Introduction

Arbitration is a dispute resolution mechanism wherein the parties involved submit their controversy to impartial arbitrators for a final and binding decision (Daughtrey Reference Daughtrey1985). With the growing number of international commercial transactions, arbitration has emerged as the main system for resolving commercial disputes due to its flexibility, confidentiality, and efficiency (Franck Reference Franck2000). However, observers cite growing threats to arbitration’s credibility, stemming from perceived increases in arbitrator misconduct (Franck Reference Franck2000, 11–15). In the most egregious situations, arbitrators may deliberately act unfairly to further their personal interests or to make illicit gains (Hausmaninger Reference Hausmaninger1990; Demeter Reference Demeter, Leaua and Flavius2016). These concerns have been enhanced by a string of high-profile criminal cases involving arbitrators (Nasrallah Reference Nasrallah2016; Pizarro Reference Pizarro2019; Walters Reference Walters2019; Vanar Reference Vanar2023). Consequently, the mechanisms designed to prevent such misconduct have received increased attention inside and outside the arbitration community.

Despite the varied approaches of different jurisdictions, the prevailing means of addressing arbitrator misconduct involve remedies against arbitral awards, such as setting aside or non-enforcement of an arbitral awardFootnote 1 and legal consequences towards arbitrators, such as removal from an arbitral proceeding and civil liability (Duan Reference Duan2015, 19). In addition, non-legal mechanisms, such as reputation, are also a strong incentive for arbitrators to adhere to ethical standards (Guzman Reference Guzman2000). As choices are mostly made on the basis of how an arbitrator is perceived, arbitrators are mindful of their reputation as it directly impacts their prestige, revenue, and future appointments (Moreira Reference Moreira2022a).

Those within the arbitral community have widely perceived these mechanisms as adequate for overseeing arbitrators’ behavior and ensuring arbitral neutrality (Chen Reference Chen2006; Bermann Reference Bermann2020, 229). By contrast, holding arbitrators criminally liable is considered a more challenging measure due to the extreme sensitivity of using criminal provisions to control arbitrators’ behavior. On the one hand, despite being private actors, arbitrators are afforded significant powers given their de facto judicial function (Cevc Reference Cevc2019, 406). Therefore, some jurisdictions have attempted to control their actions further (Nasrallah Reference Nasrallah2016). On the other hand, there is a risk that disgruntled parties or state actors might use criminal investigations to disrupt proceedings and unfairly punish arbitrators who issue unfavorable decisions (Club des Juristes Reference des Juristes2017; Kopic Reference Kopic2024; Korom Reference Korom2025).

The controversy surrounding this issue is particularly pronounced in China, which enacted a provision titled “Perversion of Law in Arbitration” enshrined in Article 399(A) of the Chinese Criminal Law (CCL). This provision, which criminally punishes an arbitrator who “intentionally makes a ruling against the facts or the law,” has resulted in heated debate among Chinese scholars and legal practitioners since its implementation in 2006. Critics have raised concerns about the potential for abuse and legislative overreach (Xu Reference Xu2006; Chen Reference Chen2006; Wei Reference Wei2008; Fan Reference Fan2009; Tan 2010; Han Reference Han2011). Conversely, proponents argue that this criminal provision is necessary given the judicial nature of arbitration and the importance of preventing arbitrator misconduct (Luo Reference Luo2009; Xu Reference Xu2009; Yang Reference Yang2010; Zhou and Yu Reference Zhou and Yu2011).

Despite the controversy, there is a dearth of empirical research on the criminalization of arbitrators (Lagarde Reference Lagarde2015, 798). Although some scholars have offered theoretical commentary on the application of criminal legislation to actions undertaken by arbitrators, these studies have been predominantly doctrinal and lacked an empirical examination of the concerns raised by using criminal law to control arbitrators (Arslan Reference Arslan2014; Dayton and Takahashi Reference Dayton and Takahashi2018; Hussein Reference Hussein2018; Filipová and Barková Reference Filipová, Barková, Malachta and Provazník2021). Similarly, in China, discussions around Article 399(A) have been primarily theoretical, lacking empirical research to understand whether the concerns raised by this provision were justified.

Given this research gap, the present study investigates the application of provisions aimed at criminalizing arbitrators in China. Drawing on twenty-seven cases where arbitrators were criminally prosecuted in China, it addresses two interrelated questions. First, it quantitatively identifies the extent to which arbitrators have been prosecuted in Mainland China and the characteristics of these cases. Second, it critically examines the validity of the concerns raised by the aforementioned criminal provision. Answering these questions is important as China is undertaking significant reforms to its arbitration legal framework.

In examining how criminal authorities and courts in Mainland China have deployed criminal penalties to sanction arbitrators, this study advances the literature on the regulatory dynamics of arbitration. Specifically, it illuminates the ongoing challenge faced by legal systems in balancing the prevention of arbitrator misconduct with the preservation of arbitrator independence and due process (Lagarde Reference Lagarde2015; Club des Juristes Reference des Juristes2017; Azzali Reference Azzali2019). Given that the liability of arbitrators remains an area of significant divergence across jurisdictions (Hausmaninger Reference Hausmaninger1990; Mullerat and Blanch Reference Mullerat and Blanch2007), an empirically grounded analysis of how criminal provisions are applied in practice provides valuable insight for both scholars and policymakers seeking to navigate this unharmonized landscape.

Moreover, this study contributes to broader debates on the regulation of arbitrators by interrogating the potential disconnect between the arbitral community’s stated regulatory preferences, particularly its resistance to external legal oversight expressed through legal liability (Bermann Reference Bermann2020; Moreira Reference Moreira2024), and the realities of legal intervention at the domestic level (Nasrallah Reference Nasrallah2016; Pizarro Reference Pizarro2019; Walters Reference Walters2019; Vanar Reference Vanar2023). Our findings hint at the notion that the community’s discourse often overlooks the specific socio-legal concerns that may justify legislative intervention within particular jurisdictions, even when such interventions may be fairly criticized as potential threats to arbitral autonomy. By presenting Mainland China as a case study, we illustrate how local institutional and cultural contexts can both challenge and refine widely held assumptions about arbitral regulation. While the distinctiveness of China’s arbitration system limits the direct transferability of policy lessons (Fan Reference Fan2013), it provides a unique context for testing the boundaries of existing theories and offers a fertile ground for exploring the practical implications of regulatory models that diverge from dominant international practices.

This article is organized as follows. The next section provides an overview of the regulatory preferences of the arbitral community, with particular attention to how arbitration discourse has emphasized the importance of shielding arbitrators from liability. The article then outlines the debates regarding the criminalization of arbitrators, both internationally and in China. Following this discussion, section three describes the article’s methods and data sources. The fourth section provides an analysis of the key characteristics of the cases where arbitrators were criminally prosecuted, visually represented through a series of tables and graphs. Subsequently, in the fifth section, the criminal patterns and motivations behind the actions that have resulted in convictions under the “perversion of law” crime are investigated. Finally, the concluding section posits that, despite certain disparities in how this provision has been applied in practice, an analysis of its application by Chinese courts indicates that the provision has not been abused to disrupt arbitral proceedings, nor does it represent legislative overreach in the Chinese context.

The Regulatory Preferences of the Arbitral Community

Studies on arbitrators’ demographics often portray them as a small, elite cadre of individuals drawn from the upper echelons of the legal profession (Dezalay and Garth Reference Dezalay and Garth1998; Rogers Reference Rogers2005; Grisel Reference Grisel2017). While much of the sociological literature focuses on international arbitration, domestic arbitrators often exhibit similar characteristics. In general, arbitrators form a tightly knit community of elite legal professionals, many of whom combine their roles as arbitrators with positions as senior lawyers, academics, or policymakers (Dezalay and Garth Reference Dezalay and Garth1998; Grisel Reference Grisel2017).

This elite status not only defines the composition of the arbitral community but also enables it to function as an epistemic community with significant influence over the legal frameworks governing arbitration (Kaufmann-Kohler Reference Kaufmann-Kohler2010; Strong Reference Strong2016). Historically, the arbitral community has played a central role in shaping arbitration into the default mechanism for resolving large commercial disputes worldwide. Originally a Western legal institution closely tied to free trade and the privatization of justice, arbitration has been successfully exported across jurisdictions, including those in the Global South, where it has been embraced as a flexible and efficient alternative to traditional litigation (Nariman Reference Nariman2004; Massoud Reference Massoud2014).

In this process, the arbitral community has championed and secured the adoption of legal frameworks that institutionalize key principles, including party autonomy, minimal judicial intervention, and the enforceability of arbitral awards on par with court judgments. These frameworks have been further complemented by the creation of several soft-law instruments that establish standards on issues such as conflicts of interest, evidence, and procedural rules (Kaufmann-Kohler Reference Kaufmann-Kohler2010). These norms frequently reflect the dominant understandings of the arbitral community, often crafted with the participation of its most elite members (Dezalay and Garth Reference Dezalay and Garth1998; Kaufmann-Kohler Reference Kaufmann-Kohler2010).

