Introduction

In this chapter we analyse how racialised differences have been represented in artistic practice in Colombia, as well as the relationships between Black, brown and Indigenous artists and the art world. The first two sections of the chapter begin with a brief look at the colonial period and focus on the nineteenth century and the first half of the twentieth: for these periods we address the representation and participation of Black and Indigenous people. We take examples from visual arts and literature – plus music and dance for the early to mid twentieth century – as realms in which racial difference featured in readily identifiable ways. We show how white and mestizo artists tended to represent racialised subalterns in ways tinged with ‘primitivism’ and paternalism – although some displayed socialist sympathies in depictions of social inequality, in which such subalterns appeared as oppressed workers, without racism coming into clear view as a social issue.Footnote 1 However, by the 1930s and 40s, Black artists and writers were using their practice to critique social inequalities in which racism was identified as an important component. In the third section of the chapter, we turn our attention entirely to Black art practice – primarily music and visual arts, but also touching on oral literature and film – and we analyse its increasing politicisation from mid century, which was linked to international currents such as Négritude and Black Power. Also important was the burgeoning Black social movement in the country, which had incipient expressions in the late 1960s and gathered strength with Colombia’s 1991 constitutional reform and multiculturalist turn. The fourth section of the chapter focuses on the period since 2000 and explores the work of the Colombian artists – mostly but not exclusively Black – who collaborated with us in the CARLA (Cultures of Anti-Racism in Latin America) project; our aim is to show how their diverse art practices have addressed racism in increasingly direct ways.Footnote 2

From Colonial New Granada to Twentieth-Century Colombia

The focus of this section is on the way racial difference figured in the Colombian art world from the creation of the new republic in 1810 until the mid twentieth century, that is, during the long and varied nation-building processes that included the early establishment of key national institutions and a later period of modernising industrialisation and national integration. First, however, we briefly address the colonial antecedents of the relationship between racial difference and art (González Reference González2003).

If we look at visual arts, colonial artists were a rather heterogeneous group that included a small elite – who tended to be whiter – and a mass of artisans who did more routine work and tended to have more Indigenous and Black ancestry (Solano D. and Flórez Bolívar Reference Solano D. and Flórez Bolívar2012). Both types of artists worked mostly for the Church – creating paintings, carvings, sculptures – although some also did work (mostly portraits) for private clients. The artistic professions were regulated by guilds, and although Black, Indigenous and mestizo artists were members of artists’ guilds and confraternities (Rivas Pérez Reference Rivas Pérez2021), the status and prestige of these organisations were associated with the socio-racial quality of their members. Therefore, in the Spanish colonies there were certain tendencies towards ‘whitening’ in that artists with obvious Black and Indigenous ancestry might try to downplay or hide their socio-racial origins (Deans-Smith Reference Deans-Smith, Katzew and Deans-Smith2009). However, some mestizo artists were part of the elite, such as the Mexican painter Juan Patricio Morlete Ruiz – famous for his casta pictures, depicting diverse racially mixed types (castas) in the colony – who was a member of the Academia de San Carlos in New Spain. In New Granada (now Colombia), the well-known painter Salvador Rizo Blanco, a key member of the Expedición Botánica (1783–1816) and right-hand man of its director José Celestino Mutis, was of African descent (‘pardo’ or brown) and was in charge of purchasing enslaved people for the expedition.Footnote 3

After independence, the emphasis of elites in Colombia, as in other Latin American nations, was on establishing a national identity that could not only claim a degree of individuality and distinction – and political sovereignty – on the regional and global stage, but also demonstrate that it was moving towards the modernity associated with the world’s leading powers in Western Europe and North America. This created a certain contradiction in racial terms: ‘modernity’ as defined in the Eurocentric perspective of the time was associated with whiteness; whereas the nation’s distinctiveness arguably lay in its racially heterogeneous population, largely composed of Black, Indigenous and mestizo peoples who were defined as inferior by Eurocentric ideas steeped in scientific racism (Appelbaum, Macpherson and Rosemblatt Reference Appelbaum, Macpherson and Rosemblatt2003; Gotkowitz Reference Gotkowitz2011; Leal and Langebaek Reference Leal and Langebaek2010; Pérez Vejo and Yankelevich Reference Pérez Vejo and Yankelevich2017; Stepan Reference Stepan1982).

Part of this contradiction can be seen if we explore the visual art of the period: for example, the illustrations produced for the Comisión Corográfica, a scientific expedition that, in the 1850s, set out to take stock of the human and natural resources of the young nation of New Granada under the leadership of the Italian-born geographer Agustín Codazzi. Between 1850 and 1853, the Commission’s three artists produced more than 170 illustrations, of which two-thirds were done by the Colombian artist Manuel María Paz.Footnote 4

The images they produced were varied but were generally in the style that scholars have labelled costumbrista, romantic and sometimes dramatic, which was in keeping with the travel literature of the time (Acevedo Latorre, Saffray and André Reference Acevedo Latorre, Saffray and Francois André1968; Muñoz Arbelaez Reference Muñoz Arbelaez2010; Saffray Reference Saffray1948; Wiener et al. Reference Wiener, Crévaux and Charnay1884).Footnote 5 The majority of illustrations in the travel literature were crafted by artists who had never been to the country and who worked on travellers’ notes. But some travellers – among them the Spaniard José María Gutiérrez de Alba (Reference Gutiérrez de Alba2012) and the German Alexander Von Humboldt (Reference Humboldt1810) – and many Colombian artists, including the Commission’s artists, worked in the field and this informed their costumbrista emphasis on local life, generating many opportunities to represent racial diversity.Footnote 6 This was done in various ways.

For example, Ramón Torres Méndez (1809–1885) was a prolific painter who also taught the key Commission artist Manuel María Paz. He is usually classified as costumbrista, due to his focus on the working-class poor, both rural and urban, mainly in Bogotá. But his images are notable for the light colour of his subjects’ skin and their often European-looking features. Only rarely does he show Black people: for example, Champán en el Río Magdalena (Raft on the River Magdalena, 1860) shows the bogas (boatmen) as clearly Black.Footnote 7 Although his painting of Indios pescadores del Funza (‘Indian’ Fishermen of Funza) is the only one of sixty-three pictures to use explicitly racialised terminology in its title, his Mujer campesina de Gachetá en viaje (Peasant Woman from Gachetá on a Journey, 1860) shows a woman with markedly Indigenous features, while in his Jinetes de la ciudad y del campo (City and Country Horse Riders, 1860), the racialised dimensions of class difference are clearly visible.Footnote 8

In contrast, among the 480 images created by José María Gutiérrez de Alba (1822–1897), some thirty-five use the word indio in the title and five the word negro. Many more show regional scenes that include Black people, such as Lavanderas de Nóvita, Chocó, Cauca (Washerwomen of Nóvita, Chocó, Cauca, 1875) – actually copied from Vista de una calle de Nóvita (View of a Street in Nóvita, 1853) by Manuel María Paz, the Comisión Corográfica artist (see Figure 1.1). The same pattern applies to the 151 images from the Comisión Corográfica that have been archived: thirty-three images show Indigenous, Black and mestizo people, of which eight have titles with the word ‘mestizo’; twenty-two have the word indio; four have a word that explicitly refers to Blackness (negro, mulato, zambo, africano); and five are local scenes prominently featuring Black people, for example, Vista de una calle de Quibdó (View of a Street in Quibdó, 1853) and La marimba, instrumento popular: Provincia de Barbacoas (The Marimba, Popular Instrument: Province of Barbacoas, 1853).

Figure 1.1 Lavanderas de Nóvita, Chocó, Cauca (Washerwomen of Nóvita, Chocó, Cauca), painting by José María Gutiérrez de Alba, 1875.

Three things stand out in these images. First, Indigeneity is a much more prevalent theme than Blackness, doubtless because at that time Indigenous people outnumbered Black people (Smith Reference Smith1966), but also because Black people were seen as less important in the nation (Wade Reference Wade2010b). Second, both Indigenous and Black people are generally portrayed as poor and barefoot, usually in rural settings, an image that was strongly reinforced by the Commission’s texts, which established a clear socio-racial hierarchy associating whiteness with civilisation and non-whiteness with backwardness and primitiveness. Third, the images reflect the strong link between race and region that the Comisión Corográfica created, for example by depicting Black people as located mostly in the Pacific region (Appelbaum Reference Appelbaum2016; Restrepo Reference Restrepo1999). Overall, while Blackness and Indigeneity are by no means always invisible in these images, they are portrayed in stock and limited ways and there is no sense of a challenge to racial hierarchies.

