Introduction

In discussions of UK food charity, we increasingly see calls to acknowledge and accurately document the diversity of provision, ranging from referral-based to open-access projects, to organisations providing only food, to others promoting a ‘more than food’ approach. Different models, such as ‘food pantries’, can be seen to offer a less stigmatised, more dignified service, and are often promoted as a possible direction for food charity in a context where millions of households cannot afford essential items. This article explores how this supposedly diverse sector is perceived and experienced by those accessing it. We draw upon longitudinal interviews conducted between January 2023 and November 2024 with a demographically diverse sample of 62 people living on a low income in the north and south of England. In doing so, the article counters and goes beyond existing scholarship, questioning narratives of choice and diversity in the food aid ‘sector’, and at the same time, centring demographic inequalities. The findings point to a disjuncture between lived experiences and academic presentations of food aid, highlighting the principal role of demographic inequalities, not ‘type’ of provision, in shaping lived experiences of the UK community food aid sector.

A diversity of provision? The growing range and professionalisation of UK food aid

The rapid expansion of food banks in the UK has underpinned growing scholarship critiquing the emergence of a food bank sector. Unlike North American and many European food banks that store and redistribute (surplus) food to charitable organisations, UK ‘food banks’ refer to centres that collect, warehouse and distribute food for free to people directly (Lambie-Mumford and Silvasti, Reference Lambie-Mumford, Silvasti, Lambie-Mumford and Silvasti2021). British scholarship has focused on the limited potential of food banks to address food insecurity (Loopstra and Lambie-Mumford, Reference Loopstra and Lambie-Mumford2023), their instrumental role in welfare state retrenchment (Lambie-Mumford, Reference Lambie-Mumford2019) and their internal replication of discourses and practices associated with the welfare state apparatus (May et al., Reference May, Williams, Cloke and Cherry2019). Scholarship has highlighted constructions of deservedness and dependency underlying the organisational practices of many UK food banks (Strong, Reference Strong2019) in which food banking systems, including referral pathways and limitations on the quantity and regularity of food received, create artificial divisions between those deserving and undeserving of support.

Alongside these broadly critical analyses of food aid, there are growing attempts to define and disaggregate the UK food aid ‘sector’ (Benchekroun et al., Reference Benchekroun, Previdoli, Burton, Doherty, Kapetanaki, Hadley, Power and Bryant2024; SALIENT, no date). Scholarship has highlighted the breadth and diversity of provision, going beyond food banks, to incorporate varied organisational structures and forms of food distribution; including, for instance, community gardens, social supermarkets and food pantries, urban farms and community kitchens (McEachern et al., Reference McEachern, Moraes, Scullion and Gibbons2024; Saxena and Tornaghi, Reference Saxena and Tornaghi2018). Unlike food banks, which tend to operate via referral systems, a majority of this provision does not utilise referral pathways, either administering alternative forms of eligibility criteria – for instance, a geographical catchment – or functioning on an open-access basis. Much of this literature argues for the superiority of non-food bank provision in addressing the underlying causes of food insecurity, upholding dignity and promoting ‘community resilience’ (Nayak and Hartwell, Reference Nayak and Hartwell2023; Saxena and Tornaghi, Reference Saxena and Tornaghi2018). The diversity of the food aid sector is considered an asset; diversification beyond the food bank model towards organisations which sell food at low or symbolic prices (social supermarkets and food pantries) or incorporate sociability or skills development into food provision (community or social cafes) provides scope to tackle individual and community ‘resilience’ through food (Blake, Reference Blake2019).

This shift from critiquing food banks to classifying alternative forms of community food provision aligns with a political and policy landscape which, throughout the rapid growth of food charity, has largely ignored the socio-economic drivers of use, instead advancing food-oriented solutions. For example, the Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities recognised the need for affordable, accessible and healthy diets in their White Paper (2022) but responded that it would ‘take forward recommendations from Henry Dimbleby’s independent review towards a National Food Strategy including piloting Community Eatwell and a school cooking revolution’ (ibid: 12). Similarly, in their Food Strategy White Paper, the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs highlighted the contribution played by local food partnerships, bringing together councils, community groups and businesses in ‘addressing food affordability and accessibility to healthy food’ (2022). The use of the Household Support Fund, initiated by the Conservative Government and continued by the new Labour administration, to directly fund local-level food banks (City of Bradford Metropolitan District Council, 2024) accords with a policy landscape promoting food-based solutions to poverty.

