Introduction

One of the most important contemporary developments in public policy and administration has been the rise of innovations in participatory governance, which seek to complement representative institutions and enhance the effectiveness and legitimacy of policy making (Ansell & Gash Reference Ansell and Gash2008; Elstub & Escobar Reference Elstub and Escobar2019). By participatory governance, we refer to participatory forms of political decision making, involving organised and non‐organised citizens, to improve the quality of democracy (Geissel Reference Geissel2009). Participatory governance is often based on the principles of deliberative democracy, which emphasises free, open and public reasoning (Heinelt Reference Heinelt and Heinelt2018).

Two aspects should be considered when examining the rise of participatory governance in recent decades. First, as participatory processes began to enjoy policymakers’ support (at least in rhetoric) and spread globally, institutional elements that would have advanced social justice through power and wealth redistribution, such as incentives for popular mobilisation from marginalised sectors, were side‐lined. The emphasis shifted towards the role of citizen participation in strengthening the legitimation of representative institutions by helping to produce better‐informed and reasoned solutions to complex issues (Fung Reference Fung2015). Second, and on a more positive note, despite the ever‐present threat of co‐optation of citizen input by public agencies (Cooke Reference Cooke, Cooke and Kothari2004: 45–47), growing demands for participatory institutions with radically increased regulatory powers have been recently advanced by social movements (Tormey Reference Tormey2015, Baiocchi & Ganuza Reference Baiocchi and Ganuza2016, Sintomer Reference Sintomer2018, Font & Garcia‐Espin Reference Font, Garcia‐Espin, Flescher Forminaya and Feenstra2019). This might indicate that participatory governance has acquired central importance within projects for social transformation and democratic deepening (Feenstra et al. Reference Feenstra, Castello‐Ripolles, Tormey and Keane2017; Bua et al. Reference Bua, Davies, Blanco, Chorianopoulos, Cortina‐Oriol, Feandeiro, Gaynor, Griggs, Howarth, Salazar, Kerley, Liddle and Dunning2018; Della Porta & Felicetti Reference Della Porta and Felicetti2019; Roth et al. Reference Roth, Monterde and Calleja López2019; Blanco et al. Reference Blanco, Salazar and Bianchi2020; Davies, forthcoming).

This paper distinguishes between two different approaches to participatory governance that relate to both these developments. The first is what Mark Warren (Reference Warren, Griggs, Norval and Wagenaar2014) termed ‘governance‐driven democratization’ (GDD); the second one is an alternative form which we have labelled ‘democracy‐driven governance’ (DDG). Warren's work offers the best description of the most diffused form of participatory governance, particularly since the turn of the century. It relates to an elite‐led form of participation, where the aim is, on the one hand, to address the legitimacy crisis of institutions and experts and, on the other hand, to improve policymaking by involving new voices and interests and accessing new sources of information. The rationale is functionalist in nature, and the agenda is shaped by the commissioning bodies that ‘invite’ citizen participation (Cornwall & Coelho Reference Cornwall, Coelho, Cornwall and Coelho2007). In contrast, DDG is more critically oriented and bottom‐up. It emerges through popular mobilisation, attempts to bring social movements into the state and reclaiming and reinventing participatory structures to pursue transformative aspirations (Blanco et al. Reference Blanco, Salazar and Bianchi2020; Sintomer Reference Sintomer2018). Thus, participatory governance can respond to a functionalist need to develop better policies and legitimise traditional institutions (GDD), or a more transformative ambition to advance social justice and deepen democracy (DDG).

Based on this distinction, this paper examines how GDD and DDG emerge, develop and interact. We theorise that both forms exist in a dynamic relationship with each other, and our analysis of participatory governance in Barcelona looks at ‘tipping points’ that facilitated transition and interaction between GDD and DDG approaches in the city. The paper is structured into four sections. Firstly, we develop the conceptual distinction between GDD and DDG by locating them alongside other forms of participation. Secondly, we draw on case study literature to present a longitudinal analysis of participatory governance in Barcelona. Thirdly, we link our account of developments in Barcelona to the preceding theoretical discussion and present our analysis of transitions between GDD and DDG. Finally, the concluding section reflects on the transferability of our conceptualisation of DDG beyond the case of Barcelona and suggests avenues for future research.

GDD and DDG

Warren's (Reference Warren, Griggs, Norval and Wagenaar2014) article on ‘governance‐driven democratization’ provides a seminal description of a wave of participatory governance processes diffusing in conjunction with what David Howarth referred to as the ‘collaborative moment’ at the turn of the century (cited in Bua et al. Reference Bua, Davies, Blanco, Chorianopoulos, Cortina‐Oriol, Feandeiro, Gaynor, Griggs, Howarth, Salazar, Kerley, Liddle and Dunning2018). A strong assumption among proponents was that of a shift from ‘government’ to ‘governance’ (Rhodes Reference Rhodes1996). It was argued that ‘network governance’ underpinned a new form of public administration, which moved beyond both market‐driven new public management and traditional state‐centred bureaucracy to address the complex issues of the contemporary world (Osborne Reference Osborne2006). Scholars of democracy argued that the ‘pluralized ungovernability’ resulting from political and social complexity (Warren Reference Warren, Griggs, Norval and Wagenaar2014) highlighted the functional incapacities of traditional political institutions but also provided opportunities for the development of new kinds of democratic institutions (Skelcher & Torfing Reference Skelcher and Torfing2010):

[This development moves] policy making and administration to the front‐lines of the project of democratization […] the norms of democracy are being fostered, implemented and sometimes institutionalised through practical, front‐line practices of government, motivated by administrators who find that they need to forge partnerships with those their policies affect in order to plan, regulate, build, administer or govern. (Warren Reference Warren, Griggs, Norval and Wagenaar2014: 38)

Innovations in participatory governance try to respond to legitimacy deficits; are designed and implemented by political and administrative elites, with varying degrees of institutionalisation; prefer a search for consensus vis‐à‐vis acknowledging conflict; and focus on specific areas of policy or administration. Warren (Reference Warren, Griggs, Norval and Wagenaar2014) argues that the democratic potential of these processes lies in the opportunities they offer to engage those directly affected in policy making and to draw on civil society's resources for collective problem solving. Although scholars have identified a legitimacy gap from a normative point of view (Lafont Reference Lafont2015, Reference Lafont2017), participatory and deliberative processes such as randomly selected citizen assemblies, or mini‐publics, are enjoying increasing support from policymakers, the media and citizens alike. Recent experiences in Ireland, among others, have demonstrated that lay citizens can deliberate over highly complex issues, such as constitutional changes (Farrell et al. Reference Farrell, O'Malley and Suiter2013). Several cases demonstrate how these processes can be linked successfully to representative institutions in order to maximise citizen input in policy making. For instance, in the Oregon Citizen's Initiative Review (CIR) Process, a citizen panel deliberates on a ballot initiative or a referendum ahead of the vote (Gastil & Knobloch Reference Gastil and Knobloch2010; Gastil & Richards Reference Gastil and Richards2013).

