Doctors historically commanded mental health services, for example as medical superintendents of asylums. Since the inception of the National Health Service (NHS) in 1948 and its full absorption of mental health services following the dissolution of the board of control in 1961, community and primary care services have grown and flourished (along with demand) and technological interventions have become more costly within finite resources. There has therefore been a need for administration and management from people with broader business skills than doctors.

NHS reforms

The Griffiths Report (Department of Health and Social Security 1984) brought in general management, and further reforms followed the White Paper Working for Patients (Department of Health 1989), in which free-standing NHS trusts were introduced. Each trust was to be overseen by a board, whose constitution had to include a chief executive officer and a director of finance (who, in turn, had to be a Consultative Committee of Accountancy Bodies (CCAB) qualified accountant). The board, as well as including a chair and other non-executive directors, had a statutory requirement to include a registered medical practitioner (invariably the medical director) and a registered nurse (invariably the nursing director). In our opinion, this was an important requirement for the following reasons.

The need for informed leadership

First, the two professions generally regarded as being of primacy at the time (medicine and nursing) required leadership from individuals who shared the defined body of knowledge and expertise associated with those professions and who were therefore generally held to know what their members were supposed to be doing and how they were supposed to be doing it. The exclusion of direct professional representation of psychologists, social workers and allied health professionals at board level may have reflected the traditional values of a healthcare model (but this of course will have adapted over the years as the status of these professions has gained ground on the others).

The need for line management

Second, whether they liked it or not, members of both professions required some sort of line management and this was seen as a way of circumnavigating the mystique arising from exclusive expertise. This role within clinical practice has grown considerably following a number of public inquiries, such as that into cardiothoracic services in Bristol (Secretary of State for Health 2001) among others.

Realistic expectations

Third, non-clinical managers needed to understand the realities of healthcare provision at the front line so that they did not drive performance in such a way as to render their expectations of clinicians unattainable. This extended to boards needing to assure themselves that their strategies were going to be consistent with what clinicians felt should be on offer to enable ownership and delivery at the front line.

Appropriate accountability

Finally, most doctors feel that, in pursuing their patients' welfare, they should be accountable only to another clinician from the same – or a similar – profession. Alternatively, accountability might rest with the most senior person in the managerial hierarchy (the chief executive), to whom the medical and nursing directors are themselves accountable.

The ethos of medical directorship

The medical director is seen as one of the most important guardians of clinical probity at board level. This means that the role aims to ensure that the board and its executive take decisions that are always either directly or indirectly aimed at improving patients' experiences of healthcare and that the ethos and values of clinical professionalism are imbued within the culture of the trust.

These values are based on the overriding principle that clinicians do no harm and make the care of the patient their first concern. There are, of course, a number of more specific examples of how this can be done, as set out in the General Medical Council's Good Medical Practice (2006) (Box 1).

BOX 1 Good Medical Practice guidelines for clinicians

-

• Make the care of your patient your first concern

-

• Protect and promote the health of patients and the public

-

• Provide a good standard of practice and care

Keep your professional knowledge and skills up to date

Recognise and work within the limits of your competence

Work with colleagues in the ways that best serve patients' interests

-

• Treat patients as individuals and respect their dignity

-

• Treat patients politely and considerately Respect patients' right to confidentiality

-

• Work in partnership with patients

Listen to patients and respond to their concerns and preferences

Give patients the information they want or need in a way they can understand

Respect patients' right to reach decisions with you about their treatment and care

Support patients in caring for themselves to improve and maintain their health

-

• Be honest and open and act with integrity

Act without delay if you have good reason to believe that you or a colleague may be putting patients at risk

Never discriminate unfairly against patients or colleagues

Never abuse your patients' trust in you or the public's trust in the profession.

Although these values ostensibly relate to patient care, it would be our submission that most, if not all, can just as easily relate to the modus operandi of an NHS trust board, substituting the word ‘staff’ for ‘patients’ in some of the specifics. It is also important to remember that the primary role of a board is virtually identical to the first principle of governance, which is to create an environment in which learning and excellence can flourish.

Thus, patient-centred care and choice (clinical concepts) relate to consultation (a management concept). Similarly, honesty and trustworthiness in clinical endeavours relate to diligence and integrity in financial fields. Non-prejudicial behaviour translates to equitability and treating patients considerately cross-refers to an approach to the development of a workforce that feels valued, understood, supported and safe.

