Background

Hoarding disorder (HD) is a ‘difficulty discarding or parting with possessions … due to a perceived need to save the items and to distress associated with discarding them’ and is usually associated with ‘excessive acquisition’ of items (American Psychiatric Association, DSM-5 Task Force, 2013). Previously categorised under the umbrella of obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), it is now considered a distinct psychiatric disorder (American Psychiatric Association, 2013) with a prevalence of approximately 2.5% (Postlethwaite et al., Reference Postlethwaite, Kellett and Mataix-Cols2019). Symptoms of hoarding have been shown to develop in teenage years (Zaboski et al., Reference Zaboski, Merritt, Schrack, Gayle, Gonzalez, Guerrero, Dueñas, Soreni and Mathews2019), becoming problematic around the early 30s (Landau et al., Reference Landau, Iervolino, Pertusa, Santo, Singh and Mataix-Cols2011), yet patients seek treatment on average in their 50s (Muroff et al., Reference Muroff, Bratiotis and Steketee2011; Tolin et al., Reference Tolin, Frost, Steketee and Muroff2015).

The cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) model for HD was first proposed by Frost and Hartl (Reference Frost and Hartl1996), with a diagram later published in Steketee and Frost (Reference Steketee and Frost2006). This model provides psychotherapists with a framework to formulate and understand the difficulties that patients with HD may present in treatment with. The model proposes that hoarding in adults results from ‘aversive early life experiences, such as stressful life events and thought to contribute to problems in information processing, development of maladaptive beliefs about possessions and behavioural avoidance in respond to affect dysregulation’ (Knight et al., Reference Knight, Davies, Salkovskis and Gregory2019), which leads to symptoms such as difficulty discarding items. NICE guidelines provide recommendations for health and social care professionals based on high quality research evidence for available treatment options for mental and physical health conditions. However, there are no NICE guidelines for the treatment of HD (Wootton et al., Reference Wootton, Worden, Norberg, Grisham and Steketee2019), demonstrating a lack of evidence for a particular approach to treatment, including CBT. In general, hoarding symptoms have been found to be difficult to treat. Treatment studies report high drop-out rates and difficulties completing questionnaires and homework tasks (Williams and Viscusi, Reference Williams and Viscusi2016). A review by Tolin et al. (Reference Tolin, Frost, Steketee and Muroff2015) examined reliable change (defined as change in the outcome measure being significantly greater than that expected by chance, given the test–retest reliability of the measure) and clinically significant change (defined as post-treatment scores that better match the distribution of scores in the general population than in a hoarding population) in order to review efficacy of CBT for HD. They found that although the effect sizes for reliable changes in symptoms were high, only 24–43% of people with HD demonstrate clinically significant change (Tolin et al., Reference Tolin, Frost, Steketee and Muroff2015). An updated meta-analysis also found large effect sizes for reliable change, following publication of additional articles (Rodgers et al., Reference Rodgers, McDonald and Wootton2021), but did not report results regarding clinically significant change. Rodgers et al. (Reference Rodgers, McDonald and Wootton2021) also identified the impact of additional variables, such as studies with higher rates of female participants having higher effect sizes. Overall, these reviews showed that whilst CBT can contribute to a significant reduction of symptoms in HD, not all improvements have been clinically significant (Williams and Viscusi, Reference Williams and Viscusi2016).

The CBT model emphasises the importance of beliefs about items in the onset and maintenance of hoarding behaviours. This has been supported by evidence demonstrating that changes in beliefs related to saving items in HD mediates changes in symptoms during CBT (Levy et al., Reference Levy, Worden, Gilliam, D’Urso, Steketee, Frost and Tolin2017). These are measured using two instruments, the Saving Cognitions Inventory (SCI; Steketee et al., Reference Steketee, Frost and Kyrios2003) and the Beliefs About Hoarding measure (BAH; Gordon et al., Reference Gordon, Salkovskis and Oldfield2013).

The SCI includes beliefs about emotional attachment, memory, control and responsibility. Items were initially created by the researchers based on their clinical experience and previous research into beliefs in hoarding. Although the measure of Steketee et al. (Reference Steketee, Frost and Kyrios2003) reported very good internal consistency, no further measure development studies have been conducted using this questionnaire to confirm reliability or explore the validity of the SCI within clinical or research settings.

To capture different groups of beliefs which were felt to be missing from the SCI, a later group of researchers developed the BAH. This includes beliefs about harm avoidance, material deprivation, and attachment disturbance, and was developed to compare beliefs between people experiencing hoarding with or without OCD. The items were developed by the researchers, and they did not report using factor analysis to determine item retention. Gordon et al. (Reference Gordon, Salkovskis and Oldfield2013) hypothesised that people with hoarding and OCD would report greater harm avoidance beliefs, whereas people with hoarding without OCD would report greater material deprivation and attachment disturbance beliefs. The findings did not fully support these hypotheses, with the hoarding and OCD group reporting greater beliefs on all three subscales compared with the sample experiencing hoarding without OCD. The reliability and validity data for the BAH is limited to internal consistency and a small sample of test–retest reliability in the original study (Gordon et al., Reference Gordon, Salkovskis and Oldfield2013).

A recent literature review demonstrated that beliefs around identity are present in a proportion of people with HD that have not been conceptualised as part of the CBT model for HD before (Tinlin et al., Reference Tinlin, Hillman, Gregory and Lomax2019), nor are they included in the BAH or SCI. For example, Tinlin et al. (Reference Tinlin, Beckwith, Gregory and Lomax2022) identified a range of beliefs about hoarding from interviews and existing literature. When participants were asked which beliefs they felt most strongly, four belief profiles emerged from the data: identity; morality and responsibility; stability and predictability; and objects as emotional and meaningful beings. Participants who held beliefs about hoarding that related to identity, such as, ‘The things I have are a part of who I am – they are extensions of my identity’, demonstrated that some people with HD keep objects because those items represent memories, achievements, hopes and dreams from their life. Participants that fit this profile differed from other participants in the study, who preferred beliefs from other profiles, such as stability (‘Items are stable, unchangeable and certain amongst the chaos’). Beliefs about identity have also been highlighted as important in HD (Kings et al., Reference Kings, Knight and Moulding2018, Reference Kings, Moulding, Yap, Gazzola and Knight2021).

