When President Jimmy Carter greeted Deng Xiaoping at the White House during the latter’s historic visit to the United States in January 1979, he shook hands with Deng and said to the Chinese vice premier with a smile, “we almost met before.”1 In April 1949, Carter had first landed in China as a young naval officer serving on a submarine visiting Qingdao, while Deng was leading a massive force of the People’s Liberation Army in the decisive campaign of crossing the Yangzi River and capturing the Nationalist capital. By early June, the last American marine had evacuated from Qingdao under siege, as the surrounding Communist forces marched into the city unopposed – just four months before the founding of the People’s Republic of China. This was truly the end of an era, to put it mildly.

Decades later, President Carter told the story not to lament the fall of China, but to celebrate the beginning of a new relationship. He had since repeatedly stressed a personal connection with China and his “love for the Chinese people.” Growing up a Southern Baptist from Plains, Georgia, the seven-year-old farm boy received from his seafaring uncle, who was in the US Navy, a special souvenir – a delicate model of a wooden Chinese junk, which Carter kept in his boyhood home for decades. When he turned ten or twelve years old, his number one hero in the world was Lottie Moon, a Baptist missionary who had devoted her life to China. Finally in 1949, when he was in the navy, Carter toured the same seaports his uncle had visited – Hong Kong, Shanghai, and Qingdao – and was “intrigued with the people of China.”2

We do not know how much his involvement with China shaped the future American president’s view of the country, and it would be a stretch to connect such familiarity to the normalization of bilateral relations under his watch in any tangible ways. Nevertheless, Carter’s personal experience was part of the long history of Chinese-US relations since the eighteenth century, what many Americans saw as a special bond forged by generations of missionaries, traders, journalists, politicians, travelers, and soldiers.3 Notably, this experience was shared to highlight the “people-to-people diplomacy” that Carter famously championed during and after his presidency. In 2011, when attending a ceremony to celebrate the fortieth anniversary of Ping-Pong Diplomacy in the Great Hall of the People in Beijing with Vice President Xi Jinping, Carter restated: “It was that breakthrough just with ping-pong players – that is people-to-people – that was really more important than the decisions of political leaders. And I think that is a stability that is going to prevail in the future.”4

In many ways, US servicemen in China, which an official army guide called “ambassador[s] of the American people to the Chinese people,” formed a direct force of grassroots engagement in the aftermath of WWII.5 Their quotidian interactions with local civilians from all walks of life embodied a type of informal diplomacy, which played a pivotal role in Sino-US relations during a defining historical moment. These exchanges affected the political dynamics during the Chinese civil war and shaped the sociocultural identities of both sides. The micropolitics of the everyday provided a unique lens through which to better understand the so-called loss of China, leaving behind lasting legacies that remain to be recovered and reevaluated.

A New Script for Anti-Americanism: Everyday Abuse and Resistance

Since the reform movement of 1978, Chinese historiography of WWII has experienced some major changes, especially in reevaluating the Nationalists’ contribution to the war effort and the United States’ assistance.6 But discussions of the postwar period between 1945 and 1949 remain fixated on the civil war’s outcome. This era is widely considered a pivotal juncture in Sino-US relations, marking the beginning of a profound divergence between the two countries during the Cold War. Yet there is a lack of critical study of the American military presence beyond operational levels. Dominant historiographies, from both the Communist and Nationalist sides, have reduced the chaotic and volatile experiences of encounters to a tidy, sequenced chord concerning national destiny – China’s victory over Japan and the triumph of the Communist Party – while disagreeing on whether this occurred despite American support for the Nationalists or because of its lack. Following the end of WWII, both parties sought to capitalize on the prevailing nationalist sentiment and heightened patriotism. The Nationalist Government faced a political quandary: It needed to promote nationalism while also maintaining rapport with the United States. Consequently, it chose to downplay Chinese grievances against GI misconduct, dismissing these incidents as isolated accidents or merely legal matters. This strategy backfired when the CCP seized upon these grievances, launching a powerful propaganda campaign that recast the narrative of anti-American imperialism in terms of everyday brutality. They focused on emotionally charged accounts of the violence US forces perpetrated on Chinese civilians, which resonated deeply with the populace. This incisive propaganda undermined the legitimacy and credibility of the Nationalist leadership. Eventually, the Communists emerged triumphant in this critical battle for public opinion and popular support, alongside the military front.

This American occupation has left behind a toxic legacy that continues to be exploited in Chinese nationalist politics. There were previous anti-American demonstrations. But the late 1940s movement introduced new prototypes and powerful imagery that forged an emotional bond among supporters that transcended socioeconomic, political, and geographical boundaries. As discussed in the book, the Communists developed an effective formula that profiled American racism, sexual aggression, and everyday abuse to denounce American imperialism and encroachment on China’s sovereignty. The portrayal of ordinary victims, featuring rickshaw pullers, women, and children being abused or killed by American GIs, evoked the strongest sentiments in the Chinese psyche, especially during times of tension.7 Sensitive sociocultural issues surrounding race and sex became the foundation for popular anti-American nationalism, providing insight into why such a narrative remains compelling long after the US military presence ended in China.