Turning briefly to literature, we can see parallel trends. The paternalist way Black people were portrayed in Jorge Isaac’s romantic novel María (1867), set in pre-abolition New Granada, is often seen as costumbrista. Although slavery as an institution is decried in the novel, as it was in many Latin American nineteenth-century anti-slavery novels (Jackson Reference Jackson1975), enslaved people are portrayed as contented, well treated and passive. (This kind of romantic costumbrismo is an enduring feature: it appears as late as 1929 in Tomás Carrasquilla’s La marquesa de Yolombó, set in colonial New Granada.)

Quite different from the mainstream work of white writers was the poetry of the Afro-Colombian Candelario Obeso (1849–1884), which presented the worldview of the racialised subaltern classes of Colombia’s Caribbean coastal region, where Obeso was born and raised. In 1866, Obeso moved from his birthplace, Mompox, to study in Bogotá, where he joined the local literary circles; he also took up various jobs back in his native region, and in Panama and France. Although it had little impact at the time, the work that later became his best known, Cantos populares de mi tierra (Popular Songs from My Land, 1977 [Reference Obeso1877]), established the beginnings of a Black poetic tradition in Colombia, predating the better-known poetry associated with Hispanic-Caribbean poets such as Nicolás Guillen (Prescott Reference Prescott1985). George Palacios (Reference Palacios Palacios2010) argues that Obeso founded a ‘minor literature’, in which he challenged the dominant forms of Spanish language, attempting to convey the characteristic accent and modes of speech of the Black and mestizo inhabitants of his native region, as well as their everyday experiences. His poetry contested the social exclusion that they and he faced in Colombia, where the dominant imaginary represented Bogotá as ‘the Athens of South America’, which safeguarded ‘the purity of the language’, the ‘correctness’ of diction and the ‘enlightened vocation’ of its rulers, poets and orators (Jáuregui Reference Jáuregui1999: 574), and which depicted Obeso’s home turf as a backward territory (Múnera Reference Múnera1998). Obeso’s poetic mission claimed a legitimate space in the nation for Black people, thus subverting and reformulating the national project in ways that prefigure anti-racism.

Mid Twentieth-Century Colombia: Nation and Racial Diversity

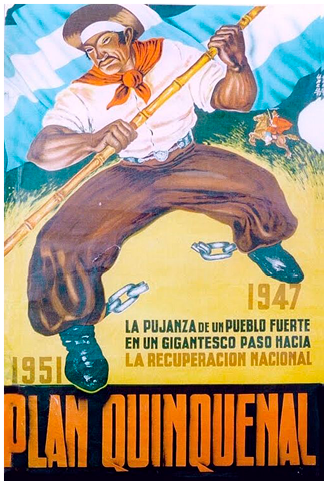

The 1930s and 1940s were marked by political projects of national integration and modernisation – based on expanding education and extending the reach of the state into the rural and urban working classes – and a corresponding artistic nationalism (Bushnell Reference Bushnell1993; Muñoz-Rojas Reference Muñoz-Rojas2022; Universidad Nacional de Colombia 1984; Uribe Celis Reference Uribe Celis1992). Underlying these political projects was the ideology of mestizaje (racial and cultural mixture), according to which Black and Indigenous peoples would gradually disappear into a mestizo majority. However, in this period, intellectual and cultural processes made visible what the ideology of mestizaje had hidden until then: the Indigenous and, especially, the Black presence in Colombian dance, literature, music and popular culture (reified as ‘folklore’ by scholars). There emerged a new socio-cultural consciousness marked by what is known as indigenismo, negrismo and Négritude, and various artistic-cultural expressions played an important role in redefining the meanings of what it meant to be Latin American, Black and Afro-Colombian, and in beginning to challenge racism.Footnote 9

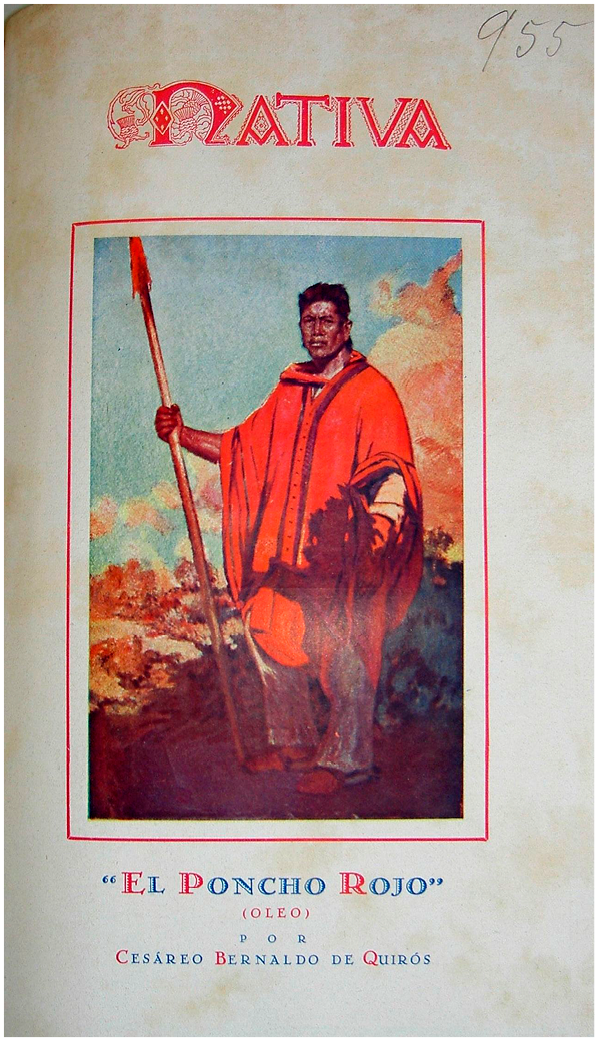

This period of national integration was expressed partly in artistic indigenismo, although never at the levels seen in Mexico and Peru. This artistic trend was driven almost entirely by white and mestizo intellectuals and artists, among whom challenging racism was not a priority. At this time, there was little Indigenous counterpart to the emergence of a cohort of Black intellectuals that, as we will describe, helped drive a parallel current of Négritude/negrismo, elements of which were alive to racial injustice.

Continuing with our focus on the visual arts, an example of indigenismo was the group Los Bachué, formed in 1930 by a group of left-leaning white and mestizo artists and writers (Troyan Reference Troyan2008).Footnote 10 The name alluded to the movement’s aspiration to represent Indigenous people and referred to a Chibcha goddess who had been depicted in a 1925 sculpture by Rómulo Rozo (1899–1964), a Colombian artist who became a Mexican national (Troyan Reference Troyan2008). A founding figure of the group was Luis Alberto Acuña Tapias (1904–1993), who produced paintings of ancient and mythical Indigenous figures, thus locating Indigeneity as Other and belonging to the past. Contributing to this sense of Otherness was the fact that Acuña sometimes depicted Indigenous people naked – for example, in his Bachué (1937) and Chibchakun, el que sostiene la tierra sobre sus hombros (Chibchakun, He Who Holds the Earth on His Shoulders, 1937).Footnote 11 Influenced by Mexican muralists, the Bachué group sought an inclusive national identity based on Latin American, not European, realities, while their leftist ideals of social justice underpinned support for Indigenous and working-class struggles. The search for authentic roots for the nation embraced not only Indigenous peoples but also peasant and mestizo populations – as imagined by the artists – for example, the sculptures Anciana campesina con pañolón (rasgos indígenas) (Old Peasant Woman with Headscarf [Indigenous Features], undated) and Muchacha campesina (Peasant Girl, 1950), both by Josefina Albarracín. While indigenismo was a predominant influence for the Bachué artists, there were a few representations of Black subjects: for example, the sculptor Hena Rodríguez produced Cabeza de negra (Black Woman’s Head, 1945).

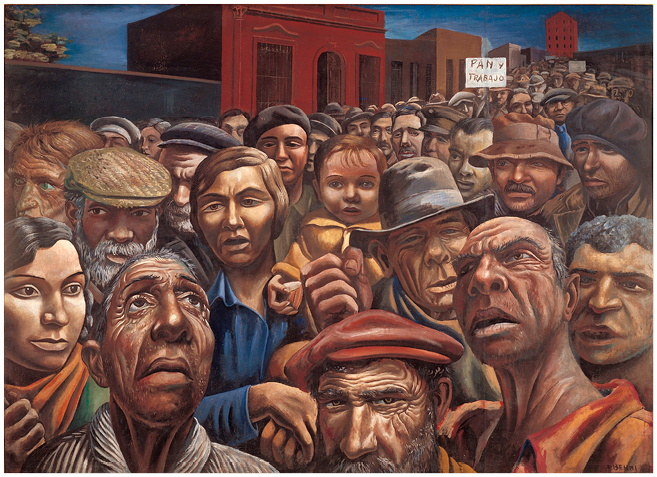

Cultural indigenismo was an influence on Pedro Nel Gómez (1899–1994), a visual artist renowned for his huge murals inspired by Mexican muralism and socialist thought (Gómez Reference Gómez2013). For example, in his vast mural La república (1937, 8 × 11 metres), adorning an entire wall of the Council Chamber in Medellín’s city hall, now the Museo de Antioquia, motherhood is represented by an Indigenous woman carrying her child (see Figure 1.2). The influence of the Mexican muralists on Gómez was evident in his attention to poverty, exploitation and displacement, with some attention to mining and its domination by foreign capital. But there is little direct attention to racial difference. The workers, miners and peasants he portrays in La república are phenotypically not very different, in a racialised sense, from the managers and professionals in the painting; the main difference is that the former categories are often shown semi-clothed or naked (like some of Acuña’s Indigenous figures), while the latter wear suits.