The community and voluntary sector response to financial insecurity and destitution aligns with a broader fragmentation of poverty in which academics, policy makers, politicians and voluntary sector providers talk not of a problem of poverty but of ‘food poverty’, ‘hygiene poverty’ or ‘furniture poverty’ (Child Poverty Action Group, 2020). These disaggregated forms of poverty risk obscuring the fact that all these supposedly different types of poverty are about the absence of sufficient income to afford the essentials, triggering a partial and sometimes paternalistic and stigmatising response (Patrick et al., Reference Patrick, Power, Garthwaite, Kaufman, Page and Pybus2022). It also accords with broader social policy trajectories of increasing targeting, means-testing and conditionality of social security (Wright et al., Reference Wright, Fletcher and Stewart2020) and a steady shift towards welfare pluralism in which, as the state withdraws from welfare provision, the mixed economy of welfare – involving private, voluntary and informal sectors – becomes ever more important (Powell, Reference Powell and Powell2019).

The paper explores how this apparently diverse food aid sector is perceived and experienced by those accessing it. Reflecting the aims of the wider project (see: foodforthought.page), it examines the impact of gender and parenthood, race and ethnicity and age on lived experiences. There is significant scholarship on the lived experience of food bank use, documenting the stigma inherent to seeking support (Garthwaite, Reference Garthwaite2016; Purdam et al., Reference Purdam, Garratt and Edmail2016) and the hope, solidarity and care that can arise within food bank encounters (Stambe and Parsell, Reference Stambe and Parsell2023). Nevertheless, beyond attention to class and income, through analyses of power (Strong, Reference Strong2019), alongside select key studies on gendered experiences of food aid (Beatty et al., Reference Beatty, Bennett and Hawkins2021; Spellman and McBride, Reference Spellman and McBride2025) – to which this study adds a sharper focus on parenthood – there has still been relatively little focus on inequalities in respect of lived experiences of food aid. A growing body of work on race, ethnicity and unequal food bank experiences forms a similarly vital empirical and intellectual context for this article (Hamilton et al., Reference Hamilton, Thompson and Wills2022; Power, Reference Power, Doherty, Small, Teasdale and Pickett2017, Reference Power2022; Power and Baxter, Reference Power and Baxter2024). The tendency to compartmentalise research on different ‘types’ of provision has also culminated in a research landscape which documents how people use a particular type of provision rather than how they navigate a ‘food aid sector’. Drawing upon a large longitudinal study, this paper addresses these gaps.

Methodology

The article emerged from a 4-year mixed methods study examining food insecurity, inequalities and mental health in England. The qualitative fieldwork took place in three cities, two in the north of England (Bradford and York) and one in the south (London). These cities were chosen for their different demography – York a more affluent and largely white British city, albeit with pockets of deprivation; Bradford a city of high deprivation, with a large Asian and Asian British population (32%) (Office for National Statistics, 2023); and London a place of extreme wealth and income inequality and the most ethnically diverse region of the UK (Trust for London, 2023).

