Introduction

To tackle the climate crisis, societies must drastically reduce carbon emissions. Governments have a range of policy tools to achieve this goal. Command‐and‐control instruments impose hard regulatory constraints on emission‐intensive production and consumption activities, while market‐ and information‐based ‘new environmental policy instruments’ (NEPIs) incentivise consumers and producers to lower emissions. All these instruments can contribute to the global mitigation of climate change. At the same time, however, they increase prices and lower consumption opportunities for citizens. This makes them politically tricky. Take fuel taxes: Policy makers, economists and international organisations hail the expansion of fuel taxation as an efficient NEPI to tackle the climate crisis (for instance, see The Economist, 2022). Yet the political risks are considerable (Schaffer, Reference Schaffer, Hakelberg and Seelkopf2021; Thalmann, Reference Thalmann2004), as the example of the gilets jaunes, a French populist grassroots movement, demonstrates. The movement emerged in the fall of 2018 to protest a modest increase in fuel taxes, but quickly turned into a major challenge for the government. Political support for fuel taxation is fragile – in France but also elsewhere (Fairbrother et al., Reference Fairbrother, Johansson Sevä and Kulin2019). Does highlighting the climate crisis help to boost support for fuel taxes?

Comparative research suggests that moments of crisis and despair fuel political support for tax hikes: Citizens are willing to pay higher taxes if they think that it contributes to ending the crisis. The joint interest in effective crisis coping mitigates individual resistance to higher costs (Levi, Reference Levi1988; Peacock & Wiseman, Reference Peacock and Wiseman1961). Historically, mass warfare (Dincecco & Prado, Reference Dincecco and Prado2012; Queralt, Reference Queralt2019; Scheve & Stasavage, Reference Scheve and Stasavage2016; Tilly, Reference Tilly1990) and economic crises (Gillitzer, Reference Gillitzer2017; Limberg & Seelkopf, Reference Limberg and Seelkopf2022) were strongly associated with the introduction and expansion of progressive income taxes during the first half of the twentieth century and with the spread of general sales taxes and the VAT during the second half. By highlighting the link to the climate crisis, fuel taxation could potentially benefit from a similar crisis effect: As people come to see fuel taxation as a (partial) contribution to climate mitigation, they support it more.

Many observers doubt, however, that the climate crisis will substantially reduce tax resistance. In a nutshell, they argue that wars and recessions trigger immediate and pressing spending needs that can justify an increase of the tax burden in citizens' minds. The repercussions of the climate crisis, by contrast, lie mostly in the future and are of uncertain size. Mitigating future climate risks requires preventive taxation today. The temporal gap to future benefits induces policy myopia (Bechtel & Mannino, Reference Bechtel and Mannino2023; Healy & Malhotra, Reference Healy and Malhotra2009; Nair & Howlett, Reference Nair and Howlett2017): People are reluctant to raise fuel taxes because they prefer present consumption over protection from projected but essentially unknown future damage. Hence, the climate crisis is unlikely to significantly increase support for fuel tax hikes, at least until it is too late, and irreparable climate damage is upon us. This allegedly is the difference between the climate crisis and other, more immediate crises.

In this article, we build on the work on policy myopia to propose an alternative explanation for the muted crisis effect of climate change on fuel taxation: Policy distraction. According to this view, the climate crisis is not so different from other crises. People are not myopic about it per se and are aware of the damage climate change may bring. They may even have had first‐hand experience with floods, droughts, wildfires, heat waves and other extreme weather events, suggesting that the climate crisis is not in the future but now. In principle, therefore, citizens may support higher fuel taxes for the same reason they also support emergency tax hikes in response to other crises: They serve an obvious and salient policy requirement. In practice, however, citizens are often distracted by concurrent events that also require policy attention (Djerf‐Pierre, Reference Djerf‐Pierre2012; Hilgartner & Bosk, Reference Hilgartner and Bosk1988; Peng & Zhu, Reference Peng and Zhu2022). Wars, recessions, pandemics, currency crises and other critical events distract from climate issues and weaken crisis‐induced support for costly climate action. This does not mean that people do not take the climate crisis seriously, but that the alarm about climate change is at constant risk of being crowded out by the alarm about other issues (Seabrooke & Tsingou, Reference Seabrooke and Tsingou2019). Worry is simply a ‘finite resource’ (Weber, Reference Weber2006). In this perspective, the crucial obstacle to boosting political support for fuel taxation is not lack of foresight but lack of focus: Distraction rather than weakness of will.

To test our argument, we embed a priming experiment in a large‐scale, representative European survey that was fielded in April 2022.Footnote 1 The survey covers more than 21,000 respondents in 17 countries and was run by the survey company YouGov. In the experiment, we used randomised treatments to prime respondents on the climate crisis, its long and uncertain time horizon and on other concurrent crisis events: COVID‐19 and the Russian war in Ukraine. We then asked respondents about their preferences towards taxes on fossil fuels. In line with existing research (Lakoff Reference Lakoff2010; Mossler et al. Reference Mossler, Bostrom, Kelly, Crosman and Moy2017; Lockwood Reference Lockwood2011; but see Bernauer & McGrath Reference Bernauer and McGrath2016), our results show that a simple climate crisis prime is effective. On average, respondents are almost 12 percentage points more likely to support fuel taxes than in the control setting. This tips public opinion towards net support for fuel taxes. Crucially, policy myopia does not fundamentally undermine this effect. Stressing the long time horizon and unclear extent of the climate crisis only slightly reduces the effect of the climate crisis prime. Compared to the baseline, the effect remains positive and substantial. Reminding respondents of COVID‐19 or the Russian war in Ukraine, by contrast, strongly and significantly reduces the effect of the climate crisis prime and causes support for fuel taxes to decline almost back to baseline. These results demonstrate that the climate crisis has the general potential to boost support for fuel taxes; that policy myopia reduces this effect only mildly; and that a much larger problem is policy distraction by concurrent events.

Our contribution is threefold. First, we show that the climate crisis is less special than often assumed. It has the potential to significantly increase citizen support for higher taxes as do other historically momentous policy challenges such as wars and major recessions. This finding adds to the literature on the drivers of tax policy making (Genschel & Seelkopf, Reference Genschel and Seelkopf2022; Kiser & Karceski, Reference Kiser and Karceski2017) as well as to recent work on climate crisis exposure and environmental policy attitudes (Birch, Reference Birch2023; Demski et al., Reference Demski, Capstick, Pidgeon, Sposato and Spence2017; Poortinga et al., Reference Poortinga, Whitmarsh, Steg, Böhm and Fisher2019; Uba et al., Reference Uba, Lavizzari and Portos2023).

