In Holmesville, Mississippi, sometime in or before 1857, an enslaved blacksmith named Ned invented a labor-saving device that could prepare both sides of a cotton ridge for seeding.Footnote 1 Ned was enslaved by Oscar J. E. Stuart, a lawyer and planter who, claiming legal entitlement to “the fruits of the labor of the slave both intellectual, and manual,” filed a patent application for Ned’s “double Cotton Scraper” (Letter to Jacob Thompson [25 Aug. 1857]). Although confident in his claim to human property, Stuart feared that he might nonetheless be found ineligible to hold the intellectual property rights to Ned’s invention because the Patent Act of 1836 required that patentees make an oath certifying that they were “the original and first inventor” (United States 119). Stuart argued in a letter to the Mississippi senator John Quitman that because “no one could rationally doubt” that the inventions of slaves were the property of the slave owner, the law should permit him to appropriate Ned’s designs as his own intellectual property even if he was not the original and first inventor, as required by the Patent Act (qtd. in Frye 191).Footnote 2 The commissioner of patents, Joseph Holt, disagreed. Holt rejected the application not on the grounds of originality or firstness but on the basis that in Dred Scott v. Sandford, decided in March 1857, the Supreme Court had ruled that free and enslaved African Americans were not citizens of the United States and thus could not file a patent application. Holt’s bureaucratic diktat not only barred all slave owners from patenting their slaves’ inventions but also excluded free African Americans from the legal protections afforded by the patent. Because neither Stuart, who was not the inventor, nor Ned, whom the state considered a noncitizen, could file the patent application, Holt reflected that the case represented “a casus omissus,” a gap in the existing law (Letter).

This gap in antebellum patent law reveals not so much a legal oversight to be remedied—though Stuart tried to do just that when he petitioned Congress to amend the Patent Act to allow for the patenting of enslaved people’s inventions—as a deeper fault line in the elementary racial structure of mediation. At the root of this casus omissus was the antebellum assumption that slaves were unable to invent technical means for transforming their environments. As Stuart surmised in his petition to Congress, “At the time the Patent laws were enacted…the opinion was equally universal, that a negro slave, never could invent anything of a useful character” (qtd. in Frye 204). Or, as Aristotle pronounces—and the sociologist of slavery George Fitzhugh reiterates in the same year that Stuart tried to patent Ned’s invention—“He who is capable of foreseeing by his intellect, is naturally a master; he who is able to execute with his body what another contrives, is naturally a slave” (238). Parallel to the more familiar notion that slaves could not own property because they were property was the idea that slaves were incapable of inventing means because they were themselves quasi-agential means.

To explicate the philosophical premises of this racial fiction, which circulated well beyond the domain of law, I turn to influential work in media studies that has traced the discursive production of “means,” “media,” and “mediation” as a web of interrelated concepts. Recent contributions to media studies that have broadened the disciplinary boundaries of the field to include all forms of communication—whether “a love letter, whale sonar, [or] a poem scribbled in the sand”—have prompted concurrent efforts to disentangle the ambiguities of the concept of media, including its noncommunicational meanings, since the term has become so capacious (Shechtman 654). John Guillory, for example, in his intellectual history that stretches from Aristotle to John Locke to Raymond Williams, calls attention to media’s various cognates, including mediation, which “would seem to be everywhere implied by the operation of a technical medium,” but which was more often used before the twentieth century to refer to the process whereby “different realms, persons, objects, or terms are brought into relation” (341, 342). Indispensable for its historical breadth, Guillory’s genealogy nonetheless overlooks the importance of the nineteenth-century discourse of mediation for the shifting formulations of a racialized humanism. While analyses of race in relation to specific media technologies are a mainstay of contemporary media studies, there have been far fewer excavations of the racialized premises of the concept of mediation itself. A notable exception, Armond Towns’s Black media philosophy, argues that the McLuhanite notion that “media are extensions of man” has tended to figure blackness as one of these media extensions, as “exist[ing] to serve a function by and for others” (853). If genealogies of mediation have been developed in response to frustratingly presentist conceptions of media, then these genealogies themselves must be revised to account for the racial and capitalist foundations of media studies’ conceptual frameworks and terms.

This article contributes to this genealogical task by embedding media histories in the history of racial capitalism to theorize what I call media vita—a racialized mode of reasoning, a system for evaluating and conceptualizing social relations, and an emergent way of experiencing life as mediated.Footnote 3 I argue that having the capacity for mediation—that is, the power to develop and implement means for bringing realms, persons, terms, or objects into relation—was, as Brenna Bhandar writes with respect to the capacity for ownership and appropriation, a nineteenth-century prerequisite “for attaining the status of the proper subject of modern law” (5). This requirement for full subjecthood also circulates in media studies today. The German media theorist Cornelia Vismann, for example, has remarked that “a plough drawing a line in the ground…produces the subject, who will then claim mastery over both the tool and the action associated with it” (84). For Vismann, the lines that a plow like Ned’s would have inscribed on a cotton field simultaneously distinguish and put into relation the cultivated lands and the wilds, the owner and the owned, the human and its others. Instead of taking up this presumption and treating acts of mediation as evidence of a universal humanity denied during slavery, I turn to the overlapping nineteenth-century regimes of property, race, and invention to examine how new notions of subjectivity were coming into focus precisely through the denial of the enslaved person’s power over the invention of means. Media vita names precisely this comprehensive worldview in which social groups are differentiated according to their capacities for mediation.Footnote 4

I begin by contextualizing patent law within nineteenth-century legal and literary culture to illustrate how slavery and the patent system interfaced during a historical period in which liberal reformers and capitalist industrialists fought over the scope of an inventor’s property rights while, at the same time, enslaved people and abolitionists challenged the extent to which people could be property. I then turn to the inventor Norbert Rillieux and the abolitionist Solomon Northup to examine their divergent assessments of the patent system and its underlying premises of mediation. Whereas Rillieux, a member of the New Orleans gens de couleur libre, or free people of color, accessed the patent system to claim intellectual property rights over a labor-saving invention that not only served the economic interests of the planter class but also encapsulated the distinctive characteristics of media vita, Northup, a free African American from upstate New York, reworked the patent form—including its nonfigurative mode of specification for new devices, its transition between grammatical voices, and its unique stimulus to contemplation—for incorporation into literary form in order to critique the conception of subjectivity on which media vita is premised. Whether through the bureaucratic patent application process or the appropriation of the patent’s formal attributes in a literary narrative, Rillieux and Northup leverage the patent form to analyze the production of means under racial capitalism.