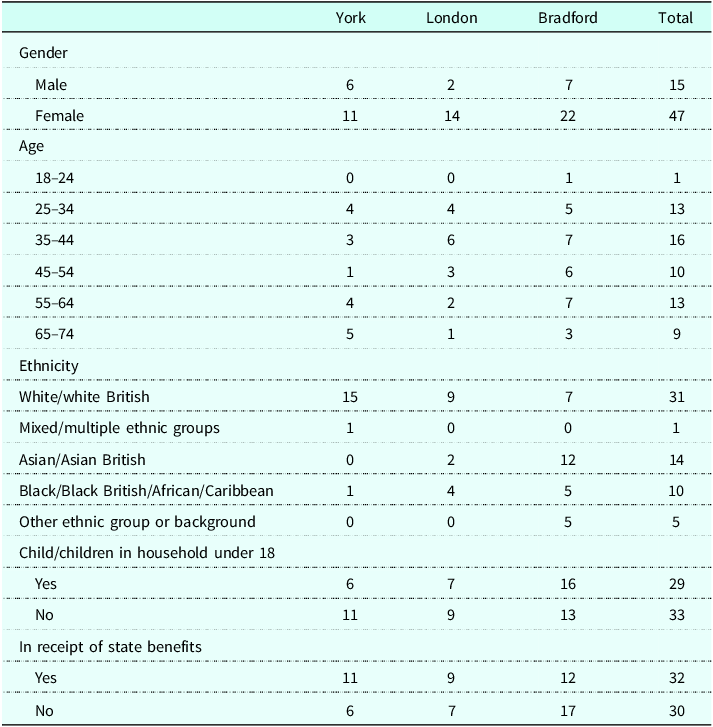

Participants were recruited through community groups, advice centres and snowball sampling. Purposive sampling was employed to recruit a diverse sample of adults living on a low income (self-declared). Recruitment materials were translated into multiple languages (Spanish, Urdu, Arabic and Punjabi) and a minority of interviews (n = 7) were conducted with a translator. Interviews took place between January 2023 and November 2024, with 6 months between each interview. In total, sixty-two people took part in Round 1 interviews, fifty in Round 2 and forty-five in Round 3, with interviews taking place in person, on the phone and on Zoom. The sample was a diverse cohort living on a low income (Table 1).

Table 1. Sample demographics

The interview schedule, which was co-produced with people with lived experience of food insecurity and mental illness, covered multiple topics, including food insecurity and food charity, mental health, access to health services and discrimination. The interview schedules for Round 2 and 3 explored the temporality of food insecurity and service use. Whilst drawing upon data from the three rounds, we do not go into detail about the temporality of food aid use as it is addressed elsewhere (Power and Baxter, Reference Power and Baxterforthcoming). All interviews were recorded and transcribed verbatim, and the data were analysed inductively using thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke, Reference Braun and Clarke2006). The study received ethical approval from a university ethics committee and ethics were a high priority before, during and after the interviews; the project team ensured that participants were fully aware about the nature of involvement before agreeing to take part, participants were able to stop the interview at any point and signposting was available. All participants provided informed consent before each interview; names are pseudonymised and identifying characteristics changed. In recognition of their time and expertise, participants were provided with a £30 voucher for each interview.

Results

Participants talked at length about the nature and experience of accessing community food provision. We consider participant’s categorisations of food aid before exploring the manifestation of inequalities in the lived experience of these services.

Uniformity of terminology

There was striking uniformity in the language employed by participants to describe the food aid organisations accessed. The term ‘food bank’ was used by participants of varied demography and geographies to describe non-food bank models of provision, including social supermarkets, food pantries and community cafes. Lee, for example, described the food pantry which he used regularly, an organisation in which food was chosen and purchased for low cost, as a food bank:

In recent months I’ve been to food banks and try and buy … for £5 you can buy £20 worth of food. You have to get there early. If you get there late there’s other people there as well. There’s also limited stock. So it’s not every week I can go.

The regularity with which the term ‘food bank’ was used to describe types of provision which did not fit the food bank model of largely ambient food, distributed to people for free, with minimal choice and frequently using referral systems, was striking; amongst many of those interviewed, ‘food bank’ had become a catch-all term for any charitable service providing free or low cost food to take away. Consistent use of the term ‘food bank’ to describe services with varied characteristics cohered with two further themes. The first was the normalisation of community food provision amongst some people who used these services. The prevalence of food aid at a local level rendered it an increasingly normal way to access food; many participants were aware of and used different organisations in their local area, again all labelled ‘food banks’:

It’s super close to me, I mean there are several dotted around the area, food banks that I see advertised, there is one down the road but I think that’s just for adults, I don’t know if they’ve got children but I think the one here is for families. – Michelle

The second related theme was regularity of food aid use amongst a significant minority of participants. According to 2022/23 data from the Department for Work and Pensions’ (DWP) Family Resources Survey (2024), a minority of households experiencing food insecurity used a food bank in the past 12 months (23%) and a smaller minority of those in food insecurity used a food bank in the past 30 days (10%). However, conversations with participants across the north and south of England suggest that the reality is more complex. Some people living on a low income use community food provision on a regular basis; this may be monthly, weekly or even daily. Whilst services are often loosely labelled ‘food banks’, in reality, people are often accessing a variety of organisations that distribute food in different ways – one uniting factor of these organisations is that they tend not to be accessed via referral pathways but are open access or employ geographic or demographic-based eligibility criteria. Lorena, in Bradford, described the regularity with which she accessed ‘food banks’, comments that were echoed by multiple participants:

We have had access to food banks once a month … We have to pay £3.50 for it, we, myself, eat most of the things, the kids not that much. We get things like sugar, coffee, sometimes washing powder, hygiene products like soap and that, sometimes bread and milk and fruit, maybe three/four bananas and some apples as well. I do also go to a church, the money is the same, the amount of money we have to pay but they give more fruit and sometimes they even provide you with some chicken.

