1 Introduction

In recent years, large-scale educational assessments, such as the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA; OECD, 2021), the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP; Johnson & Jenkins, Reference Johnson and Jenkins2004), the Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS; Martin & Kelly, Reference Martin and Kelly1996), and the Progress in International Reading Literacy Study (PIRLS; Mullis et al., Reference Mullis, Martin and Gonzalez2003), have become central to global education research. These assessments produce large-scale and multifaceted datasets, providing valuable insights into student knowledge, skills, and learning behaviors. However, traditional large-scale educational data is typically static and updated periodically, making it challenging to capture the dynamic changes in educational environments and the real-time status of students’ learning. With advances in information technology, online testing platforms and educational assessment tools like adaptive testing now allow the collection of real-time data on students’ responses and behaviors, providing new possibilities for dynamically evaluating educational processes and learning outcomes. Real-time data are characterized by its high speed, large volume, and complexity, requiring efficient computational methods to quickly identify patterns, detect learning obstacles, and predict outcomes. In addition, leveraging this real-time data allows educators to adjust teaching strategies promptly and offer personalized learning experiences for students.

The increasing availability and complexity of large-scale educational datasets have highlighted the need for robust analytical frameworks to handle such data efficiently. Item response theory (IRT; van der Linden & Hambleton, Reference van der Linden and Hambleton1997) has emerged as a powerful tool for analyzing such large datasets. In IRT, parameter estimation is a core component that directly determines the model’s scientific validity and the interpretation of results. The most commonly used estimation method in IRT is marginal maximum likelihood estimation based on the expectation–maximization algorithm (MMLE-EM; Baker & Kim, Reference Baker and Kim2004; Bock & Aitkin, Reference Bock and Aitkin1981). MMLE-EM utilizes an iterative optimization approach that is highly efficient in managing missing data or complex item response datasets, making it particularly adaptable to large-scale educational assessments. However, the computational complexity of this method is primarily influenced by the dimensionality of the latent variables. As the dimensionality of the latent variables increases linearly, the number of quadrature nodes required for integration in the E-step grows exponentially, leading to a substantial increase in computational cost and difficulty.

To address these challenges, current research on IRT focuses on improving computational efficiency for high-dimensional numerical integration. Several methods have been proposed, including adaptive Gaussian quadrature EM algorithms (Rabe-Hesketh et al., Reference Rabe-Hesketh, Skrondal and Pickles2005; Schilling & Bock, Reference Schilling and Bock2005), Laplace approximation methods (Huber et al., Reference Huber, Ronchetti and Victoria-Feser2004; Thomas, Reference Thomas1993), Monte Carlo EM algorithms (Meng & Schilling, Reference Meng and Schilling1996; Song & Lee, Reference Song and Lee2005), Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) methods (Albert, Reference Albert1992; Béguin & Glas, Reference Béguin and Glas2001; Jiang & Templin, Reference Jiang and Templin2019), stochastic approximation methods (Cai, Reference Cai2010a,Reference Caib; Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Chen and Liu2020), and variational inference-based approaches (Cho et al., Reference Cho, Wang, Zhang and Xu2021; Urban & Bauer, Reference Urban and Bauer2021; Wu et al., Reference Wu, Davis, Domingue, Piech and Goodman2020). These methods improve the numerical integration steps of traditional MMLE-EM or introduce approximate inference methods, significantly enhancing parameter estimation accuracy and computational efficiency in high-dimensional scenarios. However, the implementation of these techniques typically relies on complete and static dataset. In real-time dynamic assessments, parameters need to be continuously updated as data streams in, and estimation methods that depend on a complete dataset incur high computational costs. As a result, there is a growing need for faster and more efficient online parameter estimation methods that can update in real time without relying on a complete dataset.

Recently, with the rapid growth of computer-based testing, online algorithms have received widespread attention in statistics and machine learning (e.g., Duchi et al., Reference Duchi, Hazan and Singer2011; Godichon-Baggioni, Reference Godichon-Baggioni2019; Godichon-Baggioni & Lu, Reference Godichon-Baggioni and Lu2024; Saad, Reference Saad2009). These algorithms update parameters in real time by processing data incrementally, reducing memory requirements and making them well-suited for dynamic data streams and large-scale datasets. The stochastic Newton algorithm (SNA) has become a prominent tool in online optimization, offering strong performance in accelerating convergence, addressing high-dimensional challenges, and updating parameters efficiently in real time. For example, Bercu et al. (Reference Bercu, Godichon and Portier2020) proposed a truncated SNA for logistic regression and established its optimal asymptotic behavior. Boyer and Godichon-Baggioni (Reference Boyer and Godichon-Baggioni2023) introduced a weighted averaged SNA within a general framework, proving its almost sure convergence rate and asymptotic normality. Cénac et al. (Reference Cénac, Godichon-Baggioni and Portier2025) developed an online stochastic Gaussian–Newton algorithm and its averaged variant for nonlinear models, demonstrating its asymptotic efficiency. These developments underline the practical and theoretical strengths of SNA in large-scale, real-time optimization tasks.

Online parameter estimation for IRT models has become a significant challenge due to the dynamic nature of assessments. Traditional offline methods often require access to the entire dataset, which is impractical for real-time applications. To address this, Weng and Coad (Reference Weng and Coad2018) proposed a real-time parameter estimation method based on deterministic moment-matching, enabling real-time updates of IRT model parameters within a Bayesian framework. Subsequently, Jiang et al. (Reference Jiang, Xiao and Wang2023) further extended this method to adaptive learning systems, partially addressing parameter estimation challenges in dynamic learning scenarios. However, this approach is limited to estimating only the mean and variance of the parameters, without directly estimating the specific parameters, which restricts its practical applicability.

To overcome this limitation, this study proposes a recursive SNA—referred to as the truncated averaged SNA (TASNA), in the IRT framework. This method incorporates an incremental update mechanism, enabling real-time estimation of both item and examinee ability parameters as response data arrives, without requiring access to or storage of previous response data. This design achieves dynamic and efficient parameter estimation, tailored for real-time applications in large-scale educational assessment.

The TASNA offers notable advantages in handling the real-time data streams and large-scale data in educational measurement. First, TASNA substantially reduces computational costs and memory requirements. TASNA utilizes an incremental update mechanism, processing only one examinee’s data at a time without revisiting previous data. This method lowers computational load and resource usage while significantly decreasing the real-time feedback time, making it well-suited for large-scale online assessments and real-time feedback systems. Second, this study provides a rigorous theoretical analysis of the asymptotic properties of TASNA, demonstrating the almost sure convergence and asymptotic normality of the estimated parameters. This provides a theoretical foundation that ensures the algorithm’s reliability and stability. Moreover, TASNA achieves superior execution efficiency compared to the EM algorithm available in the R package mirt, particularly in large-scale data scenarios, as verified by simulation studies. Therefore, TASNA is not only suitable for real-time parameter estimation in online data streams, but also serves as an efficient alternative to traditional EM algorithms in offline large-scale educational data environments. In brief, the proposed TASNA combines incremental updating mechanisms, efficient stochastic optimization strategies, and theoretical reliability to establish itself as an innovative solution for real-time IRT parameter estimation in dynamic educational assessment.

This article is organized as follows. Section 2 introduces the two-parameter logistic (2PL) model and the multidimensional 2PL (M2PL) model. In Section 3, the proposed online estimation method, the TASNA, is presented. Section 4 presents the theoretical assumptions and the asymptotic properties of the method. Section 5 provides simulation results to evaluate the performance of the TASNA in both the 2PL and M2PL models. In Section 6, an example is provided to demonstrate the application of the TASNA in IRT models. Finally, Section 7 offers concluding remarks.

2 Model presentation

This article focuses on two widely used item response models: the unidimensional 2PL model and the M2PL model. Consider a test with N examinees and J items. Let

![]() $\mathbf {Y} = (y_{nj})_{N \times J}$

represent the observed response data matrix, where each entry

$\mathbf {Y} = (y_{nj})_{N \times J}$

represent the observed response data matrix, where each entry

![]() $y_{nj}$

is either 0 or 1. If

$y_{nj}$

is either 0 or 1. If

![]() $y_{nj} = 1$

, the nth examinee correctly answered the jth item, whereas

$y_{nj} = 1$

, the nth examinee correctly answered the jth item, whereas

![]() $y_{nj} = 0$

indicates an incorrect response, with

$y_{nj} = 0$

indicates an incorrect response, with

![]() $1 \leq n \leq N$

and

$1 \leq n \leq N$

and

![]() $1 \leq j \leq J$

.

$1 \leq j \leq J$

.

In the 2PL model, let

![]() $\theta _n$

be the ability parameter of the nth examinee, and

$\theta _n$

be the ability parameter of the nth examinee, and

![]() $a_j$

and

$a_j$

and

![]() $b_j$

the discrimination and difficulty parameters of the jth item, respectively. The correct response probability of the 2PL model is given by

$b_j$

the discrimination and difficulty parameters of the jth item, respectively. The correct response probability of the 2PL model is given by

$$ \begin{align} P\left(y_{nj}=1\left\vert \theta_{n},a_{j},b_{j}\right.\right) =\frac{\text{exp}\left\{a_{j}(\theta_{n}-b_{j})\right\}}{1+\text{exp} \left\{a_{j}(\theta_{n}-b_{j})\right\}}. \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} P\left(y_{nj}=1\left\vert \theta_{n},a_{j},b_{j}\right.\right) =\frac{\text{exp}\left\{a_{j}(\theta_{n}-b_{j})\right\}}{1+\text{exp} \left\{a_{j}(\theta_{n}-b_{j})\right\}}. \end{align} $$

The M2PL model extends the 2PL model by incorporating a multidimensional framework. Here, the unidimensional latent ability

![]() $\theta _n$

of examinee n is replaced by a Q-dimensional vector

$\theta _n$

of examinee n is replaced by a Q-dimensional vector

![]() $\boldsymbol {\theta }_n = (\theta _{n1}, \ldots , \theta _{nQ})^\top $

, which represents the ability levels of examinee n across multiple latent dimensions. The discrimination parameters for item j become Q-dimensional vector

$\boldsymbol {\theta }_n = (\theta _{n1}, \ldots , \theta _{nQ})^\top $

, which represents the ability levels of examinee n across multiple latent dimensions. The discrimination parameters for item j become Q-dimensional vector

![]() $\boldsymbol {a}_j = (a_{j1},\ldots , a_{jQ})^\top $

, indicating how item j differentiates examinees based on their latent abilities along each dimension of the multidimensional construct

$\boldsymbol {a}_j = (a_{j1},\ldots , a_{jQ})^\top $

, indicating how item j differentiates examinees based on their latent abilities along each dimension of the multidimensional construct

![]() $\boldsymbol {\theta }$

. If

$\boldsymbol {\theta }$

. If

![]() $a_{jq} \neq 0$

, it indicates that item j is associated with the qth latent trait, meaning that the item contributes to measuring the ability on the qth dimension. The intercept parameter of item j,

$a_{jq} \neq 0$

, it indicates that item j is associated with the qth latent trait, meaning that the item contributes to measuring the ability on the qth dimension. The intercept parameter of item j,

![]() $d_j$

, is a scalar and does not vary across dimensions. The correct response probability of the M2PL model is provided as follows:

$d_j$

, is a scalar and does not vary across dimensions. The correct response probability of the M2PL model is provided as follows:

$$ \begin{align} P(y_{nj}=1\left\vert \boldsymbol{\theta}_{n},\boldsymbol{a}_{j},d_{j}\right. )=\frac{\exp\left(\boldsymbol{a}_{j}^\top\boldsymbol{\theta}_{n} +d_{j}\right) }{1+\text{exp}\left(\boldsymbol{a}_{j}^\top\boldsymbol{\theta} _{n}+d_{j}\right)}. \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} P(y_{nj}=1\left\vert \boldsymbol{\theta}_{n},\boldsymbol{a}_{j},d_{j}\right. )=\frac{\exp\left(\boldsymbol{a}_{j}^\top\boldsymbol{\theta}_{n} +d_{j}\right) }{1+\text{exp}\left(\boldsymbol{a}_{j}^\top\boldsymbol{\theta} _{n}+d_{j}\right)}. \end{align} $$

For simplicity in presenting the algorithm, we redefine the parameter notations using the M2PL model as an example. Let the item parameters be

![]() $\boldsymbol {\eta } = (\boldsymbol {\eta }_1^\top , \dots , \boldsymbol {\eta }_J^\top )^\top $

, where

$\boldsymbol {\eta } = (\boldsymbol {\eta }_1^\top , \dots , \boldsymbol {\eta }_J^\top )^\top $

, where

![]() $\boldsymbol {\eta }_j = (d_j, \boldsymbol {a}_j^\top )^\top $

in the M2PL model (and

$\boldsymbol {\eta }_j = (d_j, \boldsymbol {a}_j^\top )^\top $

in the M2PL model (and

![]() $\boldsymbol {\eta }_j = (-a_jb_j, \boldsymbol {a}_j^\top )^\top $

for the 2PL model). Furthermore, we define

$\boldsymbol {\eta }_j = (-a_jb_j, \boldsymbol {a}_j^\top )^\top $

for the 2PL model). Furthermore, we define

![]() $\Theta _n = (1, \boldsymbol {\theta }_n^\top )^\top $

. Thus, the M2PL model can be rewritten as follows:

$\Theta _n = (1, \boldsymbol {\theta }_n^\top )^\top $

. Thus, the M2PL model can be rewritten as follows:

$$ \begin{align} P(y_{nj}=1\left\vert \Theta_n,\boldsymbol{\eta}_j\right. )=\frac{\exp\left(\Theta_n^{\top}\boldsymbol{\eta}_j\right) }{1+\exp\left(\Theta_n^{\top}\boldsymbol{\eta}_j\right)}\triangleq \pi(\Theta_n^{\top}\boldsymbol{\eta}_j). \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} P(y_{nj}=1\left\vert \Theta_n,\boldsymbol{\eta}_j\right. )=\frac{\exp\left(\Theta_n^{\top}\boldsymbol{\eta}_j\right) }{1+\exp\left(\Theta_n^{\top}\boldsymbol{\eta}_j\right)}\triangleq \pi(\Theta_n^{\top}\boldsymbol{\eta}_j). \end{align} $$

The response data

![]() $y_{nj}$

follow a Bernoulli distribution with a success probability

$y_{nj}$

follow a Bernoulli distribution with a success probability

![]() $\pi (\Theta _n^{\top }\boldsymbol {\eta }_j)$

, and it can be expressed as follows:

$\pi (\Theta _n^{\top }\boldsymbol {\eta }_j)$

, and it can be expressed as follows:

where

![]() $\pi (\Theta _n^{\top }\boldsymbol {\eta }_j)$

represents the probability of a correct response, determined by the linear predictor

$\pi (\Theta _n^{\top }\boldsymbol {\eta }_j)$

represents the probability of a correct response, determined by the linear predictor

![]() $\Theta _n^{\top }\boldsymbol {\eta }_j$

passed through a logistic function. Our objective is to perform online estimation of the parameters for the items,

$\Theta _n^{\top }\boldsymbol {\eta }_j$

passed through a logistic function. Our objective is to perform online estimation of the parameters for the items,

![]() $\boldsymbol {\eta }$

, and the latent ability parameter for each individual,

$\boldsymbol {\eta }$

, and the latent ability parameter for each individual,

![]() $\boldsymbol {\theta }_n$

, as the response data for the nth individual arrives. The term “online estimation” refers to dynamically updating the estimates of the parameters in real time, rather than batch-processing all data at once, enabling the model to adapt continuously as new response data is received.

