Introduction

Citizen interest groups face significant obstacles in influencing policy, especially when they oppose powerful stakeholders such as employer organizations (Rasmussen and Carroll Reference Rasmussen and Carroll2014). These advocacy groups typically operate with limited economic resources, face organizational hurdles due to diffuse interests, and have restricted access to key policymaking venues (Dür and de Bièvre Reference Dür and de Bièvre2007). Recent research suggests that citizen groups can overcome these barriers through outsider mobilization, such as public campaigns that heighten issue salience and sway public opinion (Dür and Mateo Reference Dür and Mateo2014). The literature also expects interest groups to target ideologically aligned or governing parties, as they are more likely to endorse their initiatives (Beyers et al. Reference Beyers, Bruycker and Baller2015; Rasmussen and Lindeboom, Reference Rasmussen and Lindeboom2013).

However, the case of paternity leave reform in Spain challenges these assumptions. The Platform for Equal and Non-transferable Birth and Adoption Leave (PPiiNA), a small feminist advocacy group formed by activists and academics, convinced the Spanish government to establish an individual and non-transferable leave entitlement, equal for all parents, in 2019. By unveiling how their success was mainly based on insider alliances with female politicians from both the right and the left, this article contributes to previous studies on interest group influence and gender equality politics.

Several aspects make this a least-likely case for the literature on interest groups. First, PPiiNA’s proposal succeeded despite opposition from employer organizations (Rasmussen and Carroll Reference Rasmussen and Carroll2014). Second, the reform offered uncertain electoral benefits for politicians, as it lacked clear public opinion support (Cañero and Marinova Reference Cañero and Marinova2025). Third, it also defied the policy legacies of a country historically lacking policies to support working parents (Guillén et al. Reference Guillén, Jessoula, Matsaganis, Branco, Pavolini, Burroni, Pavolini and Regini2022), making Spain the only state to mandate fully earmarked, non-transferable leave, with no additional transferable paid options. As the policy aims to redistribute care and employment opportunities across genders, this suggests looking beyond the interest group literature toward studies on gender equality policy determinants.

Why was PPiiNA successful? Or, more specifically, how did political actors operate and interact in the process behind the 2019 Spanish paternity leave reform? The study employs deductive process tracing to test established expectations on (1) who the key actors were, (2) how they exerted their influence, (3) how this varied along the policy process, and (4) the type of politicians that PPiiNA successfully engaged with. The analysis draws on a systematic review of parliamentary debates about paternity leave and 14 in-depth interviews with key participants in the process.

The findings can be summarized in four distinct stages where actors vary in their activity and significance. First, a party agenda-setting phase (2002–2007), when parties embraced the concept of non-transferable paternity leave. Second, a citizen agenda-setting phase (2007–2015), during which PPiiNA garnered support from female politicians involved in gender equality issues across the whole political spectrum to advocate for equal and non-transferable leave for both parents. Third, a phase of parliamentary access for PPiiNA (2015–2018), when the group persuaded a new left-wing party to introduce its law proposal in parliament. Fourth, an executive formulation phase (2018–2019), when the mainstream left assumed government and engaged in negotiations for the final reform design with other parties and employer organizations, thus reducing the influence of PPiiNA.

These results offer several contributions. Research on gender and politics shows the relevance of women’s descriptive representation for gender equality reforms (Htun and Weldon, Reference Htun and Weldon2010; Annesley et al. Reference Annesley, Engeli and Gains2015). This article demonstrates that female parliamentarians matter not only through their own initiatives but also by opening insider channels for feminist advocacy groups to bring their proposals into parliament (Coil et al. Reference Coil, Bruckner, Williamson, O’Connor and Gill2024). This also resonates with interest group research by proposing conditions under which citizen groups can employ insider tactics (Dür and Mateo Reference Dür and Mateo2014). Namely, descriptive representation may grant minority advocacy groups institutional access otherwise reserved for professional lobbies, a pattern that could also work along ethnic lines (Minta Reference Minta2020). However, even when citizens may gain access to the agenda, partisan divisions and elite-driven policy formulation can limit the translation of these alliances into concrete policy outputs (Holli Reference Holli2012). In addition, opposition from employer groups and the absence of trade unions provide insights into current debates on the role of social partners in family policy reform (Cigna Reference Cigna2023; Pavolini and Seeleib-Kaiser Reference Pavolini and Seeleib-Kaiser2022).

This article is structured as follows. Section 2 introduces the case. Section 3 draws on comparative literature on interest group influence, party politics, and gender equality politics to formulate research questions and hypotheses. Section 4 translates these hypotheses into deductive process-tracing tests. Section 5 divides the results into four chronological stages, while section 6 evaluates the tests. Finally, the conclusion states the contributions and policy implications.

The 2019 Spanish paternity leave reform

The Spanish welfare state is traditionally classified as familistic and conservative, reflecting its historical lack of childcare services and support for working parents (Guillén et al. Reference Guillén, Jessoula, Matsaganis, Branco, Pavolini, Burroni, Pavolini and Regini2022). Although Spain has made significant strides in gender equality legislation in recent decades, comparative studies continue to rank it among Mediterranean states with weaker work-family support systems, particularly following the financial crisis (Garritzmann et al. Reference Garritzmann, Häusermann and Palier2022; but see León et al. Reference León, Pavolini, Miró and Sorrenti2019). Given the usual path-dependency of welfare structures and a context of fiscal constraints, Spain is not typically expected to implement substantial policy departures from traditional arrangements, let alone emerge as a leader in radical innovation (Bonoli Reference Bonoli2007).

