Introduction

“Zaiton. . .the port for all the ships that arrive from India laden with costly wares and precious stones. . .It is also the port for all the merchants of all the surrounding territory. And I can assure you that for one spice ship that goes to Alexandria to pick up pepper for export to Christendom, Zaiton is visited by a hundred.”Footnote 1

– Excerpt from Marco Polo, “Description on Zaiton (Quanzhou),” in his Description of the World (1292)

Although Marco Polo's trip to China may be subject to dispute,Footnote 2 he produced what has arguably become one of the most significant accounts of global travel in world history. After all, he brought Chinese civilisation to the attention of the West, and his lively rendering of Quanzhou harbour (Zaiton) became an influential depiction of a Chinese port city for Europeans.Footnote 3 His travelogue succeeded in introducing Europe to an important port city in China at that time, but excluded important coastal areas outside of Southeast China. By “Southeast China”, I refer to the coastal region located south of Shanghai. In fact, since the Song dynasty (960-1279), port cities in southeast China became famous as significant links in trans-regional sea trade between China and the wider world.Footnote 4 Taking Shanghai as the midpoint between north and south, we are likely to be far more familiar with port cities to its south than those to its north. From the time when Marco Polo published his account to the time when the five treaty ports were opened to the British, the southeast seacoast was regarded as the gateway to China from the Far West (taixi). As a consequence, in discussions of coastal cities in early modern China, academic attention has long focused on port cities such as Shanghai, Amoy, Fuzhou, and Canton, where European, Islam, and Middle-east traders and travellers had direct cultural and economic interaction and experience. I consider this phenomenon (i.e. the focus on the coast of late imperial China) a “Southeast China centrism.” We have been ceaselessly swayed by this centrism from the 1950s and, since then, have intensively studied the coast of southeast China, to the exclusion of the northeast.Footnote 5 There are many exciting topics related to the southeastern coast which, no doubt, deserve our attention; however this makes the northeastern coast seem far removed from sea trade and coastal management in the history of Asian port cities.Footnote 6 For instance, in the fantastic volume edited by Frank Broeze entitled Gateways of Asia: Port Cities of Asia in the 13th-20th Centuries, ports along the Northeast China coast, surprisingly were nowhere to be found in the entire volume.Footnote 7 Although we might all concede that some southeastern seaports were vital to transoceanic interactions, to ignore northern port cities in connection with China and the maritime world in the early modern period is shortsighted. This article aims at breaking through the “Southeast China-centric” framework by focusing attention on a less familiar coastal seaport, Dengzhou. By detailing and examining the political and economic importance of this port city throughout the eighteenth century, I argue that the sea surrounding northeastern China was no less important than that in southeastern China. Even if port cities in the north might not have been as economically vibrant as those in the south, we should not overlook their functions and histories. This paper will show that northeastern cities like Dengzhou also attained unique patterns of development within the political and economic spectrums throughout the long eighteenth century.

I have chosen the long eighteenth century as the timeframe because it has long been misconstrued as a time when China had very little to do with the ocean. Other than the annexation of Taiwan in the 1680s and perhaps the sea blockade policy, maritime militarisation and shipping management were rather inconspicuous features of the Qing Dynasty (1644-1912) before the arrival of western gunboats in the mid-nineteenth century. Fortunately, this perception is gradually being challenged by a number of prominent scholars in the field of maritime history as the Qing initiated a set of regulations dedicated to maritime trade.Footnote 8 However, the impact of their research is, as yet, insufficient. In line with this promising research, I hope that the present work can serve as an example to show that the Qing was not simply a land-based empire in the eighteenth century, but a sea power concerned with its maritime frontier as well as the development of a number of important coastal cities in the north and south.

The Five Zones

Perhaps it was the publication of John King Fairbank's influential book, Trade and Diplomacy on the China Coast: The Opening of the Treaty Ports, 1842–1854 in 1953, that fuelled the rise in scholarship on the urban developments and trading patterns of a number of coastal cities in China, especially among historians in the West. The cities that caught attention were primarily the five treaty ports that were forced open as a concession following China's defeat in the First Opium War (1839-1942). In these five ports (Canton, Amoy, Fuzhou, Ningbo, and Shanghai), free trade was enforced between foreigners and Chinese merchants. The infamous treaty port system, symbolising the unique diplomatic relationship between China and the West, is the origin of the opening of these port cities. The five port cities experienced dramatic growth in economic development under the treaty port system.Footnote 9 Canton, for example, quickly transformed into the economic center in both the Euro-Asian and Asian-Pacific markets; it was even considered the “wonder of the Far East”,Footnote 10 where international interactions actually took place in pre-modern times.Footnote 11 The other four treaty ports also went through remarkable development featuring transcultural interaction. Because of this distinctive feature, historians have tended to study the urban development of these coastal cities. Scholars like Linda Cooke Johnson, Rhoads Murphey, and Robert Nield, to name a few, have written beautiful histories of these places.Footnote 12 Their research has not only shed light on the histories of the cities themselves but has enlightened numerous subsequent studies of these sea ports. As many scholars have argued, the coast of Southeast China assuredly had a dynamism that helps us better understand the history of late imperial China as well as early modern global history.Footnote 13

The coast of Southeast China is no doubt worth studying; but, as I have argued, this is a more or less Southeast China-centric way to conceptualise China's coast. This framework may be useful in opening the window to various kinds of economic and cultural exchanges between different peoples, but it keeps us from getting a comprehensive picture of the East Asian maritime world, because significant bodies of water attached to China, such as the Bohai and the Yellow Seas, somehow elude discussion. I think it is about time to shift our attention from south to north in order to generate a better picture of China's coast during the eighteenth century.

