Introduction

As a result of technological development, mobile phones used only for communication have been replaced by smartphones with internet access and their operating system. Besides talking and texting, smartphones have many features, such as connecting to the internet, watching movies and videos, taking photos, GPS, playing online and offline games, listening to music, accessing social media, shopping, and banking, thanks to operating systems and applications. High-tech operating systems, more vendors, and the creation of many applications increased the number of users, and it has become an essential element in people’s communication, entertainment, access to information, and planning of their daily lives.

Although smartphones make our daily lives easier, in case of problematic use, they cause physical, mental, and behavioural problems affecting general functionality. Many studies have found a significant relationship between problematic phone use and low self-esteem, depression, stress, and anxiety (Elhai et al., Reference Elhai, Dvorak, Levine and Hall2017). It has been reported that smartphone addiction in students negatively affects physical health by reducing the amount of physical activity such as walking. Further, increased fat mass and decreased muscle mass have been reported due to reduced health-related physical activity (Kim et al., Reference Kim, Kim and Jee2015). Studies also report that it negatively affects work performance and productivity (Wilmer et al., Reference Wilmer, Sherman and Chein2017).

Using smartphones includes many user profiles, young, old, children, working, and non-working. However, studies indicate that the highest rate belongs to the young population when the smartphone user profile is examined (Olson et al., Reference Olson, Sandra, Colucci, Bikaii and Chmoulevitch2022). In Turkey, the rate of mobile phone/smartphone usage, which was 53.7% in 2004, increased to 98.7% in 2019 and rose to 99.7% in 2023 (TUIK 2019; TUIK 2023). Another research reported that university students spend an average of 5 hours daily on their mobile phones (Celikkalp et al., Reference Celikkalp, Bilgic, Temel and Varol2020). As smartphone use becomes increasingly widespread, it is essential to examine usage patterns and their potential health risks. Smartphone addiction is characterized by behaviours such as repetitive phone checking, increased or intensified usage time, feeling distressed without a telephone, and functional impairments in daily life (Lin et al., Reference Lin, Chiang, Lin, Chang, Ko, Lee and Lin2016). Most studies investigating the health consequences of smartphone addiction show that it has adverse effects on health, primarily affecting mental well-being but also contributing to physical issues (Ratan et al., Reference Ratan, Parrish, Zaman, Alotaibi and Hosseinzadeh2021). In Turkey, smartphone addiction among university students is a growing concern due to its high prevalence and associated health risks (Aker et al., Reference Aker, Şahin, Sezgin and Oğuz2017; Karaoglan et al., Reference Karaoglan Yilmaz, Avci and Yilmaz2022; Zeyrek et al., Reference Zeyrek, Tabara and Çakan2024; Kurtaran, Reference Kurtaran2024; Yılmaz et al., Reference Yılmaz, Meriç, Bülbül and Türkkan2025).

Given these concerns, promoting a health-conscious lifestyle is essential in minimizing the negative impact of smartphone addiction. According to the World Health Report, many risk factors contribute to the global disease burden. Reducing risks and promoting health will not only contribute to preventing death and disability but also strengthen social values by creating an environment where governments and society are engaged. Knowing and recognizing the causes of disease and risk factors is essential for promoting health. A health-promoting lifestyle can be defined as a set of behaviours that serve individuals to maintain and increase their well-being (Pender et al., Reference Pender, Murdaugh and Parsons2014). A health-promoting lifestyle includes spiritual growth, health responsibility, physical activity, nutrition, interpersonal support, and stress management. These topics are closely related, and the absence of one will negatively affect the others.

Research on smartphone addiction, its contributing factors, and its consequences has been increasing rapidly in recent years. This study aimed to investigate the relationship between smartphone addiction and a health-promoting lifestyle in young adults during their university years. It is a crucial period when mobile technology use rises significantly, and temporary habits turn into long-term behaviours. To address this, the study explores the research question of how increased smartphone addiction impacts a health-promoting lifestyle among university students during a period of habit formation.

Materials and methods

Setting

This study was conducted at Dokuz Eylül University’s Tınaztepe Campus in İzmir, Turkey, a large and well-known campus offering various academic programmes. The Tınaztepe Campus has several key faculties, including Maritime, Science, Literature, Law, Architecture, Engineering, and Business. The campus serves a diverse student population, providing a rich environment for studying behaviours related to smartphone usage. Data were collected during the Spring 2019 semester (April–June 2019), with students from various disciplines participating in the survey. This setting is ideal for studying smartphone addiction, as university students are in a critical period of behavioural development, where mobile technology plays an increasingly significant role in their daily lives.

