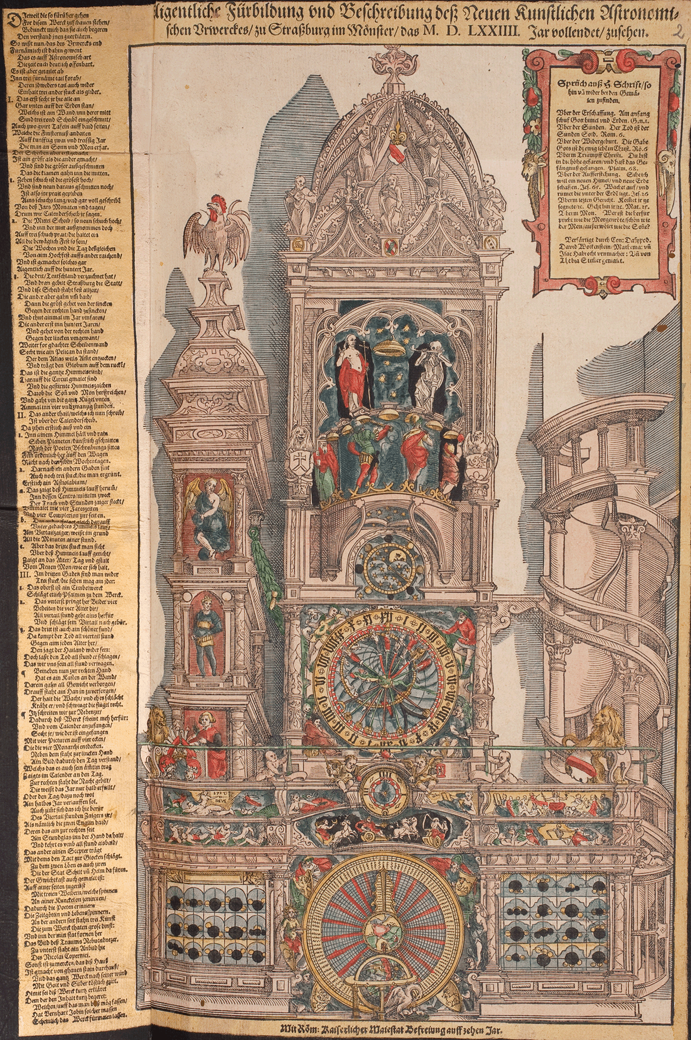

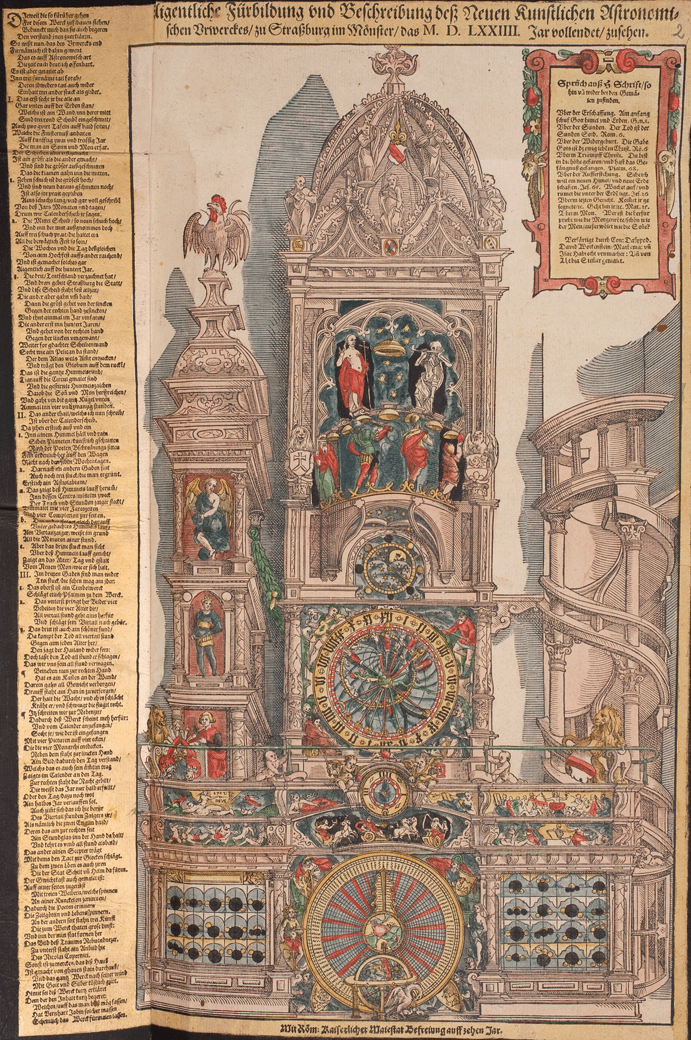

Bernhard Jobin (block-cutter) and unknown hand-colorist after Tobias Stimmer (designer), Aigentliche Furbildung vnd Beschreibung deß Neuen Kuunstlichen Astronomischen Urwerckes zu Straßburg im Mönster [detail], 1574 or later, hand-colored woodcut with letterpress, 37.9 × 21.5 cm. Endpaper in a copy of Daniel Specklin’s ARCHITECTVRA von Vestungen […] (Straßburg: Bernhard Jobin, 1589), Wolfenbüttel, Herzog August Bibliothek, H: N 180.2° Helmst. (2).

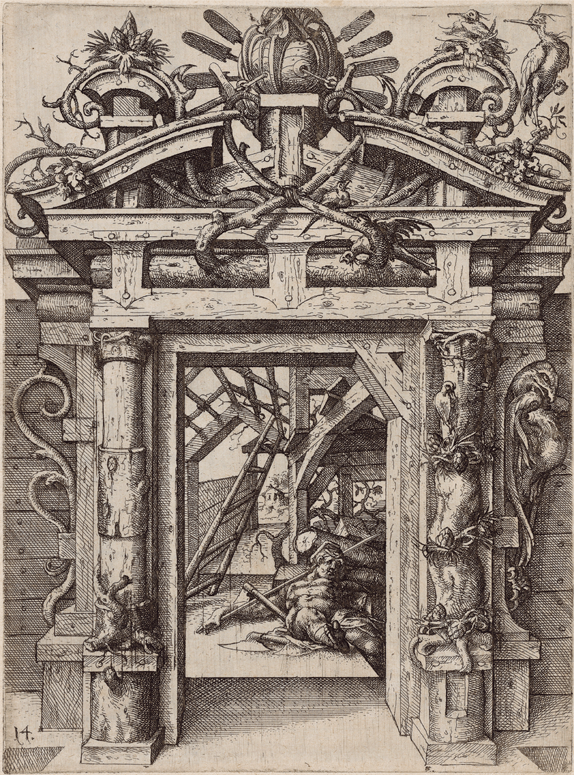

It is 1594, and architecture stands at a threshold between two epochs. Straßburg artist Wendel Dietterlin the Elder (c. 1550–1599) envisioned the juncture in an etching of a rustic portal for the second installment of his Architectura [Fig. 0.1], a treatise on architectural ornament that Dietterlin composed and illustrated with nearly two hundred etchings of his own design between c. 1590 and 1598.1 The printed portal’s rough-hewn posts allude to architecture’s mythical genesis in the arboreal hut. Its attic of twine-bound branches elicits the ancient German dwellings described by the Roman author Tacitus (56–120 ce).2 As physical constructions, both attic and portal evoke architecture’s long-standing history as the practice of devising and realizing buildings.

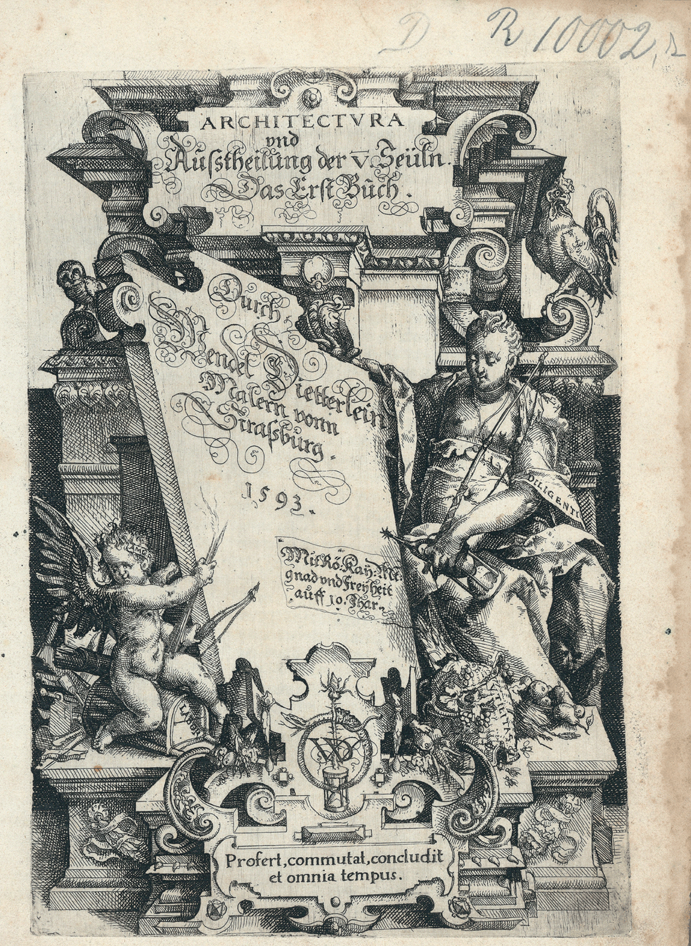

0.1 Wendel Dietterlin, Allegory of the Architectural Image, etched illustration in Dietterlin’s ARCHITECTVR von Portalen vnnd Thürgerichten mancherley arten. Das Annder Būch (Straßburg: Bernhard Jobin’s heirs, 1594), Strasbourg, Bibliothèque nationale et universitaire de Strasbourg, R.10.002,2, pl. 14.

But in the space beyond the portal, the world of building dissolves, ceding to a newer understanding of architecture as a medium. Through the threshold, one spies the timber skeleton of an unfinished interior. Its roofbeams merge at contradictory angles, affirming the mathematical logic of perspective, but flouting structural norms of building. Amidst the tangle, a carpenter has laid his axes and other tools of construction. His skillfully foreshortened, supine body resembles the prone figures of early German artisans’ handbooks and evokes the image-making of the dream-state.3 Envisaged through perspectival and oneiric conceits, the carpenter and his interior embody a pictorial understanding of architecture distinct from the world of construction with which the carpenter was conventionally associated.

