Highlights

What is already known?

-

- 66 systematic reviews of face mask efficacy reached different conclusions

-

- Most mask efficacy studies are observational

What is new?

-

- Risk-of-bias tools were sometimes misapplied in non-expert hands

-

- The review process sometimes obscured important aspects of heterogeneity, leading to bland and unhelpful summary statements

-

- Many review teams lacked topic expertise, methods expertise or both

Potential impact for RSM readers

-

- The claim of ‘PRISMA-compliance’ may obscure questionable practices and judgements

-

- Training and oversight of reviewers is crucial when primary evidence is complex (i.e. extensive, heterogeneous, technically specialised, conflicting, contested)

1 Background

1.1 Introduction

The evidence base on some scientific issues is complex—large in volume, heterogeneous in focus and study design, and addressing complex chains of causality at different levels from molecular interactions to human behaviour to societal contexts. Mask efficacy in preventing respiratory infections is one such example. In an ongoing study of evidence synthesis methods related to this topic,Reference Greenhalgh, Helm, Poliseli, Ratnayake, Trofimov and Willliamson 1 we have identified approximately 300 primary studies on mask efficacy, of which only 26 are randomised controlled trials (RCTs). Some of these primary studies were carefully planned and rigorously executed; others occurred opportunistically during crisis periods. These studies are summarised in (so far) 66 systematic reviews, which addressed a variety of review questions using different approaches and came to seemingly opposing conclusions.

The predominance of observational (non-RCT) studies on the topic of mask efficacy raises the question of how (if at all) systematic reviews should include such designs. Several recent systematic reviews—notably, an updated Cochrane reviewReference Jefferson, Dooley and Ferroni 2 —have chosen to reject all observational studies of mask efficacy outright. Others believe that there are over-riding practical and ethical difficulties associated with conducting RCTs of mask efficacy and that even when internally valid (i.e. methodologically rigorous), a mask RCT may lack external validity (findings from Bangladesh villages during low-prevalence periods, for example,Reference Abaluck, Kwong and Styczynski 3 do not tell us what will happen in other settings).Reference Gurbaxani, Hill and Patel 4 , Reference Cash-Goldwasser, Reingold, Luby, Jackson and Frieden 5 A previous commentary from Cochrane editors on systematic reviews of public health interventions concluded that the vast amount of available observational evidence should, with appropriate quality assessments and caveats, be included in evidence syntheses to enrich the debate.Reference Hilton Boon, Burns and Craig 6

Observational studies of mask efficacy present challenges for reviewers because they are inconsistently titled, heterogeneous in study design and methodology, variable in quality, dispersed across a range of non-mainstream journals (since most leading journals favour RCT designs), and poorly indexed.Reference Banholzer, Lison, Özcelik, Stadler, Feuerriegel and Vach 7 A further challenge is the sheer volume of such evidence, which means that there is a high risk that studies will be read superficially or partially (e.g. with a view to populating predefined data fields) rather than fully and in depth.

Mask efficacy thus presents a paradigm case in how reviewers might handle complex primary evidence, especially heterogeneous datasets of observational studies. In this article, we critically examine how such studies have been evaluated by systematic reviewers and meta-analysts.

The remainder of this article is structured as follows. In the next section, we explain what we mean by ‘observational evidence’ in the context of mask efficacy and briefly summarise the strengths and limitations of different study designs. We then review orthodox methods of evidence synthesis for observational studies before introducing our aims and research questions. In the Methods section, we describe how we identified and critically examined a dataset of primary studies and the systematic reviews that had attempted to synthesise them. In the Results section, we describe how variation in search strategies, eligibility criteria, and synthesis methods led review teams to work with widely differing datasets of primary studies and generate different estimates of efficacy (and inefficacy). In the Discussion section, we question how far generic evidence synthesis tools can contribute to reviews when the primary evidence demands expert understanding and tailoring of study quality questions to the topic.

1.2 Observational studies of mask efficacy: an overview

Four broad kinds of observational study have addressed mask efficacy.

A case–control study is retrospective. It compares people with a disease (e.g. those testing positive for COVID-19) with those without, with a view to finding associations with past exposures (e.g. being unmasked when mixing with potentially infectious people). In a matched case–control design, cases are individually paired with controls who are similar in key characteristics that could influence both mask-wearing and disease risk. In an unmatched case–control design, individual matching is not used, and comparability at the group level is relied upon instead. Differences between groups are usually measured using odds ratio (OR), a measure of the relative odds of having been exposed, given that one has the disease, compared with not having the disease. Case–control studies are quick and relatively cheap to perform, but their retrospective nature makes them highly susceptible to recall and selection biases. Hence, any associations demonstrated in such studies may or may not be causal, and the measured effect size (or lack of it) may be an over- or underestimate.

In prospective cohort studies, two groups differing in exposure (e.g. masking or not during an infectious disease outbreak) are followed forward in time to see whether they differ in the incidence (new cases) of a disease. Differences between groups are usually measured using risk ratio (RR), a measure of how likely someone in one group is to develop the disease compared with someone in the other group. Risk difference (RD), which measures the absolute difference in risk between the exposed and unexposed groups, may also be used. Prospective cohort designs provide a stronger basis for inferring causality than case–control studies, but they are more expensive and time-consuming to conduct and face significant challenges in controlling for complex behavioural confounders (e.g. whether people who mask also differ systematically in how often they wash their hands, mix indoors with other people, or smoke). Cohort studies can also be undertaken retrospectively, with a greater risk of bias.

In cross-sectional studies, exposure (e.g. a response to a survey question about masking) and outcome (e.g. a swab for current infection or a test for antibodies to a disease) are measured at a single point in time. Such studies can compare disease prevalence in those who have or have not been masking during a recent outbreak. Differences between groups are measured in terms of prevalence. While cross-sectional studies can establish associations, they provide a weaker basis for inferring causality than either case–control or cohort studies, since the absence of a longitudinal component means a putative causal factor may or may not have predated the onset of disease.

Ecological studies (sometimes known as ‘natural experiments’) can trace what happens when a policy (e.g. a mask mandate) is introduced in a particular defined locality (e.g. a country, state, or city). These studies may use mathematical modelling to compute the complex interaction between real-world variables over time. Study designs range from simple before-and-after studies in a single setting, analysed using descriptive statistics (e.g. interrupted time series) through designs comparing one setting with another (mandate in place versus mandate not in place using difference-in-difference, regression, or synthetic controls) to mechanistic modelling (e.g. using compartmental SEIR—susceptible, exposed, infected, recovered—models). Ecological studies are sometimes included in the category ‘observational studies’, but they are usually excluded from systematic reviews of observational evidence on the assumption that multiple confounders are in play, and hence, grounds for causal inference are weak.

1.3 Synthesising observational evidence: tools for quality assessment

Observational evidence lacks the neatness of a controlled experiment, is vulnerable to numerous biases, and tends to be heterogeneous in multiple ways. The challenges this poses for evidence synthesis include the perils of spurious precision if meta-analysis is used to combine irregular primary evidence; arguments for and against the automatic downgrading of observational studies relative to RCTs (meaning that a high-quality observational study will be ranked as equivalent to, or even as lower than, a poor-quality RCT); and how to evaluate researchers’ efforts to mitigate the biases inherent in non-randomised designs.Reference Hilton Boon, Burns and Craig 6 , Reference Egger, Schneider and Smith 8 – Reference Dekkers, Vandenbroucke, Cevallos, Renehan, Altman and Egger 10