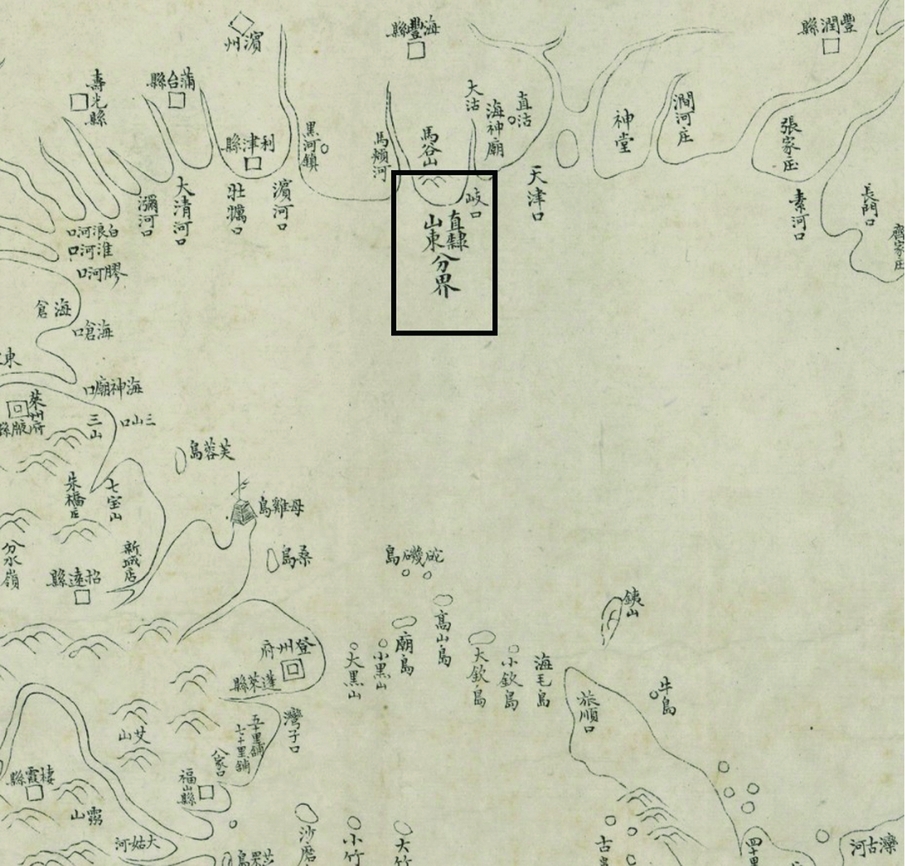

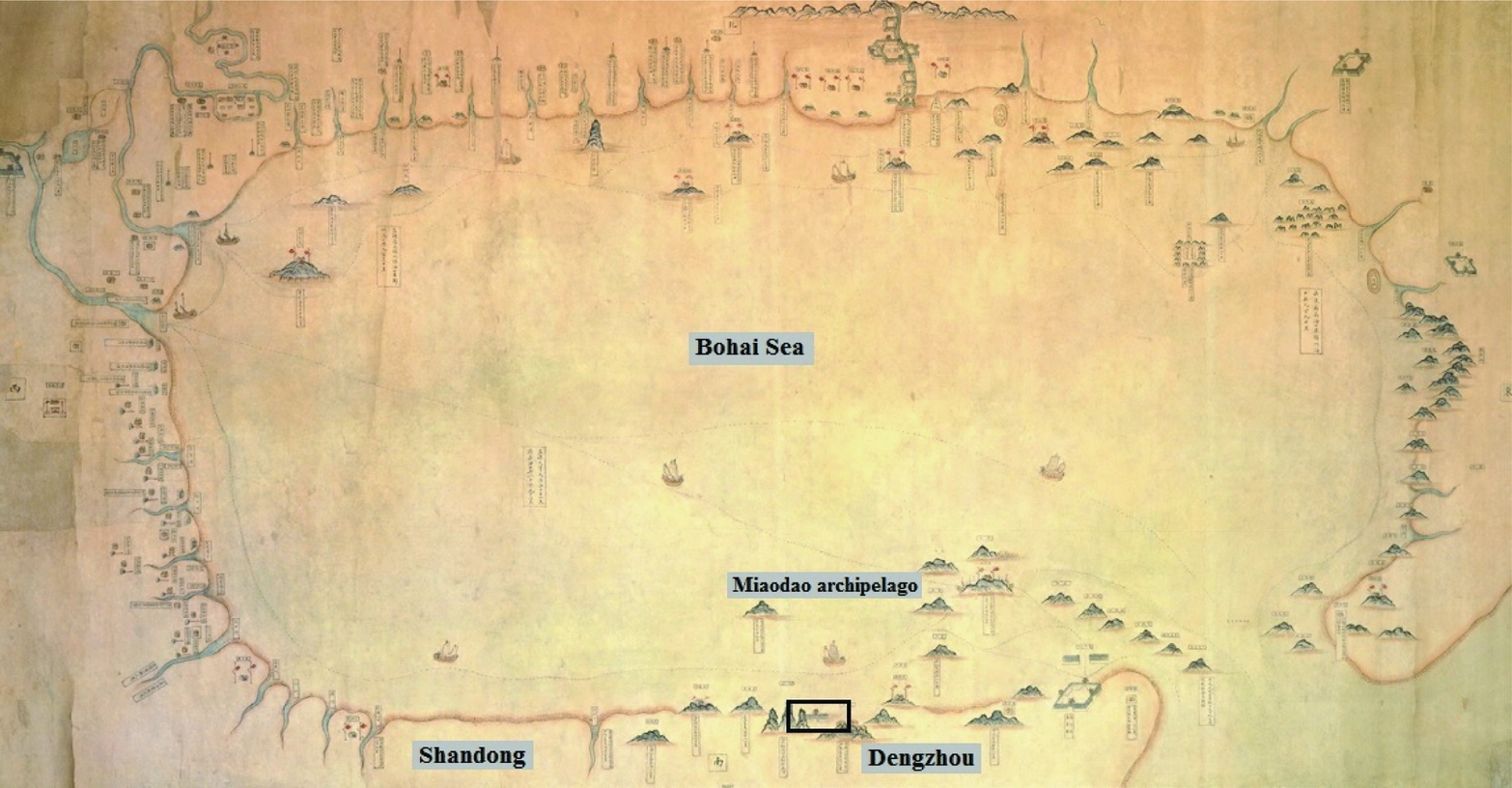

By early 1977, the American historical anthropologist William G. Skinner (1925-2008) had already divided China into nine macro-regions according to the drainage basins of the major rivers and other geomorphological features that constrained travel.Footnote 14 Five of these nine regions were linked to the ocean, while two macro-regions, Manchuria and North China, were linked to the northeastern coast (see Figure 1). That Skinner's model is compelling is demonstrated by its success in having broadly stimulated area studies over the past few decades. But I do not apply his model in this paper, simply because it is very land-based. Instead, I propose dividing the seas along the coast of China into five discrete, yet interlinked, maritime zones: (1) The Bohai zone, (2) the Jiangsu sea zone, (3) the Zhejiang sea zone, (4) the Taiwan Strait, and (5) the Guangdong sea zone. This five-zone model derives from a coastal map (haitu) entitled Qisheng yanhai tu (The Coastal Map of Seven Coastal Provinces) officially produced in the late eighteenth century and reprinted subsequently in the nineteenth century. The nineteenth century edition of this coastal map introduces “dividing lines (fenjie)” between specific maritime spaces (see Figure 2). These dividing lines indicate that specific maritime spaces were policed and governed by their respective coastal provinces. Breaking down the maritime frontier of the Qing Empire into the same divisions that were used at that time is perhaps the best way to study the maritime policies, consciousness, and ideologies in question. Understanding the development of coastal China in the late imperial period may also help us escape the Euro-centric framework.

Figure 1. The Skinner Model

Figure 2. Example of “dividing lines (fenjie)” (Map: Qisheng yanhai tu; 19th century edition)

Using the five-zone model, the Bohai zone is of particular concern not only in helping us shift our academic focus “from south to north”, but because the Qing court valued it in a deliberate manner throughout the eighteenth century. As the only maritime space connecting three coastal provinces with very different customs and cultures, the Bohai Sea was the maritime gateway leading to the capital region (jingji) and the homeland of the Manchu ruling elite. It was also the maritime space that connected the Chinese capital to Korea, the nearest neighboring state. Transcultural interactions between Chinese, Korean, and Japanese merchants, intellectuals, and even pirates across the Bohai zone were no less dynamic and vibrant than those in the southeastern maritime region. The Bohai zone was also notable for its extensive maritime resources. As Jiang Chenying notes in his Haifang zonglun (A comprehensive study on maritime defense), the Bohai Sea was famous for sea-salt production and a variety of fishery products from the Ming onwards.Footnote 15 In his Dushi fangyu jiyao (Essence of historical geography), Gu Zuyu also noted the bountiful sea-salt and seafood production across the Bohai Sea, explaining how it contributed significantly to the prosperous coastal economy along northeast China.Footnote 16 In fact, beginning in the eighteenth century, significant maritime resources (e.g. sea salt) as well as some trading goods produced in northeast China (e.g. soybean paste) were shipped to other parts of China from the Bohai region.Footnote 17 The Bohai zone was therefore considered to be both a strategic corridor to the open sea and a natural buffer for the region surrounding the Qing capital.

