Introduction

In many democratic societies, conflict over how to collectively remember the historical past has – sometimes driven by culture wars and identity politics, sometimes by demands to address historical wrongs – heated up considerably in recent years. These “memory wars” are particularly pronounced in settler colonies such as the United States, Canada, Australia, and Aotearoa New Zealand, where monocultural, Euro-centric master narratives of national history have come under increasing pressure from Indigenous counter-narratives that give voice to painful experiences of violence and oppression. Battles are often fought very publicly and typically revolve around state-sponsored sites of memory production – for example, museums, monuments, and school education (e.g., Clark Reference Clark2006; Dean and Rider Reference Dean and Rider2005; Failler Reference Failler2018; John Reference John and Blatt2023; Kidman and O’Malley Reference Kidman and O’Malley2020; Maddison Reference Maddison, Gensburger and Wüstenberg2024).

Why do difficult histories of colonialism, revealed by memory activists and critical revisionist historians, carry such potential for social conflict? One important, and perhaps the most important, reason is that confronting settler societies with previously repressed memories of colonial violence threatens to “spoil” national identity. As Heisler (Reference Heisler2008, 15) explains, the self-perceptions of nations “are intimately and intricately connected with the stories they have embraced regarding the path they have traveled to the present.” This means that, by refuting the master narrative that frames the settler understanding of history, difficult histories also call into question the values of national identity that the master narrative seeks to substantiate.

In Aotearoa New Zealand, national identity has long been construed around the values of “respect” and “tolerance.” Key to this construction is a particular representation of the historical past that draws heavily on the Treaty of Waitangi to portray colonization as “a fairly benign and consensual experience” (Bell and Russell Reference Bell and Russell2022, 22). The Treaty of Waitangi – signed between Māori tribal leaders and the British on 6 February 1840 – thus provides a “usable past” (Wertsch Reference Wertsch2002: 31) in that it helps to describe the beginnings of the nation “as a negotiated and mutually agreed-upon covenant between two peoples rather than as a result of the invasion and expropriation of Māori land and culture” (Kidman Reference Kidman, Epstein and Peck2018: 104). However, this romanticized interpretation of the Treaty no longer goes unchallenged. Most importantly, Māori political activism has generated powerful counter-narratives that shine a light on the trauma endured by tangata whenua (people of the land) after the signing of the Treaty, especially during the period of the New Zealand Wars (mid-1840s to early 1870s).

While there is a growing number of academic studies that investigate how official memory in Aotearoa New Zealand has responded to the ever-louder articulation of difficult histories (e.g., Attwood Reference Attwood2013; Kidman Reference Kidman, Epstein and Peck2018; Light Reference Light2022a), one important site of memory-making has remained ignored by scholarly research: the Waitangi Treaty Grounds. My article addresses this gap through a narratological analysis of the permanent exhibition Ko Waitangi Tēnei: This is Waitangi, which traces the history of the Treaty from the first colonial encounter to the present.Footnote 1 Applying a narratological framework shows that the exhibition narrates the history of the Treaty along the quest masterplot (Booker Reference Booker2004). As I will elaborate in more detail later on, this emplotment strategy, together with other storytelling techniques, serves to portray the events of the New Zealand Wars as the “natural result” of the (supposedly) exceptional by-legal-agreement mode of colonization. The naturalizing move mutes uncomfortable questions about the New Zealand Wars, thereby safeguarding the image of a respectful and tolerant nation.

My article not only makes a significant contribution to the academic literature on national identity construction in the context of difficult histories, but – by investigating the Ko Waitangi Tēnei exhibition through an analytical framework informed by structuralist narratological theory (e.g., Bal Reference Bal2009; Chatman Reference Chatman1978; Genette Reference Genette1980) – the article also advances the conceptual and theoretical basis for investigating storytelling in historical museums. “Memory museum narratives,” as Hagen Kjørholt (Reference Hagen Kjørholt, Barndt and Jaeger2024, 59) rightly points out, “are narratologically understudied.” This is all the more surprising given that the narrative vehicle of the museum has been described as “particularly powerful,” distinct from other storytelling devices (such as books and movies) in that it offers “a fully embodied experience of objects and media in three-dimensional space, unfolding in a potentially free-flowing temporal sequence” (Hourston Hanks, Hale, and MacLeod Reference Hourston Hanks, Hale, MacLeod, Macleod, Hanks and Hale2012, xxi). The unique multimodal combination of material culture and immersive environments also makes museums extremely powerful when it comes to narrating the historical past for the sake of national identity construction. While the exhibition of material objects allows a museum to substantiate narratives of the nation’s past and “prove” their factual accuracy, the bodily sensations of moving through space encourage visitors to re-enact and emotionally re-experience the historical events that “forged” the nation (Watson Reference Watson2020; Weiser Reference Weiser2017).

Storytelling: A narratological framework

Structuralist narratology reduces narratives to their essential components and shows how they operate within a system of rules and conventions. Even though structuralist narratology was originally developed to study narratives in literary fiction, key concepts have since been applied to storytelling in other fields, including history (Munslow Reference Munslow2019), international relations (Oppermann and Spencer Reference Oppermann, Spencer, Mello and Ostermann2023) and public policy analysis (Jones et al. Reference Jones, McBeth, Shanahan, Jones, Shanahan and McBeth2014). The benefits of the structuralist approach to narrative inquiry are twofold. First, by describing narratives in terms of their formal properties, structuralism enables us to distinguish narratives from other forms of discourse. Second, structural narratology alerts us to the fact that the author of a given narrative chose from a larger repertoire of narrative tools, which helps reveal storytelling as a goal-oriented and strategic practice.

Master and specific narratives

Not too dissimilar from how we – as individuals – tell autobiographical life stories of how we became who we are, national communities harness collectively shared narratives of the past to maintain a coherent sense of identity across time (Burnell, Umanath, and Garry Reference Burnell, Umanath and Garry2023, 317; Liu and Hilton Reference Liu and Hilton2005). At an implicit, non-conscious level reside so-called master narratives, which provide “a broader view of history, a basic ‘story line’ that is culturally constructed and provides the group members with a general notion of their shared past” (Zerubavel Reference Zerubavel1995, 6). Master narratives project present national identities onto the past, thereby naturalizing the nation as an essentialist and timeless entity. To endow the nation with specific qualities, master narratives connect historical events through simplified, monocausal explanations, such as “the nation has always been driven by its search for freedom” (cf. Carretero and van Alphen Reference Carretero, van Alphen and Wagoner2017). This invariably requires repressing memories of historical events that undermine the causal account of history offered by the master narrative – for example, memories of social groups having their freedoms taken away.

Master narratives are typically not told in explicit ways. Rather, what we find at museums and other “sites of memory” (Nora Reference Nora1996) are specific narratives about discrete historical events. Whereas master narratives are devoid of precise details, “specific narratives are surface texts that include concrete information about the particular times, places, and actors involved in an event” (Wertsch Reference Wertsch2021, 77). Nevertheless, master narratives are still at work below the surface, providing “schematic narrative templates” (Wertsch Reference Wertsch2008) for the organization of specific narratives. Put simply, in a given society, specific narratives will differ in terms of the historical events that they focus on, but the abstract core idea (e.g., the freedom-seeking nation) will remain relatively constant. Needless to say that, in order to replicate the general story line prescribed by the master narrative, specific narratives have to be similarly selective when reconstructing the historical past.

