Introduction

Despite continual advances in biosafety and biosecurity policies, accidental pathogen escapes from laboratories continue to cause disease outbreaks in the community. The question is not if a pathogen will escape, but rather which pathogen will and what measures are in place to contain an escape with serious consequences [Reference Furmanski1]. Past laboratory-origin epidemics [Reference Meselson2–Reference Duizer4] and outbreaks of unknown origin [Reference Chen, Chughtai and MacIntyre5], namely the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) pandemic (2019–2023) [Reference Chen6], underscore the need to consider unnatural origins when identifying outbreaks.

Different lines of evidence, including phylogenetics, epidemiology, seroepidemiology and criminal or geopolitical intelligence, are required to determine whether an outbreak is of unnatural origin [Reference MacIntyre7]. Phylogenetics alone may not identify pathogens of laboratory origin because serial passaging a pathogen through an animal host will produce genetic markers that appear to be of natural origin [Reference MacIntyre7]. To investigate distinctive factors of laboratory-origin outbreaks, historically confirmed incidents should be studied to identify emerging themes and indicators.

A total of 70 incidents of accidental laboratory leaks have been reported, with the earliest recorded in 1901 and the most recent in 2024 (Appendix, Supplementary Table 1). Of these incidents, 56 (80.0%) resulted in community cases and 29 (41.4%) resulted in fatalities. Seven well-known cases that have bee comprehensively studied were selected for review: (i) 1955 Polio vaccine incident in western USA, (ii) 1977 H1N1 influenza virus re-emegence in China and the Soviet Union, (iii) 1979 Anthrax release in Sverdlovsk, Soviet Union, (iv) 1995 Venezuelan Equine Encephalitis epidemics in Venezuela and Colombia, (v) 2003-4 SARS-CoV-1 escapes from Singapore, Taiwan, and China, (vi) 2007 Foot-and-Mouth disease virus outbreak in Pirbright, England, and (vii) 2019 Brucella leak in Lanzhou, China, were comprehensively evaluated for insights into their geographical, epidemiological, phylogenetic and other characteristics. These indicators were used to explore whether similar epidemiological features have been discussed in relation to the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, without implying causality.

Methods

A literature review was conducted across the PubMed, ProMED-Mail, Scopus and Web of Science databases using keywords to identify published literature on the seven laboratory-confirmed outbreaks. Public information accessible on the World Health Organization (WHO) and the Centres for Disease Control (CDC) platforms was gathered, as well as relevant news articles, government reports, correspondence and grey literature published during the respective outbreaks. The information collected included historical facts, witness accounts, outbreak investigations, characteristics of the outbreak and strain, epidemiological parameters and descriptive statistics. An article or report was excluded if it contained no information on any risk variables analysed (geographical spread, genetics and phylogeny, epidemiological factors, timely and accurate reporting/infodemic).

Summary of case studies

The Cutter Laboratories polio vaccine trials across the western United States

Poliomyelitis epidemics plagued the world in the 1950s, leading to intensive research into the development of inactivated or live-attenuated vaccines for poliovirus [Reference Berche8]. In April 1955, Cutter Laboratories in California was licenced to produce the Salk formaldehyde-inactivated polio vaccine (IPV), following successful trials [Reference Meldrum9]. However, some batches produced by Cutter Laboratories were insufficiently inactivated and contained live poliovirus [Reference Offit10, Reference Nathanson and Langmuir11]. Multiple children received these contaminated doses, leading to tens of thousands of abortive infections, dozens of paralytic cases and several deaths, including secondary transmission within families and communities [Reference Nathanson and Langmuir11, Reference Offit12]. The incident shook public trust in vaccines, reshaped vaccine policy and became a defining moment in the history of vaccine safety.

Geographical spread

Approximately 120,000 contaminated doses were administered to primarily grade-school children, and roughly 400,000 people received the Cutter vaccine during a 10-day period in mid-April. A majority of them developed abortive polio [Reference Berche8]. Most cases occurred between late April and May 1955, then declined sharply by June, aligning with the vaccination window [Reference Nathanson and Langmuir11]. Ultimately, at least 220,000 people were exposed, including 100,000 household contacts of immunized children, resulting in 164 cases of severe paralysis and 10 deaths [Reference Nathanson and Langmuir11].

Infections clustered in states where the Cutter vaccine was widely used. California and Idaho experienced the highest numbers, while nearby states saw smaller outbreaks. Idaho typically reported very low polio incidence (11 cases) during April–June in 1950 to 1954. In 1955, however, an eightfold increase (88 cases) was observed, of which 84 were attributable to vaccine–associated cases [Reference Nathanson and Langmuir13].

Genetic and clinical evidence

Paralytic poliomyelitis developed 4 to 10 days after vaccination in patients [Reference Nathanson and Langmuir11], with paralysis typically beginning in the inoculated arm, a pattern less common in natural poliomyelitis cases [Reference Offit12, Reference Nathanson and Langmuir13]. All early cases were linked to Cutter vaccine recipients, with secondary cases in their families and community contacts [Reference Nathanson and Langmuir13, Reference Nathanson and Langmuir14]. Severe neurological complications involving the central nervous system were noted in those who were administered the vaccine, as compared to family contacts as well [Reference Nathanson and Langmuir14]. The incidence of paralytic disease peaked in children aged 7 across the western US, reflecting an unusually high concentration of poliomyelitis in children, likely because they were heavily vaccinated under school programs in this region [Reference Hall, Nathanson and Langmuir15].

Laboratory investigations revealed that live type 1 poliovirus (the causative agent of the Cutter vaccine-associated cases) was isolated from 7 of 8 vaccine lots, demonstrating failed inactivation. Additional findings of types 2 and 3 poliovirus in certain lots underscored multiple strains of poliovirus circulating at the time, even though types 2 and 3 did not result in clinical cases [Reference Nathanson and Langmuir14, Reference Thrupp16].

Epidemiological factors

The number of cases among Cutter vaccine recipients and their contacts far exceeded what would be expected for natural poliomyelitis at the time, and vaccine recipients from other manufacturers showed no such pattern [Reference Nathanson and Langmuir13]. Moreover, Cutter vaccine-associated cases declined as cases of seasonal poliomyelitis began to increase [Reference Nathanson and Langmuir13].

Incubation periods among vaccinated children ranged from 4 to 15 days, shorter than the typical interval for naturally occurring polio, whereas contact cases showed incubation periods consistent with secondary transmission [Reference Nathanson and Langmuir11]. Vaccinated cases peaked approximately 1 week after vaccination, and secondary cases peaked 3 weeks after the midpoint of vaccination. The appearance of cases in waves is suggestive of a common-source outbreak [Reference Nathanson and Langmuir13].

Attack rate analysis of the vaccine lots revealed that two of three production pools were inadequately inactivated and accounted for a more than 10-fold increase in paralytic cases [Reference Nathanson and Langmuir11]. Secondary attack rates in household contacts were similar to those seen in natural poliomyelitis, with limited spread to wider community contacts [Reference Nathanson and Langmuir13].

Timely and accurate reporting/Infodemic

The Salk vaccine was licenced within a day under political pressure and distributed widely within two weeks [Reference Offit10]. Although the vaccine had passed required safety testing [Reference Thrupp16], biosafety concerns at Cutter Laboratories were identified, including the use of the highly virulent Mahoney strain, insufficient viral inactivation and inadequate safety testing [Reference Offit10]. The vaccine was swiftly withdrawn on April 27 after cases rose sharply [Reference Nathanson and Langmuir11].

Overall, communication with other scientists and the government was poor. Swedish researchers, such as Sven Gard, presented research showing that Salk’s vaccine inactivation procedure was ineffective [Reference Axelsson17–Reference Clark19]. Despite these concerns, Salk did not make the proposed changes, and the vaccine trial was launched in 1954, even though regulators lacked the capacity to validate each dose during production, relying on manufacturers for quality assessment [Reference Offit10, Reference Axelsson17].

In fact, a similar incident was documented in which another company using the Salk IPV, Wyeth Laboratories, was responsible for 37 vaccine-associated poliomyelitis cases. Yet, the report was kept confidential from public health authorities and the public [Reference Offit10, Reference Axelsson17].

