“La derecha y la izquierda unidas jamás serán vencidas”

Nicanor Parra, Chilean “anti-poet”

When I first began working with Chilean public opinion datasets, what struck me most was the explanatory power of the ideology variable. Coming from research on countries like Peru—where party systems are deeply deinstitutionalized and ideological self-placement often yields limited analytical traction—I was surprised by how consistently meaningful this single question was in the Chilean case. And yet, just as surprising today is the growing tendency to describe Chile’s political system as “Peruvianized,” as if the presence of ideological coherence could be reconciled so easily with the erosion of partisan structures.

Clearly, ideological self-positioning in Chile shows remarkable resilience and structuring capacity, even in the context of declining partisan identity—a pattern it indeed shares with Peru. This alone warrants closer attention to the ideological variable. But to move from this observation to the claim that ideology in Chile has become a social identity, as the article “Causes and Consequences of Ideological Persistence: The Case of Chile” (Argote and Visconti Reference Argote and Visconti2025) suggests, is a significant leap—one that, at best, remains an interesting but inadequately tested hypothesis.

Is Ideology in Chile a Social Identity?

The authors define social identity as “a self-categorization into a political group that shapes perceptions, attitudes, and behaviors beyond specific policy preferences” (Argote and Visconti Reference Argote and Visconti2025, 5). This definition is broadly consistent with classic formulations in social psychology, where social identities are understood as durable affiliations with emotionally salient in-groups, often accompanied by negative affect toward out-groups (Tajfel and Turner Reference Tajfel and Turner2004; Huddy Reference Huddy2001). In political behavior literature, social identity implies not only cognitive self-placement but also group consciousness and behavioral differentiation across multiple life domains. For instance, in the United States, being a Democrat or Republican tends to correlate with not only political preferences but also patterns of cultural consumption, neighborhood composition, religious affiliation, and even marital sorting (Mason Reference Mason2018). If identifying as “left” or “right” in Chile operates as a comparable social identity, then we should expect to observe not just consistent ideological self-identification, but also markers of social lifestyle clustering and affective polarization across group boundaries.

But is that truly the case in Chile? Do those who place themselves on the left of the ideological spectrum, for example, actually perceive themselves as part of a cohesive social group labeled “the left”? Does this identification spill over into non-political domains, shaping consumption habits, cultural codes, or social networks? If Argote and Viconti’s compelling hypothesis holds true—that ideology in Chile now operates as a social identity—then two distinct questions need to be addressed. The first is theoretical: is there reason to believe that self-identification as “left” or “right” in Chile entails the kind of shared group consciousness, emotional investment, and behavioral consistency across domains of social life that would warrant calling it a social identity? The second is empirical and methodological: are the authors measuring ideological identity with sufficient nuance to capture the operational (e.g., policy preferences) and symbolic dimensions (e.g., group belonging) associated with their respective social identity? Without clear answers to both, the claim that ideology now functions as a social identity risk sounds more like an aspiration than an empirically validated reality.

On the first point, the evidence provided is, at best, indirect. The article (Argote and Visconti Reference Argote and Visconti2025) shows that ideological self-placement on the left-right scale persists over time, but it does not demonstrate that such positioning constitutes a social identity in a robust sense. To conceptualize ideology as a social identity, one would expect empirical evidence along at least three aspects: symbolic (shared perceptions, group affect), operational (policy preferences and programmatic coherence), and collective consciousness (a self-recognized sense of belonging). Methodologically, these dimensions should be addressed to sustain the identity claim (Ellis and Stimson Reference Ellis and Stimson2009). While some identities—especially in the US context—have been shown to emerge predominantly through symbolic social sorting (e.g., lifestyle and social grouping) (Mason and Wronski Reference Mason and Wronski2018) even in the absence of full operational coherence (Mason Reference Mason2018), the article offers no such demonstration for Chile. In its current form, the argument relies heavily on ideological consistency, but consistency alone does not constitute identity—especially not the kind that reconfigures how individuals interpret the world or relate to others.

This conceptual stretch is compounded by a puzzling set of measurement choices. Despite relying on open access surveys like CEP—which include a categorical item explicitly asking whether respondents identify as left, center, or right—Argote and Visconti choose to build their argument on a 1-to-10 self-placement scale, a tool designed to capture ideological position, not social identification. More ironically, in their own survey, the authors choose not to ask directly about ideological identity—yet they do ask respondents whether they identify as feminists. If the researchers take the decision to ask “Do you identify as a feminist?” (as a proxy of “policy preference” [sic]), why not apply the same logic to political ideology? What we are left with is a conceptually ambitious argument supported by empirically thin proxies—an effort to measure identity without asking about it. The result is a theoretical claim of considerable interest, but one that floats above the evidence rather than emerging from it.

To be fair, my concern is not with the hypothesis itself. I actually find the idea that Chileans carry ideological social identities rather appealing—if it holds up empirically. But, for the sake of the argument, let us grant the authors their premise and see where it leads. Suppose that the 40 percent of Chileans who consistently place themselves on the left or the right are not just expressing preferences but embodying full-fledged social identities. That would mean nearly half the country walks around with a sense of ideological belonging strong enough to imply in-group loyalty, out-group distrust, and perhaps even lifestyle alignment. Is that really the social landscape we are looking at?

