Introduction

Political scientists have long studied the effects of parties’ positions on their electoral success. Our approach integrates the spatial model of elections popularized by Downs (Reference Downs1957) into a policy salience framework. In the former, parties seek support by presenting issue positions to an electorate with a specified distribution of policy views (positions) along the relevant dimensions. In the latter, parties seek to alter the salience of issues to the electorate by setting ‘the terms of the debate’ in national election campaigns, emphasizing issue areas they see as electorally advantageous while downplaying other issue areas (Belanger & Meguid, Reference Belanger and Meguid2008; Petrocik, Reference Petrocik1996). We build on a mathematical simulation approach that has been extensively used to study parties’ positional strategies (e.g., Adams et al., Reference Adams, Merrill and Grofman2005) but modify this approach to project the expected effects of national shifts in voters’ issue attention. That is, we simulate how parties’ expected vote shares change as a function of plausible changes in issue saliencies. While this approach is relatively new, recent studies apply it to analyze the electoral success of far‐right parties in national elections (Kurella, Reference Kurella2019) and European Parliament elections (Vasilopoulou & Zur, Reference Vasilopoulou and Zur2022). We take a broader perspective to show how this approach can illuminate the electoral implications of changes in issue salience for all party families.

We recognize that the degree to which voters weight party positions on a particular dimension responds not only to the parties’ issue emphases during the campaign, but also to other influences including external events and conditions, the media's issue focus and the emotional energy that an issue (such as the economy, immigration, crime or climate change) generates. Nevertheless, parties devote considerable strategic resources to their efforts to direct citizens’ attention towards certain issue areas, and away from others. Our analysis measures the relation of issue salience to the vote shares of the various parties; in particular, we determine when an increase in the salience of a particular issue would advantage or disadvantage each party. Thus, our results can suggest when an increasing emphasis by a particular party would likely advantage that party, but the degree of that advantage depends on the extent of changes in issue salience that can be achieved by a party's efforts to alter its emphasis on the issue.

We illustrate our approach by analyzing British Election Study data from 2017 and 2019, which obtained respondents’ preferred positions (and perceived party positions) on dimensions relating to Left‐Right ideology, European integration and income redistribution. Our primary substantive finding is that plausible changes in the salience that voters attached to different positional issue dimensions could have altered the parties’ projected vote shares by several percentage points. We suggest explanations for why these implications might occur. Our analysis applied to the British elections suggest that incumbent parties (such as the Conservatives) would have been disadvantaged by increases in issue salience. On the other hand, an electorally weaker party (such as the Liberal Democrats) would likely have been advantaged and thus had incentives to emphasize its moderate Left‐Right position, in‐between the sharply leftist and rightist major parties. In fact, the governing Conservative Party had electoral incentives to downplay all positional issues and rely instead on its superior non‐policy image.

In varying degrees, these results and methodology are generalizable to other contexts, as shown by Kurella (Reference Kurella2019) and Vasilopoulou and Zur (Reference Vasilopoulou and Zur2022). Our conclusions also pertain to recent empirical research analyzing parties’ strategic choices over whether to campaign by emphasizing their non‐policy attributes versus their policy positions and priorities (Bjarnøe et al., Reference Bjarnøe, Adams and Boydstun2022).

Background

Two approaches that integrate Downs’ spatial model (Reference Downs1957) into the issue salience framework are those of Riker (Reference Riker1986) and Meguid (Reference Meguid2005). Riker raises the strategic possibility of ‘heresthetics’, whereby office‐seeking parties introduce new issue dimensions onto the political agenda, in an effort to win votes by splitting their opponents’ electoral coalition. Meguid (Reference Meguid2005) extends this idea, showing theoretically and empirically how established, mainstream parties react to newer niche parties that campaign on new issue dimensions. Mainstream parties may strategically choose to avoid engagement with the niche party's core issue, instead co‐opting the niche party's position or directly opposing the niche party's position, thereby raising the issue's salience to the wider electorate.

