Introduction

In January 2019, the memorable image of heavily pregnant Tulip Siddiq MP being wheeled through the voting lobby of the UK Parliament, delaying childbirth to vote in a critical Brexit division, highlighted a long‐standing issue: parliaments are not adequately family‐friendly workplaces. Siddiq's experience reflects similar incidents in multiple parliaments, for instance, in Japan, Germany and Denmark women MPs have been asked to leave when, for varying reasons related to a lack of childcare, they have brought young babies into their parliamentary chambers (Inter‐Parliamentary Union, 2023). In the United Kingdom, shortly after Siddiq's case, a policy was implemented to avoid a similar situation in the future: the new ‘baby leave’ pilot system. The system, later made permanent in September 2020, allows for new parent members of parliament (MPs) to nominate a proxy to vote on their behalf, eliminating the need for them to be physically present to vote. By 2022, additional provisions allowed MPs to claim expenses for extra staffing costs if they take leave as a new parent. These are welcome changes, family‐friendly working practices are vital to the retention and recruitment of diverse representatives. Yet, instituting such reforms raises questions about public reactions, something little tested in current work. Whilst normal for most workers to take leave, MPs are judged as representatives and may face a sceptical public. Do citizens punish MPs for taking time off their elected duties for a baby? Using a pre‐registered conjoint experiment, this note asks what public perceptions of MPs taking parental leave are. Is there a penalty for taking leave, and importantly, who pays the price?

Two clear contributions are made in this note. Firstly, while to date, work on the role of family‐friendly reforms in the diversification of political institutions has primarily focused on institutions and elites (Childs, Reference Childs2004; Krook, Reference Krook2010; Allen et al., Reference Allen, Cutts and Winn2016), this study brings in the ‘demand side’ – how the public perceives the use of family‐friendly measures. The democratic costs of unrepresentative institutions have long been made clear (Childs & Celis, Reference Childs and Celis2020; Phillips, Reference Phillips1995). Both academics and campaigners argue that institutional practices, such as childcare and parental leave provisions, can determine the diversity of elected representatives and (limited) action has been taken by institutions to initiate family‐friendly working practices. Bringing in the demand side contributes to understanding of electoral biases towards underrepresented groups in politics. Negative biases towards women in politics are increasingly contended, with recent studies revealing an overall positive bias for women in electoral choice experiments (Schwarz & Coppock, Reference Schwarz and Coppock2022) as well as how gender biases still operate through mediating factors such as partisanship, behaviour, candidate qualifications and candidates’ intersecting identities (Bauer, Reference Bauer2020; Martin & Blinder, Reference Martin and Blinder2021; van Oosten et al., Reference Oosten, Mügge and Pas2024). Parenthood, which directly relates to gendered norms of caring, is an established mechanism through which gender bias has traditionally manifested in voter behaviour. In this study, experimental data enable the identification of electoral costs associated with parental leave while in office and, most importantly, reveal who bears the consequences.

Against expectations, the results show there is little punishment for MPs who take parental leave. Overall, voters prefer MPs who are parents compared to those without children, in line with previous evidence (Campbell & Cowley, Reference Campbell and Cowley2018). And within MPs with children, there is no punishment for taking leave. MPs still receive a parenthood benefit even when the ‘costs’ of parenthood, that is taking leave, are explicitly considered. MPs with children who take up to 6 months of parental leave are still preferred over MPs without children by approximately 5 percentage points. Importantly, these findings are contingent upon MP's sex. Women MPs who take parental leave are the preferred choice over their male counterparts, by up to 8 percentage points when taking 1 year of leave. Therefore, when the ‘costs’ of parenthood are emphasised, that is, having children could mean a representative is absent by taking periods of parental leave, women MPs receive a parenthood benefit, while men MPs do not. MPs’ use of parental leave, however, does not lead to differential evaluations of an MP's job performance, strength, assertiveness or compassion. The preference for women MPs who balance motherhood and public office does not appear to be rooted in perceived competency advantages.

This research advances the understanding of gender biases in politics. The preference for women MPs taking parental leave aligns with a broader positive bias for women candidates now present in electoral choice experiments. This challenges traditional ideas that women must conform to masculine norms when in office for voter approval. Additionally, it supports calls for family‐friendly policies in politics promoting a more inclusive democratic system, as it assuages concerns that MPs who use such practices will face significant electoral backlash.

