Introduction

In early 2024, Slovenian politics and society witnessed some important developments. In the middle of January, the powerful doctors’ trade union, Union Fides, launched a strike that, despite marking events for several months, later in the year faded away, even though it had not been formally cancelled. In contrast, the protest by the judges soon stopped, albeit they had to wait another six months for a solution to the problem that had triggered the protest (see Krašovec Reference Krašovec2024; M. Z. & A. K. K. 2024; STA 2025).

Along with the protest by judges, the Minister of Justice had to deal with a corruption(-risk) scandal related to the purchase of a new judicial building on Litijska Street. Although the scandal saw the minister resign, this only came after she had thrown the coalition government into turmoil by refusing to heed her party's call to step down and blamed her party (Social Democrats–SD) and its members for the controversy. At first, the Prime Minister insisted on clarifying the situation before considering removing the minister. This move forced the leader of SD to publicly warn the PM that the coalition could find itself in a serious situation (Slovenia Times 2024a).

Unsurprisingly, in February and March, just 13 per cent of voters assessed the government's work as (very) positive. Support for the government later started to grow in May, June and July, exceeding 20 per cent (Delo 2024). It seems that for a while, the change in SD leadership in April and the four consultative referenda held in June (see Elections Report) were reflected in greater support for the government.

The energy reform law was passed in April, and some parties sought to make it an important issue by linking it to the question on the freedom to choose how to heat one's homes (Slovenia Times 2024b). But, it was the new, complicated system of electricity network charges, passed in November, that provoked real anger among the population due to higher costs in winter and the evident chaos in the government caused by the issue (G. C. et al. 2024).

Another development in the energy sector marked politics in autumn. In October, all parties, except for The Left, supported the calling of a consultative referendum on the construction of a new unit at the Krško nuclear power plant. Nuclear and renewable energy were exposed as the most important long-term measure for assuring a stable energy supply in the transition away from fossil fuels. Opponent non-governmental organisations (NGOs) argued that the referendum would be premature since voters did not have enough information to make an informed decision, meaning the referendum would therefore give the government carte blanche for the project. Moreover, the referendum question (Do you support implementation of the Krško 2 project, which will ensure a stable supply of electricity together with other low-carbon sources?) was criticised for being suggestive and manipulative (Slovenia Times 2024c).

A leaked wiretap showed that the two biggest parties, one in government (Freedom Movement–GS) and one in the opposition (Slovenian Democratic Party–SDS) had colluded to circumvent legal concerns with the referendum question. The wiretap namely showed that the parliamentary legal office had warned parties that a consultative referendum could exclusively be about a question the National Assembly had not yet decided on; however, in May, the Assembly still went on to adopt a resolution on the expansion of the Krško nuclear power plant and then called a referendum on the Krško 2 plant. The wiretap revealed representatives of both parties discussing how to get the resolution and referendum through procedurally (Slovenia Times 2024d). Notwithstanding that the SDS member had presented this as mere normal coordination by parliamentary parties, a feeling emerged among the public that politics was not being transparent, especially since several calls had been issued that the project could cause Slovenia to go bankrupt. These events led all parliamentary parties to call the referendum off. In autumn, these developments contributed to a fresh fall in the assessment of the government's work as (very) positive (14 per cent in November).

Just one big promised reform was concluded in 2024: of the public sector wage system where the government and trade unions reached an agreement in November. The reform assured some changes but mostly higher salaries for public employees partly to be introduced immediately and partly in the following years (M. Z. et al. 2024). This achievement is probably responsible for the higher assessment of the government's work as (very) positive (up to 17 per cent) at the end of the year.

Election report

In 2024, one election and four consultative referenda were held, all on the same day.

European parliamentary elections

Eleven candidate lists competed at the EP elections on 9 June. Despite discussions to form a joint list of all three Slovenian members of the European People's Party (SDS, New Slovenia–NSi, Slovene People's Party–SLS), they failed to reach an agreement. All parties eventually formed their own lists.

The formation of candidate lists generated much discussion within governmental parties, notably on the question of the order of appearance (first, second and last place) on the list. It was striking that the GS already announced the Slovenian candidate for EU Commissioner (former President of the Court of Auditors Tomaž Vesel, who later was not accepted to the position by the European Commission President), as well as who would run in the elections for the party, but failed to determine the order of the list until the very last moment (Haughton & Krašovec Reference Haughton and Krašovec2024).