However, it is no longer the case that these ethical and moral duties are the sole preserve of the medical director – the seven ‘Nolan principles of public life’ (Box 2), for instance, apply to all board directors.

BOX 2 Nolan principles of public life (applicable to all members of NHS trust boards)

-

• Selflessness Holders of public office should act solely in terms of the public interest. They should not do so to gain financial or other benefits for themselves, their family or their friends

-

• Integrity Holders of public office should not place themselves under any financial or other obligation to outside individuals or organisations that might seek to influence them in the performance of their official duties

-

• Objectivity In carrying out public business, including making public appointments, awarding contracts or recommending individuals for rewards and benefits, holders of public office should make choices on merit

-

• Accountability Holders of public office are accountable for their decisions and actions to the public and must submit themselves to whatever scrutiny is appropriate to their office

-

• Openness Holders of public office should be as open as possible about all the decisions and actions that they take. They should give reasons for their decisions and restrict information only when the wider public interest clearly demands

-

• Honesty Holders of public office have a duty to declare any private interests relating to their public duties and to take steps to resolve any conflicts arising in a way that protects the public interest

-

• Leadership Holders of public office should promote and support these principles by leadership and example

The changing face of healthcare management

Learning from business

The necessity to deploy humanistic concepts of this nature to the management of organisations is hardly the reserve of healthcare. Indeed, the biggest three advances in business over the past decade or two have been in information technology, internationalism and the development of skills that encourage the management of a workforce comprising people as opposed to ‘human resources’. The NHS has much to learn from the private sector in this respect and it must be a central role for clinicians in senior NHS management to ensure that these values become imbued in the ethos and culture of the executive team and wider board.

Why should this be important? Shouldn't care delivery be a relatively simple matter of taking on appropriately trained and experienced professionals and enabling them to get on with their jobs so that compliance with key performance indicators can be achieved and both clinical and corporate governance demonstrated?

Herein lies the importance of distinguishing between what one does and how one does it. The former may well be a relatively straightforward matter, but it is the latter that brings credibility to a patient's experience of healthcare, affects the reaction of a workforce to change and therefore dictates the likely success of the management of that change.

Style and tone are essential elements of successful interpersonal transactions – both on an individual basis and at a corporate level. They are important because they say something about one that other people can relate to, approve of and cooperate with or, failing that, at least grudgingly respect. And it is here that setting an example can be so powerful. If patient perceives a doctor's efforts as genuinely motivated by a wish to help and assist them, they are likely to concord and cooperate with the plan of action and a therapeutic alliance (crucial to a good outcome) can be established. Likewise, if senior management is perceived by the workforce as adopting humanistic principles, their attitude will be positively influenced and better relationships will be built between colleagues and managers.

Learning from feedback

This is reflected in a number of initiatives that ask patients and staff what their experience has been. For instance, 360 degree appraisal of medical staff invites patients' comments on their interpersonal and professional manner and both patient and staff surveys are typically part of the repertoire of key performance indicators for NHS trusts prescribed by central government. This reflects a very healthy understanding within the Department of Health that the experience of both patients and staff says a lot about how well an NHS trust is being run.

Core contributions and added value

The core contributions of a medical director – or any other board member for that matter – might usefully be extrapolated from those required by Monitor (2007) of a chief executive officer of a foundation trust (Box 3); for a brief explanation of NHS foundation trusts see Department of Health 2005a.

BOX 3 Monitor's requirements of a chief executive officer of a foundation trust

Organisational capacity

-

• Maintain the highest standards of conduct and personal integrity within the trust

-

• Accept accountability for compliance with best practice, statutory and regulatory requirements in all matters, including financial, governance, legal and clinical related issues

-

• Understand the legal position in relation to all key aspects of the business, financial assets, people, IT and intellectual property

-

• Ensure that health and safety policies and procedures reflect current best practice and are disseminated effectively to all staff

-

• Promote effective joint working with external stakeholders and key partners towards achievement of the trust's objectives

Communications and relationships

-

• Develop and maintain a strong sense of accountability to stakeholders through the trust

-

• Establish effective working relationships with key agencies and current and potential partners at national, regional, subregional and local levels

