Introduction

At the end of 2022, Covid‐19 had led to over 6.6 million deaths worldwide (World Health Organization, 2022) with profound economic, political and social consequences. Yet, we still know comparatively little about whether and how views of Covid‐19 and behaviours during the pandemic were associated with well‐established partisan divides between voters. In this research note, we examine the extent to which partisanship is associated with people's various perceptions of pandemic‐related threats, their behaviour as well as compliance with public health measures.

Understanding the relationship between partisanship and attitudes as well as behaviours towards the pandemic is important: if perceptions of Covid‐19 differ strongly depending on pre‐existing party preferences, partisan divisions in societies might undermine the ability of governments to effectively address the pandemic crisis. Certain voters who hold systematically distinct beliefs about the seriousness of Covid‐19 may be more reluctant to follow government policies, precisely at a time where united collective action is most needed.

The United Kingdom presents an interesting case to analyse the degree to which partisanship accounts for individual differences across distinct dimensions of Covid‐19 perceptions, attitudes and behaviours. It had nearly 200,000 deaths (WHO, 2022), making it one of the countries most affected by the pandemic (Roser, Reference Roser2020). It also implemented a strict national lockdown in March 2020 (Daly et al Reference Daly, Ebbinghaus, Lehner, Naczyk and Vlandas2020) which led to the Conservative government losing support, especially from its more recent voters (Green et al, Reference Green, Evans and Snow2020). To the extent that the pandemic and the national lockdown adversely affected different segments of the electorates in distinct ways, this represents a good case to assess how societies’ partisan polarisation relates to Covid‐19 behaviours and attitudes. In addition, the extent to which the United Kingdom is politically polarised and driven by partisan dynamics has been widely debated in previous literature (Cohen & Cohen, Reference Cohen and Cohen2021; Evans & Neundorf, Reference Evans and Neundorf2020) and some argue that the British Public has ‘depolarized’ politically (Adams et al., Reference Adams, Green and Milazzo2012), so it is neither a ‘most likely’ nor a ‘least likely’ case for observing partisan differences on Covid‐19. Yet, there is still limited evidence on how partisanship may have influenced how individuals perceived these interventions, and whether these perceptions in turn affected their behaviours during the lockdown.

This research note briefly reviews the emerging literature on the relationship between partisanship and Covid‐19 views as well as behaviours, which reveals mixed expectations and findings in other countries. On the one hand, given the distinct ideological characteristics which we document in the next section, right‐wing voters can be expected to be less concerned about Covid‐19 and less compliant with government imposed public health measures than left‐wing voters. On the other hand, voters may align with the views and policies of their preferred political parties. As a result, differences between voter groups may be critically dependent on whether the politicians of different parties have distinct views and the political ideology of the party in power. In the United Kingdom, both political parties seemed to take Covid‐19 seriously and it was the Conservative government that implemented the national lockdown. From this perspective, there could be few differences between Conservative and Labour voters, or it could even be that the former are more compliant with the lockdown.

To explore this question empirically, we provide evidence at two complementary levels of analyses. First, we examine a uniquely large and geographically granular daily survey of nearly 100,000 respondents in the early period of the pandemic in the United Kingdom. The large number of questions it contains allows us to explore empirically the relationship between partisanship and a wide range of Covid‐19 attitudes and behaviours. Second, we create a novel dataset matching Google mobility data throughout 2020 with information about vote shares for different political parties across UK counties in the 2019 general election. We then analyse the effect of the UK national lockdown on changes in mobility, for counties with different levels of support for the Conservative Party.

Our findings suggest that Conservative voters feel less threatened by Covid‐19 and were less compliant with the national lockdown. This echoes findings for other countries, most notably the United States where Republicans also tend to perceive Covid‐19 as a more minor health threat than Democrats and are less likely to follow social distancing rules and to wear masks. This research note provides evidence across a wide range of dimensions and using different datasets that a similar partisan dynamic can be observed in the United Kingdom, despite the much greater consensus among both political parties with a less Covid‐sceptic Conservative party which instigated and strongly supported the national lockdown.

Theory

This short empirical research note does not provide an exhaustive review of the large emerging literature on Covid‐19 nor a full theorisation of the potentially complex relationship between partisanship and pandemics. Instead, we briefly review relevant studies on partisan responses to Covid‐19 to identify some possible theoretical expectations and summarise findings in other countries. To simplify, the literature can be divided into two broad strands.