Seen through a narratological lens, specific narratives consist of two parts: the story and the narrative discourse. Footnote 2 According to Chatman (Reference Chatman1978, 19-20), the story is composed of “existents” – that is, actors and settings – and events brought about by the actions of the actors. Put differently, story refers to the “what” of the narrative. Discourse, on the other hand, concerns the “how” of the narrative – or, in other words, the means by which the story is communicated. “One important point that the distinction between story and discourse brings out,” as Abbott explains, “is that we never see a story directly, but instead always pick it up through the narrative discourse” (2002, 17; emphasis in the original). Hence, the underlying assumption is that we can discriminate between the events as they actually happened and the events as they are told by the narrator (Keen Reference Keen2003, 4).

Based on the work of Bal (Reference Bal2009, 8) and other structuralist scholars, it is possible to identify several processes that are involved in narrating a story. Most importantly, the narrator (1) emplots events into a temporal sequence; (2) decides on the tense and the timing of the narrative; (3) provides actors with distinct traits, thereby transforming them into characters; (4) describes the locations and spaces in which events occur; and (5) makes a choice among alternative “points of view” from which the story can be presented.

Existing studies of historical museum exhibitions have investigated some of these storytelling processes – in particular, tense (e.g., Hagen Kjørholt Reference Hagen Kjørholt, Barndt and Jaeger2024; Weiser Reference Weiser2017, 49-58), characters (e.g., Khlevnyuk Reference Khlevnyuk2023; Kazlauskaitė Reference Kazlauskaitė2022), and point of view (e.g., Guichard-Marneur Reference Guichard-Marneur2018; Dixon Reference Dixon2017). However, the various narrative elements are commonly treated in isolation without considering the interplay between them. Moreover, the concept of emplotment, despite being a defining feature of any narrative, has so far largely been neglected by historical museum analyses. In what follows, I will therefore provide a comprehensive overview of key narratological concepts, paying special attention to the question of how to arrange events into a plot. Borrowing inquiry methods from the field of museum design research (e.g., Austin Reference Austin2020; Hooper-Greenhill Reference Hooper-Greenhill2000; Hourston Hanks Reference Hourston Hanks, Macleod, Hanks and Hale2012; Hughes Reference Hughes2021; Pang Reference Pang and O’Halloran2004; Ravelli Reference Ravelli2006), the narratological framework will then be applied to decode storytelling in the Ko Waitangi Tēnei exhibition.

Emplotting events

The narrative act of emplotment relates to “the process by which situations and events are linked together to produce a plot” (Herman Reference Herman2009, 184), and is considered an essential part of storytelling. For example, as Brooks (Reference Brooks1992, 5) argues, “a narrative without at least a minimal plot would be incomprehensible. Plot is the principle of interconnectedness and intention which we cannot do without in moving through the discrete elements – incidents, episodes, actions – of a narrative.”

Building on Forster (Reference Forster1927, 86), many narratologists see the crucial difference between story and narrative discourse in the move from a simple chronology of events to emplotted causality – that is, in the establishment of a causal relationship between individual events (e.g., Abbott Reference Abbott2002, 37). Along these lines, White (Reference White1973, 5-7) maintains that narrating the historical past is a two-step process. The first step involves arranging a selection of events into a chronologically ordered sequence. In a second step, this sequence is then emplotted in a fashion that gives the impression of a cause-and-effect relationship. Emplotment thus requires engaging with questions such as: What happened next? How did that happen? Why did things happen this way rather than some other way?

Importantly, the answers to these questions are not found in the events themselves. Instead, as White (Reference White1980, 23-24) elaborates further, the plot is always constructed retrospectively through narrative techniques, in an attempt to bring coherence and closure to the chronological sequence of events. Moreover, it is only through emplotment – and by describing how individual events fit into a particular causal chain of events – that individual events acquire meaning. In other words, events and their sequence can be emplotted in different ways, which produces different interpretations of these events and gives them different meanings.

It is important to highlight that causation does not have to be communicated explicitly; rather, a causal relation between two events can merely be implied (Chatman Reference Chatman1978, 45-46). Perhaps the most common way in which a narrator can (implicitly) suggest a causal sequence is by emploting events along so-called masterplots. Essentially, masterplots are “skeletal and adaptable” (Abbott Reference Abbott2002, 43) frameworks for narrative emplotment that recur across genres and cultures. Masterplots are not to be confused with master narratives. As explained above, master narratives are culturally dominant narratives that shape collective sensemaking more broadly, often serving to legitimize certain values and power structures. The purpose of masterplots, in contrast, is to engage audiences in explicit, highly tellable narratives. Moreover, masterplots have to be set apart from so-called story grammars. Whereas story grammars focus on the formal structure and organization of a narrative (e.g., exposition, conflict, resolution), masterplots are more focused on the content of a narrative – what happens, why, and how it resolves.

Scholars have offered several typologies of masterplots (e.g., Hogan Reference Hogan2013; Tobias Reference Tobias1993; White Reference White1973, 7-9), one of the most widely employed of which is Booker’s (Reference Booker2004) classification, distinguishing between seven different archetypal plot types:

-

- Overcoming the monster. The protagonist sets out to defeat an antagonistic force that threatens them, their loved ones, or their community. Examples: Jaws, Dracula.

-

- Rags to riches: The protagonist rises from a lowly or disadvantaged position to success, wealth, or happiness, often after overcoming obstacles or hardships. Examples: Cinderella, Harry Potter.

-

- The quest. The protagonist and companions set out on a journey to achieve a goal, such as finding a treasure or solving a great problem. Along the way, they face challenges and temptations. Examples: The Lord of the Rings, The Odyssey.

-

- Voyage and return. The protagonist goes on a journey to a strange or unfamiliar place, faces dangers or difficulties, and then returns home having gained new insights or experiences. Examples: Alice in Wonderland, The Wizard of Oz.

-

- Comedy. A light-hearted or humorous story where confusion or misunderstanding eventually leads to a happy resolution. Examples: A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Bridget Jones’s Diary.

-

- Tragedy. The protagonist has a major flaw or makes a grave mistake, leading to their downfall or demise. Often, they are unable to change their fate, despite their efforts. Examples: Macbeth, Hamlet.

-

- Rebirth. The protagonist undergoes a transformation, either literal or metaphorical, often moving from darkness to light or from a state of death to life. Examples: A Christmas Carol, Beauty and the Beast.

Masterplots are considered powerful storytelling devices for a number of reasons. First, because masterplots are strongly ingrained in culture, they are easily recognized by audiences, which enhances comprehension of and engagement with the narrative. Through masterplots, emplotted events are rendered familiar and comprehensible, “not only because the reader now has more information about the events, but also because he [sic] has been shown how the data conform to an icon of a comprehensible finished process, a plot structure with which he is familiar as a part of his cultural endowment” (White Reference White1978, 86; emphasis in the original). Second, masterplots typically have a clear moral dimension, simplifying complex issues by framing them in terms of good vs. evil or justice vs. injustice (Abbott Reference Abbott2002, 44-45). This can make narratives more compelling, as they align with deeply held societal beliefs. Third, even though they are highly recognizable, masterplots are flexible enough to be adapted across different genres and contexts, as evidenced by the fact that masterplots have been revealed not only in novels and movies, but also in various forms of strategic communication (e.g., Hellmann Reference Hellmann2021, Reference Hellmann and Oppermann2024; Kent Reference Kent2015; Spencer and Oppermann Reference Spencer, Oppermann, Richardson and Rittberger2021).

Tense and timing

The narrator does not just emplot events into a causal sequence, but also decides on what Genette (Reference Genette1980) calls the tense of the narrative. Tense rests on the conceptual division between story time and discourse time, and is made up of three main components.

First, there is the temporal order of events, which urges us to ask whether the events of the story get narrated in the exact order they occurred or whether the narrator employs disorderly (anachronous) narration. Anachronies include flashbacks (analepses) and flashforwards (prolepses). The latter can be further classified into (explicit) announcements and (implicit) hints, with important consequences for the narrative: whereas announcements work against suspense, hints can be used to increase suspense (Bal Reference Bal2009, 95-96).