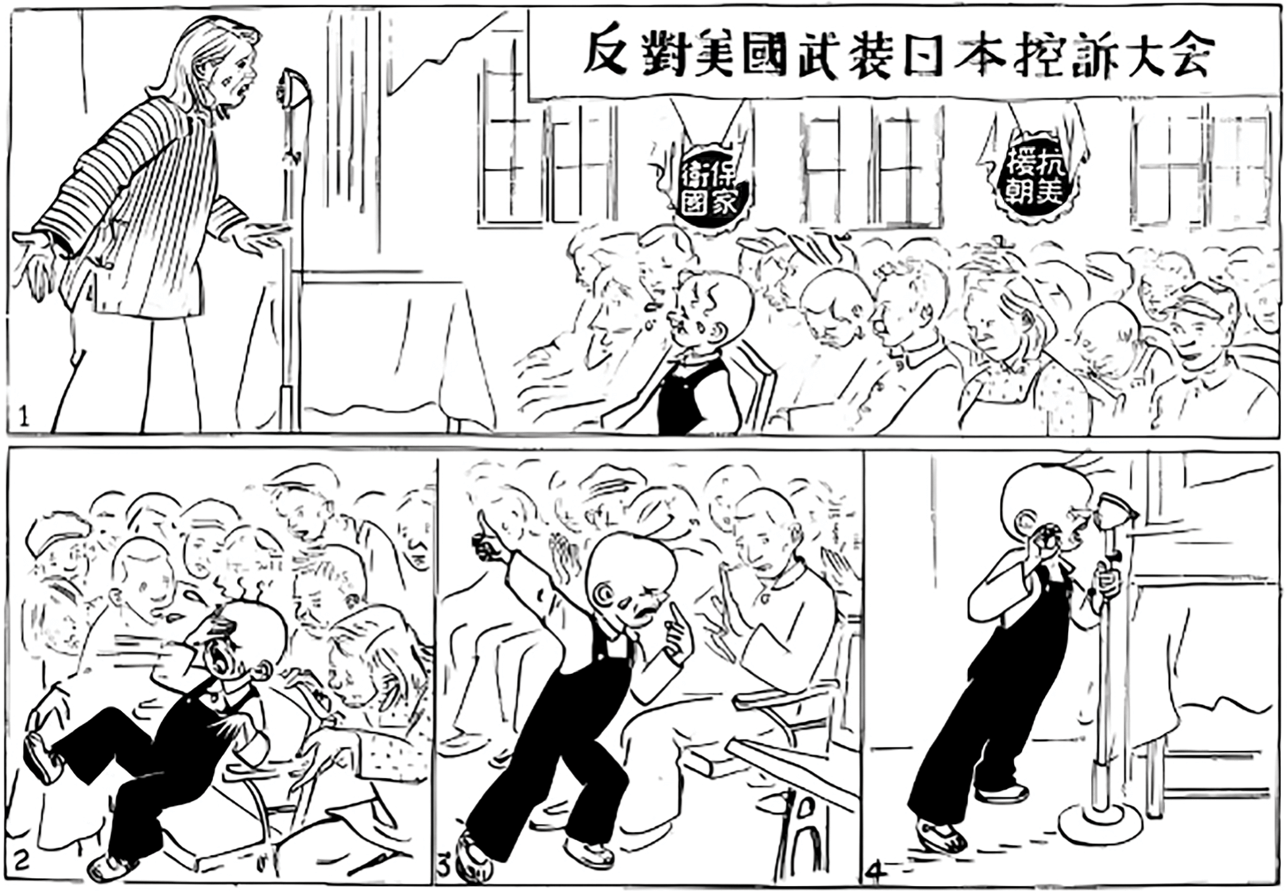

Upon entering the Korean War, the CCP organized another fierce political campaign for mass mobilization against American imperialists. There is a direct link between the upgraded Korean War campaign and the Anti-American Brutality movement several years earlier. First, the new propaganda war employed similar techniques of mass rallying, petitioning, parading, and performing on the street. Wall posters, cartoons, and editorials appeared on college campuses, in the streets, and in the countryside. More importantly, the mass campaign directly inherited the themes of “‘beastly’ behavior of U.S. servicemen in China, the unholy alliance between the imperialist America and the Chiang Kai-shek regime, and the American ‘rearming’ of Japan.”8 Urging the public to hate (choushi), despise (bishi), and disdain (mieshi) US imperialism, propaganda materials republished or recycled materials from previous literature of the late 1940s, refreshing people’s memories or educating them on American atrocities against the Chinese people.9