Figure 1.2 La república, mural by Pedro Nel Gómez, 1937

Figure 1.2 long description.

Figure 1.2Long description

The mural contains many overlapping scenes and people, including independence hero Simón Bolívar, ex-presidents López Pumarejo with a map of Colombia in his hands, Enrique Olaya Herrera, Pedro Nel Ospina, Marco Fidel Suárez, and Carlos E. Restrepo. Also shown are groups of peasant farmers, a group of artisanal miners by a river, and groups of protesters carrying banners with slogans such as “2,500 layers of mining subsoil no longer belong to the republic”. In one corner are John Bull and Uncle Sam, representing forces of foreign exploitation. In another corner, there is a scene from the 1928 massacre by the army of workers of banana plantations owned by the US company United Fruit in northern Colombia. In the foreground are many men in suits talking in groups, including one group around a table strewn with documents. In the background is an Indigenous woman holding a baby. The workers, miners, and peasants are shown semi-clothed or naked, while the managers and politicians wear suits.

The same cannot be said of the work of another muralist, Ignacio Gómez Jaramillo (1910–1970), who, like Pedro Nel Gómez, was influenced by Mexican muralism and socialism. Commissioned to paint murals to decorate the National Capitol building in Bogotá, he created La liberación de los esclavos (The Freeing of the Slaves, 1938) and La insurrección de los comuneros (The Rebellion of the Commoners, 1938), both referring to themes of social justice and featuring brown and Indigenous figures; La liberación also features many Black people, mostly semi-naked (Solano Roa Reference Solano Roa2013). Conservative elements in Colombia were highly critical of the murals of both Gómez Jaramillo and Nel Gómez for their depiction of nudity and for their supposed lack of artistic value, but also for their socialist tendencies. It is not clear to what extent the murals’ reference to the racialised character of social injustice was an element in the conservative reaction. But murals by Gómez Jaramillo were plastered over in 1948 and some of those by Nel Gómez covered with curtains in 1950, to be uncovered only in the late 1950s when the political context was more liberal.

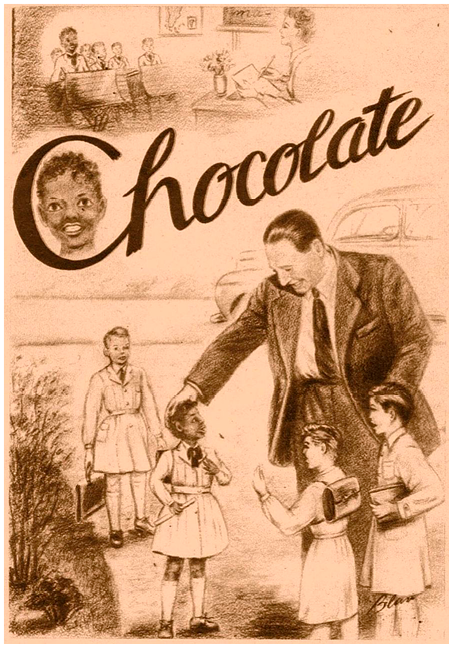

If racial injustice was not a theme in indigenismo and was of uncertain status in these murals, it got more of an airing by the Black artists of this period – mainly writers, dancers and musicians. However, this airing was an ambivalent part of a Colombian version of the Spanish Caribbean literary negrismo, which emerged at this time, the product of two processes. The first was the growing number of Black intellectuals from the Caribbean and Pacific coastal regions and the Cauca Valley, many of whom migrated to the big cities for education. The second trend was the often paternalistic acceptance by white and mestizo intellectuals of elements of Black artistic expression, which were treated in a romanticised manner that aligned with negrismo and international trends in artistic primitivism (Price Reference Price2001). Much of this was reflected in the national popularity of musical styles associated with the Caribbean coastal region, such as cumbia and porro, which, despite being subject to some cultural whitening as they became commercialised, did not entirely lose the Black symbolism that was, in fact, central to their popular appeal (Wade Reference Wade2000).

Some of the romantic and objectifying tendencies associated with negrismo were also evident in visual art, where primitivist perspectives were also prominent. Mulata cartagenera (Mulatta from Cartagena, 1940) by the painter Enrique Grau (1920–2004, born in Panama) is a realistic depiction of a sexualised Black woman, although it is not typical of his work.Footnote 12 The painting’s realism and subject matter made an impact and it received a mention at the Primer Salón Nacional de Artistas Colombianos (First National Colombian Artists’ Salon) in 1940, an achievement for a Caribbean painter realistically depicting a Black woman. The painting raised the profile of Blackness as a vibrant element in the nation. However, in terms of combating racism, it can be argued that this type of painting reproduced stereotypically sexualised images of Black women.

In the realm of literature, some Black writers from both coastal regions eschewed the paternalism and primitivism associated with negrismo. Writers from the Pacific coast region included Arnoldo Palacios (1924–2015), born and raised in the province of Chocó, who moved to France in 1949 and lived there until his death. In the novel Las estrellas son negras (The Stars are Black, 2010 [Reference Palacios1949]), set in Quibdó, the provincial capital of Chocó, he described the psychological damage caused by racism and, unusually for the time, established a direct correlation between US and Colombian forms of racism (Pisano Reference Pisano2012: 95). The novel and its powerful social critique were largely ignored in Colombia until the Ministry of Culture published a third edition in 1998. Something similar happened with Carlos Arturo Truque (1927–1970), also from Chocó, who, in short stories written in the 1950s, used a social realist style to present the lived realities of the racialised subaltern classes of his region (Truque Reference Truque1993). Truque was also mostly ignored until the 1990s. In the 1950s, too, the Chocoano poet Hugo Salazar Valdés (1922–1997) was appointed director of the magazine of the Teatro Colón, deputy director of the National Library and head of the cultural outreach programme of the Ministry of Education. Laurence Prescott (Reference Prescott and Ortiz2007: 145) states that Salazar’s poems are a testimony to ‘the struggle of the Blacks of the Pacific for a dignified life within Colombian society’.

Writers from the Caribbean coastal region had a greater impact; in the 1960s this was amplified by the enormous influence of Gabriel García Márquez, whose writings made famous a magical realist image of the region, even if this muted its racial Blackness (Bryan Reference Bryan1988). Blackness was more evident in the poetry of Jorge Artel (1909–1994), who was born in Cartagena and continued to be based in the region until his death, apart from travels in the Americas between 1949 and 1971; in 1940 he published Tambores en la noche (Drums in the Night). However, Jacques Gilard (Reference Gilard1986: 41) characterised his poetry as displaying a ‘very conventional negrismo’: by making frequent references to music and dance, he evoked a sensual rhythmicity for his native region (Prescott Reference Prescott2000).

Rather different were the siblings Manuel, Delia and Juan Zapata Olivella (1920–2004, 1926–2001 and 1927–2008, respectively), also of Caribbean coastal origin, who devoted themselves to literature, music, dance, visual arts, activism and party politics for many decades – all supported by cultural and historical research. Manuel and Delia Zapata Olivella radically contested the prevailing version of mestizaje as a process of whitening the nation, seeing it instead as a force for real, but as yet unrealised, democracy (Jackson Reference Jackson1988; Viveros Vigoya Reference Viveros Vigoya, de Benavides, Castro-Gómez and Vásquez2013). They affirmed the value of Black and Indigenous cultures and drew attention to racism in the country. Manuel conducted research on Afro-Colombian culture and mestizaje and brought musicians from his native region to Bogotá, but he channelled his efforts mainly through his literary work, which achieved national and international fame. An early example was Chambacú, corral de negros (Chambacú, Corral of Blacks, 1967 [Reference Zapata Olivella1963]), which challenged Cartagena’s racist order by giving a socially realist depiction of life from the perspective of Black people in a marginalised neighbourhood in the city (Ortiz Reference Ortiz2007).