Second, when unpacking the tense of a narrative, we need to consider frequency – that is, the number of times an event occurs in the story and the number of times it is told in the narrative discourse. According to Genette (Reference Genette1980), three options are thinkable: (1) singulative narrative: telling once what happened once; (2) repetitive narrative: telling multiple times what happened once; (3) iterative narrative: telling once what happened multiple times.

Third, Genette (Reference Genette1980) wants us to pay attention to the duration of a narrative, which – when applied to literary fiction – concerns the difference between the time it takes to read out the narrative (discourse time) and the “real time” of the story events (story time). Variations in duration create a narrative rhythm whereby some events are narrated at slower speeds and thus given more attention than others (Bal Reference Bal2009, 98-99).

Characterizing actors and locations

As already explained, the story consists not only of events, but also of existents – in particular, actors and locations. In the narrative discourse, existents undergo a process of characterization through which they are ascribed with properties.

One way to characterize actors is to assign them functional roles in the narrative, such as hero, villain, or victim. However, such typological categorizations present a number of limitations. Not only do they reduce characters to simplistic, one-dimensional roles and restrict storytelling possibilities, but – by portraying characters merely as “types” – they also discourage audiences to emotionally invest in the characters. Narratives, as Hogan (Reference Hogan2013, 39) argues, “remain threadbare if they are not particularized beyond typological selection.” Hence, a better, because more nuanced and flexible, approach is to characterize actors by a set of traits. Understood as “relatively stable or abiding” (Chatman Reference Chatman1978, 126) qualities, traits can be distinguished from more ephemeral psychological phenomena, like feelings, moods, or thoughts. Characterization by traits often proceeds through binary oppositions. This means that characters are placed on semantic axes between pairs of opposing traits (e.g., brave-cowardly, honest-deceptive), thereby creating clear distinctions between different characters (Bal Reference Bal2009, 127).

There are at least three ways in which characters’ traits can be conveyed (Bal Reference Bal2009, 131-32; Chatman Reference Chatman1978, 119-126; Jannidis Reference Jannidis, Hühn, Pier, Schmid and Schönert2009, 18-23; Keen Reference Keen2003, 64-66). First, the narrator can describe a character’s traits directly and explicitly. Second, a character can be presented implicitly, asking audiences to deduce the character’s traits from their actions and speech. Third, knowledge of masterplots helps audiences make inferences about characters and their traits. In the latter mode of characterization, inferences are hence not based on information given by the text itself, but on references to cultural conventions. For example, if audiences are familiar with the overcoming the monster masterplot, they will know to situate hero and monster at opposite ends of certain semantic axes, such as selfless-egocentric or caring-heartless (see Booker Reference Booker2004, 33).

While actors are characterized by personal traits, spaces and locations are characterized by their symbolic meanings. Rather than seeing the spatial setting as a mere backdrop for action, structuralist narratologists view locations and spaces as semiotic signs that carry thematic or emotional connotations. Similar to how characters are situated along semantic axes, structuralist analyses often focus on binary oppositions between different spaces, such as safe vs. dangerous or civilization vs. wilderness (Bal Reference Bal2009, 221; Ryan Reference Ryan, Hühn, Pier, Schmid and Schönert2009, 428-429). That is to say, structuralist narratologists understand the immediate setting in which the plot unfolds not as an isolated element but as part of a broader narrative world. Settings thus acquire their symbolic meaning in relation to other spaces in the narrative. However, because the narrative world cannot possibly be described in all its details, audiences are required to use their imagination and pre-existing knowledge to picture spaces not explicitly mentioned in the narrative.

Narrator

Lastly, structuralist narratology highlights that narratives can be told from a variety of perspectives, making it possible to identify different types of narrators. Simply defined, the narrator “is the entity from whom the discourse comprising the story emanates” (Keen Reference Keen2003, 34). What is vital to understand is that the narrator is a textual creation and can thus be differentiated from the author of a narrative (Chatman Reference Chatman1978, 146-151).

At the most basic level, we can make a distinction between homodiegetic and heterodiegetic narrators (Genette Reference Genette1980, 244-245). Without the jargon, this translates into a simple question: Is the narrator also a character in the narrative or not? While the homodiegetic category encompasses “I” and “we” narratives, the heterodiegetic category subsumes “he” and “they” narratives. The latter category of third-person narrators can be further broken down into subcategories. First, there is the question of whether the narrator is omniscient or limited – a distinction that goes back to Genette’s discussion of narrative focalization (1980, 189-198). Whereas the omniscient narrator “is located, godlike, above and beyond the world of the story” and “sees and knows everything” (Fludernik Reference Fludernik2009, 92), the limited narrator tells the story from the perspective of one character and does not know more than the character him- or herself. Second, Chatman (Reference Chatman1978, 196) presents us with the question of whether the narrator is overt or covert. Answering this question is a matter of degree rather than of absolute categories. Towards the overt end of the spectrum, the narrator articulates their own views and makes their presence felt stylistically; at the covert end, on the other hand, the narrator is stylistically inconspicuous and does not present themselves as the articulator of the narrative.

Decoding the preferred reading

Structuralist narratology has been criticized for not taking seriously the audiences that “consume” and make sense of narratives. Perhaps the most forceful critique comes from post-structuralist narratologists who argue that narrative texts are, by themselves, not carriers of meaning, but instead insist that meaning is constructed through interaction between text and reader (see Herman and Vervaeck Reference Herman and Vervaeck2019, 209; Huisman Reference Huisman, Fulton, Murphet, Huisman and Dunn2005, 39). Related to this, museum studies scholars emphasize that museum visitors should be perceived “as diverse, plural, and active, rather than as a relatively homogeneous and rather passive mass” (Macdonald Reference Macdonald and Macdonald2006, 8). Empirical studies show that, shaped by their backgrounds, motivations, and personal preferences, museum visitors engage with exhibitions in varied ways – for example, by not following the prescribed circulation path or by skimming (or even skipping) certain sections (see Davidson, Reference Davidson and McCarthy2015). Of particular relevance to any narratological analysis is the finding that museum visitors may narrate their own biographies into the museum experience (and the museum experience into their biographies), which suggests an entangled rather than a uni-directional storytelling process (Schorch, Reference Schorch, Witcomb and Message2015).

While I understand that museum visitors may co-participate in the creation of meaning, I want to refer to Stuart Hall (Reference Hall, Hall, Hobson, Lowe and Willis1980) who emphasizes that – although texts are polysemic, in that they are open to multiple interpretations – cultural institutions and organizations generally seek to impose a “preferred meaning” on the texts they produce. In accordance with Hall’s argument, the structuralist framework I propose focuses on unpacking the preferred reading of the historical past that a museum aims to establish through its storytelling efforts. The framework is not designed to analyze whether audiences accept or reject the preferred reading. This focus on museums as storytellers is by no means narrow, for it follows the dominant top-down approach to collective memory, which assumes that “a ‘collective memory’ – as a set of ideas, images, and feelings about the past – is best located not in the minds of individuals, but in the resources they share” (Irwin-Zarecka Reference Irwin-Zarecka1994, 4).Footnote 3

New Zealand’s master narrative: from monocultural to bicultural

The construction of national identity in New Zealand rests on a master narrative that presents the image of “a small nation punching above its weight.” The rhetorical emphasis on “smallness” serves to imbue the nation with distinct qualities. For one, New Zealand assumes moral traits that larger states lack, such as friendly, egalitarian, respectful, and tolerant of other cultures. Moreover, given its proven record of social and economic progress, New Zealand is evidently also more hardworking, resilient, and ingenious than larger states.