The regulatory framework applicable to arbitrators has also been shaped to align with the preferences of the arbitral community (Rogers Reference Rogers2014; Moreira Reference Moreira2024). Members of this community, along with arbitral institutions and organizations, have consistently resisted centralized forms of regulation, such as licensing requirements, mandatory educational qualifications, or other formal oversight mechanisms (Mourre Reference Mourre2013). Instead, they advocate for a model that prioritizes party autonomy, allowing parties to select arbitrators based on their own preferences (Rogers Reference Rogers2014). This approach diverges from the regulatory norms typically observed in the sociology of professions, where formalized entry requirements and disciplinary mechanisms are the norm (Moreira Reference Moreira2022b, 133). Beyond resisting centralized regulation, the arbitral community has argued that maintaining arbitral independence and flexibility requires shielding arbitrators from excessive legal liability (Mourre Reference Mourre2013). Specifically, the community has generally opposed the expansion of civil liability for arbitrators, citing concerns that such liability could undermine the perceived neutrality of arbitrators, deter qualified professionals from serving in arbitral roles, and disrupt the careful balance between party autonomy and procedural flexibility that defines the arbitral process (Moreira Reference Moreira2024). In this context, a lively academic debate has emerged regarding how the civil liability of arbitrators should be designed and conceptualized (Yu and Shore Reference Yu and Shore2003; Cevc Reference Cevc2019; Villarreal Martínez Reference Villarreal and Ramón2024). Nevertheless, the community continues to affirm that at least partial immunity from civil liability is a key principle for an effective and ‘safe’ arbitration seat (Chartered Institute of Arbitrators 2015; Salahuddin Reference Salahuddin2017, 572).

As will be seen in the following sections, these same ideas have also informed the arbitral community’s resistance to the use of criminal provisions to regulate arbitrators’ behavior. From a socio-legal perspective, this resistance performs a function of boundary maintenance (Gieryn Reference Gieryn1983). By insisting that professional reputation and soft law are sufficient to police misconduct, the arbitral community seeks to insulate a “private” sphere of justice from the “public” logic of the state (Dezalay and Garth Reference Dezalay and Garth1998). Functionally, this allows arbitration to develop freely to satisfy the needs of its users. Professionally, it offers the discursive underpinnings that allow the community to establish a system of de facto self-regulation. However, as discussed below, this stance creates tension between the community and states that assume a more centralized approach to the regulation of arbitrators (Stone Sweet and Grisel Reference Sweet2017).

The Ongoing International Debate Regarding the Criminalization of Arbitrators

While the community seeks to insulate itself from the public logic of the state, the state’s most coercive tool, criminal law, threatens to pierce that veil. At first glance, arbitration and criminal law occupy distinct realms that rarely intersect (Mourre Reference Mourre2006, 95). Criminal law is based on compulsory state law, whereas arbitration is a private method for resolving disputes in civil and commercial contexts (Mourre Reference Mourre2006, 95). However, the severe consequences of arbitrators’ misconduct have led some to argue that criminal law should be used to control arbitrators’ behavior within proceedings (Xu Reference Xu2009). Indeed, arbitrators frequently decide cases valued in the millions of US dollars and, given their quasi-judicial role, are entrusted with substantial legal powers akin to those of judges (Franck Reference Franck2000, 15–23).

The discussion regarding the need to control arbitrators through specifically designed criminal provisions has also been shaped by several high-profile cases of arbitrators being investigated for criminal behavior. For example, in 2018, in a highly controversial decision, three arbitrators were sentenced in absentia to three years’ imprisonment in Qatar regarding their role in a tribunal that issued an award against a relative of the Qatari royal family (Walters Reference Walters2019; Dymond et al. Reference Dymond, Chesney, Burton and Afifi2021). In 2019, a judge in Peru ordered preventive detention for 14 Peruvian arbitrators in connection with the widely publicized Odebrecht scandal and their supposed role in a scheme to defraud the Peruvian government through public contracts-related awards (Pizarro Reference Pizarro2019). More recently, well-known Spanish arbitrator Gonzalo Stampa was charged with “unqualified professional practice” due to his participation in the highly controversial Sulu case. He was subsequently sentenced to six months’ imprisonment and banned from practising as an arbitrator for a year (Reuters 2024).

The international arbitration community has, however, expressed strong opposition to the idea of using criminal law to control arbitrators’ behavior and described some of the changes to criminal codes to create specific rules targeting arbitrators as an attack on the arbitration community and an obstacle to a well-functioning system of dispute resolution (Nasrallah Reference Nasrallah2016). Furthermore, the international arbitration community has expressed scepticism towards some of the cases where arbitrators were charged with criminal conduct. In some instances, the community asserted that the alleged wrongdoings are typically “routine work” in the arbitration field and that the criminal proceedings emerged from a misunderstanding by authorities of the particularities of arbitral proceedings. For example, regarding the aforementioned Odebrecht and Stampa cases, some have claimed that the authorities mischaracterized perfectly acceptable practices such as the transfer of the arbitration venues, the determination of arbitration fees, and the engagement with disputing parties to decide on the applicable rules (Pizarro Reference Pizarro2019; Walters Reference Walters2019).

Beyond the adverse effects on individual arbitrators, the international arbitration community has argued that the criminalization of arbitrators poses a significant threat to the independence of arbitral proceedings as a whole. According to many in the community, arbitrators who fear potential criminal charges may refrain from making decisions solely based on their expertise (Nasrallah Reference Nasrallah2016). Instead, they may choose to take a more cautious approach, which can result in less robust and independent decision-making (Dayton and Takahashi Reference Dayton and Takahashi2018). In addition, some worry that the criminalization of arbitrators can be manipulated as a tool to advance the interests of specific parties, especially for political reasons. For instance, in the aforementioned Qatar case, some legal practitioners have conjectured that the verdict on arbitrators may have been influenced by the plaintiff’s association with the Al Thani family, the ruling family of Qatar (Bilbow Reference Bilbow2018). In Stampa’s case, some saw the use of criminal charges against this arbitrator as a mechanism for Malaysia to strengthen its position in setting aside the final arbitral award related to its territorial disputes with the heirs of the Sultan of Sulu (Vanar Reference Vanar2023).

Finally, the arbitral community has argued that the creation of criminal provisions targeting arbitrators may discourage qualified individuals from serving as arbitrators in a particular jurisdiction, thereby jeopardizing the jurisdiction’s status as an international arbitration centre. For instance, following the UAE’s enactment of a broadly worded provision criminalizing a “lack of neutrality,” numerous arbitrators opted to resign or decline appointments, and some tribunals chose to change the arbitral seat to outside the UAE (Dayton and Takahashi Reference Dayton and Takahashi2018, 34–35). Despite its repeal, this provision had a long-term impact on the UAE’s perception as an arbitration venue (Dayton and Takahashi Reference Dayton and Takahashi2018, 35).

It is worth noting that, despite the resistance of the arbitral community, a growing regulatory trend worldwide exists to change this approach. This is primarily driven by international anti-corruption efforts, particularly through the adoption of the Additional Protocol to the Criminal Law Convention on Corruption (ETS 191), which requires member states to establish criminal provisions regarding the bribery of arbitrators under their domestic legislation (Council of Europe 2003).

Despite these efforts, most jurisdictions still choose not to implement criminal provisions specifically targeting arbitrators. In jurisdictions that do have such provisions, these generally merely mention arbitrators alongside other individuals holding similar positions, such as judges or jurors, and mostly relate to the criminal consequences of accepting bribes when acting in those functions (Moreira Reference Moreira2024, 155–56). This is the case in jurisdictions such as Norway, France, and Spain. Some jurisdictions, including Germany, Slovakia, and Argentina, have gone further by enacting provisions that allow for the prosecution of arbitrators who misapply the law to favor a party. Nevertheless, it is important to note that these provisions are rarely enforced in practice, and instances of actual criminal prosecution of arbitrators remain exceedingly rare (Mullerat and Blanch Reference Mullerat and Blanch2007, 105; Born Reference Born2021).

Despite the rarity of prosecution, the application of criminal law in arbitration represents one of the most sensitive intersections between state power and the autonomous legal order of arbitration. The risk of criminal prosecution, even if often theoretical, represents an affront to the community’s logic of autonomy, where misconduct is traditionally corrected through arbitration-specific mechanisms such as annulment and reputational sanctions (Rogers Reference Rogers2014). As discussed, in most places, the arbitral community relies on its epistemic ability to construct a self-regulating sphere. However, as will be seen in the case of China, this dynamic shifts significantly under a different regulatory philosophy governing a profession with unique characteristics.

China’s Regulatory Approach to Criminalizing Arbitrators and the Criticism Endured

Mainland China’s arbitration framework incorporates many of the core principles common to transnational arbitration, including adherence to party autonomy and the finality of arbitral awards (Fan Reference Fan2013; Sun and Willems Reference Sun and Willems2015). However, the system also retains distinctive structural characteristics that diverge significantly from international norms. Notably, China’s framework generally precludes parties from settling domestic disputes outside Mainland China and does not recognize ad hoc arbitration (Fan Reference Fan2020). Instead, parties are effectively required to select one of the country’s authorized arbitral institutions (Gu Reference Gu2017). These commissions, historically linked to local governments, function as quasi-governmental entities, creating an arbitration ecosystem with a significantly higher degree of state influence than is found in most other jurisdictions (Tao Reference Tao2012, 811–12; Prusinowska Reference Prusinowska2017, 45).