Meanwhile, Delia published articles in magazines and journals such as Páginas de Cultura, Colombia Ilustrada, Revista Colombiana de Folclore and Revista de Etnomusicología; she also researched and taught traditional artistic expressions of the Caribbean and Pacific regions at the Instituto Popular de Cultura in Cali (Valderrama Reference Valderrama2013), while her dance company, Danzas Folklóricas Colombianas, toured nationally and internationally. Delia’s research in what was known as folklore – a category rooted in European traditions in which urban elites studied subaltern rural people (Muñoz-Rojas Reference Muñoz-Rojas2022) – went beyond ‘the reification, collection, preservation and classification of traditions and cultural practices of Afro-Colombian peoples’, traits characteristic of a costumbrista, positivist and romantic vision of folklore research (Valderrama Reference Valderrama2013: 271): she sought to make visible the relationship of her work with her African roots and with racial inequalities (Valderrama Reference Valderrama2013: 267), even if, at the time, acknowledging African ancestry meant risking a loss of prestige (Prescott Reference Prescott1996: 111).

Art practice, research and anti-racist activism went together in the work of Delia and Manuel. With other Black students living in Bogotá, they participated in the organisation of the Día del Negro (Black People’s Day) on 20 June 1943, in solidarity with protests against the lynching of Black trade unionists in Chicago, but also highlighting the lack of freedom and equality of the Black Colombian population. On this occasion, poems by Obeso and Artel were recited and cumbia was danced. Manuel was a founding member of the Club Negro (1943) and the Centro de Estudios Afrocolombianos (1947) which, despite being ephemeral, had a great influence on the discussions and debates taking place at the time, linking them to the questions being asked by Black peers in other regions about race, identity and imperialism. At the same time, these organisations were strategic spaces for affirming the place of Afro-Colombian values and cultural manifestations in the national imaginary and for challenging the racism of Colombian society and its image as a potentially inclusive mestizo nation (Pisano Reference Pisano2012; Wade Reference Wade2016). These Afro-Colombian intellectuals pointed out that the yardstick by which ‘racial prejudice’ and ‘discrimination’ were being assessed at the time was misleadingly determined by a comparison with race relations in the segregationist United States; and they deployed notions of equality and democracy that had in fact been advocated by Afro-Colombians since the early days of the republic (Lasso Reference Lasso2007).

The work of constructing Black identity was evident in other research that sought to revalue Afro-Colombian lifeways and led to the emergence of an Afro-Colombian counter-public in which questions of racism and Black/Afro identity were discussed (Valderrama Reference Valderrama2018). Folklorists and artists from the Pacific region, such as Mercedes Montaño (1912–1999), Margarita Hurtado (1918–1992) and Teófilo Potes (1917–1975), as well as Lorenzo Miranda (1935– ) from Palenque de San Basilio in Colombia’s Caribbean region, shared with Delia and Manuel Zapata an interest in researching and promoting Afro-Colombian music, dance and oral traditions, and in using their work to denounce racism in Colombia (Arboleda Quiñónez Reference Arboleda Quiñónez2011; Valderrama Reference Valderrama2018). This work ran alongside the more academic efforts of Black anthropologists such as Rogerio Velásquez (1908–1965) from Chocó and Aquiles Escalante (1923–2002) from Barranquilla, who began to turn Black communities into a topic of interest for anthropology. Other artists and cultural promoters from the Pacific region, such as the poet Benildo Castillo, the dancer and singer Alicia Camacho Garcés and the musician Petronio Álvarez, made other forms of knowledge visible, channelling them into various artistic genres.

These artists and researchers contributed to the strengthening of Black cultural identity in Colombia. Long before the formal recognition of Afro-Colombians as an ethnic group in the 1991 constitutional reform, their various contributions articulated their understanding of ‘folklore’ as part of a political struggle to resignify the cultural representation of racialised subaltern groups. Afro-descendant music and dance (recognised as also bearing Indigenous influences) – long seen from a dominant perspective as an object of shame and evidence of racial inferiority and moral inadequacy – was finally being positively recognised as valid cultural expressions, and this was an important achievement for the Afro-descendant community, redefining their existence beyond their physical characterisation.

To summarise thus far: we have shown that artistic reference to racial difference took various forms. In the hands of state agents, it could be allied to projects of cartography and governance; in the hands of white and mixed-race intellectuals, it could have elements of primitivism and paternalism, but could also be aligned with a socialist emphasis on social equality, in which dark-skinned and Indigenous people figured as oppressed workers, without racism itself being identified as a problem; in the hands of Black artists and writers, it could be harnessed to critiques of social injustice in which racism was understood as an integral element.

The Politicisation of Black Artistic Practice

In the second half of the twentieth century, the Afro-Colombian diaspora continued to weave networks and build common spaces around culture, generally in central Andean cities and mainly in Bogotá. From the 1960s onwards, political organisations emerged in communities of Black migrants to the Andean cities, focusing on questions about the ‘racial condition’ of Black people and ‘their participation in the construction of the country’ (Arboleda Quiñónez Reference Arboleda Quiñónez2011: 162). In 1975, the Primer Encuentro Nacional de la Población Negra Colombiana (First National Meeting of the Colombian Black Population), held in Cali on 21–23 February, brought together 183 delegates from across the country to discuss the political and social problems of people of African descent (Wabgou et al. Reference Wabgou, Rodríguez, Cassiani and Ospina2012: 99). This led to initiatives to promote affirmative action in education, denounce racism and defend ethnic rights in the political sphere, which continue to be at the centre of Afro-Colombian organisational processes.

Two years later, the organisers of the Primer Congreso de Cultura Negra de las Américas (First Congress of Black Culture of the Americas), which took place in Cali, Colombia, in 1977, described the conference as undertaking ‘a double task in the battle against neo-colonialism: education and politicisation at the same time’ (Valero Reference Valero2020: 48). They sought to promote strategies for awareness-raising and change for Colombian Black communities through cultural practices. While some panels in the Congress discussed the need to decolonise art and aesthetics in order to produce their own cultural forms, others pointed to the lack of Black intellectual and cultural reference points as a manifestation of racism. During this congress and the subsequent ones in Panama (1980) and São Paulo (1983), Black culture emerged as ‘fuel for Négritude as ideology’ (Arboleda Quiñónez Reference Arboleda Quiñónez2011: 192): that is, as having an eminently political character and being a contested field for the definition of Black identity (Valero Reference Valero2020).

For Santiago Arboleda Quiñónez (Reference Arboleda Quiñónez2011), Carlos Valderrama (Reference Valderrama2013, Reference Valderrama2018) and Francisco Flórez Bolívar (Reference Flórez Bolívar2015), the cultural consolidation of this period is what made possible the first organised political expressions of Black culture and identity. This occurred in conversation with events in the United States, where, between 1968 and 1975, African American activists were putting into global circulation concepts such as ‘Black power’ and ‘Black is beautiful’, promoting racial pride and the creation of cultural and political institutions around the cultural expressions of Black communities (Arboleda Quiñónez Reference Arboleda Quiñónez2011: 158; Laó Montes Reference Laó-Montes, Rosero-Labbé, Laó-Montes and Rodríguez2010: 294). This had a great impact on Afro-Colombian youth, who appropriated these concepts to legitimise their positions as political subjects. Referring to an Afro-Colombian cultural renaissance, Arboleda Quiñónez (Reference Arboleda Quiñónez2011: 206) mentions the example of the ‘cultural front of southern Valle [province] and northern Cauca [province]’ which, in the late 1970s and the 1980s, held meetings that not only consolidated their relations but also led to the questioning of Eurocentric aesthetic canons that devalued Black cultural and artistic expressions.

During this period, thinkers, artists and cultural promoters came together around local festivals, such as those in Palenque de San Basilio and Tumaco, to showcase Black and Afro-Colombian culture, still considered exotic by mainstream audiences. In 1987, the first Festival of Currulao (a Pacific-region music genre) was held in Tumaco – it still exists today, despite economic limitations – bringing together music, theatre, dance and oral literature, as well as cultural promoters interested in Afro-Colombian artistic production. In the same year, the Green Moon Festival was born on San Andrés Island under the slogan ‘a fraternal embrace in the form of race and culture’, showcasing the music, cinema, gastronomy and religious and sporting expressions of San Andrés communities and of the Creole culture of the English-speaking Caribbean. A year later, in 1988, the first Encuentro de Literatura Oral del Pacífico Colombiano (Meeting on Oral Literature of the Colombian Pacific) took place in Buenaventura, organised by the poet and writer Alfredo Vanín Romero under the slogan ‘So that the people do not lose their memory’. Approaches like these express the emerging awareness of the importance of oral tradition – and, ironically, the need to register it in literary form (see, for example, Vanín and Pedrosa Reference Vanín and Pedrosa1994) – as a counter-hegemonic version of official history, or as ‘history that does not grow old’, in the words of Manuel Zapata Olivella (Reference Zapata Olivella1983). This perspective allowed the bringing together of ‘scattered pieces of Afrodiasporic thought, which allowed people to collate and contrast versions, maintaining their diversity, but above all to elaborate new meanings of the past, the present and the future, based on these other sources of history’ (Arboleda Quiñónez Reference Arboleda Quiñónez2011: 207).