Second, we demonstrate that mere myopia is not the only obstacle to boosting citizen's support for fuel taxation. While time discounting and uncertainty may reduce approval, so may limited attention and policy distraction. We show that prompting the occurrence of other crisis events alongside the climate crisis all but neutralises the positive effect of the climate crisis prime. This is regardless of the nature of the competing challenge (e.g., COVID‐19 or the Russian attack on Ukraine). Importantly, this finding helps to understand why support for fuel taxation is so low in general despite the climate crisis. In the baseline, the climate crisis is at constant competition with other crises for a ‘finite capacity for worry’ (Weber, Reference Weber2010), which reduces attention to climate issues and erodes support for costly climate policies such as fuel taxation.

Third, our study contributes to existing research on the impact of crises on environmental policy attitudes. Although most of this work has focused on the effect of COVID‐19, the results have been mixed. Observational studies suggest that citizens have deprioritised environmental protection due to the pandemic (Beiser‐McGrath, Reference Beiser‐McGrath2022), but experimental studies have not found a negative effect on environmental preferences (Bergquist et al., Reference Bergquist, Roche, Lachapelle, Mildenberger and Harrison2023). By conducting a priming experiment across a broader set of European countries, we provide experimental evidence that supports the findings of observational studies. Specifically, we show that a combined Climate and COVID‐19 prime has a significantly lower effect on support for fuel taxation than the Climate prime on its own.

In the next section, we review the literature on support for green taxation and develop hypotheses about the effects of the climate crisis, policy myopia and policy distraction. Then, we describe our experimental setup, present our results and perform various robustness checks. The final section summarises our findings and discusses theoretical and policy implications.

Support for fuel taxation

Fuel taxes are the textbook example of Pigovian taxes: They increase welfare by incentivising economic agents to internalise the negative externalities of their polluting behaviour (Mankiw, Reference Mankiw2020; Pigou, Reference Pigou1920). By increasing the price of fossil fuel, they lead polluters to change behaviour, reduce emissions and switch to green alternatives.

Fuel taxes are widely praised as powerful tools to combat the climate crisis. Economists, climate scientists and international organisations hail them as efficient means to lower emissions (OECD, 2021; The Economist, 2022). At the same time, fuel taxes generate much‐needed revenue to foster green investment. Yet, no matter how strong the technocratic case for fuel taxes may be, governments still struggle to increase them because public support is generally low (Maestre‐Andrés et al., Reference Maestre‐Andrés, Drews and van den Bergh2019). In France, a modest increase of taxes on diesel and petrol in 2018 was met with strong resistance and a political backlash from the gilets jaunes movement. Similar protests as reactions to fuel tax hikes happened in other OECD countries (Martin & Gabay, Reference Martin and Gabay2018). Since popular demand is a crucial driver of policy change (Caughey et al., Reference Caughey, O'grady and Warshaw2019), lack of demand for fossil fuel taxation puts a serious constraint on governments. How can public support be stimulated?

What drives support for fuel taxes?

To explain preferences for green taxes, extant work has focused on the impact of tax policy design. Three design aspects stand out: Regressivity, intertemporality and internationality.

First, one possible reason for low popular support for fuel taxes is their regressive character (Schaffer, Reference Schaffer, Hakelberg and Seelkopf2021). Regressive taxes on consumption, like fuel taxes, tend to be less popular than progressive ones (Bremer & Bürgisser, Reference Bremer and Bürgisser2023). In other words, the distributional implications of fuel taxation lead to lower support. One prominent proposal to increase support is to earmark revenues from fuel taxes for immediate redistribution to citizens through lumpsum payments. An impressive body of research has found that this so‐called revenue recycling can indeed raise the popularity of green taxes (Beiser‐McGrath & Bernauer, Reference Beiser‐McGrath and Bernauer2019; Carattini et al., Reference Carattini, Levin and Tavoni2019; Jagers et al., Reference Jagers, Martinsson and Matti2019; Nowlin et al., Reference Nowlin, Gupta and Ripberger2020). Still ‘revenue recycling is not a silver bullet’ (Beiser‐McGrath & Bernauer, Reference Beiser‐McGrath and Bernauer2019, p. 5).Footnote 2

Second, several studies have investigated whether the timing of tax hikes makes a difference to support. Does ramping up green taxes gradually rather than levying them at a constant rate reduce popular resistance? Bechtel et al. (Reference Bechtel, Scheve and van Lieshout2020) find that increasing cost paths are even less popular than constant carbon pricing. Looking at firm preferences, Genovese and Tvinnereim (Reference Genovese and Tvinnereim2019) find that low initial stringency of the European Trading Scheme helped to increase support among high‐emission firms. However, support dropped as stringency increased.

Finally, some studies have found that international coordination helps to boost support (Beiser‐McGrath & Bernauer, Reference Beiser‐McGrath and Bernauer2022; Bechtel et al., Reference Bechtel, Scheve and Lieshout2022; Carattini et al., Reference Carattini, Levin and Tavoni2019). However, it remains an open question how to achieve binding agreements on tax coordination in the first place (Keohane & Victor, Reference Keohane and Victor2016; Olson, Reference Olson1965). In sum, it is doubtful whether tax design alone will succeed in tipping public opinion in favour of higher fuel taxes.

Design problems are, of course, not specific to fuel taxation but common among tax instruments in general. Historical research suggests that the introduction and expansion of now standard fiscal tools such as the income tax or the VAT were often initially blocked on fairness grounds or for practical reasons (Genschel & Seelkopf, Reference Genschel and Seelkopf2022; Kiser & Karceski, Reference Kiser and Karceski2017). The time lag between new tax policy designs making their way onto the agenda and breakthroughs in tax policy reforms was often quite long. Frequently, such breakthroughs were induced by crises such as wars (Dincecco & Prado, Reference Dincecco and Prado2012; Scheve & Stasavage, Reference Scheve and Stasavage2016) or major recessions (Limberg & Seelkopf, Reference Limberg and Seelkopf2022; Papadia & Truchlewski, Reference Papadia, Truchlewski, Genschel and Seelkopf2021). Under the collective shock of these events, mass publics accepted costly tax designs they previously opposed.

How do crises facilitate tax reforms? Crises create a permissive political environment that policy entrepreneurs can exploit for tax increases. When citizens perceive a crisis as a fundamental threat to society, they are more likely to accept policy measures like new taxes or tax hikes that help to combat these challenges. The urgency of a crisis amplifies voices calling for a stronger role of the state. Threats to life, liberty, or wealth enlarge voters' zones of political support. Taxpayers' quasi‐voluntary compliance (Levi, Reference Levi1988) increases. This creates a window of opportunity for policy entrepreneurs (Limberg, Reference Limberg2020; Rehm, Reference Rehm2016; Walter & Emmenegger, Reference Walter and Emmenegger2022).