-

• Promote and maintain harmonious and productive working relationships with the recognised trade unions, professional bodies and staff representatives

-

• Promote public understanding of the trust's values, objectives, policies and services

Strategy

-

• Work with board members in developing and promoting the trust's vision, values, aims and strategic objectives

-

• Review and evaluate present and future opportunities, threats and risks in the external environment and current and future strengths, weaknesses and risks to the trust

-

• Challenge conventional approaches and welcome and drive forward change when needed

-

• Understand, assess and manage strategic, reputational and operational risk

-

• Produce, review and revise the company's business plan to ensure that it is geared to achieving the trust's vision and strategy, including developing the trust

Workforce development

-

• Motivate and influence other board members and members of the trust's management team

-

• Determine when to change and when to consolidate, understand the impact of change on people and manage it with sensitivity

-

• Develop effective working relationships and communications with staff and ensure that staff are motivated, supported and respected

-

• Act as a driver for equality and diversity, both as an employer and provider of services, ensuring that effective policies and procedures are in place and promoted

Operations

-

• Draw the board's attention to matters it should consider and decide upon, ensuring proper attention is given to them

-

• Ensure that the board is given the advice and information necessary to perform its duties and that your contribution to the board enables it to conduct its business properly

-

• Understand performance management and focus on continuous improvement in the delivery of services whilst maintaining close relationships with relevant regulatory bodies

(From Monitor 2007, reproduced with permission)

Added value from directors

If these represent in some way the core concerns of a board director, one may then invoke the concept of ‘added value’ from each individual director's post. This can be drawn from their specialist expertise (either in a clinical or a managerial sense) or from their personal skills (for example, charisma or emotional intelligence). This explains why board level positions are rarely described in detail – the object of the exercise is to create a team of people meeting certain fundamental requirements (as detailed above) whose interpersonal skills and personalities interact to add overall value through team synergy, but whose individual experience and expertise adds specific value in the form of specialist know-how and effective challenge.

Defining added value

Defining the added value brought by a medical director is not easy and may well vary from one individual to another or from one organisation to another. However, most employers would express it as board accountability for a number of specific areas of organisational functioning (Box 4).

BOX 4 Typical organisational responsibilities of a medical director

-

• Overseeing the quality and improvement of clinical services

-

• Clinical governance (usually a shared role with the director of nursing)

-

• Clinical market development and opportunities

-

• Research and development (strategy, operations and governance)

-

• Professional postgraduate education and accreditation for doctors

-

• Mental Health Act legislation

-

• Standards of professional practice (including appraisal and regulation)

-

• Medicines management

-

• Implementation of National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) guidelines

-

• Confidentiality and clinical information (part of which is, of course, the Caldicott guardian function)

-

• The oversight and regulation of clinical interventions

-

• Outcomes evaluation

-

• Strategic management of the medical workforce

Parts of the inventory may not look familiar, even to readers who are medical directors themselves, as the allocation of specific functions varies so much across organisations depending on the skills distribution within the executive team. In N.D.'s case, for example, board accountability in a previous role extended to other areas within his sphere of competency and interest (such as psychological therapies and spiritual care). Other medical directors are known to have specific roles regarding productivity, designing clinical systems, modernisation and so on, taking them well outside any generically recognisable job description.

Other responsibilities

Medical directors may also have additional direct managerial roles. It is common to find pharmacists, clinical scientists or members of a clinical governance team managed within the medical directorate, for instance. Medical directors will typically have a team of associate or deputy medical directors, clinical directors or lead consultants sharing medical managerial duties. Hybrid reporting arrangements are not unusual, with professional accountability and line managerial responsibility resting in different places. Such dual arrangements can be difficult to interpret and operate (particularly for those clinicians whose natural inclination is to avoid any sort of control over their activities). However, hybrid reporting essentially reiterates the importance of aligning medical doctors to operational imperatives (with appraisal supporting this) while ensuring that their professional practice is up to scratch – what some might describe as the difference between what one does and how one does it.

That said, direct managerial obligations are not usually a big part of the medical director's role. The focus of the role tends to rest on the seniority of the post holder and how the organisation can get the best value from that. This tends to be expressed through the slightly more complicated concept of ‘leadership’.