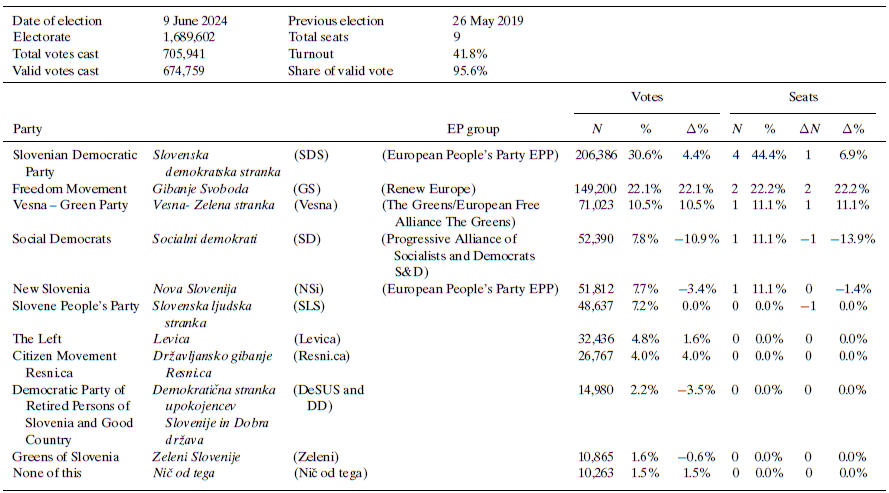

Information on elections to the EP in Slovenia in 2024 can be found in Table 1.

Table 1. Elections to the European Parliament in Slovenia in 2024

Notes:

1. In 2019, SDS had a joint list with SLS; one MEP was from SLS.

2. In 2019, SLS had a joint list with SDS; one MEP was from SLS.

3. In 2019, DeSUS and DD did not have a joint list; DeSUS received 5.7% and DD 0.5%. Calculation here for DeSUS.

While The Left could not hope to become a member of the EP for the first time, the SD had had representatives in all EP terms. However, the latter was weakened by the above-mentioned corruption(-risk) scandal (see also Cabinet Report for further details), with opinion polls showing it was on the cusp of entering the EP. The NSi was also on the cusp of entering the EP (M. R. 2024) and became the only parliamentary party to decide that its leader would run at the elections.

Migration was a prominent theme during the elections, where especially the SDS, NSi and SLS played on this card, while the EU's Green Deal was another important issue.

The SDS was keen to use the EP elections to send a strong message about the incumbent government's unpopularity, even declaring the elections would act as a wake-up call (Haughton & Krašovec Reference Haughton and Krašovec2024). Indeed, the SDS was the clear winner with four seats, while the GS secured two, the NSi and SD each secured one, and one seat was won by the non-parliamentary Vesna–Green Party, which had decided to join forces with the popular local mayor of Kočevje, Vladimir Prebilič, who was a surprise at the presidential elections in 2022 (see Krašovec Reference Krašovec2023). He was placed at the top of the list.

Turnout was the highest ever for EP elections in Slovenia (42 per cent; at earlier elections, it was below 30 per cent). This can also be attributed to the fact that simultaneous to the elections, four consultative referenda were being held.

Referenda

In 2024, parliamentary parties voiced many ideas about holding consultative referenda, with even 15 being proposed, 10 of which had been proposed by the end of April with the goal to be held close to or at the same time as the EP elections. The referenda may thus be seen as a tool for mobilisation given that simply proposing them a few months ahead of the elections helped to raise the profile of issues/parties.

Only four referenda, proposed by governmental parties, were held in the end. It was often claimed in public that these referenda were intended to especially mobilise more left, libertarian voters. Among others, the centre-right opposition had proposed consultative referenda on the mentioned energy reform law, on accommodation for illegal migrants, the regulation of mandatory drug testing of members of Parliament, and even trust in the government (Državni zbor 2025).