Crises, policy myopia and policy distraction

Historically, crises have often been crucial factors helping to overcome tax resistance. Can the climate crisis facilitate political mobilisation for fuel taxation in the same way?

There is little doubt among climate scientists that the climate crisis poses a severe threat to social, political and economic order (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, 2022). This suggests that it could indeed boost public support for countermeasures such as fuel taxes. We expect that increasing the salience of the climate crisis and highlighting its link to fuel taxation decreases political resistance: Reminding citizens of the dangers of climate change should boost support, all else equal (for a debate on the effects of climate frames on policy support, see Bernauer & McGrath, Reference Bernauer and McGrath2016; Lakoff, Reference Lakoff2010; Lockwood, Reference Lockwood2011; Mossler et al., Reference Mossler, Bostrom, Kelly, Crosman and Moy2017). Our first hypothesis states:

Climate Hypothesis (H1): Climate change primes increase support for fossil fuel taxation.

Many argue, rightly or wrongly, that the climate crisis has a fundamentally different time horizon than other crises. Wars, recessions and pandemics create an immediate and highly visible demand for remedial policy tools. The need to pay for these tools then induces support for costly tax reforms. The most damaging consequences of the climate crisis, by contrast, will only emerge in the future. Fuel taxes and more general carbon taxes are preventive tools to mitigate negative impacts of the climate crisis in the future, rather than remedial tools to pay for existing damage. The climate crisis might be more of an anticipated rather than a manifest shock. This creates myopia in the policy response (Bechtel & Mannino, Reference Bechtel and Mannino2023; Healy & Malhotra, Reference Healy and Malhotra2009; Jacobs, Reference Jacobs2011).

Policy myopia refers to the time‐inconsistency problems created by the time lag between policy decision and policy benefit. The longer the lag, the greater the risk that support for the decision is eroded by the discounting of its future benefit. For instance, citizens may support the totemic ‘net zero by 2050’ goal in principle but still lack the willpower to accept the sacrifices in the present that are necessary to reach this goal in practice (Frederick et al., Reference Frederick, Loewenstein and O'Donoghue2002; Nair & Howlett, Reference Nair and Howlett2017). Citizens are typically more concerned about limiting costs today (Healy & Malhotra, Reference Healy and Malhotra2009). Insecurity regarding the extent and distribution of future climate costs further weakens the impact of the climate crisis on public support (Nair & Howlett, Reference Nair and Howlett2017). Why pay painful taxes now to avoid some future floods, droughts, or storms that you believe may never happen or may turn out to be less dramatic than anticipated? Climate mitigation is a ‘luxury goods issue’ (Abou‐Chadi & Kayser, Reference Abou‐Chadi and Kayser2017): Nice to have in the long run but not a priority item in the short run. In sum, policy myopia may erode the positive effect of the climate crisis: Reminding citizens of the long time horizon of the crisis should weaken the effect of the crisis. This leaves us with our second hypothesis:

Myopia Hypothesis (H2): Stressing the long time horizon of climate change dampens the positive effect of climate change primes on support for fossil fuel taxation.

However, policy myopia may not be the only and perhaps not even the most important obstacle to higher fuel taxation. Protest movements such as ‘Fridays for Future’ or ‘Extinction Rebellion’ demonstrate the salience of the climate crisis for at least some groups of society and the costs they are willing to incur to avoid it. Perhaps citizens are less myopic than often assumed. Also, there is evidence which suggests that climate change is not a thing of the future but has dramatic effects already today (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, 2022). As many people start to feel the damage from climate change more strongly, short‐term worries about the climate, and hence support for effective policy responses, should rise even among myopic citizens (Baccini & Leemann, Reference Baccini and Leemann2021; Gaikwad et al., Reference Gaikwad, Genovese and Tingley2022). Yet, they do not. Bergquist and Warshaw (Reference Bergquist and Warshaw2019), for instance, find that a warming climate alone does not fundamentally change the public consensus regarding climate concerns. Burns et al. (Reference Burns, Eckersley and Tobin2020) report that the stringency of EU climate policy has weakened over the 2010s despite increasing indications of climate damage in EU member states. In their analysis, the ‘conglomerate of crises’ affecting the EU in recent years – from Eurozone to migration, rule of law, Brexit and new geopolitical challenges – has preoccupied policy makers so that less time and energy was left for fighting climate change (Burns et al., Reference Burns, Eckersley and Tobin2020). This aligns with Beiser‐McGrath's finding that the COVID‐19 crisis has caused British citizens to significantly deprioritise climate change (Beiser‐McGrath, Reference Beiser‐McGrath2022). It also fits with a string of studies demonstrating that external shocks affect personal attitudes towards climate change (Kenny, Reference Kenny2020; Uba et al., Reference Uba, Lavizzari and Portos2023) and slow down the pace of environmental policy making (Fernández‐i Marín et al., Reference Fernández‐i Marín, Hurka, Knill and Steinebach2022; Steinebach & Knill, Reference Steinebach and Knill2017).

Media theories of ‘issue competition’ suggest that public attention is a scarce resource. The number of issues that can gain attention at once is limited. Attention is allocated in a competitive process in which more salient issues crowd out and displace less salient ones (Djerf‐Pierre, Reference Djerf‐Pierre2012; Hilgartner & Bosk, Reference Hilgartner and Bosk1988; Kristensen et al., Reference Kristensen, Green‐Pedersen, Mortensen and Seeberg2023; Peng & Zhu, Reference Peng and Zhu2022; Zhu, Reference Zhu1992). This makes it hard to stay focused on a single issue. Even in the absence of policy myopia, citizens and policy makers may struggle to concentrate on the climate crisis because other critical events such as the Covid‐19 pandemic or the Russian invasion of Ukraine divert attention. Other crises are likely to dampen the effect of the climate crisis on support for fuel taxes because citizens have limited attention spans (Jones & Baumgartner, Reference Jones and Baumgartner2005) and a ‘finite capacity for worry’ (Weber, Reference Weber2010). Bounded rationality makes them vulnerable to distraction. In other words, the salience of the climate crisis – and its potential effect on costly policy measures – is at constant risk of being crowded out by other events. Hence, reminding respondents of concurrent crises should dampen the effect of the climate crisis prime on support for fuel taxation. This leads to our Hypotheses 3 and 4:

Distraction Hypothesis I (H3): Introducing the COVID‐19 pandemic into the climate change context dampens the positive effect of climate change primes on support for fossil fuel taxation.

Distraction Hypothesis II (H4): Introducing Russian military aggression into the climate change context dampens the positive effect of climate change primes on support for fossil fuel taxation.