Media further contributed to misinformation and infodemics, which eroded public trust in vaccines. Vaccine rates significantly dropped across the world [Reference Axelsson17, Reference Day20]. The Cutter polio vaccine incident contributed to the shift toward Sabin’s oral polio vaccine (OPV) in the 1960s [Reference Berche8]. Both the Salk and Sabin vaccines were also found to have been contaminated with Simian Vacuolating Virus (SV40) due to inadequate formaldehyde inactivation of the monkey kidney cells used to cultivate poliovirus [Reference McCormick, Almario, Stratton, Stratton, Almario and McCormick21]. This led to SV40-contaminated polio vaccines being administered to millions of people between 1955 and 1963 [Reference Berche8].

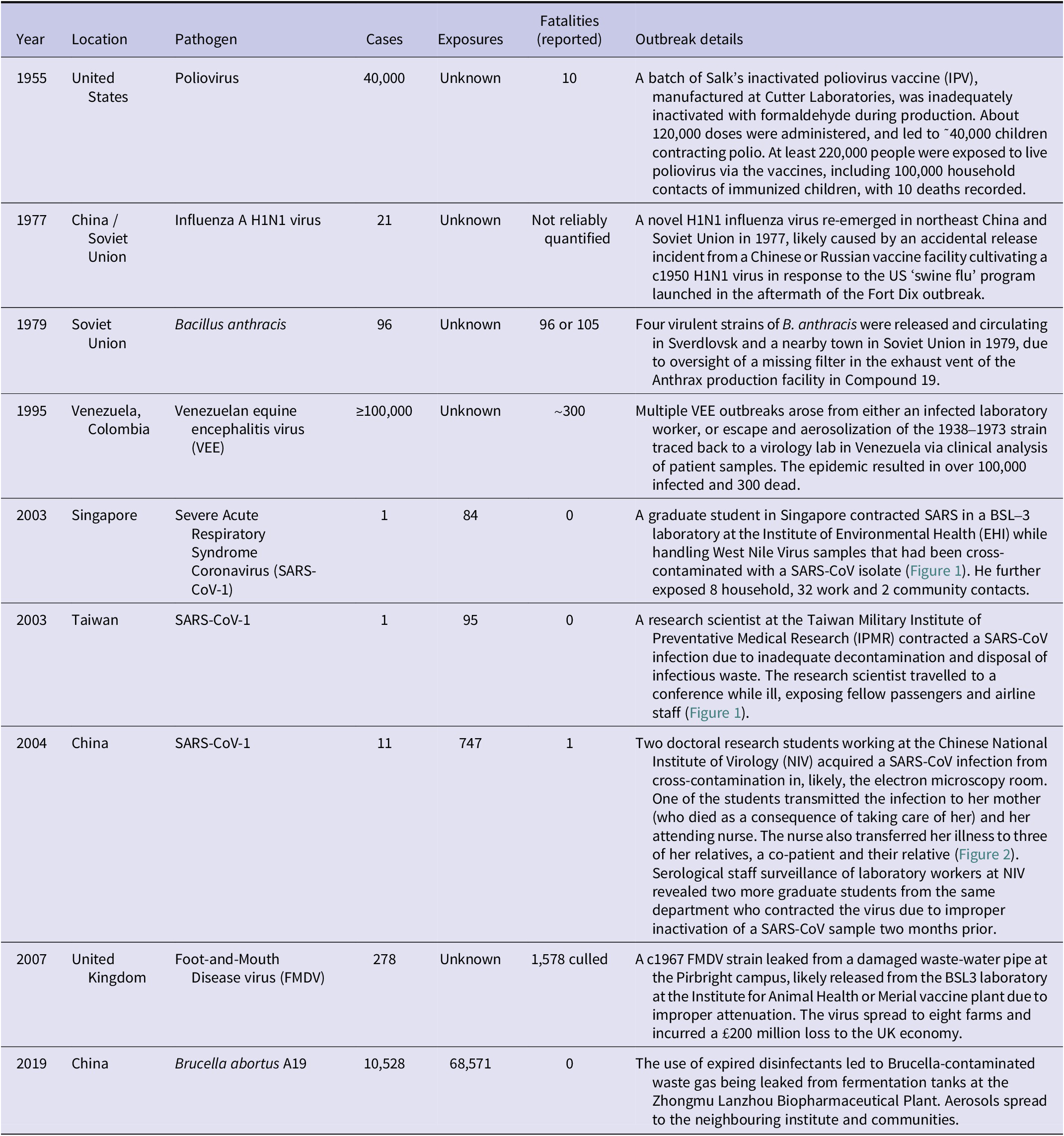

Table 1. Summary details of selected case studies of laboratory outbreaks

Note: Fatality figures reflect officially reported deaths at the time of investigation; where reliable global estimates are unavailable or contested, entries are qualified to indicate uncertainty or under-reporting. “Unknown” indicates that exposure counts could not be reliably reconstructed from available contemporaneous records or retrospective analyses.

The re-emergence of the H1N1 influenza virus in China and the Soviet Union

Every pandemic influenza strain has replaced its predecessor strain [Reference Webster22, Reference Zimmer and Burke23]. However, in 1977, two serotype A viruses were recorded to co-circulate for the first time in history: the dominant H3N2 subtype and the previously extinct human influenza A H1N1 virus [Reference Finkelman24]. This situation was due to an accidental release during laboratory activities.

Geographical spread

The H1N1 influenza re-emerged in northeast China in May 1977 and soon after in the eastern Soviet Union [25]. The Soviet Union reported the outbreak to the WHO in September 1977, followed by Chinese reports in May 1978 [Reference Kung26]. The c.1957 H1N1 virus strain initially spread in the Soviet Union, Hong Kong and China, then rapidly worldwide, causing mild infections in individuals under 21 while excess mortality was largely confined to older populations, with global death estimates varying widely. [Reference Kung26, Reference Scholtissek27].

Genetic and clinical evidence

Genetic analysis showed that the 1977 H1N1 virus outbreak strain was closely related to strains from 1949–1950 but distinct from the 1947 or 1957 strain [Reference Scholtissek27], suggesting it had likely been preserved since 1950 [Reference Scholtissek27] and accidentally released when population immunity to H1 and N1 antigens declined [Reference Berche8].

Many isolates from the outbreak were temperature-sensitive, a marker of laboratory manipulation distinctive to live attenuated influenza vaccine (LAIV) studies. However, not all strains were temperature-sensitive [Reference Oxford28]; a mixed population of strains suggests a possible escape event during the temperature-sensitivity selection experiment [Reference Kung26, Reference Oxford28]. The outbreak strain had low virulence, varied attack rates within the same region and a low mortality rate, likely owing to attenuation and pre-existing immunity in the older population [Reference Furmanski1, Reference Kung26].

Epidemiological factors

The H1N1 virus spread more slowly nationwide in Liaoning (May–October) than the Asian H2N2 pandemic in 1957 (February to March) [Reference Kung26]. This unusual disease progression may have been due to an unfavourable season, although off-season outbreaks suggest an unnatural origin.

Two factors suggest that an incompletely attenuated vaccine strain caused the outbreak: ongoing research on LAIV at the time [Reference Furmanski1] and the renewed interest in prophylaxis following the 1976 H1N1 outbreak at Fort Dix, New Jersey [Reference Lessler29]. It is plausible that a Chinese or Russian vaccine facility thawed and cultivated a c.1950 H1N1 influenza virus in response to the US ‘swine flu’ program launched in the aftermath of the Fort Dix outbreak [Reference Furmanski1].

Timely and accurate reporting/Infodemic

The source was debated, with suggestions of an accidental escape being refuted by Chinese and Soviet virologists [Reference Kung26]. Western scientists refrained from discussing the laboratory-origin theory to foster collaboration amid Cold War tension [Reference Furmanski1]. Natural-origin hypotheses included the possibility of viral latency in an unspecified animal reservoir. In 2006, a paper suggested that the virus emerged from migratory birds at Siberian lakes, after isolating strains mistaken for avian H1N1 influenza virus from meltwater. The paper was criticised in 2008, where direct evidence demonstrated that the meltwater strain, ironically, was also leaked from a laboratory [Reference Worobey30]. In 2009–2010, the laboratory release theory became widely accepted [Reference Furmanski1].

