Social progress at the expense of economic equality?

In the heated debate(s) about the ‘ideological failures of the egalitarian coalition’ (Piketty, Reference Piketty2022, p. 40) and economic inequality, a prominent yet untested assumption emerges: the Left, once the advocate of material levelling and economic equality, is said to have forsaken these old core principles. Instead of levelling, left parties purportedly focus on the equal rights of minority groups as well as equal chances and merit (Eribon, Reference Eribon2009; Fraser, Reference Fraser2017; Piketty, Reference Piketty2020; Sandel, Reference Sandel2020). Unsurprisingly, numerous fair critiques against such claims were levelled, criticizing an overtly holistic conception of ‘the Left’, inadequate scholarly engagement with classic work on Social Democracy, and a neglect of previous work on educational cleavages and realignment (Abou‐Chadi & Hix, Reference Abou‐Chadi and Hix2021; Rovny, Reference Rovny2019). Yet, these critiques are focusing at the electoral demand side rather than programmatic supply, and, owing to the absence of fine‐grained data on left parties’ stances regarding (in)equality (Häusermann & Kitschelt, Reference Häusermann and Kitschelt2023; Pontusson & Rueda, Reference Pontusson and Rueda2010; Rueda, Reference Rueda2008; Tavits & Potter, Reference Tavits and Potter2015), the potential for a crowding out of material equality has remained untested. Introducing new data on left parties’ concepts of equality, in this research note we seek to set the record straight and probe into the extent to which left parties have traded off economic equality against equal rights or equal chances (at the program level) – for instance, to adjust and appeal to increasingly affluent and educated new support groups.

In his influential description of the ‘Brahmanized’ Left, Piketty (Reference Piketty2020, pp. 882‐835) points out that ‘improving the lot of the disadvantaged ceased to be [the] main [left] focus’, criticizing that this growing concern with equal rights has been harming material equality. Sandel (Reference Sandel2020), putting forth a critique of the Left's meritocratic turn, deplores that the Left is complicit in establishing a tyranny of merit, as expressed in slogans such as Bill Clinton's couplet ‘What you earn depends on what you learn’. Fraser, who argues that in order to foster equality parties must promote equal rights and equality of outcome, blames progressive neoliberalism for ‘talking the talk of diversity, multiculturalism, and women's rights, even while preparing to walk the walk of Goldman Sachs’, for a ‘neoliberal politics of redistribution’ that helped to create the void since exploited by populists like Trump (Fraser, Reference Fraser2017, p. 6).

Whether or not equal rights or equal chances are regarded as new focal points, both critiques point to a departure from the traditional focus of the Left on redistribution. Notwithstanding differences between these critiques, the politically potent charge is not merely that left parties have shifted attention away from economic equality to focus more on equal chances or equal rights. Rather, that a crowding out (or displacement) has taken place in which left parties increasingly emphasize equal rights at the expense of economic levelling. This shift can be considered a manifestation of a meritocratic or emancipatory turn. Importantly, neither we nor the authors we discussed regard rights and redistribution as inherently (i.e., per se) antithetical.

Yet, thus far, given the absence of fine‐grained data on (left) parties’ preferences on redistribution or equality more broadly, it has not been possible to assess the extent to which a turn towards rights‐ or chance‐based concepts of equality has taken place. In lieu of such data, scholars who want to study left parties and equality had to resort to (too) broad left‐right or economic indices (Pontusson & Rueda, Reference Pontusson and Rueda2010; Tavits & Potter, Reference Tavits and Potter2015), based on the manifesto project (MARPOR, Volkens et al., Reference Volkens, Burst, Krause, Lehmann, Matthieß, Regel, Weßels and Zehnter2021). Such broad indices conflate economic equality, equal chances, and equal rights – the very dimensions of equality we must distinguish to assess whether the Left has indeed pivoted away from economic equality to equal chances or equal rights. To illustrate this: while the following statements related to equality (from the United Kingdom) are conflated in existing left‐right, economic or equality measures based on MARPOR, we can distinguish between

Economic equality: ‘Labour will introduce a tax on wealth above £100,000’. (1974);

Equal chances: ‘The Conservatives are threatening to undermine opportunity by ending student bursaries, freezing the repayment threshold and raising the level of fees’. (2017); and

Equal rights: ‘Labour stands with people from ethnic minority backgrounds’. (2019)

Based on new data on the egalitarian trajectories of left parties in 12 OECD countriesFootnote 1 from 1970 to 2020 we first map these different equality concepts over time and across left party families. In the second step, we examine whether left parties’ trade‐off different equality concepts. To this end, we use a measure of directional proportionality (Lovell et al., Reference Lovell, Pawlowsky‐Glahn, Egozcue, Marguerat and Bähler2015) that mitigates the spurious negative correlations inherent to compositional data, such as relative emphases. Thirdly, taking the limited indications for trade‐offs between economic equality and equal rights as our point of departure, we assess the direction of this trade‐off.