For a minority of those using food aid regularly it was their main, if not only, form of food access:

You can go once a week, I think they’re meant to give you food for three days but the reality is if you meal plan properly and maybe it’s because I’m on my own, but they do change the limits of what you’re allowed. If you meal plan and you have a fridge and a freezer as well then you can definitely make food last for a whole week. – Olivia

Would that be the main form of how you’re accessing food or would you…? – Interviewer

Yeah, at the moment. – Olivia

Participants who described using community food provision regularly were not necessarily those living in the greatest hardship; in fact, it was common for participants accessing provision very regularly to have a low but steady income, in particular pensioners. A combination of regularity of use, particularly of open-access provision, and the increasing local and societal prevalence and awareness of hardship appeared to mitigate (some) of the stigma of food aid; this is not to argue that the stigma of seeking food support was not acute for many participants but that, for some people, the availability and increasing normalisation of food aid attenuated feelings of stigma and shame:

You would walk in and you would have a volunteer come in and they will start off with the dry foods, then the fresh fruit and they’re all good quality and you think about what was it like before the pandemic because all this food would go to waste, it’s such a waste and if it can go out to … I mean I’m not ashamed of it or anything because I know there are people like teachers out there or nurses that are still finding it really hard to, not access food as such, but they’re counting the pennies. – Michelle

Nevertheless, despite uniformity of terminology, participants differentiated clearly between the nature and quality of food aid, showing decisive preferences for specific attributes of services. Many participants navigated their local food aid system with skill, comparing services. There was clear preference for open-access provision; food choice; fresh, high-quality, in-date food; and a welcoming environment:

It’s a very, very thoughtful, well-run service in it’s set up like a shop, you’re paying your money, you go in and you choose. You can have five items of fruit and veg and five cupboard items and there are other services in other part … I had a friend who used to live in Croydon and she used a service and you were handed a bag of food, you know, worlds apart. – Paula

The data were rich with examples of structures and practices in community food services which rendered the experience stigmatising, and therefore we discuss this at length elsewhere (Power and Baxter, Reference Power and Baxterforthcoming). The point to emphasise here is that as the food aid sector evolves and expands, people are navigating across organisations with skill and discernment, calling attention to more and less stigmatising practices – practices which do not necessarily fall neatly along lines of service model/provision type – and highlighting nuanced differences between organisations, all whilst continuing to label most community-based organisations that distribute food as ‘food banks’. The importance of this finding is two-fold. First, language has meaning: the words people use to describe phenomena closely shape their understanding of those phenomena, which, in the context of poverty and food aid, may have implications for whether they seek help. Second, if service users continue to use the language of food banks (‘food bank’, ‘food parcel’ etc.), despite organisational and academic specificity to categorisations, it suggests that there is not only a difference in understanding but a conversational gulf between academics/organisational staff and service users. Nevertheless, the sharpest inequalities in experiences of food aid were delineated by demography, not type of provision, and we turn to this next.

Inequalities in lived experiences by age

Nationally representative data suggest that food bank usage amongst people aged over 60 years, and especially over 65 years, is low. According to the DWP’s (2024) 2022/23 Family Resource Survey, 4 per cent of households aged 60–64 years and 1 per cent aged over 65 years had used a food bank in the past year; this compares with 7 per cent of households aged 18–24 years. This qualitative study, however, suggests that these numbers may not capture the reality and complexity of food aid use by older people at a local level. Amongst participants, the use of community food provision varied markedly by age, with older people using open-access, non-referral services often on a weekly or daily basis:

So that’s where I’m at now but I’ve learnt a lot of ways to sort of save money really. I go to food banks. I could write a book on the food banks in this city really. I go to three separate ones and that has really helped because now I’m not spending very much money on food. – Nancy

Participants aged over 60 years often described visiting local food aid with friends; indeed, companionship appeared to be a key motivating factor:

Mondays, none … I pick another lady up called Sheila, on a Tuesday. Wednesday, I pick another lady up. These are ladies that really need to use a food bank. So on Wednesday we go to … first of all we go to … there’s a food bank nearby, that’s for tins. Then after that we go to another food bank. Yes, that’s Wednesday. Thursday, I pick June up and I pick my old age pensioner Betty, who’s very poor, frail on her feet and we go to St Mary’s first and then we go on to Derwenthorpe. It’s not so much going out and getting lots and lots of food for me, it’s going out for the companionship because that’s what I want to do, is meet them as well. If I can’t work I might as well be useful somewhere. Friday, I don’t do any food banks. – Margaret