The release of inhalational anthrax from an exhaust vent in Sverdlovsk, Soviet Union

After WWII, the Soviet Union established an anthrax production plant [Reference Alibek and Handelman31] in their Military Research Facility: Compound 19 in Sverdlovsk. The causative agent, Bacillus anthracis, mainly affects domestic animals and, occasionally, humans via cutaneous transfer or, rarely, through ingestion or inhalation [Reference Riedel32]. Natural anthrax is almost always cutaneous, and inhalational anthrax should raise suspicion towards a deliberate event [Reference Riedel32].

A clogged filter in the exhaust vent was removed but not replaced; machines ran for several hours as usual [Reference Alibek and Handelman31]. Anthrax aerosols escaped to a ceramic plant and a town nearby, where many workers were discovered ill. Within a week, most exposed workers had died, and hospitals received an influx of patients from different towns [Reference Alibek and Handelman31].

Geographical spread

According to Soviet reports, the epidemic began in late March, took place from 4th April to 18th May 1979, and caused a total of 96 cases with 66 fatalities [Reference Meselson2]. Witnesses claimed a death toll of ~105 [Reference Alibek and Handelman31], and an article quoted as many as a thousand deaths [Reference Riedel32]. The actual number of human fatalities or cases remains unknown, as it was reported that the KGB destroyed most hospital records [Reference Alibek and Handelman31, Reference Abramova33]. In an attempt to conceal the truth, the incident was falsely attributed to gastrointestinal anthrax (a rare manifestation) resulting from consumption of anthrax-contaminated meat [Reference Alibek and Handelman31].

Genetic and clinical evidence

Genetic studies dated the accident to April 3rd or 4th, 1979, consistent with the observed anthrax incubation period. The Soviet officials falsely reported the start date as March 30th 1979, manipulated medical records of early cases and issued fabricated death reports to the victims’ families as part of the cover-up [Reference Alibek and Handelman31]. They also denied inhalational anthrax, although this was later confirmed from autopsy data [Reference Abramova33].

Epidemiological factors

It was estimated that victims were exposed to a far lower infectious dose (~1–10 or 100–2,000 spores) than observed for naturally occurring inhalational anthrax (8,000–10,000 spores) [Reference Wilkening34], signifying a potentially weaponised strain. This is consistent with early clinical studies, where more than four virulent strains of B. anthracis circulating during the accident were all traced to the biological weapons facility [Reference Jackson35].

Most infected patients worked or lived close to the military facility (within 4 km)35, with animal cases detected up to 60 km away [Reference Meselson2]. The aerosol size was estimated to be <5–10 μm to have allowed for extended dispersal and prolonged infection, more extensive than that observed in the 2001 ‘Amerithrax’ attacks (<5 μm) [Reference Wilkening34].

Autopsies confirmed that fatal cases resulted from inhalation exposure [Reference Abramova33], a rare clinical form of natural anthrax [Reference Wilkening34]. The mean incubation period of the Sverdlovsk accident (~10 days, with some cases appearing after 43 days)2 was longer than that of naturally occurring anthrax outbreaks and even the 2001 Amerithrax intentional anthrax release (4–6 days)35.

Timely and accurate reporting/infodemic

In November 1979, a Russian magazine reported that in April, ‘an explosion in the military facility of Sverdlovsk had released a cloud of deadly bacteria’ [Reference Alibek and Handelman31]. Western agencies later picked up coverage of the outbreak [Reference Meselson2], alleging it was a violation of the 1972 Biological Weapons Convention, although all claims of a laboratory accident were denied.

Workers in Compound 19 raised biosafety concerns about airborne spores in the laboratory, clogged filters and neglected maintenance checks [Reference Alibek and Handelman31]. After the accident, senior officers were alerted, but city officials and the Ministry of Defence in Moscow were not informed.

On June 12, 1980, residents of Sverdlovsk were informed that the outbreak was caused by contaminated meat from illegal wet market stalls, leading to the culling of more than 100 stray dogs and animals in the vicinity [Reference Alibek and Handelman31].

Soviet authorities denied requests to permit independent scientists to investigate the incident [Reference Meselson2]. An ‘information war’ arose between those doubting a natural outbreak and those convinced of its natural origin. It took nine years for Soviet medical experts to disclose information about the Sverdlovsk incident to the US and thirteen years for then-Soviet President Boris Yeltsin to admit to the accident [Reference Furmanski1].

The VEE epidemics in Venezuela and Colombia

In 1995, one of the largest epidemics of VEE was documented in Venezuela and Colombia [Reference Berche8]. VEE is an arboviral disease transmitted by mosquitoes that causes intermittent epizootics and sometimes human epidemics across the Americas. Equine disease is severe, while human infections range from asymptomatic to acute febrile illness with neurological complications, and fatality rates of 4 to 14% [Reference Furmanski1, Reference Berche8]. Naturally, VEE circulates at low levels in enzootic cycles. The enzootic strains (ID, IE, IF, II–VI) rarely cause major outbreaks, which occur only when an enzootic strain mutates into an epizootic subtype (IAB or IC) that efficiently amplifies in equines and drives widespread human spillover [Reference Weaver36, Reference Powers37].