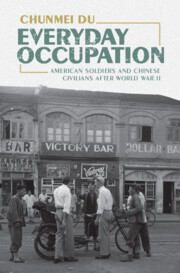

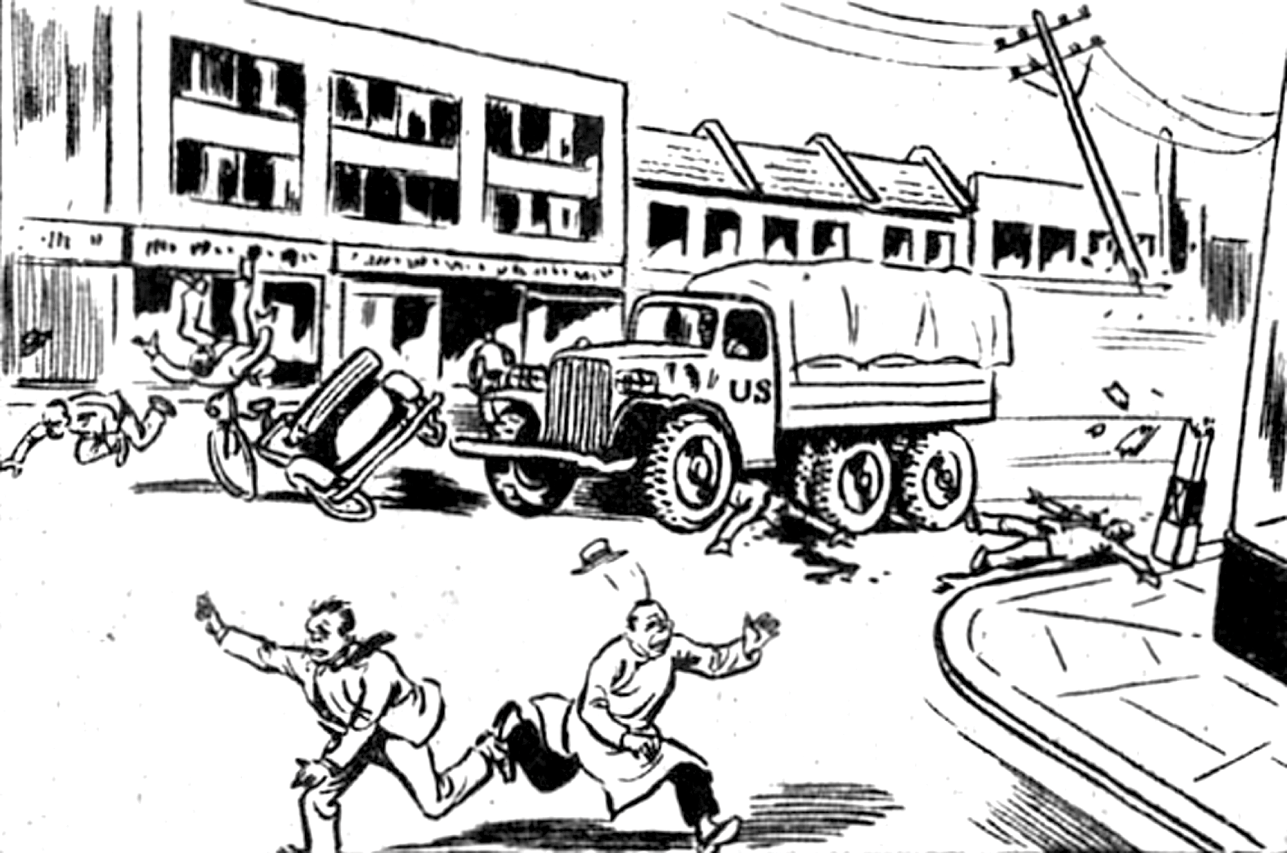

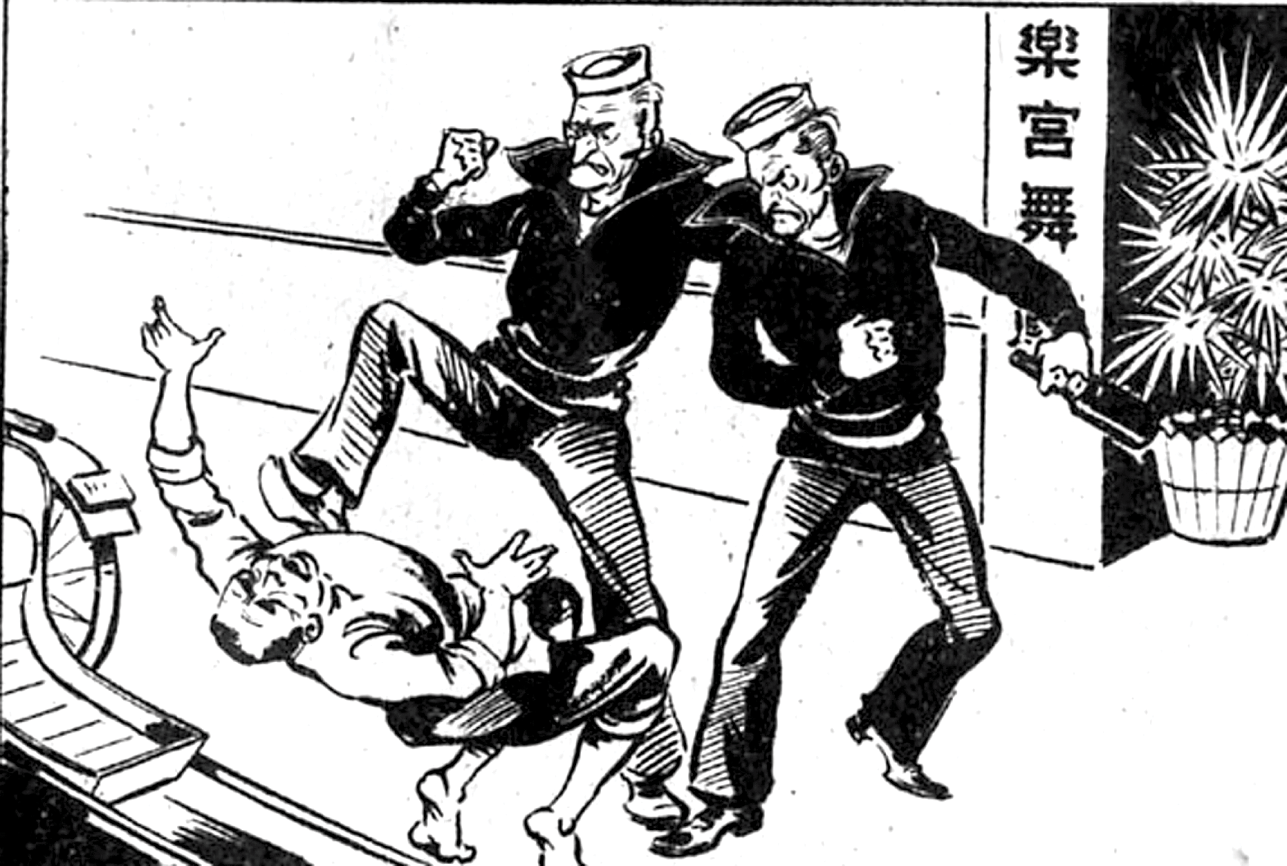

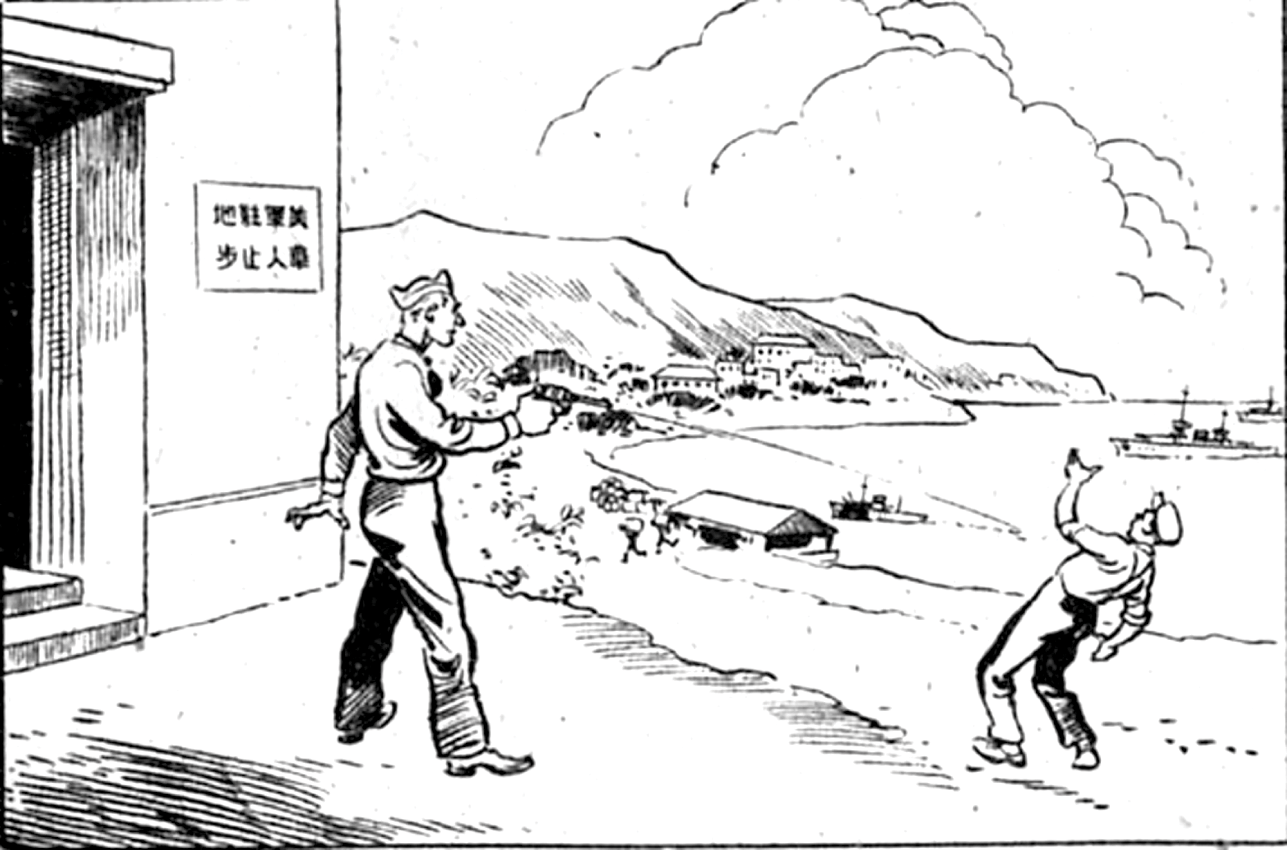

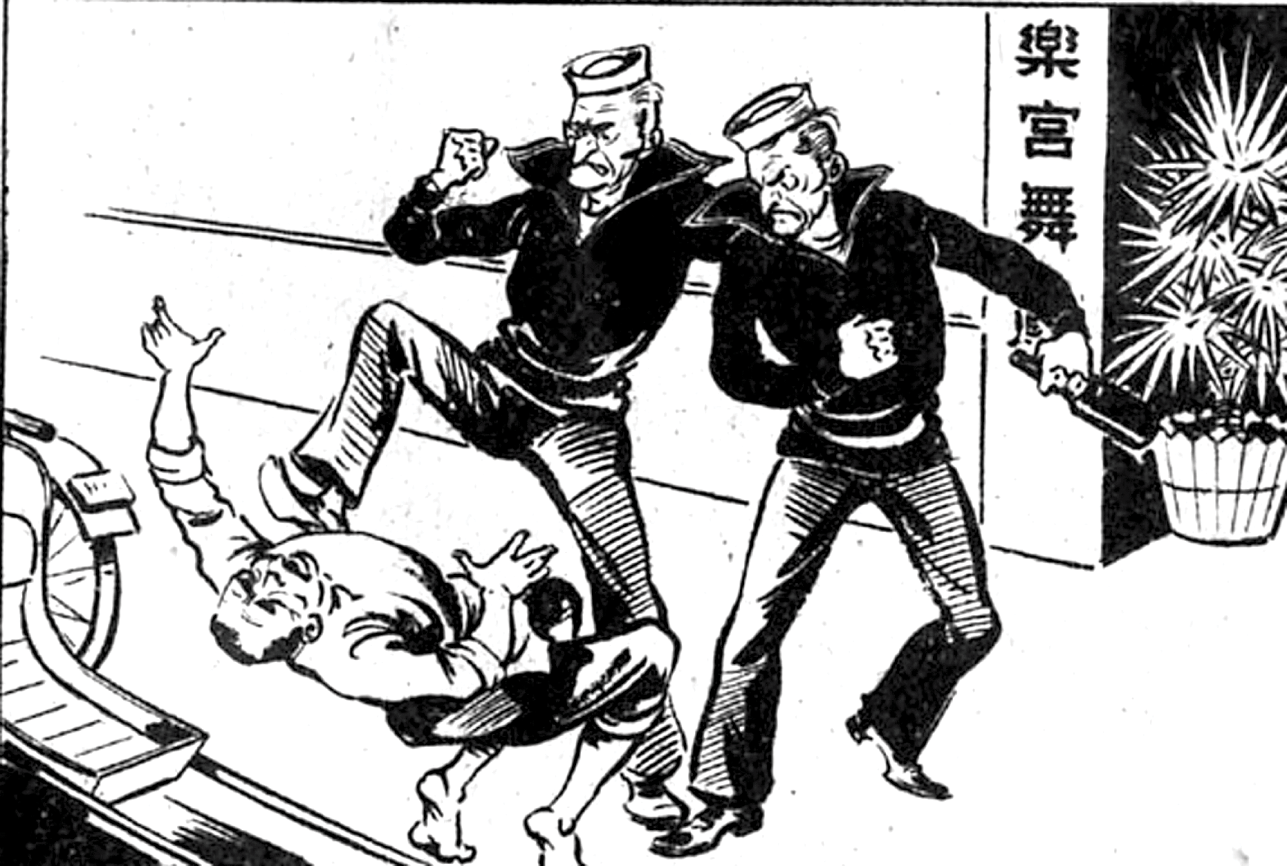

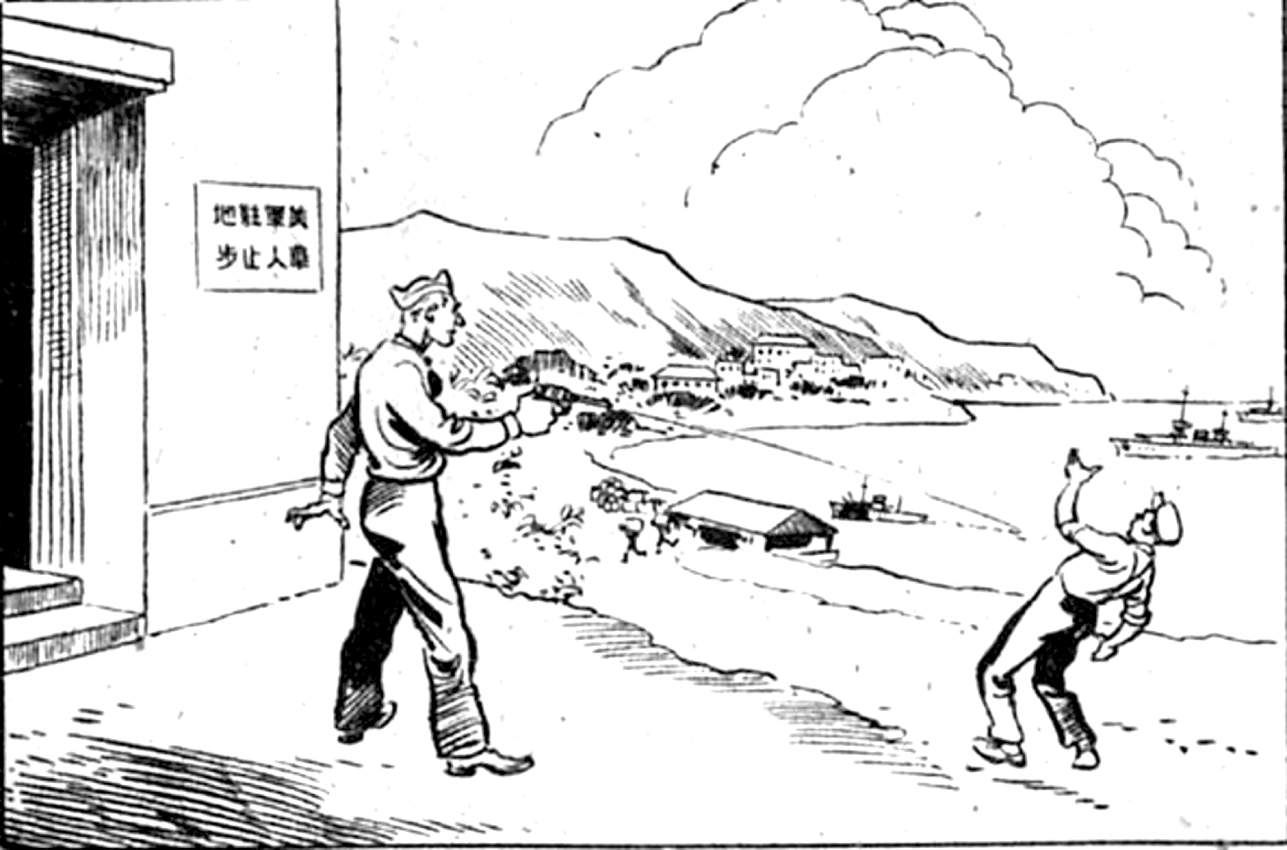

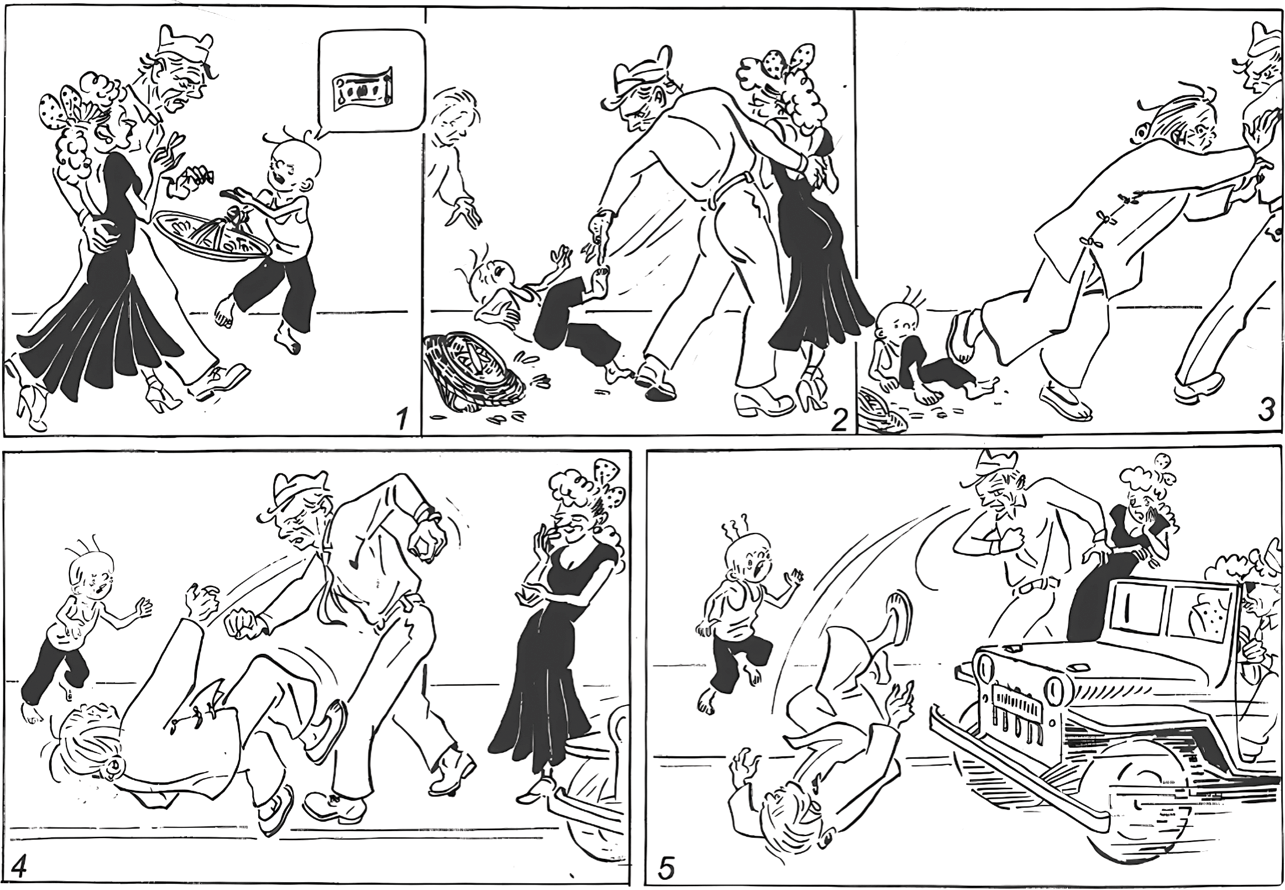

Even by 1950, Chinese animosity toward the United States was not as intense as the Communist Party had hoped, hampering its efforts to mobilize the public for a fierce war to “Resist America and Assist Korea.” In its mass propaganda initiatives, the Party tried various affective strategies and found that grassroots audiences responded most strongly to accounts of the harms inflicted by the United States upon the Chinese people, as well as to depictions of anti-Chinese discrimination.10 Visual materials proved particularly effective, such as “Unsavory Images of American Troops in China” that featured the everyday brutality inflicted upon ordinary citizens. Some visuals reproduced prominent past incidents to evoke a sense of reality and authenticity, including deadly encounters with American military vehicles on the street, the killing of Shanghai rickshaw puller Zang Yaocheng, the rape of Shen Chong in Beijing, and the shooting of a Qingdao workman near a wharf by American guards (see Figures E.1–E.4). Other visuals recast iconic fictional characters in fresh roles to align with the Party’s new historical agenda.

