Nothing appears more surprising to those who consider human affairs with a philosophical eye, than the easiness with which the many are governed by the few; and the implicit submission, with which men resign their own sentiments and passions to those of their rulers. When we enquire by what means this wonder is effected, we shall find, that, as force is always on the side of the governed, the governors have nothing to support them but opinion. It is therefore on opinion only that government is founded; and this maxim extends to the most despotic and most military governments, as well as to the most free and most popular.

Public Opinion, Public Rancour

Inter arma silent musae … well, not quite. The Muses in nineteenth-century Europe did not fall silent amidst warfare: on the contrary, they raised their voices to lend moral support to the fatherland. In returning to the rousing songs and films that we noted in Chapter 1 of this book, we also return to the main geological fault-line in the political landscape of Western Europe: the competing German and French claims on the Rhine – either as a French natural frontier or as a German national artery.

German–French wars since the 1790s have always spawned battle songs, foremost among them ‘La Marseillaise’ and ‘Die Wacht am Rhein’; and we have seen how cultural geopolitics post-Waterloo put Alsace-Lorraine and the Low Countries high on the agenda of intellectuals such as Arndt. Throughout the nineteenth century there is a steady trickle of Romantics cheering on their national causes (Liszt and his sabre) or even intervening proactively in their political activities: Shelley distributing seditious pamphlets from a Dublin lodging-house, Byron joining the Greek War of Independence, Wergeland in Norway and Petőfi in Hungary staging national declamations in public. These poetic interventions, and more specifically their embodied proclamation in the form of songs and anthems, fed into a force that became increasingly powerful in the course of the century: public opinion. The hapless Napoleon III after his defeat stated that it was public opinion that had made the 1870 war inevitable, and this is supported not only by the opening pages of Zola’s searing novelistic account Le Débâcle (1892; Zola wrote about the Parisian run-up from personal experience) but also by the memoirs of various public figures. General François-Charles du Barail, for instance, in listing the many anti-Prussian parties that lured France into a hasty declaration of war, finishes his list with ‘the extreme right-wing chauvinists, who hoped that the war would restore authoritarian rule’ and, finally,

the people in the streets: the workers shouting ‘On to Berlin!’; the patrons of brasseries and elegant cafés breaking their glasses of beer or liqueur over the heads of those unfortunates who had the temerity of speaking up for peace; the theatres full of crowds singing the Marseillaise and also shouting ‘On to Berlin!’; the ignorant and the learned, from the streetcorner porter to [the journalist] Emile Girardin, laying wagers as to the date when we would march into Berlin.1

The mention of ‘La Marseillaise’ need not surprise us. On the German side, it was this war that lifted the older ‘Wacht am Rhein’, composed in 1840, to the status of a nationwide battle anthem.2 The battle songs of earlier conflicts were reprised, as they were to be reprised in their turn during the World Wars of the next century. (We have seen how choirs in the 1860s had already intoned their readiness to do battle over the Rhine). That alone should alert us that the culture of warfare is not an ad hoc accompaniment to the events of the day; it is a constantly available repertoire for the events of the day to dip into should the occasion so require. The successive cross-Rhenian confrontations between Germany and France amply illustrate the formation and persistence of that repertoire, latently quiescent during the intervals of peace, saliently prominent during the succeeding crisis moments – in 1792, in 1813–1814, in 1840, in 1870, in 1914, in 1939–1940. It is, in fact, the persistent availability of that repertoire and that accumulating sedimentation of memory, as much as the long-term foreign policy aims of states, that connects those crises into an echo-chamber of hereditary hostility. The older texts were recalled and amplified at each new occasion, and fresh ones were added to them.3

The crushing Prussian victory was compounded by the terrible events around the Parisian Commune, which ripped fraternité up into fratricide. The Third Republic drank to the dregs the bitter potion of defeat and, as Wolfgang Schivelbusch has shown in his Culture of Defeat, carried a destabilized and dysfunctional public opinion into the fin-de-siècle. Its grievance politics would include various strands of Bourbon, Orléans and Bonapartist restorationism, reactionary ultramontanism (the National Pledge campaign, culminating in the building of the Sacré-Coeur on MontmartreFootnote *), paranoid anti-Semitism (the grinding, endless Dreyfus affair) and the seeds of a rancorous nationalism. The word ‘nationalism’ was coined by the journalist Maurice Barrès (in the writings collected in his Scènes et doctrines du nationalisme, 1902); as a political programme, Barrès-style nationalism organized itself into a Ligue de la patrie française that spawned, in 1899, the proto-Fascist Action française journal and movement.4

Victorious Prussia, for its part, realized that it was now facing a deeply embittered, vengeful neighbour. Peace terms were imposed that aimed to thwart the vanquished foe in future war efforts. ‘Reparation’ payments were imposed that recalled those imposed by Napoleon on vanquished Prussia in 1810 and that would in turn be remembered when heavy burdens were laid on Germany after 1918. In a back-and-forth of victories and defeats between France and Germany since 1815, the successive iterations of Schivelbusch’s Culture of Defeat may well be seen as a repeated ‘tit-for-tat culture’ – witness also the annexations and reannexations of Alsace and Lorraine. In 1871 Alsace and Lorraine were annexed in large part to make sure that future French attacks would have a more distantly removed base of operations than Strasbourg.Footnote ** Emperor Wilhem I in a letter to Empress Eugénie ruefully acknowledged the likelihood of another, future war, and continued: ‘This sad consideration, and not the desire to enlarge my fatherland (whose territory is sufficient in size), forces us to insist upon territorial transfers which are only intended to push back the starting base of such French armies as will want to attack us in the future.’5 This is in line with the habit among bellicose states to present attack and annexation as a forms of self-defence; but in any case this military geopolitical pragmatism was not how the transfer was sold to the public at large. The justification before the court of public opinion was cultural and historicist, in the very same terms that had been used by Arndt: Alsace and Lorraine, it was asserted, culturally belonged to Germany, had seen their political ties with Germany severed by unnatural force, and were now harmoniously reunited with their true fatherland. The Prussian historian Treitschke repeated Arndt’s pamphlet ‘The Rhine, Germany’s River, Not Germany’s Border’ of 1814 practically verbatim, adding that he had, in fact, very little to add to the masterful arguments that Arndt had put forward half a century previously.

Were I to marshal the reasons which make it our duty to demand this, I should feel as if the task had been set me to prove that the world is round. What can be said on the subject, was said after the battle of Leipzig, in Ernst Moritz Arndt’s glorious tract, ‘The Rhine the German river, not the German boundary’; said exhaustively, and beyond contradiction, at the time of the Second Peace of Paris [1815], by all the considerable statesmen of non-Austrian Germany – by Stein and Humboldt, by Münster and Gagern, by the two Crown Princes of Wurtemberg and Bavaria; and confirmed, since that time, by the experience of two generations.6

Treitschke’s arguments were aimed both at a domestic audience and an international one; his ‘What Do We Demand of France?’ appeared in 1870 in the Preussische Jahrbücher and also as a brochure, and an English translation appeared in London that same year. Another direction was taken by the revered classical historian Theodor Mommsen. He addressed a series of open letters to Italian periodicals, also published in brochure form as Agli italiani. Mommsen argued that, much as the Italians had in their Risorgimento lawfully annexed Milan and Venice (and he injected also some anticlerical notes by reminding the Italians how the Papal States had long been kept out of Italy by French interference), so too the Germans were justified in rounding off their unification movement by the incorporation of Alsace and Lorraine.

What was new here was that the justification for the nation was now delivered not in exhortatory poems but in discursive prose; not by poets but by history professors. The intellectual professions were now finding a new role as national apologists; the heyday of the ‘political professor’ had arrived. After 1918, this ‘intellectual nationalism’ (Martha Hanna’s phrase) would be bitterly denounced by Julien Benda in his Le trahison des clercs (1927).7 But knowledge production and the sphere of intellectual pursuits had never been quite aloof or separate from a commitment to the nation; it merely found a new field of application in the developing medium of war propaganda.