$\boldsymbol {\theta }_n$

, as the response data for the nth individual arrives. The term “online estimation” refers to dynamically updating the estimates of the parameters in real time, rather than batch-processing all data at once, enabling the model to adapt continuously as new response data is received.

3 Stochastic Newton online estimation algorithm

Before introducing the stochastic Newton algorithm (SNA), it is necessary to briefly review the EM algorithm in the IRT framework. The EM algorithm primarily consists of two steps: the E-step and the M-step. In the E-step, each iteration requires the computation of expectations for all examinees and items. While the calculation for a single iteration is relatively straightforward, it becomes highly time-consuming when the number of examinees and items is large. Moreover, due to the characteristics of IRT models, the M-step of the EM algorithm often involves using Newton’s iterative method to maximize the parameters. Newton’s method is a deterministic optimization algorithm that operates on the entire dataset. Specifically, each Newton iteration requires calculating the gradient and Hessian matrix of the objective function based on the entire dataset to determine the update direction for the parameters. This results in high computational complexity, particularly when running on large-scale datasets, making the process extremely time-intensive. Therefore, when dealing with large datasets or when response data arrive continuously and real-time parameter estimation is required, the EM algorithm may struggle to perform fast and efficient computations. This limitation highlights the necessity of exploring more efficient algorithms, such as the SNA, which offers significant advantages for large-scale real-time estimation tasks.

The SNA shares a structural similarity with the traditional Newton algorithm, as both rely on the gradient and Hessian matrix of the objective function to determine the parameter update direction. However, the key difference lies in how these quantities are computed. The traditional Newton algorithm requires computing the gradient and Hessian matrix based on the entire dataset, whereas the SNA (Bercu et al., Reference Bercu, Godichon and Portier2020; Boyer & Godichon-Baggioni, Reference Boyer and Godichon-Baggioni2023; Cénac et al., Reference Cénac, Godichon-Baggioni and Portier2025; Godichon-Baggioni & Lu, Reference Godichon-Baggioni and Lu2024) estimates these quantities incrementally through a recursive process. This approach avoids exhaustive computations on the entire dataset, significantly reducing the consumption of computational resources, making it particularly suitable for large-scale data applications and efficient handling of online data streams.

3.1 Item parameter updates via the truncated average stochastic Newton algorithm

Taking the M2PL model as an example, we first introduce the recursive SNA for estimating item parameters. To align with commonly accepted conventions, we assume that the latent vector

![]() $\boldsymbol {\theta }_n$

for examinee

$\boldsymbol {\theta }_n$

for examinee

![]() $n~(n=1,\ldots ,N)$

follows a multivariate normal distribution with a mean vector of

$n~(n=1,\ldots ,N)$

follows a multivariate normal distribution with a mean vector of

![]() $\boldsymbol {0}$

and an identity matrix as its variance–covariance matrix. When the response data

$\boldsymbol {0}$

and an identity matrix as its variance–covariance matrix. When the response data

![]() $\boldsymbol {y}_{n}=(y_{n1},\ldots ,y_{nJ})^{\top }$

of the nth examinee are received, the marginal probability for examinee n is defined as follows:

$\boldsymbol {y}_{n}=(y_{n1},\ldots ,y_{nJ})^{\top }$

of the nth examinee are received, the marginal probability for examinee n is defined as follows:

where

![]() $P(\boldsymbol {y}_{n}|\Theta _n,\boldsymbol {\eta })=\prod _{j=1}^J\pi (\Theta _n^{\top }\boldsymbol {\eta }_j)^{y_{nj}}(1-\pi (\Theta _n^{\top }\boldsymbol {\eta }_j))^{1-y_{nj}}$

. The integral of

$P(\boldsymbol {y}_{n}|\Theta _n,\boldsymbol {\eta })=\prod _{j=1}^J\pi (\Theta _n^{\top }\boldsymbol {\eta }_j)^{y_{nj}}(1-\pi (\Theta _n^{\top }\boldsymbol {\eta }_j))^{1-y_{nj}}$

. The integral of

![]() $f(\boldsymbol {y}_{n}|\boldsymbol {\eta })$

is typically evaluated using an integral approximation procedure. When the dimensionality is five or fewer, the fixed-point Gauss–Hermite quadrature method (Bock & Aitkin, Reference Bock and Aitkin1981) is commonly employed. For higher-dimensional cases, adaptive quadrature techniques are used (Schilling & Bock, Reference Schilling and Bock2005). To simplify the explanation without losing generality, the expression of

$f(\boldsymbol {y}_{n}|\boldsymbol {\eta })$

is typically evaluated using an integral approximation procedure. When the dimensionality is five or fewer, the fixed-point Gauss–Hermite quadrature method (Bock & Aitkin, Reference Bock and Aitkin1981) is commonly employed. For higher-dimensional cases, adaptive quadrature techniques are used (Schilling & Bock, Reference Schilling and Bock2005). To simplify the explanation without losing generality, the expression of

![]() $f(\boldsymbol {y}_{n}|\boldsymbol {\eta })$

after approximation using the fixed-point Gauss–Hermite quadrature technique is given below:

$f(\boldsymbol {y}_{n}|\boldsymbol {\eta })$

after approximation using the fixed-point Gauss–Hermite quadrature technique is given below:

$$ \begin{align} f(\boldsymbol{y}_{n}|\boldsymbol{\eta})\approx\sum_{k_Q=1}^{K}\dots\sum_{k_1=1}^{K} P(\boldsymbol{y}_{n}|\boldsymbol{X}_k,\boldsymbol{\eta})w(x_{k_1})\dots w(x_{k_Q}). \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} f(\boldsymbol{y}_{n}|\boldsymbol{\eta})\approx\sum_{k_Q=1}^{K}\dots\sum_{k_1=1}^{K} P(\boldsymbol{y}_{n}|\boldsymbol{X}_k,\boldsymbol{\eta})w(x_{k_1})\dots w(x_{k_Q}). \end{align} $$

Here,

![]() $\boldsymbol {X}_k = (1, \boldsymbol {x_k}^{\top })^{\top }$

,

$\boldsymbol {X}_k = (1, \boldsymbol {x_k}^{\top })^{\top }$

,

![]() $k=1,\ldots ,K$

, where

$k=1,\ldots ,K$

, where

![]() $\boldsymbol {x_k} = (x_{k_1}, \ldots , x_{k_Q})^{\top }$

represents the vector of values at the specified quadrature nodes and K denotes the number of quadrature nodes in a single dimension. Each

$\boldsymbol {x_k} = (x_{k_1}, \ldots , x_{k_Q})^{\top }$

represents the vector of values at the specified quadrature nodes and K denotes the number of quadrature nodes in a single dimension. Each

![]() $x_{k_q}$

denotes the value of a quadrature node in dimension q, and

$x_{k_q}$

denotes the value of a quadrature node in dimension q, and

![]() $w(x_{k_q})$

is the weight associated with the quadrature node in dimension q. The weight

$w(x_{k_q})$

is the weight associated with the quadrature node in dimension q. The weight

![]() $w(x_{k_q})$

depends on the height of the normal density function at that node and the spacing between adjacent quadrature nodes. The index

$w(x_{k_q})$

depends on the height of the normal density function at that node and the spacing between adjacent quadrature nodes. The index

![]() $k_q$

represents the position of the K quadrature nodes in dimension q. Traditional offline methods typically rely on batch data to compute the global objective function. In contrast, the SNA updates the parameters using only the current single sample data rather than the entire dataset. Consequently, the objective function (defined in this article as the negative log-likelihood function) for the nth examinee is

$k_q$

represents the position of the K quadrature nodes in dimension q. Traditional offline methods typically rely on batch data to compute the global objective function. In contrast, the SNA updates the parameters using only the current single sample data rather than the entire dataset. Consequently, the objective function (defined in this article as the negative log-likelihood function) for the nth examinee is

$$ \begin{align} \ell(\boldsymbol{y}_{n},\boldsymbol{\eta})=-\log f(\boldsymbol{y}_{n}|\boldsymbol{\eta})\approx-\log\sum_{k=1}^{K^Q} P(\boldsymbol{y}_{n}|\boldsymbol{X}_k,\boldsymbol{\eta})\boldsymbol{w}(\boldsymbol{x}_{k}), \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} \ell(\boldsymbol{y}_{n},\boldsymbol{\eta})=-\log f(\boldsymbol{y}_{n}|\boldsymbol{\eta})\approx-\log\sum_{k=1}^{K^Q} P(\boldsymbol{y}_{n}|\boldsymbol{X}_k,\boldsymbol{\eta})\boldsymbol{w}(\boldsymbol{x}_{k}), \end{align} $$

where

![]() $P(\boldsymbol {y}_n|\boldsymbol {X}_k,\boldsymbol {\eta }) = \prod _{j=1}^J\pi (\boldsymbol {X}_k^{\top }\boldsymbol {\eta }_j)^{y_{nj}}(1-\pi (\boldsymbol {X}_k^{\top }\boldsymbol {\eta }_j))^{1-y_{nj}}$

with

$P(\boldsymbol {y}_n|\boldsymbol {X}_k,\boldsymbol {\eta }) = \prod _{j=1}^J\pi (\boldsymbol {X}_k^{\top }\boldsymbol {\eta }_j)^{y_{nj}}(1-\pi (\boldsymbol {X}_k^{\top }\boldsymbol {\eta }_j))^{1-y_{nj}}$

with

![]() $\pi (\boldsymbol {X}_k^{\top }\boldsymbol {\eta }_j) = \frac {\exp (\boldsymbol {X}_k^{\top }\boldsymbol {\eta }_j)}{1+\exp (\boldsymbol {X}_k^{\top }\boldsymbol {\eta }_j)}$

. The summation

$\pi (\boldsymbol {X}_k^{\top }\boldsymbol {\eta }_j) = \frac {\exp (\boldsymbol {X}_k^{\top }\boldsymbol {\eta }_j)}{1+\exp (\boldsymbol {X}_k^{\top }\boldsymbol {\eta }_j)}$

. The summation

![]() $\sum _{k=1}^{K^Q}=\sum _{k_1=1}^K\dots \sum _{k_Q=1}^K$

, and

$\sum _{k=1}^{K^Q}=\sum _{k_1=1}^K\dots \sum _{k_Q=1}^K$

, and

![]() $\boldsymbol {w}(\boldsymbol {x}_{k}) = w(x_{k_1})\dots w(x_{k_Q})$

is the product of the weights for the respective quadrature nodes.

$\boldsymbol {w}(\boldsymbol {x}_{k}) = w(x_{k_1})\dots w(x_{k_Q})$

is the product of the weights for the respective quadrature nodes.