Figure E.1 Illustration of an American military truck rampaging down the street, killing innocent people, part of the “Brutalities of American Troops in China” series, drawn by Ding Hao, 1951.

Figure E.2 Illustration of two drunk American sailors assaulting a rickshaw puller outside a nightclub, part of the “Brutalities of American Troops in China” series, drawn by Ding Hao, 1951.

Figure E.3 Illustration of the rape of a Chinese woman by an American soldier, with a Nationalist official bowing to the American authority who exonerates him, part of the “Brutalities of American Troops in China” series, drawn by Ding Hao, 1951.

Figure E.3Long description

In the background, a recollective image shows a uniformed U.S. serviceman forcing himself upon a Chinese woman in Qipao.

Figure E.4 Illustration of a Chinese workman shot by an American guard outside a military compound, part of the “Brutalities of American Troops in China” series, drawn by Ding Hao, 1951.

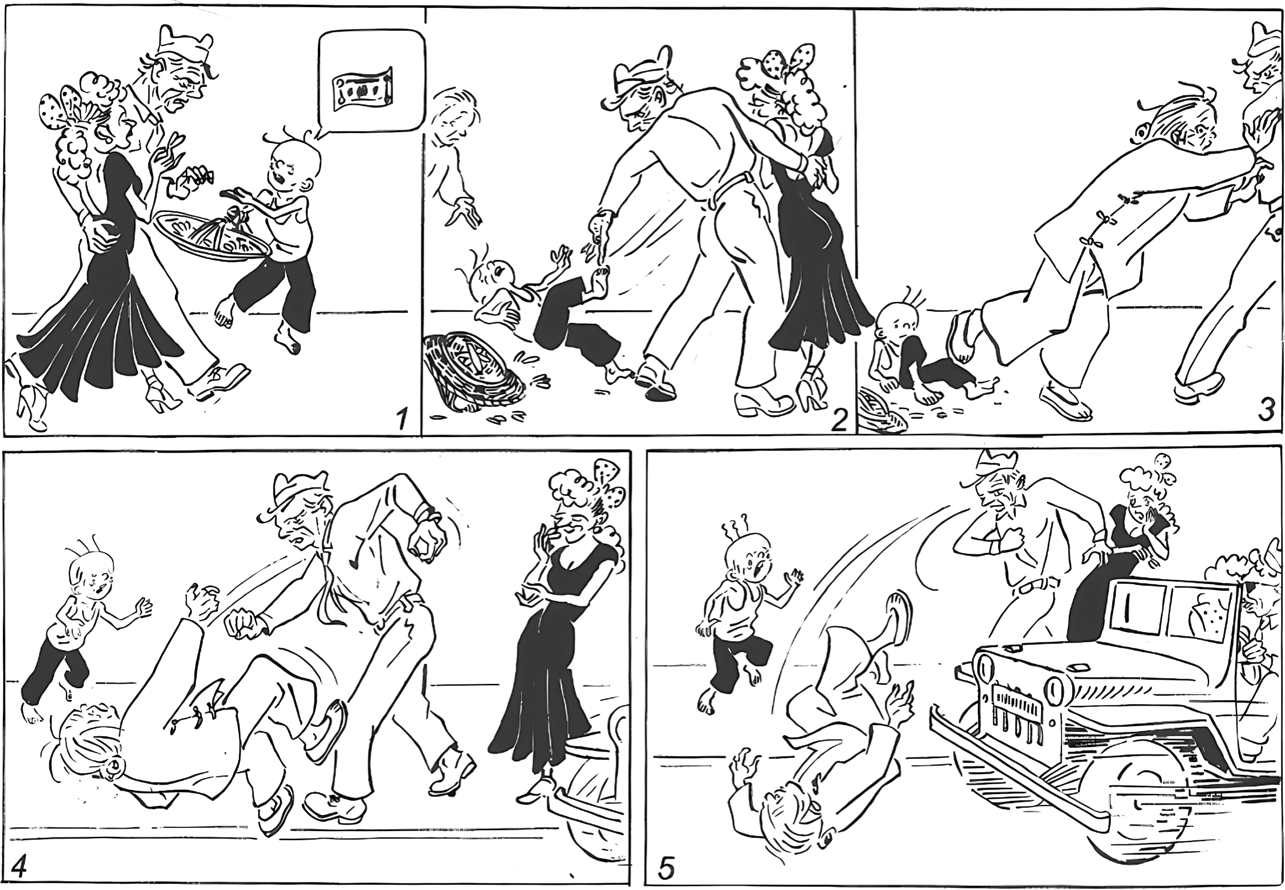

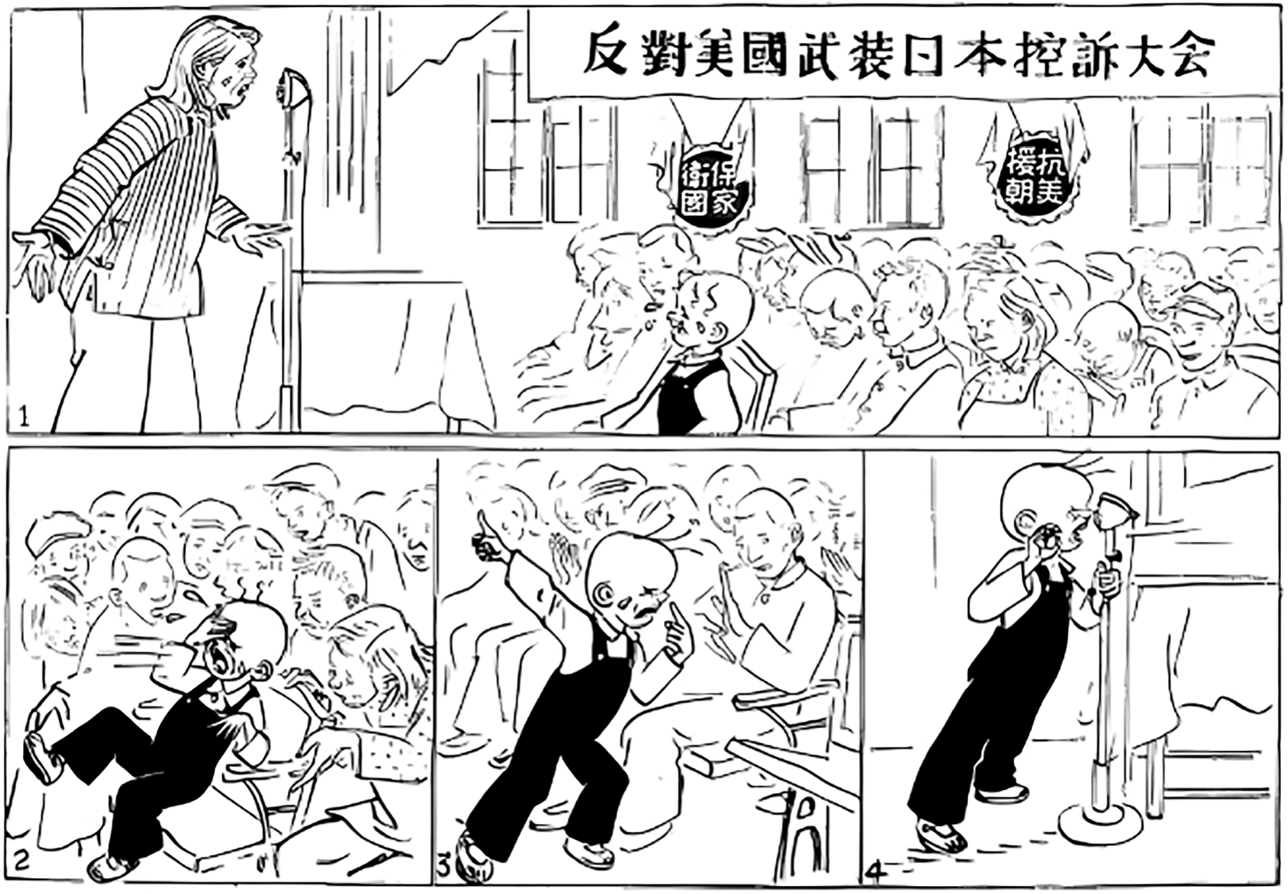

Zhang Leping’s Sanmao comic strips were among the most popular works of the time. The legendary child-hero, Sanmao, whose name derives from the “three hairs” sticking out on his head, first appeared in the early 1930s as a critic of Chinese society. Misbehaving American GIs already figured significantly in the artist’s work in 1947, Adventures of Sanmao, the Orphan (Sanmao liulangji 三毛流浪記). In 1951, Zhang created two new series, Sanmao’s Indictment (Sanmao de kongsu 三毛的控訴) and Sanmao Stands Up (Sanmao fanshen ji 三毛翻身記), and refigured the character into a victim of American brutality to serve the new mission of fighting American imperialists.11 In one story, Sanmao tries to sell flowers on the street and runs into an American sailor who casually picks a flower from his basket without paying and walks away with a fashionable Jeep girl in his arms. Upon chasing the big American man, the emaciated Sanmao is knocked to the ground with one slap. After trying to reason with the sailor, his grandma is punched and falls, run over by a speeding American Jeep. The GI driver, who has one hand over another Chinese girl next to him, then picks up the man and woman and drives away without even a glimpse of the grandma’s body (see Figure E.5). In another story, Sanmao attends an emotional mass denunciation meeting to “oppose the US arming the Japanese.” He bursts into tears after hearing a female victim share her experience of being abused by Americans. Sanmao then jumps at the chance to speak of his own traumatic experience (see Figure E.6). The scene provides an educational session on American violence and an affective script for actual collective sharing in the tens of thousands of denunciation meetings throughout the country.12 Supposedly based on true stories, Sanmao’s experience foregrounds the daily abuse of the Chinese poor.13 Sanmao, the well-liked prototypical Chinese child-hero who used to be a middle-class city kid, a boy soldier in the Second Sino-Japanese War, and an orphan wandering the streets of Shanghai after the war, now becomes a victim and witness to American atrocities and aggression. He is no longer satirical or funny, but evokes strong emotions of anger, hatred, and disdain toward America.

Figure E.5 “Indifference to life,” Sanmao Stands Up by Zhang Leping, 1951.

Figure E.5Long description

Upon chasing the big American man, the emaciated Sanmao is knocked to the ground with one slap. After trying to reason with the sailor, Grandma is punched and falls, run over by a speeding American Jeep.

Figure E.6 “Mass denunciation meeting,” Sanmao Stands Up by Zhang Leping, 1951.

Figure E.6Long description

He bursts into tears after hearing a female victim share her experience. Sanmao then jumps at the chance to speak of his own traumatic experience.

After peaking during the Korea War, anti-American sentiments continued in the Cultural Revolution and into the reform era. Although the direct military and political context has often been forgotten, the theme of American brutality has remained ingrained in national memory, perpetuated through popular works like comic strips, history books, and newspaper features, as well as government publications and scholarly works. For instance, mandatory secondary school history textbooks included the Peking rape incident at least until the 1980s, ensuring its longevity as a collective national memory for future generations.14 Despite his tragic death, rickshaw puller Zang Yaocheng has lived on, with his biography reprinted twice in the 1980s and 1990s and included in the local histories of Shanghai.15 In the midst of the student protest movement in 1989, a comprehensive eight-hundred-page collection of historical materials was published, documenting the Anti-American Brutality movement that had occurred more than four decades earlier.16 In 1986, Jet Li, who grew up in mainland China in the 1960s and 1970s, made his directorial debut and starred in a Hong Kong action movie called Born to Defend (Zhonghua yingxiong 中華英雄).17 It tells the heroic story of Little Jie, a young veteran from the Nationalist Army who valiantly battles American soldiers. When WWII finally ends, he returns to Qingdao and finds his hometown occupied by imperious GIs. Chinese civilians fall victim to their violence, hit by speeding vehicles, sexually assaulted, and clubbed by both American MPs and Chinese authorities. Little Jie’s senior colleague in the army, now a rickshaw puller, and the latter’s daughter, who becomes a bar hostess out of poverty, die from these violent assaults. Little Jie goes on to pursue revenge and eventually defeats and kills the GI criminal. The film, titled Chinese Hero if translated literally, builds upon the trope of everyday abuse and belongs to the genre of the Chinese folk hero narrative, featuring national humiliation and salvation.18 But the Chinese protagonist in Born to Defend is fighting a more powerful and recent imperialist figure, the American soldier. Little Jie represents the ordinary hero, a poor Chinese laborer and common man who defeats GIs with strength and wit and helps his countrymen through loyalty, friendship, and collective resistance. The story centers around the literal and symbolic fights between Chinese veterans and American soldiers, with the latter calling the former “castrated by the Japanese.” It deals with a question different from traditional anti-imperialist folk hero movies. As a character puts it: Who are the real “anti-Japanese heroes,” the American soldiers as often claimed or the nameless Chinese men?

The recurring persona of the Chinese victim facing American brutality, as seen in the characters of Sanmao and Little Jie, testifies to its enduring appeal and longevity within Chinese nationalism. The more recent anti-Americanism since the 1990s conjures up eerie parallels with that of 1945–1949, as perceptions of America once again become filled with contradiction, mixing fantasy and hostility. Despite the strengthening of economic and cultural ties between the two nations, popular animosity toward America could rapidly grow with great intensity. During times of tension, the powerful trope can be easily evoked. For example, following the 1999 North Atlantic Treaty Organization bombing of the Chinese embassy in Belgrade, which killed three Chinese journalists and wounded at least twenty, student protesters stoned the US embassy in Beijing and converted the Statue of Liberty into the “Demon of Liberty.”19 Two years later, mass demonstrations again occurred in major cities following the collision of an American surveillance plane with a Chinese navy fighter jet over the South China Sea, which killed the Chinese pilot. Enraged university students and the public demanded an American explanation, apology, and compensation. Previous anti-American narratives were quickly revived and key messages of American aggression and victimization of Chinese resurfaced. Abstract concepts of national humiliation and sovereignty infringement again became embodied by the killing and suffering of the innocent, and infused with emotional appeal and moral justification.

Emotional intensity, polarizing perceptions of America, and high volatility remain key features of Sino-US relations. Like a ticking time bomb, explosive anti-American sentiment can be triggered overnight by a single event, damaging China-US relations that have been built over decades. It takes only one “accident,” rather than missile strikes or tanks rolling, to shake up the entire relationship. The “ordinary victim” fans the biggest flames among a wide Chinese base. Once unleashed, the weapon of the everyday does not always adhere to the official party line and can take on a life of its own.