Political Professors: Fichte to Fustel

Treitschke’s overt recall of Arndt is significant: the anti-Napoleonic Wars of Liberation (Befreiungskriege) of 1813 were remembered as a glorious alliance between military and cultural mobilization, with Arndt, Schleiermacher, Görres and others celebrated as the intellectuals who had prepared the people and the Prussian state for insurgency. Here lay the prototypes of the ‘political professors’ of the generation of Treitschke and Felix Dahn. Foremost among them was Johann Gottlieb Fichte, he of the Reden an die Deutsche Nation. He had enlisted when in 1813 anti-Napoleonic citizen militias were mobilized. The figure he cuts as a fifty-one-year-old, martially brandishing a sabre and carrying holstered pistols in a belt around his portly girth, is not altogether impressive (Figure 11.1); learning and armed combat are, as we can see here, two very different callings. That they converged in the 1813 moment had proved highly memorable.

Figure 11.1 The philosopher Johann Gottlieb Fichte on parade as a member of the Prussian Landwehr (1862 engraving after Carl Zimmermann, 1813).

When, after the Napoleonic wars, academics wanted to prove their usefulness to the fatherland they usually did so as ‘brains’ rather than ‘muscle’, and mostly in peacetime deliberations on domestic policy rather than under the direct shadow of actual action in the field. The mobilization of Treitschke and Mommsen manifested the type of public–political leverage that Grimm and the Germanisten had tried to obtain in the 1840s; and it shows how a new type of professor had come to wield considerable influence as public intellectuals. A class of ‘German mandarins’ has even been defined as such by Fritz Ringer in a landmark study.8

France responded in kind. If Germany had the Preussische Jahrbücher, France by now had the Revue des Deux Mondes. Such opinion-making periodicals, independent but semi-official and addressing educated readers, were among the important new platforms of the period. Ernest Renan from the beginning countered German triumphalism by warning them sternly that hubris comes before a fall; Schivelbusch rightly read that as a somewhat pedantic one-upmanship on the part of defeated enemies, part of the see-sawing alternation of boastful victors and peeved losers.9 Something altogether new and more important crystallized when an academic refugee from Strasbourg arrived in Paris to take the floor: Numa Fustel de Coulanges. Breton by birth and Parisian normalien by education, he had taught archaeology and ancient history in the Alsatian capital but left the city and its university when it was annexed into Germany. In Paris he would find employ at his École normale supérieure and ultimately at the Sorbonne, and he would become an inspiring voice from that position. It was Numa Fustel de Coulanges who first tackled the German justification for the annexation of Alsace and Strasbourg. In his L’Alsace est-elle allemande ou française? Réponse à M. Mommsen (1870) he developed what later became such a powerful line of reasoning in Renan’s Qu’est-ce qu’une nation? (Reference Renan1883): that in deciding the question of national belonging, what should weigh most heavily was the self-identification of the people concerned. Fustel’s riposte to Mommsen has been overshadowed by Renan’s more famous, indeed classic tract; but it is worth zooming in on because it states things more crisply than Renan and illustrates a telling conjunction of intellectual and political trends.

Fustel was a close colleague of Mommsen. Both had done path-breaking work in the study of Roman institutions (Mommsen’s Römische Geschichte, 1854–1856; Fustel’s La Cité antique, 1864). In the course of his own work on ancient history, Fustel had become convinced of two things. One was that the Roman conquest of Gaul had laid the preconditions for the French state by imposing an institutionalized governance on what had been an assemblage of different tribes. In this view, he followed Romantic historians such as Thierry and Michelet. Where he differed from those Romantic forerunners, however, was in his view of the subsequent Frankish conquest of Latinized Gaul. In his view, this had been a matter of gradual infiltration rather than a ‘conquest’ properly speaking. This neatly subverted the Romantic two-nations view, according to which the conquering Franks had been the ancestors of the nobility, ruling the country by right of conquest; whereas the subjected Gallo-Romans were the ancestors of the Third Estate. In that view, the French Revolution had been the long-awaited reassertion of popular Gaulish rights against the conquering Frankish aristocracy. The two-nations view was certainly appealing; it could draw on eighteenth-century roots, even on a turn of phrase in Sieyès’s What is the Third Estate?; it had an analogue in the Saxons-and-Normans polarity in English history writing, as propounded in Walter Scott’s wildly popular Ivanhoe; and it had inspired, in the course of the century, many a popularizing history account by the likes of the historian Henri Martin, and the novelists Alexandre Dumas (Francs et gaulois) and Eugène Sue (Les Mystères du peuple). But Fustel himself drew from his historical studies a different conclusion, and in the process came to reject the entire ethnohistorical paradigm of Völkergeschichte, whereby modern societies were seen as the outflow of the patterns established in ancient tribal warfare.10

It must have been particularly irksome to Fustel that this ethnohistorical argument, which he had been at pains to purge from his historical analysis, was precisely the justification that was invoked by the likes of Treitschke and Mommsen, with Treitschke even falling back, overtly, on old Arndt. That was the background to Fustel’s feisty rebuttal of Mommsen’s Agli Italiani. Is Alsace, he asks, German or French?11

Prussia thinks that it can resolve that question by might; but Prussia is not satisfied by force alone, and would like to add Right to that. Thus, while your armies invaded Alsace and bombarded Strasbourg you tried to prove that it was your Right to do so …. Alsace, you assert, is a German region and therefore must belong to Germany. It used to once, and you conclude that it must therefore be given back to you. German is spoken there and you infer that this gives Prussia the right to annex it. … This you call the nationality principle.

Fustel explodes this in successive stages. He begins by exposing the invocation of the ‘nationality principle’ as a mere pretext for raw power politics.

As you see it, that principle would authorize a powerful state to appropriate a province by force because it is inhabited by the same race. Most of Europe, more commonsensically, would understand that principle as authorizing a region or a population to reject the rule of a foreign hegemon. … It may bestow certain rights on Alsace itself, but none on you to overrule it. In invoking that principle regarding Schleswig and Alsace … Prussia is misapplying it. It is a right for the subaltern, not a pretext for expansionism; the nationality principle is not a new way of saying that Might makes Right.

The further argument then sets out to demonstrate that the Fichtean nationality markers of language and descent (‘race’) are futile.

If the nationality principle means that Alsace has the right not to be ruled by foreigners, then the question becomes: who is the foreigner here, France or Germany? You assert, Sir, that Alsace is of German nationality. Are you sure about that? … How do you recognize a nationality, a fatherland? You think you have proved the German nationality of Alsace because the population is German by language and race. But it baffles me that a historian like yourself chooses to overlook the fact that neither language nor race makes a nation.

Fustel’s demonstration boils down to the points that ethnically similar populations have founded different states, and that states can gather into a shared nationality linguistically mixed populations of diverse (and usually mixed) ethnic descent. This line of reasoning has become familiar: Renan (Reference Renan1883) argued along similar lines in Qu’est-ce qu’une nation? But for Fustel in 1870, this is a hard-won fresh insight based on his historical and archaeological work and on his own rejection of the French two-nations model.

From there, like Renan after him, he goes on to locate the true bedrock of national identity, emically, in the nation’s act of self-identification.

Nations are distinguished neither by race nor by language. People feel in their hearts that they belong together once they share ideas, interests, emotions, memories and hopes. That is what constitutes a fatherland. That is why people wish to walk, work, fight together, live and die for each other. A fatherland is what you love. It may be that Alsace is German by race and language, but by nationality and in its sense of fatherland it is French. And do you know what made it French? It was not the conquest by Louis XIV, but our revolution of 1789.

To bolster this case, Fustel asserts that the feelings of the Alsatians are, in fact, pro-French and anti-German, and that the civic legacy of the French Revolution has left more vivid and important traces in the present than the ancient roots of language and ethnicity. Fustel contradicts German assertions as to the German-mindedness of the population. He states that he himself never experienced anything like the purported reservations against Parisians (‘I pride myself on knowing how kindly Alsace receives them’) and instead offers numerous examples of the stubborn resistance of the local population to the invading German armies (‘they spoke your language, but they did not consider themselves your compatriots’). All this follows to some extent the yea–nay patterns of wartime propaganda – Grimm in 1814 had argued that the Alsatians had remained German-minded despite generations of French rule,12 and now Fustel argues the opposite. What is the historian to make of it? In asserting the French-mindedness of Alsace, Fustel was to some extent invoking existing French attitudes: as expressed, for example, in the Alsatian-propagandistic romans nationaux of the popular novelistic duo Erckmann/Chatrian and the emerging vogue for brasseries alsaciennes on the Parisian boulevards.13 But his assertion of a deep-seated anti-German feeling among the Alsatian population is more believable: the Germans themselves developed an almost phobic mistrust of the figure of the franc-tireur, the armed civilian who behind the lines snipes at German troops. For Germans, this was a sign of Gallic treacherousness, and their fear of it was such that in Belgium in 1914 mass executions were carried out among the civilian population on the basis of rumoured franc-tireur activities.14 That phobia cannot have grown out of an open-armed welcome by fraternal fellow Germans in 1870–1871.