The first strand focuses on the ideological characteristics, views and attitudes of voters. Studies adopting this approach tend to find that right‐wing voters are more sceptic of Covid‐19 and less compliant with public health measures. Right‐wing individuals tend to prioritise freedom and the economy (Mellon et al., Reference Mellon, Bailey and Prosser2021) at the expense of public health (Ramos et al., Reference Ramos, Vieites, Jacob and Andrade2020). Right‐wing ideology is also in some cases linked with distrusting science and misinformation, which can lead to Covid‐19 scepticism and undermine adherence to public health measures (Latkin et al., Reference Latkin, Dayton, Moran, Strickland and Collins2021). The crucial mediating role of science and information has for instance been documented in Brazil (Xavier et al., Reference Xavier, Lima e Silva, Alves Lara, e Silva, Oliveira, Gurgel and Barcellos2022), Poland (Kossowska et al., Reference Kossowska, Szwed and Czarnek2021) and France (Schultz et al., Reference Schultz, Atlani‐Duault, Peretti‐Watel and Ward2022). Differences in media consumption also appear important to explain Covid‐19 scepticism and lower compliance among right‐wing voters (Pennycook et al., Reference Pennycook, McPhetres, Bago and Rand2022).

The expectations that right‐wing voters should be more Covid‐19 sceptics and less compliant with public health interventions have been corroborated in a wide range of country studies. In the United States, conservativism is associated with Covid‐19 scepticism (Latkin et al., Reference Latkin, Dayton, Moran, Strickland and Collins2021), which in turn leads to lower engagement in preventive behaviours (Pennycook et al., Reference Pennycook, McPhetres, Bago and Rand2022). Republicans also exhibit higher science denialism, different media consumption dynamics and higher economic concerns that make them less pathogen‐avoidant (Samore et al., Reference Samore, Fessler, Sparks and Holbrook2021). Similarly, right‐wing ideology leads to lower Covid‐19 threat perceptions and lower support for public health measures in Australia (Clarke et al., Reference Clarke, Klas and Dyos2021). Brazilian Conservatives also exhibit less social distancing than other groups (Calvo & Ventura, Reference Calvo and Ventura2021; Ramos et al., Reference Ramos, Vieites, Jacob and Andrade2020) and right‐wing voters in Spain were less likely to comply with social distancing (Gualda et al., Reference Gualda, Krouwel, Palacios‐Gálvez, Morales‐Marente, Rodríguez‐Pascual and García‐Navarro2021).

H1: Conservatives are more Covid‐19 sceptic and less compliant with national lockdown.

The second strand emphasises the position and views of parties in government as key factors shaping the Covid‐19 views and behaviours of different voters who may have more or less support (and trust) in the government. Indeed, voting for the government is associated with greater support for Covid‐19 responses in several countries (Jørgensen et al., Reference Jørgensen, Bor, Lindholt and Petersen2021). In the United Kingdom, the national lockdown increased conservative voters’ positive perceptions of the government handling of health in the United Kingdom (Vlandas & Klymak, Reference Vlandas and Klymak2021) and Conservative individuals tend to be more vaccinated (Klymak & Vlandas, Reference Klymak and Vlandas2022). In addition, institutional trust predicts nearly all measures of social distancing compliance in Spain (Gualda et al., Reference Gualda, Krouwel, Palacios‐Gálvez, Morales‐Marente, Rodríguez‐Pascual and García‐Navarro2021), while Japanese conservative voters’ lower likelihood to underestimate the pandemic has been linked to their higher trust in the Conservative government (Qian & Yahara, Reference Qian and Yahara2020). Conversely, feeling close to an opposition party is associated with lower trust in institutions overseeing the Covid‐19 response, for instance in Turkey (Dal & Tokdemir, Reference Dal and Tokdemir2022).