We take the Riker–Meguid framework as a starting point, positing that parties compete by influencing the salience or importance voters attach to the various positional dimensions of competition. However, we depart from this framework in two ways. First, we specify that parties’ issue positions along different positional dimensions are fixed, but that the salience of these dimensions to voters varies. Issue positions are assumed fixed, in the sense that parties may find it difficult to meaningfully change their policy images in the course of the election campaign. This assumption gibes with findings that voters do not substantially update their perceptions in response to the positions parties announce in their election manifestos (Adams et al., Reference Adams, Ezrow and Somer‐Topcu2011). Instead, voters respond to accumulated information from well before the election campaign, policies parties previously implemented when in government (Adams et al., Reference Adams, Bernardi and Wlezien2020) and parties’ histories of governing coalition membership (Fortunato & Stevenson, Reference Fortunato and Stevenson2013). Moreover, experimental research suggests that citizens often make negative character‐based inferences about parties that shift their policy positions, inferring either that the position change denotes lack of principles (Tomz & Van Houweling, Reference Tomz and Van Houweling2016), or is an insincere ploy designed to win votes (Fernandez‐Vazquez, Reference Fernandez‐Vazquez2019).

As indicated above, the degree to which voters weight party positions on a particular dimension responds to many stimuli. A large governing party may be well‐positioned to set the ‘terms of the debate’ for the election campaign due to the extensive news media coverage accorded to government officials’ policy statements and the government's concrete policy outputs. By contrast, small opposition parties might have less opportunity to influence voters’ issue attention. Nevertheless, all parties strive to specify the dominant issues during election campaigns (Baumann et al., Reference Baumann, Debus and Gross2021), although there is limited research on whether parties can significantly influence the public's issue attention beyond case studies on Canada (Soroka, Reference Soroka2002), Germany and Britain (Neundorf & Adams, Reference Neundorf and Adams2018) and the United States (Barbera et al., Reference Barbera, Casas, Nagler, Egan, Bonneau, Jost and Tucker2019). If changes in issue salience can meaningfully affect election outcomes, we can expect parties to design strategies that attempt to adjust their issue emphases. Basu (Reference Basu2019, p. 444) addresses a similar question and finds that, unlike major parties, minor parties ‘emphasize issues where their preferred policies may be unpopular but are distinctive’. Although several minor parties compete in the UK elections, the array of issues covered in the UK surveys is limited and we analyze the three parties (Conservatives, Labour and Liberal Democrats) most associated with the issues available. Thus, our results complement those of Basu.

Description of the issue‐salience model and the election survey data

The issue salience model

There is an extensive literature that applies simulation methods to study parties’ optimal positions (e.g., Adams et al., Reference Adams, Merrill and Grofman2005; Calvo & Murillo, Reference Calvo and Murillo2019). In this literature, researchers first estimate voters’ decision rules using survey data based on probabilistic functions of voter‐party proximity in the issue space, along with party‐specific coefficients that approximate parties’ non‐policy‐related attributes that influence voter evaluations independently of the parties’ policy positions. Non‐policy variables include valence attributes such as party leaders’ images for competence and integrity, their perceived degrees of empathy and charisma, along with other factors such as a party's organizational strength (e.g., Tavits, Reference Tavits2013) and its ability to mount an effective campaign (e.g., Stone, Reference Stone2017). Some parties enjoy superior valence images compared to others (Clark & Leiter, Reference Clark and Leiter2015; Stokes, Reference Stokes1963).

A conditional logit model is commonly employed in which the dependent variable is the reported vote choice by respondents (Adams et al., Reference Adams, Merrill and Grofman2005, chapter 10). Formally, in this model the probability that voter i votes for party j is given by

where the utility function for voter i voting for party j consists of a random component

![]() $\varepsilon $, plus a deterministic component denoted by

$\varepsilon $, plus a deterministic component denoted by

![]() ${U}_{ij} = u({x}_{i},{p}_{j})$, defined as the negative of the sum of the weighted distances between the voter's position xi and the party position pj over the focal policy dimensions, plus a party‐specific non‐measured component Vj, that represents valence and other non‐policy variables, together with unmeasured policy components that capture factors such as voters’ evaluations of the party's stances on additional relevant issue dimensions that were not surveyed in the British Election Study. In this utility function, the estimated coefficient (weight) of each voter‐party proximity term on a policy dimension is considered as the salience of that dimension, that is, the relative importance voters give to that policy issue (Adams et al., Reference Adams, Merrill and Grofman2005, pp. 18–19). For example, if the model includes three issue dimensions the measured component of this utility function is of the form:

${U}_{ij} = u({x}_{i},{p}_{j})$, defined as the negative of the sum of the weighted distances between the voter's position xi and the party position pj over the focal policy dimensions, plus a party‐specific non‐measured component Vj, that represents valence and other non‐policy variables, together with unmeasured policy components that capture factors such as voters’ evaluations of the party's stances on additional relevant issue dimensions that were not surveyed in the British Election Study. In this utility function, the estimated coefficient (weight) of each voter‐party proximity term on a policy dimension is considered as the salience of that dimension, that is, the relative importance voters give to that policy issue (Adams et al., Reference Adams, Merrill and Grofman2005, pp. 18–19). For example, if the model includes three issue dimensions the measured component of this utility function is of the form:

where the coefficients β 1, β 2, β 3, are the salience coefficients associated with the positional dimensions 1, 2 and 3, respectively.

