Introduction

Chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy treatments have increased the life expectancy of cancer patients. However, depending on the effect of some of the agents used such as alkylating agents, these treatments may cause premature ovarian failure and irreversible loss of fertility.Reference Maltaris 1 In the context of childhood cancers, it is now acknowledged that possible negative effects of therapies on future reproductive autonomy are a major concern. While a few fertility preservation (FP) options are open to postpubertal patients such as oocyte or embryos cryopreservation, the only option currently open to prepubertal girls is cryopreservation of ovarian tissue and subsequent autotransplantation.Reference De Vos 2

Ovarian tissue cryopreservation (OTC) with successful subsequent ovarian tissue transplantation (OTT) can help restore fertility lost or diminished due to cancer treatment, and to have a genetically related child as an adult.Reference Pacheco and Oktay 3 Pregnancy has been observed worldwide in women who had OTC and OTT as adults.Reference Su 4 Proponents of OTC point out that it promotes future reproductive autonomy and can reduce long-term distress. Opponents highlight that OTC involves surgical risks, uncertain future benefit, and ethical challenges around proxy consent in pediatric context. Moreover, OTT is still experimental because of the few successful pregnancies and because it involves a risk of reintroduction of cancer cells. High costs also raise concerns about equitable access and opportunity for families. These challenges are particularly pronounced when considering the procedure for young girls, a population recognized as especially vulnerable.Reference Dunlop and Anderson 5 In this context, the girl’s best interest covers both her current interest in minimizing risk and her future interest in reproductive capacity and choice.

Availability and management of oncofertility treatment vary considerably from one country to another. For example, in France the provision of FP is required by the bioethics law. Clinicians are required to inform patients of the risks of cancer treatment on their fertility, suggest fertility options to mitigate these risks, and refer them to a fertility specialist. 6 The duty to provide information and systematic access to FP is also recalled in the National Cancer Plan 2021–2030. 7 In Canada, unlike France, there are no national FP recommendations. Moreover, public funding of FP for women and girls with cancer exists only in the province of Quebec (approximately 22% of the Canadian population). Stipulated by Bill 20, insurance coverage includes the ovarian tissue retrieval procedure and freezing for 5 years. 8 In other provinces, patients can only be included in specific fertility programs or referred to non-profit organizations such as Fertile Hope to help defray costs.Reference Nisker, Baylis and McLeod 9 Unlike France, which is characterized by a centralized healthcare system, Canada is a federation where healthcare is considered within a provincial context. Each province has its own healthcare system. As a result, there is a variety of coverage across Canada, based on the priorities of different jurisdictions.Reference Sutherland and Busse 10

For our study, the choice of these locations was informed by the fact that OTC is available and covered by the public health system in France, whereas in Canada this is only the case in the province of Quebec, and because in France, contrary to Canada, it is mandatory to inform patients and families about FP techniques. Given the legal and economical differences, what are the ethical implications of the policy guiding OTC in these two contexts? To answer this question, we conducted a qualitative study to (1) explore pediatric oncologists’ perceptions regarding barriers and facilitators of OTC in prepubertal girls and (2) analyze the ethical, legal, social, and policy implications of these barriers and facilitators.

Methods

This study was part of a mixed-methods sequential explanatory strategy, including a first quantitative phase and a second qualitative phase.Reference Creswell and Plano Clark 11 The integration that characterizes a mixed-methods study was performed in the linking phase between quantitative results and qualitative data collection.Reference Pluye and Bujold 12

1. Quantitative Phase

The objective of the first phase was to identify the practices and attitudes of pediatric oncologists regarding barriers and facilitators to OTC. A standardized email describing the study’s objectives was sent to 260 pediatric hematologists/oncologists, inviting them to complete an online survey available in English and French. The survey was informed by a literature review and included questions on demographics, knowledge of OTC, responsibility for counseling, and public healthcare funding. It also featured open-ended questions on barriers and ethical concerns related to OTC. A total of 81 pediatric oncologists — 46 French and 35 Canadians — completed the survey. The results were already published.Reference Affdal 13 Some of these results, such as the information obligation in France and the effect of the coverage of OTC costs on practice, were explored in the qualitative phase. The quantitative results were also used to develop the interview guide for the qualitative phase.

