Introduction

Citizens of rural areas and deindustrializing cities have increasingly shifted away from mainstream parties towards right‐wing populist parties (Gest, Reference Gest2016; Jennings & Stoker, Reference Jennings and Stoker2017; Scala & Johnson, Reference Scala and Johnson2017; Larsen, Reference Larsen, Hansen and Stubager2021). This shift has been attributed to real‐world grievances, such as economic hardship or cultural change, which has fuelled the support for right‐wing populist parties (Rydgren, Reference Rydgren2007; Inglehart & Norris, Reference Inglehart and Norris2016; Colantone & Stanig, Reference Colantone and Stanig2018; Rickard, Reference Rickard2020, Reference Rickard2022). In addition, residents in declining areas perceive politicians in power as unresponsive to their concerns. They feel that they are left out of power, do not get their fair share of resources, and are looked down upon by decision‐makers and urban dwellers alike (Cramer, Reference Cramer2016; Hochschild, Reference Hochschild2016; Munis, Reference Munis2022). One possible source of such interpretations is residents’ local experiences with political decisions. By testing how voters respond to political decisions with adverse local effects, this paper explores the extent to which electoral accountability can explain the electoral shift from mainstream parties to right‐wing populist parties.

I define political decisions with adverse local effects as the choices taken by political bodies, whose effects are negative and geographically bounded. Political decisions with adverse local effects, such as the closure of schools and hospitals have been widespread across Western countries (Ares, Reference Ares2014; OECD, 2020). As people increasingly settle near major metropolitan areas, the population base for many public institutions dwindles. Politicians may decide to close certain institutions in response. Thus, while the overall number of schools in the United States has stayed about the same from 2007 to 2012, 13 per cent of all public schools in rural areas closed (NCES, 2020).

In this paper, I test two possible electoral outlets for residents in areas that get left behind. On the one hand, school and hospital closures establish a direct link between local conditions and specific political bodies. They thus constitute a prime opportunity for voters to hold incumbents accountable for their actions in office. By punishing incumbents at the polls, residents can make it clear to incumbents that their chances of getting re‐elected are tied to their actions in office.

On the other hand, I also test whether school and hospital closures improve the electoral prospects of right‐wing populist parties. While these parties most often are associated with anti‐immigrant rhetoric, another central feature of their platforms is their anti‐elitism (Mudde, Reference Mudde2007; Rydgren, Reference Rydgren2007). They contrast the common sense of ordinary people with the out‐of‐touch propositions of the political establishment. I hypothesize that political decisions with adverse local effects provide right‐wing populist parties with concrete examples that substantiate such claims. Turning to right‐wing populist parties may thus become an appealing outlet for residents of areas affected by political decisions with adverse local effects.

By linking administrative data from Denmark on school and hospital closures to electoral outcomes at the precinct level, I use a generalized difference‐in‐differences design to test how political decisions with adverse local effects affect voter support for incumbents and right‐wing populist parties. I find that when mayors close a local school and the distance to the nearest alternative is greater than 2.5 km, they lose about 4 percentage points of the valid votes in the affected precincts. However, local hospital closures do not seem to affect support for the incumbent government in national elections. Nevertheless, right‐wing populist parties increase their support in both local and national elections by about 0.5 percentage points after a local school or hospital closes. This suggests that political decisions with adverse local effects increase voters’ susceptibility to populist appeals.

Holding incumbents accountable for political decisions with adverse local effects

Electoral accountability entails that voters are empowered to compel politicians to act on their behalf (Fearon, Reference Fearon, Przeworski, Stokes and Manin1999, p. 55). In retrospective voting models, this is achieved by elections in which people base their vote on the incumbent's performance in the previous election period (Key, Reference Key1966; Fiorina, Reference Fiorina1981; Ferejohn, Reference Ferejohn1986). If incumbents perform poorly, people vote them out of office. However, enforcing electoral accountability for political decisions with adverse local effects is challenging as voters must (1) observe and be aware of the decisions, (2) interpret the decision and attribute it to electoral politics, and (3) change their political behaviour accordingly (Healy & Malhotra, Reference Healy and Malhotra2013). In what follows, I outline how we might expect voters to approach each of these three steps when holding incumbents accountable for political decisions with adverse local effects.

Step one: Observing local developments

In order for voters to be able to hold politicians electorally accountable for decisions with adverse local effects, they need to be aware of the decisions. However, it has been argued that the importance of local conditions for political behaviour is declining (Cairncross, Reference Cairncross1998, p. 240). The advent of the Internet has limited the importance of geographic distances to people's access to information and ability to sustain social relationships. Partly due to improvements in information technology, a re‐occurring argument in political behaviour is thus that peoples’ political behaviour becomes increasingly motivated by national considerations (D. E. Bartels, Reference Bartels1998; Caramani, Reference Caramani2004; Hopkins, Reference Hopkins2018; Stokes, Reference Stokes, Chambers and Sorauf1967).

Nevertheless, the expansive literature on “context effects” has demonstrated how people draw information from their local area to inform their vote choice (Huckfeldt & Sprague, Reference Huckfeldt and Sprague1995; Baybeck & McClurg, Reference Baybeck and McClurg2005; Newman et al., Reference Newman, Velez, Hartman and Bankert2015). A central strand in these studies has shown how people respond to the racial and ethnic composition of their neighbourhood (e.g., Key, Reference Key1949; Putnam, Reference Putnam2007; Dinesen & Sønderskov, Reference Dinesen and Sønderskov2015; Enos, Reference Enos2016, Reference Enos2017; Patana, Reference Patana2020). Residents with a majority background feel threatened by increasing shares of minority residents, and higher local ethnic diversity has thus been associated with increased political mobilization, anti‐immigration attitudes, and declining social trust. Recently, increased local ethnic diversity has also been associated with increased support for right‐wing populist parties (Rydgren & Ruth, Reference Rydgren and Ruth2013; Kaufmann, Reference Kaufmann2017; Savelkoul et al., Reference Savelkoul, Laméris and Tolsma2017; Cools et al., Reference Cools, Finseraas and Rogeberg2021; Evans & Ivaldi, Reference Evans and Ivaldi2021).

Another strand in the literature on context effects focuses on how residents respond to local economic conditions (Bisgaard et al., Reference Bisgaard, Thisted Dinesen and Sønderskov2016; Larsen et al., Reference Larsen, Hjorth, Dinesen and Sønderskov2019; Rickard, Reference Rickard2022). Relying on local cues about the economy such as layoffs or housing prices, people form a perception of the overall economic conditions. Stagnating or declining local housing prices or increased local exposure to import competition has thus been shown to increase local support for right‐wing populist parties (Colantone & Stanig, Reference Colantone and Stanig2018; Ansell et al., Reference Ansell, Hjorth, Nyrup and Larsen2022).