Therefore, developing a new clinical tool to support the identification of specific patterns of beliefs in HD may potentially support more detailed assessment of the beliefs that people hold about their items. In practice, this may enable clinicians to then individualise treatment more effectively by identifying specific belief categories which are maintaining the difficulties for each individual, which would involve a different focus for treatment and different interventions. Ensuring that themes which have failed to be identified by existing assessment tools, but are now included within this measure, may also indicate a need to update the CBT model for HD, inform treatment, and develop our understanding of HD. Improving treatment for HD may consequently also increase the physical safety of service users and those around them (as they are at higher risk of house fires, infestation, or accidents) and reduce the impact on emergency services who can struggle to access their property (Chartered Institute of Housing, 2015).

Aims and objectives

This project aimed to develop a clinical measure that could be used in routine assessment and formulation of HD. The current measures of beliefs in HD have been shown to be missing a key theme of identity (Tinlin et al., Reference Tinlin, Beckwith, Gregory and Lomax2022) and this research aims to develop a measure which incorporates this domain. The objectives are to:

-

(1) Develop an assessment tool measuring the presence and strength of beliefs in hoarding disorder.

-

(2) Analyse responses from a sample of participants meeting criteria for hoarding disorder (based on a diagnostic measure of hoarding disorder) using factor analysis to identify subtypes of beliefs and refine the tool for clinical use.

Method

Design

Ethical approval for this project was provided by Newcastle University (ref: 4326/2020). This study used a single group within-subject cross-sectional design. There were two phases to the methodology. Phase 1 aimed to develop a list of beliefs that have been identified in previous literature (Gordon et al., Reference Gordon, Salkovskis and Oldfield2013; Steketee et al., Reference Steketee, Frost and Kyrios2003; Tinlin et al., Reference Tinlin, Beckwith, Gregory and Lomax2022) as being present in hoarding disorder. This list would then be reduced to a shorter length, whilst retaining all identified themes of beliefs, to be developed into a questionnaire format. The aim of the questionnaire was to measure the strength of a respondent’s beliefs around reasons for acquiring, keeping and not discarding objects. Phase 2 aimed to present this list of beliefs in hoarding disorder to a sample of people experiencing problems with hoarding to identify which beliefs are most likely to occur together, and further reduce the questionnaire to manageable length for use in clinical practice.