Leadership

One of the most important qualities that a medical director is expected to bring to both their board and their organisation is leadership. This is based, at least partly, on the expectation that a doctor, in having broad experience in managing complex clinical cases where the leadership of a multi-professional team of individuals will have been a vital component of a successful outcome, can bring these leadership skills to bear in the role of senior manager.

Competency frameworks

Leadership is a highly sophisticated concept. The NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement, for instance, has published a medical leadership qualities framework, endorsed by the Academy of Medical Royal Colleges (NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement 2009). It describes competency sets at both postgraduate and post-registration level, where personal qualities such as self-belief, self-awareness, self-management, ambition and integrity increasingly drive direction-setting and service delivery as the leader grows in experience and seniority.

The Royal College of Psychiatrists' own Education and Training Centre (the CETC) has produced a leadership development programme that draws from the core curriculum and the expectation implicit in New Ways of Working (Department of Health 2005b) that consultant psychiatrists will undertake a clinical leadership role (of a multidisciplinary team) as a vital part of their added value to mental health services. The NHS Confederation is working with a group of medical managers in mental health to describe how mental health trusts can assess themselves in respect of the degree to which they provide a culture for the development and sustenance of leadership among senior clinicians. The British Association of Medical Managers (BAMM) has developed a competency framework for medical directors, detailing a professional development programme of hierarchical knowledge systems relating to communication, developing people, developing business, developing the self, the wider contexts and quality (www.bamm.co.uk). This has been created in consultation with BAMM's Medical Leaders Professional Council (which included, among others, medical leaders at a national and local level, Presidents of medical Royal Colleges, and leaders at the BMA, GMC and Department of Health) and is possibly the closest one can currently get to a formal description of the managerial competency set for a medical director.

The bigger picture

Thus far, we have discussed the potential contributions of medical directors to unitary organisations. There are, however, substantial contributions that medical directors can make in positioning their organisation in the local health economy, the region and in some cases across the country. These derive largely from the medical directors' ability to use the same language as colleagues in primary care, public health and acute hospitals to hold constructive conversations about how interrelationships and interfaces could and should work.

There are, of course, national agendas driving a number of the issues already described and it is important that the medical director is abreast of developments, especially the coming competitive market, so as to anticipate and offer developments ahead of competitors. There is a balance to be struck here between the greater good (consistent excellence across the NHS with no inequalities) and the competitive advantage. A medical director with an understanding of the potential for mental health services development can afford their organisation a considerable edge by enabling and encouraging knowledge transfer and forward thinking. There are also advantages to be gained from networking nationally (and internationally) to get a better feel for successful research and service development. However, we would warn medical directors that problems can arise out of a conflict between the contribution to wider learning on the one hand and wresting intellectual property for their own organisation's innovations on the other.

