramsey, Higham, Bowles and Hedges2004), especially for samples near the radiocarbon limit. Routine protocol involved collagen obtained following the method detailed by Brock et al. (Reference Brock, Higham and Ramsey2010), which involves the demineralisation of the mineral component (and any exogenous carbonates) of drilled bone power using 0.5M HCL at 5°C overnight, before removal of organics and humic acid using 0.1M NaOH solution for 30 minutes at room temperate (RT), and a final wash in 0.5M HCL for 1 hour at RT. The collagen was gelatinised in a 0.001M HCL solution for 20 hours at 70°C. EZEE™biological filters (45–90 μm) were used to remove smaller soluble components, before ultrafiltration using cleaned 30 kDa MWCO Vivaspin™ 15 ultrafilters. Combustion of the collagen using an elemental analyser (ANCA-GSL), linked to an isotope ratio-mass spectrometer (Sercon 20–20), produced carbon and nitrogen stable isotope data, and samples were dated using an Accelerator Mass Spectrometer following conversion of excess CO2 into graphite using an iron catalyst (Bronk Ramsey et al. Reference Bronk Ramsey, Higham, Bowles and Hedges2004). The following quality assurance criteria applied for bone collagen quality indicators were used: % collagen (>1), %C (30–44%), %N (11–16%), C/N atomic ratios (2.9–3.6) (Van Klinken Reference Van Klinken1999; Brock et al. Reference Brock, Bronk Ramsey and Higham2007).

Calibration and Bayesian analysis

Bayesian methods provide a robust analytical framework to process radiocarbon data. The Bayesian model enables to modify the calibrated Probability Distribution Function (PDF) of individual dates based on the existing relative stratigraphic and other relative age information. Since the early to mid-2000s, Bayesian methods have been applied widely to radiocarbon dating (Bronk Ramsey Reference Bronk Ramsey2000; Reference Bronk Ramsey2008, Reference Bronk Ramsey2009; Bronk Ramsey et al. Reference Bronk Ramsey, Dee, Lee, Nakagawa and Staff2010), especially to unravel the duration of the formation of archaeological levels in-site and to understand regional technocultures and biological processes such as the replacement of Neanderthals by anatomically modern humans in northern Iberia (Marín-Arroyo et al. Reference Marín-Arroyo, Rios-Garaizar, Straus, Jones, de la Rasilla and González Morales2018; Rios-Garaizar et al. Reference Rios-Garaizar, Iriarte, Arnold, Sánchez-Romero, Marín-Arroyo, San Emeterio, Gómez-Olivencia, Pérez-Garrido, Demuro and Campaña2022; Vidal-Cordasco et al. Reference Vidal-Cordasco, Ocio, Hickler and Marín-Arroyo2022) and in Europe (Vidal-Cordasco et al. Reference Vidal-Cordasco, Terlato, Ocio and Marín-Arroyo2023).