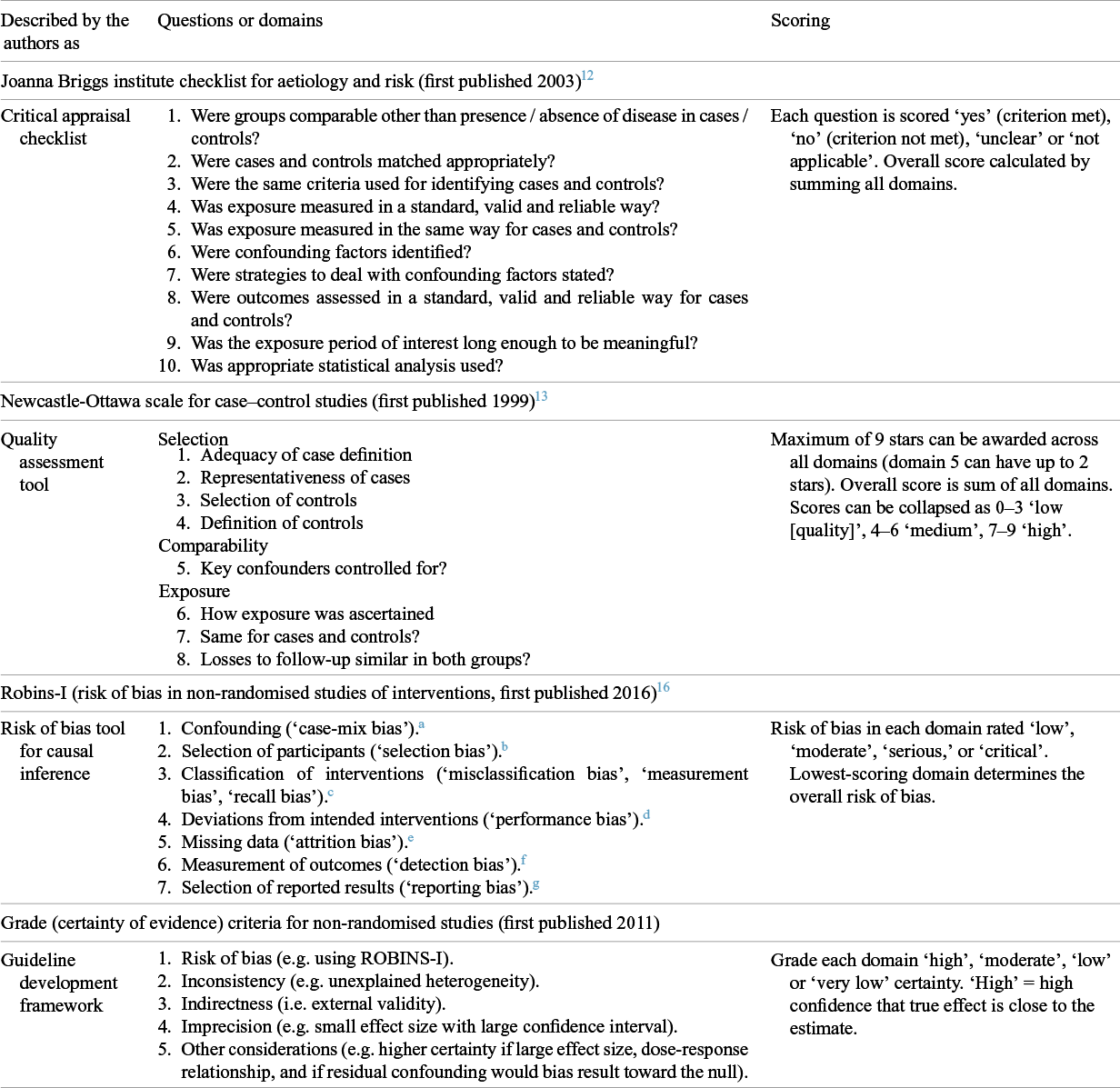

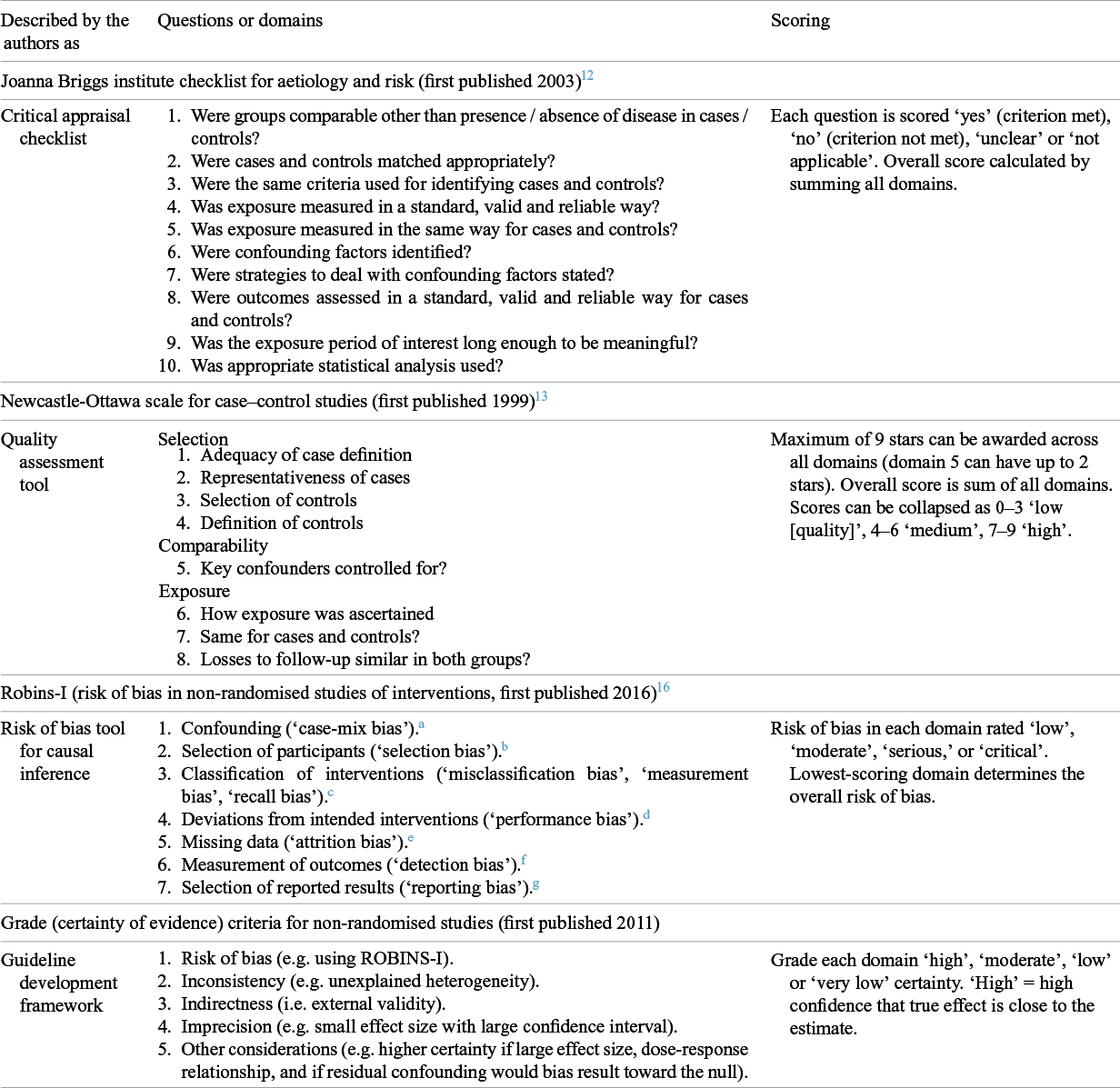

Tools to guide readers in assessing the quality of published research studies emerged in the late 1990s. The first such tools were described as ‘critical appraisal checklists’, of which early examples for observational studies include those from the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) in the UK 11 and the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) in Australia (shown in Table 1).Reference Moola S, Tufanaru, Aromataris, Aromataris, Lockwood, Porritt, Pilla and Jordan 12 Another early tool was the Newcastle-Ottawa [Quality Assessment] Scale (NOS),Reference Stang, Jonas and Poole 13 also shown in Table 1 and described by its authors as a ‘quality assessment tool’.

Table 1 Tools used for assessing quality in observational studies

Notes on Table 1:

a Especially, were groups comparable at baseline in key prognostic variables (e.g. age, vaccination status)?

b Especially, when some participants in one group but not the other are included in (or removed from) the denominator or differently followed up when outcomes are assessed.

c Especially, when people have received the intervention but have been classified as not having received it and vice versa.

d Especially, when one group receives additional measures to the intervention being assessed (e.g. advice or more frequent follow-up checks), or when the intended intervention is for some reason not delivered (e.g. due to lack of adherence).

e Especially, attrition (losses to follow-up) or missed appointments. Reasons for missing data must be explored.

f Especially, when the outcome of interest is misclassified (e.g. as not having developed the disease when the person did).

g Especially, when authors selectively reported those associations that turned out to be statistically significant.

While the above tools remain popular and are considered pragmatic and easy to use, they have been criticised for being vague, lacking validity, and scoring poorly on inter-rater reliability.Reference Hartling, Milne and Hamm 14 , Reference Barker, Stone and Sears 15 In recent years, a group led by Cochrane epidemiologists and statisticians has worked on a new suite of tools that focus systematically on predefined domains of bias.