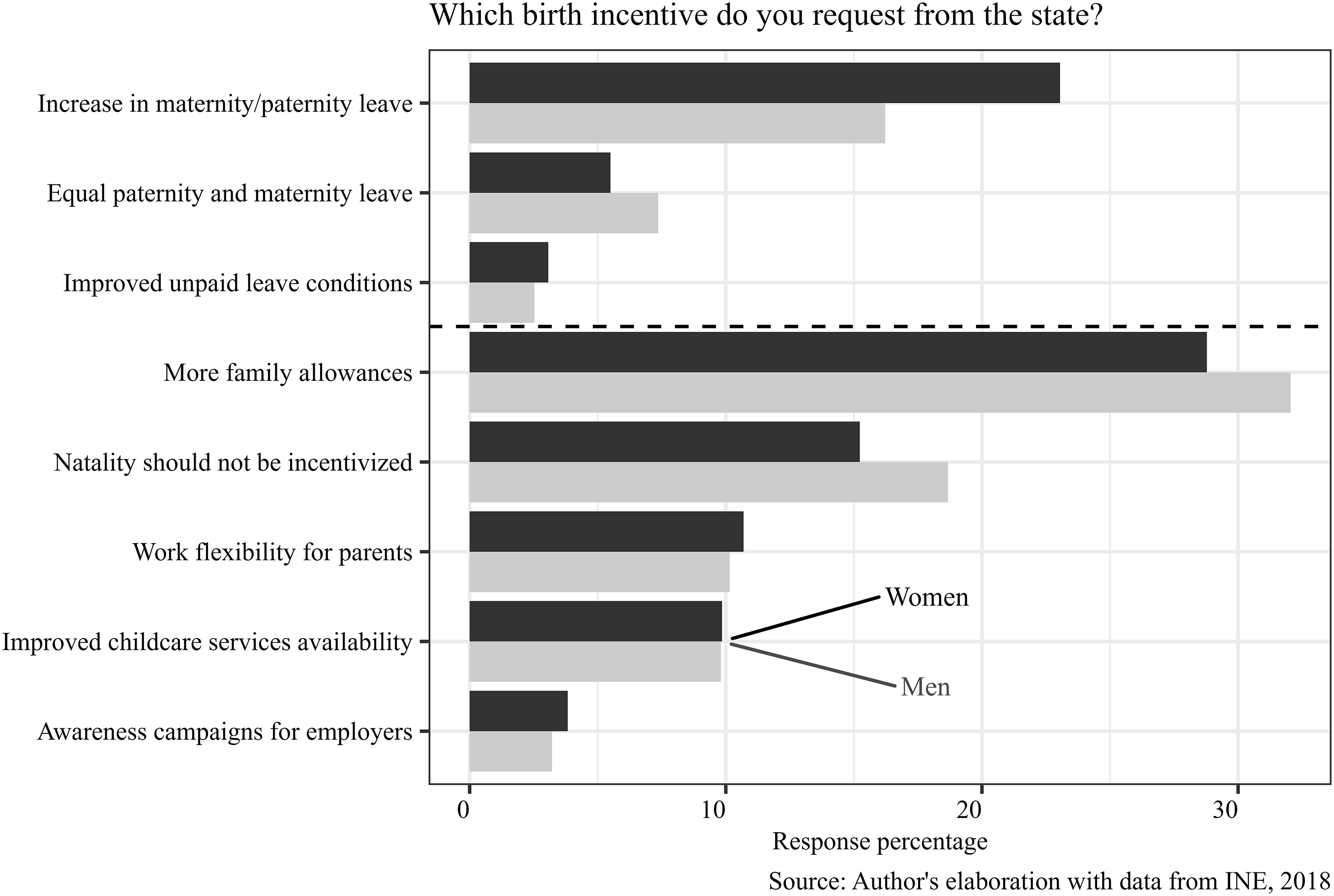

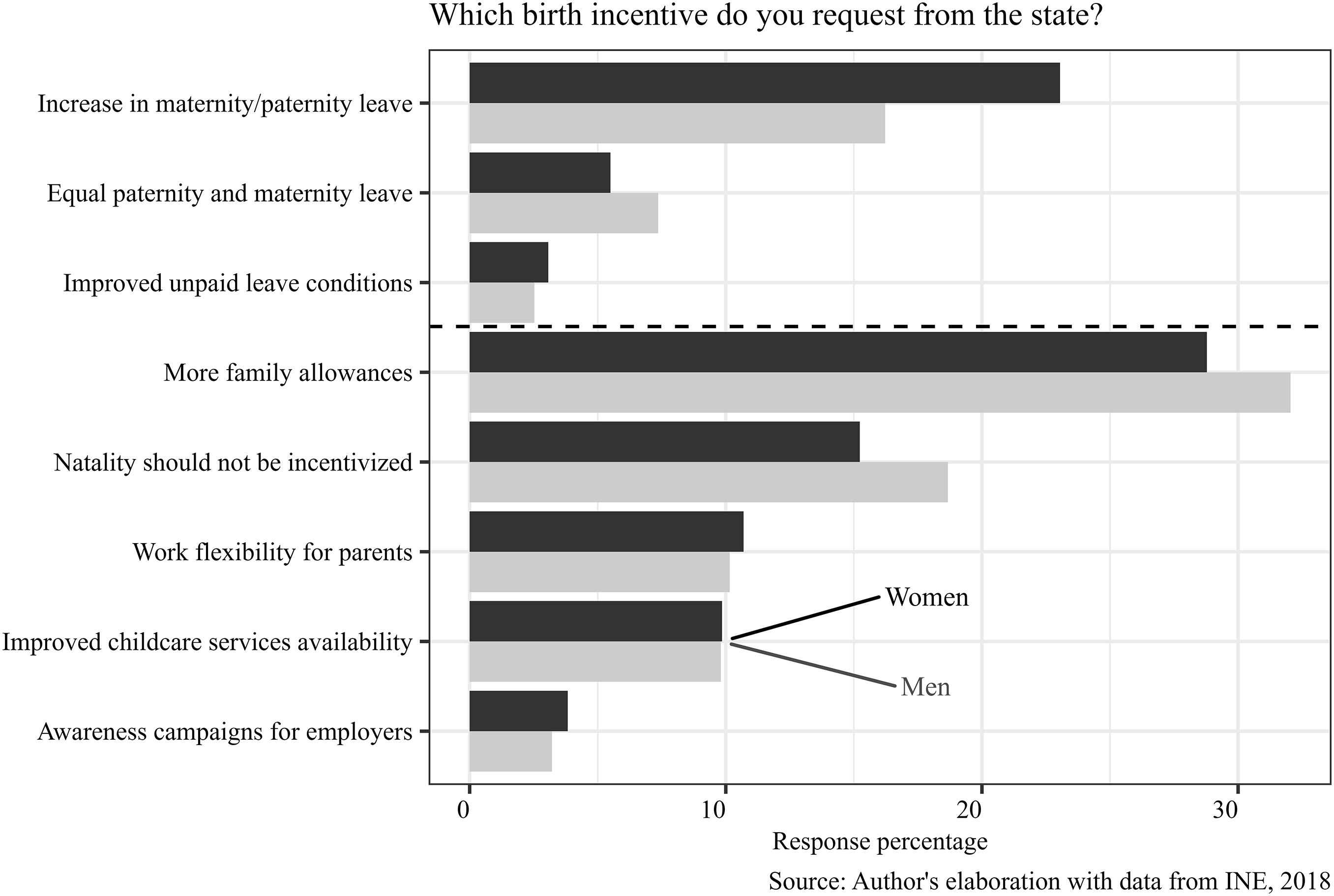

In this context, there has been neither a clear public demand nor European recommendations to fully equalize paternity and maternity leave. The post-reform survey by Cañero and Marinova (Reference Cañero and Marinova2025) shows that public opinion favors longer care permits over equality. The authors also refer to pre-reform public opinion data that signals that the measure had an inconsistent public acceptance (figure 1). Figure 1 shows that, when asked about natality incentives, the most favored response was increasing family benefits or expanding maternity/paternity leave, rather than full equalization. Although the question does not really gauge public acceptance of the proposal, it shows that leave equalization was never a salient public demand. Another piece of evidence lies in figure A1 in the supplementary material, showing that internet searches for paternity leave only spike after reforms are approved, not beforehand.

Figure 1. Public preferences for natality incentives in Spain, 2018.

International recommendations have consistently set minimum paternity leave requirements below those in Spain and have recently shifted focus to other areas. The EU 2019 Work-Life Balance Directive established a minimum of only 10 days of paternity leave, less than the five weeks Spain already provided before the 2019 reform (de la Porte et al. Reference de la Porte, Im, Pircher and Szelewa2023). In contrast, the directive also mandated two months of paid parental leave for each parent, a requirement Spain has not fulfilled yet, causing EU warnings (Escobedo and Moss Reference Escobedo and Moss2025).Footnote 1 In addition, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) has urged Spain to raise family benefits, noting that their low level contributes to high child poverty (OECD 2022).