A Patent History

Compared with the legal protections for property in land, goods, or even people, the patent is a relative latecomer. In 1472, the first patent statute was enacted in Venice, Italy—one of the proposed birthplaces of European capitalism—but patents only became a major tool for capitalist development in sixteenth-century England. During the Tudor period, patents were not considered private property rights but instead were bestowed as royal privileges that established a monopoly for a limited number of years for the purpose of encouraging domestic economic production. Importers or introducers of foreign productive knowledge could also receive patents, as when Edward VI granted a letter patent to Henry Smyth in 1552 for “brode glasse of like fasshion and goodes to that which is commonly called Normandy glasse which shall…be a great commoditie to our said realme and dominions” (qtd. in Mossoff 1260). This notion of promoting scientific and industrial advancement, instead of protecting an individual’s private property rights, is reflected in the US Constitution’s clause on intellectual property, which gives Congress the power “[t]o promote the Progress of Science and useful Arts, by securing for limited Times to Authors and Inventors the exclusive Right to their respective Writings and Discoveries” (U.S. Constitution, art. 1, sec. 8). What distinguishes the intellectual property system from laws that protect tangible property, however, is that the holder of intellectual property rights such as those conferred by a patent does not own any specific, material thing. Instead, patentees hold monopoly control over the idea for an instrument or a method of production, from which they can profit directly through manufacture or through the sale and licensing of their designs to others. Only after the spread of natural rights philosophy in the late seventeenth century did patents come to be popularly understood as legal protection for “the fruits of the mind,” as Stuart put it, entailing a property right analogous to that arising from the “labor of the hands” (Letter to Jacob Thompson [18 Dec. 1857]).

Yet this notion that intellectual property sprouts as if naturally from the laboring mind conflicts with the reality of the patent system. If, as Locke claimed, mixing labor with the materials of nature is the chemical formula for personal property, then the patent, which gives property rights to the patentee for only a limited number of years, has a built-in expiration date that contradicts economic liberalism’s foundational belief that “the labour of [the laborer’s] body, and the work of his hands, we may say, are properly his” (245). According to patent law, the work of the mind is properly the patentee’s, but (in the mid–nineteenth century) only for about fourteen years. While Stuart’s attempt to patent Ned’s inventions reveals a casus omissus in patent law when it encounters the laws of slavery, patent law itself reveals a gap in the law of property, or what the intellectual historian Oren Bracha identifies as a “gap between the abstract image of property rights in inventions and its translation into practical terms” (238). For example, an 1806 petition to Congress claimed that if “mental property…is as justly and bona fide the property of those who thus acquire it as any real or personal property can be,” then it stands to reason that the patent’s term should, if not obtain in perpetuity, then at least cover “the life of the inventor, and his heirs and assigns, to the third generation; or for fifty years certain” (qtd. in Bracha 238). Bracha notes in his analysis of this petition that “the common principle of natural property rights in mental labor” in the United States often came into conflict with “the economic pressures that shaped patent doctrine” and greatly limited the duration of intellectual property rights (239, 240). In this sense, as the economic historian Zorina B. Khan has argued, the patent is an ambiguous form of property protection that seemed to many in the nineteenth century like a natural right to “mental property” that the state must protect as well as a “reward,” as Chief Justice John Marshall called it, “stipulated for the exertions of the individual, and…intended as a stimulus for those exertions” (qtd. in Khan 59). Although understood by many would-be patentees as the legal recognition of a natural right over property in ideas, patents are instead an exemplary exception to the natural rights philosophy of nineteenth-century US law, since state agents like Marshall justified the short lifespan of patent protections through reference to “public interests” that would be contravened if the patentee’s indefinite monopoly prevented the complete diffusion of new technologies, thus impeding the very economic development that patents were initially devised to stimulate (Parthasarathy 21).

Like many other invocations of public interest, the apparent benevolence of patent law is, in the main, a capitalist fiction. Patent law certainly releases an individual’s private property into the intellectual commons, thus terminating the property right after a set number of years as long as the patentee has not been granted an extension; however, the benefits of an intellectual commons for inventors who could now legally appropriate aspects of patent-protected technologies to invent (and patent) new devices are nominal compared to the advantages for a capitalist class that could now access new means of production. In fact, although the expiration of intellectual property protections theoretically made new inventions accessible to a nineteenth-century public, only wealthy planters, bankers, and industrialists had the capital to invest in the manufacture of these inventions at scale. For example, “the whole set up, complete and running,” of Rillieux’s sugar apparatus, which I discuss in detail below, cost an exorbitant $32,000, not including “the brick and carpenter’s work [that] is to be done at the expense of the planter” (“N. Rillieux’s Sugar Apparatus”). Although anyone could, in theory, appropriate an inventor’s idea from the intellectual commons once the patent had run out, the ultimate beneficiaries of this freedom from intellectual property law were agricultural and manufacturing industrialists who could afford to improve on the technical means of production.

What a critique of patent law reveals is that capitalism does not protect private property, as its ideologues avow, but rather selectively supports property rights when these rights benefit the reproduction of capital—or when workers force capital into making concessions. Indeed, Holt sought to reform patent law in favor of individual inventors by leveraging proslavery arguments about the sanctity of personal private property. On 6 February 1858, when Holt gave his annual report to Congress on the state of manufacture and invention, he referenced the case of Ned’s plow as evidence of the insecure legal protections given to invention. “While…this species of property,” Holt asserts, referring to patentable inventions, “yields to none other in its national importance, and surpasses all others in the amount which it pays for the legal safeguards thrown around it, it is notorious that it enjoys but a precarious and incomplete protection” (Report 9). With language that could easily be found in planters’ justifications for slavery, Holt, a slave owner himself, indicates that while Congress has been strengthening property rights in human chattel, it has neglected to give the same vigorous protections to intellectual property. Holt argues that the helplessness of “the inventors as a class” resides in their inability to profit from their inventions when they are constantly battling infringements in the courts (9). “The insolence and unscrupulousness of capital,” Holt writes, “subsidizing and leading on its mercenary minions in the work of pirating some valuable invention held by powerless hands, can scarcely be conceived of” (9–10). Because capitalists would prefer to appropriate inventions as quickly as possible, risking even infringement lawsuits to make use of new technologies that would facilitate the extraction of surplus value, any monopoly given to individual inventors is a labor concession won by patent reformers. To make a case for these individual property rights, Holt pits the interests of free inventors against the interests of enslaved inventors, leveraging a steadfast belief in the inalienable power of ownership—whether of slaves or of the inventions of slaves.

Holt can conceive of a critique of capitalism only from the standpoint of securing private property. With detectable sarcasm toward the melodrama of patent reform, Frederick Douglass describes the “broad and bitter complaint” of “social reformers and political economists that mankind have everywhere been cheated of the natural fruit of their inventive genius: &c” (127). Once patent advocates subsume “inventive genius” to the protections of bourgeois property, they adopt the broad and bitter resentment of the propertied and proper subject of media vita. With the patent system, capitalist culture commodifies the products of inventive work, turning newly developed means into ownable commodities that can be sold, licensed, and, when the monopoly inevitably expires, appropriated by the capitalist class. From the perspective of Holt’s white anticapitalism, then, the political task is to restore one’s legal and economic entitlement to the products of invention. Resentful of an economic system that would deprive them of their profits and capacity of means-making, Holt and Stuart seek to restore the presumed subject of media vita whose powers over means-making are their own absolute property, akin to the property that slave owners have in their slaves.

