1.1 The Origins of the Transnational Legal Process for Redd+

In the first half of the 2000s, numerous developing countries, NGOs, and scientists pressed for the elaboration of mechanisms within the UNFCCC to tackle carbon emissions from forestry-related sources in developing countries.Footnote 162 While atmospheric and climate scientists had long recognized the importance of reducing these sources of carbon emissions in developing countries,Footnote 163 they had only been addressed in a limited manner due to political concerns that climate mitigation action should focus on industrialized sources of carbon emissions.Footnote 164 In particular, the rules adopted for the clean development mechanism (CDM) under the Kyoto ProtocolFootnote 165 specifically excluded from its purview projects aiming to reduce carbon emissions through the avoidance of deforestation.Footnote 166 Nonetheless, the first generation of forest carbon projects pursued through the CDM and private carbon markets laid the technical groundwork and built momentum for future efforts aimed at addressing carbon emissions in developing country forests in global climate governance.Footnote 167

In December 2005, the governments of Costa Rica and Papua New Guinea, on behalf of the Coalition of Rainforest Nations, proposed that the UNFCCC COP consider developing new mechanisms to reduce emissions from deforestation (RED) in developing countries.Footnote 168 As part of the Bali Action Plan adopted in December 2007, the UNFCCC COP launched international negotiations for the development of “policy approaches and positive incentives on issues related to reducing emissions from deforestation and forest degradation in developing countries; and the role of conservation, sustainable management of forests and enhancement of forest carbon stocks in developing countries.”Footnote 169 In a separate decision focusing specifically on “approaches to stimulate action” on REDD+,Footnote 170 the UNFCCC COP affirmed the “urgent need to take meaningful action” to reduce GHG emissions from forest-based sources in developing countries and recognized that doing so could “promote co-benefits” and “complement the aims and objectives of other relevant international conventions and agreements.”Footnote 171

The concept of REDD+ elicited strong support among a wide coalition of public and private actors from both the North and the South who were variously concerned with climate change, forest governance, and sustainable development.Footnote 172 At the time, REDD+ was supported as a win-win-win solution that could not only reduce an estimated 17 percent of global carbon emissions worldwide,Footnote 173 but could also protect forests and their critical ecosystems and help alleviate poverty among forest-dependent and rural communities.Footnote 174 Within the UNFCCC, negotiations on REDD+ progressed at a remarkable pace, especially when compared with the broader set of international negotiations on climate change.Footnote 175 In December 2010, the UNFCCC COP adopted the Cancun Agreements, in which it defined the scope of jurisdictional REDD+ activities and established the stages and requirements for their implementation in developing countries.Footnote 176 The UNFCCC COP has since adopted a series of decisions further clarifying the rules for the pursuit of jurisdictional REDD+ in developing countries,Footnote 177 culminating in the integration of jurisdictional REDD+ in the Paris Agreement adopted in December 2015.Footnote 178 These rules are summarized in Table 1.1.

Table 1.1 The elements of jurisdictional REDD+ under the UNFCCCFootnote 180

In the Bali Action Plan as well as the Cancun Agreements, the UNFCCC COP encouraged developing countries to take voluntary measures to prepare for domestic operationalization of jurisdictional REDD+ and called on developed countries, international organizations, and NGOs to provide finance, capacity-building, and technical assistance to support them in their efforts.Footnote 179 In response, an array of developing and developed country governments, international organizations, multilateral development banks, conservation and development NGOs, and corporations have supported the development and implementation of REDD+ activities around the world. They have most notably established knowledge-sharing, capacity-building, and technical assistance programs, mobilized finance, carried out research and analysis, developed rules and guidance, created certification programs, standards, and methodologies, and organized countless policy meetings, networks, and dialogues.