Be all that as it may, the most important point is reached when Fustel fundamentally denies that deep historicism as such, Völkergeschichte-style, can have any use whatsoever when discussing contemporary issues.

For Alsace, the fatherland is France, and Germany is foreign. None of your lucubrations will change that. You may invoke ethnography and philology, if you will, but we are not in a university lecture-hall here. … So let us speak no more of nationality and above all stop saying to the Italians that ‘Strasbourg belongs to us the way Milan and Venice belong to you’; for the Italians might reply that they never bombarded either Milan or Venice. … You, Sir, are an eminent historian. But when we discuss current affairs, let us not get fixated on history. … History may tell you that Alsace is a German land; but the present proves to you that it is French. It would be childish to argue that it should revert to Germany because some centuries ago it used to form part of it. Are we going to re-establish everything that once used to be? And in that case, if you please, what Europe would that be?

This is truly a new turn in the discussion of national identity. Cultural-historicist arguments, so long dominant (including within France), are now dismissed in favour of a modern, ahistorical approach: a legal one, announcing the idea of international law and the principle of self-determination.

Let us be of our own time, rather. We have something to guide us that is better than history. We possess in this century a principle of public law which is infinitely clearer and more incontestable than your pretended nationality principle. Our principle is that a population can only be governed by institutions which it freely accepts, and that it should not belong to a state unless by its own will and free consent. … What is all this talk of ‘claims’? Strasbourg belongs to no one. Strasbourg is not an object to be possessed or rendered. Strasbourg is not ours, it is with us. We feel that Alsace should remain a French province, but take note on what basis we do so. Do we say so because it was conquered by Louis XIV? By no means. Do we say so because our defence requires it? No. … France has only one reason for wanting to keep Alsace, and that is that Alsace has bravely demonstrated that it wished to remain with France. Bretons and Burgundians, Parisians and Marseillais, we fight you over Alsace; but let there be no mistake: we fight, not to maintain a hold over it, but we fight to prevent you from doing so.

Whatever was said, more famously, by Renan a decade later is said much more clearly and pointedly here. When Renan gave his lecture Qu’est-ce qu’une nation? at the Sorbonne in 1883, he pointedly avoided any mention of Alsace, Lorraine or Strasbourg, and thus also pre-empted the charge of special pleading: his stance is not that of a champion of his country against Germany but that of a dispassionate philosopher seeking to establish the truth. If Renan refers to Germans at all, it is only as the tunnel-visioned intellectual tradition that deterministically and essentialistically wants to define nationality etically (in terms of its component cultural factors); whereas he, with ‘French’ clear-sightedness, argues that nationality is defined emically, by how people experience their culture and their allegiance. That disinterested stance has ensured for Renan’s analysis a classic status in the theory of national identity, and deservedly so. Much of what he says about the importance of memory in national collective identification (memories glorious and painful, triumphant or grievous, and even memories elided or sanitized) is still authoritative 150 years later. But for his audience, the point, though unstated, was lost on no one, and if Renan called national identity an ‘everyday plebiscite’ (i.e. an ongoing collective commitment), the challenge to the Germanization imposed from above on Alsace and Lorraine was obvious. And here, again, Renan had the intertext of Fustel’s earlier arguments to rely on.

What Renan does in Qu’est-ce qu’une nation? is to transmute the political French–German antagonism over Alsace-Lorraine into a philosophical French–German incompatibility between civic voluntarism and ethnic-essentialist determinism. He presents ethnohistorical essentialism, generally and without reference to the contested Alsatian annexation, as ‘the German way’ of seeing national identity, while presenting democratic, self-choosing voluntarism as ‘the French way’. Ever since, this perspective has burdened the debate on the shifting ethnic/civic weightedness of national identity discourse: ‘ethnic’ nationalism is denounced as a German-obscurantist bad-cop side of the coin as against the French-enlightenment good-cop side of ‘civic’ nationalism (as if Gobineau, the Dreyfus affair, Barrès’s vitriolic xenophobia and the Action française somehow don’t count). In the twentieth century Hans Kohn (Reference Kohn1950, Reference Kohn1955), writing in the Cold War climate, aligned ‘civic’ nationalism with ‘Western’ values and ‘ethnic’ nationalism with Oriental despotism.Footnote * To be sure, German intellectuals in the century after Arndt did themselves no favours by following a völkisch sliding scale that led from Felix Dahn to Houston Stewart Chamberlain of unhallowed memory. A discourse continued to hold sway that had been forged when Arndt and his generation repudiated the overpowering might of Napoleonic tyranny; but that discourse was now quite out of date, overtaken by Bismarck’s victoriously aggressive expansionist wars of the period 1864–1871. Even in the triumphant, overpoweringly mighty new Reich, its international position continued to be viewed in the ingrained terms of the 1813 moment and through the defensive lens of Arndt’s anti-Napoleonism.

This is not lost on Fustel. The victorious Germany of 1871 cannot claim the same position as the underdog Germany of 1813; Treitschke’s recycling of Arndt is an incantation, not an analysis. That said, Fustel’s rebooting of the nationality debate, shifting it from historicism to international law, is also a little self-serving. He is rather conveniently forgetful of the burden of the past and of the fact that France itself had pursued geopolitical expansionism with strong-arm tactics of the ‘Might makes Right’ type. Fustel may consider Louis XIV’s conquest as being water under the bridge, and he never even mentions Napoleon, but that was easier for him as a Frenchman than for the Germans remembering the devastations of those wars of conquest. The picturesque ruins dominating the Romantic imagery of the Rhine valley had in most cases been turned into ruins by Louis XIV’s rampaging armies. And the justification for Louis’s expansionism had in fact not been so very different from that of the Prussian expansionism that Fustel denounces. Louis’s marshal Vauban had aimed to consolidate the territory of France by gaining the Rhine as its natural frontier in the east; and that expansionism was maintained, across regime changes, by Danton, by Napoleon, by Thiers (during the 1840 Rhine Crisis). Even a young lieutenant Charles de Gaulle bought into it, if his 1915 correspondence is anything to go by. He optimistically predicted a ‘decisive victory’ ‘which will chase the enemy out of Belgium, which will enable us, if we can muster the necessary audacity, to take their place in that country, and which will yield to us, if we can will it, our natural frontier: the Rhine.’15 Small wonder that Germans, mindful of their history, were a little defensive about the Rhine, or that French occupation policies in the post-1919 Rhineland touched a raw nerve in Germany.16 Il y avait de quoi.

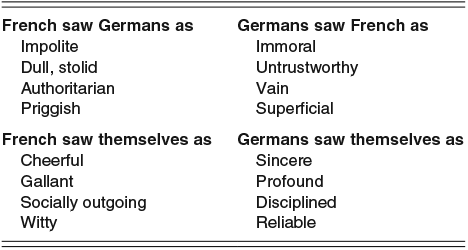

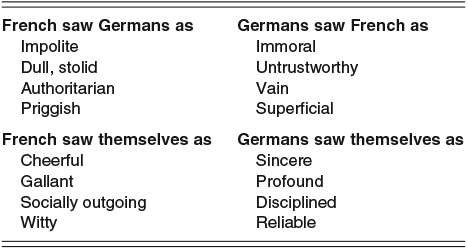

It makes perfect sense to abandon the stranglehold of historicism in favour of a more ‘modern’ approach to the nationality principle; but modernity cannot abolish memories. The year 1871 itself turned into such a memory for both warring parties. In 1914, both saw the new war, as Wilhelm I had foreseen, as a rematch of the older one. One thing that had carried over from 1871 to 1914 was the anthropologization of the terms of conflict. In their 1871 defeat, French writers adopted the rancour that Germans such as Arndt had displayed under Napoleon. In no way were the French–German wars seen as state conflicts ‘continuing diplomacy by different means’; they were wars between nations with incompatible attitudes and world-views. An ethnotypical opposition clicked into place, schematizing the imputed character traits of the two enemies on ruthlessly binary, incompatible terms (Figure 11.2).Footnote *

Figure 11.2 French/German ethnotypes around 1914.