Such reactionary reform also appears in the literature of the period. In contrast to Benjamin Franklin’s definition of man as a “tool-making animal” (qtd. in Boswell 245), Edgar Allan Poe writes in an 1845 essay titled “Diddling Considered as One of the Exact Sciences” that “man is an animal that diddles” (145). In Poe’s tongue-in-cheek philosophy, to diddle is to be a “banker in petto,” a minor financial operator who “invents and circumvents” (146). Were he not invested in petty cons and schemes, the diddler “would be a maker of patent rat-traps or an angler for trout.” In Poe’s earlier tale “The Man That Was Used Up,” which was first published in 1839 and has been described as an account of the effects of “a rapidly changing, technologically mediated lifeworld upon the human subject” (Berkley 362), Poe imagines the transformation of human subjectivity in the time of diddlers. Whether at a literary soiree, a hounding sermon, or a theatrical production of Othello, the narrator of the tale tries and fails to learn about the mysterious Brevet Brigadier General John A. B. C. Smith, recently home from a settler colonial campaign, from female socialites who repeat to the narrator, nearly verbatim, the same story that is interrupted whenever they utter the word man. With mounting agitation, the narrator seeks the truth from the man himself, intruding on Brevet Brigadier General Smith during his morning toilette. Gravely injured from battle, Smith requires his Black “valet” named Pompey to assemble his body from various mechanical parts that he has purchased from specialized vendors of eyes, legs, shoulders, bosoms, teeth, scalps, and even palates (Poe, “Man” 47). The secret of “man,” it seems, is that he is no more than an “odd-looking bundle of something” that takes human form only through the manipulations of mechanical technology and racialized human labor.

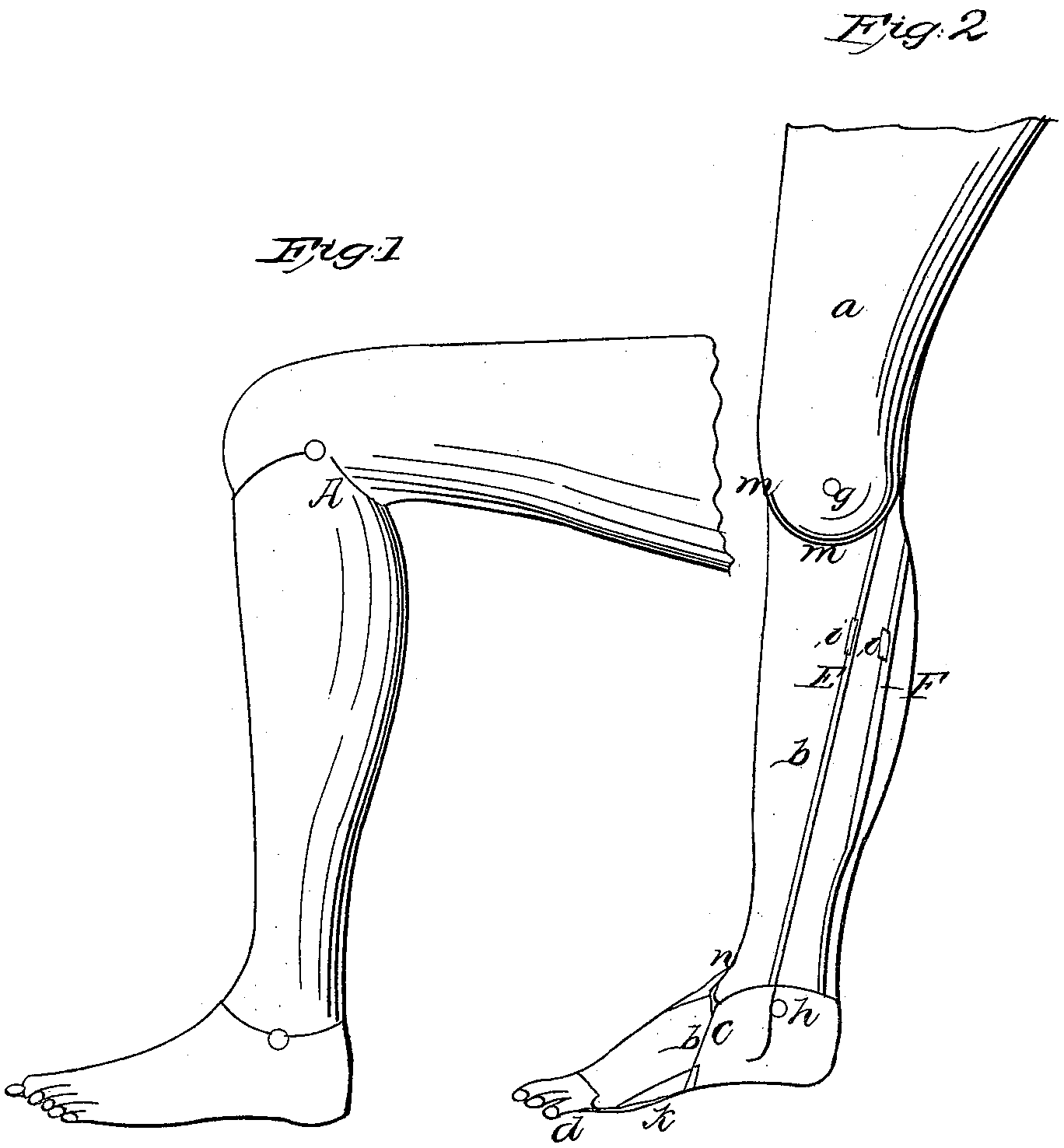

The Brevet Brigadier General, however, is alienated from his organic body not necessarily because he requires inorganic prosthetics to move and speak but because he must purchase his body from various vendors, making literal the presumption in natural rights philosophy of owning oneself. Through settler colonial war and a system of racialized labor, Brevet Brigadier General Smith has become a man who literally owns himself, an ideal representative of “possessive individualism” (Macpherson). Indeed, Smith marvels at patented mechanical wondersthat include “man-traps and spring-guns” (Poe, “Man” 43), devices that the literary critic Klaus Benesch notes were used to deter trespassing and theft of private property (123). Yet these references to patent law undermine Smith’s gleeful inventory of the marvelous body parts he owns. The A. B. C. in Smith’s name points to the allegorical everyman element of the narrative, but these initials also call to mind the figures in patent applications. Take, for example, a diagram from the 1846 patent for the Palmer Leg (fig. 1): B. Frank Palmer, who had lost a leg in a childhood accident, specifies in his patent application that “the construction of my leg is as follows. a, b, c, and d” (1). Although the Palmer Leg was patented after Poe published “The Man That Was Used Up,” its specification follows the common convention of using alphabetic characters to help guide assembly, which Poe transposes to Smith’s name, as if the general, too, were printed with assembly instructions. Thus, while Smith might own his body parts, he cannot own the idea of his parts or their method of assembly. In other words, Smith owns the product but not the underlying process of production. White, propertied men like Smith who believe in what Amy Dru Stanley has called the “basic proprietary right [of] entitlement to oneself” might feel that they embody the masculine ideal of self-ownership, but the patent for the very idea of man, including for his assembly, is held by someone else (8).