Older participants routinely described regular attendance at charitable food organisations which themselves emulated what might historically be considered a community centre, a venue offering tea and coffee, low-cost meals, warmth and an opportunity to socialise:

I like coming here because there’s people that I meet and you get a cup of coffee and you can sit with people. So it’s not just about food here, it’s about not being isolated. Especially when … after all the lockdowns and things that were there … a lot of people were cut off and because they were cut off and not seeing … I don’t think people know what’s going on with them. When you come back here and you can chat to other people and you realise other people were cut off as well … that’s the good thing about here. – Karen

It was more common for older than younger participants to describe using community food provision in this way, accessing it regularly during the working week and spending long periods of time socialising and eating within the venue. Amongst older people in the sample, there was also a strong overlap between volunteering in and accessing a service. Younger participants, by contrast, whilst valuing open-access community provision over stigmatising referral systems, were more likely to describe navigating food provision amidst busy lives:

I don’t feel like I’m that bad off but it does help a lot, it helps because I haven’t accessed it for three weeks now because it’s just timing or events that are happening. I normally go on a Saturday or a Sunday because that’s the time when I’m off because I work five days a week, so it’s a hit and miss. – Michelle

It was notable that all participants aged over 65 years in the sample were in receipt of a state and/or private pension. This low but steady and unchallenged income, and separation by age from the expectation of paid employment, may have mitigated the stigma of food charity:

Well it’s great because I plan my week … because I’m not allowed to work and earn any money which is sad, because all us old age pensioners would like to earn a little bit more money. Obviously when we’re on benefits and pension credit we’re stopped. So we’re useful but we’re not allowed to do anything apart from voluntary work which I’m looking into. – Margaret

Receipt of a state pension appeared to attenuate the extent of poverty and food insecurity experienced by older people and cemented solidarity amongst ‘old age pensioners’ living on a low income, further solidified via encounters between older people in food aid: I think everybody’s in the same boat who come here, they’re all same so some are pensioners and stuff like that and I think it’s good for them, so they’re getting out meeting people and things like that. – Heather

This contrasted sharply with the unpredictable and qualified income of participants in receipt of working-age social security, a highly conditional income which sharpened the stigma of poverty and associated use of food aid.

Inequalities in lived experiences by gender

Whilst a study of the lived experience of inequalities, this research did not intend to be a study of gender, and we therefore did not purposively recruit a sample incorporating an equal split of men and women. A much higher proportion of the sample was female (76 per cent), which may speak to gendered responsibilities for food, and women in the sample were more likely than men to use or have used community food provision – nationally representative data, by contrast, suggest that use of food banks by men and women is broadly similar (DWP, 2024). The shame and stigma of accessing food charity was discussed with regularity by both men and women. There was evidence of pride and shame, which inhibited some male participants from accessing food charity:

Well to be honest with you, I’m not the kind of person that likes asking, if you know what I mean? Because, obviously, I’ve worked you see. And it’s like, do you know, I think there’s always people that are worse off than me that probably need the service as opposed to me. Because, obviously, I’ve got a bit of family that I can fall back on. I mean I’ve got, like, brothers. Well, I’ve got a brother, one of the brothers he’s not around at the moment. But my other brother he’s like a massive financial consultant. So, he’s doing really, really, well. And two of my sisters are pharmacists, the other one is a barrister. So, do you know, we do … we’ve done very well in the family anyway. – Imran

Nevertheless, a gendered form of male pride was a rare theme in the data as a whole and therefore could not be deemed a ‘shared typical’ (Weber, Reference Weber1978). The interaction of gender and food aid was at its sharpest in cases of parenthood. In this study, as in society (Women and Equalities Unit, 2021), women were more likely than men to be the primary carer for children and therefore the impact of parenting on experiences of food charity was a particularly dominant theme amongst women. The presence of children in the household influenced how and when food charity could be accessed – for instance, restricting parents to school times and limiting how long they could stay in the venue for a meal or to socialise. It also circumscribed the usability of the food received. In households with children, much of the food from charities was redundant; poor-quality or tinned foods that parents might force themselves to eat were decisively spurned by children:

You know this food parcel, they give a food parcel, you know. These children are demanding you understand. Like we know like beans, you know, yeah in the UK they have their beans inside the can, but my children will not eat. They will not eat the food you understand … My children said, “No mum, no, I’m not eating this food.” So mama was like saying, “It’s good, it’s that, it’s good.” Then my son said, “I don’t have the strength of eating this food.” – Adeola