However, this association between supporting the incumbent or the opposition, trust and Covid‐19 views and behaviour depends on the position of the elected government. When the latter is Covid‐19 sceptic, then the dynamics switch. For instance, supporters of Brazil's Jair Bolsonaro report lower perceptions of Covid‐19 risks than the opposition and independents (Calvo and Ventura, Reference Calvo and Ventura2021). Similarly, Kaushal et al. (Reference Kaushal, Lu, Shapiro and So2022) find that support for Trump is a far more important driver of Covid‐19 scepticism than partisanship. Declarations by elected leaders also appear to matter. For instance, French President Macron's televised address focusing on cooperation boosted willingness to comply with restrictions (Anderson, Reference Anderson2022). The partisan compliance gap in the United States narrowed when directives are given by co‐partisan leaders (Goldstein & Wiedemann, Reference Goldstein and Wiedemann2022).

Thus, in countries where the differences between right‐ and left‐wing parties are more minor, or where the right‐wing government in power is supportive of Covid‐19 restrictions, it is plausible that right‐wing scepticism and non‐compliance fade or even become less pronounced than for left‐wing individuals. For instance, in the less polarized Canadian context, the cross‐partisan agreement of political elites on Covid‐19 issues was partly responsible for the fewer partisan differences in Covid‐19 attitudes and behaviours among the electorate (Merkley et al., Reference Merkley, Bridgman, Loewen, Owen, Ruths and Zhilin2020). It might therefore not be the case that Conservative voters are more Covid‐19 sceptic and less compliant in the UK case. Indeed, the Conservative government initiated the national lockdown in March 2020, so to the extent that Conservative voters have greater trust and incentive to follow the policies of the government they elected, we would expect that they had greater compliance with the national lockdown.

H2: Conservatives are less COVID‐19 sceptic and more compliant with national lockdown.

Finally, the extent to which the Labour and Conservative parties shared similar views about the nature of the problem and the appropriate solution, and the degree to which the Conservative government had a clear message, are both contested. On the one hand, most Conservative politicians and the government were much more convinced of the seriousness of Covid‐19 than in some other countries, most notably the United States (Rutledge, Reference Rutledge2020; Sharfstein et al., Reference Sharfstein, Callaghan, Carpiano, Sgaier, Brewer, Galvani, Lakshmanan, McFadden, Reiss, Salmon and Hotez2021). The Labour party also broadly agreed that this was a public health emergency. On the other hand, direct communication on lockdown measures was perceived as contradictory, even among government supporters (McCormick, Reference McCormick2020). Early on, UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson downplayed the threat of pandemic (Jaworska & Vásquez, Reference Jaworska and Vásquez2022). Following Johnson's Covid‐19 illness, some ministers had begun to debate relaxing restrictions only 3 weeks after the implementation of lockdown (Mason & Sample, Reference Mason and Sample2020). Ultimately, this damaged the government's credibility (Lilleker & Stoeckle, Reference Lilleker and Stoeckle2021) which could sow distrust among the public and lower adherence to social distancing. Taken together, this partial but changing consensus between the Conservative party in government and the Labour party in opposition might lead to no substantial differences between the two voter groups.

H3: There are no significant differences between Conservative and Labour individuals in their perceptions of Covid‐19 and their compliance with government lockdown.

Data and methods

Survey data and methods

Our individual level analysis relies on a survey collected daily between 25th of March and 18th of May 2020 by YouGov. Our data therefore begins in March with the announcement of a national lockdown by the UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson. It is a repeated cross‐section survey representative of the UK population with a sample size totalling over 100,000 respondents. We focus on six questions to capture attitudes and behaviours during Covid‐19, which, for reasons of space, we detail and present in the Appendix. Two questions are about the likelihood of catching and recovering from Covid‐19; two are about whether Covid‐19 is taken seriously enough and whether it will cause more deaths than a normal flu; while the remaining two questions deal with individual behaviour (whether the respondent left their home for any reason at all and to what degree they have self‐isolated). To identify partisan affiliation, we use a survey question about which political party respondents identify with.