The Risk of Bias in Non-randomized Studies of Interventions (ROBINS-I) tool,Reference Sterne, Hernán and Reeves 16 for example, is used for cohort studies where one group was offered an intervention. It is designed to support not merely quality assessment but causal inference. The tool views each observational study as an attempt to emulate a hypothetical pragmatic RCT (referred to as the ‘target trial’) and assesses bias relative to this ideal using counterfactual reasoning (i.e. considering what would have happened had an ideal RCT been possible). A bias may be non-differential (same in each group), which will tend to bias findings towards null (i.e. attenuate any measured effect). If a bias is differential (occurring more in one group than in the other), it could bias findings either towards or away from the null. The ROBINS-I items, however, focus on the presence and estimated magnitude of bias rather than on its direction.

In the accompanying guidance to ROBINS-I, reviewers are exhorted not to simply ‘score’ a study but to undertake a detailed, reasoned assessment of its flaws.Reference Sterne, Hernán and Reeves 16 The tool’s developers also emphasise that both methods experts (in epidemiology and statistics) and topic experts are needed to apply the tool to a particular research question, though they warn that topic experts may be swayed by subjective impressions, prior assumptions, or conflicts of interest and should not be allowed to dominate deliberations.

Though comprehensive, ROBINS-I has been criticised for being time-consuming to completeReference Zhang, Huang, Wang, Ren, Hong and Kang 17 and unreliable in the hands of reviewers who are not methodological experts, leading to a tendency to underestimate key bias domains and convey a false sense of certainty.Reference Igelström, Campbell, Craig and Katikireddi 18 A modified tool (ROBINS-I v2), which includes more detailed algorithmic guidance in an attempt to overcome these problems, was released in late 2024. 19

ROBINS-I is promoted by Cochrane as a next-generation tool on account of its comprehensive coverage of theoretical domains of bias. JBI methodologists have recently mapped the criteria in their critical appraisal checklists to key bias domains (e.g. ‘bias relating to temporal precedence’, ‘bias relating to administration of intervention/ exposure’) while retaining the original wording of items.Reference Barker, Stone and Sears 15 Like Cochrane, they have also lengthened the guidance and introduced a semi-quantitative (rather than yes/no) scoring system.

The ROBINS-E (‘E’ being ‘Exposure’) tool was developed for observational studies of exposures (including environmental, occupational, and behavioural factors), where RCTs are acknowledged to be less feasible.Reference Bero, Chartres and Diong 9 , Reference Higgins, Morgan and Rooney 20 ROBINS-E shares many of the core features of ROBINS-I, including the ‘target trial’ analogy, a seven-domain structure for assessing bias, and a semi-quantitative scale (low, moderate, serious, critical) for those assessments. Again, accompanying guidance encourages reviewers to eschew technocratic scoring and engage with the study’s detail—a feature that makes the tool time-consuming to use and critically reliant on the reviewer’s expertise. The ROBINS-E tool has been criticised for omitting some key sources of bias in exposure studies, failing to discriminate studies with a single risk of bias from those with multiple risks of bias, failing to distinguish confounders from co-exposures, and providing limited insight into whether confounders will bias study outcomes.Reference Bero, Chartres and Diong 9 We address additional debates about this tool in the Discussion section.

The ROBINS tools (and, less ideally, other quality assessment tools) can feed into the Risk of Bias domain in the GRADE process, designed primarily to assess the certainty of evidence when developing guidelines. As Table 1 shows, GRADE also includes additional considerations. Primary studies may be at low risk of bias, but the body of evidence on a topic may be imprecise (e.g. wide confidence intervals), inconsistent (i.e. show unexplained heterogeneity), or less relevant to a particular setting (i.e. have low external validity). According to GRADE guidance, the level of certainty of a body of evidence may be upgraded if the effect size is large, if a dose–response relationship is demonstrated, or if the direction of residual confounding would be towards null.

While there is broad consensus that the assessment of study quality (including but not limited to risk of bias) is mission-critical in evidence synthesis of observational studies, there are inherent trade-offs in the various tools on offer, notably whether to favour succinctness and simplicity or depth and comprehensiveness. The emergence of increasingly detailed guidance on how tools should be used raises questions around the extent to which reviewers read and take note of such guidance (and what might happen if they do not). However rigorous a tool’s development, its use still depends on subjective human judgments.

1.4 Aims and research questions

Our aim was, using mask efficacy as an example, to examine the extent to which orthodox evidence synthesis methods such as ‘PRISMA-compliant’ systematic review and meta-analysis are fit for purpose for assessing and combining complex evidence (i.e. extensive, heterogeneous, and with complex causal pathways). We focussed primarily but not exclusively on observational evidence because this is where review methodology is most contested.

Our research questions were:

How did reviewers of complex evidence on mask efficacy produce a manageable dataset from a large number of potentially relevant studies? If they rejected all observational studies outright, how was this decision justified?

How did reviewers deal with heterogeneity (e.g. in terms of study design, settings, populations, mask types, diseases, and primary outcomes) of primary evidence on mask efficacy? If meta-analysis was used, how were decisions made about ‘lumping’ or ‘splitting’ primary studies?

How did reviewers assess study quality (variously, overall study quality, risk of bias, and certainty of evidence)? To what extent were quality assessment tools used skilfully and judiciously? To what extent were quality assessments consistent across different review teams?

What general lessons can be learnt from this example about synthesising complex evidence?

2 Methods

2.1 Description of study and dataset

This is a sub-study of a wider programme of work funded by a UKRI programme for interdisciplinary research. We are using the efficacy of face masks and mask mandates in reducing transmission of respiratory disease as an example through which to develop new, interdisciplinary methods of evidence synthesis. Full methods, including detailed search strategies, are described in a separate protocol paper.Reference Greenhalgh, Helm, Poliseli, Ratnayake, Trofimov and Willliamson 1 An interdisciplinary advisory board provides wider academic expertise and external scrutiny. As desk research, it was deemed not to require research ethics approval.

To briefly summarise our search strategy for identifying publications on mask efficacy, we supplemented keyword searches across multiple databases (PubMed, EMBASE, Social Science Citation Index) with additional methods, including authors’ prior knowledge of the topic, contacting topic experts, mining previous systematic reviews and primary studies, and forward-tracking selected studies in Google Scholar. Electronic searches on this complex topic proved neither sensitive nor specific, but the combination of methods allowed us to iteratively build a database containing dozens of previous systematic reviews and hundreds of primary studies up to September 2025. No language restriction was applied (though in practice most papers were in English); non-English language papers were appraised by multilingual academic colleagues with advanced training in systematic review methods.

We collated studies described by their authors as systematic reviews or meta-analyses (including ‘narrative systematic reviews’ but excluding narrative reviews without a formal search strategy or methodology). We downloaded the full papers and also all supplementary materials. We contacted authors if material referred to in the paper (e.g. item scores on quality instruments) was unavailable online. We created a spreadsheet summarising their country of origin, authors’ backgrounds, review focus, selection criteria for primary studies, methods (especially which quality assessment tools were used), key findings, and strengths and limitations. We also summarised all identified primary studies on a separate spreadsheet.

For the analyses presented in this article, we used our dataset of systematic reviews and considered how they had dealt with primary studies, especially observational designs (i.e. non-randomised ones, including case–control, cohort, cross-sectional, and ecological). All assessments were undertaken independently by two authors (TG and SR), with differences resolved by discussion. Where there was residual disagreement, the assessment was categorised as ‘uncertain’.

2.2 Analysis of systematic reviews of mask efficacy

We examined each of the 66 systematic reviews of mask efficacy for their funding source and author expertise. We classified an author as having methodological expertise if they had a degree in epidemiology, medical statistics, evidence-based medicine or similar discipline, or a clear track record of a substantive role in a previous systematic review. We classified them as having topic expertise if they had played a substantive role in non-laboratory empirical research studies of mask efficacy or infectious diseases more generally. This approach probably overestimated expertise, since we did not take account the quality of the authors’ previous empirical research.

We looked at the reasons given for not including observational studies if the authors had made this choice. We identified which primary observational studies had been covered in the remaining reviews and how decisions about eligibility, study quality, and aggregation (e.g. whether to do a meta-analysis) had been made. We selected a maximum-variety sample of five ‘tracker’ primary studies that had been included in at least five systematic reviews in our sample. These comprised: two studies of healthcare workers in the 2003 SARS outbreak (one unmatched case–control from Hong KongReference Seto, Tsang and Yung 21 and one retrospective cohort from CanadaReference Loeb, McGeer and Henry 22 ); two studies of COVID-19 in community settings (one matched case–control from ThailandReference Doung-Ngern, Suphanchaimat and Panjangampatthana 23 and one outbreak investigation [retrospective cohort] from ChinaReference Wang, Tian and Zhang 24 ), and one unmatched case–control study of influenza transmission on a flight from the USA.Reference Zhang, Peng and Ou 25 These were selected to provide a range of countries, settings, study designs, and contexts, and also to have been undertaken early enough to have featured in several systematic reviews.