Common for these arguments is that people either draw information from their local context through casual observations or social interactions with local acquaintances (Baybeck & McClurg, Reference Baybeck and McClurg2005), both mechanisms with a limited geographical reach. Voters are much more inclined to have close social relationships with others in their local area (Preciado et al., Reference Preciado, Snijders, Burk, Stattin and Kerr2011), and people's movement patterns are scale‐dependent restricting which developments they casually encounter (Alessandretti et al., Reference Alessandretti, Aslak and Lehmann2020). However, many local developments do go unnoticed by residents (Hopkins, Reference Hopkins2018, p. 122). Previous studies have thus argued that salience conditions the importance of local conditions for people's political behaviour (Hopkins, Reference Hopkins2010; Enos, Reference Enos2017; Larsen et al., Reference Larsen, Hjorth, Dinesen and Sønderskov2019). As an issue becomes more salient to voters, they are more likely to rely on considerations related to that issue (Zaller, Reference Zaller1992). Applied to the local context, a particular aspect of the local context is more likely to be salient to residents who have regular or recent contact with that particular aspect of the local area, if the aspect increases the contrast to developments elsewhere, or if it receives significant media coverage (Hopkins, Reference Hopkins2010; Enos, Reference Enos2017; Larsen et al., Reference Larsen, Hjorth, Dinesen and Sønderskov2019). Thus, I expect stronger reactions to decisions with adverse local effects in policy areas where many people personally interact with the area, where the developments go against general trends, and where the decision receives intense media coverage. I further argue that salience increases with the severity of the decision because decisions with more severe consequences are more intrusive into residents’ daily lives.

Step two: Interpreting and attributing blame

Given that residents are aware of a political decision with adverse local effects, they need to figure out what to make of the decision and whom to blame or praise. Both substeps are challenging and may hinder voters’ tendency to hold politicians accountable.

Previous studies have argued that citizens often lack clear frames to interpret local developments and thus come to rely on national news media (Hopkins, Reference Hopkins2010, Reference Hopkins2011). Journalists frame local developments in certain ways in their stories which makes local developments more intelligible to their audiences. Hopkins argues that this increases the nationalization of politics, as local experiences primarily enter people's political considerations as an extension of national issues (Hopkins, Reference Hopkins2018, p. 123).

However, political decisions with adverse local effects lack the ambiguity that characterizes many other local developments. By definition, they have negative effects on the affected communities. Irrespective of whether residents’ votes are guided by rational considerations to preserve the value of their house (Fischel, Reference Fischel2001), or whether they rely on group cues such as place‐based social identities (Munis, Reference Munis2022; Schulte‐Cloos & Bauer, Reference Schulte‐Cloos and Bauer2023), a decision that adversely affects the local community will be viewed unfavourably.

But whom should residents blame? Assigning blame requires that residents navigate the multiple levels of government and jurisdictions. As previous studies have found, this is challenging. Even when a decision is imposed directly through a ballot initiative, voters can end up punishing unrelated incumbents (Sances, Reference Sances2017). Proponents of multiple levels of government argue that the different levels improve accountability and balance power, as it allows citizens to pursue their concerns in alternative avenues (Downs, Reference Downs1999, p. 94). However, overlapping jurisdictions also allow politicians to shift blame and falsely claim credit (Arceneaux, Reference Arceneaux2006, p. 732). Clearer boundaries of responsibility have thus been shown to improve voters’ tendency to hold politicians accountable (Larsen, Reference Larsen2019).

Political decisions with adverse local effects link local conditions to a particular level of government. Unlike local conditions such as high unemployment, if a political body took the decision it then bears responsibility. Thus, I argue that political decisions with adverse local effects provide an ideal situation for voters to hold incumbents accountable for local developments.

Step three: Change political behaviour

The final step for citizens when holdings politicians accountable for local developments is to change their political behaviour. Previous studies have shown that residents mobilize in response to local changes, such as the placement of nuclear power plants, airports, dams, wind turbines or the closure of local schools (Aldrich, Reference Aldrich2008; Stokes, Reference Stokes2016; L. C. Nuamah & Ogorzalek, Reference Nuamah and Ogorzalek2021). Furthermore, Lindbom (Reference Lindbom, Kumlin and Stadelmann‐Steffen2014) finds that voters punished the responsible party for proposals to close nine emergency wards in 16 Swedish counties, while Møller et al. (Reference Møller, Kjær, Larsen, Elklit, Hansen and Kjær2021) find negligible effects of schools closures on the support for incumbents at the municipal level in Denmark.

Following retrospective voting models, these studies show that people base their vote choice on the performance of the incumbent government. When incumbents perform poorly or somehow harm local interests, people punish them at the polls. So I hypothesize that

H1: Political decisions with adverse local effects cause the support for the responsible incumbent parties to fall in the affected areas.

But who do residents of affected local areas turn to? In two‐party systems, voters have limited options. However, in a multiparty system, such as the Danish under study here, the possibilities abound. I theorize that decisions with adverse local effects enhance the prospects of right‐wing populist parties in particular because these decisions provide concrete experiences that corroborate their anti‐elitist rhetoric.

In studies exploring place‐based resentment such as Cramer's interviews with rural residents in Wisconsin, the United States, a prominent narrative is that government does not work for rural people (Cramer, Reference Cramer2016, p. 65). They express resentment towards establishment politicians who they perceive as disrespectful and out of touch with people like them (Cramer, Reference Cramer2016; Gest, Reference Gest2016; Hochschild, Reference Hochschild2016). Studies have thus shown how right‐wing populist parties have been able to capitalize on citizens’ frustrations with the political system, such as corruption scandals, the convergence of policy platforms among mainstream parties and distrust of political elites (Della Porta & Mény, Reference Della Porta and Mény1997; Abedi, Reference Abedi2002; Bergh, Reference Bergh2004). Similarly, they benefit when local community hubs in the form of pubs are closed or when immigrants are allowed to build mosques with minarets in the local area (Bolet, Reference Bolet2021; Gravelle et al., Reference Gravelle, Medeiros and Nai2021).

A central aspect of the political platforms of right‐wing populist parties is their anti‐elitism (Mudde, Reference Mudde2007; Rydgren, Reference Rydgren2007), which enables them to appeal to residents’ frustrations. Furthermore, right‐wing populist parties have been found to champion policies to preserve local communities (Fitzgerald, Reference Fitzgerald2018; Harteveld et al., Reference Harteveld, Van Der Brug, Lange and Van Der Meer2022). I argue that political decisions with adverse local effects make anti‐elitist appeals more compelling. They provide residents with concrete experiences of how politicians in power downgrade their local area. They thus substantiate narratives that portray mainstream politicians as arrogant and out of touch. I, therefore, hypothesize that

H2: Political decisions with adverse local effects cause the support for right‐wing populist parties to rise in the affected areas.

Political decisions with adverse local effects: School and hospital closures

To gain sufficient leverage to determine how voters react to political decisions with adverse local effects, I need data on a substantial number of similar decisions. To my knowledge, this has limited previous attempts to study the effects of political decisions with adverse local effects (see, Lindbom, Reference Lindbom, Kumlin and Stadelmann‐Steffen2014; Møller et al., Reference Møller, Kjær, Larsen, Elklit, Hansen and Kjær2021). I overcome these challenges by utilizing the downstream effects of a comprehensive reform of local and regional government in Denmark. In 2007, the 271 municipalities in Denmark were merged into 98 and the 13 counties were replaced by five regions. These new entities adjusted how they delivered their public services and accelerated the trend towards fewer and larger schools and hospitals.