Besides echoing the widely shared view that disregarding party families is misleading (as Rovny, Reference Rovny2019 or Abou‐Chadi & Hix, Reference Abou‐Chadi and Hix2021 pointed out vis‐à‐vis Piketty, Reference Piketty2020,Footnote 2 cf. Zohlnhöfer, Reference Zohlnhöfer2023), our new data allows us to establish two new and important results; we show that general claims of a meritocratic or emancipatory turn at the expense of economic equality are wrong: trade‐offs at the expense of economic equality are rare. On the other hand, social democratic parties did indeed move away from a complementary relationship between economic‐ and rights‐based conceptions of equality and showed signs of trade‐offs after the year 2000. Our results add an empirical basis and nuance to the heated debate about the alleged emancipatory/’woke’ or meritocratic turn of the Left – a public and academic debate in which strong preconceptions and claims contrast with weak data.

Data collection: Crowd‐coding of equality concepts

To overcome the conflation of different equality concepts and to test the crowding out claim, we introduce a new dataset, which enables us to track the egalitarian trajectories of left parties in 12 OECD countries from 1970 to 2020. While the country selection was partly driven by language expertise (Danish, English, French, German and Swedish), we ensured broad coverage and, thus, representativeness of different welfare state regimes. Furthermore, the time frame of our study allows us to explore equality emphases after the end of the golden age of modern welfare states. However, we would caution against the extrapolation of our findings to other country clusters, such as Mediterranean countries or Eastern Europe.

We use online crowd‐coding (Benoit et al., Reference Benoit, Conway, Lauderdale, Laver and Mikhaylov2016) to decipher the emphasis on three equality concepts at the heart of the debate: economic equality, equal chances and equal rights. Crowd‐coding refers to the online‐collection or annotation of data using multiple judgements from lay coders, which combines the efficiencies from fully automated approaches with the deep contextual understanding of humans and, thus, can be used to scale expert knowledge for tasks that require contextual interpretation (Benoit et al., Reference Benoit, Conway, Lauderdale, Laver and Mikhaylov2016; Haselmayer & Jenny, Reference Haselmayer and Jenny2017; Horn, Reference Horn2019; Lehmann & Zobel, Reference Lehmann and Zobel2018). Low costs, speed, replicability and (content) validity render crowd‐coding an ideal tool for our large number of statements and in light of the relatively complex categorization task (ibid). We use crowd‐coding to gather data on parties’ positive references to economic equality, equal chances and equal rights. We are also able to distinguish these core categories from statements that are – even when the context statements are factored in – vague (‘We are the party of equality’) or pertain to a residual (i.e., marginal or idiosyncratic) equality concept, such as climate equality. However, we integrate crowd‐coding with computational text analysis to reduce the workload and costs of ‘humans in the loop’, while simultaneously retaining the (still unmatched) human capability for deep processing of (even latent) semantic nuances.

The elicitation of parties’ equality concepts relies on their manifestos that are regularly published in advance of national elections. In those documents, parties state their goals and vision for the future, which render them a suitable foundation to measure their focus on and understanding of equality. While it would be interesting to look at statements in the media, too, manifestos are the most authoritative and comparable source and their content is reflected in the media (Merz, Reference Merz2017). Across the 12 OECD countries we study, we collected 965 party manifestos. 544 of those were retrieved from the popular Manifesto Project (MARPOR) database via their API. The remaining documents were collected manually from different sources such as (online) archives and libraries. For each election, based on a crowd‐coded corpus of 300,000 quasi‐sentences from party programs, we quantify the share of positive references to these concepts of equality. Economic equality entails statements that criticize economic inequality and/or favour economic equality and redistribution. Equal chances captures statements aimed at social mobility irrespective of social background. Equal rights statements are those that address discrimination of (ethnic, sex, gender) minority groups (details in the following section). To illustrate this, 60 examples for the categories can be found in the online Appendix D.