And then there is the question of the “independents.” Are they expressing an identity of their own? Titelman and Sajuria (Reference Titelman and Sajuria2024) suggest that Chilean independents are not just fence-sitters but carry a distinct identity defined against partisanship. So, do we now have three ideological social identities—left, right, and “independents”? If the authors are right, we may have to start treating Chile not as a case of ideological fragmentation, but of identity inflation.

Can Negative Partisanship Explain Ideological Stability?

In contexts marked by the erosion of positive partisan identities, locating stable collective references through which citizens relate politically to one another becomes increasingly challenging. The article under discussion (Argote and Visconti Reference Argote and Visconti2025) posits that ideological identities—“left” and “right”—have stepped in to fill this vacuum in Chile, offering durable affective anchors in the absence of strong partisan organizations. While plausible, this reading underestimates a key implication of partisan decline: without organizational scaffolding and effective elite signaling, it is difficult for ideological self-placement to represent the kind of thick, socially embedded identity the authors describe. This memo advances an alternative hypothesis: that what survey responses capture as ideological “stability” may in fact reflect the persistence of negative partisan identities—emotionally charged and ideologically coherent rejections that remain potent even in the absence of coherent in-groups.

Rather than indicating strong ideological belonging, these responses may express structured aversions toward political out-groups—a mechanism that demands far less institutional maintenance and can operate independently of partisan loyalty (Cantú and Haime Reference Haime and Cantú2022). Political psychology has long demonstrated that individuals are often quicker to form collective hostilities than solidarities (Zhong et al. Reference Zhong, Phillips, Leonardelli and Galinsky2008). In fragmented systems such as Chile, as well as in post-collapse systems, what appears to endure is not group allegiance, but the consistent drawing of symbolic boundaries against perceived adversaries.

We must begin by considering negative partisan identities as primary structuring forces in citizen behavior, rather than treating them as derivative or residual phenomena. In fact, this is not even a novel proposition. As far back as The American Voter, Campbell and colleagues (Reference Campbell, Converse, Miller and Stokes1960) recognized that partisanship could take both positive and negative forms, with voters identifying either with a party or against one. The literature already acknowledges that partisan identity is not reducible to its affirmative variant (Rose and Mishler Reference Rose and Mishler1998). Just as voters can feel a sense of belonging to a party or political tribe, they can also define themselves in opposition to one (or several). These negative identities are not the mirror image of positive ones—they operate independently, both psychologically and politically (Medeiros and Noel Reference Medeiros and Noël2014).

Second, unlike their positive counterparts, negative partisanship does not depend on organizational maintenance (e.g., Caruana et al. Reference Caruana, McGregor and Stephenson2015). Parties may vanish, but the grievances they leave behind remain—just as anti-communist sentiment continues to shape political behavior in several established European democracies, long after communist parties have lost relevance or disappeared entirely. Disgust, distrust, and disdain are surprisingly durable resources in a political system. And in many cases, they outlive the parties themselves. In this sense, negative partisanship has an autonomy that makes it resilient to the very partisan collapse that would otherwise erase political identity altogether. This resilience is particularly salient in Chile, where, as De la Cerda (Reference De la Cerda2022) argues, the erosion of partisan identity stems from the collapse of the democracy–authoritarianism cleavage that once structured political life (Torcal and Mainwaring Reference Torcal and Mainwaring2003). In the absence of this anchoring divide, political elites have struggled to articulate compelling ideological narratives capable of reconstituting partisan followings (Luna Reference Luna2016). The decline of such structuring cleavages limits opportunities for positive identity formation—making negative partisanship not just possible, but in many ways more likely.

Third, and perhaps most critically: it is often easier to mobilize against something than in favor of it (Zhong et al. Reference Zhong, Phillips, Leonardelli and Galinsky2008). Campaigns against “el octubrismo” (Diaz et al. Reference Díaz, Rovira and Zanotti2023) or “los comunistas,” (Mesina Reference Mesina2023; Ross and Navia Reference Ross and Navia2024) travel fast in Chilean political discourse—not because voters deeply identify with the other side, but because they know exactly what they are rejecting. It is no accident that some of the most salient recent political movements in Chile—like the Rechazo campaign during the first constitutional plebiscite and the En Contra during the second one—flourished not through propositive ideological cohesion, but through well-articulated opposition (e.g. Cox et al. Reference Cox, Cubillos and Le Foulon2025).

This brings us to the theoretical pivot point. Ideology, in most democratic theory and in frameworks like Kitschelt’s (Reference Kitchel2000) theory of political linkages, is conventionally understood as the core of a programmatic linkage—one of three keyways in which voters and politicians connect, alongside clientelistic and personalistic channels. When parties are strong, they cultivate ideological linkages to reinforce their support base. But when parties weaken or collapse, these linkages may persist independently. As Dalton convincingly shows, the erosion of institutional trust and partisan alignment in advanced democracies has not erased ideological attachments altogether; it has merely rendered them more erratic, harder to channel, and—frankly—easier to exploit (Dalton Reference Dalton2004).

Argote and Visconti (Reference Argote and Visconti2025) offers one possible reading of what happens in such contexts: that ideology becomes not just a programmatic linkage, but a social identity—a durable, emotionally resonant category that structures life well beyond the ballot box. The authors do make a commendable effort to empirically ground this transformation, drawing from survey data to support their claim. Unfortunately, their argument ultimately rests on a theoretical escalation. There is another, more grounded alternative: that negative partisan identities, not ideology as social identities, are doing the heavy lifting. In this scenario, ideology remains as the pillar of the political linkage—one that voters use to judge candidates, articulate preferences, or reject alternatives—but it does not transform into a social identity on its own.