The democratic potential of GDD therefore resides in its pragmatic, problem‐solving orientation as well as its proximity to the ‘nuts‐and‐bolts’ of public administration. In the past couple of decades, scholars of deliberative democracy have focused on procedural issues such as the deliberative quality of GDD processes (Steenbergen et al. Reference Steenbergen, Bächtiger, Spörndli and Steiner2003) but less so on outcomes in terms of social change. This raises an important challenge: whereas GDD opens up opportunities for practical influence over very specific issues and policies, it might also serve to de‐politicise collective action (Swyngedouw Reference Swyngedouw2005; Lee et al. Reference Lee, Walker and McQuarrie2015). The main concern of many critics is that GDD might close down spaces for transformative social change (Cooke & Kothari Reference Cooke, Kothari, Cooke and Kothari2001; Blaug Reference Blaug2002; Swyngedouw Reference Swyngedouw2005).

Warren (Reference Warren, Griggs, Norval and Wagenaar2014: 52–58) acknowledges that the elite‐driven nature of GDD might lead to citizen placation, assimilation and manipulation. His concerns are mainly at the micro‐level of procedural design and meso‐level interaction with representative institutions. A critical eye at the macro‐level would focus on the relationship of GDD with the surrounding political economy. In this context, we can begin to question whether contemporary politics is defined by the political complexities and the high capacity agents identified by reflexive modernisation theory underpinning network governance (Beck et al. Reference Beck, Giddens and Lash1994), or rather by the erosion of democratic choice as a result of the neoliberal political economy (Dryzek Reference Dryzek1996; Davies Reference Davies2011; Streeck Reference Streeck2014). A review of the impact of participatory governance over the past 30 years reveals a strong emphasis on functionalist aims (Fung Reference Fung2015), compared, for instance, to the democratic aspirations of participatory processes in the 1960s and 1970s (Pateman Reference Pateman1970; Boltanski & Chiapello Reference Boltanski and Chiapello2005). Thus, GDD has demonstrated that lay citizens have an epistemological advantage in tackling policy problems that affect their lives, but issues of social transformation and redistribution of power and wealth hardly feature in its rhetoric and practice.

We employ the label DDG to describe participatory governance that emerges from collective action. While GDD develops at arms’ length from social movements, which are often suspicious of institutionalised spaces and tend to operate autonomously from these, DDG represents an attempt by social movements to ‘move into the state’ and radicalise participatory governance as part of their strategy for change (Font & Garcia Espin Reference Font, Garcia‐Espin, Flescher Forminaya and Feenstra2019; Roth et al. Reference Roth, Monterde and Calleja López2019). The procedural forms taken by DDG often take inspiration from GDD initiatives (Baiocchi & Ganuza Reference Baiocchi and Ganuza2016; Sintomer Reference Sintomer2018), learning from the recent waves of participatory and deliberative processes. DDG, however, moves beyond GDD's discrete and ad hoc initiatives and towards more stable participatory spaces embedded within representative institutions. Most importantly, DDG opens up opportunities for bottom‐up agenda setting, by ways of hybrid processes where invented spaces of citizenship interact with traditional institutions to transform them rather than adding to their legitimacy.

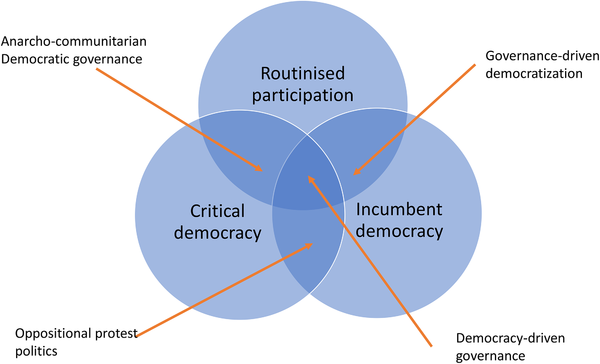

Our use of DDG and GDD builds on past distinctions between “bottom‐up” and “top‐down” participation – that is, ‘claimed’ or ‘invited spaces’ (Gaventa Reference Gaventa, Mohan and Hickey2004) versus ‘invented’ or ‘popular’ spaces (Cornwall Reference Cornwall, Hickey and Mohan2004; Cornwall & Coelho Reference Cornwall, Coelho, Cornwall and Coelho2007), or ‘insisted’ spaces (Carson Reference Garcia, Garcia and Degen2008) – and their interactions, as nicely captured in Gaventa's power cube (Reference Gaventa2005). We borrow Gaventa's (Reference Gaventa, Mohan and Hickey2004) description of spaces of participation as relational, emphasising power relations inherent to participation and the need to ask who sets the foundations of the space, as these will structure the participants’ interactions (see also, Fritz & Binder, Reference Fritz and Binder2018). The novelty of DDG vis‐à‐vis familiar concepts of ‘claimed’ or ‘popular’ spaces is twofold: first, DDG is always necessarily institutionally linked; second, DDG has a broader scope, which goes beyond ad hoc spaces to reimagine governance processes, by embedding citizen participation throughout existing institutions. By contrast, popular arenas or claimed spaces tend to be spaces of protest or participation that are autonomous from state institutions. These might be institutionalised in the form of associations or groups but can also be more transient expressions of public dissent (Cornwall Reference Cornwall, Hickey and Mohan2004: 2). The originality of DDG becomes clearer as we locate it within broader spaces of participation and observe how it interacts with these. To this end, we start with Blaug's (Reference Blaug2002: 107) distinction between ‘incumbent democracy’, which refers to those democratic processes primarily concerned with preserving and improving existing institutions, and ‘critical democracy’, which entails prefigurative ‘democratic moments’ that challenge existing institutions. Blaug would locate GDD within incumbent democracy, or what he calls ‘democratic engineering’. However, as with other past categorisations, his heuristic does not help us answer the question of what happens when attempts are made to institutionalise the forms of democratic organisation that arise from the ‘critical democracy’ of citizen mobilisations. The conceptualisation of DDG helps us address this question because it provides a conduit for the interaction of incumbent and critical spaces. Blaug (Reference Blaug2002: 104) describes democratic progress as ‘an ongoing struggle between incremental advances in the institutionalisation of accountable elite rule, and extraordinary movements of revolutionary mobilization, which raise popular consciousness and force elites to grant reforms’. DDG provides a middle ground between the ‘incumbent’ participation of GDD and ‘critical’ participation in democratic moments. By conceptualising DDG we accept that these spaces, rather than being dichotomous, often co‐exist and are continually interacting and mutually constitutive (Bussu Reference Bussu, Elstub and Escobar2019).

