Introduction

In March 2023 Baroness Casey published her Review into the standards of behaviour and internal culture of the Metropolitan Police Service (MPS).Footnote 1 Among other things, her analysis found the MPS to be institutionally racist: a label that the current Commissioner of the MPS (the Commissioner) has refused to accede to, albeit while accepting Casey’s findings.Footnote 2

In July 2023 the Supreme Court handed down its judgment in R (on the application of W80) v Director General of the Independent Office for Police Conduct (W80),Footnote 3 the key issue in which was the correct test for misconduct (in relation to officers’ state of mind) in cases of alleged excessive use of force. In W80, the Commissioner was joined by the National Police Chiefs Council and both parties argued that the more subjective criminal law test should apply. As set out below, their arguments would (if successful) have reduced levels of public scrutiny and police accountability for police use of force. Recognising this, the Supreme Court held that the correct test for a finding of misconduct for police use of force is the civil law test (which, as also outlined below, has a greater objective element and would therefore facilitate greater scrutiny and accountability).Footnote 4 Notwithstanding this, the Commissioner has pressed for the criminal law test to be reinstated.Footnote 5

Just two months after the ruling in W80, and in what was described by a former chief constable as resembling a ‘tantrum’, firearms officers in the Metropolitan Police downed their weapons in protest over the charging of officer Martyn Blake with murder following his shooting of Chris Kaba.Footnote 6 By the end of that month the then Home Secretary had ordered a review into investigatory arrangements in relation to police use of force.Footnote 7 This was strongly supported in an open letter from the Commissioner, in which he was clear in his support for officers and expressed concerns regarding current accountability processes and in particular the test for misconduct for use of force.Footnote 8 Following the change in Government in July 2024 the new Home Secretary ordered a further review regarding the test for use of force for misconduct, the outcome of which is still awaited.Footnote 9

Independent of the outcome of the more recent government review or subsequent policy decisions regarding police use of force, this paper makes an important contribution to debates about police accountability by introducing a new analytical framework that may apply to police accountability mechanisms globally and which can provide clarity of discussion and a novel means of comparative study. The analytical framework has, however, been developed in the context of wrestling with the multiple complex and interwoven issues raised by the current contention surrounding the correct test for misconduct for use for force (‘the use of force test’) (and which are addressed throughout the paper). This context is therefore used to explain and illustrate the framework, and, consequently, the paper also provides a timely contribution to substantive debates regarding the use of force test.

His Majesty’s Inspectorate of Constabularies, Fire and Rescue Servies (HMICFRS) inspects forces’ efficiency effectiveness and legitimacy,Footnote 10 and Police and Crime Commissioners (PCCs) can hold Chief Constables to account regarding how forces operate (and deal directly with some complaints issues).Footnote 11 However, neither HMICFRS or PCCs’ powers are sufficient to address some of the deeper issues around excessive force and disproportionate use of force against people who are racialised black and brown.Footnote 12 This is in part because, aside from reports and reviews such as the Casey Review, the ongoing impact of the corrupt and institutionally racist police processes noted by Casey is felt predominantly by citizens during their interactions with officers. These police processes are thus only likely to become evident via the complaints and conduct system (the CC system).Footnote 13 Further, while the HMICFRS, the College of Policing (COP) and the Independent Office of Police Conduct (IOPC) also oversee the relatively new super-complaint system, there has been no super-complaint to date relating to use of force. Furthermore, the terms of the super-complaint system are vagueFootnote 14 and initial results regarding its impact are unpromising.Footnote 15 Consequently, the analysis that follows brackets out these other potential oversight mechanisms regarding implementation of the Casey recommendations and focuses on the CC system.

Section 1 assesses the Casey Review in the context of additional broader evidence regarding police defensiveness in response to suggestions of wrongdoing and ‘values deficits’ at senior levels within forces.Footnote 16 The analysis reveals three core themes around which the CC system must operate if it is to assist in addressing the issues Casey highlights. Section 2 develops an analytical framework which develops these themes into axes of accountability, and Section 3 employs the framework to assess the structure of the current CC system. This paves the way for Section 4 to probe the impact of the criminal law test on the ability of the CC system to support the MPS in tackling the issues raised by Casey and in particular institutional racism. The paper concludes with additional observations and recommendations.

1. The Casey Review

Baroness Casey’s Review into the standards of behaviour and internal culture of the MPS (the Review) came in the wake of the murder of Sarah Everard by a serving Metropolitan Police officer, Wayne Cousins,Footnote 17 the photographing and sharing on a police WhatsApp group by two other MPS officers of images of the bodies of two female murder victims,Footnote 18 and allegations of rape (subsequently proved) against a further serving MPS officer, David Carrick.Footnote 19 Each of these officers fit the notion of ‘bad apples’ – a phase used to denote those officers whose behaviour is so wrong and/or corrupt that they should not be in the force.Footnote 20 Significantly, a focus on ‘bad apples’ has the corollary that their elimination will leave the rest of the ‘police’ apple barrel’s moral fortitude and professional standing intact. In contrast, Casey found the sap of the tree which produced and nurtured those apples to be contaminated with appalling misogyny, homophobia and institutional racism.Footnote 21 Importantly, for the argument here, the Casey Review also confirmed a deep cultural disregard within the MPS for accountability processes, and revealed officers being actively encouraged by their managers to use unlawful and excessive force.

These findings should not have been a surprise. Lack of moral fortitude and cultural defensiveness of senior police officers in the face of complaints and conduct issues has been recognised in political circles for some time. In 2014, the Chapman Review into the police disciplinary system noted a ‘values deficit’ within forcesFootnote 22 and devoted an entire heading to ‘The Lack of Culture of Challenging Performance Infractions at Every Level’ (emphasis added).Footnote 23 Chapman observed how misalignment between ‘stated values and the organisational or individual culture operating in practice can lead to cynicism and disengagement’Footnote 24 and found that behaviours were ‘defended at the expense of values’ such that ‘techniques and tools were used in an attempt to keep people in the force in relation to behaviours that would not be acceptable in recruiting’.Footnote 25 He thus advocated ‘interventions’ at ‘all levels to alter behaviours’Footnote 26 (emphasis added). More recently the Home Affairs Committee on Police Conduct and Complaints confirmed the need for cultural change at a senior level, concluding that a culture needed to be ‘created’ (sic) in forces that would result in ‘rapid, open and non-defensive response’ to complaints and that this had to be established (sic) and led ‘from the top’.Footnote 27

It is valuable to reflect on what the Casey Review reveals about senior management within the MPS. The Review’s analysis of MPS’s own data confirmed repeated findings of disproportionate force being used against people who are racialised black and brown, with ‘black appearing people in London aged 11–61’ being ‘over 3 times more likely to be handcuffed than white appearing people of the same age, 4.5 times more likely to have a baton used against them, and nearly 4 times as likely to have a Taser fired on them by a Met officer’.Footnote 28