Figure 11.2Long description

The data mentioned is as follows. French saw Germans as impolite, dull, stolid, authoritarian, and priggish. Germans saw French as untrustworthy, vain, and superficial. French saw themselves as cheerful, gallant, socially outgoing, and witty. Germans saw themselves as sincere, profound, disciplined, and reliable.

Readers will notice how the left-hand column opposes boorish Germans with chivalric Frenchmen. From the time of Herder and Goethe (mid eighteenth century) onwards, a prevailing rejection of aristocratic values and a turn towards middle-class virtues had led to a revalorization of those ethnotypes, as per the right-hand column: French aristocrats were now deprecated, while the land of Kant, Goethe and Beethoven was admired.

In the vertical (top vs. bottom) alignment of these characterizations, the respective self-images (bottom pair) pan out as temperamental opposites. Aligned diagonally, we recognize the positive or negative valorizations of similar behavioural characteristics. What Germans considered, in themselves, as their characteristic sincerity, profundity, sense of discipline and integrity would in a French discourse be represented as signs of boorishness, dullness and an authoritarian and pedantic streak.

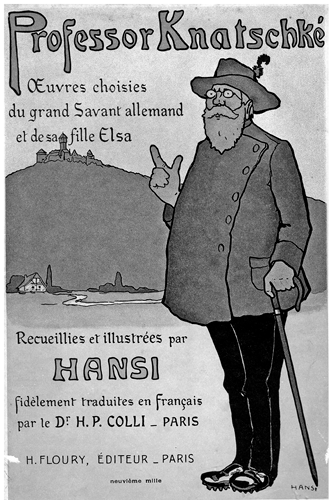

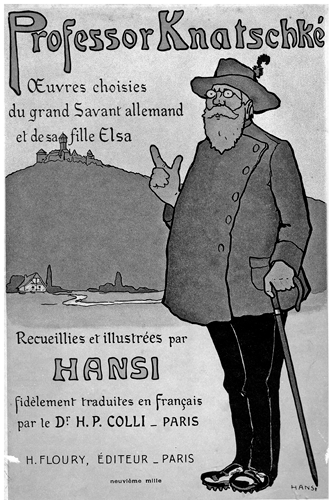

We can trace this in the shifting stock figure of the ‘German Professor’. Until 1870 he is an eccentric, an object of affectionate irony: the Bible-translating Professor Wittembach in Mérimée’s story ‘Lokis’; or the Hamburgian Professor Lidenbrock in Jules Verne’s Journey to the Centre of the Earth (1864). After 1870 he becomes the insufferable Professor Knatschke (Figure 11.3: a caricature created by the artist known as ‘Hansi’, Jean-Jacques Waltz) throwing his weight around in the annexed Alsace; or the murderous genocidal industrialist Dr Schulze, designer of the cannon-producing ‘Stahlstadt’ in Jules Verne’s The Begum’s Fortune (1879); Doktor Schulze’s evil plans are thwarted by the idealistic French hero Sarrasin and his Alsatian (!) assistant.17

Figure 11.3 The pedantic Professor Knatschke as drawn by ‘Hansi’ (1912).

Figure 11.3Long description

Cartoon-style book cover. In front of a stylized Alsatian landscape, with on the horizon the castle of Hohkönigsburg, stands the portly title figure, dressed in the style of a German hiking tourist. He wears hobnailed boots, a woolen jacket, and a hunting hat with a small plume. He carries a pointed Alpenstock walking stick and lifts a pedantic finger. His eyes are tiny behind his strong spectacles, and his features are hidden behind a bushy beard.

Similarly, what Germans denounced in the French as their immorality, untrustworthiness, vanity and superficiality would be seen by the French themselves as their light-heartedness, polite manners, awareness of social appearances and clear-sightedness. It is obvious that these traits aligned thus create polar opposites between the two nations’ respective temperaments. They were adroitly and venomously summarized by Ernest Renan when he gave his acceptance speech on becoming a member of the Académie française in 1878. No, he argued, France was not beaten down. Morally, France was still the superior nation it had always been, a beacon of civility that the self-proclaimed victors, still wallowing in their uncouth boorishness, could not hold a candle to. This is how he addressed his fellow académiciens:

You, like me, will mistrust a Kultur which fails to make people kinder or better. Nations which to be sure are very serious (for they reproach us our levity) are mistaken if they think that this will ingratiate them to the world. … Pedantic self-obsessed learning, a literature without cheer, a glum political life, an elite without glamour, an aristocracy without wit, a bourgeoisie without politeness: all that will not dispel the memory of our traditional French social life, with its glittering brilliance, so courteous, so eager to please. Only when a nation, by means of what it calls its seriousness and its thoroughness, has achieved what we have achieved by means of our frivolousness – better writers than Pascal or Voltaire, more charming women than those who smiled upon our philosophy, an enthusiasm more striking than that of our Revolution, more graceful manners and a more gracious life-style – only when it has become, in short, a more pleasant and spiritual society than that of our ancestors – only then shall we have been vanquished.18

I have here translated Renan’s culture with its German analogue. Kultur was becoming a key element in the German self-image as it opposed itself to France. The French had civilisation, which implied polite manners and an elegant, harmonious conformity of public standards, but which was also seen as something snobbish and superficial; to this was opposed the German idea of a more profound, deep-rooted Kultur, something inherited and naturally spontaneous rather than educationally or socially imposed – witness Fichte’s and Grimm’s link between love of the fatherland and deep affects such as filial piety, parental solicitude and homesickness from abroad. Kultur and civilisation became antithetical proxies to capture the incompatibility between the French and German national characters. A similar antithetical homology was that between Geist and esprit: the German word connoting earnest soulfulness, the other nimble wit.19 Thomas Mann invoked precisely this discourse in his wartime writings (Chapter 1).

Such ethnotypes had, over the preceding century, slowly become common currency in the world of learning; a Zeitschrift für Völkerpsychologie und Sprachwissenschaft had been established in 1860, and since the 1820s anthropologists and ethnographers had come to rely increasingly firmly on the principle of ‘national characters’.20 National stereotyping suffused the oppositional discourse of the decades between 1871 and 1914, when essentialist ethnotypes flourished as never before or since, almost abolishing the distinction between nation and race. They carried with them all the authority of the academics who endorsed them. Much of that discourse was debunked or dismissed in the course of the twentieth century; national clichés are now used more sparingly and back-handedly, often jocularly. But when wielded in earnest, ethnic cliché was best backed up by authors’ scholarly or intellectual prestige; and this in turn reinforced the importance of public intellectuals as authorities in the public debates about international frictions and conflicts.

These public intellectuals came out in full force in 1914.

Kultur, War, Propaganda

Wars were increasingly fought before the court of public opinion. The advent of photography and journalism on the battlefields of the Crimean War and the American Civil War had rendered the home front aware of its conduct, as Tennyson’s ‘Charge of the Light Brigade’ (1854) also testifies, and as is indicated by the careers of Florence Nightingale (who rose to fame among the Crimean wounded) and Henri Dunant (who conceived of the Red Cross on the battlefield of Solferino, 1859). Atrocities against civilians, now reported in large-circulation media, became a matter of public outrage; the philhellenic denunciation of the Ottoman-inflicted Massacre of Chios (1822) had been an early sign. The murderous repression of an anti-Ottoman revolt in Bulgaria in 1876 was widely reported and became notorious as the ‘Bulgarian horrors’; it led Gladstone to denounce the cruel Turks in ethnotypical terms as congenitally disposed to ruthless sadism and unfit for imperial rule. As a direct result, the Ottoman Empire was ordered to grant self-rule to the Bulgarian exarchate by the western powers at the Conference of Constantinople (1876); this was subsequently enforced by the treaty of San Stefano (which concluded the Russo-Turkish War of 1877–1878).