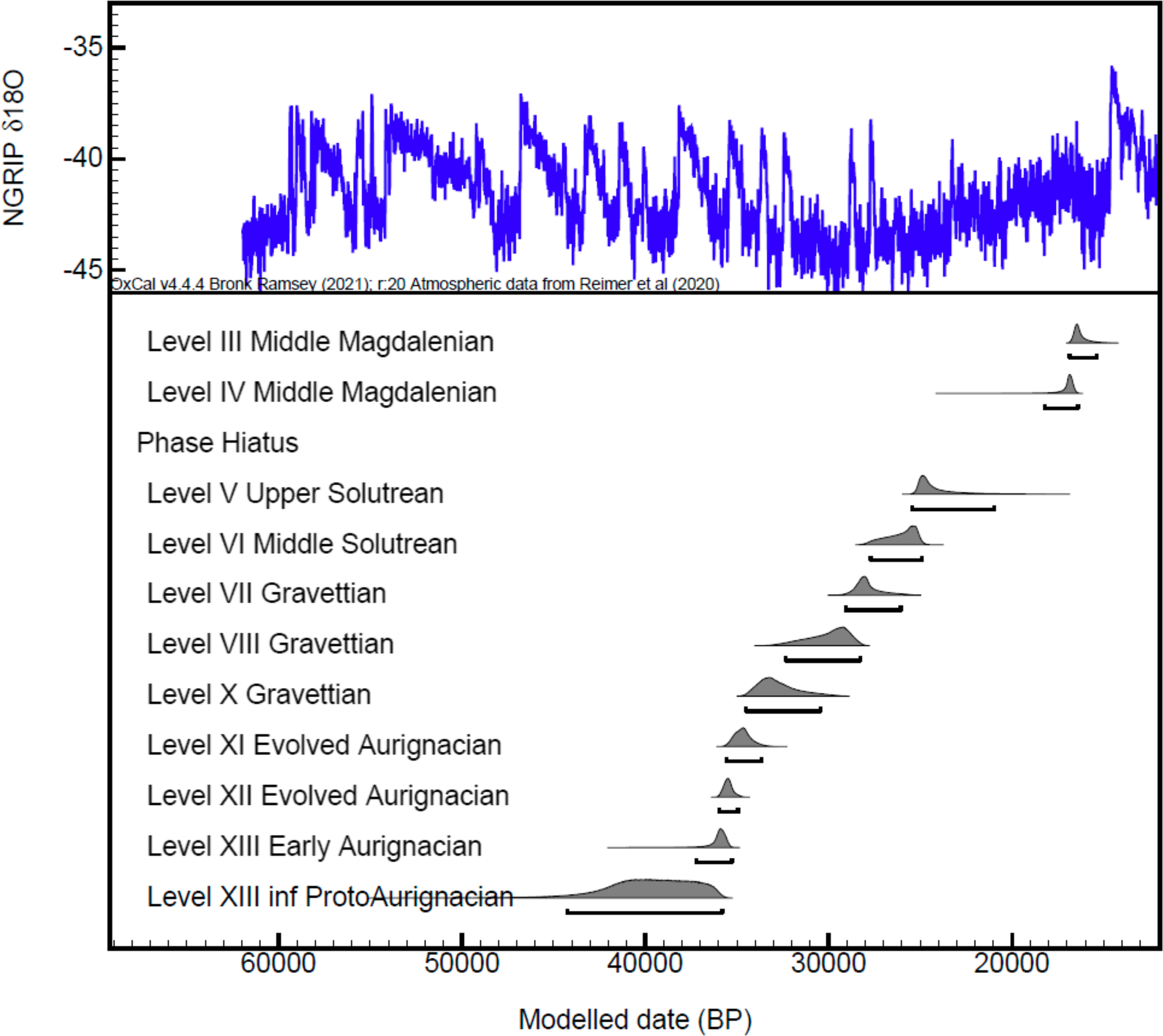

Two Individual Bayesian age models were built for the La Viña western and central sectors using OxCal4.4 software (Bronk Ramsey Reference Bronk Ramsey2009) and the INTCAL20 calibration curve (Reimer et al. Reference Duarte, Rasilla, Straus and Langlais2020). At La Viña, the Bayesian model enables the modification of the calibrated Probability Distribution Function (PDF) of individual dates based on the existing relative stratigraphic. Thus, the dates were modeled in a Sequence model with stratigraphic levels represented as Phases, with start and end Boundaries. These boundaries provide an estimate for when each phase started and finished. The difference between the probability distribution functions of the start and end boundaries was also calculated to estimate the likely duration of the phase. Dates with adequate quality criteria have been included without methodological discrimination. In both sectors, a hiatus between levels V and IV in the western sector, corresponding with the Upper Solutrean and the Middle Magdalenian, and in the central sector between levels VIII and VIc (corresponding with sterile level VII) have been included. All radiocarbon determinations were given a 5 per cent prior likelihood of being an outlier within the General t-type Outlier Model (Bronk Ramsey Reference Bronk Ramsey2009b) so that the model could test their reliability. This outlier probability is then modeled, and if a specific radiocarbon date is outlying, its influence on the model is down-weighted. A resolution of 20 years was assumed, being a reasonable balance between required accuracy and computational costs. The results were compared with tdata obtained from the NGRIP ice-core (North Greenland Ice Core Project members 2004; Svensson et al. Reference Svensson, Nielsen, Kipfstuhl, Johnsen, Steffensen, Bigler, Ruth and Röthlisberger2005). New radiocarbon dates and previous ones were considered for completeness (Table 1). CQL code and modeling results are given in (SI Code).

Results

We present and discuss the results of the total available radiocarbon dates per sector and level at La Viña. Table 1 summarizes information about sample dates (including failed ones) with spatial location and SI Table 1 includes taxonomy, anatomy, taphonomy and chemical results, when available.

Until 2014, the chronology at the site was based on ten radiocarbon dates from the western sector and eight from the central one. Today, the complete La Viña radiocarbon data-set contained 57 dates, 21 from the central sector and 36 from the western one. Of those 48 were done on bone collagen and 9 on charcoal. Five samples failed due to low collagen yield, all from the western sector. Of 38 measurements, we have %yield data, of which 35 include ẟ13C V-PDB (‰) and ẟ15NAIR (‰) values and C/N atomic ratios. Samples treated contained between 0.4 and 4.9 collagen yield percentages, with five samples showing values between 0.4 and 0.8. Despite the low yield percentage, %C values of those five samples range between 35 and 44% but were excluded based on poor dating quality. In general, C/N atomic ratios were between 3.2 and 3.4. Following, we present the results of dates by sector and archaeological level.

Discussion

Western sector

During the excavations of the site, Fortea (1996, Reference Fortea Pérez1999, Reference Fortea Pérez and Noiret2001) undertook eight dates on charcoal (level XIII, XIII inferior, XIII basal and XIV) and one in bone (level XIII). Six dates were measured at the Lyon and two at the GifA laboratories in France, aiming to establish the chronology of the lower sequence from levels XV to XII. Dates done on charcoal for Fortea in the Mousterian levels XIV and XIII basal were uneven. Specifically, from level XIII basal GifA-95546 (42,200 ± 2200) was done on the humic contaminant fraction of a charcoal sample (GifA-95537— >39,000) and therefore, this date only could be used to assess the age of possible contaminants. The remaining six charcoal samples from Mousterian levels XIV and XIII basal, also pretreated with ABA protocol, suggested that the lower level was beyond the radiocarbon limit and the XIII basal was older than 42 ka cal BP (48,100 ± 1600—GifA-99230; 37,700 ± 590—GifA-99231; 35,800 ± 1000—GifA-95550). Whereas, at that time, the Proto-Aurignacian level XIII (inferior) date was significant for the start of the Iberian Protoaurignacian (36,500 ± 750 Ly-6390). The charcoal date of Early Aurignacian level XIII was in stratigraphic order and placed this unit at 31,860 ± 680 (GifA-95463). However, the two bone dates from early Aurignacian level XIII (OxA-4092/Ly-15) and Gravettian level IX (Ly-49) were considered too young (19,930 ± 220 and 16,440 ± 250), respectively.

Thus, years later Wood et al. (Reference Wood, Arrizabalaga, Camps, Fallon, Iriarte-Chiapusso, Jones, Maroto, Rasilla, Santamaría and Soler2014) focused on unravelling the chronology of the Middle to Upper Paleolithic transition by redating the Mousterian (XIII basal) with three new dates, nine dates from the Early and Evolved Aurignacian levels (XIII, XII, XI) and two more from the Gravettian level IX. The ultrafiltration methods applied were useful for removing many possible contaminants. Hence, their results confirmed that level XIII basal was beyond the limit of the radiocarbon method, suggesting that the previous ABA protocol was insufficient to remove contaminants from charcoal. The low collagen yield in the selected bones prevented Mousterian level XIII basal dating. For the Evolved Aurignacian level XI, dates were uneven due to a collagen yield lower than 1%, despite the C/N ratio being acceptable. Wood et al. (Reference Wood, Arrizabalaga, Camps, Fallon, Iriarte-Chiapusso, Jones, Maroto, Rasilla, Santamaría and Soler2014) noted that despite bone (30,600 ± 370—OxA-21687) and charcoal (30,130 ± 170—OxA-19195) samples being similar in age, possible contaminants were not entirely removed from the small samples as two bone samples provided a younger date of 27,900 ± 280 (OxA-X-2290-19) and 20,820 ± 130 (OxA-21686). The latter was from a bone exposed in the stratigraphic profile, and Fortea pointed out that it could come from profile fall between seasons (Wood et al. Reference Wood, Arrizabalaga, Camps, Fallon, Iriarte-Chiapusso, Jones, Maroto, Rasilla, Santamaría and Soler2014, 103).