Statistics of this nature can be misleading if the data on racialisation categories is compared with nationwide data. For example, if the proportion of black people in a particular borough of London is substantially higher than the national average, then apparent levels of disproportionality in relation to stop and search or use of force against black people in that borough will be inappropriately amplified if the national figures are used as the comparator. The Casey Review’s selection of people between 11 and 61 in London had attempted to address this issue. However, the MPS countered that their own research into the apparent disproportionality used a more apposite benchmark population and consequently indicated that ‘use of force is “only” (sic) 18% more likely to involve a Black person’.Footnote 29

using the London-wide population as a baseline can give a misleading perception of how our officers are making decisions … an alternative approach is to use our custody population as a reasonable representation of the types of people our officers encounter in situations that could lead to the use of force.Footnote 30 (emphasis added)Footnote 31

This citation is taken from an Internal Management Board paper, ‘MPS use of force analysis’ dated December 2020. Therefore, in line with the findings of the Home Affairs Committee noted above, it reveals a senior personnel ‘logic’ that tends towards seeking to justify disproportionate use of force rather than addressing it. Further, as the Casey Review correctly points out, the methodology adopted by the MPS – and seemingly approved by MPS management – misses the crucial point that using the custody population as a measure fails to capture any existing bias that may have contributed to that population containing a disproportionate number of people from racialised groups. Moreover, even when the custody population was used as the comparator, there was still substantial disproportionality based on the MPS’s own data. The use of this measure and the reference to this research in the context of the Casey Review underscores the entrenched and blinkered refusal by senior MPS officers to accept the ongoing practical implications of repeated findings of institutional racism within the MPS.Footnote 32

This refusal is more recently exemplified by the MPS having failed to fully engage with the subcommittee of the London Policing Board (established to oversee implementation of Casey’s findings) that focuses on cultural change.Footnote 33 In addition, the Commissioner’s John Harris Memorial Lecture in September 2024 arguably demonstrated his own ongoing unwitting bias and confirmed continuing institutional racism within the MPS.Footnote 34 Moreover, in his response to questions after the lecture, the Commissioner reductively aligned good policing with the proportion of arrests per officer, a sentiment that is antithetical to encouragement of de-escalation and which therefore may encourage unnecessary use of force against citizens.Footnote 35

Significantly, these comments by the Commissioner echo some of Casey’s findings regarding use of force. Her Review gives a graphic example of a group of new officers being brought together and shown numerous pieces of video footage where force had been used, and which were presented as examples of good practice. The Report describes one of these as a Taser being used on a man who was in hospital, wearing a hospital gown and not presenting any sign of danger. One of the officers from the group told the Review that ‘the examples were so horrific that she and her fellow officers thought this was a test of their integrity’.Footnote 36 When she questioned it she says she was told ‘that’s the Hendon [training school] way, and this is real life’.Footnote 37 The same new-in-service officer reported surprise that senior officers would push more junior officers to meet targets for using force and that she was specifically told ‘we’ve looked at the figures, use of force isn’t being used enough’.Footnote 38

These Review findings suggest acceptance and indeed encouragement (at least within the MPS) of the use of unlawful force against citizens by the body whose role it is to protect them. Crucially, these ‘in-house training’ practices must go hand in hand with an internal understanding or recognition that when officers go on to use such unlawful levels of force against citizens (or importantly the types of people against whom such unlawful force was encouraged in the videos) these officers would be ‘supported’ in those ‘professional’ choices by officers in the Department of Professional Standards (DPS).

Furthermore, while the Casey Review was not primarily concerned with how the MPS’s DPS handles public complaints concerning use of force, it does reveal substantial failings within the MPS DPS in relation to other matters, and it seems unlikely that the corrupt DPS practices she found in relation to these matters do not extend to conduct matters and public complaints in relation to use of force. For example, the Review lists many examples of DPS’s failing adequately to address (or simply dismissing) allegations and complaints made by serving officers concerning bullying and racist, misogynistic and homophobic behaviour by fellow (and frequently senior) officers. Further, one former DPS officer who was prepared to speak to the Review team explained how senior officers had been ‘known to call in favours to protect their friends and allies from investigation, or to water down the investigation’.Footnote 39 Other former DPS officers also referred (in relation to both public and internal complaints) to a well-known nickname for DPS as the ‘department of double standards’ and spoke of misconduct reports being sent ‘back to borough’ to be dealt with as lower-level issues and thereby reduce (apparent) levels of gross misconduct.Footnote 40 These findings are consistent with detailed analysis indicating a propensity in DPSs to preserve what Torrible has referred to as the ‘internal and external faces’ of police complaint and conduct processes.Footnote 41 The external face of the CC system is maintained by a rigid and narrow approach to evidence gathering (and how it is evaluated) which facilitates a finding of no misconduct. Meanwhile, the internal face of the CC system operates ‘behind the curtain’ of the finding of ‘no misconduct’ and preserves the actual lines of acceptable conduct to opaque internal police processes (which may feature both conscious and unconscious bias). In doing so it preserves to internal police determination which ‘types of people’ can be subjected to excessive force with impunity and, significantly, which officers may be afforded leniency, and which may be subject to a strict interpretation of the standards of professional behaviour and referred to disciplinary processes. As the literature on procedural justice confirms, the potential for arbitrary enforcement of standards will tend to negatively impact compliance with those standards. These issues therefore combine to confirm the need for the CC system to provide meaningful oversight of DPS practices.Footnote 42

Moreover, research (not limited to the MPS) indicates a degree of cynicism in formal police training which appears to knowingly facilitate expansion of the ‘internal face’ and encourage officers in obfuscation techniques that limit their accountability for use of force. Officers are trained to operate by reference to a National Decision Model (NDM). This is developed by the COP and appears both as one of the elements of the COP’s authorised professional practice and in its Code of Ethics.Footnote 43 The Code of Ethics is designed to provide a broader framework to ‘underpin’ the standards of professional behaviour and help officers interpret them in a consistent way. It should also ‘inform any assessment or judgement of conduct when deciding whether formal action should be taken under the Conduct Regulations’.Footnote 44

The COP website indicates that the NDM is designed to help structure decision-making in both pre-planned operations and fast moving less controlled policing environments.Footnote 45 However, evidence indicates that officers are also encouraged to retrospectively rationalise or justify their actions by reference to the NDM in order to evade questions regarding their accounts of events. The COP website depicts the NDM in the shape of a hexagon with the ‘Code of Ethics’ in the centre and arrows pointing from it to five boxes which circle the hexagon, and which themselves have arrows from one to another in a clockwise direction. The five boxes each have instructions and, working clockwise from the top, these read ‘gather information and intelligence, ‘assess threat and risk and develop a working strategy’, ‘consider powers and policy’, ‘identify options and contingencies’ and ‘take action and review what happened’. In Dymond’s interviews with police officers and trainers one trainer explained

The threat and risk box (on the NDM) is completely your personalised view of the world. Every decision you make is influenced by what you put in that box – it influences everything that comes after it. ‘I was scared’ – personalising that threat assessment is the key to your success (emphasis added).Footnote 46

Accordingly, one of the officers explained how this undermines transparency and accountability

If we ever end up in court justifying our actions, the barrister will be questioning us on the NDM. As soon as … they realise you know it, then the questions stop because they know they are not going to catch you out … The barrister sits down, so the actual justification and use (of force) can never be questioned. Footnote 47 (emphasis added)

A further police trainer openly referred to the NDM as a ‘get out of jail free card’.Footnote 48 Thus, it is suggested that the NDM provides account-ability (ie capacity to explain their activities in a credible manner) rather than aiding accountability,Footnote 49 and that managers and police trainers are not only aware of this but actively groom officers to use it in this way. This again raises the importance of the depth of the oversight provided by the CC system. Importantly, however, the apparent role of the NDM in facilitating conscious evasion of the rule of law at an institutional level by obscuring meaningful judicial oversight of the use of force elevates these concerns from the practical and regulatory to the constitutional.