Career planning

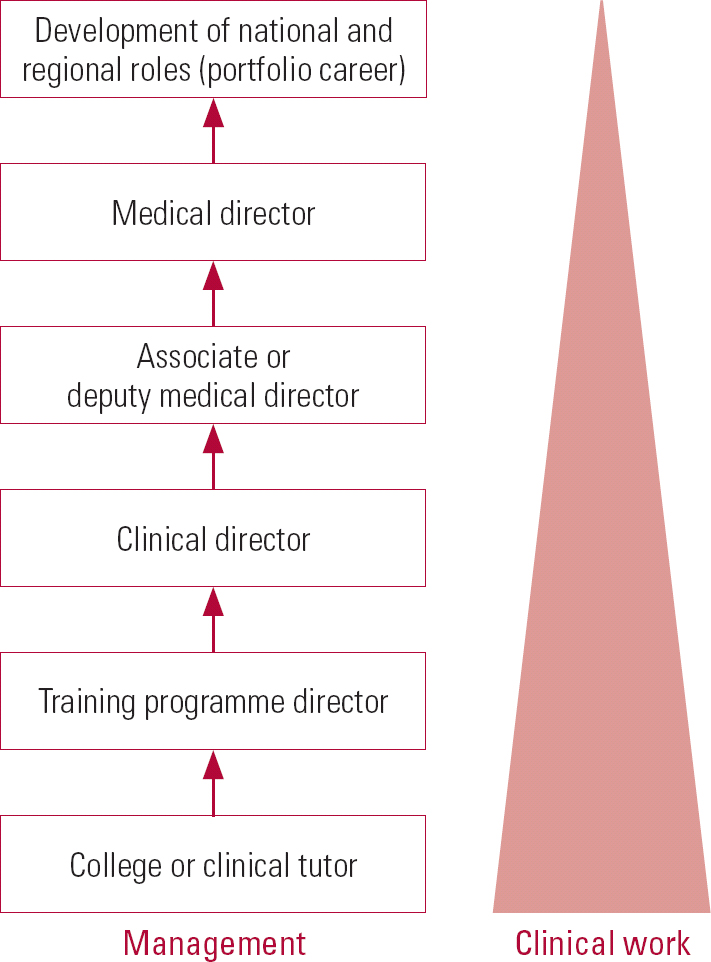

Most trusts now offer a number of opportunities for consultants to get involved in management. A formal continuing professional development (CPD) trajectory for those interested in building management posts into their career is some way off. However, it should be possible because there seems to be a usual-type progression from a college or clinical tutorship, plus or minus programme directorship, or perhaps chairing the medical advisory committee, to assistant or substantive clinical directorship, and then to associate or deputy medical directorship. A typical career pathway is outlined in Fig. 1.

FIG 1 A typical career pathway into medical management.

Career progression issues

Formal development

What is lacking is a stratified professional development programme that equips the interested clinician with the core and added value competencies that they will need for their next career move. Many medical managers are all too familiar with uncomfortably steep learning curves once in post.

Financial issues

A further issue for foundation trusts is how to justify spending consultant pay rates to employ doctors in managerial roles. Some already try to use ‘supporting professional activity’ time in job plans to enable consultants to undertake managerial duties.

Problems arise, however, when the demands of the role exceed this allotment. Furthermore, there are particular issues when senior clinicians are invited to take on important national roles – not least with the Royal College of Psychiatrists. At present, most foundation trusts seem prepared to support the time out as long as they can be assured of a quid pro quo for the trust (such as advanced horizon scanning and reputation enhancement). However, it is likely that regional and national organisations requiring NHS consultant time to enable them to function will need to start thinking about paying for secondments so that their employers can back-fill absences.

Beyond medical directorship

Career progression beyond medical directorship is opaque. The historical approach (doing it for a few years before retirement as the pinnacle of one's career and in so doing invigorating one's pension entitlement) will not work for talented younger medical managers who train earlier for a specific career aim.

Exit strategies need to be developed to ensure that the wealth of experience that some senior medical managers have built up is not wasted during the remainder of their careers.

At present, a majority return to full- or part-time clinical practice after 5 or 6 years in the role, becoming organisational ‘elders’ and providing advice and mentorship to others (including, it is hoped, their successors). A minority wish to extend their activities into regional or national roles, developing what are becoming known as ‘portfolio’ careers where a number of roles and posts are held contemporaneously. Obviously in circumstances such as these, the concept of secondments or ‘time-sharing’ of the psychiatrist becomes critical to the trust's ability to continue to operate clinical services well and efficiently despite losing some of the consultant's time.

An alternative exit strategy would be one of onward career progression – to becoming a deputy chief executive and then a chief executive, for instance. Although the thorny issue of being unable to continue working to a consultant contract while in this sort of office needs to be resolved, there is no reason why a stint of deputy leadership should not be part and parcel of what is expected of a medical director (or any other executive board member, for that matter) during their tenure. This is consistent with the current aspiration of the Department of Health that a majority of chief executive vacancies are competed for by at least one medical consultant.

The future

It is probably the case that foundation trusts will continue to be expected to include a registered medical practitioner on their board of directors. Although it might be that registration alone is seen as adequate, many would argue the importance of a medical director staying in touch with the consequences of their decisions through continued clinical practice (invoking the need to be relicensed). Some advocate recertification as an ongoing requirement, not only because the clinical practice is likely to be in an area of specialisation but also because the implications of successful revalidation in terms of keeping up to date are relevant to the requirements of the medical director role. There is no rule to say that the medical practitioner must be a medical director. This could depend on who else is on the board – if the chief executive officer, or perhaps a non-executive director, is a medic, for example, it could be argued that there is no need for additional medical expertise.