Despite these structural constraints, arbitration is pervasive in Mainland China, extending far beyond the high-value commercial disputes that dominate the field elsewhere. Unlike jurisdictions where arbitration is the preserve of elite practitioners in major financial capitals (Dezalay and Garth Reference Dezalay and Garth1998), Chinese arbitration is utilized extensively throughout the country, including in less developed regions (Gu Reference Gu2017). As of 2024, there are 282 arbitral institutions operating across Mainland China, handling approximately 600,000 cases annually (CIETAC 2025). This sheer volume stands in stark contrast to the consolidated markets and lower caseloads of other major jurisdictions.

China’s approach to regulating arbitrator misconduct is equally distinct. While most jurisdictions lack formal regulatory bodies dedicated to arbitrator oversight, China’s framework mandates the existence of a China Arbitration Association, a public body with the authority to oversee commissions and discipline arbitrators.Footnote 2 In recent years, steps have been taken to move towards the formal establishment and empowerment of this regulatory body,Footnote 3 as part of a wider effort to improve the credibility of arbitration (General Offices 2018). This centralized approach has been reinforced by recent reforms to the Arbitration Law, which task the Ministry of Justice and local justice departments with the administrative supervision of arbitration at national and regional levels.Footnote 4

This regulatory divergence is rooted in the unique sociology of China’s arbitral ecosystem. A stark contrast exists between the global arbitral order and China’s domestic reality. Existing literature characterizes the global epistemic community as a high-trust “club culture,” where reputational sanctions effectively police misconduct (Dezalay and Garth Reference Dezalay and Garth1998; Ginsburg Reference Ginsburg2003). However, this model relies on a cohesive social network that is largely absent from China’s vast and fragmented market. While China has successfully institutionalized arbitration as a flexible, commercially oriented tool, it has done so by retaining centralized state control, thereby affording significantly less party autonomy than is typical in other jurisdictions (Fan Reference Fan2013).

Taking this regulatory control a step further, China stands out for its willingness to utilize criminal law to police arbitration. This became particularly visible in 2006, when the high-profile investigation of Wang Shengchang, then secretary of CIETAC, brought international attention to the criminal liability of arbitrators in China (Wu Reference Wu2007). That same year, China formally introduced Article 399(A) into the Criminal Code, establishing the specific offence of “perversion of law in arbitration.” This provision criminalizes intentionally rendering wrongful decisions in the course of arbitration, reflecting an intention to directly use criminal law to police arbitrator conduct.

Although this provision has not garnered significant attention from the international arbitration community, it has sparked considerable debate within China’s arbitration circles, mirroring the international discourse on the subject. At the time of its passage, the provision was criticized for being vague, and thus potentially allowing for prosecutorial overreach. Furthermore, some argued that existing general criminal provisions already covered such misconduct, making this new provision an unnecessary addition to the Chinese criminal system.

Concerns Regarding Potential Abuse

According to Article 399(A) of the CCL, “Whoever, in performing his duty of arbitration in accordance with the law, intentionally makes a ruling against the facts or the law, if the circumstances are serious, shall be sentenced to fixed-term imprisonment of not more than 3 years or short-term custody. If the circumstances are especially serious, the offender shall be sentenced to fixed-term imprisonment of not less than 3 years but not more than 7 years.”Footnote 5

Chinese legal scholars have criticized the broad language of this provision for providing little guidance on what behaviors can trigger the application of this norm. As per the dominant legal analysis, the first challenge lies in interpreting the scope of “whoever, in performing his duty of arbitration” (Xu Reference Xu2006). The absence of explicit limitations may imply a potentially broader application to other personnel working in arbitration commissions beyond the arbitrators themselves, such as directors, secretaries-general, and secretariats (Duan Reference Duan2015). Some have argued that this lack of clarity may affect the behavior of arbitration personnel and disrupt the smooth functioning of arbitration (Chen Reference Chen2006).

Another significant challenge lies in the meaning of the phrase “违背事实和法律,” which has been described as unclear and open to multiple interpretations (Chen Reference Chen2006). In particular, some Chinese legal scholars have criticized the usage of the conjunction “和,” which would imply that the offence arises only when both conditions, “goes against the facts” and “goes against the law” are satisfied, making it unclear whether the provision would apply when only one condition is fulfilled (Fan Reference Fan2009). In addition, the interpretation of the concept of “law” (法律) in this particular context has sparked controversy, leading to discussions on whether the discretionary application of legal principles and conventions or the incorrect application of foreign laws could trigger the Article (Kurlekar Reference Kurlekar2015).

Consequently, challenges have arisen concerning the accurate definition of “perversion of law,” providing some malicious parties with an opportunity to misuse this offence and use the criminal system to pressure arbitrators into deciding according to their interests (Han Reference Han2011). Some argue that the absence of clear standards for the application of these norms grants substantial discretionary power to the court and the prosecutor in this realm. It is, therefore, unsurprising that, prior to the promulgation of this provision, some influential Chinese arbitrators have expressed apprehensions about its potential misuse, primarily emphasizing its overly vague nature (Chen Reference Chen2006; Xu Reference Xu2006).

Concerns about Legislative Excess

Chinese legal scholars have also raised concerns that the promulgation of this provision might constitute “legislative excess,” given that arbitrator misconduct can already be addressed under the existing Chinese arbitral framework. First, some argue that ethical constraints and market pressures already effectively regulate arbitrators’ conduct as their reputation within the arbitration industry is crucial, making the need for criminal legislation questionable (Tan Reference Tan2010). Second, critics highlight that existing private law and disciplinary remedies, such as contractual and tort liability or removal from arbitration panels, are sufficient to control misconduct in this area (Chen Reference Chen2006). Lastly, it has been argued that existing criminal provisions adequately address arbitrators’ misconduct as the crime of “perversion of law” frequently overlaps with other criminal charges (Song Reference Song2007).

Regarding this last point, it is important to note that in the context of CCL, “perversion of law” is not the only criminal provision that may apply to arbitrators. Arbitrators can be prosecuted for general criminal offences related to their official duties. These offences fall under the categories of “Graft and Bribery” (Chapter VIII) and “Dereliction of Duty” (Chapter IX) in the CCL. Despite the lack of explicit inclusion of “arbitrators” in these provisions and uncertainty regarding whether arbitrators are classified as “public officials,” in practice, arbitrators may be charged with these crimes, as some courts have held them to be “public functionaries.” In addition, arbitrators can be implicated in crimes such as “bribery of non-state personnel” and “misappropriation of funds” under articles 163 and 272 of the CCL, which have also been used to prosecute arbitrators’ criminal behavior.

Therefore, the central question that arises is whether the concerns raised by the Chinese arbitration community at the time of the passing of this provision are valid. To address this question, it is essential to explore the practical circumstances of how arbitrators face criminalization in China.

Research Methods

This study retrieved cases concerning arbitrators’ criminal behavior from online databases and media reports. The judgments were obtained from the two most widely used legal databases in Mainland China: China Judgment Online (CJO) and Wolters Kluwer. CJO is the governmental platform for the nationwide archival of legal decisions. While the lack of completeness of CJO as a platform has been noted, courts are mandated to publish all judgments on this website, except in special circumstances such as those involving state secrets or juvenile delinquency.Footnote 6 In addition, this study employs the Wolters Kluwer database, an independent publisher’s collection of Chinese case law, as a supplementary resource. The Wolters Kluwer database provides coverage of cases that are sometimes unavailable on CJO.

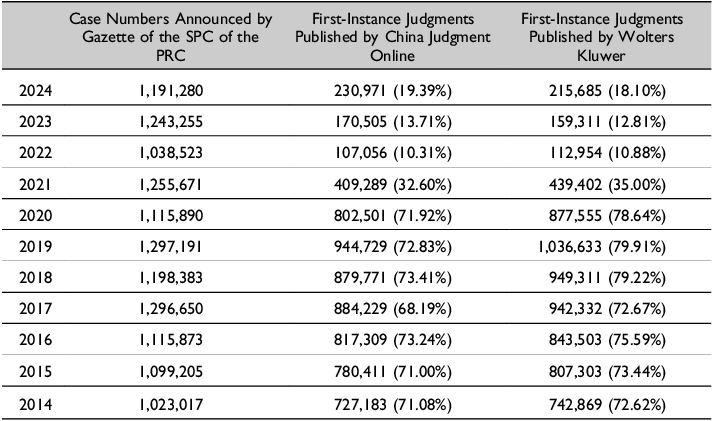

To evaluate the comprehensiveness of these databases, Table 1 displays the number of first-instance judgments collected by CJO and Wolters Kluwer compared to the total number of criminal cases (first-instance trials concluded) announced in the Gazette of the SPC over an eleven-year period. The analysis reveals that these databases have accumulated a significant proportion of adjudicated cases during the specified period, with a disclosure rate exceeding 60 percent for the majority of the years examined.