Participants

The sample size was 864 based on a total campus population of (N = 21,361) students. The calculation was performed using a formula with a p-value of 0.10, q-value of 0.90, and d-value of 0.02, consistent with similar studies on smartphone addiction risk. Ultimately, 911 students who confirmed owning a smartphone were included in the study. The study included university students who voluntarily agreed to participate. Students who did not own a smartphone (n = 13) or declined to participate (n = 26) were excluded from the study. The survey was conducted face-to-face during class breaks, and the researcher recorded responses. Since the researcher recorded responses, the study had no missing data. To collect data, we used a form that included some participants’ characteristics, such as the Smartphone Addiction Scale-Short Version (SAS-SV) and Health Promotion Lifestyle Profile II (HPLP II).

Data collection tools

Sociodemographic form

This form includes questions about students’ sociodemographic data prepared by the researchers using the literature (Age, gender, income level, whom they live with, having a partner, smoking status, alcohol usage, calculated BMI-kg/m2, subjective assessment of their health status, sleep quality, daytime sleepiness, smartphone addiction, for what purposes they use smartphones). The classification was used to categorize income levels based on financial sufficiency: Strained: Less than the expense; Financially Balanced: Equal; Financially Comfortable: More than an expense.

According to the literature, the form was designed to include variables that may influence smartphone addiction. All data collected were based on the individuals’ self-reported statements, not on a measurement.

Smartphone addiction scale-sort version (SAS-SV)

Kwon et al. developed a smartphone addiction scale (SAS), which consists of 33 questions and a short version (SAS-SV) consists of 10 questions. It has been shown to have a single-factor structure (Kwon et al., Reference Kwon, Kim, Cho and Yang2013). Cronbach’s alpha value was 0.91 in the initial validation study. Noyan et al. (Reference Noyan, Darçın, Nurmedov, Yılmaz and Dilbaz2015) translated and validated the short version (SAS-SV) in Turkish, and the Turkish version of SAS-SV was conducted in a university student sample (Noyan et al., Reference Noyan, Darçın, Nurmedov, Yılmaz and Dilbaz2015). The Cronbach’s alpha value in the Turkish version was 0.867. The measure utilizes a six-point Likert scale response format ranging from ‘1’ (strongly disagree) to ‘6’ (strongly agree), with a maximum total score of 60. The scale uses gender-specific cut-off scores to determine smartphone addiction risk (31 and above for males and 33 and above for females). Based on the scale’s original validation study, these thresholds have been established to improve accuracy in identifying problematic smartphone use.

Health promotion lifestyle profile II (HPLP II)

This is a well-known instrument measuring health promotion lifestyle behaviour. Walker developed it in 1987 and later refined it, and it has been translated into several languages (Walker et al., Reference Walker, Sechrist and Pender1987). The HPLPII is a revision of HPLP developed by Walker et al. measuring health-promoting lifestyles by focusing on self-initiated actions and perceptions that serve to maintain or enhance the level of wellness, self-actualization, and fulfilment of the individual. It is a 52-item questionnaire comprising six subscales: nutrition, physical activity, health responsibility, stress management, interpersonal relations, and spiritual growth. The HPLPII asks respondents to indicate on a 4-point Likert scale (never, sometimes, often, and routinely) how often they adopt specific health-promoting behaviours. Overall health-promoting lifestyle and behavioural dimension scores are calculated using the mean response for the 52 items and each dimension subscale (eight to nine items). The lowest total score is 52, and the highest score is 208. Pınar et al. translated and validated in Turkish with an internal consistency coefficient of 0.92, and this value varies between 0.71–0.83 for six subscales (Pinar et al., Reference Pinar, Celik and Bahcecik2009).

Nutrition (N) refers to selecting and arranging the individual’s meals and the choice of food. Physical activity (PA) evaluates regular exercise. Health responsibility (HR) includes taking responsibility for one’s health, having health information, and getting expert help when necessary. Stress management (SM) contains methods of detecting the source of stress, controlling stress, and relaxing oneself. Interpersonal relations (IR) aim to establish close and sincere ties with people to determine the level of communication and continuity with their near environment. Spiritual growth (SG) evaluates feeling good and fulfilled.