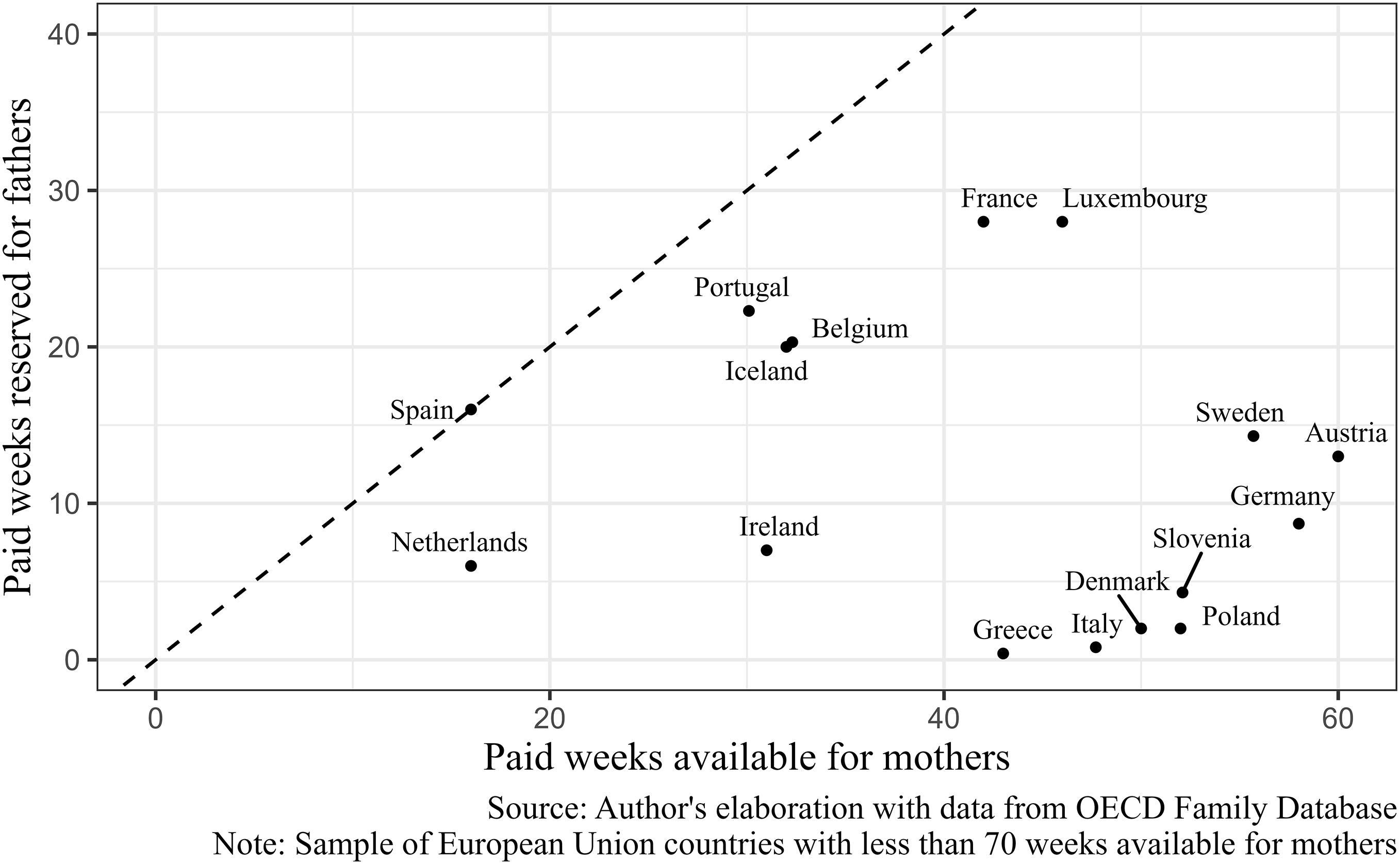

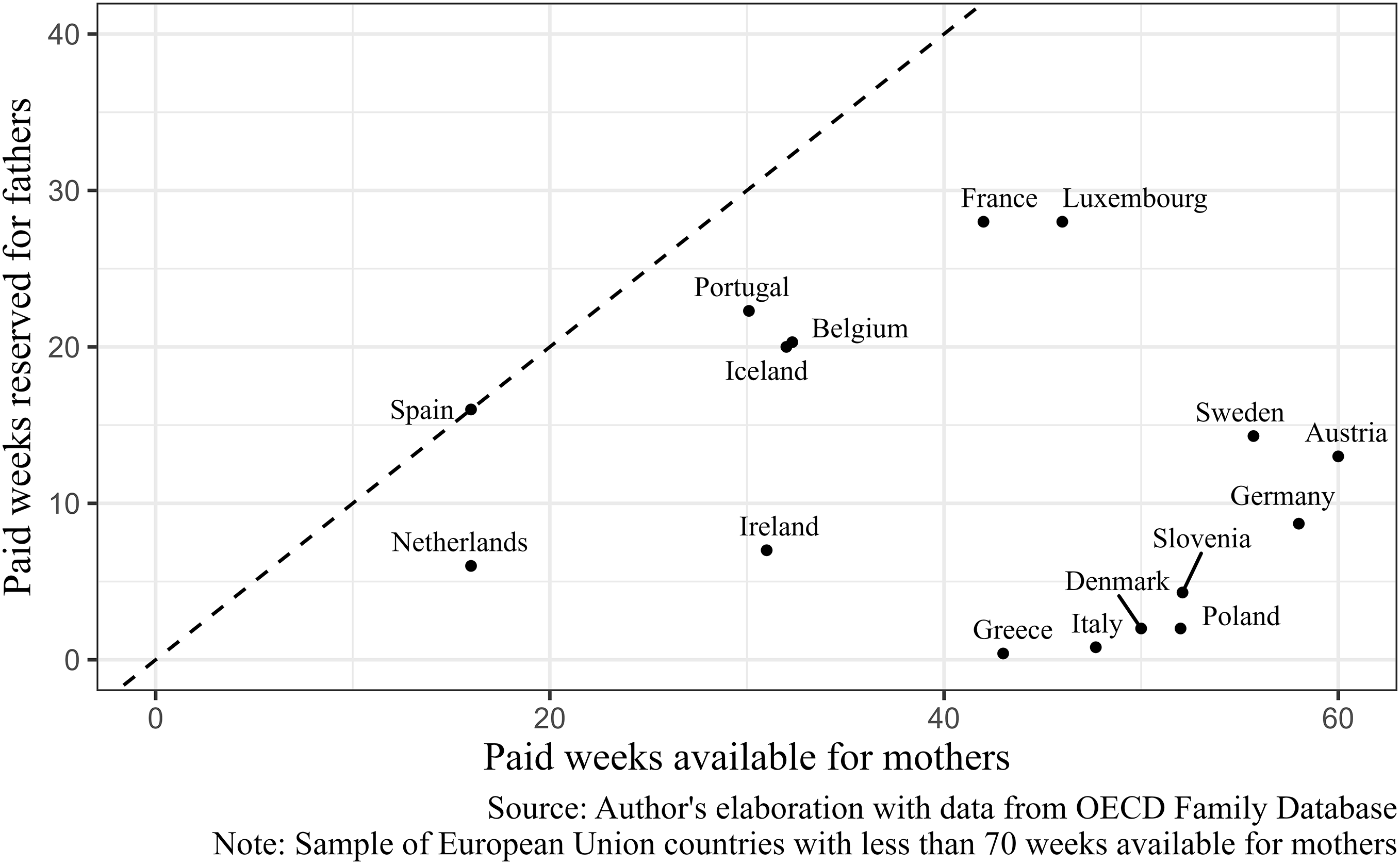

Against this background, the 2019 reform is particularly unexpected. Rather than meeting domestic and international demands for enhancing paid parental leave or strengthening family transfers, the government introduced a completely equal and non-transferable birth leave of four months for each parent. This reform places Spain at the forefront of the growing focus on balancing parents’ leave time, and it prioritizes this objective over others, such as allowing mothers to spend more time with their children. As figure 2 shows, Spain is the country with the shortest leave time available for mothers but also the only one where this is equal to the leave time reserved for fathers. This fact is often overlooked in comparative research, as it is customary to focus on Spain’s lack of paid parental leave (Szelewa and Polakowski Reference Szelewa and Polakowski2023).

Figure 2. Comparison of gendered leave entitlements in the European Union, 2021.

The main alleged objective of the reform was to redistribute care responsibilities and employment opportunities for men and women. Longer paternity leave seeks to incentivize father involvement in care and domestic activities, while making it equal to maternity leave also hopes to reduce gender discrimination in hiring and career advancement. Maternity and paternity leaves are now called “leave for the birth or care of a minor child” and are granted to the first and second “parent,” framed in gender-neutral terms (Escobedo and Moss Reference Escobedo and Moss2025). The leave incorporates full replacement rates with a high-income ceiling to incentivise uptake. Marinova and León (Reference Marinova and León2025) show that the reform doubled the proportion of men taking the full leave from 36 to 64%, a notable comparative success even if differences remain across contract types.

The political process behind the reform has not yet been studied in depth. As an exception, Meil et al. (Reference Meil, Wall, Atalaia, Escobedo, Dobrotić, Blum and Koslowski2022: 222) review the gradual expansion of paternity leave in Spain through the lens of party politics and argue that the measure was approved “to maximize electoral support.” However, there is no evidence of electoral drivers other than that it was approved shortly before elections, whereas public demand for the measure was (at least) unclear, as commented above. While Meil et al. (Reference Meil, Wall, Atalaia, Escobedo, Dobrotić, Blum and Koslowski2022: 220) do mention that “a social movement called PPiiNA” had been campaigning for the reform before its approval, this is not studied further.

This calls for a deeper evaluation of the role of PPiiNA by turning the focus to the literature on interest groups and feminist advocacy, given that with its 13 members in 2018, this can hardly qualify as a social movement. Moreover, this fact echoes Costain’s (Reference Costain1981: 100-101) discussion on how the women’s social movement, as a “partially organized expression of severe social discontent,” may evolve into a “represented interest” with access to the political system.