Experimental design

To test our hypotheses, we conducted a priming experiment with more than 21,000 respondents in 17 European countries. The experiment was embedded in the EUI‐YouGov survey on ‘Solidarity in Europe’. It was fielded in April 2022. Respondents were sampled from YouGov's national online base panels via quota sampling (age, gender and education). The country sample included Bulgaria, Croatia, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Italy, Lithuania, Netherlands, Poland, Romania, Slovakia, Spain, Sweden and the United Kingdom.

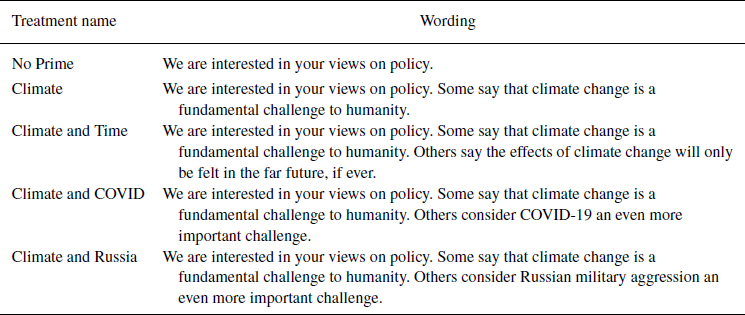

Respondents were randomly assigned to one of four treatment arms or to the control group. Each group was given a short prime. Table 1 shows the exact wordings. The control group received a generic sentence with no prime (‘No Prime'). The first treatment arm received a prime about climate change (‘Climate'). The prime can be seen as a relatively weak treatment given the scientific consensus on the issue. Hence, we perform a relatively hard test for the effect of highlighting the climate crisis. The second treatment tests the myopia hypothesis by stressing climate change as well as the long and insecure time horizon of climate change (‘Climate and Time'). Thus, it stresses both the temporal dimension and ‘impact scepticism’ (Poortinga et al., Reference Poortinga, Whitmarsh and Suffolk2013; Van Rensburg, Reference Rensburg2015) about climate change (‘if ever'). The third group received a prime about climate change and the COVID‐19 crisis (‘Climate and COVID'), and the fourth group was primed on climate change and Russian military aggression (‘Climate and Russia').Footnote 3 We chose these wordings to highlight the existence of other crises vis‐à‐vis the climate crisis in order to test the policy distraction hypotheses. This has two advantages. First, it mirrors real‐world salience trade‐offs. Second, wording the statements about the other crises in relation to the climate crisis rather than independent of one another allows to make the treatments comparable to the myopia treatment.

Table 1. Treatment wording

The treatments were followed by a question on preferences for or against fuel taxation (‘Do you support or oppose fuel taxes (i.e., taxes on fossil fuels for heating, transport and production)?'). Respondents could answer: 1 = Strongly support, 2 = Tend to support, 3 = Neither support nor oppose, 4 = Tend to oppose, 5 = Strongly oppose, and Do not know. While fuel taxes are older taxes with a narrower tax base, carbon taxes are relatively new fiscal instruments with a broader base as they cover all kinds of carbon emitted for the production of goods and services. We asked respondents about their attitudes towards ‘fuel taxation’ rather than ‘carbon taxation’ in general because we expect that people are more likely to connect fuel taxes with tangible costs for themselves, for example, in the form of higher prices at the pump (Fairbrother et al., Reference Fairbrother, Johansson Sevä and Kulin2019). Furthermore, the term ‘carbon taxes’ cues respondents on the climate crisis and obscures the cost implications for individual budgets. We did not elicit preferences prior to our intervention in order to avoid demand effects (de Quidt et al., Reference de Quidt, Haushofer and Roth2018) and problems of consistency bias (Falk & Zimmermann, Reference Falk and Zimmermann2013). Hence, we employed a between subject design.

We perform listwise deletion for all respondents that answered with ‘Do not know’ and dichotomise our main dependent variable so that it takes the value 1 for individuals that support fuel taxes and 0 for those who are indifferent or oppose fuel taxes. We run linear probability models to find out whether our treatments affect attitudes towards fuel taxes. For all models, we set the control group which received no prime as the reference group. We calculate three types of models. First, we only include the main treatments. Second, we add country fixed effects to account for the clustered structure of the data. Third, we run models that include a battery of covariates (gender, age, education level, economic situation, left–right self‐placement, religiosity, urbanity, employment status). Again, we use listwise deletion for missing values of any of the covariates. This left us with the following equation for the model including fixed effects and covariates.

![]() $TaxPref_i$ measures the support of individual

$TaxPref_i$ measures the support of individual

![]() $i$ for fuel taxes.

$i$ for fuel taxes.

![]() $\beta _1$ is the coefficient for the climate change prime. Hence,

$\beta _1$ is the coefficient for the climate change prime. Hence,

![]() $C_i$ is a binary variable that takes the value 1 for the climate change prime and 0 for no prime.

$C_i$ is a binary variable that takes the value 1 for the climate change prime and 0 for no prime.

![]() $CT_i$,

$CT_i$,

![]() $CC_i$ and

$CC_i$ and

![]() $CR_i$ represent binary treatments that turn 1 when individuals have been exposed to further contextualisation of the climate change prime (

$CR_i$ represent binary treatments that turn 1 when individuals have been exposed to further contextualisation of the climate change prime (

![]() $CT_i$ for ‘Climate and Time’,

$CT_i$ for ‘Climate and Time’,

![]() $CC_i$ for ‘Climate and COVID’,

$CC_i$ for ‘Climate and COVID’,

![]() $CR_i$ for ‘Climate and Russia').

$CR_i$ for ‘Climate and Russia').

![]() $\beta _2$,

$\beta _2$,

![]() $\beta _3$ and

$\beta _3$ and

![]() $\beta _4$ denote the coefficients for the respective treatments.

$\beta _4$ denote the coefficients for the respective treatments.

![]() $\bm{Z_i}$ is a vector of socioeconomic control variables and

$\bm{Z_i}$ is a vector of socioeconomic control variables and

![]() $\alpha _$c denotes country fixed effects.

$\alpha _$c denotes country fixed effects.

![]() $\beta _0$ is the intercept and

$\beta _0$ is the intercept and

![]() $\varepsilon _i$ denotes the error term.

$\varepsilon _i$ denotes the error term.

Results

We start by providing simple descriptive information about the distribution of support for fuel taxation across treatment groups. Then we show the results of our regression analyses. Finally, we leverage cross‐country differences to further corroborate our policy distraction model.