The SNA updates the parameters incrementally as data arrive. For each newly arrived response data, the item parameters are updated using the current response data and the parameter estimates from the previous iteration. When the response data of the nth examinee arrive, the empirical gradient vector and Hessian matrix (i.e., the first and second derivatives computed with respect to the current sample) for the jth item parameter

![]() $(j=1, \ldots , J)$

are derived based on the parameters

$(j=1, \ldots , J)$

are derived based on the parameters

![]() $\widehat {\boldsymbol {\eta }}_{n-1}$

from the previous iteration, as follows (refer to Chapter 6 of Baker and Kim (Reference Baker and Kim2004) for detailed computations):

$\widehat {\boldsymbol {\eta }}_{n-1}$

from the previous iteration, as follows (refer to Chapter 6 of Baker and Kim (Reference Baker and Kim2004) for detailed computations):

$$ \begin{align} \nabla_{j}\ell(\boldsymbol{y}_{n},\widehat{\boldsymbol{\eta}}_{n-1})&=\frac{\partial\ell(\boldsymbol{y}_{n},\boldsymbol{\eta})}{\partial\boldsymbol{\eta}_j }\Big|_{\boldsymbol{\eta}=\widehat{\boldsymbol{\eta}}_{n-1}}=\sum_{k=1}^{K^Q}f_{k}(\widehat{\boldsymbol{\eta}}_{n-1})\left[\pi(\boldsymbol{X}_k^{\top}\widehat{\boldsymbol{\eta}}_{n-1,j})-y_{nj}\right]\boldsymbol{X}_k, \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} \nabla_{j}\ell(\boldsymbol{y}_{n},\widehat{\boldsymbol{\eta}}_{n-1})&=\frac{\partial\ell(\boldsymbol{y}_{n},\boldsymbol{\eta})}{\partial\boldsymbol{\eta}_j }\Big|_{\boldsymbol{\eta}=\widehat{\boldsymbol{\eta}}_{n-1}}=\sum_{k=1}^{K^Q}f_{k}(\widehat{\boldsymbol{\eta}}_{n-1})\left[\pi(\boldsymbol{X}_k^{\top}\widehat{\boldsymbol{\eta}}_{n-1,j})-y_{nj}\right]\boldsymbol{X}_k, \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} \nabla_{j}^2\ell(\boldsymbol{y}_{n},\widehat{\boldsymbol{\eta}}_{n-1})&=\frac{\partial^2\ell(\boldsymbol{y}_{n},\boldsymbol{\eta})}{\partial\boldsymbol{\eta}_j\partial\boldsymbol{\eta}_j^{\top} }\Big|_{\boldsymbol{\eta}=\widehat{\boldsymbol{\eta}}_{n-1}} =\sum_{k=1}^{K^Q}f_{k}(\widehat{\boldsymbol{\eta}}_{n-1})\pi(\boldsymbol{X}_k^{\top}\widehat{\boldsymbol{\eta}}_{n-1,j})(1-\pi(\boldsymbol{X}_k^{\top}\widehat{\boldsymbol{\eta}}_{n-1,j}))\boldsymbol{X}_k\boldsymbol{X}_k^{\top}, \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} \nabla_{j}^2\ell(\boldsymbol{y}_{n},\widehat{\boldsymbol{\eta}}_{n-1})&=\frac{\partial^2\ell(\boldsymbol{y}_{n},\boldsymbol{\eta})}{\partial\boldsymbol{\eta}_j\partial\boldsymbol{\eta}_j^{\top} }\Big|_{\boldsymbol{\eta}=\widehat{\boldsymbol{\eta}}_{n-1}} =\sum_{k=1}^{K^Q}f_{k}(\widehat{\boldsymbol{\eta}}_{n-1})\pi(\boldsymbol{X}_k^{\top}\widehat{\boldsymbol{\eta}}_{n-1,j})(1-\pi(\boldsymbol{X}_k^{\top}\widehat{\boldsymbol{\eta}}_{n-1,j}))\boldsymbol{X}_k\boldsymbol{X}_k^{\top}, \end{align} $$

where

$$ \begin{align} f_{k}(\widehat{\boldsymbol{\eta}}_{n-1})=\frac{\prod_{j=1}^J\pi(\boldsymbol{X}_k^{\top}\widehat{\boldsymbol{\eta}}_{n-1,j})^{y_{nj}}\left(1-\pi(\boldsymbol{X}_k^{\top}\widehat{\boldsymbol{\eta}}_{n-1,j})\right)^{1-y_{nj}}\boldsymbol{w}(\boldsymbol{x}_{k})}{\sum_{k=1}^{K^Q}\prod_{j=1}^J\pi(\boldsymbol{X}_k^{\top}\widehat{\boldsymbol{\eta}}_{n-1,j})^{y_{nj}}\left(1-\pi(\boldsymbol{X}_k^{\top}\widehat{\boldsymbol{\eta}}_{n-1,j})\right)^{1-y_{nj}}\boldsymbol{w}(\boldsymbol{x}_{k})}. \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} f_{k}(\widehat{\boldsymbol{\eta}}_{n-1})=\frac{\prod_{j=1}^J\pi(\boldsymbol{X}_k^{\top}\widehat{\boldsymbol{\eta}}_{n-1,j})^{y_{nj}}\left(1-\pi(\boldsymbol{X}_k^{\top}\widehat{\boldsymbol{\eta}}_{n-1,j})\right)^{1-y_{nj}}\boldsymbol{w}(\boldsymbol{x}_{k})}{\sum_{k=1}^{K^Q}\prod_{j=1}^J\pi(\boldsymbol{X}_k^{\top}\widehat{\boldsymbol{\eta}}_{n-1,j})^{y_{nj}}\left(1-\pi(\boldsymbol{X}_k^{\top}\widehat{\boldsymbol{\eta}}_{n-1,j})\right)^{1-y_{nj}}\boldsymbol{w}(\boldsymbol{x}_{k})}. \end{align} $$

Note that Equation (8) represents the second-order derivative matrix for the newly arrived data and does not approximate the true Hessian matrix. However, for large-scale datasets or real-time data streams, directly computing the true Hessian matrix is computationally expensive. To address this, historical Hessian information is accumulated using a recursive formula, allowing the approximation of the Hessian matrix to be updated incrementally as new data arrive. This approach enables the algorithm to update model parameters efficiently while incorporating new data, without the need to re-process the entire dataset. Leveraging historical information accelerates convergence and enhances the algorithm’s robustness and computational efficiency. The recursive formula for updating the Hessian matrix is provided below for

![]() $j = 1, \ldots , J$

:

$j = 1, \ldots , J$

:

$$ \begin{align} \boldsymbol{S}_{n,j}&=\boldsymbol{S}_{n-1,j}+\nabla_{j}^2\ell(\boldsymbol{y}_{n},\widehat{\boldsymbol{\eta}}_{n-1})\notag\\ &=\boldsymbol{S}_{n-1,j}+\sum_{k=1}^{K^Q}f_{k}(\widehat{\boldsymbol{\eta}}_{n-1})\pi(\boldsymbol{X}_k^{\top}\widehat{\boldsymbol{\eta}}_{n-1,j})(1-\pi(\boldsymbol{X}_k^{\top}\widehat{\boldsymbol{\eta}}_{n-1,j}))\boldsymbol{X}_k\boldsymbol{X}_k^{\top}\notag\\ &=\boldsymbol{S}_{0,j}+\sum_{i=1}^{n}\sum_{k=1}^{K^Q}f_{k}(\widehat{\boldsymbol{\eta}}_{i-1})\pi(\boldsymbol{X}_k^{\top}\widehat{\boldsymbol{\eta}}_{i-1,j})(1-\pi(\boldsymbol{X}_k^{\top}\widehat{\boldsymbol{\eta}}_{i-1,j}))\boldsymbol{X}_k\boldsymbol{X}_k^{\top}, \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} \boldsymbol{S}_{n,j}&=\boldsymbol{S}_{n-1,j}+\nabla_{j}^2\ell(\boldsymbol{y}_{n},\widehat{\boldsymbol{\eta}}_{n-1})\notag\\ &=\boldsymbol{S}_{n-1,j}+\sum_{k=1}^{K^Q}f_{k}(\widehat{\boldsymbol{\eta}}_{n-1})\pi(\boldsymbol{X}_k^{\top}\widehat{\boldsymbol{\eta}}_{n-1,j})(1-\pi(\boldsymbol{X}_k^{\top}\widehat{\boldsymbol{\eta}}_{n-1,j}))\boldsymbol{X}_k\boldsymbol{X}_k^{\top}\notag\\ &=\boldsymbol{S}_{0,j}+\sum_{i=1}^{n}\sum_{k=1}^{K^Q}f_{k}(\widehat{\boldsymbol{\eta}}_{i-1})\pi(\boldsymbol{X}_k^{\top}\widehat{\boldsymbol{\eta}}_{i-1,j})(1-\pi(\boldsymbol{X}_k^{\top}\widehat{\boldsymbol{\eta}}_{i-1,j}))\boldsymbol{X}_k\boldsymbol{X}_k^{\top}, \end{align} $$

where

![]() $\boldsymbol {S}_{0,j}$

represents the initial value of the Hessian matrix, which is symmetric and positive definite, and

$\boldsymbol {S}_{0,j}$

represents the initial value of the Hessian matrix, which is symmetric and positive definite, and

![]() $\widehat {\boldsymbol {\eta }}_{0} = (\widehat {\boldsymbol {\eta }}_{0,1}^\top , \dots , \widehat {\boldsymbol {\eta }}_{0,J}^\top )^\top $

denotes the initial item parameter estimates. By recursively updating the Hessian matrix estimate, the SNA significantly reduces the computational cost of each iteration, making it more suitable for large-scale datasets and online learning context. The updated formula for the SNA within the IRT framework is provided below:

$\widehat {\boldsymbol {\eta }}_{0} = (\widehat {\boldsymbol {\eta }}_{0,1}^\top , \dots , \widehat {\boldsymbol {\eta }}_{0,J}^\top )^\top $

denotes the initial item parameter estimates. By recursively updating the Hessian matrix estimate, the SNA significantly reduces the computational cost of each iteration, making it more suitable for large-scale datasets and online learning context. The updated formula for the SNA within the IRT framework is provided below:

Here,

![]() $\overline {\boldsymbol {S}}_{n,j} = \frac {1}{n+1}\boldsymbol {S}_{n,j}$

. Boyer and Godichon-Baggioni (Reference Boyer and Godichon-Baggioni2023) and Cénac et al. (Reference Cénac, Godichon-Baggioni and Portier2025) argued that the original SNA decreases at a step rate of

$\overline {\boldsymbol {S}}_{n,j} = \frac {1}{n+1}\boldsymbol {S}_{n,j}$

. Boyer and Godichon-Baggioni (Reference Boyer and Godichon-Baggioni2023) and Cénac et al. (Reference Cénac, Godichon-Baggioni and Portier2025) argued that the original SNA decreases at a step rate of

![]() $\frac {1}{n}$

, which may hinder the dynamics of the algorithm and lead to suboptimal results in cases of improper initialization. To address this issue, we introduce a new step size sequence

$\frac {1}{n}$

, which may hinder the dynamics of the algorithm and lead to suboptimal results in cases of improper initialization. To address this issue, we introduce a new step size sequence

![]() $\gamma _n = \frac {1}{n^{\gamma }}$

, where

$\gamma _n = \frac {1}{n^{\gamma }}$

, where

![]() $\gamma \in (\frac {1}{2},1)$

, and incorporate an averaging step to ensure the asymptotic efficiency of the algorithm. However, the convergence properties of the parameters for the original SNA cannot be established. Therefore, following the approach of Bercu et al. (Reference Bercu, Godichon and Portier2020), we present a truncated averaged SNA (TASNA). The update process for the jth item parameter (

$\gamma \in (\frac {1}{2},1)$

, and incorporate an averaging step to ensure the asymptotic efficiency of the algorithm. However, the convergence properties of the parameters for the original SNA cannot be established. Therefore, following the approach of Bercu et al. (Reference Bercu, Godichon and Portier2020), we present a truncated averaged SNA (TASNA). The update process for the jth item parameter (

![]() $j=1,\ldots ,J$

) is given below:

$j=1,\ldots ,J$

) is given below:

$$ \begin{align} &f_{k}(\widehat{\boldsymbol{\eta}}_{n-1})=\frac{\prod_{j=1}^J\pi(\boldsymbol{X}_k^{\top}\widehat{\boldsymbol{\eta}}_{n-1,j})^{y_{nj}}\left(1-\pi(\boldsymbol{X}_k^{\top}\widehat{\boldsymbol{\eta}}_{n-1,j})\right)^{1-y_{nj}}\boldsymbol{w}(\boldsymbol{x}_{k})}{\sum_{k=1}^{K^Q}\prod_{j=1}^J\pi(\boldsymbol{X}_k^{\top}\widehat{\boldsymbol{\eta}}_{n-1,j})^{y_{nj}}\left(1-\pi(\boldsymbol{X}_k^{\top}\widehat{\boldsymbol{\eta}}_{n-1,j})\right)^{1-y_{nj}}\boldsymbol{w}(\boldsymbol{x}_{k})}, \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} &f_{k}(\widehat{\boldsymbol{\eta}}_{n-1})=\frac{\prod_{j=1}^J\pi(\boldsymbol{X}_k^{\top}\widehat{\boldsymbol{\eta}}_{n-1,j})^{y_{nj}}\left(1-\pi(\boldsymbol{X}_k^{\top}\widehat{\boldsymbol{\eta}}_{n-1,j})\right)^{1-y_{nj}}\boldsymbol{w}(\boldsymbol{x}_{k})}{\sum_{k=1}^{K^Q}\prod_{j=1}^J\pi(\boldsymbol{X}_k^{\top}\widehat{\boldsymbol{\eta}}_{n-1,j})^{y_{nj}}\left(1-\pi(\boldsymbol{X}_k^{\top}\widehat{\boldsymbol{\eta}}_{n-1,j})\right)^{1-y_{nj}}\boldsymbol{w}(\boldsymbol{x}_{k})}, \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} &\boldsymbol{S}_{n,j}=\boldsymbol{S}_{n-1,j}+\sum_{k=1}^{K^Q}f_{k}(\widehat{\boldsymbol{\eta}}_{n-1})\alpha_{n,k}\boldsymbol{X}_k\boldsymbol{X}_k^{\top}, \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} &\boldsymbol{S}_{n,j}=\boldsymbol{S}_{n-1,j}+\sum_{k=1}^{K^Q}f_{k}(\widehat{\boldsymbol{\eta}}_{n-1})\alpha_{n,k}\boldsymbol{X}_k\boldsymbol{X}_k^{\top}, \end{align} $$

where

![]() $\widetilde {\boldsymbol {\eta }}_{n,j}$

and

$\widetilde {\boldsymbol {\eta }}_{n,j}$

and

![]() $\widehat {\boldsymbol {\eta }}_{n,j}$

represent the jth item parameter estimates before and after applying the averaging step, respectively. The step sequence is defined as

$\widehat {\boldsymbol {\eta }}_{n,j}$

represent the jth item parameter estimates before and after applying the averaging step, respectively. The step sequence is defined as

