Introduction

Community engagement in research is widely regarded as essential to inform relevant research questions and study design, facilitate translation of evidence into practice, and advance health equity [1–Reference Macaulay, Commanda and Freeman3]. Expert groups have defined core principles of community engagement, including the 9 Principles of Community Engagement developed by the Clinical and Translational Science Awards (CTSA) Consortium’s Community Engagement Key Function Committee Task Force (Table 1) [1,Reference Gunn, Martinez and Battaglia4]. However, conducting community-engaged research can present challenges to both academic researchers and community members [Reference Forsythe, Ellis and Edmundson2], including community-based clinicians and health facility staff. There is growing interest in developing measures to evaluate the degree to which research activities align with community engagement principles [Reference Goodman, Sanders Thompson and Ackermann5–Reference Bowen, Ackermann, Thompson, Nederveld and Goodman8]. Nonetheless, community engagement remains infrequently measured in research projects. This limits opportunities to understand gaps, make data-driven adaptations, and identify strategies to successfully operationalize community engagement principles.

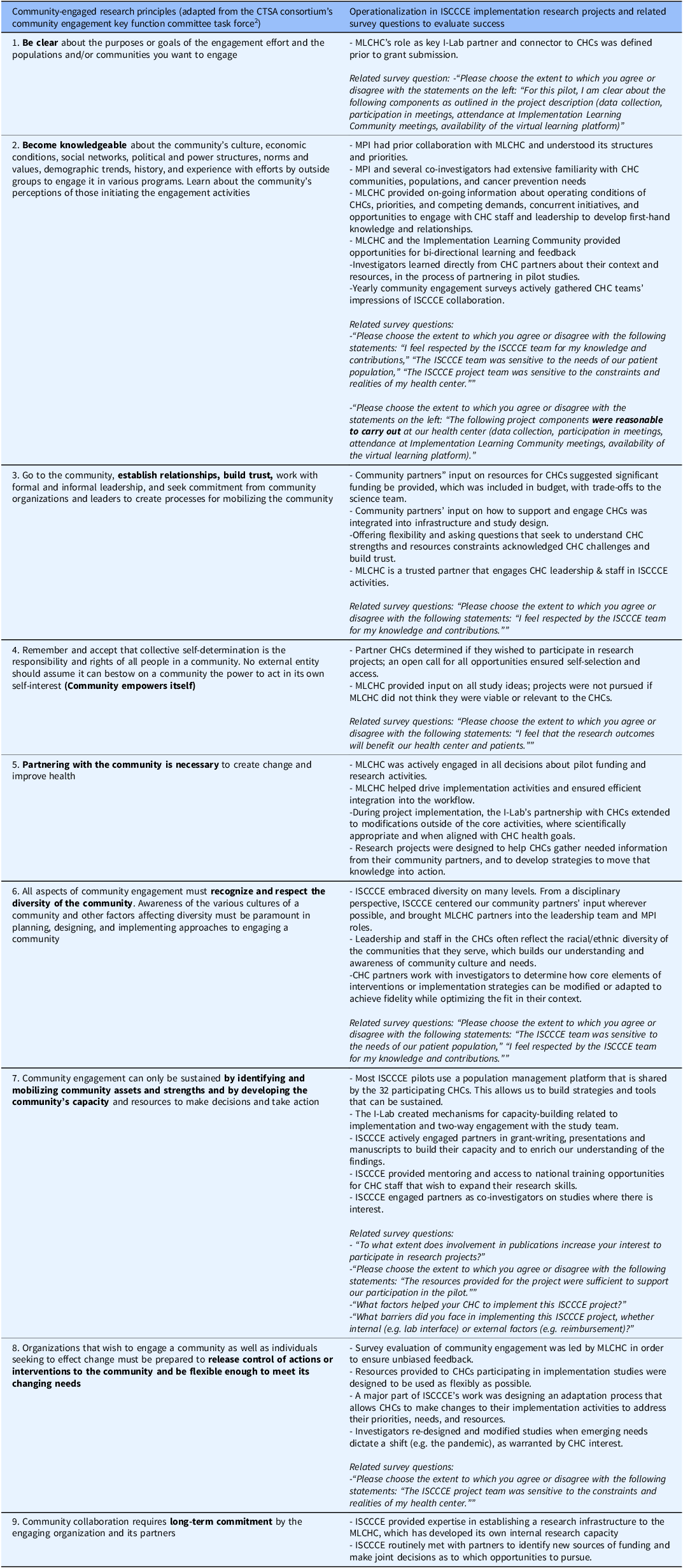

Table 1. Operationalization of community engagement principles in ISCCCE implementation research projects (adapted from Kruse et al1)

1 Kruse GR, Lee RM, Aschbrenner KA, et al. Embedding community-engaged research principles in implementation science: the implementation science center for cancer control equity. Journal of Clinical and Translational Science. 2023;7(1):e82.

2 CTSA Community Engagement Key Function Committee Task Force. Principles of Community Engagement. Task Force on the Principles of Community Engagement. https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/communityengagement/pdf/PCE_Report_508_FINAL.pdf. Published 2011. Accessed January 7, 2025.

ISCCCE = Implementation Science Center for Cancer Control Equity. MLCLC = Massachusetts League of Community Health Centers. I-Lab = Implementation Laboratory.