2. Qualitative Phase

This second qualitative phase aimed to explore pediatric oncologists’ perceptions of the barriers and facilitators to OTC, as well as to analyze the ethical, legal, social, and policy implications associated with these factors.

2.1. Data Collection

Recruitment and interviews were conducted from November 2022 to August 2023. An invitation to participate was sent by email to the 81 Canadian and French participants who had already completed the survey in the first phase of the project. We thanked them for their participation in the first phase of the project and informed them of the continuation of the data collection. Three reminders were sent out, and interested participants were contacted by email to schedule a date and time to suit them.

The participants received no compensation. Interviews were conducted in English or French via videoconference, by AA. The interviews lasted between 22 minutes and 1 hour 8 minutes and were recorded with the consent of the participants.

The interviews began with a brief presentation of the project and study objectives, thanking them again for their participation in the previous quantitative phase (survey responses). Participants were given the opportunity to ask questions about the study before the interview began. The issues addressed during the interviews were described in an interview guide developed by AA, MB, and VR. The guide addressed the following themes: (1) experiences and opinions in pediatric oncofertility, (2) ethical issues surrounding OTC such as cost and post-mortem disposal of ovarian tissue, (3) legal obligation to inform about FP, (4) recommendations about FP programs, and (5) sociodemographic data.

2.2. Analysis

Our data analysis framework is based on Braun and Clarke’s (2006) thematic analysis.Reference Braun and Clarke 14 Before proceeding with the thematic analysis, all the recordings were transcribed, then transferred to the NVivo software, taking care to remove the identifiers of the participants to ensure confidentiality. Then, all the transcriptions were revised, listening to the audio version to check for any errors. An external researcher with experience with qualitative research also coded 15% of the transcriptions to ensure reliability. Where there were discrepancies, the results were discussed between AA and the external researcher LA to reach consensus and ensure the accuracy of the study’s interpretations.

2.3. Ethical Considerations

Participants received written and oral information about the study and how results would be used. They were informed that participation was voluntary, that they could withdraw at any time without any reason, and that data were treated confidentially. All participants provided written consent. The study received ethical approval from the Health Research Ethics Committee (CÉRES) of the Université de Montréal in Canada (#15-131-CERES-D) and from the Comité de Protection des Personnes (CPP) Île-de-France IV at Hôpital Saint-Louis in Paris, France (2016/62NI).

