Introduction

A central issue during the coronavirus crisis is citizen trust in government institutions (van der Meer & Zmerli Reference van der Meer and Zmerli2017) and in unknown others (interpersonal trust) (Uslaner Reference Uslaner2018). Trust in a government's good intentions and capacity to act will foster willing compliance with regulations to limit negative effects of the pandemic (Levi & Stoker Reference Levi and Stoker2000; Siegrist & Zingg Reference Siegrist and Zingg2014; Taylor et al. Reference Taylor, Raphael, Barr, Agho, Stevens and Jorm2009). Correspondingly, trust in that fellow citizens will act responsibly improve the chances of solving problems of collective action, such as the hoarding of groceries (Chaudhuri Reference Chaudhuri2011; Lunn et al. Reference Lunn, Belton, Lavin, McGowan, Timmons and Robertson2020; Ostrom et al. Reference Ostrom, Walker and Gardner1992). While the two types of trust are interrelated (Sønderskov & Dinesen Reference Sønderskov and Dinesen2016), they are distinct constructs that should be studied separately (Vallier Reference Vallier2019).

Countries entered the coronavirus crisis with a certain supply of institutional and interpersonal trust (Ortiz‐Ospina & Roser Reference Ortiz‐Ospina and Roser2020). That trust level, which varies substantially across the world, formed a baseline condition for crisis management. However, as with other supplies, citizen trust needs to be monitored and replenished during difficult times (Easton Reference Easton1975). To understand the social conditions required to fight the coronavirus and future pandemics, we need to learn if and how citizens update their trust attitudes in response to the dramatic events (Bauer Reference Bauer2015; Nicholls & Picou Reference Nicholls and Picou2013).

The present research investigates trust formation processes among the Swedish public as their country moved from the initial phase of the crisis to the acute phase of the crisis. Sweden is a critical case to study because the government strategy to curb the pandemic was less strict than in all other industrialized democracies (Petherick et al. Reference Petherick, Hale, Phillips and Webster2020).Footnote 1 In addition to highlighting the unique ‘Swedish experiment’, our study contributes by tracking updates of both types of trust attitudes of importance for fighting pandemics. This is different from most previous studies of trust formation during critical and dramatic events, which focus solely on institutional trust.

The Swedish approach to coronavirus crisis management relied more on voluntary cooperation from citizens than on the mandatory regulations imposed by other governments (Fund & Hay Reference Fund and Hay2020; Paterlini Reference Paterlini2020; Pierre Reference Pierre2020; Strang Reference Strang2020). A prerequisite for this approach is that Sweden entered the crisis with uniquely high levels of interpersonal trust and with high levels of institutional trust (Martinsson & Andersson Reference Martinsson and Andersson2019; Ortiz‐Ospina & Roser Reference Ortiz‐Ospina and Roser2020). At the same time, Sweden has in recent years polarized along the lines observed in many democracies with individuals to the right expressing lower levels of trust than individuals who self‐identify as centrist or leftist (Jylhä et al. Reference Jylhä, Rydgren and Strimling2019). Furthermore, in connection with the coronavirus crisis, credible experts and non‐political opinion leaders were calling on the government to introduce more stringent containment measures (Robertson Reference Robertson2020). Thus, there was a potential for dissenting voices during the critical weeks of March and April that we are studying.

We base our analysis on a large (n > 12,000) web‐survey panel with adult Swedes in which the same individuals were asked the same set of questions twice, at the initial phase of the crisis (t0), and at the acute phase of the crisis (t1). We also leverage that a subsample was interviewed a year before the crisis, in December 2018 (t 1).

Theory

In note Footnote 2 particularly difficult and dramatic times, such as after terrorist attacks and in wars, support for government institutions often increases. These effects are known as rally‐round‐the‐flag effects, or rally effects for short, because they tend to increase support for figures or institutions that are associated with the nation (Dinesen & Jæger Reference Dinesen and Jæger2013; Hetherington & Nelson Reference Hetherington and Nelson2003; Mueller Reference Mueller1970).

Scholars have provided multiple perspectives on the reasons for rally effects. One is inspired by social identity theory (Tajfel Reference Tajfel1982) and centers on national affiliation, where a crisis triggers support for symbols associated with the in‐group, such as the president. A second group of explanations focus more directly on the threat itself, where the rally effect is understood as a way to increase security in an unmoored situation (Doty et al. Reference Doty, Peterson and Winter1991). A third perspective is concerned with discrete emotions, primarily anger and anxiety, as potential mechanisms behind rally effects (Lambert et al. Reference Lambert, Schott and Scherer2011).