The reform of the Constitution in 1991 brought with it the recognition of a ‘multicultural and pluriethnic’ identity for the country and of Black communities as an ethno-cultural group (Political Constitution of Colombia, 1991, Art. 7). In this new context, legislation was also created that addresses culture and ethno-cultural diversity as elements for the achievement of peace: Law 70 of 1993, based on collective ownership of land, a fundamental principle of Black culture in the Colombian Pacific region; a 1993 law establishing a Ministry of Culture to manage state cultural policies; and the General Law of Culture of 1997, which specifies the uses of cultural expressions in cultural policy, including to mitigate violence.

These reforms led to a new inclusion of Afro-Colombian culture, and particularly music, in some spaces of the cultural market. An example is the growing presence in popular music of elements from the Pacific region and the proliferation of groups that have taken up the music of that region, which for a long time, unlike Caribbean music, had been rejected as being linked to primitive atavism and the incapacity to progress (Wade Reference Wade2000). In recent years, this music has featured in state cultural programmes and policies and is present in events such as the Petronio Álvarez Festival of Pacific Music, which has been held in Cali since 1997, and the Green Moon Festival, which was revived in 2012. At the same time, some musicians have fused the musical legacy of the Pacific, the traditional genres of the Caribbean and the native music of San Andrés with elements of contemporary urban music, creating sonorities that are both global and rooted in local traditions.

The new multicultural policies have sought to mobilise traditional music, including Afro-Pacific music, to combat violence in the country, although ironically ‘the emergence of multiculturalism was closely linked to the intensification of violence in the country’ (Birenbaum Quintero Reference Birenbaum Quintero2006: 14). However, the display of Afro-Pacific music on state stages in order to ‘make our essential affinities prevail over our passing differences’ – in the words of President Samper (Birenbaum Quintero Reference Birenbaum Quintero2006: 15) – has demanded its spectacularisation. Consequently, local aesthetic logics have been eclipsed, separating musical practices from their ritual functions, and conditioning their recognition to a certain domestication of their differences in order to affirm what Samper called ‘shared characteristics’ over and above the ruptures implied by the relations of enslavement and exploitation to which Black populations of this region were subjected.

Another example of this new Afro cultural presence on the national scene is the surprising national recognition in the new millennium of champeta, a musical genre from Colombia’s Caribbean region, previously stigmatised with racist stereotypes and seen as breaking conventions of propriety (Cunin Reference Cunin2003). Indeed, in 2001, Sony released a CD with a telling title: La champeta se tomó a Colombia (Champeta Has Taken Over Colombia).

Afro music, in all its diversity, because of its association with ‘escape’ or cimarronería in the face of Western hegemonic values, has gradually become a resource for political mobilisation that brings together various social causes.Footnote 13 Ángel Quintero (Reference Quintero2020) argues that the freedom and spontaneity of Afro rhythms and dance, as well as their dialogical and heterogeneous character, can be dissociated from stereotypical imaginaries and used to foment a new type of anti-individualist sociality. We could say that these musical practices deconstruct sense conventions, deploying sentipensamiento (feeling-thinking) in an integrated way that is far removed from Eurocentric aesthetic norms that tend to separate feeling from reason. This gives them an anti-racist potential insofar as they allow an embodied and integrated apprehension of the effects of racism and create a sense of community through sharing these music and dance expressions. However, it is worth remembering that this potential can best be developed in relative freedom from the hegemonic discourses of multiculturalism and the neoliberal logic of cultural policies that instrumentalise these musical practices as ‘technologies of peace’ and make citizens responsible for reducing violence (Ochoa Reference Ochoa Gautier2003).

Turning to the visual arts, in contrast to what happened in literature, music and dance, it was not until after 1950 that the first representations of Afro-descendants by Afro-descendant artists were produced, marking a transition from being objects to subjects of representation. One of the first Afro-descendant artists to follow this path was the painter Heriberto Cogollo, who was born in Cartagena in 1945 and has lived mostly in France since 1966. He was one of the members of the renowned Grupo de Los 15, a group of artists at the School of Fine Arts in Cartagena which, between the 1950s and 1960s, proposed disruptive artistic initiatives in the local art scene.Footnote 14 Cogollo, who is no stranger to ‘revealing his own identity’ and his African roots, inspired by his contact with Europe and North America (Obando Hernández Reference Obando Hernández2018: 104), began in the 1970s to do research on aspects of the body and spirituality that masterfully express the difference between looking at the complexity of the African physical and spiritual body from the outside and from the inside.Footnote 15 Despite being a renowned artist with an extensive international career, he was until recently largely unknown in Colombia.

In the new millennium, we find references to the Black presence in the Colombian visual arts in various publications: Nuestros pintores en París (Our Painters In Paris) (Mendoza, Gómez Pulido and Jordán Reference Mendoza, Pulido and Jordán1989), with a chapter devoted to Heriberto Cogollo; El arte del Caribe colombiano (Medina Reference Medina2000); the essay ‘La imagen del negro en las colecciones de las instituciones oficiales’ (The Image of the Black Person in Official Institutional Collections) by Beatriz González (Reference González2003); and the curatorship of the exhibition Viaje sin mapa: Representaciones afro en el arte contemporáneo colombiano (Journey without Maps: Afro Representations in Contemporary Colombian Art) by Raúl Cristancho and Mercedes Angola (Reference Cristancho Alvarez and Angola2006). This exhibition was ‘A first approach to the visualisation and positioning of contemporary plastic [arts] production in Colombia’ (Cristancho and Angola Reference Cristancho Alvarez and Angola2006: 2) and it marked an important milestone in the history of Afro-Colombian art by breaking the silence about Afro-descendant artists and by highlighting how the mainstream politics of representation in modern art have been shaped by the cultural hierarchies of the Colombian socio-racial order. The curators brought together a generation of artists who were beginning to work with a clear awareness of being subjects of their own representation – among them Liliana Angulo Cortés, Fabio Melecio Palacios Prado and Lorena Zúñiga.Footnote 16 Liliana Angulo Cortés has explored photography, installation and sculpture, and has worked with archives that reveal the power relations structuring visual representations, territorial control, constructions of masculinities, and the way power is inscribed in the bodies of Black women. Using exaggeration, parody and exoticising stereotypes, she has denounced the violence to which Afro-descendants are subjected (see Figure 1.3). She has also curated various exhibitions that reflect on the collective and personal meanings of Blackness in Colombia, and on the history of hopes, desires and resistances related to processes of racialisation (Viveros Vigoya Reference Viveros Vigoya2021).

Figure 1.3 One of nine images from the series Negro utópico by Liliana Angulo Cortés, 2001

In 2013, the exhibition ¡Mandinga sea! África en Antioquia (Goddammit! Africa in Antioquia) (Maya Restrepo and Cristancho Reference Maya, Adriana and Cristancho2015) continued this exploration of the presence of Afro-descendants in Colombian art, their role and the ways they have been represented and have represented themselves.Footnote 17 This exhibition included artists such as Heriberto Cogollo, Fabio Melecio Palacios and Liliana Angulo Cortés. Younger artists also featured, such as Fabio Arboleda, a painter, musician and rapper who draws on the language of graffiti to portray Afro-descendant urban subcultures; Lloreida Ibargüen who, in her work Trabajo de negro (Black People’s Work), translates mining work to the present day, showing the bodies of construction workers – of which her father was one – for whom ‘urban tunnels are substitutes for the old mining tunnels’; and Servando Palacios, who uses self-portraiture and elements of clothing fashion from Afro-Colombian popular culture to explore, embody and question different facets of Black identity (Maya Restrepo and Cristancho Reference Maya, Adriana and Cristancho2015).

Likewise, after thirty years of state multiculturalism, changes are beginning to occur for the first time in the audiovisual sector in relation to the Afro-descendant population as a subject for a new generation of women and men who work individually and collectively, contributing to the current dynamism of Afro-descendant artistic practices. Some of the collective processes have been developed by Afro-Colombian organisations. Thus, the Corporación Afrocolombiana de Desarrollo Social y Cultural (Afro-Colombian Corporation for Social and Cultural Development, CARABANTÚ), with the support of the Centro Popular Afrodescendiente (Afro-descendent People’s Centre, CEPAFRO), in 2014 developed the Kunta Kinte Ethno-Educational Afro Film and Video Showcase, which in 2016 became the International Kunta Kinte Afro Community Film Festival. Its objective was to create an ethno-educational film forum to critically analyse the situation of human rights, racism and territoriality of Afro-descendant communities, and the implications for community life in Medellín. The showcase also sought to promote reflection on and recovery and strengthening of Afro-Colombians’ historical-ancestral roots in all their diversity.