Interest groups, political parties, and feminist advocacy

This study seeks to uncover how political actors operated and interacted in the process behind the 2019 Spanish paternity leave reform. This interest aligns with the broader policy process tradition (Kingdon Reference Kingdon1984; Sabatier Reference Sabatier1999; Baumgartner Reference Baumgartner1993), which examines how political actors mobilize and form coalitions across venues as policy ideas move from agenda-setting to adoption. Due to the primary interest in PPiiNA’s advocacy activities, hypotheses are derived from the literature on interest groups, and particularly on theories about their typologies, tactics, and relationships with other actors across different venues. Given the gendered nature of paternity leave, further expectations are drawn from the literature on gender equality politics.

Political actors in the reform

Sub-research question (RQ)1 is: Which relevant actors shaped the 2019 leave reform? I anticipate that political parties (H1a) played a central role, as previous studies on parental leave reform consistently identify them as key actors, including for the Spanish case (Meil et al. Reference Meil, Wall, Atalaia, Escobedo, Dobrotić, Blum and Koslowski2022). While some find that center-right parties have advanced such reforms (Morgan Reference Morgan2013; Fleckenstein and Lee, Reference Fleckenstein and Lee2014), others argue that left or liberal parties have taken the lead (Alvariño and Thies Reference Alvariño and Thies2025; Bürgisser Reference Bürgisser, Garritzmann, Häusermann and Palier2022). Early evidence also suggests that PPiiNA (H1b) was influential, although the role of feminist interest groups in leave reform has been rarely studied (for an exception, see Ellingsæter Reference Ellingsæter2021). Employer associations (H1c) could also be a significant yet overlooked actor, as they often lobby to align parental leave policies with their interests (Pavolini and Seeleib-Kaiser Reference Pavolini and Seeleib-Kaiser2022). Recent research also points to the potential role of trade unions (H1d) in defending the interests of working women (Cigna Reference Cigna2023; Soler-Buades Reference Soler-Buades2025).

Interest group tactics

Sub-RQ2 is: How did interest groups act to influence the 2019 leave reform? It is widely argued in the comparative interest group literature that interest group characteristics determine their strategies. While various classifications exist, groups are commonly divided into those advocating for either diffuse or concentrated interests (Olson Reference Olson1971). Dür and Mateo (Reference Dür and Mateo2016) provide a more specific classification relevant to this case, suggesting that business and citizen groups contrast most strongly in their lobbying strategies and influence, with labor unions positioned in between.

Citizen groups are composed of civil society members advocating for public interest causes, such as social rights or environmental protection. PPiiNA qualifies as a citizen interest group, as it consists of feminist academics and activists advocating for policies that would affect all working parents. In contrast, business groups, commonly known as lobbies, are professionalized organizations representing the interests of firms. In Spain, the most relevant is the general employer confederation, Spanish Confederation of Employers’ Organisations (Conferencia Española de Organizaciones Empresariales – CEOE). Meanwhile, unions represent organized labor interests, the most important being the General Workers Union (Unión General de Trabajadores – UGT) and Workers’ Commissions (Comisiones Obreras – CCOO).

Interest groups adopt different influence strategies according to their varying resources and institutional access (Betzold Reference Betzold2013; Dür and Mateo Reference Dür and Mateo2013). The interaction between interest groups and policymakers is often described as an exchange, where politicians grant policymaking access in return for resources provided by these groups (Maloney et al. Reference Maloney, Jordan and McLaughlin1994). Citizen groups leverage policymakers’ need for “political information” resources, mobilizing their knowledge and influence over public support and social legitimation (Klüver Reference Klüver2013). Hence, their influence hinges on their capacity to mobilize public opinion in their favor to pressure policymakers (Betzold Reference Betzold2013). For instance, the anti-ACTA campaign exemplifies how citizen groups can mobilize public opinion to successfully challenge policy proposals despite limited resources (Dür and Mateo Reference Dür and Mateo2014). Hence, I expect PPiiNA to predominantly use outsider tactics based on public opinion mobilization (H2a).

In contrast, lobbies typically employ insider strategies, engaging directly with policymakers and participating in formal gatherings to advocate for and shape policy changes (Drutman Reference Drutman2015). Their economic power and access to privileged information afford them institutional access that citizen groups generally lack (Binderkrantz et al. Reference Binderkrantz, Christiansen and Helboe Pedersen2015). Furthermore, while public opinion modulates the success of citizen groups, it does not significantly affect business group influence (Rasmussen et al. Reference Rasmussen, Mäder and Reher2018). For these reasons, I expect CEOE to use insider tactics (H2b).

Labor unions face less collective action problems than citizen groups and more than business, as the heterogeneity of their interests lies in between. They can also rely on established corporate relationships with policymakers. Consequently, unions often adopt a mixed approach, utilizing both insider and outsider tactics depending on the issue at stake and the resources available (Dür and Mateo Reference Dür and Mateo2016). For these reasons, I expect unions to balance both insider and outsider tactics (H2c).

Influence along the policy process

Sub-RQ3 asks: How did the influence of these actors evolve throughout the reform process? Policymaking is commonly understood to unfold through the stages of problem definition, agenda-setting, policy formulation, adoption, and implementation (Sabatier Reference Sabatier1999). These phases take place across distinct venues with varying degrees of visibility and openness that shape access for different actors, such as legislative, executive, and administrative arenas (Kingdon Reference Kingdon1984; Baumgartner Reference Baumgartner1993).

Interest groups and social movements are often considered more influential during the agenda-setting stage than during later stages of policy formulation (Beyers et al. Reference Beyers, Eising and Maloney2010). This is because their outsider resources – public opinion and media visibility – are particularly effective for shaping agendas in institutions under public scrutiny such as parliaments (Binderkrantz et al. Reference Binderkrantz, Christiansen and Helboe Pedersen2015). By contrast, these tactics are less effective in executive venues with low transparency, where influence depends more on insider access than on public legitimacy (Chaqués-Bonafont and Muñoz Márquez, Reference Chaqués-Bonafont and Muñoz Márquez2016). Therefore, I expect PPiiNA’s influence to be stronger in the agenda-setting phase (H3a).

Business groups, by contrast, are expected to exert greater influence during the later stages of policy formulation, where insider access and specialized expertise are most valuable (Drutman Reference Drutman2015). In venues with limited public scrutiny, such as administrative settings or high-level executive meetings, business groups can leverage technical information and negotiate based on their capacity to affect policy outcomes (Boehmke et al. Reference Boehmke, Gailmard and Patty2013), thereby bypassing the need for widespread public support (Rasmussen et al. Reference Rasmussen, Mäder and Reher2018). This makes them particularly influential in shaping specific policy details within less transparent decision-making settings. Hence, I expect the CEOE to have a greater impact during the policy formulation phase (H3b). Finally, as I expect unions to mix outside and inside tactics, I also expect their influence to be balanced across time (H3c).

The party dynamics of feminist advocacy

Whether using insider or outsider tactics, interest groups often rely on parties as the main channel for influencing policy. However, mixed arguments exist about the class and gender determinants of PPiiNA’s influence on parties. Therefore, sub-RQ4 is: With which type of politicians did PPiiNA interact more successfully?

First, for gender equality reforms such as the 2019 paternity leave expansion, research has long pointed to the relevance of women’s representation. Beyond partisan affiliation, female parliamentarians tend to have different attitudes and voting behavior (Wängnerud Reference Wängnerud2009). As a result, many argue that the presence of women in parties is necessary for the consideration of gender equality and the introduction of gender-friendly welfare (Childs and Krook, Reference Childs and Krook1998; Kittilson Reference Kittilson2013; Son Reference Son2024). By the same token, Holli (Reference Holli2008) and Bereni (Reference Bereni2021) have pointed to the theoretical relevance of considering the alliance between feminist activists in different arenas, such as movements, parties, and state institutions (see also Holli Reference Holli2008). In this sense, Coil et al. (Reference Coil, Bruckner, Williamson, O’Connor and Gill2024) find that the presence of women in parliamentary committees increases women’s access as congressional witnesses. Hence, I expect PPiiNA to ally with female politicians across the left-right spectrum (H4a).