Phase 1

Procedure

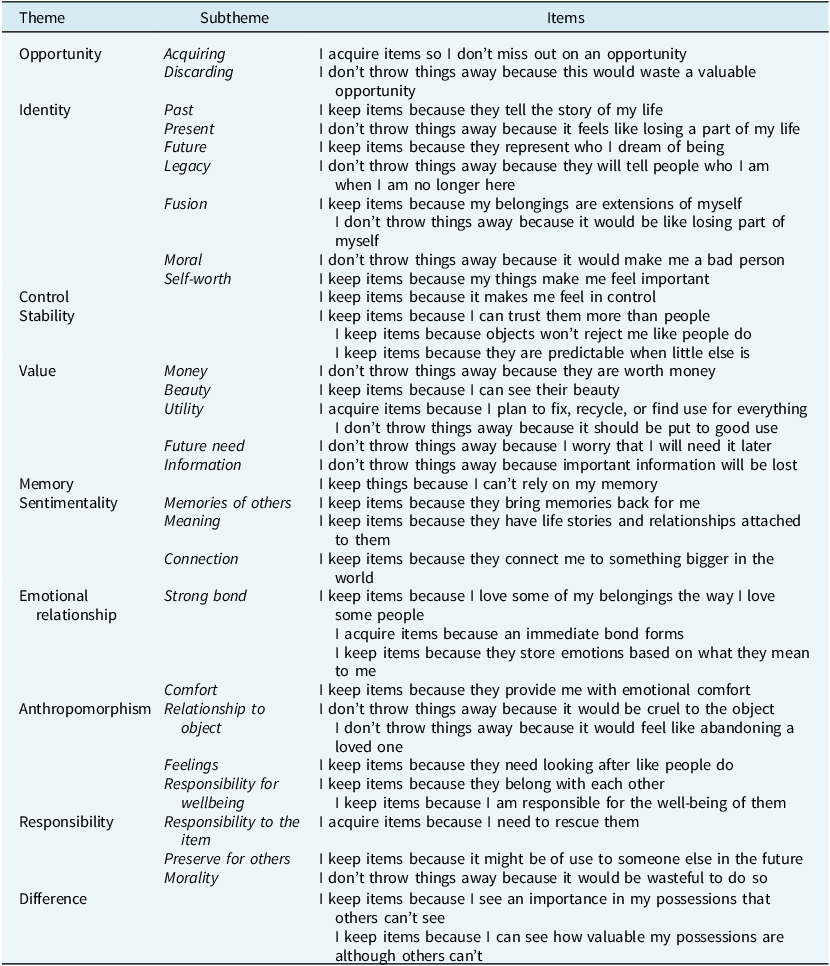

All of the statements from the BAH (Gordon et al., Reference Gordon, Salkovskis and Oldfield2013), SCI (Steketee et al., Reference Steketee, Frost and Kyrios2003), and the belief profiles (Tinlin et al., Reference Tinlin, Beckwith, Gregory and Lomax2022) were listed together for review (n=98). All authors then reviewed the list as a team and categorised the items into broad themes. Any items that were duplicated either had their wording merged to make one item, or after discussion if it was felt that one of the items had clearer wording the other similar item was removed. For example, ‘Throwing some things away would feel like abandoning a loved one’ (from the SCI) and ‘If I get rid of this item it is like abandoning someone I love’ (from the BAH) had the wordings merged to be represented in the final themes as ‘I don’t throw things away because it would feel like abandoning a loved one’. As this study aimed to develop a measure of beliefs in hoarding, items from the list that focused on OCD symptoms or described affect rather than cognition were removed. For example, the harm avoidance subscale from the BAH, which includes items like ‘This will cause someone harm unless I keep it’, was removed because these items represent intrusive thoughts present in OCD. Additionally, items like ‘It upsets me when someone throws something of mine away without my permission’ (from the belief profiles) was removed due to describing an emotional reaction rather than a belief about hoarding behaviour. To ensure breadth and reduce researcher subjectivity, two or three statements per theme were included, with no clear duplication. Where it was unclear if two items covered the same belief concept, both were included to allow factor analysis to identify any association between them. All items chosen for inclusion were reworded to ensure that only one belief was described by each statement, and to create a consistent grammatical structure for each item. For example, ‘items tell the story of my life – who I am and what I have done’ from Tinlin et al. (Reference Tinlin, Beckwith, Gregory and Lomax2022) was rephrased to ‘I keep items because they tell the story of my life’. The final items from this stage (n=38) are included in Table 1.

Table 1. Belief themes and items included in the initial draft

Measures

The items were taken from existing measures which cover a range of beliefs regarding the acquisition of and difficulty discarding objects in hoarding disorder.

Beliefs About Hoarding

The BAH (Gordon et al., Reference Gordon, Salkovskis and Oldfield2013) is a self-report measure designed to assess beliefs and experiences of hoarding, based on the Frost and Hartl (Reference Frost and Hartl1996) definition of hoarding. The BAH consists of 28 items with three subscales (harm avoidance/responsibility, previous experience of material deprivation, and attachment disturbance). The measure asks participants to rate how much they believe each item on a scale from 0 (‘I did not believe this at all’) to 100 (‘I was completely convinced this idea was true’). Ratings can be totalled to give an overall score, with mean scores reported for each subscale. The measure was shown to have good reliability in the initial development, with high internal consistency overall (α=.96) and good test–retest reliability (r=.83). Further reliability and validity tests for the BAH have not been reported.

Saving Cognitions Inventory

The SCI measures attitudes and beliefs among ‘individuals with compulsive hoarding’ (Steketee et al., Reference Steketee, Frost and Kyrios2003; p. 465) based on the Frost and Hartl (Reference Frost and Hartl1996) model and additional research by the authors (e.g. Frost et al., Reference Frost, Hartl, Christian and Williams1995). This measure includes 24 items with the following subscales: Emotional Attachment (10 items), Memory (5 items), Control (3 items), and Responsibility (6 items). Participants are asked to rate how much each item influences their decision about whether to discard a possession, using a 7-point Likert scale. The original paper reported high internal consistency for the SCI (α=.96), as well as concurrent validity (p<.0014) with the Savings Inventory. Further reliability and validity tests have not been reported for this measure.

Belief profiles

The items included from the belief profiles of Tinlin et al. (Reference Tinlin, Beckwith, Gregory and Lomax2022) were identified from interviews with clinicians, researchers, and individuals with HD, in addition to beliefs reported in research into the lived experience of people with HD. Tinlin et al. (Reference Tinlin, Beckwith, Gregory and Lomax2022) included 46 items to develop the belief profiles and these were the statements used in phase 1 of this study.

Feedback

A working group (n=9) was consulted to assist in deciding on the most appropriate and acceptable format of the measure. This group included people who had experienced HD (n=3), clinicians working with people experiencing HD (n=3), and UK researchers who have published research into hoarding (n=3). The working group were known to the research team from previous engagement or consultation in hoarding research at the host university and were individually invited to provide feedback on the draft measure. Participants from the working group were provided with a copy of the initial measure and a feedback form that asked them to comment on: different response options (e.g. a range of Likert scales), language used (e.g. do you identify more with the word possession, item, object?), the format of the measure (e.g. is the layout appropriate?; where should the Likert scale be positioned for each statement?) and the face validity of the beliefs (e.g. do you endorse these beliefs?; are there any missing from the measure?).

All members of the working group agreed that the instructions provided for completing the measure were appropriate and therefore they were not edited. Individual members of the working group suggested additional items for beliefs that had not been included, and therefore two additional items were added during this phase: ‘I keep items around me because they keep me safe’ and ‘I don’t discard items because this might hurt them’. Some of the language of the items was changed based on suggestions from individuals. Most of the working group stated a preference for the term ‘possessions’. However, the research team made the decision to use the word ‘items’ instead of ‘possessions’ to reduce the required reading age for the measure. The team also felt that items was a broader term to describe any objects that had not yet come into an individual’s ownership.

The reading age of the measure was calculated by Microsoft Word. For the BIHD, the Flesch Reading Ease Score is 80.1 (0–100 scale, higher is easier) and the Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level is 4.9 (US school grade), indicating that the text is generally understandable by an average 5th grader in the United States (typically 9–10 years old). These measures take into consideration the length of sentences and the number of syllables in words included in the text to calculate readability (Hayes et al., Reference Hayes, Jenkins and Walker1950). The aim of a low reading age was to improve overall accessibility of the measure but also takes into consideration that there are often co-morbidities alongside hoarding disorder that may make reading and comprehension more difficult, such as autism (Storch et al., Reference Storch, Nadeau, Johnco, Timpano, McBride, Mutch, Lewin and Murphy2016), attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) (Fullana et al., Reference Fullana, Vilagut, Mataix-Cols, Adroher, Bruffaerts and Bunting2013), and cognitive impairment (Roane et al., Reference Roane, Landers, Sherratt and Wilson2017).