In embodying the new, pictorial understanding of architecture, Dietterlin’s etching exemplifies what this book will call the “architectural image” – that is, a visualization of building, architectural ornament, the built environment, or architectonic qualities of nonarchitectural forms. The genre of the architectural image flourished during the fifteenth, sixteenth, and seventeenth centuries in Europe through media such as drawing, print, painting, and sculpture, which are today known as “figural arts,” and often manifested scientific, or, in early modern terms, “natural philosophical” knowledge, such as the representational technique of linear perspective. Dietterlin and his peers constructed architectural images by combining methods of visual research – that is, principled forms of inquiry that use the sensory data of vision – which had, over the previous century, grown indispensable to artistic and natural philosophical practice in Dietterlin’s milieu. In other words, the zone beyond the printed portal embodies a burgeoning concept of architecture as a medium not only for building, but also for describing the observed world.

This book probes the concomitant rise of artistic and scientific practices of visual research in sixteenth- and seventeenth-century architectural culture through the lens of Dietterlin’s Architectura (published 1593–1598) and the architectural images of its era. Dietterlin’s book, the foremost architectural treatise of the so-called German Renaissance, offered a guide to composing architectural designs in all artistic media by synthesizing artistic and natural philosophical modes of visual research.4 It accomplished this largely through images. In its completed state, Dietterlin’s treatise encompassed just sixteen pages of text and one hundred ninety-eight distinct architectural prints. Through its sparse prose and figure-laden architectural etchings, Dietterlin’s Architectura summarized a century of pictorial experimentation, in which sixteenth-century artists had applied artistic and natural philosophical methods of visual research to architectural design. That tradition found its center of gravity in northern Europe, which I take to mean the German-speaking lands, together with the Low Countries and France. There, artists, architects, and natural philosophers collaborated to form architectural images that revived an ancient ideal of architecture as both art and science despite existing at a distance from most vestiges of architectural antiquity. In the wake of Dietterlin’s Architectura, architects and artists in Habsburg colonies such as the Viceroyalty of Peru likewise came to promote the revival of architecture as both an art and a science by producing architectural images. And through works like the Architectura, Dietterlin and his peers in northern Europe and its colonial contact zones came to wield architectural images to propel developments in art and science.

The primary evidence underwriting this story is the universe of architectural images Dietterlin’s Architectura emulated, produced, and shaped in northern Europe and the Habsburg imperium. Though architectural images had existed since antiquity, it was only with the Renaissance that architecture became an autonomous subject of what we now call art. Such Renaissance architectural images could be two dimensional, such as architectural drawings or prints; three dimensional, such as architectural sculpture or decorative arts; or even four dimensional, such as automata or clocks that move over time. Indeed, while the anglophone understanding of “image” tends to connote two-dimensional works, Dietterlin’s Early New High German term, Bild, could also entail a picture, but more often described a three-dimensional body.5 Thus many of the works examined in the present book, including Dietterlin’s Architectura, unsettle present-day distinctions between media – for instance, sculptural prints that were published in two dimensions, assembled in three, and could be used as moving instruments in the fourth dimension of elapsing time. Yet despite its capacious medial parameters, the phrase “architectural image” as I use it encompasses a circumscribed range of subjects. Architectural images use architectural forms to probe themes of structure, order, and norms of visual representation.

The novel combination of subject matter and media embodied by architectural images catalyzed a fateful shift in the relationships between the figural arts, architecture, and natural philosophy. Between the eras of painter-architects and students of nature Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528) and Peter Paul Rubens (1577–1640), architectural images came to promote an ideal of research now termed “empiricism” – or the notion that knowledge derives from sensory experience.6 Dietterlin’s Architectura and its architectural images mark the apotheosis of that trend, in that they consolidated the artistic and natural philosophical practices of empirical visual research available to architecture around 1600. In visually synthesizing the empirical research practices of northern Europe and its colonial contact zones in architectural terms, Dietterlin’s Architectura transformed the architectural image from a genre that frequently represented natural philosophical concepts to an active conduit of natural philosophical inquiry. And that intervention proved instrumental to the emergence of architecture and science as the mutually enmeshed arts we know today.

Architectures of Description

Dietterlin’s Architectura was among the earliest architectural treatises to address natural philosophers such as anatomists, alchemists, and natural historians. Nevertheless, the artist’s investment in interdisciplinarity, or the idea that experience in one field can translate to another, was hardly novel for early modern Europe. Architectural culture – that is, the totality of materials, practices, and discourses relating to architecture – abounded with such exchanges. From the late Middle Ages until around 1600, architecture was still emerging as a profession in Europe, encompassing a shifting plurality of trades with manifold connections to other arts and sciences.7 Draftsmen, master-masons, carpenters, fortification experts, garden designers, engineers, humanist advisors, and patrons all claimed the title of “architect.”8 Building demanded collaboration between disparate construction experts, such as bricklayers and joiners, as well as various types of artisan, from façade painters to glaziers.9 Myriad exchanges between architecture and other visual arts flourished in architectural painting, intarsia, sgraffito, and other such works, which often incorporated architectural ornament.10 Micro-architecture, or architecture executed at a smaller scale than conventional building, likewise abounded in vessels, jewelry, pulpits, fountains, epitaphs, cenotaphs, and many other media.11 In addition, architects engaged in what we would now call “science,” manipulating geometrical formulae, honing technologies for managing materials, and devising machines from mills to automata.12 All these exchanges required disparate practitioners to develop shared forms of communication. The architectural image emerged as a genre between the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, as individuals involved in architecture, art, and science forged new modes of visual description that allowed them to communicate through architectural forms.

An important basis for such commerce between architecture, art, and natural philosophy during early modernity was the fact that many in Europe saw image-making as a source of knowledge, and believed that such understanding could traverse artistic and scientific disciplines.13 One of the earliest texts to link acts of image-making with knowledge was what is now known as the “aesthetic excursus” of Dürer’s Vier Bücher von menschlicher Proportion (Four Books on Human Proportion), first published in 1528. Here Dürer wrote that “[The artist] must possess a powerful practice [brauch] if he wants to fulfill [viewers’] desires[.] It would also be useful to him, if he has understanding [verstünd] of what is the correct way of measuring and what is not, that he can show [such principles] in his work.”14 Dürer saw artistic practice as a form of experiential knowledge that allows artists to visualize abstract principles such as theories of proportion. The Nuremberg artist moreover regarded practical skill and understanding not as opposing elements within a theory/practice dichotomy, but as overlapping, interdependent components of artistic skill.15 By Dietterlin’s day, Dürer’s concept of artistic practice as a conduit of knowledge had come to undergird dialogues between art, architecture, and science.16 Whenever the present book refers to “practice,” particularly the practice of visual research, it is in the Dürerian sense of an active or material instantiation of knowledge.

Even before Dürer linked artistic practice with understanding, figural artists in Europe had begun to hone new techniques for investigating nature such as the firsthand observation of flora and fauna, and had started to develop novel pictorial genres such as still life and landscape.17 Origins of those trends can be traced to the milieu of Flemish painter Jan van Eyck (c. 1390–1441). In paintings such as the artist’s c. 1424–1440 Madonna in the Church [Fig. 0.2], a meticulous rendering of an outsize Virgin and Child within a rayonnant nave, van Eyck and his peers developed a new pictorial idiom, culled from minute observations of natural bodies, human-made forms, and architectural spaces. By visualizing their observations through fastidious renderings of materials, surfaces, textures, and structures, they heralded a naturalistic mode of pictorial description that some scholars today regard as specific to northern Europe.18 As northern artists came to use images to describe the world with precision, they entered a visual dialogue with natural philosophers.19 Scholars have in fact argued that the rise of artistic naturalism in northern Europe helped to catalyze the Scientific Revolution.20

Between the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, the architectural image emerged alongside still life and landscape as one of the novel genres of naturalistic description in European art. It developed, on the one hand, as artists like van Eyck began to foreground architecture as a subject in painting and other figural media. Because architectural images like van Eyck’s Madonna in the Church fostered mathematical modes of representation such as linear perspective, they buoyed the North’s flourishing culture of pictorial naturalism.21 Architectural images made by artists became vital conduits for describing the observed world, and even came to thematize visual experience as such. On the other hand, the genre of the architectural image matured as architects began to treat images – and especially the then-ascendant media of drawing and printing on paper – as integral components of architectural practice.

But why was the advent of the graphic arts so vital to the emergence of architectural image-making by architects? First, the rise of drawing on paper made it cheaper and easier to draft and transmit images of architecture, to assemble a visual record of built environments, and to compare far-flung architectures by means other than memory. Print only expanded such advantages. The art of printing impressions on paper had evolved in Europe during the early fifteenth century, followed by movable type in the 1430s. Both innovations recast visual communication. With the rise of print, text and images could be produced and combined through standardized processes, and travel cheaply and swiftly across vast distances.22 Print allowed texts and images previously conveyed via error-prone modes of speech or manual copying to achieve a more fixed and enduring state, and to proliferate with greater consistency.23 As a result, it offered new opportunities for circulating architectural knowledge, and enabled architects to draw and print architectural images in order to study, plan, and circulate representations of architectural forms.24 Since both drawing and printing on paper proved crucial to the emergence of the architectural image as a genre, architectural drawings and prints play a vital role in the present book.

Various circumstances, including the idiosyncratic roles of architectural prints and drawings north of the Alps, conspired to make northern Europe the epicenter for architectural images with natural philosophical themes. First, whereas in Italy architectural images were primarily valued for producing or recording ingenious or artful designs, northern Europe prized the genre for showing brilliant technical solutions, for cleverly visualizing information, or for having been crafted in an ingenious way. Second, although northern Europeans both scrupulously documented and invented local remnants of antiquity, the region lacked a significant body of classical ruins.25 Knowledge about classical architecture most often filtered north through drawings, printed images, and texts – in other words, in a mediated way. For example, Jan Gossart drew the west side of the Roman Colosseum in 1509 during his brief journey to Rome [Fig. 0.3], but continued for decades after his return to the Netherlands to adapt his firsthand studies of classical architecture into paintings as a sign of humanist learning and the imperial pretensions of his Netherlandish patrons.26 The mediated status of such visualizations meant that northern Europe’s images of ancient architecture did not merely serve as representations of ruins. They also probed the nature of visual evidence and cultivated in their viewers a greater awareness of the mediated status of images. Finally, unlike their Italian counterparts, artists, architects, and natural philosophers in northern Europe who sought insights about the workings of the world tended to accord greater authority to nature than to antiquity.27 The preference nurtured in makers and consumers of architectural images a taste for the visual rhetoric of firsthand observation. As a result, architectural images in northern Europe cultivated a rhetoric of firsthand observation that also pertained to the descriptive goals of natural philosophers – even though it was sometimes only rhetoric.