For each tracker study, we identified all the systematic reviews that had included it. We critically examined how each systematic review had assessed the study, including whether and how it was included in meta-analyses, whether and how study quality tools were used, and any interpretive commentary or justification for scores awarded. We compared these approaches across reviews. This exercise was undertaken independently by two reviewers (TG and SR), and differences were resolved by discussion.

3 Results

3.1 Description of the dataset

Our search produced a dataset of 66 systematic reviews plus approximately 300 primary studies on mask efficacy, comprising 26 RCTs, 129 observational (cohort, case–control, and cross-sectional) studies and 145 ecological or modelling studies. Of these studies, 100 were in healthcare; most of the remainder were in the community; and two considered both. An additional literature on laboratory experiments on mask efficacy was outside of our scope. A table presenting descriptive data for the systematic reviews is available in Supplementary Material 1. Further details of the primary studies are available from the authors.

Of the 66 systematic reviews, 59 had been published since 2020. Forty reported no funding at all, and another four acknowledged only a personal salary for one author (though it is possible that even when no funding was acknowledged, the work may have been undertaken in paid time). The other 22 reviews had received public funding (government or WHO commissions, or research calls). Of the 66 reviews, 39 included authors with demonstrable expertise in evidence synthesis (e.g. an academic appointment in epidemiology); in a further nine reviews, at least one author may have had some training and experience in review methods. Ten reviews included an author with demonstrable expertise in researching the efficacy of masks in infectious disease outbreaks; in another seven reviews, one or more authors may have had some expertise in this topic.

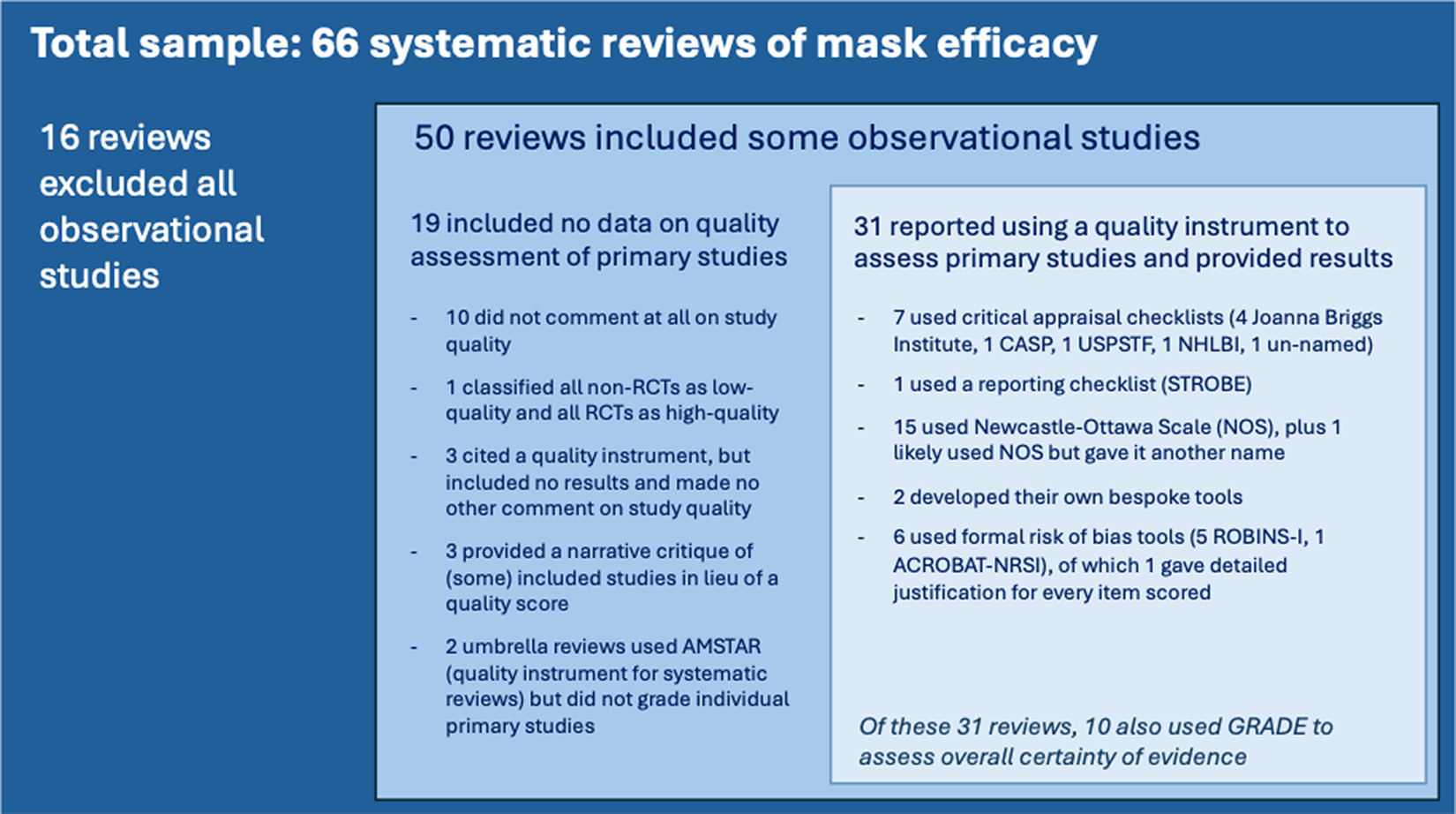

Of these systematic reviews, 19 were restricted to community settings; 20 looked only at healthcare settings; and 27 considered both. Sixteen excluded observational evidence. Of the remaining 50, 24 included at least one statistical meta-analysis of observational studies and the other 26 presented data from observational studies in disaggregated form (e.g. in tables). Most reviews addressed all respiratory infections or respiratory viral infections; two were restricted to influenza and 13 to COVID-19.

Of the 66 reviews, only seven covered any ecological or dynamic modelling studies, and in only two were these designs the main focus of the review. This is a major limitation of the body of secondary literature as a whole, since infectious disease outbreaks show complex geographical and temporal dynamics and masking will have different (and changing) efficacy depending on the nature and phase of the outbreak.Reference Heesterbeek, Anderson and Andreasen 26 , Reference Anderson, Heesterbeek, Klinkenberg and Hollingsworth 27 The strengths and limitations of ecological designs are beyond the scope of this article, but it is worth noting that reviews that cover only ‘static’ designs will provide, at best, a static picture of mask efficacy.

Overall, 37 of the 66 systematic reviews concluded that masks reduced the transmission of respiratory infections or that respirators (e.g. N95s) were more effective than medical masks in this regard. The remaining 29 concluded either that the evidence supported lack of efficacy or that definitive evidence either way was lacking.

3.2 How reviewers produced a manageable dataset

When (as with mask efficacy) the number of primary studies on a topic runs into hundreds, reviewers must either limit their focus or prioritise a subsample of studies for analysis. One commonly used strategy by reviewers was to reject observational evidence altogether—which in this dataset would reduce the number of primary studies by around 90%. Of the 16 reviews that excluded all observational evidence, 14 gave no reasons; one acknowledged the existence of an extensive body of observational evidence but said that this was likely to ‘introduce noise into findings’ (p. 2),Reference Tran, Mostafa and Tawfik 28 and one considered observational evidence unnecessary because there were ‘sufficient’ RCTs to answer the review question (p. 10).Reference Jefferson, Dooley and Ferroni 2

Most review teams that chose to include observational evidence restricted the focus in some way—for example, by looking only at certain study designs (e.g. case–control studies), only at protection of healthcare workers, only at a particular disease, or only at special settings (e.g. pilgrims attending mass religious gatherings). This way, most reviews covered a manageable dataset of fewer than 40 primary studies. A few, however, retained a broad focus (and indeed, some chose to cover all non-pharmaceutical interventions, including masks, hand hygiene, physical distancing, and stay-at-home orders, in a single review). These authors faced a primary dataset that was potentially overwhelming, requiring them to make trade-offs between breadth and depth.

3.3 Dealing with heterogeneity

Even with explicit restrictions on study eligibility, most review teams still found themselves grappling with a sample that was highly heterogeneous and difficult to tame. Primary studies had addressed different research questions (e.g. source control versus wearer protection) in different diseases (influenza, SARS, MERS, COVID-19, bacterial superinfection), populations (e.g. healthcare workers, pilgrims attending mass gatherings, lay public), and settings (e.g. high risk such as infectious disease wards or households with an infected family member; or low risk such as communities where background prevalence of the disease was low). They had used different study designs (e.g. case–control, cohort, RCT), interventions (cloth masks, medical masks, respirators, with varying instructions for when and how to wear them), type of outcome (population-level epidemiological [e.g. number of confirmed cases], individual-level epidemiological [e.g. date of symptom onset], individual-level behavioural [e.g. self-reported adherence]), specific outcome measures (e.g. symptoms, clinical assessment score, laboratory test, rapid antigen test), and measures of effect size (secondary attack rate, RR, OR, RD).