Table 1. Number and Proportion of Criminal Cases (First instance concluded) Collected from Online Databases

Retrieval date: November 28, 2025

The research method involved searching for the keywords “arbitration” and “arbitrators” in conjunction with all possible criminal charges that might apply to arbitrators who infringe on their professional duties. Potential criminal charges against arbitrators include offences under Chapters VIII (Graft and Bribery) and IX (Dereliction of Duty) of the CCL. Under Chapter VIII, arbitrators may face charges of “graft” (贪污罪), “bribery” (受贿罪), “introducing bribes” (介绍贿赂罪), “misappropriation of public funds” (挪用公款罪), “possession of a large amount of property of uncertain origin” (巨额财产来源不明罪), “embezzlement of state-owned assets” (私分国有资产罪), and “offering bribes” (行贿罪). Charges under Chapter IX include offences such as “perversion of law in arbitration” (枉法仲裁罪), “abuse of power” (滥用职权罪), and “neglect of duties” (玩忽职守罪). In addition, arbitrators can be implicated in crimes such as “bribery of non-state personnel” (非国家工作人员受贿罪) and “misappropriation of funds” (挪用资金罪) under Chapter III of the category of crimes “Disrupting the Socialist Market Economy Order.”

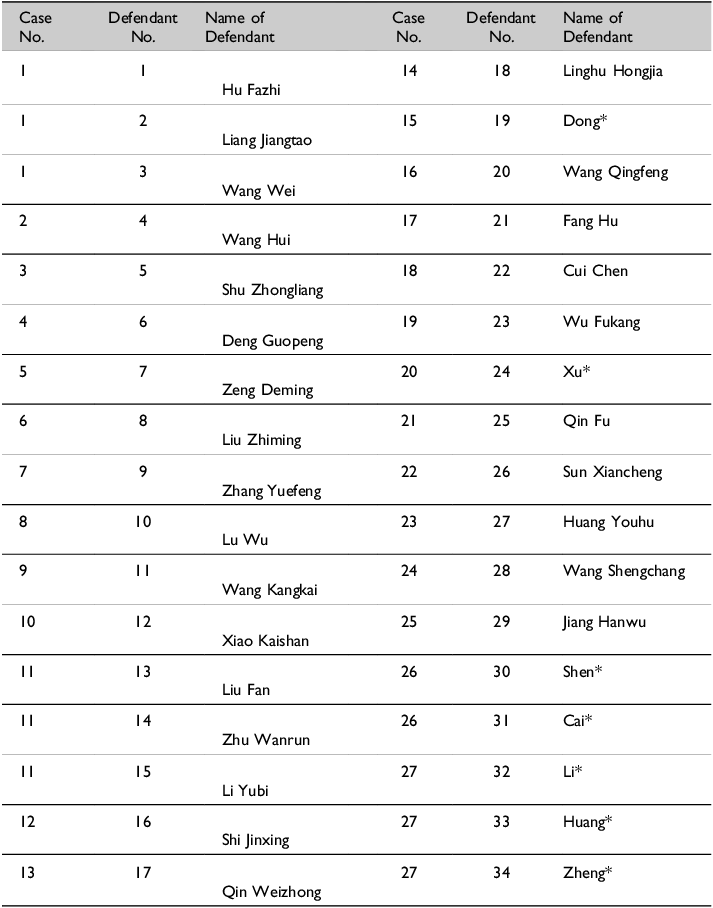

In addition, news reports were obtained through searches on Google.com, Baidu.com, WeChat, Tencent, Sina, and CCTV using keywords such as “perversion of law in arbitration,” “corruption and bribery in China,” “arbitrators,” “arrest,” and “criminal liability.” From these media reports, an additional four cases (cases 24–27) involving seven defendants (defendants 28–34) were included in our sample. Ultimately, twenty-seven criminal cases involving thirty-four defendants were selected for this research, including two cases prior to 2006, the year when the provision on perversion of law in arbitration was enacted, and twenty-five cases from 2006 until the end of 2023. For clarity, these cases are numbered throughout the study, as shown in Table 2 below.

Table 2. Numbering of Cases and Defendants

Note : Information for cases 1 to 23 is sourced from online databases, whereas cases 24 to 27 are derived from news reports. For detailed case information, please refer to Appendix 1

Results

Overall patterns

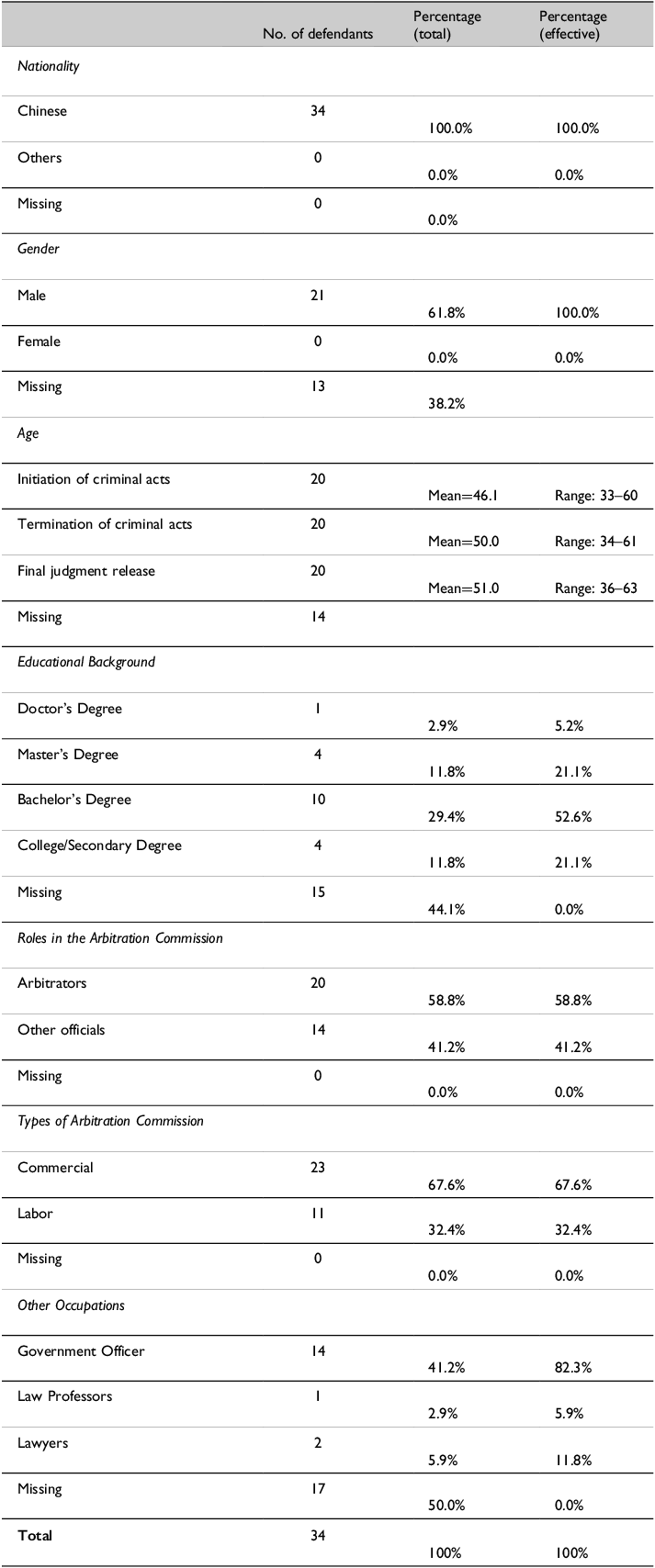

To assess the extent to which arbitrators are subject to criminal prosecution in China, Table 3 presents a descriptive analysis of the characteristics of the thirty-four defendants. The analysis includes information on gender, age, nationality, educational background, roles within the arbitration commission, and the primary occupations of the defendants.

Table 3. Identity Characteristics of Defendant Arbitrators

As shown in Table 3, all defendants were male (100 percent of non‑missing entries). This finding can be explained in two ways. First, it reflects the lack of gender diversity within the Chinese arbitration field. International arbitration has long been recognized as male-dominated, with approximately 26.1 percent female representation, according to the latest ICCA report (Greenwood and Baker Reference Greenwood and Mark Baker2012; International Council for Commercial Arbitration 2022, 4). Although official statistics on gender diversity in Chinese arbitration institutions are unavailable, it is generally accepted that arbitration in China is similarly male-dominated (Prusinowska Reference Prusinowska, Shahla, Balcerzak, Colombo and Karton2022). Second, the finding may suggest a potential correlation between male arbitrators and involvement in corruption-related crimes. Research indicates that males may be more inclined to commit duty-related offences. For instance, in China, studies have found that female prefecture leaders were up to 81 percent less likely to experience corruption-related arrests than their male counterparts (Decarolis et al. Reference Decarolis, Fisman, Pinotti, Vannutelli and Wang2023, 558), and only 9 percent of cases in the Corruption Conviction Databank involved women accepting bribes (Aidt, Hillman, and Liu Reference Aidt, Hillman and Liu2020, 4).