Instead, voters develop negative identities—anti-communist, anti-pinochetista, anti-establishment—and these sentiments are activated through ideological cues (Meléndez Reference Meléndez2022). The programmatic linkage is thus preserved, but it serves to nourish a negative partisan identification rather than a cohesive ideological community. Importantly, this model aligns with recent findings on disjointed polarization (Luna Reference Luna2024), affective rejection without partisan rooting (Segovia Reference Segovia2022), and emerging work on partisan negation as a structuring force in post-collapse party systems (Cavieres et al. Reference Cavieres, Guzmán-Castillo and Meléndez2025). In these settings (but also in well-established party systems), identities do not disappear with party decline—they simply mutate. Positive partisan identities recede; negative ones proliferate. And these negative identities do not require the same kind of sociocultural infrastructure or mobilization mechanisms that traditional positive identities need. They can be light, affective, and even fleeting—yet still effective. One may not attend rallies “as a leftist,” but one might very well just vote to block “those people” from winning. As Schedler (Reference Schedler2023) puts it, when polarization unfolds, it does as “rejection without affection,” driven not by loyalty to one side but by aversion to the other—a dynamic that resonates strongly with the Chilean experience.

In sum, ideological self-placement may remain stable in survey responses not because ideology has become a social identity, but because negative partisan identities—mobilized through programmatic rejection or symbolic opposition—have filled the identity vacuum left behind by decaying party structures. This scenario keeps ideology in its rightful place: as the core of a programmatic political linkage, not a surrogate identity. And it also keeps our analytical feet on the ground, where voters, more often than not, are not embracing teams—they are booing from the sidelines.

A Conceptual Architecture for Linking Voters and Parties

If the previous discussion has shown anything, it is that ideology does not float freely in the political ether. Nor does it spontaneously solidify into social identity just because partisan labels begin to fade. What we need—beyond competing claims about whether Chileans “really feel” “left” or “right”—is a framework that clarifies how ideologies, identities, and political linkages interact under varying institutional conditions. The goal here is to offer just that: a conceptual architecture that helps organize our thinking about how voters relate to parties, and how these relationships endure—or mutate—even when parties themselves do not.

This framework emerges as both a critique and a proposal. It critiques the assumption—implicit in Argote and Visconti’s (Reference Argote and Visconti2025) article but also in much of the literature on ideology as identity—that ideological labels can stand in for deeper social commitments without tracing their institutional or relational underpinnings. And it proposes a model in which partisan identities, both positive and negative, are analytically distinguished from the linkages that sustain them. Only by maintaining this separation can we make sense of phenomena like ideological stability without mistaking it for identity resilience.

Let us begin by distinguishing between political identities and political linkages. Political identities refer to durable psychological attachments that citizens develop toward parties or political forces—attachments that, as Green et al. (Reference Green, Palmquist and Schickler2004) argue, resemble the stability and depth of religious identities. These identities can be positive (e.g., “I am a Socialist”) or negative (e.g., “I am anti-Communist”). While the literature tends to focus on the positive side—especially in the American context, where partisan identity often borders on a cultural tribalism (Mason Reference Mason2018; Iyengar et al. Reference Iyengar, Lelkes, Levendusky, Malhotra and Westwood2019)—negative partisanship has proven to be a powerful and under-theorized force, particularly in party systems marked by collapse or deinstitutionalization. Crucially, these negative partisan identities do not require an in-group reference to be activated; individuals can identify what they are not without a clear sense of what they are (Caruana et al. Reference Caruana, McGregor and Stephenson2015; Samuels and Zucco Reference Samuels and Zucco2018). They are not simply the absence of loyalty; they are loyalty in reverse—anchored in rejection, affectively charged, and politically mobilizable. This resonates with broader findings from social psychology, which show that out-group antagonism can develop independently of in-group favoritism (Brewer and Brown Reference Brewer, Brown, Gilbert, Fiske and Gardner1998; Zhong et al. Reference Zhong, Phillips, Leonardelli and Galinsky2008). What holds these partisan identities together—whether positive or negative—are political linkages. As Kitschelt (Reference Kitchel2000) outlines, these take three main forms: programmatic (based on shared policy preferences or ideological narratives), clientelistic (exchange of goods for support), and personalistic (loyalty to individual leaders rather than parties). In this sense, the function of political parties becomes critical. As Aldrich (Reference Aldrich1995) famously argued, parties exist because they solve two problems: the collective action problem (mobilizing participation) and the social choice problem (organizing preferences into coherent governance). A party that successfully mobilizes a positive partisan identity often does so by creating stable linkages—programmatic (resolving social choice) or clientelistic (resolving collective action). In some cases, it does both. If charisma is added to the mix, personalistic linkage enters the picture as well.

But what happens when parties weaken or collapse? Clientelistic linkages often break down, but personalism and ideological cues may persist. In these contexts, negative partisanship thrives. Yet—and this is the critical point—negative identities do not generate clientelistic linkages, since they normally lack an organizational base. One cannot distribute pork-barrel goods or targeted benefits through rejection alone. What they can generate, however, are programmatic oppositions (“anything but the Communists”) and personalistic rejections (“anyone but Kast”). The affective force remains, but the organizational channel is asymmetric.