While tables of study characteristics sometimes conveyed a broad sense of this heterogeneity, they rarely fully made sense of it. Absent from the reviews was an overall sense of why different studies had approached mask efficacy in widely differing ways and the contribution made by different study designs and settings to the overall picture. Indeed, with few exceptions and notwithstanding ‘grand means’ generated by meta-analysis, there was no overall picture.

The number of primary studies included in meta-analyses ranged from one to several hundreds (see Supplementary Material 1). Primary studies were lumped and split in different ways, including by study design (e.g. cohort studies analysed separately from case–control), details of intervention (e.g. whether N95s were worn continuously or intermittently in healthcare settings), or primary outcome (e.g. influenza-like illness, clinical respiratory illness, serologically confirmed clinical symptoms, or PCR test). Twelve reviews combined different study designs in a single meta-analysis. One of these split a large dataset in multiple ways: healthcare versus community, Asian versus non-Asian (a proxy for whether attitudes to masks were positive), and virus type (influenza, SARS, or COVID-19).Reference Liang, Gao and Cheng 29 Another combined household transmission studies (in which a symptomatic family member was the index case) with healthcare settings on the grounds that both are high-risk settings for disease transmission.Reference Ollila, Partinen and Koskela 30

As shown in Table S1 in the Supplementary Material 2, our five tracker studiesReference Seto, Tsang and Yung 21 – Reference Zhang, Peng and Ou 25 were included in 11, 17, 15, 4, and 4 separate meta-analyses, respectively. In each case, the study was combined with a different selection of other studies, and (unsurprisingly) the analysis produced a different OR for mask efficacy. In all but one case, however, the meta-analysis demonstrated a significant effect of masks compared with no masks and for N95s (or other respirators) compared with medical masks.

Almost all meta-analyses of observational evidence in our dataset included every study deemed eligible for inclusion by the authors, whatever the risk-of-bias score assigned. Thus, studies at critical risk of bias were combined statistically with those at low risk of bias, with no adjustment. One review (Chu et al.Reference Chu, Akl and Duda 31 ) omitted primary studies from the meta-analysis if they had not adjusted for confounders. Another review (Yanni Li et al.Reference Li, Liang and Gao 32 ) offered a sensitivity analysis in which they used raw data from primary studies to adjust for confounders when the authors of the primary studies had not done so; these adjustments did not change the overall effect size estimate. As noted by Paul et al., stringent omission of unadjusted observational studies can produce an ‘empty’ review since many such studies do not adequately adjust for confounders and raw data may not be forthcoming from authors.Reference Paul and Leeflang 33

3.4 Assessment of study quality

The 50 systematic reviews in our sample that included observational studies used various instruments to assess their quality. These comprised the NOS,Reference Stang, Jonas and Poole 13 JBI critical appraisal checklists for cohort and case–control studies,Reference Moola S, Tufanaru, Aromataris, Aromataris, Lockwood, Porritt, Pilla and Jordan 12 US Preventive Services Task Force checklist for observational studies, 34 CASP checklist for cohort and case–control studies, 11 STROBE reporting guidelines for observational studies,Reference Ghaferi, Schwartz and Pawlik 35 National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI) quality assessment checklist, 36 ROBINS-I,Reference Sterne, Hernán and Reeves 16 and ACROBAT-NSRI (an early version of ROBINS-I developed by Cochrane).Reference Sterne, Higgins and Reeves 37

Two reviews developed bespoke risk-of-bias tools for their datasets (one by adapting NOSReference Ford, Holmer and Chou 38 and one by adapting a previous bespoke tool for ecological studiesReference Mendez-Brito, El Bcheraoui and Pozo-Martin 39 ). No review used ROBINS-E, which was perhaps surprising (while ‘masking’ is an intervention, ‘being unmasked’ in an infectious environment was sometimes described as an exposure). Nineteen reviews either did not use a quality tool for observational studies or (in three cases) provided no results for the tool they did use, though one out of the three supplied these data when we requested them.

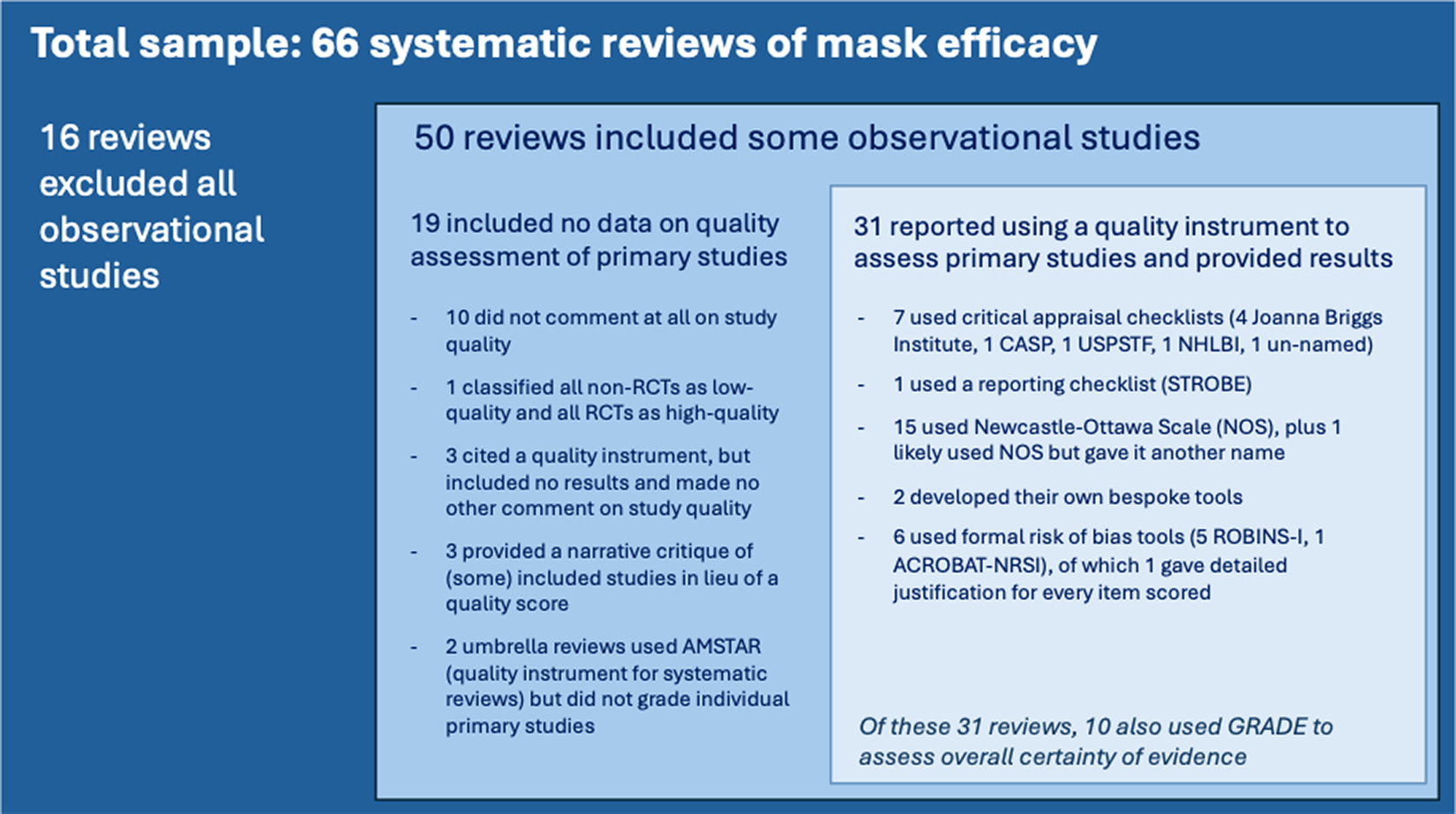

Figure 1 shows how the 66 systematic reviews dealt with observational evidence. This highly varied treatment of observational evidence contrasts with the way reviewers assessed risk of bias in RCTs: 28 out of the 33 reviews that covered RCTs used the Cochrane risk-of-bias tools.

Figure 1 How 66 systematic reviews addressed the quality of primary observational studies of mask efficacy.