The diagram below (Figure 1) provides an illustration of the different forms of governance and politics that take place at the intersections of incumbent and critical democracy with ‘routinised’ forms of participation. Routinised participation is characterised by more or less institutionalised procedures for participation and decision making that may be open to change but have some degree of continuity. The diagram highlights some commonality between GDD and DDG. They both attempt to foster participatory governance or to include citizens in the work of public administration through ‘routinised participation' – that is to say, they both make use of defined procedures and rules for deliberation and participatory decision making. Both are also oriented towards reforming existing institutions. However, unlike GDD, which falls clearly under the definition of incumbent democracy, DDG entails a strong element of critical democracy, as it is driven and shaped by popular mobilisation. There are of course other forms of participation that have a bearing on processes of (de)democratisation. What, following Heller (Reference Heller2013: 25), we have called ‘anarcho‐communitarian’ democratic governance refers to the internal decision‐making rules adopted by democratically governed associations, which often reject becoming directly involved in public administration to avoid assimilation. In pursuit of public policy influence or public visibility, these associations might choose to exercise agency through participation in ‘oppositional protest politics’, and some of these actors may come to occupy institutional positions (Roth et al. Reference Roth, Monterde and Calleja López2019), or seek tighter coupling with state institutions (Della Porta & Felicetti Reference Della Porta and Felicetti2019).

Figure 1. Locating GDD and DDG spaces of democratization. [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

While clearly distinguishing between GDD and DDG forms of participation, we acknowledge the risk of portraying a static understanding of simplistic and fixed relationships between different spaces and citizen roles, which are often contested by participants themselves. For instance, Clarke et al. (Reference Clarke, Newman, Smith, Vidler and Westmarland2007) found that participants in GDD‐like forums on health and social care did not frame their relations to public services within the binary of citizen‐consumer, central to current public policy debates. Others have noted how the invited participants often deviate from what they are invited to do (Hajer & Kesselring Reference Hajer and Kesselring1999; Innes & Booher Reference Innes and Booher2004). Thus, it is important to reiterate that these spaces are not static but dynamic: newly claimed spaces can close through assimilation (Cornwall Reference Cornwall, Hickey and Mohan2004; Gaventa Reference Gaventa, Mohan and Hickey2004), and top‐down spaces can generate ‘new fields of power’ (Barnes et al. Reference Barnes, Newman and Sullivan2007) imbued with opportunities of democratisation.

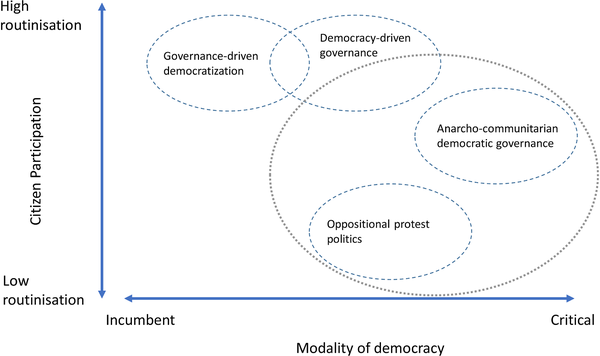

The case of Barcelona, presented in the next section, brings into focus the dynamic interactions across these spaces. Participatory budgeting (PB) in Porto Alegre, Brazil, is another seminal case that can help illuminate these relationships (Baiocchi Reference Baiocchi2005). PB can be understood as a case of DDG regime, where bottom‐up action from grassroots movements (popular spaces), supported by sympathising political forces (the Workers Party) that won the elections after the fall of the military dictatorship in the late 1980s, embedded forms of routinised participation (i.e., including non‐organised citizens in policymaking) within the yearly budget cycle. One might also argue that Porto Alegre's DDG regime has been stifled overtime by the council's technocrats and diminished political will to support bottom‐up engagement, raising the possibility that DDG can transform into GDD, as well as vice‐versa. Figure 2 visualises these dynamic relationships, whereby GDD and DDG, although shaped by different actors and informed by different agendas (top‐down vs. bottom up), use similar sites of highly routinised participation and, depending on different balances of power, can transform into one another. Popular spaces, firmly rooted in the realm of critical democracy, as illustrated by the largest circle, can develop into more institutionalised DDG participation, where citizens reclaim and transform existing sites of routinised participation.

Figure 2. GDD and DDG in dynamic relationship. [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Our analysis of Barcelona focuses on the ‘tipping point’ that marked the transition from a GDD regime referred to as the ‘Barcelona Model’ (Blakeley Reference Blakeley2005; Garcia Reference Garcia, Garcia and Degen2008) to a DDG regime under the Colau administration since 2015 (Blanco et al. Reference Blanco, Salazar and Bianchi2020). Whereas in recent years the concept of tipping points has gained traction in disciplines studying complex adaptive systems (e.g., development planning, climate change, ecological resilience), in political science the term was first used to address changes in neighbourhood dynamics of racial segregation (Grodzins Reference Grodzins1957). Sociologist Mark Granovetter (Reference Granovetter1978) preferred the term ‘threshold’ to capture social change and explain individuals’ decisions to participate in collective action, such as rioting. Baumgartner and Jones (Reference Baumgartner and Jones1993) described as ‘punctuated equilibrium’ moments of change interspersing long periods of policy stability (for a review of this literature see, Milkoreit et al. Reference Milkoreit, Hodbod, Baggio, Benessaiah, Calderón‐Contreras, Donges, Mathias, Rocha, Schoon and Werners2018). What these terms try to capture is a process of stability and slow, incremental change, speeding up to more dramatic cascading effects, which we set out to describe in our analysis of GDD–DDG transition in Barcelona.