The precise data collection pipeline looks as follows. First, we use a sequential binary classifier, trained on available MARPOR data, to splice the manifestos’ raw text into quasi‐sentences. Subsequently, we used a regular expression to identify quasi‐sentences, that might have been mis‐segmented, which were forwarded to research assistants to check and, if necessary, revise the segmented quasi‐sentences. This process essentially segmented all party manifestos into 300,000 quasi‐sentences. Secondly, we use another binary classifier to identify statements that likely concern (in)equality broadly conceived. The classifier was trained on MARPOR data to detect statements that reference positive mentions of equality (category 503). Importantly, the hyperparameters of the classifier were fine‐tuned to reliably identify most relevant statements at the expense of many false positives, that is, we prioritized recall over precision. This reduction process left us with about 33,000 quasi‐sentences that speak to equality and social justice, which considerably decreases the workload for and costs of human coders downstream. Third, we forwarded those retained statements to crowd‐coders on Amazon Mechanical Turk (we tested several platforms), a platform that has been successfully used for collecting data in previous research (Berinsky et al., Reference Berinsky, Huber and Lenz2012; Sumner et al., Reference Sumner, Farris and Holman2020; Skytte, Reference Skytte2022). The codings were collected in the spring of 2022. After having read a short instruction and having passed a qualification test, coders were presented individual statements and some context and asked to judge whether they include a positive reference to equality and equal treatment and if so, which of the specific categories applies.Footnote 3 Building on previous research (Horn, Reference Horn2019) and our own pre‐tests, we collected five coding decisions per unit, yielding a total of 168,000 crowd‐coding decisions. This ensures that aggregated results align with expert ratings while enabling fast data collection at reasonable costs. To warrant fair coder‐remuneration, we made sure our workers were able to attain local minimum wages.Footnote 4 Fourth, we aggregated individual codes based on a simple majority vote. This approach reflects the general idea of the ‘wisdom of the crowd’ and is anchored in social choice theory (e.g., de Condorcet, Reference De Condorcet1785). We obtain a good agreement between the crowd's judgement and the three senior experts based on 1,423 unanimously coded units, even at the sentence level (see online Appendix Figure A1): The average Krippendorff's alpha is 0.72, which demonstrates reasonably good agreement even by conventional standards of quantitative content analysis. The online Appendix provides a graphical presentation of coder agreement and shows that we obtained good levels of validity across countries with alpha values ranging between 0.6 (New Zealand) and 0.85 (see online Appendix Figure A1, Table A4), which shows that the crowd was able to replicate our unanimous expert judgements.

Analysis: From trajectories to trade‐offs

This research note focuses on left parties’ equality concepts. If we compare the average salience of equality concepts per party family based on t‐tests of mean differences (online Appendix Table B1), we see the great(er) heterogeneity of left parties. For the Left, party families matter (cf. Zohlnhöfer, Reference Zohlnhöfer2023). Thus, we disaggregate the Left into three party families following MARPOR: ecological or green, social democratic (including the US‐Democrats) and communist/socialist parties.

Trajectories: left parties over time

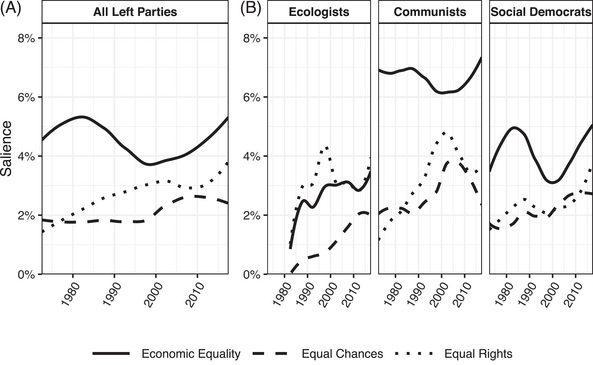

The importance of distinguishing parties’ equality concepts becomes apparent in Figure 1, which tracks the relative (to the statements included in the manifesto) emphasis parties put on each equality concept per election. Panel A shows the patterns across all left parties. Instead of aligned co‐movements, our data reveals countervailing trends: emphasis on economic equality has neither increased nor decreased but follows a U‐shaped trajectory. While positive references to equal rights have doubled, equal chances rhetoric has increased moderately, especially since the mid‐1990s.