Parenthood could also sharpen the shame of food charity. Returning home to children with food bank parcels was an admission of failure as an adult and parent; participants spoke of their perception of judgement of both adults and their own children:

I try and use food banks but because of my local area it’s kind of embarrassing because you feel like everyone is watching you. You feel ashamed, especially if you have children. Because I was working before, I had my children and people just assume that, “Oh, why did you have them if you couldn’t afford them?” When you try to explain, “I used to work, I used to earn money before I was in this situation,” they don’t see it like that. Yeah, because they think oh, you just wanted to be on benefits and claiming on food banks and stuff. So it’s very embarrassing to stand there and wait in the queue. I went there once last week, and I was so embarrassed, extremely embarrassed. When I came home with the shopping, I took the shopping upstairs and I went to collect my daughter. My daughter came to look in the bags, like, things that I don’t buy. She said, “Where did you get them from?” I had to explain to her and it’s really ashaming to tell your child that you have to go and beg for food. – Aisha

This feeling of failure as a parent could have a profound impact on mental health, of both adults forced to feed their children food they know they do not want and children obliged to consume food they neither enjoy nor would choose:

For example if you bring this food and put it in front of your children and they said, we don’t want this food, we don’t like it. And you keep giving it to them and … they said, why, we want so and so … And you yourself feel sad and you force them to eat this food and they don’t like it. They themselves ask, we don’t like it, we don’t want it. So it really affects their mental health and it affects our mental health as parents. – Omar

This is not to argue that gender in itself did not impact experiences of food charity but, in this study, gender interacted with parenthood to render the experiences of food provision particularly stressful and shameful for mothers.

Inequalities in race, ethnicity and country of origin

There were marked racial inequalities in lived experiences of food aid, with people from minoritised ethnicities and those born outside the UK, who were more likely to be people of colour, marginalised and subject to discrimination. The manifestation of racial discrimination in community food provision was, nevertheless, complex and multifaceted. Previous research has called attention to the cultural inaccessibility of food distributed within food aid, demonstrating a tendency to provide food which aligns with white British cultural norms (Power et al., Reference Power, Doherty, Small, Teasdale and Pickett2017); in this study, multiple participants described the absence of culturally appropriate food, especially halal and West Indian food:

From these churches, we get help as well when they sell like for £5 fifteen items but sometime we got a problem because you can’t buy every single thing from the church because it’s, some of it’s halal, a lot of items you can’t buy them because we can’t eat them. So we can eat like chickpeas, fruit item but the other item when you got pork, these things, we can’t eat them. – Noor

Asylum seekers were particularly likely to call attention to the cultural exclusivity of the food distributed; multiple participants who were asylum seekers explained that the canned food provided by food banks was not food they were used to eating and was consequently rejected by their children:

When we came in first, we went to food banks … And plenty is still in my house. The cans are still in there because they will not eat it. So the ones that they are eating like pasta, fruits or something because my children love fruits … So all this canned food it’s okay but the children are not used to it. – Adetola, an asylum seeker

There were examples of cultural inclusivity, including food banks providing halal food parcels; Asian supermarkets donating to food banks, increasing the diversity of the food on offer; and staff members, themselves recent migrants, cooking and distributing food from their country of origin: My granddaughter loves her [the staff member’s] jalfrezi rice what she makes … They like curries and stuff like that and I said, “Oh, she wants some of more of that rice,” so she brought me a bag of food. – Heather

Nevertheless, these were aberrations rather than the norm. There was also no evidence of staff and volunteers in community food provision asking people about their cultural food preferences and no discussion amongst participants of adaptations in response to food which was perceived as culturally inappropriate.