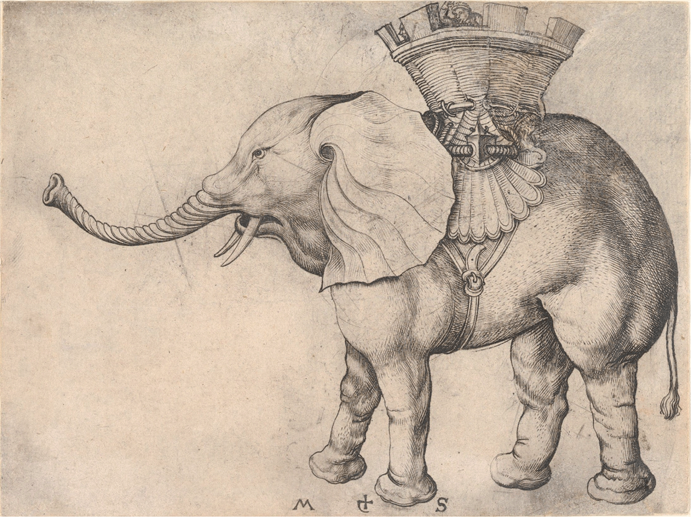

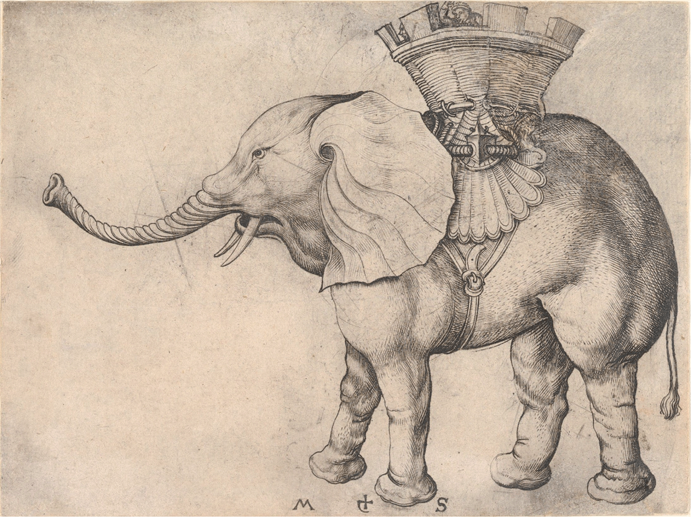

For instance, The Elephant, which Dietterlin’s Straßburg forebear Martin Schongauer (1430–1491) engraved around 1483 [Fig. 0.4], depicts an African pachyderm with a crenellated howdah and two riders – elephant and castle imagery that dated to the era of Alexander the Great (356–323 bce).28 While Schongauer likely researched the appearance of elephants using images and textual descriptions, the artist posed his Elephant almost as if it were a record of a live encounter with his subject.29 He described the howdah’s straps, buckle, and mount as well as the elephant’s tufted tail hair, saggy knees, and craning trunk with deliberate burin marks, using the pleats of the saddle to echo the ridges in the elephant’s trunk and ears. In other words, Schongauer leveraged engraving’s expressive richness to create a vivid depiction of the elephant and its architectural accessory, an image that could model further zoological and architectural images. Indeed, printed images such as Schongauer’s Elephant and, later, the etchings of Dietterlin’s Architectura, provided artists with a consistent basis for forming and reproducing conventions of both pictorial naturalism and architectural design.30 Print married the pictorial ambitions of artists who studied nature to the descriptive aspirations of those who scrutinized and devised architectural forms.

In conversation with the era’s expanding pictorial naturalism and multiplying print media, natural philosophers in fifteenth- and sixteenth-century Europe joined artists in developing visual strategies for describing nature. Like artists, natural philosophers often deployed tactics of firsthand observation or relied on images that claimed to derive from such encounters. For instance, writers from anatomist Andreas Vesalius (1514–1564) to botanist Leonhart Fuchs (1501–1566) authored some of the earliest anatomical and botanical publications based on empirical visual research, texts that stated that their images could serve as valuable conduits of learned natural philosophical knowledge.31 Crucially, such natural philosophers collated authoritative bodies of visual evidence by collaborating with artists and even, as in the case of Zurich polymath Conrad Gessner (1516–1565), by making images themselves.32 The artistic pursuits that increasingly underwrote sixteenth-century natural philosophical knowledge propelled northern Europe’s new pictorial naturalism and helped to spawn an empirical turn in natural philosophy.

What counted as empiricism for early modern natural philosophy would not be regarded as empiricism today. In addition to sponsoring firsthand depictions of nature, natural philosophers synthesized visual and textual descriptions of distinct specimens to form new, normative images of such phenomena as diseases, constellations, and plant and animal species.33 One can observe the emerging regard for such mixing of sources by studying an image of an elephant from the 1551 volume of Gessner’s Historiæ Animalium (Histories of Animals) [Fig. 0.5], whose illustrations, the author stated, were taken ad vivum, or “from the life.”34 Gessner helped form the images of his Historiæ Animalium by gathering and collating pictorial, textual, and oral sources, relying on techniques of compilation and translation long practiced in Renaissance scholarship.35 So much is evident in the many similarities between Gessner’s elephant and Schongauer’s pachyderm [see Fig. 0.4]. Gessner’s print reprises the exacting style of Schongauer’s engraving, but omits its howdah, fortifying the illusion that the image represents a creature observed in firsthand zoological research.36 The apparent discord between Gessner’s claims about the empirical origins of the Historiæ Animalium’s images and the practices of copying, collation, and adaptation that in fact undergird its prints affirms that, for sixteenth-century individuals, empiricism was an epistemic ethos and a pictorial rhetoric as much as a philosophical rationale for firsthand visual research. Schongauer and Gessner’s elephants embodied the idea that sensory observations gain significance when contextualized within received or a priori knowledge – a research orientation Nancy Siraisi and Gianna Pomata have called “learned empiricism.”37

0.5 Conrad Gessner?, Elephant, woodcut illustration in Gessner’s CONRADI GESNERI medici Tigurini Historiæ Animalium Lib. I. de Quadrupedibus uiuiparis. (Zurich: Christoph Froschauer, 1551), Zurich, Zentralbibliothek Zürich, NNN 41 | F, p. 410.

Throughout the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, techniques of learned empiricism likewise came to shape the visual research practices of architecture. Just as natural philosophers mingled received knowledge with firsthand observation to form images of nature, humanists applied a combination of textual exegesis and firsthand study to consolidate authoritative versions of ancient architectural writing and projections of its lost illustrations.38 Authors and architects in the decades around 1500 likewise began to scavenge and synthesize visual evidence from built and ruined architecture, texts, and nature to describe types of architectural forms and to fashion canonical images for them.39 Those who conducted empirical research about architecture moreover formed their research questions and interpreted empirical evidence such as drawings of ruins made on-site through the lens of received knowledge, including textual and oral traditions. In this sense, the learned empiricism of sixteenth-century architectural culture resembled that of contemporary art and natural philosophy, forging another bridge between the descriptive ambitions of the three fields.

An outstanding example of architecture’s intensifying engagement with natural philosophy debuted in Straßburg soon after Dietterlin settled there in 1570. Between 1571 and 1574, engineer-mathematician Conrad Dasypodius (1531–1601) resumed work on a new Astronomical Clock, first devised for the Straßburg Cathedral interior by mathematician Christian Herlin (d. 1562) around 1547 to replace a fourteenth-century forerunner, but temporarily abandoned for various reasons until the 1570s. Dasypodius received support from diverse artisans and technicians, including clockmakers Isaac (1544–1620) and Josias Habrecht (1552–1575), astronomer-musician David Wolckenstein (1534–1592), and painters Josias (1555–after 1574) and Tobias Stimmer (1539–1584).40 In 1575, Tobias depicted the project in a monumental woodblock print cut by Bernhard Jobin (c. 1543–1593) [Fig. 0.6], whose press would print multiple installments of Dietterlin’s Architectura. The woodcut celebrates a clock that told local, historical, and cosmic time while synchronizing various forms of natural philosophical expertise within an architectural framework.41 Beholding the Astronomical Clock, Dietterlin and his Straßburg contemporaries witnessed architecture synthesizing artistic, mathematical, and astronomical knowledge.42

0.6 Bernhard Jobin (block-cutter) and unknown hand-colorist after Tobias Stimmer (designer), Aigentliche Fürbildung vnd Beschreibung deß Neuen Kuunstlichen Astronomischen Urwerckes zu Straßburg im Mönster, 1574 or later, hand-colored woodcut with letterpress, 37.9 × 21.5 cm. Endpaper in a copy of Daniel Specklin’s ARCHITECTVRA von Vestungen […] (Straßburg: Bernhard Jobin, 1589), Wolfenbüttel, Herzog August Bibliothek, H: N 180.2° Helmst.