Given the probability Pij of each survey respondent voting for each party, a party j’s expected vote share is defined as the mean over all respondents of the probabilities Pij.Footnote 1 In the last stage of this approach, researchers compute changes to each party's expected vote share under various counterfactual scenarios. To explain parties’ optimal policy positioning strategies, analysts compute the parties’ expected votes for alternative policy positions, in order to locate each party's vote‐maximizing position. For example, Adams et al. (Reference Adams, Merrill and Grofman2005) apply this approach to explain party and candidate positional strategies in American, British, French and Norwegian elections, while Zur (Reference Zur2021a, Reference Zur2021b) varies the values of parties’ non‐policy‐related attributes (Vj) to explain the electoral failures of centrist parties in Europe.

We diverge from the approach described above only in its last stage, where we vary the values of the salience coefficients β 1, β 2,… associated with the various positional dimensions, while all other variables (including parties’ policy positions and their non‐policy attributes Vj) are fixed at their observed levels. We label this the Issue Salience Model. The model specifies that voters evaluate (1) parties’ policy positions; (2) parties’ valence and other non‐policy attributes; and (3) additional, unmeasured considerations that render the voters’ decisions probabilistic, from the parties’ perspectives.

We apply the issue salience model to voting behaviour in recent UK general elections, analyzing surveys where respondents were asked to provide their policy positions (and their perceptions of party positions) on three salient dimensions. Specifically, we simulate changes to parties’ vote shares when each dimension's salience varies through a plausible range, from half to double the issue salience parameter we estimate for the 2017 or 2019 election.Footnote 2 For each policy dimension, at each point in the 50−200 per cent salience range, we recalculate parties’ expected vote shares.

Description of the data

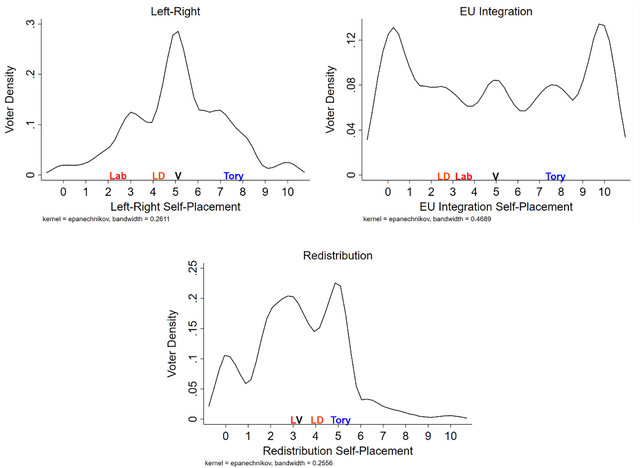

We analyze data from the British 2017 and 2019 General Election Study post‐election surveys (Fieldhouse et al., Reference Fieldhouse, Green, Evans, Schmitt, van der Eijk, Mellon and Prosser2018; Reference Fieldhouse, Green, Evans, Mellon, Prosser, de Geus and Bailey2021). These surveys include, in addition to respondents’ reported vote choices (our dependent variable), questions about respondents’ self‐placements and perceived party positions on three positional dimensions: the overarching Left‐Right continuum; income redistribution; and European integration.Footnote 3 We use these questions to compute the proximity between survey respondents’ and parties’ positions on these dimensions, defined as the difference between respondents’ self‐placements and parties’ mean perceived positions on each dimension.Footnote 4 As proximity between a voter and a party increases along a given dimension, so does the voter's likelihood of voting for that party. Our analysis includes only respondents who reported their vote choice in the focal election and who also answered the three self‐placement questions relating to Left‐Right ideology, European integration and income redistribution (1,451 respondents in 2017 and 2,208 in 2019). Figure 1 displays the distribution of respondents’ self‐placements on these dimensions, the median voter position on each dimension and the three main British parties’ mean perceived positions in 2019.