Fig. 1. Drawing from B. F. Palmer’s 1846 patent for a prosthetic leg.

For nineteenth-century Black inventors and patentees, however, self-ownership could hardly be an unchallenged normative ideal. African Americans had long been inventing, but like most American inventors, they only began patenting in the antebellum period. In The Condition, Elevation, Emigration, and Destiny of the Colored People of the United States (1852), Martin R. Delany lists several Black inventors, including Henry Blair of Maryland, who patented his corn planter, and Henry Boyd of Cincinnati, who “is the patentee, or holds the right of the Patent Bedsteads” (100). Delany’s list of patentees could have also included, among others, Thomas Jennings, the first identified African American inventor to receive a patent, and the three-time patentee Robert Benjamin Lewis. By the 1880s, the list could have been further extended to include the Black women inventors Judy W. Reed, Sarah E. Goode, and Miriam Benjamin.Footnote 5 Delany’s list of inventors indicates his admiration for mechanical ingenuity and his conviction that evidence of the “practical utility of colored people” might refute the racist view that “we are consumers and non-producers—that we contribute nothing to the general progress of man” (95). While any invention could serve as evidence of Black intellectual capacity against emerging regimes of race science, the patent represented a state-recognized endorsement of the African American inventor’s “ingenuity and skill” beyond that of “an ordinary mechanic” (Hotchkiss). Indeed, in 1913 Henry E. Baker, an African American patent office employee, considered “the very widespread belief…that the colored man has done absolutely nothing of value in the line of invention” to be “but a reflex of the opinions variously expressed…on the subject of the capacity of the colored man for mental work of a higher order”—opinions that Baker suggests have been endlessly refuted by African American intellectuals going back at least to the polymath Benjamin Banneker and his correspondence with Thomas Jefferson (3). Just as Black writers sought to “show the fallacy of that stupid theory, that nature has done nothing but fit us for slaves,” as James W. C. Pennington’s preface to Ann Plato’s book of poems and essays argued (qtd. in Gates 130), Black inventors could use the officially recognized patent to refute a white-defined image of blackness as a signifier of instrumentality—a human means rather than an inventor of means (Gates 130).

While the patent office could serve as a state archive of Black ingenuity, the patent specification could be a political instrument for the practice of citizenship. Derrick R. Spires argues, in reference to the everyday practices of citizenship, that Black activists and intellectuals “reject definitions of ‘citizen’ based on who a person is…in favor of definitions grounded in the active engagement in the process of creating and maintaining collectivity” (3). As an exemplary speech act that transformed an idea into property, the patent required for its successful performance that the would-be patentee make a declaration of citizenship. Thus, if Black citizenship is “not a thing determined by who one is but rather by what one does,” then Black patentees speak citizenship into existence by patenting their inventions. For example, an 1859 post–Dred Scott obituary for Jennings in the Douglass’ Monthly states that “although it was well known that he was a black man of ‘African descent,’” the patent recognizes him as a “‘citizen of the United States’” (“Thomas L. Jennings”). The obituary continues, “This document, in an antique gilded frame, hangs above the bed in which Mr. JENNINGS breathed his last.” J. L. Austin famously cites unsuccessful wedding vows as the exemplary case of an “infelicitous” speech act (14)—the honorary position that Jennings gave to his patent perhaps shows that the citizenship attested by the document is a matter of conjugal felicity. While it was common in the United States for inventors to seek patents for noncommercial reasons, including to mobilize them as “high-quality credentials” of individual or national inventiveness, for African Americans patent grants were a matter of becoming not only “useful citizens” but citizens at all (Swanson, “Beyond the Progress” 372).

Although Black inventors used the patent as a political instrument, it was also, unsurprisingly, a financial instrument. Rillieux, an homme de couleur libre, or free man of color, from New Orleans who had studied chemical engineering in Paris and taught applied mechanics at the École Centrale, returned to Louisiana at the request of the banker and planter Edmond Forstall to become the chief engineer of a New Orleans sugar refinery. This economic venture never materialized, but Rillieux nonetheless remained in New Orleans, where he perfected his improvements of Charles Derosne and Jean-François Cail’s sugar-refining system. In the Derosne and Cail apparatus, steam boilers funneled heat through pipes either underneath or within vacuum-sealed containers of cane juice. Whereas earlier sugar-boiling methods required a constant supply of fuelwood to heat each sugar cauldron, this “double effect” system captured a portion of the exhaust steam from the boiling juice and put it back to work to heat other cauldrons down the sugar production line. Rillieux’s improvement further conserved the steam by putting the Derosne apparatus “in vacuo, and thus laid the foundation for all modern industrial evaporation” (“Norbert Rillieux” [275]). Although Rillieux is generally considered to have improved on the Derosne system, he claimed in the pages of De Bow’s Review that Derosne had in fact stolen his idea for “boiling one vacuum pan by the vapor from another” and that “Derosne made a trial…in such a defective manner as to show plainly that he did not comprehend it” (“Sugar” 57). Whatever the true history of the invention, Rillieux’s patented technology (Rillieux, “Evaporating Pan”) successively reharnessed the latent heat energy of the steam in a remarkable “triple effect” system that became popular among wealthy, enterprising planters throughout Louisiana and Cuba (“Norbert Rillieux” [285]). The historian Kris Manjapra writes that the archival recovery of Black and Creole intellectuals like Rillieux refutes the “conviction that West Indian planters” were “the ones with the methods” and thus shows the “deeply skewed grasp on reality promulgated by racial capitalism” (371). While the dominant history of racial capitalism has tended to emphasize instances of Black subjection to the interests of a white capitalist class, the reality is that social domination compels free inventors like Rillieux, as well as the many more anonymous and enslaved inventors on plantations, to develop labor-saving devices to be integrated into the productive forces of racial capitalism. As Orlando Patterson notes, for Black workers to maintain and reproduce the conditions of their existence, they had to continuously produce value for a white-controlled capitalist system that dominates them not only as workers but also as racialized subjects.