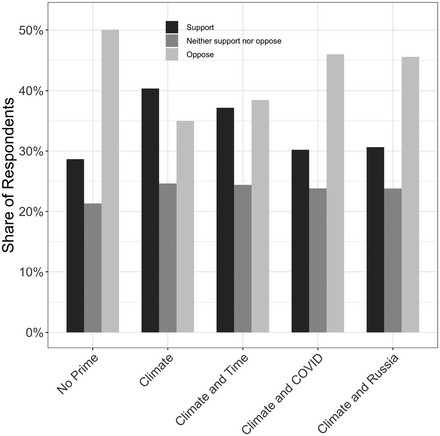

Figure 1 shows the distribution of support, opposition and indifference across treatment arms. Baseline support is low. In the control group (‘No Prime'), only about 28 per cent support taxes on fossil fuels and we see a net opposition to fuel taxation of more than 20 per cent. In fact, we cannot find majority support for taxes on fossil fuels in any of the countries in the sample (Figure B1 in the Appendix of the Supporting Information). Support is substantially higher in the group that received the ‘Climate’ prime. Here, around 40 per cent support taxes on fossil fuels and 35 per cent oppose it. In the group that receives the climate prime plus a statement that the time horizon of climate change may be long and insecure (‘Climate and Time'), support is somewhat lower but still at around 37 per cent. Hence, support remains substantially higher than in the control group. Finally, the ‘Climate and COVID’ and the ‘Climate and Russia’ primes reduce support to roughly 30 per cent and opposition increases to around 45 per cent – almost back to baseline levels.Footnote 4

Figure 1. Support for and opposition against fuel taxation. Share of people who support, oppose, or are indifferent towards fuel taxation. Shares are shown for each treatment arm.

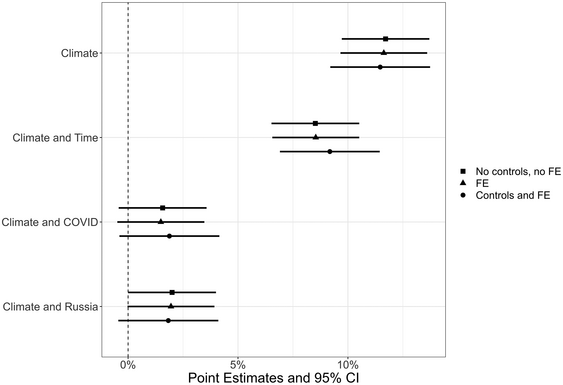

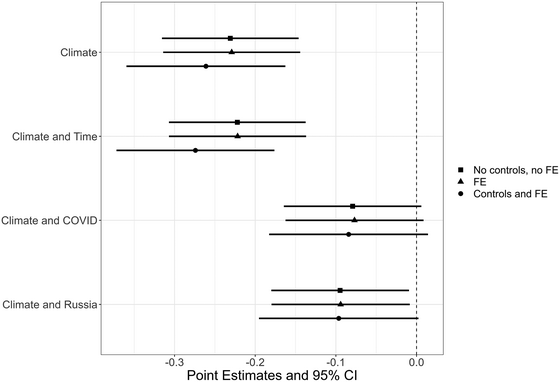

The treatment effects of the different primes reveal a similar pattern. Figure 2 shows the point estimates and 95 per cent confidence intervals for each treatment. We highlight three findings. First, the ‘Climate’ treatment has a substantial and statistically significant effect on support for fuel taxation. The effect size is almost 12 percentage points, providing strong support for the Climate Hypothesis (H1). The large size of the effect may appear surprising in light of previous research suggesting that the impact of simple frames on support for climate change mitigation is limited (Bernauer & McGrath, Reference Bernauer and McGrath2016). Note, however, that our experimental design differs from existing work in that we asked respondents about their attitudes towards ‘fuel taxation’ and not towards mitigation policies semantically linked to climate change, that is, ‘carbon taxes’. In this way, we minimised the extent to which our dependent variable implicitly primes the control group on climate change.

Figure 2. Treatment effects of different primes on support for fuel taxation. All results are based on linear probability models. Table G2 in the Appendix of the Supporting Information shows the full results.

Second, the effect size drops for the ‘Climate and Time’ treatment but remains substantial and statistically significant. Support is up 9 percentage points compared to the control group. Compared to the ‘Climate’ treatment, the ‘Climate and Time’ reduces support by around 3 percentage points and the difference is statistically significant (Figure C9 in the Appendix of the Supporting Information). Thus, stressing the long time‐horizon of climate change dampens the effect of the climate prime (in line with the myopia hypothesis (H2)) but does not erase it. This is particularly striking since the ‘Climate and Time’ treatment highlights not only the long time frame of climate change but also the associated uncertainty and even an ‘impact scepticism’ (Poortinga et al., Reference Poortinga, Whitmarsh and Suffolk2013; Van Rensburg, Reference Rensburg2015) about the size and probability of any damage (‘if ever'). Thus, the treatment provides a strong impetus for myopic respondents to cut support. The fact that support remains relatively high suggests that people are less short‐sighted than standard myopia‐arguments assume, and also do not seem to generally buy into narratives of climate change denial.

Third, the effect of the climate crisis prime almost disappears when mentioning COVID‐19 or the Russian military aggression in addition. The effects are substantially lower and statistically insignificant for the ‘Climate and COVID’ treatment, and substantially lower and borderline significant for the ‘Climate and Russia’ treatment. Compared to the ‘Climate’ prime, support is around 10 percentage points lower, and the difference is statistically highly significant (Figure C9 in the Appendix of the Supporting Information). These findings lend strong support to our argument about policy distraction (Distraction Hypotheses H3 & H4).

Perhaps surprisingly, we do not find much difference between the ‘Climate and COVID’ and the ‘Climate and Russia’ treatments even though they refer to very different policy challenges. In both cases, mentioning additional crises reduces the effect of the climate crisis prime substantially. However, it is also noteworthy to mention that the treatment does not reduce support for fuel taxation. This is particularly interesting given the fact that the Russian invasion had a strong immediate impact on energy prices. This finding suggests that it is the distraction effect of other events rather than their policy characteristics that undermine support for fuel taxation. A vignette experiment conducted post‐treatment reveals that citizens tend to see all three crises – Climate, COVID and Russian invasion of Ukraine – as highly important issues. None of the crises has a clear primacy (see Figure E1 in the Appendix of the Supporting Information).Footnote 5

Our findings remain essentially unchanged when introducing country fixed effects and adding a battery of covariates. Since the inclusion of additional variables implies a substantial increase in missing values, this constitutes a conservative robustness test. We also analyse the balance statistics for treatment assignment to check whether our randomisation strategy was successful (Table G1 in the Appendix of the Supporting Information). We do not detect any major systematic imbalances.