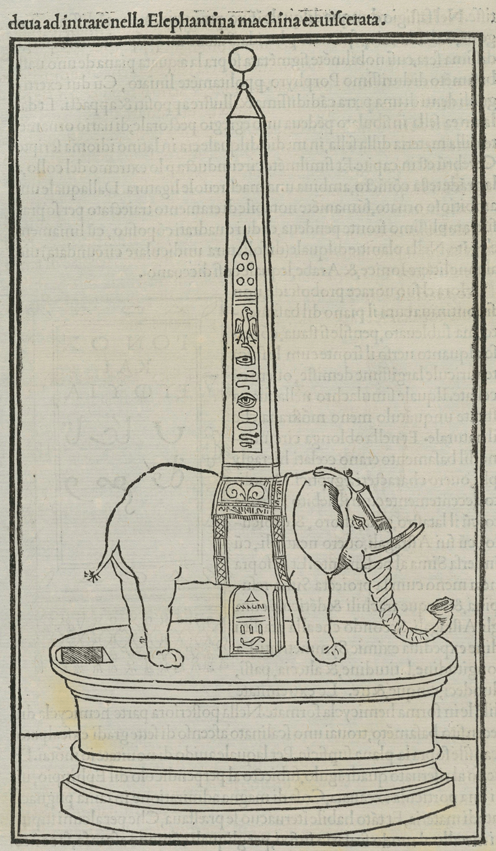

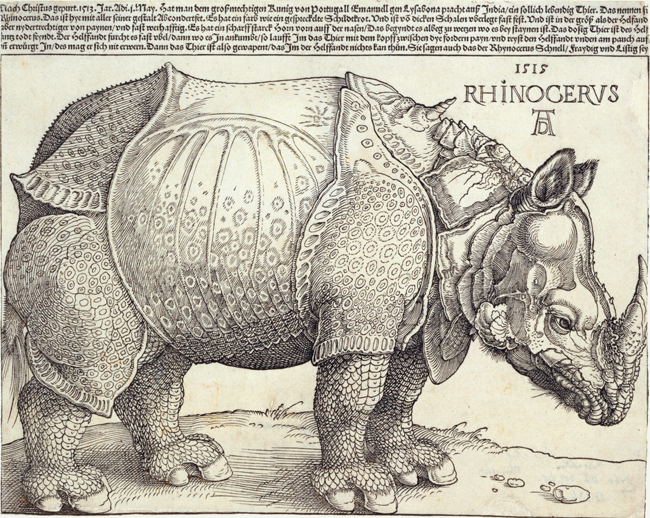

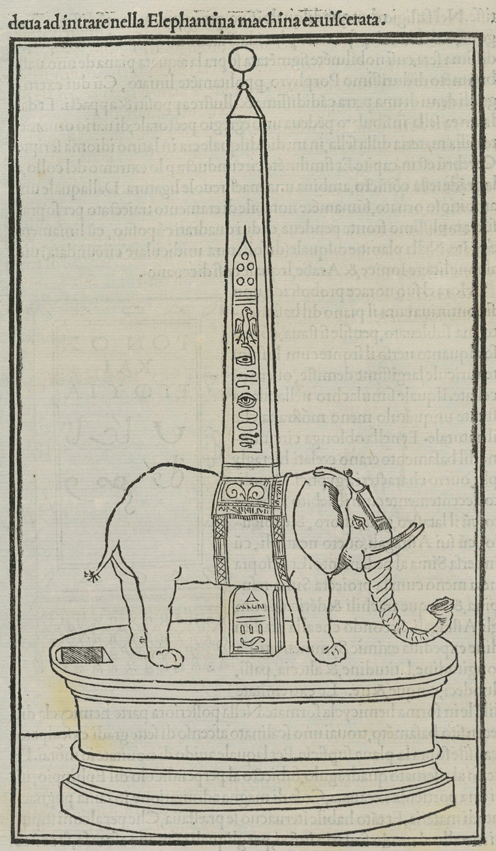

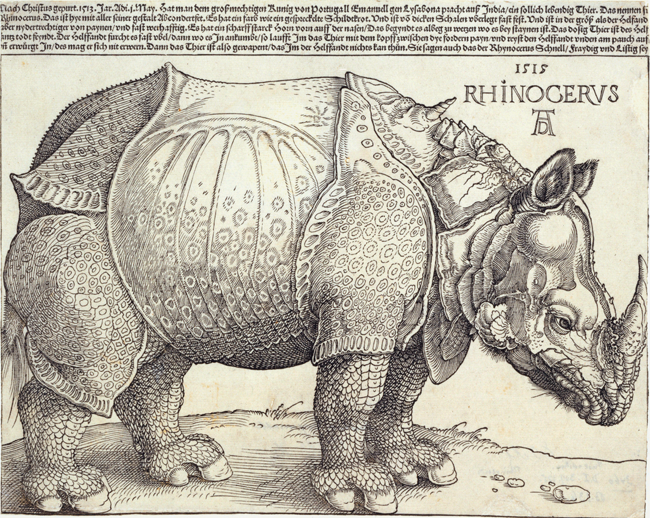

Forged in an era rife with collaboration between artists, architects, and natural philosophers, Dietterlin’s Architectura etchings visualize themes from diverse natural philosophical disciplines. The treatise pictures mythological figures that embody astronomical as well as alchemical entities, moving bodies that project concepts from mechanics and fauna conversant with contemporary zoology – for instance, the elephant before a fireplace in the Architectura of 1598 [Fig. 0.7]. To outfit his Architectura with such imagery, Dietterlin adapted and combined architectural as well as natural philosophical sources. The artist must have derived the idea to include an elephant motif in his architectural book from Francesco Colonna’s (d. 1527) 1499 Hypnerotomachia Poliphili (The Strife of Love in the Dream of Poliphilus), a dream narrative-cum-romance outfitted with this and other fantastic architecture [Fig. 0.8].43 At the same time, Dietterlin’s elephant engages zoological sources. With its unnatural, forward-bending legs, the beast amalgamates the backwards-jointed appendages of Schongauer’s and Gessner’s pachyderms [see Figs 0.4 and 0.5] with the corporeal proportions and cleft feet of Dürer’s Rhinoceros of 1515 [Fig. 0.9], another icon of natural historical description whose plated body has seemed architectonic to at least one modern scholar.44 In this and the other Architectura etchings, Dietterlin amalgamated multiple architectural and natural philosophical images in order to underscore the architectonic elements of natural philosophical imagery and to synthesize, pictorially, the visual research of architecture and natural philosophy. Toiling at the end of a century in which the architectural image came to embody the confluence of visual research in art, architecture, and natural philosophy, Dietterlin authored his Architectura as a pictorial retrospective and apotheosis of that tradition.

0.7 Wendel Dietterlin, Elephant Hearth, etched illustration in Dietterlin’s ARCHITECTVRA von Außtheilung, Symmetria vnd Proportion der Fünff Seulen […] (Nuremberg: Hubrecht and Balthasar Caymox, 1598), Zurich, Zentralbibliothek Zürich, Rx 12: c,2 | F, pl. 13.

As much as architectural images like the etchings of Dietterlin’s Architectura reflected natural philosophical knowledge, they also did something more novel. Namely, they transformed architectural forms from mere elements of building into models for describing natural phenomena such as the nature of space, the behavior of light, the qualities of materials, the tectonics of complex structures, and the mechanics of moving bodies. Dietterlin’s Architectura etchings exposed tactics for figuring three-dimensional space in two dimensions, the interior structures of the human body, the chemical simulation of materials, and the appearance of bodies in motion.45 If architecture such as the Straßburg Astronomical Clock embodied intricate networks of materials and labor as well as complex syntaxes and grammars of forms, images of such architecture offered strategies for visualizing hierarchies, typologies, and systems. Sixteenth-century natural philosophers likewise thirsted for image-making tactics capable of describing the forms, structures, and relationships in nature. Makers of architectural images like Stimmer and Dietterlin infused architectural culture not only with scientific imagery, but also with practices of visual research and image-making central to natural philosophy.

Consequently, the architectural image and its aptitude for visualizing formal qualities, relationships, and norms catalyzed a new rapport between architectural culture and natural philosophy. Just as makers of architectural images in the fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries had initially looked to the images of natural philosophers for descriptive strategies, natural philosophers came, by the middle of the sixteenth century, to adopt architecture’s evolving pictorial research techniques. Natural historians such as Gessner, who synthesized normative images of animal, vegetable, or mineral specimens and described the relationships between such species, drew on architects’ tactics for organizing bodies of visual research. Their strategies included the collation of images of ancient ruins or architectural ornaments across albums of drawings and prints or printed, illustrated treatises, as well as methods for describing systems of conventional, measured forms such as the architectural Orders. By the seventeenth century, practitioners of natural philosophy from François Blondel (1618–1686) to Christopher Wren (1632–1723) had come to rely on architectural images for key strategies of visual research and pictorial description.

In the architectural images of early modernity, both architectural and natural philosophical modes of visual inquiry came to be forged, tested, and revised. They constitute what Peter Galison and Pamela O. Long have both called “trading zones”: spaces where disparate paradigms of manual practice and knowledge-formation interact, and thereby transform.46 As a trading zone, the architectural image channeled influence in multiple directions. If the genre began by witnessing the impact of art and natural philosophy upon architectural strategies of visual description, the sixteenth century saw the waxing influence of architectural images upon the pictorial research tactics of art and natural philosophy. Indeed, whereas sixteenth-century architects had often entered natural philosophical discourses via architectural images, natural philosophers after 1600 pursued and wrote about architecture, using architectural images both as evidence and as vehicles of argumentation. In Dietterlin’s time, the architectural image grew from a genre that took cues from art and natural philosophy into a crucible for the evolving visual strategies of the new sciences.

Picturing Architectural Interdisciplinarity: The Vitruvian Tradition

Early modern artists, architects, and natural philosophers could find common ground in the architectural image because they all vaunted an ancient theory concerning the convergence of the visual arts and sciences in architecture. In the only architecture book from Roman antiquity to survive to the Renaissance, De architectura libri decem (Ten Books on Architecture), architect Marcus Vitruvius Pollio (80–70 bce–after c. 15 bce) had, like Dürer, asserted the fundamental contiguity of artistic theory and practice. Vitruvius claimed that the architect’s “[…] expertise is born both of practice [fabrica] and of reasoning [ratiocinatio],” stating further that “practice is the constant, repeated exercise of the hands by which the work is brought to completion in whatever medium is required for the proposed design. Reasoning, however, is what can demonstrate and explain the proportions of completed works skillfully and systematically.”47 Vitruvius conceived architectural practice as an experienced habit that achieves results through various artistic media, and architectural reason as the ability to explain the theoretical principles of architecture. By posing fabrica and ratiocinatio as integral components of architectural expertise, his De architectura laid foundations for Dürerian notions of artisanal knowledge and presaged Dietterlin’s exploration of architectural images as conduits for natural philosophical knowledge.

Indeed, Vitruvius had framed the dyad of fabrica and ratiocinatio as a basis for extensive relationships between architecture and other arts and sciences, asserting that “The architect’s expertise is enhanced by many disciplines and various sorts of specialized knowledge; all the works executed using these other skills are evaluated by his seasoned judgment.”48 Vitruvius consequently claimed that architects should master geometry, optics, and draftsmanship, and know the principles of history, music, law, philosophy, mathematics, anatomy, medicine, meteorology, and astronomy.49 In other words, De architectura encouraged architects to study figural arts such as painting and sculpture as well as other humanistic and scientific disciplines in a programmatic, liberal education.50 Vitruvius moreover argued that “The divisions of architecture itself are three: construction, gnomonics (the making of sundials) and mechanics”51 – an eminently technical conception of architecture that supported Dietterlin and other early moderns’ efforts to link that medium with natural philosophy. De architectura’s account of the architect’s heterogeneous forms of empirical and rational knowledge and fields of technical engagement served to define, for posterity, Vitruvius’s take on the scope and nature of architecture as a medium.52

As the accessibility of Vitruvius’s De architectura grew through fifteenth- and sixteenth-century publications, translations, and commentaries, it suffused Renaissance understandings of architectural knowledge. With the revival of De architectura, Vitruvian ideals of the architect as a liberally educated individual, and of architecture as a discipline embedded in various other visual arts and sciences, entrenched itself in Renaissance Europe. The disciplines Vitruvius identified as key competencies for architects – anatomy, medicine, meteorology, and astronomy – had increasingly come to fall, once again, under the auspices of architecture.53 Vitruvian principles of interdisciplinarity found durable expression in Renaissance architectural projects like the Straßburg Astronomical Clock, and, more ephemerally, collaborations between artists, architects, and natural philosophers that gave rise to such structures. When natural philosophers-cum-architecture enthusiasts such as Dasypodius cooperated with artists and technicians such as the Stimmers and Wolckenstein, they consciously emulated Vitruvius’s ideals of architectural practice and saw their work as a continuation of the ancient architect’s intellectual project.54 The rebirth of Vitruvius’s De architectura and its interdisciplinary understanding of architecture nurtured the waxing rapport between art, architecture, and natural philosophy. In this sense, classical principles and antiquarian imperatives guided the interdisciplinary orientation of Renaissance architectural culture.