In these decades, people sought to control the horrors of modern warfare as these became noticeable to the general public. The first Geneva Convention (1864) was to be followed by additional ones in 1907, 1929 and 1947. In the drafting of such conventions, legal scholars found a new application for their expertise. Drawing on earlier texts such as Schmalz’s Europäisches Völkerrecht (1816), Klüber’s Droit des gens moderne (1819) and Bluntschli’s Das moderne Völkerrecht (1868), international law rose to prominence in the post-1871 decades, trying to control Might with Right. In time, legal opinion crystallized into institutions. Frédéric Passy’s Ligue permanente et internationale de la paix of 1868 was transformed into a Société française pour l’arbitrage entre nations in 1889. It set up a permanent court of arbitration in The Hague and further buttressed its mission by establishing a first Hague convention in the same year, followed in 1907 by a second one. At that second conference, one influential presence was that of the Institut de droit international, founded in 1873, partly in response to Germany’s high-handed annexation of Alsace-Lorraine.21

Thus as Europe drifted towards the abyss of 1914, there was at the same time a growing internationalism aimed at preventing war, or at least its worst excesses, and regulating international affairs. It profited from wealthy donors such as Andrew Carnegie (who footed the bill for the Peace Palace in The Hague, 1907–1913) and Alfred Nobel, who instituted his Peace Prize in 1901. Its first recipients in that year were Henri Dunant and Frédéric Passy, founders of the Red Cross and the arbitration court; in 1904 the Nobel Peace Prize went to the Institut de droit international. An associate of these pacifist individuals and institutions, the activist Bertha von Suttner, won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1905, largely on the strength of her novel Die Waffen nieder!

This budding pacifist internationalism formed part of the utopian–reformist climate that we have encountered as the enabling ambience for the spreading the Arts and Crafts movement (Chapter 10). That climate itself should be recalled to understand the shock that was caused by the outbreak of the 1914 war and especially by the fate of neutral Belgium. Yes, the war may have been greeted by fervently patriotic crowds on the streets of the European capitals, each singing their respective national anthems; but what soon came into view was the conduct of the German troops on their way towards Paris, torching the city of Visé and the Louvain university library and executing Belgian citizens in their hundreds. Tellingly, the wholesale executions of Serbian villagers by Austrian troops attracted comparatively little notice.22 Even though the war had been sparked off in Sarajevo and its conduct in the Balkans was especially murderous, all eyes were on Germany and Belgium. That in itself indicated the importance of publicity and the effectiveness of the aspersions that had been cast upon the German character by French revanchistes in the preceding decades. The discourse of propagandistic denunciation had been prepared ever since 1871 and was primed for deployment. How could Germany pride itself on anything like Kultur if it violated Belgian neutrality, of which it was itself one of the international guarantors, and behaved as barbarously as it did towards the civilian population?Footnote *

Initial reports, bad as they were, were gruesomely exaggerated as they echoed around the outraged media. This was the case on both sides: German justified their retaliatory executions by referring to the sadistic treacherousness of the duplicitous Belgians, women and children not excepted; but setting a medieval university library on fire was definitely not the way to win hearts and minds.

In fact, this war had three fronts: east, west and international public opinion. Germany lost the battle on the third front early on in the war, even though its public intellectuals came to the fore in great numbers. This is how the troops were disposed. Within Germany, there were public lectures and public statements by reputable academics such as Rudolf Eucken, Ernst Haeckel, Friedrich Meinecke, Werner Sombart and Ernst Troeltsch; their lectures came out in collections entitled Deutsche Reden in schwerer Zeit.23 Similarly in France, the Quai d’Orsay (the ministry for foreign affairs) banded leading intellectuals into a committee, led by the highly regarded and fervently nationalist historian Ernest Lavisse, with the aim of directing public opinion through their publications. The Comité Lavisse included Emile Durkheim, Joseph Bédier, Henri Bergson, Ernest Denis and Gustave Lanson. In Britain, a new institution was created, the War Propaganda Bureau; it brought together leading authors to advocate for the British cause in writing.24

In most cases, the discourse generated in the war years was largely concerned with the assertion of the rightfulness of the country’s war aims,Footnote * defensive as they were of course, and the denunciation of the enemy’s pernicious, long-plotted aggression and their soldiers’ savagery. Cases in point (all from 1915) are the collection Qui a voulu la guerre? by Emile Durkheim and Ernest Denis (documents gathered from diplomatic and official sources), Joseph Bédier’s Les crimes allemandes d’après les témoignages allemands (edited from the field diaries of captured or killed German soldiers), and the notorious Bryce Report on Alleged German Outrages, compiled for the British War Propaganda Bureau. These texts were published both for domestic consumption and, on neutral ground such as in the New York Times, with the aim of swaying the sympathies of the United States. Bédier’s book was published in 400,000 copies, and 25,000 copies in English translation were shipped to the US.

German self-justification before the court of international public opinion started immediately after the invason of Belgium with a declaration by Wilhelm II, which, characteristically overstated and grandstanding, demonstrated not Germany’s righteousness but its emperor’s self-righteousness.

Since the foundation of the Reich forty-three years ago, my ancestors and I have done our utmost to preserve peace in the world and in that peace to forcefully promote our development. But there are enemies who begrudge us the fruit of our labour.

We have borne all the open and secret enmity coming from the east, from the west, and from across the sea, aware as we were of our responsibilities and our force. But now we are to be humiliated. We are expected to stand by passively as we watch our foes arm themselves for a treacherous attack, and we are denied the right to support, in steadfast fidelity, our ally [Austria] in its struggle to maintain its position as a major power, and whose humiliation would also destroy our power and our honour.

So let the sword decide. In the midst of peace our foes have assaulted us. To arms, then! Any delay or dithering would be a betrayal of the fatherland.

What is at stake is the existence or annihilation of the Reich that our fathers re-established; the existence or annihilation of German power and the German identity.

We will defend ourselves to the last breath of man and horse. And we will win this struggle, even against a world of foes. Never yet was Germany vanquished if it stood united.25

One month later, in September 1914, as the conduct of the German army had provoked widespread outrage, ninety-three prominent German professors and public intellectuals issued an ‘Appeal to the Civilized World’ (Aufruf an die Kulturwelt). Consisting of six brief paragraphs, each containing a single assertion, it followed the lapidary style of the theses that Martin Luther had nailed to the Wittenberg church doors in 1517; but this erudite subtlety may have been lost on readers abroad. The statement declares that ‘the undersigned representatives of German learning and culture denounce to the civilized world the slanderous lies with which Germany’s enemies have tried to tarnish its just cause in the grievous existential struggle with had been forced upon it’. Then follow the six denials, each paragraph beginning with the large-printed words Es ist nicht wahr, daß …. (‘It is untrue that ….’). In conclusion, the civilized world (Kulturwelt) is once again addressed:

We cannot defuse our enemies’ poisonous mendacious weaponry; we can only proclaim to the world that they bear false witness against us. To you who know us, you who have until now been guardians, together with us, of the most cherished inheritance of humankind, to you we call out: Believe us! Believe, that we will fight this battle to the end as a civilized nation [Kulturvolk], which holds the inheritance of Goethe, Beethoven and Kant as sacred as its hearth and home. To this we sign our names and our honour!26

Many of the signatories are authoritative indeed: eminent writers and artists, prominent scholars from all academic disciplines, including a good few Nobel Prize laureates. Notwithstanding, the overall effect was a tone-deaf rhetorical failure, reminiscent more of Professor Knatschke than of Luther:

It is untrue that our conduct of the war disregards international law … But in the East, the earth is soaked by the blood of women and children butchered by Russian hordes … The claim to defend European civilization is unbecoming for those who have allied themselves with Russians and Serbians and who offer the world the degrading spectacle of turning Mongolians and Negroes loose on the white race.