Second, there are reasons to believe that paternity leave may be a specific subtype of gender equality policy that preserves the relevance of the left. Htun and Laurel Weldon (Reference Htun and Weldon2010) distinguish between status-based policies, which address injustices affecting women as a social group (e.g. reproductive rights), and class-based policies, which address inequalities among women linked to the sexual division of labor and class (e.g. parental leave). Whereas status-based reforms tend to advance through feminist and rights-based mobilization across parties, class-based reforms may depend more on left parties because they concern redistribution and welfare provision (see also Annesley et al. Reference Annesley, Engeli and Gains2015). In fact, left-wing parties have historically tended to ally more with feminist movements than the right (Beckwith Reference Beckwith2000), be ideologically closer to the ideal of gender equality (Korpi et al. Reference Korpi, Ferrarini and Englund2013; Sainsbury Reference Sainsbury1996), and introduce pioneering work-family policies that are later embraced by the right (Alvariño Reference Alvariño2024). Hence, one could also expect PPiiNA to more successfully influence left-wing parties (H4b).

Third, interest group research has argued that, although advocacy still includes ideologically aligned parties, it increasingly prioritizes access to policymaking. Rasmussen and Jan Lindeboom (Reference Rasmussen and Lindeboom2013) note that while interest groups maintain formal links with historically aligned parties, those with more resources contact a broader range of parties to enhance their influence. Similarly, Marshall (Reference Marshall2015) finds that interest groups reach out to European parliamentarians based on their policymaking access rather than ideological affinity. Supporting this, Chaqués-Bonafont et al. (Reference Chaqués-Bonafont, Cristancho, Muñoz-Márquez and Rincón2021) show that in Spain, interest groups pragmatically target mainstream parties and salient issues to maximize impact. Therefore, one could also expect that PPiiNA would favor alliances primarily with parties in government rather than based on ideological similarity or gender lines (H4c).

A deductive process-tracing methodology

This case study follows a deductive process-tracing methodology to assess the hypotheses laid out above. Process tracing attempts to identify the causal mechanisms connecting the independent variable(s) to the outcome (Beach and Pedersen Reference Beach and Pedersen2019). The deductive variant works to evaluate established theories of interest group tactics and gender equality politics through process tracing “tests.” Moreover, the deep qualitative exploration of causal processes also complements quantitative large-N studies that link independent and dependent variables through hypothesized but unobserved causal mechanisms. Hence, this case can illustrate how feminist advocacy works in interaction with other political actors across the policy process.

The study relies on two data sources. First, it examines a range of parliamentary initiatives, including laws, decrees, binding and non-binding proposals, interpellations, and questions raised in the Congress and within the Equality and Labour parliamentary committees. Records of parliamentary debates also provide insight into actors’ positions and justifications. The results section refers to these 17 initiatives by the parliamentary code, and they are all listed in table A1 in the appendix. The investigation also included actors’ public statements and declarations in press and PPiiNA archival material.

Second, the study relies on 14 in-depth semi-structured interviews with key actors (table A2 in the appendix). The interview selection started with those participating in the parliamentary process and then expanded through snowball sampling based on initial interview results. Respondents encompass politicians from various parties, representatives of employer organizations and members of PPiiNA. The results section refers to these with an interview code displaying the organization and a number.

Respondents were asked about their activities and motivations during the policy process. To enhance reliability, interview responses were triangulated with document analysis. Interviews were conducted online between December 2022 and March 2024, and all adhered to ethical standards, with informed and withdrawable consent explicitly obtained before each conversation for participation, recording, levels of anonymity, and the use of quotes.

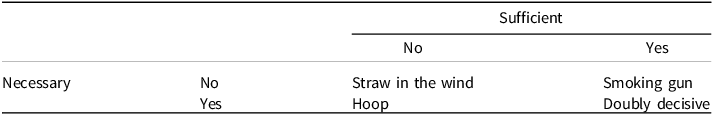

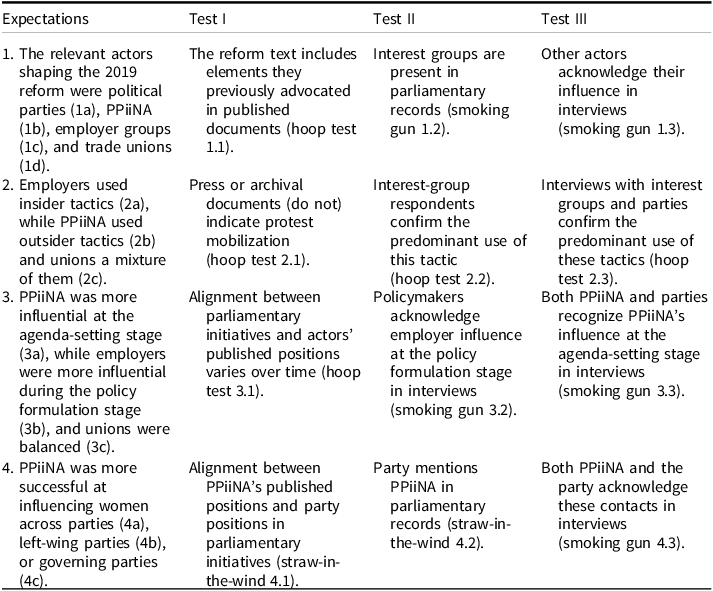

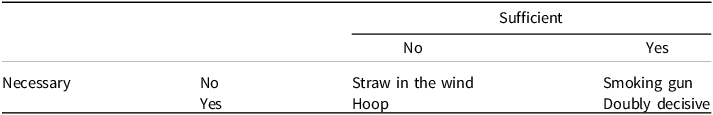

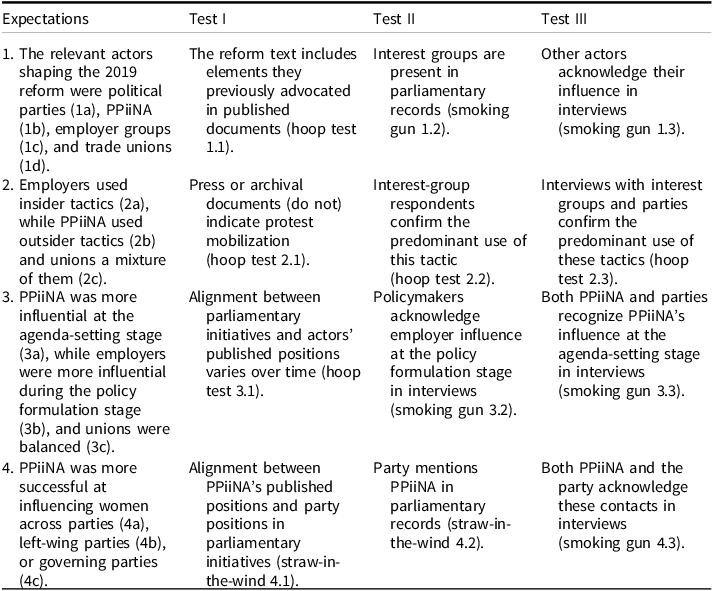

Following a deductive logic, the hypotheses for the four sub-research questions are analyzed through process-tracing “tests” designed a priori. A hypothesis can be rejected if it does not fulfill any of the “hoop tests,” which measure necessary conditions. Passing “smoking gun tests,” which measure sufficient conditions, confirms the hypothesis. “Straw in the wind” tests measure neither necessary nor sufficient conditions, but passing them adds evidence in favor. “Doubly decisive” tests account for both sufficient and necessary conditions, and passing them confirms the hypothesis and eliminates the alternatives. Table 1 displays the types of tests, and Table 2 summarizes all the tests used in this study.

Table 1. Types of process-tracing tests

Source: Adapted from van Evera (1997: 31).

Table 2. Set of hypotheses and process tracing tests

To assess who were the main actors involved (sub-RQ 1), a necessary condition is that the final reform text includes elements previously defended by them (hoop test 1.1). For interest groups, a sufficient condition is their presence in parliamentary records (smoking gun test 1.2), but this does not apply to the routine participation of political parties. Another sufficient condition is that other actors recognize them as relevant in interviews (smoking gun test 1.3), given that actors tend to emphasize their own role in policies that expand social rights and downplay the involvement of others (Berry Reference Berry2002).