Although these initiatives differ in many respects, they each adhere to the three basic ideas that have come to define the wide range of REDD+ programs, policies, and projects around the world. First, REDD+ initiatives aim to increase carbon sequestration in developing country forests by funding activities that either reduce “negative changes” or enhance “positive changes” in forest carbon stocks.Footnote 181 Second, they are intended to finance activities on the basis of results achieved in reducing or avoiding carbon emissions or increasing carbon stocks that are measured, reported, and verified (MRV) on the basis of a pre-existing baseline or reference level.Footnote 182 Third, they are meant to take into account other important social or environmental objectives and considerations beyond carbon sequestration by requiring that activities comply with a set of social and environmental safeguards or that they deliver co-benefits such as the reduction of poverty or the preservation of biodiversity.Footnote 183

Beyond these three core ideas, there is significant diversity in the ways in which legal norms for REDD+ have been developed and applied by public and private actors around the world.Footnote 184 The most important area of divergence in the transnational legal process for REDD+ relates to the difference between jurisdictional and project-based activities. Jurisdictional REDD+ refers to programs implemented by developing countries that seek to reduce carbon emissions from forest-based sources at a national scale in line with the requirements set by the UNFCCC COP. In contrast, project-based REDD+ generally consists of activities implemented by corporations, NGOs, and communities to reduce forest carbon emissions at the local level. These activities must follow the methodologies and meet the standards established by nongovernmental certification programs in order to generate credits that can be sold and traded on carbon markets.Footnote 185 Some REDD+ projects have been implemented by governments or their partners to experiment with new tools and methodologies as part of their jurisdictional readiness efforts at the national or subnational level. Most REDD+ projects have been carried out by NGOs, corporations, or communities, with the aim of sequestering carbon as well as possibly delivering other social and environmental benefits, in order to generate carbon credits that can be sold or traded on voluntary carbon markets.Footnote 186 While the pursuit of project-based REDD+ activities can be affected by as well as feed into jurisdictional REDD+ programs implemented at the national level, these two forms of REDD+ are fundamentally different and are ultimately governed by different sites of law.

1.2 Levels, Sites, and Forms of Law in the Transnational Legal Process for Redd+

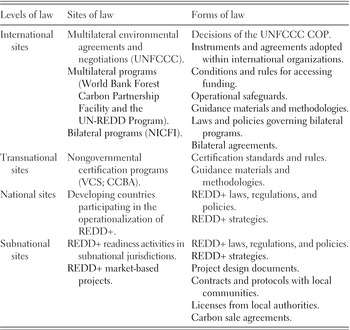

While the UNFCCC has played an important role in the construction of an initial set of legal norms for REDD+, the proliferation of multilateral, bilateral, and nongovernmental initiatives has meant that the transnational legal process for REDD+ has become increasingly plural over time.Footnote 187 As is summarized in Table 1.2, a heterogeneous array of public and private actors has engaged in the construction and conveyance of legal norms for REDD+ within and across multiple sites and forms of law that encompass as well as transcend the decision-making of the UNFCCC.Footnote 188 The transnational legal process for REDD+ has become all the more multi-layered because it has evolved at the intersections of two broader domains that also exhibit significant poly-centricity, one being climate change,Footnote 189 the other forestry.Footnote 190

Table 1.2 Levels, sites, and forms of law in the transnational legal process for REDD+

At the international level, two of the most influential multilateral initiatives established for REDD+ have been the World Bank Forest Carbon Partnership Facility (FCPF) and the UN-REDD Programme. Launched at the 13th session of the UNCCC in December 2007 and operational since June 2008, the FCPF is comprised of two funds for which the World Bank serves as trustee and provides a secretariat: a Readiness Fund that supports developing country capacity-building and preparedness for REDD+ activities and a Carbon Fund that tests eventual performance-based payments for emissions reductions generated through REDD+ activities.Footnote 191 In addition, the FCPF aims to disseminate the tools and knowledge developed as a result of its support for REDD+ readiness and emissions reductions.Footnote 192 The UN-REDD Programme is a collaborative initiative jointly established in June 2008 by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), and the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO).Footnote 193 It provides direct support and technical assistance to developing countries carrying out national REDD+ readiness efforts and seeks to generate and disseminate knowledge, methodologies, tools, and approaches for the development of REDD+ at a global level.Footnote 194 These initiatives have generated legal norms for REDD+ that have taken on various forms, most notably including the agreements that led to their creation,Footnote 195 the rules and conditions they set for accessing funding for REDD+ activities,Footnote 196 the operational safeguards that exist for the delivery of activities they finance,Footnote 197 and the guidance documents they have developed for the implementation of REDD+ activities.Footnote 198