Figure 1. Development of parties’ focus on equality, 1970–2020. The different lines represent three different concepts of equality. The panels in the figure are based on MARPOR (green, communist and social democratic).

Panel B helps to qualify this aggregated result for ‘the Left’. Since the end of the Cold War, increasingly marginal communist/socialist parties have reduced their emphasis on economic equality, while simultaneously ramping up their equal chances and equal rights rhetoric. After 2000, this pattern has reversed. While economic equality has been reemphasized in response to the window of opportunity that opened during Social Democracy's turn towards the ‘Third Way’ (e.g., Green‐Pedersen & van Kersbergen, Reference Green‐Pedersen and Van Kersbergen2002), emphasis on equal rights has been dwindling. The focus of communist parties remains on redistribution.

Ecological parties, which entered party systems in the 1980s, exhibit a different trajectory. Often rooted in the civil‐, ecological‐ and minority‐rights movements, they have consistently prioritized equal rights of groups over economic equality and equal chances. Though these new left parties increasingly address both aspects, equal rights concerns remain dominant.

The Social Democrats’ emphasis on economic equality first peaked in the mid‐1980s, just before Social‐Democratic parties began de‐emphasizing equal outcomes, following what became known as the ‘Third Way’ (Giddens, Reference Giddens1994). The low point was reached around 2000, when the Social Democrats focused less on economic equality than ecological parties. Equal chances rhetoric gained traction in the 1990s. Equal rights became a key concern from the mid‐2000s onwards. Yet, overall, all this did not come at the expense of economic equality. Rather, the focus on rights was paralleled by a renaissance of economic equality concerns.

These findings help us put the results in Panel A in perspective. First, the drop in emphasis on economic equality is partly driven by the moderation and disillusionment of some Eurocommunist parties, which abandoned Marxism‐Leninism as its ideology post 1990 in countries such as France. Second, given the late entry into party systems of some ecological parties, the results cannot be reduced to party change but also reflect party system change. Finally, the result that the left has undergone a re‐traditionalization, indicated by an uptick in economic equality, is driven by the old left parties, and particularly the Social Democrats.

Economic equality and equal rights: Competitors or complements?

So far, we have mapped the development of different equality concepts independently both over time and over families of political parties. However, arguments for the meritocratic turn and the ‘woke’ or progressive neoliberal left suggest that the salience of equality concepts is interlinked in trade‐off relationships. These trade‐offs stem from the fact that political parties’ attention to individual policy topics is not unlimited (Jones & Baumgartner, Reference Jones and Baumgartner2005). While they can choose to publish on certain policy matters to a varying degree, more volume does not necessarily mean more positive emphasis. Rather, additional statements on equal rights policies are easily offset and blurred by similarly lengthy treatments of economic equality. Therefore, the positive emphasis on individual equality concepts can neither be understood nor modelled in isolation. Technically speaking, it is compositional, that is, non‐negative data that predominantly carries relative information. The problem with such data is that conventional statistical methods produce spurious, negative correlations among the individual compositions (Pearson, Reference Pearson1896). However, as such data is common in many disciplines – ecology, chemistry, geology, but also public policy when it comes to the analysis of public budgets (Adolph et al., Reference Adolph, Breunig and Koski2020; Lipsmeyer et al., Reference Lipsmeyer, Philips, Rutherford and Whitten2019; Philips et al., Reference Philips, Rutherford and Whitten2016; Yu et al., Reference Yu, Jennings and Butler2019) – statisticians have developed a toolkit of methods to produce reliable measures of correlational associations among the individual components (Greenacre, Reference Greenacre2021). We rely on a measure of directional proportionality (![]() ) developed by Lovell et al. (Reference Lovell, Pawlowsky‐Glahn, Egozcue, Marguerat and Bähler2015) that eliminates the spurious ‘negative drift’ conventional correlation measures would produce if applied to compositional data. Hence, our measure of directional proportionality is better suited in the context of this study as it allows for a more accurate representation of the relative importance of different equality concepts within a fixed total, capturing the inherent trade‐offs between them. Therefore, compositional measures provide both a more realistic and more conservative exploration of whether different equality concepts are in fact competitors or complements. The measure ranges from ‐1 (perfect reciprocity) to 1 (perfect proportionality) and is defined as follows:Footnote 5