2. Axes of accountability and police accountability processes

The previous section indicates that it is not enough for the CC system to focus on ‘bad apples’ and the regulation of officers’ conduct more generally, but that it must also be concerned with the internal cultural practices that promote excessive use of force, and the related internal efforts within the police institution to evade appropriate constitutional oversight of these practices. This section draws on these observations to develop an analytical framework in relation to police accountability. Crucially, this is not a blueprint for a new CC system (though it could be adapted to assist with such an endeavour). Instead, it provides a means to assess arguments about the structure and functioning of the CC system and make clear the implications of policy choices in relation to reform.

(a) Conceptual, discursive and semantic difficulties

Policing is a complex, multifaceted and necessarily contested social practice.Footnote 50 In addition, clarity of debate regarding the use of force test is made difficult by the intricate interrelation of the issues at play. The stated purposes of the CC system are ‘to maintain public confidence in, and the reputation of, the police service’, ‘to uphold high standards in policing and deter misconduct’, and ‘to protect the public’.Footnote 51 However, the inherently contested nature of policing inevitably makes ‘what good looks like’ in relation to these functions also open to debate. Furthermore, the preferred use of force test is inherently intertwined with underlying presumptions about how the stated functions of CC system might be achieved. For example, a predominantly subjective test that focuses on officers’ honest belief accords with the conception of the public being protected by disciplinary processes that are effective in identifying and expelling officers who purposefully abuse their position. In contrast, a more objective test aligns with the belief that maintenance of public confidence (and policing by consent) will be better served by a system that affords greater transparency concerning how the practical boundaries of the level of force routinely used against citizens are determined and monitored. These issues are expanded upon below and details of the potential tests and their implications are discussed in Section 4. However, for now, it is sufficient to note that analysis or discussions concerning the preferred use of force test which attempt to centre themselves on the function of the CC system will inevitably descend into confusion and circularity due to the multiple interconnected and contested conceptions of policing and police accountability upon which they would necessarily be founded.

These discursive/analytical difficulties are further compounded by semantic uncertainty stemming from the self-referential definition of ‘misconduct’ and ‘gross misconduct’. Police officers are required to comply with the standards of professional behaviour (the Standards).Footnote 52 ‘Misconduct’ is defined as a breach of the Standards that is sufficiently serious to warrant the disciplinary outcomes associated with misconduct proceedings. Similarly, ‘gross misconduct’ is a breach of the Standards that is sufficiently serious to warrant dismissal.Footnote 53 Confusion is thus invited by inherent links between the preferred test of misconduct and the resulting meaning accorded to the word ‘misconduct’. For example, if one is of the view that the function of misconduct proceedings for use of force is appropriately limited to occasions when officers did not honestly believe force (or the level of force used) was necessary, then, when referring to ‘misconduct’ and ‘the misconduct system’ that normative stance necessarily infuses all discussion and the presumed meanings of the key nominals (ie ‘misconduct’ etc). In contrast, if one considers that the proper role of misconduct proceedings is broader, then the same key nominals carry contrary infused meanings.