Data analysis

Data were analysed using the IBM SPSS Statistics 22.0 version. Descriptive statistics summarized participants’ sociodemographic characteristics with categorical variables presented as frequencies and percentages.

Between-group frequency differences were tested using a two-tailed chi-square analysis with significance at p < 0.05.

A backward stepwise logistic regression model was employed to evaluate the factors associated with smartphone addiction.

P < 0.05 was used to include a variable in the multivariate model. In correlation analysis, the relationships between data are assumed to be linear, looking at the point-scatter plot, the distribution of points was linear.

Independent variables included gender, having a partner, self-perceived smartphone addiction, sleep quality, and HPLP II total score. Variables were selected based on theoretical relevance and findings from previous literature. Only statistically significant variables in univariate analyses were included in the regression model to ensure a meaningful selection of predictors.

Odds ratios (ORs) and their corresponding 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) were reported to quantify the strength of associations. A power analysis was conducted before the study to ensure an adequate sample size for regression analysis. Based on the power analysis, a sample size of 422 participants was determined to provide a statistical power of 0.95, with a critical z-value of 1.97.

Since the researcher collected all data directly from participants without incomplete responses, the final analysis did not contain missing data.

Ethical considerations

All study procedures were conducted according to the ethical guidelines of the research team’s institutional review board and the Declaration of Helsinki. This study was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of Izmir Dokuz Eylul University (Date/no: 2019/1-66). The data were collected face-to-face, and only volunteers were asked to participate. Written informed consent and verbal consent were obtained from the participants before data collection, ensuring they were fully aware of the purpose of the study, their voluntary participation, and their right to withdraw at any time without penalty. In compliance with the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), this study ensured the confidentiality and security of participants’ data throughout the research process. All personal data were anonymized or pseudonymized to protect participants’ identities. The data were stored securely, with access limited to authorized research personnel only. Furthermore, data were retained only as long as necessary for the study, after which they were securely disposed of. These measures were taken to guarantee compliance with GDPR requirements and to safeguard participants’ privacy and personal information.

Results

The research was conducted through a survey with 911 students who owned smartphones and voluntarily participated. The sample size was calculated as 864 based on the campus population. Students who did not own a smartphone (n = 13) or declined participation (n = 26) were excluded.

Of the students, 48.5% (n = 442) were female. The mean age was 21.24 ± 1.47. When the students were asked whom they lived with, 49.9% (n = 455) stated that they lived with a roommate, 31.9% (n = 291) with their family, and 18.1% (n = 165) lived alone. Of the students, 39.8% (n = 363) had income less than their expenses, and 15.4% (n = 140) had more income than their expenses.

According to the body mass index, 7.9% (n = 140) of the students were classified as underweighted, 67.2% (n = 612) as normal weighted, 21.4% (n = 195) as over-weighted, and 3.5% n = 32) as obese. Of the students, 39.6% (n = 361) had a partner, 52.8% (n = 373) smoked, and 74.8% (n = 681) used alcohol. When the students were asked how they evaluated their health status, 6.4% (n = 59) answered as bad or very bad; 28.3% (n = 258) rated their sleep quality as bad or very bad, and 62.6% (n = 570) of the students stated that they had daytime sleepiness.

The most common answers to the ‘For what purposes do you use your smartphone?’ question were voice and video conversation (94.3%, n = 859) and playing games (51.0%, n = 465). Of the students, 55.1% (n = 502) actively used one to three social networking sites. When asked to evaluate themselves in terms of smartphone addiction, 44.1% (n = 402) of the students assessed themselves as smartphone addicts.