Politics, parliaments and parenthood

Established scholarship shows legislatures are institutionally sexist in their formal and informal workings, including the difficulties of combining caring responsibilities with elected office (Childs, Reference Childs2016; Kenny, Reference Kenny2013). Globally, there continues to be a lack of adequate childcare and parental leave for members of elected institutions (Inter‐Parliamentary Union, 2023; Joshi & Goehrung, Reference Joshi and Goehrung2021). These work as a barrier to both the recruitment and retention of diverse representatives. A US survey of likely political candidates found that having responsibility for a majority of the household income negatively affects women's political ambitions, especially for mothers (Bernhard et al., Reference Bernhard, Shames and Teele2021). Critical actors, both academic and non‐academic, create and campaign for ‘diversity‐sensitive’ or ‘gender‐sensitive’ frameworks for legislative reform (Childs & Challender, Reference Childs and Challender2019) including more family‐friendly practices (e.g., IPU Action Plan for Gender Sensitive Parliaments, 2017) Yet, there is a lack of understanding of public opinion of these measures. Bringing in the electorate view of politicians taking parental leave directly addresses questions of parliamentary diversity and electoral discrimination and illuminates emergent ideas of the ‘good parliamentarian’ (Challender & Deane, Reference Challender, Deane, Evans, Salmion Percival, Silk and White2021), by making explicit the balance between required physical presence in Parliament and MPs’ family lives. The difficulty and likely inequities in family and public life balance for members, and institutional support of this, was highlighted in the recent, wider international debate about presence during the Coronavirus pandemic which saw many parliaments shift from physical to virtual proceedings (J. C. Smith, Reference Smith2022b; J. C. Smith & Childs, Reference Smith and Childs2021).

Previous UK experimental evidence finds that, regardless of MP sex, voters prefer a parent MP (Campbell & Cowley, Reference Campbell and Cowley2018). However, given voter scepticism and distrust of MPs, it is expected that MPs taking explicit leave from their role are disliked by voters and this negative effect will increase the longer the length of leave. Leave can be seen as a ‘cost’ to voters here as it is not specified in the vignette that the representational duties of the MP were covered, and there is no formal system of locum or reserved MPs in the United Kingdom. Any effect of leave is expected to be gendered, however. A growing debate surrounds the extent and prevalence of direct bias against women seeking political office. A recent meta‐analysis of 67 studies on gender and candidate choice using experimental data, revealed that women actually enjoy a slight advantage in voter choice compared to men, becoming slightly more positive in studies after 2014 (Schwarz & Coppock, Reference Schwarz and Coppock2022). However, it is evident that biases can manifest in complex ways and may depend on factors such as partisanship, behaviour, candidate qualifications and candidates’ intersecting identities (Bauer, Reference Bauer2020; King & Matland, Reference King and Matland2003; Martin & Blinder, Reference Martin and Blinder2021).

Parental leave directly relates to gendered norms associated with caregiving, an established mechanism through which gender bias influences voter behaviour (Bell & Kaufmann, Reference Bell and Kaufmann2015). Traditional accounts of gender‐based stereotyping depict motherhood as a disadvantage for women in politics. Motherhood is perceived as incongruent with public life and reinforces the association of women with feminised traits, such as compassion, weakness and diminished assertiveness. These traits are considered incongruent with the preferred (masculine) traits typically associated with politics and politicians (Bauer, Reference Bauer2015; Huddy & Terkildsen, Reference Huddy and Terkildsen1993; Stalsburg, Reference Stalsburg2010). Experimental evidence finds that women candidates with young children are viewed as less viable, with less time capacity, than their male counterparts, (Stalsburg, Reference Stalsburg2010). Women in public life have also faced scrutiny regarding their ability to fulfil their public duties while managing their domestic responsibilities, as exemplified by the case of Sarah Palin in the United States (Carlin & Winfrey, Reference Carlin and Winfrey2009). If these traditional accounts hold, it is expected that women MPs who take parental leave will be punished by voters and will be more associated with traditional feminine traits of being more caring, less assertive and weaker.