Thus, in the framework I develop, positive partisan identities may be sustained through any combination of programmatic, clientelistic, or personalistic linkages. Negative partisan identities, by contrast, rely only on programmatic/ideological and/or personalistic linkages. (For example, a voter may reject the Communist Party not because they adhere to a coherent right-wing agenda, but because they oppose redistribution or associate the communists with “chaos”—a programmatic cue.) This helps explain why, even in the absence of stable parties, voters continue to express ideological coherence: not because ideology has become a social identity, but because it remains the essence of a programmatic political linkage—especially when deployed in opposition.

Ideology, as the basis of a political linkage, can operate along two dimensions: a policy-based (operational) one and a symbolic one (Ellis and Stimson Reference Ellis and Stimson2009). The former reflects preferences on concrete issues such as taxation or feminism; the latter refers to abstract labels like “left” or “right,” used as identity shortcuts. In institutionalized systems, both dimensions can reinforce partisan attachments, whether positive or negative. Yet this is not the same as ideology functioning as a social identity. For ideology to escalate into that terrain, it must be internalized as an in-group reference—something that shapes how people see themselves, others, and their place in society, well beyond electoral behavior.

This conceptual framework (outlined in Figure 1) has significant implications. It cautions against interpreting ideological consistency in survey data as evidence of deep social identities—especially in weak party systems. More plausibly, what endures are programmatic linkages sustained through negative partisan identities. These are fully capable of deploying polarization and structuring vote choice, even in the absence of in-group belonging and collective pride. Also, it provides a diagnostic lens for understanding party systems under stress. In contexts like Chile (or Peru), where partisan institutions have lost their organizing capacity (and are unable to fulfill collective action functions), political behavior is increasingly shaped by symbolic boundaries, antagonism, and personalism. Ideology persists—but more as heuristics than as a social category. Sometimes ideology is less about who we are, and more about who we are not. As we will see in the next section, applying this perspective to recent Chilean politics reveals a far more nuanced—and empirically plausible—picture than the article reviewed allows.

Ideology or (Anti-)Identity? Mapping the Geometry of Political Rejection in Chile

If the Chilean electorate were structured around cohesive ideological identities—where “the left” and “the right” function as sociopolitical tribes—we would expect party alignments to follow clear and predictable patterns. Yet the empirical landscape suggests otherwise. A growing body of work (Bargsted and Maldonado Reference Bergstedt and Maldonado2018; De la Cerda Reference De la Cerda2022) argues that what has eroded in Chile is not just partisanship but the authoritarian/democratic cleavage that once gave it meaning. Without that anchoring, partisan attachments have frayed, compounded by elites’ failure to articulate new, durable identities (Luna Reference Luna2016). What has emerged instead is a form of disjointed polarization: ideological divergence among elites, with voters remaining alienated and affectively mobilized (Luna Reference Luna2024). Even programmatic parties, as Contreras (Reference Contreras2025) shows, increasingly rely on clientelistic linkages at the local level to avoid electoral marginalization. The result is not identity loss, but a surplus of negative identities—where voters define their preferences more by rejection than by affiliation.

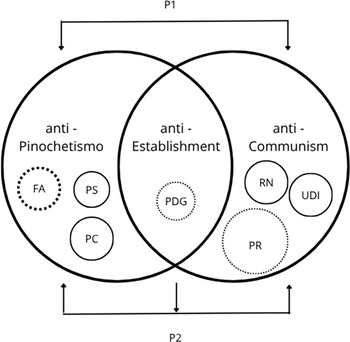

This helps explain why partisan and ideological maps in Chile now resemble overlapping Venn diagrams of rejection, as shown in Figure 2. Unlike frameworks that assume tidy ideological camps, this model starts from a more grounded premise: Chilean voters are more defined by whom they reject than by whom they support. The same voter who supports redistributive policies may reject communist candidates outright. A right-leaning voter may leave traditional parties (UDI, RN) not out of ideological deviation, but because of disaffection with their moderation. And formations like the Partido de la Gente thrive precisely by channeling anti-establishment sentiments that defy left-right categorization altogether. As Segovia (Reference Segovia2022) reminds us, even “non-identifiers” are politically expressive—not because they love someone else, but because they reject with gusto. These dynamics echo the broader Latin American pattern of partisan uprootedness (Sánchez-Sibony, Reference Sánchez-Sibony2024), polarization (Sarsfield et al. Reference Sarsfield, Moncagatta and Roberts2024), and reinforce findings from Visconti (Reference Visconti2021) and González-Ocantos and Meléndez (Reference González-Ocantos and Meléndez2024) that ideology still matters—especially in high-stakes moments—but increasingly operates through the grammar of rejection rather than affiliation. In short, it is not that Chileans no longer care; it is that they care a great deal about who should not win.

Figure 1. A Conceptual Architecture for Linking Voters and Parties.

Figure 2. The Ideological Geometry of Negative Partisan Alignments in Chile.