The table reveals that all defendants were exclusively Chinese (100 percent), alleviating concerns that this provision could be used to prosecute foreign arbitrators operating in China (Xu Reference Xu2006). The age distribution reveals that defendants were middle-aged, with an average age of 46.1 at the initiation of criminal acts, 50.0 at the termination of criminal acts, and 51.0 at the time of the final judgment release. In addition, among defendants with reported education, the vast majority held a bachelor’s degree or higher (78.9 percent), a finding in line with the general notion that arbitrators are usually well-established figures within the legal field and almost always possess tertiary education (Moreira Reference Moreira2022b). Furthermore, among defendants with reported occupation, most combined the role of arbitrator with that of government officials (82.3 percent), with only a small number acting as law professors or lawyers. It is worth noting that in Mainland China, contrary to most other jurisdictions, it is common for government officials to sit in proceedings as arbitrators.

Regarding roles in the arbitration commission, most defendants were prosecuted for acts undertaken as arbitrators (58.8 percent), whereas others were prosecuted for actions taken in their official capacities within the arbitration commission, such as directors, secretary general, or other official positions. The majority of defendants operated in commercial arbitration commissions (67.6 percent), with the remaining defendants acting within labor arbitration commissions (32.4 percent). It is worth noting that in China, labor arbitration has a more public-law nature and is overseen by a centralized government department.Footnote 7 By contrast, commercial arbitration is characterized by its private nature, with a greater emphasis on party autonomy and limited government interference.Footnote 8

Figure 1 presents descriptive statistics regarding the provincial distribution of the criminal locations where the criminal conduct occurred, as reported in the judgments. The criminal locations span thirteen provinces and autonomous regions in Mainland China. Specifically, Zhejiang and Jiangsu emerge as central areas, linked to four cases each. Gansu and Shandong closely follow, with three cases each. Other provinces, such as Yunnan, Hainan, Hebei, and Anhui, each have two instances, whereas Beijing, Fujian, Henan, Guangdong, and Shanxi each have one instance.

Figure 1. Provincial Distribution of Criminal Locations. Data were visualized using Datawrapper. An interactive version is available at: https://www.datawrapper.de/_/cPbaw/.

The distribution of criminal locations exhibits a wide geographical reach. However, the criminal cases are predominantly concentrated in the Mainland coastal provinces such as Zhejiang, Jiangsu, Shandong, Hebei, Fujian, Guangdong, and Hainan. These provinces are relatively more economically developed, ranking among the top in terms of GDP (People’s Daily Overseas Edition Reference Daily Overseas Edition2023).

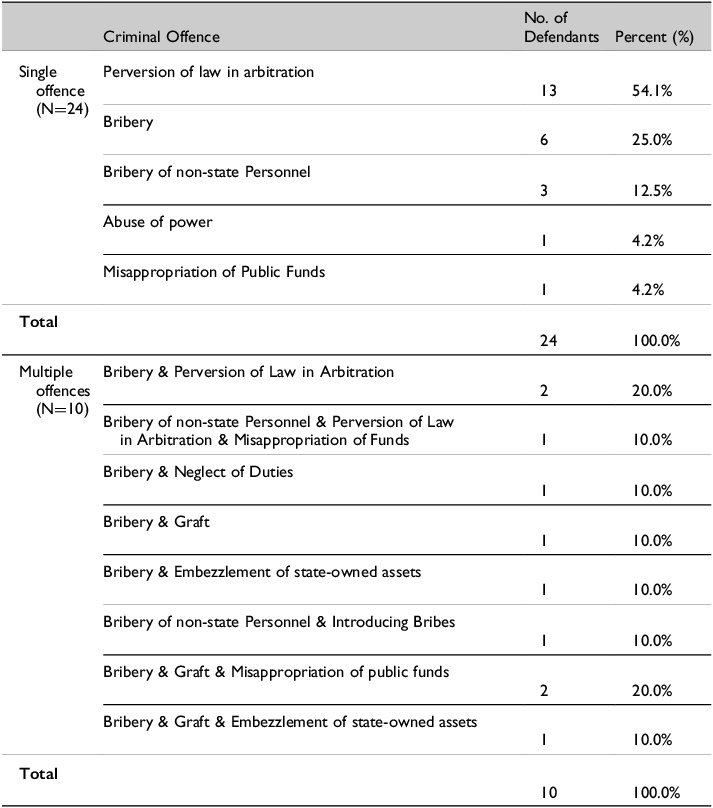

Table 4 provides a summary of the criminal offences underlying the convictions of the 34 defendants. The majority of defendants were convicted of a single offence. Among the twenty-four defendants convicted of a single charge, thirteen individuals (54.1 percent) were found guilty of the crime of “perversion of law in arbitration.” In addition, six defendants (25 percent) were convicted of “bribery,” whereas three defendants (12.5 percent) were found guilty of the crime of “bribery of non-state personnel.” Instances of “abuse of power” and “misappropriation of public funds” each led to the conviction of one arbitrator. Notably, 10 defendants faced multiple charges, all related to bribery or the bribery of non-state personnel in conjunction with another criminal offence.

Table 4. Criminal Offences Against Defendants

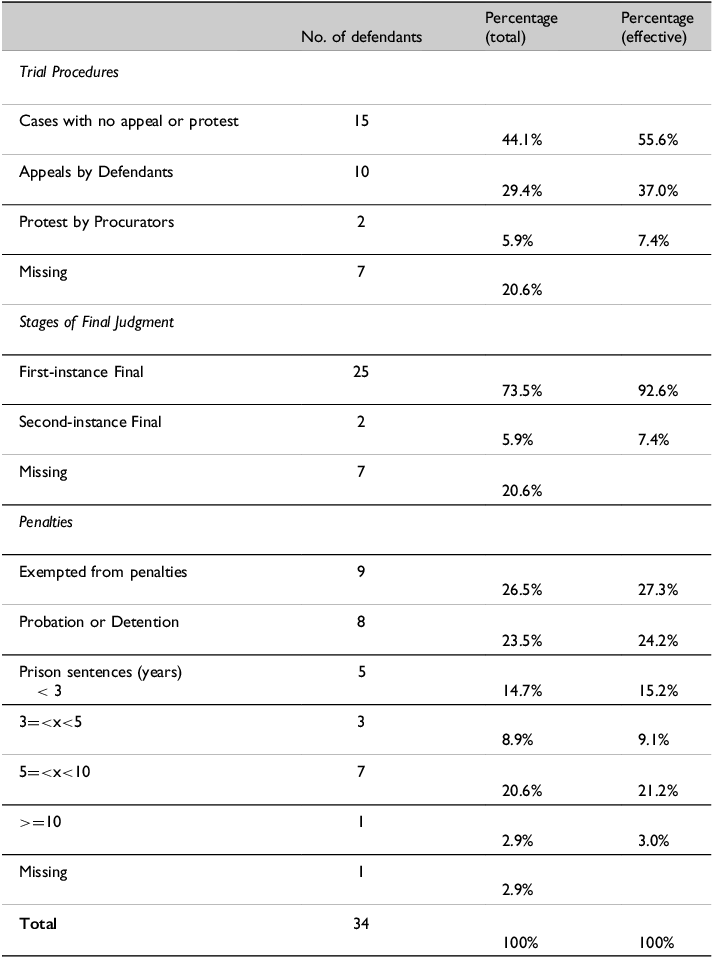

Table 5 provides an overview of the legal procedures and penalties applied to the thirty-four defendants in the sample. Notably, 37.0 percent of the defendants chose to challenge the initial decision and filed an appeal. However, prosecutors themselves appealed the first-instance judgments for two defendants, which accounts for 7.4 percent of the cases. It is important to highlight that only two judgments were revised at the second-instance level, yet these revisions primarily focused on changes in the legal qualification of the offence or the imposed punishment rather than altering the verdict of guilt or innocence. It is worth noting that in China, “not-guilty” verdicts are extremely rare, with a mere 0.05 percent occurrence rate among all valid judgments pertaining to defendants accused of crimes under Chapters VIII (Graft and Bribery) and IX (Dereliction of Duty) (SPC 2022; Liang and Hu Reference Liang and Hu2023).

Table 5. Legal Procedures and Penalties given to the Defendants

To illustrate the features of the revised verdicts, this article examines two specific cases. In Case 1, the court of first instance initially issued identical rulings for the three defendants, exempting them from criminal punishment due to the relatively minor nature of their offences. The People’s Procuratorate appealed the verdicts for two defendants, arguing that their substantial involvement in the criminal act did not meet the conditions for exemption from punishment. The second-instance court upheld the appeal for one of the defendants, sentencing him to two years of suspended imprisonment. In Case 3, the Prosecutor’s Office initially charged the arbitrator with bribery, a qualification accepted by the first-instance court. However, upon the defendant’s appeal, the second-instance court re-evaluated the case and convicted the defendant of “perversion of law in arbitration,” considering this to be the more appropriate criminal qualification given the amounts at stake.