At the same time, father MPs taking parental leave also break gendered norms and may be emasculated. Previous work in other workplaces finds that men taking parental leave face a higher penalty than women (Gloor et al., Reference Gloor, Li and Puhl2018; Wayne & Cordeiro, Reference Wayne and Cordeiro2003). In the context of politics, taking parental leave may break two norms for men – both gendered and workplace norms, under this thesis then it is expected that any negative effect of taking parental leave will be larger for men MPs than women MPs.

The competing politicalised parenthood thesis offers alternative expectations that taking parental leave will have a positive effect on vote evaluations of both men and women MPs. Recent research challenges the prevalence of hostility to women as their political presence becomes normalised and gendered norms evolve. In this context, motherhood is ‘politicised’ and even serves as an electoral advantage for women (Deason et al., Reference Deason, Greenlee and Langner2015; Teele et al., Reference Teele, Kalla and Rosenbluth2018), including within the UK context (Campbell & Cowley, Reference Campbell and Cowley2018). For instance, when Jacinda Ardern took maternity leave as the second global leader ever to give birth whilst in office international coverage portrayed her positively (Galy‐Badenas & Sommier, Reference Galy‐Badenas and Sommier2021; Żukiewicz & Piel Martín, Reference Żukiewicz, Piel Martín, Barczyszyn‐Madziarz and Żukiewicz2022). The ‘politicised motherhood thesis’ contends mother politicians can present themselves as having an additional level of competence, making them ‘special, different and powerful’ (Deason et al., Reference Deason, Greenlee and Langner2015, p. 136). Therefore, it is expected that women MPs who take parental leave will be rated as more caring, assertive and stronger. Media coverage in Canada, Australia and the United States has framed women politicians’ juggling of motherhood and work as evidence of their competency, relatability and effectiveness in their political roles (Auer et al., Reference Auer, Trimble, Curtin, Wagner and Woodman2020; Deason et al., Reference Deason, Greenlee and Langner2015). In Germany, recent work finds that women mayors are not penalised (nor rewarded, however) for mentioning family and private life (Denner et al., Reference Denner, Schäfer and Schemer2022). Politicised motherhood warrants caution, however. As Teele et al. (Reference Teele, Kalla and Rosenbluth2018) assert, a preference for the married with children candidate creates a double bind for women: those with demanding family roles have less time and resources to campaign compared to their male counterparts and women with less traditional family structures.

With an increasing personalisation of politics, we may expect a politicisation of not only motherhood but parenthood in general, encompassing fatherhood (J. C. Smith, Reference Smith2018). As gender norms for men and masculinity evolve, even within the realm of political masculinities, men politicians often present as ‘modern men’ who highlight their familial roles to emphasise their human or communal nature. In the British context, leaders like Tony Blair and David Cameron utilised their fatherhood in public imagery as part of their modernisation agenda (A. Smith, Reference Smith2016; J. C. Smith Reference Smith2022a). Campbell and Cowley (Reference Campbell and Cowley2018) found that men and women MPs in the United Kingdom equally prioritise their parenthood on their websites. In Germany, experimental evidence suggests men mayors can benefit from portraying a ‘modern’ family life compared to a traditional one (Denner et al., Reference Denner, Schäfer and Schemer2022). Appeals to fatherhood, whether in traditional or modern ways, can frame men politicians as ‘good guys’, showcasing their sound character and likability (Auer et al., Reference Auer, Trimble, Curtin, Wagner and Woodman2020).

However, actively embracing fatherhood, like taking parental leave, may challenge traditional gendered conceptions of masculinity. Some experimental studies find a fatherhood penalty disadvantaging men with young children compared to men without children (Stalsburg, Reference Stalsburg2010). Alongside, or perhaps in response to, modern man imagery there is a recent rise of hypermasculinity in political leadership, characterised by ‘purposeful and aggressive displays of masculinity with exaggerated displays of traditionally stereotyped masculine characteristics’ (J. C. Smith, Reference Smith2022a, p. 451). Additionally, while fathers may choose to leverage their parenthood, they have more leeway in deciding whether or not to politicise it, unlike women who may find their parenthood subject to discussion regardless of their public disclosure (J. C. Smith, Reference Smith2018; Trimble, Reference Trimble2017). It is expected that men MPs who take parental leave will be rated as more caring, less assertive and weaker as a more feminised notion of masculinity may be associated with more compassion but lower levels of assertiveness and strength away from traditional masculine stereotypes.