For many decades, the “small nation punching above its weight” master narrative had been dominated by a monocultural, Euro-centric perspective of the historical past (Hellmann Reference Hellmann2023). According to this perspective, it was Europeans who – through their actions – epitomized the attributes that define the nation. Key events include the arrival of Captain James Cook who, because of his ascent from humble origins to officer rank in the British Navy and his respect towards native cultures, is portrayed as the “prototype” New Zealander; the successful women’s suffrage petition of the 1890s, which is collectively remembered as evidence of the nation’s egalitarianism and socio-political ingenuity; and the World War I battle of Gallipoli, in which ANZAC soldiers defended democracy against the tyrannical Central Powers. In line with these themes, annual official commemorations of the Treaty of Waitangi became firmly institutionalized after the 1940 centennial. Through means of repeated celebrations, framings of Waitangi as “the cradle of the nation” and the Treaty as “the foundation of nationhood” came to dominate the popular understanding of New Zealand’s beginnings, fueling the mythology of a unified nation with “the best race relations in the world,” and concretizing the image of a respectful and tolerant nation (Orange Reference Orange2021, 221). There is not doubt that the colonial experience in New Zealand differed from that of other colonies – for example, neighboring Australia lacked a comparable treaty with its Indigenous peoples. However, as historian James Belich (Reference Belich2001, 190) explains, these differences were discursively magnified to construct New Zealand as “a paradise of racial harmony.”

Māori voices challenged the romanticized and state-sanctioned commemorations of the Treaty of Waitangi as early as the 1940s (Orange Reference Orange2021, ch. 5). Criticism became more intense from the 1960s onwards, driven by the so-called “Māori renaissance” movement, which itself was part of a global wave of civil rights and anti-colonial activism. Mainly through protest, Māori activists created powerful counter-narratives confronting the silences on which the Euro-centric interpretation of the Treaty of Waitangi rests (Bell and Russell Reference Bell and Russell2022, 29; Celermajer and Kidman Reference Celermajer and Kidman2012, 227). For one, the public voicing of grievances over the historical and continuing loss of ancestral land brought public attention to significant breaches of the Māori language text of te Tiriti o Waitangi by the colonial government – in particular, the guarantee that tribal leaders would retain total chieftainship (tino rangatiratanga) over their lands and all things of value (taonga katoa).Footnote 4 Moreover, protestors dragged into the open the violent history of the New Zealand Wars – “a series of British attempts to impose substantive, as against nominal, sovereignty” over the colony (Belich Reference Belich1986, 78) – and the subsequent large-scale confiscation of Māori land (raupatu).

The loss of land and experiences of historical injustice were not the only drivers for Māori protest mobilization. Governments’ “perennial push for assimilation” – for example, through education and housing policies – also provided an important “catalyst for the rising voice of Māori discontent” (Harris Reference Harris2004, 15). In other words, protest was also an effort to reverse decades of cultural marginalization, and reassert Māori language, culture, and identity.

Largely due to pressure from the growing Māori political and cultural movement, successive governments sought to set the relationship between Europeans (Pākehā) and Māori on a more bicultural footing. Broadly speaking, this shift towards greater biculturalism took place, and continues to take place, on three levels. To begin with, the Treaty of Waitangi came to be seen less as a historical document than an “ongoing social contract” (Bell Reference Bell2006, 257). A pivotal moment was the establishment of the Waitangi Tribunal in 1975. Although initially tasked only with investigating iwi (tribe) and hapū (sub-tribe) claims about Treaty breaches from 1975 onwards, additional legislation passed in 1985 empowered the Tribunal to also investigate historical grievances dating back to 1840. Also of significance was the 1987 “Lands” case judgement by the Court of Appeal, which recognized the Treaty as a “living document” that required the government to act in partnership with Māori, thus further embedding the Treaty in New Zealand’s legal and political framework.

At the same time, governments took steps to promote te reo Māori and Māori cultural practices. Te reo Māori was declared an official language in 1987 and then further revitalized through subsequent initiatives, such as the establishment of kura kaupapa Māori (Māori-language immersion schools) by means of the 1989 Education Act and the launch of Whakaata Māori (Māori Television) in 2004. Biculturalism also became evident in public institutions, as government departments and agencies adopted bilingual practices as well as Māori traditions – for example, by performing pōwhiri and whakatau (welcome ceremonies) at official functions.

Lastly, there have been efforts to incorporate Māori experiences of the historical past into the “punching above its weight” master narrative. Examples are plentiful: following designation as a public holiday in 1974, annual Waitangi Day celebrations refrained from pushing the idealized “one people” theme (Orange Reference Orange2021, ch. 6); commemorations of World War I began to include explicit recognition of Māori military service (Light Reference Light2022b, ch. 7; Smits Reference Smits, Wellings and Sumartojo2018); to mark the 250th anniversary of Cook’s landing in 2019, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage invited iwi to sail alongside a replica of the Endeavour in traditional double-hulled voyaging canoes (Meihana Reference Meihana2022); and a newly designed history curriculum for primary and secondary schools, rolled out in 2023, “points to the incorporation of multiple histories, rather than a singular national narrative to be told” (Bell and Russell Reference Bell and Russell2022, 30; emphasis added).

It needs to be stressed, however, that the issue of biculturalism remains a subject of public debate. Significant parts of society – in particular, older and politically conservative European New Zealanders – continue to cling to the monocultural construction of national identity, offering a ready constituency for political agitators stoking sentiments against the Treaty of Waitangi and the institutionalized promotion of Māori rights (Hellmann Reference Hellmann2023). This helps explain why “many conservative politicians have had some success in rallying sections of the New Zealand public behind the argument that Treaty claims have divided the nation and impeded the nation-building project” (Celermajer and Kidman Reference Celermajer and Kidman2012, 224). Perhaps the most widely cited example of anti-Treatyism is Don Brash’s 2004 Orewa speech, in which the then leader of the National Party railed against an “entrenched Treaty grievance industry” designed to create “a racially divided state.” More recently, in 2024, the minor ACT party introduced a bill to parliament that sought to redefine the principles of the Treaty of Waitangi and enshrine them in legislation. Party leader David Seymour vowed to end “division by race,” fulminating that misinterpretations of the Treaty’s meaning have given Māori special political and legal treatment over non-Māori citizens.

Meanwhile, Waitangi Tribunal reparations have not succeeded in suppressing Māori activism and protest. Whereas the Crown has used the Tribunal primarily to improve the economic position of Māori through financial settlements and considers these settlements “full and final,” many Māori see Treaty settlements as only the beginning of a much more substantial process of institutional reform, demanding that tikanga (Māori law), mātauranga Māori (Māori knowledge systems), and te Tiriti become part of the legal and constitutional system (Bargh Reference Bargh, Hayward and Wheen2012; Mutu Reference Mutu2019: 14). That is to say, from this perspective, current bicultural institutions and processes are seen as too superficial and even tokenistic, failing to fully honor the guarantee of tino rangatiratanga made in te Tiriti.

In particular, Māori protestors have claimed Waitangi Day as “a day where the foundational agreement of what would become the New Zealand nation-state is reflected upon, and placed in front of our signatory partner (the government) to remind them of what was promised” (Ngata Reference Ngata2020). At the conservative end of the political spectrum, protests on Waitangi Day have been met with criticism. For example, in 2017, then Prime Minister Bill English stated that “A lot of New Zealanders cringe a bit on Waitangi Day […] And I’m pretty keen that we have a day where we are proud of it […] There was a time when the protest at Waitangi was nationally relevant […] That time has passed because we have made so much progress on relations with Māori.” Against the background of regular Māori protest rallies, there have even been calls from among Pākehā segments of society to replace Waitangi Day with ANZAC Day as the national holiday (O’Malley and Kidman Reference O’Malley, Kidman, Kidman, O’Malley, MacDonald, Roa and Wallis2022a, 88) – and, indeed, many already consider the latter as the de facto national day (Light Reference Light2022b).