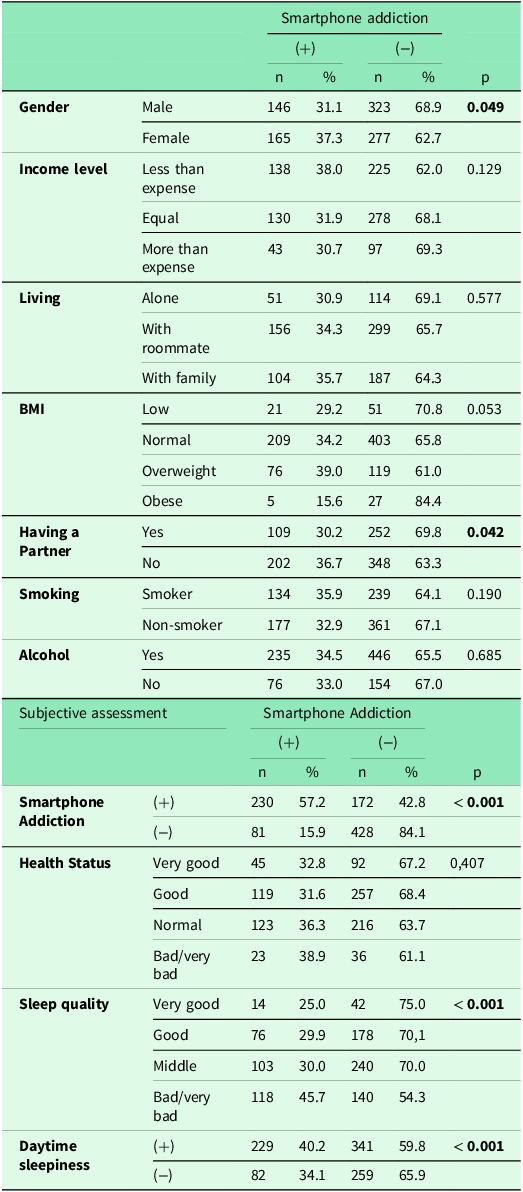

In our study, Cronbach’s alpha value of SAS-SV was 0.875. According to the students’ answers to the 10-question SAS-SV, 311 (34.1%) students, whose SAS-SV score was 31 and above for men and 33 and above for women, were smartphone addicts. Table 1 shows the relationship between smartphone addiction and some characteristics of students. Smartphone addiction was found to be significantly associated with self-perceived addiction, as individuals who considered themselves addicted had much higher addiction rates (p < 0.001). Additionally, poor sleep quality and daytime sleepiness were strongly linked to higher smartphone addiction levels (p < 0.001). Gender and relationship status also showed significant associations, with females and those without a partner being more prone to smartphone addiction (p = 0.049, p = 0.042).

Table 1. Relationship between smartphone addiction and some characteristics of students

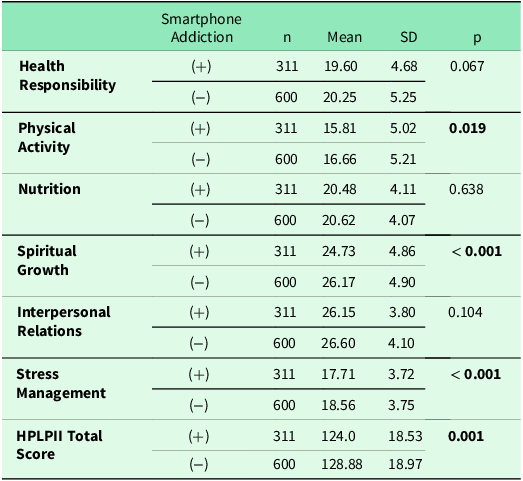

The mean total score of HPLP II was found to be 127.38 ± 18.92. When the subscales were examined, the nutrition mean score was 20.57 ± 4.08, Physical Activity score was 16.37 ± 5.16, Health Responsibility score was 20.02 ± 5.07, Stress Management score was 18.27 ± 3.76, Interpersonal Relations score was 26.45 ± 4.01, and Spiritual Growth score 25.68 ± 4.93. Cronbach’s alpha value of the HPLP II examined in our study was 0.875. The relationship between smartphone addiction and HPLP II scores is shown in Table 2. Smartphone addiction was significantly associated with lower scores in physical activity (p = 0.019), spiritual growth (p < 0.001), stress management (p < 0.001), and overall health-promoting lifestyle (HPLP II total score, p = 0.001).

Table 2. The relationship between smartphone addiction and HPLP II scores

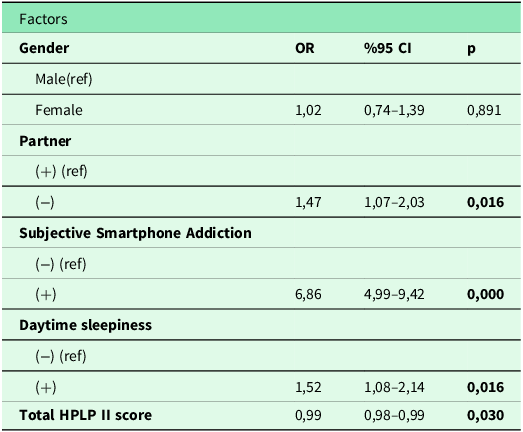

A backward stepwise logistic regression model was employed to evaluate the factors associated with smartphone addiction. Gender, having a partner, self-perceived smartphone addiction, sleep quality, and HPLP II total score were selected (Table 3). As a result of the logistic regression analysis, being without a partner (OR: 1.47, 95% CI: 1.07–2.03), considering oneself a smartphone addict (OR: 6.86, 95% CI: 4.99–9.42), and daytime sleepiness (OR: 1.52, 95% CI: 1.08–2.14) were found to be significantly associated with smartphone addiction. The increase in the HPLP II total score was protective regarding smartphone addiction (OR: 0.99, 95% CI: 0.98–0.99).