All members of the working group agreed that a 5-point Likert scale was preferable. A 5-point scale was chosen to provide a middle option and enough strength in either direction, without providing too many options, where the difference between points feels unclear or arbitrary. It has been reported that people with HD can have problems with attention or information processing (Gledhill et al., Reference Gledhill, Bream, Drury and Onwumere2021) and so this was also considered when choosing to use a 5-point scale.

Although the measure was initially trialled online, formatting changes were made based on feedback from individuals in the working group to create a design for a paper-based survey that was a portrait layout and provided clear visual cues to support participants when rating the beliefs.

Phase 2

Participants

Adults who self-identified as having hoarding disorder were invited to complete the assessment tool developed in phase 1 online. Participants were recruited online and in collaboration with national and international mental health organisations. Social media platforms, such as Facebook, Twitter and Reddit, and a university research participation scheme were also used to advertise the project for recruitment. Recruitment was not limited to certain countries, although the eligibility required participants to be able to understand English.

There is wide debate on what constitutes an adequate sample size for factor analysis and there is no one-size-fits-all approach (Osborne and Fitzpatrick, Reference Osborne and Fitzpatrick2012). This phase of the study aimed for five participants per item included in the factor analysis (Kass and Tinsley, Reference Kass and Tinsley1979), requiring a minimum sample size of 200 participants. It has been argued that a sample size of over 200 can provide adequate power (Hoe, Reference Hoe2008), particularly for measures with up to 40 items (Comrey, Reference Comrey1988) and would be evaluated as ‘fair’ by Comrey and Lee (Reference Comrey and Lee1992). There were 482 people that responded to the advert and completed the initial screening. Of these, 240 participants met the eligibility criteria and were invited to continue in the study. Overall, 226 participants met the criteria and completed all of measures (see Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Flow chart of participation. Exclusions are indicated by a dotted line. Final sample is indicated by a continuous line.

Procedure

Participants were provided with a link to the questionnaire, which included the project information sheet and requested consent. Participants that consented completed demographic questions and the HRS-SR. Participants who scored below 14 on the HRS-SR were screened out and did not complete further questions. Participants who met the clinical threshold on the HRS-SR (Frost et al., Reference Frost, Tolin, Steketee, Fitch and Selbo-Bruns2009; Nutley et al., Reference Nutley, Bertolace, Vieira, Nguyen, Ordway, Simpson, Zakrzewski, Camacho, Eichenbaum and Nosheny2020) completed the OCI-4, PHQ-2 and GAD-2 and the new Beliefs about Items in Hoarding Disorder measure. Participants were provided with debriefing information which included where they can seek help, support, or more information at the end of the survey. Those that completed the full survey were offered the opportunity to enter a prize draw for a shopping voucher or to earn course credits. Participants who wished to enter the prize draw provided their email address at the end of the study and five were selected using a random number generator to receive a £20 shopping voucher.

Demographics

Participants provided their age, gender, ethnicity and country of residence. They reported their relationship, employment and housing status. Participants then self-reported a diagnosis of hoarding disorder before completing a screening measure. This information was gathered to assist in accurately describing the sample.

Screening measure: Hoarding Rating Scale

The Hoarding Rating Scale-Self-Report (HRS-SR; Nutley et al., Reference Nutley, Bertolace, Vieira, Nguyen, Ordway, Simpson, Zakrzewski, Camacho, Eichenbaum and Nosheny2020; Tolin et al., Reference Tolin, Frost and Steketee2010) was used to screen participants for participation, using a threshold of 14 or higher (Frost et al., Reference Frost, Tolin, Steketee, Fitch and Selbo-Bruns2009; Nutley et al., Reference Nutley, Bertolace, Vieira, Nguyen, Ordway, Simpson, Zakrzewski, Camacho, Eichenbaum and Nosheny2020). The HRS-SR includes five questions rated on a 9-point Likert scale (0–8), ranging from ‘not at all difficult’ to ‘extremely difficult’, indicating the level of difficulty experienced due to acquiring unneeded items. This measure is a valid assessment of hoarding behaviour when delivered online, with high concordance to HD diagnoses determined by clinical interviews and other self-report measures of hoarding. The HRS-SR demonstrates reliability over time, with correlations between time points ranging between r=.88 and r=.92 (Nutley et al., Reference Nutley, Bertolace, Vieira, Nguyen, Ordway, Simpson, Zakrzewski, Camacho, Eichenbaum and Nosheny2020).

Measures of co-morbidity

The Ultra-Brief Obsessive Compulsive Inventory (OCI-4; Abramovitch et al., Reference Abramovitch, Abramowitz and McKay2021) was used to measure the level of OCD symptoms in participants, as there is co-morbidity between OCD and HD, as well as hoarding behaviours as a symptom of OCD. The two-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-2; Kroenke et al., Reference Kroenke, Spitzer and Williams2003) and two-item Generalised Anxiety Disorder measure (GAD-2; Kroenke et al., Reference Kroenke, Spitzer, Williams, Monahan and Löwe2007) were used to measure symptoms of depression and anxiety in the population. Using the short forms of these additional measures aimed to reduce the burden on participants that can be caused by requesting completion of a large battery of self-report measures. By gathering this information, the aim was to provide more description of the participant sample, as well as to demonstrate that the measure has been completed by people with expected co-morbidities.

The OCI-4 retains the four most important items from the 18-item Obsessive-Compulsive Inventory-Revised (OCI-R; Foa et al., Reference Foa, Huppert, Leiberg, Langner, Kichic, Hajcak and Salkovskis2002) needed to discriminate people with OCD from healthy controls whilst maintaining comparable convergent and divergent validity to the OCI-R. Hoarding items are not included in the OCI-4. Items use a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (not at all) to 4 (very much) to rate the level of distress associated with each item. The best balance of sensitivity and specificity has been identified at a threshold of ≥4. Test–retest reliability demonstrates adequate stability (Abramovitch et al., Reference Abramovitch, Abramowitz and McKay2021).