To date, nine editions of Muestra Afro (Afro Showcase), exhibiting Afro-Colombian audiovisual art and film, have taken place, most recently in November 2024.Footnote 18 The 2021 version, organised by Bogotá’s Cinemateca and the collective Wi Da Monikongo (the Afro-Descendant Audiovisual Council of Colombia, created in 2017 and present since 2018 in the Muestra Afro showcases), emphasised the spaces for participation and training that dialogue around Afro-diasporic audiovisual, cinematographic and artistic expressions, in particular Afro-feminist and Afro-futurist filmmaking.Footnote 19 These showcases made visible and strengthened the participation of people working in the Afro audiovisual sector in Colombia and articulated this with global Afro-diasporic production.

Through varied tactics and aesthetic techniques, the artistic-cultural processes described in this section have radicalised the constrained form of self-recognition offered by multiculturalism and have renewed the arts scene with projects that seek to combat racism. For Black people, self-representation has meant opposing the imposition of an official history that has ignored or stereotyped their performances and cultural productions; creating, recreating and resignifying Colombian Black history and culture in all its polyphony, based on their own experiences and with their own aesthetic resources; struggling to acquire social agency and political and cultural representativeness within Colombian society; in other words, using their collective creative power to denounce, to criticise and to think of alternative ways of ordering the world. These kinds of projects have blurred the increasingly indiscernible frontiers between activism and art, generating a kind of transterritoriality, in which the creative power of activist practices and the politics of artistic practices with their micropolitical resistance have been mobilised, disrupting the dominant meanings and the sensory organisation of the Colombian socio-racial order.

Artistic Practices and Anti-Racist Strategies

In this section, focusing on the Colombian artists with whom we collaborated in the CARLA project, we analyse how the dominant political climate in Colombia since about 2005 has made the articulation between art and activism more evident and given greater visibility to anti-racist art practice. During this period, a far-right political tendency, promoted by the political forces of Uribism, implemented a form of governance based on maximising ‘security’ and encouraging foreign capital, which was oriented towards extractivism, corporatism and the privatisation of public goods.Footnote 20 This reaffirmed mechanisms of political and legal control, while also introducing new forms of criminality and violence perpetrated by state actors and their proxies at levels from the regional to the highest spheres of government.

As a consequence, social conditions, in terms of human rights protection and the satisfaction of basic needs, became notoriously precarious in the country. The governance involved new technologies of violence and forms of necropolitics (Mbembe Reference Mbembe2003) that multiplied the actors involved in the conflict and resulted in the violent displacement of small-scale agriculturalists from their lands and, to a disproportionate extent, of Afro-descendant and Indigenous populations from their territories, contributing to a deterioration of their living and working conditions in both rural and urban areas (Palacios Valencia and Mondragón Reference Palacios Valencia and Mondragón2021; Vergara-Figueroa Reference Vergara-Figueroa2017).

From the 1990s, artistic practices in Colombia had already been undergoing incipient changes in their forms of circulation and expression, their spaces of creation, their social commitment and their strategies for engaging audiences. For example, there was a shift from the private sphere and a search for individual aesthetics to what María Margarita Malagón-Kurka (Reference Malagón-Kurka2010) terms ‘indexical art’, which engaged overtly with themes of politics, trauma and violence, and involved artistic processes that were more collective, participatory and community-based. Abstraction gave way to everyday references, accessible to wider audiences. The works of Fabio Melecio Palacios and Liliana Angulo Cortés, mentioned earlier, are outstanding examples of how the violent and racialised social order began to be questioned critically on the basis of everyday experience. Overall, the period from 2005 to the early 2020s was notable for its prolific collective artistic projects committed to social transformation, not only of Afro representation in art, but also of the value attached to the artistic practices of Afro and other non-white populations in Colombia.

In this context, which moved from a critical framing of the representation of Blackness to a much broader questioning of racism and the legacies of colonialism in Colombian society, artists from various disciplines, self-identifying mostly as Afro-descendants but some also as mestizos, converged on a series of projects and collaborations characterised by their anti-racist orientation and strong commitment to social justice. Their unifying premise is that artistic practice plays a crucial role in dismantling manifestations of racism in racialised social orders. Furthermore, these artists pose questions to audiences about Afro otherness in Colombia, no longer only from the location of the rural Black community but also from urban contexts.

One example of this collaboration around anti-racist artistic work is Colectivo Aguaturbia, consisting of Afro-descendant artists and cultural agents. In 2016, this collective organised an encounter of artistic practices under the title IRA (Imaginación Radical Afro), which brought together visual arts, animation, audiovisual production and performances in the city of Bogotá. The Aguaturbia collective expanded the initiative proposed by the Viaje sin mapa exhibition (see previous section) in that it not only sought to bring together issues of Afro representation in art and culture in Colombia, but also proposed ideas for organised anti-racist actions, drawing on Afro artistic networks, which aimed to transform art spaces for Black people in urban contexts.Footnote 21 Artists such as Wilson Borja, Loreta Meneses, Laura Asprilla, Paola Lucumí, Liliana Angulo Cortés, Leonardo Rua and Natalia Mosquera, among others, affirmed the strategy of ‘imagining’ other ways of being for Afro people in spaces, such as Bogotá, where the white–mestizo social configuration consigned Afro people symbolically to the place of eternal outsider.

The anti-racist artistic practices we will discuss here include Black poetry, Black popular music, performance and ‘living arts’, contemporary Afro dance, illustration, photography, visual arts, audiovisual production and works based on archival activism and genealogical research.Footnote 22 Although their aesthetic languages and artistic disciplines are diverse, the anti-racist strategies employed by them can be analysed in terms of three overlapping and intertwined pathways: subversion, irruption and engaging with publics to produce emotional and affective reactions.Footnote 23

In relation to the first strategy of subversion, Benjamin Barber (Reference Barber2011: 110) observes that some analyses of art conceive of it as ‘oppositional, subversive to power, to the conventional order and its paradigms’. Although we understand that art can also be aligned to regimes of power, the character of the artistic practices among the artists that we review here is subversive, as it is intentionally focused on constructing aesthetics that destabilise stereotypes about Afro people and question the racial order in relation to narratives of national identity, constructions of beauty, the criminalisation of social protest, and the racialised effects of the armed conflict. These works employ subversion around representations of the Afro body by highlighting the physical and symbolic violence that results in its erasure from history, its violent elimination and its exoticisation and sexualisation. Often a vital spur to wanting to be subversive is feeling inconforme, literally being dissatisfied, but more widely experiencing a sense of ‘non-conformity’ and being at odds with prevailing trends, which acts as a creative input. As Frantz Fanon (Reference Fanon1986) famously observed, in a racist society Black people frequently experience their bodies as a location for this sense of being at odds: the affective traction produced by an artistic focus on the body is thus especially powerful. Working through and on the Black body and the strictures to which it is subject can produce strong resonances in audiences who may also have experienced their bodies as sites of (racialised) dislocation.

An example of this is offered by the choreographer Rafael Palacios, who founded the Afro-contemporary dance company Sankofa Danzafro in 1997:Footnote 24

What led me to create Sankofa was inconformity with the way dances of Afro origin were represented in Colombia. Especially in the National Folkloric Ballet. I was dissatisfied with the sexualised and exoticised representation of the dances of Afro communities and decided to look for my own language, one that would show Afro dances in their dignity and knowledge

More recently, Sankofa Danzafro has been increasingly oriented in an explicitly anti-racist direction, blurring the frontiers between corporeal and intellectual research, training and choreographic creation (see Chapter 4). The company has elaborated a dance narrative and a sensory experience that surprises, disrupts, affects and sometimes shocks in order to destabilise a single, crystallised narrative of Blackness and challenge complacent images of ‘beautiful and erotic dancing Black bodies’. As Palacios says, in Sankofa’s work the bodies occupy the stage not only to be seen, but also to be heard – in ways that question the racist scaffolding of the society in which they live.