Results

1. Participant Characteristics

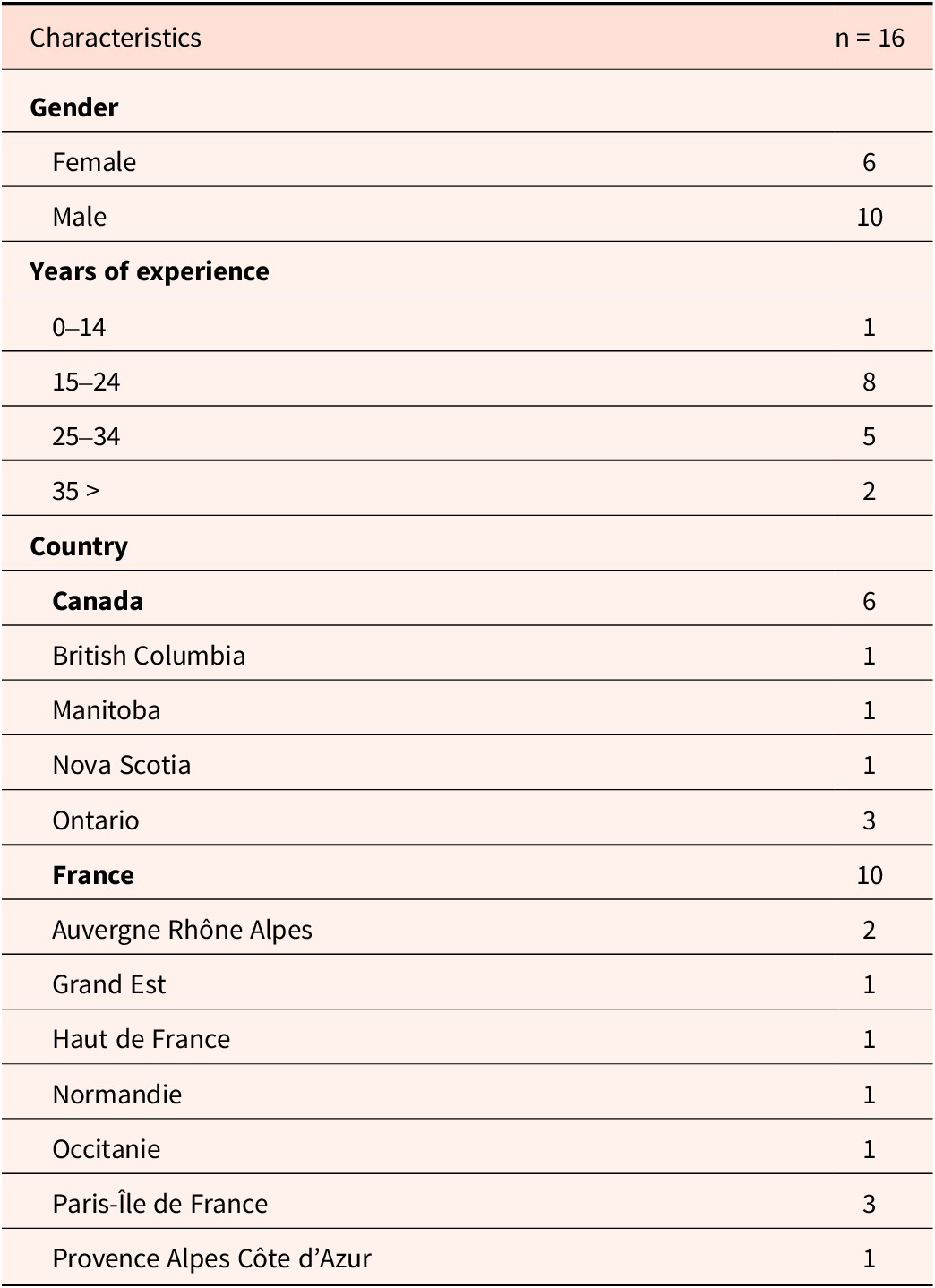

A total of sixteen pediatric oncologists took part in the study. This represents 19.75% of those who participated in the first quantitative phase in France and Canada. Ten were French and six were Canadian. Participants most frequently had between 15 and 24 years of practice experience. Table 1 summarizes participants’ characteristics.

Table 1. Participants’ characteristics

2. Themes

Our analysis identified three main themes: FP is an integral component of pediatric oncology care, the cost and lack of OTC coverage limit access to FP and lead to injustice, and the risks and uncertainties of OTC complicate practice. Each theme is described in terms of the similarities and differences between Canadian and French participants of this study and illustrated with quotes.

2.1. Fertility Preservation as an Integral Component of Pediatric Oncology Care

Across both Canadian and French participants, FP was described as an integral component of pediatric oncology care. Clinicians framed FP not simply as a clinical offering, but as a fundamental right (FrM1) and a central part of care (CaM1), especially in contexts where cancer treatment is likely to compromise future fertility. Several respondents emphasized that the ethical imperative to offer FP stems from the foreseeability of infertility, with one French clinician stating that it would be “unthinkable, unethical” (FrM4) not to offer FP options when sterility is anticipated.

Participants also noted the symbolic and emotional significance of FP in the cancer care trajectory. Fertility was described by a Canadian doctor as “the last thing the patient has to lose” because “with cancer, the patient loses control” (CaM3). Despite its importance, one participant deplored that the symbolism of fertility is not strong enough compared to the symbolism of life in the context of cancer. Another participant believes that FP remains crucial even in cases with limited therapeutic prospects. For him, FP is required especially when there are “therapeutic prospects,” but even “if there is only a 10% chance of cure” (FrW1).

The importance of communication also emerged from interviews. A Canadian pediatric oncologist thinks it is important to have FP discussions even if OTC is not offered, as the conversation itself respects patients’ and families’ concerns:

We don’t offer tissue conservation anyway, so why have that conversation? My view is everybody just deserves to have that conversation because everybody thinks about it. (CaW1)

On the question of legal frameworks, the majority of participants expressed support for existing policies requiring clinicians to inform patients about FP. The majority of Canadian and French participants believe that, although a law is legitimate to oblige doctors to provide information on FP to patients, they already do so out of moral duty and good practice.

It’s really a practice, a moral duty for doctors. We all do it, so we don’t ask ourselves any questions. (FrM1)

I think that is our standard of care whether it’s a legal thing or not. Yeah. I’m not sure if, I’m not sure that it needs legal requirement. I think it’s good practice. (CaM3)

In contrast, one participant stresses that the existing law in France on the obligation to provide information about FP is a good legislative measure:

It’s a good thing the bioethics law is mandatory, because if it wasn’t, we’d still be asking questions. I don’t think it’s necessarily due to refusal, but to ignorance. (FrM6)

At the same time, pediatric oncologists may feel obliged to offer OTC because they could be sued in case of infertility. Failing to inform families about FP options could expose them to legal action in the event of subsequent infertility.

I suppose in the litigious system, if a family was not offered fertility preservation and became infertile. Then they do have grounds to sue. (CaW1)

2.2. Cost and Lack of Coverage of Ovarian Tissue Cryopreservation as Limiting Access to Fertility Preservation, Leading to Injustice

In general, Canadian and French participants felt that OTC should be covered by the public health system to promote equity of access.

French pediatric oncologists described a range of reasons why OTC costs should be covered, such as the low cost to the healthcare system. Others pointed out that the number of cure rates is high (+80%) and the proportion of children treated for cancer remains low, so the cost to society is acceptable. Moreover, the non-coverage of OTC raises an ethical issue that may compromise the child’s future motherhood.

Well, if there was no financial support for the technique, well there is a real ethical issue. In other words, we’re reducing these girls’ chances of future motherhood, on the grounds that they have to pay for it. (FrM6)

Some French pediatric oncologists pointed out that if OTC was not covered, many families would not be able to afford it. For them, even when the prognosis for survival is poor, OTC should be covered by the public health system, because the prognosis of a disease is never certain. Moreover, this would be a double burden for patients and families, as they would have to bear the cost of OTC, in addition to the cost of the cancer.

It’s out of the question for a family for whom cancer is already going to cost a lot of money. There are always additional expenses, things we can’t cover. It’s out of the question that it won’t be covered. (FrM1)

To explain the non-coverage of OTC in Canada (with the exception of Quebec), Canadian pediatric oncologists think that is due to the low number of pediatric oncology and hematology patients. These patients “fall under the government’s radar” (CaM3). One of them pointed out that “there’s so much money to go around in the healthcare system for very urgent things,” that OTC can be “difficult to justify” in this context (CaM3).

Furthermore, the majority of Canadian pediatric oncologists stressed that OTC should be covered by the public health system. However, for one of them, this would be unreasonable. Given that “very few cryopreserved tissues will result in a successful pregnancy,” the procedure would be too costly. For him, “it should be covered like any other health research by a provincial mechanism or a federal fund” (CaM2).

2.3. Ovarian Tissue Cryopreservation Risks and Uncertainties as Complicating the Practice

Uncertainties Regarding Infertility Risk and Future Fertility

Some participants highlighted the inherent uncertainty in predicting infertility risk following cancer treatment, particularly in prepubertal patients. The variability of treatment intensity and individual biological response complicates efforts to provide families with precise prognostic information.

In some cases, patients presumed to be infertile post-treatment may later conceive spontaneously.

I remember, for example, the young girl (…), we gave her a lot of chemo, and not long ago she contacted me to say she was pregnant. (FrM1)

On the other hand, there are also concerns that some young women who were not offered OTC during childhood may later experience regret or express blame toward their pediatric oncologist.

The problem is that, yes, sometimes the prognosis is poor, but it’s never zero, and the children can blame us for not having offered them this technique when it was available. (FrM4)

One participant expressed uncertainty about tissue viability, as it is difficult to assess how ovarian tissue harvested at age 5 will mature and develop in the now-adult patient’s body. In contrast, another participant was optimistic, pointing out that certainties evolve with practice.

Ambiguous Experimental Status and Risk of Reintroduction of Malignant Cells

The OTC technique has been described as experimental by most Canadian participants, whereas the majority of French pediatric oncologists no longer consider it experimental. For one of them, it is the ovarian tissue transplantation (OTT) that raises issues, not the removal. They pointed out that only reimplantation is experimental.

Ovarian tissue preservation in itself is not. Reimplantation, again, yes. (FrW2)

However, they stressed that the procedure still carried a potential risk. They also noted they did not know how effective the technique would be in the future, given that there are very few births to prepubertal girls.

Canadian participants were more concerned than French participants about the risk of reintroducing malignant cells, which they saw as problematic. For one of them, a theoretical risk exists for all forms of cancer, not just leukemia.

I think a real issue that needs to be solved or resolved is the risk of re-implantation of cancer into the patient from cryopreserved tissue (…). But it’s a real problem I think for leukemia. Which goes into all tissues in the body, but it’s a theoretical problem for other types of cancers as well. (CaM2)

One participant described the importance of ovarian tissue research for the advancement of science, while regretting that the law does not allow it.

Some French pediatric oncologists consider that the risk of malignant cells is controllable, or will be thanks to advances in medicine, notably molecular tools that enable precise detection of the presence of cancerous cells. However, one French participant is very concerned about a study he conducted:

Ah well, I’m very worried, because we did a study and found (…) the presence of markers of residual disease in ovarian tissue, sometimes in the cortex, whereas the residual disease was negative. (FM7)

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first qualitative study of Canadian and French pediatric oncologists’ views on FP by OTC. Three main themes were identified: (1) the importance of FP, (2) the cost of OTC and lack of coverage by the public health system, and (3) the risks and uncertainties of OTC. One of the major findings was the description of FP as important and as a “fundamental right.” As participants’ quotes illustrate, they present fertility as a central element of care. The child’s right to FP as perceived by participants is recognized in bioethics literature as a right to an open future.Reference Larcher 15 It is a right in trust — as defined by Feinberg — that must be protected until the child reaches adulthood and is capable of exercising this right and making decisions.Reference Feinberg, Aiken and LaFollette 16 This means that, from an ethical perspective, FP including OTC should be offered and covered. Although there are many conceptual frameworks in pediatrics, we discuss our results within this framework of the right to an open future, as FP was framed in this way by the participants. More recently, authors have conceptualized the term “fertility in trust” as the ethical obligation to acknowledge the long-term significance of fertility and to support adolescents’ emerging autonomy by preserving their future capacity to make parenthood decisions.Reference Taylor and Ott 17

It is important to clarify the difference between the concepts of offer and coverage of OTC. Offer refers to the availability of the procedure in certain centers, regions, provinces, or countries. This means that the technique can be performed by physicians. Ovarian tissue can be removed, frozen and transplanted, while the girl recovers. Coverage, on the other hand, refers to whether the cost of the procedure is covered by the public health system. In this case, the family does not have to pay for it out of pocket.

1. Ethical and Legal Implications

Offering OTC is a Right to an Open Future

According to the participants, FP is both a right and an ethical duty. The availability of OTC must therefore be discussed from the perspective of human rights, and more specifically the right to an open future. Respecting the principle of the right to an open future means protecting the future rights of children. Therefore, parents should not take actions or make decisions that would permanently prevent their children’s future options. In the case of fertility, this right implies not being sterilized in order to have the right to reproduce as an adult,Reference Davis 18 and in the context of this study, the right to have access to fertility preservation.

Results have shown that failure to offer this option is seen by participants as almost a violation of human rights, and failure to receive full information about FP may constitute a violation of informed consent. Access to FP for pediatric patients can be understood as part of the child’s right to the highest attainable standard of health, as enshrined in Article 24 of the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child. 19 This right encompasses not only immediate survival and protection, but also the promotion of long-term well-being, including future reproductive autonomy. In the context of gonadotoxic treatments, FP may serve to mitigate foreseeable harm and support future quality of life. From a reproductive justice perspective, which upholds the rights to have children, not have children, and to parent in safe environments, FP access — particularly for girls — functions as a protective intervention.Reference Mohapatra 20 It helps preserve future reproductive choices for individuals whose fertility may be compromised by illness or its treatment.

In the pediatric bioethics literature, the right to an open future is mainly used in reference to the parents’ decision. However, it is also necessary to examine it from a clinical and a systemic perspective. In order for parents (or patients based on age) to have access to FP and make an informed decision, health professionals must inform, discuss, and be able to offer options such as OTC. Failure to do so could constitute a violation of the autonomy of the patient and her parents, since they are deprived of information that concerns the protection of a future choice.

As one of the pediatric oncologists pointed out, it is necessary to have this discussion even in cases where FP is not offered. The majority of participants emphasize that it is good practice and their sense of moral duty that lead them to provide this information. These results show that participants are inclined to have this discussion, without it being imposed by law, as is the case in France with the bioethics law. 21 Other studies have shown that they do not always do so, for several reasons, including clinical ones, such as the absence of a fertility specialist in the same center.Reference Lawrenz 22 In a study published in 2007, the difficulty of finding OTC specialists was the most important obstacle for healthcare professionals.Reference Marques 23 Even if the decision is not to proceed with OTC,Reference Stern 24 the discussion can have a positive psychosocial effect in providing hope for the future, coping better with the disease, and with cancer treatment.Reference Ben-Aharon 25

Covering OTC Promotes Equity

The results highlighted significant differences in coverage between Canada and France. In addition, costs may vary by hospital and public health system. In Canada, the cost of OTC is approximately $2,500, including storage fees for the first year. 26 Thereafter, the cost is $500 per year. Since only patients in Quebec province can access OTC free of charge in Canada, these high costs for some families call into question the ethical principle of justice. Indeed, the financial reality may constitute a barrier to equal access. Even in Québec, the current policy remains inequitable, as public coverage for storage is limited to five years. While this timeframe may be reasonable for adult-onset conditions such as breast cancer, it is inadequate in the context of pediatric FP. For prepubertal patients undergoing OTC, a minimum of ten years is typically required before the tissue could feasibly be used, given that most girls reach menarche around age twelve — marking the latter stages of puberty. The perspective of pediatric oncologists echoes that of the Canadian Fertility and Andrology Society (CFAS), which “encourage provincial legislators to cover the associated cost of OTC.” 27

This unfairness can also lead to a lack of information about OTC. Studies have shown that clinicians’ perceptions of the patient’s economic and social resources can be an obstacle to discussing FP. Thus, in places where financial coverage of FP does not exist, discussions are rarer,Reference Quinn 28 exacerbating the lack of information. Fertility as a long-term concern is shaped by short-term clinical choices, requiring parents — and, to some extent, young girls — to entrust healthcare providers with safeguarding this aspect of their future, thus the “fertility future.” 29 As one of our participants and literature pointed out, some families report being so intensely focused on the child’s survival at the outset of treatment that they are unable to fully consider FP during the limited window in which such decisions must be made.Reference Rodriguez-Wallberg 30 This trust in providers helps ease the emotional burden on the family at this particular moment. It should result in an effort by the physician to discuss FP and present options when available to parents who may not be willing to consider them given the time of great vulnerability. Therefore, in a context of respect for the right to an open future, parents should have access to this information.

In addition to an equity issue, the noncoverage of the technique by the healthcare system implies the principle of distributive justice. The high cost of the procedure may force parents to reallocate their limited financial resources to preserve the future reproductive potential of the child with cancer. However, this reallocation may be to the detriment of the needs and possibilities of their other children, since even for families who can afford to pay, the question of opportunity cost arises. Is the investment in one sick child taking away opportunities from a sibling? For example, the funds used to cover the OTC could have been used to finance the educational, developmental, or medical needs of a sibling.Reference Galvin and Clayman 31 In this way, parents are placed in the difficult position of favoring the potential future interests of one child over the present or future needs of another. Although decisions of this nature may arise for certain families irrespective of the costs associated with FP, the substantial financial burden of FP extends this dilemma to families who might otherwise not encounter economic strain. The tension appears most acute when financing FP threatens to compromise the fulfillment of other children’s “basic needs,” including educational, developmental, or medical requirements, as the authors have already observed.

2. Policy Implications in the Context of Scientific Uncertainty

If FP by OTC is perceived as a central part of care and a fundamental right, measures must be taken to make this right effective. The role of the state in protecting this right would require it to invest in this technology to promote its offer, coverage, and more research.

Most Canadian participants believe that OTC should be covered by the public health system. In contrast to France, Canadian policies regarding public coverage of OTC are heterogeneous, with only the province of Quebec offering public coverage. Both countries have healthcare systems strongly rooted in public insurance, but they operate differently. In France, the healthcare system is national, whereas in Canada, it is provincial, so the provision of care may differ from one province to another.Reference Thomson 32 The state in collaboration with provinces should guarantee equity of access, ensuring that public coverage is equitable across Canada’s different geographic zones. 33 In France, although the technique is widely available and offered, the state should ensure that every center can offer it. Indeed, disparities in geographical access in Canada and to a certain extent in France can exacerbate existing health inequalities both within and between countries. 34 Without system-wide readiness, public funding risks deepening regional and socioeconomic disparities in access, making careful planning and resource allocation essential.

Implementing public coverage would also require ensuring sufficient access to trained fertility specialists and infrastructure, which are currently limited. Pediatric oncologists’ teams would need additional training about FP options, the state of the science and discussion of fertility risks and referrals early in treatment. Pediatric oncologists may be too negative toward a cancer diagnosis or too positive despite presenting that uncertainty to families to provide informed consent.Reference Knapp, Quinn and Woodruff 35

Although pediatric oncologists consider FP a fundamental right and encourage coverage by the healthcare system, many Canadian participants consider OTC to be a nonstandard technique. Some even consider it too early to offer it, even though experimental status has been lifted since 2019 by the American Society of Reproductive Medicine. 36 While the notion of a “right to an open future” remains a compelling ethical consideration in pediatric FP, it must also be weighed against more immediate and tangible concerns. In the case of OTC, the procedure itself involves surgical intervention, which is not without risk. These include potential complications from anesthesia and surgery, as well as the significant possibility of reducing the ovarian reserve — potentially by up to 50% — in a young patient who may never face infertility.Reference Karimizadeh 37 Also, some individuals may retain the ability to conceive naturally following cancer treatment, without requiring fertility interventions. Given that the long-term efficacy and future benefit of this procedure remain uncertain, there is a moral tension between acting in the name of preserving future reproductive autonomy and possibly compromising the child’s current health or reproductive potential. Thus, FP must carefully balance the promise of future options, considering the limited evidence of efficacy following OTT in pediatric context — only two reported pregnancies from OTT in young girls — with the concrete risks posed to the child in the present.Reference Emrich 38

Moreover, the majority of Canadian and several French participants have expressed fears and uncertainties regarding the reimplantation of ovarian tissue and the possible introduction of cancer cells and urge caution regarding OTT. Debate in the literature may be explained by the lack of research on the tissue (due to policy restrictions).Reference Lee 39 To preserve fertility in prepubertal girls, OTC must be followed by successful OTT, which enables pregnancy and live birth after long-term tissue storage. However, OTC and OTT are distinct procedures and can be confused and give the misleading impression that OTC alone constitutes a standard FP method. Given that OTT remains experimental, when pediatric oncologists present OTC as a “standard” option, there is a risk that patients and families will later feel misled and disappointed if transplantation fails or does not result in a successful pregnancy. This also raises ethical issues regarding informed consent.

To overcome these uncertainties and promote the right to an open future, policies should encourage and increase funding for research on oncofertility and particularly on OTT, whose results are encouraging, with more and more births to women who have cryopreserved their ovarian tissue when adults. 40 International collaboration and policy development can help share best practices and improve supply standards worldwide. These advances could enable the technique to be offered in centers across Canada. Clarifying which cancer types entail a risk of malignant cell reintroduction would allow pediatric oncologists to refine their recommendations and risk communication in accordance with each patient’s clinical context. Policies should also promote models of care where pediatric oncologists and reproductive specialists can collaborate effectively. These various measures will improve long-term patient outcomes to include future reproductive concern. 41 Hopefully, by the time prepubertal girls grow up, progress will be made to avoid any risk of reintroduction of cancer cells and allow effective, safe reimplantation of ovarian tissue.

3. Social Implications

The offer and coverage of certain interventions may promote certain social attitudes. For example, when parents are offered the FP procedure by OTC, they may feel pressure to preserve their daughter’s fertility. The offer may suggest that it is important for her one day to be a genetic mother.

An analogy can be made with in vitro fertilization (IVF) with donor eggs to medically infertile individuals as each intervention, while medically optional, subtly reinforces the idea that genetic parenthood is a desirable and expected outcome. The clinical offer itself does more than present a medical option. It helps construct a social narrative: preserving or restoring the ability to have genetically related children is a normative goal worth pursuing, often at high emotional, financial, and physical cost.Reference Callan 42 Just as individuals with infertility may feel pressure to pursue IVF to have genetically related offspring, parents offered OTC for their daughters may interpret the offer as a signal that future biological motherhood is an important part of their child’s future identity (as an adult) and well-being. Also, if parents refuse to allow their daughter to undergo OTC, they may be seen as bad parents, as they are closing off the child’s right to have a genetic child and exercise future reproductive autonomy.

It is thus essential to make sure people really do have a choice, and that they also feel free to reject FP. We must not exacerbate the pressure and perception that every woman must become a mother.Reference Roberts 43 Indeed, emphasizing FP sends a strong social message regarding the importance or centrality of genetic motherhood in the lives of women; that supporting the offer of FP is an implicit acknowledgement that without genetic motherhood, a woman’s life is incomplete and she cannot fulfill her potential or her social role. As a component of reproductive health, FP engages fundamental aspects of human identity, including procedural choices and the broader understanding of what it means to be human. In this context, counseling is very important, to give full information to parents (and the girl, according to her age) and make it clear that not proceeding with FP is also an acceptable decision.

Limitations and Strengths

Firstly, the number of Canadian pediatric oncologists did not allow us to reach theoretical saturation for certain themes. The convenience sample reduced the number of Canadian pediatric oncologists participating, but the rich content of the data enabled us to achieve the study objectives. Secondly, the total number of 16 participants and the particularity of the Canadian and French healthcare systems prevent us from comparing the two contexts or generalizing the results. Nevertheless, we were able to obtain rich perspectives from pediatric oncologists on their perceptions of FP, and we were able to confirm several of the survey findings, notably the cost issue. Thirdly, none of the pediatric oncologists working in Quebec were able to participate in this study. This would have enabled us to have the perspective of the only Canadian province where FP by OTC is covered by the public health system. Nevertheless, the participants’ perspectives provided more nuanced results, particularly on the uncertainties surrounding OTT rather than OTC.

Conclusion

The results highlighted the importance of French and Canadian pediatric oncologists’ view of FP for prepubertal girls as an integral component of pediatric oncology care and as a right, which is described in the bioethics literature as the child’s right to an open future. However, policies guiding OTC in Canada involve barriers to access and hence inequity. The fact that it is not offered or covered by the healthcare system (except in Quebec) fails to protect young girls who may experience future infertility as a consequence of their cancer treatment. Offering OTC and covering its costs through the public health system in Canada, as is already the case in France, would guarantee better access to FP for Canadian pediatric patients. The right to an open future also implies that funding should be provided for research to develop OTC and OTT so that the technique can be optimally discussed and offered, without the risk of reintroducing cancer cells. Oncofertility should be considered by policymakers as part of cancer care, and resources allocated accordingly.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Loubna Affdal for the double coding and the peer reviewers for their insightful comments.

Data Availability Statement

The authors confirm that the data supporting this article are available by request.

Ethical Approval and Informed Consent Statements

Participants received written and oral information about the study and how results would be used. They were informed that participation was voluntary, that they could withdraw at any time without any reason, and that data were treated confidentially. All participants provided written consent. The study received ethical approval from the Health Research Ethics Committee (CÉRES) of the Université de Montréal in Canada (#15-131-CERES-D) and from the Comité de Protection des Personnes (CPP) Île-de-France IV at Hôpital Saint-Louis in Paris, France (2016/62NI).

Disclosures

The authors declare no competing interests with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.