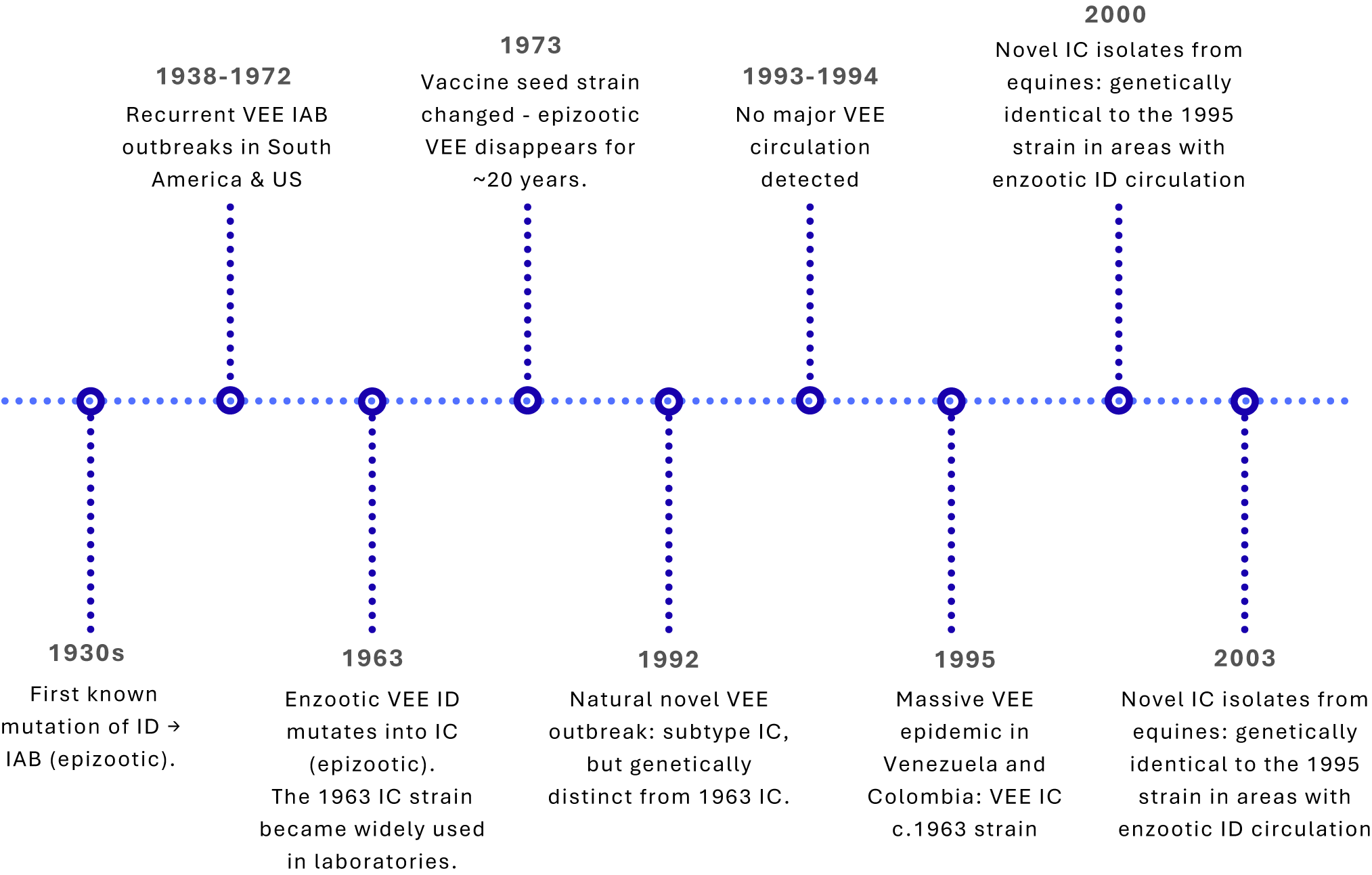

Epizootic strains have mutated from enzootic only three times (ID→IAB in the 1930s; ID→IC in 1963 and again in 1992). However, many VEE outbreaks reported from the late 1930s through early 1970s were traced to inadequately inactivated veterinary vaccines derived from the 1938 IAB strain [Reference Weaver38, Reference Kinney39]. Residual live virus in the vaccines repeatedly sparked outbreaks until the seed strain was replaced with an attenuated variant in 1973, after which epizootics ceased for nearly 20 years [Reference Weaver38, Reference Pittman40] (Figure 1). Unlike the IAB strains, there is no record that subtype IC strains were ever used in vaccine production, hence an unlikely source of the 1995 outbreak.

Figure 1. Timeline of Venezuelan equine encephalitis (VEE) virus outbreaks and laboratory-associated events.

The 1995 outbreak in Venezuela and Colombia was unusual because this strain matched an IC virus used in diagnostic reagents in a local virology laboratory, one previously shown to contain live virus. Many investigators concluded that the 1995 epidemic most likely resulted from an inadvertent laboratory escape rather than natural evolutionary emergence [Reference Brault41, Reference Weaver42].

Geographical spread

In April 1995, veterinarians in Venezuela first detected equine deaths suggestive of VEE, followed by human febrile cases [Reference Rivas43]. The outbreak began in eastern Falcón State, Venezuela and spread westward across states by mid-July. Transmission intensified in rural areas by late August, and by September–October, large numbers of human and equine cases were reported in the Colombian state of La Guajira [Reference Weaver42, 44]. Overall, the epidemic caused ≥ 100,000 human cases and ~ 300 deaths [Reference Brault41–Reference Rivas43].

VEE outbreaks typically emerge in regions with known enzootic subtype ID circulation, and within localized equine–mosquito amplification cycles [Reference Weaver36, Reference Powers37]. The only historical exception was the 1969–1971 outbreak originating in the Guajira peninsula, although the area had prior enzootic ID activity [Reference Walder, Suarez and Calisher45]. In contrast, the 1995 outbreak began abruptly in Falcón State, a region with no record of circulation of closely related enzootic ID progenitor strains [Reference Salas46], or of laboratories or vaccine production facilities in close proximity [Reference Navarro47].

Heavy rainfall in the normally arid Guajira region increased vector densities and expanded the spread [Reference Weaver42]. However, unlike natural transmission patterns, the outbreak spread rapidly through rural areas with limited equine populations, suggesting that human–mosquito–human transmission was also occurring.

Importantly, the 1995 virus was identical to a subtype IC antigen strain that was in regular use for antigen preparation in laboratories near the outbreak area at the time [Reference Brault41].

Genetic and clinical evidence

Genomic analyses showed that the 1995 outbreak virus was subtype IC, which had previously caused two other major epidemics (1962 to 1963 and 1992 to 1993). It was a genetic match to a strain isolated in 1963, which had disappeared from nature 30 years ago [Reference Brault41]. The 1995 viral sequence showed almost no evolutionary change during the interepidemic period, inconsistent with estimates of epidemic and enzootic VEE virus evolution rates, which indicate a relatively steady rate of nucleotide substitutions, on the order of 2–4 × 10−4 substitutions/nucleotide/year [Reference Weaver48–Reference Estrada-Franco51].

Phylogenetic analysis demonstrated sequence identity to the P676-ag virus, isolated from a 1982 antigen preparation used for diagnostic testing in Venezuela [Reference Brault41], explaining the genetic conservation between the epidemic events.

Clinically, infected humans exhibited high viremias comparable to those in equines, sufficient to infect the epidemic mosquito vector [Reference Weaver42, Reference Suárez and Bergold52, Reference Sudia53]. Higher disease incidence was observed in unimmunized equines, particularly donkeys, due to low equine immunization rates in the region [Reference Rivas43].

Epidemiological factors

The 1995 VEE epidemic displayed attack rates of ~ 36%, with some communities reporting rates as high as ~ 93%, far exceeding typical VEE epizootic patterns [Reference Rivas43]. However, secondary attack rates were low in Colombian communities, and no secondary infections occurred among Venezuelan healthcare workers, indicating low person-to-person transmission despite extensive community spread [54].

Field studies, before and after the epidemic, found no evidence of ongoing circulation of epizootic IAB or IC strains [Reference Walder, Suarez and Calisher45, Reference Salas46, Reference Dickerman55], or enzootic ID viruses genetically related to the 1995 IC strains in northern Venezuela, demonstrating an absence of local natural reservoirs for the disease [Reference Salas46].

Natural transmission often generates genetic shift or drift due to low-dose mosquito transmission, which was not observed with the implicated strain [Reference Weaver56, Reference Weaver, Scott and Lorenz57]. Furthermore, the much faster geographic spread of the 1995 outbreak compared to the natural 1962–1964 epizootic suggests an atypical introduction rather than gradual local emergence [Reference Weaver42].

Timely and accurate reporting/Infodemic

The Colombian Ministry of Health and Animal Health Service deployed timely surveillance across La Guajira, generating real-time intelligence to guide vector control, equine vaccination and movement restrictions. Implementation of early interventions, in line with animal health regulations, helped prevent wider domestic or international spread at a time when heavy rainfall had increased vector density and heightened epidemic risk [44].

While the spread of infodemic during the outbreak was limited, scientific discourse on the origins of the virus emerged years after the epidemic [Reference Brault41]. Between 2000 and 2003, outbreaks of a subtype IC strain genetically identical to the 1995 virus were reported in Venezuela, despite the strain no longer being widely used in laboratories (Figure 1) [Reference Navarro47]. From 1995 to 2000, this IC lineage showed a ≈ 10-fold slower evolutionary rate, implying limited replication compared with typical mammal, mosquito, or equine transmission cycles [Reference Navarro47]. Field investigations failed to identify reservoir hosts or vectors, and the outbreaks occurred at the end of the rainy season, which is not typical of the VEE epidemic pattern [Reference Navarro47]. The 2000 strains also did not cluster phylogenetically with the P676-ag strain, and the 2000s outbreak locations were not near any diagnostic or vaccine production laboratories that work with VEE virus either [Reference Navarro47]. These findings suggest that the 2000 outbreaks involved naturally circulating strains that have remained genetically stable since the 1995 laboratory release. While these anomalies led the VEE working group to reconsider their suggestion of a laboratory origin, direct evidence of a natural mechanism causing prolonged genomic stasis in the subtype IC lineage was not identified.

The SARS-CoV-1 escapes in Singapore, Taiwan and China

The initial risk of contracting SARS-CoV-1 through laboratory exposure is very high – even a single mishap could lead to a potential pandemic [58]. This was evidenced by six documented escapes from high-containment virology laboratories: one from a Biological Safety Level (BSL) 3 in Singapore, one from a BSL-4 in Taipei and 4 from the same BSL-3 in Beijing [Reference Furmanski1]. Despite raising public health alarms, these escapes are not referenced in historical and official reviews of SARS-CoV infections.