The UK case

The empirical case for this paper is the United Kingdom. As noted, recent parliamentary reforms in the national parliament introduced limited parental leave provisions: new parent MPs can nominate a proxy to vote on their behalf, eliminating the need for them to be physically present to vote and MPs can claim expenses for extra staffing costs if they take leave as a new parent. A lack of formalised, extensive parental leave and childcare for MPs is not unique to the United Kingdom; however, as across democracies family‐friendly practices in Parliaments have been found to be inadequate (Inter‐Parliamentary Union, 2023). Empirical evidence from a range of countries informs the theoretical frameworks above, and so expectations are not specific to the UK case. However, it may be that in countries with more equitable parental leave for ‘normal’ workplaces, for example, Scandinavian countries, a negative electoral impact of MP parental leave would not be expected, and differential responses to men and women MPs may be less likely as men taking parental leave is more normalised and experiences of leave by voters themselves can promote gender‐egalitarian attitudes (Tavits et al., Reference Tavits, Schleiter, Homola and Ward2024).

Methodology

I use a ‘forced‐choice’ conjoint experiment to test the causal impact of an MP taking parental leave on citizen evaluations in the United Kingdom. In this experiment, respondents are presented with two hypothetical MPs. Fictitious politicians are commonly employed in experimental studies (Huddy & Terkildsen, Reference Huddy and Terkildsen1993; Campbell & Cowley, Reference Campbell and Cowley2014). The experimental design was fielded by YouGov on their UK online panelFootnote 1 in November 2021. The design, hypotheses and analysis plan were pre‐registered. The sample was 1852 people who are nationally representative of the British public on a range of attitudinal and demographic criteria. The demographics of the sample can be found in the online Appendix.

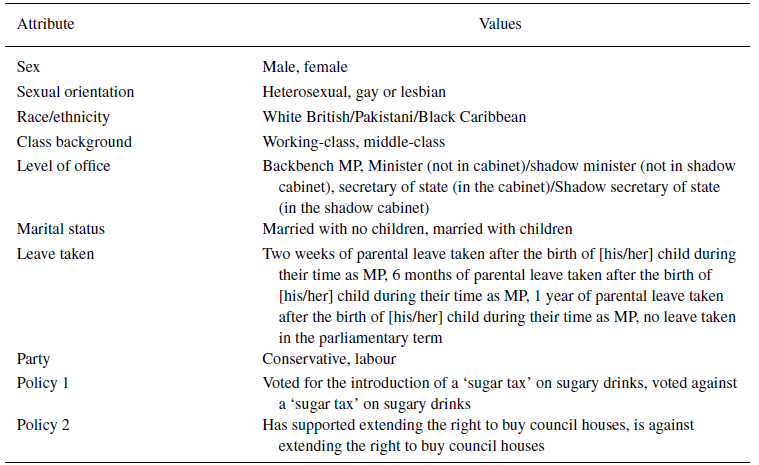

In the design, the sex, race, class, sexuality, parenthood, taking parental leave, length of leave, party, level of office and policy positions are randomised. Whether an MP had children or not was perfectly randomised. Within the MPs with children, the length of leave was perfectly randomised between no leave, 2 weeks, 6 months or 1 year of leave. All MPs were described as married as single parenthood effects were not tested, and this also more naturally varied sexuality as their married partner could be same sex. Some randomisation restrictions were applied: (i) an MP cannot take parental leave if he or she has no children (in this case, leave information is omitted); (ii) same‐sex couples appear in 10 per cent of profiles for realism (De La Cuesta et al., Reference De La Cuesta, Egami and Imai2022). All other values are completely randomised. Table 1 lists all attributes and levels; positions on political issues are included to mask the interest in parental leave and demographics. Other demographics were varied to test further pre‐registered hypotheses (see the online Appendix). The sex of the MP and their ethnicity were varied by the use of different names, as is common in studies of gender and ethnicity in candidate experiments (Martin & Blinder, Reference Martin and Blinder2021). A full list of names can be found in the PAP. Ethnicity was also varied in the profile with information provided about background. The profiles were presented as two vignettes with information in full, bullet‐pointed sentences. Respondents viewed two profiles of MPs simultaneously. They repeated the task twice. Example profiles are in the online Appendix.