Fortunately, the question of negative partisan identities in Chile is no longer a theoretical novelty—it is part of a sustained research agenda that has been drawing attention to these dynamics for several years now. In previous work with Rovira, we proposed a framework to understand the persistence of negative political identities even in the absence of strong partisan loyalties (Meléndez and Rovira Reference Meléndez and Rovira2019). Our typology does not only classify voters by the coalitions they support, but more importantly, by the coalitions they explicitly reject. One of our central findings was that these negative coalitionary identities were not merely oppositional—they were also ideologically cohesive. In other words, the rejection of a political force (e.g., Chile Vamos or the ex-Nueva Mayoría) was structured around consistent ideological political linkages. People may not all agree on what they support, but many do share a clear and ideologically grounded sense of what they oppose.

This line of research has been fruitfully extended by Sajuria and Titelman (Reference Titelman and Sajuria2024), who show that “independent” identity in Chile reflects more than just ideological distance from existing parties. It channels a deeper rejection of the political establishment that often transcends ideological divides altogether. Voters who support independent candidates do so not because they are ideologically adrift, but because they are united by what they are against: parties, elites, and the traditional political class. This helps explain the appeal of anti-systemic candidates on both left and right, and why a self-described independent can attract voters from across the ideological spectrum.

Let us now turn to the diagram (Figure 2) for a more concrete illustration of how partisan rejection is structured in contemporary Chile. This figure offers an informed hypothesis—not a definitive mapping—that invites empirical testing. Two main axes structure the space. The first (P1) aligns with historical antagonisms: anti-Pinochetismo and anti-communism. These are not ideological identities in the thick, communal sense. They are rejection coordinates—anchored in shared memories, moral boundaries, and enduring discomforts. Pinochetismo and communism survive less as coherent ideological platforms than as specters to be exorcised from the political field. The second axis (P2) cuts orthogonally across the first: anti-establishment rejection. This is the terrain of diffuse political distrust—neither left nor right, but allergic to both. It is within this zone that actors like the Partido de la Gente and presidential candidates such as Franco Parisi seek to thrive—not through a programmatic offering, but through a posture of disdain. What they represent is not a clear ideological proposition, but a collective shrug of disgust that goes beyond the left and the right.

Within these rejection fields, however, some positive partisan identities persist—or attempt to emerge. The Socialist Party (PS) and Communist Party (PC) remain within the anti-Pinochetista zone, represented in the diagram with solid circles, signaling their status as consolidated, longstanding partisan in-groups. Frente Amplio sketches its position more tentatively, depicted with dotted lines to indicate a partisan in-group in formation, whose symbolic boundaries remain fluid. On the other side, UDI and RN coexist with the Partido Republicano in the anti-communist quadrant, forming an uneasy coalition marked more by rhetorical competition than substantive ideological divergence.

Crucially, these zones are not hermetic. Voters often inhabit multiple rejection fields simultaneously—against what the legacy of Pinochetismo represents today, against the perceived fears of Communist threats, and against the political establishment as a whole. These are not mere ideological differences, but distinct affective orientations that reflect discomfort with both historical legacies and contemporary actors. This multidimensional antipathy does not signal ideological incoherence; it reflects emotional consistency. The language of ideological alignment loses traction in this context. Voters are not drawing directional lines toward political centers; they are drawing affective circles around what they want to exclude.

This diagram does not claim to capture all the complexity of partisan behavior. Rather, it offers a stylized hypothesis that should be subjected to empirical verification. But it does offer a compelling reinterpretation: that ideological stability in Chile may be less about belonging and more about boundary maintenance—less about who one is, and more about who one is not. As Nicanor Parra once wrote—perhaps with uncanny foresight—“la izquierda y la derecha unidas jamás serán vencidas.” Not because they have fused into a common front, but because they are often rejected in tandem by the same disenchanted citizens.

This emotional architecture of rejection, sketched conceptually in Figure 2, now invites empirical scrutiny. If political behavior in Chile is indeed structured more by opposition than by belonging, we should see evidence of these negative identities operating in measurable ways—shaping vote choice not merely through ideological affinities but through aversions. While this memo does not offer a full empirical test—nor should it be read as such—it draws on existing evidence to assess the plausibility of an alternative hypothesis: that ideological stability may be better explained by the strength of affective rejections rather than by the consolidation of cohesive ideological in-groups. The next section moves in that direction, drawing from real-world data on anti-communism, ideological positioning, and electoral behavior. What follows is not just a test of theory, but a provocation: what if rejection is doing more of the work than we think?

Beyond Ideological Identity: Measuring Anti-Communism and the Power of Rejection

If ideological self-placement meaningfully structures political behavior—whether or not it reflects a fully developed social identity—then we would expect it to exhibit robust, independent predictive power in electoral outcomes. And indeed, to Arcote and Visconti’s credit, the 2018 LAPOP data shows that self-placement on the left-right scale correlates with support for Sebastián Piñera in the 2017 election. But the presence of ideological identity in a social-psychological sense remains an open question.