Figure 1. Voter self‐placement densities and mean perceived party locations: 2019 UK general election. Notes: Each panel displays kernel densities of survey respondents’ self‐placements on the focal dimension. Party labels denote the major parties’ mean perceived position, where LAB = Labour, LD = Liberal Democrats and Tory = Conservatives. V marks the Median Voter position on the dimension. Figure A1 in the Supporting Information displays the positions of the minor parties along with comparable figures for the 2017 election. [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

We note that the Liberal Democrats’ moderate perceived Left‐Right position was near the median voter and in‐between the sharply leftist Labour Party and the sharply right‐wing Conservatives, whereas Labour's pro‐income redistribution position was very much in line with British public opinion. The Conservatives, by contrast, were perceived as the major party farthest from the centre of public opinion on every positional dimension. The UK surveys report data for the Conservatives, Labour, the Liberal Democrats, the Greens, the Scottish National Party and the UK Independence Party (replaced by the Brexit Party in 2019). Although our calculations employed all six parties, we focus on the three largest parties in terms of vote share, the Conservatives, Labour and the Liberal Democrats. We report results for the smaller parties and added details of the calculations in the Supporting Information (see Table A1).

Our voting specification also includes party‐specific intercepts Vj, designed to capture factors that are not directly related to the three measured party‐voter policy position distances.Footnote 5 As discussed above, we label these estimates the parties’ non‐measured components, which include the parties’ valence images and other non‐policy variables, along with unmeasured policy components that systematically advantage some parties compared to others.Footnote 6 In our models, more negative intercepts denote that parties’ non‐measured components were increasingly weak relative to that of the Conservatives (the baseline party with intercept set at zero), which decrease these parties’ support beyond that expected based on measured positional issue proximities alone. We also note that these intercepts might include voters’ policy considerations that are not included in our models. Yet, the results shown below are consistent with the common knowledge about the valence images of the British parties and how they have changed over time (Zur, Reference Zur2021a).

Data analysis

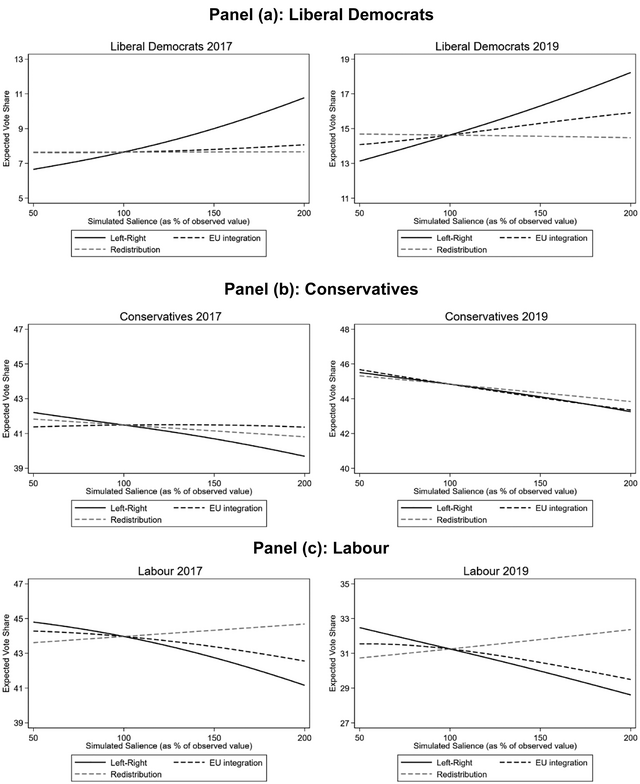

Applying the issue‐salience model, Figure 2 presents parties’ projected 2017 and 2019 vote shares along each policy dimension (the vertical axis), as the salience of each dimension is varied (the horizontal axis). These computations are based on the policy salience coefficients and party‐specific intercepts Vj, estimated in the conditional logit models that we present and discuss in detail in the Supporting Information (see Table A1). For example, the LHS panel in Figure 2A shows that the Liberal Democrats’ expected 2019 vote share increases from 13.1 to 18.2 per cent, a 5.1 per cent gain, when the salience of Left‐Right ideology is increased from 50 to 200 per cent of its estimated value. The party's expected vote also increases modestly as the salience of European integration increases across this range and remains essentially unchanged as the salience of redistribution is varied. The computations for 2017 reveal similar patterns, with projected Liberal Democratic projected vote gains of 4.1 per cent for increasing Left‐Right salience but with little net electoral effect from salience variations on European integration and income redistribution.