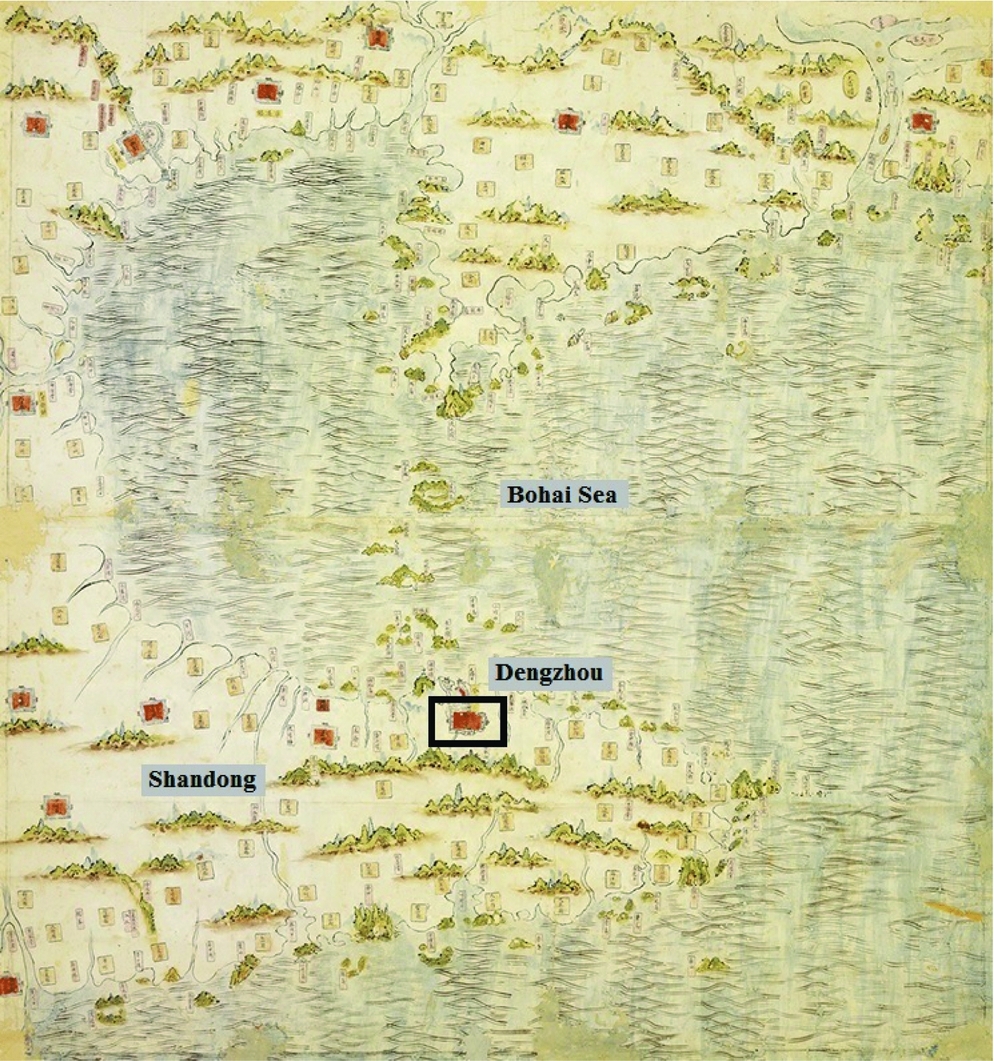

The two best known port cities in the Bohai zone are arguably Tianjin and Port Arthur – probably because, once again, they were forcefully opened by western imperialistic powers for free trade in the late nineteenth century. Instead of these two port cities, I choose to study Dengzhou, a relatively small and less familiar seaport located in the northern part of Shandong. Despite its size, this port city remained politically and economically important for some time in the eighteenth century. In the pre-modern era, Dengzhou experienced ups and downs in its development, like other coastal cities (not just in China, but all over the world). Once an economically active harbour thronged with traders from all over northeast Asia, it was a fortified naval base established by the Qing court in the early eighteenth century. But it was overshadowed by other coastal cities in later years. Then, in the late nineteenth century, it gained importance once again for a variety of reasons. In order to better comprehend these political and economic changes, we will travel back to late imperial Dengzhou in the sections that follow. In the first section we will briefly introduce the city's geographical location and its history prior to the Qing dynasty. Then we will examine the maritime militarisation of Dengzhou and the Bohai area. In the final section, we will inquire into the city's maritime commerce and its economic significance within the Northeast Asian network Figure 3.

Figure 3. Deng Jin Shan Ning sizhen haitu (Ming edition; National Palace Museum)

The City

To southern Chinese and especially to foreigners, Dengzhou may be less familiar than Suzhou, Fuzhou, or Guangzhou, the famed centres of Jiangnan and Guangdong cultures, which feature on so many tourist routes. But to people in northeastern China and especially the natives in Shandong, Dengzhou carries rich historical associations. The Northern Song historian Ye Shi described Dengzhou as a strategic harbour connecting the world beyond the Song Empire. As he noted, “the city is surrounded on three sides by the sea. During the reign [of northern Song], the assorted maritime states that presented tribute to the Emperor in Beijing all came through Denglai”.Footnote 18 The Qing literati Gu Zuyu also valued Dengzhou as the place that “controls the safety across the Bohai Gulf as well as the Yellow Sea region”.Footnote 19

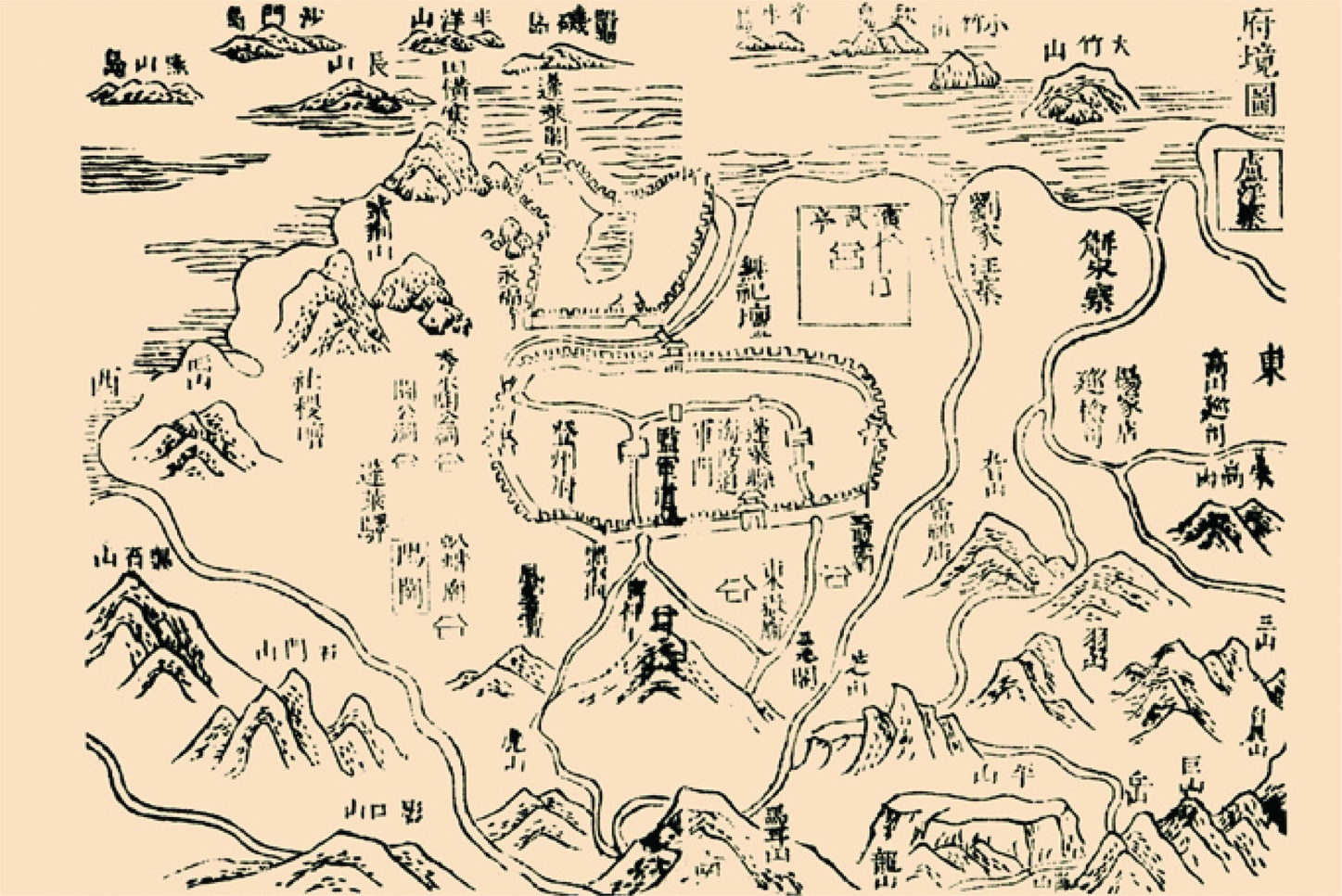

Known as Penglai today, Dengzhou is a coastal city situated in the northern Shandong Peninsula. Its description in the gazetteer Dengzhou fuzhi, as well as evidence in modern atlases, gives us a reasonably good sense of the general topography of the area. The city lies more than a hundred miles from the nearest coastal city, Yantai, and almost five hundred miles from Weihaiwei. Off the northern coast of Dengzhou lies the Miaodao archipelago, or the Long island, which comprises 32 small islands famous for their stunning scenery. In the eighteenth century, it was said to take less than a day to reach the Liaodong Peninsula from Dengzhou through the Miaodao archipelago Figures 4 and 5. Dengzhou was also located close to Korean terrain. As recorded in the Official History of the Sui Dynasty, Dengzhou was the point of departure for the Emperor Yang of the Sui's naval attack on Korea. The land to the south and southwest of Dengzhou is flat; but farming is difficult. The nearest inland commercial centre is Laizhou, a traditional city that benefited considerably from its abundant natural resources, such as gold, magnetite, and granite. In the Ming and Qing, Laizhou was closely linked to Dengzhou and Fushan in the east and Qingzhou in the west, within the Shandong transport and postal system. Troops and cavalries could effectively be mobilised from the west (Qingzhou) to the east (Dengzhou and other coastal cities). Although Dengzhou, as such, was only a harbour with limited natural resources and relatively small population (diji minpin),Footnote 20 it had good east-west land and water communications, because it was closely connected to other big urban cities.