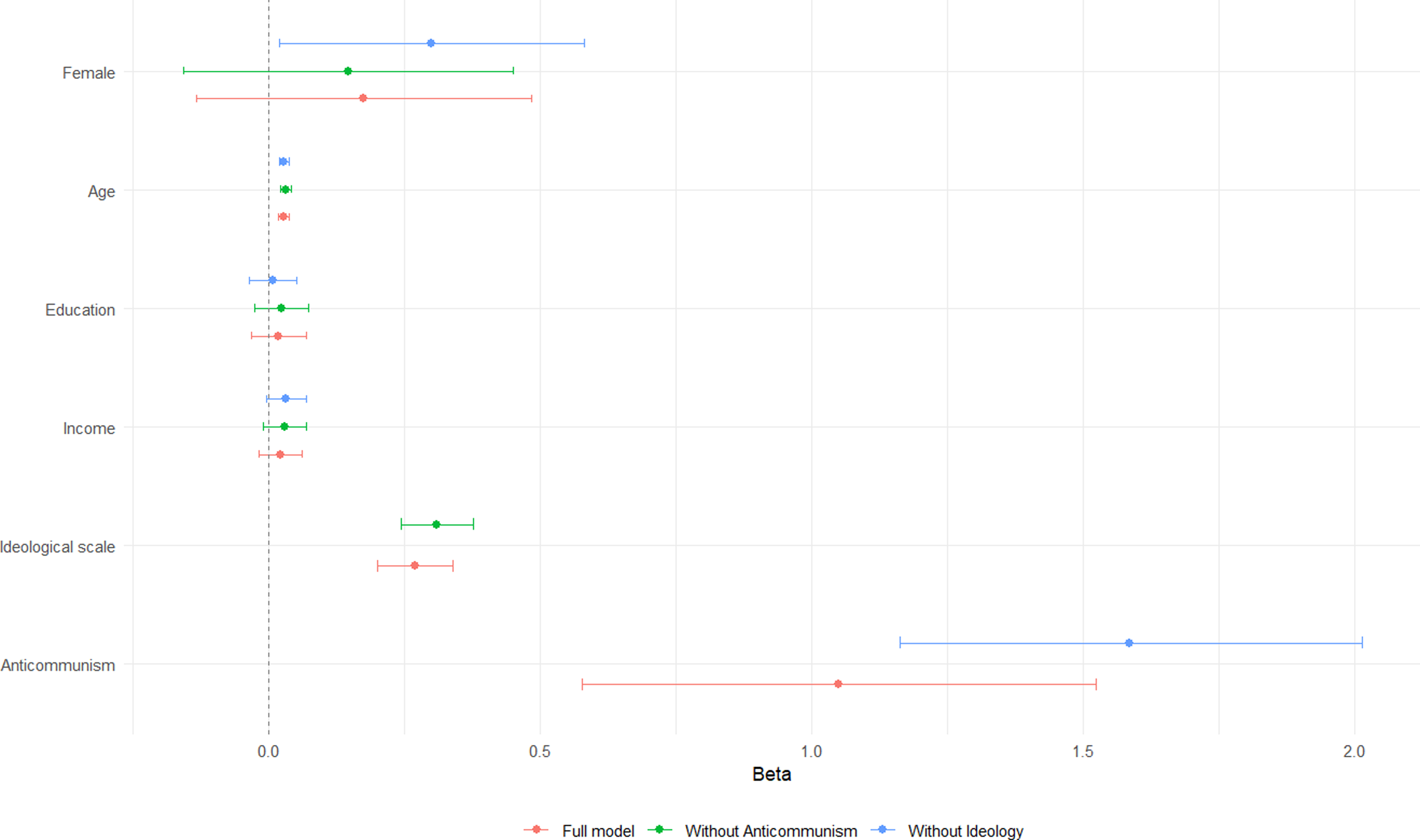

Figure 3 presents a logistic regression model of the vote for Piñera, using two key predictors: ideological self-placement (the authors’ preferred proxy for social identity) and a negative partisanship indicator—specifically, whether a respondent stated they would “never vote for the Communist Party.”Footnote 1 Both variables are statistically significant, even when controlling for standard sociodemographic covariates. While ideological placement may reflect policy preferences or habitual alignment, the anti-communism variable reflects an explicitly rejection. One cannot infer a cohesive in-group from the ideological scale alone. But stating that one would never vote for the Communist Party suggests a clear symbolic boundary has been drawn—an out-group has been identified.

Figure 3. Explaining Support for Sebastián Piñera (2017): The Predictive Power of Ideological Positioning and Anti-communism (LAPOP 2018).

Of course, we should admit that the “never vote for” item is a blunt instrument. It captures rejection, but not its emotional tone, intensity, or ideological consistency, which is why it is necessary a step further. In a collaborative study (Rovira et al. Reference Rovira, Espinoza, Meléndez, Tanscheit and Zanotti2024), we designed a more nuanced measure of anti-communist attitudes, based on three original items: (1) whether respondents believe communism contributed positively or negatively to Chilean history; (2) whether they feel admiration or contempt toward it; and (3) whether they associate communism with love or hate. These were measured on 1-to-5 Likert scales to capture gradations of affect and historical memory.Footnote 2