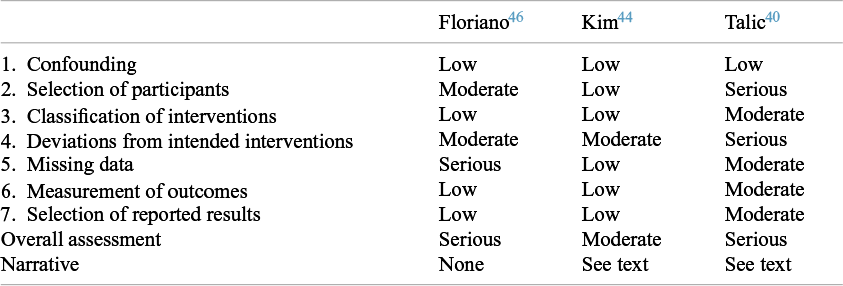

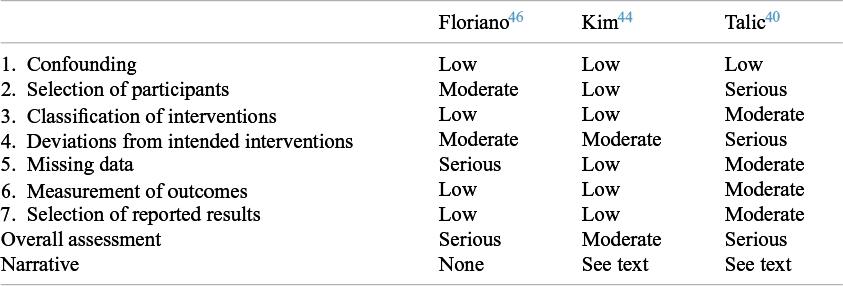

Pursuing our five selected tracker studiesReference Seto, Tsang and Yung 21 – Reference Zhang, Peng and Ou 25 through all the systematic reviews that had included them revealed widely differing judgments about their quality. Details of this analysis are provided in the Supplementary Material 2 (see Tables S2–S12). We illustrate our findings here using a community-based matched case–control study from Thailand undertaken during the COVID-19 pandemic by Doung-Ngern et al.Reference Doung-Ngern, Suphanchaimat and Panjangampatthana 23 This study was covered by 11 of the 66 systematic reviews.Reference Li, Liang and Gao 32 , Reference Talic, Shah and Wild 40 – Reference Rohde, Ahern and Clyne 49 Of these, four cited the NOS,Reference Li, Liang and Gao 32 , Reference Chen, Wang, Quan, Yang and Wu 43 , Reference Hajmohammadi, Saki Malehi and Maraghi 45 , Reference Tabatabaeizadeh 47 though one gave no data and the remainder only gave an overall score (8/9, 9/9 and 9/9, i.e. all ‘high quality’). Two used the JBI checklist for case–control studies; one scored every domain as ‘yes’ (low risk of bias), producing an overall score of 12, while the other scored only four domains as ‘yes’, which would produce a score of 4.Reference Crespo, Fornasier, Dionicio, Godino, Ramers and Elder 48 , Reference Rohde, Ahern and Clyne 49 One used the US Preventive Services Taskforce checklist and assessed overall study quality as ‘poor’.Reference Chou and Dana 42 Three reviews used the ROBINS-I; their assessments, which produced overall scores of ‘serious’, ‘serious’, and ‘moderate’ risk of bias, are reproduced in Table 2.Reference Talic, Shah and Wild 40 , Reference Kim, Seong and Li 44 , Reference Floriano, Silvinato, Bacha, Barbosa, Tanni and Bernardo 46 One review did not use a risk-of-bias score.Reference Boulos, Curran and Gallant 41 Only one reviewReference Kim, Seong and Li 44 provided a discussion of what the main biases were and estimated the direction of these biases.

Table 2 Scores awarded by systematic reviews to the Doung-Ngern study using robins-I

Similar analyses on four other tracker studiesReference Seto, Tsang and Yung 21 , Reference Loeb, McGeer and Henry 22 , Reference Wang, Tian and Zhang 24 , Reference Zhang, Peng and Ou 25 are available in Supplementary Material 2. They confirm wide variation in assigned scores (e.g. scores on a single item on the NOS ranged from 2/9 to 7/9; on one ROBINS-I subdomain, scores ranged from ‘low risk of bias’ to ‘critical risk of bias’). We consider the implications of this variation in the Discussion section.

3.5 Limited narrative

A striking feature of most reviews in our dataset was the limited amount of information about primary studies that was provided outside the structured tables of predefined data fields. Particularly in reviews covering large numbers of studies, information from primary studies was compressed into lengthy tables (usually supplied only as online supplements to the main paper). Accompanying narratives to explain these structured data summaries and justify the scores awarded were absent or extremely brief, even in the supplements.

Only one review in our sample (Kim et al.Reference Kim, Seong and Li 44 ) set out a detailed narrative justification for every risk-of-bias judgment for every study (as recommended by the ROBINS-I authorsReference Sterne, Hernán and Reeves 16 ). A few reviews (see, for example, Talic et al.Reference Talic, Shah and Wild 40 and Chen et al.Reference Chen, Wang, Quan, Yang and Wu 43 ) included brief comments on limitations in their tables of included studies. In addition, three reviews which did not use a formal score or checklist provided a narrative critique of at least some observational studies in the text of the paper.Reference Boulos, Curran and Gallant 41 , Reference Greenhalgh, MacIntyre and Baker 50 , Reference Cowling, Zhou, Ip, Leung and Aiello 51 But all these examples were the exception. In most reviews, the risk of bias or other quality assessment was expressed only as a numerical score or ordinal category (e.g. ‘moderate’).

Yet a close read of the Doung-Ngern case–control study,Reference Doung-Ngern, Suphanchaimat and Panjangampatthana 23 for example, revealed many distinctive features that were not captured in any of the systematic reviews. For example, this study was undertaken at a very early stage in the COVID-19 pandemic when community transmission was only just beginning, meaning that contamination from other community contacts was highly unlikely. The research team asked detailed questions about when and how masks were worn when in the vicinity of the index case, allowing them to estimate fidelity of the intervention and test the hypothesis that to be effective, masking must be continuous. This hypothesis was supported in an important negative finding: people who wore masks only some of the time when in contact with an index case were no less likely to develop COVID-19 than those who did not mask at all, whereas those who continuously wore masks were significantly less likely to do so. This finding aligns with background evidence that respiratory diseases are airborne, so infectious particles can spread to fill an indoor space and may remain viable in the air for minutes or even hours after being generated in a cough, sneeze, or exhaled air.Reference Wang, Prather and Sznitman 52 Additionally, the study provided early evidence to challenge the ‘risk compensation’ hypothesis that was popular at the time: people who wore masks were significantly more likely to wash their hands regularly, practise social distancing, and spend less time in close contact with others than those who did not.

The explanations in Kim et al.’s comparative effectiveness systematic review of respirators, medical masks, and cloth masks were important.Reference Kim, Seong and Li 44 An example is missing data, a well-recognised source of bias in case–control studies. In the Doung-Ngern study, data on whether the index case had worn a mask was missing in 27% of people interviewed. When justifying their score of ‘low risk of bias’ for missing data in this study, Kim et al. stated: ‘Missing values for mask wearing [by index cases] not included in analyses. For other variables, missing values were [assumed to be] random and were imputed by chained equations.’ This brief narrative, along with details of the imputed datasets, illuminates a judgment about the extent to which missing data influenced the trustworthiness of the findings, given the study’s authors’ own decisions to exclude them or their attempts to correct for them. It explains why the score they awarded differs widely from that given by Floriano et al. using the same tool.Reference Floriano, Silvinato, Bacha, Barbosa, Tanni and Bernardo 46 The latter authors give no narrative and appear to have treated the item as a simple yes/no question of whether some data were missing. Given the variability in scores across reviews, this absence of narrative justification in all but a handful of reviews is concerning.

Few systematic reviews in our sample included any reasoning about the likely direction of biases identified. In the Doung-Ngern case–control study, for example, a key bias is that only 89% of the controls were tested for SARS-CoV-2. The authors reasoned that missed individuals were likely to be true negatives because they had been in less close contact with the index case and for less time (at a time when community prevalence of the disease was very low), but as one or two systematic reviews pointed out, some of these individuals could have been misclassified. However, such misclassification would tend to bias findings towards null, so a statistically highly significant result despite these missing data is unlikely to be spurious. We conducted a sensitivity analysis which showed that even if half of the untested controls were actually positive (perhaps asymptomatic) COVID-19 cases, the crude OR would change only from 0.72 to 0.79 and the adjusted OR from 0.23 to 0.26.