Figure 2. Expected vote share by party, as a function of simulated salience of positional issue dimensions. Notes: The panels display parties’ expected vote shares as the salience of the focal issue increases from 50 per cent of the observed value to 200 per cent, with all other coefficients fixed at their observed values.

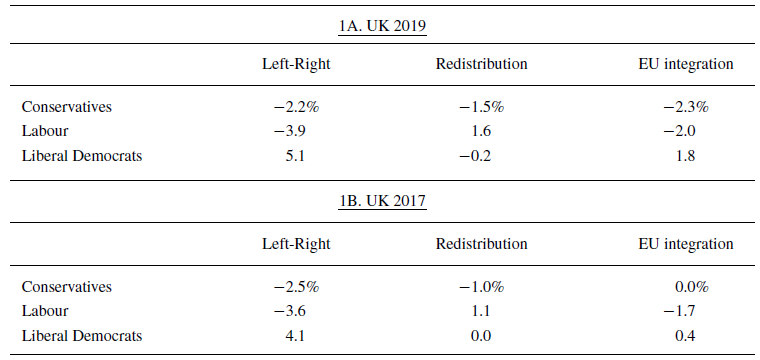

Table 1 summarizes the effects of policy salience on parties’ projected vote shares displayed in Figure 2 above. The table presents, for each of nine party‐issue pairs and each election, the total projected change in percent of expected party vote share, as the issue‐salience of the focal policy dimension is varied over the 50 to 200 per cent range. For instance, the value −2.2 per cent in the top LHS panel in Table 1A denotes that the Conservative Party's expected vote declines by 2.2 percentage points in the 2019 election as the salience of Left‐Right ideology is increased from 50 to 200 per cent of its observed value, with all other variables fixed at their observed levels.

Table 1. Salience‐projected vote share changes in the UK 2017 and 2019 elections

The estimates displayed in Table 1 and Figure 2 support the following conclusions. First, policy salience mattered in the 2017 and 2019 British elections: plausible variations in voters’ policy priorities could have shifted the parties’ projected vote shares by two to five percentage points, with all other factors (including the parties’ and voters’ issue positions and their non‐measured images) held constant. Thus, as far as party strategizing over their issue emphases can affect policy saliences, these efforts can have substantively important consequences. Indeed, the projected electoral effects of policy salience changes appear of comparable magnitude to the effects of plausible changes in parties’ perceived policy positions (see, e.g., Adams et al., Reference Adams, Merrill and Grofman2005).

Second, in both 2017 and 2019, the governing Conservative Party was projected to lose support with increases in the salience of each of the three positional dimensions (except zero change for European integration in 2017). Hence the valence‐advantaged Conservatives had electoral incentives to downplay all positional issue debates under study, in the hope that voters would evaluate parties primarily based on non‐policy considerations, where the Conservatives enjoyed a clear advantage (as we document in the Supporting Information; see section 2).

Third, in both 2017 and 2019, the valence‐disadvantaged Liberal Democrats would have benefitted from more salient positional debates concerning overall Left‐Right ideology, which might have accentuated the Liberal Democrats’ attractive Left‐Right position in between the sharply leftist Labour Party and the sharply right‐wing Conservatives. As displayed in Figure 2 and in Table 1, the Liberal Democrats could potentially have increased their expected vote share by four or five percentage points in both 2017 and 2019, had voters weighed ideological debates more heavily, and could have gained nearly two percentage points in 2019 had the salience of European integration increased. Moreover, there was no positional dimension in the British Election Study surveys where increased salience was projected to significantly harm the Liberal Democrats.

Fourth, the Labour Party, whose valence image was stronger than that of the Liberal Democrats but weaker than that of the Conservatives (at least in 2019), had electoral incentives to avoid emphasizing the overarching Left‐Right dimensionFootnote 7 and the European integration (Brexit) issue. The former reflects Labour's perceived shift far to the left under Jeremy Corbyn's leadership, away from the mainstream of public opinion.Footnote 8

Robustness checks: Control variables and simultaneous salience variations on two issues

As noted above (see footnote 6), we estimated alternative voting models that incorporated respondents’ sociodemographic characteristics including age, gender, education, political knowledge and political interest, together with these variables interacted with each party choice. These modifications yielded only minor changes in model fit and in the projected electoral effects of variations in the salience of policy dimensions. Table A1 in the appendix reports details of these computations, in addition to the results of alternative models that exclude either the Left‐Right or redistribution dimension, because the latter overlap. We show that our substantive conclusions are consistent even when we exclude these dimensions.