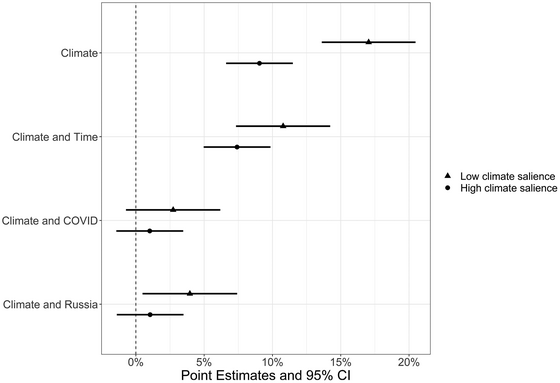

Fourth, we analyse cross‐country differences in treatment effects to further corroborate the policy distraction argument. According to this argument, the salience of the climate issue and making the link to fuel taxation explicit increases policy support. In countries with high overall salience of the climate issue, fuel taxation might already be strongly associated with climate change and the effect would be less effective. In other words, support for fuel taxation should be less malleable in countries where climate change is already a salient as well as politicised topic and where it is more likely to be connected to preference formation for or against fuel taxation. Thus, if our theoretical probes are correct, we would expect that the pre‐existing salience of the climate issue in a given country should moderate the effect of the ‘Climate’ primes.Footnote 6 To test this claim, we use a survey item that asks respondents to list the three most pressing issues facing their country. We calculate the country‐level shares of respondents indicating that the environment and climate is one of these issues (see Table D3 in the Appendix of the Supporting Information). We then use a simple mean split to group countries into a high and a low salience group, and run subgroup effects for each of them.Footnote 7 The results provide strong support for our argument (Figure 3): In countries where the salience of the climate issue is low, the effect of the ‘Climate’ prime is twice as large as in countries where salience is high.

Figure 3. Treatment effects for countries with low and high salience of climate change. All results are based on linear probability models. Table G4 in the Appendix of the Supporting Information shows the full results.

Finally, we make use of an additional post‐treatment survey item which looks at people's preferences regarding the timing of tax reforms. We asked respondents ‘When, if at all, do you think fuel taxes should be raised in your country?’. Respondents could answer: 1 = Today, 2 = Not today, but within the next year, 3 = Longer than a year, up to 3 years time, 4 = Longer than 3 years, up to 6 years time, 5 = Longer than 6 years, up to 9 years time, 6 = Longer than 9 years, up to 12 years time, 7 = Longer than 12 years, up to 15 years time, 8 = Longer than 15 years time, 9 = Never or Do not know. We run ordinal logistic regressions to test for the effect of our treatments on time preferences. Recall that both policy myopia and policy distraction mechanisms expect people to prefer deferred tax reform to immediate reform – because of time discounting (myopia) or because of other salient policy concerns claiming policy attention (distraction). The survey item only appears after the question about support for fuel taxation. The findings look very similar to the main model (Figure 4). The ‘Climate’ treatment increases peoples’ preferences for immediate tax hikes strongly and significantly. Perhaps surprisingly, the ‘Climate and Time’ treatment yields almost the same coefficients. In contrast, the ‘Climate and COVID’ and the ‘Climate and Russia’ treatments bring preferences for deferred fuel tax hikes almost back to baseline levels: Mentioning other current crises drastically reduces the effect of the ‘Climate’ prime on political support for immediate action. Policy distraction rather than policy myopia pushes preferences for fuel tax increases into the future. This finding corroborates our main results.

Figure 4. Treatment effects of different primes on timing of fuel tax hikes. All results are based on ordinal logit models. Table G3 (in the Appendix of the Supporting Information) shows the full results.

Robustness

In this section, we perform a range of additional analyses and robustness checks (see the Appendix of the Supporting Information). We focus on four different aspects: Sensitivity to model specification, demand effects, the role of perceived costs of fuel taxation and heterogeneous treatment effects.

Model specification

We start by checking whether our choice of econometric estimation technique affects our results. Instead of running linear probability models, we use logit models (Figure C1 in the Appendix of the Supporting Information). The results hold. In addition, we run regressions that weigh observations to account for remaining imbalances between the sample and the respective population of a country. Our findings remain robust (Figure C4 in the Appendix of the Supporting Information).

Another modelling choice that might affect the results is the scaling of our dependent variable. In our main model, we recode all answer categories to a binary variable that measures support for taxes on fossil fuels. To check whether the results differ for alternative scaling, we run OLS models where we use all answer categories and recoded them so that they range from 5 = Strongly Support to 1 = Strongly Oppose. Results hold (Figure C2 in the Appendix of the Supporting Information). We also recode our variable into three categories: 1 = Support, 2 = Neither support nor oppose, 3 = Oppose and ran OLS regressions. Again, findings are robust (Figure C3 in the Appendix of the Supporting Information). We also obtain similar results when using ordinal logit regression models instead of OLS (Figures C6 and C7 in the Appendix of the Supporting Information). Furthermore, we check whether our treatments affect the likelihood of respondents answering ‘Do not know’ when asked about their views on fuel taxation. Figure C5 (in the Appendix of the Supporting Information) presents the results. Effect sizes are small (around 1 percentage point) and not robust to adding additional covariates. Our treatments have no clear and statistically significant effect on people choosing the ‘Do not know’ option. However, we do find that people who received any prime are slightly more likely to choose the ‘Neither support nor oppose’, while there are no systematic differences between the different treatment groups (Figure C8 in the Appendix of the Supporting Information).

Demand effects

Demand effects refer to a bias that occurs if participants infer the underlying hypothesis of an experiment and behave in such a way as to confirm it. In general, between‐subject designs as in our experiment are less vulnerable to demand effects (de Quidt et al., Reference de Quidt, Haushofer and Roth2018). Online survey experiments are particularly robust to demand effects as they do not include a direct interaction between researcher and participants (Mummolo & Peterson, Reference Mummolo and Peterson2019). Even if demand effects were elicited by our experiment, they could only account for the general effect of the ‘Climate’ prime, but not for the varying findings regarding the ‘Climate and Time’ and the ‘Climate and COVID/Russia’ primes. Still, it is important to check for the presence of demand effects.

If demand effects were driving the results, we would expect them to vary by respondent. More specifically, demand effects should be stronger for those who share concerns about climate change in the first place. These people should be more likely to adjust their answer regarding fuel tax preferences to align them with the perceived demands of an interviewer. As more leftist people hold particularly strong climate change concerns, we would expect that the treatment effect of the ‘Climate’ prime is substantially larger for them. We test this by looking at the effect of the ‘Climate’ prime and interacting the treatment variable with the respondent's political position.Footnote 8 Our results show little variation of the treatment effects by political position (Table G6 in the Appendix of the Supporting Information). Thus, demand effects are unlikely to drive our results.

Perception of costs

Our argument about policy distraction focuses on salience. The climate crisis is at constant risk of being crowded out by other salient crises. This is why the ‘Crisis and COVID’ as well as the ‘Crisis and Russia’ treatments yield lead to lower support for fuel taxation than the simple ‘Climate’ prime. However, an alternative view might stress cost perceptions: Highlighting other short‐term crises may simply increase the perceived costs of fuel taxation rather than reduce the salience of the climate crisis.