Margarita Ariza Aguilar, who works with visual arts, performance and live arts, expresses a similar inconformity with regard to how the racial order pervades the family sphere. This results in an everyday racism that, while not producing effects as violent as the murder and displacement of Black (and Indigenous) people, generates the intimate violence of internalised racism (Hordge-Freeman Reference Hordge-Freeman2015; Moreno Figueroa Reference Moreno Figueroa2010; Pyke Reference Pyke2010). Ariza’s 2010 project Blanco porcelana (Porcelain White) challenged the everyday norms of beauty, expressed within the family, that valued the whitest phenotypes, encouraged the use of cosmetics that promised el tono perfecto (the perfect tone) and instilled values such as prudencia (prudence) in young women (see Figure 1.4).Footnote 25

When my son was born, I received some of the cards that were given in my family to welcome newborns. These cards said things like ‘he didn’t come out very white …’ and things like that. At that moment, I felt uncomfortable and I began to see how unhappy I felt with all those beauty practices and all the socialisation I had been subjected to in my family to look and be whiter. A whiteness that I was never going to achieve, no matter how hard I tried. That is how the art project Blanco porcelana was born, which questions the aspiration to achieve whiteness and the everyday forms of racism that come from the legacies of colonial origin that we have in our families and that are then reproduced throughout our society

Figure 1.4 Drawing from Blanco porcelana by Margarita Ariza Aguilar, 2010

Figure 1.4 long description.

Figure 1.4Long description

The face has little detail, but the eyes and heavy eyebrows stand out. Although stylised curls are part of the elaborate coiffure surrounding the face, other surreal elements include the Venus de Milo and other such females from the classical period, intended to represent Western standards of female beauty. The artist has intervened in these images in various ways. Next to these is a small photo of the face of the artist as a young child. Also represented are seashells, commonly used in skin-lightening products, and hair combs. At the bottom are the words “Tono Perfecto”, meaning perfect shade, a phrase used to advertiser cosmetics, and “Prudencia”, meaning prudence, referring to the modesty that the artist sees as instilled in young women by society.

Yeison Riascos, an artist from Buenaventura who works with photography and drawing, also makes reference to inconformity, this time in relation to the articulation between the everyday spheres of Afro identities, the racialised order and its relation to much more deadly racialised violence. His photographic work Descendimientos (Descents, 2014) concerns twelve young Black men from Buenaventura on the Pacific coast who were massacred with impunity by paramilitaries in 2012 and were given little public recognition (see Figure 1.5).Footnote 26 Riascos says:

My inconformity with this oblivion led me and my friends who posed for these photographs to recreate Descendimientos. Here [in Buenaventura] violent deaths have become a daily occurrence. We still can’t talk about that here, but I felt dissatisfied and that’s why this is not only a denunciation by me, but also by those who posed for the work. We knew it could have been any one of us.Footnote 27

Figure 1.5 Photo from the series Descendimientos by Yeison Riascos, 2014

The artistic practices of Rafael Palacios, Margarita Ariza Aguilar and Yeison Riascos constitute a subversive anti-racism because they challenge different facets of the racial formation that make them feel inconforme. Palacios develops a narrative language in dance that combats stereotypes using an Afro-centred aesthetic and recovers the knowledge embodied in the dances of Afro communities in Colombia. He critically reviews the daily expressions of racism faced by young Afro-Colombians in Medellín, in the realm of dance and the wider society. His works La ciudad de los otros (The City of the Others, 2010), La mentira complaciente (The Complacent Lie, 2017) and Detrás del sur: Danzas para Manuel (Behind the South: Dances for Manuel, 2021) create intersections between anti-racism, the affirmation of identity and Afro-referentiality through narratives that push audiences to question racialised stereotypes of Black dancing bodies, while the physical and sensory experience of the performance aesthetics lends an affective intensity to this questioning. In the same way, Yeison Riascos with his works Descendimientos and Rostros divinos (Divine Faces, 2012) seeks to decentre colonial representations of Judeo-Christian religiosity, materialising such representations in Afro bodies in order to weaken the Western imaginary of religiosity and whiteness and to make visible the marginalisation of Afro communities in ecclesiastical contexts. And finally, Margarita Ariza, with her project Blanco porcelana, interrogates more subtle and insidious manifestations of racism involved in the representation of whiteness in family contexts, while her later project Black Enough? (2016) explores subtle racism in the way presidential leaders have been represented in Colombia.Footnote 28 The common intention is to question audiences about their own racialisation in conditions of privilege or disadvantage.

The second pathway – that of irruption – may also be spurred by feeling inconforme, but it takes a specific form. The works of the Afro-Colombian poet Pedro Blas Julio Romero and the Afro-feminist poet Ashanti Dinah Orozco, from Cartagena and Barranquilla respectively, are committed to speaking from a place of enunciation informed by Afro epistemologies, challenging the field of poetic production where Afro referents are seen as ‘second-order’. Their anti-racist approach consists of breaking – irrupting – into a literary narrative that omits non-Western references to the motifs of world literature and that creates a profound individualisation of creativity and an exhausting anguish for individual participants disenchanted with their time. The irruption of these Afro poetics creates a pathway towards a ‘contemporary critical debate on the analysis of a textuality unprecedented in terms of its artistic and political significance, which represents a new place of transnational enunciation’ (Maglia, Rocha Vivas and Duchesne Winter Reference Maglia, Vivas and Winter2015: 1). Both writers use poetic language and allusive imagery to circumvent literal-minded rational readings and engage readers on a subliminal plane, generating emotive responses with affective intensity sharpened by the irruptive quality of their imagery. Affect can be traced by attending to the intensity and the rhythm of the poetic discourse (Knudsen and Stage Reference Knudsen and Stage2015) that generates images rooted in the Afro-religious world. Pedro Blas enriches his poetic universe with images such as ‘el diablo piel de abdomen de salamanquesa’ (devil with gecko-belly skin) and ‘Muchacha de las aguas, Gimaní’ (water-girl of Gimaní), which recreate different aspects of the working-class Black neighbourhood of Getsemaní in Cartagena (see Figure 1.6).Footnote 29 The combination of Afro-religious references and allusions to the history and present of the neighbourhood allow him to raise a voice against cultural appropriation, gentrification and the chiaroscuro of heritage policies, and the continuing presence of coloniality in local spaces and their racial conformations.

Figure 1.6 Muchacha de las aguas, Gimaní: digital image created by Hanna Ramírez, 2021, to accompany the eponymous poem by Pedro Blas Julio Romero

Figure 1.6 long description.

Figure 1.6Long description

The woman’s left arm hangs down between her legs. Her right arm rests on a side-table, the top of which is supported by an African sculpture of a kneeling naked female. A small parrot sits atop a Benin-style sculpted woman’s head on the floor by her feet, alongside a large snake and assorted seashells. In the background are two plants in pots adorned with African-style designs, while the walls also have African-style decorations. The whole scene is cut across by a slanting beam of sunlight entering from a window at the back.

Similarly, Ashanti Dinah constructs a strong poetic universe framed by references to Yoruba and Afro-Cuban religiosities.Footnote 30 Questions of meaning, the place of existence and communion with the cosmos – archetypal tropes in world literature – are addressed through highlighting intimate relationships with ancestors and the dead, communion with nature and its role as a messenger of the ancestors, and an everyday rituality expressing an ecological philosophy that fuses time and space into a continuum and blurs the boundaries between the human and the non-human.

These strategies of irruption can also be found in works of ‘artivism’ (artistic activism). Examples include the works of graphic artist Wilson Borja such as Color piel (Skin Colour, 2008), Terato (Monster, 2012), Muestra afro (Afro Showcase, 2018), Reparaciones (Reparations, 2022) and his illustrations for the poems of Ashanti Dinah (2022), all of which challenge the regime of visuality and representation of the Afro in the field of animation and illustration.Footnote 31 Irruption also characterises what might be called ‘art-chivism’, understood as the critical revision of archives from an artistic standpoint to highlight racial injustice, social exclusion and the marginalisation of minoritised groups. Works undertaken by Liliana Angulo Cortés in this vein include the 2015–2016 project Un caso de reparación: Un proyecto de revisión histórica y humanidades digitales (A Case of Reparation: A Project of Revisionist History and Digital Humanities), which explored the relationship of enslavement and Afro-descendants with the colonial-era Botanical Expedition;Footnote 32 and the 2022 project Rodrigo Barrientos: disfrazado de hombre blanco (Rodrigo Barrientos: Disguised as a White Man), which uncovered the previously ignored fact that Barrientos was a Black painter.Footnote 33 These projects were part of Angulo’s Ethno-Education Laboratory, which she established during a guest curatorship at the Museo de Antioquía (Chacón Bernal Reference Chacón Bernal2021). Both Borja and Angulo seek to influence and question the field of education and diverse spaces such as museums, university art education, ethno-education and the production and use of images.