Collective memories of the New Zealand Wars play a significant role in the Māori self-determination movement, as they are deeply intertwined with issues of historical injustice, political sovereignty, and cultural revival. However, while Māori activists have doubtlessly been at the forefront of challenging and reinterpreting the master narrative of the nation’s past, it is important to highlight that historical revisionism has also manifested itself in other forms. Most importantly, there is a growing body of critical historiography that seeks to contribute to a growing awareness and a better understanding of the New Zealand Wars (e.g., Belich Reference Belich1986; Keenan Reference Keenan2021; O’Malley Reference O’Malley2019; Walker Reference Walker2004). Moreover, films and documentaries explore this particular episode of colonial violence and its lasting consequences. Notable examples include Ka Whawhai Tonu (2024), River Queen (2005), and The New Zealand Wars (1998) – a TV documentary presented by historian James Belich.

Nevertheless, despite the broad wave of historical revisionism, and despite the fact that state-sponsored public history has doubtlessly become more inclusive of Māori experiences in recent years, official memory-making of the New Zealand Wars continues to be pervaded by “awkward silences and omissions” (Kidman and O’Malley Reference O’Malley, Kidman, Kidman, O’Malley, MacDonald, Roa and Wallis2022b, 11). Avoidance of the dark past can be discerned in many areas of public history. For example, the Treaty of Waitangi exhibit at the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa – which was the target of carefully choreographed protest action in December 2023 – downplays the New Zealand Wars and subsequent land confiscations, focusing instead on presenting the relationship between Pākehā and Māori as “reconciled” (Attwood Reference Attwood2013; Kidman Reference Kidman, Epstein and Peck2018), while the New Zealand Wars exhibition at the Auckland War Memorial Museum merely confronts visitors with a “clutter” of objects, without much context or narrative structure (Light Reference Light2022a).Footnote 5 In 2016, the National Party government under John Key – in response to a petition submitted by students from Ōtorohanga College – announced the creation of an annual day of commemoration (Rā Maumahara) to mark the New Zealand Wars. Yet, so far, commemorative events have failed to gain broad public attention, not least because Rā Maumahara does not have the status of a public holiday and because subsequent governments have not provided enough financial or other support to ensure that commemorations can be organized at the national level.

Viewed through the lens of national identity, these silences are not entirely unexpected. The New Zealand Wars – and the fraught histories of European settler militias and British colonial troops invading Māori lands – challenge the master narrative of New Zealand as a tolerant and respectful nation. As historian Vincent O’Malley (Reference O’Malley2015, 92) concurs, the New Zealand Wars “do not fit within a comfortable nation-building framework … Who wants troubling introspection when we can have heart-warming patriotism instead?” During the public debate over the new history curriculum, some conservative politicians even articulated this line of thought out loud. For example, National Party education spokesperson Paul Goldsmith argued that the history of colonial violence and conflict was unsuitable to foster positive identification with the nation, and instead thought it better for history students to consider such questions as, “How did we make a living as a country? How, in such a short space of time, did we attain one of the highest living standards in the world?”

This sketch of public history would not be complete without pointing out that Waitangi Tribunal settlements have not posed a serious threat to the master narrative. Even though the settlement process requires that Māori claimants and the Crown government produce a joint account of the historical past, there are only limited opportunities for the wider public to access these officially ratified reinterpretations of history. What is more, because settlements are generally negotiated between the Crown and individual iwi or hapū, the Tribunal works mainly in the context of local histories, not in the context of national history. Related to this, the Crown has never offered a national apology to Māori; instead, the Crown has only ever acknowledged its wrongs in relation to iwi and hapū (Celermajer and Kidman Reference Celermajer and Kidman2012; Hickey Reference Hickey, Hayward and Wheen2012).

To sum up, the “punching above its weight” master narrative – which had long exclusively been told from the European settler perspective – has adopted a more bicultural tone, with the Treaty of Waitangi serving as the central point of reference. However, the symbolic power of the Treaty is by no means consolidated. While Māori activists understand te Tiriti as the legal basis for affirming Māori rights to self-determination and addressing past injustices, and thus continue to expose current and historical violations of its provisions, a large portion of settler society not only resists the expansion of Māori rights and views biculturalism as creating divisions, but also believes that “incessant” protests and legal appeals have “ruined” the Treaty as an object of positive collective identification.

It is these tensions that provide the context for the redevelopment of the Waitangi Treaty Grounds in the Bay of Islands around the 175th anniversary of the Treaty’s signing in 2015. Out of the total costs of NZ$14 million, NZ$10 million were spent on building a state-of-the-art museum to house the newly designed Ko Waitangi Tēnei: This is Waitangi exhibition, the title of which refers to a significant Waitangi Tribunal report released in 2011.Footnote 6 As Waitangi National Trust chief executive Greg McManus explained, “many people react negatively to the word ‘Waitangi’ […] The point is to arm people with a little more knowledge. I want people to leave Waitangi as better New Zealanders.”Footnote 7 Up until the 2016 opening of Ko Waitangi Tēnei, the Treaty Grounds had featured only a small makeshift exhibition in the so-called Treaty House – a cottage built by James Busby, Britain’s consular representative to New Zealand from 1833 to 1840.

Ko Waitangi Tēnei: narrating the nation as a long arduous quest

“Welcome to Waitangi, Te Pitowhenua, the birthplace of our nation, New Zealand.” These are the words that greet visitors as they enter the permanent exhibition on the Waitangi Treaty Grounds. The seven sections that make up Ko Waitangi Tēnei narrate the events leading up to the Treaty and subsequent developments in a chronological fashion, starting with the discovery of Aotearoa by Oceanic navigators and ending with contemporary debates about the role of the Treaty in New Zealand society (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Exhibition layout.

The first section titled Navigators chronicles how Māori ancestors from Oceania and later Europeans arrived on the shores of Aotearoa New Zealand, and how these two cultures encountered each other for the first time. Visitors are led through a narrow space that is lined with image-heavy panels: while panels on the left depict Māori seafarers and rangatira (tribal chiefs), panels on the right focus on European explorers, including Abel Tasman, James Cook, and Marion du Fresne (Figure 2). Textual and visual clues make it quite clear to visitors that they are about to be immersed in a narrative that follows the quest masterplot.

Figure 2. The Navigators section.

Source: Photograph by Sam Hartnett (top); British Library, MS 15508 (bottom).

Boiled down to its essence, the quest masterplot unfolds as follows (see Booker Reference Booker2004, ch. 4): the main protagonist sets out on a long, dangerous journey across alien terrain in search of a priceless goal. The journey, however, turns out to be only the first part of the tale. When the hero arrives within sight of their goal, they have to undergo a last series of tests to prove that they are truly worthy of the prize. Throughout the quest, the hero and their companions display weakness and make foolish errors that threaten to prevent them from reaching the goal. What ultimately allows the hero to succeed is that they gradually learn from their mistakes and arrive at a state where they no longer repeat their mistakes.

While the entire Navigators section contributes to setting the stage for the quest masterplot, it is one text passage in particular that helps guide visitor expectations:

All those who come to this country have to cross a vast stretch of water to get here.

Boldness and great navigational skill brought Māori to these shores, then Europeans, hundreds of years later. Now two peoples had to navigate the unknown waters of a relationship.

Each had to come to terms with the other to get what they wanted.