Yet another perspective suggests that political elites play an important role. For example, in an analysis of nearly 200 military disputes that involved the United States, Baker and Oneal (Reference Baker and Oneal2001) find that the magnitude of US rally effects largely depend on elite messages. More generally, consistent elite messages are expected to sway public opinion in the direction of the message (Zaller Reference Zaller1992).

All of these conditions for rally effects were in place as the corona virus crisis deepened in Sweden (as they were in most industrialized democracies). Conceivably, the shift from the initial phase to the acute phase triggered feelings of national affiliation, the need for security and feelings of anger and anxiety; and political elites were united in the fight against the pandemic. Considering this, we expect to observe an increasing trust in government institutions during the acute phase of the crisis (hypothesis 1). In support of this expectation, systematic research (Bol et al. Reference Bol, Giani, Blais and Loewen2020), as well as snap opinion polls (Supplementary Information (SI), Table S14), have documented strong support for the measures taken and for the authorities directly involved in crisis management, in several countries around the globe.

However, we caution that the rally effect should not be taken for granted in the context of pandemics (Amat et al. Reference Amat, Arenas, Falcó‐Gimeno and Muñoz2020). For example, research on reactions to the swine flu epidemic (H1N1) in the Netherlands in 2009 shows a decrease in institutional trust at the peak of the crisis (van der Weerd et al. Reference van der Weerd, Timmermans, Beaujean, Oudhoff and van Steenbergen2011). More generally, people frequently find reasons to blame their government for lack of efficiency in the aftermath of natural disasters (Healy & Malhotra Reference Healy and Malhotra2009).

The rally effect in its original form relates to institutional trust only. Therefore, expectations about the direction of change, or indeed about change over stability, are less certain when it comes to interpersonal trust. Transferring the reasoning above, the mechanisms that strengthens affinity with the ingroup should reasonably work also for trust in unknown others within the nation. Similarly, interpersonal trust will increase if citizens generalize from mediated and personal experiences about unselfish and solidary acts of other people during the crisis (Pavitt Reference Pavitt2018). Furthermore, there is evidence that interpersonal trust is partly driven by institutional trust (Rothstein & Eek Reference Rothstein and Eek2009; Sønderskov & Dinesen Reference Sønderskov and Dinesen2016), which implies that increased trust in other people will follow suit from a rally towards trust in institutions.

However, there are caveats to keep in mind. To the extent that citizens generalize their beliefs about other people on the basis of stories about hoarding of supplies like toilet paper, we will rather observe declining trust in other people during the acute phase of the crisis (Fehr & Gächter Reference Fehr and Gächter2000). On a theoretical note, furthermore, cultural theories on social trust maintain that interpersonal trust is an ingrained attitude that only changes gradually and under extreme circumstances, if at all (Uslaner Reference Uslaner2002).

Overall, in the Swedish context where citizens were given freedom under responsibility, and where people in general showed restraint, we expect to observe an increase in interpersonal trust during the acute phase of the crisis (hypothesis 2).Footnote 3 We leave it an open question how interpersonal trust developed in countries where their government undertook more draconian measures to keep people in line (Rubin et al. Reference Rubin, Potts and Michie2010).

We expect largely homogeneous effects among the Swedish public for both types of trust attitudes. However, we are open for that some groups of citizens reacted differently to the crisis. In particular, we direct attention to vulnerable groups who have personal reasons to call for more stringent policies (Vaughan & Tinker Reference Vaughan and Tinker2009) and to groups who oppose the incumbent government for political reasons. The former group is represented by the elderly and the low educated. The latter group by supporters of the opposition parties.

Data and methods

Our data are from The Swedish Citizen Panel, an online panel survey run by the Laboratory of Opinion Research (LORE), at the University of Gothenburg.Footnote 4 LORE has recruited a pool of 75,000 panellists (http://web.retriever-info.com.ezproxy.ub.gu.se/services/archive?) s, whereof 80% are recruited through non‐probability processes. We invited 18,045 panellists to the first panel wave during the initial phase of the coronavirus crisis (t0). Out of the invited, 12,881 chose to participate, yielding a gross participation rate of 71.4%. In this baseline sample, males, elderly and highly educated are overrepresented in relation to the general public (see SI, Table S6). We refer to this group of individuals as the large sample.