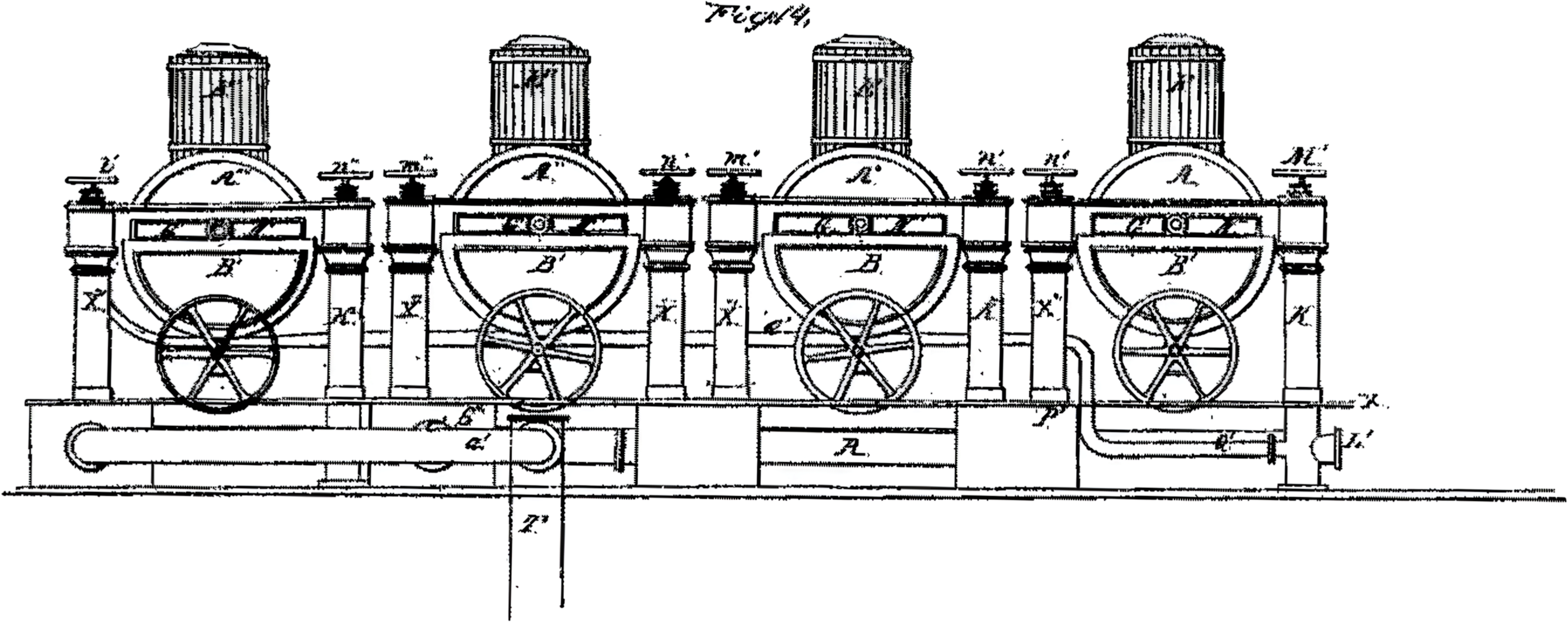

The sugar planters could recognize the brilliance of Rillieux’s sugar system only for its “efficacy and economy,” as the planter and future Confederate secretary of state Judah Benjamin raved (341), but the device serves as a vivid illustration of capitalism under media vita. Once the production process is jump-started with an originary accumulation of fuelwood for the first steam boiler, the machine’s automatic self-boiling mechanism takes over. At each stage of the production process, excess steam that would otherwise escape the relentless work of converting juice into sugar—and, ultimately, into gold and silver for the planter—is recaptured and used to fuel the following stages of sugar refinement (fig. 2). Rillieux’s machine thus enacts a capitalist fantasy of work. “When a labourer lays down his spade,” observed the cotton magnate Henry Ashworth with surprising frankness, “he renders useless, for that period, a capital worth eighteen-pence. When one of our people leaves the mill, he renders useless a capital that has cost £100,000” (qtd. in Marx 529). This rule for the cotton industry is even more applicable to the sugar industry, particularly during the harvest season, when the cane was processed into sugar as quickly as possible to prevent spoilage and to yield profits high enough to perpetuate, for another year at least, the debt cycles of plantation agriculture. During these periods, sugar planters extracted as much labor as possible from their enslaved workforce, reducing periods of rest to the barest life-sustaining minimum and often not even that. But even enslaved laborers—who in unindustrialized sugar mills worked in shifts to keep the vats of sugar boiling without interruption (Rood 19)—must leave the mill to eat, sleep, and reproduce their capacity for work. In Rillieux’s machine, however, the steam is not released from the work process after transferring its heat energy to the juice but is instead forced to remain in the mill, contributing its energy to each successive act of boiling so that each produces still more steam for work. Unlike the workers who must rest to restore their capacity for work, the steam’s work of boiling sugar produces more steam energy in a self-propulsive image of value creation. In Rillieux’s apparatus, work—rather than rest and leisure—is the prerequisite for work.

Fig. 2. Drawing from Norbert Rillieux’s 1846 patent for a multiple-effect evaporating pan.

Of course, self-boiling automaticity is only a fantasy image of self-perpetuating work for the very reason that the machine requires human operators and is fed from manually harvested sugarcane. It is, however, a real image of capital. The historian Daniel Rood observes that because Rillieux’s invention turned the cane juice into its own energy source and means of production, in this apparatus sugar was “both the medium and the outcome of the production process” (35). As both medium and outcome, sugar takes various molecular forms, each further propelling the expansion of value: in its liquid form, the boiling juice produces steam, which heats the juice in a cascading perpetuum mobile that concentrates the juice until it takes its most profitable form as crystallized sugar. It should be recalled, too, that sugar plantations provided the inexpensive source of glucose that spurred the caloric revolution needed to sustain the long, grueling hours of factory life in Europe and the United States. Sugar energizes not only its own industrial production but also the larger world of industrial capitalism.

If, as one philosopher has suggested, each type of society has its own machinic analogue (Deleuze 6), then one might say that a capitalist society under media vita is represented by Rillieux’s automatic sugar apparatus. Analogous to sugar in the machine, capital is its own medium and outcome of the production process. Capital, too, must constantly change forms, all the while remaining capital and returning to itself in expanded form. The cycle of capitalist expansion consists of semiautonomous moments that are nonetheless synchronized—it is a process that reveals how capital is unique in the history of media objects because it is not media-specific. Rather, it is defined by its power to transform from one medium to another—money, labor, fixed manufactory, and so on—and to find new routes of accumulation, whether in market access, production, or financial dealing, and yet always to preserve and develop its specific identity. If media vita names an emergent way of experiencing life as mediated, then Rillieux’s patent technology aptly portrays media vita because sugar in his machine, like capital, is a self-mediating form of value that is also self-expanding. In a spectacular illustration of the distinctive mediational capacities of capital, Rillieux’s sugar apparatus is the consummate technology of media vita.