This short passage perfectly reflects the essence of the quest masterplot: after making it across the ocean to Aotearoa New Zealand, the protagonists realize that this was only the first part of their adventure and that there is a much greater prize than finding new lands – namely, mutual exchange between Māori and Europeans. This new prize is visually captured in a drawing by Tupaia – a Tahitian navigator and high priest who joined Cook’s crew during a stopover – displayed at the far end of the first section (Figure 2). The drawing shows an unnamed Māori trading a crayfish with Joseph Banks, a botanist on board the Endeavour. The accompanying text explains, “both have something the other wants, and they are in the process of exchange.”

As the section cited earlier spells out, the protagonists have to undergo one last test to get the prize: navigating “the unknown waters of a relationship.” But what does it take to conquer the ultimate challenge? The first section implicitly answers this question by drawing a sharp distinction between the British and the French. When describing the first meeting between Māori and Cook the narrator notes that “each strove to understand each other.” In contrast, the panel on the first Māori-French encounter observes that

misunderstandings, including the visitors’ fatal ignorance of tapu (forbidden behaviour), led to mayhem. Du Fresne and 26 other visitors were killed. Hundreds of Māori were killed by the French in defence and reprisal.

This differentiation between the British and the French – which relies on a highly selective reading of history that understates the violence that accompanied Cook’s first journey to Aotearoa New ZealandFootnote 8 – sets up the main semantic axes for the characterization of actors. Specifically, for the remainder of the narrative, characters are portrayed as respectful and tolerant or disrespectful and intolerant. Only if characters do their best to be respectful and tolerant can they make the intercultural relationship work and complete the quest.

The first section of the exhibition not only sets the plot and characterizes the protagonists, but it also introduces the narrator. As already evidenced by the text passages cited, the story of the Treaty of Waitangi is narrated from a third-person perspective. The choice of a heterodiegetic narrator is understandable, as it creates a sense of the narrative being told from a neutral standpoint, without siding with either Pākehā or Māori. Moreover, the narrator is omniscient, able to reveal characters’ inner thoughts – for example, visitors are told that “Māori too were intrigued by these encounters” or that “Māori saw value in European materials, such as fabric.” On the covert-overt spectrum, the narrator sits closer to the latter end, which is reflected in the frequent use of appraisal rhetoric (Ravelli Reference Ravelli2006, 92), such as “bold navigators” or “great navigational skill.”

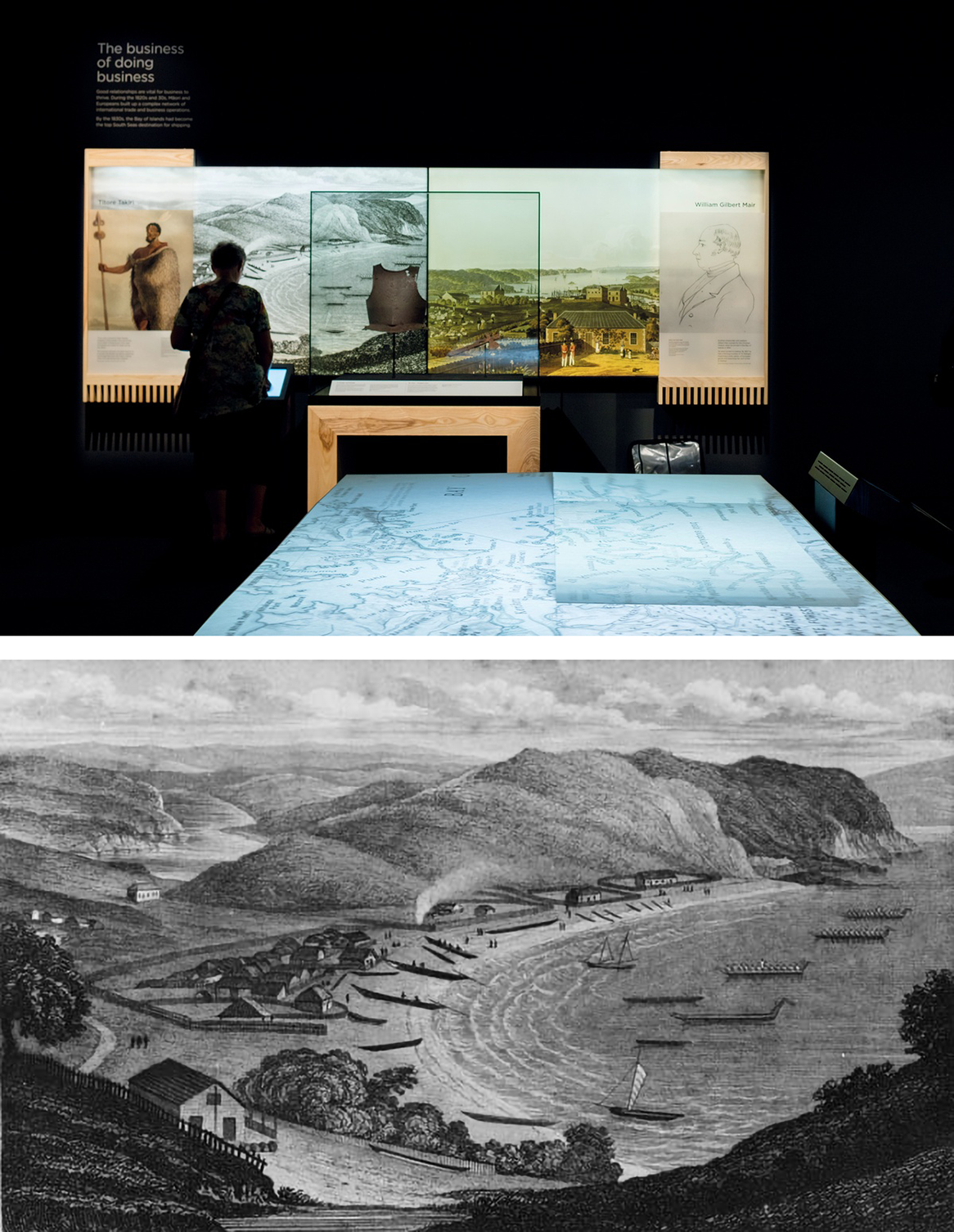

Picking up on the theme of Tupaia’s drawing, the introductory panel in the Go-betweens section describes how “trade and adventure fuelled the exchange of language and ideas,” and how “lives began to mingle.” To support this claim, the second exhibition section focuses on five pairs of prominent individuals – one Māori, one British – and recounts the relationship that connects them. Hence, phrased in narratological terminology, the narrator employs repetitive storytelling – that is, narrating the same event (the development of trade and other relationships between Māori and the British) through multiple experiences.

Each pair of individuals is presented in the same way: a portrait at either side, with material objects placed in the middle. More precisely, the exhibited objects are valuable items that were gifted between Māori and Europeans. For example, the display of the relationship between Titore (a rangatira of the Ngāpuhi tribe) and Gilbert Mair (a Scottish merchant trader) centers around a suit of armor that was gifted to Titore by King William IV (see Figure 3). Rooted in the general ability of material museum objects “to materialise, concretise, represent, or symbolise ideas and memories” (Hooper-Greenhill Reference Hooper-Greenhill2000, 111), these objects do thus not only help illustrate the friendships and personal relationships that developed between Māori and the British, but they also serve to give concrete form to the “respectful” and “tolerant” attributes that are key to the narratological characterization of actors: How else could these friendships have developed, if not through mutual respect and tolerance? More fundamentally, gifts are – as we will see later on – a recurring object throughout the exhibition, thereby functioning as tangible “evidence” of the nation’s respectful and tolerant nature.

Figure 3. The Go-betweens section.

Source: Photograph by Sam Hartnett (top); Alexander Turnbull Library, PUBL-0115-1-front (bottom).