The Implementation Science Center for Cancer Control Equity (ISCCCE) was one of seven Implementation Science Centers funded by the National Cancer Institute from 2019–2024. ISCCCE was a partnership among the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, the Kraft Center for Community Health at Massachusetts General Hospital, and the Massachusetts League of Community Health Centers (MLCHC). A core component of ISCCCE’s model entailed collaborative pilot research projects engaging academic researchers and community health center (CHC) clinicians and staff [Reference Kruse, Lee and Aschbrenner9]. MLCHC played a critical role in ISCCCE leadership and was the primary liaison between academic partners and the CHCs. ISCCCE’s Implementation Laboratory (I-Lab) led research capacity-building activities and supported pilot project implementation at CHCs.

ISCCCE sought to embed in its work the 9 CTSA Principles of Community Engagement by articulating ways in which each principle would be represented in our work processes (Table 1). For example, we operationalized principle 7, “identify and mobilize community assets and strengths and by develop the community’s capacity and resources” in several ways in pilot project planning, including: (1) using a population management platform shared by the 32 participating CHCs as the basis of data collection; (2) actively engaging partners as co-authors on presentations and manuscripts to build their capacity and to enrich understanding of the findings; and (3) engaging interested CHC partners as co-investigators on studies [Reference Kruse, Lee and Aschbrenner9]. To evaluate the degree to which ISCCCE adhered to these principles and inform continuous improvement in engagement processes, MLCHC annually surveyed all research pilot participants from CHCs. This manuscript describes the results of this evaluation to provide insight into the successes and limitations of ISCCCE’s approach to community-engaged research. We anticipate that ISCCCE’s evaluation process may be a useful example for the growing number of institutions seeking to adopt and evaluate community-engaged approaches.

Materials and methods

Implementation research projects

Eight pilot implementation research projects were sponsored by ISCCCE from 2020–2024 to support CHCs’ adoption of evidence-based practices in cancer prevention and control, build sustainable implementation and research capacity at CHCs, and address cancer inequities in Massachusetts. From 2020–2023, each pilot was led by an academic investigator and involved 2–4 CHCs that chose to participate and received pilot funding to facilitate their participation. In 2023–2024, ISCCCE funded 2 pilot projects that were initiated and led by CHC-based investigators and implemented by CHC-based teams with ISCCCE administrative and methodological support as needed.