It may seem paradoxical that politicians decide to close a school or hospital in the first place, as they may expect a backlash. However, amalgamating public institutions at fewer locations has been claimed to simultaneously cut costs and improve public services. When public institutions are consolidated at fewer locations, the population base for each institution increases. This allows public employees to further specialize in subfields, and thereby potentially improve the quality of services. Simultaneously, politicians may expect costs to decrease due to economies of scale. These were some of the prime arguments that motivated the reform of local and regional government in the first place (Strukturkommissionen, 2004), and subsequent studies have validated some of these claims (Blom‐Hansen et al., Reference Blom‐Hansen, Houlberg and Serritzlew2014, Reference Blom‐Hansen, Houlberg, Serritzlew and Treisman2016). The only apparent downside of amalgamations is that some public institutions must close to make way for the new, bigger institutions.

Schools and hospital closures are clear examples of political decisions with adverse local effects. While residents may acknowledge the potential benefits of larger institutions, their local community bears the geographically concentrated costs. Closures most obviously affect residents’ access to the public services the entity provides, as they must travel farther to access alternative services. Residents thus experience a deterioration in the service tax package in the affected areas relative to other communities. In addition, schools and hospitals provide local communities with a base of stable jobs that can insulate the local area from large fluctuations in the surrounding economy. Schools and hospitals are also important hubs that maintain the social coherence of the local community. The closure of central community institutions such as schools and hospitals can, therefore, also be seen as a threat to the social status and future viability of the community (Bolet, Reference Bolet2021). Thus, the closure of a school or hospital affects not only the residents who interact with the institution on a daily basis but also the broader community.

In Denmark, different levels of government are responsible for schools and hospitals. Public schools are the responsibility of local municipal councils, which also have the power to close them (Public School Act, 2023). Prior to any closure, they are required to hold a consultation period during which residents can voice their objections. As the head of the executive branch of local government, the incumbent mayor usually leads this process. The consultation period ensures public feedback and makes it clear to the local community that elected officials are trying to close the local school.

The physical organization of hospitals is formally the responsibility of directly elected regional councils (The Danish Government, 2004, p. 34). However, the placement of medical specialties is decided jointly by the regional and national governments (Vallgårda, Reference Vallgårda, Vallgårda and Krasnik2016, p. 186). Furthermore, changing national governments have been heavily involved in the efforts to build several new “super hospitals”—so much so, that candidates for the national parliament have made election pledges to keep certain hospitals open (Bisgaard, Reference Bisgaard2010). As the planned super hospitals require huge investments, the regional governments are dependent on funding from the national government (The Danish Government & Danish Regions, 2008). So, although the clarity of responsibility is less than in the case of schools, I find it reasonable to expect that voters will hold the national government responsible.

The Danish government maintains central registers of the location and eventual closure dates of both schools and hospitals. However, the main focus of the registers is on administrative units. This raises some concerns about which entities are included and when an entity is considered closed. I followed a three‐step process (see online Appendix D) to ensure that I have included all relevant entities and that the closing dates were accurately recorded. First, I developed comprehensive lists of all relevant entities from 2005 to 2019. Here, I complimented the data from the Danish Institution Registry (National Agency for IT & Learning, 2020) and the Danish Healthcare Organization Registry (National Health Data Authority, 2019) with data collected by Møller et al (Reference Møller, Kjær, Larsen, Elklit, Hansen and Kjær2021), which is based on minutes from municipalities, and data from the Danish Central Business Registry, and observations from the news article archive InfomediaFootnote 1 (Infomedia, n.d.). Second, I enriched each observation with information about its location, whether it started operating during the study period, and its eventual closure date. Finally, I went through the list again and removed any duplicates. The resulting data are, to my knowledge, the most accurate and complete data on the number, location, and closure date of all schools and hospitals in Denmark.

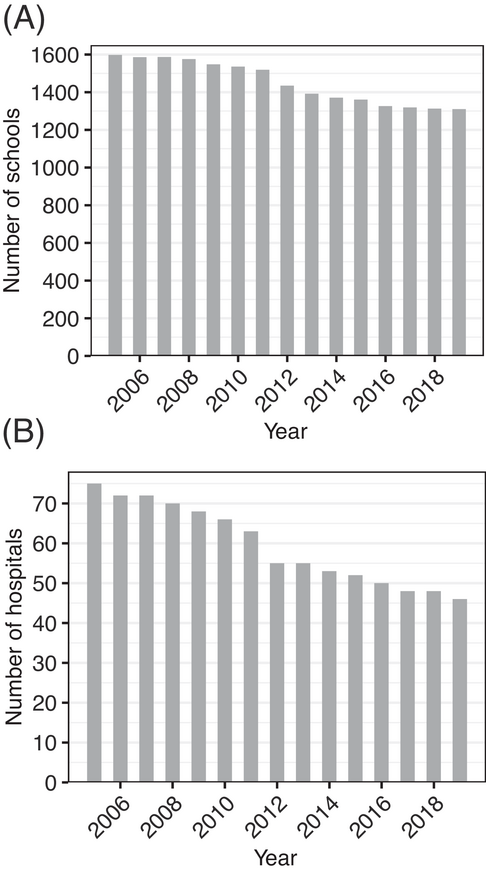

The data have information from 2005 to 2019 on 1625 schools, of which 315 were closed and 18 were opened during the study period. It also contains information from 2005 to 2019 on 75 hospitals, 30 of which were closed. As shown in Figure 1, schools and hospitals closed continually in the decade following the reform and different local areas were affected by different decisions at different times.

Figure 1. Number of schools and hospitals in Denmark 2005–2019.

Figure 2 shows the geographical distribution of all schools and hospitals in Denmark. Most of the country has experienced at least some closures, but they tend to be more frequent in rural areas away from the major cities. An analysis of the spatial clustering of the closures shows some evidence of clustering, as closed schools are less likely to be located near other closed schools, while hospitals that did not close are clustered around Copenhagen. This reflects that closures are the result of deliberate political processes and not random events.

Figure 2. Geographical Distribution of school and hospital closures in Denmark 2005–2019. Note: Shaded by population density. The darker the area, the more inhabitants per square kilometre.

Data

To analyse voters’ reactions to school and hospital closures, I rely on precinct‐level election results from Danish national elections in 2007, 2011, 2015 and 2019 and Danish local elections in 2009, 2013 and 2017 (Statistics Denmark & Thomsen, Reference Statistics Denmark and Thomsen2022). Unlike surveys, which often lack granular geographic information, election returns allow me to accurately link school and hospital closures to the affected precinct and ensure that I cover low‐density areas. National elections determine the composition of parliament, which then elects the government on the basis of negative parliamentarism. Local elections for municipal councils similarly elect the local mayor. On average, about 3000 citizens vote at a single polling station in each precinct. To account for the minor redistricting that has occurred between the elections, I fix the geographical boundaries at a reference election (2019) and recalculate the voting results in precincts where boundaries changed to correspond to their boundaries in the reference election (for details on the procedure see: Thomsen, Reference Thomsen2010; Larsen et al., Reference Larsen, Hjorth, Dinesen and Sønderskov2019). In the reference year, I observe 1377 precincts in Denmark. All dependent variables in the analysis are drawn from the election results.