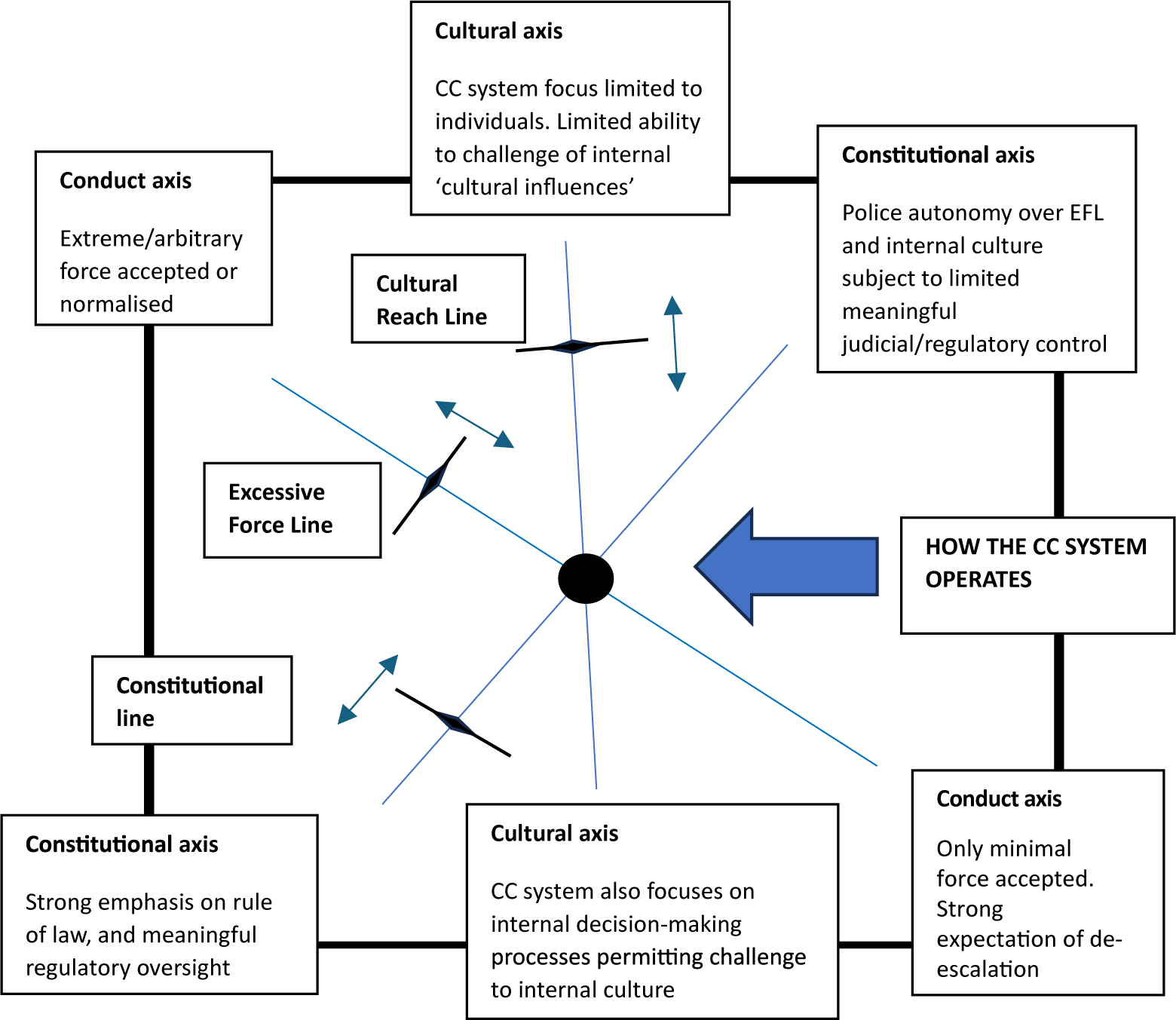

Therefore, rather than adopting an analysis that centres on the meaning of ‘misconduct’ or the stated function of the CC system, this paper advances a methodology that steps outside the interconnected linguistic and conceptual confusion. The discussion in Section 1 highlighted three broad areas of concern. The first is the actual boundaries of what amounts to excessive/unlawful force in the context of police officers’ interactions with citizens. The second is what may be referred to as the cultural reach of the CC system, ie how deeply it can cast light on what Casey revealed as potentially murky internal practices that extend to DPS’s turning a blind eye to instances of excessive use of force and police trainers actively encouraging or facilitating the use of (and obfuscation concerning) unlawful levels of force against citizens. The third stems from the first two and is an overarching constitutional concern regarding how the CC system contributes to appropriate constitutional constraint of police use of force. An analytic framework is therefore proposed which conceives each of these areas of concern as distinct axes along which any CC system might sit. As described in the next three subsections (and illustrated in Figure 1 below) this permits analysis to be centred around movable points on these ‘accountability axes’ so that suggested reforms and arguments concerning them can be assessed by reference to the direction in which they push the CC system in relation to each axis.

Figure 1. Within the figure the positioning of the ‘lines’ along each axis and the centre ‘functioning’ of the CC system is for illustration purposes and does not purport to make any substantive point regarding the CC system in England and Wales.

(b) The conduct (excessive force) axisFootnote 54

Focusing first on the level of force used against citizens, one can imagine a continuum at one end of which high levels of potentially arbitrary force are sufficiently commonplace to acquire accepted status.Footnote 55 At the other end of this continuum, police use of force will be carefully monitored and high standards in policing will be equated with minimal use of force and maximum efforts expended on de-escalation of potential citizen/officer conflict.

The CC system is one of the central structural factors influencing officer conduct. Chief constables may be sued in relation to officers’ use of force but these civil actions tend to have limited consequences for officers.Footnote 56 Therefore, short of criminal sanction it is the threat of potential misconduct proceedings that is likely to have most impact on officers’ behaviours.Footnote 57 Consequently, notwithstanding laws that limit police use of force, or the wording of the Standards etc, it is the point at which a given set of circumstances results in potential disciplinary consequences for officers that will tend to be determinative of the de facto levels of force commonly used against citizens. This Excessive Force Line (EFL) is thus the practical output of internally ‘accepted’ standards which may not align with whether the force was technically lawful and may include the high levels of unlawful force noted in Section 1. It is accepted that the EFL is changeable and indeterminate. However, the value of the proposed analytical framework is that by conceiving the EFL as a fluid point on the conduct (excessive force) axis (which may be moved in more or less permissive directions by the operation of the CC system) potential reforms can be assessed by reference to their impact on the direction in which they push the EFL along the axis.

De-centring the label ‘misconduct’ and instead focusing on the crucial (if fluid) EFL allows other interrelated threads and issues to be more clearly distinguished and articulated. For example, officers must deal with very difficult, emotionally volatile and violent (or potentially violent) situations. An emphasis on the difficulty of the police role and the employment consequences for officers when faced with potential misconduct processes invites leniency around when an incident of excessive use of force is treated as misconduct. Such a lens may tend to be forgiving of single episodes of potentially ‘excessive’ force. Significantly, it may also be more inclined to interpret an incident of (arguably) excessive use of force as an error of judgement rather than a lack of professional self-discipline. This viewpoint is thus likely to be cumulatively tolerant of higher levels of force being used against citizens (as standard) and thus push the EFL in a more permissive direction. In contrast, when perceived from a citizen’s perspective the interpretation of officers’ use of force will tend to centre on the impact on the individual citizen, their (and their communities’) trust in the police, and legal and constitutional concerns regarding the appropriate limits of state power. This will, therefore, tend to push the EFL in a direction that is more concerned to restrain and discourage the use force against citizens. Thus, conceiving of these two valid but competing standpoints by reference to their impact on where the EFL sits along the conduct axis allows debate that is accurately and openly alive to the consequences of how a balance between them is achieved (and that can therefore seek to mitigate the negative consequences of a choice in either direction).

(c) The cultural axis

The idea of misconduct has individual blame-focused connotations. However, misconduct proceedings are only one potential endpoint of the much more elaborate CC system, the overall function of which overlaps with the function of misconduct proceedings but the focus of which is necessarily broader than individual officers’ behaviours.Footnote 58 For example, as discussed below, the CC system has a substantial focus on individual and institutional learning. Similarly, the COP Guidance on Outcomes of Misconduct Proceedings (the Outcomes Guidance) recognises that the larger requirement of public confidence in policing may sometimes take precedence over immediate concerns regarding the level of sanction given to individual officers.Footnote 59

Accordingly, another axis can be envisaged whereby, at one extreme, the CC system is seen as appropriately predominantly focused on ‘bad apples’ with corollaries that the rest of the ‘barrel’ is above reproach and correspondingly that DPS officers’ decision-making requires limited scrutiny. In contrast, the other end of the axis would acknowledge the broader impact of police operational culture on DPSs’ assessments of officers’ conduct. Crucially, this end of the axis would also recognise the reciprocal impact of DPSs’ actions in potentially facilitating and maintaining some of the more concerning aspects of police culture. On this view the CC system is necessarily concerned with providing transparency regarding DPS decision-making and how officers are incentivised in relation to use of force (and, for example, how institutional racism and unconscious bias in relation to use of force are monitored and addressed). Isolating the cultural axis allows reforms within the CC system to be assessed by reference to how they impact the ‘cultural reach’ line and whether they push it in the direction of shallower or deeper scrutiny of internal police practices. This is important because it requires the evidence of problematic internal processes (discussed in Section 1) to be fully acknowledged in debates about such reforms and accordingly obliges discussion concerning how they may be addressed.

(d) The constitutional axis

In a democracy that adheres to the rule of law the legal boundaries regarding police use of force are set out in statutes and regulations which are ultimately interpreted by the courts. Debates regarding independent oversight or accountability of the police therefore tend to centre on whether officers comply (and forces enforce) statutory or regulatory lines that are sufficiently clear and subject to sufficient meaningful regulatory and judicial oversight for the police as an institution to be seen as subject to the rule of law. On this conception, the role of DPS officers within the CC system is limited to interpretation and practical application (in individual cases) of clearly articulated regulations. Similarly, on this view, the IOPC (discussed below) sits between the COP and the courts (ie between professional and formal constitutional controls) to provide statutory guidance and oversight of that DPS role.Footnote 60 The constitutional axis is concerned with how the CC system impacts the balance of practical power between the DPS, the COP, the IOPC and the Courts. Thus, the more formal ‘tighter’ end of the constitutional axis can be seen as requiring the CC system to have a clear focus on ensuring that the police institution’s interpretive role is transparent and appropriately restrained. The other ‘looser’ end of the axis may extend police institutions’ de facto autonomy such that meaningful regulatory and judicial oversight is downgraded. For example, Section a noted how reliance on the NDM permits the police autonomy over the EFL in ways that are not easily reviewed by the Court. The constitutional axis is concerned with the extent to which the structure and tests within the CC system go beyond giving the police an appropriate role in professional regulation of officers’ conduct to potentially providing the police institution with a de facto declarative role regarding the boundaries of police use of force against citizens.