Example topics included bundling colorectal cancer screening outreach with social risk assessment [Reference Kruse, Percac-Lima and Barber-Dubois10] and piloting implementation strategies to facilitate smoking cessation and lung cancer screening. CHC staff played a range of roles – they co-developed the research projects, led adaptation of projects to their facilities’ and communities’ contexts [Reference Aschbrenner, Kruse and Emmons11], and oversaw implementation; they facilitated data collection, attended team meetings, presented results internally to other CHCs and externally e.g. at conferences, co-authored manuscripts, and partnered in additional funding applications. CHC staff were also encouraged to attend quarterly Implementation Learning Community (ILC) meetings. Organized by the I-Lab, the ILCs brought together CHC staff from across the state for 2-hour video conferences focused on cancer control equity, including sharing pilot project experiences. The I-Lab also developed a virtual learning platform (using Canvas) intended to facilitate communication about projects and support CHC capacity-building.

Survey development

The 9-item survey was co-developed by ISCCCE investigators and MLCHC based on CTSA principles (Table 1). Items examined CHC staff’s understanding of and satisfaction with different pilot project components, activities, and support offered. Degree of agreement was assessed using Likert scales. Respondents were asked two open-ended questions: 1) “What factors helped your CHC implement this ISCCCE project?”; and 2) “What barriers did you face in implementing this ISCCCE project, whether internal (e.g. lab interface) or external factors (e.g. reimbursement)?” Respondents were encouraged to share additional comments and suggestions for future research topics. Surveys took 10–15 minu to complete.

Survey recipients and administration

ISCCCE staff identified all CHC staff participating in ISCCCE-supported pilot projects.

MLCHC staff then administered the online survey via email to the identified CHC staff after completion of the pilot project period (typically one year) from 2021–2025. One to two email reminders were sent to non-responders.

Analysis

MLCHC shared pilot-level aggregate data from surveys with ISCCCE investigators. The ISCCCE team used descriptive statistics to analyze the quantitative data. For Likert scales, “agree” and “strongly agree” categories and “disagree” and “strongly disagree” were combined. Qualitative data from free-text responses were reviewed by 2 investigators and coded using a rapid qualitative approach with an Excel spreadsheet organized by survey question [Reference Kowalski, Nevedal and Finley12]. Coders summarized key takeaways for each question and collaboratively identified primary themes.

Ethics

The project was determined to be Not Human Subjects Research by the Harvard Longwood Campus Office of Regulatory Affairs and Research Compliance.

Results

Respondents

Surveys were sent to 59 pilot participants; 38 (64.4%) responded. Respondents represented a variety of CHC roles, including CHC leadership, quality improvement staff, clinicians, medical assistants, patient navigators, and lab personnel (Appendix Table).