To determine which precincts were affected by a particular political decision with adverse local effects, I link school and hospital closures to the precincts by their geographic location. To do this, I first geocode the addresses of all schools and hospitals (QGIS.org, 2020). I consider a precinct to be affected by a school closure if a school within its boundaries closed during the study period. This approach is not appropriate for hospitals because they serve a much larger catchment area. Most precincts do not have a local hospital within their boundaries. Instead, I use the centroid of the precinct as a reference point to match each precinct to the nearest hospital.

I measure support for incumbents as the percentage of valid votes cast for the parties holding executive power in the year of the closure. In national elections, I include support for all government coalition partners, consistent with previous studies of local responses to local economic conditions (Elinder, Reference Elinder2010; Larsen et al., Reference Larsen, Hjorth, Dinesen and Sønderskov2019; Simonovits et al., Reference Simonovits, Kates and Szeitl2019). In local elections, I measure incumbent support as the percentage of valid votes in the precinct for the mayor's party. In national elections, all precincts experienced three different incumbent constellations.Footnote 2 In local elections, most municipalities have also seen shifts in which party holds the mayor's office. While parties on the fringes of the political spectrum (far‐right or far‐left) rarely hold the mayor's office and sponsor school closures, most other parties have had mayors who have initiated closures. To avoid confounding the results with differences in incumbency changes between the treatment and control groups, I construct separate control groups for each election year. The control groups thus consist of the percentage of valid votes cast for the parties that held executive power in the same year that the closure took effect in the treatment group.

I measure support for right‐wing populist parties as the percentage of valid votes cast for the Danish People's Party, following previous studies of right‐wing populist parties in Denmark (Bächler & Hopmann, Reference Bächler, Hopmann, Aalberg, Esser, Reinemann, Str¨ombeck and De Vreese2017; Larsen, Reference Larsen, Hansen and Stubager2021). I also include support for the two new right‐wing populist parties, The New Right and Hard Line, in the 2017 local elections and the 2019 national elections, as they make similar appeals.

In the analysis, I excluded precincts that were affected by a closure in the election period before the first observed election,Footnote 3 that were affected by closure more than once during the observation period,Footnote 4 where the relevant parties did not field candidates,Footnote 5 where there was no school within the precinct's boundaries,Footnote 6 or where a new school opened in the precinct during the study period.Footnote 7

Identification

Because political decisions with adverse local effects are nonrandom events, the precincts that are affected by the closures are likely to be systematically different from the precincts not affected. This raises concerns about selection bias. To limit this concern, I rely on a generalized difference‐in‐differences design, which I supplement with matching on precinct‐level covariates.

Until recently, the two‐way fixed effects estimator, as described by Angrist and Pischke (Reference Angrist and Pischke2009, p. 237), was the most common approach to analysing the effects of a staggered treatment (such as the rolling closure of schools or hospitals). The two‐way fixed effects estimator has been viewed as desirable as it holds constant common changes across units in a given year and unit‐specific differences over time. However, recent developments in econometrics have shown that the two‐way fixed effects estimator is biased when treatment is staggered in time (Chaisemartin & D'Haultfœuille, Reference Chaisemartin and D'Haultfœuille2020; Callaway & Sant'Anna, Reference Callaway and Sant'Anna2021; Gardner, Reference Gardner2021; Goodman‐Bacon, Reference Goodman‐Bacon2021). The longer a unit is observed while being treated, the more of the effect of the treatment will be captured by the unit fixed effect. Similarly, if most precincts are affected in a given year, the year fixed effect will pick up some of the effects of the treatment. Along with these criticisms, a number of alternative estimators have been proposed. Here, I rely on the approach developed by Callaway and Sant'Anna (Reference Callaway and Sant'Anna2021), which estimates group‐time average treatment effects. That is, they estimate a separate average treatment effect for each group that is affected by the treatment at different points in time. These estimates can then be aggregated to capture how the average treatment effects vary with the duration of exposure, similar to the two‐way fixed effects estimator (Callaway & Sant'Anna, Reference Callaway and Sant'Anna2021, p. 208). For the effect on incumbent support, I estimate separate models for the effect of the closures in each election year, since the control group changes from election to election. In the local elections, I estimate one model for closures that took effect between 2009 and 2013 and another model for closures that took effect between 2013 and 2017. Similarly, I estimate three separate models in the national elections. In the following, I aggregate these models by using a fixed‐effects meta‐analysis. In doing so, I assume that the true effect of the closures is constant over time, despite the changes in the composition of the treatment and control groups. The pooled estimate is a weighted average of the effect estimates within each election year and can be interpreted as the average effect of a closure in the affected precincts. I report the group‐time average treatment effects in online Appendix C.

While the estimator is different, the causal interpretation of the estimates follows similar assumptions as the traditional difference‐in‐differences design. That is, changes in people's votes should follow common trends in the absence of the closures (Angrist & Pischke, Reference Angrist and Pischke2009; Callaway & Sant'Anna, Reference Callaway and Sant'Anna2021, p. 230). While it is not possible to test this assumption directly, I can compare the trends in the pre‐treatment period and examine whether the assumption holds in the periods before the political decisions with adverse local effects took effect. In the following, I refer to the first election after a precinct is affected by a closure as p. I enumerate the remaining elections in relation to p. The election before the closure is p − 1 and is the reference election in the analysis. For some precincts, p will be the second election I observe, while for other precincts it may be the last. Since I have data from three local and four national elections for each precinct, only a limited number of precincts are observed in p − 2 and p − 3. If

![]() ${\beta }_{p + j} = \ 0\ \forall \ j < 0$, the common trends assumption holds in the pre‐treatment periods, which should increase the confidence in the assumption of common trends in the post‐treatment periods.

${\beta }_{p + j} = \ 0\ \forall \ j < 0$, the common trends assumption holds in the pre‐treatment periods, which should increase the confidence in the assumption of common trends in the post‐treatment periods.

Meanwhile, the coefficients in the post‐treatment periods (j > 0) inform us about the persistence of the effect. They can be interpreted as the difference in the trend in support from before the relevant decision was implemented, till the relevant post‐treatment period. Following the advice of Callaway and Sant'Anna (Reference Callaway and Sant'Anna2021), I use a doubly robust estimation method and a uniform confidence band. All models use clustered bootstrapped standard errors at the precinct level to take account of serial within‐precinct autocorrelation.

As reported in online Appendix E, the precincts affected by school and hospital closures were, on average, significantly larger and less populous than those not affected by closures. These differences in levels are not necessarily detrimental to identifying the causal effect of school and hospital closures, as the identifying assumption is that they follow common trends. Nevertheless, the differences could still indicate that the residents are different and that their support for incumbents or right‐wing populist parties may follow different trends.

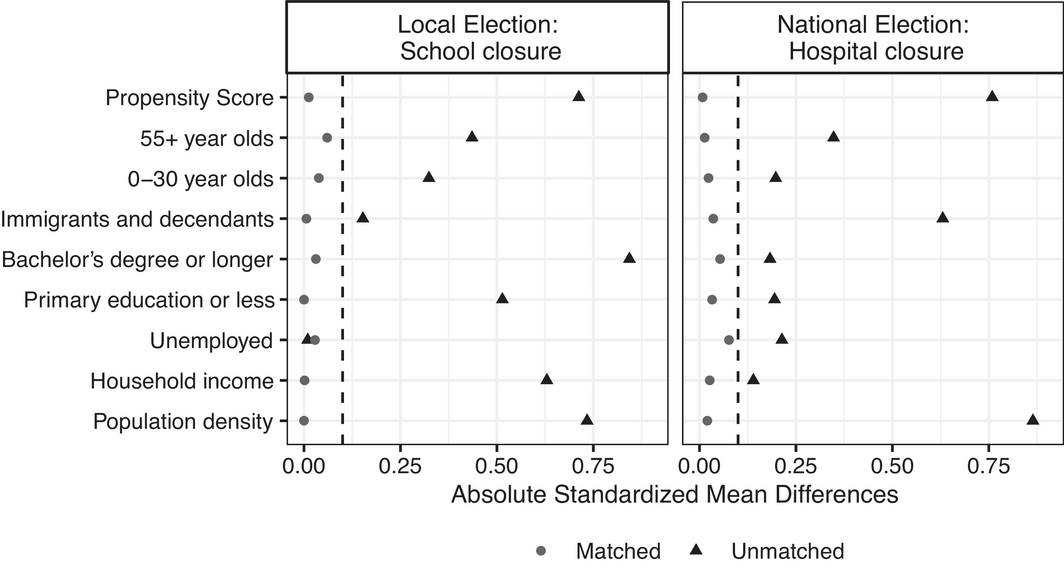

To limit the potential extent of this bias, I rely on propensity score matching and match each affected precinct to a non‐affected precinct based on covariates in the first election period (Ho et al., Reference Ho, Imai, King and Stuart2007). I match each precinct basis of the proportion aged 55+, the proportion aged 0–30, the proportion of non‐Western immigrants and descendants, the proportion with a bachelor's degree or more, the proportion with a primary school education or less, the proportion of unemployed, the log median household income, and the population density in the zip code which the precincts centroid is located.Footnote 8

As can be seen in Figure 3, this significantly reduces the differences in the covariates in the pre‐treatment period between the affected and unaffected precincts before the closures. After matching, the absolute standardized mean difference is below the threshold of 0.1 for all covariates. In the following, I report results for both the matched and unmatched control groups.

Figure 3. Balance on covariates between affected and unaffected precincts in the pre‐treatment election. Note: Nearest neighbour matching based on logistic regression propensity scores. Each affected precinct is matched to a precinct in the control group in the matched sample. Districts are observed in 2009 for local elections and in 2007 for national elections.

Do voters punish incumbents for political decisions with adverse local effects?

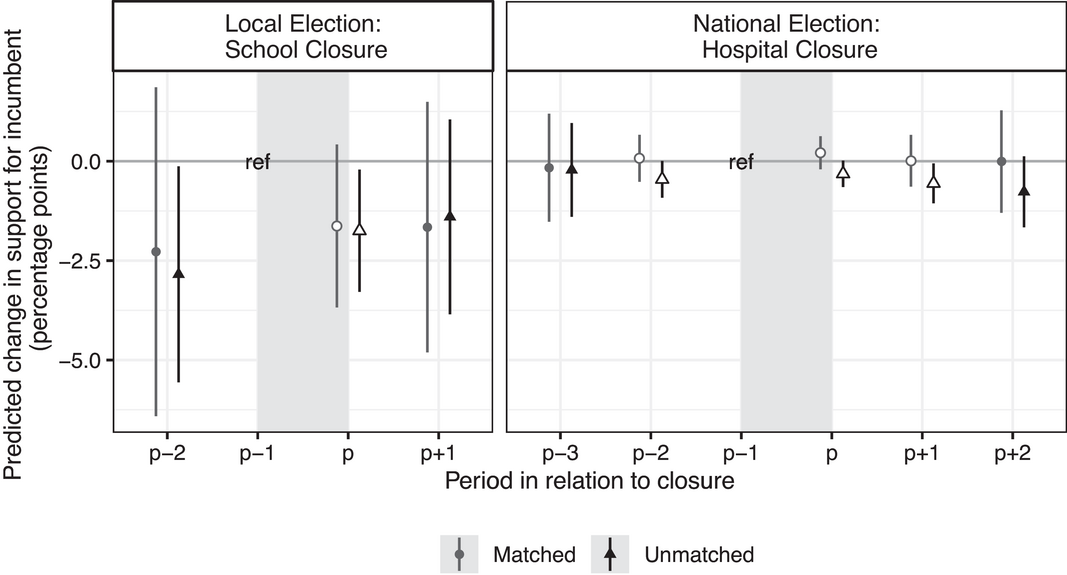

In Figure 4, I report the estimated effect of school and hospital closures on changes in the support for the incumbent mayor (local elections) and the incumbent government (national elections) in the election immediately following the closure (p), as well as in the following elections (p + j), and preceding elections (p − j). Full regression tables including group‐time average treatment effects are available in online Appendix C.

Figure 4. Estimated effect of school and hospital closures on electoral support for responsible incumbent parties. Note: Vertical lines indicate 95 per cent confidence intervals based on clustered standard errors at the precinct level. Estimates shown in white are aggregations using fixed‐effects meta‐analysis of group‐time average treatment effects.

Overall, I find only very limited support for the proposition that political decisions with adverse local effects cause support for the responsible incumbents in the affected areas to decline. I do find that when a school is closed within a precinct support for the incumbent mayor's party declines by 1.6 percentage points (95 per cent CI 3.1–0.1) more than in the unmatched precincts that were not affected by closures. This is a substantial penalty for a single political decision. Especially given that the substantial size of the estimate seems to persist for another election (p + 1). However, this estimate does not reach conventional levels of statistical significance. Furthermore, in local elections, there is a tendency for precincts that are subsequently affected by a school closure to have increased their support for the mayor's party more than unaffected precincts in the election immediately preceding the closure. While the differences are not statistically significant, the magnitude of the difference still suggests that the assumption of common trends could be violated. Thus, the change in support may reflect the return of affected precincts to their pre‐treatment levels rather than a specific response to the school closures specifically.

In national elections, I find no indication that voters hold the government accountable for local hospital closures. In the unmatched sample, government parties tend to lose in the elections following the closure. However, this difference disappears in the matched sample. Instead, the estimates show that the difference in the change in support for government parties that closed a hospital between affected and unaffected counties is about 0.2 percentage points (0.6 to −0.2) in the election immediately following the closure. Furthermore, the effect of hospital closures on support for the parties in the responsible government does not change much in the subsequent elections (p + 1 and p + 2), and I find no significant differences between the trends in support for the government parties in the pre‐treatment periods between precincts affected by hospital closures and those not affected by hospital closures.

One explanation for these results may be that voters did not correctly assign responsibility for the closures. This may be a plausible explanation in the case of hospitals, where responsibilities overlap between national and regional governments. However, it seems less applicable to school closures given the clear responsibilities and public consultation periods.

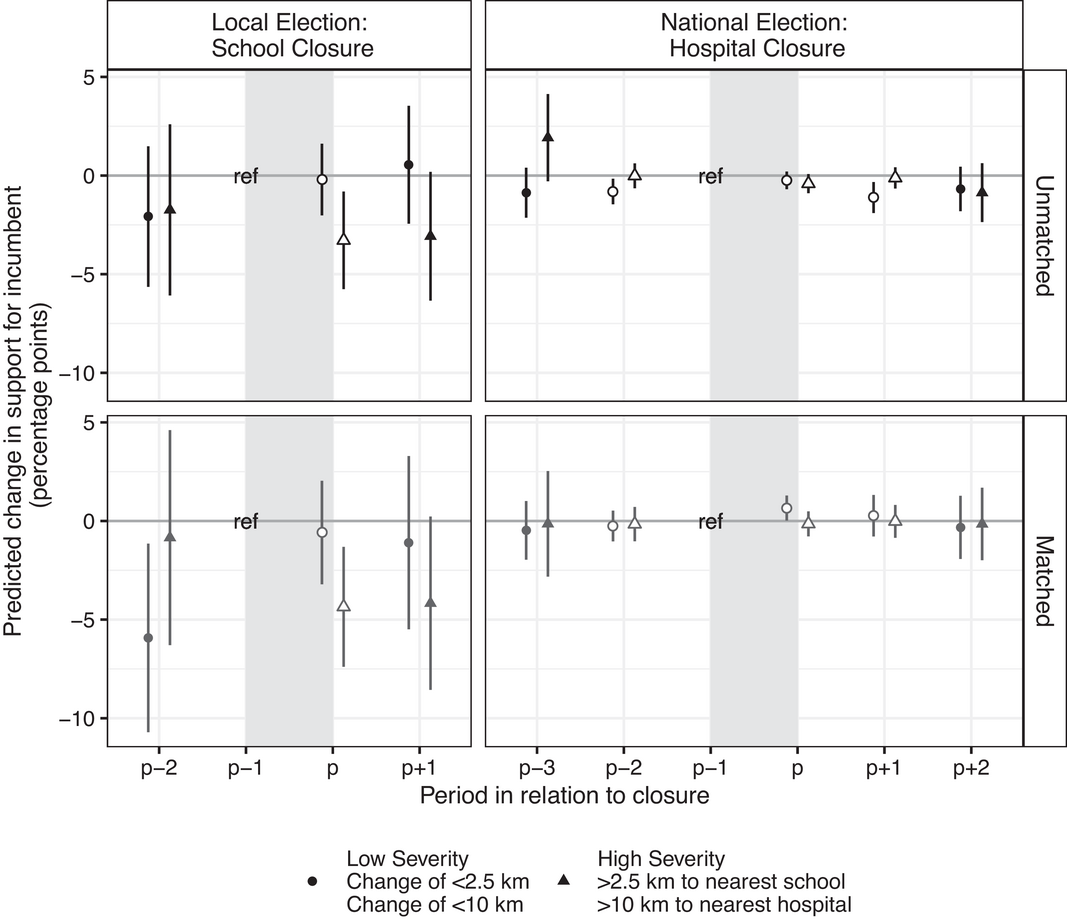

Another explanation may be that voters are unaware of the closures or that they affect them so lightly that they do not see them as a net negative. To test whether a lack of salience explains the results, I construct a measure of how severely a precinct was affected by the closure. To allow me to distinguish between the effects on precincts that were lightly affected by political decisions with adverse local effects and those that were much more severely affected, I use the change in the distance from the precinct's centroid to the nearest relevant entity throughout the study. This allows precincts to be affected by school closings outside their boundaries. This changes slightly when I consider a precinct to be affected by a school closure. I consider precincts to be affected by a political decision with high severity if the distance to the nearest school increased by more than 2.5 km (∼1.6 miles) or the distance to the nearest hospital increased by more than 10 km (∼6.2 miles). In online Appendix A, I show results with alternative specifications. Dichotomizing closures into low‐ and high‐severity precincts facilitates the interpretation of the results and avoids the strong assumptions associated with difference‐in‐differences estimates with a continuous treatment (Callaway et al., Reference Callaway, Goodman‐Bacon and Sant'Anna2021). I report the predicted change in incumbent support across the two levels of exposure to political decisions with adverse local effects in Figure 5.

Figure 5. Change in support for incumbents across levels of severity of political decisions with adverse local effects. Note: Vertical lines indicate 95 per cent confidence intervals based on clustered standard errors at the precinct level. Estimates shown in white are aggregations using fixed‐effects meta‐analysis of group‐time average treatment effects.

The equivocal findings regarding school closures and mayoral support become less ambiguous when we consider the difference in the response of precincts that are lightly affected by school closures and those that are severely affected. Consistent with expectations, I find no effect of school closures on the mayoral support in precincts that are only lightly affected by school closures. In contrast, in precincts where the distance to the nearest school increased by more than 2.5 km, support for incumbents fell by an average of 4.3 percentage points (7.4–1.2) relative to the matched control group in the election immediately following the closure. This effect seems to persist one election later in p + 1. Moreover, there is no evidence of differences in the change in support for mayors in the pre‐treatment period leading up to the closure, strengthening the argument for a causal interpretation of the results.

In national elections, I find no substantial difference in the response of precincts that were lightly and severely affected by hospital closures. I do not find that precincts that are affected by hospital closures change their support for government parties any differently than precincts not affected by hospital closures. Thus even when voters are hit hard by a hospital closure, they do not lash out at the national government.

Overall, these results suggest that political decisions with adverse local effects only in certain circumstances localize people's support for incumbents. When local politicians close down the school, voters punish the local mayor in the following election if the closure substantially alters the distance to other schools. This is encouraging for the state of accountability in local elections, as voters seem to respond proportionally to the level of their grievance. In contrast, voters largely absolve the national government from political decisions with adverse local effects. They may therefore have limited incentives to address local concerns.

Do voters reward right‐wing populist parties when affected by political decisions with adverse local effects?

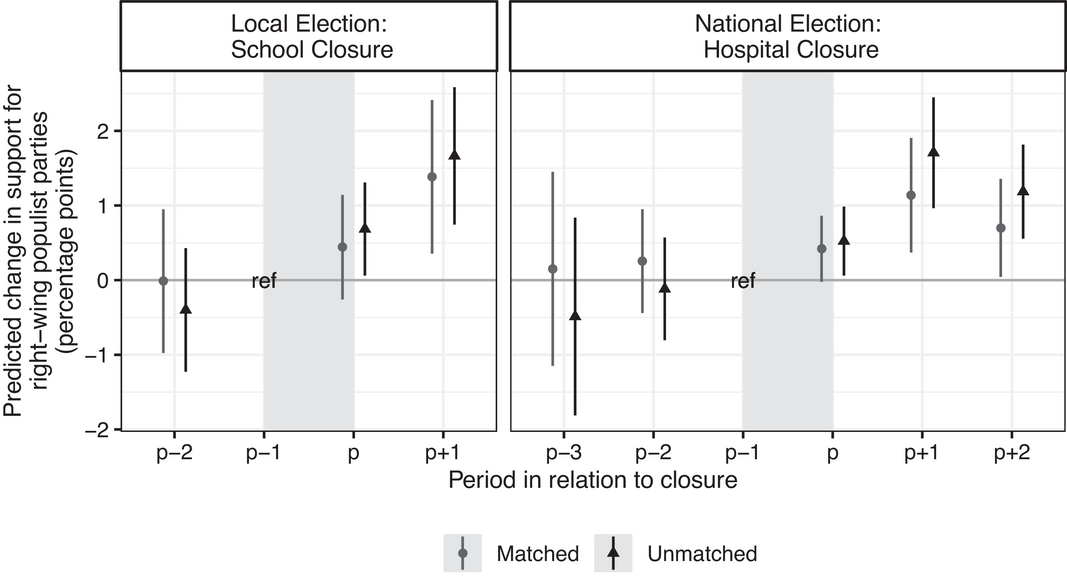

Political decisions with adverse local effects may provide opportunities for right‐wing populist parties to mobilize disgruntled voters in the affected localities, even though they appear to have little effect on support for incumbents. In Figure 6, I test H2 by estimating the effect of school and hospital closures on support for right‐wing populist parties. Full regression tables including group time average treatment effects are available in online Appendix C.

Figure 6. Estimated effect of school and hospital closures on electoral support for right‐wing populist parties. Note: Vertical lines indicate 95 per cent confidence intervals based on clustered standard errors at the precinct level.

I find that right‐wing populist parties increase their vote share in the corresponding elections in areas affected by a political decision with adverse local effects. Right‐wing populist parties receive 0.7 percentage points (95 per cent CI 0.06–1.3) more of the valid votes in local elections in precincts where a school was closed in the preceding election period than in precincts in the unmatched control group. Considering that right‐wing populist parties averaged about 10 per cent of the valid votes in local elections during the period studied, this is a substantial increase in their support.

Similarly, right‐wing populist parties increase their vote share in national elections in areas affected by a nearby hospital closure. Support for right‐wing populist parties increases by 0.5 percentage points (0.06–1.0) after the closure of the nearest hospital, compared to precincts in the unmatched control group. These results are mirrored in the estimates that rely on the matched control group. However, they do not reach conventional levels of statistical significance in the first election after the closure. Nevertheless, in both local and national elections, the increase in support for right‐wing populist parties in precincts affected by political decisions with adverse local effects persists and increases in the post‐treatment periods. In local elections, the effect more than doubles to an increase in the support for right‐wing populist parties of 1.4 percentage points (0.2–2.6) compared to the matched control group in p + 1. The same is true for hospital closures in national elections. Here the support for right‐wing populist parties increases to 1.1 percentage points (0.3–1.9) in p + 1 after the closure compared to the matched control group, before it falls back to 0.7 percentage points (0.01–1.4) in p + 2.

Since the counties affected by the school and hospital closures are significantly larger and less densely populated, it is a legitimate concern that these results are driven by different trends in support for right‐wing populist parties between the affected and unaffected precincts. However, as shown in the pre‐treatment trends, I find no evidence of a substantial or statistically significant difference in the change in support for right‐wing populist parties in any of the pre‐treatment periods leading up to the closure. All models seem to have common trends in support for right‐wing populist parties before the closures. It is only after the closures that support for right‐wing populist parties increases more in the affected precincts.

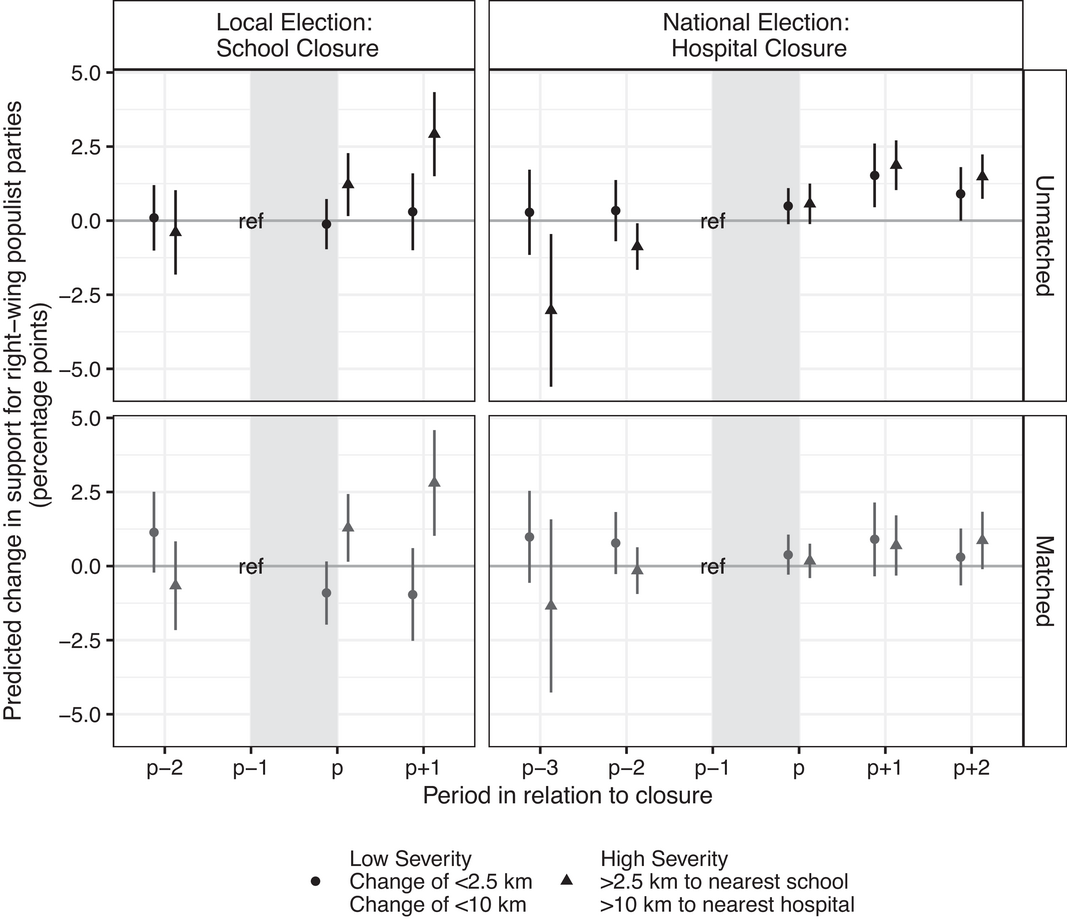

These findings are further corroborated by tests in which I distinguish between the effects on precincts that are lightly affected by political decisions with adverse local effects and those that are much more severely affected. In Figure 7, I report the predicted change in support for right‐wing populist parties between different levels of severity. The specifications are parallel to Figure 5.