The PHQ-2 reduces the 9-item PHQ (Kroenke and Spitzer, Reference Kroenke and Spitzer2002) to measure symptom severity for depression. The GAD-2 reduces the 7-item GAD (Spitzer et al., Reference Spitzer, Kroenke, Williams and Löwe2006) to measures severity for anxiety disorders. Both use the first two questions of the longer measures, which best match the core criteria for depression and anxiety, respectively. Item ratings use a 4-point Likert scale (0 to 3), with higher scores indicating higher severity. Discriminant validity was excellent for the PHQ-2, and acceptable for the GAD-2. Acceptable sensitivity and specificity were identified at a threshold of ≥3 for both measures (Staples et al., Reference Staples, Dear, Gandy, Fogliati, Fogliati, Karin, Nielssen and Titov2019). These measures were included to provide more description of the participant sample, as well as to demonstrate that the measure in development has been completed by people with expected co-morbidities.

Measure of Beliefs in Hoarding Disorder (BIHD)

The final measure used in this phase was the tool in development. Participants rated the strength of their belief on a 5-point Likert scale (I believe this: not at all to very strongly) for each of the 40 items (Table 1). A Likert scale was used to allow measurement of the strength of the participant’s belief, not just the presence of the belief. The order of items was randomised using a random number generator in Excel but were presented in the same order to all participants.

Data analysis

Using a programme designed for factor analysis, called ‘Factor’ (Ferrando and Lorenzo-Seva, Reference Ferrando and Lorenzo-Seva2017), exploratory factor analysis was conducted to examine the internal consistency of the measure. Polychoric correlations between items informed which items should be retained in the final tool and which could be removed to reduce the tool to an appropriate length, whilst accurately identifying the type of beliefs that the client holds about their hoarding behaviour. A promin rotation was used (Lorenzo-Seva, Reference Lorenzo-Seva1999), as an oblique method is recommended when expecting a level of correlation between factors. Parallel analysis based on minimum rank factor analysis was used to recommend the number of dimensions, and this was confirmed by eigenvalues greater than or equal to 1. Examining the factor structure of the data, together with the current evidence base (Gordon et al., Reference Gordon, Salkovskis and Oldfield2013; Tinlin et al., Reference Tinlin, Beckwith, Gregory and Lomax2022), allowed for relevant subscales to be developed and the final items to be chosen.

Results

Sample characteristics

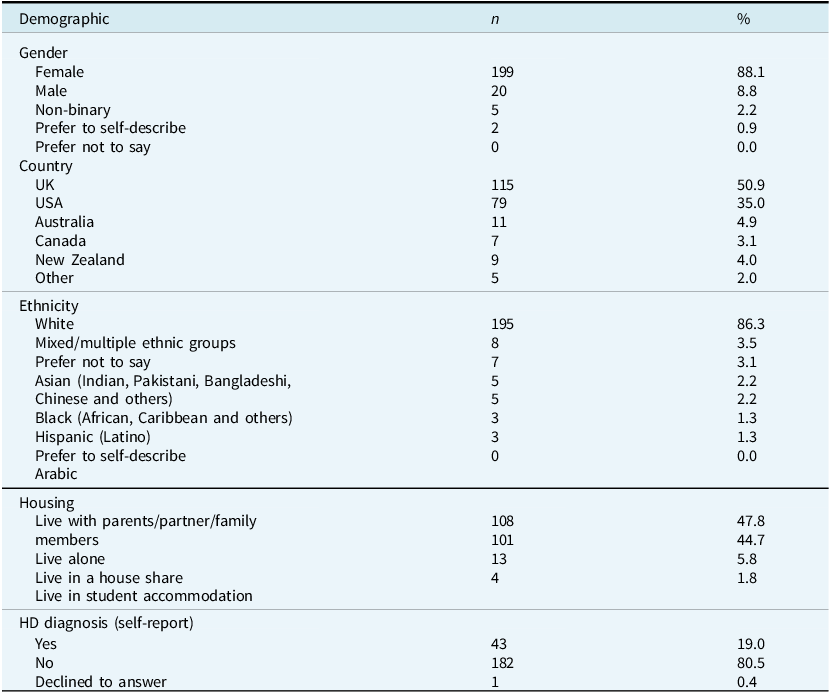

Of the 482 participants that completed the HRS, 47% scored 14 or higher (n=226, M=24.37, SD=6.55) and were invited to continue the questionnaires (Fig. 1). The final sample was aged between 18 and 79 years old (M=50, Mdn=50, mode=49). Ten participants (2%) were local university students who completed the questionnaires in exchange for course credits. Demographic information is displayed in Table 2. Data for co-morbidities are available in the Supplementary material.

Table 2. Demographic characteristics

Factor analysis

Forty items were entered into Factor (Ferrando and Lorenzo-Seva, Reference Ferrando and Lorenzo-Seva2017). There were four data items missing from the dataset, where participants had failed to respond to an item in the Beliefs about Items in Hoarding Disorder (BIHD). These missing data items were managed using Hot-Deck Multiple Imputation in Exploratory Factor Analysis (Lorenzo-Seva and Van Ginkel, Reference Lorenzo-Seva and Van Ginkel2016). Hot-deck imputation replaces missing values from one participant with the observed values from another participant with similar characteristics. Although the data were not significantly skewed (p=1), there was a significant level of kurtosis (p<.001; Mardia, Reference Mardia1970). Therefore, polychoric correlations were used, rather than a Pearson correlation matrix (Muthen and Kaplan, Reference Muthen and Kaplan1992), which assumes that the factors are correlated with each other and not completely separate. The correlation matrix was not positive definite and item 33 was recommended for removal by Factor to resolve this (Ferrando and Lorenzo-Seva, Reference Ferrando and Lorenzo-Seva2017).