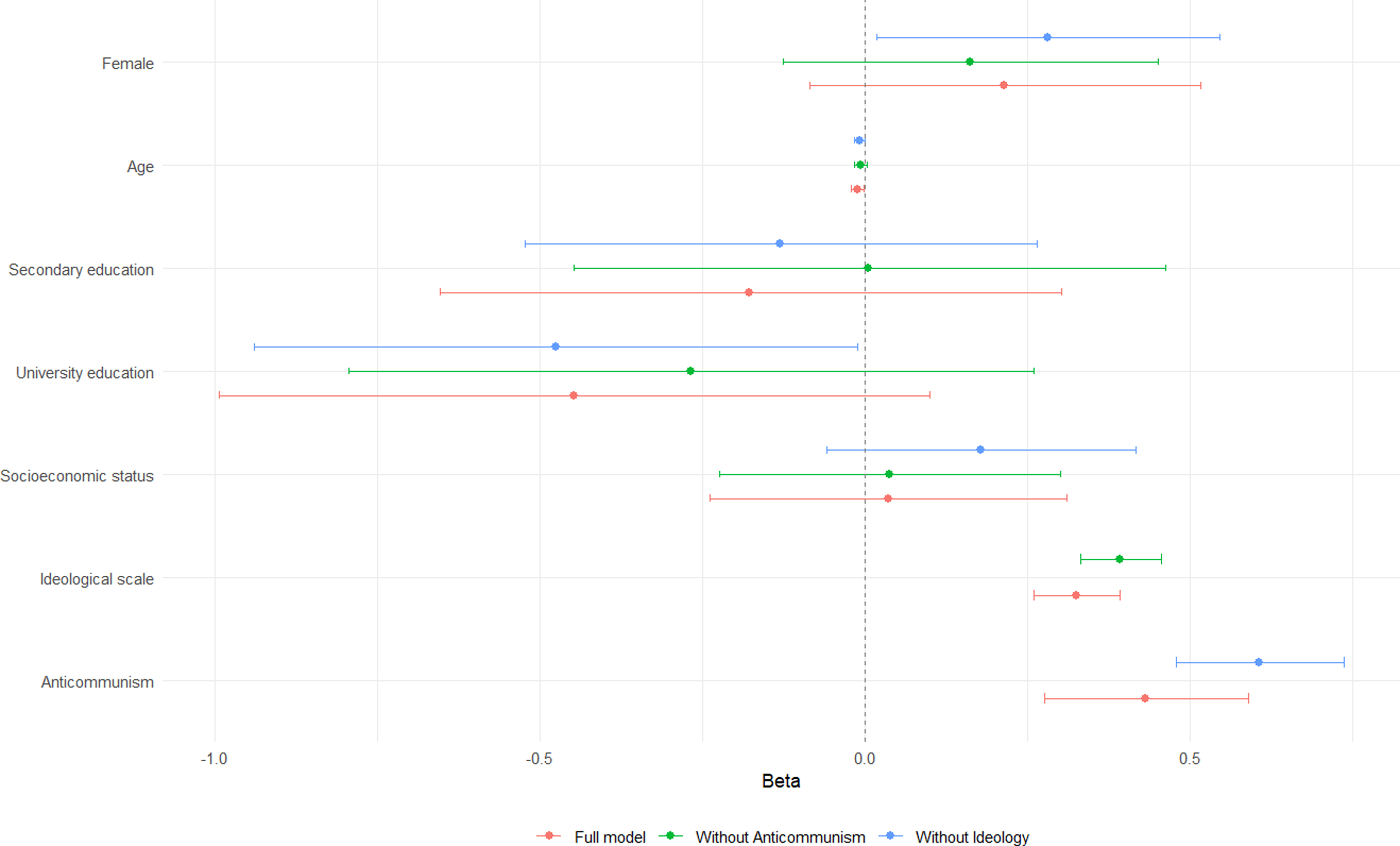

Figure 4 shows how this multidimensional anti-communism scale predicts support for José Antonio Kast in the first round of the 2021 presidential election. The results are, frankly, striking. Anti-communism significantly predicts the vote for Kast—even after controlling for ideological self-placement and a full battery of sociodemographic controls. In short: rejection works, and it does independently of where you say you fall on the left-right continuum.

Figure 4. Explaining First-Round Support for José Antonio Kast (2021) by Logistic Models Using a Multidimensional Anti-communism Scale.