The traffic flow in the Go-betweens part is much less prescribed than in the earlier Navigators section.Footnote 9 The five displays are organized in a radial rather than a linear layout, with an interactive digital map at the center (see Figure 1), which allows visitors to move about in their own way and at their own pace.Footnote 10 Arguably, the radial format is meant to enable a “bottom-up exploration” (Hourston Hanks Reference Hourston Hanks, Macleod, Hanks and Hale2012, 29) of the various personal gifts, thereby promoting a close and empathic relationship between visitors and characters.

What is also notable in the Go-betweens chapter of the narrative is that the characterization of the setting changes. Whereas Navigators describes Aotearoa New Zealand as an away-from-home space in the “far south-western corner of Moananui-a-Kiwa” and “the Southern Pacific Ocean,” the second section evokes comforting connotations of home. The main means for characterizing the setting as home are visual depictions of Māori-European settlements in the first half of the 1800s. One example is an etching of Kororāreka (Russell) by Joel Samuel Polack, which shows Māori and Europeans living alongside peacefully, each group with their own distinctive houses and boats (Figure 3).

The portrayal of early Māori-European relations in the Go-betweens chapter is, however, overly romanticized, glossing over episodic violent conflict between the two cultures, such as the burning of the Boyd (1809) or the Elizabeth incident (1830). Likewise, the section does not – except for minor references hidden away in the digital map – make any reference to the fact that trade with Europeans fueled the influx of firearms and the so-called “musket wars” between Māori tribes, which resulted in thousands of casualties in the first third of the 1800s. While Go-betweens does point to cultural differences in relation to land tenure and use, this mainly functions as a prolepsis, building suspense by hinting at the conflict to come:

Māori and the British had very different ways of thinking about land. For Māori, the tribal groups belonged to the whenua (land), and had responsibilities for it. For the British, land was a commodity that individuals could own and trade.

When the two peoples began bringing their worlds together, these differences were bound to create tensions.

The subsequent Meeting ground section focuses on the signing of the Treaty of Waitangi. It is here that the omniscient narrator takes on an important role, revealing the thinking that led Māori and the British to “sign up to an agreement to live together in this land.” For example, visitors learn from a number of explanation panels (Ravelli Reference Ravelli2006, 21-22) that Māori hoped “to get support in dealing with the lawless behaviour of British people in their communities” and that they “were concerned too about threats to their independence from other foreign visitors, especially the French.”

The section features a minimalist reconstruction of the tent in which the Treaty was debated and signed. Inside the tent, visitors can watch part of the TV documentary What really happened – Waitangi (Figure 4).Footnote 11 This immersive surround-scape “transports” the visitor back to 1840, giving them the feeling of being “part of” the Treaty negotiations and shifting their role from an onlooker to an insider (cf. Roppola Reference Roppola2012, 171-172). The exhibition designers sought to further augment this insider effect by lining the tent walls with portraits and personal objects of individuals who were present at the Treaty signing in 1840. Through text panels, the omniscient narrator helps visitors understand what these individuals thought about the Treaty, which – in combination with the TV documentary – frames the event of February 6 as a rational debate between equals. Moreover, the film also helps to slow down the flow rate of the exhibition, with implications for narrative duration: whereas previous parts were narrated as a summary, the Treaty negotiations are narrated as a scene, thus signaling that this is a particular important chapter of the narrative.Footnote 12

Figure 4. The Meeting ground section.

Source: Screenshot from the What really happened – Waitangi documentary.

In the subsequent Documents room, the narration then even slows down to a pause. This section is sparse on text and narration, focusing visitors’ attention instead on a replica of the Treaty exhibited in illuminated display cases (Figure 5). One of the few text panels informs visitors that “there are important differences of wording between the Māori version, which most rangatira signed, and the English version.” It is also worth noting that, similar to earlier sections, the Documents room uses material objects to illustrate “the continuing gift exchange between the Crown and Māori,” including a korowai (tasseled cloak) presented to Queen Victoria by a Māori delegation in 1863 and a portrait of Queen Victoria gifted to the Waitangi National Trust in 1970.

Figure 5. The Documents room.

Source: Photograph by Sam Hartnett.

By pausing the narrative and placing the Treaty in a space that is comparatively larger than other sections of the exhibition (Figure 1), the museum designers employ the inner sanctum subtype of linear spatial sequencing. This particular traffic flow design asks visitors to see the Treaty of Waitangi as a unique and exceptional document – a reading that is further encouraged by omitting an important historical fact: Britain and other European colonial powers regularly concluded treaties with Indigenous peoples to obtain overseas territories, mainly because cession through treaty enjoyed greater legitimacy than other bases for title, such as conquest, discovery, or occupation. Importantly, more “civilized” Indigenous peoples were often viewed as more deserving of treaty relationships, while groups perceived to lack “sophisticated” social organization – such as the First Nations peoples of Australia – were typically dismissed as unworthy of formal agreements (Belmessous Reference Belmessous, Hickford and Jones2018).

The Documents room is thus another example of the selectivity with which Ko Waitangi Tēnei narrates the historical past. Here, selectivity not only serves to construct the Treaty as a uniquely consensual means of instituting colonial rule, but it also draws a symbolic map of the wider narrative world, distinguishing British colonialism in New Zealand from more oppressive and violent experiences of colonization elsewhere. In other words, the constructed uniqueness of the Treaty implies a comparison between (tolerant) New Zealand and other (less tolerant) places.

The narrative picks up speed again in the Striving for balance part of the exhibition, which recounts the violent events of the New Zealand Wars. It is in this section that we begin to see why the museum designers chose to narrate the story of the Treaty of Waitangi in the way they did. A text panel titled “Colonial business as usual,” which visitors encounter early on in the section, is particularly revealing and thus worth quoting in length:

Governor Hobson had to attend to over 60 separate items in his instructions for getting the colony of New Zealand going […]

They were pretty much standard instructions, with no exception made for the terms of the Treaty of Waitangi […]

Britain was well used to setting up colonies in its worldwide Empire. Officials immediately began to apply their own culture of social control – laws, rules and regulations, made up in offices and issued on paper. What other way was there of getting things done?

What happens in this text passage is that the quest masterplot and the constructed exceptionalism of the Treaty come together to make that claim that – similar to the oceans that earlier seafarers had to cross to get to Aotearoa New Zealand – the Treaty was unknown, foreign terrain. Moreover, as is typical for the quest narrative arc, the protagonists make foolish mistakes, which threatens to derail the search for the prize. Specifically, the British resort to the “standard” instruments for imposing colonial rule, forgetting that it was the values of respect and tolerance that had gotten them this far in their quest.

Hence, similar to French attempts to colonize New Zealand in the late 1700s, British “colonial business as usual” is characterized as disrespectful and intolerant of Māori norms and practices. “Conflict arose,” the narrator explains, “when colonial rules encroached on Māori interests.” Linking back to the prolepsis in the Go-betweens section, differing orientations towards land are singled out as the main reason for the outbreak of conflict between Māori and the Crown. For example, as one text panel states:

Land deals were a source of discontent with the Government from early on. Tribal leaders were dissatisfied with government control of land sales. They also objected to the resale of land by new settlers – treating land like a commodity for trade.

In terms of its spatial layout, Striving for balance is designed to create an almost claustrophobic sense of tension and unease, as visitors have to navigate a very narrow space and a “hairpin turn” halfway through the section (Figure 1). Again, as in previous sections, gifted objects feature heavily, telling visitors that – amidst the violence of the New Zealand Wars – there were individuals and groups on both sides who continued to promote the values of respect and tolerance enshrined in the Treaty. Examples include a silver cup presented to Tāmati Wāka Nene (a Ngāpuhi leader) by Queen Victoria in 1861 and a Māori carved staff gifted to Robert Wynyard (a senior colonial administrator) in 1858. These gifts are spatially juxtaposed with numerous muskets and melee weapons, which symbolize the opposite ends of the semantic axes used for the characterization of actors: disrespectful and intolerant.