Nonetheless, Wood et al. (Reference Wood, Arrizabalaga, Camps, Fallon, Iriarte-Chiapusso, Jones, Maroto, Rasilla, Santamaría and Soler2014) provided a chronological consistency for the formation of the Early Aurignacian level XIII. However, they noted that the dates from level XIII are similar to those from the immediately overlying Evolved Aurignacian level XII. This could be explained by the fact that the samples were selected from the upper part of Level XIII and could not be discarded—possible interlevel mixtures with the base of Level XII (Wood et al. Reference Wood, Arrizabalaga, Camps, Fallon, Iriarte-Chiapusso, Jones, Maroto, Rasilla, Santamaría and Soler2014, 23). On the other hand, the conventional Lyon-15 date (19,930±220) is considered a far overly young outlier.

In 2018, by continuing Wood’s methodology and aiming to obtain a continuous dating of the western stratigraphic sector, Marín-Arroyo obtained twelve new dates from Gravettian (X, IX, VIII and VII), Middle (VI) and Upper (V) Solutrean ones and Middle Magdalenian (IV and III) levels. The Gravettian dates were published by Marín-Arroyo et al. (Reference Marín-Arroyo, Rios-Garaizar, Straus, Jones, de la Rasilla and González Morales2018). Four Gravettian levels exist (X, IX, VIII and VII) in the western sector. Seven dates were attempted for these levels; only one failed from level IX due to low collagen yield (Table 1). Level X, which remained undated, provided two dates of 28,940±310 (OxA-32551) and 28,560±300 (OxA-32550) (Marín-Arroyo et al. Reference Marín-Arroyo, Rios-Garaizar, Straus, Jones, de la Rasilla and González Morales2018). Level IX offered a previous date of 24,640±190 (OxA-21688) by Wood et al. (Reference Wood, Arrizabalaga, Camps, Fallon, Iriarte-Chiapusso, Jones, Maroto, Rasilla, Santamaría and Soler2014) and a new one of 28,360±290 (OxA-34929) by Marín-Arroyo et al. (Reference Marín-Arroyo, Rios-Garaizar, Straus, Jones, de la Rasilla and González Morales2018). OxA-34929 is more coherent with dates obtained from Level X. Thus, it might reveal some degree of unclear definition between Level IX and X during excavation. This could have been caused by Level X’s limited extension and 10–15 cm thickness, dipping towards the east in the excavated area where the OxA-34929 sample was taken in those squares, very close to the intersection between both levels. Given the inconsistencies mentioned above, Level IX remains undated despite inclusion of OxA-21688 in the Bayesian model. It continues to result as an outlier, as Wood et al. (Reference Wood, Arrizabalaga, Camps, Fallon, Iriarte-Chiapusso, Jones, Maroto, Rasilla, Santamaría and Soler2014) already noted.

For Level VIII, one date failed due to a low collagen yield, while a second date was 25,000±200 (OxA-32514). Two dates of 23,960±180 (OxA-32515) and 23,930±180 (OxA-32516) were obtained for Level VII.

The Solutrean and Magdalenian levels lacked any radiocarbon dates before Marín-Arroyo’s study. Dating results for the Middle Solutrean Level VI provided a date of 20,940±130 (OxA-34926) and for the Upper Solutrean Level V 20,660±130 (OxA-34927) (Torres-Iglesias et al. Reference Torres-Iglesias, Marín-Arroyo and Rasilla2022). Level IV, attributed to the Middle Magdalenian, provided a date of 13,800±65 (OxA-34928), and Middle Magdalenian Level III produced a date of 13,610±60 (OxA-34925). Despite OxA-34927 from Level V containing 0.7% yield, the elemental and stable isotope data did not highlight any major contaminants and were considered adequate.