In addition, a sub‐sample of respondents was recruited with higher priority to representativeness. The sub‐sample is part of a long‐term panel that was recruited already in December 2018 to be followed through future and, at the time, unknown social crises. The original sample (n = 4,056) was pre‐stratified to be representative of the general public with regard to gender, age and education. We invited the 2,499 respondents who took the first survey (t − 1) to participate in the current study (t0), whereof 1,662 did (a gross participation rate of 66.5 per cent). This group is referred to as the representative sample and is used for robustness checks (Table S6 in the SI provides sample characteristics).

The baseline sample of 12,881 panellists was invited to a second round of web interviews during the acute phase of the crisis (t1). Participation rate in t1 was high, 88.5% in the large, full sample (n = 11,406) and 88.1% in the smaller representative sub‐sample (n = 1,464). There is no evidence that panel attrition affects the conclusions. (See Tables S6 and S13 for additional details on sample composition over time and attrition based on background factors, respectively.)

While a probability‐based sample would have been preferable in order to make exact estimates of effect sizes, our panel data can be expected to reproduce the true underlying change processes with reasonable certainty.

Treatment

We want to learn how people updated their trust attitudes as the coronavirus crisis developed from the initial phase to the acute phase. Expressed differently, the deepening of the crisis is a treatment that may causally influence people's trust in government institutions and in unknown others. The treatment consists of the combined experiences that people had during the acute phase of the crisis. We do not attempt to isolate effects of, for instance, government policies, speeches by political leaders, the behaviour of citizens, news media coverage, social media information flows or, indeed, the number of deaths in COVID‐19. In the methodological literature, this is known as a compound treatment (Hernán & VanderWeele Reference Hernán and VanderWeele2011).

We date the start of the initial phase of the crisis in Sweden to 2 February 2020, when the government classified the COVID‐19 as a dangerous disease to society. We date the start of the acute phase of the crisis to 11 March 2020, when the Public Health Authority (PHA) had upgraded the spread of the epidemic to community transmission and the WHO assessed the COVID‐19 to have reached pandemic proportions. (See SI for further documentation of events during the two phases of the crisis).

The data analysis relies on interviews from the first panel wave (t0) that were conducted between 24 February 2020 and 10 March 2020, at the end of the initial phase. At the time, thus, participants were aware that something unusual had happened, but they could not foresee the extent of the coming events. As explained in our pre‐analysis plan, we excluded a small number of t0 interviews conducted after 10 March 2020. The exclusion makes no substantial difference to the results (see SI, Tables S2–S4 for the date of interviews).

The second panel wave (t1) was in the field well into the acute phase of the crisis, from 31 March 2020 to 14 April 2020. While events continued to evolve from day to day during the field period, all subjects had been heavily treated with crisis experience and there was no end in sight.

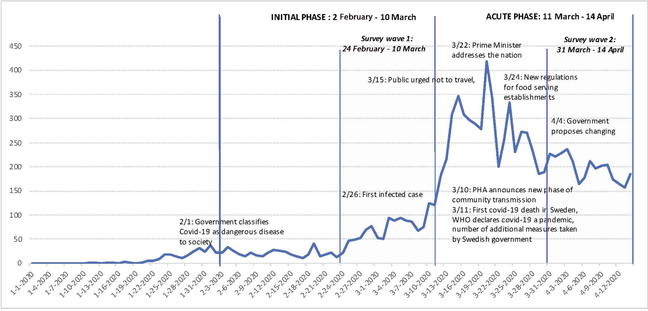

Figure 1 shows the number of articles about the coronavirus in Sweden's four largest daily newspapers from 1 January 2020 to 14 April 2020. It documents that the news media started to pay attention to the coronavirus during February, and that news coverage increased dramatically after 10 March 2020, when the PHA announced that the coronavirus was spreading in society.

Figure 1. Number of articles about the coronavirus in Sweden's four largest daily newspapers, 1 January–14 April 2020. [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Note: The four newspapers are Dagens Nyheter, Svenska Dagbladet, Aftonbladet, and Expressen. The material was retrieved from the archive Retriever 18 April 2020 (http://web.retriever-info.com.ezproxy.ub.gu.se/services/archive?) using the search term corona*.