Figure 4. Bohai yanan daoli tu (ca. 18th century edition; National Palace Museum)

Figure 5. Dengzhou fujing tu (Shunzhi edition)

Some archeologists have argued that the Shandong peninsula was first settled in the remote past;Footnote 21 but the picture of Dengzhou in ancient times is still fragmentary and far less clear than one would wish. We are certain that, from the Tang period onwards, geo-political factors became critical determinants of the historical development of this small coastal city.Footnote 22 Located at the tip of the northern Shandong peninsula, the port was ideally situated for trade with the ports of Liaodong in the north, such as Lushun and Jinzhou. Embraced by the Bohai Gulf and naturally protected by the Miaodao archipelago, it became a desirable naval base from which to extend military control over the Bohai region. Enjoying these geopolitical advantages, Dengzhou served as one of the designated sea ports of entry for foreign tribute and trade missions in the Sui and Tang dynasties. Throughout the Tang era, it was a point of access for foreign dignitaries and traders (mostly Japanese and Korean) to enter the Chinese empire.Footnote 23 This continued to be the case into Song times. As recorded in the Korean archive, the Annals of the Joseon Dynasty, several officials from the Korean state of Silla were allowed to hold military and administrative posts in Dengzhou in order to protect their traders and citizens.Footnote 24 This record suggests that Dengzhou served as a significant station that connected China and Korea politically and economically. Later in the 1020s, however, Dengzhou gradually lost its significance in foreign sea trade. The Northern Song government banned foreign vessels from landing in Dengzhou out of fear that the Korean merchants would support the expansive Liao state in the north by shipping weapons and other supplies through the city.Footnote 25 Since the enforcement of a trade ban required a strong military commitment, Dengzhou was quickly transformed from a trading port to a military settlement guarded by roughly three to four thousands soldiers.Footnote 26

During the Yuan dynasty, Dengzhou regained its importance in foreign sea trade. Its geographical location remained a magnet for overseas traders interested in the North China market. Apart from fostering foreign sea trade between China, Korea, and Japan, Dengzhou served as a port for the transportation of grain boats from South China. Its location on the north-south coastal route made it the equivalent of Zhejiang and Suzhou for North China in the thirteenth century. Although the exact quantity of goods imported from the south, mainly from the Jiangnan area, is uncertain, a Yuan dynasty poet described the bustling harbour near Dengzhou as “flooded by porcelain and pots from Jiangsu and cloth from Zhejiang”.Footnote 27 For more than two centuries Dengzhou, on the one hand, maintained itself as the principle sea port where travellers and traders gathered to ship and unload their cargoes, on the other, it served as the northern terminus of the grain boats network along the coast of China. Nevertheless, Dengzhou was not simply a trading post in the Yuan dynasty. It was at the same time a military harbour supporting the Mongol invasions of the Japanese islands in 1274 and 1281 during Kublai Khan's rule. As a result, Dengzhou gained a considerable military population. More men were stationed in the city to construct and refine war junks on a regular basis. The navy based in Dengzhou was also responsible for eradicating pirates, both Chinese and Japanese, who threatened the Bohai area.Footnote 28

With the initiation of a sea ban on private coastal trade in the early Ming, the development of Dengzhou took a new turn. It significantly weakened the place of Dengzhou in the merchant networks of northeast Asia. However, restrictions on sea trade were not as effective as expected,Footnote 29 so the Ming court restricted local engagement in merchant transport by establishing more coastal garrisons along the coast. Dengzhou's military apparatus was hence strengthened qualitatively and quantitatively, as recorded in the Account of Naval Exercise in Penglai (Penglai ge yue shuicao ji) written by Xu Ji,Footnote 30 Even though Dengzhou was not as prominent in maritime commerce in the early Ming as it had been before, it became a well-fortified military harbour in northern Shandong.Footnote 31 The city was not the only seaport that experienced military enlargement, however. Almost the entire coastline of Shandong, including Yantai, Weihai, and Qingdao, similarly underwent coastal militarisation, with the aim of undermining pirates, smugglers, and unlicensed traders.Footnote 32 Dengzhou only re-emerged as a key port in the regional sea trade network of greater Bohai when this sea ban was abolished in 1567 and through the late Ming and early Qing dynasties most imports from Korea were shipped to China via Dengzhou. Dengzhou's growth is illustrated by the dramatic increase in the number of Korean merchants resident there between the early sixteenth and the mid-seventeenth centuries.Footnote 33 Yet because the Ming court aimed to govern the coastal region in a precautionary manner, Dengzhou retained its military importance. As a result, the size of the garrisons in Shandong and Dengzhou grew substantially between the mid- and late- Ming. For example, in 1592, immediately following the first invasion of the Korean peninsula by the Japanese warlord Toyotomi Hideyoshi (1536-1598), the Wanli Emperor (r. 1572–1620) deployed 6,700 soldiers to the Jinan and Dengzhou garrisons. Dengzhou at that time had the duty to safeguard the maritime frontier from subsequent Japanese invasions and to provide necessary military support to other cities within the Bohai region (Bohai quyu).Footnote 34 Until the seventeenth and the eighteenth century, Dengzhou continued to maintain its position as a military harbour. As the Korean emissary Yi Min-song recorded in 1623 when he reached the Temple Island (Miaodao), just off the coast of Dengzhou, “I see fire signal stations established on each island peak, within sight of one another. Agricultural officers for the fields of the military settlements (tuntian nongmu) are everywhere. The war junks and merchant ships anchored along the coast are uncountable”.Footnote 35 Yi's account succinctly indicates a strong naval presence in Dengzhou. The city was evidently regarded as a strategic outpost within the context of Ming military coastal policies.

The above discussion, though admittedly brief, is sufficient to show that Dengzhou, despite its smaller size and population, was an important and strategic coastal city which inevitably played a major role in the maritime history of Northeast China. Dengzhou's continuous militarily and economic development from the Tang to the Ming, due to a set of geo-political factors, is also clear. Now it is essential to discuss in more detail the means and extent to which Dengzhou was maintained as a significant military harbour and coastal city within the high Qing maritime governing policies during the eighteenth century.