Bayesian model of the western stratigraphic sequence

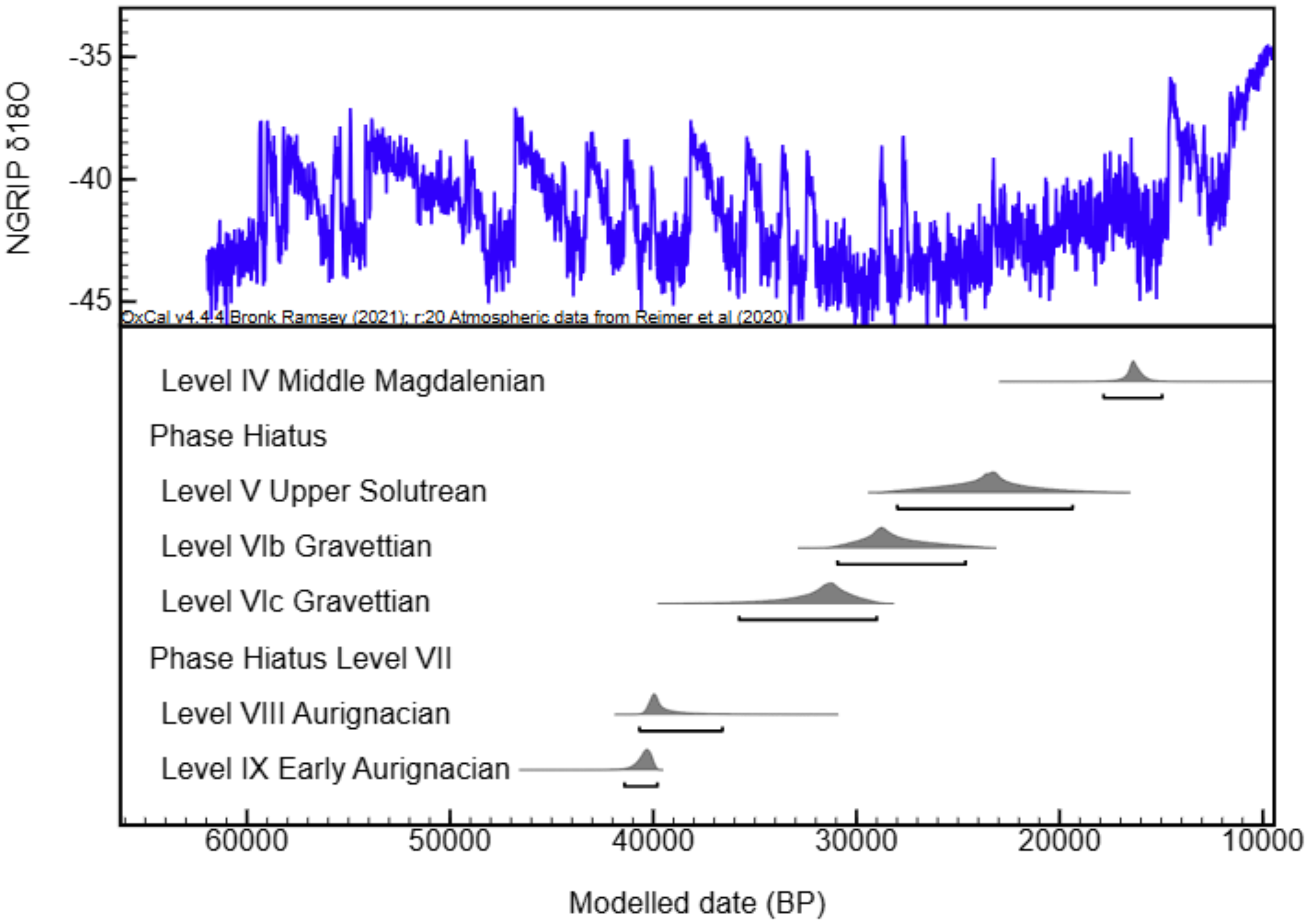

Figure 3 presents a Bayesian model for the complete stratigraphic sequence per cultural period from the Aurignacian to the Magdalenian in the western sector (Figure SI1 shows the extended Bayesian model that includes the whole set of radiocarbon dates). In this model, 18 dates were included from XIII until level III, covering the 11 cultural levels of this western sequence. As stated before, some dates were excluded from the model as they were considered unreliable or outliers. Those correspond with the conventional dates from level XIII basal (GifA-95550; GifA-95546, GifA-99230, GifA-99231), where possible humic contaminants were dated, and the younger date of level XIII (Ly-15), an intrusive sample of level XI (OxA-21686 and OxA-X-2290-19 caused by the incomplete removal of contaminants,) and level IX (Lyon 49 and OxA-21688, both considered outliers).

Figure 3. Chronostratigraphic cultural model for the western sector showing the date ranges for each level. The complete Bayesian model is shown in Figure SI.1. Modeling results are given in SI Table 2, and code is provided in SI Code.

Both during and after the deposition of the Mousterian levels in the western sector, erosion was caused by channelled, sheet-flooding and runoff water, that removed part of the levels in the west sector both in extension and in-depth down to bedrock, with human evidence remaining only in lines 26 and 27. These particular geological factors are common in the rock shelter and are increased in areas where the roof had collapsed before the accumulation of these deposits. In both sectors, the Solutrean, in a clear stratigraphic position between the Gravettian and classic Middle Magdalenian, shows how the erosion between levels V and IV partially eroded the accumulated deposits. Still, these processes might have lasted a more extended period, probably occurring until Middle Magdalenian, and might explain the absence of a Lower Magdalenian occupational deposit (Hoyos 1994), if this happened.

As indicated in Table 2, Bayesian results for the Protoaurignacian level XIII inferior indicate a duration between 44,240 and 35,790 cal BP. The Early Aurignacian level XIII is dated between 37,200 and 35,270 cal BP, and Evolved Aurignacian identified in level XII to 35,960 and 34,930 and in level XI 35,570 and 33,660 cal BP at 95,4% probability. This implies that the development of the Aurignacian culture at La Viña was between 44,240 and 33,590 cal BP, covering the period from GS12 to GS7, while the ProtoAurignacian chronologically coincided with Heinrich Event 4. There is a partial overlap of less than a millennium between the formation of Aurignacian level XI and the Gravettian level X. The three Gravettian levels were developed between 34,490 and 26,060 cal BP, covering from GS7 to mid-GS4 (level X: 34,490–30,420 cal BP; level VIII: 32,330–28,270 cal BP; level VII: 29,070–26,060 cal BP). Heinrich Event 3 coincided with the formation of level VIII.

Table 2. Age estimations at the 95.4% confidence interval for levels in the western and central sectors were calculated using the boundary models (SI: Tables 1-2, Figures 1-2) and created Figure 5.

The model includes a hiatus between level V (Upper Solutrean) and level IV (Middle Magdalenian) This is given the evidence of erosions that level V presents in its upper part (Hoyos Reference Hoyos1994, Reference Hoyos, Moure Romanillo and González Sainz1995) and the lack of a level attributed to the Lower Magdalenian, which those erosion episodes may have removed. This hiatus is dated between 20,950 and 18,360 cal BP, between the end of level V and the start of level IV, respectively. The date range of Middle Solutrean level VI is 27,710–24,890 cal BP and the Upper Solutrean level V is 25,460–20,950 cal BP. The Solutrean at La Viña covers the period from the GS4 to the early GS2. The end of the Middle Solutrean and the whole Upper Solutrean coincide with Heinrich Event 2 and the beginning of the Last Glacial Maximum. Finally, the upper sequence ends with the Magdalenian, which is a short period compared to previous cultures. The date range for Middle Magdalenian level IV is 18,210-16,390 cal BP, and the Middle Magdalenian level III is 16,850–15,360 cal BP. These two levels coincide with the end of the GS2 (Table 2 and Figure 3).