Quantitative results

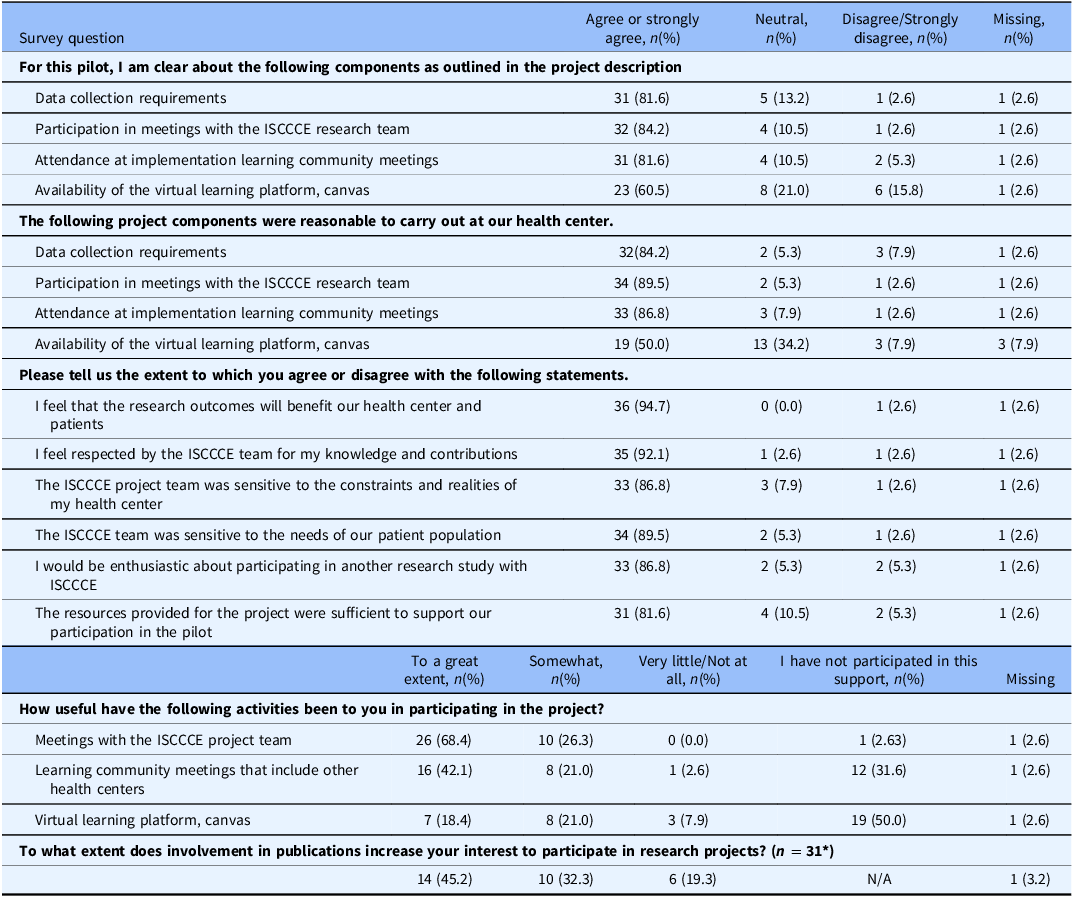

Table 2 shows quantitative survey results. Respondents were enthusiastic about the potential benefits of the research projects and the ISCCCE team’s respectfulness, contextual awareness, and flexibility (Table 2). Ninety-five percent of respondents agreed the research outcomes would benefit their CHC and patients, and 92.1% felt respected for their knowledge and contributions. Similarly, 86.8% felt the ISCCCE team was sensitive to their CHCs’ constraints and realities, 89.5% felt ISCCCE was sensitive to patient needs, and 86.8% would be enthusiastic about future ISCCCE research participation. Most (81.6%) felt resources were sufficient to support pilot participation. When asked whether they were clear about data collection requirements, 81.6% of participants agreed. Similarly, most respondents reported clear expectations for meeting participation (84.2%) and attendance at the ILC (81.6%). In contrast, only 60.5% were clear on availability of the Canvas virtual learning platform. When asked whether project components were reasonable to carry out at their CHC, 84.2% agreed; 89.5% felt that research meeting participation was reasonable, and 86.8% felt ILC participation was reasonable. In contrast, 50.0% felt that Canvas was reasonable to use. With regard to the utility of specific activities, team meetings were felt to be useful to a great extent for 68% of participants, and ILC participation for 42.1%. However, only 18.4% of respondents felt the Canvas virtual platform was useful. Most respondents were enthusiastic about participating in publications, with 45.2% noting that publication involvement increased their interest in project participation “to a great extent,” and 32.3% noting it increased their interest “somewhat.”

Table 2. Community health center staff responses to community engagement survey, 2021–2025 (N = 38)

* This question was only included in surveys in years 2–5.