Table 3. Multivariate logistic regression analysis of factors associated with smartphone addiction

Discussion

This study compared smartphone addiction, healthy lifestyle behaviours, and some sociodemographic characteristics of university students. Sleep and health conditions, which were not included in HPLP II, were included in the study in line with the subjective evaluations of the students. This study revealed that a significant proportion of university students were at risk for smartphone addiction. Key factors such as being female, not having a partner, self-recognition of smartphone addiction, poor sleep quality, and daytime sleepiness were strongly linked to this risk. Additionally, smartphone addiction was found to correlate with lower scores on the Health-Promoting Lifestyle Profile II (HPLPII), particularly in areas like physical activity, stress management, and spiritual growth.

Smartphone addiction

In our study, the smartphone addiction rate was 34.1% among students. In a meta-analysis, the highest consistent rates were seen in China and Saudi Arabia, followed by Malaysia, Brazil, South Korea, Iran, Canada, and Turkey (Olson et al., Reference Olson, Sandra, Colucci, Bikaii and Chmoulevitch2022). While the smartphone addiction risk in our study aligns with findings from other studies conducted in Turkey, variations in results across different countries suggest potential influences of geographical and socio-cultural factors and the periods in which the studies were conducted (Karaoglan et al., Reference Karaoglan Yilmaz, Avci and Yilmaz2022; Zeyrek et al., Reference Zeyrek, Tabara and Çakan2024; Kurtaran, Reference Kurtaran2024; Yılmaz et al., Reference Yılmaz, Meriç, Bülbül and Türkkan2025).

Differences in smartphone usage purposes may also influence usage frequency and addiction levels. In the current study, smartphone addiction in women was significantly high but lost in regression analysis. Two review studies showed that smartphone addiction is mostly higher in women, but the difference is insignificant among genders. Women use smartphones more actively in social networks and have higher self-reports and awareness, whereas men may prioritize gaming or information-seeking activities (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Liu, Ding, Ying, Wang and Wen2017). Although in literature, smartphone addiction is proportionally higher in women, there is no consensus on the issue (Olson et al., Reference Olson, Sandra, Colucci, Bikaii and Chmoulevitch2022; Kwon et al., Reference Kwon, Kim, Cho and Yang2013; Noyan et al., Reference Noyan, Darçın, Nurmedov, Yılmaz and Dilbaz2015; Demirci et al., Reference Demirci, Akgönül and Akpinar2015; Chen et al., Reference Chen, Liu, Ding, Ying, Wang and Wen2017, Arpacı & Kocadag Unver, Reference Arpaci and Kocadag Unver2020). These variations in usage patterns could contribute to differences in addiction risk between genders, emphasizing the need for gender-specific intervention strategies. Multivariate analysis did not sustain the univariate gender findings. Variance measures the average value of these deviations. The 26.7% value obtained highlights the need to consider gender, having a partner, self-perceived smartphone addiction, sleep quality, and HPLP II total score in clinical evaluations.

Moreover, individuals who are alone may rely more on their smartphones for social interaction and entertainment, potentially increasing their risk of addiction. In the current study, 36.7% of the students who do not have a partner have smartphone addiction. Besides, studies have shown that smartphone addicts feel lonelier (Jiang & Shypenka, Reference Jiang, Li and Shypenka2018). However, there are studies in which the never-married people have low smartphone addiction scale scores. This difference may be due to the increased frequency of voice calls and messaging for communication purposes between partners (Luk et al., Reference Luk, Wang, Shen, Wan, Chau, Oliffe, Viswanath, Chan and Lam2018).