A Forgotten Occupation

For the American side, the mission in China in the aftermath of WWII stands as a minor episode in the history of its global military empire. Partly because of the relatively small number of troops stationed in the country and the brevity of their presence, existing studies of postwar US occupations often overlook China. The mission’s vague objectives and mixed results, difficult to define and evaluate, have further contributed to its obscurity in US diplomatic and military history. There is equally a shortage of popular literature on American veterans after the war compared to their predecessors known for adventures and heroism, such as the renowned Flying Tigers in wartime China or even the old China hands of the early twentieth century.20 In reality, there is no lack of reports, agreements, or correspondence on the China mission in military and national archives. The images, artifacts, and tales about American soldiers’ experiences are also preserved in personal letters, family heirlooms, and private collections. Many intimate stories remain skeletons in the closet or have been buried for nearly eighty years, while others can be spotted in veterans’ oral history recordings, reunion pamphlets, news reports, and online forums. Unlike the more coherent narratives of victories, bravery, and sacrifices during WWII, the postwar stories about American soldiers in China are often told in ambiguous and diverse ways. Against the background of shifting geopolitics across the Pacific, these accounts shift among the different themes of liberation, occupation, assistance to an ally, and fights against communism.

Unlike the rich scholarly accounts of US occupation of Japan and Korea, the China story remains comparatively underexplored – particularly the extensive noncombat duties performed by American servicemen, as well as their intimate exchanges with local society. This lack of attention also has to do with the difficulty of situating this chapter within the normative narrative of WWII as “the Good War,” a just war that not only brought prosperity to the American nation, but also peace, progress, and democracy to the occupied people.21 The GI misconduct and subsequent anti-American sentiment, especially in an allied country, do not fit into the triumphalist tale of the occupation in East Asia, but rather speak of the “failures” that have consumed American minds for decades. In the heated environment of the early Cold War, the US government attempted to play the role of a liberal, benevolent leader of the free world. Nevertheless, soon after the Allied victory, nationwide protests erupted in China, becoming what a Time magazine piece called the “most conspicuous demonstrations of ill will” against America globally. This realization came as a painful surprise, as Americans became acutely aware that “much of the rest of the world intensely dislikes them,” particularly given their record of “staggering charities” to the world.22 One year after their complete withdrawal, American forces, including veteran officers and divisions that had previously served in China during and after WWII, were deployed to Korea. There they once again encountered Chinese troops, armed with American equipment that had been captured during the Chinese civil war.

Caught between the monumental conflicts of WWII and the subsequent Korean and Vietnam Wars, American operations in postwar China seem to occupy an awkward and insignificant position. However, they established important precedents and patterns for global engagements during and after the Cold War while providing comparative insights into the workings of US military empire. Operation BELEAGUER marked “the end of a decade-long Marine presence in China but represented a postwar beginning for American foreign policy and the Corps.” It served as the debut of “a series of sometimes frustrating MOOTW missions” undertaken by the Marine Corps as “America’s force-in-readiness,” encompassing all three major types of Cold War operations: humanitarian assistance, nation assistance, and peacekeeping.23 The operations in China provided a preview, an experimental testing ground, and a dress rehearsal for this new style of warfare, shedding fresh light on its strengths and limitations during the era of limited wars.

In particular, US soldiers in China faced significant challenges due to ambiguous and sometimes conflicting objectives. Their mission impossible – to maintain peace and neutrality while providing assistance to the Nationalist Government – was fraught with the risk of deep entanglement in a violent civil conflict. This precarious balance was epitomized by incidents in Anping, Guye, and elsewhere, where US forces were ambushed by local Communist troops employing guerrilla tactics in a Maoist “People’s War” that would later become widely used around the world. As noted by Richard Bernstein, a seasoned journalist with extensive experience in China, “they were the first such confrontations between American forces and a new kind of enemy, one that was going to become familiar over the succeeding decades in Vietnam and, still later, in Iraq and Afghanistan, in the kind of confrontation that gave rise to the term ‘asymmetric warfare.’”24 The operation’s key challenges were further highlighted following marines’ shelling of Anshan, which led to intensified American criticism over the killing of civilians and the perceived recklessness of placing soldiers in unnecessary danger. This growing public unease with overseas military engagements and demands for the return of American troops would also become a persistent theme. Despite the limited scales of direct confrontations, US military involvement, intended to stabilize and assist a friendly allied nation, ended up becoming a source of instability within Chinese society. These military and political risks foreshadowed similar patterns in later US interventions, such as those in Korea, Vietnam, the Dominican Republic, and the Middle East. For example, in 1958, invited by its prime minister, US troops were deployed to Lebanon to protect its independence and contain communism following growing instability. In 1965, US troops were sent to the Dominican Republic in response to a civil war outbreak. In both cases, what began as neutral, benign peacemaking operations quickly escalated into combat missions. These actions drew both local and international charges of US imperialism and failed to resolve the underlying domestic and regional issues.25

In the legal domain, the United States’ practices in China have also established important precedents. For instance, the renewed Sino-US agreements regarding the status of US military personnel in China in 1946 marked “the subtle yet fundamental shift in the legal foundation of U.S. troops’ extraterritorial privileges,” from “the expediency of temporary wartime combat missions to a potential prerequisite for long-term military presence.” This new justification, now based on mere presence rather than active combat duty, became the “foundational doctrine that governed the legal status of U.S. troops abroad for the next several decades,” setting a precedent for the Status of Forces Agreements between the United States and various allies during the Cold War.26 After the Nationalist Party decamped to Taiwan, the small Military Assistance Advisory Group was sent to the island and formally operated as part of the US embassy; it therefore enjoyed diplomatic immunity. With the growing number of the group members and other US military personnel in Taiwan, together with a rise in criminal cases, the Agreement between the Republic of China and the United States of America on the Status of United Armed Forces in the Republic of China was reached in 1965. It was in effect until 1979, when the United States terminated diplomatic relations with the Republic of China and all US military personnel left Taiwan.27

In terms of local animosities, postwar Chinese protests against American soldiers’ misconduct and the US military presence reflect patterns similar to contemporary anti-base movements in alliance partners such as Japan, South Korea, and the Philippines.28 For instance, in June 2002, the tragic deaths of two Korean schoolgirls, crushed by a US Army armored vehicle, ignited nationwide demonstrations characterized by the familiar rallying cry, “Yankee go home!”29 In Okinawa, recurring incidents of sexual violence committed by American servicemen continue to be a major trigger for protests. On Christmas Eve 2023, a local girl was allegedly kidnapped and raped by a member of the air force. In the Philippines, public outcry over toxic waste contamination, environmental destruction, human trafficking, and the abandonment of Amerasian children continues to fuel movements against the US military presence following the successful closure of US bases in 1992.30 These incidents highlight the unintended consequences of American overseas bases, transforming them into “embattled garrisons” that are strategically important but politically vulnerable.31 As Andrew Yeo, a scholar in international politics, has pointed out, local protests cannot be simply dismissed as “a form of blanket anti-Americanism.” Instead, the political contestation surrounding these military bases blurs the lines between “high and low politics,” reflecting deeper societal concerns and national sentiments.32

Today, many of these institutional, conceptual, and personal connections between American soldiers and Chinese civilians remain unacknowledged due to the deepening Cold War conflicts that immediately followed. Nor are the sustained sociocultural impacts that quotidian encounters exerted on American society at large duly recognized. The US military presence after WWII exposed tens of thousands of servicemen to lives beyond their comfort zones back home. While performing assigned missions, determined by high-level diplomatic exchanges, political negotiations, and military strategies, US soldiers on the ground often forged intimate connections with local populations by exchanging goods, services, languages, and cultures, an encounter that both followed and contradicted official policies and popular representations. Christina Klein, for example, has identified the late 1940s and 1950s as a distinct cultural moment during which Americans became fascinated with Asia and the Pacific through the proliferation of popular cultural productions. Thanks to the empire’s unprecedented reach during the Cold War, Americans produced and consumed a surge of new plays, movies, novels, and nonfiction books about Asia.33 If these new representational works, often fictional, helped propagate the new ideology of global integration with mutual understanding and benefits, the presence of US troops formed a direct force of everyday diplomacy. China was embodied, enacted, and brought home via GIs’ letters, keepsakes, spouses, tastes, vocabularies, and memoirs. Together with the larger body of troops who served in Taiwan, Japan, Korea, Vietnam, and other areas in the region, they helped reshape American identities in the new age of global expansion.