Qualitative results

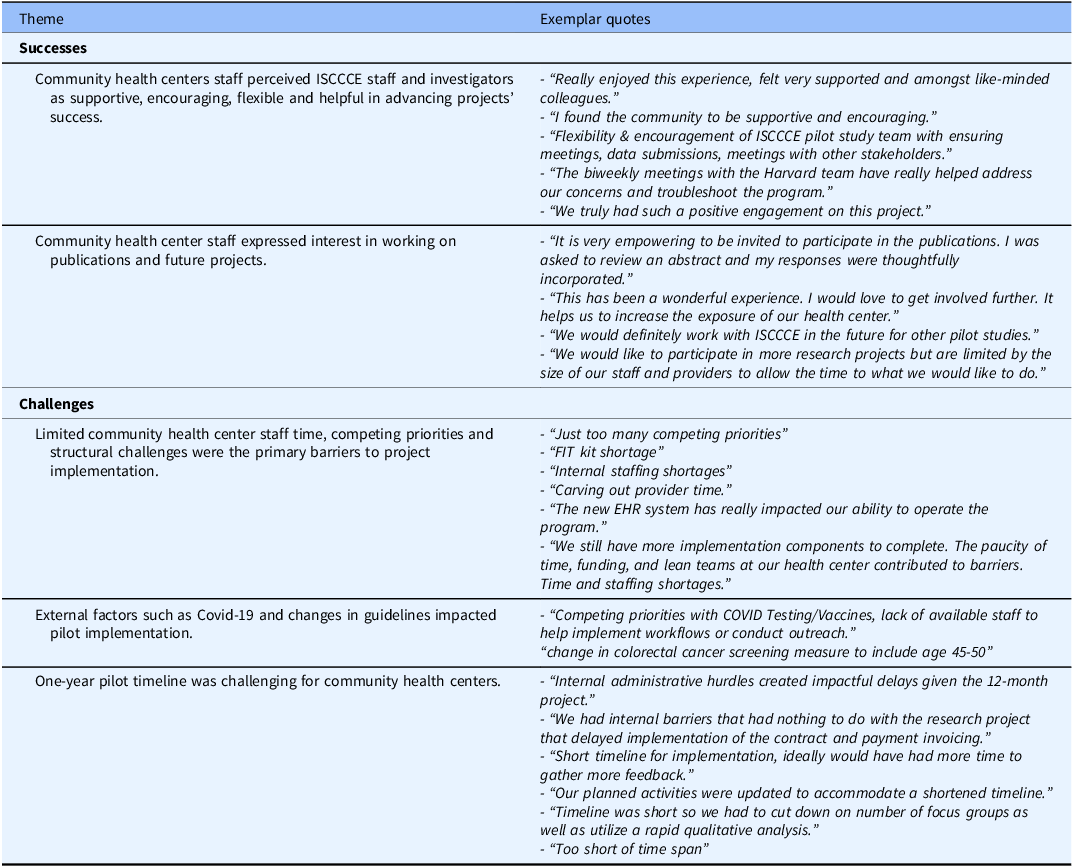

Themes identified in free text responses are shown in Table 3. Among successes of the collaboration noted by CHC participants, participants felt that their relationship with ISCCCE was positive and built on shared goals, with the ISCCCE team demonstrating flexibility and supportiveness. A second notable theme was that collaboration fostered an interest among CHC staff in being engaged in research in the future. Consistent with the quantitative results, respondents were enthusiastic about participating in publications and increasing CHC visibility. Participants described internal challenges to implementing the research projects at their CHCs, including competing priorities, limited clinician time, and limited resources (e.g. fecal immunochemical kit shortages for colorectal cancer screening). External factors such as the COVID-19 pandemic and cancer screening guideline changes presented additional challenges. Finally, respondents noted the difficulty of completing a project in a one-year timeframe, including due to administrative delays in setting up contracts with ISCCCE.

Table 3. Community health center staff responses to community engagement survey open-ended questions, organized by theme

Discussion

In this evaluation of pilot research projects entailing collaboration between academic investigators and CHC-based investigators and staff, CHC participants perceived their engagement positively. Most respondents felt that the collaboration adhered to community engagement principles in terms of ensuring clarity about and feasibility of project requirements, fostering trusting and respectful relationships between academic and CHC collaborators, supporting projects with benefits for communities and CHCs, and developing CHCs’ capacity for and interest in research.