Table 1. Table of attributes

Dependent variables

There are three dependent variables. (i) Forced choice: respondents make a forced choice between the two profiles, by answering ‘overall which MP do you feel most positive about’. The question is not framed as a direct electoral decision, as in the British political system it is not plausible to cast a vote between incumbent MPs. (ii) Traits: Respondents rate MPs on three traits based on similar measures of gendered stereotypes: strength and assertiveness (masculine) and caring (feminine) (Bauer, Reference Bauer2015; Huddy & Terkildsen, Reference Huddy and Terkildsen1993; Schneider & Bos, Reference Schneider and Bos2019). These are measured on semantic differential scales of 0–7 from weak to strong, not assertive to assertive and distant to caring. (iii) Job approval: a measure of general job approval asks ‘On a scale ranging from 0 to 7, where 0 means strongly disapprove and 7 means strongly approve, how much do you disapprove or approve of the way each MP is handling their job?’

Analysis

Unconditional effects

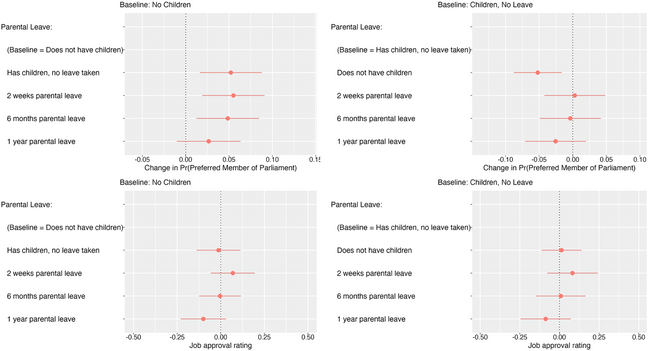

Parenthood and leave length are combined into one attribute in the analysis. Previous findings show the public prefers MPs with children (Campbell & Cowley, Reference Campbell and Cowley2018); therefore, the effect of parental leave could be driven by an MP having children compared to not or by the act of them taking leave. Therefore, two possible baseline categories are used: (i) an MP does not have children (left‐hand panel Figure 1); (ii) an MP has children and takes no parental leave (right‐hand panel Figure 1). Average marginal component effects (AMCEs) for each attribute compared to the baseline of that attribute are presented for the forced choice and job approval (Figure 1) with the two baseline categories.Footnote 2 Marginal mean plots and full AMCE models are given in the online Appendix.

Figure 1. AMCE for forced choice and job approval.

Against expectations, Figure 1 shows that, compared to not having children, having children has a significant and positive effect on the likelihood of respondents choosing the MP as their preferred MP, even if the MP took parental leave. Once the length of leave reaches 1 year the positive effect is smaller and non‐significant, although notably remains positive. However, having children and taking up to 6 months of parental leave increases the preferability of an MP by around 5 percentage points compared to not having children. When compared to an MP who has children and does not take leave, there is no significant difference in preferability of MPs who take parental leave. Again, there is a parenthood benefit here – there is a significant and negative effect of not having children compared to having children and not taking parental leave. An MP taking a full year of leave does have some negative effects compared to taking no leave although this is non‐significant. Taking periods of parental leave does not impact job approval (Figure 1 bottom panel), with non‐significant and small effects for MPs with children who took leave or not.

Overall voters express a general preference for the parent MP even when they take parental leave. This positive effect does not seem to come from thinking parents are doing a better job.

Conditional effects

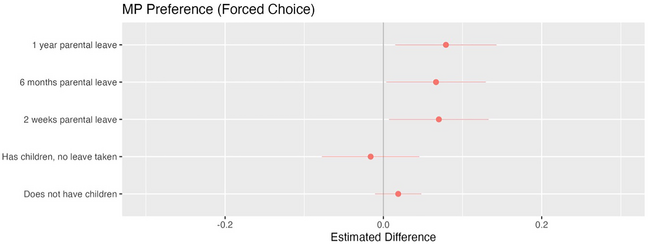

Competing theories offer differing expectations on how gender will mediate the effect of parental leave. Figure 2 shows the marginal mean differences in the forced choice dependent on MP sex. The plot shows the differences in the mean for women MPs minus the mean for men MPs. For forced choice, this can be interpreted as positive estimates which mean women score higher. For example, if the preference on a given attribute for women MPs is 55 and for men it is 47, the difference in marginal means is (55 − 47 =) 8, meaning women are preferred on that attribute relative to men by 8 percentage points. For instance: relative to men, women who take 1 year of parental leave are preferred by approximately 8 percentage points.