) developed by Lovell et al. (Reference Lovell, Pawlowsky‐Glahn, Egozcue, Marguerat and Bähler2015) that eliminates the spurious ‘negative drift’ conventional correlation measures would produce if applied to compositional data. Hence, our measure of directional proportionality is better suited in the context of this study as it allows for a more accurate representation of the relative importance of different equality concepts within a fixed total, capturing the inherent trade‐offs between them. Therefore, compositional measures provide both a more realistic and more conservative exploration of whether different equality concepts are in fact competitors or complements. The measure ranges from ‐1 (perfect reciprocity) to 1 (perfect proportionality) and is defined as follows:Footnote 5

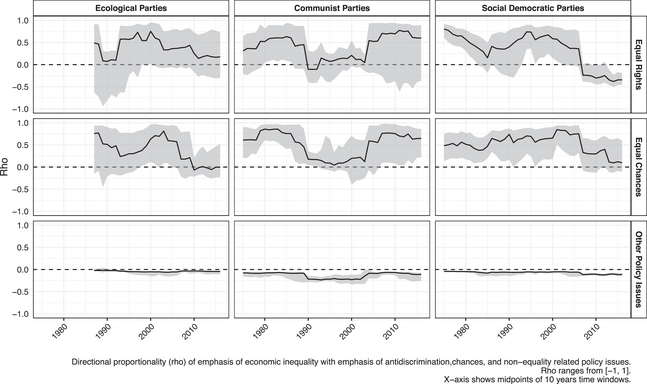

Figure 2 shows the statistical association between parties’ emphasis on economic equality with equal chances, equal rights and a residual category of other policy issues. A positive value of ![]() indicates a proportionality relationship between economic equality and the policy issues denoted on the y‐axis, whereas a negative value of

indicates a proportionality relationship between economic equality and the policy issues denoted on the y‐axis, whereas a negative value of ![]() represents reciprocity. Hence, positive values mean that parties tend to emphasise both issues in tandem, whereas negative values are indicative of trade‐offs. Since we are interested in the overall trend of the relationship among the different equality concepts, we calculate

represents reciprocity. Hence, positive values mean that parties tend to emphasise both issues in tandem, whereas negative values are indicative of trade‐offs. Since we are interested in the overall trend of the relationship among the different equality concepts, we calculate ![]() for 10‐year moving windows to mute country‐specific effects generated by unaligned election cycles.Footnote 6 Bootstrapping 1,000 samples per 10‐year window, we also estimate the uncertainty of the calculated association, which is represented by the grey area around the median trend line.Footnote 7

for 10‐year moving windows to mute country‐specific effects generated by unaligned election cycles.Footnote 6 Bootstrapping 1,000 samples per 10‐year window, we also estimate the uncertainty of the calculated association, which is represented by the grey area around the median trend line.Footnote 7

Figure 2. Directional proportionality of emphasis on economic equality with emphasis on equal chances, equal rights, and non‐equality related policy issues. X‐axis shows midpoints of 10‐year windows. Figure based on 1000 sample bootstraps per time window. Solid line shows median, grey areas represent 95% confidence intervals.

For most of the past 50 years, emphasis on different equality concepts has been complementary, meaning that parties have tended to embrace an encompassing notion of equality, which they contrasted with other policy issues. This tendency is also present within individual party families – Social Democrats, Communist parties and Ecological parties – as the columns in Figure 2 show. However, there are two crucial non‐complementary periods concerning Communist parties and Social‐Democratic parties. First, for 10 years after the fall of communism, communist parties abandoned the complementarity of economic equality, equal chances and equal rights. From the early 2000s on, they returned to a holistic (i.e., complementary) egalitarian approach and the equality concepts moved in tandem again.

The other non‐complementary period (in Figure 2) concerns Social Democracy. It illustrates why the aggregate trends in Figure 1 can be misleading and warrant further discussion. After having simultaneously stressed different aspects of equality for 30 years, this co‐movement came to an end in the early 2000s, when the relationship between social‐democratic appeals to economic equality and equal rights waned and eventually reversed from strong complementarity to a weak, yet significant trade‐off. Equal rights and economic equality are no longer conceived of as two aspects of the same quest for equality, but rather as two different concepts. With the rise of the ‘Third Way’, Social Democratic parties that choose to highlight equal rights tend to scale back on equal economic outcomes – and vice versa.