A laboratory exposure incident in Singapore

In August 2003, a graduate student at the National University of Singapore (NUS) contracted SARS in a BSL-3 laboratory at the Institute of Environmental Health (EHI) Singapore despite handling West Nile Virus (WNV). Examination of the vials revealed that the WNV samples had been cross-contaminated with a SARS-CoV-1 isolate [Reference Lim59]. The student’s sample-preparation techniques were speculated to be the cause of infection. The infected student exposed 8 household contacts, 2 community contacts, 32 hospital contacts and 42 work contacts, of whom 25 were placed under home quarantine [Reference Lim59]. No secondary cases occurred.

Investigations in the laboratory revealed poor record-keeping, missing or defective equipment, a lack of freezers and HEPA/air filter problems, all of which were exacerbated by the student receiving insufficient training in BSL-3 procedures [60].

A laboratory spill in Taiwan

In December 2003, research scientist Lieutenant-Colonel (LTC) Chan Jiacong at the Taiwan Military Institute of Preventive Medical Research (IPMR) acquired a SARS-CoV-1 infection, before travelling to Singapore for a conference, where he exposed fellow passengers and airline staff [61].

While working with SARS-CoV-1, LTC Chan found a leaking waste bag; in a hurry to travel, he inadequately disinfected the spill and incorrectly disposed of the waste without appropriate personal protective equipment [62]. WHO investigations revealed numerous safety violations in the laboratory, including poor record-keeping, long work shifts (12–14 h) and the absence of incident-reporting protocol [61]. Original reports cited 95 contacts placed in quarantine, while WHO investigations reported only 74 contacts [Reference Furmanski1].

A laboratory-origin SARS-CoV-1 outbreak in China

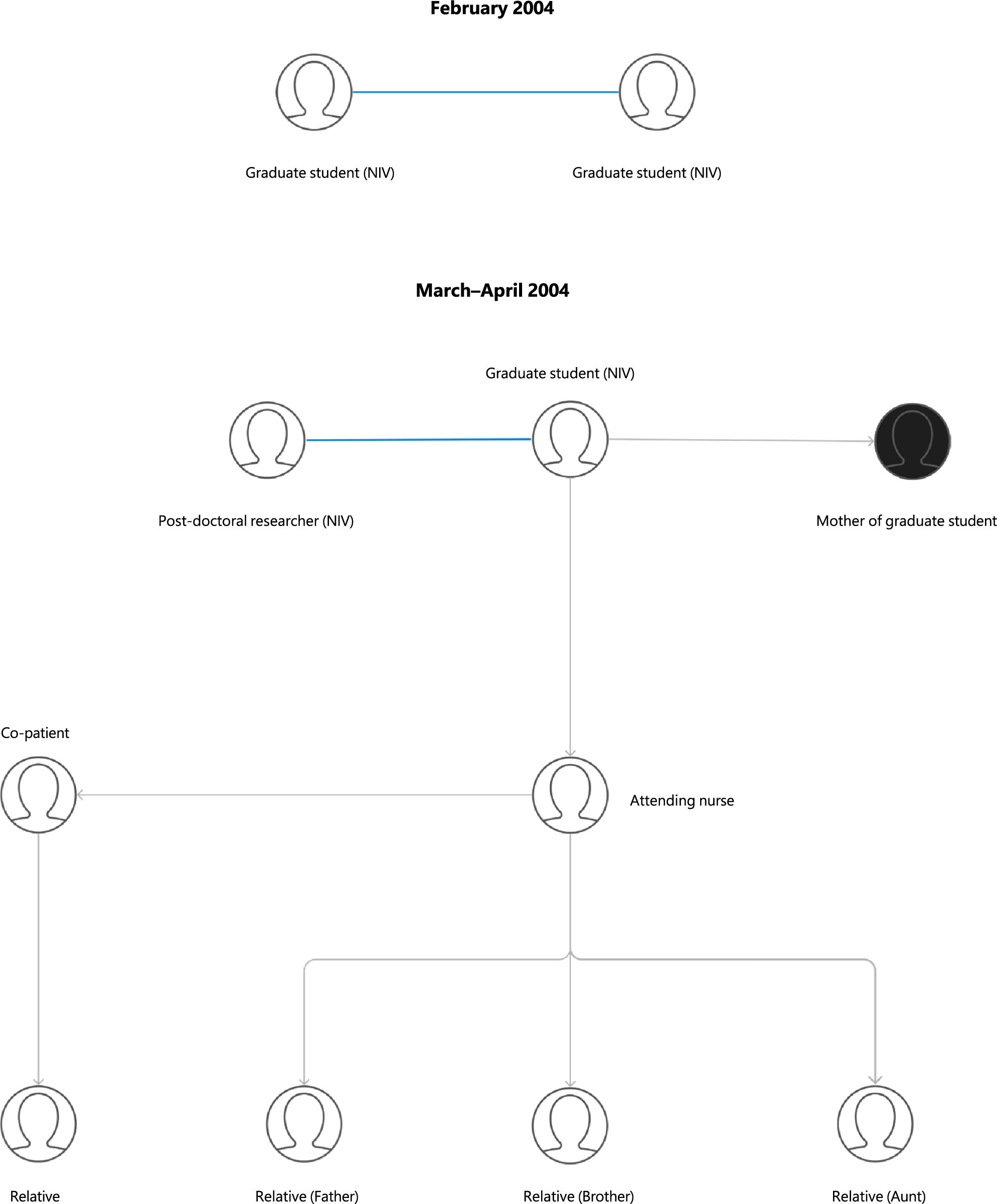

In April 2004, reports of a nurse with a hospital-acquired SARS-CoV-1 infection came from Beijing, China. She had contracted the illness from a graduate student who was admitted for pneumonia in March. Eventually, the disease spread among their family contacts and healthcare workers over three generations, causing one death [Reference Demaneuf63]. Official reports initially accounted for 9 total cases; however, investigations revealed 2 additional cases from February 2004 [Reference Liang64] (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Transmission chains and epidemiological links in laboratory-associated SARS-CoV-1 outbreaks in China (2004). Key: Blue line = independent infection from the same laboratory; Black circle = death.

Geographical spread

The graduate student was interning at the viral diarrhoea department of the Chinese National Institute of Virology (NIV) in Beijing, a part of the China Centre for Disease Control (CCDC), and did not work with SARS-CoV nor in a BSL-3 laboratory; the exact mechanism of infection is unknown [Reference Furmanski1]. She travelled home by train while ill, where her mother developed a severe infection and died as a consequence of attending to her. The nurse who had contracted the illness from the student also transferred it to an additional five individuals (Figure 2) [Reference Demaneuf63]. Investigations found another post-doctoral researcher at NIV who had been infected with SARS-CoV on April 17, 2004 [Reference Liang64]. By the end of April, officially, 747 people were quarantined at NIV [Reference Furmanski1] and unofficially, over a thousand people [Reference Demaneuf63].

Further investigation found two more graduate students from the same department at NIV who contracted SARS-CoV independently in February [Reference Liang64] (Figure 2). Official reports suggest that one of the doctoral students improperly inactivated a SARS-CoV sample, contaminating the electron microscopy room, from which the second student also acquired the infection [Reference Demaneuf63]. Neither student caused secondary cases, and both recovered. The deactivation solution prepared to inactivate SARS had not been verified or recommended by the Ministry of Health [Reference Demaneuf63].

Epidemiological factors

Healthcare workers account for almost 16% of probable SARS-CoV cases with attack rates of >56% [Reference Liang65]. The attack rate (4.23%) and case fatality rate (9.1%) observed in the Beijing escapes were lower than the standard [Reference Liang65], perhaps owing to timely interventions, such as quarantine and isolation, that prevented the outbreak from spreading further. The disease outbreak also occurred in the summer, a low season for virus spread.