Maritime Militarisation

The political instability of the late Ming was apparent throughout the Shandong peninsula, and was accompanied by social and economic crises. In the 1620s, the peninsula was ravaged by drought, famine, and misfortune, which gave rise to a host of internal rebellions affecting Dengzhou. According to an official stationed in Dengzhou in the 1630s,

the city of Deng[zhou] abuts the seacoast where bandit evildoers always make their lairs. The land of the city is rocky, and no crops flourish or grow well. For these reasons, many people are poor. Since they are poor they are easily motivated to commit crime in order to fulfill their basic needs. The use of military force to ensure order is critical.Footnote 36

In 1631, the Ming commander Kong Youde (?-1652), leading his troops in mutiny, seized the city of Dengzhou and proceeded to establish an independent military regime on the Shandong peninsula. Although Kong's authority survived for only one year, the rebellion and the subsequent Ming government's campaign to suppress it severely devastated Dengzhou. As Chen Zhongshang, a newly appointed magistrate, described, “when I first looked out over all of Dengzhou I saw only bleak wasteland, overgrowth, collapsed walls, and broken roof tiles. I felt despair. . . . . .the sights and sounds of the animals, crops, tourists, and entertainers, once seen and heard throughout the area, will probably never be known again”.Footnote 37

As the famine in Shandong continued in the last few years of the Ming, starving refugees were dying on the roads around Dengzhou. Men and women committed suicide and the city slowly disintegrated.Footnote 38 In February 1636, eight years before Beijing fell to the Qing, the Manchus annexed the decaying Dengzhou. Yet Dengzhou did not revive as a flourishing sea port after the takeover. Seventeen years later, Dengzhou became the centre of a disturbance. In 1661, a peasant rebellion against the Qing led by Yu Qi, a native of Shandong, broke out in Shandong near Dengzhou. The rebellion escalated out of control along the Shandong littoral. Yu Qi and his followers captured Dengzhou and turned the city into a stronghold for their anti-Manchus campaign. The anti-Qing character of this added a new sense of political urgency to the threat of domestic crisis. This compelled the Qing court to develop new strategies to suppress rebellion as quickly as possible, and it took less than a year for the Qing to bring Dengzhou back into its fold.Footnote 39 After Dengzhou was recaptured in 1675, the pragmatic Emperor Kangxi began increasing the maritime militarisation of Dengzhou in order to strengthen the military capability of the Bohai region. The emperor ordered that additional soldiers be added to the Dengzhou naval base, which was first established by the Shunzhi Emperor in 1644. The structure of the navy was also reorganised. Consisting of almost 1200 soldiers and 20 war junks and patrol boats, it was divided into two specific teams: the “front team (qianying),” and the “back team (houying)”. The former was responsible for policing the sea space between Dengzhou and Ninghaizhou in the east, while the latter was ordered to police the sea space between Dengzhou and Laizhou in the west. In order to further expand the zone of policing, the qianying was relocated to Jiaozhou in 1706 and renamed the Jiaozhou navy (Jiaozhou shuishi), whereas the houying continued to be stationed in Dengzhou. At that time, the sea in southern Shandong was patrolled by the Jiaozhou navy, while the sea surrounding northern Shandong, including a significant part of the Bohai Sea, remained under the control of the Dengzhou navy (the Dengzhou shuishi), which was considered large and solid.Footnote 40 As an anonymous writer in the early Qing noted, compared to its structure in the Ming, the navy was effective in attacking seafaring targets (mainly pirates) across the waiyang sector, thereby preventing intruding vessels from entering the harbour.Footnote 41 However, there was no consensus in the navy as to where intruders should be confronted. Some officials argued that the best way to deal with pirates was to stop them well away from the harbour, while others believed that pirates could be more effectively dealt with after they moved closer to the harbour because the waiyang sea was deep, vast and uncharted which made successful engagement with pirates difficult. They could easily turn away and elude authorities once they had sighted naval vessels.Footnote 42 It was not until the Yongzheng period (1722-35) that clear instructions were given on the best strategies for the navy to follow. As Huang Yuanxiang, the general of Dengzhou, has suggested, war junks only attacked pirates after they were spotted entering the harbour area.Footnote 43 One of the logics of Qing defensive, known as the “land-sea protection strategy (hailu lianfang)”, promoted cooperation between imperial navy vessels and paotai (barbettes) to destroy pirates.

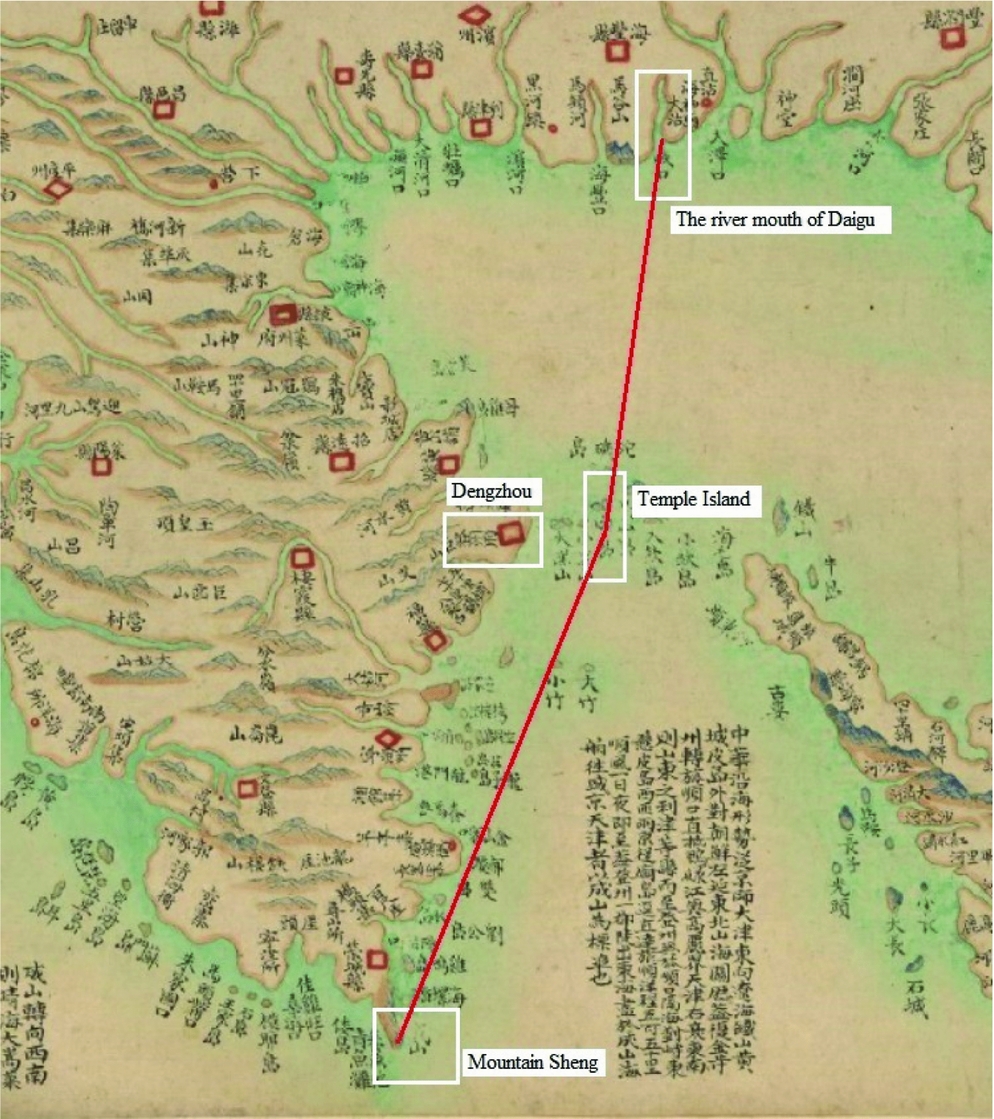

Maritime militarisation of Dengzhou underwent two waves of reform in 1714 and 1734. In 1714, the Kangxi emperor believed that “there was not much trouble on the sea” and the Bohai Gulf already could be effectively guarded by two other navies stationed in Fengtian and Tianjin. He then ordered the merging of the Dengzhou and Jiaozhou navies into one, called the Jiaozhou shuishi. The naval base in Dengzhou was thereafter moved to Jiaozhou, and the Jiaozhou shuishi became the only naval force to police the sea across northern and southern Shandong (nanbei fangqu). This relocation of the naval base to Jiaozhou diminished the military significance of Dengzhou. Altogether, for twenty years Jiaozhou functioned as the base to monitor all war junks operating in Shandong seas.Footnote 44 This situation did not change until the Yongzheng emperor decided to re-elevate the maritime military structure in the Bohai region as well as the strategic importance of Dengzhou. Due to the gradual expansion of sea trade across the Bohai Gulf, the Yongzheng emperor implemented stronger military control to oversee domestic and overseas economic interactions there, especially interactions between the Shandong and Liaodong peninsulas.Footnote 45 In fact, since Ming times, Shandong and Liaodong had long been considered two closely connected provinces. Tao Langxian, a governor of Shandong in the seventeenth century, once warned the imperial court that “Deng (Shandong) and Liao should not be governed separately”.Footnote 46 Situated at the northern tip of the Shandong province near the Liaodong peninsula, Dengzhou's location made it the preferred site to strengthen the ties between these two counties. As a consequence, in 1734 Yongzheng divided the Shandong navy into three divisions, with two divisions based in eastern Jiaozhou and the third based on “Mount Sheng (Shengshan)” at the eastern extremity of the Shandong peninsula. To ensure that the three divisions would fulfill their duties properly and collaboratively, the Yongzheng Emperor designated Dengzhou as the naval base to monitor and operate the three naval stations. This made the city a place where officials dealt with a wide range of logistical and administrative needs, such as personnel, revenues and expenses, shipbuilding administration, warehouses for weaponry, defense against intruders, training exercises, patrolling and seizing, military administration, and construction of barbettes, beacon-mounds, fortresses, as well as the levy system for law and order in ports and harbours. From then until the late eighteenth century, Dengzhou remained the centre of naval activity in Shandong.Footnote 47