The Patent Form

Rillieux’s patented sugar apparatus—and the media vita that it exemplifies from the top-down perspective of the Creole intellectual class—can be productively contrasted with Northup’s practical knowledge of these apparatuses. In 1841, Northup traveled from his home in upstate New York to Washington, DC, where he was kidnapped and sold into slavery in Louisiana. He recounted these experiences in his 1853 memoir Twelve Years a Slave, which he wrote after effecting his release from bondage and return to New York. Whereas Rillieux applied for a patent and acquired intellectual property rights over his inventions, Northup analyzes the patent as a literary form and troubles the dispossessive consciousness that the form instantiates. A self-described “Jack at all trades” who had worked on the 1828–29 repair of the Champlain Canal in New York, Northup takes a keen interest in the machinery of the steam-powered sugar mill on the Hawkins sugar plantation in Bayou Bœuf (102). It was around this time that Rillieux’s apparatus was being installed throughout Louisiana’s sugar plantations, but even if the Hawkins plantation did not include Rillieux’s patented “triple effect” system, Northup’s description of the steam-powered sugar mill suggests that he might very well have encountered the “double effect” Derosne and Cail system, itself a possible knockoff of Rillieux’s stolen designs.

Notable for his stoic, documentary accounts of plantation life, Northup describes the sugar apparatus in a way that discloses the patent’s transformation from a legal-bureaucratic form into a literary form:

[The cane juice] runs into a large reservoir underneath the ground floor, from whence it is carried up, by means of a steam pump, into a clarifier made of sheet iron, where it is heated by steam until it boils. From the first clarifier it is carried in pipes to a second and a third, and thence into close iron pans, through which tubes pass, filled with steam. While in a boiling state it flows through three pans in succession, and is then carried in other pipes down to the coolers on the ground floor. (212)

In this passage (taken from a much longer description), Northup adopts the formal elements of the patent when he provides a technician’s view into sugar making, adapting what Lisa Gitelman calls “the language for machines” that the patent system had popularized. Gitelman writes that the patent’s specification for the invention must “be clear, clean, natural, and free from ambiguity. No symbolic or figurative meanings pertain” (101). In conveying his experience of the sugar mill through what I call the patent form, or the culturally recognized voice of patent factuality, Northup’s description bridges the formal differences between the patent and the slave narrative with their shared presumption of disclosure.Footnote 6 As Janet Neary writes, “the slave narrative is a genre bound by evidence,” in that a Black author was expected to “provide evidence to satisfy claims that for him are not in doubt, such as his existence, the validity of his experience, [and] the harm he has suffered as a result of racial slavery” (51, 57). By publicizing the workings of Louisiana sugar manufacture through the patent form, Northup supplies evidence of his having been there, on the plantation; indeed, his knowledge of the inner workings of the plantation mirrors the inventor’s knowledge of the inner workings of a machine—implicit evidence of technical know-how that bolsters the patent applicant’s claim to be the true and original inventor. Northup thus reveals the shared insistence on factuality between the patent form and the slave narrative. At the same time, he uses the dispassionate utterance of the patent form to secure evidence not of original invention—and thus not of intellectual property rights—but of the legally unsanctioned transformation of his own being into property.

Yet, as Neary notes, Northup expresses skepticism toward the power of evidence when no documentary evidence of his freedom, including even his free papers, could compel kidnappers and planters to treat him as a free person. If it is true that “Black citizenship—and the evidence that guarantees it—is hollow” from the perspective of the state (Neary 52), and Northup experiences this hollowness through its most terrible effects, then his use of the patent form in his narrative cannot be imagined as simply more evidence of his citizenship or, more philosophically, of his inclusion into the ranks of media vita’s proper subjects. Instead, Northup’s patent form unsettles the underlying notions of mind and craftwork presumed in media vita.

To illustrate Northup’s critique of mind, consider his description of an invention of his own design: an unassuming fish trap. Northup recounts that, after worms had infested the slave laborers’ allotted portion of bacon, he “conceived a plan of providing myself with food,” which “has been followed by many others in my condition, up and down the bayou” (200). Northup’s invention is a form of passive fishing that would supply him and his fellow slaves with food without their having to exert themselves hunting racoons and opossums, since “after a long and hard day’s work, the weary slave feels little like going to the swamp for his supper” (201). Northup describes his fish trap in another lengthy passage composed in the patent’s “language for machines,” which I reproduce in full to encourage readers to observe how the image of the fish trap unfolds in mental space, since this unfolding is crucial for understanding Northup’s critique of media vita:

A frame between two and three feet square is made, and of a greater or less height, according to the depth of water. Boards or slats are nailed on three sides of this frame, not so closely, however, as to prevent the water circulating freely through it. A door is fitted into the fourth side, in such manner that it will slide easily up and down in the grooves cut in the two posts. A movable bottom is then so fitted that it can be raised to the top of the frame without difficulty. In the centre of the movable bottom an auger hole is bored, and into this one end of a handle or round stick is fastened on the under side so loosely that it will turn. The handle ascends from the centre of the movable bottom to the top of the frame, or as much higher as is desirable. Up and down this handle, in a great many places, are gimlet holes, through which small sticks are inserted, extending to opposite sides of the frame. So many of these small sticks are running out from the handle in all directions, that a fish of any considerable dimensions cannot pass through without hitting one of them. The frame is then placed in the water and made stationary.The trap is “set” by sliding or drawing up the door, and kept in that position by another stick, one end of which rests in a notch on the inner side, the other end in a notch made in the handle, running up from the centre of the movable bottom. The trap is baited by rolling a handful of wet meal and cotton together until it becomes hard, and depositing it in the back part of the frame. A fish swimming through the upraised door towards the bait, necessarily strikes one of the small sticks turning the handle, which displacing the stick supporting the door, the latter falls, securing the fish within the frame. Taking hold of the top of the handle, the movable bottom is then drawn up to the surface of the water, and the fish taken out. (202–03)

As he often does in his digressive descriptions, Northup uses the passive voice, which becomes especially pronounced in this passage; he removes himself as the agential subject of invention and instead imagines the making of the machine without a clearly defined maker. Northup goes to great lengths to keep up this fiction of ghostly, subjectless production. For example, when he begins a sentence “Taking hold of the top of the handle,” one expects, finally, to see Northup—or at least an indefinite subject, like a hypothetical future user or one of the “many others” who benefited from his invention—wading into the water to retrieve an ensnared fish, but he instead veers off, leaving a dangling modifier and offering as the subject of the sentence “the movable bottom,” which “is then drawn up to the surface of the water, and the fish taken out.” Even when Northup describes the action of grasping a handle, there is no hand; it is an act without an actor, an effect without a motive cause. In fact, Northup slips into the active voice only twice in the specification—once when he describes how “the handle ascends” as if by its own active force, and again, climactically, when “a fish swimming through the upraised door towards the bait, necessarily strikes one of the small sticks,” setting off the causal chain that ends in the fish’s capture. The passive voice even extends beyond the specification of the invention when Northup likens the fish trap to “a mine [that] was opened—a new resource [that] was developed” (203).