A number of developed country governments have also established bilateral programs to support the implementation of REDD+ around the world. The most important among these is the Norwegian International Climate and Forest Initiative (NICFI) launched in 2007.Footnote 199 As part of the NICFI, Norway has pledged 1.6 billion US dollars in funding to support the global advance of REDD+ through contributions to established multilateral programs and funds as well as direct partnerships with seven developing countries: Brazil, Guyana, Ethiopia, Indonesia, Mexico, Tanzania, and Vietnam.Footnote 200 Through a combination of diplomacy, development aid, research, and technical assistance, the NICFI “seeks to influence the policy process by adding momentum to finalising an international REDD+ agreement, contributing to the detail of the emerging mechanisms and establishing real examples through national-level agreements with key REDD-relevant countries.”Footnote 201 The legal norms for REDD+ have taken on two main forms in bilateral initiatives: the law, policy, or regulation that governs a bilateral REDD+ programFootnote 202 and the bilateral agreements between the government or agency of a developed country and its developing country partner that provide the terms and conditions for the delivery of REDD+ finance and assistance.Footnote 203

At the transnational level, the most significant sites of law for REDD+ are the nongovernmental programs and initiatives that NGOs and corporations have established to guide and support the jurisdictional REDD+ efforts of developing countries and those that aim to sustain and govern the voluntary market for project-based REDD+ activities. To begin with, several large international conservation NGOs,Footnote 204 major management and consulting firms working on the low-carbon economy,Footnote 205 and specialized firms active in carbon finance and tradingFootnote 206 have created their own programs of research, capacity-building, training, technical assistance, and finance for REDD+ activities at multiple levels. These NGOs and corporations have most notably established voluntary initiatives to guide the REDD+ readiness activities carried out by developing country governments. One of the most influential initiatives of this type is the Jurisdictional and Nested REDD+ (JNR) Framework established by the Verified Carbon Standard (VCS) in December 2010 to provide accounting methodologies and rules for the certification of national and subnational REDD+ activities undertaken by governments.Footnote 207 Another important transnational initiative is the REDD+ Social and Environmental Safeguards (REDD+ SES), a multi-stakeholder process launched in May 2009 to develop a set of voluntary social and environmental safeguards for government-led jurisdictional REDD+ programs and activities.Footnote 208

In addition, NGOs and corporations have also supported the formation of a voluntary market for carbon credits generated through REDD+ projects aiming to reduce emissions from forestry-related sources at the subnational level. NGOs and corporations have carried out, brokered, and audited REDD+ activities in line with established methodologies and accounting standards for their development, validation, and certification. The two sets of standards with the greatest share of REDD+ projects worldwide are:Footnote 209 the Agriculture, Forestry & Land Use (AFOLU) Requirements of the Verified Carbon Standard (VCS)Footnote 210 and the Climate, Community & Biodiversity (CCB) Standards.Footnote 211 Both the VCS and the CCB Standards serve as sites of law for the pursuit of project-based REDD+ activities: they set the rules for carrying out, monitoring, and evaluating projects, provide guidance and methodologies for the application of these rules, create a process for the accreditation of third-party auditors for the validation and verification of such projects, and establish procedures for addressing disputes and improprieties in the application of the standards.Footnote 212

At the national level, legal norms for REDD+ have been constructed in and conveyed through the pursuit of jurisdictional REDD+ readiness activities. Over 60 governments throughout the developing world have initiated national multi-year readiness programs to lay the groundwork for the domestic operationalization of jurisdictional REDD+ in accordance with the UNFCCC COP’s guidance and with the support and technical assistance provided by bilateral, multilateral, and nongovernmental partners.Footnote 213 These REDD+ readiness programs involve some combination of strategic planning, policy analysis and development, legal and institutional reform, public consultation and stakeholder engagement, capacity-building and training, and demonstration projects that aim to ensure that a developing country has achieved the conditions required for REDD+ to be implemented on a jurisdictional scale.Footnote 214