Dengzhou's strategic location continued to be highly valued in the mid-Yongzheng period. The Qing court established garrisons (wei) and military stations (suo) to guard the land and marine palisades. The wei-suo system along the coast was a pre-Manchu development that had existed in the Ming coastal defense system. The suo were subdivisions of the wei; and the wei and suo formed units of either battalions (qian hu suo) or companies (bai hu suo) that were actively involved in coastal defense.Footnote 48 Under the wei-suo system, farmlands were provided to soldiers to promote self-sufficiency. Barbettes and beacon-mounds were constructed to protect the littoral as well as to send warning signals along the coast. In 1726, the first set of barbettes along the coast of the Shandong Peninsula was built by Emperor Yongzheng's officials in Dengzhou in “Guangdong style”.Footnote 49 From 1726 to 1732, twenty coastal barbettes were constructed in what is today Longkou Harbour, Taozi Bay, Shuangdao Harbour, Chaoyang Harbour, Rongcheng Bay, Yangyuchi Bay, Shidao Bay, Jinghai Bay, Tadao Island, and Sushan Island.Footnote 50 Until the middle of the eighteenth century, the Beijing government continued to provide financial support to these barbettes, which worked collaboratively with the Shandong navy to protect the Bohai region. All of this demonstrates the strategic importance of Shandong and Dengzhou in defending against pirates, domestic rebels, and other potential intruders from the sea.

Large-scale sea patrols (huaixiao), or “military tours”, were launched annually in northern Shandong, most of which were monitored and operated by officials in Dengzhou. To get a complete picture of how the Qing court actualised its maritime militarisation across the Bohai Sea, the boundaries of the Shandong navy patrols under the supervision of the Dengzhou authority deserves analysis. The Dengzhou fuzhi recorded that the navy patrolled 1,770 li of sea.Footnote 51 The navy, which consisted of roughly 410 soldiers and 7 war junks, first departed from the Dengzhou naval base located in a harbour called “the bridge-mouth (Tianqiao kou). The navy then turned east and sailed all the way to the Mountain Sheng (Shengshan), the eastern limit of the maritime patrol. It then moved back to Dengzhou, passing the Temple Island, and continued to head west until reaching the mouth of the Daigu River (see Figure 6). During peacetime, large-scale sea patrols operated seven months a year, from March to September. This large-scale patrol cost the Qing court more than 10,000 liang annually, according to records. Figures 1, 2 and 3 depict the patrol limit of the Dengzhou navy and large body of water of the Bohai Gulf it covered. The seas off of Shangdong and Liaodong were divided by a vertical line cutting across Temple Island. Although the vertical line drawn in Figure 1 is not an actual dividing line drawn by the Qing government, according to the textual records in the Dengzhou gazetteer, we can assume that the islets located north of the Temple Island, namely the Gaoshan Island, Daqin Island, and Xiaoqin Island, were considered to be very far from Dengzhou. All of them were considered to be in the outer sea “waihai”. Based on Dengzhou's naval capability, this island group was beyond its defense perimeter.

Figure 6. Patrol Limit of the Dengzhou Navy (Map: Qisheng yanhaitu; the 1880s edition)

Table 1. The eight different types of seawater (Shandong tongzhi [Yongzheng edition])

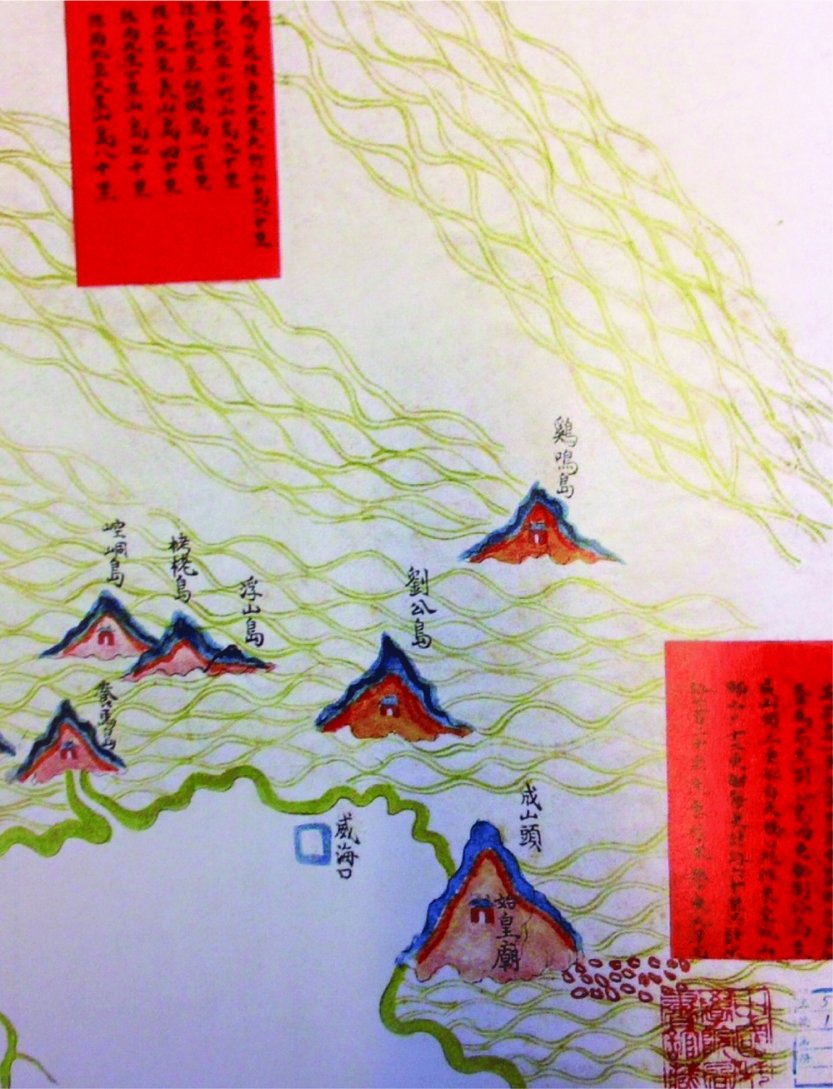

A coastal map entitled Shandong Dengzhou zhenbiao shuishi qianying beixun haikou daoyu tu (hereafter daoyu tu; see Figure 7) also provides us with valuable information about the large-scale sea patrol operated by the Dengzhou navy. According to the description provided by the Chinese Academy of Science, where the daoyu tu is now preserved, this coastal map was compiled under official supervision sometime between 1734 and 1842.Footnote 52 It depicts the coastal situation of Dengzhou and portrays a series of significant islands off the Shandong coast. The marginalia on the coastal map indicate the time required for the Dengzhou navy to reach those islands. It also shows the patrol limit of the navy. For instance, it mentions that “from Dengzhou to the western part of Bohai the navy must pass by several islands. It is a 720 li journey. The Daigu estuary marked the limit of the navy's partrol and acted as a dividing line between Shandong's water and Tianjin's water Once the navy reached the river mouth of Daigu, there would be the patrol limit and the dividing line between Shandong and Tianjin sea spaces”.