Whereas the concept of DDG can be relevant to social movement‐led participatory governance beyond material concerns (Della Porta & Felicetti Reference Della Porta and Felicetti2019), the global financial crash played a crucial role in the emergence of DDG in Spain, emphasising the importance of explanatory frameworks based on critical political economy (Bebbington Reference Bebbington, Cooke and Kothari2004). Here we focus on economic shocks as one example of a tipping point leading to the emergence of DDG. The literature tells us that the opportunity cost of challenging power is lower following transitory negative economic shocks, which can trigger tipping points leading to greater democratisation (Acemoglu & Robinson Reference Acemoglu and Robinson2001). Our analysis considers how variables often examined by scholars of urban politics and local governance, such as associational density (Putnam Reference Putnam1993; Fung Reference Fung2003), autonomy from higher tiers of government (Le Galès Reference Le Galès2002) and local economic and political context (Bua et al. Reference Bua, Davies, Blanco, Chorianopoulos, Cortina‐Oriol, Feandeiro, Gaynor, Griggs, Howarth, Salazar, Kerley, Liddle and Dunning2018; Davies forthcoming), interact with economic shocks to produce regime change. It should be emphasised, however, that the concept of DDG can travel to other socio‐political contexts. Climate disasters, for instance, could trigger cascading effects leading to DDG elsewhere.

Environmental social movements such as Extinction RebellionFootnote 1 demanding a randomly selected citizen assembly on climate policies in the United Kingdom might perhaps suggest the start of a new DDG project. Social movements have been pushing for DDG‐like approaches to participatory governance in Northern European countries (Della Porta & Felicetti Reference Della Porta and Felicetti2019) and, more recently, in France.Footnote 2 Spain, however, is the site of one the most ambitious DDG experiments, and it has witnessed a high degree of institutionalisation of social movement‐led participatory governance following the electoral victories of progressive coalitions in many major cities in the 2015 municipal elections (Font & Garcia Espin Reference Font, Garcia‐Espin, Flescher Forminaya and Feenstra2019; Blanco et al. Reference Blanco, Salazar and Bianchi2020). As the purpose of the paper is to conceptualise social movement‐led participatory governance, and provide scholars and activists with a new vocabulary to describe and understand these developments, the case of Barcelona serves to demonstrate how DDG differs from other spaces of participation, whether invited or invented, while emphasising dynamic relationships with these.

Between GDD and DDG: The case of Barcelona

Barcelona is the capital city of the autonomous region of Catalonia, the second largest city of Spain and an important economic dynamo with high concentrations of wealth and sharp socio‐economic inequalities. Following the creation of Spain's contemporary local democratic institutions in the late 1970s, the city underwent an ambitious urban restructuring programme that sought to decentralise local state institutions and open them up to civil society, with the aim to reduce inequalities as well as improve and extend welfare provision and public services (Blakeley Reference Blakeley2005; Garcia Reference Garcia, Garcia and Degen2008). This governance model relied on mechanisms of participation from a range of local actors, generally organised social and private stakeholders, but under highly hierarchical public sector leadership (Capel 2007, cited in Eizaguirre et al. Reference Eizaguirre, Pradel‐Miquel and García2017). By 1986 this approach had translated into regulations establishing a series of participatory initiatives (i.e., public hearings; petitions; right to information) and sectoral and territorially differentiated advisory councils, which played an important role, particularly in social policy (Blakeley Reference Blakeley2005: 151; Blanco Reference Blanco2009: 360).

With post‐Fordist de‐industrialisation, the focus shifted towards local competitive advantage (Crouch et al. Reference Crouch, Le Gales, Triglia and Voelzkow2001). As urban elites were increasingly forced to respond to the pressures of international capital and competition for job creation, issues of housing, social exclusion and social conflicts started to fade away from the political agenda, while lower taxation became the indicator of good management (Le Galès Reference Le Galès2002). The rhetoric of image and identity were given political priority to attract investments, with more emphasis on public–private partnerships. It was within this context that Barcelona successfully applied to host the 1992 Olympic Games, an event which signalled a different growth model – based on tourism, culture and private real estate development (Delgado Reference Delgado2007; Garcia Reference Garcia, Garcia and Degen2008). What is referred to as the ‘Barcelona Model’ (Blakeley Reference Blakeley2005), which we identify as a case of GDD, started to crystallise at this time (Blanco Reference Blanco2009: 359). Overseen by Spanish socialist party mayor Pascual Maragall (1982–1997) and supported by his successor Joan Clos (1997–2005), this approach included the use of great events as catalysts for regeneration, collaborative governance based on public–private partnerships, and citizen engagement in local planning (Blanco Reference Blanco2009). The Barcelona Model maintained a strong focus on participatory public administration, but the agenda was increasingly constrained by the need for foreign investment and the promotion of large cultural and infrastructural projects as a way to increase the city's competitive advantage (Rius & Subirats Reference Rius and Subirats2005; Delgado Reference Delgado2007). In 2004, the staging of the ‘Universal Cultures Forum’ served as an international exposition for the city's burgeoning tourist industry. By this point, participatory governance had mostly been reduced to non‐binding consultations, heavily orchestrated by the council, with participation of professionals and association representatives within advisory councils (Blakeley Reference Blakeley2005; Delgado Reference Delgado2007; Garcia Reference Garcia, Garcia and Degen2008). Eventually it came to be perceived as hollow, generating more fatigue than empowerment (Blanco et al. Reference Blanco, Salazar and Bianchi2020), especially as the growth model it was attached to came under sharp criticism for deepening inequalities and social exclusion through gentrification, touristification and real estate inflation (Rius & Subirats Reference Rius and Subirats2005; Delgado Reference Delgado2007; Marti‐Costa & Tomas Reference Marti‐Costa and Tomas2017).

During the 1980s and 1990s, social opposition to the Barcelona Model was contained by the incorporation of actors from neighbourhood assemblies (Blakeley Reference Blakeley2005; Blanco Reference Blanco2009). This formed part of a process of professionalisation of participatory venues and reduced the independence and organisational capacity of local civil society, much of which had come to depend on municipal funding (Blakeley Reference Blakeley2005). At the turn of the century, however, counter‐hegemonic spaces began to flourish where social movements collaborated with critical public servants to develop alternative regeneration models (Blanco Reference Blanco2009), highlighting the important role that public administrators also play within these networks. Autonomous organisations had already started to form in response to the economic crisis and austerity of the mid‐1990s. During this period, local social movements developed considerable mobilisation capacity, as demonstrated by widespread protests staged against the aforementioned Universal Cultures Forum. In what is clearly characteristic of a kind of coexistence and interaction between GDD and DDG, Blanco (Reference Blanco2009: 368) foresaw that this ‘alternative network’ could prefigure a more radical future approach to urban governance.