Our empirical strategy aims to estimate the association between partisanship and a set of behavioural characteristics and beliefs about Covid‐19. We perform a series of linear probability regressions and our main specification is as follows:

where yi ,r ,t is the outcome of interest for an individual i living in region r at time t. Our empirical analysis includes six dependent variables created using the aforementioned Covid‐19 questions: four are about respondents’ views of the pandemic and two are about their behaviours. The coefficient β captures our main regressor of interest: it is coded 1 if the respondent identifies with the Conservative party, and 0 otherwise. We control for various individual time variant and time invariant characteristics (see the Appendix for details). First, we include a number of socio‐economic and demographic attributes, Zi ,t: gender; age groups (18–24, 25–34, 45–54, 55–65 and 65+); education levels (high, medium or low); social grade; marital status; number of children; and employment status; which have been shown to influence compliance with the national lockdown in the United Kingdom (Ganslmeier et al Reference Ganslmeier, Van Parys and Vlandas2022). Second, we account for unobservable time invariant regional heterogeneity by including regional fixed effects αr.Footnote 1 Third, we use data from the UK Office of National Statistics to control for the incidence of Covid‐19 captured by the number of Covid‐19 related death in the last 7 days in the United Kingdom prior to the interview of the respondent. Finally, we include a time trend θt and a quadratic trend θ 2t.Footnote 2 We cluster the idiosyncratic standard errors ei ,r ,t at the survey day‐region levels.

Mobility data and methods

While valuable in its temporal and dimensional granularity, individual level data might suffer from social desirability bias as it does not directly measure behaviour, but relies on respondents accurately declaring their views and behaviours. We therefore complement our survey results with an extensive analysis of county level mobility. We create a novel dataset by matching Google Mobility information covering the period from February to December 2020 with the 2019 General Electoral results for each English county. Excluding weekends and public holidays from our dataset yields 300 days with mobility information in slightly under 50 sub‐regions across England (more details in the appendix). The main specification is the following:

The dependent variable in this model is workplace mobility, which was collected by Google and measures job attendance every day. We take the first difference of this variable to remove any non‐stationarity: long‐term trends in mobility in certain counties, which might be associated with pre‐existing Conservative support, could spuriously correlate with a differential partisan effect of lockdown. Our regressor of interest is the interaction term between a Lockdown dummy that takes the value 0 before the announcement of the national lockdown in the United Kingdom on 23rd March 2020, and 1 thereafter, and a variable measuring the percentage of Conservative votes in a particular county in England in the 2019 general election. We include several control variables (see Appendix for summary statistics, details and sources): logarithms of population density, wages, house prices, ethnicity and the logarithm of the number of Covid‐19 related cases (at regional level). Finally, we include a trend ρt, its squared term ρ2t and regional fixed effects, αr. We cluster the error term εc ,r ,t at the day and region levels.