Compare, for example, this subjectless inactivity with a conventionally “active” scene during which Northup fights his brutish enslaver, John Tibeats. When Tibeats falsely accuses Northup of making a carpentry mistake, which Northup casually denies, Tibeats charges at him with a hatchet. After disarming Tibeats, Northup “seized him by the throat,” causing Tibeats to become “pliant and unstrung” (135). The language of activity might be expected in this tumultuous scene, but what is unexpected is Northup’s unusual phrase, “pliant and unstrung,” which recalls the literal instrumentality of his treasured violin. Northup pins Tibeats with one hand and seizes his throat with another, stretching his enslaver like an instrument being mended or dismantled.

If during scenes of narrative activity Northup plucks his metaphors from the language of instrumentality, then it is all the more surprising that he absents himself and his activity from the work of inventing a new technical instrument. I suggest that these competing representations of Northup’s activity are symptomatic of his narrative’s mingling of genres and forms. Northup’s description of interpersonal battle with Tibeats conforms not only to the male-authored slave narrative’s gender norms but also to the conventional depiction of the Byronic figure of the “hereditary bondsman” who must “strike the blow” for freedom, a popular literary allusion in Black abolitionist literature (Phan 160). The patent form, however, complicates this received image of Romantic action. The patent involves a mix of passive and active voice, almost always beginning in the first person with a declaration of the patentee’s name and place of residence and a claim to the discovery or invention. While the legal patent ties the proper name and first-person pronoun to the claim of originality and usefulness, its form demands the passive voice for the specification of the invention. Indeed, one might even say that the abrupt transition in the patent application from the particular and subjective inventor to the abstracted, deindividuated description of the invention parallels the movement of the intellectual property right itself from the individual inventor to its dissolution in the public domain after the term of protection expires, for the general uptake of the invention among the capitalist class. Moving from the singular to the general, the patent form mimics the trajectory of the property right it confers.

In the context of Northup’s slave narrative, the patent form produces decidedly different legal and performative effects than it does for the free inventor who can enjoy the economic privileges of intellectual property and the social value of transforming oneself into the proper subject of media vita. In the very practical terms of patent law, Northup forfeits his potential right to exclusive ownership of his invention when he publishes the means for manufacturing his fish trap. Patent law’s strict originality requirement prohibits any public description of the device before an application is filed. Even before the publication of his memoir, Northup would have lost the right to patent his fish trap once he popularized his idea “up and down the bayou.” But this breach of the stipulation of originality also means that Northup prevents anyone else from claiming his idea as intellectual property. Individual manufacturers might use Northup’s specifications to sell fish traps of their own making, but no one, not even Northup, can own the idea of the trap. Northup cannot control whether his narrative will sway public opinion against the property systems of slavery—which is to say, like all writers, Northup does not know how or even if literature can intervene in political and economic formations—but he can preclude his specific design for a labor-saving device from being subsumed into intellectual property.

Beyond the practicalities of patent law, Northup offers a philosophical intervention in the conception of mind that the patent form enacts. Before constructing the actual trap, Northup describes how he had “in [his] mind, conceived the manner in which it could be done,” projecting a virtual, intellectual plane of instrumental knowledge. This intellectual foresight, what Hannah Arendt has called the “craftsman’s contemplative glance” (303), is unimpeded by the material presence of a hand, a human body, or a subject in any obvious sense, thus manifesting the contemplative life in the active, practical life of the inventor. The absence of a human figure in the specification of Northup’s fish trap encourages the reader likewise to imagine a machine assembling itself by itself in their own contemplative glance. Through the slow unfolding specification of the device, Northup replicates this glance in the reader’s imagination as they follow the assembly of the fish trap through the ghostly mechanism of thought itself. By design, the description of the fish trap makes clear that the reader is not meant to imagine Northup wading into the bayou, testing the fit of wooden joints, failing with one idea, succeeding with another, before finally, triumphantly, lifting an entrapped fish. Such a narrative portrayal might be appropriate for a conventional memoir or novel about human ingenuity, but it is ill-fitted for Northup’s patent form.

Northup’s description of the fish trap thus encourages the reader to experience the emptiness of intellectual space. When Northup launches into his specification, he provides no setting or contextual details, stating simply, “A frame between two and three feet square is made.” As though out of thin air, objects and actions materialize in intellectual space without subjects to guide their assembly. In this way, Northup traces a topology of mind as blank, empty, and waiting to be filled—the mental equivalent of Henri Lefebvre’s conception of physical space as “a void packed like a parcel with various contents” (27). It is “transparent space,” in the words of Katherine McKittrick, conveying “the idea that space ‘just is,’ and that space and place are merely containers for human complexities and social relations” (xi). The representation of the mind in particular as an empty “container” is a common metaphor that Hannah Walser argues appears in nineteenth-century American literature “with remarkable literal-mindedness” but that dates at least to Locke’s metaphor of the mind as an “Empty cabinet” (Walser 39). Yet what distinguishes Northup’s image of mind from these other metaphors is that his use of the patent form encourages readers to experience the emptiness of intellectual space as it is about to be filled by the rationally ordered process of ghostly construction. The emptiness of mind that the patent form presumes as the precondition for imaginative construction is thus filled not with the Palmer Leg but with the Northup cabinet-like mind.