A window of opportunity for these movements to attain greater institutional influence began to open with the social fallout from the 2008 financial crash. Across Europe, political elites’ response to the crisis was to shift the focus from the financial sector's moral hazard to the alleged unsustainability of growing public debt (Blyth Reference Blyth2013). This translated into a strong rationale for the implementation of austerity measures and the roll back of public services (Peck Reference Peck2012; Blanco et al. Reference Blanco, Salazar and Bianchi2020). By offloading the burden of the crisis onto the general public, politicians exacerbated perceptions that they had sided with global economic elites, unleashing an expansion of progressive protests and social movements (Albo & Finelly Reference Albo and Finelly2014), as well as nativist and populist politics both on the left and the right of the political spectrum (Hopkin & Blyth Reference Hopkin and Blyth2019). In Barcelona, the 2011 municipal elections marked the victory, for the first time since the end of Franco's fascist regime, of a conservative coalition; Xavier Trias, a right‐wing Catalan nationalist politician, was elected mayor on a pro‐austerity platform. Bottom‐up initiatives began to emerge to fill gaps in market and state provision left by austerity (Eizaguirre & Pares Reference Eizaguirre and Parés2019), which the Trias administration was tolerant of as they were coherent with neoliberal rollout by helping to meet social needs without state involvement (Belando Reference Belando2016). However, such ‘bottom‐linked’ (Pares et al. Reference Parés, Subirats and Ospina2017) forms of social innovation went beyond service delivery and were politicised in ways connected to claims for the right to the city.

Two main social movements drove the radical political reaction to austerity. The first one was the platform of mortgage victims (PAH), which had emerged in 2009 in Barcelona, spreading gradually to other cities. It had wide impact, by helping reframe housing as a collective issue rather than an individual debt problem, and by supporting several innovative actions, such as collective negotiation of housing debts with financial institutions (Eizaguirre et al. Reference Eizaguirre, Pradel‐Miquel and García2017: 4). The second movement was the Indignados, which swept Spain in 2011 and whose demands for ‘real democracy now!’ became a catalyst for a variety of initiatives promoting social welfare and direct participation. By 2014, the Indignados movement's presence had fizzled out, but the political and citizenship agenda it had articulated was incorporated by local coalitions and in national politics with the formation of the new populist left party ‘Podemos’ (Iglesias Reference Iglesias2015). In the 2016 national elections, Podemos gained 21.2 per cent of votes share. In local politics, it supported radical left citizen platforms, coalitions and movement‐parties, which successfully contested the 2015 local elections in several cities, including the three largest in Spain, Madrid, Barcelona and Valencia (Font & Garcia‐Espin Reference Font, Garcia‐Espin, Flescher Forminaya and Feenstra2019; Roth et al. Reference Roth, Monterde and Calleja López2019). In Barcelona, the ‘movement‐party’ Barcelona en Comú (BeC), led by PAH's spokesperson Ada Colau, won the elections by a small majority (Blanco et al. Reference Blanco, Salazar and Bianchi2020).Footnote 3

Movements such as PAH and the Indignados were instrumental for the BeC platform, providing important channels for non‐state actors to define priorities in defence of social rights and advocating more democratic control over various aspects of municipal politics and economy (Eizaguirre et al. Reference Eizaguirre, Pradel‐Miquel and García2017). Not only was the influence of social movements evident in the content of policies, but also in BeC's modes of governance, as it adopted horizontal decision‐making structures (Font & Garcia‐Espin Reference Font, Garcia‐Espin, Flescher Forminaya and Feenstra2019). Two types of commissions offered space for citizens to discuss the needs of the city and the development of a political programme. Thematic commissions dealing with a wide range of issues such as gender, urbanism, participation and democracy, environment or health, followed the model of debates that had characterised the Indignados protests and aimed at stimulating political discussion and developing specific measures for the election campaign (Eizaguirre et al. Reference Eizaguirre, Pradel‐Miquel and García2017). Neighbourhood commissions were more traditional bodies for residents’ participation, which ensured the territorial rooting of the platform (ibid.). One of the features distinguishing this mode of governance from social movements’ involvement in the 1980s is that, although BeC's platform was open and indeed shaped by social movements’ demands, it sought to institutionalise participation by individual citizens rather than associational representatives. Therefore, citizens, even when members of social movements, political parties, trade unions or other organisations, participated on an individual basis together with non‐affiliated citizens (Baiocchi & Ganuza Reference Baiocchi and Ganuza2016; Eizaguirre et al. Reference Eizaguirre, Pradel‐Miquel and García2017).

Once in government, BeC's policy agenda continued to be informed by citizens and social movements through interlinked online and offline channels of participatory governance embedded in the policy process. The new administration embarked on an ambitious reform programme that ranged from public service re‐municipalisation to the promotion of co‐operative enterprise and the solidarity economy (Martinez Reference Martinez2019; Roth et al. Reference Roth, Monterde and Calleja López2019; Blanco et al. Reference Blanco, Salazar and Bianchi2020). Inspired by the radical ‘techno‐politics’ and ‘hacker ethics’ of many anti‐austerity activists (Barandiaran Reference Barandiaran, Roth, Monterde and Calleja López2019; Calzada & Almirall Reference Calzada and Almirall2019), BeC is also challenging the dominance of large tech companies and reclaiming technological infrastructures and services for socio‐communitarian purposes (Barandiaran Reference Barandiaran, Roth, Monterde and Calleja López2019: 203; Calleja & Toret Reference Calleja, Toret, Roth, Monterde and Calleja López2019). This is what hacker activists call ‘technological sovereignty’ (Hache 2014, cited in Barandiaran Reference Barandiaran, Roth, Monterde and Calleja López2019) against neoliberal ‘smart‐city’ models (Calzada Reference Calzada, Giorgino and Walsh2018). For example, with Amsterdam, Barcelona leads the European Union‐funded project DECODE (Decentralised Citizen‐owned Data Ecosystems), which aims to develop and test open source, distributed and privacy‐aware technology architecture to decentralise data governance and identity management. Part of the new city‐wide participatory regulations, the open source platform Decidim (Catalan for ‘We Decide’) aims to facilitate inclusive participatory democracy, whereby citizens can suggest ideas, debate them and vote. It connects online and face to face spaces to organise various participatory processes ranging from petitioning and citizen initiatives to co‐production, participatory budgeting and municipal planning (Calleja & Toret Reference Calleja, Toret, Roth, Monterde and Calleja López2019).