![]() $\gamma _{n} = \frac {1}{(n + c_{\eta })^{\gamma }}$

, where the step parameter

$\gamma _{n} = \frac {1}{(n + c_{\eta })^{\gamma }}$

, where the step parameter

![]() $\gamma \in (\frac {1}{2}, 1)$

. The averaging step is defined as

$\gamma \in (\frac {1}{2}, 1)$

. The averaging step is defined as

with the averaging sequence

![]() $\kappa _{n} = \frac {1}{n}$

. The term

$\kappa _{n} = \frac {1}{n}$

. The term

![]() $\boldsymbol {Z}_{n,j}$

denotes the updated gradient

$\boldsymbol {Z}_{n,j}$

denotes the updated gradient

![]() $\nabla _{j}\ell (\boldsymbol {y}_{n},\widetilde {\boldsymbol {\eta }}_{n-1})$

, and

$\nabla _{j}\ell (\boldsymbol {y}_{n},\widetilde {\boldsymbol {\eta }}_{n-1})$

, and

![]() $\overline {\boldsymbol {S}}_{n-1,j} = \frac {1}{n}\boldsymbol {S}_{n-1,j}$

represents the scaled Hessian matrix from the previous iteration. It is important to note that the update of

$\overline {\boldsymbol {S}}_{n-1,j} = \frac {1}{n}\boldsymbol {S}_{n-1,j}$

represents the scaled Hessian matrix from the previous iteration. It is important to note that the update of

![]() $\boldsymbol {S}_{n,j}$

depends on the averaged parameter

$\boldsymbol {S}_{n,j}$

depends on the averaged parameter

![]() $\widehat {\boldsymbol {\eta }}_{n-1,j}$

rather than

$\widehat {\boldsymbol {\eta }}_{n-1,j}$

rather than

![]() $\widetilde {\boldsymbol {\eta }}_{n-1,j}$

, enabling faster convergence. The value of

$\widetilde {\boldsymbol {\eta }}_{n-1,j}$

, enabling faster convergence. The value of

![]() $\alpha _{n,k}$

is given by

$\alpha _{n,k}$

is given by

which is used for truncating the Hessian matrix.

Remark 1. The constant

![]() $c_{\eta }> 0$

is added to the denominator of

$c_{\eta }> 0$

is added to the denominator of

![]() $\gamma _n$

to mitigate the effect of poorer estimates produced by the algorithm during the initial iterations (when n is small). As n increases, this effect diminishes, and the quality of the iterative results improves.

$\gamma _n$

to mitigate the effect of poorer estimates produced by the algorithm during the initial iterations (when n is small). As n increases, this effect diminishes, and the quality of the iterative results improves.

Remark 2. When

![]() $\kappa _{n}$

is fixed at 1, the TASNA reduces to the TSNA. TSNA is a special case of TASNA. By performing a weighted average over multiple stochastic gradient calculations, TASNA reduces the impact of random noise. Although TASNA requires slightly more computational time compared to TSNA (due to the averaging step), it achieves smoother convergence and more stable parameter estimation. In contrast, TSNA updates parameters in each iteration solely based on the current batch of samples, without a global averaging step. As a result, its convergence may be slower and exhibit greater fluctuations. In resource-constrained scenarios, TSNA can be used to trade off some convergence accuracy for improved computational efficiency. However, for more stable and accurate parameter estimation, TASNA is recommended.

$\kappa _{n}$

is fixed at 1, the TASNA reduces to the TSNA. TSNA is a special case of TASNA. By performing a weighted average over multiple stochastic gradient calculations, TASNA reduces the impact of random noise. Although TASNA requires slightly more computational time compared to TSNA (due to the averaging step), it achieves smoother convergence and more stable parameter estimation. In contrast, TSNA updates parameters in each iteration solely based on the current batch of samples, without a global averaging step. As a result, its convergence may be slower and exhibit greater fluctuations. In resource-constrained scenarios, TSNA can be used to trade off some convergence accuracy for improved computational efficiency. However, for more stable and accurate parameter estimation, TASNA is recommended.

Remark 3. For some positive constant

![]() $c_{\beta }$

, the sequence

$c_{\beta }$

, the sequence

![]() $\alpha _{n,k}$

is defined as

$\alpha _{n,k}$

is defined as

$$ \begin{align} \alpha_{n,k}&=\max\{\pi(\boldsymbol{X}_k^{\top}\widehat{\boldsymbol{\eta}}_{n-1,j})(1-\pi(\boldsymbol{X}_k^{\top}\widehat{\boldsymbol{\eta}}_{n-1,j})),\frac{c_{\beta}}{n^{\beta}}\}\notag\\ &=\max\left\{\frac{1}{4(\cosh (\boldsymbol{X}_k^{\top}\widehat{\boldsymbol{\eta}}_{n-1,j}/2))^2},\frac{c_{\beta}}{n^{\beta}}\right\}, \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} \alpha_{n,k}&=\max\{\pi(\boldsymbol{X}_k^{\top}\widehat{\boldsymbol{\eta}}_{n-1,j})(1-\pi(\boldsymbol{X}_k^{\top}\widehat{\boldsymbol{\eta}}_{n-1,j})),\frac{c_{\beta}}{n^{\beta}}\}\notag\\ &=\max\left\{\frac{1}{4(\cosh (\boldsymbol{X}_k^{\top}\widehat{\boldsymbol{\eta}}_{n-1,j}/2))^2},\frac{c_{\beta}}{n^{\beta}}\right\}, \end{align} $$

where

![]() $\beta < \gamma - \frac {1}{2}$

. Since the hyperbolic cosine function

$\beta < \gamma - \frac {1}{2}$

. Since the hyperbolic cosine function

![]() $\cosh (x)$

takes values in the range

$\cosh (x)$

takes values in the range

![]() $[1, +\infty )$

, we assume that

$[1, +\infty )$

, we assume that

![]() $c_{\beta } < \frac {1}{4}$

, which ensures

$c_{\beta } < \frac {1}{4}$

, which ensures

![]() $\alpha _{n,k} < \frac {1}{4}$

for

$\alpha _{n,k} < \frac {1}{4}$

for

![]() $n \geq 1$

. Under this truncation operation, the convergence of the Hessian matrix estimation can be proven. Please see Section 4 for details.

$n \geq 1$

. Under this truncation operation, the convergence of the Hessian matrix estimation can be proven. Please see Section 4 for details.

3.2 Updating ability parameters by expected a posteriori estimation

For estimating the examinees’ ability parameters, researchers typically rely on methods, such as maximum likelihood estimation (MLE), maximum a posteriori estimation (MAP), or expected a posteriori estimation (EAP) after the item parameters have been estimated (Bock & Aitkin, Reference Bock and Aitkin1981; Wang, Reference Wang2015). It is well known that MLE relies on batch data to compute the global likelihood, which indicates the entire likelihood function must be recalculated whenever new data are added. This makes MLE computationally expensive in online environments where data continuously stream in, rendering it unsuitable for efficient online updating. In contrast, MAP incorporates prior information by maximizing the posterior probability. Although it is more flexible than MLE due to its ability to include prior information, it typically requires a large amount of historical data for global optimization. Furthermore, because of the structure of IRT models, MAP estimation often relies on iterative optimization methods, such as Newton’s method or gradient descent, to maximize the posterior probability. This iterative process further increases computational complexity and time. Detailed implementations of these two methods can be found in Wang (Reference Wang2015) and Bock and Aitkin (Reference Bock and Aitkin1981).

Unlike the two methods mentioned above, EAP estimation computes the posterior expectation of the ability parameter

![]() $\boldsymbol {\theta }$

as a point estimate. The process for EAP estimation of

$\boldsymbol {\theta }$

as a point estimate. The process for EAP estimation of

![]() $\boldsymbol {\theta }$

has been outlined by Bock and Aitkin (Reference Bock and Aitkin1981), Muraki and Engelhard Jr. (Reference Muraki and Engelhard1985), and Wang (Reference Wang2015). EAP estimation has the advantage of ensuring that the estimated ability parameter derived from item scores, even with short test items, does not diverge toward infinity. This makes it particularly suitable for cases where data are limited or strong prior information is available (Reckase, Reference Reckase2009). The mathematical expression for this estimation is as follows:

$\boldsymbol {\theta }$

has been outlined by Bock and Aitkin (Reference Bock and Aitkin1981), Muraki and Engelhard Jr. (Reference Muraki and Engelhard1985), and Wang (Reference Wang2015). EAP estimation has the advantage of ensuring that the estimated ability parameter derived from item scores, even with short test items, does not diverge toward infinity. This makes it particularly suitable for cases where data are limited or strong prior information is available (Reckase, Reference Reckase2009). The mathematical expression for this estimation is as follows:

$$ \begin{align} \widehat{\theta}_{nq}=\mathbb{E}(\theta_{nq}|\boldsymbol{y}_n)=\frac{\int\theta_{nq}P(\boldsymbol{y}_n|\Theta_n,\boldsymbol{\eta})\phi(\boldsymbol{\theta}_n)d\boldsymbol{\theta}_n}{\int P(\boldsymbol{y}_n|\Theta_n,\boldsymbol{\eta})\phi(\boldsymbol{\theta}_n)d\boldsymbol{\theta}_n}=\int\theta_{nq}\frac{P(\boldsymbol{y}_n|\Theta_n,\boldsymbol{\eta})\phi(\boldsymbol{\theta}_n)}{f(\boldsymbol{y}_n|\boldsymbol{\eta})}d\boldsymbol{\theta}_n. \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} \widehat{\theta}_{nq}=\mathbb{E}(\theta_{nq}|\boldsymbol{y}_n)=\frac{\int\theta_{nq}P(\boldsymbol{y}_n|\Theta_n,\boldsymbol{\eta})\phi(\boldsymbol{\theta}_n)d\boldsymbol{\theta}_n}{\int P(\boldsymbol{y}_n|\Theta_n,\boldsymbol{\eta})\phi(\boldsymbol{\theta}_n)d\boldsymbol{\theta}_n}=\int\theta_{nq}\frac{P(\boldsymbol{y}_n|\Theta_n,\boldsymbol{\eta})\phi(\boldsymbol{\theta}_n)}{f(\boldsymbol{y}_n|\boldsymbol{\eta})}d\boldsymbol{\theta}_n. \end{align} $$

Here,

![]() $\theta _{nq}$

represents the qth dimension of the latent trait for the nth examinee, where

$\theta _{nq}$

represents the qth dimension of the latent trait for the nth examinee, where

![]() $q = 1, \ldots , Q$

. Given known item parameters

$q = 1, \ldots , Q$

. Given known item parameters

![]() $\boldsymbol {\eta }$

, the integral in Equation (18) can be approximated using the Gauss–Hermite quadrature method. The approximated expression for

$\boldsymbol {\eta }$

, the integral in Equation (18) can be approximated using the Gauss–Hermite quadrature method. The approximated expression for

![]() $\widehat {\theta }_{nq}$

is

$\widehat {\theta }_{nq}$

is

$$ \begin{align} \widehat{\theta}_{nq} \approx \frac{\sum_{k=1}^{K^Q}x_{k_q}P(\boldsymbol{y}_{n}|\boldsymbol{X}_k,\boldsymbol{\eta})\boldsymbol{w}(\boldsymbol{x}_{k})}{\sum_{k=1}^{K^Q}P(\boldsymbol{y}_{n}|\boldsymbol{X}_k,\boldsymbol{\eta}) \boldsymbol{w}(\boldsymbol{x}_{k})}. \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} \widehat{\theta}_{nq} \approx \frac{\sum_{k=1}^{K^Q}x_{k_q}P(\boldsymbol{y}_{n}|\boldsymbol{X}_k,\boldsymbol{\eta})\boldsymbol{w}(\boldsymbol{x}_{k})}{\sum_{k=1}^{K^Q}P(\boldsymbol{y}_{n}|\boldsymbol{X}_k,\boldsymbol{\eta}) \boldsymbol{w}(\boldsymbol{x}_{k})}. \end{align} $$

Therefore,

![]() $\widehat {\theta }_{nq}$

depends not only on the quadrature node vector and its weights but also on the data

$\widehat {\theta }_{nq}$

depends not only on the quadrature node vector and its weights but also on the data

![]() $\boldsymbol {y}_{n}$

and the item parameters

$\boldsymbol {y}_{n}$

and the item parameters

![]() $\boldsymbol {\eta }$

. In other words, when the response data for the nth examinee arrive, the examinee’s latent traits can be quickly updated using EAP estimation, provided that the item parameters have already been updated. Given the real-time estimates of the item parameters

$\boldsymbol {\eta }$

. In other words, when the response data for the nth examinee arrive, the examinee’s latent traits can be quickly updated using EAP estimation, provided that the item parameters have already been updated. Given the real-time estimates of the item parameters

![]() $\widehat {\boldsymbol {\eta }}_{n-1}$

, the formula for updating the ability parameters is given by

$\widehat {\boldsymbol {\eta }}_{n-1}$

, the formula for updating the ability parameters is given by

$$ \begin{align} \widehat{\boldsymbol{\theta}}_{n} = \sum_{k=1}^{K^Q}\boldsymbol{x}_{k}f_{k}(\widehat{\boldsymbol{\eta}}_{n-1}). \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} \widehat{\boldsymbol{\theta}}_{n} = \sum_{k=1}^{K^Q}\boldsymbol{x}_{k}f_{k}(\widehat{\boldsymbol{\eta}}_{n-1}). \end{align} $$

3.3 Implementation of stochastic Newton online estimation algorithms

The specific algorithmic flow of the online parameter estimation method in the IRT framework is outlined in Algorithm 1.