The steady expansion of the community food sector has been coupled with its growing informality, marked by an increase in the proportion of organisations unaffiliated to a larger organisation or body (such as Trussell or the Salvation Army) distributing food on an open-access, non-referral basis. Simultaneously, the amount of food available to distribute has become ever more pressurised as demand increases whilst supply shrinks. These two trends give rise to a third: increasing scope for the subjectivities of staff and volunteers in community food provision to influence who receives food and how much is received. Conversations with participants suggested that racial stereotypes and prejudices could inform staff attitudes towards those using the service. This included examples of white British staff marginalising Black and Minority Ethnic (BAME) service users: There is one guy that goes there, they don’t treat him good because of the colour of his skin … She used to be funny with me as well when I used to have my child with me for the same reason because my child is mixed. – Sophie

In addition, it includes South Asian volunteers making racialised judgements about both South Asian and white British people attending food aid, as exemplified by Parveen, a service user and volunteer:

So the community that I come from, the Asian community, I think because of the way we were back home, the desperation, lack of food, we’ve become a bit greedy in that sense and … Because I know because I come from inside … and I do know sometimes people have just become greedy and selfish and they’ll just take things home that they don’t need just because they’re cheap and just because they’re there. So in that sense I had to sort of make decisions because I knew some of the families with young children, they would miss out and these people wouldn’t, if that makes sense … It was a judgment but it was like an informed judgment that I know some of the behaviour patterns of our own communities.

Inter-personal racism was, nevertheless, at its sharpest in encounters between those using community food provision. There was clear evidence of racism from older white British participants towards people born outside of the UK, notably asylum seekers, refugees, migrants, and international students. Participants used racial slurs and stereotypes when describing those they perceived to be asylum seekers, refugees or international students using community food provision: So just after Christmas time, we noticed that there was obviously the refugees going there and it’s got to the stage now where we’re really, really upset because the refugees go to that food bank and wipe it out. – Margaret

There was evidence of repeated and shocking racism towards asylum seekers using community food provision and we therefore discuss this at length elsewhere (Power and Baxter, Reference Power and Baxter2024). Although much of this racism was discursive, there were examples in which verbal was entwinned with structural racism. In York – albeit in neither Bradford nor London – some community food providers excluded refugees, asylum seekers and/or international students from accessing food aid; whilst this exclusion was framed as an inability to accommodate increases in demand from ‘new’ populations in the city, it was highly racialised and a clear example of racial discrimination. The ‘independence’ of these providers, untethered to a larger organisation or institution and largely free from regulation or oversight, allowed for such systemic discrimination.

South Asian participants in Bradford described experiences and perceptions of racial profiling and racism when accessing community food provision, which inhibited their return:

I’ve been to a food bank before and I feel like the Caucasian people judge you because they’re thinking why … like you’re the reason we’re in this situation and you’ve taken all our benefits, so just that fear of taking our food kind of thing. – Farah

I feel that’s why I stopped going … The majority of English people and older people when they looked at me, and there was gossiping as well and I won’t go for that again. – Noor

It was notable that inter-personal and structural racism in community food provision was place-based; at its sharpest in the predominantly white British city of York, and in Bradford, manifesting in both inter-personal interactions and the marked absence of culturally appropriate food, despite Bradford’s large South Asian population. Racial discrimination in community food provision was, however, much less evident in conversations with participants in London who, whilst objecting to the poor food quality, rarely described provision as culturally inappropriate and who, instead, often highlighted the ethnic diversity of staff and service users:

I think the community supermarket place as I call it, people there are, it’s a wonderful atmosphere, it’s a very strong community spirit, people get to know each other going there every week because you’re queueing up for one to two hours, everyone’s chatting and it’s 99% women, 99% women over 50. I’d say 80% to 90% Black and Brown women. – Paula

The study sites – Bradford, London and York – were chosen for their varied geography and demography, allowing for insight into the interaction of place and experiences of food charity. Whilst different from each other, these cities are nevertheless examples of ‘types’ of place – for instance, York is an example of towns and cathedral cities with a largely white British population, and Bradford of fast-growing, post-industrial, ethnically diverse cities. The findings here of racial discrimination within food aid are, therefore, arguably not unique to these specific cities but reflective of potentially wider trends across the UK.

Conclusions

The food aid sector in the UK has changed remarkably over the past decade, from a small but quickly growing body of Trussell Trust and independent food banks to an apparently diverse array of organisations and projects working to address either the immediate presentation of food insecurity (hunger) or a certain diagnosis of the underlying cause. Whilst there remains poor understanding of the scale and nature of the sector, there are increasing attempts to map and define it and moves at a policy level to understand how diverse types of provision address food insecurity and incentivise varying forms of provision (often financially) accordingly. What is absent here is much real recognition that the fault lines in lived experiences of the UK community food sector lie not along ‘type’ of provision but demography, specifically demographic inequalities of age, gender and parenthood and race and ethnicity. This absence encourages a fundamental questioning of the process of categorising the UK food aid sector: who is making these categorisations, are service users involved and to what end? The argument we present here is above all a call to centre lived experience and participatory methods more firmly in discussions and analyses of food aid.