Empirical strategy

By looking at individual‐level change, we can estimate the effect of the deepening of the crisis on the two types of trust attitudes while controlling for inter‐individual differences. Our identification strategy hinges on that no other factor than the deepening coronavirus crisis affected respondents’ trust attitudes at t1. Given the extreme character of the crisis, and given that our t0 interviews were conducted close to the beginning of the acute phase of the crisis, this is a reasonable assumption.

We examine change over time with paired t‐tests since measurements are for the same individuals over time. t‐Tests are complemented with fixed effects estimation with clustering on individuals. Here, interview times (t − 1, t0, t1) are dummy coded and included as independent variables. All statistical tests are two tailed.

Results

The coronavirus crisis increases levels of institutional trust (H1)

To measure institutional trust, we asked the following question: ‘Generally speaking, how much trust do you have in Swedish government authorities?’ Thus, we targeted overall trust in government institutions, the kind of trust attitude that will be relevant in the long term, post the coronavirus pandemic (Norris Reference Norris, van der Meer and Zmerli2017). Responses were recorded on a fully labelled five‐point scale running from ‘very high’ to ‘very low’. For ease of interpretation, we recoded responses on the measures of trust to range from 0 to 1, with high numbers indicating a more trusting attitude. (See Table S5 in SI for details on question wordings, response options, original values and recodes. Tables S7 and S8 include further descriptive details on the measures.)

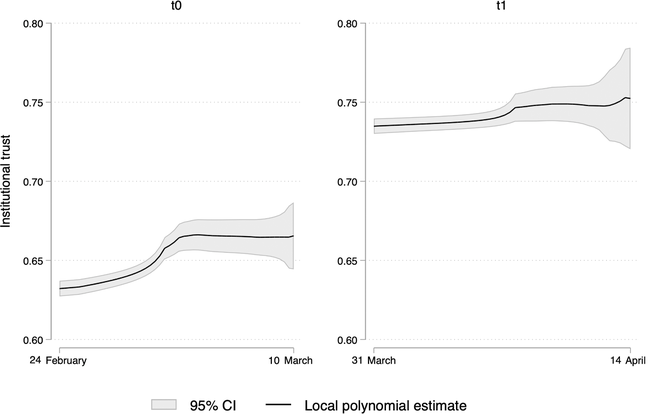

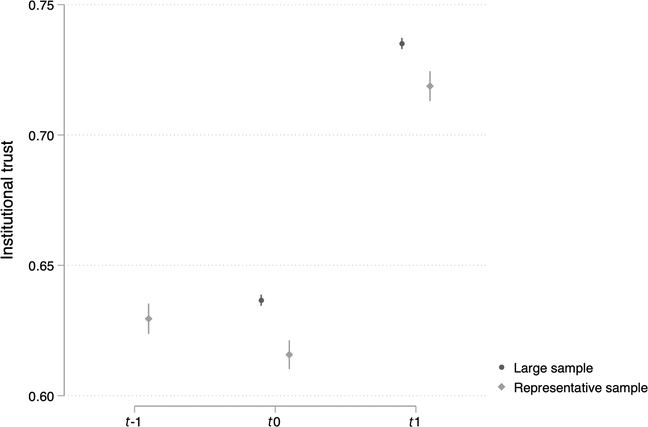

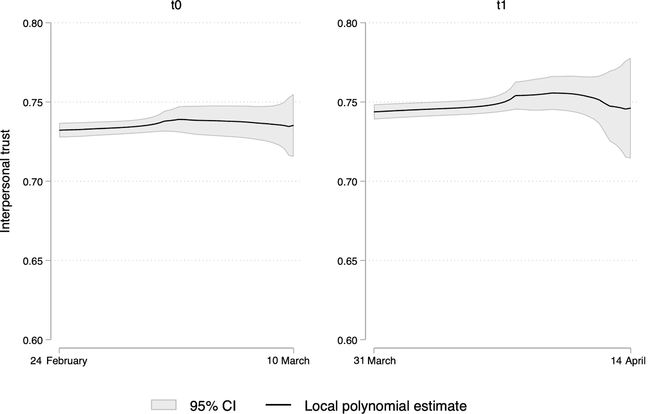

Before turning to the parametric test of our hypothesis that the coronavirus crisis increases institutional trust, Figure 2 illustrates non‐parametric smoothed local means and 95% confidence intervals by interview date. This estimation method makes no assumptions about the functional form during the time periods of interviewing. The figure suggests that there was an increase in institutional trust between t 0 and t 1.