Participation in Barcelona's 2016–2019 municipal plan (accounting for 40 per cent of municipal expenditure) was co‐ordinated through a staged participatory process. Over 70 per cent of the proposals were developed by over 40,000 citizens on Decidim, and many more were engaged in offline collective assemblies and consultations. These proposals were filtered by council experts (in a process that was open to appeals) and put to a vote in the council.Footnote 4 According to the platform's website, by December 2018, Decidim had initiated 35 participatory initiatives, co‐ordinated 1,141 public meetings and collected 13,927 proposals, which have become public policies that can be monitored by citizens through the platform in 9,196 different cases.Footnote 5 The platform has also spread internationally, including to other cities and regions like Helsinki, Mexico City and Quebec, as well as organisations such as the National Commission for Public Debate in France.Footnote 6 Barcelona also leads a network of rebel cities, ‘Fearless Cities’, which promotes the adoption of similar redistributive and participatory practices (Russell Reference Russel2019).

Between GDD and DDG: A dynamic relationship

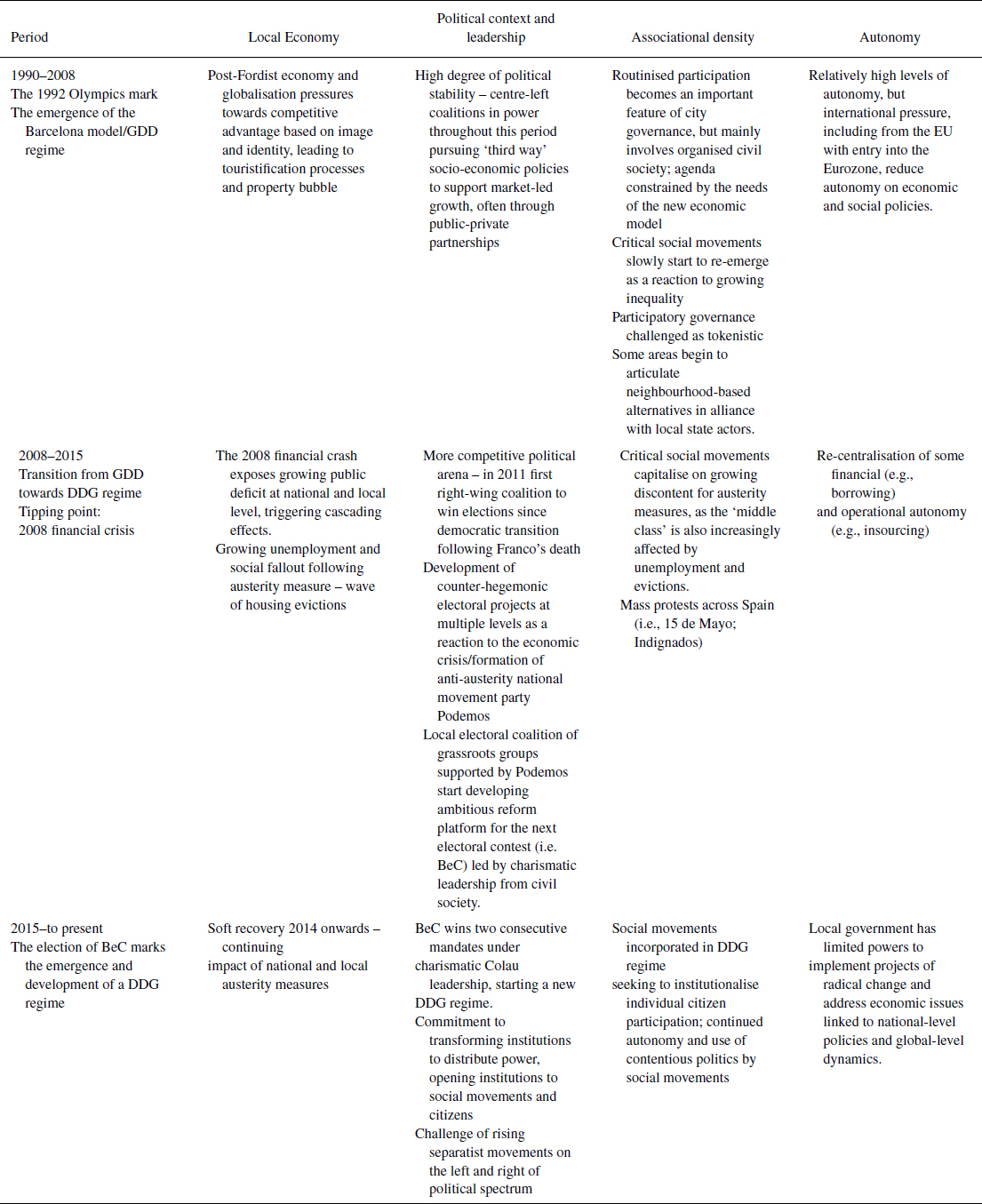

From the narrative of Barcelona's recent history in the previous section, we can identify the tipping point and cascading effects that led to the transition from GDD to a DDG regime. The 2008 financial crash produced an economic shock, a tipping point which triggered a series of cascading effects. First, there was a change in government, with the first right‐wing administration in Barcelona since the Spanish transition from fascism to democracy. The new political environment marked an abrupt end to the centre‐left top‐down vision of transformation, which had underpinned the GDD regime. Second, the widespread protests against draconian austerity measures imposed at national and local level led to the formation and ultimately the electoral victory of BeC in the 2015 local elections. Tarrow's (Reference Tarrow1994) seminal work calls the degree of openness or closure of political access to citizen action ‘political opportunity structure’ (POS). He identifies ‘the opening up of access to power, shifting alignments, the availability of influential allies, and cleavages within and among elites’ as salient changes in the POS (Tarrow Reference Tarrow1994: 85–86). These changes can affect the capacity of citizens to mobilise and create new sites for social action. In Barcelona, regime change from GDD to DDG emerged from the interactions of an external shock (the 2008 financial crash) with structural, institutional and agential variables such as local economic conditions and degree of local autonomy, political context and leadership, and associational density, producing dynamic relationships between the different participation spaces conceptualised in Figures 1 and 2. Table 1 summarises the main factors behind this transition.

Table 1. Transition from GDD to DDG in the case of Barcelona

The table identifies four main variables that interact to produce regime change. We begin our analysis by looking at associational density and political context, and we will then move onto the local economy and degree of autonomy of the local state.