This large qualitative longitudinal study identified pronounced inequalities in the lived experience of accessing community food provision. Older people, often protected from the experience and stigma of deep poverty by a low but reliable state pension, accessed various forms of food provision, sometimes, regularly, enjoying company as well as food, whilst the lived experiences of younger people were influenced by the constraints of employment and the acute stigma of working-age benefit receipt (Patrick, Reference Patrick2016). Reflecting a wealth of evidence on gender and poverty (Bennett, Reference Bennett2024), women’s experiences were closely shaped by parenthood, which not only constrained when food aid could be accessed, but magnified the stigma of doing so, with children, alongside peers, perceived to be judging their financial capabilities. In parallel with previous research on food charity, race and ethnicity (Power et al., Reference Power, Doherty, Small, Teasdale and Pickett2017), racial discrimination remains a feature of the food aid sector. Despite moves to diversify the nature of the food offered, there continues to be a notable absence of culturally appropriate food, and the evidence here indicates that experiences of racialisation and racial discrimination persist. There is a large scholarship demonstrating the rise in social resentment and community tension which can result from economic and cultural precarity (Pemberton et al., Reference Pemberton, Fahmy, Sutton and Bell2016; Tyler, Reference Tyler2013); that when economic resources are limited, people concerned for their own livelihood can construct, target and blame ‘others’ perceived to threaten their interests (Lister, Reference Lister2004). The evidence here suggests that that these processes are occurring within community food settings with older white service users racialising, and occasionally, colluding with organisational management to exclude refugees, asylum seekers and international students. The absence of regulation and oversight of the food aid sector allows for such clear examples of discrimination to take place, mirroring processes that have occurred more broadly in charitable models of social support (Smith-Carrier, Reference Smith-Carrier2020).

Despite high profile rhetoric against ‘dependency’ and organisational structures which discourage reliance on any particular service – a prime example being the Trussell’s limit of three food parcels within any 6-month period (Independent Food Aid Network, 2019) – community food provision is fast becoming a key source of food for many people in hardship; with the new Labour government failing to improve what is widely regarded as an inadequate welfare state (Child Poverty Action Group, 2024), this is likely to continue for the foreseeable future. Food aid organisations, themselves struggling to meet continually growing demand and staffed largely by volunteers, are ill-equipped to respond to prejudice and social vindictiveness from service users. At a conceptual level it is necessary to reconsider how stigma operates in relation to community food provision, moving away from a focus on the instrumental role of political rhetoric and organisational practices in upholding poverty stigma – both of which are critical to any understanding of community food aid and have been well documented (Garthwaite et al., Reference Garthwaite, Collins and Bambra2015; May et al., Reference May, Williams, Cloke and Cherry2019; Purdam et al., Reference Purdam, Garratt and Edmail2016; Williams and May, Reference Williams and May2022) – to sharpen attention to how inequalities and intersectionality shape lived experiences of food aid and the stigma that surrounds it. Specifically, how are stigmatising organisational practices experienced and navigated by different groups, and how does a wider political rhetoric and policy context which seeks to deter migrants and asylum seekers, as well as discouraging ‘dependency’ on working age social security, influence interactions between service users within community food organisations? It is important to note that, whilst a relatively large qualitative study, the fieldwork took place in three distinct locations and the extent of discriminatory rhetoric and behaviour was undoubtedly influenced by place, more pronounced in York, and to a lesser extent in Bradford, than in London. Nevertheless, we argue that the locations are representative of other ‘types’ of places across the UK; the findings are therefore likely to be replicated elsewhere, albeit further research is needed to ascertain the extent to which this is the case.

The findings here of discrimination and exclusion necessitate decisive action to establish organisational structures and policies which mitigate discriminatory behaviour and practices, requiring policy makers at the very least to consider an organisation’s approach towards equality and diversity in funding decisions. It is oft repeated that the UK’s food aid sector is a reflection of a deeply inadequate welfare state, and whilst this is certainly true, in the present moment, without many major progressive changes to social policy in sight, it is necessary to limit the stigma and discrimination of those who use food aid. A key step in doing so is to listen at length and over time to people with lived experience of poverty and food charity and to design the delivery of food aid accordingly.

Acknowledgements

Enormous thanks to all the participants who gave up their time to speak to us. We would also like to thank two reviewers for the time they took to comment on the article and provide very helpful insights and suggestions.

Competing interests

The authors declare none.