As Martha Hanna (p. 80) put it, ‘the Manifesto of 93 soon became the most vilified document to come out of Germany in the early war’. A rebuttal by French and British intellectuals soon followed, again marked by recrimination, self-righteousness and prestigious signatories. The names on both documents included the luminaries of the day: on the German side Rudolf Eucken, Ernst Haeckel, Karl Lamprecht, Friedrich Naumann, Max Planck, Wilhelm Röntgen, Wilhelm Windelband and Wilhelm Wundt; on the British side Thomas Hardy, G. O. Trevelyan, Arthur Conan Doyle, Rudyard Kipling, J. M. Barrie and H. G. Wells – they had gathered in the preceding week at a conference organized by the War Propaganda Bureau. In a follow-up British statement, 117 prominent scientists and academics signed as well. And that in turn unleashed the massive Erklärung der Hochschullehrer des Deutschen Reiches, signed by no less than 3,000 academics. Something like an arms race: a brains race.27

Such altercations demonstrate how important the voice of academic scholarship had become as a prestigious support for the state’s war efforts; the argument generally turned around the question how Germany could reconcile its belligerence and militarism with its self-image as the nation of Kultur and earnest sobriety. Outside Germany, such a notion of Kultur was howled down with scorn; as a German loanword in italics, with a hateful Teutonic Knatschke-K belying its Latin derivation, it became a mongrel, an oxymoron, the more so since it was constantly linked to the brutalities (real, exaggerated and imagined) of the German army against their civilian victims. The German scholars, writers, artists and Nobel laureates had hoped to raise their country’s reputation by associating their prestige with its war efforts; in the event, they lowered their own prestige by the association.

In the general discourse of French war justification, we see a remarkable prominence of three alumni of the Ecole normale supérieure, Fustel de Coulanges’s erstwhile workplace now headed by Ernest Lavisse. One of them, Camille Jullian, an ancient historian like Fustel, we shall encounter further on. The other two were Ernest Denis and Emile Durkheim, both members of the Comité Lavisse; they jointly authored Qui a voulu la guerre?, a documentation based on diplomatic and official sources aiming to demonstrate that Germany (despite its protestations that it had been unwillingly forced towards a pre-emptive strike) had been deliberately working towards a premeditated expansionist war.28

That ‘Who started it?’ debate has never quite been laid to rest. The question of Germany’s aggressive or defensive war aims resurfaced in 1961 with Fritz Fischer’s Griff nach der Weltmacht, which itself has continued to feed historiographical controversies up to and including Perry Anderson’s Disputing Disaster (2024). Political and diplomatic historians who wish to derogate the blame laid exclusively at Germany’s door in 1918 (e.g. Christopher Clark’s authoritative The Sleepwalkers, Reference Clark2014) tend to discredit evidence of German hawkishness pre-1914, as in the 1907 memorandum by the British diplomat Eyre Crowe warning against appeasement. And, archive-based as their work is, it tends to downplay the importance of published sources (e.g. the tract Deutschland und der nächste Krieg by general Friedrich von Bernhardi, 1912) and of press campaigns.29 But public opinion and press campaigns were by no means inconsequential, and they should be factored into an analysis of the culture of belligerence that was rife in 1914. Public opinion, especially of the hawkish kind, was even more influential in 1914 than it had been in 1870;30 and the years leading up to 1914 still echoed with the memories of 1871. To ignore that fact, or to argue it away, is as one-sided as to accept the propaganda at face value.

A genre of ‘invasion novels’ or ‘future war novels’ had emerged in English literature immediately after the German victory over France in 1871: in that year The Battle of Dorking evoked a German landing in England. Notable examples of the genre were The Riddle of the Sands (1903), When William Came: A Study of London under the Hohenzollerns (1913) and John Buchan’s The Thirty-Nine Steps (1915). In 1897, William Le Queux’s The Great War in England had still imagined the invaders to be the accustomed enemies, France and Russia; but ten years later, in Le Queux’s The Invasion of 1910 (1906), the invading enemy had, as per the conventions of the genre, become Germany. That book came out in a great media blitz, serialized in the Daily Mail with newspaper vendors dressed up as Prussian soldiers displaying maps of their armies’ progress. The book edition sold a million copies.

That was the public sounding board to Eyre Crowe’s diplomatic memorandum of 1907. How intricately the media, fiction and diplomacy were linked is indicated by the fact that Le Queux’s book was a fictionalized platform for the war alarmism of Field Marshal Roberts, former commander-in-Chief, whose anti-German speeches of the period appeared in 1907 as A Nation in Arms.31 Indeed the novels created a veritable invasion scare in England, similar to the Napoleonic one of 1803. Matters were stoked up further by Le Queux’s sequel, Spies of the Kaiser: Plotting the Downfall of England (1909). The resulting moral panic caused members of the public to write to Le Queux about suspected sightings; these communications were placed at the disposal of the nascent bureau of military intelligence. Indeed, one historian suggests that Le Queux himself believed in the veracity of the alarmist tales he put before the public. War propaganda thus preceded the outbreak of hostilities by a good few years: historical memories of 1870 (in France and Germany) and imaginative fiction (in England) primed the public for 1914.

Another point of continuity from 1871 to 1914 was the question of the Rhine and Alsace-Lorraine. Camille Jullian, like Fustel de Coulanges an archaeologist and an École normale supérieure alumnus, wrote a number of firebrand pamphlets with juicy titles such as Pas de paix avec Hohenzollern! But his most remarkable contribution was a veritable counterpiece to Arndt’s old Rhine tract of 1813. It was called Le Rhin gaulois (1915) and aimed to demonstrate that since prehistoric and classical times, the population on the banks of that river had been Celtic. He relied heavily on Fustel’s view of history to make that case. Yes, even after the incursions of the Germanic tribes, the new settlers adopted the Celtic attitudes of the earlier inhabitants into which they were absorbed and developed an essentially Celtic-rooted, Gaulish relationship with that river, whose Celtic character thus remained unbroken.

Jullian’s efforts were amplified by a weightier study published in two volumes in 1916–1917: Ernest Babelon’s Le Rhin dans l’histoire, which surveyed the long history from Gaulish–Germanic conflicts to French–German ones. The author was the leading numismatist of his generation and a professor at the Collège de France. Both he and Jullian were part of the Comité d’études, consisting of prominent historians, geographers and archaeologists, which had been set up in the closing years of the war to prepare the government’s claims to a return of Alsace and Lorraine. Among its members we encounter, unsurprisingly, various members of the Comité Lavisse. The Comité d’études published L’Alsace-Lorraine et la frontière du nord-est in 1918; it became an important document during the Paris peace negotiations of 1918–1919, in particular for the annexation of the Saarland. Clémenceau abandoned the principle of self-determination so passionately advanced by Fustel and Renan and applied by the League of Nations in all other contested borderlands in Europe; in 1918–1919 he pushed through a straightforward and immediate French reannexation of Alsace-Lorraine without bothering with a plebiscite.

Emile Durkheim’s propaganda efforts are of particular interest. He wrote a long tract denouncing Treitschke and, through Treitschke, a ‘German mentality’: L’Allemagne au-dessus de tout: La mentalité allemande et la guerre (1915). Durkheim constantly dovetails Treitschke’s name (redolent of the 1870–1871 confrontation) with that of the notorious warmongering General Friedrich von Bernhardi. His book Deutschland und der nächste Krieg is presented by Durkheim as the logical military application of Treitschke’s cultural and moral nostrums. In twinning Treitschke and Bernhardi as the ‘brain and muscle’ of Prussian supremacism, Durkheim clearly betrays his propagandist intent, invoking the ingrained trope of the hateful Knatschke-cum-Junker duo.

Durkheim’s tract, obvious war propaganda, is driven by anti-German animus and reifies the ‘mentality’ it attacks. But like Renan’s Qu’est-ce qu’une nation?, the argument also rises above its immediate propagandistic pugilism and offers, even beyond its overt anti-German intent, an interesting and insightful analysis of a more general principle: that of a ‘might makes right’ ethics of the national interest, a self-serving moral exceptionalism in international relations. We may call it by a name that Durkheim had coined in another context: anomie. ‘Anomie’ can be translated as the more current term ‘narcissism’ – not just as exaggerated, boastful vanity, but in the pathological sense. As a pathological disorder, narcissism involves self-aggrandizement, a lack of empathy, erratic wilfulness, the inability to admit the relativity of one’s own point of view, the self-exemption from the moral standards that one holds up to the rest of the world. All this tallies with what Durkheim called anomie.