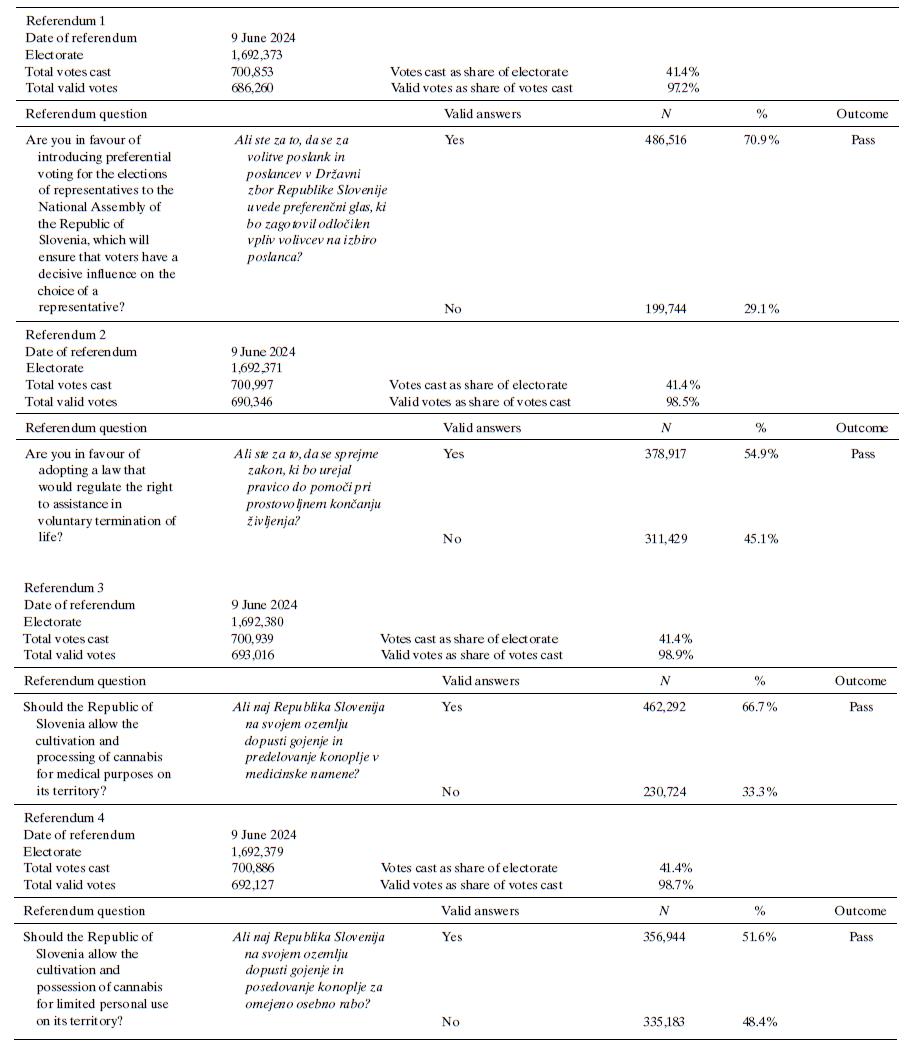

Information on four referenda held on 9 June 2024 in Slovenia can be found in Table 2.

Table 2. Results of four referenda held on 9 June 2024 in Slovenia

At the referenda, the largest support (71 per cent) was received by a proposal that had been debated for years; namely, the introduction of a preferential vote system to ensure that voters could have a more decisive influence on the choice of representative. The lowest support, in comparison, was the barely majority support (52 per cent) shown for the question of whether the cultivation and possession of cannabis for limited personal use should be permitted.

The most debated and polarising topic was on adopting a law that would regulate the right to assistance with the voluntary termination of life. A division emerged between more centre-left and centre-right parties, whereas also some prominent movements were active in the campaign on both sides.

By the end of the year, still not one topic that had been supported at the referenda had been legally regulated.