If the argument about perceived costs of fuel taxation was true, we would expect the ‘Climate and Russia’ prime to reduce the effect of the climate crisis on policy support much stronger than the ‘Climate and COVID’ treatment. After all, the Russian invasion of Ukraine is directly linked to rising fuel and energy prices. However, our results show no differences between the two treatments.

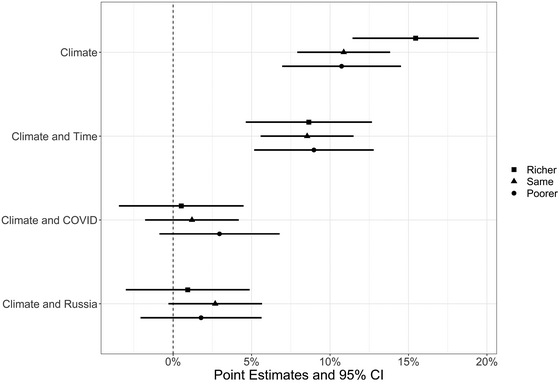

Another way to test the implications of the cost perception argument is to look at the treatment effects for different income groups. If changing cost perceptions of fuel tax hikes play a role, we would expect them to have a larger effect on poorer than on richer people. Hence, mentioning COVID‐19 and Russian military aggression should dampen the effect of the ‘Climate’ prime much stronger for poorer citizens. Figure 5 shows the treatment effects by subjective relative income position. Two things stand out. First, we find that the effect of the unrestricted ‘Climate’ prime is slightly higher for people who perceive themselves as richer than their peers. This is in line with recent work which has identified pocketbook concerns as a crucial driver of general carbon tax preferences (Beiser‐McGrath & Bernauer, Reference Beiser‐McGrath and Bernauer2024; Beiser‐McGrath & Busemeyer, Reference Beiser‐McGrath and Busemeyer2023). Second, we find no evidence that adding COVID‐19 or Russian military aggression reduces the effect more strongly for poorer households. This finding speaks against the notion that perceived costs of fuel taxation are driving our results.

Figure 5. Treatment effects of different primes on support for fuel taxation, subgroup analysis based on self‐reported relative economic position. All results are based on linear probability models. Table G5 (in the Appendix of the Supporting Information) shows the full results.

Heterogeneous treatment effects

We perform a battery of additional tests that check for heterogenous treatment effects. First, gender is an important, yet often overlooked factor when investigating subgroup effects in research on tax policy preferences (Seelkopf, Reference Seelkopf, Hakelberg and Seelkopf2021). Yet, we do not find gender differences in our treatment effects. The empirical patterns look similar for women and men (Figure F1 in the Appendix of the Supporting Information). Second, we check whether effects vary by rurality. More specifically, we compare treatment effects between respondents who live in more urban areas and those who live in rural areas as the latter are more dependent on cars that are still mostly running on fossil fuels.Footnote 9 Again, we do not find substantial and significant differences in treatment effects between subgroups (Figure F2 in the Appendix of the Supporting Information). Third, political trust might be an important factor moderating effects on support for fuel taxation (Fairbrother, Reference Fairbrother2019; Fairbrother et al., Reference Fairbrother, Johansson Sevä and Kulin2019). For instance, high‐trust respondents have less reason to fear that fuel tax revenues are abused. Hence, we check whether our results differ by trust in the national government (Figure F3 in the Appendix of the Supporting Information). We do not find substantially different subgroup effects.Footnote 10 Fourth, characteristics of the specific competing crises rather than general policy distraction could drive our results. If this is the case, one would expect the ‘Climate and COVID’ as well as the ‘Climate and Russia’ treatments to have a stronger negative effect on fuel tax support if people are more vulnerable to these crises. To check this, we run two types of subgroup analysis. In Table G6 (in the Appendix of the Supporting Information), we run interaction effects to see whether the treatment effects vary by age.Footnote 11 As older people are more vulnerable to health risks from COVID‐19, one might expect the effect of the ‘Climate and COVID’ prime to vary by age. However, we do not find a difference in the treatment effect for different age groups. Figure F4 (in the Appendix of the Supporting Information) shows whether effects differ by geographical proximity to Russia. If crisis characteristics rather than general distraction dynamics are driving our findings, we would expect the ‘Climate and Russia’ prime to vary by distance to Russia. We calculate the geographic distance from each country's capital to Moscow and compare the results for the more proximate countries to those for the more distant ones. The treatment effect of the ‘Climate’ prime is lower in those countries which are closer to Russia, but we find no subgroup differences for the ‘Climate and Russia’ treatment. Taken together, these findings indicate that individual characteristics of the two crises are less likely to drive the results.

Another important source of heterogenous treatment effects could be people's prior climate concerns. We check this by running subgroup analysis where we differentiate between people that name climate change as one of the most pressing issues their country is facing and those who do not name it (Figure F5 in the Appendix of the Supporting Information). We find little variation when it comes to the effect of the climate prime – for both subgroups, support increases substantially compared to the baseline. If the effect of the climate prime was solely driven by increased salience, we would expect substantial differences between these two groups. Thus, the results indicate that connecting climate change to the topic of fuel taxation is a crucial contributor to the treatment effects. It is also interesting to compare this finding to the analysis where we differentiate between the average country‐level salience of climate change (Figure 3). When differentiating between countries with higher and lower overall levels of climate change salience, we do find differences in treatment effects, whereas we cannot detect them at the individual level. One reason for this might be societal politicisation: When general politicisation of climate change in a society is high, the connection to fuel taxation could be clearer and preferences formation more advanced. Although our data do not enable us to expand on the differentiation between societal versus individual salience further, we see this as an interesting avenue for future research. When looking at the myopia and distraction treatments, we find that the distraction effect is somewhat smaller for those who see climate change as a pressing issue (in particular for the ‘Climate and COVID’ treatment). Thus, those who see climate change as one of the most important issues are less likely to be distracted by other events.

Conclusion

Can the climate crisis boost support for costly climate policies? To answer this question, we focused on fossil fuel taxation as an unpopular but effective climate policy instrument. We conducted a survey experiment with over 21,000 respondents in 17 European countries to investigate the conditions of support. Our analysis yields three main findings.

First, we found that a simple climate crisis prime substantially boosts support for fuel taxation. On average, support increases by 12 percentage points, and net support becomes positive. When respondents are alerted to the crisis and the link between the climate crisis and fuel taxation is made explicit, they are significantly more willing to support fuel taxes to mitigate the consequences of the crisis.

Second, myopia only mildly weakens support for fuel taxation. Stressing the long time horizon and the margin of error of climate change reduces the effect size of the climate crisis prime, as expected. However, the reduction is small. Although myopia is certainly important, it does not dominate climate concerns. The climate crisis has the potential to elicit support for countermeasures in much the same way as other dramatic crisis events like wars or recessions.