Durkheim had identified anomie in certain individuals deviating from general moral normativity. As Dominick LaCapra Reference LaCapra1972 has pointed out, that typology of deviant self-righteousness also applies to unilateralist or imperialist states that consider their own national interests to be categorically rightful. Anomie stands for an erosion (linked to social modernity) of one’s embeddedness in moral obligations and its replacement by a notion of volition. Durkheim had developed the concept in the 1890s, in his work on labour division and on suicide; it also informed, tacitly, his wartime critique of a specifically ‘German’ moralistic egotism and self-serving unilateralism. Anomie is what informs that line in Felix Dahn’s motto for the Alldeutscher Verband: ‘a nation’s highest good is its right’ (Das höchste Gut des Volkes ist sein Recht).

Durkheim’s ‘down with the beastly Germans’ reflex is of course mere wartime ire; but his diagnosis of anomie as a facilitator of self-righteous unilateralism is more suggestive. In the course of the nineteenth century, increasing importance is given to the notion of will as a moral agency in German thought. Goethe had already juxtaposed sollen (‘duty’, in the classical tragedy of impossible moral obligation) with wollen (‘will’, in the modern tragedy of impossible self-realization). The concept’s trajectory thenceforth is suggestive: from Schopenhauer’s Die Welt als Wille und Vorstellung (1819) by way of Nietzsche’s Wille zur Macht (posthumously published in problematic editions, 1901 and 1906, but announced in a nutshell in Also Sprach Zarathustra) to Leni Riefenstahl’s film Triumph des Willens (1935). In the run-up to the charismatic leadership so lavishly glorified in Riefenstahl’s film, the celebration of willpower is an unmistakable element. Nor is this identification of anomie, as ‘Will makes Right’, merely an argument of convenience for bashing the Germans. Justifying ruthless aggression from the categorical imperatives of the nation’s interest and ‘military necessity’ went against the fledgling idea of an international legal order and has remained an identifying characteristic of unilateralist states in general. Anomie can be applied to cases such as Putin’s Russia (in 2020 Ukraine) or the ‘Dahiya’ use of disproportionate force by Likud-governed Israel (in various conflicts since 2006); I will return to it in the conclusion of this book.32

National Identity at Stake

Thus the intellectuals did their patriotic duty in propaganda battles and provided diplomacy with ammunition. The result of their interventions was also that the war was lifted from a conflict of state interests to a confrontation between incompatible nations, each with their specific characters and temperaments. Character assassination of the enemy has, of course, been a tool of warfare since warfare began; what was new was the fact that the notion of ‘national character’ had in the preceding century become a thing that philologists, historians, sociologists and ethnographers felt they could discuss with scientific authority; hence their new role as war propagandists.33

Poets and versifiers continued to do their patriotic bit as of old. The most interesting altercations took place between Germany and ‘England’ (that cultural name was habitually used, especially in Germany, to describe the British Empire); it is ‘England’ that draws the indignation of German apologists, possibly because they had believed in a Germanic–Anglo-Saxon kinship until recently, such as had been experienced in the days of Carlyle and Prince Albert. But Carlyle and Prince Albert were dead. Carlyle’s intellectual successor had been Matthew Arnold, who under Renan’s influence and with a Cornish mother saw himself as half-Celtic; and the Prince of Wales had married a Danish princess, Alexandra, who was resentfully mindful of the Prussian attack on her country in 1864. After he had ditched Bismarck, Wilhelm II had given free rein to grandiose ambitions for Germany to become a colonial world power with a navy rivalling the British one; that had driven British public opinion away from their German cousin. Britain’s Entente Cordiale with France had been concluded in 1904, and the British public was exposed, as described earlier in the chapter, to a steady diet of novels warning of a future German invasion. The sudden swerve of British public opinion and foreign policy away from Germany and towards France, and increasingly belligerent, caught German commentators unaware, and this sudden unpleasant surprise was what most agitated their pens.34

The most extreme example is probably the ‘Song of Hatred against England’ by Ernst Lissauer. It ends as follows:

Strong stuff, but by no means unrepresentative. The Haßgesang was widely popular; printed as a pamphlet, it was distributed among the troops in the field. The poet (who also coined the slogan ‘Gott Strafe England’ – ‘God punish England’ – which went viral) was given Prussian and Bavarian decorations. But while Lissauer’s vehemence may have gone down well at home, internationally (the English translation quoted here, by Barbara Henderson, was published in the New York Times in October 1915) it served only to demonstrate an embarrassing furor teutonicus. Failing to woo international readers, Lissauer left the moral high ground wide open. The one to take it was the venerable Thomas Hardy, august novelist from the previous century, who in his old age was also called to serve the War Propaganda Bureau. This is how he replied:

And so the mutual sniping at each others’ moral character formed part of the hostilities, with the German side from the outset fatally caught in a cleft stick that was partly of its own making. The harsh and ruthless pursuit of war aims meant that ‘military necessity’ ran afoul of an international climate that in the previous decade had come to place its hope in the pacifist and humane restraints of the Geneva Conferences and the court of arbitration. The apologia that this war had been forced upon a peaceful Germany, which had no other choice than to defend itself, rang hollow in light of the fact that this self-defence was conducted on foreign soil, and also in the light of the ambitious, expansionist war aims that were trumpeted about domestically in triumphalist German media, as if no one else would notice them. The memories of 1870–1871 could not but colour what was universally seen as its 1914 rematch. And finally, there was the toxic ethnotypical frame that had been devised for the German character by French intellectuals since 1871: all too easily could this war be seen as motivated by a mentalité de boche, combining egotistal priggishness with a ruthless disregard for the rights and even the viewpoints of others. All that made the propaganda war a lost cause from the outset. Germany fought that war with obsolete weaponry – indeed, it was fighting, as the saying has it, the previous war: Germany’s self-definition as a Kulturnation was, by 1914, as outmoded as its sense of kinship with England.

The net result of this cultural warfare was to bind intellectuals, as leaders of public opinion, to the national interest. Also, the World War placed the nation, its personality and characteristics, under the aegis of the state; the war as fought on the cultural propaganda front required the robust vindication of the nation’s character amidst other nations. The war gave the state the supreme ownership of the nation’s sense of identity and a mandate to assert it in the wider world. The end result of that process can be seen in the famous opening paragraph of Charles De Gaulle’s memoirs, one World War later, in which he expounds what France (a transcendent France, Michelet-style) means to him:

All my life I have had a specific idea of what France stands for [une certaine idée de la France]. That feeling inspires me as much as my critical judgement. Emotionally I automatically imagine France, like a fairy-tale princess or frescoed Madonna, as being dedicated to a high and exceptional calling. I have the distinct impression that Providence has created her for exemplary achievements or miseries. If occasionally her deeds and experiences should, even so, be marked by mediocrity, this strikes me as an absurd anomaly, due to the shortcomings of Frenchmen, not to the spirit of the fatherland. But even the factual side of my personality convinces me that France is only really herself when she occupies the first rank: that only the greatest enterprises are capable of outweighing the centrifugal ferment which her people carry within themselves; that our country, being as is it – amidst others, being as they are – must, on pains of mortal peril, aim high and stand tall. In short, as I see it, France cannot be France without grandeur.37

In this respect (entrusting the state with the ownership and guardianship of the nation’s identity) the propaganda of 1914–1918 effected the same thing in wartime that the world fairs had prepared in peacetime. States were now, automatically, about nationality as much as they were about taxation and governance. We may expand Charles Tilly’s dictum slightly: States made war, and the war made states national.38