While this speaks to the question of the section title, competitors or complements, Figure 2 lacks directional information on the trade‐off between economic equality and equal rights. It indicates that Social Democratic parties no longer view them as complementary. But to what extent do equal rights references come at the expense of economic equality, not vice versa?

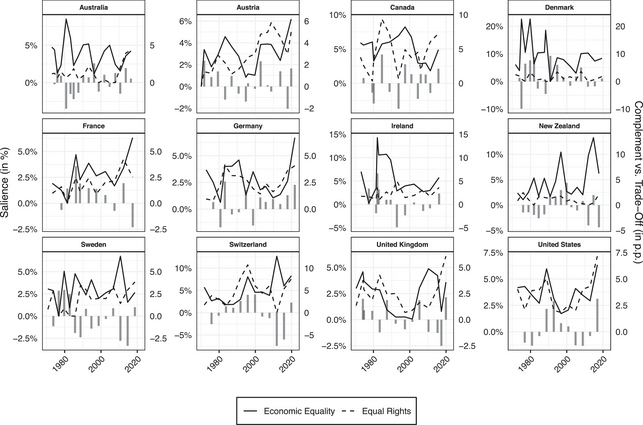

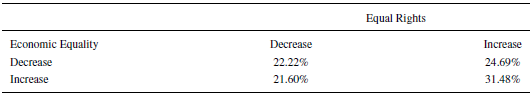

Although it is often argued that left parties' emphasis on equal rights comes at the expense of economic equality (Fraser, Reference Fraser2017; Piketty, Reference Piketty2020), even more so in the political discourse, our data does not support this generalization (though we visually identify cases where this is the case in Figure 3). Cross‐tabulating the possible combinations of increasing and decreasing appeals to economic equality and equal rights (Table 1), the off‐diagonal elements show that in almost 50% of all observed ‘trade‐offs’, economic equality has been on the rise. There are only a few notable cases where economic equality has been sacrificed. The Democratic Party's focus during Obama's first presidential campaign in 2008 marks one of those cases where equal rights were prioritized. However, the opposite scenario, that centre‐left parties increase economic equality appeals and decrease equal rights appeals, is similarly common (21.60 vs. 24.69 per cent). A recent case is the 2017 French presidential election, when the Parti Socialiste under Benoît Hamon prioritized economic levelling over equal rights concerns, not vice versa. This case is also shown as the last data point in the French time series of Figure 3.

Figure 3. Salience of economic equality and equal rights for the main social democratic party per country, 1970–2020 (left y‐axis). Bars summarize development between succeeding elections. Positive bars denote the average magnitude of a parallel rise/decline of both concepts. Negative bars denote the average magnitude of an opposite movement of both concepts (right y‐axis). A summary of these party‐specific results can be found in Table 1.

Table 1. Shares of complementary and trade‐off developments among Social Democratic parties. On‐diagonal elements (top left to bottom right) are complementary increases or decreases. Off‐diagonal elements (bottom left to top right) report two kinds of trade‐offs. All cases are reported in Figure 3.

While Table 1 sums up the key result regarding directionality – namely that there is no crowding out – Figure 3 provides details and reminds us of the diversity of cases behind such a summary. It shows the development of positive references to economic equality and equal rights for the main social democratic party per country. The bars summarize the average changes between elections. Positive bars indicate simultaneous increases or decreases, while negative bars suggest one concept's growth at the expense of the other. This, along with attention to economic equality (as in Figure 1, solid line) and equal rights (dotted line), allows a more nuanced assessment of the trade‐off direction for the main Social Democratic parties.

The findings from Figure 3 indicate that cases of trade‐offs between economic equality and equal rights have not emerged recently. Strong trade‐offs were already present in the 1980s, although they were mostly limited to a few countries such as Australia, New Zealand or the United States. While this was sufficient to cause the dip in the reciprocity score depicted in Figure 2, these trade‐offs were counterbalanced by other countries such as France, Ireland and Switzerland, which maintained – or helped to maintain – a complementary relationship between both aspects of equality on average. The trend towards a trade‐off only became prevalent globally for approximately a decade in the 2000s, when three‐quarters of the social democratic parties began to trade off economic equality against equal rights.