In terms of penalties, 27.3 percent of the defendants were exempted from any criminal penalties, a rate significantly higher than the 2.8 percent exemption rate for all defendants charged with crimes under Chapters VIII and IX of the Criminal Law of the People’s Republic of China (CCL) (SPC 2022). Furthermore, only one defendant (3.0 percent of the sample) received a sentence of more than 10 years in prison.

“Perversion of Law in Arbitration”: Patterns and Motivations

As noted above, the open-ended text of Article 399(A) has sparked criticism from the Chinese arbitration community regarding the broad language used by the legislator. However, by examining the cases where this provision has been used to prosecute arbitrators, it is possible to identify a small number of recurring patterns of behavior that led to convictions under this provision.

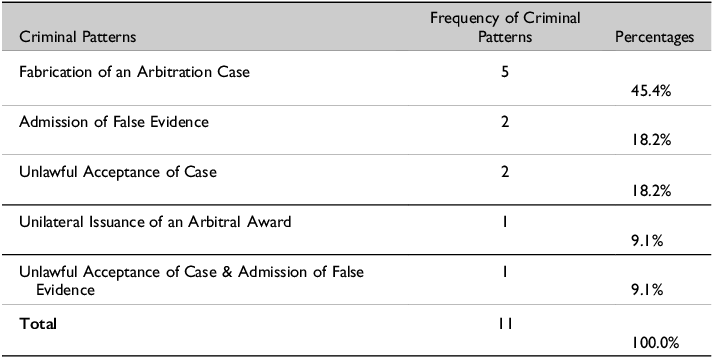

In this article’s analysis of twenty-seven cases where arbitrators were criminally prosecuted in Mainland China, defendants were found guilty under Article 399(A) in eleven cases involving sixteen defendants. By scrutinizing the details of these cases, they can be categorized into four distinct behavioral patterns: i) fabrication of arbitration cases, ii) admission of false evidence, iii) unlawful acceptance of cases, and iv) unilateral issuance of arbitral awards. As depicted in Table 6, the most prevalent pattern is “fabrication of arbitration cases” (45.4 percent). In addition, two other observed patterns include “admission of false evidence” (18.2 percent) and “unlawful acceptance of cases” (18.2 percent). One case pertained to the “unilateral issuance of an arbitration award” (9.1 percent). Furthermore, a single case, case 6, involved behaviors encompassing both “admission of false evidence” and “unlawful acceptance of cases” (9.1 percent).

Table 6. Criminal Patterns of “Perversion of Law” Cases

While these patterns reflect diverse types of misconduct, an analysis reveals a common thread: corruption-like intent or a close relationship between the arbitrator and the parties often served as the primary motivator behind the arbitrator’s actions. In almost all cases, the arbitrators’ behavior consistently involved elements of personal gain—such as monetary bribes (cases 3, 6, 16, 17, 23, 26), small gifts and other minor advantages (cases 1, 2, 4, and 23), or the cultivation of personal relationships (cases 1 and 5)—which were significant factors in their convictions.

Fabrication of Arbitration Cases

The phrase “Fabrication of arbitration cases” refers to situations where plaintiffs use arbitration as a tool to pursue goals other than those claimed in the proceedings (Maher Reference Maher1998; Hiber and Pavić Reference Hiber and Pavić2008).

The analysis reveals a pattern linked to labor arbitration commissions, where parties involved in what is essentially a commercial dispute fabricate evidence and submit applications to a labor arbitration committee. This manoeuvre is driven by the prioritization of employee salaries in bankruptcy proceedings, as stipulated in Article 113 of the Enterprise Bankruptcy Law of the People’s Republic of China. By establishing a false “employment relationship” through labor arbitration awards, parties can increase their probability of recovering money following bankruptcy proceedings.

Case 1 illustrates this type of criminal conduct. In this instance, three defendants were convicted of such behavior. The case originated from a commercial dispute between a gas company and a creditor named Yang. Upon learning that the gas company was facing bankruptcy and would be merged, the creditor sought to exercise his creditor’s rights through labor arbitration, as salary claims are often prioritized to protect employees. The creditor falsely claimed that the gas company owed salaries to twenty-six employees, using the ID cards of friends and acquaintances and dividing the debt into multiple parts. With the assistance of two arbitrators, as well as the vice president of the labor commission, the creditor successfully obtained 26 arbitration awards totalling RMB 2.0656 million. Similar criminal actions underlie Cases 2 and 5 (see Appendix 1).

This phenomenon also occurs in commercial arbitration, where parties might create a fictitious commercial agreement to evade debts. For instance, in Case 3, a stressed debtor fabricated a fraudulent housing lease contract to avoid paying legitimate debts. The arbitrator in the case colluded with the debtor’s lawyer by endorsing the falsified evidence and incorrectly affirming the validity of the housing lease agreement. Consequently, the arbitrator was convicted of “perversion of law in arbitration,” whereas the debtor faced “false litigation” charges for unlawfully fabricating facts and evidence. A similar scheme was used to fraudulently seek the recognition of trademarks through arbitration. In Case 23, trademark agents approached the defendant, who served as the Deputy Director and Secretary-General of the Zhaotong Arbitration Commission at the time. The defendant agreed to assist the agents and received bribes during the arbitration hearings, in which claimants falsely alleged trademark infringement.

Admission of False Evidence

The behavior of six defendants in three cases can be categorized under “admission of false evidence.” This category refers to situations where arbitrators issued biased awards by knowingly admitting falsified evidence, disregarding significant evidence, and dismissing objections from the opposing party for motives beyond the application of the law, usually in exchange for a bribe. For example, in Case 6, an arbitrator deliberately issued an arbitral award that contradicted the evidence presented in the proceedings with the aim of inflating the claimant’s credit over the defendant. The arbitrator was found to have accepted a bribe of RMB 30,000 from the claimant in connection with this case. In Case 26, two labor arbitrators relied on false attendance records provided by the employer, who also gave the arbitrators shopping cards as gifts. In Case 27, a similar scenario was reported in the media, wherein three arbitrators failed to conduct on-site inspections or assessments to verify the existence of disputed merchandise and instead relied solely on paper records as conclusive evidence. However, due to the absence of a full court decision regarding Case 27, details about the facts of this case remain limited.

Unlawful acceptance of cases

The third criminal behavior pattern identified involves intentionally accepting cases without a valid arbitration agreement (summarised as “unlawful acceptance of cases” in Table 6), typically in connection with bribe-taking. For example, in Cases 16 and 17, two officials of an arbitral institution were accused of receiving bribes totalling RMB 228,657 and RMB 163,000, respectively, to process cases lacking a valid arbitration agreement. In these cases, the disputing parties only agreed that “in the case of any disagreement over the repayment of this loan, the arbitration shall be conducted under applicable law.” Consequently, the parties did not agree on any specific arbitration institution, nor did they make any additional agreements. The court determined that there was no legal basis for the arbitral proceedings within the arbitral institution and ultimately convicted the officials of bribery and perversion of law.

Similarly, in Case 6, an arbitrator intentionally issued arbitral awards in seven cases despite the absence of valid arbitration agreements, after receiving gifts totalling RMB 6,887 from the applicants. In these cases, the parties had either explicitly agreed to court jurisdiction or had not established any valid procedure for dispute resolution. The arbitrator deliberately disregarded these facts and proceeded with the cases at the applicants’ request. The court held that this behavior violated the basic principle that “an arbitrator should ensure fairness in the arbitration process and impartially resolve disputes based on the facts and legal provisions.”

Also, in these cases, the courts did not base their convictions solely on the arbitrators’ decision to proceed without valid arbitration agreements. Instead, the convictions were explicitly tied to the arbitrators’ receipt of bribes or gifts.

Unilateral issuance of arbitration awards

Finally, one case can be identified as a “unilateral issuance of an arbitration award.” Although this situation occurred in only one instance, Case 4, the specifics of this conviction are worth noting. In this case, the court imposed criminal liability on the presiding arbitrator for issuing arbitration awards without majority consent. The dispute in Case 4 arose between the parties due to an invalid merger contract. To resolve the dispute, the parties submitted an application to the Xingtai Arbitration Commission. After five hearings and nine panel discussions, the three arbitrators held differing opinions on the liability to be ascribed to each party. The presiding arbitrator argued that “a proper consideration of relevant precedents and the allocation of fault liability should be taken into account,” whereas the other two arbitrators suggested that the respondent should bear 50 percent and 90 percent of the damages, respectively. Ultimately, the presiding arbitrator unilaterally rendered an award attributing 70 percent of the loss to the respondent without a majority decision being reached. Evidence indicated that the presiding arbitrator had developed a relationship with one of the parties by accepting banquet invitations and gifts, and had even attempted to solicit a bribe prior to the tribunal proceedings. However, he ultimately did not render an award in favor of that party. The court convicted the arbitrator of “perversion of law” based on the rationale that issuing an award without a collegial decision of the arbitral tribunal violated the applicable arbitration rules.

Distinguishing Legal Error from Criminal Behavior

In summary, arbitrators in China may face criminalization if they engage in behaviors that fundamentally fail to adhere to established rules of arbitral proceedings or are otherwise involved in fraudulent arbitral proceedings. It is worth noting that a common feature among these cases is that defendants appeared to have been motivated by obtaining illicit advantages or advancing corruption-related intent. In other words, mere misinterpretations of law or fact have not, by themselves, triggered criminal liability for arbitrators.