The constitutional axis is valuable because it demands that appropriate consideration is given to the impact of reforms on the practical boundaries of police autonomy at a constitutional level. This is important in England and Wales because a series of changes over the last quarter of a century have weakened the degree of judicial oversight to which the police are subject.Footnote 61 More broadly, in a world where autocratic government is on the rise and the rule of law is under constant threat, attention to detail regarding incremental reductions in constitutional control of the police is imperative.Footnote 62

3. The complains and conduct system

In preparation for analysis of the impact of potential use of force tests on the ability of the CC system to address the issues raised by the Casey Review, this section employs the accountability axes framework to assess key features of the CC system in England and Wales.

(a) Background

The most recent structural reforms to the CC system stem from the Policing and Crime Act 2017 (PACA 2017)). This aimed to replace what was referred to as a ‘damaging blame culture’ within the police with a more open approach to mistakes that would encourage lesson-learning. Reforms in 2008 and 2012Footnote 63 sought to introduce a system that recognised employment law principles, and which created a more open ‘lesson-learning’ environment. Notwithstanding these, and the findings of the Chapman Review (discussed above), the consultation that preceded the PACA 2017 was premised on the view that a ‘blame culture’ persisted.Footnote 64 Accordingly, the Act further shifted the emphasis within the CC system towards ‘reasonable and proportionate’ responses to allegations of misconduct which prioritised reflective practice directed towards lesson-learning.Footnote 65

(b) The CC system

Several aspects of the CC system facilitate the EFL being interpreted in a more permissive way. The overarching principle of ‘reasonable and proportionate handling’ requires ‘weighing up a matter’s seriousness and its potential for learning, against the efficient use of policing resources, to determine the extent and nature of the matter’s handling and outcome’.Footnote 66 In addition, while earlier regulations provided for any breach of the Standards to trigger disciplinary processes, under the PACA 2017 regime only conduct which, if proved, would result in disciplinary proceedings for misconduct or gross misconduct invokes misconduct processes.Footnote 67 To complement this change the PACA 2017 also introduced a reflective practice review procedure (RPR) which channels other potential concerns about officer conduct (classed as ‘practice requiring improvement’ (PRI)) to a non-disciplinary process that focuses on lesson-learning.

The principal focus of the [RPR] process will be to learn and to develop by improving from mistakes, errors and low-level wrongdoing. It is intended to address such matters which often demonstrate a combination of behavioural, conduct and performance issues which are below the expected standards but do not justify formal performance or disciplinary proceedings.Footnote 68

The statutory labelling of low-level wrongdoing as PRI and establishment of the RPR process effectively introduces an intermediate ‘tolerated’ level of force which is recognised as excessive and may include ‘wrongdoing’ but is nevertheless insufficient to warrant a disciplinary outcome. It is appropriate that lower-level matters should be handled by the RPR and frequently citizens affected by this type of conduct confirm that this would be their preferred outcome.Footnote 69 However, a tension arises because the relative power positions of police and citizensFootnote 70 also requires the boundaries of what is appropriately referred to RPR to be robust and transparent. The stated focus of RPR accepts that the distinction between what amounts to a mistake, an error, or to low-level wrongdoing may be difficult to assess and that some behaviours can include all three. However, the principle of reasonable and proportionate handling militates against probing that distinction. For example, the requirement to weigh the efficient use of resources in determining the extent and nature of a matter’s handling tends to encourage a decision towards the less time-consuming route. This may be an appropriate use of resources, but it has the potential to push the EFL in a permissive direction and may impede early identification of rogue officers. It also increases police autonomy over internal practices (such as those noted by Casey) which may encourage the use of unlawful excessive force against citizens.

These concerns may be mitigated by the role of the IOPC.Footnote 71 All incidents that have resulted in death or serious injury must be referred to the IOPC and it is empowered to undertake independent investigations into the most serious allegations of police misconduct (involving force and more generally).Footnote 72 It also has power to review the outcomes of internally handled police complaints.Footnote 73 Further, alongside publishing statutory guidance concerning the handling of police complaints, the IOPC uses data from its investigation and review processes to make recommendations to forces and publishes lesson-learning bulletins about specific police practices.Footnote 74

The IOPC’s investigatory role is, however, limited. In the year 2021/22, of the 17,819 conduct and complaints matters that were investigated only 262 of these investigations were undertaken by the IOPC. Similarly, while all incidents that have resulted in death or serious injury must be referred to the IOPC, officers are empowered to cause high levels of injury as a legitimate part of their duties.Footnote 75 So the fact of mandatory referral based on injury is not of direct assistance as regards the IOPC’s oversight of the boundaries of the EFL which necessarily involves qualitative assessment that extends beyond the level of injury. Further, the IOPC’s power of review (which would apply to levels of force that may not have resulted in significant injury) is limited to whether the outcome of an internal determination is ‘reasonable and proportionate’. This is in the context of the broad and amorphous boundaries of what amounts to ‘reasonable and proportionate handling’ noted above. The RPR process, the principles of reasonable and proportionate handling and indeterminacy regarding ‘misconduct’ etc therefore combine to create a very wide margin within which differing views on what amounts to a reasonable and proportionate outcome would have to be accepted. Collectively therefore, they push the cultural reach line towards more shallow scrutiny.

In contrast, the CC system appears to sit towards the tighter end of the constitutional axis in the sense that the recent limitations on the practical boundaries of the IOPC’s role are laid down in PACA 2017 and its associated and properly promulgated regulations, and Home Office Guidance is similarly correctly promulgated.Footnote 76 Moreover, the constitutional legitimacy of police use of force is arguably enhanced by judicial oversight via civil actions against the police which allege assault etc.Footnote 77

However, there are several factors that suggest constitutional control over police use of force has loosened in recent years. In practical terms, judicial oversight via civil actions is substantially limited by procedural constraints that frequently make it financially impossible for citizens to test the police (and indeed IOPC) interpretation of evidence and events in individual cases.Footnote 78 Further, as outlined above and demonstrated by Casey’s findings, notwithstanding the Court’s declarative role, the EFL is practically defined by internal police processes. Meanwhile, (as discussed below) police stakeholders are increasingly pressing for the content of officers’ training to be a benchmark for courts’ interpretation of legislation/regulations (eg what amounts to ‘reasonable force’).Footnote 79 This then is the context in which we must assess current debates about the use of force test.