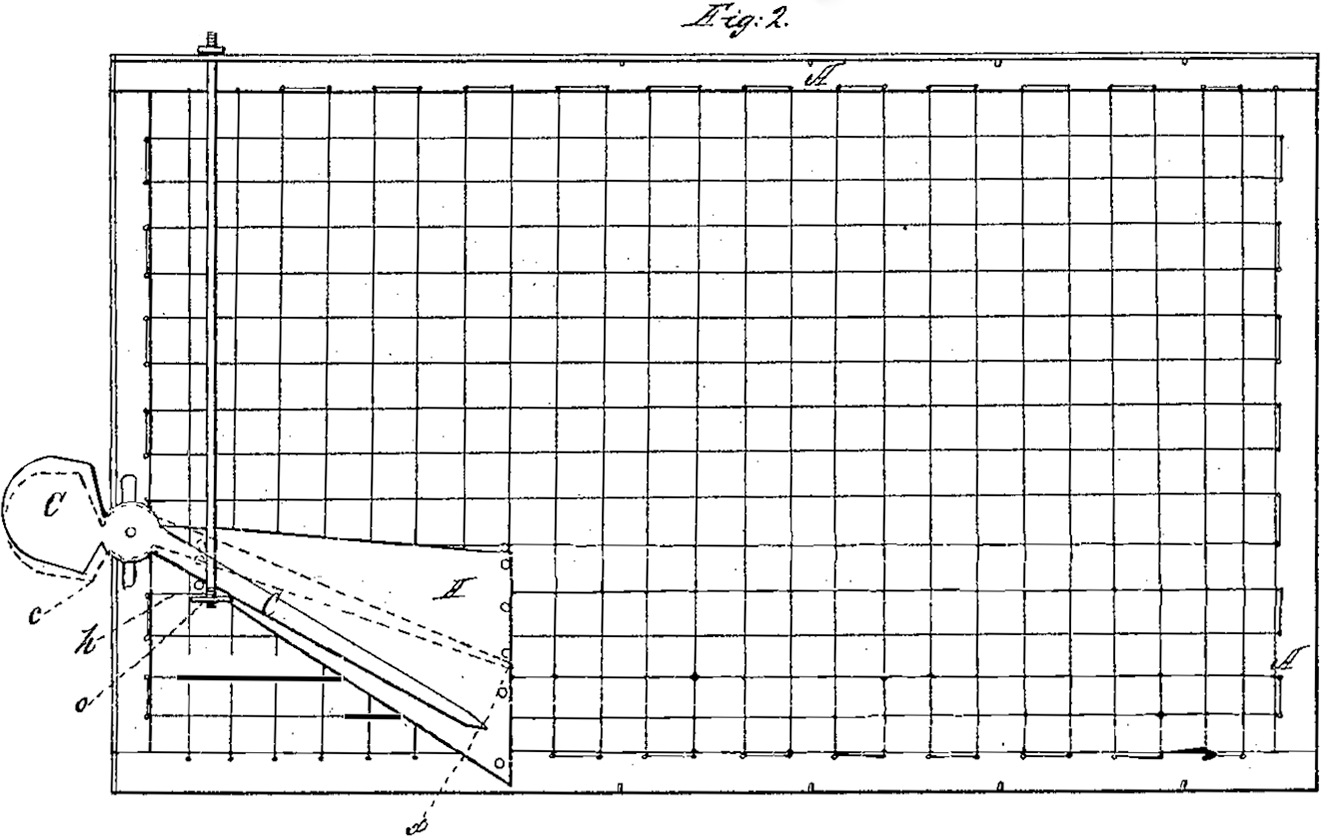

Stefano Harney and Fred Moten, in their 2021 collection All Incomplete, critique this way of representing cognition, arguing that the empty mind of the tabula rasa, which the patent form inherits from Enlightenment philosophy, expresses in intellectual space the colonial ideology of terra nullius. The mind of the Enlightenment might be an “empty Cabinet,” but Harney and Moten suggest that “for this emptiness to become private property it must be filled with and located in the coordinates of space and time” (16). Akin to colonial acts of surveying and parceling the American continent to facilitate speculation and the commodification of land, the empty mind, too, had to be plotted on a time-space axis for it to become ordered, rational, and governable. Reuben L. Payne’s figural illustrations from his 1858 patent for a “cage trap” precisely illustrate this ideological conjuncture of physical and mental space (fig. 3). The lateral view of Payne’s invention makes clear that that the inventor pictures his trap as a grid: an ordered space in which the woven metal wires that form the cage recall the “rectangular survey of straight lines and right angles” prescribed by the Land Ordinance of 1785 for organizing the newly appropriated Indigenous lands between the Appalachians and the Mississippi and that would become the basis for all land surveys for the rest of the continent (Siegert 112). “Is it a leap,” Harney and Moten ask when reflecting on the similarity between the emplotment of mind and the emplotment of earth, “to say logic and logistics start here inseparably” (16)? Payne’s gridlike pattern suggests that it is not, since his design could easily double as the grid of the logistic mind and the lattices of settler colonial space.

Fig. 3. Drawing from R. L. Payne’s 1858 patent for a cage trap.

When media vita is identified as a racialized mode of reasoning for its way of rationalizing and hierarchizing difference according to imagined capacities for mediation, with those who invent means on one end and those who implement them on the other, the constrained form of consciousness that it entails comes into view. Even as Northup is no different from other practitioners of the patent form when he has his readers experience the preconditional emptiness of this latticelike consciousness through the form’s distinctive impetus to mental composition, in the content of this composition he nonetheless disrupts such consciousness. Unlike the mental void in which it appears, the fish trap is filled with perilous “sticks” that, if activated, shut the prey inside. Northup’s fish trap is not a rational grid but a barbed enclosure. Northup prompts the reader to construct an Enlightenment mental space, but he then tasks the reader with filling that cognitive space with the second space of the barbed trap. Although the patent form produces the mental phenomenon of transparent space, once Northup has the reader imaginatively assemble the barbed fish trap—which is itself a figurative image of mind—this mind appears as a trap. His specification for the fish trap thus enacts a powerful if fleeting awareness of the trappings of mind, a stepping into the conceptual space of the subject of media vita, who intellectually foresees the means they intend to develop, in order to represent the threatening space of this subjectivity from the inside. Instead of leveraging his device as evidence that he, too, is an ingenuous inventor of means—or even limiting his critique of property to the removal of his ideas from the property system—Northup incites the reader to inhabit the mind of the proper subject of media vita only to counter it with inventive tactics aimed at revealing the perils of such a mind.

Northup’s appropriation of the patent form invites us to consider the critical value of broadening the domain of media studies not to include ever more cultural artifacts but instead to understand the racial and economic foundations of the commonplace cultural assumption that we live in a mediated age. And yet it is not my claim that media studies should turn away from groundbreaking materialist studies of technical objects, which often include historical materialist analyses of their social and political contexts. Instead, Northup’s critique of the presumed subject of media vita calls for an excavation of the racialized discourse of mediation and draws attention to the way it prescribes what exactly media and technology do, as when, in the words of the patent historians Edward Beatty, Yovanna Pineda, and Patricio Sáiz, it is said that “humans create technology to mediate the world we live in” (Beatty et al. 146). This article has therefore pursued a materialist understanding of the patent—crucial for understanding how technical objects circulate in capitalist culture—to argue that Black antebellum writers leveraged the patent form to “strip down through layers of attenuated meanings, made an excess in time, over time, assigned by a particular historical order, and there await whatever marvels of my own inventiveness,” as Hortense Spillers writes of her own critical task (65). Stripping down through the layers of media vita, beyond its racial fictions, generic conventions, and forms of consciousness, these writers await the marvels of inventiveness outside the cultural presumptions of property and patentability.