Central sector

Fortea (Reference Fortea Pérez1990) published two dates of Magdalenian level IV from this sector. Years later, six dates from Middle (VIa) and Upper (V/Va and Vb) Solutrean levels, rejected and unpublished by Fortea, were included in a publication by Soto Barreiro (Reference Soto Barreiro2003) that compiled the available radiocarbon dates in the region without a proper stratigraphic, taphonomic and cultural study of the sequence. Conventional radiocarbon methods at the Lyon laboratory achieved these samples on mammal bones. After getting the dating results, Fortea raised the possibility of postdepositional events (Fortea, personal archive field notes; Soto Barreiro 2023, 98) that, later on, geological studies confirmed (Rasilla et al. Reference Rasilla, Duarte, Cañaveras, Sanchis, Marín-Arroyo, Carrión, Real, Tormo, Sánchez-Moral and Gutiérrez-Zugasti2020).

New samples were selected for dating during recent archaeozoological work on bones from this sector, aiming to establish the chronology of the whole sequence from levels X to IV, from the Upper Paleolithic to the Middle Magdalenian. In addition to the eight available dates by Fortea, 13 dates were obtained using ultrafiltration techniques on selected mammal bones with evidence of human manipulation, including cut marks and/or anthropogenic breakage.

Until this study, the chronology of the lower sequence was unknown, and the following dates had remained unpublished. According to the lithic artifact remains found, level X was attributed to the Early Upper Paleolithic. The obtained date is 30,820±380 (OxA-40864). Level IX, classified as Early Aurignacian, is dated by two assays: 35,200±660 (OxA-40863) and 33,070±810 (OxA-40949). Level VIII is defined as Aurignacian sensu lato with a date of 34,930±650 (OxA-40975). Level VII is archaeologically sterile and made up of fallen blocks corresponding to the last retreat of the shelter overhang (Fortea, Reference Fortea Pérez1990: 56) and remains undated. Gravettian level VI is subdivided between sublevels VIc, classified as Noaillian Gravettian, and dated to 27,210±420 (OxA-X-3208-33) and sublevel VIb, is classified as Gravettian without Noailles burins but with Gravette points and microgravettes and dated to 24,490±180 (OxA-40862) (Fortea Reference Fortea Pérez1992, 21). Another sample from level VIb provided no yield.

Level VIa is attributed to the Middle Solutrean based on the finds of Solutrean retouched points including “laurel leaves”. This level provided a date of 24,560±180 (OxA-42838), similar to the date obtained in the Gravettian level VIb. In both levels, the presence of temporally diagnostic tool types clearly differentiated their cultural attribution. In this study, the bones selected for dating were found in different splits of squares E14 and F14, with a difference of about 13 cm in depth between them. The sedimentological boundary between the levels was unclear (mainly marked by cryoclasticspall and gullies) and the presence of several blocks fallen from the overhang (Figure 2), which could have led to interstratigraphic artifact contamination. For this reason, OxA-42838 has not been included in the model. Another ultrafiltration date from Level VIa provided an incoherent date of 14,435±54 (OxA-40741). This inconsistency is observed in the conventional radiocarbon dates (Ly-6986 and Ly-2934) from level VIa rejected by Fortea and published by Soto-Barreiro (Reference Soto Barreiro2003), and it continues among those dates obtained in the Upper Solutrean levels Vb, Va and V. From level VIa: 14,060±350 (Ly-2934) and 14,808±457 (Ly-6986); from level Vb: 12,590±280 (Ly-2933); 13,104±730 (Ly-3473). A bone found between levels Vb and Va is dated at 13,150±430 (Ly-2932), and another from level Va to 13,048±545 (Ly-3474). We tried to solve this discrepancy in the Solutrean levels with the new dates. However, attempts were relatively unfruitful. Ultrafiltered dates obtained in Vb provided a date of 14,438±56 (OxA-40742), and from Va, 14,497±55 (OxA-40743). These new dates maintained the inconsistency in those Solutrean levels by obtaining similar dates around 14-13k uncal BP corresponding to the regional Magdalenian culture. Fortea (Fortea and Hoyos personal archives field notes; Hoyos Reference Hoyos, Moure Romanillo and González Sainz1995; Soto-Barreiro Reference Soto Barreiro2003, 98) pointed out that these much younger dates were due to intensive postdepositional processes of running water in this area. To minimise the problems observed by Fortea, samples from this study were selected from the outermost area of the shelter and, therefore, far from a hearth that primarily affected F/G-14 squares. However, as these had no collagen yield, another set of samples was chosen from other squares. Some of the samples come from or were close to the hearth made by the Magdalenian groups during level IV and, due to the successive human reuse and cleaning activities in this hearth, these actions had affected level V (and its internal subdivisions) and the upper part of level VIa, so removals of material within those levels might have existed. Information deduced from this situation and the dates obtained around 14–13,000 uncal BP in these Solutrean point-bearing levels, but that are temporally related by the 14C dates to the regional Magdalenian, raises a problem that is being addressed in Duarte’s ongoing doctoral thesis.

To this end, only OxA-X-3192-13 provided a reliable date from level V of 19,330±130 that, despite a 0.8% collagen yield, had an acceptable C/N atomic ratio of 3.2. Finally, Middle Magdalenian level IV had previous two conventional radiocarbon dates of 13,360±190 (Ly-3316) and 13,300±150 (Ly-3317). An ultrafiltered date converged with the available dates, resulting in 13,367±58 BP (OxA-40948).

Bayesian model of the central stratigraphic sequence

Figure 4 presents the Bayesian model for the complete stratigraphic sequence in the central sector, covering the Aurignacian, Gravettian, Solutrean and Magdalenian (Figure SI2 shows the extended Bayesian model that shows the whole radiocarbon date-set). In this model, 9 dates were included from X until level IV, covering the six different human occupations. As stated before, eleven dates were excluded from the model as they were considered outliers or unreliable. Those mostly correspond with the conventional dates from middle and upper Solutrean levels (Level VIa: Ly-6986, Ly-2934 and OxA-40741; level Vb: Ly-3473, Ly-2933, OxA-40742; level Vb-Va: Ly-2932; Level Va: Ly-3474 and OxA-40743). From level X, OxA-40864 was considered an outlier by the Bayesian model.

Figure 4. Chronostratigraphic cultural model for the central sector. The complete Bayesian model is shown in Figure SI.2. Modeling results are given in SI Table 3, and code is provided in SI Code.