Dulce et Decorum

It was, automatically, the state that took charge of its wartime bereavements, acting as chief mourner. The need to keep up morale during the hostilities prevented too much hand-wringing while the war was still going on, but a considerable amount of cultural bandwidth was taken up by public commemorations of the war dead after 1918.39 The state took charge of the nation’s pomp and circumstance (to recall Elgar’s tune of ‘Land of Hope and Glory’). France’s Bastille Day, with its huge military parade between the Arc de Triomphe and the Place de la Concorde, had been fixed as a fête nationale in 1880 (the senator in charge of that measure had been the Gaul-obsessed Romantic historian Henri Martin, founding member of the Ligue des patriotes), and in 1894 a Fête nationale de Jeanne d’Arc et du patriotisme was first mooted, to be officially established in 1920 on the official proposal of the Action française leader Maurice Barrès. To this nineteenth-century legacy of state-curated triumphalist remembrance was now added the modality of collective grief. Unknown soldiers were retrieved from dispersed war graves and solemnly reinterred, with eternal flames, under the Arc de Triomphe and in the Vittorio Emmanuele monument in Rome. War cemeteries (a twentieth-century phenomenon in Europe) were arranged from the Alps to Flanders to give an honourable resting place to the millions of casualties. Every village square in France, every parish cemetery in Germany and Austria, every English cathedral has its monument honouring the casualties from the local community. No previous war had had this effect of sublimating grievous loss into a nationwide, all-pervasive public culture of decorous mourning. Decorum: the solemn respect rendered to the dead was linked to the notion that their deaths had been a sacrifice for the fatherland and as such were something heroic and dignified, the fulfilment of a high duty. As of 1915, ‘Mort pour la France’ became an officially regulated honorific mention in a person’s état civil, like an academic degree or a title in the nobility; it was appended to the name so distinguished whenever that name was mentioned, and the underage children of someone mort pour la France enjoyed some state patronage as ‘wards of the nation’ (pupilles de la nation).

Wards of the nation: that word could not have been used thus in previous centuries. Despite the lofty sentiments in Henry V’s ‘Band of brothers’ speech (‘For he to-day that sheds his blood with me shall be my brother; be he ne’er so vile, this day shall gentle his condition’), public monuments for fallen soldiers had previously been reserved for commanding field officers; the rank and file were at best honoured collectively, as regiments. Personal military distinctions such as the Médaille militaire and the Victoria Cross (both established during the Crimean War) made glory and social prestige newly available for enlisted men, placing rank and file so decorated at eye level with commanding officers; hence, perhaps, the often-heard saying that the military experience of war acts as a great blender for distinctions within the nation, throwing together people from different regions and walks of life. Jean Renoir’s war film La Grande Illusion (1937) represents the French soldiery as consisting of carefully chosen representatives of the full palette of French society (as in his La Marseillaise of the following year). The aristocratic understanding and well-bred courtesy between two nobly born officers (the German Rauffenstein and the French Boïeldieu) is nullified by the latter’s national bond with his French fellow captives: the lieutenants Maréchal (working class) and Rosenthal (a banker’s son of Jewish descent). That is what ‘nation’ comes to mean as reforged in the crucible of war: society at large unified, beyond class and region of origin, by the experience and memory of shared glory and suffering – for so we may summarize Renan.40

This usage, with these connotations, may be specific to the French word nation and the French history of its usage. Much as it would be difficult to think of a similar usage pre-1800, so it would be difficult to think of an analogous usage in German. The word die Nation had fallen into disuse after Fichte (although derivations such as national and Nationalität remained current) and was by and large replaced by its near-synonym Volk. But even the thought experiment of trying to conceive of war orphans to be adopted as Schützlinge des Volkes drives home the very different connotations, with Volk connoting the specificity of class or ethnicity rather than the all-inclusive societal fraternity that la nation can evoke; one would more easily conceive of such patronage being extended on behalf of the Vaterland as a moral collective.

Whatever the semantic minutiae, it was the nation or the fatherland that was invoked as the agency that could idealize and sublimate brutal carnage into something that had, in the Latin root sense of the word, decorum. We know with what bitter sarcasm Wilfred Owen cited Horace’s Dulce et decorum est pro patria mori when evoking the death-throes of someone dying in a mustard-gas attack; or, in ‘Anthem for a Doomed Youth’, harshly juxtaposing the decorous rituals of a funeral service with the bestial experiences of ‘those who die as cattle’. That traumatized perspective has come to dominate our view of the Great War, and even of warfare as such. Even so, we must not underestimate the consolation that this decorum, and all the pomp and circumstance of commemorative acts, offered to the bereaved families and surviving comrades. We may recall the palliative of the Chanson de Roland for 1870s France (‘that douce France for which one could already die such a good death at Roncesvalles’). Their palliative power rendered the Parry/Elgar setting of ‘Jerusalem’ and the Holst-scored ‘I Vow to Thee, My Country’ cherished classics in the public repertoire. They gained their initial popularity during World War I commemorations, but they have featured at royal weddings and the funeral of Margaret Thatcher. The ambivalence of wartime condolence and a generalized cult of the nation is pre-inscribed; we have seen the fey national fanaticism coupled with the stately, pensive melody of Holst’s ‘Thaxted’ hymn. In Laurence Binyon’s ‘For the Fallen’ what we recall is mainly the high-minded stanza that begins ‘They shall not grow old’, but we overlook that the poem as a whole begins ‘With proud thanksgiving, a mother for her children/England mourns for her dead across the sea. Flesh of her flesh they were, spirit of her spirit’ – nationality monopolizing the sum total of what the war dead were and stood for.

Decorum cuts both ways. The state can bestow pomp and circumstance, ritual, dignity and decorum on acts of collective mourning, and in return can draw credit from that mourning as the place to turn to when the people are in need of succour. The importance of the function of national decorum can be gauged from the situations where it is in short supply, as tends to be the case when wars are, embarrassingly, lost. In Weimar Germany, the bitterness of war memories was unalleviated, burdened by the ‘stab in the back’ legend peddled by a self-serving Hindenburg (Reference Hindenburg1920) and expressed in the traumatic art of Otto Dix and Erich Maria Remarque. An analogue of sorts is noticeable in the fraught aftermath of the Algerian war of liberation in France (which was not even officially classified as a ‘war’ until 1999). In the US, Sylvester Stallone’s Rambo: First Blood film (1982) thematizes the traumas of an awkwardly non-remembranced Vietnam war. The manic killing spree that Rambo belatedly unleashes on the Vietnamese in First Blood Part II (1985) shows the inability to come to terms with defeat (‘Do we get to win this time?’) and seeks its blood-soaked catharsis in claiming a reciprocity between the soldier’s love of country and the country’s decorous gratitude. ‘I want what … every other guy who came over here and spilt his guts and gave everything he had wants: for our country to love us as much as we love it. That’s what I want.’41 Rambo: First Blood was filmed during the Reagan years, while the Thatcherite media in Britain were whipping up jingoistic fervour over the Falkands War. Those years mark an upsurge of strident, chauvinistic nationalism in Hollywood cinema, which will be addressed more closely in Chapter 12. Rambo’s traumatized eagerness to re-engage in battle during the post-Vietnam ‘culture of defeat’ reminds one of the refusal by German war veterans – who organized into so-called Freikorps militias – to lay down their arms in 1919, and indeed of the many post-Armistice hostilities that continued to rage around Europe after 1918. It also suggests an interesting side aspect of the ‘culture of defeat’ as analysed by Schivelbusch: the post-traumatic embitterment disorder that follows lost wars is exacerbated by a perceived lack of proper, official decorum with regard to the sufferings, losses and casualties sustained.42

What can we say of the overall impact of the Great War on the cultural history of nationalism in Europe? As a result of the all-devouring belligerence, the culture and cultivation of national identity was rendered both more and less visible. On the one hand, there was the ultrapolitical stridency of war propaganda, the bitter, mortal national enmity; on the other hand, there was the unpolitical nation as a comfort zone, serene even in its grief, a beleaguered haven of domesticity – the things that soldiers in the trenches pined for; the green fields and unspoilt countryside of the home country, the tender, affective and, yes, peaceful bonds of familial home life and community. Then again, there was the hard-bitten rejection of all that sentimentality, an anti-idyllic and anti-nostalgic look at life. That fed the sensibility of modernist avant-gardism (in the realm of culture), technocratic scientism (in knowledge production) and revolutionary ideologies, mass movements and personality-cult leaders (in politics).

What survived the Great War was the ingrained assumption, both as a political doctrine and as an unpolitical maxim, that the cultural identity of the nation and the political sovereignty of the state are two sides of the same coin. That dogma is what Romantic nationalism has bequeathed to us even in this twenty-first century. That, and the anachronistic belief that the nation, as a permanent, tranquil essence, transcends the turbulent vicissitudes of history.