Results

Results for survey analyses

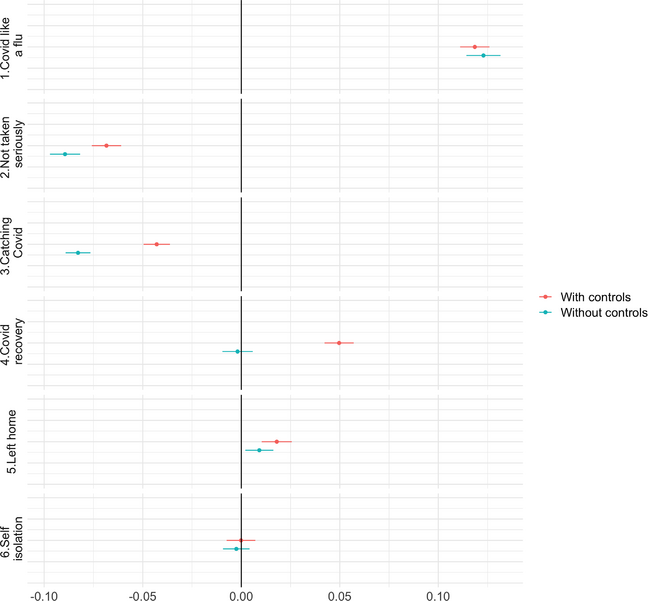

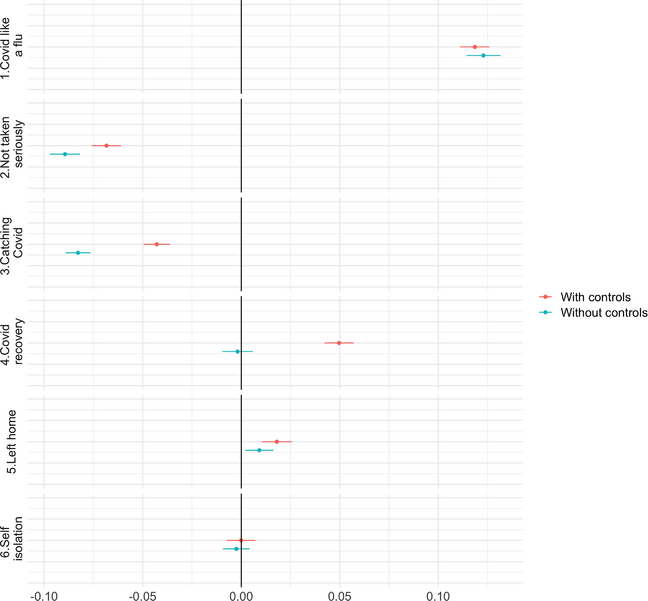

Figure 1 plots the coefficients for Conservative individuals for the six dependent variables, with and without controls, to illustrate whether and how much of the partisan differences disappear when we control for potential confounding factors (see full results in table C.1.3 in the appendix). We find that Conservative individuals are about 12 percentage points less likely to think that ‘Covid‐19 is like a normal flu’, while they are 7.5 percentage points less likely to think that ‘Covid‐19 is not taken seriously enough’. Being Conservative is also positively correlated with being ‘confident that one would recover well’ (5 percentage points higher) and significantly and negatively associated with having a higher ‘perception of catching Covid‐19’ (5 percentage points higher). Consistent with these more Covid‐19 sceptic attitudes, Conservative voters are also more likely to leave home than other voters.

Figure 1. Attitudes and behaviours related to Covid‐19 for Conservative voters. Note: The plot shows the coefficients (with 95 per cent confidence intervals) capturing the effect of being a Conservative voter (as compared to other voters), extracted from regressions of attitudes and behaviours towards Covid‐19 on partisanship. The results that include all parties as compared to Conservative voters are reported in Tables C.1.1 and C.1.2 in the Appendix. [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

We carry out several robustness checks. First, we replicated our results with Labour as compared to Conservative individuals in Tables C.1.1 and C.1.2 in the Appendix. Labour individuals are less likely than the Conservatives to think that ‘Covid‐19 is like flu’ and that they will recover, as well as less likely to leave home, while they are more likely to think it is ‘not taken seriously enough’, that they will catch it and to self‐isolate. Second, we have replicated our main individual level results using probit and logistic regressions (Tables C.1.4 and C.1.5 in the Appendix). The results do not change when using these estimation methods instead of linear probability models. Third, we replicated our main results including time fixed effects in Table C.1.6 in the Appendix. Our results hold throughout all specifications.

Results for mobility analyses

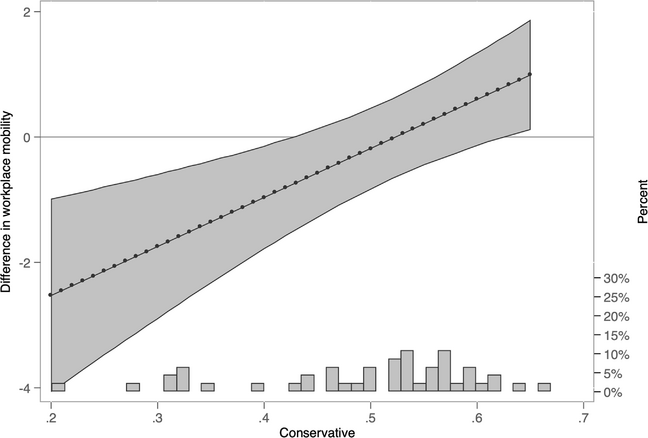

For reasons of space, the full regression results for our mobility analyses are shown in Table C.2.1 in the Appendix. The coefficient for Conservative share and lockdown is negative and statistically significant, while the coefficient for their interaction term is positive and statistically significant. These results suggest that the national lockdown was associated with a fall in the Google mobility indicator measuring movements to workplaces, as would be expected, but that the size of effect was smaller in places with larger Conservative electorates. In Figure 2, we plot the average marginal effect of national lockdown on the change in mobility conditional on the share of Conservative votes. The average marginal effect is negative and statistically significant in counties where the Conservative party received comparatively fewer votes in the 2019 UK national election. By contrast, the marginal effect is not statistically significant in counties where the Conservative parties received comparatively more votes.