To examine the tactics used by interest groups (sub-RQ 2), I seek evidence of protest mobilization through press reports or other published material (hoop test 2.1). This is complemented by the review of PPiiNA’s activity through their archival documentation. Furthermore, interviews with interest group representatives should confirm their perception of the predominant use of one of these tactics (hoop test 2.2). However, I only confirm the use of the insider tactic if both interest group representatives and politicians directly involved in the reform process acknowledge it (smoking gun test 2.3).

For evaluating whether the influence of PPiiNA is greater at the agenda-setting stage and the influence of CEOE is stronger at the policy formulation stage (sub-RQ 3), I set as a necessary condition that the alignment of parliamentary initiatives with these actors’ published positions varies with time (hoop test 3.1). Additionally, it is a sufficient condition if policymakers acknowledge employers’ influence during the policy formulation phase in the interview, given that politicians tend to de-emphasize this type of interaction (Berry Reference Berry2002) (smoking gun test 3.2). Meanwhile, I set as a sufficient condition that both PPiiNA and political parties recognize PPiiNA’s influence during the agenda-setting phase, but not during the policy formulation stage (smoking gun test 3.3).

To determine if PPiiNA contacted left, governing parties, or women across different parties (sub-RQ 4), I set up two “straw in the wind” tests: accordance between their published positions and the parliamentary initiatives of these specific parties (straw-in-the-wind test 4.1) and references to them by these parties in parliamentary records (straw-in-the-wind test 4.2). This evidence is yet insufficient because parties may independently take ideas from interest groups or invoke the organization to justify their own priorities. However, I set as a sufficient condition that both interest groups and the representatives from these specific parties acknowledge these contacts (smoking gun test 4.3).

The process behind the 2019 paternity leave expansion

Phase I: Party agenda-setting for establishing paternity leave (2002–2007)

Before discussions on equalizing maternity and paternity leave existed, a non-transferable, paid paternity leave was unsuccessfully proposed by several regional parties and the Spanish Socialist Workers’ Party (Partido Socialista Obrero Español – PSOE) (122/000140). Following its 2004 electoral victory, PSOE established the Equality General Secretariat, which initiated consultations with stakeholders on a comprehensive Equality Law, including a potential non-transferable paternity leave (PSOE1). The paternity leave proposal sparked significant debate among stakeholders. The Secretary General supported a two-week leave, while the Employment Minister advocated for one week, citing social security costs (El Mundo 2005). Employers opposed the measure both publicly (Cinco Días 2004) and in negotiations, with the Secretary General noting they were “the most reluctant” on the issue (PSOE1).

Amidst these discussions, the “Civic Platform for Non-Transferable Paternity Leave” was established by feminist activists with strong academic and political ties, aiming to push for a longer and non-transferable leave period (PPiiNA1). Initially, the platform’s alignment with part of the government’s agenda facilitated its rapid growth, attracting members from PSOE and its allied trade union, UGT, who saw potential strategic benefits in supporting the initiative. These connections, alongside the platform’s highly skilled membership, granted it early access to decision-making arenas (PPiiNA1). In fact, platform representatives were invited to a parliamentary hearing in 2006 to advocate their position (219/000709).

However, tensions surfaced as the platform began publicly criticizing the Employment Minister’s stance on paternity leave, leading PSOE and UGT affiliates to withdraw from the organization (PPiiNA1). When the Equality Law was passed in 2007, it established a two-week paternity leave with a scheduled expansion to four weeks by 2013 (PSOE1). In response, the civic platform broadened its objectives to advocate for full equalization of paternity and maternity leave duration. Reflecting this shift, it rebranded as the “Platform for Egalitarian and Non-Transferable Leaves of Birth and Adoption,” taking the acronym PPiiNA. From this point onward, feminist scholars and activists in PPiiNA began to operate with greater partisan independence.

Phase II: PPiiNA’s agenda-setting efforts for leave equalization (2007–2015)

Between 2007 and 2015, PPiiNA used diverse strategies to persuade parties to propose the equalization of paternity and maternity leave in parliamentary settings. PPiiNA organized public events and issued press releases and blog posts.Footnote 2 As explained by a representative: “We were carrying out tasks of political communication and social pedagogy, as we were in the media and giving talks” (PPiiNA2). These activities aimed to influence public and elite opinion. However, they cannot be fully considered successful outsider activities, as the events and communications were rather targeted to a specialized and highly educated audience. In contrast, PPiiNA avoided or lacked the capacity to organize large-scale public demonstrations to pressure the government. Moreover, although it is difficult to gauge their impact on public opinion, paternity leave seemed to remain a low-salience issue despite their efforts, likely overshadowed by austerity and the economic crisis. For instance, figure A1 in the appendix shows very low internet search trends between 2008 and 2016.

In contrast, PPiiNA’s insider strategy proved highly effective, with the organization energetically engaging policymakers across various parliamentary groups to advocate for their proposal. They held individual meetings with both advisors and high-ranking officials, including secretaries and ministers. Their media engagements were largely secondary to this approach, as press interactions often coincided with their visits to Congress, and blog posts primarily documented ongoing meetings with politicians, successes in gaining parliamentary responsiveness, or frustrations with political inaction. Although PPiiNA sought to engage high-level officials across departments, including labor and social security or party leaders, they report having been mainly received by female parliamentarians in charge of gender equality areas (PPiiNA1, PPiiNA2).

The first relevant parliamentary ally for PPiiNA was the gender equality representative from the Catalan center-right party, Convergence and Union (Convergència i Unió – CiU). PPiiNA’s spokesperson held frequent meetings with this member of parliament (MP), who sympathized with PPiiNA’s objective to equalize gender opportunities in the labor market. In the Equality Committee, she advocated policies to counteract how “in the eyes of employers, women continue to represent almost exclusively the disadvantages of work-life balance” (122/000012). However, her advocacy focused primarily on expanding paternity leave to four weeks, rather than on the full equalization of leave (PPiiNA1). Her efforts culminated in an agreement to support the government’s annual budget in exchange for this extension, as previously planned by the 2007 Equality Law (Cebreiro Reference Cebreiro2009).

However, the outburst of the 2008 crisis, increasing European conditionality over public deficit, and the arrival of a conservative absolute majority brought contextual challenges for PPiiNA. Fiscal pressures led the government to indefinitely delay the approval of the four-week paternity leave extension (PSOE1).

Still, PPiiNA actively pursued its reform goals by creating its own law proposal, demonstrating a skilled legal and academic background (PPiiNA 2011). Throughout 2011, they liaised with all political parties to encourage the parliamentary introduction of the bill (PPiiNA2). PPiiNA also organized an event in Congress to present the draft, where PPiiNA’s spokesperson encountered a generally receptive attitude (PPiiNA1). However, PSOE members chose not to participate as there was a conservative majority. While left-wing national and regional parties officially filed PPiiNA’s law in Congress,Footnote 3 they never allocated time to advance it for debate (PPiiNA1).

PPiiNA gained greater institutional access following a change in CiU’s gender equality representative. This MP recalls that she soon embraced PPiiNA’s objective of equalizing paternity and maternity leave (CiU1; PPiiNA1). She then brought PPiiNA’s draft law to the Equality Committee and began negotiating with other parties, where she recalls having “encountered reticence from many parliamentary groups, for instance PSOE” (CiU1). However, negotiations turned out successfully, and she was able to pass PPiiNA’s text as a non-binding motion in the committee in 2012, where it garnered unanimous approval (161/000918). Although lacking legal implications, she explained that this was still “a statement of intent, a signal of the direction in which we want to focus our policies” (CiU1).

Respondents argue that the cross-partisan consensus achieved within the Equality Committee was made possible by the unique character of the committee itself, where women representatives from different parties share concerns on gender issues. As the CiU MP explained:

In the [equality] committee, even if we are from right, left or centre, from here or there, we know what problems we constantly face and we agree about what hindrances are for women (…) but when we go to our parties this is never a priority. (CiU1)

The quote also refers to the committee’s president, an MP from the conservative People’s Party (Partido Popular – PP), who shared PPiiNA’s goals and ensured their access to discussions. She declared to have shared and openly favored PPiiNA’s initiatives despite broader ideological differences: “How can I be against something that a left-wing woman proposes when it is good for women?” (PP1). She also tried to lift PPiiNA’s demand through the party in government, where the Employment Minister also declared there was a generally supportive opinion (PP2), but her attempts were thwarted by budget constraints, perception, and opposition from the Finance Ministry (PP1).