Figure 7. Predicted change in support for right‐wing populists across levels of exposure to political decisions with adverse local effects. Note: Vertical lines indicate 95 per cent confidence intervals based on clustered standard errors at the precinct level.

In local elections, it is clear that the effect is driven by precincts that are severely affected by the closure. Thus, I find no increase in the support for right‐wing populist parties in precincts where the distance from the centroid to the nearest school increased by less than 2.5 km. However, in precincts where the distance from the centroid to the nearest school increased by more than 2.5 km, support for right‐wing populists increased by 1.3 percentage points (0.2–2.4) compared to the matched control group. In national elections, I do not see the same split between precincts that are severely affected by hospital closures and those that are not. In national elections, the increase in support for right‐wing populist parties seems to be driven by the decisions in themselves, and not by the severity of the decisions. People seem to react to the act of closing down a local hospital and not to the actual adverse consequences of the decision.

But where do these voters come from? While some of the votes may come from incumbents, the preceding analysis does not provide clear support for this hypothesis. To explore this question, I estimated the effect of school and hospital closures on support for all major parties in both local and national elections. I report the results of these tests in online Appendix B. While these analyses show that decisions with adverse local effects provide an opportunity for electoral change and that some parties can match the success of the right‐wing populist parties in one policy area, none benefit as consistently across electoral levels and policy areas. Right‐wing populist parties seem to be particularly appealing to disaffected voters. School closures tend to dampen the overall support for most other parties, but the estimates are substantially small and statistically insignificant. Hospital closures, on the other hand, seem to be blamed on the Liberals. The Liberals were the main proponents of the original local government reform, and they have also traditionally had their strongholds in rural areas, which were the most affected (Hansen & Stubager, Reference Hansen, Stubager, Hansen and Stubager2017).

Because this study is based on data aggregated at the precinct level, the results come with certain caveats. Without individual‐level data, I cannot distinguish between outcomes caused by changes in the composition of the precinct's electorate and outcomes caused by residents changing their votes. In the analysis, I have treated the precincts as stable units, but people move from precinct to precinct between elections. An alternative outlet for residents’ frustration with deteriorating local public services may be to move to better‐served local areas. When a school closes in an area, it becomes less attractive for families with children to live there. Hospital closures can have a similar effect on other segments of the population. This could also explain the persistence of the effects, as the political decisions permanently change the composition of the electorate in the precincts. The exploratory analysis in online Appendix F provides some support for this proposition, as the number of eligible voters tends to decrease in the affected areas while the turnout stays about the same. Thus right‐wing populist parties do not mobilize more votes but rather increase their relative strength in the affected areas. The exact mechanism, however, remains unresolved.

Overall, political decisions with adverse local effects increase the relative strength of right‐wing populist parties in the affected precincts. These results support H2. Right‐wing populist parties express disagreement with the establishment's ideas of consolidating public services and appeal to residents’ experiences of being left behind. In doing so, they can use political decisions with adverse local effects to their electoral advantage.

Discussion and conclusion

Local news articles often tell the story of demonstrations, petitions, and sometimes threats to elected leaders when a local community bears the geographically concentrated costs of political decisions (see, e.g., Ebbesen, Reference Ebbesen1998; Johnson, Reference Johnson2003; Brandt, 2009; Weiss‐Tisman, Reference Weiss‐Tisman2016). As I show in this study, this is also reflected in how residents vote. Political decisions with adverse local effects affect election outcomes in the affected areas.

In local elections, I find that Danish voters punish mayors at the polls when their local area is affected by school closures. Voters react proportionally to the severity of the decision and hold elected officials accountable for their behaviour in office. This gives politicians clear incentives to act on the preferences of their local constituents, which is encouraging for the state of electoral accountability.

However, linking everyday experience to electoral politics is not easy. Voters need to both observe and interpret the consequences of political decisions with adverse local effects before they can turn their attention to identifying the political culprits. Some political processes take decades; for example, the plan to build new “super‐hospitals” was initiated back in 2007, and in 2022 only a handful have been put into use, and in many cases, construction is still ongoing (Ministry of Health, 2021). At the same time, the voters’ task is further complicated by the fact that responsibility for construction projects is shared between the national and regional governments. Thus, I do not find that residents change their support for the incumbent government as a result of the closure of a local hospital. While discouraging for the prospects of direct electoral accountability, these results may reflect the unclear link between an incumbent government and a specific hospital closure. Nevertheless, political decisions with adverse local effects still signal to local communities that the politicians in power do not prioritize people like them. These political decisions substantiate in concrete experiences the message of right‐wing populist parties of a split between “ordinary” people and the political elite. Thus, across electoral levels, I find that support for right‐wing populist parties increases in areas affected by political decisions with adverse local effects. Existing explanations for the rise of right‐wing populist parties have focused on economic and cultural grievances (e.g., Kriesi et al., Reference Kriesi, Grande, Lachat, Dolezal, Bornschier and Frey2006; Gidron & Hall, Reference Gidron and Hall2017). Complementing these explanations, this study shows that mainstream parties also shape the mobilization possibilities of right‐wing populist parties. Faced with experiences of indifference, neglect, or outright cutbacks, people turn to right‐wing populist parties that promise to give power back to “the people.”

In recent years, governments across Western democracies have launched policy initiatives to alleviate the challenges and frustrations of rural and declining regions (e.g., Agenzia per la Coesione Territoriale, 2021; The Danish Government, 2021; The White House, 2022; UK Government, 2022). The findings of this study suggest that such initiatives can alleviate residents’ frustrations. However, it is worth remembering that the studied political decisions with adverse local effects were motivated by depopulation and efforts to improve the quality and efficiency of public service delivery. It is therefore important to recognize that dealing with the development of rural and declining regions involves real trade‐offs between the interests of those who have left and those who are left behind.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful for helpful feedback and advice from Søren Serritzlew, Kim Mannemar Sønderskov, Daniel Hopkins, Omer Solodoch, Frederik Hjorth, Peter Thisted Dinesen, Martin Vinæs Larsen, Katherine J. Cramer, and members of the Political Behavior and Institutions Section at the Department of Political Science, Aarhus University, and for the helpful comments and suggestions from the four anonymous reviewers. Any remaining errors are my own. I would also like to thank Kim Mannemar Sønderskov and Peter Thisted Dinesen for sharing data on covariates at the zip‐code level. Replication material to reproduce the figures and tables presented in this article is available in the Harvard Dataverse, at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/Y327PQ

Online Appendix

Additional supporting information may be found in the Online Appendix section at the end of the article:

Appendix A: Sensitivity of results to flexible choices

Appendix B: Effect of political decisions with adverse local effects on support for other political parties

Appendix C: Full regression tables for models in figure 4, 5, 6, and 7

Appendix D: Data Collection Procedures for School and Hospital Closures

Appendix E: Balance on covariates and descriptives

Appendix F: Supplemental analysis of the effect of political decisions with adverse local effects on turnout and the number of eligible voters