Staff responses have helped ISCCCE prioritize activities that fostered positive engagement. The activity that the most respondents felt was useful were meetings with the ISCCCE team, suggesting that despite CHC staff’s inherent time constraints, meetings fostered collaboration and were felt to be productive. There was also high enthusiasm for the ILC, which brought together CHC staff from around the state. As a result, the ILC has been sustained after the end of ISCCCE’s grant funding through our CTSA Community Engagement Program. Publication interest was also notably high, encouraging investigators to prioritize inclusion of CHC partners in manuscript development. Over 90% of center publications had CHC partner co-authors [Reference Lee, Torres and Daly13]. CHC staff were less enthusiastic about the Canvas virtual platform initially envisioned as a communication tool, likely due to competing demands on their time and use of multiple other online systems for routine work. Thus, after 2 years, ISCCCE staff adapted the platform to be primarily a repository for study-related materials rather than a communication/ collaboration tool.

The most frequently identified barriers to project implementation were CHCs’ internal barriers, including staff time, and external factors such as the COVID-19 pandemic. Flexibility was built into ISCCCE’s structure and research processes, allowing investigators and CHC partners to collaboratively adapt projects in response to these inner and outer context factors [Reference Aschbrenner, Kruse and Emmons11]. Respondents also noted administrative challenges to operationalizing new contracts, despite ISCCCE’s deliberate efforts to streamline contracting processes. Projects with longer time horizons (>1 year) may be more feasible in settings that have burdensome research or financial approval processes and/or limited administrative staff.

This evaluation has several strengths. First, it contributes to a small literature evaluating the success of community engagement in research. Second, the evaluation survey was co-developed by community and academic partners and administered by community partners, who owned the data. This maximized questions’ relevance and helped the team adapt approaches in response to findings. Having MLCHC administer the survey may also have minimized acceptability bias and promoted participation. However, our evaluation has limitations. First, we did not formally validate the survey tool. A validated tool to assess stakeholder engagement, the Research Engagement Survey Tool (REST), was published in 2022, 3 years into our evaluation process, and has similarities with our approach. For example, REST is founded on community engagement principles and includes questions about respect for community partners and projects’ community benefits. The REST tool focuses on general adherence to the principles and was designed for a broad array of partners rather than specifically to CHCs [Reference Gunn, Martinez and Battaglia4], while our tool elicited concrete feedback about specific activities and suggestions for improvement. Combining these approaches could be valuable in the future, as long as tools remain concise and easy for community partners to complete. Second, our sample size was small, limiting the extent to which we could examine associations of specific engagement strategies with perceived engagement. Third, non-response bias may have affected our results, though our response rate of 64.4% was higher than many recent surveys of health care professionals [Reference Lee, Daly and Mallick14]. Finally, we surveyed participants at the end of one-year projects. More frequent assessments could allow more timely adaptations during project implementation. Reassessments over a longer time horizon would help evaluate the durability of a partnership.

In conclusion, this evaluation of an academic-CHC research partnership demonstrates the value of deliberate investment in operationalizing community engagement principles to facilitate partnerships’ success. It also underscores the importance of evaluating the degree to which research adheres to these principles in order to continually improve these relationships. In turn, productive partnerships may enhance the feasibility, acceptability, and effectiveness of research interventions.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/cts.2025.86.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge and appreciate the efforts of all participating community health centers.

Author contributions

Conception and design of the work: KME, GRK, SD-H, LP-C, and RML. Collection or contribution of data: LP-C, LSK, JD, MED, and SM. Contributions of analysis tools or expertise, conduct, and interpretation of analysis: MED, SM, and LEP. Drafting of the manuscript: LEP, MED, KME, GRK, RML, JD, MH, SD-H, LP-C, and LSK. LEP takes responsibility for the manuscript as a whole.

Funding statement

This manuscript was made possible with help from the ISCCCE, a National Cancer Institute-funded program (P50 CA244433). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Cancer Institute.

Competing interests

GRK has a family financial interest in Dimagi, Inc., a digital health company. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.