As stated in Table 2, Bayesian results for the Early Aurignacian level IX indicate a temporal duration between 41,410 and 39,790 cal BP (Table 2), while the Aurignacian level VIII is dated between 40,680 and 36,590 cal BP at 95,4% probability. Aurignacian groups faced both temperate and cold climatic conditions from GI10 to early GS8, overlapping with Heinrich Event 4 during the occupation of level VIII. A gap of 820 years, included as a hiatus in the model, between the Aurignacian VIII and the Gravettian level VIc could be related to the presence of archaeological sterile level VII, falling between the two cultures in this sector. Besides, in the model, the availability of just a date for each Gravettian level modeled long-duration phases for each of them. Gravettian in this sector is found between 35,770 and 24,630 cal BP covering from end GS7 to mid-GS4 (Noaillian Gravettian level VIc: 35,770 and 29,000 cal BP; Gravettian with Gravette points and microgravettes level VIb: 30,930–24,630 cal BP), partially overlapping the end of level VIb with the start of Solutrean level V after Heinrich Event 3 took place.

Due to inconsistencies in the dates, the model did not include Solutrean levels VIa, Vb and Va. Thus, level V is the only Solutrean level modeled in this sector corresponds to the Upper Solutrean. Its date range to the 27,990-19,350 cal BP. The dated Solutrean at La Viña starts during GI3 until the end of the Last Glacial Maximum. Heinrich Event 2 chronologically coincided with the formation of this Upper Solutrean level. As we did in the western sector, a hiatus has been included between level V and level IV to avoid oversizing the ranges modeled for both levels, given the erosions that Upper Solutrean levels present in its upper part in both sectors (Hoyos Reference Fortea Pérez1995) that likely eroded any possible Initial Magdalenian occupations. In the central sector, the upper sequence ends with this Middle Magdalenian level IV, which overlaps with the Heinrich Event 1. Its date range is 17,830-14,950 cal BP.