Whereas grassroots neighbourhood movements had long played a crucial role in Spain in strengthening democratic culture (Acebal Reference Acebal2015), the post‐2008 protest movements went beyond traditional ways of occupying institutions such as building ties with sympathetic policymakers and/or having their own delegates win elections to implement progressive policies. Instead, these new movements were able to capitalise on prior experience and knowledge of GDD processes with the aim of transforming them from consultative into empowered spaces, showing a more explicit commitment to distributing power (Russell Reference Russel2019). They developed various participatory structures for their own internal governance (including the use of random selection to choose candidates), to build their manifestos and, once elected, to govern (Font & Garcia‐Espin Reference Font, Garcia‐Espin, Flescher Forminaya and Feenstra2019; Blanco et al. Reference Blanco, Salazar and Bianchi2020). A DDG regime therefore emerged as this social movement‐led action moved beyond the realm of ‘critical democracy’, carried out in spaces that are separate and autonomous from the state (Blaug Reference Blaug2002), and carved out institutional power to implement more horizontal forms of governance, by reclaiming and expanding the reach and scope of the participatory structures of the previous GDD regime. Traditionally, one of the dilemmas faced by social movement‐led governments is whether to use the levers available to them to implement social programmes from the top down, or invest in longer term work by opening up state institutions to citizen participation to ensure that social reforms respond more directly to bottom‐up demands, rather than technical advice (Roth Reference Roth, Roth, Monterde and Calleja López2019: 78–79). This is an important point, because we can hypothesise that the political success and endurance of a DDG reform agenda depends on both delivering improvements in living standards and generating a robust pro‐participation political culture, which could increase its resilience and help build a consensus in favour of participatory democracy (Lima Reference Lima2019; Martinez Reference Martinez2019; Blanco et al. Reference Blanco, Salazar and Bianchi2020).

The tight coupling between social movements and state institutions, that defines DDG, carries certain advantages and dangers from the perspective of social movements. Della Porta and Felicetti's (Reference Della Porta and Felicetti2019) analysis of the Icelandic Constitutional reform, a case where a bottom‐up participatory process was coupled with the state, shows that while coupling provides participatory experiments with substantial resources, it can also lead to the imposition of administrative logics over social movements. Experiments with DDG might also continue to rely on the emergence of charismatic leaders like Ada Colau, who, by moving from civil society into state institutions, might well expose these political projects to dangers of co‐optation through personalisation. Paraphrasing Della Porta and Felicetti (Reference Della Porta and Felicetti2019: 12), collaboration with institutions might be a necessary condition for policy impact, but it is not a sufficient one, because the state imposes administrative dynamics that can halt change. Martinez (Reference Martinez2019) points out that, whereas municipalist platforms in Spain relied on activist social networks to develop, this does not ensure responsiveness to movements when in power. In this respect, the autonomy of allied social movements and the opening of institutions to enable grassroots actors to act as a counterbalance is an important feature of a DDG regime. Failure to foster radical change through participatory processes may however generate a disaffection spiral that risks hampering the political capacity of social movements allied to the DDG administration (Fernández et al. Reference Fernández‐Martínez, García‐Espín and Jiménez‐Sánchez2019).

The machinery of city government is not a neutral tool and can exercise strong influence in policy implementation (John Reference John2011). In the case of BeC, ostracism from many public servants was exacerbated by the administrative inexperience of social movement activists‐turned elected politicians (Roth et al. Reference Roth, Monterde and Calleja López2019; Blanco et al. Reference Blanco, Salazar and Bianchi2020: 13–15). BeC also faced fierce opposition from a ‘pro‐status quo coalition’ (Blanco et al. Reference Blanco, Salazar and Bianchi2020: 14) with influence over local, regional and national media, which it leveraged to distort policies and generate scandals. As an example, the administration's pro‐liveability urban planning policies that aimed to regulate tourism were widely portrayed in the media as irrational and economically damaging ‘tourism‐phobia’.Footnote 7 Moreover, nationalism of both left and right varieties is an important feature of Catalan politics. BeC has had to face up to strategic tensions and compete for support with the Catalan separatist left, which might share similar socio‐economic goals but prioritises independence as part of its strategy to achieve them. Such divisions have weakened BeC, especially following the polarisation generated by the 2017 Catalan independence referendum, which shifted the focus away from social concerns and towards issues of national identity. This resulted in a weakening of BeC's electoral position, which gained only 11 out of 41 seats in the 2015 local council elections and 10 in 2019 and has had to govern through political agreements with the Socialist Party. Indeed, the poor electoral performance in 2019 almost led to a change in government, exposing the vulnerability of radical democratic projects to political cycles. These challenges might drive processes of de‐radicalisation, which can already be traced in BeC's more moderate positions since being in government (Martinez Reference Martinez2019). Whereas recent empirical research highlights that critical social movements continue to see BeC as an ally while maintaining their operational autonomy and contentious capacity (Martinez Reference Martinez2019), the stability of these alliances is by no means guaranteed. In a context of political turmoil, the ability of social movements to keep momentum and forge alliances with a different, perhaps less sympathetic, administration is an important test of both political culture change and popular consensus over more radical participatory modes of governance.

The economic context and the degree of local autonomy play a crucial role in sustaining or hindering any project of radical transformation. The case of Barcelona demonstrates the inevitable challenges faced by a DDG regime. The combination of continuing global pressures on the ‘competitive city’ (Harvey Reference Harvey1989), market‐led development, austerity politics and the crisis tendencies contained therein (Peck Reference Peck2002, Reference Peck2012; Davies forthcoming) reduces opportunities for radical change. For instance, the Colau administration was able to introduce some important measures in relation to housing but has had limited power over regulating rents or eviction policy (Blanco et al. Reference Blanco, Salazar and Bianchi2020: 14). As expectations to address the housing crisis and stop foreclosures have not entirely been met, this exposes the limits of city council power. Through the law for the rationalisation and sustainability of local administration, local authorities are now mandated to use any financial surplus for debt repayment, while austerity was seized by the national government as an opportunity to recentralise some powers (Blanco et al. Reference Blanco, Salazar and Bianchi2020). Furthermore, national‐level legislation prevents councils from re‐employing private sector workers in re‐municipalisation projects, creating very effective disincentives to the latter (Miro 2019, cited in Davies, forthcoming). We might therefore argue that the project for a deeper democracy must align with one for a decentralised democracy and strengthened local government (Bussu Reference Bussu2015; Bua & Escobar Reference Bua and Escobar2018).