We detected a marked shift in style and tone from the earliest systematic review in our dataset to the latest. Cowling et al. provided a detailed explanatory account of the 11 studies published at the time, stating that a meta-analysis was inappropriate because of heterogeneity.Reference Cowling, Zhou, Ip, Leung and Aiello 51 In contrast, Chen et al., whose sub-study on mask efficacy is part of a wider review on the impact of adherence to masking, listed no fewer than 448 primary studies representing 654 datasets in a single supplementary table and offered various meta-analyses of these (though not all studies addressed mask efficacy); no primary study was described or critiqued in the main paper.Reference Chen, Zhou and Qi 53 While this was an extreme example, almost all reviews published since 2020 offered extensive structured data but lacked explanatory detail.

In most cases, the conclusions of these systematic reviews were bland, unnuanced, and non-definitive (e.g. ‘There is limited, low certainty direct evidence that wearing face masks reduces the risk of transmission of SARS-CoV-2 in community settings. Further high-quality studies are required to confirm these findings.’ (p. 2)Reference Rohde, Ahern and Clyne 49 ). Such statements, while not incorrect, suggest that many review teams had either been unable to identify high-quality existing primary studies (especially observational ones) or were not confident to draw firm conclusions from these studies.

4 Discussion

4.1 Summary of principal findings

This study of evidence synthesis methods for mask efficacy studies has revealed some findings that are concerning but perhaps not surprising given that most were undertaken during the COVID-19 pandemic—a time when research on pandemic-related topics expanded rapidly, pressure to produce outputs was high, and quality control was variable. Hundreds of primary studies have addressed the topic, but fewer than 10% of these were RCTs; the remainder were a highly heterogeneous collection of observational, ecological, modelling, and other designs, presenting challenges for review teams. Most systematic reviews of these studies were done without dedicated funding and hence without a budget for bringing in specialist expertise or protected time for the close reading and deliberation needed to make judgments about complex evidence.

Review teams handled observational evidence in a variety of ways. In a few cases, reviewers combined methodological and topic expertise and applied the newer, more extensively validated risk-of-bias tools appropriately to produce a synthesis that was detailed, nuanced, and authoritative. Many review teams, however, appeared to lack methodological expertise, topic expertise, or both; they tended to use older, shorter, and less robust risk-of-bias tools. Furthermore, such tools were sometimes used inconsistently and superficially, producing unreliable scores offered with no explanation or justification. Various moves by reviewers—excluding observational evidence altogether, assessing risk of bias but not its direction or importance in a particular study and context, omitting distinguishing details of primary studies, and presenting meta-analyses that combined studies of different designs or included those at critical risk of bias—served to obscure important aspects of heterogeneity, resulting in bland, non-definitive, and conflicting summary statements. Interpretive syntheses to explain the nuances across heterogeneous primary evidence were largely absent.

These important limitations of many systematic reviews of mask efficacy were evident despite evidence (in most cases) of authors’ diligent efforts to produce a ‘PRISMA-compliant’ review characterised by a thorough search, systematic assessment of primary studies, ‘objective’ risk-of-bias scoring, and meticulous tabulation of such scores.

4.2 Implications

While the example of systematic reviews of mask efficacy undertaken mostly during the COVID-19 pandemic may not be representative of systematic reviews more generally, we believe our findings justify four key conclusions. First, more attention needs to be given to the training and oversight of authors who take on systematic reviews of complex evidence, especially in the selection and use of risk-of-bias tools. Second, both methods experts and topic experts appear to be needed to optimise the operationalisation and application of such tools to make judgments. Third, reviewers should publish (or make available) not only the outputs of their assessments of primary studies but sufficient rationale to allow readers to understand, and be able to agree or disagree with, how the tools were operationalised to the topic and the main judgments reached. And finally, reviews would be more informative if they indicated, for each study, the direction of each bias (towards null, away from null, or either way) as well, simply identifying whether it is present.

4.3 Comparison with previous literature

Our findings illustrate how the commendable efforts by methodologists to develop robust and reliable tools and guidance for synthesising observational evidenceReference Dekkers, Vandenbroucke, Cevallos, Renehan, Altman and Egger 10 , Reference Sterne, Hernán and Reeves 16 , 19 , 54 have, at least in some public health topics, been offset by three things: the vast expansion in the volume and heterogeneity of observational evidence;Reference Banholzer, Lison, Özcelik, Stadler, Feuerriegel and Vach 7 , Reference Mei, Yao and Wang 55 the growing tendency of inexperienced review teams to take on complex evidence synthesis projects;Reference Igelström, Campbell, Craig and Katikireddi 18 and (real or perceived) pressures to generate policy-relevant systematic reviews at pace during periods of crisis.Reference Corrin and Kennedy 56 While several high-quality systematic reviews existed, they were greatly outnumbered by lower-quality ones.

Our finding that there was no consistency in how review teams handled heterogeneity aligns with other studies in the literature. Published advice on this topic focusses almost exclusively on approaches to statistical heterogeneity.Reference Hilton Boon, Burns and Craig 6 , Reference Mueller, D’Addario and Egger 57 , Reference Metelli and Chaimani 58 Mueller et al. summarised advice on synthesis of observational evidence from 93 previous articles in their 2018 systematic review.Reference Mueller, D’Addario and Egger 57 These articles gave different advice on which criteria should be used to lump or split studies in meta-analyses, though most methodologists considered that analyses should be split by study design. Recommendations also differed on the value of quality scores (including risk-of-bias) when used across heterogeneous datasets. While some scholars viewed these tools as an essential component of a good review, others were concerned that expressing quality judgments in terms of a summary score was problematic since a) observational studies are subject to many different biases, b) these different biases may be additive, multiplicative, or cancel out, and c) use of such scores can (in the words of one quoted commentatorReference Greenland 59 ) ‘seriously obscure heterogeneity sources’.Reference Mueller, D’Addario and Egger 57

While there is a move among review methodologists to recommend against meta-analysis when primary studies are highly heterogeneous (see, for example, the SWiM [Synthesis Without Meta-analysis] reporting guidanceReference Campbell, McKenzie and Sowden 60 ), our own finding that none of the 66 reviews used SWiM suggests that this advice has not reached most of the people undertaking such reviews.

Ours is not the first study to demonstrate that risk-of-bias assessment can be particularly unreliable in observational studies. Some controlled experiments designed to test the performance of such tools showed high inter-rater reliability when used by skilled reviewers.Reference Kalaycioglu, Rioux and Briard 61 , Reference Minozzi, Cinquini, Gianola, Castellini, Gerardi and Banzi 62 But other similar experiments showed moderate to poor inter-rater reliability.Reference Hartling, Milne and Hamm 14 , Reference Robertson, Ramsay and Gurung 63 , Reference Jeyaraman, Rabbani and Copstein 64 Inter-rater reliability improved substantially after the review team received trainingReference Kaiser, Pfahlberg and Mathes 65 and when reviewers spent more time on each assessment.Reference Momen, Streicher and da Silva 66 The more detailed tools such as ROBINS-I were experienced as ‘difficult and demanding’ even by skilled reviewers,Reference Minozzi, Cinquini, Gianola, Castellini, Gerardi and Banzi 62 and papers have been written on ‘assessor [or evaluator] burden’.Reference Jeyaraman, Rabbani and Copstein 64 , Reference Momen, Streicher and da Silva 66

Our study differed from these publications in that we did not set out to formally test risk-of-bias tools by comparing how trained reviewers scored a pre-selected sample of papers. Rather, we looked at the published results of systematic reviews undertaken ‘in the wild’ to see how the tools had fared in the hands of review teams, many of whom were under-resourced, lacked methodological or topic expertise, and were attempting to deal with complex datasets of primary evidence.

Our findings align with those of two other overviews of systematic reviews. Mei et al. showed that most of their sample of 220 systematic reviews had assessed risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions using the NOS or other first-generation tools, while very few used ROBINS-I.Reference Mei, Yao and Wang 55 Igelström et al. looked only at ROBINS-I; they found that in 124 systematic reviews across a wide range of topic areas, misapplication of this tool was common.Reference Igelström, Campbell, Craig and Katikireddi 18 In particular, 89% of these reviews included no explanation or justification for scores awarded and 20% included studies classed as ‘critical risk of bias’ in meta-analyses. Whereas Mei et al. and Igelström et al. considered the ‘in the wild’ use of risk-of-bias tools across multiple topics, our own study considered the use of such tools (or no tools) by a sample of reviews on a single topic.