There are two main ways in which the pursuit of jurisdictional REDD+ readiness programs may entail the construction and conveyance of legal norms. First, the adoption of a national strategy for jurisdictional REDD+ provides an opportunity for a developing country government to design a tailored framework for the governance of REDD+.Footnote 215 In order to prepare developing countries for the operationalization of REDD+, a national strategy should deal with matters such as the modalities through which international payments for REDD+ will be managed and channeled in a country;Footnote 216 the arrangements for sharing benefits from these payments with stakeholders at multiple levels;Footnote 217 the clarification of land and forest rights and tenure in areas that are targeted for REDD+ policies and measures;Footnote 218 and the participation and engagement of multiple stakeholders.Footnote 219 In turn, the development and implementation of national REDD+ strategies entails the interpretation and application of existing laws and regulations in relevant areas (especially forestry, climate change, land-use, property, and human rights).Footnote 220

Second, jurisdictional REDD+ readiness efforts may also lead to the development and adoption of new laws and regulations. Some of these new laws and regulations have specifically focused on the regulation of REDD+ activities,Footnote 221 including project-based ones.Footnote 222 Other legal, policy, and regulatory reforms have been developed with the aim of achieving actual reductions in carbon emissions from the forestry and land-use sectors.Footnote 223 For instance, developing countries have imposed a moratorium on the exploitation of forestsFootnote 224 or adopted reforms aimed at strengthening forest governance through improved land-use planning, land titling, and enforcement measures.Footnote 225

At the subnational level, legal norms for REDD+ have been constructed in and conveyed through two types of activities. First, the governments of a number of sub-national jurisdictions, most notably including provincial governments in Brazil, Indonesia, and Mexico, have initiated their own jurisdictional readiness programs.Footnote 226 The design and aims of these subnational jurisdictional readiness programs are very similar to the national ones discussed above and are meant to form part of a nested approach to REDD+, in which readiness and early demonstration activities may be initiated at the subnational level in lead-up to the establishment of a national REDD+ framework and the pursuit of a related set of jurisdictional interventions at the national level.Footnote 227 Legal norms for REDD+ have thus been formally enacted through the adoption of laws, policies, and regulations in these subnational jurisdictions.Footnote 228

Second, a multiplicity of public and private actors (including international organizations, national, subnational, and local governments, international and local NGOs and corporations, and local communities) has initiated REDD+ projects that aim to reduce carbon emissions at the subnational level. Close to 350 such projects have been developed in more than 50 developing countries across Africa, Asia, and Latin America and the Caribbean.Footnote 229 In 2014, these projects accounted for the largest share of carbon market activity and had a total market value of 94 million US dollars.Footnote 230 These market-based projects and transactions generate multiple forms of law, including the project design document that must be submitted to the certification program and validated and verified by third-party auditors; the contracts, protocols, or agreements that must be signed with local communities or other affected stakeholders, the licenses and regulatory approvals that must be obtained from local authorities; and the agreement enabling the sale or trading of carbon credits generated by the project.Footnote 231

1.3 The Complexity of the Transnational Legal Process for Redd+

From its origins as a promising and relatively straightforward UNFCCC mechanism with “triple-win” potential for forests, climate change, and sustainable development, the transnational legal process for REDD+ has evolved to become increasingly complex over time.Footnote 232 As various actors have moved forward with the operationalization of REDD+, the challenges, risks, and trade-offs that had been obscured or ignored at an earlier stage in the emergence of REDD+ have begun to resurface.Footnote 233 In particular, the transnational legal process for REDD+ has become intertwined with the conflicting coalitions and agendas that shape the domain of forest governance within developing countriesFootnote 234 and “entangled in fundamental debates about justice and equity from local to global levels.”Footnote 235 To be sure, the involvement of a diverse array of private and civil society actors has also accentuated disagreements about the fundamental purposes and principles of REDD+ within the UNFCCC.Footnote 236 This has most notably included civil society actors who are skeptical about its potential benefits for climate mitigation and concerned about its implications for other important social and environmental considerations.Footnote 237 Indeed, the research, advocacy, and conservation NGOs that have pressed for the recognition of the rights of Indigenous Peoples and local communities in international law and policy over the last 40 years have brought their energies and efforts to the transnational legal process for REDD+, which has provided a new and significant venue for advancing their agenda.Footnote 238 As this book reveals, debates over whether and how to protect the rights of Indigenous Peoples and local communities in the context of REDD+ activities are a cause as well as a reflection of the growing complexity of the transnational legal process for REDD+.