Timely and accurate reporting/Infodemic

A joint WHO–China report reviewed the cases, although it did not mention two primary cases from February, which were officially discovered in May via IgG testing [Reference Liang64]. As both students were hospitalized in February, the LAIs were known prior to the antigen testing. Perhaps these cases were not disclosed by the institution in the April report [Reference Demaneuf63], as they were later recognised in a WHO report in October 2004 [66]. The WHO highlighted biosafety shortcomings with handling live SARS-CoV and surveillance of LAIs at NIV [Reference Furmanski1].

The Foot-and-Mouth virus leak from drainage pipes in Pirbright, England

The United Kingdom was free of Foot-and-Mouth Disease (FMD) for six years until its re-emergence in 2007 [67]. FMD virus (FMDV) predominantly infects cattle, sheep and pigs, with rare cases of mild illness in humans [Reference Blacksell68]. It is highly transmissible and can spread via contaminated surfaces, aerosols (up to 250 km) and fomites [Reference Furmanski1, Reference Blacksell68]. The FMD outbreak in 2001 incurred a $16 billion loss to the British economy [Reference Furmanski1]. On 3rd August 2007, the United Kingdom reported an FMD outbreak detected on a cattle farm in Surrey [Reference I69]. The pathogen escaped from the Pirbright campus, the only authorized facility in the UK for storing FMDV, specifically the Institute for Animal Health (IAH) and Merial, a vaccine manufacturer.

Initial investigations ruled out aerosol or surface water transmission from Pirbright [70]. Eventually, they revealed a damaged wastewater pipe connecting the Merial vaccine plant to the waste treatment plant in IAH, leaking partially treated waste into the ground and surface water. FMDV-contaminated mud was carried from the campus to the farms via flooding, roads and the tyres of construction vehicles parked at the site [Reference I69]. FMDV likely spread further via windborne and fomite transmission and was exacerbated by visitor car parks located near livestock areas [Reference I69].

Geographical spread

The 2007 FMD outbreak infected 8 premises and 278 animals, necessitating the culling of 1,578 animals and resulting in estimated losses of £200 million [Reference Ryan71]. The epidemic comprised two distinct clusters: two farms in the first cluster and six in the second [Reference Bessell72]. The intermediary farm between the two infection clusters was missed during initial surveillance [Reference I69].

Genetic and clinical evidence

The outbreak-causing virus was FMDV serotype O subtype BFS 1860 isolated in 1967, a strain no longer circulating globally [Reference I69, 70] but used in large quantities (10,000 l) at the Merial facility and in microquantities at IAH [70]. Both facilities fault the other, leaving the exact location of the outbreak uncertain [Reference Furmanski1]. Genomic analysis indicated a single escape of FMDV from Pirbright, dating between 13 and 26 July 2007 [Reference Ryan71], which caused the August outbreak and re-emerged in mid-September 2007.

The first cases of FMD were discovered in cattle, although pigs are more sensitive to FMDV infection in natural or introduced outbreaks and are often the first animals infected [Reference Alexandersen73]. Additionally, ruminants are more susceptible to airborne infections [Reference Alexandersen and Donaldson74], and the FMDV vaccine production guidelines also focus on efficacy testing and immunization in cattle [Reference Stenfeldt75]. The outbreak strain, which shows a greater affinity for ruminants, may indicate a released FMD vaccine strain.

Epidemiological factors

The second outbreak cluster began after a significant temporal lag [Reference Bessell72]; the epidemic was prematurely deemed over, restrictions on livestock movement were lifted and farm surveillance was eased [Reference I69]. Molecular analysis revealed that one of the two originally classified primary farms had been infected by the other, initially overlooked because it lay beyond the 10 km radius for animal epidemic monitoring [Reference Ethelberg76].

Furthermore, risk mapping of the 2007 outbreak indicated an extremely low likelihood of local spread compared to the 2001 FMD outbreak [Reference Bessell72], with the sparse livestock density in Surrey raising suspicion of unnatural origins. Moreover, the R0 for the 2007 outbreak was ~15, much higher than that for the 2001 outbreak (~4 [Reference Ryan71]. While the 2007 strain was more transmissible, there is evidence that a very low level of virus was circulating in infected animals [Reference Ryan71].

Timely and accurate reporting/Infodemic

The outbreak had a limited infodemic, as animal disease reporting is more strictly enforced and standardized, with delays in reporting risking immediate trade bans and fines. Under the World Organisation for Animal Health (WOAH, formerly known as the OIE) Animal Health Code, member states must notify within 24 h of confirmation [77], while the WHO International Health Regulations (IHR) allow 48 hours [78] with no tangible penalties. Animal health surveillance covers a wider radius with multiple detection points, e.g., mandatory farm reporting, abattoir checks, etc. [79], whereas human health surveillance relies on public health data sharing, often hindered by resource constraints or patient privacy laws [Reference Wilson, Halabi and Gostin80].

Systemic gaps in communication and reporting were mirrored in site conditions, where long-term damage to drainage pipework was known but unaddressed until FMD emerged in nearby farms [Reference Walker81].

The Brucella-contaminated waste-gas leak in Lanzhou, China

Incident description

The Lanzhou Brucella leak is the largest and longest recorded laboratory-origin outbreak [Reference Pappas82], surpassing the 1977 H1N1 and 1979 Sverdlovsk anthrax events [Reference Meselson2]. Brucellosis, a globally prevalent zoonotic disease, poses significant public and animal health concerns despite its low human mortality rate [Reference Pappas83]. It is transmitted to humans via contact with infected livestock, ingestion of unpasteurized dairy or undercooked meat, and, less commonly, aerosol inhalation, often from laboratory accidents or releases during microbiologic technique [Reference Ackelsberg84].

The first cases of Brucella spp. infections were detected in November 2019 at the Lanzhou Veterinary Research Institute (LVRI) in Gansu, China, with 181 positive individuals by December [Reference Liu85]. The outbreak originated from the Zhongmu Lanzhou Biopharmaceutical Plant, a state-owned facility producing Brucella vaccines for animals [86]. Expired disinfectants led to contaminated waste gas leaking from fermentation tanks downwind to LVRI and neighbouring communities [Reference Pappas82].

Geographical spread

Although the factory’s manufacturing licence was revoked immediately, transmission continued for at least 12 months [Reference Pappas82]. By 30 November 2020, the Health Commission of Lanzhou reported 10,528 cases among 68,571 tested [86]. No deaths were reported, but the full extent of cases is inconclusive due to limited published official data [Reference Pappas82, Reference Pappas83].

Genetic and clinical evidence

The leaked strain was a Brucella abortus A19 vaccine strain, [Reference Pappas83]. Owing to its low infectious dose Brucella spp. accounts for almost 2% of all LAIs [Reference Robichaud, Libman, Behr and Rubin87], with many documented in China since 1936 [Reference Pappas83].

Prior incidents

In 2017, a similar outbreak caused by Brucella suis S2 vaccines was reported in Gansu, where 51 animal epidemic prevention controllers were positive (attack rate: 24.8%) [Reference Liu85]. In December 2020, another incident occurred at a biological products company in Chongqing, where 61 workers were positive (attack rate: 43.6%). The infection spread to nearby departments [Reference Liu85]. Neither facility complied with biosafety regulations: improper handling techniques, ineffective PPE and ineffective emergency measures were identified [Reference Pappas83].

Epidemiological factors

Brucella was transmitted by aerosols from late July to August 2019 [Reference Pappas82, Reference Pappas83], but the attack rate observed with the Lanzhou leak was much lower than typical laboratory exposures (~30%–100%) [Reference Yagupsky88], ranging from ~12.9% to 15.4%. Moreover, no deaths were reported despite a case-fatality rate of 1–2% for brucellosis.

Brucellosis outbreaks in Lanzhou are unusual, with low seroprevalence from 2013 to 2018, and has never been at risk of a Brucella epidemic [Reference Zhu89]. The sudden increase in cases cannot be attributed to improved surveillance [Reference Pappas82], as low levels of brucellosis were detected in high-risk individuals [Reference Lin90].