4.4 Strengths and limitations of this study

The key strength of this study is our novel methodology of close reading of an entire dataset of all available systematic reviews on a complex and contested topic, including tracking a sample of primary studies through all reviews that included them to reveal variation in the depth of analysis and final scores awarded. We approached our sample of reviews not primarily with data extraction in mind but with a view to understanding why review teams ‘in the wild’ made the choices they did and how they selected and used tools for study quality. As such, our study complements previous work on the usability and reliability of risk-of-bias tools conducted in experimentally controlled settings. A limitation of our method is that we were unable to generate formal inter-rater reliability scores, but (unsurprisingly) we were able to demonstrate wide and frequent discrepancies across reviews and unpack, item by item, not just the range of scores awarded but why review teams differed so widely.

4.5 Philosophical reflections on risk-of-bias tools

Our discovery that systematic reviews of mask efficacy can produce unreliable findings despite the use of risk-of-bias (and other quality assessment) tools—and indeed, that in non-expert hands, these tools may reduce the reliability of the findings—raises philosophical questions about the place of such tools in evidence synthesis. These questions relate to (among other things) the nature of the knowledge that can be captured in the tool; the nature of the knowledge required to use the tool; and the nature, magnitude, and direction of the biases that the tool is intended to evaluate. Observational evidence brings these questions to the fore, since the biases are multiple and complex and play out differently (and in different directions) in different study designs.

Some of these philosophical questions have been touched upon in a recent public disagreement among tool developers. Steenland et al., who were originally part of the development group for ROBINS-E, explained in an open letter why they withdrew their names from all publications related to it.Reference Steenland, Straif and Schubauer-Berigan 67 Their concerns include that the ‘target trial’ analogy is inappropriate for exposures (they believe) as the mechanisms of exposure and disease may not align with the intervention model of an RCT; the structure of the bias domains creates high potential for unnecessary exclusion of high-quality studies; the tool places insufficient emphasis on how triangulation using other kinds of evidence (see, e.g., Lawlor et al.Reference Lawlor, Tilling and Davey Smith 68 ) can help mitigate biases in exposure studies; it does not consider the direction of bias or the extent to which bias in one direction might balance out a different bias in the other direction; and there is no domain for either the quality of statistical methods or conflict of interest.

These points echo those made in an earlier paper by Arroyave et al.,Reference Arroyave, Mehta and Guha 69 who argue that risk of bias in observational studies should be assessed either using a tool that compares each study with a hypothetical ideal observational study (as occurs in some toxicology syntheses) or by constructing a bespoke tool for each topic using precise criteria for each risk-of-bias domain relevant to the exposure–outcome relationship under study.

In a response to Steenland et al.’s open letter,Reference Steenland, Straif and Schubauer-Berigan 67 the remaining ROBINS-E authors expressed concern that their detractors’ proposed alternative approach, based substantially on the judgments of topic experts rather than methods experts, is unsystematic and subjective (and hence, unreplicable) and that while triangulation is a promising approach for complementing the use of ROBINS-E, it currently ‘lacks a formal framework’ (p. 1).Reference Higgins, Rooney and Morgan 70

This debate reflects a polarisation that can be traced to foundational assumptions about the nature of knowledge for evidence synthesis. Orthodox review methodologists assume that, notwithstanding the limitations of any particular tool, it is theoretically possible to develop generic tools that will, in the right hands, produce valid and replicable estimates of risk of bias for each study design. These scholars consider that the expertise needed is predominantly methodological (i.e. related to the methodology of evidence synthesis) and that while topic experts may need to be consulted, they should not be making the key methodological decisions since, as leading Cochrane methodologists once claimed, ‘[topic] expert advice is often unreliable’ and such experts ‘may have personal prejudices and idiosyncrasies’.Reference Gøtzsche and Ioannidis 71

Those who reject the assumed theoretical benefits of a rigorously developed risk-of-bias tool do so on both practical and philosophical grounds. Practically, Savitz et al. cautioned that whatever caveats are added by a tool’s authors, in reality such tools are almost always applied ‘mechanistically’, prioritising repeatability of scoring over depth of analysis and paying scant or no attention to whether a particular bias is actually meaningful or important in any particular topic area.Reference Savitz, Wellenius and Trikalinos 72 Philosophically, the grounds for rejection can be explained in terms of Wittgenstein’s rule-following paradox, namely that ‘no course of action could be determined by a rule, because any course of action can be made out to accord with the rule’ (Philosophical Investigations, §201).Reference Wittgenstein 73 That rules are not self-interpreting does not, in fact, mean that all rules should be abandoned (as a reviewer of an earlier draft of this article pointed out, this would effectively kill the science of systematic review). It means that however rigorous the rule and however detailed the instructions are for applying it, there will always be an element of interpretation and judgment involved, and novel cases will arise that are not covered by existing instructions. As an early set of guidance from the US Association for Healthcare Research and Quality put it, ‘Using transparent rules does not remove the subjectivity inherent in assigning the risk of bias category’ (p. 19).Reference Viswanathan, Ansari and Berkman 74 Accordingly, we suggest that the task of applying a rule in any given case requires not merely review methodology knowledge (e.g. what domains to cover about risk of bias in general) but topic-based expert judgment (what domains to cover, and how these should be operationalised, in relation to a specific scientific topic)—and perhaps most importantly, deliberation between methods experts and topic experts on how to fit the tools to the topic.

To accurately evaluate study quality, generic biases (e.g. ‘misclassification of exposure’) must be translated into topic-specific ones (e.g. classifying whether someone was adequately masked when in a potentially infectious setting). To date, this crucial act of translation has received little attention from either tool developers or philosophers of science. It requires detailed topic knowledge—for example, knowledge that because respiratory diseases are airborne, indoor crowded settings are of particularly high risk and masking must be continuous while indoors (rather than restricted to one or two metres from suspected infectious people). Philosophically, such knowledge is classified as indirect or background knowledge—that is, knowledge that relates to a hypothesis via a long chain of reasoning using auxiliary claims.Reference Begun 75 Our findings that many systematic reviews a) do not include topic experts and b) provide no detail on how generic items were operationalised suggest that much further work is needed to optimise this important aspect of evidence synthesis.

In his PhD thesis on the philosophy of evidence synthesis (using mask efficacy as one example), Begun observes that in systems with high causal complexity, individual pieces of evidence can provide only noisy and indirect access to underlying phenomena. In such cases, hypothesis-testing requires not merely consideration of direct evidence (i.e. evidence that relates to the hypothesis through a short chain of reasoning), but also ‘background knowledge [which] typically allows researchers to reliably judge when the hypothesis space is exhaustive’ (p 44). In other words, Begun views topic expertise as essential to ensure that a full and detailed explanatory account of the evidence is produced. While orthodox systematic review (PRISMA) methodology does not direct reviewers to ignore background knowledge, it does not explicitly encourage them to map the hypothesis space as a preliminary step to seeking empirical studies, nor does it say how methods experts and topic experts should work together on reviews.

5 Conclusion

The evaluation of the role of face masks in preventing respiratory infections is a paradigm case in synthesising complex (i.e. extensive, heterogeneous, technically specialised, conflicting, contested) evidence. Through a close analysis of 66 existing systematic reviews, we have shown how, even when using formal tools, review teams find such evidence hard to assess and summarise, and they may therefore reach divergent conclusions. We believe our findings raise important questions about how generic risk-of-bias tools are currently used, especially in situations where the primary evidence demands expert understanding and tailoring of risk-of-bias questions to topic. In an ongoing research study, we are seeking to develop novel review methods for complex evidence which take a systematic approach to a) deciding which studies (especially, which observational ones) to include; b) dealing with heterogeneity; c) selecting and operationalising risk-of-bias tools (including when and how to adapt these to topic); and d) combining the use of formal tools (to maximise replicability) with interpretive methods (to provide context and nuance). It is too early to say whether these proposed new methods will improve the validity and reproducibility of reviewer decisions, but that is our ultimate aim.

Acknowledgements

We thank the members of our interdisciplinary advisory group and also the following academic colleagues for translation of non-English language papers: Ariel Wang, Xiaoxiao Ling, and Sufen Xhu.

Author contributions

Conceptualisation: T.G.; Data curation: T.G., S.R.; Formal analysis: T.G., S.R.; Funding acquisition: T.G., R.H., J.W.; Methodology: T.G.; Supervision: T.G.; Writing (original draft): T.G.; Writing (review and editing): S.R., R.H., L.P., J.W.

Competing Interest Statement

T.G. led a previous narrative review on masks and is a member of Independent SAGE. All other authors declare no competing interests.

Data availability statement

All data are in the public domain.

Funding statement

This study is supported by UKRI Cross Research Council Responsive Mode (CRCRM) grant 25130 for Interdisciplinary Research. The funder had no role in developing the protocol or the conduct of the study.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/rsm.2026.10072.