Paralleling the tactics of irruption used by Sankofa Danzafro, the female champeta group Las Emperadoras, from Cartagena, intervenes in the field of Black popular music to affirm the presence of women in champeta music, which had been dominated by Afro-descendant working-class men. Las Emperadoras broaden the field of anti-racist activism by intertwining it with a critique of sexism and the under-representation of women. Las Emperadoras subvert the image of women as passive participants in music, showing not only their capacity for agency as composers, singers, and samplers, but also presenting performances far removed from the hyper-sexualised stereotypes of Black women that are widely purveyed, including by some Afro artists.Footnote 34

This last example indicates that strategies of subversion and irruption are often juxtaposed and intertwined in artistic practice: not all subversion involves irruption, but irruption often has subversive effects. This is also evident in the case of Sankofa Danzafro, where the difference between subversion and irruption is often blurred. The intent is to subvert taken-for-granted racialised orders, but this is achieved by the irruption of the dance performances onto the stage and into the audiences’ sensory apparatus.

Turning now to the third pathway of engaging with publics, the critical interpellation of the public in different forms (as audiences and as communities) is a political intention that characterises all these artists. The Afro-Colombian Cultural Corporation for Social and Cultural Development, CARABANTÚ, mentioned in the previous section, is a good example of the use of art, in this case film, as a tool for engaging Afro communities in the process of emancipation and ethno-education. Recently, with the support of the Wi Da Monikongo collective (also mentioned earlier), they have worked with children and young people to produce a series of short films, screened during the International Kunta Kinte Afro Community Film Festival 2021. The films were made by Afro children and adolescents in Medellín and told stories about their neighbourhoods, with a focus on highlighting the leadership shown by Afro community members.Footnote 35

This kind of artistic practice has contributed to broadening the forms of audience participation, turning members of the public into co-producers of collective narratives that document, accompany and express social discontent. In particular, the social protests that took place in 2017 (a civic strike in May and June in the city of Buenaventura), in 2019 (a national strike on 21 November) and in 2021 (widespread protests in May and June) were scenarios in which the politicisation of artistic practices became a common platform for the spontaneous and passionate expression of a new emerging political subject in Colombia: the young people that made up La Primera Línea.Footnote 36

Examples of the active role that artistic practices played in the 2021 protests include the collective graffiti in the main avenues of cities such as Medellín and Cartagena, street theatre in Barranquilla, and batucadas (street dances with drums) and sit-ins with street concerts in Tumaco, Pasto, Bogotá, Medellín and Cali. In addition, the protests included artistic interventions such as the collective creation of the multi-coloured ten-metre Monumento a la Resistencia in Cali and the painting of graffiti and images onto the huge 1960s national monument, Los Héroes, in Bogotá.

Artists and collectives such as Margarita Ariza, Sankofa Danzafro, Las Emperadoras de la Champeta, Yeison Riascos, Liliana Angulo and CARABANTÚ, among others, engage in artistic practices that can be defined as social, community, participatory, public and contextual art, whose main aim is to pursue, ‘above and beyond aesthetic achievements, the benefits of social change and the participation of communities in the realisation of the work’ (Palacios Garrido Reference Palacios Garrido2009: 199). These works establish artistic practices that question conventions in art about the individualistic nature of creativity and relocate creative acts in their social context, with community participation and with aims of social transformation.

These creators include in their artistic practices the question of the impact of race on the lives of Afro-Colombian people, highlighting how racialisation works in the systematic reproduction of exclusions in the country. The way artistic work has been linked to these social mobilisations in Colombia reflects the erosion of the boundaries between art and social activism. There is a displacement of the conventional terrain of modern art, shifting attention towards the social context, involving audiences, and including the participation of communities that have their own aesthetic and political sensibilities about creative acts. This is a form of participatory expression that decentres assumptions and debates about authorship in art, subsuming them into the political intentionality of community-oriented social transformation (Nardone Reference Nardone2010).

This transformation of artistic practice in Colombia has made it possible to rethink the ways in which racism and the relations between race and artistic practice are addressed in the country. Instead of tracing references to Afroness and Blackness in art, concerns are focused on how these themes are enunciated outside the institutional and formal channels of artistic expression, generating durable discursive and political presences that express identities in cultural and artistic forms that affirm the value of difference.

In relation to the pathway of engaging the public, these artists seek to affect people by challenging assumptions about the raciality of Afro people. These strategies of questioning audiences can generate distinct affective-emotional responses that can unsettle an unprepared viewer. For example, in relation to the reception of Sankofa’s work, in the context of a focus group, one viewer mentioned:Footnote 37

A hook [is created] that has to do with the rigour of their aesthetic format, and which means that this message [the hidden nature of structural problems such as racism] can be conveyed. Suddenly, some unwitting person who goes to see something very aesthetic and very artistic realises that there is a [process of] reflection in the background, which is very important. And that is what is interesting: to take them [audience members] like that, without warning, and then let them reflect and let whatever happens happen in their consciousness

Reactions of discomfort can be generated among audiences by anti-racist artistic practice, as well as emotions of empowerment and empathy:

How uncomfortable to be called racist to your face, without using a single word. I feel that after the performance there was like a tense energy in the Pablo Tobón Uribe [theatre]

There was strength and empathy, adrenaline and strong heartbeats, in a positive sense, when I saw them. It filled me with hope

Anti-racism in Colombian art practice is present today in a range of aesthetic forms – music, illustration, literature, dance and performance – that situate the question of racism in the context of other material aspects of systematic exclusion. In their practice, artists shift towards a commitment to collective pedagogy for social transformation, employing aesthetic codes that are taken from everyday contexts and re-signified through reflections on inequality, racism and rights in society. Artistic practice not only interrogates, but also represents a collective feeling of transcendence of the exclusions experienced by racialised subjects in Colombian society.

Conclusion

This chapter started with a broad look at the representation of racialised difference in Colombia until the end of the nineteenth century, showing how Black and Indigenous subjects were represented as backward and lacking ‘civilisation’. The participation of racialised subaltern artists in artistic production during this period was limited and has been subject to historiographical erasure (which recent critical interventions into the archives are seeking to correct – for example, by highlighting the African ancestry of Botanical Expedition member Salvador Rizo Blanco). The work of the poet Candelario Obeso, who did participate in the literary world and has been recognised, shows that, while prevailing trends of costumbrismo certainly influenced his work, with its focus on local characters and customs, there was also a powerful strand of what we might today label as anti-racism in his assertion of the value of Black lifeways. We next showed how in the first half of the twentieth century, tendencies labelled by scholars as indigenismo and negrismo had the ambivalent effects of highlighting the Indigenous and Black presences in the nation while simultaneously limiting them with romantic and primitivist perspectives. However, Black artists and intellectuals – more numerous than Indigenous ones at that time – often managed to escape the confines of conventional negrismo and promote a racially-aware social justice agenda: Manuel and Delia Zapata Olivella are key examples.

In line with the work of CARLA in Colombia, we then moved the focus to Black artists, tracing the increasing politicisation of their postures from the 1950s and the more explicit attention to racism that came with the influence of international currents, such as Négritude and Black Power, and the continuing increase in numbers of university-educated Black people. The multiculturalist reforms of the 1990s opened some space for debates about racism, but funding and support for ‘cultural diversity’ ultimately diverted attention away from anti-racism. The role of music, already significant in earlier decades, has continued to be important and it reveals the value of a less direct approach to racism that works by affirming Black presence, autonomy and agency.

Our account in the final section of the chapter on the work of the Colombian artists who collaborated with CARLA reinforces the value of a heterogeneous anti-racism: explicit challenges to racist stereotypes and racist aesthetics go alongside forceful assertions of Black agency and autonomy; critical attention to the way Blackness is represented in art goes alongside initiatives to create spaces for Black autonomy within institutional contexts, such as museums and archives, and projects that involve collective participation, including by people who do not identify themselves as artists: the work of Liliana Angulo Cortés in museums and archives is a good example. Anti-racism has become a more explicit frame for these kinds of artistic practice, but what counts as ‘anti-racist’ may be judged in flexible and inclusive ways.

As Guarani curator Sandra Benites eloquently put it, ‘there are folks who think that Indigenous peoples do not suffer racism. How so? Racism in Brazil started against the Indigenous peoples, it started with all this exclusion, with this erasure. It started with them saying that the Indigenous peoples were not human. What is that [if not racism]? What other word would one use to describe it?’ (Benites Reference Benites2021).Footnote 1 Indeed, although historians have long recognised that racism in the Americas is a product of European colonisation, with Amerindians being its first victims, the last decades’ prolific scholarship on racism in Brazil hardly mentions Indigenous peoples. By the same token, the main thrust of anti-racist policy in Brazil has been directed at Afro-descendants, while racism against the Indigenous population is rarely named as such and is marginal to the political agenda, despite the importance of ‘the Indian’ in the national imaginary.