Figure 2. Institutional trust by survey participation date.

Note: The black line is the kernel‐weighted local polynomial estimate (local mean smoothing) with 95% confidence interval in grey. Bandwidth = 3, kernel function = Epanechnikov.

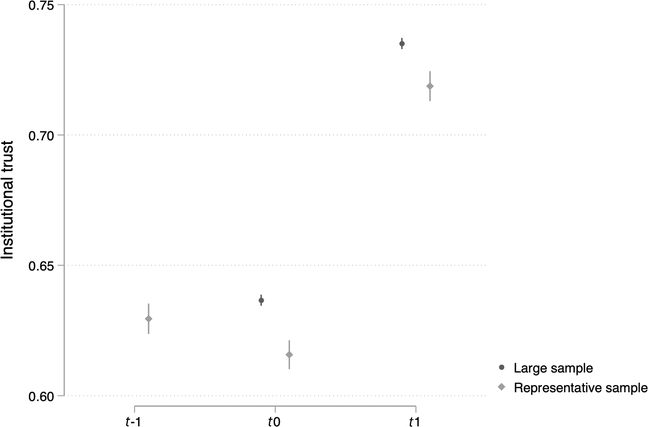

A paired t‐test among the same individuals (n = 7,206) who answered the same question at t 0 and t 1 confirms that there indeed was a rise in institutional trust (mean difference = 0.098, 95% CI [0.094, 0.103], t 7205 = 45.24, p < 0.0001, d = 0.53). The result (also depicted in Figure 3) yields support for the rally hypothesis on institutional trust. Effect size calculations rely on Cohen's d z for paired samples t‐tests:

![]() (Lakens Reference Lakens2013).

(Lakens Reference Lakens2013).

Figure 3. Mean values of institutional trust over time.

Note: Means of institutional trust at t − 1, t 0 and t 1 with 95% confidence intervals. The estimates are based on fixed effects regression with clustering on individuals. (See Table S9 (models 1 and 2) in the Supplementary Results for details.)

We document a comparable rally effect with the representative subsample, attesting to the robustness of the shift. This sample was asked the same question on institutional trust at t − 1 too. In the representative sample (n = 1,415), the mean increase in trust from t0 to t1 was 0.103 (95% CI [0.093, 0.113], t 1414 = 20.86, p < 0.0001, d = 0.55). Moreover, the increase during the time period of over a year from t − 1 to t1 in the representative sample was 0.089 (95% CI [0.079, 0.099], t 1414 = 17.25, p < 0.0001, d = 0.46). Taken together, this indicates that the increase in institutional trust occurred across Sweden in around the month that the coronavirus crisis reached its acute phase.

Importantly, the treatment effect is largely homogeneous across groups who could have reason to hold back their support of government institutions. The elderly, who are most vulnerable to the COVID‐19 disease, and individuals with lower education, who had fewer opportunities to work from home during the crisis, possibly reacted slightly more positively than more privileged groups did. The only indication of a heterogeneous effect relates to party support. Supporters of the opposition parties may have increased their level of institutional trust somewhat less than supporters of the incumbent government. We refer to Table S12 in SI for details on this analysis.Footnote 5

The coronavirus crisis increases levels of interpersonal trust (H2)

Our measure of interpersonal trust was the following: ‘In your opinion, to what extent is it generally possible to trust people?’ We used a five‐point response scale with designated endpoints ‘people cannot generally be trusted’ and ‘people can generally be trusted’.