A four-factor structure was initially suggested based on the four factors found by Tinlin et al. (Reference Tinlin, Beckwith, Gregory and Lomax2022). However, parallel analysis based on minimum rank factor analysis (Timmerman and Lorenzo-Seva, Reference Timmerman and Lorenzo-Seva2011) recommended three dimensions. This method adjusts for sampling errors that can occur if using the eigenvalue criteria and can be used to estimate the explained common variance for each factor. A three-factor model was therefore also considered.

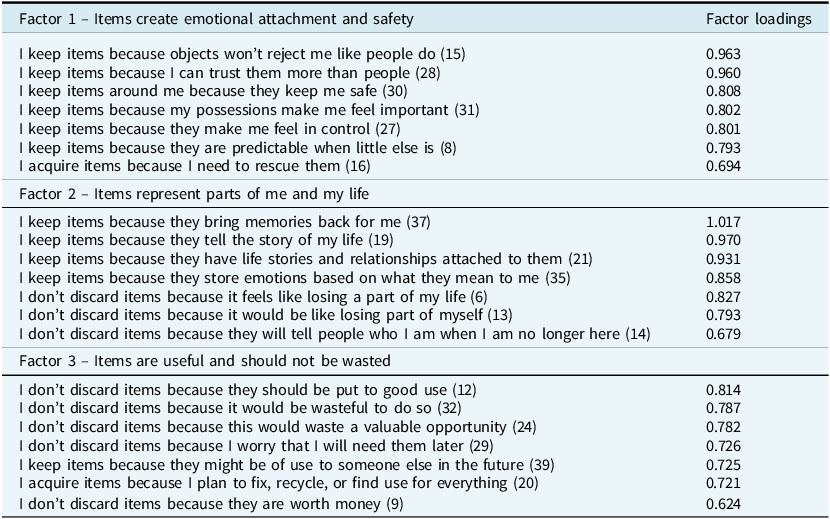

Both the three- and four-factor models were reduced to approximately 20 items by removing the lowest loading items. Factor analysis was conducted again, to provide further evidence for a factor structure for a shorter measure. Three dimensions were again recommended in all parallel analyses based on minimum rank factor analysis. When reduced to 18 items (6 items per factor), the Measure of Sampling Adequacy (MSA) values indicated that four items were below .50 and should be removed (Lorenzo-Seva and Ferrando, Reference Lorenzo-Seva and Ferrando2021). However, with 21 items (top 7 loading items per factor), the MSA values indicated that all 21 items should be retained, and these were the factors and items used for the final version of the measure (Table 3).

Table 3. Retained items

Numbers in parentheses refer to the position of the item in the original item list presented to participants.

There are several statistical tests that are used to provide evidence for whether a factor structure is appropriate and acceptable. The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin Measure of Sampling Adequacy indicates if factor analysis may be appropriate for the data. Values range from 0 to 1, with higher values indicating that the sample is adequate for factor analysis. The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin test in this study was high (KMO=.85), indicating that the sampling was adequate (Kaiser and Rice, Reference Kaiser and Rice1974). There were three eigenvalues greater than 1, which is the traditional method for identifying the number of factors, confirming the optimal implementation of parallel analysis (Timmerman and Lorenzo-Seva, Reference Timmerman and Lorenzo-Seva2011) and explaining 66% of the variance. A solution that accounts for over 60% of the variance is often considered satisfactory (Hair et al., Reference Hair, Black, Babin and Anderson2014). A promin rotation was used (Lorenzo-Seva, Reference Lorenzo-Seva1999), which allows for factor simplicity to be maximised (Lorenzo-Seva, Reference Lorenzo-Seva2013) and an oblique method is recommended when expecting a level of correlation between factors. In this study, factor simplicity statistics (S=.998; LS=.679) were in the 100th percentile (Lorenzo-Seva, Reference Lorenzo-Seva2003), suggesting that the three-factor model was reasonable for these data. The goodness of fit index, and adjusted goodness of fit index, were both above .9, also providing evidence that the model was acceptable (GFI=.991; AGFI=.988). The root mean square of residuals (RMSR=.042) was below Kelley’s criterion, again suggesting that the three-factor model fitted the data adequately.

Internal consistency was measured using Cronbach’s alpha. All three factors contained seven items each, and reported good internal consistency (Factor 1, α=.88; Factor 2, α=.90; Factor 3, α=.85). The correlations between the three factors ranged between .29 and .48.

Interpretation of factors

Following the reduction of the measure to 21 items, the content of the items included in each factor suggested themes of items create emotional attachment and safety, items represent parts of me and my life, and items are useful and should not be wasted (Table 3).

Factor 1: items create emotional attachment and safety

This factor accounted for 39% of the variance. The items in this factor related to the emotional safety people felt from their items. In some of the items, this was in relation to how they felt about their objects compared with other people, and one item was about the safety of the items themselves. This has been demonstrated in the previous literature around object attachments and anthropomorphism (Yap and Grisham, Reference Yap and Grisham2019) and emotional comfort (Murdock, Reference Murdock2006). These beliefs are represented in the CBT model of HD as beliefs about vulnerability, safety, comfort and control.

Factor 2: items represent parts of me and my life

This factor accounted for 16% of the variance. The items in this factor related to how someone’s items represent important memories, relationships, and aspects of their identity that would be lost if discarded (Frost et al., Reference Frost, Tolin and Maltby2010; Kellett et al., Reference Kellett, Greenhalgh, Beail and Ridgway2010; Steketee et al., Reference Steketee, Frost and Kyrios2003). Treatments that target beliefs about identity have been shown to be effective for people with HD (O’Connor et al., Reference O’Connor, Bodryzlova, Audet, Koszegi, Bergeron and Guitard2018). Beliefs about identity are included in the CBT model of HD as beliefs about memory and lost information, but this factor extends to beliefs about what aspects of someone’s identity their items represent and how this is connected to emotions, meaning and sentimentality.