Figure 7. Shandong Dengzhou zhenbiao shuishi qianying beixun haikou daoyu tu

The practice of sending vessels from Dengzhou to patrol the Bohai Gulf continued during the early Qianlong era. In collaboration with the land forces, Dengzhou authorities were able to assemble war junks in Shandong in order to police and protect the Bohai region. The navy was also effective in attacking their targets within their patrol limit, thus preventing any intruding vessels from entering the northern coast of Shandong Table 1. By the late eighteenth century, patrol posts and forts equipped with weapons (from cannons to bows and arrows) dotted the coast. Most of the commanders in Dengzhou (Dengzhou zongbing) such as Shi Wenbing (?-1694), Huang Yuanji, and Dou Bin (1715-1802) were experienced and energetic in maintaining a competent navy.Footnote 53 Therefore, there is little doubt but that the Dengzhou navy gradually became more sophisticated through development between the Kangxi and mid-Qianlong eras.

Dengzhou continued to serve as the military base monitoring the navies as well as assuming patrolling duties in Shandong. During the mid-Qianlong period (1742-1783), however, Dengzhou naval structure contracted, due to a long period of peace and the prolonged absence of pirates and domestic rebels from the sea. From 1742 to 1783, the Qianlong Emperor reduced the number of soldiers and war junks supervised by the Dengzhou office and failed to provide sufficient repairs and refinements for the remaining vessels.Footnote 54 As a consequence, personnel experienced low morale and were often afraid of going to sea. Troops were not properly trained and some warships were not suitably equipped. These problems were not rectified until the Daoguang period. As Tuohunbu, the governor-general of Dengzhou, and Yu Ming, the commander of Dengzhou, describe in a joint memorial:

In order to support the militarisation in Zhili and Fengtian, it is essential to increase the numbers of soldiers in Dengzhou. Dengzhou is important because it is a strategic city where we can oversee a large body of seawater attached to Shandong and Fengtian. The strategic location of Dengzhou enables us to control the seaway from Japan to Tianjin, as well as the sea routes from Fengtian to Zhili. It is where we can attack pirates and prevent foreigners from entering the northern part of our empire. At present, we only have 187 soldiers stationed in Dengzhou, which is obviously insufficient to protect the country”.Footnote 55

The above memorial indicates that Dengzhou's maritime military defenses were not developed after 1783. From then until the early nineteenth century, no significant effort was made to expand or consolidate its naval structure. While not neglecting the importance of the Bohai Gulf, the Qianglong Emperor relied on the navies stationed in Daigu and Fengtian to police and patrol the Bohai Sea, rather than expanding or fortifying the Dengzhou navy itself.Footnote 56 Compared Daigu and Fengtian, which developed larger naval bases, Dengzhou was no longer as advanced as in previous decades.

Trade and Commerce

In the eighteenth century, Dengzhou was a trading port as well as a naval base – although its military importance exceeded its economic importance. As of December 1683, two months after Taiwan was annexed by the Qing Empire, Kangxi decided to lift the ban on Chinese navigation overseas by opening at least 50 large and small coastal ports to sea trade.Footnote 57 Together with Tianjin in Zhili, Ningbo in Zhejiang, Yuntaishan in Jiangsu, Zhangzhou in Fujian, Dengzhou was one of the port cities in northeastern China that was opened to maritime trade, where merchants could conduct business and reside in the city. This is inscribed on a stone erected in the Penglai Pavilion: “Dengzhou (in the Kangxi-Yongzheng period) was the door for foreign merchants to trade with us and for Chinese merchants to trade abroad”. Although a distinct customs office was never established in Dengzhou, the Dengzhou governor was assigned to regulate and supervise all manner of trading activities. Compared to newly opened sea ports in the south, which attracted large numbers of western and Southeast Asian traders, Dengzhou had a smaller volume of trade. This is largely because it was not profitable enough for western and Southeast Asian traders, coming mostly from the Strait of Malacca, to sail north if they could conduct their business in Canton. But this does not mean that Dengzhou lacked economic significance as a sea port in international trade at that time.

As briefly introduced in the previous section, Dengzhou had the good fortune of being located at the nexus of three important trade routes connecting Zhili, Liaodong, and Korea. The development of local commerce, ginseng trade, soybean paste production, and transportation during the eighteenth century contributed significantly to sustaining Dengzhou during this period and combined to revive its economy after the economic downturn of the late seventeenth century. Emperor Kangxi's lifting the sea ban promoted the development of coastal ports by legalising ocean shipping and permitting increased opportunities for maritime business. Kangxi's proclamations also served to strengthen government control of trade and produce tax revenues. Among the new regulations, laws that monitored and taxed the newly legalised sea trade were rigorously enforced. The emperor issued this imperial edict in 1683,

“Without a regular means of collection, levying duties would trouble maritime traders, who would be subject to extortion from customs officials. Therefore, it is necessary to establish the same system in coastal regions as in inland regions and appoint special officials to deal with related affairs”.Footnote 58

The Kangxi Emperor thus appointed two Manchu officials, Igeertu and Wushiba, as the first heads of the Guangdong (Guangzhou, Xiangshan, and Macau) and Fujian (Fuzhou, Nantai, and Xiamen) commissions, while two more customs offices were established in Zhejiang (Ningbo and Dinghai) and Jiangsu (Huating and Shanghai) over the subsequent three years. The establishment of the new customs structure suggests that the Qing was keenly aware that the trading patterns and dynamics of the maritime frontier were different from those of land and river regions.

Although Dengzhou was not one the four main customs bureaux opened in the Kangxi era, it was similar to the seaports where custom offices were located. The seafront was covered with warehouses encircled by storage yards. Surrounding them were competing companies established by Chinese managers and stock account intermediaries serving Korean and Japanese traders. As He Changling illustrated,

Since the sea ban was lifted by the Kangxi Emperor, the seaways were widely opened to traders. Maritime traders, who intended to reach Tianjin and Fengtian, began to pass by/ stop by Dengzhou. Thousands of trading vessels and businessmen help flourished the seawater of Dengzhou, in which you could hardly find this prosperity in the past (henggu weiyou).Footnote 59

He Changling may be a bit exaggerated, but we are certain that the economy of Dengzhou was gradually reviving after the sea ban was lifted. Especially during the Qianlong period, when the eight trade routes were found along the coast, the seafront of Dengzhou was covered with warehouses encircled by storage yards. Surrounding them were companies established by Chinese managers and intermediaries serving Chinese from other provinces, and sometimes Korean, Manchu, and Japanese traders.Footnote 60

The vessels anchored in Dengzhou were mostly sand junks (shachuan), which could carry up to 1,500 shi (or 90 tons, one shi being approximately 60 kg), medium-sized vessels with a capacity of 800 to 900 shi, and small boats with a capacity of only 400 to 500 shi.Footnote 61 They carried fertilizer and soybeans from northern ports to Shanghai and took cotton textiles north. During the Yongzheng period, the sea route connecting Shandong and Shanghai was one of the most lucrative in north China sea trade. Zhang Zhongmin has estimated that, by the middle of the high Qing, the fertilizer trade alone amounted to more than two million taels annually.Footnote 62 Yet, as discussed earlier, Dengzhou's gradual decline in economic importance during the Qianlong era, due to its diminished military importance, must be kept in mind. Competing cities located in Northeast China, such as Tianjin, Jinzhou, Niuzhuang, and Jiaozhou, replaced it in importance.Footnote 63 For example, due to its proximity to seaports in Southern China, Jiaozhou gradually became the major port of entry and departure for produce and coastal traffic in what is today the East China Sea region.Footnote 64 By the late eighteenth century, Jiaozhou also received imports of such items as ginseng, bird nets, and seaweed from Korea and Japan.Footnote 65 Dengzhou only regained its economic importance when the British required more port cities be opened for free trade in the 1858 Treaty of Tianjin.Footnote 66

Throughout the eighteenth century, Dengzhou's merchants (Dengshang) had high social status, like those in other notable port cities. The Dengzhou merchants, who were usually labelled “Denglai businessmen,” were active in important centres of trade along the coast of China. As the Dengzhou fuzhi and other provincial gazetteers record, “(Dengzhou merchants) are everywhere to pursue profits (min duo zhuli yu sifang)”.Footnote 67 Exploring both inland frontier regions and troubled waters, the maritime merchants from Dengzhou trade with peoples across the Bohai region as well as the southern part of China, such as Jiangsu and Zhejiang.Footnote 68 One of the most enduring legacies of Dengzhou merchants is perhaps the design of the dongchuan or dengyou a merchant vessel specifically adapted to sail safely across the Bohai Sea. In a recent study of Dengzhou merchants, Tan Hongan suggests that the invention of the dengyou represents a highly advanced economic network created by the Dengzhou merchants in the Qing period.Footnote 69 The development of this ship was thus a unique symbol of Dengzhou merchants as well as of Dengzhou city.