Cabinet report

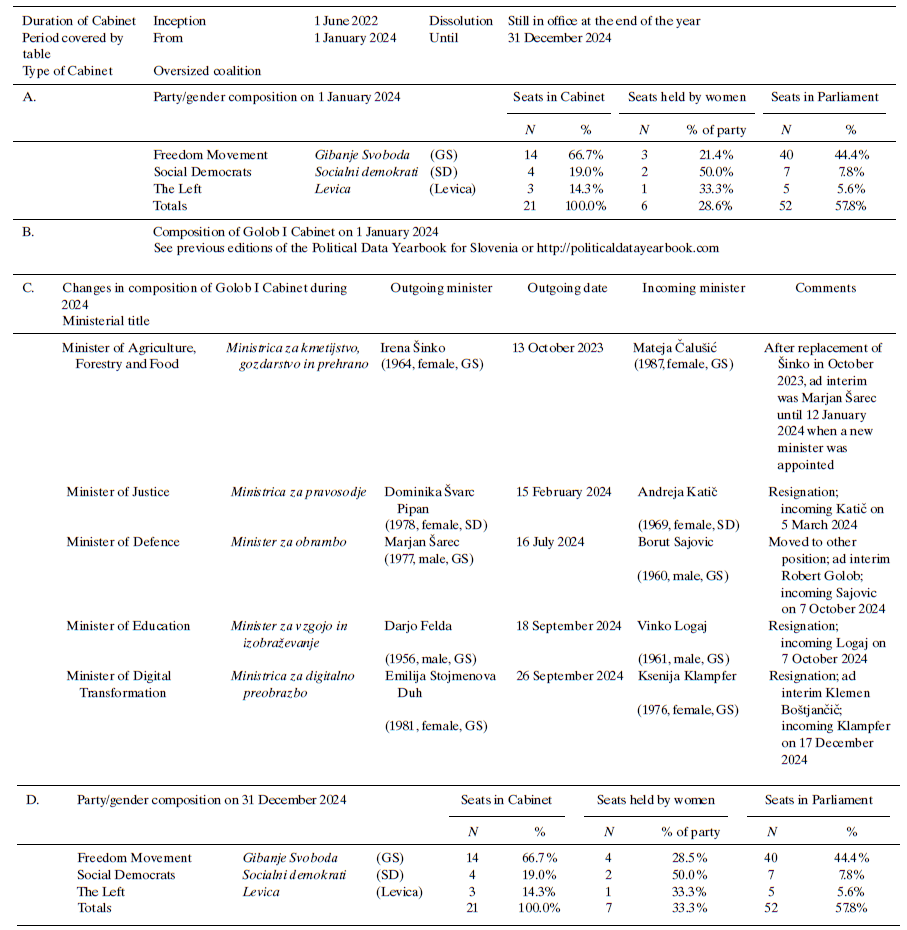

The wave of changes in ministerial positions from 2023 continued in 2024 with four ministers being replaced. One change was because a minister moved to another position—the Minister of Defence and former PM Marjan Šarec (GS), had, to his surprise, been elected to the EP.

Information on the Cabinet composition of Golob I in Slovenia in 2024 can be found in Table 3.

Table 3. Cabinet composition of Golob I in Slovenia in 2024

The parliamentary opposition initiated five interpellations, yet no ministerial change was a direct outcome of this. However, the second interpellation against the Minister of Digital Transformation, Emilija Stojmenova Duh (SD), did influence her decision to resign before the interpellation was discussed in the National Assembly. The first interpellation she faced concerned the purchase and distribution of 13,000 laptops to promote digital inclusion already at the start of the year. The Ministry namely bought the laptops before the terms and conditions had been set as to how and to whom they would be distributed. This led to a situation where the laptops sat in a warehouse for months, racking up costs while the eligibility criteria for applicants were being expanded (Slovenia Times 2024e). This issue continuously featured in the media. After the Court of Auditors found that the laptop procurement ran against the principles of efficiency and economy, the SDS filed a second interpellation against the minister on the same issue of laptops. Nonetheless, the minister's fate was sealed in the end with an incident when her government car was caught using blue emergency lights in Austria without a justifiable reason (Slovenia Times 2024e) and she resigned before the interpellation dealing with the laptops issue was to be discussed in the National Assembly.

Minister of Justice Dominika Švarc Pipan (SD) was involved in the corruption(-risk) scandal concerning the purchase of a new judicial building on Litijska Street and finally resigned before the interpellation was to be discussed in the National Assembly. The scandal was further echoed in an interpellation against Minister of Finance, Klemen Boštjančič (GS), later in the year initiated by the SDS. The Court of Audit's final audit report on the draft final accounts for the previous year's budget revealed issues with the €6.5 million purchase of the Litijska Street premises. The review found that these funds were improperly obtained by moving money from general budget reserves without any valid justification. SDS accused the minister of negligence while in office, mismanagement of public funds, misleading the public during the affair and abuse of power, claiming the minister had lost all credibility and public trust (M. Z. & T. L. Š. 2024).

At the end of 2024, the Administrative Court found that violations in regulations had occurred with the appointment of the Director General of the Police. Many legal experts had also disputed the legality of the appointment, but the government disagreed and continued to keep the Director General in office. This led to an interpellation against the Minister of Internal Affairs, Boštjan Poklukar.

Parliament report

The National Assembly's composition stayed almost the same in 2024, with the only notable changes happening in the SDS. Although members of the Assembly, Anže Logar and two other SDS representatives had been slowly and permanently moving away from the party (see Krašovec Reference Krašovec2024), and in October, they made the final break. In February, the SDS executive committee had proposed that all party MPs sign a statement committing themselves to act as members of the SDS and members of the party's parliamentary group until the end of the legislative term. These three MPs did not sign it. The SDS parliamentary group took another step—it informed the National Assembly of the changes in its members in the Assembly's working bodies. All three were stripped of their membership. The three former SDS MPs did not agree on establishing a new parliamentary party group, as disagreements among them had appeared just prior to their simultaneous exit from the SDS parliamentary party group.

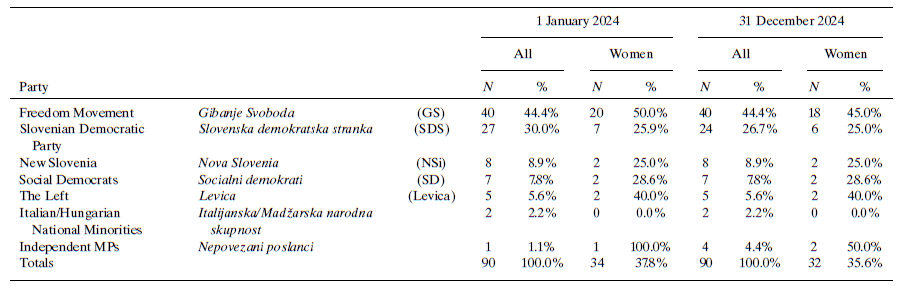

Information on party and gender composition of the lower house of the Parliament (Državni zbor) in Slovenia in 2024 can be found in Table 4.

Table 4. Party and gender composition of the lower house of the Parliament (Državni zbor) in Slovenia in 2024

Source: Državni zbor Republike Slovenije (2025).

The GS also experienced some personnel changes: The experienced parliamentary party group leader Borut Sajovic became the Minister of Defence, another MP (Mateja Čalušić) became the Minister of Agriculture, Forestry and Food and yet another MP (Monika Pekošak) left their position for personal reasons. At the end of the year, opposition parties proposed the dismissal of National Assembly President Urška Klakočar Zupančič (GS). They alleged she had violated the parliamentary rules of procedure concerning a referendum motion that the SDS had proposed and that she had violated laws and the Constitution and engaged in inappropriate conduct. However, not enough MPs voted for her dismissal in the mid-December motion.

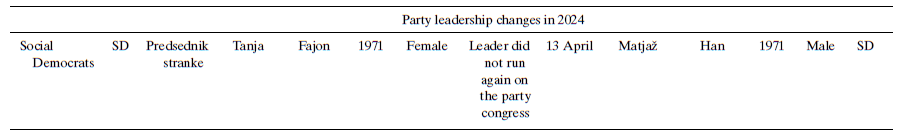

Political party report

Among parliamentary parties, only the SD saw a change in leadership. In the context of the Litijska Street affair, party president Tanja Fajon faced intense criticism and announced that she would not run again at the party congress. After the close battle between then EP Member Milan Brglez and the popular Minister of Economic Development and Technology, Matjaž Han, the latter was elected to the position (Kos & Eržen Reference Kos and Eržen2024).

Information on changes in political parties in Slovenia in 2024 can be found in Table 5.