As visitors follow along the prescribed circulation path, they find that the Test of strength section offers a resolution to the tensions of the New Zealand Wars. Although the section begins with a detailed account of how Māori lost much of their land through forceful post-war confiscations and the introduction of private property rights, the narrator then recounts how, over the following decades, Māori politicians and activists engaged in organized efforts “to secure equality in the relationship between Māori and the British Crown,” which resulted in the establishment of the Waitangi Tribunal in 1975 and the extension of its authority ten years later. In the quest narrative, the Waitangi Tribunal marks the point at which the protagonists have learned from their mistakes and vow not to make the same mistakes again. But the protagonists’ commitment to respect and tolerance does not stop there. By vesting the Tribunal with the power to investigate historical claims, the protagonists also commit to righting their wrongs of the past, which the narrator commends as “the way to good relationships.” These qualities are then projected onto the nation as a whole – most evidently through the final words in an eight-minute-long film that is projected in the Test of strength section:

The story of the Treaty’s creation and its long journey to recognition has informed much of New Zealand’s unique identity. Our values of respect, equality and cooperation can be traced back here, to this place and to this document.

However, this is not the end of the story. Rather, the final Place of Waitangi section, which retells the history of the Treaty Grounds from their origins as a gift (see fn. 7) to the present day, suggests that nation building is an ongoing quest. Waitangi is described as a meeting place to “mark, celebrate, debate and enjoy the unique relationship that is the basis of the nation.” Before visitors exit the exhibition, they walk through a corridor that is lined with large panels featuring quotes about the meaning of the Treaty and photographic portraits of ordinary New Zealanders. Although visitors are not addressed directly, they are still implicitly invited to reflect on how they themselves feel about the Treaty, thus making them feel part of the debate – and part of the nation.

Conclusion

Driven primarily by Māori rights and cultural activism, the construction of national identity in Aotearoa New Zealand has taken a bicultural turn in recent decades. Anchored in the Treaty of Waitangi as a “living document,” biculturalism revolves around reconciliation for past injustices, cultural recognition, and weaving Māori historical experiences into the “punching above its weight” master narrative. However, the bicultural identity project is getting squeezed from two sides. On one side, Māori groups continue to lament historical and ongoing violations of te Tiriti o Waitangi, which threatens the image of a tolerant and respectful nation. On the other, significant parts of the European demographic oppose biculturalism, based on the belief that Māori political autonomy and the settlement of historical grievances divide the nation.

While I was writing this article, the debate over biculturalism intensified dramatically. After the election in October 2023, a new right-of-center government – formed by National, ACT, and New Zealand First – implemented policies aimed at limiting the use of te reo Māori within the public service and took steps to dismantle several Māori-focused initiatives, such as the Māori Health Authority (Te Aka Whai Ora). Moreover, in September 2024, ACT – with the support of the two other coalition parties – introduced the aforementioned Treaty Principles Bill, in a step that sparked significant public outcry. In November, driven by the aim to “kill the bill” and safeguard Māori rights enshrined in te Tiriti, Māori activists organized te Hīkoi mō te Tiriti (the March for the Treaty), which commenced at Cape Reinga, the northernmost point of New Zealand, and spanned nine days, covering various towns and cities en route to Wellington (Te Whanganui-a-Tara). Tens of thousands of people marched in the capital, making it the largest protest rally to descend on parliament in New Zealand history.

Against this background of conflict over biculturalism, my article applied a comprehensive narratological framework to investigate how Ko Waitangi Tēnei narrates the history of the Treaty of Waitangi. Acknowledging that critical scholarship has a tendency to zoom in exclusively on negative aspects when analyzing museums of colonial history (McCarthy Reference McCarthy2009), it is important to emphasize that the exhibition makes more space for Māori experiences of the historical past – especially in relation to the New Zealand Wars – than the Euro-centric narratives that had long dominated collective memory. However, at a deeper analytical level, it becomes clear that Ko Waitangi Tēnei sidesteps complicating questions about the New Zealand Wars. Specifically, the analysis revealed that the exhibition emplots events along the quest masterplot and characterizes actors along a tolerant-intolerant axis. Seen through the quest masterplot, the Treaty becomes “unknown terrain” and characters are expected to make foolish mistakes that threaten to bring the adventure to an end. Put differently, Ko Waitangi Tēnei claims that the New Zealand Wars happened because the Treaty was a never-before-seen mode of instituting colonial rule, which meant that actors erroneously fell back on “standard” ways of doing things, rather than applying the lessons of tolerance that they had learned in earlier parts of their quest. The exhibition constructs the Treaty as an exceptional document not only by placing the replica in the “inner sanctum” of the museum and slowing the narrative down to a pause, but also by giving a highly selective recounting of history that conceals the regularity with which European colonial powers relied on treaties to acquire overseas territories.

Ko Waitangi Tēnei thus wants visitors to leave the museum thinking that the New Zealand Wars did not reveal the true essence of the nation. This intended reading is further encouraged by framing material objects as the physical manifestation of the nation’s tolerance and respectfulness. As the analysis shows, the theme of gift exchange between Māori and the British provides a connective thread throughout the narrative, even through the violent chapter of the New Zealand Wars. It is these objects, visitors are told, that embody the essential qualities of the nation. Moreover, it is because of these qualities that New Zealanders tasked the Waitangi Tribunal with remedying the wrongs committed in the past. Hence, against assertions made by conservative politicians that the Treaty claims process is divisive, the Ko Waitangi Tēnei exhibition narrates the Tribunal not only as a reflection of national character, but also as an institution that brings the nation together.

Hence, what the narratological analysis indicates is that the narrative of the Ko Waitangi Tēnei exhibition is purposefully crafted to safeguard the “small nation punching above its weight” master narrative, and the Treaty of Waitangi as its main symbolic reference point, against critical counter-storytelling. This narrative is not only a highly selective reconstruction of the historical past, but it also presents the violence of the New Zealand Wars as the “natural” outcome of the (supposedly exceptional) contract-based mode of colonization. The exhibition thus obscures the underlying causes of the New Zealand Wars, giving visitors little opportunity to consider why European settler militias and British colonial troops attacked Māori communities.

The naturalization of the New Zealand Wars as a normal and unquestionable part of the quest narrative arc stands in sharp contrast to a growing body of historiographical research that examines the origins of the New Zealand Wars. For example, Belich (Reference Belich1986) highlights that British colonial attitudes, which positioned Māori as racially and culturally inferior, play an important role in explaining military aggression, while Walker argues that the New Zealand Wars have to be understood in the context of European imperial expansionism, simply replicating “the colonial experience of African tribes and the Indians of the American continent” (Reference Walker2004, 96). The Ko Waitangi Tēnei exhibition on the Waitangi Treaty Grounds is thus another example of how state-sponsored public history in Aotearoa New Zealand fails to engage in meaningful reflection about the violence of the colonial past.

In broader terms, the article focuses attention on the specific storytelling techniques that museums have available to construct national identity in the face of difficult histories. While particular emphasis was placed on masterplots, the case study of Ko Waitangi Tēnei illustrates that emplotment alone cannot carry a narrative. Rather, emplotment has to be analyzed in conjunction with other storytelling techniques such as characterization, tense, and narrator. However, only future applications will show whether the framework proposed at the outset of this article needs conceptual adjustments or other improvements. Such applications should go beyond cases of settler colonialism and deploy the framework to a broader range of difficult histories, which may include genocides and politicides, the end of dictatorships, and the fall of communism.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Sam Hartnett for permission to use his photographs of the museum on the Waitangi Treaty Grounds. I am also grateful to the three anonymous reviewers for their constructive feedback on earlier drafts.

Disclosure

None.