The story of Barcelona shows that democratisation and de‐democratisation are in dynamic interaction; ‘claimed spaces’ that were once breeding grounds for alternative politics can become ‘closed’ spaces where participation becomes an assimilative process that produces non‐decisions (Cornwall Reference Cornwall, Hickey and Mohan2004; Gaventa Reference Gaventa, Mohan and Hickey2004). The interaction between GDD and DDG is evident in alliances between social movements and those public servants more open to change, or participation experts and practitioners collaborating with activist networks to build new participatory structures, like Decidim. Whereas the emergence of both GDD and DDG tends to be context‐sensitive, the wave of GDD initiatives since the turn of the century has primarily been diffused through institutional contexts, and partly as a result of blueprints sponsored by national governments and international organisations under the jargon of ‘open government’ and ‘good governance’. In contrast, DDG seems more likely to emerge from local experiments that develop through a continuous process of learning by ‐doing within and outside institutions. More research is warranted into the role that social movements and activist networks can play in diffusing DDG as well as building international constituencies to strengthen the legitimacy of their project and jump scale (Smith Reference Smith, Eskelinen and Snickars1995), in order to exert pressure on higher tiers of authority to call for changes in regulations outside the scope of municipal action. With regards to Barcelona, an example of this is the hosting of the ‘fearless cities’ conference, which brought together a cross‐country network of radical municipalist governments and activists to co‐ordinate demands and political activism from local through to global scales (Russel Reference Russel2019).

Conclusion

Both GDD and DDG are forms of what we have termed here ‘routinised participation’, as they attempt to institutionalise direct citizen engagement. GDD sits at the intersection between routinised participation and incumbent democracy (Blaug Reference Blaug2002), as an example of democratic engineering, where lay citizens are brought in to support politics and public agencies, with the aim to increase legitimacy and produce better policies. DDG falls at the intersection between routinised participation and critical democracy (Blaug Reference Blaug2002), as social movements and local civil society enter local state institutions and reshape them to respond to bottom‐up demands for reforms and rights. The participatory sites through which GDD and DDG play out are similar, as both capitalise on decades of academic knowledge and practice of participatory governance, facilitated deliberation and, increasingly, sortition, using a combination of online and offline spaces. The normative orientation is different, however, as GDD's primary focus is on efficient decision making and service‐users’ epistemic advantages, while DDG places emphasis on citizen rights and social justice.

The case of Barcelona illuminates how DDG emerges and develops, highlighting its dynamic relationship with GDD‐like participation. Counter‐hegemonic popular spaces developed in parallel to the formal participatory governance infrastructure of the GDD regime and were sometimes institutionalised within its interstices (Blanco Reference Blanco2009). Therefore, the spaces we have labelled ‘anarcho‐communitarian’ in our illustration also need to develop during, and feed into, DDG. Whereas personalisation of the political project might expose social movement‐led action to co‐optation, the originality of DDG lies in its attempt to open institutions to social movements and citizens more broadly, by embedding participatory governance in the local policy process and safeguarding critical spaces for social movements to act as a counterbalance to the administration. This might ensure that social movements can retain some degree of independence and capacity for contention.

Spanish civil society's entry into local institutions and its efforts to re‐scale the organisation of public power through participatory institutional designs that attempt to ward off local elite capture have inspired social movements worldwide. Unsurprisingly, the BeC administration has been opposed by a powerful ‘pro‐status quo coalition’ and challenged by age‐old power equations pitting bureaucrats against civil society (Blanco et al. Reference Blanco, Salazar and Bianchi2020). The potential of these initiatives to take hold and develop will likely depend on whether a popular consensus for deepening the scope of democracy can be forged. As argued by Pateman (Reference Pateman2012), the question is no longer whether participatory democracy is feasible. This argument has been won after 40 years of empirical evidence from experiments with participatory democracy, not only within sites of government but, equally importantly, within the workplace (Pateman Reference Pateman1970; Wolff Reference Wolff2012). Opportunities for substantive citizen participation are today further strengthened by technological developments that can support greater inclusiveness and scaling‐up. Decidim is a powerful example of how technology can help include citizens in the policy process (Deseriis Reference Deseriis2019), while also reclaiming data ownership as the new common. It will be interesting to understand the cultural impact of these movement‐parties in altering patterns of political disengagement and distrust towards state institutions and in building popular consensus for more direct citizen participation.

This paper used the concept of tipping point to examine the dynamic relationship between GDD and DDG and understand the transition from one into the other in Barcelona. It should be emphasised that the case of Barcelona has a particular context, as a major city in a Southern European country, member of the Eurozone, which faced relatively high material fallout from the Great Recession and imposition of austerity measures. It therefore lends itself to analysis from a political economy perspective. The 2008 financial crash was therefore identified as the tipping‐point triggering cascading effects that led to regime change from GDD to DDG. However, this does not necessarily prevent the concept of DDG from travelling to other contexts where links between social mobilisation and the material consequences of capitalist crises are not as clear (Della Porta & Felicetti Reference Della Porta and Felicetti2019). We encourage future research into DDG to avoid reductionism and use analytical frameworks sensitive to non‐material factors that could also set in motion DDG‐like processes. A climate disaster or a pandemic, for example, could constitute tipping points.

Further research might seek to draw on sociological literature, for example institutional isomorphism (Di Maggio & Powell Reference Di Maggio and Powell1983) or Bourdieusian field theory (Hilgers & Marguez Reference Hilgers, Marguez, Hilgers and Marguez2015), to theorise and investigate the conditions under and processes through which convergence and/or divergence (Beckert Reference Beckert2010) between GDD and DDG occurs. This might deepen our understanding of how different forms of participatory governance develop and transform. Finally, by taking a public policy lens, new research might examine and qualify different GDD/DDG approaches to participatory governance based on models of policy analysis distinguishing between input, throughput and output (Easton Reference Easton1953; Schmidt Reference Schmidt2013) to specify what kind of engagement and participation is wanted and needed in different contexts (Bua Reference Bua, Elstub and Escobar2019). In this respect, examining the resilience and viability of DDG under emergency situations, such as the current Covid‐19 pandemic, might shed some light on the validity of arguments in favour of strong hierarchies to facilitate swift decisions (no matter how poor) in crisis situations. If inclusivity and deliberation lead to greater reflexivity and better decisions (Dryzek Reference Dryzek2000), this might also apply during emergencies when adversarial frameworks can be highly problematic and strengthening democratic institutions is all the more important.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Jonathan Davies, Andrew Thompson and Yunailis Salazar and the two anonymous reviewers for their constructive and encouraging comments on earlier drafts of this article, and the EJPR editorial team for their guidance and support throughout the process. The paper also benefited from comments from participants at the ECPR and Italian Political Science Association general conferences in 2019, as well as from the ECPR Joint Session workshop on Innovation and Power.