Phase III: Parliamentary introduction of PPiiNA’s proposal (2016–2018)

The 2015 elections saw the rise of two new parties critical of corruption among the political elite and a lack of democracy: the liberal Citizens (Ciudadanos – Cs) and the left-wing We Can (Podemos – Ps). Cs swiftly prioritized family issues in its agenda, proposing an eight-week paternity leave with an additional 10 weeks transferable (Ciudadanos 2015). Cs’ policy proposals stemmed from their economic policy team, who argued to follow an evidence-based approach to enhancing women’s equality of opportunity, rather than being influenced by any particular interest group (Cs1; Cs2).

Meanwhile, Ps emerged as a grassroots party channeling popular mobilization and advocating for social and gender equality. Developing its inaugural program through participatory working groups, the party attracted some PPiiNA members drawn by ideological alignment (PPiiNA1; UP2). Leveraging their close relationship, PPiiNA persuaded the party leadership to request a policy paper in which they advocated for leave equalization (Pazos and Medialdea Reference Pazos and Medialdea2015; PPiiNA1). Despite initial resistance – particularly from the program secretary, who preferred extending maternity leave to 24 weeks – PPiiNA’s proposal ultimately gained backing from the feminism working group and was added to Ps’ 2015 program (UP3). “Initially it generated debate, but I believe that gradually the debate was overcome thanks to PPiiNA’s capacity for divulgation, as well as the document prepared by Pazos and Medialdea,” an official of Ps observed (UP2). From this moment onward, PPiiNA worked in close connection with Ps feminism secretary to champion the initiative in parliament, as confirmed in interviews from both sides (PPiiNA1; PPiiNA2; UP1; UP2).

After the elections of December 2015, unsuccessful government negotiations led to a repeat election in June 2016. During this interim period, one of Ps’ first parliamentary actions was to submit PPiiNA’s draft as a non-binding proposal (162/000147). PPiiNA actively engaged in outreach efforts, visiting Congress and sending letters to MPs from all parties (PPiiNA2). This may have contributed to the motion’s unanimous support, as Ps, CiU, and PSOE referred to and thanked PPiiNA’s activity in the plenary debate. Although PP members argued to have agreed with the objective, it ultimately abstained for financial reasons (162/000147; PP2).

After the 2016 elections, Cs supported a PP minority government on a compromise to extend paternity leave to four weeks by 2017 and subsequently to eight weeks by 2018, although they were only able to make it to five weeks amidst escalating political tensions between the two parties (214/000003; Cs1; Cs2; PP1). Meanwhile, We Can (Ps), now rebranded as United We Can (Unidas Podemos – UP) following its alliance with United Left (Izquierda Unida – IU), endeavored to present the PPiiNA-drafted bill as a binding law proposal in January 2017. However, this initiative was obstructed by the Congress Bureau, which was under the control of the PP and Cs (UP1). PPiiNA disagreed in meetings with Cs due to their proposal on transferability, which they perceived as contrary to their objectives (PPiiNA1). However, a Cs respondent noted that the decision to block PPiiNA’s proposal “was not so much because of a clash of models” or ideological differences, but rather due to “political consistency,” as Cs sought to advance their own recent legislative agenda and “PPiiNA was very highly visible around Podemos,” their political competitors (Cs2).

Unable to present binding proposals, UP’s Secretary of Feminism first made an interpellation to the Minister of Employment on leave equalisation in January 2017. The minister apparently agreed but emphasized the need to progress in accordance with fiscal capabilities (172/000052). The following month, the same MP presented a parliamentary motion in favor of the measure which garnered unanimous approval across all parties (173/000038). In parallel, PPiiNA maintained an intense activity, meeting with MPs across the party spectrum and publishing posts and press releases in favor of the measure. Therefore, this broad parliamentary support, including from the conservative government, may possibly stem from PPiiNA’s lobbying efforts. In their interventions, members from UP, CiU, and PSOE explicitly referred to the divulgation and research role of PPiiNA for advancing arguments and calculating the economic feasibility of the reform (173/000038).

Meanwhile, the heightened parliamentary focus on leave equalization drew the attention of employer organizations. The foremost business federation published documents and press releases expressing its opposition to any form of paternity leave expansion (CEOE 2017; Valverde Reference Valverde2017). Interviews revealed that employers, particularly those from small and medium-sized enterprises, were apprehensive about a regulation that could escalate their operational costs due to the need for worker substitution (CEOE1). Instead of extending paternity leave, CEOE proposed enhancing work-family balance and female employment opportunities through expanded childcare services and greater flexibility in the workplace. However, respondents from employer and governing parties did not report any direct interaction between them on this matter at this time (CEOE1; PP1; Cs1).

Phase IV: Elite final policy formulation (2018–2019)

In 2018, the conservative government was ousted following a no-confidence vote sparked by major corruption scandals. PSOE then formed a caretaker government, supported by a coalition of left-leaning and regional parties, including UP. According to PSOE sources, the new administration prioritized the equalization of paternity and maternity leave (PSOE3). The newly appointed labor minister assigned the reform’s negotiations to a secretary general of employment with relevant experience on the topic, while the key architect of the 2007 law was appointed as State Secretary for Equality (both interviewed and respectively coded as PSOE2 and PSOE1).

Both UP and PSOE swiftly presented binding law proposals to implement leave equalization. UP opted to abandon the text that was drafted by PPiiNA and develop a new legal document. On the reasons for this, the Secretary of Feminism from UP commented:

We know who the main architects were (…) [but] you have to bring into play not only the part of civil society that defends one side and supports it, but also those who represent other parts of civil society. (…) We were also very aware that the drafting must go through our legal and economic team because, well, we too have a criterion, always respecting the essence of text. (UP1)

PPiiNA initially retained some access to the legislative process. In the first few months, collaboration between the two organizations allowed PPiiNA to suggest specific modifications to the text (PPiiNA1; UP1). However, PPiiNA expressed dissatisfaction with UP’s redrafted proposal, criticizing it for diluting the gender equality focus of their original text (PPiiNA1). UP’s proposal was then debated in Congress on 26 June 2018, where it received unanimous approval for further consideration and was forwarded to the Employment Committee (122/000223).

Meanwhile, PSOE’s Law Proposition was presented on 1 August, debated and accepted on 10 October, and then directed to the Equality Committee (122/000268). UP representatives suggested that PSOE’s decision to present its own law was driven by the desire to claim credit for a policy that had garnered substantial parliamentary support, reflecting the intense electoral rivalry between the two parties in the gender equality realm (UP1). In contrast, PSOE members contended that the party had a historical stance in favor of extending paternity leave (PSOE3). The Secretary of Employment declared in the interview that “it was the Socialist Party’s project and therefore it was our law, also we did not share some of the considerations made at that time by Unidas Podemos” (PSOE2).

The following months involved complex negotiations in non-transparent formal and informal political settings without accessible records. In these, PPiiNA’s influence waned as UP engaged directly in negotiations with other parliamentary and administrative actors and with social partners. Heads of the gender equality area, leading the negotiations, diverged on whether parents should be incentivized to take leave simultaneously or separately. UP, aligning with PPiiNA, advocated for a minimal compulsory period immediately after birth to increase non-simultaneous leave time, thereby incentivizing fathers’ independence as primary caregivers (UP1). However, the Secretary of State for Equality instead supported a longer, six-week compulsory period to foster early father involvement (PSOE1).