This is a particularly significant finding, given that many decisions made by an arbitral tribunal involve an element of subjective evaluation. This is especially true when assessing evidence or determining the validity of an arbitration agreement. Notably, Chinese courts have not convicted arbitrators solely for wrongful decisions in these areas. Instead, they have linked such rulings to corruption-related behavior or the existence of close connections between one party and the arbitrator, mitigating concerns that criminal provisions could be used to punish arbitrators for mere errors in interpreting facts or law.

Furthermore, it should be noted that at the heart of some of these cases were close relationships between parties and arbitrators that ultimately developed into the described criminal behaviors. Indeed, it is possible to identify close bonds between parties and arbitrators underlying many of the cases. These relationships include familial bonds (Case 5) and work associations (Case 1), in addition to connections intentionally established for convenience (Case 2). For example, in Case 5, the arbitrator assisted the disputing party in preparing fraudulent proceedings due to their familial connection as they were brothers-in-law. In Case 1, the three arbitrators relied on false evidence, apparently influenced by their awareness that one of the disputing parties had connections to their former leader in the arbitration commission. In Case 2, the arbitrator accepted an invitation to dinner from the claimant several days before the hearings, establishing a social relationship that subsequently developed into criminal behavior.

More broadly, some of these behaviors can be considered manifestations of China’s unique “guanxi” system (Jones Reference Jones1994). Rooted in Confucian principles of reciprocity, trust and hierarchy (Forrest and Norris Reference Forrest and Norris2013, 426) and emphasizing the importance of trust and mutual defence within Chinese social groups (Jones Reference Jones1994; Brown and Rogers Reference Brown and Rogers1997; Ali Reference Ali2010), guanxi is frequently used to explain the intertwining of personal relationships with political and business connections in the Chinese context (Tran Reference Tran2025, 319–321). This system’s dominance in social life fosters an environment where promises and obligations are exchanged for continued favors, sometimes leading to corruption-like behavior (Forrest and Norris Reference Forrest and Norris2013).

These embedded practices have been linked to distortions within the Chinese legal system (Wang Reference Wang2014) and, in particular, to the outcomes of judicial decisions (He and Ng Reference He and Hang Ng2017). Within the Chinese judicial system, judges have reported being frequently approached by parties seeking to leverage personal connections to secure more favorable outcomes (Wang Reference Wang2015). In the field of arbitration, the persistence of personal relationships and networks in China has similarly been associated with performance and impartiality issues among arbitrators (Gu Reference Gu2017). However, the question of how these practices shape the behavior of arbitrators remains largely underexplored.

Some of the cases in this sample reflect deeply ingrained Chinese social practices and provide insight into how such practices may evolve into abuses of law in an arbitration context. Specifically, some cases involved the exchange of small gifts and participation in social activities to foster personal relationships, ultimately giving rise to arbitral decisions that favored the connected party. For instance, in Cases 1, 2, and 4, the defendants were invited to social events, such as fishing trips or dinners, and received small gifts, including wine and rice noodles. The arbitrators were subsequently found to have issued decisions that benefited the involved parties.

In other cases, these relationships took on more explicit quid pro quo, bribe-like characteristics, with arbitrators receiving amounts of money or gifts that significantly exceeded socially accepted practices. For example, in Case 3, the arbitrator accepted a bribe of RMB 53,000 after issuing unlawful awards, whereas in Case 6, the arbitrator received RMB 30,000 as a bribe. Although these cases may align more closely with what is generally described as “bribery,” the individuals were ultimately convicted of “perversion of law in arbitration.” This is because the amounts did not exceed the thresholds necessary to qualify as bribery under judicial interpretations issued by the Supreme People’s Court and the Supreme People’s Procuratorate.

Discussion

This study elucidates the criminalization status of arbitrators in Mainland China, addressing concerns regarding the crime of “perversion of law in arbitration.” Three main findings are summarised below from a systematic analysis of cases where arbitrators have been prosecuted.

Non-Abuse of “Perversion of Law in Arbitration”

The findings of this study reveal that Chinese arbitrators face minimal exposure to criminal charges, with only twenty-seven cases identified from 2001 to the end of 2023. Specifically, the crime of “perversion of law in arbitration” is rarely applied, having served as the basis for the conviction of only sixteen defendants in eleven cases. The rarity of arbitrators facing criminal prosecution under this provision becomes more evident against the backdrop of the high volume of arbitration cases in China. In 2023 alone, China’s 279 commercial arbitration commissions handled 607,260 cases (CIETAC 2025). This low incidence rate highlights the exceptional nature of these prosecutions.

Notably, the identified cases are concentrated in relatively small and regional commercial or labor arbitration institutions, involving commissions in Kunming, Xingtai, Binzhou, Anqing, Zhaotong, and Qingdao. By contrast, the most established commercial arbitration commissions, such as the China International Economic and Trade Arbitration Commission (CIETAC), the Shanghai International Arbitration Center (SHIAC), the Shanghai Arbitration Commission (SHAC), and the Beijing International Arbitration Center (BIAC), have not been linked to cases where this provision has been applied. The fact that this provision has not been applied in proceedings linked to the major Chinese arbitral centres further underscores the limited scope and influence of these prosecutions.

Several factors may explain the limited number of criminal cases against arbitrators in China, the first being the ambiguity regarding arbitrators’ status in Mainland China, which complicates any determination of the responsible entities for oversight and investigation by supervisory authorities. The National Supervisory Commission of the People’s Republic of China (NSC), established in 2018, is tasked with supervising and investigating corruption among “public officials” and “other individuals performing public functions in accordance with the law.”Footnote 9 However, an ongoing debate exists concerning whether and when arbitrators fall within the purview of the NSC. This debate arises from the dual nature of arbitration, which is contractual in origin but judicial in function (Cevc Reference Cevc2019, 406). By contrast, judges, as public officials, are subject to more focused scrutiny by the NSC and have historically faced higher oversight levels and convictions (Li Reference Li2012).

More broadly, the rarity of these cases suggests that a combination of professional incentives, reputational concerns, and comprehensive legal mechanisms effectively controls arbitrators’ behavior, thereby explaining the limited recourse to criminal proceedings. As previously mentioned, market and reputation mechanisms significantly incentivize arbitrators to maintain ethical standards, thus minimizing instances of serious misconduct. The arbitration community’s emphasis on professional integrity and the potential reputational damage resulting from unethical behavior are powerful deterrents against deviations.

In addition, a guiding principle contributing to the limited occurrence of “perversion of law” cases is the concept of “modesty” within criminal law (Tan Reference Tan2010). This foundational principle posits that criminal law should be a measure of last resort, utilized only when other legal frameworks fail to effectively address criminal activities (Lin Reference Lin2023). In the context of arbitration, established mechanisms within the arbitration legal framework address arbitrators’ misconduct without resorting to criminal law. Disputing parties have the option to file civil claims to set aside or refuse the enforcement of arbitration awards if they can provide evidence of bad-faith actions by arbitrators. These provisions offer legal alternatives for ensuring accountability and maintaining the integrity of arbitration proceedings, thereby diminishing the necessity for criminal prosecutions.

The Alleged “Legislative Excess” of Perversion of Law in Arbitration

In addition to concerns regarding potential abuses, as aforementioned, Chinese scholars have criticized the potential legislative excess of establishing the offence of “perversion of law in arbitration” (Fan Reference Fan2009; Tan Reference Tan2010; Han Reference Han2011), arguing that existing provisions within the Chinese criminal system sufficiently regulate arbitrators’ behavior. An analysis of the available cases reveals that no arbitrators have been convicted solely for “distorting laws” in the sense of merely misinterpreting the law; rather, the cases consistently involve elements of corruption or favoritism. However, this does not necessarily mean that the crime of perversion of law is unnecessary in the Chinese legal system.

As noted above, the fragmentary nature of China’s arbitration market means that the mix of reputational and legal mechanisms relied upon in other jurisdictions sometimes appears insufficient to deter misconduct in the Chinese context. Unlike in elite international circles, where a reputation for impropriety results in professional ostracization and high barriers to entry filter entrants (Dezalay and Garth Reference Dezalay and Garth1998; Ginsburg Reference Ginsburg2003), the vastness and anonymity of China’s domestic market limit the effectiveness of such social controls. In this specific socio-legal context, this provision appears to serve at least two specific functions that compensate for the lack of a cohesive professional community through stronger regulatory intervention.

First, it addresses gaps within criminal legislation in specific contexts, thereby covering corruption-related behavior in arbitration that otherwise would not be criminalized. Second, it strengthens the ability of wronged parties to seek judicial remedies concerning arbitral awards, allowing for legal recourse that guarantees that serious misconduct in arbitration is formally sanctioned by the state, while maintaining a high threshold of finality for arbitral awards.