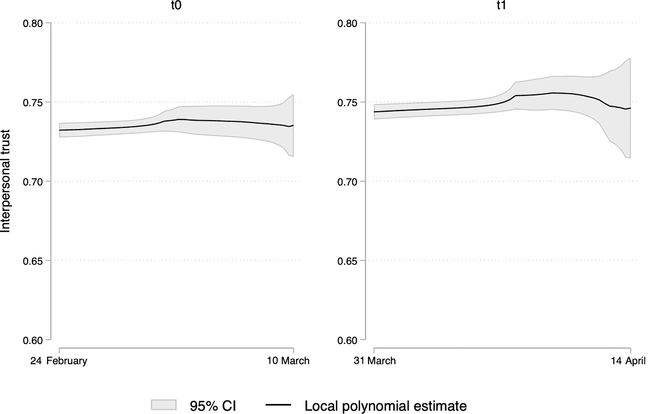

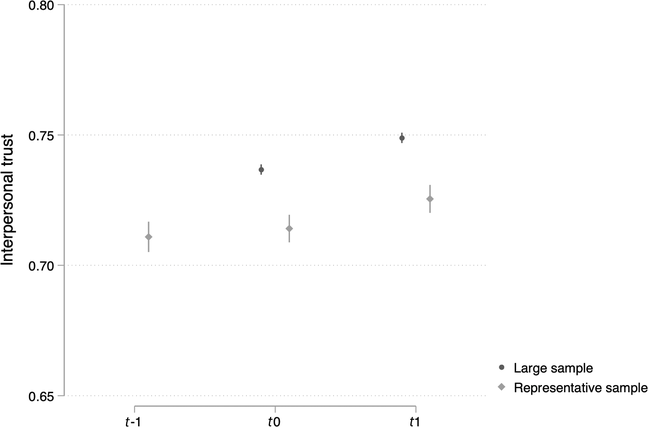

The coronavirus crisis also seems to have increased trust in other people (Figures 4 and 5). The mean difference among the same individuals (n = 7,184) who gave valid answers to the question on interpersonal trust at both occasions is 0.012 (95% CI [0.008, 0.016], t 7183 = 5.96, p < 0.0001, d = 0.07). The increase in interpersonal trust is substantially the same with the representative sample in the short term (from t0 to t1; mean difference = 0.011, 95% CI [0.002, 0.020], t 1406 = 2.50, p = 0.012, d = 0.07) and long term (from t − 1 to t1; mean difference = 0.015, 95% CI [0.005, 0.024], t 1406 = 2.90, p = 0.004, d = 0.08).

Figure 4. Interpersonal trust by survey participation date.

Note: Interpersonal trust has been recoded to range from 0 to 1 with higher values indicating higher trust. The black line is the kernel‐weighted local polynomial estimate (local mean smoothing) with 95% confidence interval in grey. Bandwidth = 3, kernel function = Epanechnikov.

Figure 5. Mean values of interpersonal trust over time.

Comment: Means of interpersonal trust at t − 1, t 0 and t 1 with 95% confidence intervals. The estimates are based on fixed effects regression with clustering on individuals. (See Table S9 (models 3 and 4) in the supplemental material for additional details.)

In absolute numbers, the shift might seem small, but it is important to put it in the appropriate context. Compared to the increase in institutional trust, the change in interpersonal trust is around a tenth. On the other hand, interpersonal trust is often seen as very stable, almost like a personality trait (Uslaner Reference Uslaner2018). From this perspective, it is remarkable that the crisis appears to change something akin to a personality feature. As documented in SI Tables S11 and S12, the change is general and can also be found in the groups we pay special attention to, the vulnerable and supporters of opposition parties.

Discussion

Based on a rich set of panel data collected before and during the coronavirus pandemic, our study demonstrates distinct rally effects among the Swedish public during the crisis. Increasing public support for incumbent governments and authorities have been reported in snap opinion polls in many countries (SI, Table S14), and in systematic research across 15 European Union member states (Bol et al. Reference Bol, Giani, Blais and Loewen2020). However, in addition to mapping trust formation processes with greater precision than in previous research, our study provides three new important insights: (i) that the rally effect goes beyond politicians in power and government institutions that are directly responsible for crisis management (we measure generalized trust in government authorities) (hypothesis 1); (ii) that the rally effect extends to interpersonal trust in unknown others (hypothesis 2); (iii) and that the rally effect is largely homogeneous across groups that could potentially relate distantly to government authorities. The rally effect is clearly stronger for trust in government authorities than for interpersonal trust in unknown others, but both types of trust grew significantly as Swedes moved from the initial to the acute phase of the crisis.

Moreover, the choice of country context – Sweden – gives the study additional weight. It proves that the public rally in support of an approach that rests upon voluntary compliance with regulations rather than on compulsory lockdowns of society (Paterlini Reference Paterlini2020). Moreover, it shows that public support can grow despite ongoing public debate about crisis management. It is good news for the fundamental legitimacy of the Swedish democratic regime.

We cannot determine how far results generalize to other national contexts. As mentioned, the rally effect on institutional trust is found in countries around the globe. This suggests that three months into the pandemic, citizens might rally round the incumbent government independently of the choice of strategy for dealing with the coronavirus, and, possibly, independently of the democratic status of the regime. The commonly observed rally effect indicates that citizens typically have reacted to the coronavirus crisis as if it were an external threat towards their community, much like when at war (Mueller Reference Mueller1970) or when hit by a terrorist attack (Dinesen & Jæger Reference Dinesen and Jæger2013; Hetherington & Nelson Reference Hetherington and Nelson2003). This is different from when natural disasters hit countries, when citizens are prone to turn against their government for failure to act effectively (Healy & Malhotra Reference Healy and Malhotra2009).

However, to date there is little to no information about how people in different country contexts update their interpersonal trust in unknown others. In the absence of comparative information, we do not know whether the increasing support extends beyond incumbent governments following extensive lockdowns of societies. Feasibly, the fact that most governments do not trust citizens’ ability to act sensibly, absent strict rules spill over into increasing distrust in unknown other (‘if the government does not trust people to do the right thing, why should I?’). But it is also conceivable that other trust formation processes are in play. To map changes in interpersonal trust is a matter of urgency for researchers and polling organizations as the coronavirus crisis evolves. Equally important for public opinion research is to design studies that enable a better understanding of the causal mechanisms that underlie rally effects. It is possible that there are different drivers of different outcomes.

Looking at the coronavirus crisis generally, the study reported here is informative about public reactions during the first phases of the crises. When our survey ended, in mid‐April, the acute phase of crisis was still at its peak. Since then countries have moderated the restrictions, and several have noted a stabilization or decline in infected and dead cases. In parallel, emerging signs indicate that the crisis is evolving into an accountability phase, when strategies and measures are questioned and criticized by opposing political blocs (Kuipers & t'Hart Reference Kuipers, t'Hart, Bovens, Goodin and Schillemans2014) and/or investigative media (de Burgh Reference de Burgh2013; Kovach & Rosenstiel Reference Kovach and Rosenstiel2014). This, in turn, will most probably counter the rally effect. However, to date, it is a positive story about the possibility of dealing with the consequences of the pandemic.

Acknowledgments

We want to thank Sophie Cassel for outstanding work with collecting the panel data, Anders Sundell and Peter Dahlgren for generously sharing data and Tomas Odén for comments. We also want to thank the editorial team and the three anonymous reviewers for constructive criticism and suggestions during the process. The research is funded by Grant # 2017‐2860 from the Swedish Civil Contingencies Agency.

Supporting Information

Additional supporting information may be found online in the Supporting Information section at the end of the article:

Figure S1: Google searches in Sweden for ‘corona’, January 4th – April 3rd 2020, relative search volume (number of searches).

Figure S2: Articles on Swedish Wikipedia (sv.wikipedia.org) searching for items ‘corona’, ‘pandemic’, ‘epidemic, ‘respiratory infection’ and ‘virus’, January 1st – April 4th 2020 (numbers of articles).

Figure S3: Mobility at transit stations, workplaces, and retail and recreation spaces in 4 Nordic countries.

Table S1: Restrictions imposed and advices given by the Swedish government

Table S2: Participation dates, t‐1.

Table S3: Participation dates, t0.

Table S4: Participation dates, t1.

Table S5: Questions, response options, coding and variable names on institutional and interpersonal trust.

Table S6: Respondent characteristics at t‐1, t 0 and t 1.

Table S7: Descriptive statistics of institutional and interpersonal trust.

Table S8: Correlation matrix of institutional and interpersonal trust.

Table S9: Institutional and interpersonal trust between t‐1, t 0 and t 1 (mean values)

Table S10: Coronavirus priming experiment effect on institutional trust (OLS, coefficients).

Table S11: Differential change between t‐1, t 0 and t 1 in institutional and interpersonal trust (change scores)

Figure S4: Differential change in institutional trust during the crisis.

Figure S5: Differential change in interpersonal trust during the crisis.

Table S12: Heterogenous change over time in institutional trust and interpersonal trust

Table S13. Panel attrition between t 0 and t 1

Table S14: Countries with strong support (rally effect) for the government managing of the corona crisis, distributed by level of democracy.

Supplementary Material