Few sixteenth-century Vitruvian texts developed more profound visions of architecture as the conjunction of art and science than medical practitioner Walther Hermann Ryff’s (c. 1500–1548) textbook of artistic and architectural practices, the Architectur of 1547, and his groundbreaking, annotated German translation of De architectura published in 1548, Vitruvius Teutsch (German Vitruvius).55 Ryff used the preambles of Architectur and German Vitruvius to pose Vitruvian interdisciplinarity as architecture’s defining feature, emphasizing that

[…] in this case Architecture should not be understood according to its customary meaning, as the varied work of stonemasons, bricklayers, and the like, whose work and help the experienced and apt Architectus employs as useful Instruments or tools. Rather (according to the opinion and teachings of the most ancient and famous Architecti, Vitruvius) this little word, “architecture,” should be understood as an art ornamented by many other arts, such that he, who is experienced in it, can, according to a certain sound reason, and a good understanding of the work, and clever inventiveness, judge or evaluate all other artisans.56

The ideal architect, in other words, integrates knowledge from multiple arts and sciences.

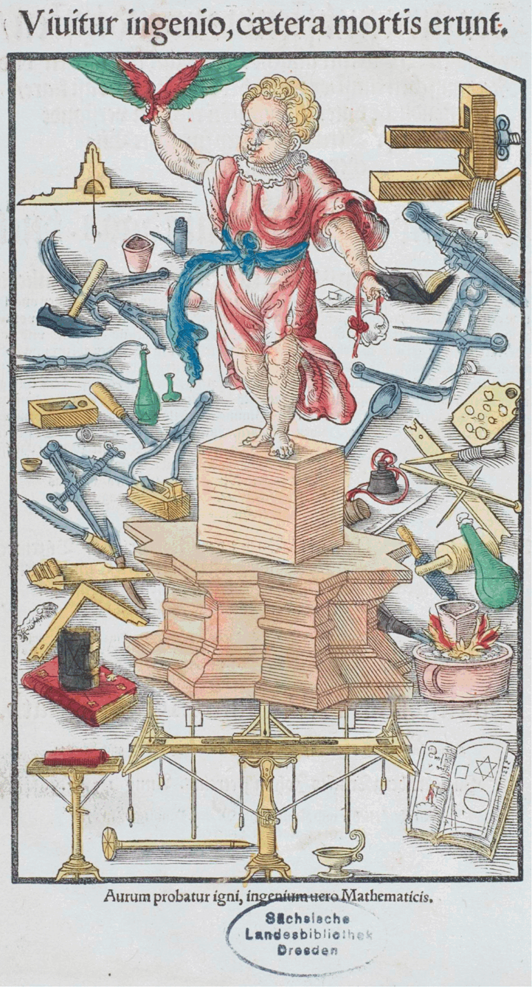

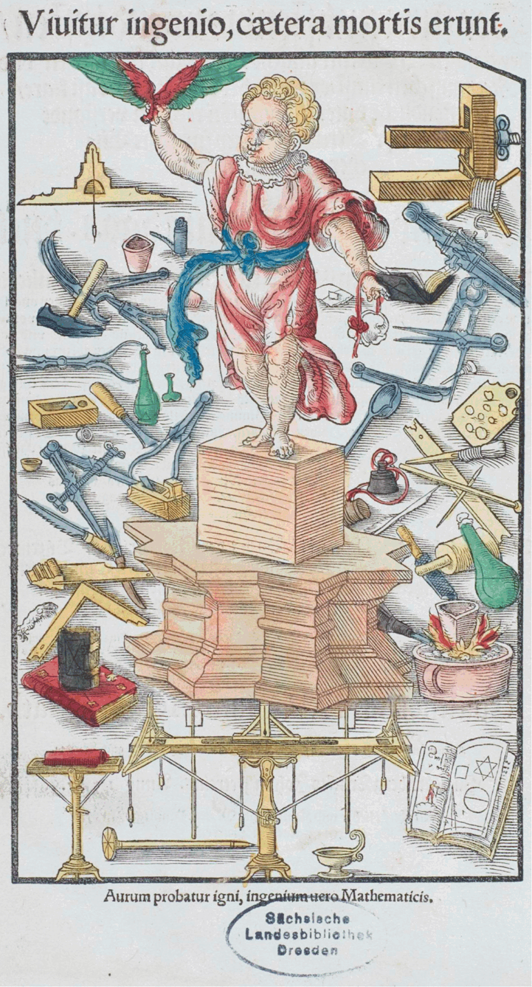

To underscore his concept of the architect as a manager of interdisciplinary knowledge, Ryff sponsored a woodcut attributed to sculptor, goldsmith, and printmaker Peter Flötner (1485–1546), included in both Architectur [Fig. 0.10] and German Vitruvius.57 The print pictures child-like Genius bearing the winged herma and weights of Hermes, god of invention, craftsmen, and natural philosophers. Genius stands among the tools of diverse visual, mechanical, and liberal arts. Measuring devices and a tome with geometric figures conjure architecture’s mathematical foundations, reinforced by the inscriptions “Viuitur ingenio, cætera mortis erunt” (“Genius endures, all else is mortal”) and “Aurum probatur igni, ingenium uero Mathematicis.“ (“Gold is tested by fire, true genius by Mathematics”).58 Craft implements such as the carpenter’s saw, bellows, a hammer, and a painter’s palette meanwhile embody the artisanal practices that require mathematical knowledge. Drafting instruments such as a compass and ruler – sixteenth-century emblems of architecture – additionally figure the confluence of mathematics and technics within architectural practice. Collectively, the elements of Flötner’s allegory position architecture as a type of applied mathematics that marshals and synthesizes visual, mechanical, and liberal arts. Through such images, Ryff’s Vitruvian publications inscribed into the architectural literature of sixteenth-century northern Europe the Vitruvian idea that manifold artistic and scientific practices converge in architecture.59 Ryff thereby gave the North’s long-flourishing interactions between architecture and natural philosophy both theoretical foundations and an ancient pedigree.

0.10 Attributed to Peter Flötner, Architectural Genius, hand-colored woodcut with letterpress in Walther Hermann Ryff’s Der furnembsten, notwendigsten, der gantzen Architectur angehörigen Mathematischen vnd Mechanischen künst […] (Nuremberg: Johann Petreius, 1547), Dresden, SLUB Dresden, Digital Collections, Optica.31, fol. 1v.

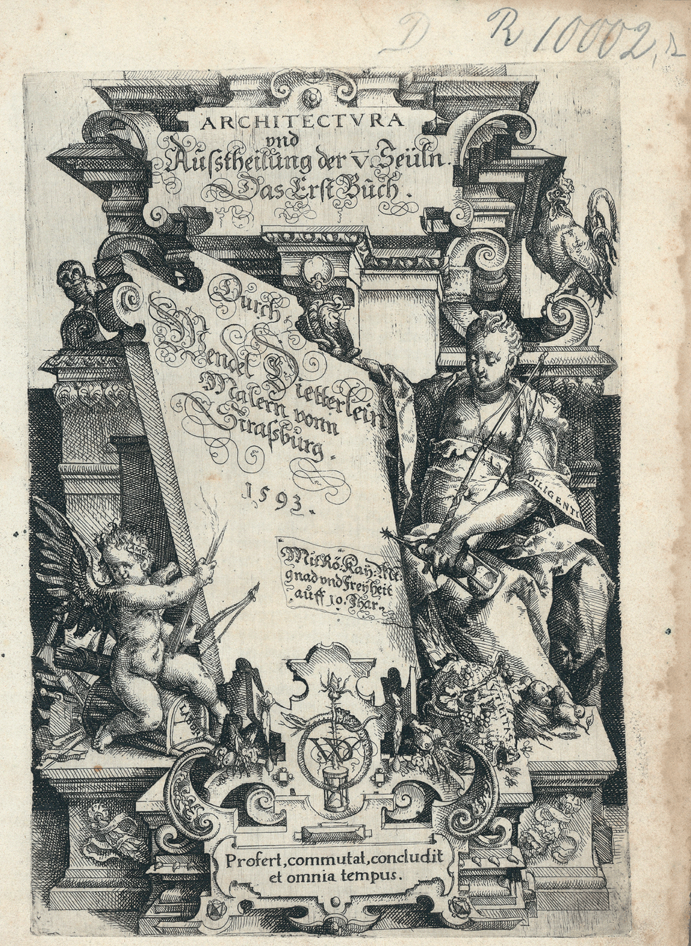

Some fifty years later, Dietterlin deepened northern Europe’s commitment to Vitruvian interdisciplinarity by framing the architectural image as an engine of exchange between architecture, art, and natural philosophy. That Dietterlin saw his Architectura as a contribution to the Vitruvian tradition is evident from the title page of the First Book of 1593, which emulated Ryff’s allegory of architectural interdisciplinarity while introducing some key changes [Fig. 0.11]. Dietterlin’s etching shows child-like Amor astride the basket of Labor, holding flaming arrows poised to ignite Diligence’s beehive of Utility, figuring passion for artisanship as it subdues the sting of artistic toil. Around Labor lie the sculptor’s hammer and chisel, the woodworker’s saw, and the painter’s brush, palette, and mahlstick, indicating the spectrum of figural arts implicated in the architectural practices of Dietterlin’s world. A rooster and an owl, respective animal familiars of Hermes, god of artisans and natural philosophers, and Athena, goddess of techne, likewise figure the links between architecture and natural philosophy.60 The raking perspective of the signature “Durch Wendel Dietterlin Malern vom Straßburg”61 (“by Wendel Dietterlin, Painter from Straßburg”) asserts the author’s mastery of linear perspective, a form of the applied mathematical knowledge Ryff and Flötner had previously posed as a link between architecture, the figural arts, and natural philosophy. Despite its debts to prior Vitruvian literature, Dietterlin’s First Book title page also presented the radical idea that images can embody the interdisciplinary intelligence of architecture. The print departed from the allegory of architectural knowledge prefacing Ryff’s Vitruvian publications as well as the title pages of other recent architectural treatises by picturing artists’ implements such as the paintbrush but not the architect’s compass and ruler.62 In so doing, it asserted that architectural images, including those that convey natural philosophical knowledge, can rival building as the ultimate goals of architectural invention.