Disappearing complementarities rather than crowding out of economic equality by rights

Critiques of the Left by Sandel (Reference Sandel2020), Piketty (Reference Piketty2020), Fraser (Reference Fraser2017) or Eribon (Reference Eribon2009) point to crowding‐out claims (rights are emphasized at the expense of economic equality) that political science could not test thus far. While scholars on party competition and voting argue what parties should do, and party specialists have gathered detailed evidence about what specific parties in specific contexts do, no large‐N data on equality concepts over time have existed so far.

Addressing this lacuna, we draw on a new dataset based on 300,000 fragments of political texts to address the equality of what‐question: instead of conflating different dimensions of equality, the debates about progressive neoliberalism, left ‘Brahmanization’, a meritocratic or ‘woke’ left turn require us to distinguish different aspects of equality. Therefore, we separate positive references to economic equality from references to equal chances and equal rights. This approach allows us to address, drawing from data across 12 countries, the contentious discussions surrounding the alleged ‘meritocratic’, ‘Brahmanized’ or ‘woke shift within the Left, or rather, the three left party families. On this basis, we draw the following conclusions, which go beyond existing political science critiques of Piketty's ‘Brahmanization’ diagnosis:

For most of the past 50 years, different aspects of equality have been perceived as complementary to each other. The analysis does not support the general claim that equal rights or equal chances have crowded out concerns about economic levelling and redistribution.

With regard to an alleged meritocratic turn, we find an increase in equal chances rhetoric since the mid‐1990s, but no displacement/crowding out of economic equality concerns. The ‘you can make it’ drumbeat which characterized the rhetoric of the Democrats under the Clintons and Obama (Sandel, Reference Sandel2020) may indeed sound hollow in countries with low social mobility and high inequality. However, despite some uncontroversial counterexamples, overall, equal chances rhetoric has not crowded out economic equality and redistribution.

The relationship between equal rights and economic equality is complex. Far‐left and green parties tend to prioritize economic equality or rights, respectively. In contrast, social democratic parties have shifted from viewing these goals as complementary to seeing a modest trade‐off since the early 2000s. However, the direction of this trade‐off varies and does not consistently favour one type of equality over the other. While some instances align with Fraser's (Reference Fraser2017) concept of progressive neoliberalism, there are also cases where Social Democrats emphasize economic equality at the expense of equal rights. Therefore, the claim that increased focus on equal rights diminishes efforts towards redistribution is not broadly supported by our findings. Rather, we present further evidence that speaks against an umbrella perspective on ‘the left’.

Based on the data that we release with this research note, others may challenge these conclusions. Further analyses could focus on potentially different strategies of parties in different arenas: How do the party programs relate to statements in the media; what is the role of mediatization more broadly; and what is the link between equality concepts and policies?

While the results we present do not lend themselves to a juxtaposition of redistribution and (equal) rights, it remains to be seen if the clearly waning egalitarian complementarities we document for the (old) Centre‐Left remain stable or even turn into trade‐offs in the long term.

Acknowledgements

This research benefited greatly from the feedback and insights shared at the 2022 American Political Science Association Annual Meeting, Panel ‘Redefining Class Cleavage’, the 2022 ECPR General Conference, Panel ‘The Role of Social Groups in Politics: What Parties Offer and How Voters Respond.’, and the 2022 Annual Conference of the Austrian Political Science Association. Furthermore, we are grateful to Marius Busemeyer, Ann‐Kristin Kölln, Kees van Kersbergen, Peter Hall and Anthony Kevins for their invaluable comments and suggestions during various stages of this project. Special thanks go to our exceptional research assistants ‐ Sophie Reuter, Lukas Röder, Simon Rittershaus, Luke Hosford, Felix Bäckstedt, Jana Dolle and Mathieu Meier – whose support was instrumental in compiling the data. Finally, we extend our gratitude to the editors and anonymous reviewers at the European Journal of Political Research for their constructive feedback.

Data Availability Statement

The data and code supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. The equality data of the Varieties of Egalitarianism project will be available online at https://voe-project.org/ from June 2025.

Online Appendix

Additional supporting information may be found in the Online Appendix section at the end of the article:

Appendix