Figure 2. Difference in marginal means by MP sex: Forced choice.

In line with the politicised motherhood thesis, which theorises that women politicians benefit from motherhood, the differences in marginal means show that for MP choice, there is a significant and positive effect of women having children and taking parental leave compared to men. Women MPs with children who take parental leave are consistently the preferred MPs compared to men by up to 8 percentage points for 1 year of leave taken. There are no significant differences between men and women MPs not having children or having children and taking no leave. However, when we make the ‘costs’ of parenthood clear (i.e., that having children could mean a representative is absent by taking periods of parental leave) women receive a parenthood benefit but men do not. However, these effects do not hold for job approval where there are no significant differences between men and women MPs (see the online Appendix).

These differences are not driven by gendered trait stereotypes of men and women taking parental leave. Figure 3 shows the marginal means for the trait variables for men and women MPs. There are no significant differences within or between MPs by sex, meaning that men or women MPs were not rated differently on caring, assertiveness or strength when they took parental leave, both compared to the opposing sex and compared to their own sex not taking leave after having a child or not having children. There is no support for either the traditional stereotyping or the politicised parenthood hypotheses in relation to trait evaluations.

Figure 3. Marginal means by sex of MP on trait outcomes.

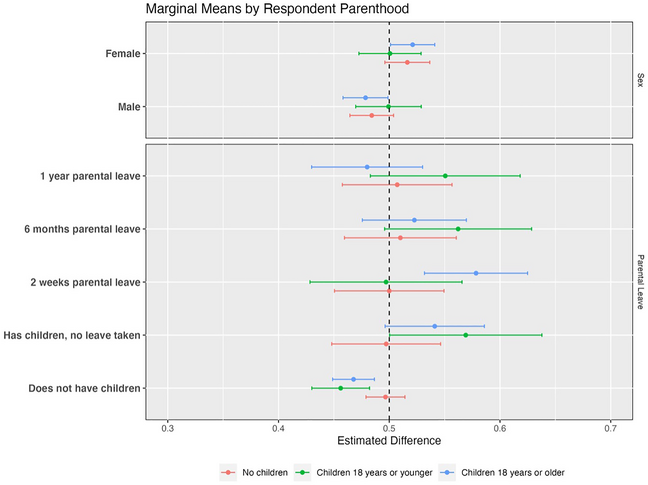

Respondent demographics

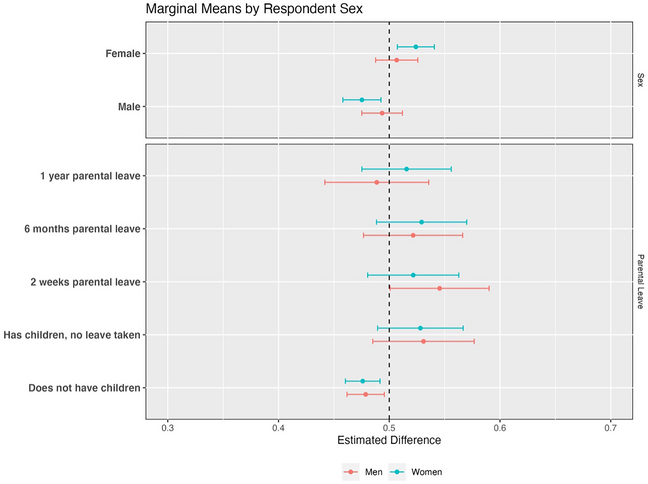

Heterogenous effects by respondent demographics are tested using subgroup marginal means, considered the best method to test for group differences (Leeper et al., Reference Leeper, Hobolt and Tilley2020). The marginal means for the forced choice variable by different respondent subgroups are shown in Figures 4 and 5. For the sex of respondents, there are no significant differences, men and women responded in similar ways to the MP profiles. In terms of having children, respondents with children under 18 although non‐significant are more likely to choose the MPs who have taken longer lengths of parental leave (6 months or 1 year) compared to respondents with no children or children over 18.

Figure 4. Subgroup marginal means for forced choice by respondent sex.

Figure 5. Subgroup marginal means for forced choice by respondent parenthood.