Next, we analyzed an alternative counterfactual scenario where we varied the salience of pairs of policy dimensions simultaneously; specifically where, as one dimension's salience was increased from 50 to 200 per cent of its estimated level, the salience of the second dimension was decreased from 200% to 50 per cent of its estimated level. This specification was intended to capture the possibility that citizens exhibit relatively fixed levels of overall attention, so that increased attention to one policy area entails diminished attention to another policy area. These computations, described in the Supporting Information (section 5), show that the projected vote share effects of varying the salience of two policy dimensions simultaneously but in opposite directions is (approximately) the difference between the effects of varying the salience of the two dimensions separately, that is, there appears to be little interactive effect on expected vote share, at least within the 50 to 200 per cent salience range that we analyzed.Footnote 9

Discussion and conclusion

In this research note, we discuss a recent modification of an old methodology. Building on the simulation method that has been used to study the electoral effects of parties’ positional strategies, we demonstrate how researchers can study parties’ issue‐emphasis strategies. Specifically, we argue that by varying the salience coefficients of proximity terms in multidimensional models of vote choice, we can shed light on parties’ incentives to emphasize or de‐emphasize some positional issues relative to others.

This methodology is illustrated with survey data from the British general elections of 2017 and 2019. Empirically, we reach three substantive conclusions. First, in both elections, the Liberal Democrats would have benefitted greatly – in terms of expected vote share – from increased salience of Left‐Right ideology, and to a lesser extent on European Union integration, whereas Labour and the Conservatives would have consistently suffered on these same two dimensions. We hypothesize that many centrist voters, who actually voted for Labour or the Conservatives, might have reconsidered their choices had they been more focused on these parties’ polarized positions on these two dimensions, and have been more willing to support the centrist Liberal Democrats (Nagel & Wlezien, Reference Nagel and Wlezien2010; Zur, Reference Zur2021a, Reference Zur2021b). We note the consistency of the observations above: we project that in both elections the Liberal Democrats would have benefitted substantially from voters’ increased attention to Left‐Right ideology and European Union integration, whereas Labour and the Conservatives would have consistently suffered from voters’ attention to these dimensions.

Second, we estimate that the Conservatives, who we estimate benefitted from significant non‐policy‐related advantages, were projected to lose support in response to voters’ increased attention to any positional dimension in either 2017 or 2019 (with the exception of European Union integration in 2017, where the projected effects were neutral). This illustrates how a party with significant non‐policy‐related appeal advantages is motivated to reduce voters’ emphases on positional policy dimensions, thereby magnifying the impact of the party's non‐policy‐related appeal.

Our empirical applications raise issues for future research. First, it would be informative to unpack the substantive content of the party‐specific intercepts we estimate, which we interpret as parties’ ‘valence’ images in addition to other nonpolicy considerations, as well as unmeasured policy effects. While we provide evidence in section 5 of the Supporting Information that these intercepts are related to parties’ valence image, more work needs to be done in this field. Next, the degree to which parties – by altering their emphasis on an issue – are capable of increasing or decreasing issue salience as that is perceived by voters needs to be analyzed (see, e.g., Neundorf & Adams, Reference Neundorf and Adams2018; Soroka, Reference Soroka2002). Finally, we could empirically analyze whether parties’ actual issue emphases in the 2017–19 British elections followed the emphasis strategies that our counterfactual simulations prescribe.

We believe that the issue salience model embodies a powerful tool to investigate a counterfactual, namely the expected electoral effects of greater or less salience of specific positional issue dimensions in particular elections. Moreover, given research that parties’ perceived positions are largely fixed by the time the election campaign begins, parties may more realistically use their campaign messaging to shift the salience of different positional issues, that is, change the ‘terms of the debate’, than to shift their perceived positions. We have illustrated a significant step toward studying this strategic issue in two recent British elections, obtaining consistent and interpretable results. This technique can be used to explore the effects of issue salience on electoral outcomes in many other polities or settings.

Acknowledgements

We thank the EJPR editors and three anonymous reviewers for the valuable suggestions and feedback. All remaining errors are ours.

Online Appendix

Additional supporting information may be found in the Online Appendix section at the end of the article: