Mwaura’s Malaise

For much of the time Mwaura spent at home from university, he was in a state of boredom and borderline depression. With his university lecturers on strike through 2017 and early 2018, he was forced to return from campus, where he remained stuck on the homestead. Lacking a job, he spent long hours playing FIFA, watching television, and occasionally spending time at the roadside with other ‘idlers’ (as he liked to call them) of Ituura like Stevoh, who we met in Chapter 2. ‘See our lives’, was Mwaura’s favourite catchphrase in these months, an invitation for me to observe the predicament he felt himself to be in. He regularly commented on the wider corruption that afflicted Kenya as having a direct and detrimental effect on what he called in English his and his family’s ‘progress’. Mwaura lamented his joblessness, a situation he sometimes pinned upon President Uhuru Kenyatta’s broken promises to create tens of thousands of jobs for the country’s unemployed youth. But he also looked towards others in the neighbourhood, successful people who had access to employment opportunities, people he believed were concealing opportunities from him. As we shall soon see, Mwaura directed his scorn at others in his immediate vicinity, ‘well-up’ (i.e., rich) neighbours he believed who could not offer him a ‘connection’ for fear he would surpass them.

As a soon-to-be graduate, Mwaura felt the pressure to be successful, not least through comparisons with his peers from school who had gone on to greater things. In March 2018, we found ourselves at home, speaking about the jealousies that he saw as characteristic of life in his neighbourhood and in Kenya more generally.

As much as you don’t have anything against the person [PL: It’s not personal. It’s about your relationship with yourself] Exactly. There’s this friend of mine, I did better than him in high school. He used to be my very good friend, we used to waste a lot of time together. We used to hang out a lot. After high school – right now he’s in US doing medicine and I’m in Kenya doing nothing! Man, you feel challenged. As much as he’s my friend [PL: He’s in US?] Imagine! Maaan!

Spending day after day at home, it was difficult for Mwaura not to compare himself to others. But the pressure Mwaura felt also came from a feeling that other families in Ituura might be taking pleasure in his misfortune. His joblessness had apparently become a topic of interest in neighbourhood gossip, and Mwaura already felt the pressure to protect his reputation as a university student, not least for his parents’ sake. He was one of the few youths from the neighbourhood to go to university, whereas most of his peers worked for piecemeal wages in the informal economy of Nairobi’s peri-urban periphery, as construction workers or as tea-pickers. With this relative prestige came the need to guard it, especially from others who might have sought to question his future, and his commitment to it.

Like right now if people see me drunk and I’m in university and their children are not in university, they’ll like spread the stories around Ituura! Now they’ll be telling everyone, even though he’s at school, you know he’s always drinking, he doesn’t do any study. There was a time I had some cigarette photos go viral when I was in high school. My dad was very angry with me. People were saying I might even have cancer. You know these old women. [PL: But does that matter to your mum if people talk?] Yeah, that’s the problem, because she can’t be more proud anymore because, you know. [PL: People think …] Her son is nothing, he’s doing nothing. He’s doing nothing at university. [PL: So you need to be the model student?] You need to be the role model for the others who are not at university.

That domestic failures were palpably felt in local networks of gossip points us towards the competitive nature of aspirations in Ituura. People pursued success within the boundaries of their families while looking over the hedgerows and fences that separated homesteads and gazing at the relative fortunes of others. As we shall see in this chapter, the competitive dynamic that plays out between families has made seeking dependence upon others rather difficult. Families and their members are supposed to ‘hustle for themselves’, or so goes the dominant discourse of aspiration in contemporary Kenya, one that sees individuals as responsible for their fortunes, obfuscating both structural constraint and contingent misfortune.

Jobless, and with expensive university fees to pay, Mwaura recognised the burden his education placed not only on him to become successful in the future, but also on his parents in the immediate moment, especially his mother Catherine. In 2017, her financial networks were providing the only respite to the situation brought about by his father’s lack of work. Kimani earned only intermittently; his vehicle’s near-constant state of disrepair regularly affected his work, sending him into troughs of debt as he scrambled to generate the cash for repairs. With Kimani’s work precarious and uncertain, Catherine was often left to support her own household with odd jobs sourced from friends and contacts in the neighbourhood.

Catherine’s search for money through her social networks in the neighbourhood and beyond was critical to the family’s income, and their ambition for Mwaura’s education and social mobility. Throughout my fieldwork and beyond, Catherine cultivated relationships with wealthy families from the local neighbourhood, seeking cash loans that she struggled to repay through her husband’s sporadic wages. Such requests for help revealed her own family’s relative poverty and sometimes led to a peculiar kind of conflict – a quiet distancing on the part of those families from their friendships with Catherine. As this chapter will show, these conflicts and anxieties about money put a heavy burden on her, creating stress and exhaustion, and compounding the various illnesses that afflicted her in 2017 and 2018.

In discussing Catherine’s pursuit of loans and favours from friends, this chapter reflects on the status of women’s work within a landscape of economic precarity, where low and precarious wages have undermined the wage-labouring capacity of men to return wealth to the homestead. Catherine’s work underpinned the household, and in Kimani’s absence, she sometimes appeared to me as practically a single mother. This chapter charts her deep investment in the sustenance of a patriarchal household, illuminating her status as a mother within social relations in Ituura. As Amrik Heyer showed in her ethnography of female market traders from the adjacent Murang’a County, a history of male labour migration had turned women into household ‘sustainers’, generating wealth through their kinship networksFootnote 1 (see also Davison Reference Davison1989). Such observations are echoed today in the work of Sibel Kusimba, Yang Yang, and Nitesh Chawla (Reference Kusimba, Yang and Chawla2016), who have written about women as ‘heartholds’ of wealth, knitting together kinship networks to mobilise money in emergencies. Such positions of economic provision allow women to generate status as responsible persons in their own right, trusted with money not only within their families but within wider economic networks where loans are given between households to service individual debts. But as Kusimba, Yang, and Chawla also noted, such responsibilities also came with pressures to source cash in times of need. As this chapter shows, reputations were at stake for women like Catherine when they went about borrowing money. The failures of her husband to generate cash incomes exposed her own reputation as a borrower: she was seen by others as ‘broke’, unable to repay her loans.

This chapter reflects on the actual material income of a household in central Kenya – where the patrilineal ideal of hard work and ‘off-farm income’ (Chapter 3) is shown to be buttressed by a different sort of gendered work in the neighbourhood – relation-making, the work of creating caring relationships as a means of support during times of need. But at the same time, the chapter discusses the difficulty of pursuing economic assistance in a neighbourhood of competitive aspiration and economic distinctions. In this regard, the chapter makes a departure from a number of anthropological studies of rural Africa that have stressed the capacity of social relations to incorporate the poor and the needy, often due to what is seen to be a cultural tendency towards relationality. In his study of village life in rural Togo, Charles Piot (Reference Piot1999) described his Kabre interlocutors as adhering to a type of ‘relational personhood’ that he saw as orienting various dimensions of social and economic life from the sharing of food to coming-of-age rituals. Writing in a similar vein in The Nature of Entrustment (Reference Shipton2007), Parker Shipton described how Luo people (referred to holistically as ‘the Luo’) in western Kenya are committed to forms of ‘entrustment’, where loans and gifts flow freely between persons. Like Piot, Shipton emphasises the altruistic nature of economic life in western Kenya, likening it to a form of ‘generalised reciprocity’ (Shipton Reference Shipton2007: 116). For Shipton’s Luo, help is never far away. More recently, James Ferguson’s (Reference Ferguson2013) now classic essay ‘Declarations of dependence’ argued that positive desires to be incorporated within hierarchical relationships of economic obligation have had an enduring social logic in southern Africa.

These accounts paint highly optimistic portraits of economic life and obligation when compared to what Kenyans experience in Kiambu today. Like a number of other contexts, socio-economic stratification has oriented social life away from such relationalities and dependencies, and towards fragmented, particularistic interests (Seekings Reference Seekings2019; Danielsen Reference Danielsen2021).Footnote 2 Against the backdrop of such delimited networks of economic assistance, the chapter focuses on how Catherine adopted what Susan Reynolds Whyte and Godfrey Etyang Siu (Reference Whyte, Siu, Cooper and Pratten2015) call ‘a disposition of civility’ in order to pursue money for her household. Whyte and Siu describe civility as ‘a kind of watchfulness for positive possibility’ (Reference Whyte, Siu, Cooper and Pratten2015: 28), including the avoidance of conflict and ‘checking out people with potential resources’. As Tom Neumark (Reference Neumark2017) has shown in Nairobi’s Korogocho settlement, civility involves taking care not to overburden friendships with too many requests for economic assistance. And as Elizabeth Fox (Reference Fox2019: 35) has shown in her research amongst the ger districts of Ulaanbaatar, civility involves ‘anticipating relations’, a form of ‘speculative relation-making’. Speculation is an apt metaphor here, drawing attention towards relation-making as a wager on future possibility, rather than a certain return. As Whyte and Siu warn, ‘There is an element of chance in relying on another person to help you. He may … turn indifferent’ (Reference Whyte, Siu, Cooper and Pratten2015: 22).

Taking inspiration from these accounts, the chapter underscores the need to keep relationships open and potentially productive through careful management and maintenance, but also through forms of investment: caring labour in particular. The chapter takes inspiration from anthropologists who emphasise the social membership made possible through acts of care, that it is given in the hope of being cared for in the future (Borneman Reference Borneman and Faubion2001: 43). Claudia Liebelt (Reference Liebelt, Alber and Drotbohm2015) has shown how ‘gifts of care’ given amongst Filipina carers integrate women in all-women communities – a form of gendered gifting that ameliorates the economic uncertainties they experienced in the course of migrant care work in Israel. In peri-urban Kiambu, the work of hands, affective dispositions of friendliness and openness, are also vital tools for the creation of social membership, the ‘gifts of care’ that characterise friendships.

Such possibilities for creating relations through care recall the friendships between non-kin women, known as chinjira, that prevail in southern Malawi. Megan Vaughan (Reference Vaughan1983) showed how Mozambican labour migrants dwelling in villages of southern Malawi created relationships with local women in order to use their gardens to grow their own food. Such friendships allowed migrants to complement their household budgets and ‘escape some of the constraints of their economic circumstances’ 283. In a similar regard, civility involves the deliberate creation of empathy through ‘co-presence’, counting on what Thomas Widlok has described as one of the main principles of sharing – that people ‘are sufficiently able to put themselves into the situation of others to be able to know what the intrinsic goods of shared objects are for fellow humans without any demand being uttered’ (Reference Widlok2013: 21). It relies on the moral obligations generated through proximity (Ferguson Reference Ferguson2021) and through reproductive household labour: through helping other families cook. Such labour also had a deeply affective quality, involving caring for other local women at burials, tending to the bereaved, and simply ‘being there’ in times of need.

Exploring these relations, the chapter shows how the practice of ‘civility’ remained a speculative enterprise, one trusting that the affection of others would prevail and bail one out of trouble. But as the chapter goes on to show, civility regularly runs up against material limits, encouraging women like Catherine not to rely on those friendships absolutely, but to seek an income from other means, experimenting with different livelihood options in the neighbourhood and beyond – pursuing what James Ferguson (Reference Ferguson1999: 251) once called ‘the full house’ of income-generating strategies. In a context where dependence on others is shunned and avoided, seeking assistance is a risky and uncertain prospect. In Ituura, this uncertainty left its mark on those who had little alternative but to ask for aid from others. Mwaura himself only belatedly realised the full extent to which his mother had suffered for his future, and how her stresses about money had taken their toll on her mind and body. In 2020, when Catherine died, he would recall that in her final year of illness, ‘she had a lot of things in her head’.

Sociality in Ituura: First Impressions

When I began my fieldwork amid the homesteads of Ituura, the initial impression I formed of social life was one of positive mutuality between different families. Catherine and Mwaura introduced me to their friends and neighbours through numerous household visits over many evenings spent drinking tea and speaking broken Gĩkũyũ in front of Mexican telenovelas dubbed into English. These visits shaped my impression of Ituura as a place of conviviality. Mwaura and Catherine appeared to be on good terms with many of their neighbours, happily greeting them in the neighbourhood’s backstreet.

If fences and hedges separated individual plots, then through our household visits, Catherine and Mwaura introduced me to a world of comings and goings, especially between female friends from different households. Women from neighbouring households frequently assisted each other with household work – with cooking for guests, but also cleaning and gardening. By contrast, I could not help noticing in those early months both the absence of men (especially middle-aged men during the working week), and the prevalence of a style of matrifocal sociality (Neumark Reference Neumark2017: 750). Even where men from local households were not working, they could appear rather absent from neighbourhood social relationships. At weekends, local men continued to spend time away from the homestead, often frequenting local bars. It was a rarity to find men visiting each other’s houses as often as women did.

Such instances of women spending time together, watching soaps on the television, cooking, and talking were characteristic of every weekend of my fieldwork, if not every other day. These were such ordinary occurrences that practically no single occasion stood out in my fieldnotes. They were typical of a social context in which contingent friendship plays an important role in everyday life – more so than formal kin relations. Male residents of Ituura who have inherited land there are rather more formally connected to their patrilineal families, since they met occasionally to discuss together matters concerning the care of their parents if they were elderly, or those concerning inheritance and land management if their holdings had not been sub-divided. But in general, although ostensibly based on a ‘localised patriline’, social relationships in Ituura were rather more fluid, evoking friendship rather than kinship in formal terms, neighbourhood rather than the patriline (Abrahams Reference Abrahams1965: 172–3; Vaughan Reference Vaughan1983: 282–3). Some of Catherine’s best friendships in Ituura were with women who were not directly related to her husband.

It was through these social relationships that Catherine herself was recognised as an upstanding mother, a person of repute, in Ituura. In Gĩkũyũ-speaking contexts, as in Bantu-language areas across the subcontinent, women are regularly referred to as ‘mother of’ their eldest child, ‘nyina wa Mwaura’. Kinship terms like these evoke the respect that comes with providing for one’s family, and playing a wider role in neighbourhood affairs. Catherine knew practically everyone in the neighbourhood, and was involved in a wide array of associations, especially women’s rotating credit groups (ciama, pl., kĩama, sing.). Catherine was popular too. Quick to laugh, and often teasing others, she won friendships with neighbourhood residents from a range of backgrounds through her sheer force of character.

At the beginning of my fieldwork, Catherine kept her money troubles private from me. At one point, she sent Mwaura and me out of the house in order to welcome guests from a particular savings group, having spent the whole day preparing dinner for them. But it was not long before I began to understand precisely how much she was relying on others in the neighbourhood for short-term loans, and the friction these dependencies sometimes caused.

Catherine and Mama Nyambura: A Friendship

At the beginning of my fieldwork, Catherine and Mama Nyambura were best friends. Hardly a few days went by without the latter visiting Catherine’s homestead, either on her way to where she worked at a kiosk in nearby Ruaka Town or on her way home in the evenings. If she found Catherine at home, they would inevitably end up gossiping in exaggerated tones of astonishment and mirth about local affairs, laughing raucously, for instance, as they did when impersonating the ‘bad children’ (watoto wabaya) of the neighbourhood who played amongst the hedgerows of Ituura’s backstreets and regularly demanded bread from passers-by (‘Nataka mkate! Nataka mkate!’). It was just one example of their regular criticism of the negligent parenting they observed amongst their neighbours.

Both Catherine and Mama Nyambura could laugh at others in the knowledge that their families were ‘progressing’, though not exactly in the same terms. In 2018, Catherine’s daughter Njoki (seventeen) was boarding at a fairly reputable secondary school in northern Kiambu County. That Mwaura was attending university and his sister Njoki secondary school was a matter of great pride for Catherine. After Njoki had returned to school following a mid-term break spent helping her mother at the homestead, Catherine proudly showed me the backpack that the school had given her daughter as a prize for her excellent grades. Catherine also recalled Mwaura’s days at school when the teachers had identified his academic capability – ‘Mwalimu alijua [The teacher knew] he is clever!’

The feeling of pride Catherine took in her children’s achievements were matched by her anxiety over the finances involved. ‘Ngai, Peter, it’s expensive’, she told me one evening in front of the stove. ‘When they are finished [with school], then I can relax.’ The cost of Mwaura’s education became a major burden for the family throughout late 2017 and 2018. Kimani’s long spells without work during this period meant that the family was starved of cash. Putting money together for Mwaura’s education costs – which ran into the tens of thousands of shillings – was a constant and always a difficult pursuit. While I sometimes saw Mwaura’s university education as evidence that the family was aspiring to a type of middle-class status, I could not help but notice how it stretched their finances to the limit.Footnote 3 Neither was the burden of providing Mwaura’s school fees limited to Kimani. In April and May 2017, Catherine took work for local aspirant politicians vying in the elections to bring in extra cash for his and Njoki’s fees.Footnote 4 She spent weekdays going door-to-door attempting to persuade people to vote for whichever aspirant figure she was working for at that particular moment. Aside from the campaign wages, Catherine also found cash for household items through her participation in rotating credit groups, dubbed kĩama (sing., ciama pl.), something she was only able to do because of my arrival and the nominal cash that I paid every month to ‘rent’ Mwaura’s keja at the family homestead. Catherine was also in borrowing relationships with certain close friends, as I shall go on to discuss shortly.

Catherine often reiterated her hopes for Mwaura to find work after graduation with ‘God’s help’. That Catherine invoked God’s assistance when describing these hopes to me spoke to their precarity. Joblessness amongst university graduates in Kenya is widespread, as is youth unemployment more generally. Such knowledge could not have escaped Catherine, who likely understood that even with university education, Mwaura’s future would be highly contingent upon the relationships he could strike up with those in a position to offer him work, much as he had begun to do in Kitui with a government office running municipal waste disposal. Family jokes about Mwaura having the brains to become the local Member of County AssemblyFootnote 5 did little to conceal widespread knowledge about the very real challenges that would await him after graduation. Mwaura himself anticipated that his driving licence might prove more useful than his bachelor’s degree, and he anticipated a life driving pickup trucks and transporting produce for local farmers more readily than one involving office work in Nairobi – the preserve of those ‘who know someone’.

Mama Nyambura, on the other hand, embodied a greater degree of economic stability, status, and capacity to aspire than was possible for Catherine. By the time I arrived in Ituura in 2017, her eldest daughter, Nyambura (twenty-four), had spent most of the past two years in China, where she worked teaching children at a nursery school. As I note towards the end of this chapter, the nature of this work was usually left quite ambiguous by Nyambura, a sign that she did not want either me nor Mwaura to know much more about her experiences and life in China. Nonetheless, I came to understand that this was a job that allowed her to send some modest remittances back to her mother. Mama Nyambura also had her paid job working for a dairy company’s kiosk based in Ruaka Town, and rumour had it that she regularly appropriated canisters of milk that she would sell herself for a not insignificant 3,500 KSh. With her younger daughter, Shiko (eighteen), attending college in Nairobi (at a rather more affordable cost than Mwaura’s at his university), Mama Nyambura had far fewer outgoings than Catherine’s household, and many more streams of income to boot.

However, there is also another important contextual difference between Mama Nyambura and Catherine that I have not yet mentioned. While Catherine married into the neighbourhood, Mama Nyambura was the daughter of a neighbourhood notable, the late Njohi. It is worth recounting the significance of this briefly, since it sheds light on how different economic fortunes experienced by neighbours were the partial product of events that took place in the previous generation.

Mama Nyambura had become pregnant with her eldest daughter Nyambura when she was a teenager but had ultimately never married. Mama Nyambura had raised both of her children as a single mother in her parents’ home. As is becoming common practice in many parts of Kiambu and central Kenya more broadly, her father later encouraged her to build her own house on land held in his name (Chapter 6). Despite the aforementioned phenomenon of dwindling plots in Kiambu County (Chapter 1), Njohi was in a strong position to apportion land for his unmarried daughter. Having worked in his youth to find wages to support the education of his younger siblings, he had claimed the lion’s share of his father’s land at the time of inheritance. Though his younger brothers were jealous, Njohi’s word had stood, and he ultimately sold a piece of his (now moderately large for Kiambu) shamba to generate money to spend on construction materials. Njohi also made his money, and had earned his nick-name (and some notoriety), through his business exploits: brewing and selling what today are referred to as ‘illicit brews’.Footnote 6 Njohi had opened a ‘club’ (kĩrabu) in Chungwa, where he sold what he had brewed, making him a small fortune, and he acquired four pickup trucks that he used to transport crops and water locally. One of my neighbours once put it this way: ‘When I was small, he was the richest guy I knew.’ Over time, these vehicles were sold off. Njohi’s family wealth might have paled in comparison to members of Nairobi’s nouveaux riches who were now buying plots of land in Ituura and elsewhere in peri-urban Kiambu for the construction of rather large two-storey homes with tiled roofing. Njohi and his wife wa Njuki had lived in one-storey concrete buildings with corrugated iron roofs. But in the context of Ituura, theirs had earned a reputation as a wealthy family. It was partly based on this inherited wealth that Mama Nyambura had been able to invest in the construction of a stone house, and in 2018, she had also built a small row of one-storey concrete apartments that she intended to let out (Chapter 6).

Most notable of all, Mama Nyambura’s one-floor stone house with tiled roofing stood in stark contrast to Catherine’s wooden house, with its earth floor and mabati (corrugated iron sheeting) roof, as did her flat-screen television and leather sofas. ‘I think this house is amazing’, Mwaura once told me on one of our visits there. Catherine’s house, meanwhile, was built on land that belonged to her sister-in-law. Kimani’s stone house remained unfinished, delayed by the economic slow-down caused by the 2017 elections and the need to prioritise Mwaura’s university fees. During the rainy season, water would flow from the hill above, sometimes flooding the floor of Kimani’s small house. ‘Our house is shit!’, swore Mwaura on one of the occasions when the house suddenly filled with water, jeopardising the electrics. On another occasion during the 2018 rainy season, I sat in the darkness of the house with Catherine and her daughter Njeri with the mud floor covered in puddles, the power out. ‘God will bless us’, Catherine insisted. ‘This year, we will be in that house ya mawe’ (of stone).

The distinctions in dwelling laid bare the differing fortunes of the two friends. But despite their different economic circumstances, Mama Nyambura and Catherine would regularly take turns assisting with household labour at each other’s houses, often cooking together at weekends for each other’s guests (ageni). As I have mentioned, female friendships in Ituura were characterised by such acts of material assistance – sharing household items and foodstuffs (fermented porridge, for instance) but also via household-based labour. These acts of assistance often took place during moments of dire need. Catherine fell badly ill in late 2017, an illness that lasted until mid-2018. Doctors suspected tuberculosis.Footnote 7 Women from neighbouring households often volunteered their own labour at weekends to help Catherine cook and clean. With little in the way of amenities beyond perhaps a gas stove for cooking and water tanks, practically all household labour was done by hand. The process of making meals sometimes took hours. Throughout my fieldwork, Mama Nyambura would often arrive at the homestead early on a Saturday or Sunday with her younger daughter Shiko, who would dutifully peel potatoes while her mother chatted with Catherine. Shiko rarely seemed irked by having to give up her Sunday, and as long as the music being played on Catherine’s radio was more or less contemporary (Ghetto Radio’s reggae music, for instance), then all was well. Nyambura often joined us too, and Mwaura and I would sometimes ask her about her time living in China, to little avail.

However, in early 2017, before Catherine had fallen ill, something happened that completely transformed my impression of this friendship, as it did the impressions of it held by the two friends themselves and their wider families.

One evening in mid-March 2017, after returning from a language class in Nairobi, Catherine and Mwaura relayed to me the news that Nyambura had suddenly returned to China the previous night. Mama Nyambura and Shiko had escorted Nyambura to the airport without any hint of a goodbye. Along with Catherine and Mwaura, I too was rather taken aback since I had considered her one of my first friends in the area. Catherine was particularly bemused.

I asked Mama Nyambura, ‘How is Nyambura? Peter has been texting her.’ She says, ‘Oh, Nyambura has returned to China.’ I said, ‘What!?’

In her usual style, Catherine finished her story with an invitation to ‘Imagine!’ Mwaura filled in the blanks. ‘They think we are jealous of them. They think we might try to stop her going back to China somehow.’ Mwaura’s implication – as I found out at a later stage in my fieldwork – was of the ‘crazy’ things people are said to do when animated by jealousy (ũiru). ‘You’re assuming that’, I told him. But he was certain. ‘What else can it be?’ Catherine continued with her tone of surprise. ‘Weh! Imagine!’ ‘I thought they were like our best friends here’, I said, perplexed. ‘Me too’, said Mwaura. ‘I thought they were cool with us.’

Socio-economic Stratification and the Politics of Moral Obligation

Nyambura’s shock departure to China was an early instance in my fieldwork of what Sally Falk Moore calls a ‘diagnostic event’, an occurrence ‘that reveals ongoing contests and conflicts and competitions and the efforts to prevent, suppress, or repress these’ (Reference Moore1987: 730) – an opportunity to find out ‘what’s really going on’, and ‘what people are saying about it’ (ibid.). My initial impressions of a seamless friendship between Mama Nyambura and Catherine were shattered, and the tensions they had concealed brought into view. The socio-economic distinction between the two families – one embodied by their children’s differing fortunes – was laid bare, the expectation of jealousy evoked.

The episode revealed to me the burden of expectation Mwaura and Catherine might have had on Mama Nyambura, ones that the latter sought to avoid. Back in 2017, Mwaura himself had particular hopes. ‘They think he will bother them’, Catherine had said on the evening after Nyambura’s self-disappearance to China. As Mwaura saw it, Nyambura had as good as guaranteed him a job at the carwash she managed in the nearby town of Ndenderu. Mwaura had spent three months from January to March waiting and waiting, but the opportunity never came.

It is not difficult to understand that Nyambura and her mother might have felt concerned about Mwaura’s expectations for assistance from them specifically. In 2019, Jata, the twenty-three-year-old daughter of a neighbouring family and Mwaura’s friend, speculated that Nyambura and her mother had given ‘false hope’ to Mwaura about the promise of work.

For Catherine and Mwaura, the idea that they had been painted as needy and potentially jealous made them rethink their friendship, and their general dispositions in the neighbourhood. ‘I gave them everything’, Catherine told me the night we found out, mirthful despite the surprise.

I told them this, this. Now I will keep my things close. Peter, keep your things close – angalia mambo yako.

Catherine’s advice to ‘take care of your own issues’, not to share them with others unduly, was a piece of pragmatism forged in neighbourhoods like Ituura where knowledge is power. To know things about others is to have the capacity to generate a certain impression of them in wider circles of ‘gossip’ (mũcene) to which they are not always privy. Catherine extended her advice to Mwaura especially, impressing upon her son the need to conceal his job struggles from others, not to reveal to potential helpers that he might possess expectations for economic assistance:

She was telling me that’s a very good lesson to me because for me apparently, I love telling people a lot of stuff. So she was like ‘that’s a lesson to show you that people don’t tell you their stuff’. You’re the one telling them your stuff, unnecessary stuff. So she was like ‘Always keep quiet. Stop telling people everything.’

Mwaura told me later that he had shared his ‘everything’ with Nyambura and her mother – his struggles ‘hustling’, his hopes and dreams.

The disappointment Mwaura felt was paralleled in his suspicion of Nyambura’s blatant silence, as he saw it, about her work in China. Mwaura was offended by Nyambura’s withholding of knowledge from him and, by implication, of the opportunity she had enjoyed. The ambiguity she created about her work there, he felt, was a product of deliberate secrecy (compare Desplat Reference Desplat2018; Archambault Reference Archambault2017) designed to ward off any attempts by himself to find a similar opportunity to go to China and earn money. For Mwaura, it was clear why Mama Nyambura would not help him. ‘She knows I’ll make something out of myself, and maybe I can be better than them.’

Envy, Avoidance, and Refusal

Despite the female friendships that characterised Ituura, the same families were also competing in the neighbourhood for status and prestige within a socially and economically stratified landscape that places immense value upon material prosperity. ‘People care about what you have’, Mwaura would later remark in 2022. People in Ituura may have seen salaried office workers who were moving into the new gated communities of their peri-urban periphery as members of an economically stable ‘working class’.Footnote 8 However, amongst themselves, they were more likely to speak of those who were ‘progressing’ or ‘progressing themselves’ in English, or ‘going ahead’ (guthiĩ na mbere) in Kikuyu. Such impressions were gauged through the visible signs of economic success, such as building a brick house or purchasing a car, signalling that one had ‘made it’ (kuomoka) to middle-class status.

The way these aspirations played out in Ituura’s social networks recall what Peter Geschiere (Reference Geschiere2013: 82) has called a ‘competitive egalitarianism’. In his ethnography of the Cameroonian Grassfields, he described the ‘ostentatious show of ambition and personal striving for supremacy’ (Geschiere Reference Geschiere2013: 82). These are the types of ‘envy’ micro-politics that anthropologists have observed in localised settings throughout Africa and beyond, and which recall Foster’s (Reference Foster1972) description of envy as a product of the sorts of zero-sum politics typical of localised contexts defined by notions of ‘limited good’ – that there was only so much prosperity to go around, and which shape anxious attempts to display and covet material wealth. Building on Foster, David Graeber (Reference Graeber2007: 85–6) wrote in his ethnography of village life in Madagascar that some of his interlocutors possessed ‘a desire to arouse feelings of envy in others’. Within the status politics of Betafo village, Graeber argued that the will to project wealth and power over others was itself ‘a driving force behind the desire to accumulate’. To a degree, these observations of village life can help us understand the social dynamics of aspiration in a neighbourhood context like Ituura, a setting where household-based ‘progress’ is visible and demarcated but then becomes a source of ‘social comparison’ (Desplat Reference Desplat2018). In Chapter 6 we will see how building rental plots has become a new site of ‘envy’ between Ituura’s upwardly mobile families.

As we have seen in the case of Mwaura, when the success of others is palpably apprehended, desires for one’s own ‘progress’ manifest not so much as a wish for power and status – to be envied by others – but rather a desperate bid not to be left behind, to be excluded from the middle-class futures of the life projects of ‘well up’ families. Deborah James has discussed similar practices of ‘status competition’ (Reference James2014: 45) amongst the middle class of South Africa. Her interlocutors note the tendency for families to emulate each other’s’ projects. As James notes, notions of jealousy and envy may not be the right terms for such competitive acquisitiveness, but ‘something more like “keeping up with the Joneses” than striving to surpass them’ (James Reference James2014: 46). As she notes, negative feelings are never too far away, especially when one feels one is being left behind – experiencing the shame of failing where one’s relatives and friends succeed.

In Ituura, the wealth of others regularly provoked shame and despair. As we saw in the opening of the chapter, young men make keen comparisons between themselves and others who appear to be going on towards better things. Mama Nyambura’s house was a reminder to Mwaura about his family’s failures, especially those of Kimani. Kimani himself was said to be particularly jealous of another local woman who had constructed a stone house on land sold by one of Kimani’s half-brothers from his own father’s second wife. As Mwaura explained,

That woman was, before she built that house my dad used to be her very good friend. Then after she built the house, he doesn’t even talk to her anymore. He doesn’t like … [PL: Is that coming from her or your dad?] From my dad. She’s very cool with us but my dad doesn’t talk to her. [It’s because] she’s made it … He’s very bitter against her and they’ve never done anything against us. He even says she’s a prostitute, that the men who get along with her are the ones building the house for her. And man, it’s not good. Because her children are in China. One of her daughters is in China, the other is in Dubai.

Such self-other comparisons informed the type of abjection we observed amongst young men in Chapter 2 – the sense of being ‘outside’ the prospering circles of Nairobi.

However, as Geoffrey Hughes (Reference Hughes2020) has noted, anthropological accounts of envy often follow the voices of those who claim to be envied. In this vein, we can observe how envy discourse can serve to justify certain ends – in this case, forms of secrecy and avoidance within social networks (Desplat Reference Desplat2018: S127–30; Archambault Reference Archambault2017: 19–22). Rather than an actually existing politics, envy emerges here as a narrative spun by the upwardly mobile about the desires of others to deprive them of their success, and a recognition of its precarity (Lockwood Reference Lockwood2023b). While Mwaura and his family compared themselves to others progressing ahead of them, others in Ituura who saw themselves as more successful than their neighbours described the ‘envy’ or ‘jealousy’ in English that they anticipated from their peers and relatives. These anxieties informed their desires to separate themselves from the neighbourhood of Ituura and its residents.

Lee was a twenty-four-year-old bank employee who had spent most of his life living in Ituura before moving to Chungwa Town at the age of twenty-two. As a member of the Star Boyz football team, Lee often remarked upon the tensions between himself and his teammates produced by the status he projected. Lee often wore office clothes, and his teammates knew that he had a consistent income from his job working at a bank in Nairobi. However, Lee felt these tensions with his friends were relatively benign compared to those he experienced amongst his relatives and neighbours in Ituura.

People don’t want to see you going ahead more than them. If my sister is doing well, and my mum praises her, starts to see her as more useful than me, that jealous feeling will start that maybe I can do something bad to my sister.

Lee characterised Ituura as a place of ‘jealousy’, where he struggled to meet expectations placed upon him by others. Speaking to him on the return trip from football training in 2018, he remarked how he preferred to ‘live privately’ in Chungwa. ‘I don’t tell people about myself, where I work, what I do. I lie to people. I lie a lot.’ Lee evoked the requests for material assistance he anticipated from others, that he would be bled dry by constant requests for cash. He claimed that if he found even greater success, he would leave Kenya instantly.

In a similar regard to Lee, Mama Nyambura’s active avoidance of Catherine’s household shows what types of tensions arise from a context that is both competitive – in terms of ‘progress’ – and socially and economically stratified. In this context, ideas of personal effort justify economic withdrawal and the right to delimit obligation.Footnote 9 We have already seen how senior men from Ituura preached a labour theory of virtue, arguing that work could lead to wealth, a thinly veiled criticism of the young men they characterised as ‘idlers’ (Chapter 1). Amongst the hedgerows of Ituura, such ideas also shape practices of providing economic assistance to others, delimiting it by asserting the individual right to the fruits of one’s ‘hustling’ work in the informal economy, given the effort of generating it in the first place. I was reminded of such perspectives one day in 2017, travelling to the formidable Two Rivers shopping mall with Feye, the twenty-six-year-old daughter of one of our neighbouring families. We took a matatu from Chungwa’s main thoroughfare, stopping in Ruaka, where I spotted the rare sight of a female makanga ushering passengers into a matatu. ‘She must hustle for herself’, Feye said, praising her perseverance in a male-dominated line of work. Feye contrasted the morality of such labour with the idleness of her elder brother Ikinya, who we met in Chapter 2, a man who had entered his early thirties in a state of alcoholism, sometimes relying on his elder brother Gethi for cash. Recall that Gethi called his own money ‘my sweat’ (thithino yakwa), a common epithet used in moral discourses about money to indicate rightful ownership of the money one makes, and the limited nature of the claims others might make upon it.

For Africanist anthropologists, such tensions between individual aspiration and material obligations famously reared their head with the widespread embedding of Pentecostal Christianity and its associated ideas in African Christianity from the 1980s onwards. Birgit Meyer (1998) observed ‘its popularity among people who are involved in a struggle to close themselves off from kin’ (Reference Meyer1998: 336). ‘[W]hile the poor make claims for family assistance’, Meyer wrote, ‘the more affluent try to eschew obligations associated with the extended family and claim that in modern times one can only take care of one’s immediate’ (Reference Meyer1998: 336). Meyer was careful not to associate this tendency too closely with Pentecostal Christianity, and this is important. Pentecostal Christianity was not in and of itself the ideological trigger for narrowing relations of obligation but complemented wider processes that were already stretching and fraying kinship ties, not least migration to the city and the relative access to wealth that brought. In other words, social stratification in Ghana was already turning ‘kin into strangers’, as Pauline Peters has put it (Reference Peters2002).

Across Nairobi and its metropolitan environs like Kiambu, this process of dislocation is driven by a powerful labour ethic that celebrates people who are seen to have ‘hustled for themselves’ (kujihustle) or ‘planned for themselves’ (kujipanga), notions that implicate personal effort and competence (Lockwood Reference Lockwood2023a). The popularity of rags to riches stories that circulate in the Kenyan media is a case in point (The Standard 2018). From the perspective of the successful, their wealth is an index of their effort, masking any advantages they may have had in accumulating it. Gĩkũyũ-language gospel music celebrates ‘the work of hands’ (wĩra wa moko), characteristic of the informal economy, but also scorns the ‘grasshopper mentality’ (ũdahi) of those who fail to pursue their dreams and ‘success’ (ũhotani).Footnote 10

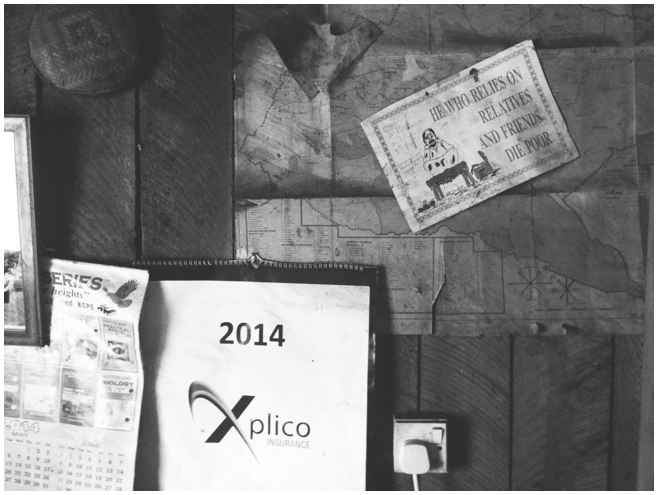

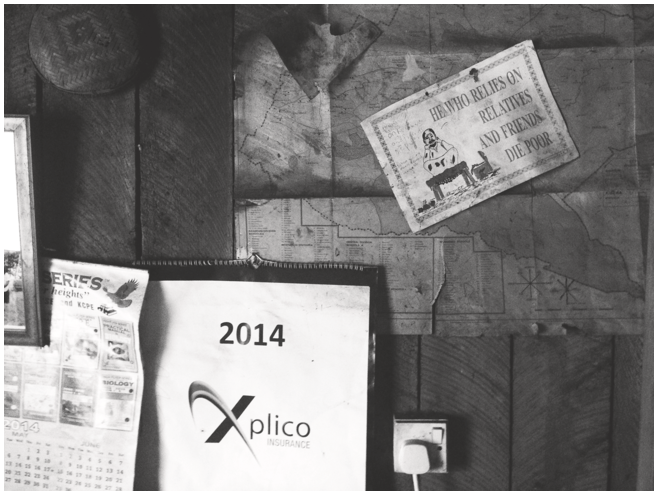

These ideas are central within what we might call Kenya’s ‘popular economy’ (Hull and James Reference Hull and James2012), the public terrain – of songs, television shows, and everyday speech acts – where notions of proper economic conduct prevail, circulate, and are held up to scrutiny (Figure 4.1). Such ideas can be articulated at the road-side, as we saw with Feye, or in high-political rhetoric. Uhuru Kenyatta’s Jubilee Party, in the vein of his father’s post-independence government, praised youth who were seen to have adopted an entrepreneurial spirit in response to economic hardship,

I am encouraged by the much larger number of our youth who are working hard, who are hustling, and who approach challenges as an opportunity to overcome. You are uplifting your families, your communities, and our nation.

Figure 4.1 Proverbial wisdom on the wall of Kimani’s home

Figure 4.1Long description

The wall of a Kiambu homestead, its wooden panelling covered by an unseen photograph and a calendar, as well as a map. On top of the map, there is a picture of a line-drawn man crying, his situation evidently poor and destitute. Next to him the text reads in English 'He who relies on relatives and friends die poor'.

This popular labour ethic has had a major ideological role in the ‘responsibilisation’ (Butler and Athanasiou Reference Butler and Athanasiou2013) of Kenyans, allowing the state to shirk its responsibilities for economic and social welfare, passing them on to citizens (cf. Dolan and Rajak Reference Dolan and Rajak2018; Njoya Reference Njoya2020).

Such discourses recall the concept of ‘hustling’, which was used by a number of my interlocutors and has recently been taken up by scholars like Tatiana Thieme, Meghan Ference, and Naomi van Stapele (Reference van Stapele2021) to evoke the resilience of Kenya’s informal economy workers. In their hands, ‘hustling’ emerges as a concept that celebrates the determination of the poor to resist the circumstances of their political and economic marginalisation. But as we have seen, such concepts are also prone to political deployment, not only by mainstream political forces (see Lockwood Reference Lockwood2023c), but in everyday life, where notions of ‘hustling for yourself’ invoke a spirit of determination that is mobilised to delimit economic obligations. The competitive environment of Kenya’s popular economy encourages people to pursue success for themselves while casting off obligations to extended family members, neighbours, and peers. The question remains, however: how do poorer families go about seeking economic assistance from the apparently successful when the labour ethic prevails?

Aspiration and the Atmosphere of Civility

In his work on the Cameroonian Grassfields, Geschiere (Reference Geschiere2013: 94–100) suggested that witchcraft accusations were a response to what he called the ‘end’ of ‘just redistribution’ – the idea that the country’s urbane and upwardly mobile nouveau riche would not share its prosperity with poorer neighbours upon return to the natal village. Witchcraft accusations were, he suggested, a ‘reminder’ to the wealthy that they ought to share but also a backlash against the anti-social rich. In Ituura, attacks upon the economically prosperous were hardly unheard of. Early on in my fieldwork, I was told of a local farmer who had constructed a well on his land, only to find a donkey carcass had been thrown into it a few days later.

However, if fears of envious acts persist, outright acts of destruction are rather extreme and rare responses to such refusals and avoidances. Rather than resort to attack, poorer families recognise the limits that the labour ethic places on their capacity to solicit economic assistance. Knowing this, they bide their time. Repertoires of knowledge have emerged emphasising the need to ‘keep quiet’, to develop relationships with the locally wealthy while concealing economic need. As James Ferguson (Reference Ferguson2021) has noted in his more recent work, presence is critical to generating feelings of obligation, and it is by generating intimacy through presence that poor families attempt to ‘break down’ the fledgling boundaries of emerging class closure. Thomas Widlok (Reference Widlok2013: 20–2) has also argued that the sharing of wealth hinges upon co-presence, the situational grounds for recognising the needs of others. But concealing need is critical here since its open display regularly encourages the wealthy to retreat into outright avoidance. Stopping wealthy friends from withdrawing is a vital tactic in the maintenance of possibility – that those relationships will be made productive, in the future, at least. Such tactics evoke the practices of ‘caring for relationships’, described by Tom Neumark (Reference Neumark2017), where avoiding the overburdening of others was a way of keeping these networks open for future moments of assistance if crisis were to strike. But beyond caring alone, these tactics operate as a mode of ‘civility’ (Whyte and Siu Reference Whyte, Siu, Cooper and Pratten2015), a watchfulness for opportunity, that saw Ituura residents draw closer to those deemed capable of helping.

An immediate example of this took place in 2018, when, one evening after football training while resting in my keja, Roy texted me asking me to meet him on a road that cuts through the back of Ituura. Despite my questions as to why, he simply insisted I come to the road. I walked out to meet him, only to find there waiting with him Wanjonyi, the twenty-seven-year-old captain of our team. Roy asked me if I would lend 1,000 KSh to Wanjonyi, himself recently a new father and in urgent need of cash. Wanjonyi remained quiet, and it became apparent that Roy was positioning himself as something of a broker on his friend’s behalf. I was willing to oblige, but it is the strategy that interests me here. Roy was careful not to state the precise purpose of the meeting until I was on the street standing next to him and Wanjonyi. When put in such a position, one cannot easily decline without losing face, and if the anthropologist might be able to provide support with relative ease, these were the sorts of claims and requests that wealthier people avoided, knowing that refusals might lead to bitter feelings of resentment.

When sourcing money for aspirational projects, poor families do exactly as Roy did the night he approached me on Wanyonyi’s behalf – but over the longer term. As we have seen, Ituura is a place where one observes what Jane Guyer calls a ‘social gradient’ (Reference Guyer2004: 147) – where fine-grain distinctions are made between who is successful and who is not. People spoke of the distinct ‘levels’ residents had ‘reached’ (gũkinyĩra) in terms of wealth and prosperity. These levels were also seen as leading to the type of delimiting and distancing that we have already observed. Consider the words of Jata here, who became one of my key interlocutors from 2018 onwards, as we increasingly reflected upon the nature of life in Ituura. We had been discussing my suggestion that ‘proud’ people disassociate themselves from the poor, and she explained that,

To prosper, someone has probably worked hard, had a plan and particular goals. But before that success, they were associating with people of the same level, maybe with the same aspirations. Prosperity means that goals and aspirations change which in most cases means a change of people we associate with, places we hang out, and what we make time for. People expect you to remain the same, but that’s not possible. This change, unavailability might be interpreted as pride but it’s just a change of priorities.

Jata’s words remind us that Ituura’s upwardly mobile families possess their own valuable exchange networks, cultivated in contradistinction to others who are seen to lack the same aspirations and propriety. But they also speak to the possibilities of association itself – of the possibilities of actively and somewhat deceptively portraying oneself publicly to be ‘on a level’ with wealthier people in order to enter into their social circles.

Neighbourhood kinship rituals provide an important opportunity to obviate these distinctions. At burials (mathiko), for instance, neighbourhood women from a range of backgrounds come together to volunteer their labour and presence to assist with a variety of household tasks such as cooking food for the young men who dig the grave (kwenja irima) the day before the burial. At such kinship rituals, poorer families can participate in ways that signal their success, yet drawing closer to potential patrons. Gifts of cash to the bereaved are essential to this performance of status – giving an amount that meets the financial expectations elicited by one’s outward projection of economic success. In this way, the practice of civility engages a ‘politics of pretence’, to use Archambault’s (Reference Archambault2018: 8) term, demonstrating that one’s household is not going awry.

Under the cover of civility at these events, Catherine was able to form new friendships based on her careful discernment of possible avenues of future help. Consider her friendship with Mama Janice, another neighbourhood mother who stepped into the breach vacated by Wa Njambi in 2018. A widow in her mid-forties, Mama Janice benefited from the pension of her late husband, and had a fine stone house in Ituura, where she lived with her two small daughters. Mwaura and I had often visited Mama Janice’s while we were performing one of our typical neighbourhood chores, collecting household vegetable waste to feed to his pigs. Mwaura always spent time talking to Mama Janice, played with her youngest daughter Ann, and generally maintained a friendly and open disposition at her place.

In the midst of a later panic to source money for Mwaura’s fees in 2018, Catherine approached Mama Janice to ask for a loan. By then, Catherine’s money troubles had been broadcast in neighbourhood gossip. Mama Janice likely knew of Catherine’s struggles, and probably knew that she might be asked for help in the future. Nonetheless, Catherine was required to save face by stressing the one-time nature of the request, pointing out that Mwaura was almost through with his university studies, almost able to stand on his own two feet. Mwaura had employed the same logic months earlier when giving his aforementioned ‘sad story’ to Nyambura. He had stressed that the money he was asking for would allow him to finish university and become economically independent. He even suggested to Nyambura that it would be he who repaid the loan, rather than his parents, a statement of his future autonomy, his almost-independence, and a deliberate performance of his non-dependence on his socially mobile friends.

The groundwork for the friendship with Mama Janice had been laid over the previous year, and a sharing ethos between the two households had been slowly created, one I was drawn into as a fictive member of the poorer family. Mwaura once encouraged me to take Mama Janice a socket extension bought in nearby Chungwa Town to help her install her television – my gift standing for that of the whole family. Later in March 2018, Catherine, Mwaura, and I attended the birthday of one of Mama Janice’s young daughters, celebrating with cake and Gĩkũyũ-language gospel songs at their house. As Mwaura himself remarked, his mother cultivated the friendship knowing she might need Mama Janice’s help ‘in case she had a money emergency’. Civility established, Catherine was able to reveal her need as a one-off request for assistance, telling Mama Janice how well Mwaura was doing at school, and that she only lacked the money because Kimani’s truck was damaged.

Emphasising the interested or conscious aspect of relation-making should not detract from an appreciation of the genuine social membership achieved through participation in such groups, membership that transcends interest alone. Throughout 2017 and 2018, Catherine’s caring for others opened up new avenues of economic support. In 2017, Catherine first began to form a strong friendship with Feye and her twenty-seven-year-old sister-in-law Mary. In time, Catherine, Mary, Feye, and their mother, Mama Gethi, formed a kĩama – a name loosely applied to women’s rotating credit groups or other business ventures pursued in groups – and purchased a tent that they planned to hire out for burials, weddings, and other neighbourhood events. At the heart of the relationship between the two families was Catherine’s friendship with the younger Feye, an unmarried daughter of a nearby neighbourhood. Catherine always joked with Feye about her boyfriends, playing an aunt-like role in the younger woman’s life, advising her to be patient and discerning when it came to selecting a husband.

The prevailing atmosphere of civility in Ituura allows women from distinct backgrounds to associate together through shared aesthetics, and implicit and explicit valuation of independence and respectability, alongside participation in such caring relationships. Participation in neighbourhood life along these lines widened Catherine’s ability to diversify her income streams. Catherine was, I should mention, fairly popular and well-known in the neighbourhood. She had cultivated a friendly relationship with the local chief in anticipation of acquiring paid work conducting local administrative tasks. When I began my fieldwork, Catherine already had a job as a community health worker for a hospital in Chungwa Town, even though it only brought in a few hundred shillings a week. ‘I walk with big people’, she once told me in a joking manner, all too aware of her family’s constant economic struggle.

The Limits of Civility and the Life of a Hustler

Practices of civility had the potential to obfuscate socio-economic distinctions, but neither inevitably nor permanently. Consider, for instance, the fate of Catherine’s family into 2018 as flooding and illness blighted the family. Catherine and Mwaura both suffered from bad chest infections brought about by the shift to the rainy season, and the former experienced a prolonged illness. It was then that the house flooded, and Mwaura’s impatience with his father Kimani’s lack of income grew. As Catherine’s health deteriorated, neighbours gossiped that she was suffering from HIV. All of this was confirmation that they were not on the same ‘level’ as families like Mama Nyambura’s.

In the midst of these events, Catherine and Mwaura were forced to ask for money from Mama Nyambura. In 2018, Mwaura required around 50,000 KSh to sit his university exams. Without them, he would not be able to graduate, and would find himself waiting a whole year to sit them again.

By this point, Mama Nyambura and Catherine had patched up their friendship. The precise circumstances were unknown to me, but when Nyambura eventually returned from China again in 2018, she spent time at Catherine’s homestead with her mother as if nothing had happened, exchanging ‘stories’ and gossip from the neighbourhood as they did before. Nyambura went back to China again in 2018, and afterwards, Catherine proudly showed me the photographs on her smartphone of her visiting the airport in their company. This time she had been included. Civility had been restored.

I paid half of the fees, and Mwaura tried to acquire the other half from Nyambura via a loan to be paid back once his father’s work resumed. At 25,000 KSh, this was hardly an unsubstantial sum of money, and Nyambura was initially very reluctant to give Mwaura the cash. Eventually she was won around by his ‘sincere story’, as he put it, that without it, he would not be able to graduate. But she insisted upon prompt repayment. Kimani’s work resumed shortly afterwards, and Nyambura was repaid in a mere three weeks.

As Jane Guyer notes, ‘shortages always throw categories of person into relief’ (Reference Guyer2004: 106). The pretence to middle-class status afforded by the engagement in the neighbourhood’s wider social life was punctured by contingent misfortune. Catherine’s family’s hardship revealed to Nyambura their precarity and, as such, they could barely be trusted to repay the loan. The relationship between the families became distant once more. Nyambura in particular made far fewer appearances at Catherine’s homestead. Civility’s assumption of equality could not encompass the enormity of Catherine’s request. While the two families eventually patched up their friendship in mid-2018, it continued to involve resentment and rebuttals. In 2020, not long before Catherine’s unexpected death, Mwaura had been trying to solicit Nyambura’s help to find work in China. Having graduated from university in 2019 and then becoming a young father in 2020, Mwaura was on the lookout for new opportunities, and he reasoned that Nyambura should have been able to help him, that his need was self-evident. Her constant rebuffs only created further resentment. ‘She was like, “There are no jobs there, there are no connections.” And I was like, “Help a brother out!”’ It was clear that Mwaura felt their closeness – the proximity established throughout 2017 – ought to have made them receptive to his claims. Years later, in 2022, reflecting upon the events in the run-up to Catherine’s death, Mwaura speculated that Mama Nyambura had taken advantage of the closeness between the families, spreading the news in the neighbourhood that Catherine was ‘broke’.

Catherine once glossed her friendship with Mama Nyambura as one of ‘love’. We were chatting one day after I had returned from Kitui, where I had spent a few days visiting Mwaura and hanging out with his friends at his university. Speaking of Mwaura and one of his friends, Catherine praised the mutual assistance that defined their friendship – its true sign. ‘They love each other. When Mwaura don’t have, Cosmas helps him. When I have, you help me. When you don’t have, I help you. Sindiyo, Peter?’ Catherine went on, ‘Mama Nyambura, we help each other … And she is rich!’ There were other people, Catherine insisted, who would not help you when down. It recognised the mercy of Mama Nyambura, but also the precarity of the relationship. Catherine emphasised the power of affection to keep such relationships open, but there was no reason to automatically expect the rich to help the poor.

The sheer difficulty of finding permanent relations with dependent, reliable providers meant that Catherine continued to diversify her income streams, maintaining (as best she could) a ‘spread … of diverse modes of getting by’ (Ferguson Reference Ferguson1999: 20) that she could switch between as necessary. Like other Kiambu women who ‘hustle’ in search of cash, the lifeblood of social reproduction and mobility, Catherine knew the futility of repeatedly relying on the same friends and relatives. It was this realisation that drove her into the local informal economy, working for politicians during the 2017 elections, and making soap to sell to the local church. Work outside of social relationships remained a means to avoid the uncertainties of the social relationships themselves.

In those final years of illness, Catherine’s struggles and stresses left their mark on her health. Mwaura himself only belatedly realised the full extent to which Catherine had suffered for his future. A young graduate and now new father, lacking Catherine’s social networks, in 2021, he found himself increasingly alone. ‘When I tell you it’s hard over here, man, I mean it’s fucking hard. Everyone is relying on me now.’

Conclusion

This chapter has shed light upon the challenges of sourcing money for projects of social mobility (especially school fees) within the context of a socially and economically stratified neighbourhood where powerful ideas of economic independence and success circulate. In this context, the core arguments of recent Africanist scholarship about the embedded tendency towards ‘dependence’ looks rather less sure. Instead of a desired or durable state, dependencies are contingent, the product of caring labour and strategies of creating civil relationships. They are hardly immune to economic stress. In 2018, the precarity and illness that blighted Catherine’s household revealed what Ruth Prince (Reference Prince2023) after Lauren Berlant (Reference Berlant2011) has described as the ‘cruel’ aspect of possessing hopes for social mobility in the Kenyan context – their vulnerability to economic shocks in a context where there little to no state-based social security.

Catherine’s labours of care and her ‘hustling’ in the neighbourhood responded to this fundamental precarity, underscoring the failure of male wages. To Mwaura, his mother’s struggles compounded his sense that his family were lagging behind others in the neighbourhood and practically falling into destitution. Revisiting these events through discussions with Mwaura in 2022 reiterated Catherine’s struggles in those years of my doctoral fieldwork. In his view, it was not so much men who were providing for their households, but women. ‘It’s our mums who are putting together money’, he remarked. With Kimani away, and practically broke himself, it had fallen to Catherine to navigate neighbourhood micro-politics, to face the challenge of finding providers under conditions of economic duress. In an economy of cash scarcity, few households were able to act as reliable patrons, leaving Mwaura and his mother few places to turn. As we will see in Chapter 7, Mwaura’s fate after Catherine’s death revealed the extent to which her social networks had underpinned the household’s stability in 2017 and 2018. Bereft of the same social membership, Mwaura would find himself hustling in the informal economy, resentful of his extended family who he maligned as ‘useless’, rendering him alone and facing an uncertain future.