In parallel, PSOE officials from the employment ministry engaged in negotiations with employer representatives (PSOE2; PSOE3). Employer groups remained resistant, citing the burden the measure would place on small businesses (CEOE1). Although CEOE respondents expressed dissatisfaction with the level of attention received from government, PSOE officials acknowledged accommodating some employer demands (PSOE2). This compromise was reflected in the requirement for workers to negotiate with employers regarding whether the additional 10 weeks of leave would be taken continuously or separately and on a full- or part-time basis. While UP negotiators strongly criticized employer involvement in shaping the policy (UP1), PSOE respondents argued that accommodating these demands would help ease implementation, recognizing the influence of employers on policy outcomes:

They allowed us, let’s say, a less traumatic transition for a better implementation of the standard. And this is what we wanted, to generate that culture, and to achieve its recognition as an achievement that was not excessively costly for the company. (PSOE2)

After gaining support from various parties and social partners, UP and PSOE reached an agreement on the final reform draft. Due to time constraints before the elections, the work in committees was halted, and the government approved the measure as a decree (Royal Decree 6/2019). On 3 April 2019, the decree was ratified in parliament with quasi-unanimous support (Law 6/2019). In the debate, a UP parliamentarian argued that “This is not even your proposal or mine, it is the proposal of the social movements, of the associations that have been working for this for decades.” Only the PP voted against it, dismissing it as an electoral tactic, but reiterating its support and promising to approve the reform should they win the election. The expansion was implemented gradually: 9 weeks in 2019, 12 in 2020, and 16 in 2021.

Discussion of results

Political parties, PPiiNA, and employer organizations were the main actors shaping the 2019 Spanish paternity leave reform (sub-RQ1). Employer opposition to the expansion of paternity leave contradicts recent arguments about their potential support for work-family policies (Pavolini and Seeleib-Kaiser Reference Pavolini and Seeleib-Kaiser2022). Previous studies show that employers may support initiatives that promote female labor force participation, such as reducing lengthy parental leave or expanding childcare services (Seeleib-Kaiser Reference Seeleib-Kaiser2016). However, the findings here suggest that they are less likely to back policies expanding caregiving rights for fathers when these weaken their workplace attachment.

Meanwhile, unions were notably absent from parliamentary records and interview references (smoking gun 1.2 and 1.3). PPiiNA’s spokesperson mentioned that “in short, the unions have not helped us” (PPiiNA1), while the UP representative added that, although “this has not been the ultimate priority of these unions’ leadership (…) we have not encountered any obstacles from them” (UP1). This adds relevant nuances to previous findings on the emerging role of unions for women’s working rights (Cigna Reference Cigna2023), pointing to relevant variance among countries or policy fields.

The findings also reveal that employers exercised an insider strategy, shaping policy design to align with their demands during the final stages of formulation (sub-RQ2, hoop test 2.2). This confirms a pattern already predicted by previous studies that is difficult to document, given politicians’ reluctance to acknowledge employer influence. Meanwhile, the behavior of PPiiNA contrasts greatly with the expectations about interest group typologies and tactics. The platform initially organized public events and published press releases to mobilize public opinion, as citizen groups typically do (Dür and Mateo Reference Dür and Mateo2013), but this strategy generally failed. Instead, PPiiNA was remarkably successful in building insider alliances with politicians (hoop test 2.1 and 2.3).

Who were these politicians that collaborated with PPiiNA (sub-RQ 4)? Activists reported seeking collaboration with parties across the political spectrum (except the radical right) and especially targeting PP while in government (PPiiNA1). Nonetheless, their effective allies were systematically female politicians from gender equality portfolios across parties (smoking gun 4.3). Notably, politicians from center-right parties PP and CiU relayed PPiiNA’s ideas to the parliament through non-binding motions, strengthening the platform’s influence over the parliamentary agenda between 2007 and 2017 (sub-RQ3). The Gender Equality Committee emerged as a key venue for women across parties to debate over PPiiNA’s proposal.

Nonetheless, it was ultimately left-wing parties that introduced a binding proposal in parliament and approved the reform, with UP even citing PPiiNA in 2018 (smoking gun 3.3; straw-in-the-wind 4.1 and 4.2). Hence, although PPiiNA relied on cross-partisan feminist alliances to place its ideas on the parliamentary agenda, its eventual influence on policy output depended on partisan support. Female politicians from right-wing parties expressed frustration at their limited capacity to persuade party elites to adopt these measures (PP1, CiU1). Moreover, as UP and PSOE later set to formulate the details of the law, PPiiNA was excluded from the drafting process, and employers’ concerns gained prominence (Sub-RQ 3; smoking gun 3.2).

Conclusion

This article offers valuable insights on interest groups and gender equality politics. Addressing the latter, while the importance of women’s presence in politics for advancing gender equality is well established, how gender operates within political institutions in practice remains less explored. Existing studies often attribute reforms to female politicians’ preferences and legislative behavior, particularly in the context of class-based gender equality policies such as parental leave (Kittilson Reference Kittilson2013; Htun and Weldon, Reference Htun and Weldon2010; Annesley et al. Reference Annesley, Engeli and Gains2015). The findings here reveal a distinct mechanism through which descriptive representation matters: the formation of women’s alliances across institutional arenas.

This mechanism has been theorized but rarely examined empirically (Holli Reference Holli2008; Bereni Reference Bereni2021), and existing evidence remains mixed (Holli Reference Holli2012 finds negative effects and Coil et al. Reference Coil, Bruckner, Williamson, O’Connor and Gill2024 positive effects). In the case studied in this article, female politicians opened institutional avenues of access to feminist advocacy groups and introduced their claims into parliamentary debates. This suggests that descriptive representation can impact policy output not only through the activities of politicians themselves, but also by enabling feminist advocates to access policymaking. This echoes recent findings on the relationship between ethnic minority representation and advocacy in the United States (Minta Reference Minta2020).

These findings also contribute to interest group research by identifying the conditions under which citizen groups can successfully employ insider tactics. The access obtained through feminist alliances was not limited to their presence in parliamentary hearings (as in Coil et al. Reference Coil, Bruckner, Williamson, O’Connor and Gill2024), but it extended to routine consultation, modifying legal drafts, and their own draft being presented in parliament, activities typically reserved for business lobbies (Dür and Mateo Reference Dür and Mateo2016). This suggests that the influence and tactics of interest groups can differ across policy fields and that similar patterns could arise in other issues that facilitate alliances between professional politicians and citizen activists.

What else explains PPiiNA’s success? Alliances between civil society and policymakers may hinge on shared ideas. As shown in Alvariño (Reference Alvariño2025), PPiiNA’s achievement could have been facilitated by their alignment with the “equality feminism” values of gender equality in employment opportunities that exist among Spanish politicians. Moreover, a highly skilled membership may be key for other citizen groups to obtain insider access. In this case, PPiiNA’s members were veteran feminist activists and academics with strong political and cultural capital, able to present persuasive arguments and build alliances with policymakers.

Despite the success of PPiiNA in achieving its main policy objective, two key limitations remain for the legislative capacity of cross-institutional feminist alliances. First, results show that while women across parties can help civil feminist advocates to influence the agenda, they may struggle to secure the support of their party to approve laws if these go against their ideology or electoral strategy. This stresses the relevance of partisanship to shape policy output. Second, the opaque venues where final policy details are formulated remain a challenge for the participation of civil actors in decision-making.

Concluding with policy implications, equal and non-transferable paid leave is a valuable step toward preventing gender-based hiring discrimination, encouraging fathers’ involvement in caregiving, and accommodating diverse family arrangements. Nonetheless, the 2019 reform remains insufficient to eliminate gender inequalities in care and employment in Spain. With a total duration of four months per parent, the leave is too short to ensure adequate care coverage, even when taken sequentially, and public childcare from age one is not yet universally guaranteed. As a result, many mothers continue to rely on unpaid leave or reduced working hours, perpetuating gender disparities and heightening financial strain (Fernández-Kranz and Rodríguez-Planas Reference Fernández-Kranz and Rodríguez-Planas2021). While maintaining leave as equal and non-transferable has clear benefits, expanding its duration remains essential to advance gender equality in Spain.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0143814X25100925

Data availability statement

This study does not employ statistical methods, and no replication materials are available.

Acknowledgments

I am very grateful to Laura Chaqués Bonafont and Margarita León for their in-depth discussions on this article. I am also grateful to the participants of the ECPR panel, “Influence: Comparative Contexts and Case Study Research,” for their constructive feedback and supportive atmosphere, including, among others, Anne Rasmussen, Wiebke Marie Junk, and especially Thomas Holyoke, who acted as a discussant. Additionally, I thank the participants of the IGOP research seminar at UAB for their thoughtful discussion and especially Dani Marinova for her generous and helpful feedback on earlier versions of this article.

Funding statement

This work has received funding from the European Research Council under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program (grant agreement no. 882276).

Competing interests

The authors report there are no competing interests to declare.