4. The implications of the criminal law test

(a) The potential tests for misconduct for use of force

Police officers can rely on the law of self-defence in criminal and civil proceedings if the officer (A) can prove that they honestly believed (albeit mistakenly) that ‘B’ posed a threat to their or another’s safety at the point they used the force against ‘B’. Similarly, in both the civil and criminal law tests the degree of force used against B must be proportionate to A’s honestly-held belief. Significantly, however, in the criminal test the honesty of A’s belief is sufficient even if that belief is unreasonable. Thus, while the extent to which A’s belief is ‘unreasonable’ may impact whether A’s account is believed, an unreasonably held but nonetheless honest belief will still afford A the defence. In contrast the civil law test demands A’s mistake as regards the threat (and need for force) is an objectively reasonable one to hold.Footnote 80 In both tests it is accepted that the level of force cannot be ‘weighed to a nicety’ in the inevitably fraught circumstances that must have existed for the defence to be raised.Footnote 81

The criminal law and civil law tests have developed to serve the functions of those processes (ie determining criminal guilt or civil liability).Footnote 82 Significantly, neither of these align with the complex and distinct purposes of the CC system. This persuaded the Court of Appeal in W80 that police misconduct processes are sui generis and accordingly, they held the formulation in the Police Conduct Regulations – that force should be used only to the extent that it is necessary, proportionate and reasonable in all the circumstances – to be the correct test.Footnote 83

It is of note that guidance that was comprehensively negotiated with multiple stakeholders at the time this Standard was established (but which is no longer in force) states:

It is for the officer to justify his or her use of force but when assessing whether this was necessary, proportionate and reasonable all the circumstances should be taken into account and especially the situation which the police officer faced at the time. Police officers use force only if other means are or may be ineffective in achieving the intended result.Footnote 84

It has been argued elsewhere that the CC system needs to be re-imagined around the specific purposes it is seeking to achieve but that if it is to be retained in its current form, the regulatory test supplemented by the guidance above serves the complex needs of CC system better than the civil law test stipulated by the Supreme Court.Footnote 85 Thus, in analysing the implications of the criminal law test, comparison will be made to the position provided by a generally more objective test (rather than distinguishing the civil law test or the sui generis/regulatory test).

(b) Arguments in favour of the criminal law test and their implications

Those who advocate the criminal law test as the use of force test adhere to the assumptions noted in Section 3. that the necessarily high bar it sets for misconduct facilitates an open, lesson-learning culture that will raise standards by encouraging reflection and lesson-learning. They also emphasise the difficulties faced by individual officers who have to make split-second decisions in high pressure circumstances.Footnote 86 The case is made that officers should not have to operate under the shadow of an overbearing misconduct process that threatens to punish them unfairly based on objective, ex post facto, determinations that the degree of force they used was unwarranted.Footnote 87

In addition, specific arguments are put forward in relation to the use of potentially fatal force by firearms officers. Here the pressure on officers is heightened by the severity of the surrounding circumstances where the person targeted is perceived as posing an immediate threat to the public. In W80 it was stressed that fear of unfairly harsh repercussions resulted in difficulties with recruitment and retention of firearms officers, which could also have an impact of public safety and public confidence in the police.Footnote 88 The additional argument was raised by police stakeholders that public confidence in armed policing operations would be undermined if police officers were more hesitant to discharge their firearms in such circumstances for fear of discipline and dismissal.Footnote 89 These are valid concerns, and it is important not to underestimate the heavy burden of responsibility (and associated stress) firearms officers accept in relation to the enormity of the consequences of a decision not to fire in certain circumstances as well as the decision to fire.

The analytical framework developed in Section 2 allows these arguments to be assessed by reference to their implications along the axes of accountability. It thereby lays bare the implications of the policy choices inherent in the selection of the criminal law or more objective tests. This in turn allows appropriate justifications (or means of mitigating less desired consequences of such choices) to be sought.

(i) Unfair to officers, the RPR, and some cultural issues

The assertion that more objective tests would fail to lend officers sufficient support in the difficult job they do should be treated with some caution. The more objective tests still require the tribunal (and CC system more generally) to take all the surrounding circumstances into account in assessing the reasonableness of officers’ mistaken belief concerning their use of force. It is contended that in the highly fraught situations where officers have truly had to make split-second decisions, the practical difference between the criminal and more objective tests in assessing the impact of the surrounding circumstances is likely to be minimal.

Meanwhile, the criminal law test provides officers with extremely high levels of protection regarding use of force (nearing immunity in many instances). As noted by Dymond’s interviewees, a claim to an honest belief that circumstances necessitated force is very hard to refute. Further, it must be recalled that whichever test is adopted, it applies not only in disciplinary proceedings but to assessments of the ‘seriousness’ of officers’ conduct and what amounts to ‘reasonable and proportionate handling’ at every stage of the CC system. Consequently, if a manager or DPS officer is sceptical about an officer’s account, the criminal law test (alongside the principles of reasonable and proportionate handling) makes it difficult for them to press for a misconduct process for excessive use of force unless it has resulted in substantial harm. The criminal law test may, therefore, push the EFL in a significantly permissive direction as regards the level of ‘every-day’ force used against citizens (and may limit early intervention in relation to potentially ‘rogue’ officers).

Moreover, the wealth of evidence pointed to in Section 1 should not be overlooked. The highly subjective measure of an officer’s honest belief facilitated by the criminal law test has correlative impact on the ability of oversight mechanisms to query the objective reasonableness of DPS decision-making regarding the officer’s purported belief. The criminal law test therefore assists those DPS officers who may be inclined to downgrade the seriousness of allegations and accordingly may also facilitate those police managers who encourage or condone unlawful levels of force.Footnote 90 In sum, the criminal law test necessarily hampers internal attempts to implement change while simultaneously pushing the cultural reach of the CC system in the direction of shallower scrutiny by limiting meaningful IOPC oversight.

Furthermore, far from increasing fairness to officers, the uncertain environment created by the increased police autonomy and limited oversight of DPS decision-making (that the criminal law test would facilitate) potentially invites increased unfairness to officers. For example, the account in the Casey Review of officers being shown videos encouraging unlawful force highlights cultural issues which may make it unfair to impose disciplinary processes on individual officers whose behaviour, while outside acceptable police conduct, is nonetheless consistent with informal and unlawful standards encouraged or required by their managers. However, the limited cultural reach of the CC system facilitated by the criminal law test would increase the scope for arbitrary enforcement of the formal standards against an officer who is dis-preferred. In this regard, it is noteworthy that officers categorised as ‘BAME’ are subject to substantial disproportionality in relation to misconduct and disciplinary processes.Footnote 91

Importantly, the criminal law test’s focus on the honesty of officers’ stated belief would encourage any officer who is in doubt about the consequences for them of an incident involving use of force, to overstate the level of threat they perceived, and potentially extend this to lying about their understanding of and responses to the surrounding circumstances (and this is true of even relatively minor events). Simultaneously, the motivation to err in the direction of overstatement/dishonesty is increased by the potentially arbitrary enforcement of standards by DPS officers which, as noted above, the criminal law test may facilitate. The implications of the test are thus anathema to RPR process and the focus on professionalism, integrity and lesson-learning at several levels.

A system which encourages officers to overstate the level of threat they perceive in relation to incidents where they may have failed to de-escalate (or engaged in arbitrary force) necessarily also encourages the well-documented practice of officers making false allegations of assault against citizens.Footnote 92 It should therefore be resisted.