Yet the reputation of Dengzhou merchants failed to sustain the city's economic importance in the Bohai region in the late eighteenth century. The rise of other large port cities such as Tianjin and Lüshun overshadowed Dengzhou's position.Footnote 70 The city was no longer as busy as before and most of the Dengzhou merchants moved their bases elsewhere. Those interested in Bohai sea trade preferred to set up their businesses in Tianjin,Footnote 71 while those favouring trade with southeastern China relocated to Jiaozhou. The harbour of Dengzhou thus stopped growing and the number of trading vessels anchored near shore declined,Footnote 72 whereas the city entered another wave of economic recession. Not until the 1820s did the economic significance of the city slightly rise again. In 1825, the Qing defined a new vision of a dual, collaborative approach to capital grain transport that relied on both transport by sea from Shanghai to Tianjin as well as on long-established imperial shipment on the Grand Canal. Dengzhou was one of the administrative offices along the sea route linking Shanghai and the northeast coast. In order to substantiate the managerial framework for grain transport on the sea route, the Qing officials sought to create an administrative infrastructure that enabled designated civil and military officials to respond directly to coastal security, navigational, and organisational difficulties. The organisers thus expanded the network of guard stations in Dengzhou and along the coast of Shandong. They also increased the number of navigational markers near Dengzhou to alert shipmen to navigational hazards.Footnote 73 Due to the reinforcement of navigational and security operations, the economy of Dengzhou experienced its first wave of revival. The second wave of revival came later after the Second Opium War, when the British and the French forced the Qing court to open more treaty ports to accommodate the expanding trade in Asian markets and European interest extended beyond China's southeastern coast into the northeast—and specifically the Bohai zone.Footnote 74 Following their investigation of the Shandong peninsula, the British chose Dengzhou because of its manageable size (as with their choice of Hong Kong) and its proximity to the capital. Like the treaty ports in Southeast China, Dengzhou was witness to the incursion of high imperialism in China in particular and East Asia in general.Footnote 75 Along with Niuzhuang on the Liaodong peninsula, Dengzhou was one of the two treaty ports open to foreign traders in the Bohai zone. That extended transcultural interactions beyond the circle of trade with Korea and Japan to those of diverse and broad scope. The intercultural interactions that resulted from this are certainly worthy of investigation in future research.Footnote 76

Conclusion

In his “On the Evolution of the Port City,” Rhoads Murphey eloquently argued that port cities are different from other inland and hinterland cities in terms of their economic, social, political and cultural development. For Murphey, the difference between a port city and other type of cities is predominately determined by the function of a port city (the port function). Murphey defines “port function” as follows:

“The true port city by definition links very distant maritime spaces, and this is the reason for what is perhaps its most noticeable characteristic. Ports are inclusive, cosmopolitan, while the inland is much less varied, much more exclusive, single faceted rather than diverse. . .Port functions, more than anything else, make a city cosmopolitan. . .A port city is open to the world, or at least to a varied section of it. In it races, cultures, and ideas as well as goods from a variety of places jostle, mix, and enrich each other and the life of the city. The smell of the sea and the harbor, still to be found. . .in all of them, like the sound of boat whistles or the moving tides, is a symbol of their multiple links with a wider world, samples of which are present in microcosm within their own urban areas”.Footnote 77

By the end of the late eighteenth century, Dengzhou was considered to be “cosmopolitan,” open to the wider world, especially to the Northeast Asian market thronged with Chinese (from the north and the south), Korean, Japanese, Manchu, and sometimes Russian traders. Situated at the nexus of three important trade routes connecting Shandong, Zhili, Liaodong, and Korea, the seaborne economy of Dengzhou was deliberately monitored and supervised by the government. The development of ginseng trade, local commerce, and transportation contributed significantly to Dengzhou's importance. Hundreds of ocean craft plowed the port of Denghou as their sails billowed in the winds that tied together transcultural interactions in Northeast Asia. Yet the dramatic rise of Tianjin and Jiaozhou in the late Qianlong era overshadowed the economic significance of Dengzhou, quickly displacing it as trading hubs of northeast Asia. Only after the British declared their interest in urbanising Dengzhou in the mid-nineteenth century was economic development in the city revived.

However, it must be noted that the “port function” of Dengzhou differed from other inland Chinese cities, not only in terms of trade and commerce, but in its unique military development—particularly in relation to port cities on China's southeastern coast. On one hand, the geographical location of Dengzhou made it a natural port of call for travellers in Northeast Asia; on the other, its strategic location made it a magnet for the Qing administration to set up a naval base to protect the imperial region. As we have seen in this paper, the Qing court in the eighteenth century did not ignore the significance of Dengzhou as well as the Bohai Sea. By deploying vessels and sailors within the Dengzhou seawater, the government considered Dengzhou a strategic center to oversee the Bohai region, connecting three coastal provinces in northeastern China. In order to govern this piece of maritime territory thoroughly and deliberately, the Dengzhou navy was responsible for policing the region on a regular basis as well as monitoring and regulating all other naval stations. The maritime militarisation project prior to the middle of the Qianlong period integrated Dengzhou into a military network connecting Zhili, Liaodong, and Shandong, the three provinces most significantly underlying Manchu government rule. Yet the military development of Dengzhou cannot be seen in isolation from its immediate environment. Dengzhou's military importance gradually weakened during a long period of peace across the Bohai Sea. The Qianlong emperor thus reduced the number of soldiers guarding the Dengzhou naval base and came to rely more on the Daigu and the Fengtian navies to police the Bohai zone. As a consequence, Dengzhou’ maritime militarisation in the late eighteenth century regressed from what it had been decades before.

In studying the connection between China and the sea in the eighteenth century, western historiography has long focused on port cities in southeast China. The scale of shipping along the northeastern coast was smaller than that along the southeastern coast because most of the East-West transactions took place in large coastal cities such as Canton, Amoy, and Fuzhou. Yet, to fully evaluate maritime policy during the high Qing and comprehend the coastal history of China, it is not enough to merely inquire into the significance of the southeastern region; the northeastern region, and the Bohai zone in particular, can hardly be ignored. Dengzhou is but one of the cities in that zone that deserves attention. The histories of Yingkou, Weihai, and Qinhuangdao, for instance, are equally worthy of investigation, especially now when the PRC government is earnestly developing the Bohai Seaway Strategic Project (BSSP; Huan Bohai jingji quan zhanglüe jihua). In order to get a relatively thorough picture of the history of Chinese port cities and China's connection to the sea, I would like to take this opportunity, once again, to invite potential researchers to move northward in their research and not to confine themselves to the “Southeast China-centric” framework in studying the maritime history of late imperial China. I believe this is a constructive way to gain a better understanding of the history of coastal China as well as a comprehensive picture of maritime Asia in the early modern period.

We should also try to go beyond the Asian setting by comparing port cities in Northeast China with those in the West. Although the two were certainly not identical in terms of political functions and economic significance, their “port functions” may have more in common than is recognised. The study of Dengzhou as both a military and commercial port city reminds me of the chronicles of Sevastopol, a port city in Russia surrounded by the Black Sea. Both a naval base and a commercial port city in Russia, Sevastopol experienced serious ups and downs over the eighteenth century. Much the same occurred in Dengzhou at about the same time, following Emperor Qianlong's decision to reduce the number of soldiers in the Dengzhou navy, which then led to the economic decline of the city. Such comparison may therefore serve as a window into the global history of urbanization of port cities in the pre-industrial era. By investigating these cases, we can understand how port cities experienced unique and similar patterns of urban development within different political, cultural, and economic contexts. This might also help trace the origin of “cosmopolitan features” that exist in the port cities of today's globally connected economy.

Chronicle of Dengzhou (1644-1840)