The ability of the crime of “perversion of law” to serve as a mechanism to address legislative gaps is evidenced in several cases. For instance, in Case 3, the defendant received a bribe of RMB 53,000 after issuing a biased award. According to judicial interpretations issued by the Supreme Court and the Supreme Procuratorate, the monetary threshold for most “bribery” prosecutions is RMB 30,000, but for non-state personnel, the threshold is RMB 60,000.Footnote 10 In this case, the court determined that Shu, as a part-time arbitrator, did not meet the criteria for “bribery” as he was not considered a public official. In addition, the amount involved did not meet the threshold for the crime of “bribery of non-state personnel.” Given the significant sum of the bribes, rendering a verdict of not guilty was deemed inappropriate by the court. Consequently, invoking the “perversion of law” offence allowed the court to determine that a crime was committed despite the amount in question not meeting the bribery thresholds defined by the Chinese judiciary.

Furthermore, this crime facilitates the attainment of judicial remedies for arbitration by providing evidence to demonstrate a biased arbitration award and facilitating decisions to set aside or refuse enforcement. Chinese legislation concerning judicial remedies in arbitration has established “misconduct of perverting the law” as grounds for setting aside or refusing enforcement of an arbitral award.Footnote 11 Under current judicial interpretations issued by the Supreme People’s Court, plaintiffs are required to show that effective criminal prosecutions or disciplinary actions were taken to support their requests to invalidate an arbitral award under this ground.+Footnote 12

This requirement of a criminal investigation serves a crucial gatekeeping function. It generally preserves the finality of arbitral awards by shielding them from frivolous challenges based on vague allegations of bias, while ensuring that legal recourse remains available for instances of serious misconduct. A valid criminal judgment of “perversion of law” provides the necessary evidentiary basis for judicial intervention, such as setting aside an award. By setting this high threshold, the system ensures that such interventions remain exceptional events, thereby preserving the overall integrity of the arbitral process. For example, in Case 4, after a judgment of perversion of law was rendered against the arbitrator, one of the disputing parties successfully utilized this judgment to seek non-enforcement of the arbitration award.

Inconsistent Application in Judicial Practice

A significant issue identified in the analysis is the inconsistent interpretation and application of the relevant criminal statutes by judicial authorities regarding arbitrators, particularly concerning the boundary between the crimes of “bribery” and “perversion of law” in the context of arbitrator misconduct.

One aspect of this interpretive inconsistency relates to the scope of the “perversion of law” offence. In some cases, prosecutors initially charged defendants with “perversion of law,” but the courts ultimately convicted the defendants of “bribery” (see cases 8 and 9). The court’s rationale was that the “perversion of law” statute should be narrowly construed to apply only in the context of commercial arbitration, excluding labor arbitration. This interpretation was based on the court’s view that the term “arbitration” in the legislation specifically refers to civil and commercial arbitration proceedings. Other courts, however, have found the “perversion of law” offence to encompass misconduct in both commercial and labor arbitration settings (for example, cases 1, 2, 5, 26). For instance, in Case 5 from 2018, the court determined that the “perversion of law in arbitration” statute under Article 399(A) of the CCL applies to “anyone who undertakes the duties of arbitration according to the law”—meaning it covers not only commercial arbitrators but also those exercising arbitration functions under labor laws.

This lack of consistent judicial interpretation is exacerbated by the fact that most cases involve scenarios where the arbitrators both misapplied the law and accepted bribes or other illicit benefits. The common pattern sees arbitrators engage in unlawful conduct favoring one party in exchange for improper payments or other illegitimate benefits. Consequently, apart from the legal guidance on bribe amounts, courts have considerable discretion in determining whether such cases should be prosecuted as “bribery” or the more serious offence of “perversion of law.”

An analysis of the case sample reveals certain trends in how courts exercise this discretion. First, officials within arbitration commissions are more likely to be convicted under bribery statutes compared to the “perversion of law” offence. Of the thirteen defendants found guilty of “perversion of law,” twelve were arbitrators, with the only exception being a vice-director of an arbitral institution. This pattern aligns with the legislative intent behind the “perversion of law” statute, which is specifically targeted at illegal acts committed by arbitrators during arbitral proceedings. Therefore, arbitrators remain the primary subjects of “perversion of law” charges unless other officials are involved in joint crimes with them.

Second, convictions for bribery-related offences tend to face less contestation than those for “perversion of law.” Of the nine defendants convicted solely of bribery, eight did not appeal their verdicts. By contrast, judgments involving “perversion of law” are more frequently challenged, with 75 percent of convictions under this provision being appealed, either by the defendants themselves or by the prosecutorial authorities.

Conclusion

This empirical investigation offers important insights into the use of criminal law to regulate the conduct of arbitrators in Mainland China. Although this study cannot account for potential unreported cases or instances where criminal investigations were initiated but did not result in prosecution, the findings nonetheless challenge the assumption that the criminalization of arbitrator misconduct inherently undermines the integrity of arbitral proceedings. Contrary to critics’ concerns, the analysis of twenty-seven criminal cases against arbitrators in China suggests that the controversial “perversion of law in arbitration” provision has not been leveraged to improperly influence or disrupt the arbitration decision-making process.

The data indicate that the vast majority of prosecutions were centred on instances that had elements of bribery, corruption, and other serious violations of arbitrators’ professional duties—not mere errors or good-faith disagreements in the application of the law. Although some discrepancies in the application of this provision were observed, on balance, the findings appear to substantiate the view that carefully tailored criminal laws can play a functional role in sanctioning legal malpractice and addressing regulatory gaps in the very specific context of Mainland China arbitration.

While the rarity of prosecutions might suggest that market and reputation mechanisms are sufficient to disincentivize serious ethical malpractice, this study argues for a more nuanced understanding. As noted, the fragmented nature of China’s domestic market often limits the effectiveness of reputational constraints. In this context, the Chinese experience offers an instructive case study for jurisdictions balancing the prevention of misconduct with the preservation of arbitral independence. It demonstrates that criminal prosecution can serve as a necessary instrument to curb corrupt practices, particularly those occurring outside established elite arbitration centres. While a strong arbitration culture and civil oversight may suffice in many jurisdictions, tailored criminal provisions remain relevant where such mechanisms prove insufficient.

It is important to emphasise that the unique features of China’s arbitration framework, arbitral culture, and criminal justice system limit the generalizability of these findings to other jurisdictions. While the data show no evidence of widespread abuse of Article 399(A), the existence of such a provision may still raise legitimate concerns. It could deter qualified arbitrators from entering the market and, perhaps more significantly, contribute to the perception that China’s arbitration environment falls short of international standards. For jurisdictions seeking to position themselves as arbitration-friendly, this perception could undermine their attractiveness as arbitral seats, particularly in the competitive global arbitration market.

Additionally, the study provides insights into the arbitral community’s attitudes toward regulation. The global arbitration community has historically resisted regulatory interventions such as licensing requirements, professional oversight, and liability mechanisms, arguing that such measures could undermine the independence and flexibility of arbitration. These positions often align with the community’s professional interests, reflecting a broader trend in which a combination of principled beliefs and strategic considerations shapes regulatory preferences. By contrast, China’s regulatory approach tends to place a higher premium on regulatory control over a vast and sprawling arbitration market designed to provide mass justice rather than elite services for highly sophisticated commercial entities.

This distinction explains the disconnect observed between China’s domestic approach and the global arbitration community (Fan Reference Fan2013). The international community operates on a paradigm of professional autonomy, assuming that arbitrators are capable of policing their own boundaries (Moreira Reference Moreira2024). China’s approach reflects a paradigm of state intervention, where arbitration is viewed not merely as a self-regulated commercial service, but as a public service demanding public oversight. The disconnect is therefore not merely a lag in legal development, but a fundamental divergence in how the relationship between the State and the legal profession is conceptualized. The Chinese experience suggests that the global script of arbitral immunity is not a universal imperative, but a context-dependent privilege that presupposes a high-trust, self-regulating professional community.

This conceptual divide helps explain the global arbitration community’s apparent disinterest in legal developments within the Chinese market. While criminal provisions targeting arbitrators have drawn widespread criticism elsewhere, the international arbitration community has largely overlooked China’s adoption of Article 399(A) and has rarely engaged with these regulatory developments. This muted response likely reflects a perception that China’s arbitration market operates in relative isolation from the global arbitral ecosystem. Ultimately, this illustrates the complex relationship between local arbitral groups and the international community, where varying levels of integration dictate the degree of mutual interest and engagement.

This disinterest is, however, unwarranted. The Chinese approach to arbitration, given its many idiosyncrasies, provides a valuable counterpoint to prevailing regulatory practices. In general terms, it underscores the importance of context in understanding the design of regulatory frameworks. More specifically, regarding the intersection of criminal law and arbitration, the Chinese experience highlights the potential consequences—both positive and negative—of criminalizing arbitrator misconduct. By examining this intersection in Mainland China, this study adds nuance to discussions about the regulation of arbitrators and offers practical lessons for jurisdictions seeking to balance accountability, independence, and the integrity of arbitration.

Funding Statement

This research was supported by the Asia-Pacific Academy of Economics and Management, University of Macau, grant number APAEM-INT/00015/2023.

Appendix 1. Cases Summary