Factor 3: items are useful and should not be wasted

This factor accounted for 12% of the variance. The items in this factor related to the value, use and opportunity of their items. This theme has been demonstrated in the previous literature as particularly important for people with HD (Frost and Gross, Reference Frost and Gross1993; Frost et al., Reference Frost, Steketee, Tolin, Sinopoli and Ruby2015), and is represented in the CBT model of HD as beliefs about utility and beliefs about responsibility.

Discussion

This paper presents a novel measure, named Beliefs about Items in Hoarding Disorder (BIHD), which was designed to identify the presence and strength of beliefs in hoarding disorder to aid the routine assessment and formulation of HD. A copy of the measure for use in clinical practice is freely available in the Supplementary material. Factor analysis was used to identify subtypes of beliefs and refine the BIHD for clinical use, which indicated three factors. The CBT model of HD suggests five themes of beliefs/attachments. These are beliefs about possessions, vulnerability, responsibility, memory and control. However, Frost and Hartl (Reference Frost and Hartl1996) did not report that their categories were created using factor analysis. Identity was shown to be a key theme of beliefs in this sample of people experiencing HD, which is not explicitly mentioned in the CBT model, but in this analysis combined the items relating to the potential loss of stories, memories and relationships. There were some themes of beliefs that have been highlighted by previous research (Tinlin et al., Reference Tinlin, Hillman, Gregory and Lomax2019) that did not load onto the three factors identified, and there were some that were combined in the results of this study in a way that has differed from previous themes. For example, in the CBT model, waste and lost opportunity have been grouped together under the theme of responsibility; however, they are represented differently in the three factors in this study. Items representing beliefs about beauty (e.g. item 10: I keep items because I can see their beauty) were included in the 40 items initially factor analysed, and loaded onto the waste factor, but were removed due to lower loading for the final measure.

Comparing the literature on beliefs and cognitions in HD and OCD highlights striking differences between the two conditions, further demonstrating support for the differential diagnosis. This study (and many others: Gordon et al., Reference Gordon, Salkovskis and Oldfield2013; Tinlin et al., Reference Tinlin, Hillman, Gregory and Lomax2019; Tinlin et al., Reference Tinlin, Beckwith, Gregory and Lomax2022) have shown the beliefs that people experiencing HD hold about their objects and these differ from metacognitive beliefs present in OCD about the need to control or neutralise thoughts (Tümkaya et al., Reference Tümkaya, Karadağ, Yenigün, Özdel and Kashyap2018). Although there can be an overlap in the language used to describe beliefs in both conditions, they represent different concepts. For example, thoughts relating to responsibility are present for both conditions. In HD these beliefs are focused on the individual’s responsibility for the items (Frost and Hartl, Reference Frost and Hartl1996), whereas in OCD, these beliefs are focused on the individual’s responsibility for themselves or others (Salkovskis et al., Reference Salkovskis, Wroe, Gledhill, Morrison, Forrester, Richards, Reynolds and Thorpe2000). People with hoarding disorder have been shown to have fewer intrusive thoughts about their items, as well as fewer urges to complete rituals (Williams and Viscusi, Reference Williams and Viscusi2016). Herein lies key distinctions between two conditions that can result in similar behaviours yet require different approaches to treatment. The need for a clinician to understand the distinction between the two is one of the many reasons that measures like the one presented in this paper are needed.

This study combined beliefs about items from previous measures and research (Gordon et al., Reference Gordon, Salkovskis and Oldfield2013; Steketee et al., Reference Steketee, Frost and Kyrios2003; Tinlin et al., Reference Tinlin, Beckwith, Gregory and Lomax2022) and presented these to people with HD, with the aim of co-developing a measure uniquely designed for use in HD assessment. Inclusion of 38 items in this initial measure development study allowed participants with HD to rate the strength of their belief in each statement and factor analysis of the data suggested a relationship between the beliefs that imply three themes of beliefs about items in HD. The statements that best exemplify these three themes have been retained in the version of the BIHD presented by this article (available in the Supplementary material) as a potential measure of beliefs in HD. Factor 2 (Items represent parts of me and my life) includes statements relating to identity, which was initially identified by Tinlin et al. (Reference Tinlin, Beckwith, Gregory and Lomax2022) as important for people with hoarding disorder, yet missing from previous measures, such as the SCI and BAH.

Strengths and limitations

Regarding lived experience of HD, the statements in this study were taken from existing research, including qualitative research with people experiencing HD (Tinlin et al., Reference Tinlin, Beckwith, Gregory and Lomax2022) and a working group including those with lived experience was consulted in phase 1. However, this was in the form of a written questionnaire and feedback was only sought at one timepoint. Changes made following the feedback questionnaire were not discussed further with the working group and demographic data were not collected on the working group, and so it is not possible to assess any potential bias from the working group in questionnaire development.

Although the sample size was adequate, additional reliability and validity data are needed to support the BIHD and the factor structure proposed in this study. Steps were taken to increase the diversity of the sample, but it was also an opportunistic sample based on self-report measures. Recruitment for this study was advertised internationally, but was limited to the English language. Contrary to previous studies (such as Gordon et al., Reference Gordon, Salkovskis and Oldfield2013) participants were not excluded from the sample if experiencing co-morbid mental health problems. Symptoms of anxiety, depression and OCD were measured to understand the levels of co-morbidity in the sample, showing that at least 48% of participants scored above the threshold for at least one co-morbid condition. However, other conditions, such as psychosis or bipolar were not screened for. There are arguments for the need of a ‘pure HD’ sample, but evidence is that co-morbidity in mental health is the norm, not the exception (Newman et al., Reference Newman, Moffitt, Caspi and Silva1998). Developing a measure in a population with co-morbidity could make the final questionnaire less specific, but with co-morbidity so common in practice, including these participants could also increase applicability. Completion of the measure by further participants would strengthen or revise the conclusions from this initial development. For example, whilst participants in this study met the clinical threshold on the HRS-SR, the sample did not complete a diagnostic clinical interview. Current data do not allow for thresholds for each of the themes as ‘subscales’, nor are there associated behaviours or treatments. Completing the measure with a patient in practice may indicate that certain types of beliefs are more strongly held for that individual, but they may also hold beliefs about their items that span all three categories. For example, due the separation of OCD and HD diagnostically within previous studies, and from clinical experience, the team decided to remove the belief category of harm avoidance in order to differentiate clearly from OCD beliefs, but acknowledge that this could have been confirmed through inclusion or further investigation. Further study of the final measure presented in this paper is needed to develop our understanding of people’s beliefs about their items and how measuring them in this way is useful.