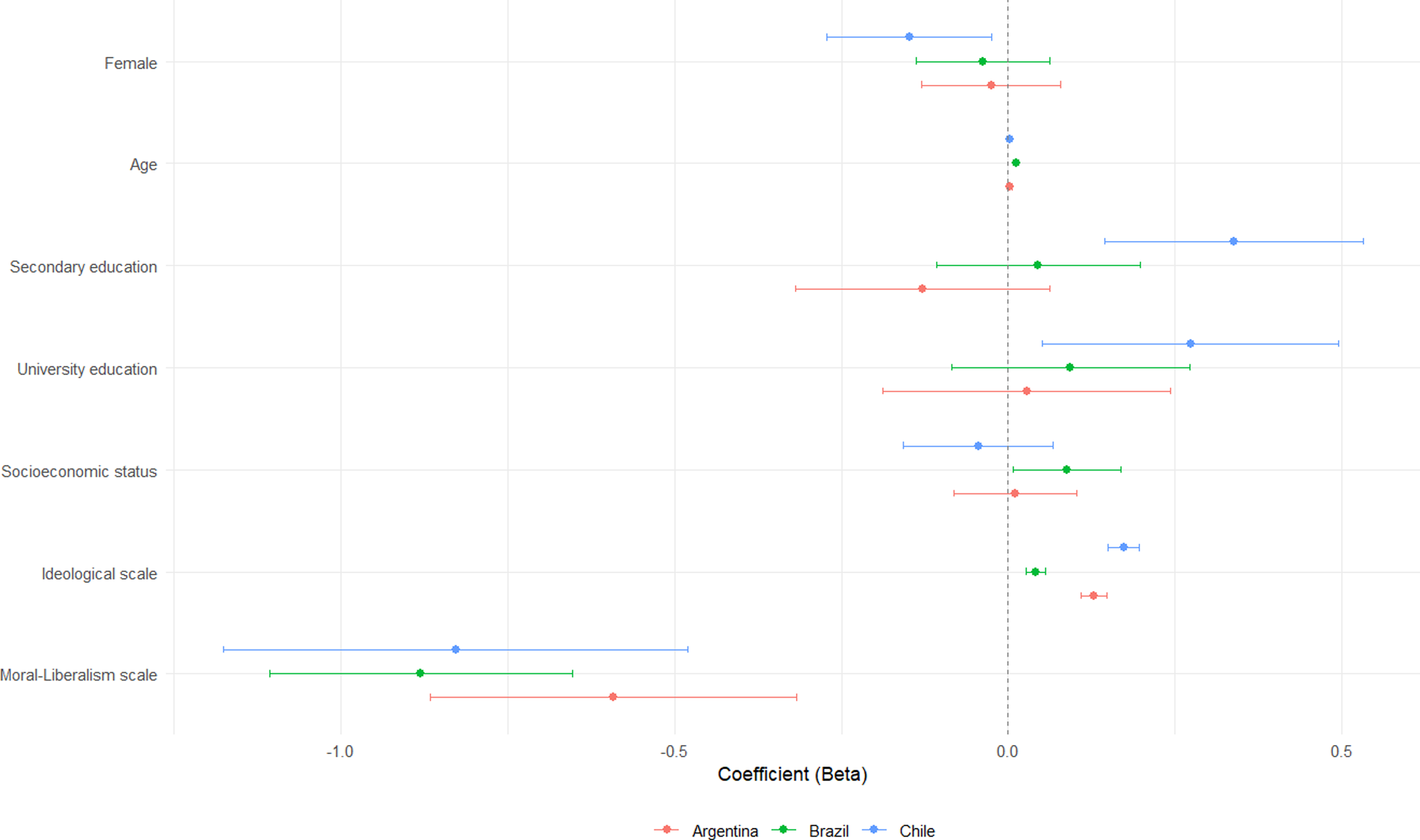

This brings us to a broader point. When we speak of negative partisan identities, we are not simply describing surface-level opposition or short-term affect. We are pointing to structured, coherent, and measurable orientations that are at least as consequential—if not more—than the supposed ideological identities people are assumed to carry. Figure 5 expands the analysis comparatively, using the same multidimensional anti-communism scale as a dependent variable across contemporary Chile, Brazil, and Argentina.Footnote 3 Consistent across countries, anti-communist attitudes are strongly associated with right-wing ideological positioning and, perhaps more revealingly, with moral conservatism. This holds even after controlling for income, education, age, and other demographic factors. In all three contexts, anti-communism is not just a free-floating prejudice. It is rooted in a broader symbolic and normative worldview—one that transcends specific parties and travel surprisingly well across borders.

Figure 5. Comparative Predictors of Anti-communism in Chile, Brazil, and Argentina.

A promising direction for future research on political behavior in Latin America lies in the study of negative partisan identities. As party systems across the region continue to fragment, the traditional anchors of political identity—party labels, stable in-parties, and coherent ideologies are eroding. What increasingly persists are negative partisan identities: emotionally resonant, politically mobilizing, and often structured around rejection rather than affirmation. This is not a Chilean anomaly, but a regional pattern. Yet Arcote and Visconti’s article (Reference Argote and Visconti2025) represents a desire to interpret ideological stability—which undeniably persists as a political linkage—as evidence of social identity formation. When that interpretation becomes difficult to sustain, the discussion sometimes drifts into analytical shortcuts—resorting, for example, to familiar tropes such as the “Peruavinization” of politics (Barrenechea and Vergara Reference Barrenechea and Vergara2023), as if the simultaneous occurrence of polarization and fragmentation were a pathology unique to Peru rather than a broader regional phenomenon.

My view is different. What Chile shares with Peru, Brazil, Argentina, and beyond is not a collapse into chaos, but a reconfiguration around negative partisanship. These identities may be directed against communism, Pinochet’s legacy, the political establishment, or all of the above. They do not depend on in-parties to function; they only require out-parties. And they may very well be the most powerful forces structuring political behavior in Latin America today. To study these identities genuinely, we need better tools. We must go beyond the insufficient proxy of ideological self-placement and develop multidimensional, comparative measures of rejection—tools that help us understand how voters construct meaning through opposition. Otherwise, we will continue mistaking stability for identity, ideology for affect, and surveys for sociology. Therefore, anti-communism is not just a Chilean quirk. It is a regional (and world-wide) lens. And unless we treat negative partisan identities as central objects of study—rather than residual noise—we risk missing what might be the defining feature of political behavior in the post-partisan democracies of Latin America: we do not always know what we are, but we are increasingly clear about what we are not.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Lisa Zanotti, Jesús Guzmán, and Julia Cavieres for their valuable comments on an earlier draft of this text. This research was supported by the Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia (FCT), under the project “Populist appeals and negative partisanship. A cross-regional comparison between Latin America and Southern Europe” (Grant reference: 2023.08788.CEECIND/CP2882/CT0006, DOI: https://doi.org/10.54499/2023.08788.CEECIND/CP2882/CT0006)

Competing interests

The author declares that he has no competing interests.