In the last decade or so, Slovenia has seen multiple very electorally successful new parties emerging just prior to elections (Fink-Hafner & Novak Reference Fink-Hafner and Novak2022; Haughton & Deegan-Krause Reference Haughton and Deegan-Krause2020; Haughton et al. Reference Haughton2024). In 2024, more than one year before the elections, some parties that were thought to hold considerable electoral potential were established. In November, the former SDS MP Logar founded the party Democrats (Demokrati) (see Krašovec Reference Krašovec2024; Slovenia Times 2024f). The former long-term leader of the Democratic Party of Retired Persons of Slovenia (DeSUS), Karl Erjavec, also founded the party Trust (Zaupanje). In December, president of the National Council (the upper house of the Slovenian Parliament) Marko Lotrič announced that, in January 2025, he would create a party named Focus (Fokus). Many rumours also went undenied that Vladimir Prebilič (see also European Parliamentary Elections Report for further details) would set up a party in 2025 (Eržen Reference Eržen2024).

Institutional change report

In April 2023, MPs from the GS, SD and NSi proposed to initiate a procedure to amend constitutional provisions dealing with the nomination, appointment and dismissal of government ministers. Still, more than a year later, the Constitutional Commission of the National Assembly did not support initiating the procedure to amend the Constitution, among other reasons because, by then, the NSi no longer supported it (B. R. 2024). As concerns the announced and already initiated reform regarding the appointment of judges and composition of the Judicial Council (see Krašovec Reference Krašovec2024), no progress was made in 2024.

Issues in national politics

A few developments in the international environment impacted Slovenian politics in 2024.

The events in Gaza accelerated discussions on recognising Palestine as an independent and sovereign state. Just prior to the EP elections, the government and the Assembly took the final step in this respect, despite strong opposition, especially from the SDS. Right before the decision was made in the Assembly, the party proposed to hold a consultative referendum, but the motion was not supported. Many procedural complications were involved in the process (T. K. B. et al. 2024) that led both centre-right opposition parties (SDS and NSi) to ask the Constitutional Court to review Slovenia's recognition of Palestine and to annul it, arguing the parliamentary rules of procedure had been breached in the process. Nonetheless, the Court dismissed the request in October (Slovenia Times 2024g).

In the case of the war in Ukraine, all of the major parties still fundamentally agreed to support Ukraine, despite some differences in views appearing during the year on how to resolve the war in Ukraine.

Compared to the reform of the public sector wage system that was concluded in 2024, the other two big reforms—of the pension and healthcare systems—were moving slowly, albeit one may anticipate they will be completed in 2025.

Concerns arose in 2024 regarding some events connected to independent institutions as instances of (soft) pressure on them were observed. In November, the government reduced the funding of the Court of Auditor as part of a budget amendment. The president of the Court and some MPs claimed the move posed a threat to the independence of the court, which is often critical of the government (M. Z. 2024). In December, the Energy Agency, which had prepared a new system of electricity network charges, received a call from the government that it should return to the old method of calculating network charges and that the agency's management should resign; the director of the Agency saw this intervention as unacceptable political pressure on the independent institution (G. K. 2024). Also in 2024, pressure from the SDS on the judiciary increased noticeably again, particularly due to the trial against its leader Janez Janša on allegedly controversial land deals in Trenta Valley (T. L. Š. & G. K. 2024). Protests by SDS party supporters in front of the courthouse during the trial were arranged, and Janša called again for a mistrial. Furthermore, the alleged home addresses of judicial representatives who were involved in the legal proceedings were published on social media, accompanied by calls for violence (Al. Ma. Reference Al2024).

Prime Minister Golob in 2024 found himself involved in an investigation by the Commission for the Prevention of Corruption with respect to the allegation that he had exerted undue pressure on former Minister of Internal Affairs Tatjana Bobnar over police staffing, which ultimately led to her resigning in December 2022 (see Krašovec Reference Krašovec2023). Later in the year, Golob faced a criminal complaint filed by the Police over alleged interference in police affairs and was accused of committing a crime of corruption (Jochecova Reference Jochecova2024).

In 2024, Slovenia had favourable economic conditions; the average inflation rate decreased a lot—from 7.4 per cent in 2023 to 2.0 per cent in 2024; the average level of unemployment stayed very low at 3.7 per cent in 2024 (in 2022, it was 4.0 per cent); GDP increased in 2024 to 1.6 per cent, while in 2023 this increase was 2.1 per cent (Urad Republike Slovenije za makroekonomske analize in razvoj 2025).