Another consideration for generalisability is that research samples in HD research have been shown to not match community samples (Woody et al., Reference Woody, Lenkic, Bratiotis, Kysow, Luu, Edsell-Vetter, Frost, Lauster, Steketee and Tolin2020). For example, men are less likely to volunteer for research participation and are under-represented compared wtih characteristics of people presenting to services (22–26% in research; 40–54% in services). Average age also differs (50–53 in research; 57–71 in services). These imbalances were also present in the sample of this study. It would be beneficial to target these populations in a confirmatory factor analysis study, and to try to address this in samples for future reliability and validity analysis. However, initial research into how under-represented groups can be recruited into research has shown that this is challenging and would require innovative approaches (Martin et al., Reference Martin, Zakrzewski, Chou, Uhm, Gause, Chan, Eckfield, Salazar, Vigil and Bain2018).

Future research

Although Frost and Hartl’s (Reference Frost and Hartl1996) CBT model of hoarding provides a framework for the understanding of HD, is has not been updated since the diagnosis was added to the DSM-5. Frost and Hartl (Reference Frost and Hartl1996) stated, ‘It is meant to provide a framework for the development, refinement and testing of hypotheses relevant to the study of compulsive hoarding. It is not meant to be an exhaustive listing of relevant variables’ (p. 349). This model differs from the cyclical maintenance models used in CBT treatment for other mental health problems and it is not clear where intervening would be most beneficial. It demonstrates how beliefs about acquiring, saving and clutter can maintain these processes. However, as research into the beliefs reported by people with HD has progressed since the development on the model, there are some gaps. As research into HD develops, it may be that an updated CBT understanding of HD is required.

To continue the development of the BIHD measure, future studies would aim to confirm the factor structure presented here in another sample, preferably in a sample that better matches those in services and addresses the inequality in this sample (e.g. gender and ethnicity). Analysis of test–retest reliability and inter-rater reliability would assist in improving confidence in the reliability of the measure. Further research into the use of this measure in clinical practice from the perspective of staff and service users would strengthen the evidence base. It is important that this measure is acceptable for people with HD and that they think it would be helpful and useful in treatment. It would also be beneficial to test construct and concurrent validity. Reliability and validity research is already planned to compare those with and without co-morbid OCD, as the research team seek to strengthen confidence in this measure.

Clinical implications

It is also hoped that the BIHD measure will support a better understanding of HD from both a clinical and community perspective. Providing a measure that encourages conversations with service users about their beliefs and how these may be maintaining the problems will hopefully improve openness, reduce stigma and increase understanding for everyone touched by HD. Normalising the beliefs that are common in HD for service users and professionals may promote engagement in some cases, allowing for earlier intervention and reduced costs (Ragan, Reference Ragan2022). People experiencing difficulties with hoarding may see the measure and recognise that they agree with the beliefs included, prompting them to seek help. Health professionals and services may use the measure with patients in initial appointments to identify if they identify strongly with common beliefs in HD and may return to the patient’s answers when formulating how the patient’s beliefs are influencing their emotions and behaviours. The measure could be used at multiple times during therapy, to provide feedback on goals to change a thinking pattern or belief that the patient has identified as problematic. It may provide structure and confidence for professionals so that they are aware of what beliefs they may hear when working with someone with HD.

Conclusion

This paper presents the BIHD measure, which aims to identify the strength and content of a person’s beliefs about their objects and behaviour. This paper suggests three key themes of beliefs, based on the responses of an online sample of people who self-identified as having hoarding disorder, and reached the minimum criteria on the HRS. This measure could support the ongoing research into HD as the evidence base continues to grow for this now independent diagnosis. Further work is needed to support the reliability and validity of this measure in clinical practice but presents an updated and novel tool to assist in developing a more comprehensive understanding of HD, how it affects those that experience it, and how we can best support those that are struggling.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1352465825101227

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgements

Advice on statistical issues, especially the use of Factor, was provided by Professor Mark Freeston (Newcastle University) and Dr Urbano Lorenzo Seva (Rovira i Virgili University).

Author contributions

Kathryn Ragan: Conceptualization (equal), Data curation (lead), Formal analysis (lead), Funding acquisition (equal), Investigation (lead), Methodology (lead), Project administration (lead), Resources (lead), Validation (equal), Visualization (lead), Writing - original draft (lead), Writing - review & editing (lead); Rowan Tinlin-Dixon: Conceptualization (equal), Funding acquisition (equal), Methodology (supporting), Resources (equal), Supervision (equal), Validation (equal), Writing - review & editing (supporting); Claire Lomax: Conceptualization (equal), Funding acquisition (equal), Methodology (supporting), Resources (equal), Supervision (equal), Validation (equal), Writing - review & editing (supporting).

Financial support

The study was funded by a Doctorate in Clinical Psychology (Newcastle University).

Competing interests

The authors declare none.

Ethical standards

The authors have abided by the Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct as set out by the BABCP and BPS. Ethical approval was provided by the University of Newcastle (ref: 4326/2020). Informed consent to participate and for the results to be published has been obtained from participants, who were informed of their right to withdraw.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.