Figure 2. The effect of national lockdown on change in workplace mobility in counties with different levels of Conservative votes in previous national election. Note: This figure plots the average marginal effect of national lockdown on change in workplace mobility conditional on the Conservative vote share in counties in the previous national election. The underlying results are shown in Table C.2.1 in the Appendix and generated using the aforementioned model specification. Standard errors are clustered at day‐region level.

In terms of magnitude, the standard deviation in the first difference of workplace mobility is 6.64 so the interaction term of 7.82 is slightly over 1 standard deviation of the dependent variable. At the lowest value of Conservative share, the marginal effect of lockdown is negative, statistically significant and around 2.5, which is roughly one third of a standard deviation in the dependent variable. At more reasonable values such as 35 per cent Conservative share, the marginal effect is negative, statistically significant and above 15 per cent of a standard deviation.

We carry out a number of robustness checks. First, replicating this analysis for different time windows in terms of the number of days included in the analysis (specifically 100, 125, 175, 200, 225, 250, 275 and 300 days). Table C.2.2 in the Appendix shows that this does not change the results. Second, we re‐estimate the model for changes in transit mobility instead of workplace mobility: we find that the lockdown was associated with less mobility only in counties where the Conservative party did not receive a large share of votes (Figure D.1.2 in the Appendix). Third, we check the robustness of our results when we control for essential workers, most notably in the health sector (see Table C.2.4 in the Appendix), and when we control for access to different types of transport (see Table C.2.3 in the Appendix). Fourth, we re‐run our analysis while including time fixed effects (see Table C.2.5 in the Appendix). Finally, the interaction effects remain statistically significant if we rerun our analyses on the level instead of first difference of our two dependent variables ‘workplace’ and ‘transit’.

Conclusion

In this research note, we provide systematic evidence for the importance of partisanship in understanding the views and behaviours of the UK population towards Covid‐19. Voters of different political parties appear to exhibit systematically different perceived risks of Covid‐19 and they tend to behave differently in terms of their compliance with Covid‐19 public health measures. While in principle one could speculate that partisan differences are due to the different socio‐economic and demographic profiles of Conservative voters, our analysis makes clear that these differences remain even when controlling for differences in age, economic position, education, gender, family status, labour market status and regional differences.

Specifically, our findings show that Conservative individuals are more likely to think that Covid‐19 is no more dangerous than a flu and that it is taken too seriously, while they are less likely to fear they will get infected, and more likely to think they will recover if they become infected. At the individual level, they were also more likely to leave their home during the national lockdown, even after controlling for confounding factors, while at the county level the effect of the national lockdown on mobility was negative and statistically significant only in less Conservative counties.

This echoes findings for other countries, such as Spain (Gualda et al., Reference Gualda, Krouwel, Palacios‐Gálvez, Morales‐Marente, Rodríguez‐Pascual and García‐Navarro2021), Brazil (Ramos et al., Reference Ramos, Vieites, Jacob and Andrade2020), Austria (Knobel et al., Reference Knobel, Zhao and White2022) or Norway (Wollebæk et al., Reference Wollebæk, Fladmoe, Steen‐Johnsen and Ihlen2022). These results also provide an interesting contrast to studies on the United States where the high political polarisation (Hetherington, Reference Hetherington2009; Lupton, et al., Reference Lupton, Smallpage and Enders2020) has been linked with partisanship being a strong driver of individual differences in Covid‐19 perceptions and compliance (Allcott et al., Reference Allcott, Boxell, Conway, Gentzkow, Thaler and Yang2020; Clinton et al., Reference Clinton, Cohen, Lapinski and Trussler2021; Gollwitzer et al., Reference Gollwitzer, Martel, Brady, Pärnamets, Freedman, Knowles and Bavel2020; Grossman et al., Reference Grossman, Kim, Rexer and Thirumurthy2020). US Republicans tend to perceive Covid‐19 as a more minor health threat than Democrats and are also less likely to follow social distancing rules and to wear masks. Our research note suggests that partisanship is associated with pandemic related individual views and behaviours even when there is consensus among both main political parties.

Acknowledgements

For excellent research assistance, we are grateful to Adrienne McManus and Razan Amine. We would also like to thank Jonathan van Parys, Anthony Wells, Adam McDonnell and Beth Mann at YouGov for sharing their survey data.

Online Appendix

Additional supporting information may be found in the Online Appendix section at the end of the article: