Introduction

Following years of declining approval ratings both for his government and for the ruling Liberal Democratic Party (LDP), Prime Minister Fumio Kishida stepped down in August 2024, announcing that he would not be running for re-election in the party's internal leadership contest the following month. Nine candidates secured nominations for the leadership race, a record high, with veteran lawmaker Shigeru Ishiba eventually beating right-wing favourite Sanae Takaichi by a narrow margin. Ishiba almost immediately called a snap election, which was held on 27 October, and sought to assuage voter anger over the LDP's recent financial scandals by withdrawing party nominations and electoral support from lawmakers implicated in the scandals. Despite this, the LDP recorded the second-worst electoral performance in the party's history (after its collapse in 2009, when it lost power entirely), and the LDP/Kōmeitō ruling coalition lost its lower house majority. Deeply divided opposition benches, however – further fragmented by the success of the Democratic Party for the People (DPFP), which surged from seven to 28 seats, and by the election of small numbers of lawmakers from far-right fringe parties Sanseitō and the Japanese Conservative Party – virtually meant that no alternative coalition was possible, allowing Ishiba to continue as Prime Minister with his government ruling as a minority. This was the first minority government in Japan in 30 years since 1995.

Election report

A general election for the lower house of the National Diet was held on 27 October 2024 (extensively covered by national media; see Asahi Shimbun Online Newspaper Database 2024, Mainichi Shimbun Online Newspaper Database 2024, Yomiuri Shimbun Online Newspaper Database 2024). Prior to this election, on 28 April, four by-elections were held in districts whose representatives had resigned or passed away in the prior months – Tokyo 15th district, Nagasaki 3rd district, Shimane 1st district (all lower house) and the Iwate at-large district (upper house). These by-elections were widely framed as a bellwether for the lower house election that was expected to be called before the end of the year. All four of the seats – including three that LDP lawmakers had formerly held – were won by the mainstream opposition Constitutional Democratic Party (CDP), confirming the LDP's polling slide while quelling speculation that the CDP had lost its momentum to other opposition groups such as the Japan Innovation Party (JIP).

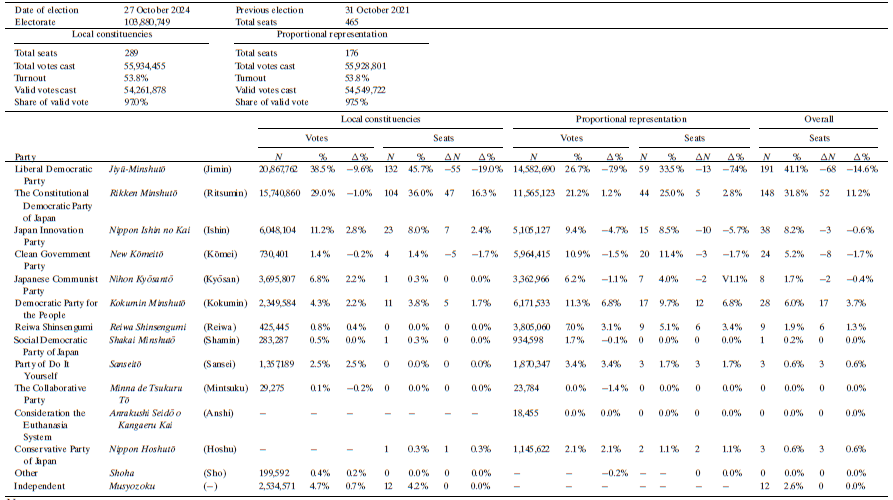

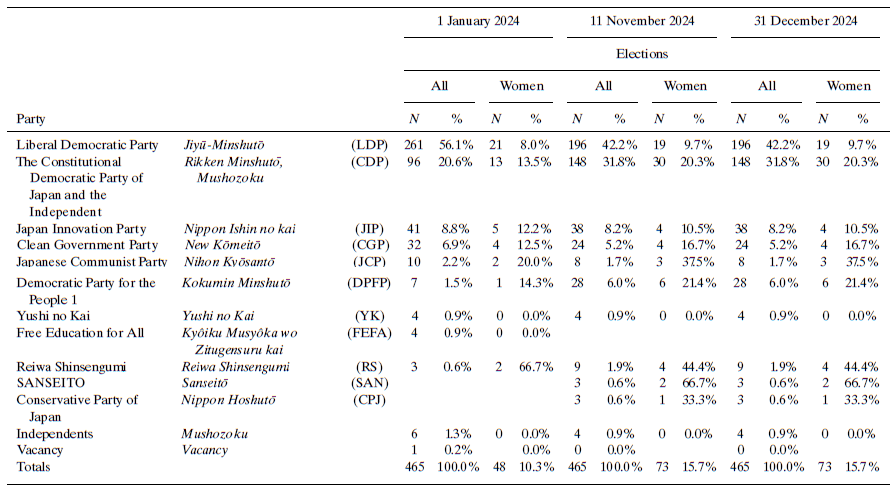

In the 27 October general election, the LDP lost 56 seats, leaving it with 191 seats in the lower house – far short of the 233 required for a single-party majority (Table 1). Its junior coalition partner, the Clean Government Party (Kōmeitō), also lost eight seats, leaving the coalition without a majority. Twelve former LDP lawmakers were also forced to run without the party's nomination after support was withdrawn due to their complicity in financial scandals; eight of them lost their seats, while the remaining four were re-elected as independents. The biggest winner from the election, on paper, was the CDP, which won 50 seats to bring its total to 148 – the best result in its history and the highest seat count for an opposition party since the 2009 electoral victory of its predecessor, the Democratic Party of Japan. Far more attention, however, was focused on the success of the DPFP, which massively increased its seats from seven pre-election to 28 post-election – granting the party significant leverage over policymaking in the subsequent Diet session in return for supporting the LDP and Kōmeitō’s minority administration (see Hino & Ogawa Reference Hino and Ogawa2019, for the birth of the DPFP). Please see the Issues in National Politics section below for the involvement of the DPFP in policy-making within the minority government.

Table 1. Elections to the lower house of Parliament (House of Representatives/Shūgiin) in Japan in 2024

Notes:

The Conservative Party of Japan (Nippon Hoshutō) listed here refers to the party led by Naoki Hyakuta, formally established on 17 October 2023. It should not be confused with an earlier and unrelated party of the same name founded in 2021.

Source: Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications (2024).

Two further elections held in 2024 merit mentioning, although they were regional rather than national contests. The Tokyo Gubernatorial Election was held on 7 July and saw incumbent governor Yuriko Koike returned for a third term by a large margin. However, the main opposition candidate, veteran Tokyo lawmaker and former Democratic Party leader Renhō, was pushed into third place by independent candidate Shinji Ishimaru, who based his campaign largely on his extensive social media presence. On 17 November, Hyogo prefecture held a gubernatorial election to replace Motohiko Saitō, who was removed from office following a unanimous vote of no confidence in the prefectural assembly following allegations of workplace bullying resulting in the suicide of a staff member. Saitō ran for re-election, campaigning extensively through social media and making conspiratorial claims that the bullying allegations had been invented by the media and shady ‘elites’ who opposed his reform agenda into a central plank of his messaging. He was re-elected in a landslide victory, winning more votes than he had when he was originally elected for office. Following this election, many media outlets and political figures voiced concerns about the spread of online misinformation around political campaigns. The growing concerns about new styles of election campaigns have led the government to discuss reforming the Public Office Election Law, including regulating the use of publicly subsidised election poster bulletin boards, which was highly problematised in the Tokyo gubernatorial election, and regulating social media for disinformation, which turned out to be a major issue in the Hyogo prefectural gubernatorial election.

Cabinet report

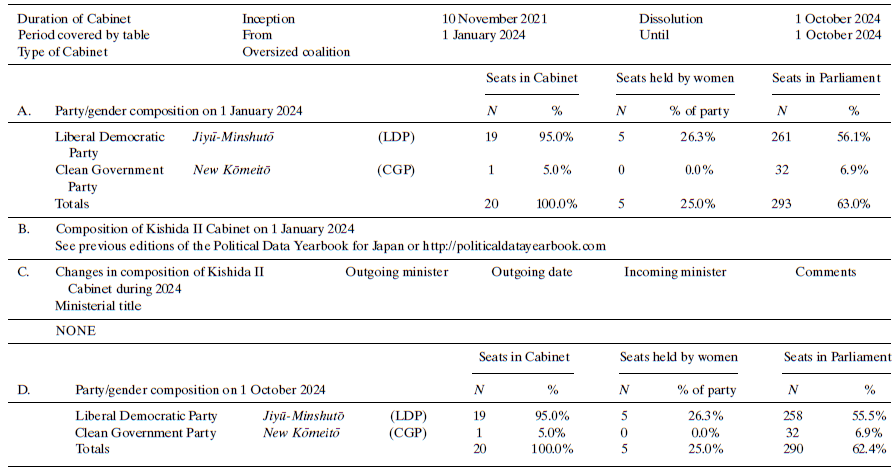

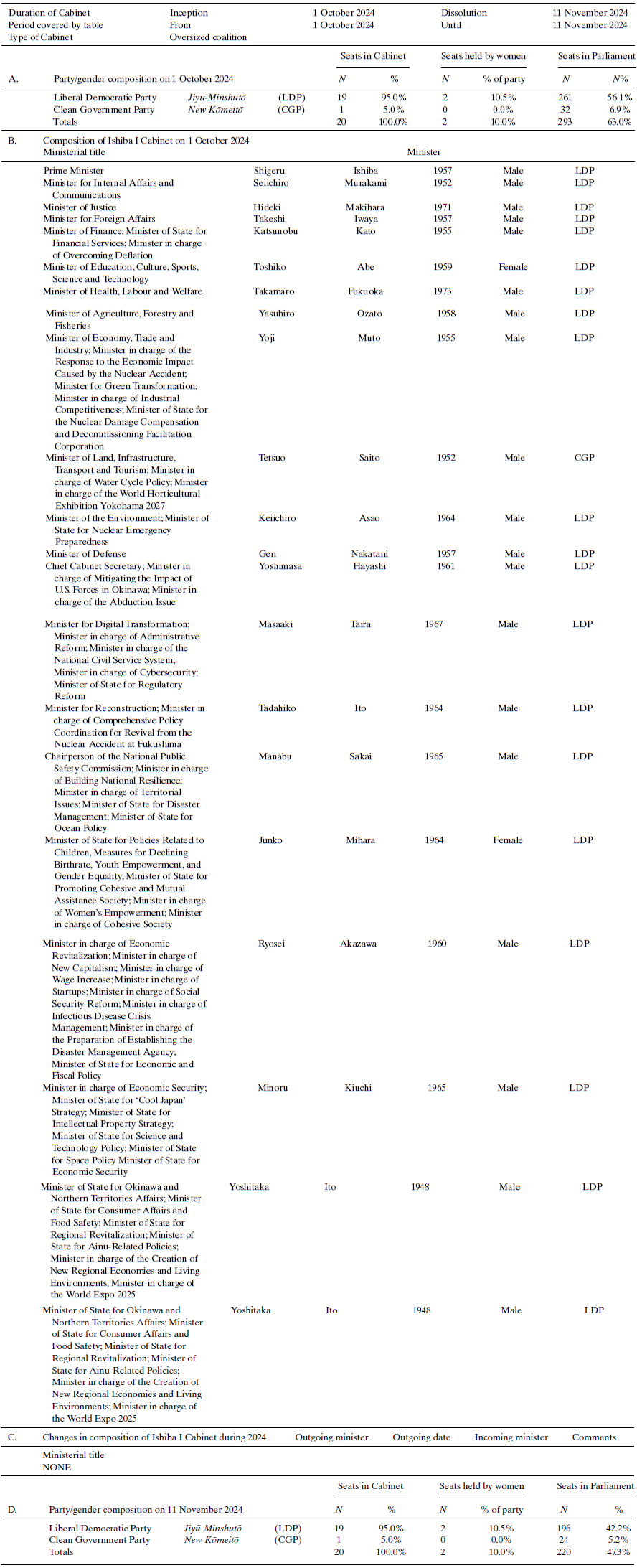

On 1 October, Shigeru Ishiba announced the composition of his first Cabinet as Prime Minister. The most notable feature of his Cabinet choices was the conspicuous absence of any members of the former Abe faction, which had been disbanded due to its complicity in the previous year's financial scandals. It was reported that Ishiba, perhaps mindful of the risks of further deepening rifts in the party by excluding Abe faction members from all key roles, had offered a party executive position to defeated leadership candidate Sanae Takaichi, a former Abe faction member, but she declined the offer.

Aside from the omission of Abe faction-affiliated members, Ishiba's first Cabinet largely seemed to aim at striking a balance between experienced ministers and newcomers. Seven members of the Cabinet were veteran ministers, including several of the most senior roles – such as five-times Cabinet minister Yoshimasa Hayashi as Chief Cabinet Secretary, former Minister of Health, Labour and Welfare Katsunobu Katō as Minister of Finance, the return of former Minister of Defense Gen Nakatani to the Defense Ministry and the appointment of another former Minister of Defense, Takeshi Iwaya, as Minister of Foreign Affairs. The remaining 13 positions were filled by new appointees. Only two members of the new Cabinet were women; Toshiko Abe was appointed as Minister of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, while Junko Mihara took on a number of concurrent ministerial roles related to policies around children, declining birthrate and gender equality.

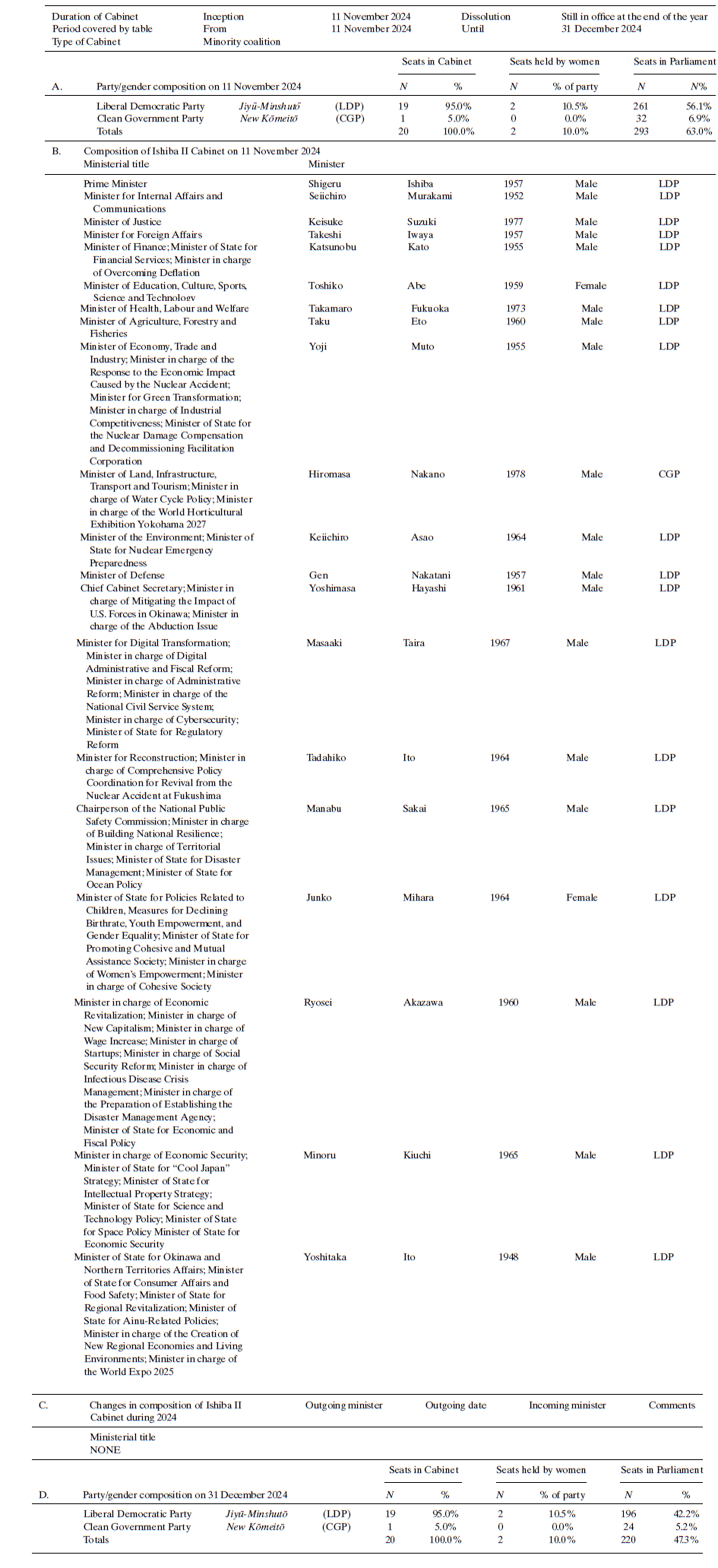

The first Ishiba Cabinet lasted for only 41 days before a reshuffle prompted by seat losses in the 27 October election. Minister of Justice Hideki Makihara lost his seat in the election and was replaced by Cabinet newcomer Keisuke Suzuki (LDP); Minister of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries Yasuhiro Ozato also lost his seat and was replaced by Taku Etō (LDP), who had previously held the same ministry from 2019 to 2020. The Cabinet's sole member from the junior coalition partner Kōmeitō, Minister of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism Tetsuo Saitō also left his position in this reshuffle; he was chosen to lead the party after former leader Keiichi Ishii lost his seat in the election and passed the Cabinet role to newcomer Hiromasa Nakano. With none of the newly appointed ministers being former Abe faction members, 2024 concluded without any lawmaker affiliated with the faction being a member of the Cabinet since December 2023.

Cabinet changes and composition in the outgoing Kishida II and the Ishiba I and II are shown in Tables 2, 3 and 4, respectively.

Parliament report

In the ordinary session that ran from 26 January to 23 June, 61 of the 62 government-sponsored bills submitted to the Diet passed; the final bill, related to the development of maritime renewable energy resources, was carried forward to the extraordinary session later in the year and ultimately rejected (Cabinet Legislation Bureau 2024). Sixty-eight bills were passed in total, including seven legislator-sponsored bills. Among the bills passed were several related to renewable energy and environmental concerns, as well as some amendments to bills on immigration and refugees, with the latter being in part a response to concerns that had been raised over the treatment of foreign labourers who entered Japan under the technical internship program. One of the final bills passed in the ordinary session was the Smartphone Competition Promotion Law, which addressed concerns about monopolistic behaviour by smartphone platform holders by forbidding them from giving preferential treatment to their own software and requiring transparency about fees and commissions.

Three motions of no confidence were submitted by members of the CDP – one against Minister of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology Masahito Moriyama on 19 February and one against Finance Minister Shunichi Suzuki on 1 March, as well as one against the Kishida Cabinet on 20 June – with all being defeated. During this session, the Diet also adopted a cross-party resolution calling for an improvement to humanitarian conditions in Gaza and a rapid ceasefire in the Israel–Palestine conflict. The budget for fiscal 2024 was passed on 29 March and came in at 112.5 trillion yen, down slightly from the prior year but still the second-highest annual budget on record. This was added to by a 13.9 trillion yen supplemental budget, which passed in November, containing spending earmarked to support wage growth. This was further increased by a 13.2 trillion yen supplemental budget passed in November, most of which was earmarked for measures related to economic growth and tackling rising consumer prices.

A brief extraordinary session of the Diet ran from 1 to 9 October, confirming Shigeru Ishiba as the new Prime Minister before being dissolved for the lower house election. No legislation was passed in this session. Another brief extraordinary session ran from 11 to 14 November to reappoint Ishiba and his reshuffled Cabinet, before a more lengthy extraordinary session was convened from 28 November to 21 December. In this session, nine out of nine government-sponsored bills were passed, along with seven lawmaker-submitted bills (mostly dealing with the regulation of political funds and expenditures in the wake of the LDP's financial scandals), for a total of 16 bills passed in total. With the LDP--Kōmeitō coalition governing as a minority, bills in this session required agreement from opposition parties to pass, and the session was largely characterised by negotiations among parties to this end – including a revision to the supplementary budget to take into account concerns from the CDP, marking the first time since the 1990s that the LDP revised its budget proposals in response to opposition feedback. Marking this cooperative mood, the opposition parties forewent the tradition of submitting a motion of no confidence against the Cabinet at the end of the session.

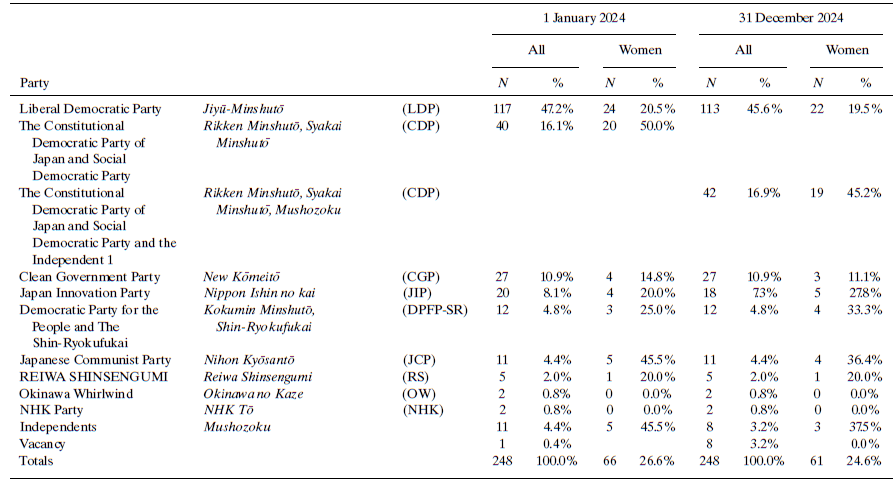

Tables 5 and 6 show the composition of both houses of Parliament in 2024.

Table 5. Party and gender composition of the lower house of Parliament (House of Representatives/Shūgiin) in Japan in 2024

Political party report

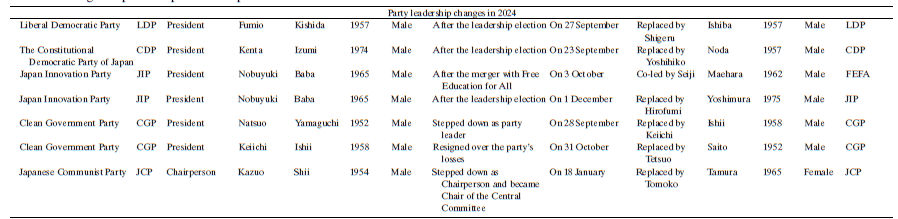

Changes in political parties are shown in Table 7.

Table 7. Changes in political parties in Japan in 2024

Source: The Asahi Shimbun Online Newspaper Database (2024).

Both the LDP and CDP changed their leadership in 2024. The CDP elected a new leader on 23 September, with the party opting for former Prime Minister Yoshihiko Noda (2011–2012) to replace the incumbent Kenta Izumi. Although Izumi ran for re-election, there was widespread dissatisfaction within the party at his seeming inability to capitalise upon the LDP's collapsing poll numbers. Noda defeated Izumi and two other challengers – former party leader Yukio Edano and relative newcomer Harumi Yoshida – to win the leadership. A few days later, on 27 September, the LDP voted to replace outgoing leader Fumio Kishida – who did not run for re-election – with veteran lawmaker Shigeru Ishiba. The fragmentation of the LDP in the wake of the dissolution of most of the party's major factions was apparent in this election; nine candidates stood for the leadership, and former faction leaders seemed to struggle to whip votes for their preferred candidates. Ishiba ultimately defeated right-wing lawmaker Sanae Takaichi in a close run-off race to become the country's next Prime Minister.

Other changes to political parties also occurred within smaller parties. Free Education for All, the breakaway party of former DPFP lawmakers formed by Seiji Maehara in 2023, merged into the JIP ahead of the October general election, with Maehara becoming co-leader of JIP two months later. Meanwhile, the ongoing dispute over the leadership of The Collaborative Party (Mintsuku), formerly known as Party to Protect the People from NHK (Japan Broadcasting Corporation), a right-wing populist party (see Hino & Ogawa Reference Hino and Ogawa2020), was seemingly resolved by former leader Takashi Tachibana opting to create a new party using the original name (Party to Protect the People from NHK), leaving Mintsuku under the leadership of Ayaka Otsu.

Issues in national politics

The LDP-led coalition government was dogged by low levels of public support in opinion polls throughout the year, a continuation of the decline in popularity that had been fuelled by successive scandals throughout 2022 and 2023 (see Hino et al. Reference Hino, Ogawa, Fahey and Liu2023, Reference Hino, Ogawa, Fahey and Liu2024). By August, Prime Minister Kishida had decided not to stand for a second term as party leader; the LDP's subsequent election of Shigeru Ishiba, who had been something of an outsider within the party due to his vocal opposition to the policies and ideologies of Shinzo Abe's administration (2012–2020), can largely be seen as an attempt to present the public with a ‘clean pair of hands’ who could successfully break away from the scandals that had dogged the Kishida administration. Ishiba's instalment as leader and his subsequent decision to withhold party nominations and support from lawmakers implicated in financial scandals were not enough to save the LDP's majority, however, and Cabinet support levels continued to be low in most polls until the end of the year (albeit higher than they had been by the end of Kishida's tenure).

Despite the desire of some LDP lawmakers to draw a line under the scandals, political funding and corruption remained a key issue during the extraordinary session of the Diet in November and December, with the LDP and opposition parties negotiating over a series of reforms aimed at improving the transparency of political funding and expenditures. While the CDP and others pushed for a complete ban on political donations from corporations and other groups, there was no consensus on this issue on the opposition benches (not least since the DPFP, in particular, is supported by trade unions whose donations would be banned under such a rule), and the LDP was able to negotiate the removal of this aspect of the legislation.

Although consumer price inflation cooled slightly in 2024 – dropping to 2.74 per cent from the record high of 3.1 per cent set in the previous year – this remained well above the average inflation for most of the past few decades, with the impact on consumer prices being compounded by the yen continuing to weaken against the US dollar, even briefly rising above 160 yen to the US dollar in June – marking the weakest that the currency has been since the 1980s. Consequently, economic anxieties dominated many citizens’ priorities. The DPFP capitalised upon these concerns in its election campaign, focusing on pocketbook issues for households and low-income earners, as well as more controversially suggesting that the country's social insurance systems are set up to benefit elderly groups at the expense of younger cohorts. The party's signature policy was to demand a change in the so-called ‘1.03m Yen Wall’, a step change point in the taxation system, which, it claimed, discouraged many low-income earners from working more hours or seeking better pay. With the LDP in minority government following the election, the DPFP made an increase to this income tax threshold into a condition of its support for legislation and was able to secure a commitment to change the tax code to this effect.

Japan's security environment continued to be an ongoing background concern throughout 2024, with tensions rising with both China and Russia. A record number of Chinese government vessels entered the contiguous zone around the Japan-administered (albeit disputed) Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands during the year, with a Chinese reconnaissance plane also entering Japanese airspace near southern Japan in August; in the north, meanwhile, Russian military aircraft made incursions into Japanese airspace three times in September, with Japanese fighter jets being launched to intercept them. A new defence budget was approved in December, rising 9.4 per cent to a record 8.7 trillion yen, although some analysts noted that the weakening of the yen against the US dollar would lessen the impact of the budget by making US weapons purchases more expensive.