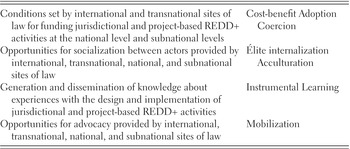

In addition, as REDD+ has spread across multiple sites of law, the transnational legal process for REDD+ has also been characterized by multidirectionality. From 2007 onward, the construction of legal norms for REDD+ within the UNFCCC contended with, and was influenced by, the legal norms for REDD+ constructed in multiple sites of law.Footnote 239 As is often the case with a transnational legal process, the conveyance of legal norms for REDD+ from one site of law to another has given rise to the construction of hybrid legal norms and has created opportunities for their further conveyance across other sites of law. In what follows, I identify four potential pathways and related causal mechanisms through which actors may trigger the conveyance of legal norms to, from, and across sites of law at the international, transnational, national, and local levels (Table 1.3).

Table 1.3 Potential pathways and related causal mechanisms for the conveyance of legal norms in the transnational legal process for REDD+

A first pathway relates to the conditions that international and transnational sites of law have set for accessing sources of finance for jurisdictional and project-based REDD+ activities and the ways in which these conditions may create incentives for implementing a particular set of legal norms at the national and subnational levels. In order to trigger the conveyance of legal norms, the conditions set by these sites of law would need to provide material or reputational incentives for compliance by actors in another site of law (cost-benefit adoption) as well as opportunities for exogenous actors to detect and sanction instances of noncompliance (coercion). By way of example, the FCPF, the UN-REDD Programme, and NICFI have made the delivery of the funding they provide to developing countries for their jurisdictional REDD+ readiness efforts contingent on respect for social and environmental safeguards and other standards.Footnote 240 The domestic influence of these conditions in the context of REDD+ readiness activities could thus be expected to depend on the credibility and independence of their processes for the monitoring and evaluation of REDD+ readiness finance and their willingness to suspend funding arrangements in case of noncompliance.Footnote 241 Another example relates to the market incentives provided by the CCBA for the design and implementation of REDD+ projects that comply with its social and environmental standards. REDD+ projects certified with the CCB label have indeed attracted a premium on the voluntary carbon market.Footnote 242 More broadly, given that most of the start-up funding that currently exists for REDD+ projects originates in development aid and that corporate social responsibility is the primary motivation for buyers of REDD+ credits, the CCB label has increasingly become a basic requirement for entry into the voluntary carbon market.Footnote 243

A second pathway pertains to the manner in which the transnational legal process for REDD+ has provided opportunities for actors to socialize with one another and convey legal norms across multiple sites of law. As a result of socialization, actors may internalize legal norms because they have been actively convinced of their appropriateness (élite internalization) or because of their desire to adopt norms that have been widely accepted in their broader transnational reference group (acculturation). I will briefly mention two opportunities for socialization that have emerged from the transnational legal process for REDD+. To begin with, actors have socialized with one another as a result of their participation in the construction of legal norms in sites such as the UNFCCC, the FCPF, the UN-REDD Programme, the REDD+ SES, and the CCBA. Each of these sites has emphasized, to varying degrees, the sort of deliberation and inclusion that is generally seen by scholars as facilitating the generation of norms in a site of law.

In addition, these sites of law may also facilitate interactions between actors situated in or across other levels of law. One important example relates to the process for the review and approval of multilateral REDD+ readiness grants under the FCPF and the UN-REDD Programme. This process begins with the preparation and submission by a developing country government of a Readiness Preparation Proposal (R-PP),Footnote 244 which must be drafted in accordance with an established template that outlines six necessary components of jurisdictional readiness for REDD+.Footnote 245 This R-PP requires developing countries to address legal, policy, and governance issues relating to their jurisdictional REDD+ readiness processes and to ensure the full and effective participation of Indigenous Peoples and local communities in the design and implementation of activities.Footnote 246 The process by which an R-PP is approved for funding has generally followed a lengthy and transparent review process that has enabled multilateral agencies and their governing bodies, bilateral partners, and civil society actors to suggest changes in the first drafts of R-PPs submitted by developing country governments.Footnote 247