Perhaps there is no better illustration of such intricate relations than the story of Anna Wong. In 1947, General George Marshall left China to assume his new position as the US secretary of state. He invited a beloved maid, Anna, to America, and she agreed. A few years later, when the US Congress approved legislation that allowed twenty thousand Chinese to enter the country, Anna reunited with her family, who were among the first to be admitted. But the beautiful story of friendship and reunion is not without a twist. The patriotic Chinese woman “without much education,” who won Marshall and his wife’s highest praise for her service, also had issues with the general, not over pay or work hours, but rather the harsh measures that Marshall supposedly took in dealing with the Nationalist Government during his mediation mission. She once burst out, “General Marshall! You no help China, Anna no work for you!” The general, who had chosen China as his duty station from 1924 to 1927 and learned some Chinese while leading the 15th Infantry as a lieutenant colonel, often ignored Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek’s requests and complaints. But on this occasion, he sat down to hear Anna’s protest, and it finally took Mrs. Marshall several days and some personal diplomacy to persuade Anna to stay.34 Stories like this have escaped most scholarly attention. But they help us better understand the potent force of Chinese nationalism, the distinctive position of China within the American global order, and the deep ties that the two sides have forged through an entangled relationship.

Where to (Re)Turn

No one here seems remotely aware of Kunming’s past. Amazingly, the travel agents here have almost no maps. “And Kweiyang?” I ask. I remember Kweiyang as being 500 km or so to the east, eighteen hours away by jeep – but the town appears to have fallen down a deep ravine. A place which I considered my war-home has apparently been excised from [the] foreigner’s itineraries and local memory.

When Barney Rosset, an influential American publisher, returned to China for the first time in 1996, he felt disappointed. But it was not just the disappearance of Guiyang (Kweiyang), where he had worked as an army photographer in the 1940s, that he lamented, but also the erasure of the entire history of American contributions to China. Rosset’s story is far from unique. Many US veterans returned to China after the country reopened in the late 1970s and found little trace of the old scenes that they had vividly remembered. Their Chinese interpreters, associates, and colleagues in mainland China also largely remained silent on this history, even to their own families, due to the harsh treatments they received during the Cultural Revolution or the fear of being accused as American spies in the future. This significant era, though quite recent, seems a lost one in both the United States and China.

In hindsight, the quotidian encounter between American soldiers and Chinese civilians seems to speak of a doomed loss. Systemic racism and sexism within the US military, as well as the unequal dynamics of uneven reciprocity between the two allied nations, planted not only the seeds of tension, but also the roots of outright conflicts. In the immediate term, the American military occupation, intended to assist the Nationalist Government, ended up contributing to its downfall. As one marine researcher put it, the mission impossible was a military success but a political failure.36 Communist propaganda campaigns successfully linked everyday grievances against the American military to the Party’s political maneuvers against the Nationalist Government. In the long run, this direct encounter transformed Chinese views of Americans, which shifted from admiration to hostility. All of these speak to the potential perils of an occupation mission in a foreign nation.

But this extraordinary encounter also created new connections as seen in stories like Rosset’s. The former soldier-turned-publisher maintained his lifelong interest in China, and his long-standing wish was to share his photos with younger Chinese generations – a wish that finally became reality in 2014 at Kunming Municipal Museum. Jeno Paulucci, who had served in the armed forces in Asia, converted his fellow GIs’ love for Chinese food into a successful empire of ready-prepared Chinese food for the mass market, with the famous Chun King brand of chow mein with a similar-sounding name to Chongqing, China’s wartime capital. By the 1950s, sales of frozen and processed Chinese food had increased 70 percent since the war, making it a major national food.37 Across the ocean, the famous “Beijing Jeep” was born in 1969, co-opting the design and symbolism of the United States and showcasing China’s newly developed industrial power and material progress. As the country embarked on reform and opening-up policies in the late 1970s, the first Sino-American automobile joint venture was formed, which manufactured a new Beijing Jeep model.38 These stories are testaments to the profound bonds that were forged, suggesting that even in a brief moment of intimacy and estrangement, military missions should also be understood as actual encounters, which often have longer-lasting and more significant legacies than the pursuit of immediate strategic objectives.

Perhaps not all is lost. The postwar era was a precarious time in Sino-US relations, followed by bloody conflicts. But it was also a transformative period that ushered in many new beginnings. During this critical juncture, the two groups – from commanders and statesmen to laborers and servants – engaged in unprecedented human, socioeconomic, and cultural exchanges that would not recur until the door to China reopened in the late twentieth century. When I trace Anna Wong’s family history across the Pacific Ocean, track the loss of General Marshall’s Jeep on the streets of Nanjing, and zoom in on Shen Chong’s body in the Beijing courtroom, I am shown a much larger and different world – one defined by quotidian practices and politics. While state policy and ideological differences may have set the tone for bilateral relations, everyday encounters determined the texture, individual notes, flats and sharps, half beats and pauses, and occupational hazards and opportunities of the era. Only by focusing on these microlevel human interactions can we truly understand this pivotal chapter in Sino-American relations and the underlying dynamics at play. Within these entangled relations were racial prejudice, failed national policies, radically changed perceptions, and lost chances of accommodation; there were also newly forged connections that shaped history and the present world, together with lost lives, unresolved tensions, unfulfilled justice and promises, unrecognized injuries and agonies, and overdue recognition and recollection.

Today we stand at another major crossroads of Sino-American relations. With the unraveling of the symbiotic relationship known as “Chimerica,” a term first coined by Niall Ferguson and Moritz Schularick, one critical question remains: What role do everyday interactions play in shaping the great power rivalry and the evolving global order?39 Grassroots interactions have reached new heights, with the US issuing “105,000 new student visas to Chinese citizens in 2023, the highest since before the pandemic,” solidifying their status as the largest group of international students in the country.40 Yet the two governments are embroiled in an ugly trade war, bitter propaganda battles, intensifying military competition, and high-stakes geopolitical posturing. Tragically, it is ordinary people who bear the brunt of these conflicts. Against the backdrop of the Covid-19 pandemic, Chinese students, Chinese immigrants, and Chinese Americans have faced racial profiling, verbal abuse, and physical attacks in the United States. Conversely, anti-American sentiment has also spilled into violent incidents in China, such as the June 2024 stabbing of four Iowa college instructors in an exchange program by a Chinese man in a Jilin public park, apparently because of a minor collision while walking.41 These ostensibly “mundane frictions” reveal deep systemic biases, lingering grievances, and the toxic effects of propaganda on both sides – forces that continue to shape perceptions and fuel the broader China-America conflict.

If one lesson can be learned from this entangled history of encounter, as we are again in an extremely volatile period of Sino-US relations, it is that everyday practice and politics matter. As tensions between the two nations rise alongside an unprecedented level of grassroots interactions, we must bring back to the center of our study the everyday exchanges, which have suffered a particular type of historical erasure and political distortion in the loaded discussions of American imperialism and Chinese Communism. These exchanges provide key opportunities for fostering understanding and building rapport amidst large nationalist struggles and global conflicts. Ultimately, it is the ordinary actors who, wittingly or unwittingly, by coercion or by choice, have always endured at the heart of history, conflict, and reconciliation. They form the core of this study, and it is to the forgotten history of everyday occupation that this book is devoted.