On the other hand, Department of Health philosophy currently places clinicians at the heart of service leadership and reform – the Next Stage Review (Professor the Lord Darzi of Denham 2008) underlines this emphatically – so it would be perfectly possible to argue that a foundation mental health trust should consider having more than one consultant psychiatrist on its board.

Possible directions for the medical director role

Specific roles for medical directors can be predicted to evolve. Senior officer accountabilities are appearing for all sorts of areas where boards require assurance: controlled drugs management, information risk and revalidation, to name but three. Although administration of these areas can and will be delegated – creating potential for experiential training for aspiring medical managers – the board will always require an accountable officer to bring assurance regarding these issues to its table. The question will be whether boards will choose a nurse or a doctor, or continue to have both. It is therefore the foundation trust's understanding of, and belief in, the effectiveness of psychiatrists in attracting and achieving success that will form the basis for the continuation of the medical director function.

Consultant psychiatrists have a training and depth of expertise and experience that transcends that of most other professional groups. However multidisciplinary mental healthcare becomes, complex issues invariably percolate to the consultant in the team. Consultants need to rise to this expectation and challenge, acquiring new skills as part and parcel of the development of their sense of professionalism and the core competency set of their role.

The medical director is inevitably charged with describing and encouraging this process, whether or not this is made explicit, and boards depend, at least for the foreseeable future, on them doing so.

Conclusions

Arrangements for the standardisation of the quality of professional care in the NHS have reached a level that would have been inconceivable 20 years ago. This has been a laudable and necessary development but has risked the introduction of an overly dogmatic approach to professional freedoms, appraisal and accountability. Consultant roles (particularly in psychiatry) are therefore evolving to take on the challenge of leadership under the overall stewardship of the medical director.

Medical directors must engage the consultant body with central and local aims, objectives and strategy by spearheading changes in their own organisations. At the same time they must keep abreast of (and in the best examples ahead of) national and international developments in mental healthcare.

The role of the medical director will continue to entail the core competencies that should reasonably be expected of the holder of an executive position in a large business or foundation trust. However, it must develop to bring specific quanta of knowledge and expertise on which the board will come to increasingly depend to assure itself of sound governance and exemplary performance. It must also evolve to offer particular contributions in respect of the translation of local and national policy considerations into the DNA of organisational and individual thinking and strategy formulation.

MCQs

-

1 NHS trust boards:

-

a have existed in its present form since 1948

-

b must include representatives of all health professions allied to medicine

-

c have no particular need for a clinician in a management role

-

d have overseen standardised levels of professional care since 1948

-

e have a statutory requirement to include a registered medical practitioner and a registered nurse.

-

-

2 Concerning the career pathway:

-

a medical directors must first serve as training programme directors in their trust

-

b the introduction of foundation trusts has increased focus on the cash efficiency of external roles

-

c it is not possible to combine clinical work and medical management work

-

d trusts take a common view of external roles held by senior clinicians and their funding

-

e there are many standard training programmes for aspirant medical directors.

-

-

3 Medical directors:

-

a are usually responsible for quality and improvement in clinical services

-

b all have the same job descriptions

-

c usually have sole responsibility for clinical governance

-

d are not directly accountable to the trust board

-

e find that individual working is more important than team working.

-

-

4 Regarding management and leadership:

-

a leadership is another word for management

-

b clinical directors report solely to medical directors

-

c there are no frameworks or competency sets relating to medical leadership

-

d clinical leadership of the multidisciplinary team is a concept missing from the New Ways of Working guidance

-

e leadership is one of the most important qualities that a medical director brings to the organisation.

-

-

5 Looking to the future:

-

a the role of the medical director is fixed for the foreseeable future

-

b revalidation is a key issue for medical directors

-

c the successful medical director should focus solely on local trust issues

-

d The Department of Health prioritises managers over clinicians when planning service reform

-

e medicines management and controlled drugs are the responsibility of the director of nursing.

-

MCQ answers

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | f | a | f | a | t | a | f | a | f |

| b | f | b | t | b | f | b | f | b | t |

| c | f | c | f | c | f | c | f | c | f |

| d | f | d | f | d | f | d | f | d | f |

| e | t | e | f | e | f | e | t | e | f |

Acknowledgements

We thank Tim Webb, Medical Director, Suffolk Mental Health Partnership NHS Trust, for his comments and amendments to our draft article.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.