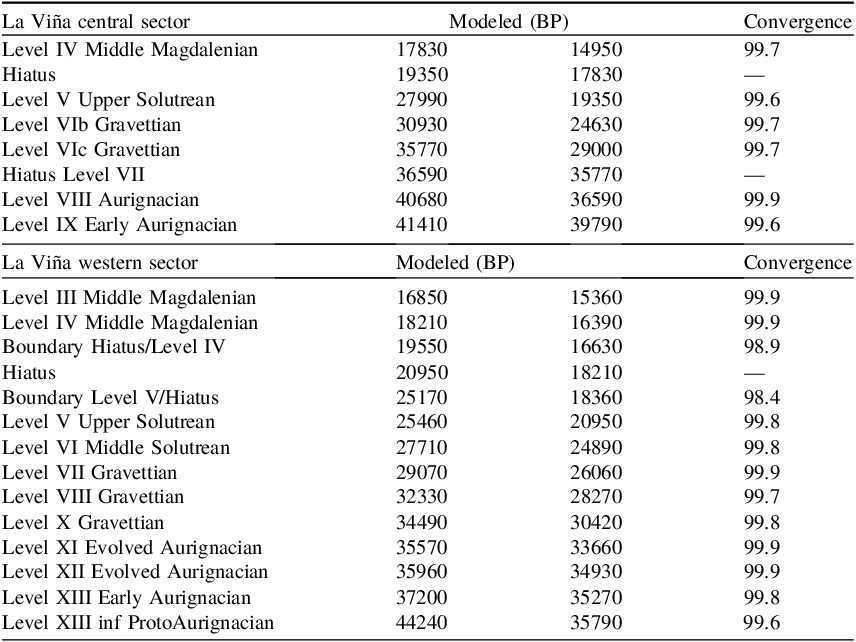

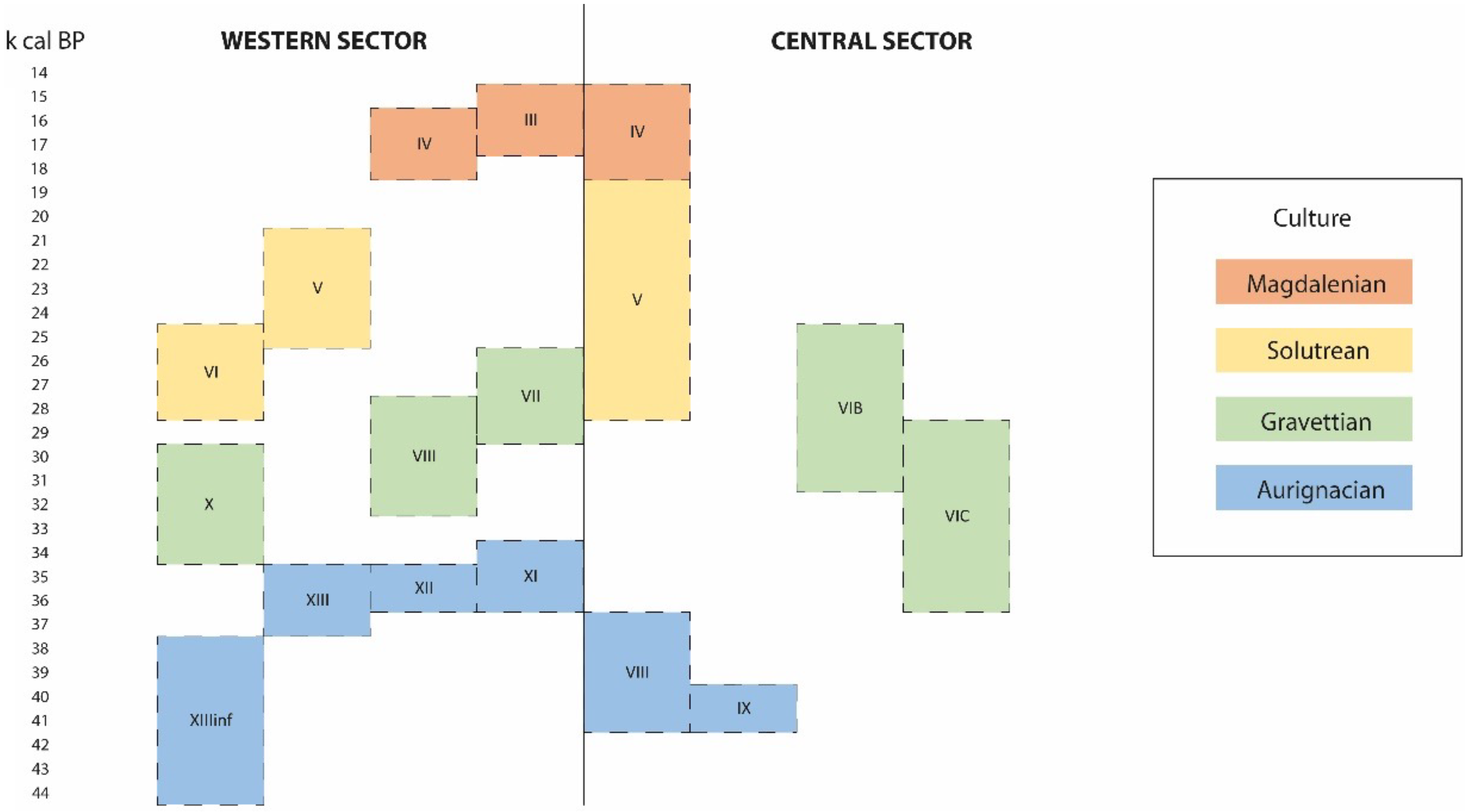

Inter-sector comparison

Based on the Bayesian results, we establish a chronostratigraphic correlation between the levels in both sectors (Figure 5). However, this does not necessarily imply the existence of a geological correlation between the stratigraphy or cultural elements found in both sectors. This visual correlation shown in Figure 5 helps to understand the possible use of the cave during the different cultural phases when hunter-gatherers occupied the rock shelter. In the central sector, the imprecision on the duration of the Gravettian and Solutrean periods could likely be motivated by the fewer samples in this sector compared to the western sector.

Figure 5. Date ranges modeled for archaeological levels found in western and central sectors (for 44,000–14,000 cal BP), with tentative cultural associations between both sectors.

Cultural regional comparison for the Cantabrian Region

Methodological developments in radiocarbon dating and the publication of recent radiometric dates from the late Middle and Upper Palaeolithic sites allow us to assess with greater precision the chronology of the different Late Pleistocene archaeological cultures defined in the Cantabrian region (Marín-Arroyo et al. Reference Marín-Arroyo, Rios-Garaizar, Straus, Jones, de la Rasilla and González Morales2018; Vidal-Cordasco et al. Reference Vidal-Cordasco, Ocio, Hickler and Marín-Arroyo2022; Wood et al. Reference Wood, Arrizabalaga, Camps, Fallon, Iriarte-Chiapusso, Jones, Maroto, Rasilla, Santamaría and Soler2014). In general, the chronostratigraphic sequence of La Viña is in line with the chronological scheme proposed for the regional technocomplexes developed during the Upper Palaeolithic.

The Protoaurignacian appears early in such sites as El Castillo 16, Isturitz and Labeko Koba VII, around ∼44-42 ka cal BP (Wood et al. Reference Wood, Arrizabalaga, Camps, Fallon, Iriarte-Chiapusso, Jones, Maroto, Rasilla, Santamaría and Soler2014; Barshay-Szmidt et al. Reference Barshay-Szmidt, Normand, Flas and Solier2018; Marín-Arroyo et al. Reference Marín-Arroyo, Rios-Garaizar, Straus, Jones, de la Rasilla and González Morales2018; Hublin Reference Hublin2015). At La Viña, this technocomplex appears around 44 ka cal BP parallel to those found in Gatzarria Cjn2, Cobrante VI and Covalejos B and C (Marín-Arroyo et al. Reference Marín-Arroyo, Rios-Garaizar, Straus, Jones, de la Rasilla and González Morales2018). Later, the Early Aurignacian appears around 41 ka cal BP and lasts until 39 ka cal BP in the central sector. It developed later in the western sector, between 37 and 35 ka cal BP. Therefore, the dates of the Early Aurignacian are different in both sectors (western sector between 44.2–33.6 ka cal BP; central sector 41.4–36.5 ka cal BP), which could suggest that to human groups occupied different parts of the site in separate episodes. The Evolved Aurignacian appeared at 36ka cal BP at La Viña in the western sector, with an overlap of 690 years with the end of the Early Aurignancian. The succession of different levels between both sectors also indicates different spatial uses of the rock shelter over time. Today, there is insufficient evidence to prove a regional rupture from the early to the evolved Aurignacian technology developed on-site. Isturitz, Aitzbitarte III, Labeko Koba contain both Early and Evolved Aurignacian and show no appreciable differences between the tecnhocultural phases and a continuity is observed in both the raw material and techno-typology (Arrizabalaga Reference Arrizabalaga, Arrizabalaga and Altuna2000; Bon, Reference Bon, Maíllo Fernández and Ortega Cobos2002; Normand, 2005-2006; Rios et al. Reference Rios-Garaizar, Peña Alonso, San Emeterio Gómez, Altuna, Mariezkurrena and Rios2011; Tafelmaier Reference Tafelmaier2017). Despite the causes of the spread of Aurignacian technologies remaining critical, the new results indicate that different, presumably modern human groups occupied La Viña rock shelter for several millennia before the arrival of the Gravettian culture.

The Gravettian occupations of the western sector of La Viña are fully integrated within the range established for the technocomplex in the region, which is dated between 37.3-24.7 ka cal BP (Marín-Arroyo et al. Reference Marín-Arroyo, Rios-Garaizar, Straus, Jones, de la Rasilla and González Morales2018; Torres-Iglesias Reference Torres-Iglesias2023). Level X (western sector) might represent an early Gravettian around 35 ka cal BP, occurring around the same time as in Llonin V (Martínez Fernández, Reference Martínez Fernández2015) and the Basque region sites of Atxurra (Aranbarri et al. Reference Aranbarri, Arriolabengoa, Rios-Garaizar, Aranburu-Mendizabal and Uzquiano2024), Amalda VI (Sánchez-Romero et al. Reference Sánchez-Romero, Benito-Calvo and Marín-Arroyo2020) and Aitzbitarte III exterior Level IV (Rios-Garaizar et al. Reference Rios-Garaizar, Peña Alonso, San Emeterio Gómez, Altuna, Mariezkurrena and Rios2011). The date from level VIII likely aligns with a middle phase of the Gravettian, coinciding with Bolinkoba Level VI/F, and the level VII dates probably represent a later phase of this archaeological culture (Marín-Arroyo et al. Reference Marín-Arroyo, Rios-Garaizar, Straus, Jones, de la Rasilla and González Morales2018). However, the Gravettian-modeled dates from the central sector indicated an earlier start to around 36 ka cal BP, which could be motivated by the low number of dates and the absence of dates in the archaeologically sterile level VII, providing longer duration phases in the model. The Gravettian occupations in the western sector are dated between 34.4–26 ka cal BP, while the central sector is dated between 35.7–24.6 ka cal BP.