Discussion and conclusion

Family‐friendly working practices are needed to increase the retention and recruitment of diverse elected representatives in legislatures. Yet instituting such reforms raises questions about public reactions, something little tested in current work. Does the public punish MPs for taking time off their elected roles for a baby? And, importantly, who pays the price? The results from pre‐registered conjoint experiments demonstrate that there exists little punishment for MPs who take parental leave. In line with previous research (Campbell & Cowley, Reference Campbell and Cowley2018), the results show a preference for the parent MP. Notably, this ‘parenthood benefit’ endures even when the potential ‘costs’ of parenthood, taking parental leave, are explicitly stated. MPs who take up to 6 months of parental leave experience an increase in preferability by approximately 5 percentage points compared to those without children. However, the effect does reduce for MPs who take a longer leave of 1 year, rendering the benefit non‐significant.

Crucially, these findings reveal that voter preferences are contingent upon the sex of the MP. Women MPs who take parental leave consistently emerge as the preferred choice over their male counterparts, with up to 8 percentage points when 1 year of leave is taken. Strikingly, when the ‘costs’ of parenthood are emphasised, women MPs receive a parenthood benefit, while men MPs do not. Nevertheless, the study also highlights that voter preferences do not translate into differential evaluations of job performance, strength, assertiveness or compassion based on the MPs’ parenthood or use of parental leave. Hence, the preference for women MPs who balance motherhood and public office does not appear to be rooted in perceived competency advantages.

This research contributes on two significant fronts. Firstly, it furthers understanding of gender biases in politics, exploring these biases once politicians are in elected office. The preference for women MPs who take parental leave aligns with the notion of politicised motherhood, as women politicians benefit from embracing motherhood (Deason et al., Reference Deason, Greenlee and Langner2015). Yet this is not driven by voters perceiving mothers as more competent or from the trait stereotypes examined as the thesis suggests. A more generalised preference for women, and in this case the ‘most feminine’ woman – the mother who takes parental leave – aligns with new evidence of a positive bias for women candidates in electoral choice experiments (Schwarz & Coppock, Reference Schwarz and Coppock2022). These findings continue to challenge the traditional thesis that women must act in masculine ways to gain voter approval. Yet, politicised motherhood is not entirely advantageous for women in politics. Women with the gender‐congruent family lives (i.e., married with children) have fewer resources and less time to campaign for office (Teele et al., Reference Teele, Kalla and Rosenbluth2018). This presents a further puzzle when compared to men MPs. Whilst men MPs did not face an explicit cost when they took parental leave in the experiments, both men and women generally benefit from parenthood. However, once an MP is described as taking leave, women receive a parenthood benefit, but men do not. This opens the possibility that men politicians are punished for gender‐incongruent behaviour. Potentially, traditional gender norms exist behind these biases driving a positive preference for women's gender‐conforming behaviour of parental leave and a more negative response to men's gender‐incongruent behaviour. Understanding more on the role of gender (in)congruent behaviour, such as in terms of politicians’ family lives, in driving the recent positive preference for women can advance our understanding of gender dynamics and inequities in our political landscape.

Secondly, it lends support to academic and practitioner calls for family‐friendly practices to diversify representative bodies. Moving beyond a focus solely on the institutional and elite levels (Allen et al., Reference Allen, Cutts and Winn2016; Childs & Celis, Reference Childs and Celis2020) to consider public perceptions, it is found that MPs are unlikely to pay an electoral cost for the use of family‐friendly practices. For practitioners and policymakers, the most compelling takeaway is the lack of significant opposition or punishment from the public towards MPs who take parental leave. This finding should encourage further support and implementation of family‐friendly policies and practices in politics, fostering a more inclusive and representative democratic system.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank various colleagues who have been kind enough to read and comment on this paper and the experimental design including Daniel Devine, Sarah Childs, Lotte Hargrave and Stuart Turnbull‐Dugarte. Thank you also to participants at seminars at the Universities of Bath and Manchester for insightful comments and feedback. This study was funded by the British Academy (SRG2021∖210828)

Conflict of interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Funding information

British Academy (SRG2021∖210828)

Ethics statement

This study was approved by the University of Southampton Ethics Committee ERGO number 64121

Data availability statement

All data to enable replication is available upon request from the corresponding author.

Online Appendix

Additional supporting information may be found in the Online Appendix section at the end of the article:

Supporting information

Online Appendix