In contrast, objectively-framed tests which foreground the reasonableness of officers’ beliefs still insist that all the circumstances the offer was facing be fully taken into account. They therefore promote frank discussion and exploration of errors at all stages of the CC system. Furthermore, as regards standards and lesson-learning, while both the criminal law test and more objective tests may probe offices’ accounts to assess what other strategies were available to them before resorting to force, a more objective test will invite broader enquiry and extend the degree to which the rights of the citizen that was subjected to force feature in evaluation of the surrounding circumstances.Footnote 93 For example, the criminal law test has temporal implications because, despite the requirement that all the surrounding circumstances be taken into account, the primary focus is the time the force was used. This deflects attention away from earlier stages in the interaction, when the officers could/should have sought to de-escalate. It thus reduces lesson-learning, diminishes the quality of lessons learned and further pushes the EFL in a more permissive direction.

Crucially in this regard, while allowance for officers’ split-second professional choices is important, effective challenge of institutional racism requires a nuanced appreciation of how conscious or unconscious bias may infuse officers’ decision-making in these critical moments. A system founded on the subjectively honest belief of the criminal law test cannot effectively challenge officers’ unconscious bias at this level. Similarly, the criminal law test limits transparency and oversight regarding the propensity, ability or willingness of police managers and DPS officers to challenge unconscious bias in this way.

Ironically, while – as noted above – the criminal law test may not only encourage officers to give an initial account of events that incorporates a purportedly honest (but disingenuous) account of their belief that the force used was necessary and proportionate, it also simultaneously makes the honesty of an officer’s account the primary focus of attention. Thus, contrary to the aims of the PACA 2017, the criminal law test is more blame-focused than more objective tests because the question is the officer’s integrity in relation to their account of events, rather than a matter of taking professional responsibility for their actions (which would be the outcome on application of a more objective test).

Furthermore, the open and objective aspects of the RPR are facilitated by a significant evidential rule whereby, if discussions during the RPR process result in it being deemed necessary to escalate the matter to misconduct, statements made by an officer during the RPR are not admissible in any subsequent disciplinary proceedings brought against the officer in relation to the subject of the RPR.Footnote 94 While this may be appropriate, the criminal law test provides officers with the fallback position of reliance on their difficult-to-refute purportedly honest belief, if the allegation is escalated to misconduct. This sits uncomfortably with the COP Code of Ethics and the Standards of professional behaviour which require honesty and integrity.Footnote 95

The focus on honesty has two further important consequences. First, by making an officer’s honesty the prime issue at stake, the sense of moral blame inherent in the criminal law test results in misconduct processes carrying an intrinsic suggestion of dishonesty even if officers are found not to have been in breach of the Standards. It may therefore taint an officer’s future testimony on other matters by giving defence lawyers scope to question the officer’s integrity. In contrast, a focus on professional responsibility for one’s actions on a single occasion does not necessarily invite doubt over the veracity of later testimony.

In addition, the focus on officers’ honesty invites the conclusion that, once it is determined that the offices’ account is plausible, the outcome of ‘no misconduct’ is inappropriately equated with the notion that the officer did nothing wrong. This is antithetical to the individual and institutional lesson-learning the PACA 2017 was seeking to encourage. More subtly, it also reinforces a cultural sense within forces that they are under attack from all sides, which may increase cynicism and disregard for the rules.Footnote 96

These observations suggest that the purported benefits of the high bar for misconduct as regards fairness to officers and lesson-learning should be carefully evidenced. In addition, policymakers would have to be clear about how they weigh that evidence against the consequences of the criminal law test on the EFL and the cultural reach of the CC system in the context of the evidence discussed in Section 1.

(ii) The criminal law test, conceptions of ‘the public’ and institutional racism

As noted in Section 2 the stated purposes of the CC system is ‘to maintain public confidence in, and the reputation of, the police service’, ‘to uphold high standards in policing and deter misconduct’, and ‘to protect the public’.Footnote 97 As also noted, the question of how each of these ends might most effectively be promoted by the CC system is necessarily contested. It is nonetheless valuable to focus on the aim of public protection because arguments put forward in relation to the criminal law test reveal subtle institutional racism regarding how the public is perceived in relation to this function.

The public may be protected in the sense of being ‘protected from the police’ by a CC system which effectively expels officers who purposefully use their police powers to nefarious ends. This conception of public protection has few consequences for how ‘the public’ is conceived because the focus is predominantly on officers. It is nonetheless noteworthy that in seeking to eliminate bad apples an objective test will not prevent officers who engage in serious gratuitous violence being identified. Meanwhile, the high bar set by the criminal law test may permit several substantially rotten apples to evade disciplinary action.

Alternatively, the public may be protected in the sense of being protected by the police. This is exemplified by firearms operations when officers may use force to prevent one individual from harming others. As noted above, advocates of the criminal law test maintain that public confidence and public protection would be reduced if firearms officers were discouraged from shooting in these circumstances for fear of subsequently being subject to objective reasoning regarding their actions.Footnote 98 The assumptions about public protection and its links with public confidence that underlie this argument require careful analysis.

First, as noted above, limiting assessment of a scenario to the plausibility of officers’ stated beliefs at the time the force was used precludes or limits exploration of the degree to which unconscious bias may have infused those officers’ assessment of the level of threat. Further, the contention that public protection will be enhanced by officers feeling unfettered by objective reasoning in their use of fatal force assumes that the person who is subject to that force is not a member of the public. Significantly, therefore, in circumstances where force is routinely used disproportionately against people from groups that are racialised black or brown, the presumption that ‘public’ confidence will be increased by less reflection by officers before resorting to (potentially fatal) force tends to suggest that the public conceived of in this assumption is white.

Secondly, the relationship between policing, levels of crime, and public disorder is complex. The vast literature on procedural justice confirms repeatedly that treatment by the police that is considered unfair (ie disproportionate and/or including excessive unlawful force) reduces motive-based trust and can ultimately increase levels of crime.Footnote 99 Thus, at a deeper level the public is protected from some increases in crime by a CC system that deters and disciplines officers who misuse their powers. This in turn requires a CC system with sufficient cultural reach to help forces and the IOPC identify DPS officers who overlook instances of excessive unlawful force or call in favours for friends etc; as discussed, the criminal law test limits this reach.

The constitutional axis is also important here because it promotes consideration of the consistency of the CC system with broader statutory requirements. For example, section 149(1) of the Equality Act 2010 provides that public authorities must ‘have due regard to the need to eliminate discrimination, harassment, victimisation’ and ‘foster good relations between persons who share a relevant protected characteristic and persons who do not share it’. However, HMICFRS reports have repeatedly pointed to unexplained ongoing disproportionality of stop and search and use of force against people who are racialised black and brown.Footnote 100 In line with this, the Home Affairs Committee in its Report ‘MacPherson 22 Years On’, concluded that it did ‘not believe that policing has taken seriously enough its responsibilities under the Equality Act 2010 in recent years’.Footnote 101 Selection of a test for use of force within the CC system which makes it harder to address, explain or tackle this ongoing disproportionality and institutional racism along all three accountability axes is something which policymakers would need to justify on extremely strong grounds.