In addition to those listed so far, using smartphones for social interaction and entertainment purposes can also cause individuals to perceive themselves as addicted and further strengthen their addiction. When students were asked whether they saw themselves as smartphone addicts, 57.2% of those who answered ‘yes’ were also classified as addicted based on the SAS-SV, which is like the literature (Kwon et al., Reference Kwon, Kim, Cho and Yang2013; Noyan et al., Reference Noyan, Darçın, Nurmedov, Yılmaz and Dilbaz2015). This suggests that self-awareness regarding smartphone addiction could be an important factor in identifying at-risk individuals. If this awareness is further developed among university students, it may serve as a key determinant for designing effective intervention strategies.

In addition to self-perception of addiction, we also examined the relationship between smartphone addiction and sleep quality. Students were asked subjectively to evaluate their sleep quality and if they experienced daytime sleepiness. Poor sleep quality and daytime sleepiness were statistically associated with smartphone addiction, which aligns with the literature (Demirci et al., Reference Demirci, Akgönül and Akpinar2015; Kurugodiyavar et al., Reference Kurugodiyavar, Sushma, Godbole and Nekar2017). Research suggests that smartphone use, particularly before bedtime, may lead to sleep disturbances due to exposure to bright screens, increased mental stimulation, and delayed sleep onset (Moattari et al., Reference Moattari, Moattari, Kaka, Kouchesfahani and Sadraie2017; Zhang & Wu, Reference Zhang and Wu2020). These findings highlight the importance of addressing smartphone usage habits to improve sleep quality and overall well-being among university students.

The relationship between smartphone addiction and HPLP II

Studies about the relationship between smartphone addiction and health-promoting lifestyle are limited. In the present study, students who were categorized as smartphone addicts had significantly lower scores of HPLP II. The regression analysis confirmed this significance. Similar studies have shown a significant relationship between low scores on the health-promoting lifestyle profile and smartphone addiction (Won & Shin, Reference Won and Shin2018). In the current study, considering the HPLP II subscales, students who were categorized as smartphone addicts had significantly lower scores on physical activity, spiritual growth, and stress management subscales. However, no significant relationship was found in health responsibility, nutrition, and interpersonal relations subscales.

The relationship between smartphone use, life satisfaction, personal and psychological well-being, and spiritual growth is complex. Smartphones’ productivity in facilitating social relations is indisputable. Forming new friendships and social relationships has been associated with behaviours contributing to subjective well-being, such as reading e-books (David et al., Reference David, Roberts and Christenson2018). Conversely, studies show that excessive smartphone use is associated with low satisfaction in social and romantic relationships (Chotpitayasunondh & Douglas, Reference Chotpitayasunondh and Douglas2016; Lapierre and Lewis Reference Lapierre and Lewis2018).

Spirituality encompasses finding meaning, self-acceptance, an acceptance of oneself and relationships among others, and between an individual’s self and the universe. As some studies have shown, a relationship between spiritual development and physical and mental health has been found. These studies have shown that people’s spiritual state affects their health positively. Negative attitudes about oneself lead to a decrease in self-esteem, which in turn increases the tendency toward smartphone addiction.

Recently, the number of studies investigating the effects of psychological factors such as depression, anxiety, loneliness, self-esteem, and life satisfaction on smartphone and social media addiction has been increasing (Elhai et al., Reference Elhai, Dvorak, Levine and Hall2017; Karaoglan et al., Reference Karaoglan Yilmaz, Avci and Yilmaz2022). Although depression, anxiety, and stress are associated with problematic smartphone use, there is an inconsistent relationship between self-esteem and life satisfaction. It is believed that individuals with low self-esteem often use the Internet to cope with issues in social relations. In contrast, those with high self-esteem enjoy expanding their social circles online, even with many real-life friends (Chen, 2020).

As seen in the studies, it is difficult to reach a clear conclusion about the relationship between spiritual growth (spirituality), interpersonal relationships, and smartphone addiction. Differences in age groups, sociodemographic factors, smartphone usage purposes, and habits may explain these inconsistent results.

Another important aspect to consider is the relationship between stress management and smartphone addiction. Stress management is crucial for young adults as they face academic, social, and personal challenges in a critical stage of life. Effective stress management can help reduce the risk of developing unhealthy coping mechanisms, such as excessive smartphone use. A meta-analytic review reported a relationship between stress and smartphone addiction. In the current study, the stress management subscale scores of students at risk of smartphone addiction were significantly low. However, some studies claimed that stress led to smartphone use, while others claimed the opposite (Won &Shin, Reference Won and Shin2018; Vahedi & Saiphoo, Reference Vahedi and Saiphoo2018). Further research involving experimental designs is needed before causal claims can be made. Physicians should understand their patients’ spirituality; this knowledge aids in delivering more holistic healthcare by offering insights into how patients perceive their illness and make decisions about healthcare and treatment.