A third pathway is connected to the generation and sharing of knowledge about the enactment and implementation of legal norms within the transnational legal process for REDD+. This knowledge may lead actors in a given site of law to enact or implement an exogenous legal norm based on the evidence that they have acquired about the utility of doing so from the experience of other sites of law (instrumental learning). The transnational legal process for REDD+ has supported instrumental learning through the production and dissemination of knowledge products as well as the provision of training, capacity-building, and technical assistance for the implementation of REDD+. For instance, the FCPF and the UN-REDD Programme have released guidelines, tools, and other knowledge products that have provided developing countries with concrete guidance on how to respect and operationalize the rights of Indigenous Peoples and local communities in the context of their jurisdictional REDD+ readiness activities.Footnote 248 The REDD+ SES Initiative has also played a key role in developing and disseminating a methodology for the development of a set of social and environmental safeguards.Footnote 249 Likewise, the CCB Standards and related guidelines that the CCBA has released provide a methodology for the design, planning, and implementation of a REDD+ project.Footnote 250 Lastly, early experiences with the implementation of jurisdictional REDD+ activities as well as project-based REDD+ activities may also have exerted influence on other sites and levels of law for REDD+. For instance, negotiators within the UNFCCC have drawn on the knowledge generated by the pursuit of REDD+ readiness activities in developing countries and the rules provided by the multilateral, bilateral, and nongovernmental initiatives for REDD+.Footnote 251 Additionally, the implementation of REDD+ pilot projects in developing countries may, to some extent, have fed into their jurisdictional readiness effortsFootnote 252 as well as influenced other sites and levels of law.Footnote 253

A fourth and final pathway relates to the way in which the transnational legal process for REDD+ has provided enhanced opportunities for Indigenous Peoples and local communities to advocate for the recognition and protection of their rights vis-à-vis international, transnational, national, and local authorities (mobilization). By way of example, the FCPF, the UN-REDD Programme, and the REDD+ SES require that the proponents of jurisdictional REDD+ activities carry out extensive stakeholder engagement and consultation processes at the national level.Footnote 254 These consultations have provided unique platforms for Indigenous Peoples and Civil Society Organizations (CSOs) to advocate for the recognition and protection of their participatory and substantive rights in the context of jurisdictional REDD+ readiness efforts.Footnote 255 In addition to providing Indigenous Peoples and local communities with an opportunity for advocacy, international and transnational sites of law have also developed mechanisms to provide them with funding and otherwise support their participation in domestic REDD+ activities, including in the pursuit of project-based REDD+ activities.Footnote 256 As a result, the pursuit of jurisdictional REDD+ activities may have provided Indigenous Peoples Organizations (IPOs) and CSOs with additional resources and new opportunities for mobilizing on issues relating to the recognition and protection of the rights of Indigenous Peoples and local communities. Similarly, the CCB Standards require that the proponents of REDD+ projects conduct consultations with affected communities and other appropriate stakeholders,Footnote 257 thus providing another opportunity for mobilization and advocacy on the part of Indigenous Peoples and local communities.

To some extent, the plural, heterogeneous, and multidirectional nature of the transnational legal process for REDD+ aligns with the aspirations of many actors to experiment with, and learn from, the implementation of REDD+ across multiple sites of law.Footnote 258 On the other hand, there have been increasing concerns that the transnational legal process for REDD+ has become fragmented in ways that have created disconnects between different sites of law and related activities. As Corbera and Schroeder argue, REDD+ has evolved into “a slew of unorchestrated, multi-level, multi-purpose and multi-actor projects and initiatives” that “permeates multiple spheres of decision-making and organization, creates contested interests and claims, and translates into multiple implementation actions running ahead of policy processes and state-driven decisions.”Footnote 259 This sort of fragmentation has complicated efforts to operationalize REDD+ in developing countries and has prompted efforts aimed at enhancing coordination and collaboration across a range of multilateral, bilateral, and nongovernmental initiatives.Footnote 260