Timely and accurate reporting/Infodemic

The absence of official clinical data from the incident raises concerns about the effectiveness of the response by Chinese authorities [Reference Pappas82]. One study revealed that 96 initially exposed individuals were asymptomatic but seroconverted, without mention of the total patients tested or follow-ups [Reference Li91]. The incident has often been referenced in Chinese publications unrelated to the topic [Reference Zhang92, Reference Chen93]. There were considerable delays in state action, and substandard biosafety and biosecurity regulations remain unresolved [Reference Pappas82].

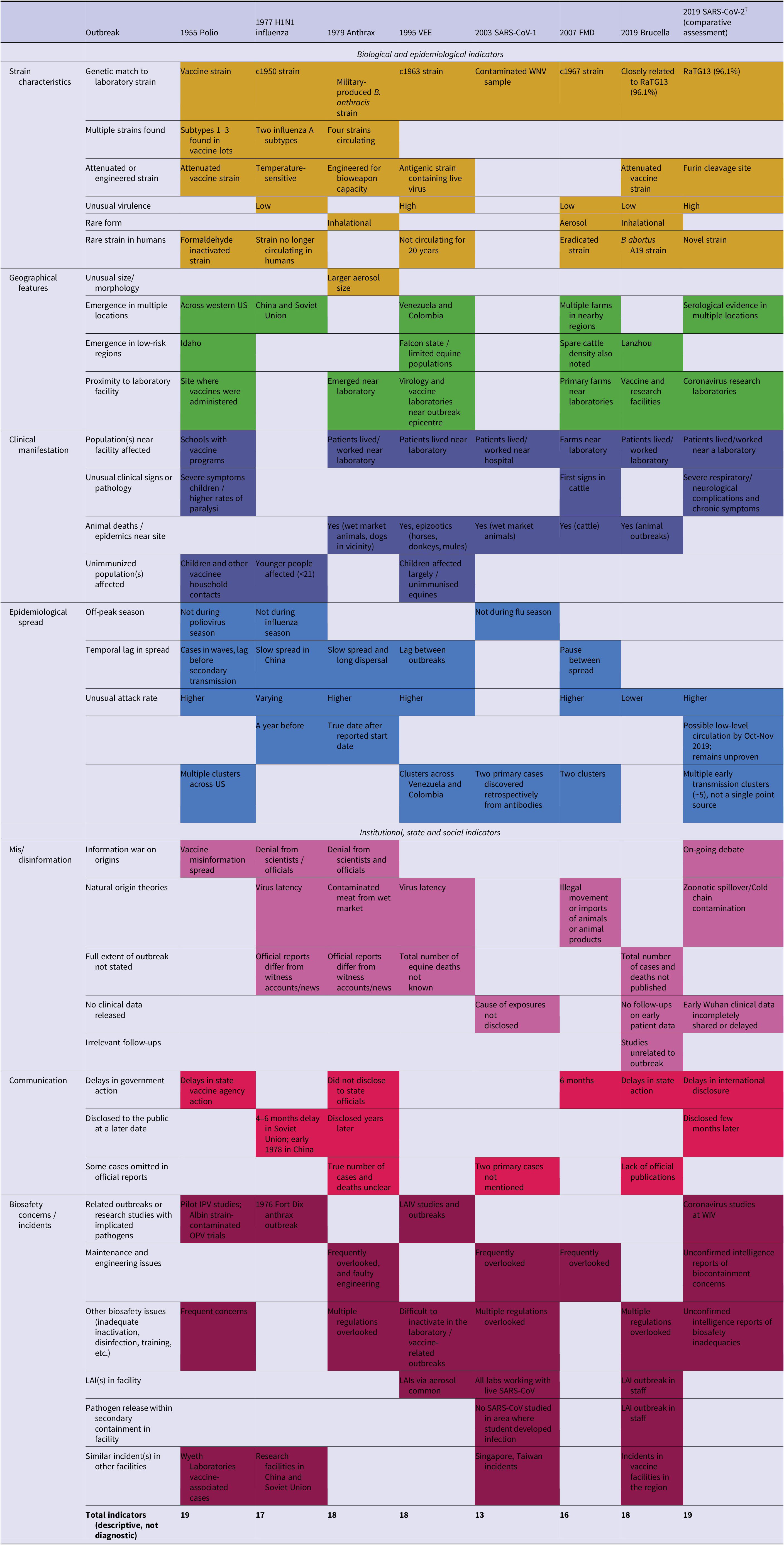

Summary of risk factors across laboratory-associated outbreaks

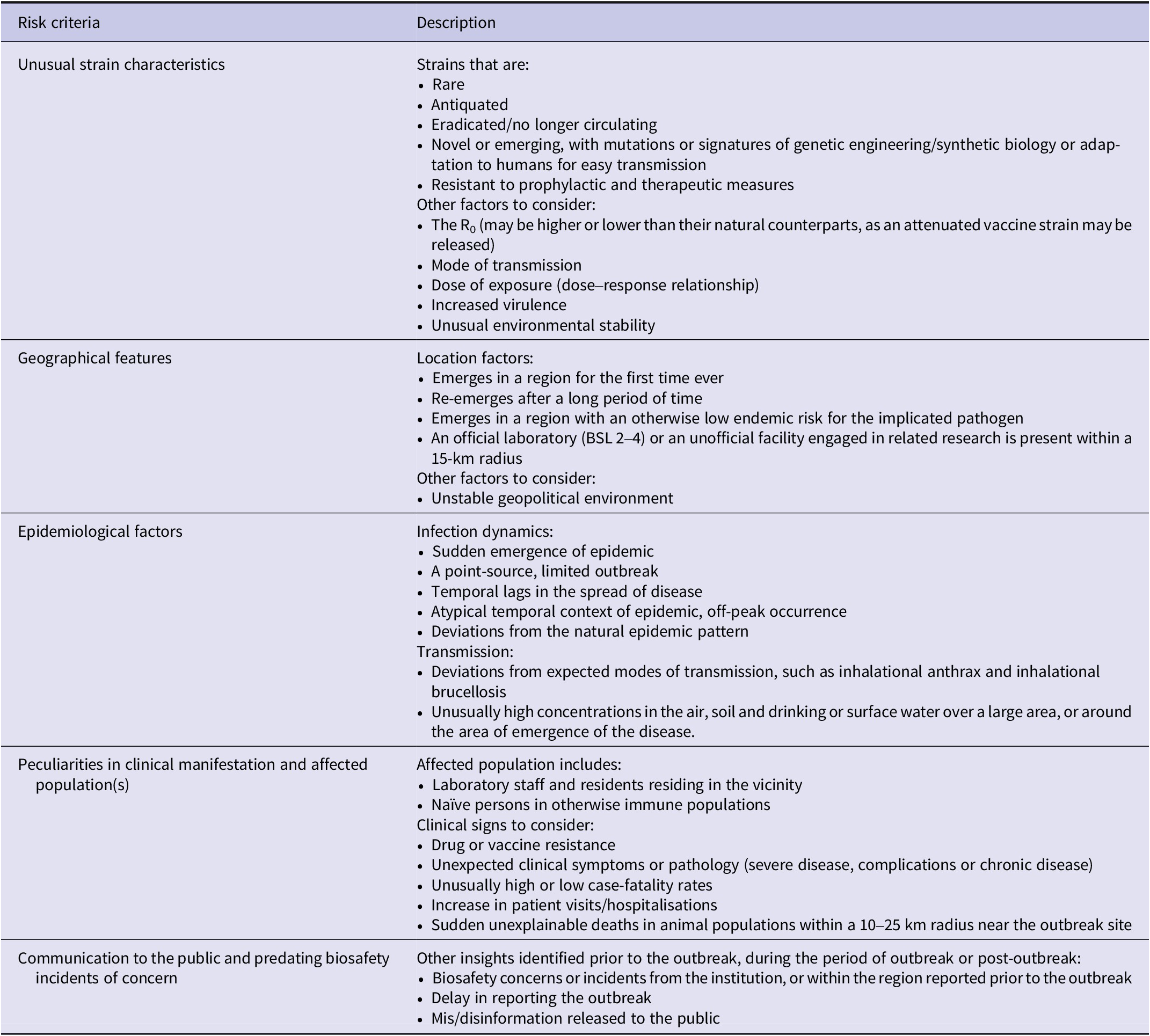

Thematic analysis of the outbreaks identified 19 biological and epidemiological indicators, and 14 institutional, state and social indicators (Table 2). Across the seven outbreaks, the lowest number of indicators (n = 13) was noted in the 2003 SARS escapes, while the highest were observed in the 1955 Cutter Laboratories Polio incident (n = 19) (Supplementary Appendix S2). The number of biological and epidemiological indicators across these outbreaks ranged from 9 to 14, while the institutional state, and social indicators ranged from 3 to 9. The indicators observed across the seven laboratory-associated outbreaks were evaluated to develop risk criteria for flagging possible unnatural origins. The framework consists of five primary criteria, including: unusual strain characteristics, geographical features, epidemiological factors, peculiarities in clinical manifestation and/or affected population(s) and communication to the public and predating biosafety incidents of concern (Table 3).