0.11 Wendel Dietterlin, Allegory of Architectural Practice, etching with engraved letterpress in Dietterlin’s ARCHITECTVRA vnd Aūsstheilung der V. Seüln. Das Erst Būch. (Stuttgart: s.n. 1593), Strasbourg, Bibliothèque nationale et universitaire de Strasbourg, R.10.002,1, Title Page.

Vitruvius, to be sure, had also esteemed architectural image-making, citing images as lynchpins of communication in architectural practice and referring to illustrations for his De architectura, lost figures Renaissance readers strove to reconstruct.63 Dietterlin placed far greater emphasis on the power of architectural images to form knowledge about architecture and its sister disciplines, particularly as tools for observing and describing nature. Much of the present book will concern how the images of Dietterlin’s Architectura recast the Vitruvian ideal of architectural interdisciplinarity – an ideal that thrives to this day – by empowering readers to synthesize artistic and natural philosophical knowledge in empirically derived architectural images. In this way, Dietterlin channeled the Vitruvian tradition of interdisciplinary architectural knowledge to bolster his era’s growing culture of empirical image-making. His intervention reveals not only the central role image-making played in early modern Vitruvian architectural culture, but also the ways Vitruvian theories of architectural knowledge promoted empirical research in art and natural philosophy during a new age of visual description.

Dietterlin’s Architectura

Dietterlin’s Architectura stands today as an exemplary and pivotal work for the rise of architectural images as drivers of empirical research during the decades around 1600. Nevertheless, the treatise defies many modern notions of architectural expertise and scientific practice. Last analyzed at length in an 1893 biography and a 1940 monograph, Dietterlin’s Architectura has long been regarded as a work of architectural fantasy.64 In the 1872 tome that coined the term “German Renaissance,” Wilhelm Lübke called the Architectura’s explosion of ornament and confabulations of architecture, painting, sculpture, and print “a true witch’s sabbath of the loveliest fruition from the nascent years of the baroque style.”65 With its overwrought and often impossible-to-build inventions, Dietterlin’s Architectura has seemed unlikely to merit a reputation as a rigorous work of architectural theory.

In combination with its florid forms, the Architectura’s occult imagery – nocturnal creatures, alchemical symbolism, and references to hermetic learning – has appeared to eliminate the possibility that the treatise might have contributed to the history of knowledge.66 Architectural historian and critic Manfredo Tafuri (1935–1994) once asserted that the occult dimensions of architectural treatises from sixteenth-century northern Europe, such as Dietterlin’s Architectura, counteract the natural philosophical aspirations those works also display.67 Thus, authors have by and large dismissed the idea that Dietterlin’s Architectura should be taken seriously as a natural philosophical text.68 Nevertheless, as the intersections between architectural etching and alchemy discussed in Chapter 3 demonstrate, occult and natural philosophical interests prove nearly impossible to disentangle within the work of Dietterlin and his contemporaries, all the way up to the Holy Roman Emperor Rudolf II (1552–1612).69 In reassessing the Architectura in light of the history of science, the present book aspires to refine our grasp of the equally messy intersections between early modern architectural and natural philosophical knowledge.

That process begins with understanding the professional experience Dietterlin brought to his Architectura. In his 1675–79 Teutsche Academie (German Academy), painter Joachim von Sandrart (1606–1688) extolled Dietterlin as a “painter and building master” (Mahler und Baumeister).70 It was therefore long assumed that Dietterlin, like most other sixteenth-century painters who authored architectural treatises, had worked as an architect. Up to the early twentieth century, historians even attributed several Rhineland buildings to the artist.71 Still, there is no evidence to substantiate the suggestion that Dietterlin, who signed all his known books and documents a variation of “Wendel Dietterlin, painter and citizen of Straßburg,” ever devised or built a building. Instead, Dietterlin’s formation as a painter of architecture equipped the artist to create architectural images, a professional trajectory typical of his milieu. Before they devised architectural treatises, Dürer, Pieter Coecke van Aelst (1502–1550), and Hans Vredeman de Vries (1527–c. 1606) trained as painters. Dietterlin’s Straßburg contemporary, Daniel Specklin (1536–1589), was educated as a silk embroiderer before he pursued military engineering and published a treatise on fortification, the Architectura, in 1589.72 In addition, while the Architectura’s imagery establishes that Dietterlin devoured natural philosophical literature, there is no proof the artist practiced natural philosophy. The artist canonized the genre of the architectural image as a tool of natural philosophy without any experience as a builder or natural philosopher.

But how could Dietterlin have formed his Architectura as a landmark in the history of intersections between architecture and natural philosophy without any firsthand experience in either discipline? The answers lie in the treatise’s complicated gestation, during which the artist came to use etchings of architectural ornament to evoke natural philosophical concepts and practices. Dietterlin’s Architectura materialized over three installments in 1593, 1594, and a final, summative installment in 1598.73 Each appeared first in German and then in bilingual, Latin-French adaptations, courting vernacular and Latinate audiences in Dietterlin’s own Holy Roman Empire and abroad.74 Unless I am discussing a specific edition, I call the 1593, 1594, and 1598 installments of Dietterlin’s Architectura the “First Book,” the “Second Book,” and the “1598 Architectura” respectively, and refer to the project in its entirety as “the Architectura.”75 The present book is the first to consider not only how the Architectura evolved in stages, but also the ways in which the treatise’s serial development allowed Dietterlin to hone modes of engaging diverse audiences and natural philosophical ideas.

Prior scholars have called Dietterlin’s Architectura many things: a painter’s architecture book,76 a pattern book for architectural sculpture,77 a guide to the design of buildings,78 a compendium of emblematic images,79 and even an architectural novel.80 In fact, Dietterlin’s treatise could serve all the functions ascribed to it, and more. The finished, 1598 Architectura summarizes procedures for drawing before progressing though five chapters or “books” respectively dedicated to the Tuscan, Doric, Ionic, Corinthian, and Composite Orders of architecture. Each book proceeds from a history of its Order to instructions for devising the Order’s parts. Each also concludes with etchings displaying examples of that manner in the form of architectural and nonarchitectural designs: fountains, epitaphs, altarpieces, and even a saltcellar.81 Artists could execute most of the projects in various or multiple materials, from paint, to metal, ceramic, stone, wood, or glass. Across its limited prose and numerous etchings, Dietterlin’s Architectura envisioned the five canonical Orders of architecture as manners of ornament that can be realized in all artistic media.82 The treatise thus applied a leading theory of architecture – the theory of the Orders – to the design practices of other visual arts, while also foregrounding artistic methods of design such as drawing and perspectival composition.83 By portraying architectural expertise as a form of knowledge that could arise from the practice of figural arts alone, the Architectura broke with European traditions in architectural writing. It not only counted as one of the sixteenth century’s most substantial series of architectural images, but as well championed the genre of the architectural image as such.

In addition, Dietterlin’s Architectura etchings visualized and physically embodied syntheses of architecture, painting, sculpture, and other media as no prior architectural treatise had.84 One plate [Fig. 0.12] shows a facade with a skirmish bursting from a plunging cityscape, a print that viewers can interpret as a model for an architectural wall painting, a relief, or some mix of the two. Like many etchings in Dietterlin’s Architectura, the print enacts what we today call “intermediality,” or the interaction of media.85 The wall melding with painting or sculpture figures the physical conjunction of media, as well as the possible indeterminacy of medial identities. Using etching to portray architecture and other media, Dietterlin’s print shows how the qualities of one visual medium can mime those of another. The image’s perspectival effects additionally suggest the compositional qualities common to architecture and other artistic media such as drawing or painting, demonstrating that different media can share formal characteristics or frameworks. Finally, the convergence of an etched painting or sculpture merging with a building, within a treatise on architecture, embodies the principle that the techniques of multiple media can spring from a single source – in this case, architectural ornament.

0.12 Wendel Dietterlin, Façade Design with King Saul, etched illustration in Dietterlin’s ARCHITECTVRA von Außtheilung, Symmetria vnd Proportion der Fünff Seulen […] (Nuremberg: Hubrecht and Balthasar Caymox, 1598), Zurich, Zentralbibliothek Zürich, Rx 12: c,2 | F, pl. 147.

Architectural ornament acts not only as the main subject of Dietterlin’s Architectura, but also the means whereby it visualizes links between architecture, the other visual arts, and natural philosophy. Although the scientific qualities of architectural ornament have gone largely unheeded by historians – who often see images of machines or other engineered structures as more emblematic of architectural images’ relationships to natural philosophy – the subject in fact offered Dietterlin exceptional opportunities for exploring natural philosophical themes. In numerous historical and cultural contexts, ornament has displayed a distinctive capacity to traverse media and institutions.86 For audiences in sixteenth-century northern Europe, ornament also served as a systematic nexus of artistic making, imagination, figuration, and authority.87 Dietterlin and his peers used those qualities in architectural ornament to engage artists, architects, and natural philosophers alike. Images of architectural ornament enjoyed a special status in their efforts. While built architectural ornament could model natural philosophical concepts, images of architectural ornament linked even more seamlessly to the image-based, empirical investigations of natural philosophers.

The architectural ornament etchings that fill Dietterlin’s Architectura connected architecture, art, and natural philosophy by visualizing dynamics of order. For instance, Dietterlin and others used images to describe the Orders as entities with normative measurements and decorations. Natural historians such as Gessner likewise sought to visualize norms for botanical, zoological, and geological species, while anatomists such as Vesalius toiled to picture human physiological norms based on dissections of diverse bodies.88 Renaissance authors of architectural images moreover used ornament to visualize macroscopic order on a smaller scale, just as natural philosophers were beginning to collate individual observations to propose general propositions about nature. For example, Leon Battista Alberti (1404–1472) asserted that architectural ornament should express the structural logic of the edifice it adorns; Andrea Palladio (1508–1580) insisted that architecture should echo physical principles, such as tectonics and mathematical regularity, observed throughout nature.89 By a similar turn, Gessner observed geometric patterns in the structures of certain crystals that evidenced nature’s mathematical order.90 Finally, the empirical processes that sixteenth-century makers of architectural ornament used to visualize norms and order in architecture mirrored the empirical approaches contemporary natural philosophers wielded to describe norms and order in nature.91 For instance, both types of experts collected samples, and measured and drew evidence, and compared visual data. In sum, Dietterlin’s Architectura could advance the natural philosophical potential of architectural images not despite, but because of, its wealth of ornament etchings.