Notwithstanding these observations, the concerns raised by police stakeholders regarding recruitment and retention of officers should not be lightly dismissed. Putting aside the many legitimate arguments regarding the origins and functions of policing, and operating on the paradigm of policing by consent,Footnote 102 the public is protected by officers who feel supported to carry out their difficult work, and for whom such support extends to high-quality lesson-learning which challenges institutional and personal bias in an environment that genuinely promotes honesty. However, as explored extensively above, the criminal law test actively advocated for by police stakeholders does not provide any of these things.

Conclusion

This paper has developed the Axes of Accountability Framework (the Framework) and applied it to the CC system in England and Wales. As noted in the Introduction, above, the CC system operates in the context of additional accountability bodies and processes, namely the HMICFRS, PCCs and the super-complaint system. The Framework can be applied (as here) at the relatively narrow level of the CC system (and issues within that). However, the results of such analysis can also be applied to these broader accountability infrastructures. Similarly, the Framework will assist in comparative study and will potentially be of importance as policing scholars internationally contend with the challenges to police accountability presented by rapidly changing technologies.

The discussion in Sections 3 and 4 has demonstrated the value of the Framework in allowing complex arguments concerning conceptions of policing and conflicting viewpoints (and evidence) on policing and police accountability to be disentangled and delineated along each axis. Simultaneously, by requiring a focus on the conduct, culture and constitutional aspects of accountability, it encourages balanced debate and requires policy choices to be clearly articulated. It thereby also ensures that the negative consequences of a choice in relation to one aspect of a larger police accountability infrastructure may be mitigated by changes in other parts of that structure. This clarity will also assist in how the impact of reforms is monitored.

Importantly, the Framework also permits an assessment of the implications of police stakeholder and other parties’ arguments regarding reforms to accountability processes. For example, in W80 the police stakeholders contended that the officer (W80) should not face misconduct proceedings because it had been accepted that he honestly believed the force he used was necessary. The Court of Appeal rejected this on the grounds that

The [claimant’s] submissions would prevent public scrutiny of the serious situation that arose in this case. The investigation by the IOPC is privately undertaken, whereas a misconduct hearing is conducted in public.Footnote 103

W80 involved the shooting of unarmed black man, Jermaine Baker. Officer W80 was briefed by Specialist Firearms Command (MO19) which the Casey Review found to harbour some of the ‘worst cultures, behaviours and practices in the Metropolitan Police’ and which it recommended should be disbanded.Footnote 104 Further the Report of the public inquiry into the shooting of Mr Baker stressed that – had it not been for his tragic death – the multiple ‘shortcomings in planning and execution’ of the operation which the inquiry identified ‘would not have come to light and the operation would have been hailed as an outstanding success by and for the MPS’.Footnote 105

On appeal by the Commissioner in W80 the Supreme Court noted

If the test is the criminal law test, then where, as here, it is accepted that the individual officer’s belief was genuine and honest, there would be no scrutiny through the disciplinary process of the reasonableness of mistakes by police officers.Footnote 106

It must be emphasised that in seeking the criminal law test police stakeholders are requesting lower levels of transparency and public scrutiny regarding use of force (and potentially fatal force) against citizens. Further, they have continued to argue for this test after its constitutional impact has been noted by the Supreme Court and Court of Appeal. This highlights the importance of policymakers, lawyers and judges taking account of and acting on the wealth of evidence over many decades (which Casey only highlighted) regarding police defensiveness at all levels in the face of allegations of misconduct, excessive force, unconscious bias etc. It also requires these eminent figures to remain vigilant regarding police stakeholders’ understanding of the appropriate boundaries of their autonomy across each of the axes.

For example, in W80 the police stakeholders contended that the COP Code of Ethics had sufficient legal status to overwrite the clear wording of the Regulations. Ultimately, however, all parties conceded that the COP ‘does not have any particular role or special authority in relation to the making of Regulations relating to “the conduct, efficiency and effectiveness of members of police forces and the maintenance of discipline”’.Footnote 107 Notwithstanding this, the COP has sought to extend the remit of its Outcomes Guidance beyond its statutory powers. While the statutory scope of the Guidance is limited to what happens once it is determined that misconduct proceedings are apt,Footnote 108 the Outcomes Guidance explicitly attempts to expand this by stating that it ‘may also be used to inform severity assessments of officer conduct more generally’Footnote 109 (emphasis added). Controversially, the Guidance suggests mitigation is appropriate if officers were provoked.Footnote 110 While Parliament may have permitted the COP to make such provisions regarding sanction, the invitation to take provocation into account in severity assessments across the CC system may materially impact the EFL in ways that are ultra vires the COP’s powers.

More subtle (but nonetheless important) is the status and quality of police expert evidence. It will be recalled that difficulties with the recruitment and retention of firearms offices is raised as a reason for preferring the criminal law test. In W80 the police expert asserted that the most common reason given by officers for not applying to be a firearms officer is ‘concerns about what would happen in the event they have to discharge their firearm in terms of the risk of being criminally prosecuted and/or dismissed’.Footnote 111 However this expert gave no evidence regarding how he reached this conclusion, so his methodology could not be scrutinised. Further, as noted above, there are many reasons pertaining to the ‘cultures, behaviours and practices’ in SO19 that may also have deterred officers from applying to join that unit, and those officers are unlikely to have been open about that to the expert in question.

These points combine to amplify a disquiet concerning the constitutional impact of the cynicism of police trainers and the apparent status of the NDM in court settings. Returning to W80, it was contended that officers had been trained to believe that the criminal law test applied and that consequently it would be unfair if the court found otherwise. In refuting that point, the Supreme Court nevertheless observed:

It will be possible that an officer’s training will be relevant to the trigger issue, namely whether the circumstances as the officer understood them to be rendered it reasonable or necessary for him to use force, or to the response issue, namely whether his response involved the use of a proportionate or reasonable amount of force to the threat that the officer believed he faced. This will be a matter to be decided having regard to the particular circumstances of a given case. Furthermore, the training an officer has received may have an important bearing on the decision whether his conduct constitutes misconduct or gross misconduct under the Conduct Regulations. As a result, the relevance of training is not necessarily limited to mitigation.Footnote 112 (emphasis added)

The discussion above noted that access to the courts regarding what amounts to unlawful force has been curtailed over the last 25 years.Footnote 113 It also highlighted the significant practical difference between the EFL (which represents the actual amount of force to which citizens may routinely be subject), and the technical boundaries to what amounts to unlawful force by officers. This is important because the focus of attention in a court setting is the balance of rights as between officers and citizens. The question concerns whether it was reasonable for a citizen to be treated in this way by an officer. Consequently, the rights of the citizen feature in evaluation of the surrounding circumstances. In contrast, under the current CC system, the EFL is considerably more officer-focused. The question is whether it was reasonable for the officer to behave in that way. On this basis the Supreme Court’s position – that police training can be authoritative concerning what amounts to proportionate force – tends towards giving police trainers a declarative role regarding the level of force that can be routinely used against citizens. It is contended that this should be resisted and that the Accountability Axis Framework developed here should be adopted broadly as a tool by which increasing levels of police autonomy can be delineated, and policy makers accordingly required to justify policy choices or lobbied to ensure effective accountability measures are put in place.