Table 2. Key themes and indicators observed in confirmed laboratory-associated outbreaks and comparative application to SARS-CoV-2

Note: The listed themes include: strain characteristics (yellow), geographical features (green), clinical manifestation (dark blue), epidemiological factors (blue), mis/disinformation (pink), communication to the public (red) and biosafety concerns/incidents predating the event (purple). †SARS-CoV-2 is included for comparative application of the risk-assessment framework only. Inclusion does not imply confirmation of a laboratory-associated origin.

Table 3. Descriptive risk criteria observed in historically documented accidental laboratory-associated outbreaks

Note: The listed criteria include: unusual strain characteristics, geographical features and distribution, epidemiological factors and spread, peculiarities in clinical manifestation and affected population(s), communication to the public and predating biosafety incidents of concern.

Discussion

The study examined recurring epidemiological, operational and governance features that distinguish laboratory-origin outbreaks from natural ones, drawing on historical cases and applying this analytical framework to the origins of SARS-CoV-2 without implying causality. These events are rarely attributable to a single technical failure, but rather an interplay of immediate laboratory-level breaches and systemic deficiencies in governance, oversight and risk communication.

Consistent indicators emerged across the examined outbreaks. Technical failures, such as inadequate handling and transfer of inactivated pathogens and poor maintenance, underpinned the majority of outbreaks. Sudden, unexplained deaths in animal populations within an area have historically served as sentinels for the release of infectious agents and have preceded human case recognition in outbreaks of Anthrax, VEE, Brucella and FMD (Table 2). This reinforces the value of animal surveillance data for outbreak identification, as most pathogens released intentionally or unintentionally are zoonotic.

Epidemiological, spatial and geographical anomalies were recurrent across outbreaks [Reference Furmanski1], as were atypical strain features [Reference Treadwell94] (Table 2). Importantly, aside from the Anthrax escape, pathogens were often circulating prior to detection, demonstrating fragmented reporting and disease surveillance systems. Certain outbreaks lacked many biological and epidemiological indicators, but institutional/state/social factors pointed to outbreaks of laboratory origin, i.e., the 2003 SARS-CoV-1 escapes and the 2019 Brucella leak. The opposite was also observed in the 2007 Pirbright FMDV leak, the 1955 Cutter Laboratories Polio incident and the 1995 VEE epidemic, where biological and epidemiological indicators were more abundant than institutional and state factors (Supplementary Appendix S2), suggesting that both classes of indicators should be considered when assessing laboratory origins.

While natural or unnatural origin cannot always be conclusively distinguished, such anomalies provide strong signals of possible unnatural origin [Reference MacIntyre7]. The identified indicators were used to develop a framework of risk criteria for identifying such incidents (Table 3).

Using this framework, the emergence of SARS-CoV-2 exhibited several indicators warranting structured assessment. We emphasise that the presence of these indicators does not establish origin and should not be interpreted independently of virological, epidemiological, and institutional investigations. Initial WHO missions in 2020 and 2021 concluded that a laboratory origin was highly improbable. Subsequent evaluations by the WHO Scientific Advisory Group for the Origins of Novel Pathogens (SAGO) reported that zoonotic spillover remains the most supported hypothesis, however a laboratory-associated incident cannot be excluded due to incomplete access to requested information [95]. The earliest recognized cluster occurred in Wuhan, which hosts two major coronavirus research facilities, including the Wuhan Institute of Virology (WIV), where research on SARS-related coronaviruses had been conducted [Reference Ge96, Reference Latinne97]. Several early cases lacked exposure to the Huanan seafood market [Reference Li98]. Although environmental sampling detected SARS-CoV-2 contamination at the market, including in wildlife-associated stalls [Reference Worobey99], these findings could not distinguish between contamination arising from infected animals and introduction by infected humans. [Reference Worobey99]. No intermediate host has been definitively identified to support zoonotic spillover despite extensive sampling. Reports suggesting pre-December 2019 circulation in several countries remain unconfirmed owing to the absence of virus-neutralisation or sequencing data [95]. Clinical anomalies were also present, in particular, unique neuropathological and cardiovascular symptoms were observed in young adults [Reference Chen6, Reference Akhtar100]. Moreover, high rates of presymptomatic and asymptomatic transmission were seen in SARS-CoV-2 patients in comparison to the 2002–3 SARS-CoV-1 outbreak, where asymptomatic infection was rare. SARS-CoV-2 achieved effective dissemination due to its widespread asymptomatic carriage in the population leading to undetected community spread.

Genomic features attracting scientific interest include the presence of a furin cleavage site not observed in the closest known sarbecovirus [Reference Coutard101], early markers of high virulence [Reference McLean102] and rapid adaptation to human transmission [Reference Piplani103]. Although unusual, current analyses demonstrate that these features can arise through natural evolutionary mechanisms. The modified Grunow–Finke tool produced scores consistent with an unintentional laboratory-related event [Reference Chen6]. However, these tools rely on incomplete datasets and assumptions and cannot substitute for direct virological or epidemiological evidence. Consistent with our risk criteria, recurrent themes included unconfirmed biosafety concerns, uncertainties in early transmission dynamics, marked clinical impact, genomic features of interest and multiple early clusters. Although an accidental laboratory origin of SARS CoV-2 has been suggested, no direct evidence supports this scenario, and many experts continue to view natural zoonotic spillover as the more likely pathway. A definitive resolution will require access to the missing data and continued investigation.

All events detailed here were shaped by systemic weaknesses. Fragmented legislation, inadequate oversight and poor governance allowed breaches to go unreported. Unlike animal health systems, international frameworks such as the IHR lack standardized implementation of guidelines for human outbreak reporting. Risk communication failures, whether through delay, omission or disinformation, were a persistent feature undermining public trust and hindering containment efforts.

These findings demonstrate that laboratory-origin outbreaks share a recognizable epidemiological and operational fingerprint, which, paired with systemic governance insights, can strengthen outbreak surveillance. Prevention demands a shift from reliance on technical safeguards to a systems-based approach, with cooperative governance, integrated One Health surveillance, transparent data sharing and proactive risk communication. By embedding biosafety into these broader systems, accidental releases can become rare exceptions rather than recurrent events.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at http://doi.org/10.1017/S0950268825100915.

Data availability statement

No primary data was collected for this review. All original source data are available from the cited publications. Data extracted from published studies are presented in the supplementary materials.

Author contribution

Sandhya Dhawan: Conceptualisation; Methodology; Data curation; Formal analysis; Investigation; Visualisation; Writing – original draft.Wirichada Pan-ngum: Methodology; Formal analysis; Validation; Writing – review & editing. Chandini Raina MacIntyre: Conceptualisation; Interpretation of results; Writing – review & editing. Stuart D. Blacksell: Conceptualisation; Supervision; Project administration; Writing – review & editing.

Funding statement

This research was funded in part by the Wellcome Trust [220211/Z/20/Z]. For the purpose of Open Access, the author has applied a CC BY public copyright licence to any Author Accepted Manuscript version arising from this submission.

Competing interests

Stuart D. Blacksell was a member of the WHO Scientific Advisory Group for the Origins of Novel Pathogens from November 2021 to August 2025.