As stress management plays a crucial role in maintaining overall well-being, proper nutrition is another significant factor in promoting a healthy lifestyle, directly impacting physical and mental health. The current study found no significant relationship between the nutrition subscale and smartphone addiction. However, studies show smartphone addiction is associated with unhealthy eating behaviours such as less consumption of fruit, vegetables, and dairy products and higher BMI (Domoff et al., Reference Domoff, Sutherland, Yokum and Gearhardt2020). In some studies, students’ smartphone addiction influences eating behaviour disorders or vice versa (Kartal & Ayhan, Reference Tayhan Kartal and Yabancı Ayhan2021). Self-reported data may have influenced the findings, as the nutrition subscale and BMI were based on participants’ subjective assessments, which can be prone to personal bias and inaccuracies.

In some studies, insufficient physical activity was closely associated with high-level smartphone addiction (Yayan et al., Reference Yayan, Düken, Suna Dağ and Ulutaş2018; Lai et al., Reference Lai, Cai, Liao, Li, Wang, Wang, Ye, Chen, Hambly, Yu, Bao and Zhang2025). The present study found a significant relationship between low physical activity subscale scores and smartphone addiction, aligning with these findings. These consistent results underscore the importance of promoting physical activity as a potential intervention to mitigate smartphone addiction risks.

Studies indicate that university students often exhibit low levels of health responsibility, which can adversely affect their overall well-being. For instance, research has shown that students display the least responsible behaviours concerning physical activity, health responsibility, and nutritional habits. However, the present study found no significant relationship between the health responsibility subscale and smartphone addiction. This lack of association could be explained by the fact that individuals at high risk of smartphone addiction may still actively engage in using e-health services, such as seeking health information online, which is a typical behaviour among university students (Beck et al., Reference Beck, Richard, Nguyen-Thanh, Montagni, Parizot and Renahy2014). Responsibility for health includes taking care of one’s health, being informed about health, and being able to seek professional help when necessary. Therefore, it is possible that despite smartphone addiction, students may still exhibit behaviours related to health information-seeking, which might mask any potential relationship between smartphone addiction and health responsibility.

Limitations

This study has limitations. First, its cross-sectional design prevents assessing a causal relationship between smartphone addiction and health-promoting lifestyle behaviours; longitudinal studies are needed to clarify this association. Second, the study was conducted at a single university campus, which may limit the generalizability of the findings. Future research should include multiple universities and diverse student populations to enhance the reliability and applicability of the results. Third, the sociodemographic form was completed based on the respondents’ answers (such as BMI and sleep quality), which may have introduced bias or self-reporting errors, potentially leading to partiality in the results. Furthermore, a cross-sectional design may have inherent potential selection bias and temporal relationship limitations. Despite these limitations, this study contributes valuable insights into the relationship between smartphone addiction and health-promoting behaviours, addressing a gap in the existing literature.

Conclusions

Technological addictions, particularly smartphone addiction, have become a growing public health concern due to their increasing prevalence and associated negative social, psychological, and physical consequences. In this study, a remarkable percentage of university students were at risk for smartphone addiction. Factors such as female gender, absence of a partner, self-perceived smartphone addiction, poor sleep quality, and daytime sleepiness significantly contributed to this risk. Furthermore, smartphone addiction was associated with lower Health-Promoting Lifestyle Profile II (HPLPII) scores, especially in terms of physical activity, stress management, and spiritual growth.

Although smartphones offer many benefits, problematic usage patterns require further investigation. Future research should employ empirically designed studies using objective data to better understand the causal mechanisms underlying smartphone addiction. Young adults, who are particularly vulnerable to technological addictions, should be assessed and supported in developing healthier smartphone usage habits. Future studies should explore long-term health consequences and develop preventive strategies to promote a balanced and health-conscious approach to smartphone use.

Data availability statement

No new data were generated or analysed in support of this research

Author contributions

YS Writing – original draft and Writing – review & editing; GL Conceptualization and Writing – review & editing; ÖG Conceptualization and Writing – review & editing; NÖ Conceptualization, Supervision, Methodology, and Writing – review & editing.

Funding statement

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflicts of interest relevant to this work.