The intermedial conceits and ornamental focus of Dietterlin’s Architectura sensitized its readers to natural philosophical concepts – and the potential of architectural images to visualize those concepts – on various fronts. The Architectura etchings are among the most richly figural images of any sixteenth-century architectural treatise, the better to attract the artist readers Dietterlin courted. One byproduct of the book’s exceptionally figural orientation was that it could vividly visualize natural phenomena that also intrigued natural philosophers, such as the antipathy between certain animal species, the mechanics of pulleys, or the path of water droplets as they ricochet off a hard surface. Dietterlin’s etchings, in other words, showcased architectural images’ capacity to further the descriptive imperatives of natural philosophy. Moreover, Dietterlin formed his Architectura through modes of visual research that traversed art and natural philosophy, such as copying, annotation, and bricolage, and left traces of his processes in the prints for viewers to ponder. The Architectura etchings thereby demonstrated that architectural images could share, and even contribute to, the investigative practices of natural philosophy.

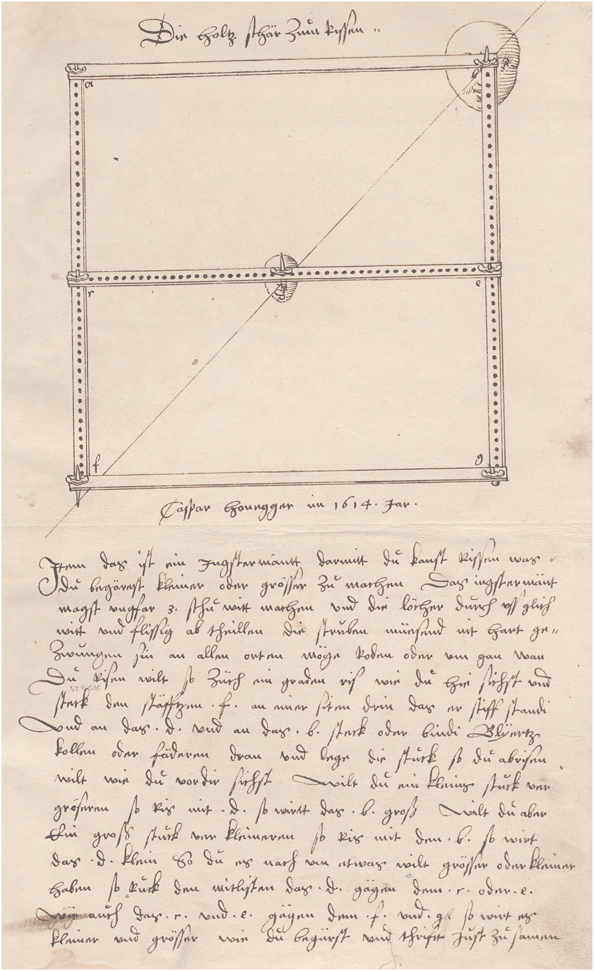

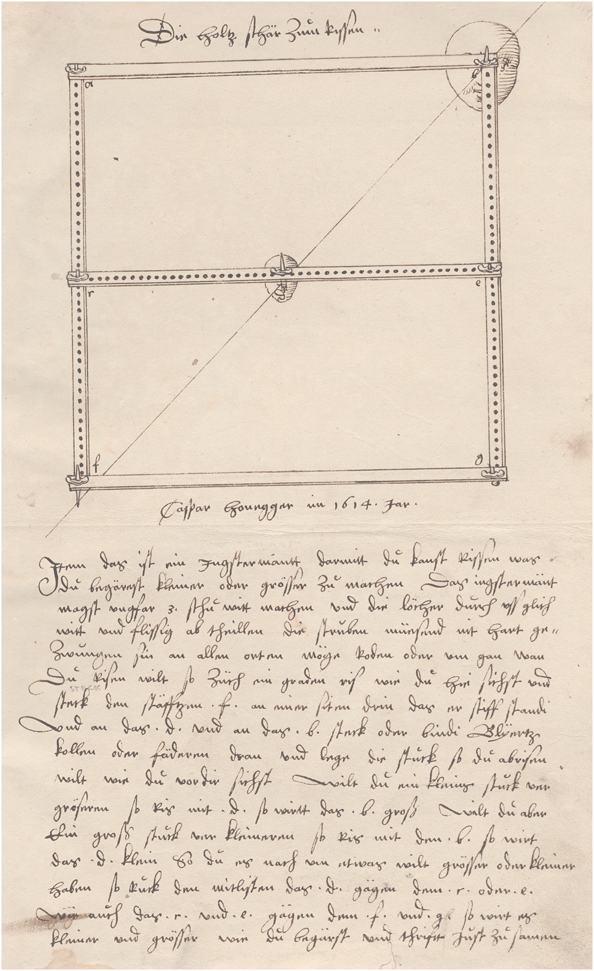

Indeed, the content, materials, structures, and formation of Dietterlin’s Architectura not only embodied dialogue between architecture, the figural arts, and natural philosophy, but also activated such commerce92 by instigating what Anthony Grafton and Lisa Jardine have called “reading for action.”93 For instance, inscriptions attest that a volume containing a copy of Dietterlin’s Architectura passed from a sculptor, to a woodworker, and finally a façade painter between 1611 and 1622 alone, and at least one owner visually elaborated on its lessons.94 A drawing and accompanying text signed “Caspar Fonnggar in 1614” at the endpaper show mathematical exercises for enlarging and diminishing any representation of an object drawn by an Architectura reader [Fig. 0.13]. The diagram is useful for modifying designs in any artistic medium or for representing structures in perspective. Though Dietterlin’s Architectura had pictured scalar modulations and perspectival compositions such as the one that opened the present Introduction [see Fig. 0.1], the text had not explained any method for formulating them. The draftsperson appears to have used Dietterlin’s scalar and perspectival images as prompts for further study of perspectival representation, an art that fascinated artists, architects, and natural philosophers. Here and in scores of other copies of Dietterlin’s Architectura, one discerns how the descriptive properties of architectural images invited exchanges between artists, architects, and natural philosophers.

0.13 Anonymous draftsperson, Exercise in scaling, after 1598, pen and black-brown ink on laid paper, in Dietterlin’s ARCHITECTVRA von Außtheilung, Symmetria vnd Proportion der Fünff Seulen […] (Nuremberg: Hubrecht and Balthasar Caymox, 1598), Zurich, Zentralbibliothek Zürich, Rx 12: c,2 | F, Endpaper.

Considering the evidence that early modern architectural images and the etchings of Dietterlin’s Architectura instigated such intermedial and interdisciplinary exchanges, the long-misunderstood treatise merits reassessment. Indeed, the conventional perception of Dietterlin’s Architectura as a work of pure architectural fantasy rests on the false premise that images that do not present the state of the world as we know it – for instance, the norms of architectural tectonics – cannot convey scientific knowledge. Many early modern images engage natural philosophical ideas even while also portraying unnatural or supernatural content, for instance van Eyck’s masterful depiction of light interacting with various architectural surfaces alongside a monumental apparition of the Virgin. Moreover, during Dietterlin’s era, learned texts on art, architecture, and natural philosophy often obscured their core knowledge when their authors sought to preserve certain trade secrets from interlopers.95 In formulating a treatise that reveals the transposition of visual research practices across arts and sciences only through sustained, informed looking, the Architectura joined a robust tradition of artisanal and natural philosophical literature that obfuscates in order to instruct.96 In sum, Tafuri was correct to observe that the Architectura’s ornamental profusions signal the dangers of pure rationalism. What Tafuri did not discern was that Dietterlin’s often arcane treatise rejects rationality to foreground the intersecting empirical practices of artists, architects, and natural philosophers around 1600.

In the wake of Dietterlin’s Architectura, painters, goldsmiths, and woodworkers from Straßburg to Frankfurt, Cologne, and Prague composed books that emulated Dietterlin’s formulae for placing architectural images in conversation with other arts and sciences and for using architectural images as sites of natural philosophical inquiry.97 Between Dietterlin’s death in 1599 and 1700, the Architectura also entered four reprints, and its prints were copied in other treatises multiple times.98 Its images disseminated from Straßburg to Santiago de Compostela and from Lemgo to Lima and eventually reincarnated in three modern editions.99 With the images of the Architectura circulated Dietterlin’s vision of the intersections between architectural images and natural philosophy. When Dietterlin and his peers used images of architectural ornament to embody empirical ways of knowing nature’s forms and structures, they not only manifested the Vitruvian dictum that “The architect’s expertise [scientia] is enhanced [ornata, literally, “ornamented”] by many disciplines and various sorts of specialized knowledge.”100 They also presaged the operative role architectural images would play in the emergence of the new sciences of experimentation in the seventeenth century. The task of the present book is to reveal, through Dietterlin’s Architectura, how architectural images became trading zones between architecture and natural philosophy.

The Science of the Architectural Image

The story of the architectural image and its natural philosophical connections has remained untold until now in large part because it implicates fields of study rarely assembled in unified narratives. The Architectural Image and Early Modern Science synthesizes and builds upon three dynamic yet previously distinct traditions of scholarship concerning early modern visual culture and the renaissance of classical learning: studies of art–science interactions, research on the interplay of art and architecture, and investigations of the links between architecture and science.

The rapport between early modern art and science has attracted interest for over half a century.101 Over the past two decades, scholars such as Horst Bredekamp, Birgit Schneider, Vera Dünkel, Susan Dackerman, Lorraine Daston, David Freedberg, and Martin Kemp have built on the research of Erwin Panofsky and other historians of art to highlight how all manner of early modern images formed scientific knowledge.102 Drawing on pioneering art and intellectual histories by Michael Baxandall and Svetlana Alpers, such researchers as Pamela O. Long, Alexander Marr, and Pamela H. Smith have also posed the making of images as a scientific activity, exploring how artists – who gathered botanical specimens, mixed chemicals, and built machines – catalyzed empirical tactics of image-making in natural philosophy.103 Their publications have shown that artisanal practices were crucial to the rise of the new sciences, in which classical understandings of nature expanded to accommodate firsthand experimentation and observation. Since such research has highlighted the crucial role of art in propelling scientific developments, it has also nurtured a more active exchange of ideas between early modern art historians and early modern historians of science than ever before.