4 Theoretical properties

The convergence properties of the recursive SNA are crucial for ensuring the theoretical performance, practical stability, and efficiency of the algorithm. While some algorithms are guaranteed to converge in theory, they may require very small step sizes, leading to long convergence time before reaching the optimal solution. By deriving the convergence properties, we can better quantify these performance aspects, which aids in selecting appropriate parameters and optimization strategies. In this section, we derive the consistency, convergence rate, and asymptotic normality of parameter estimation using the TASNA.

Consider that the arriving response data vector

![]() $\boldsymbol {y} = (y_{1}, \ldots , y_{J})^\top $

from an examinee consists of independent Bernoulli random variables, where each response

$\boldsymbol {y} = (y_{1}, \ldots , y_{J})^\top $

from an examinee consists of independent Bernoulli random variables, where each response

![]() $y_j$

follows

$y_j$

follows

![]() $Bernoulli(\pi (\Theta ^{\top }\boldsymbol {\eta }_j))$

, with

$Bernoulli(\pi (\Theta ^{\top }\boldsymbol {\eta }_j))$

, with

![]() $\Theta = (1, \theta _{1}, \ldots , \theta _{Q})^{\top }$

representing the examinee’s latent traits, and

$\Theta = (1, \theta _{1}, \ldots , \theta _{Q})^{\top }$

representing the examinee’s latent traits, and

![]() $\boldsymbol {\eta }_j = (d_j, a_{j1}, \ldots , a_{jQ})^{\top }$

denoting the item parameters for

$\boldsymbol {\eta }_j = (d_j, a_{j1}, \ldots , a_{jQ})^{\top }$

denoting the item parameters for

![]() $j = 1, \ldots , J$

. The objective function, using the Gauss–Hermite quadrature method, is defined as follows:

$j = 1, \ldots , J$

. The objective function, using the Gauss–Hermite quadrature method, is defined as follows:

$$ \begin{align} G(\boldsymbol{\eta})&=\mathbb{E}[\ell(\boldsymbol{y},\boldsymbol{\eta})]=\mathbb{E}\left[-\log\sum_{k=1}^{K^Q} P(\boldsymbol{y}|\boldsymbol{X}_k,\boldsymbol{\eta})\boldsymbol{w}(\boldsymbol{x}_{k})\right]. \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} G(\boldsymbol{\eta})&=\mathbb{E}[\ell(\boldsymbol{y},\boldsymbol{\eta})]=\mathbb{E}\left[-\log\sum_{k=1}^{K^Q} P(\boldsymbol{y}|\boldsymbol{X}_k,\boldsymbol{\eta})\boldsymbol{w}(\boldsymbol{x}_{k})\right]. \end{align} $$

It is important to note that all theoretical results in this study are based on the numerically approximated objective function

![]() $G(\boldsymbol {\eta })$

, meaning the algorithm optimizes

$G(\boldsymbol {\eta })$

, meaning the algorithm optimizes

![]() $G(\boldsymbol {\eta })$

rather than the exact marginal log-likelihood. Under certain standard convexity assumptions on G, our goal can equivalently be stated as minimizing

$G(\boldsymbol {\eta })$

rather than the exact marginal log-likelihood. Under certain standard convexity assumptions on G, our goal can equivalently be stated as minimizing

![]() $G(\boldsymbol {\eta })$

to obtain the item parameter estimates, that is,

$G(\boldsymbol {\eta })$

to obtain the item parameter estimates, that is,

Thus, the gradient and Hessian matrix for the jth item parameter

![]() $\boldsymbol {\eta }_j$

are given by

$\boldsymbol {\eta }_j$

are given by

$$ \begin{align} \nabla G(\boldsymbol{\eta}_{j})&=\mathbb{E}\left[\nabla_j \ell(\boldsymbol{y},\boldsymbol{\eta})\right]=\mathbb{E}\left[\sum_{k=1}^{K^Q}f_{k}(\boldsymbol{\eta})\left(\pi(\boldsymbol{X}_k^{\top}\boldsymbol{\eta}_{j})-y_{j}\right)\boldsymbol{X}_k\right], \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} \nabla G(\boldsymbol{\eta}_{j})&=\mathbb{E}\left[\nabla_j \ell(\boldsymbol{y},\boldsymbol{\eta})\right]=\mathbb{E}\left[\sum_{k=1}^{K^Q}f_{k}(\boldsymbol{\eta})\left(\pi(\boldsymbol{X}_k^{\top}\boldsymbol{\eta}_{j})-y_{j}\right)\boldsymbol{X}_k\right], \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} \nabla^2G(\boldsymbol{\eta}_{j}) &=\mathbb{E}\left[\nabla^2_j \ell(\boldsymbol{y},\boldsymbol{\eta})\right]=\mathbb{E}\left[\sum_{k=1}^{K^Q}f_{k}(\boldsymbol{\eta})\pi(\boldsymbol{X}_k^{\top}\boldsymbol{\eta}_{j})(1-\pi(\boldsymbol{X}_k^{\top}\boldsymbol{\eta}_{j}))\boldsymbol{X}_k\boldsymbol{X}_k^{\top}\right] \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} \nabla^2G(\boldsymbol{\eta}_{j}) &=\mathbb{E}\left[\nabla^2_j \ell(\boldsymbol{y},\boldsymbol{\eta})\right]=\mathbb{E}\left[\sum_{k=1}^{K^Q}f_{k}(\boldsymbol{\eta})\pi(\boldsymbol{X}_k^{\top}\boldsymbol{\eta}_{j})(1-\pi(\boldsymbol{X}_k^{\top}\boldsymbol{\eta}_{j}))\boldsymbol{X}_k\boldsymbol{X}_k^{\top}\right] \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} &=\mathbb{E}\left[\sum_{k=1}^{K^Q}\frac{f_{k}(\boldsymbol{\eta})}{4(\cosh (\boldsymbol{X}_k^{\top}\boldsymbol{\eta}_{j}/2))^2}\boldsymbol{X}_k\boldsymbol{X}_k^{\top}\right], \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} &=\mathbb{E}\left[\sum_{k=1}^{K^Q}\frac{f_{k}(\boldsymbol{\eta})}{4(\cosh (\boldsymbol{X}_k^{\top}\boldsymbol{\eta}_{j}/2))^2}\boldsymbol{X}_k\boldsymbol{X}_k^{\top}\right], \end{align} $$

where

$$ \begin{align} f_{k}(\boldsymbol{\eta})=\frac{\prod_{j=1}^J\pi(\boldsymbol{X}_k^{\top}\boldsymbol{\eta}_{j})^{y_{j}}\left(1-\pi(\boldsymbol{X}_k^{\top}\boldsymbol{\eta}_{j})\right)^{1-y_{j}}\boldsymbol{w}(\boldsymbol{x}_{k})}{\sum_{k=1}^{K^Q}\prod_{j=1}^J\pi(\boldsymbol{X}_k^{\top}\boldsymbol{\eta}_{j})^{y_{j}}\left(1-\pi(\boldsymbol{X}_k^{\top}\boldsymbol{\eta}_{j})\right)^{1-y_{j}}\boldsymbol{w}(\boldsymbol{x}_{k})}. \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} f_{k}(\boldsymbol{\eta})=\frac{\prod_{j=1}^J\pi(\boldsymbol{X}_k^{\top}\boldsymbol{\eta}_{j})^{y_{j}}\left(1-\pi(\boldsymbol{X}_k^{\top}\boldsymbol{\eta}_{j})\right)^{1-y_{j}}\boldsymbol{w}(\boldsymbol{x}_{k})}{\sum_{k=1}^{K^Q}\prod_{j=1}^J\pi(\boldsymbol{X}_k^{\top}\boldsymbol{\eta}_{j})^{y_{j}}\left(1-\pi(\boldsymbol{X}_k^{\top}\boldsymbol{\eta}_{j})\right)^{1-y_{j}}\boldsymbol{w}(\boldsymbol{x}_{k})}. \end{align} $$

To ensure the effectiveness and convergence of the TASNA, the following regularity assumptions are imposed:

-

(A1) The item parameters and the latent ability parameters of all examinees are bounded.

-

(A2) The latent ability parameters

$\boldsymbol {\theta }$

of each examinee are independent and follow the same multivariate normal distribution with a mean vector of

$\boldsymbol {\theta }$

of each examinee are independent and follow the same multivariate normal distribution with a mean vector of

$\boldsymbol {0}$

and identity covariance matrix

$\boldsymbol {0}$

and identity covariance matrix

$\boldsymbol {I}_Q$

.

$\boldsymbol {I}_Q$

. -

(A3) There exists a positive constant

$c_f>0$

such that, for any item parameter vector

$c_f>0$

such that, for any item parameter vector

$\boldsymbol {\xi }$

, where

$\boldsymbol {\xi }$

, where $$ \begin{align*}\lambda_{\min}\left(\sum_{k=1}^{K^Q}f_k(\boldsymbol{\xi})\boldsymbol{X}_k\boldsymbol{X}_k^{\top}\right)\geq c_f>0,\end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*}\lambda_{\min}\left(\sum_{k=1}^{K^Q}f_k(\boldsymbol{\xi})\boldsymbol{X}_k\boldsymbol{X}_k^{\top}\right)\geq c_f>0,\end{align*} $$

$c_f$

is independent of the sample size n and the index j.

$c_f$

is independent of the sample size n and the index j.

Assumption (A1) guarantees the boundedness of the parameter space, which ensures that both the gradient and the Hessian matrix of the objective function remain bounded within this space. Combined with Assumption (A2), since the latent abilities satisfy

![]() $\boldsymbol {\theta }\sim \mathcal {N}(\boldsymbol {0},\boldsymbol {I}_Q)$

, the Gauss–Hermite quadrature nodes are symmetrically distributed around the origin and possess finite fourth-order moments. These properties are essential for the stability of the numerical integration process. Assumption (A3) further ensures the positive definiteness of the Hessian matrix

$\boldsymbol {\theta }\sim \mathcal {N}(\boldsymbol {0},\boldsymbol {I}_Q)$

, the Gauss–Hermite quadrature nodes are symmetrically distributed around the origin and possess finite fourth-order moments. These properties are essential for the stability of the numerical integration process. Assumption (A3) further ensures the positive definiteness of the Hessian matrix

![]() $\nabla ^2 G(\boldsymbol {\eta }_j)$

, which is critical for guaranteeing the uniqueness of the solution to the minimization problem. Together, these assumptions ensure that the objective function

$\nabla ^2 G(\boldsymbol {\eta }_j)$

, which is critical for guaranteeing the uniqueness of the solution to the minimization problem. Together, these assumptions ensure that the objective function

![]() $G(\boldsymbol {\eta })$

is twice continuously differentiable and that its minimizer is unique. This satisfies the two key regularity conditions proposed by Bercu et al. (Reference Bercu, Godichon and Portier2020). Under these assumptions, we first present the consistency of the item parameter estimates

$G(\boldsymbol {\eta })$

is twice continuously differentiable and that its minimizer is unique. This satisfies the two key regularity conditions proposed by Bercu et al. (Reference Bercu, Godichon and Portier2020). Under these assumptions, we first present the consistency of the item parameter estimates

![]() $\widetilde {\boldsymbol {\eta }}$

,

$\widetilde {\boldsymbol {\eta }}$

,

![]() $\widehat {\boldsymbol {\eta }}$

, and the consistency of the Hessian matrix estimates

$\widehat {\boldsymbol {\eta }}$

, and the consistency of the Hessian matrix estimates

![]() $\overline {\boldsymbol {S}}_n$

in the following theorem.

$\overline {\boldsymbol {S}}_n$

in the following theorem.

Theorem 1 (Consistency).

Under Assumptions (A1)–(A3), for all

![]() $\gamma \in (\frac {1}{2},1)$

and

$\gamma \in (\frac {1}{2},1)$

and

![]() $0< \beta < \gamma - \frac {1}{2}$

, the following result holds:

$0< \beta < \gamma - \frac {1}{2}$

, the following result holds:

and for

![]() $j=1,\ldots ,J$

,

$j=1,\ldots ,J$

,

where

![]() $\overline {\boldsymbol {S}}_{n,j} = \frac {1}{n+1} \boldsymbol {S}_{n,j}$

,

$\overline {\boldsymbol {S}}_{n,j} = \frac {1}{n+1} \boldsymbol {S}_{n,j}$

,

![]() $\boldsymbol {S}_j = \nabla ^2 G(\boldsymbol {\eta }_{j})$

,

$\boldsymbol {S}_j = \nabla ^2 G(\boldsymbol {\eta }_{j})$

,

![]() $\widetilde {\boldsymbol {\eta }}_{n} = (\widetilde {\boldsymbol {\eta }}_{n,1}^{\top }, \dots , \widetilde {\boldsymbol {\eta }}_{n,J}^{\top })^{\top }$

,

$\widetilde {\boldsymbol {\eta }}_{n} = (\widetilde {\boldsymbol {\eta }}_{n,1}^{\top }, \dots , \widetilde {\boldsymbol {\eta }}_{n,J}^{\top })^{\top }$

,

![]() $\widehat {\boldsymbol {\eta }}_{n} = (\widehat {\boldsymbol {\eta }}_{n,1}^{\top }, \dots , \widehat {\boldsymbol {\eta }}_{n,J}^{\top })^{\top }$

, and

$\widehat {\boldsymbol {\eta }}_{n} = (\widehat {\boldsymbol {\eta }}_{n,1}^{\top }, \dots , \widehat {\boldsymbol {\eta }}_{n,J}^{\top })^{\top }$

, and

![]() $\boldsymbol {\eta } = (\boldsymbol {\eta }_{1}^{\top }, \dots , \boldsymbol {\eta }_{J}^{\top })^{\top }$

.

$\boldsymbol {\eta } = (\boldsymbol {\eta }_{1}^{\top }, \dots , \boldsymbol {\eta }_{J}^{\top })^{\top }$

.

The proof of Theorem 1 is provided in Section C.1 of the Supplementary Material. Theorem 1 establishes that, as the sample size n tends to infinity, the item parameter estimates obtained using TASNA converge to the true parameter values

![]() $\boldsymbol {\eta }$

. Additionally, we demonstrate the consistency of the Hessian matrix estimate. We then present the convergence rates for both the item parameter estimates and the Hessian matrix estimates. This analysis of convergence rates offers insight into how rapidly the estimates approach their true values as the sample size n increases.

$\boldsymbol {\eta }$

. Additionally, we demonstrate the consistency of the Hessian matrix estimate. We then present the convergence rates for both the item parameter estimates and the Hessian matrix estimates. This analysis of convergence rates offers insight into how rapidly the estimates approach their true values as the sample size n increases.

Theorem 2 (Convergence rate).

Under Assumptions (A1)–(A3), for all

![]() $\gamma \in (\frac {1}{2},1)$

and

$\gamma \in (\frac {1}{2},1)$

and

![]() $0< \beta < \gamma - \frac {1}{2}$

, we have the following results:

$0< \beta < \gamma - \frac {1}{2}$

, we have the following results:

Furthermore, for

![]() $j=1,\ldots ,J$

,

$j=1,\ldots ,J$

,

where

![]() $\overline {\boldsymbol {S}}_{n,j}=\frac {1}{n+1}\boldsymbol {S}_{n,j}$

,

$\overline {\boldsymbol {S}}_{n,j}=\frac {1}{n+1}\boldsymbol {S}_{n,j}$

,

![]() $\boldsymbol {S}_j=\nabla ^2G(\boldsymbol {\eta }_{j})$

,

$\boldsymbol {S}_j=\nabla ^2G(\boldsymbol {\eta }_{j})$

,

![]() $\widetilde {\boldsymbol {\eta }}_{n}=(\widetilde {\boldsymbol {\eta }}_{n,1}^{\top },\dots ,\widetilde {\boldsymbol {\eta }}_{n,J}^{\top })^{\top }$

,

$\widetilde {\boldsymbol {\eta }}_{n}=(\widetilde {\boldsymbol {\eta }}_{n,1}^{\top },\dots ,\widetilde {\boldsymbol {\eta }}_{n,J}^{\top })^{\top }$

,

![]() $\widehat {\boldsymbol {\eta }}_{n}=(\widehat {\boldsymbol {\eta }}_{n,1}^{\top },\dots ,\widehat {\boldsymbol {\eta }}_{n,J}^{\top })^{\top }$

, and

$\widehat {\boldsymbol {\eta }}_{n}=(\widehat {\boldsymbol {\eta }}_{n,1}^{\top },\dots ,\widehat {\boldsymbol {\eta }}_{n,J}^{\top })^{\top }$

, and

![]() $\boldsymbol {\eta }=(\boldsymbol {\eta }_{1}^{\top },\dots ,\boldsymbol {\eta }_{J}^{\top })^{\top }$

.

$\boldsymbol {\eta }=(\boldsymbol {\eta }_{1}^{\top },\dots ,\boldsymbol {\eta }_{J}^{\top })^{\top }$

.

The proof of Theorem 2 is provided in Section C.2 of the Supplementary Material. Theorem 2 demonstrates that the convergence rate of the averaged parameter estimates is faster than that of the non-averaged parameter estimates. This implies that averaging the parameters during the iterative process enhances the convergence rate, enabling quicker stabilization of the parameter estimates as the sample size increases.

The convergence rate of the averaged parameter estimates is

![]() $O\left (\frac {\log n}{n}\right )$

, which indicates that the error in the averaged parameter estimates decreases at a rate proportional to

$O\left (\frac {\log n}{n}\right )$

, which indicates that the error in the averaged parameter estimates decreases at a rate proportional to

![]() $\frac {\log n}{n}$

as the sample size n increases. This indicates that as the number of samples grows, the averaged estimates will steadily approach the true parameter values. The convergence rate of the Hessian matrix estimate is

$\frac {\log n}{n}$

as the sample size n increases. This indicates that as the number of samples grows, the averaged estimates will steadily approach the true parameter values. The convergence rate of the Hessian matrix estimate is

![]() $O\left (\frac {1}{n^{2\beta }}\right )$

, implying that the error in the Hessian matrix estimate decreases rapidly as the sample size increases. The speed of this reduction depends on the value of

$O\left (\frac {1}{n^{2\beta }}\right )$

, implying that the error in the Hessian matrix estimate decreases rapidly as the sample size increases. The speed of this reduction depends on the value of

![]() $\beta $

. The closer

$\beta $

. The closer

![]() $\beta $

is to

$\beta $

is to

![]() $\gamma - \frac {1}{2}$

, the faster the convergence rate. This makes the algorithm highly efficient for large sample sizes, as it provides accurate Hessian estimates that improve with n. Therefore, in practical applications,

$\gamma - \frac {1}{2}$

, the faster the convergence rate. This makes the algorithm highly efficient for large sample sizes, as it provides accurate Hessian estimates that improve with n. Therefore, in practical applications,

![]() $\beta $

should be chosen to be close to

$\beta $

should be chosen to be close to

![]() $\gamma - \frac {1}{2}$

to maximize efficiency.

$\gamma - \frac {1}{2}$

to maximize efficiency.

Finally, to establish a reliable statistical foundation for model estimation under the TASNA and to provide a theoretical basis for subsequent statistical inference, we present the asymptotic normality of the parameter estimates obtained using TASNA, as stated in the following theorem.

Theorem 3 (Asymptotic normality).

Under Assumptions (A1)–(A3), for

![]() $j = 1, \ldots , J$

, the following asymptotic normality holds:

$j = 1, \ldots , J$

, the following asymptotic normality holds:

where

![]() $\boldsymbol {S}_j=\nabla ^2G(\boldsymbol {\eta }_{j})$

.

$\boldsymbol {S}_j=\nabla ^2G(\boldsymbol {\eta }_{j})$

.

The proof of Theorem 3 is provided in Section C.3 of the Supplementary Material. Theorem 3 implies that, as the sample size n increases, the scaled difference between the estimated parameters and the true parameters converges in distribution to a normal distribution with a zero mean and covariance matrix

![]() $\boldsymbol {S}_j^{-1}$

. This result establishes a foundation for conducting statistical inference, such as constructing confidence intervals or performing hypothesis testing, on the estimated parameters.

$\boldsymbol {S}_j^{-1}$

. This result establishes a foundation for conducting statistical inference, such as constructing confidence intervals or performing hypothesis testing, on the estimated parameters.

Remark 1. From Equation (20), the online EAP estimates of the ability parameters depend on the updated item parameters. Theorem 2 establishes the convergence properties of the updated item parameters. Consequently, based on Theorem 2 and Lemma 3 in the Supplementary Material, we can derive the convergence rate of the online EAP estimates of the ability parameters, denoted as

![]() $\widehat {\boldsymbol {\theta }}_{n}=\sum _{k=1}^{K^Q}\boldsymbol {x}_{k}f_{k}(\widehat {\boldsymbol {\eta }}_{n-1})$

, relative to the EAP estimates of the ability parameters computed using the true item parameter values

$\widehat {\boldsymbol {\theta }}_{n}=\sum _{k=1}^{K^Q}\boldsymbol {x}_{k}f_{k}(\widehat {\boldsymbol {\eta }}_{n-1})$

, relative to the EAP estimates of the ability parameters computed using the true item parameter values

![]() $\boldsymbol {\eta }$

, denoted as

$\boldsymbol {\eta }$

, denoted as

![]() $\widehat {\boldsymbol {\theta }}_{n}^{*}=\sum _{k=1}^{K^Q}\boldsymbol {x}_{k}f_{k}(\boldsymbol {\eta })$

, as follows:

$\widehat {\boldsymbol {\theta }}_{n}^{*}=\sum _{k=1}^{K^Q}\boldsymbol {x}_{k}f_{k}(\boldsymbol {\eta })$

, as follows:

This result demonstrates that the error between

![]() $\widehat {\boldsymbol {\theta }}_{n}$

and

$\widehat {\boldsymbol {\theta }}_{n}$

and

![]() $\widehat {\boldsymbol {\theta }}_{n}^{*}$

decreases as the sample size n increases, and the rate of this decrease is

$\widehat {\boldsymbol {\theta }}_{n}^{*}$

decreases as the sample size n increases, and the rate of this decrease is

![]() $O(\frac {\log n}{n})$

.

$O(\frac {\log n}{n})$

.

Remark 2. Based on Theorem 3 and Equation (28), the standard error of the estimated parameters can be naturally obtained by taking the inverse of the Hessian matrix estimated at the final sample size and extracting the square roots of its diagonal elements:

$$ \begin{align} SE(\widehat{\boldsymbol{\eta}}_{n,j})=\sqrt{\text{diag}\left(\frac{1}{n}\overline{\boldsymbol{S}}_{n,j}^{-1}\right)}, \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} SE(\widehat{\boldsymbol{\eta}}_{n,j})=\sqrt{\text{diag}\left(\frac{1}{n}\overline{\boldsymbol{S}}_{n,j}^{-1}\right)}, \end{align} $$

where

![]() $\text {diag}(\cdot )$

denotes taking the diagonal elements of a matrix. This approach provides both a theoretically sound and practically implementable method for computing standard errors within the TSNA and TASNA frameworks.

$\text {diag}(\cdot )$

denotes taking the diagonal elements of a matrix. This approach provides both a theoretically sound and practically implementable method for computing standard errors within the TSNA and TASNA frameworks.

5 Simulation study

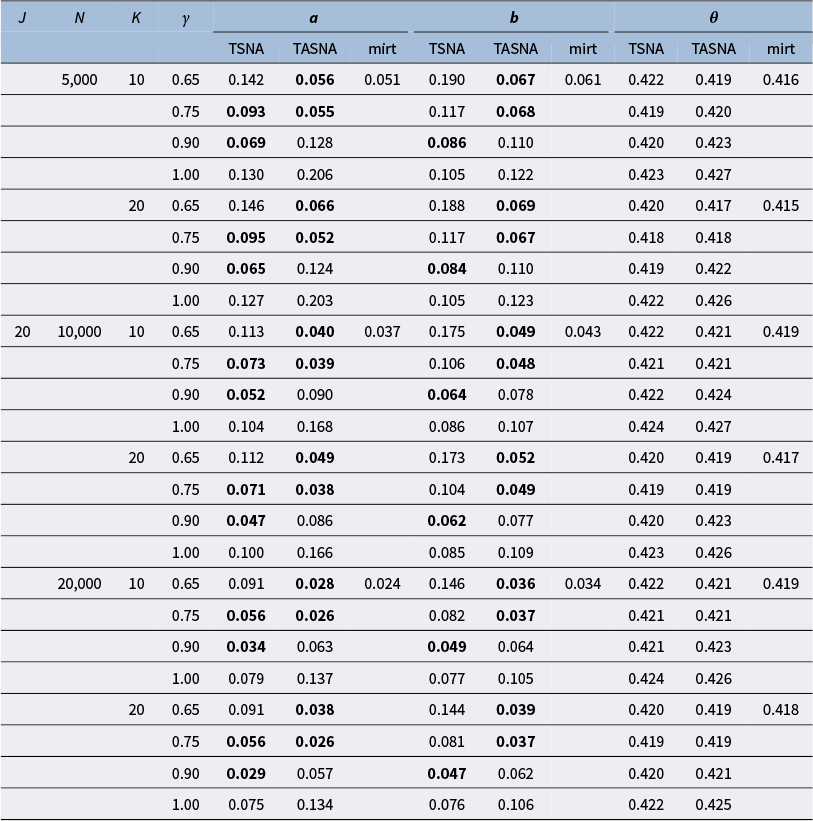

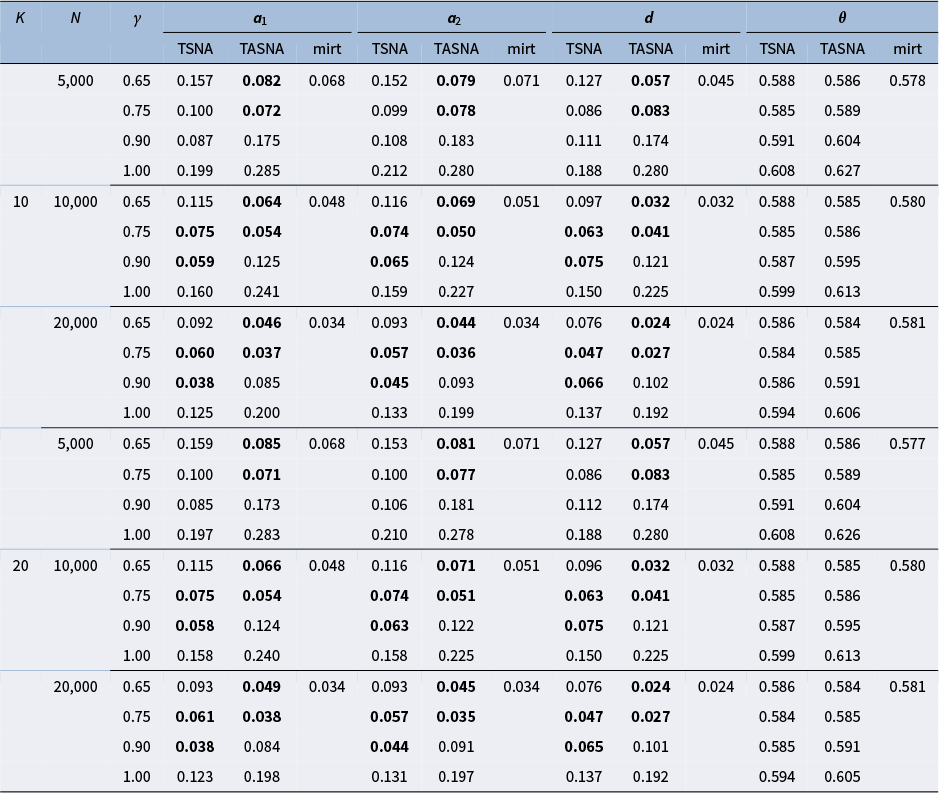

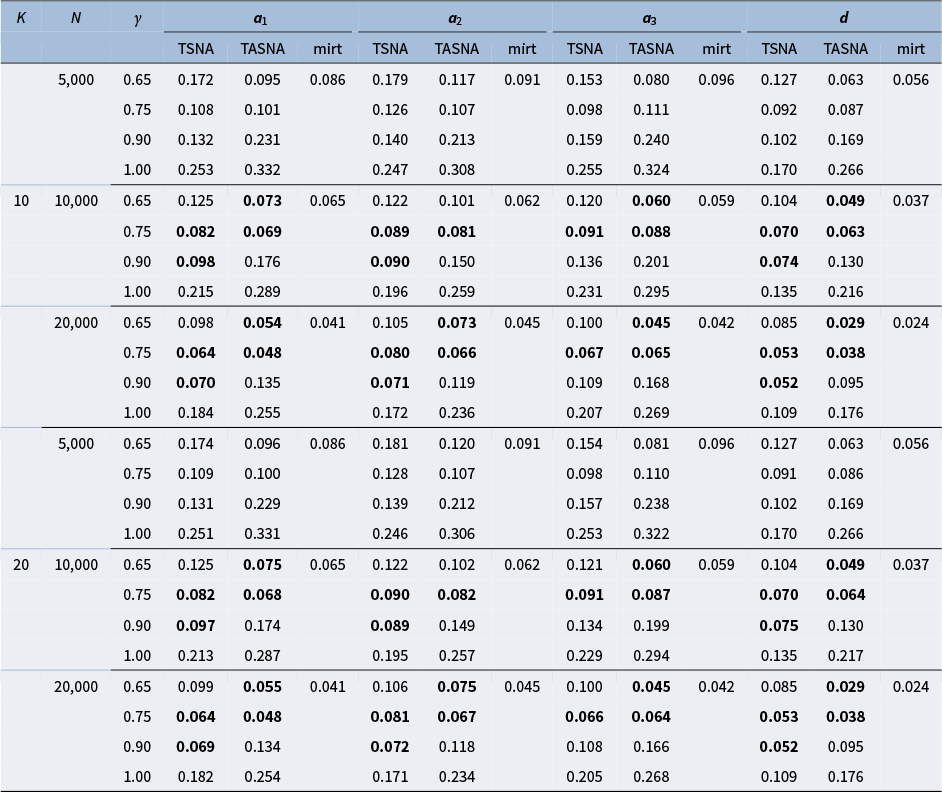

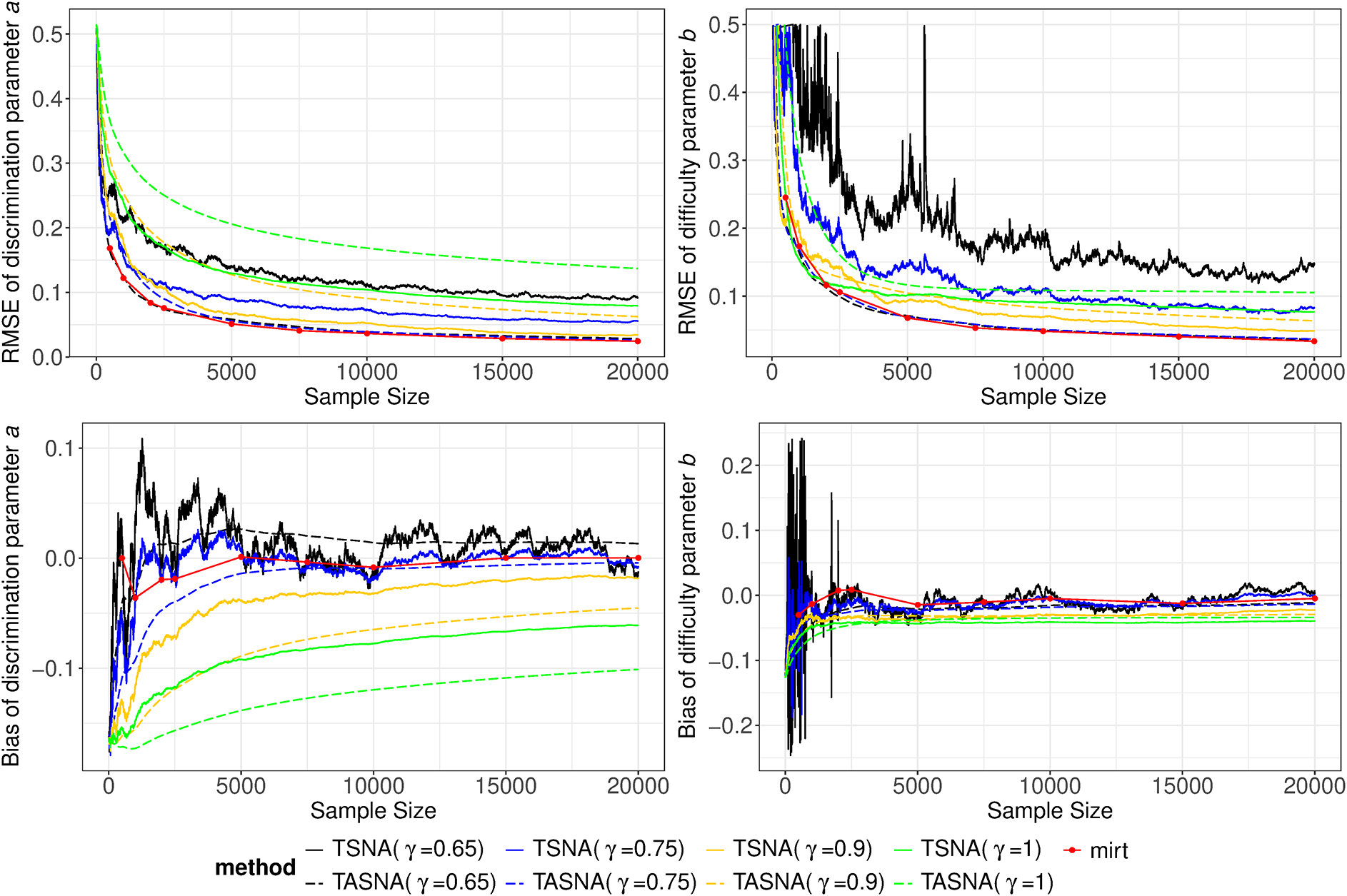

The simulation study aims to evaluate the effectiveness and practicality of the proposed online parameter estimation methods under the 2PL and M2PL models. We compare the performance of the TASNA and TSNA algorithms against the EM algorithm with fixed quadrature, evaluating algorithms in terms of bias, RMSE of parameter estimates, and computational time. The EM algorithm with fixed quadrature is implemented primarily using the mirt package in R (Chalmers, Reference Chalmers2012). The mirt package leverages optimization techniques and Rcpp to enhance computational efficiency. Rcpp enables the integration of C++ code into R, allowing computationally intensive tasks to be executed efficiently. To ensure a fair comparison of computational efficiency, the TASNA and TSNA were rewritten in C++ using Rcpp and subsequently called from R to compare with the EM algorithm implemented in the mirt package.

5.1 Simulation designs

Five factors were manipulated to vary different simulation conditions: (1) The number of examinees, i.e.,

![]() $n = (5,000, 10,000, 20,000)$

. (2) The number of items, i.e.,

$n = (5,000, 10,000, 20,000)$

. (2) The number of items, i.e.,

![]() $J = (20, 40)$

. (3) The dimensions of latent traits, i.e.,

$J = (20, 40)$

. (3) The dimensions of latent traits, i.e.,

![]() $Q = (1, 2, 3,4)$

.

$Q = (1, 2, 3,4)$

.

![]() $Q = 1$

represents the unidimensional 2PL model. (4) The number of Gauss–Hermite quadrature nodes, i.e.,

$Q = 1$

represents the unidimensional 2PL model. (4) The number of Gauss–Hermite quadrature nodes, i.e.,

![]() $K = (10, 20)$

. The number of Gauss–Hermite quadrature nodes significantly affects the accuracy of numerical integration and the convergence of the algorithm. By simulating and comparing model performance at different values of K, we aim to identify an appropriate number of nodes that balances accuracy and computational efficiency. (5) Different step sizes, i.e.,

$K = (10, 20)$

. The number of Gauss–Hermite quadrature nodes significantly affects the accuracy of numerical integration and the convergence of the algorithm. By simulating and comparing model performance at different values of K, we aim to identify an appropriate number of nodes that balances accuracy and computational efficiency. (5) Different step sizes, i.e.,

![]() $\gamma = (0.65, 0.75, 0.9, 1)$

. An appropriate step size can accelerate the algorithm’s convergence while ensuring its stability and enhancing the accuracy of the final solution. By comparing different step size settings, the optimal step size strategy can be determined. Each simulation condition was replicated 50 times.

$\gamma = (0.65, 0.75, 0.9, 1)$

. An appropriate step size can accelerate the algorithm’s convergence while ensuring its stability and enhancing the accuracy of the final solution. By comparing different step size settings, the optimal step size strategy can be determined. Each simulation condition was replicated 50 times.

5.2 Data generation and model identifiability conditions

We generated item response data for the 2PL model and M2PL model based on Equation (1) and Equation (2), respectively. To simplify the computation and enhance the interpretability of the model, we assumed that the latent ability dimensions are independent. This assumption also eliminates the indeterminacy of scale, which is a common practice in other research (e.g., Cui et al., Reference Cui, Wang and Xu2024). Therefore, the ability parameters

![]() $\theta _{iq}$

for each examinee i were sampled from a standard normal distribution

$\theta _{iq}$

for each examinee i were sampled from a standard normal distribution

![]() $N(0, 1)$

, where

$N(0, 1)$

, where

![]() $q = 1, \ldots , Q$

. Following Shang et al. (Reference Shang, Xu, Shan, Tang and Ho2023), for each item j and dimension q, the discrimination parameters

$q = 1, \ldots , Q$

. Following Shang et al. (Reference Shang, Xu, Shan, Tang and Ho2023), for each item j and dimension q, the discrimination parameters

![]() $a_{jq}$

were generated from the uniform distribution

$a_{jq}$

were generated from the uniform distribution

![]() $U(0.5, 2)$

, while the difficulty parameters

$U(0.5, 2)$

, while the difficulty parameters

![]() $b_j$

(for the 2PL model) and the intercept parameters

$b_j$

(for the 2PL model) and the intercept parameters

![]() $d_j$

(for the M2PL model) were generated from the standard normal distribution

$d_j$

(for the M2PL model) were generated from the standard normal distribution

![]() $N(0, 1)$

, for

$N(0, 1)$

, for

![]() $j = 1, \ldots , J$

and

$j = 1, \ldots , J$

and

![]() $q = 1, \ldots , Q$

.

$q = 1, \ldots , Q$

.

To ensure the identifiability of the 2PL model, we imposed constraints on the ability parameters by assuming that the population distribution of abilities follows a standard normal distribution. For the M2PL model, we applied the second constraint method proposed by Béguin and Glas (Reference Béguin and Glas2001). This method ensures identifiability by constraining the item parameters as follows: the first Q items’ intercept parameters

![]() $d_1, \ldots , d_Q$

are set to zero, and the discrimination parameter

$d_1, \ldots , d_Q$

are set to zero, and the discrimination parameter

![]() $a_{jq}$

is set to 1 when

$a_{jq}$

is set to 1 when

![]() $j = q$

and to 0 when

$j = q$

and to 0 when

![]() $j \neq q$

, for each

$j \neq q$

, for each

![]() $j = 1, \ldots , Q$

and

$j = 1, \ldots , Q$

and

![]() $q = 1, \ldots , Q$

. Meanwhile, the ability parameters are freely estimated.

$q = 1, \ldots , Q$

. Meanwhile, the ability parameters are freely estimated.

5.3 Parameter settings and initialization values

In the SNA, several parameters require adjustment, including

![]() $c_{\eta }$

,

$c_{\eta }$

,

![]() $c_{\beta }$

,

$c_{\beta }$

,

![]() $\beta $

, and the step size parameter

$\beta $

, and the step size parameter

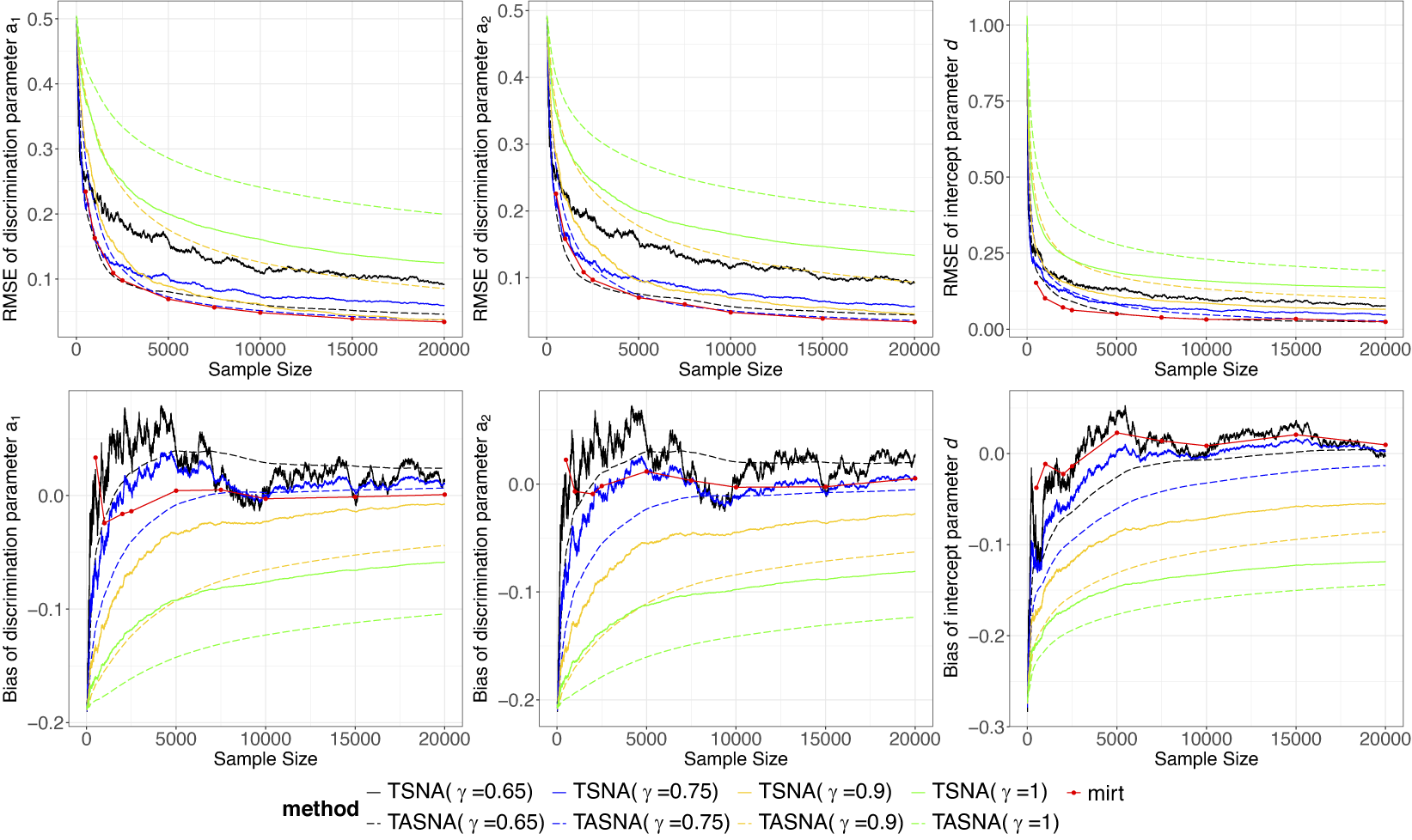

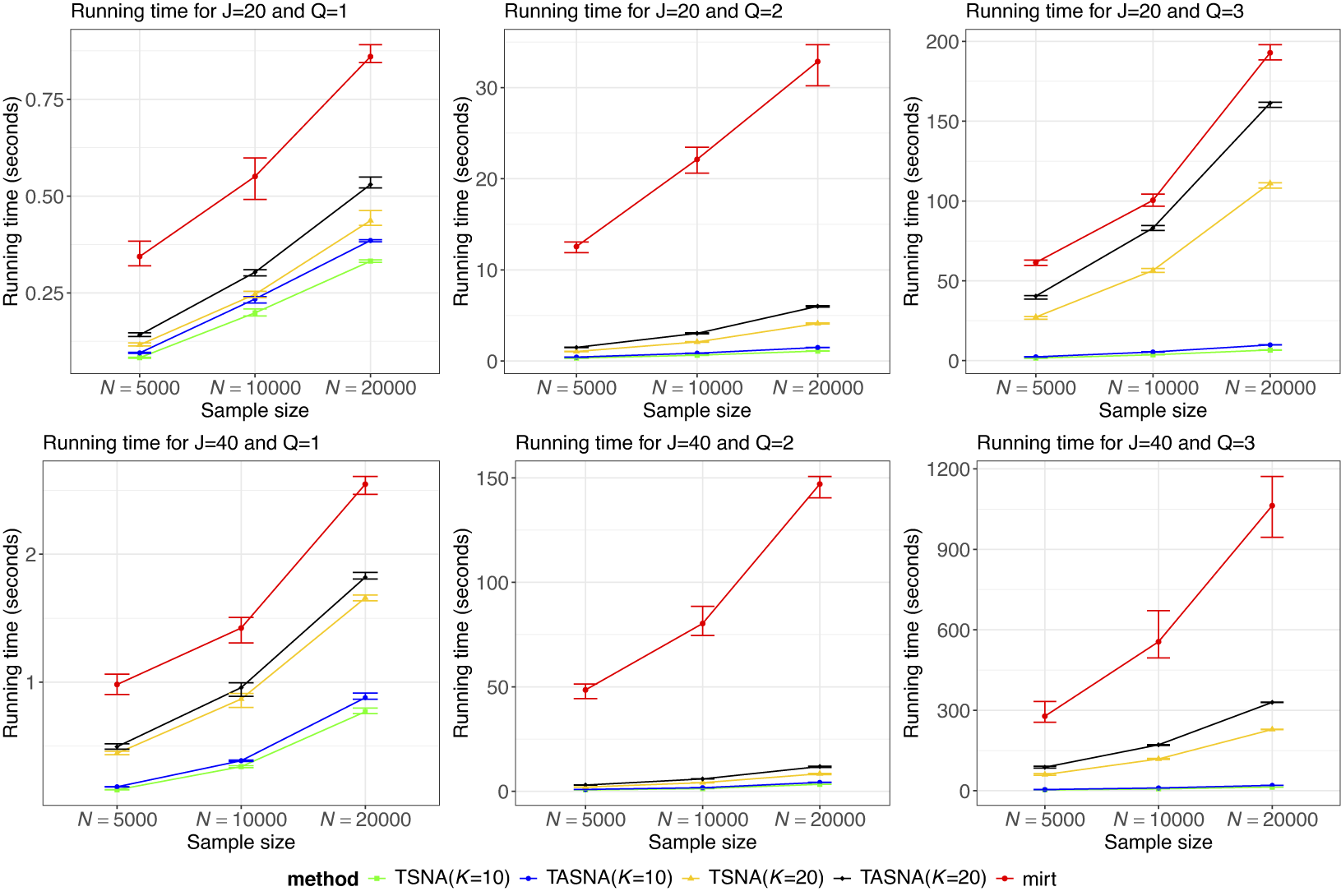

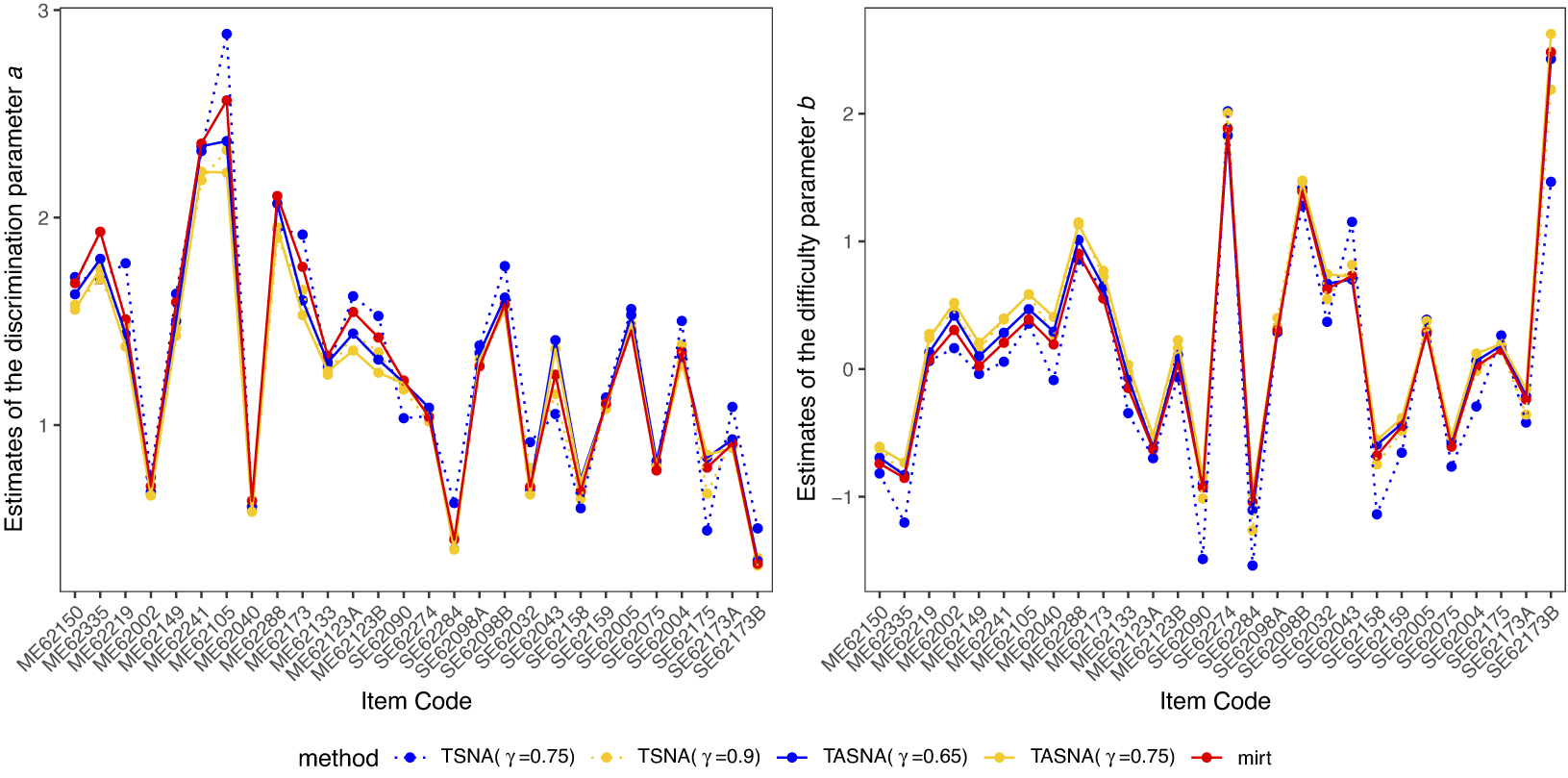

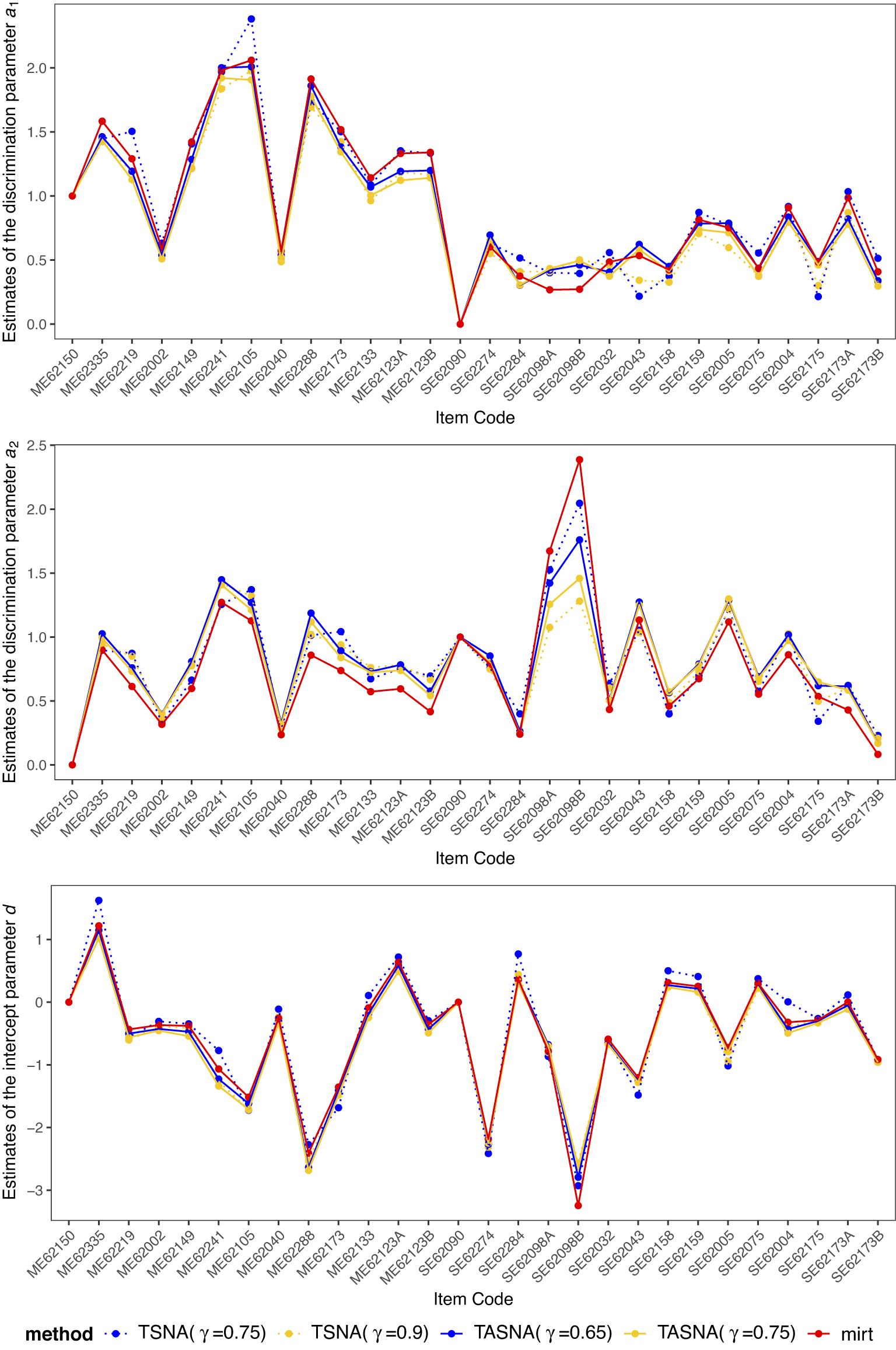

![]() $\gamma $