The date range proposed in the model for the Solutrean of the La Viña both western and central sector is excessively broad. This is caused by including only a few dates (a single one from level V in central sector and one for level VI and V in the western sector) to model the duration of this archaeological culture, as well as the inclusion of the hiatus between the Solutrean and Magdalenian. As in this case, the Bayesian modeling tends to extend the boundaries when few radiocarbon dates are included. Thus, the Solutrean occupations in the western sector are dated between 27.7–20.9 ka cal BP, while in the central sector between 27.9–19.3 ka cal BP. Nevertheless, the Solutrean modeled dates from both sectors (SI Table 1 and 2) are consistent with the range proposed for this techno-complex in northern Iberia which is dated between 25.2–20.7 ka cal BP (Torres-Iglesias Reference Torres-Iglesias2023). These two 14C dates from La Viña, together with those from El Mirón level 127 (Straus and González Morales Reference Straus and González Morales2018; Hopkins et al. Reference Hopkins, Straus and González Morales2021) and Las Caldas level 15 (Corchón Reference Corchón2017), represent the earliest Solutrean human occupations in the Cantabrian region. Further dates are necessary for the central sector to get more precision during the Gravettian and Solutrean occupations.

The excessively excessive age and longer duration of the Middle Magdalenian in the western and central sectors are similarly explained by the constraint produced by the hiatus. Despite this seeming inconsistency, the modeled dates for levels IV and III in both sectors align with other well-documented Middle Magdalenian sites such as Las Caldas levels IX–VI (Corchón Reference Corchón2017) and the Lower Gallery of La Garma (Arias et al. Reference Arias, Álvarez-Fernández, Cueto, Elorza, García-Moncó, Güth, Iriarte, Teira, Zurro, Gaudzinski, Jöris, Sensburg, Street and Turner2011), indicating that the chronology of Middle Magdalenian occupations at La Viña is aligned with the Cantabrian chronological framework that is dated between 17.7–16.2 ka cal BP (Torres-Iglesias Reference Torres-Iglesias2023). In summary, the Date function gives the posterior for the date of an event (the duration of each archaeological level in our Bayesian chronological models), which is not directly dated but has temporal relationships to the other events expressed in the model. Therefore, we consider that this might be the cause for the broad date range of both Solutrean and Magdalenian technocultural complexes’ duration.

Conclusions

This study provides the general chronological sequence that allows establishing the temporal occupation of the different cultural human groups during the late Middle and Upper Paleolithic in La Viña rock shelter. From an archaeological perspective, this study resolves some questions arising from stratigraphically incoherent dates identified in both sectors of La Viña rock shelter, particularly at the lower sequence and the upper part during the Solutrean levels that took place during the Late Glacial Maximum and, where significant post-depositional processes occurred by eroding the previously accumulated deposits at that time, that affected both sectors. It allows us to propose the most likely ages for each culture, compare its duration between both sectors and provide the beginning and end of significant traditional cultural periods represented by human occupations at the rock shelter. Although evidence of similar material culture is found in each sector, no connected geo-stratigraphic sequence exists, and spatial differences in human use and temporal occupations between sectors are observed. However, somehow, it adds a degree of certainty to the correlation between both sectors that remained unknown until this study. The results confirm a relative continuous stratigraphic sequence along the Upper Paleolithic with diverse and multi-function occupations during the Aurignacian, Gravettian, Solutrean and Magdalenian, documented by a rich set of lithic artifacts on both from local and non-local raw materials, bone industry, charcoal and macromammal remains resulting from human subsistence strategies.

In general, the radiometric dates are also consonant with the diagnostic artifacts. Thus, La Viña contributes significantly to the debate over the nature and timing of the arrival of modern humans to north-western Iberian and on the development of the Noaillian Gravettian in the Cantabrian Region. Likewise, the Solutrean weapon technologies and Magdalenian are extremely rich in lithic and bone industries, along with limestone plaquettes engraved with zoomorphic (primarily horses) and linear motifs. In parallel, the two graphical horizons identified on the rock shelter wall confirm the existence of two chronological phases: the first one during the Evolved Aurignacian and the second one during the Solutrean.

The record of radiocarbon dates from La Viña rock shelter is one of the most complete and systematically developed in the Cantabrian region, complementing the long record of dates from El Mirón, which is especially well-endowed with dates from the Solutrean and Initial and Lower Magdalenian. Despite some significant depositional hiati and erosional events initially manifested by sterile level VII in the central sector, and later, thanks to the dating analysis in both sectors, the cultural chronostratigraphic sequence in the rock shelter is remarkably complete. The La Viña sequence thus provides a key chronological reference for the Middle to Upper Paleolithic transition and the development of the early phases of the Upper Paleolithic in the classic Cantabrian region of Spain.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/RDC.2025.10161

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the University of Oviedo for access to the archaeological collections. The authors are grateful for the various grants that supported this research. This long-term project has received funding from several funding agencies, including the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation (PID2021-125818NB-I00, HAR2017-84997-P, HAR2014-59183-P) and the European Research Council under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Programme (grant agreement number 818299; SUBSILIENCE project). L.T.-I. received support from the Government of Cantabria and the University of Cantabria through a “Concepción Arenal” PhD grant and the European Union’s Horizon Europe research and innovation program under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie grant agreement no. 101148342 (PALEOHUNTERS). L. G. Straus edited the English language of the manuscript.

Declaration of interest statement

All authors declare that they have contributed to this submission and have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.