Scholarship on the links between early modern architecture and the other visual arts has likewise flowered over the past two decades, as authors such as Cammy Brothers, Michael Cole, and Alina A. Payne have scrutinized architectural drawings, architectural sculpture, and architectural prints.104 Their work has highlighted how the Renaissance revival of Vitruvius’s De architectura encouraged such intermediality by framing architecture as an art in which all other visual ats converge.105 As a result, early modern architectural history has grown from a field largely concerned with the history of buildings and architectural theory to a discipline that also engages art history and visual culture studies. In addition, early modern art historians have increasingly adopted the methods and literature of architectural history.

The third tradition – studies of the intersections between early modern architecture and science – has arisen most recently and is gathering momentum. Scholars such as Paolo Rossi, Anthony Gerbino, Pamela O. Long, Hermann Schlimme, and Matthew Walker have assessed engineering and infrastructure, the revival of classical scientific texts in early modern architecture, the roles of architects in forming scientific societies, and the architecture of scientifically oriented spaces such as astronomical observatories or anatomy theatres.106 As in art–architecture studies, the Vitruvian tradition has become a focal point for such scholars, for De architectura and its early modern emulators saw architecture as a medium that relied on natural philosophical knowledge.107 Recent research on early modern architecture–science interactions has granted architecture a more prominent role in art-science studies, and has begun to convince historians of science that architectural culture was, like art, vital to the rise of the new science.

Despite thriving early modern art–science, art–architecture, and architecture–science scholarship, the ways in which early modern architects and makers of architectural images adopted and shaped artistic and scientific practices of visual research remain obscure. The Architectural Image and Early Modern Science provides crucial insight into the rise of architectural images as vectors of natural philosophy. Integrating the three scholarly traditions, it treats the formation of images, texts, and buildings as overlapping modes of research whose fusion in the work of Dietterlin and his peers recast Vitruvian interdisciplinarity for modernity. The present book thus pioneers a method for examining the visual culture of early modern architecture as a nexus of art and science.

To recount how the early modern architectural image became a platform of natural philosophy, the present book traces the biography of Dietterlin’s Architectura from inception to formation to reception. Against the backdrop of the Vitruvian revival sketched here, Chapter 1 examines the subsequent advent of architectural images – what I call the “figural turn” – in the architectural culture of Dietterlin’s world. I analyze archival and visual records from four kinds of artistic institutions: artist guilds, publishers, masons’ lodges, and courts. I argue that between 1450 and 1550, each institution confronted disruptions such as the rise of print, the Reformation, and indeed Vitruvianism. These challenges encouraged artists to create architectural images, infiltrate architectural professions, and introduce artistic and scientific practices of visual research to architectural design. As evidence, I consider the vegetal structures of Matthias Grünewald’s (c. 1470–c. 1530) Isenheim Altarpiece, the façade paintings of Dietterlin and Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/8–1543), and Architectura printer Bernhard Jobin’s collaborations with builder Daniel Specklin to document architecture in print scientifically. I additionally evaluate the empirically derived, botanical forms of Dietterlin’s paintings for the Hall of the Straßburg Masons and Stonecutters and the microcosmic interior Dietterlin devised at Stuttgart for Ludwig III, Duke of Württemberg (1554–1593) – both of which informed the empirical practices of architectural image-making that Dietterlin’s Architectura later promoted. In sum, I show how Renaissance artists and natural philosophers introduced empirical methods of visual research to the North’s emergent culture of architectural images.

Chapter 2 probes how Dietterlin and his artist contemporaries introduced measuring practices to architectural treatises like the Architectura to support the empirical image-making ambitions of architecture scrutinized in the preceding chapter. I argue that images in Renaissance architectural treatises hosted pivotal conflicts between rational and empirical traditions of mathematics and measurement, and that the mixed arithmetic and geometrical design procedures Dietterlin debuted in his Architectura landed a decisive blow for empiricism. My primary evidence includes the geometrical illustrations in masonic incunables, Dürer’s architectural theories, the archaeological renderings of architect Sebastiano Serlio (1475–c. 1544) and woodworker Hans Blum (1520/7–after 1551), and the mathematical etchings of Dietterlin’s Architectura. By comparing mathematical prints in architectural treatises throughout the long sixteenth century, I show how Dietterlin and other makers of architectural images came to shun received, a priori knowledge in favor of the empirical ways of knowing that contemporary artists and natural philosophers also cultivated.

While Chapter 2 revealed the ways in which the mathematics of architectural image-making became empirical, my third chapter examines Dietterlin’s Architectura drawings to show how firsthand research in art, architecture, and science further coalesced in the draftsmen’s art. I compare the 164 known Architectura drawings – among the largest surviving bodies of sixteenth-century architectural treatise drawings north of the Alps – with drawings from the workshops of Donato Bramante (1444–1514) and Raphael (1483–1520) at St. Peter’s, as well as botanical and geological drawings in the collections of physician Felix Platter (1536–1614) and natural historians Conrad Gessner and Ulisse Aldrovandi (1522–1605). I show that Dietterlin’s Architectura drawings and period architectural and scientific drawings display consistent tactics of cutting, bricolage, annotation, folding, and counterproofing. As a result, I establish that drawing-based methods of collecting and managing visual information came to traverse sixteenth-century natural philosophers’ studies, publishing houses, and artist-architects’ workshops. I thereby reveal the ways in which late Renaissance artists, architects, printers, and natural philosophers began to exchange and co-develop parallel, empirical methods for forming knowledge.

Whereas the preceding chapter showed how the visual research tactics of drawing began to link art, architecture, and science, Chapter 4 assesses the ways in which architectural prints subsequently came to sustain scientific inquiry. Specifically, I examine architectural etchings in Dietterlin’s Architectura and peer printing enterprises as key sites for sixteenth-century Central Europe’s robust culture of alchemy. The chapter connects formal and iconographical readings of architectural etchings by Dietterlin, Wenzel Jamnitzer (1507/1508–1585), and Hans Vredeman de Vries with texts by alchemist-empiricists Cornelius Agrippa of Nettesheim (1486–1535) and Paracelsus (1493/1494–1541). The comparisons reveal that architectural image-makers used the mercurial forms of etching both to visualize and enact alchemical principles while embodying the protean materiality of architectural ornament. I argue that Dietterlin’s Architectura etchings channeled the long-standing frisson between alchemy and etching to bring principles and methods of chemical research such as transmutation to practices of architectural image-making. Through alchemical imagery inspired by Dietterlin’s Architectura at the court of Rudolf II in Prague, I establish that architectural images ultimately became tools of alchemical thinking. The transformative materials and structures of architectural etching allowed architectural images to become, by 1600, arenas for natural philosophical research.

Having established in Chapter 4 how architectural images became vehicles of natural philosophy, I use Chapter 5 to show the ways in which that trend began to erode key conventions of built architecture.108 I assert that Dietterlin’s Architectura subverted the principles of architectural naturalism influentially developed in Alberti’s De re aedificatoria (On the Art of Building) by promulgating a range of mercurial architectural forms that recall the internal materials and structures of the human body, and which fuse built substructure with ornamental superstructure.109 Dietterlin derived these anatomical forms from empirical anatomy treatises such as Vesalius’s De humani corporis fabrica (On the Fabric of the Human Body) of 1543, and anatomical flap prints by artists like Heinrich Vogtherr the Elder (1490–1556) and Jost de Negker (c. 1485–1544).110 As architects adopted the Architectura’s anatomical ornaments, they defied Albertian tectonic norms as well as the conventional relationships between architectural interior and exterior. In assessing how Dietterlin’s Architectura dissected architecture’s physical and theoretical corpus, Chapter 5 demonstrates that the rise of architectural images as fora for the study of nature exposed the very limits of naturalism in built architecture.

Building on the preceding account of Dietterlin’s contributions to European architectural and natural philosophical discourses, Chapter 6 probes the Architectura’s natural philosophical fortunes among architectural sculptors in seventeenth-century Peru. The chapter revolves around the carved façades of the Cathedral of Cuzco, Cuzco’s Jesuit Compañía, and the monastic church of San Francisco in Lima, which emulated imagery from Dietterlin’s Architectura while also comparing European and Inca ideas about the relative stability of matter and forms. I explore how the indigene sculptors who rebuilt each façade following cataclysmic earthquakes in the 1650s adapted the structural, material, and anatomical conceits of Dietterlin’s Architectura to overturn the treatise’s picture of architecture as a medium of protean materiality. I reveal that Indigenous Peruvian sculptors used Dietterlin’s architectural images to articulate an alternative ontology, in which forms and structures prove as transient as earthquakes, but matter remains as enduring as stone. By the end of the seventeenth century, architectural images like Dietterlin’s linked natural philosophical discourses across vast geographical and cultural distances.

The Conclusion surveys the substantial legacy of Dietterlin’s Architectura and his culture of architectural images in the interface between architecture and science today and considers why the scientific qualities of architectural images of Dietterlin’s era no longer appear obvious to present-day viewers. I attribute the dramatic changes to the content, rhetoric, accessibility, and scientific purposes of architectural images to the demise of learned empiricism, which framed knowledge derived from firsthand investigation through the received knowledge of learned texts. I position Dietterlin’s Architectura as both an apex and a swan song of learned empiricism in architectural image-making by examining the fate of the genre in seventeenth-century England and France. While both milieus long cherished the traditions of learned empiricism in architectural image-making, each ultimately saw architectural image-makers shed learned empiricism in favor of object evidence alone. I argue that the decline of nonempirical sources for scientific understanding was already anticipated in the architectural images of Dürer, from which Dietterlin drew to form the final etching of his Architectura as a eulogy for that vanishing paradigm. Dietterlin saw his Architectura as a summation of learned empiricism in architectural image-making, one instrumental to generating a purer form of empiricism for architectural and natural philosophical research for the looming seventeenth century.

The story of artists and the natural philosophy of architecture in Dietterlin’s world matters today because it sheds light on a decisive episode in intellectual and cultural history, when links between practical experience and learned knowledge began to multiply, converge, and cross disciplinary boundaries as never before. Dietterlin’s Architectura established the essentially transitive nature of practices of observation and description between the arts and sciences, and consolidated those methods in Renaissance architecture. The conjunction of art and architecture in Dietterlin’s world not only bolstered the rise of empiricism, but also predicated the modern nexus of artistic and scientific inquiry in architecture and other disciplines. Indeed, the efforts of Dietterlin and his peers to consolidate, through architecture, the universal authority of sensory experience as a source of knowledge lend this story salience today. If, during the sixteenth century, concepts such as the veridical authority of eyewitness and the reliability of images as conduits of knowledge were only just gaining traction in epistemological discourse, in the twenty-first century, the slippery yet crucial roles of experience and images in the formation of knowledge have again come to the fore. The story of Dietterlin’s Architectura exposes the formative role of the architectural image in our own contemporary controversies over visual experience and expertise. What follows, then, is the story of how the architectural image became an enduring epistemological enterprise.