Third, we find strong evidence of distraction. Crisis‐induced support for fuel taxation is substantially crowded out by other salient events, such as the COVID‐19 pandemic and the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Interestingly, it is not the precise policy characteristics of the competing policy challenge that undermine support. Mentioning COVID‐19 or Russia in addition to the climate crisis prime reduces support for fuel taxation to a similar extent, even though both events differ in timing, policy features and cost implications. Apparently, it is not specific policy trade‐offs but the additional claim on respondents’ limited attention and capacity for worry that depresses support for climate mitigation. Arguably, any salient event has the potential to distract. Furthermore, we have focused on fuel taxation as one mitigation tool. It would be interesting to investigate whether similar empirical patterns can be observed when looking at policies that people strongly connect with the climate crisis in the first place (such as general carbon taxes).

In summary, our findings help to explain why the potential of the climate crisis to boost support for costly mitigation measures has its limits. In the baseline, the climate crisis competes with other crises and events that have a more short‐term time horizon, which divert people's attention. General myopia, but particularly distraction, undermines the capacity of the climate crisis to boost support for costly countermeasures. The temporal dimension of climate change, that is, the expectation of high and rising future costs, underlies both myopia and distraction. Investigating the impact of policy distraction in situations where the effects of the climate crisis are imminent may be a promising avenue for future research.

What are the policy implications of our findings? How can proponents of costly climate change mitigation tools overcome policy distraction and mobilise support? Three potential strategies stand out. First, keep climate policy in crisis mode to increase salience. This helps to keep citizens primed on the urgency of climate change and the need for policy remedies. One important instrument to achieve this purpose are self‐imposed deadlines such as the International Energy Agency's ‘Net Zero by 2050’ scenario (reducing the emissions of the global energy sector to zero by 2050) or the EU's ‘fit for 55’ plan (reducing EU emissions by at least 55 percent by 2030). The benefit of these deadlines is to regularly make present climate policies look behind target and deficient. This helps to ramp up worries, focus attention and increase tolerance for remedial action, including fuel taxation.

Second, use windows of opportunity presented by climate‐related natural disasters – floods, droughts, heat waves, forest decline, and so on – to focus attention on the climate issue. Natural disasters may convince even myopic voters of the urgency of immediate action. Also, uneventful stretches of normal history can be used to focus attention on the climate. Increased attention and salience will in turn facilitate ratcheting up taxes on fossil fuel. Once set at a higher level, it is easier to keep these taxes high. The new tax level becomes normalised and taken for granted. It can still be challenged, of course, but defending the status quo is usually easier than changing it (Peacock & Wiseman, Reference Peacock and Wiseman1961).

Finally, whenever policy distraction looms because non‐climate related crisis events gain salience and claim attention, policy makers should try to fuse them with the climate issue into an overarching crisis narrative that stresses policy synergies. As recent research by Bergquist et al. (Reference Bergquist, Roche, Lachapelle, Mildenberger and Harrison2023) has shown, integrating climate action into national COVID‐19 response‐plans can increase public support. If politicians can make the case that policies against climate change also help to mitigate the economic or social fallout of the COVID‐19 pandemic or help to decrease vulnerability to Russian coercion, this may fuse the issues in citizens’ minds, and reduce distraction. For instance, politicians could highlight that higher prices on fossil fuel not only reduce emissions but also boost green investments which help economic recovery post COVID‐19 and contribute to geopolitical resilience by decreasing dependence on Russian gas and oil. In fact, the EU already uses such a strategy of policy amalgamation. The green transition is now an integral element of both the EU's Recovery and Resilience Facility aimed at post‐pandemic economic stabilisation and its REPowerEU plan for energy independence from Russia.

Acknowledgements

We thank participants at the ECPR General Conference 2022, the International Conference of Europeanists 2023, the Dreiländertagung 2023, the Environmental Politics and Governance Network Online Seminar Series, and at seminars at the European University Institute, Max Planck Institute for the Study of Societies, HWK Delmenhorst, LMU Munich, ifo Institute, FU Berlin, ESM, King's College London, as well as Michael Bechtel, Liam Beiser‐McGrath, Björn Bremer, Reto Bürgisser, Federica Genovese, Lukas Hakelberg, Lauren Leek, Gerald Schneider, Nils Steiner, Konstantin Vössing and three anonymous reviewers for helpful comments and suggestions. Furthermore, we thank the Thyssen Foundation for funding an authors’ workshop on ‘Navigating Political Crises’ at the Hanse‐Wissenschaftskolleg in Delmenhorst, 28 September 2023–29 September 2023.

Online Appendix

Additional supporting information may be found in the Online Appendix section at the end of the article:

Figure B1: Baseline support for fuel taxation by country.

Figure B2: Support for and opposition against fuel taxation, full range of answer.

Figure C1: Treatment effects of different primes on support for fuel taxation, logit models.

Figure C2: Treatment effects of different primes on support for fuel taxation, full scale of answer categories.

Figure C3: Treatment effects of different primes on support for fuel taxation, three answer categories.

Figure C4: Treatment effects of different primes on support for fuel taxation, weighted regression analyses.

Figure C5: Treatment effects of different primes on likelihood of answering ‘do not know’.

Figure C6: Treatment effects of different primes on support for fuel taxation, full scale of answer categories and ordinal logit model.

Figure C7: Treatment effects of different primes on support for fuel taxation, three answer categories and ordinal logit model.

Figure C8: Treatment effects of different primes on likelihood of answering ‘neither support nor oppose’.

Figure C9: Treatment effects of different primes on support for fuel taxation, climate prime as reference category.

Table D1: Regression results for each country individually I

Table D2: Regression results for each country individually II

Table D3: Salience of climate change in countries in the sample, share of individuals that see climate change as one of the major challenges

Figure E1: Importance of different crises.

Figure F1: Treatment effects of different primes on support for fuel taxation, subgroup analysis based on gender.

Figure F2: Treatment effects of different primes on support for fuel taxation, subgroup analysis based on rural‐urban place of living.

Figure F3: Treatment effects of different primes on support for fuel taxation, subgroup analysis based on trust in national government.

Figure F4: Treatment effects of different primes on support for fuel taxation, subgroup analysis based on distance to Russia.

Figure F5: Treatment effects of different primes on support for fuel taxation, subgroup analysis based on perception of environment and Climate as a pressing issue.

Table G1: Balance check

Table G2: Main regression results

Table G3: Regression results for timing of fuel tax hikes

Table G4: Regression results for countries with low and high salience of climate change

Table G5: Treatment effects of different primes on support for fuel taxation, subgroup analysis based on self‐reported relative economic position

Table G6: Interaction of climate prime treatment effect with age and ideology

Data S1