Introduction

The middle class serves as a barometer for economic health and social trends within a society; their engagement in volunteering reflects broader societal dynamics, including economic conditions (Lim & Laurence, Reference Lim and Laurence2015), cultural values, and social cohesion. The middle class, characterized by attributes such as education, stable employment, and a supportive family environment, is particularly notable for its contributions to formal volunteering (Einolf & Yung, Reference Einolf and Yung2018). Dean (Reference Dean2016, Reference Dean2021) described this demographic group as a crucial segment of society for volunteering, with studies by Hustinx et al. (Reference Hustinx, Grubb, Rameder and Shachar2022) and Seabe and Burger (Reference Seabe and Burger2022) corroborating the notion that the middle class forms a significant reservoir of volunteers.

The middle class is socially included and materially secure. Studies by Bortree and Waters (Reference Bortree and Waters2014) and Son and Wilson (Reference Son and Wilson2011, Reference Son and Wilson2012) underscore the link between social inclusion and volunteering tendencies, highlighting that lower levels of social inclusion often correlate with diminished volunteering (a stronger connection to a collective correlates with a greater willingness to undertake voluntary actions Dang et al., Reference Dang, Seemann, Lindenmeier and Saliterer2022). For example, affiliation with a particular religion or membership in a leisure activity group increases the likelihood of active volunteering because of interactions with other people. However, belonging to a minority group decreases the likelihood of volunteering (see Meijeren et al., Reference Meijeren, Lubbers and Scheepers2023). For example, in Switzerland, the difference between the shares of volunteers in populations with and without Swiss nationality is 21 percentage points—64% vs. 43% (see Lamprecht et al., Reference Lamprecht, Fischer and Stamm2020, p. 49).

In the context of Switzerland, regular surveys of the Swiss population's voluntary engagement, coupled with recent statistics indicating a shrinking middle class (BFS, 2021), pose critical questions about the future amount of volunteering amid challenging sociodemographic and societal developments. These developments raise important questions regarding the factors that may endanger the middle class as a main reservoir of volunteers.

To fill this research gap, we seek to examine the long-term development of middle-class involvement in formal volunteering in Switzerland. Using data from the Swiss Volunteering Survey at four different points between 2006 and 2019 (Freitag et al., Reference Freitag, Manatschal, Ackermann and Ackermann2016; Freitag et al., Reference Freitag, Steffen and Bühlmann2006; Lamprecht et al., Reference Lamprecht, Fischer and Stamm2020; Stadelmann-Steffen et al., Reference Stadelmann-Steffen, Traunmüller, Gundelach and Freitag2010), we endeavor to analyze the nexus between middle-class status and formal volunteering. Specifically, we frame our middle-class research with social capital theory (Putnam, Reference Putnam2000) and human capital theory (Becker, Reference Becker1993). Thus, we investigate the role of human capital, social capital, time availability, political engagement, orientation toward other people and society, and trust in others as factors that shape volunteering trends within the middle class. Consequently, our research questions focus on the significance of the middle class for formal volunteering in Switzerland: What is the share of the middle class volunteering in Switzerland? Has middle-class engagement in volunteering changed over time? What factors influence the availability and willingness of the middle class to volunteer? In particular, the last question has practical implications for organizations using the help of volunteers.

We focus our research on formal volunteering (through organizations) by the middle class because this workforce is highly important to the functioning of nonprofit organizations in many societal fields, most importantly sports, culture, and social services (Studer, Reference Studer2016). Informal volunteering (done independently of any formal organization, often within community, family, or social networks), while important, is beyond the scope of this research. Moreover, we are aware of other social classes, but we address their volunteering activities only indirectly when we compare the contributions of various social classes to formal volunteering.

The paper is organized as follows. After the introduction, the second section discusses theoretical approaches to the contribution of human capital and social capital to volunteering. Section three describes the data from the Swiss Volunteering Survey and the structural equation modeling approach we applied in our analysis. Section four discusses the results—showing the importance of trust and political engagement in volunteering—while in the case of time and orientation toward society, the results are inconclusive. We also find less volunteering in the less wealthy class than in the middle class. The final section concludes.

Middle Class Volunteering Through Theories of Social and Human Capital

Smith, Stebbins, and Grotz (Reference Smith, Stebbins and Grotz2016, p. 1396) define formal volunteers as “…serving in a formal nonprofit group or volunteer program of a larger parent organization that sponsors or directs the individual’s volunteer action….” Hence, formal volunteering represents an intersection of requirements and expectations from organizations and individual volunteers. Individuals volunteer under three conditions: (i) they are willing to volunteer, (ii) they have know-how and skills, and (iii) they are available (Hager & Brudney, Reference Hager and Brudney2011; Haski-Leventhal et al., Reference Haski-Leventhal, Meijs, Lockstone-Binney, Holmes and Oppenheimer2018). Our research is framed within the contexts of human capital theory (Becker, Reference Becker1993) and social capital theory (Putnam, Reference Putnam2000) and focuses on investigating skills and expertise, the availability of time for volunteering, and the motivation behind the willingneSs to volunteer.

Middle Class

The concept of the middle class lacks a universally accepted definition. For example, Nguyen and Romy (Reference Nguyen and Romy2017) define the middle class based on monthly income, specifically identifying those households earning between 70 and 150% of the Swiss median income as middle class. According to this criterion, nearly two-thirds of the Swiss populace can be considered middle class. Conversely, Banerjee and Duflo (Reference Banerjee and Duflo2008) adopt the Easterly (Reference Easterly2001) definition, which delineates the middle class as individuals earning between the 20th and 80th income percentiles.

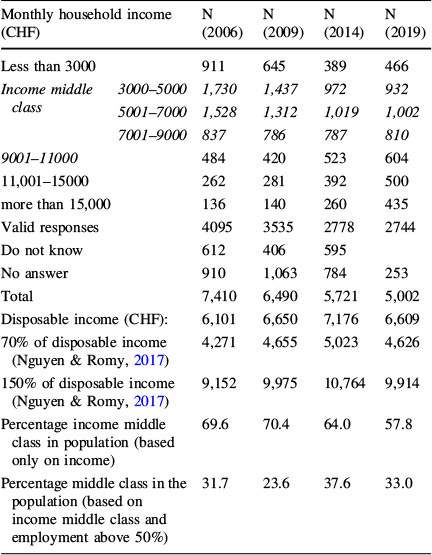

To explore the middle class's involvement in formal volunteering, we must narrow down the term middle class to analyze the Swiss Volunteering Survey categories. Our analysis differentiates between two distinct definitions of the middle class. The first, which we term the "income middle class," is defined according to Nguyen and Romy (Reference Nguyen and Romy2017) income-based criteria (detailed in Table 1, including further elaboration and operationalization). Second, by integrating Nguyen and Romy (Reference Nguyen and Romy2017) income-based criteria with Pressman (Reference Pressman2007) employment-based criteria—which consider individuals working 50% or more of full-time hours—we introduce the concept of the "employment middle class" as our second definitional approach. Consequently, the size of the analyzed group may vary slightly across surveys. Incorporating educational attainment criteria would further reduce the size of the middle class.

Table 1 Swiss middle class according to income and employment.

|

Monthly household income (CHF) |

N (2006) |

N (2009) |

N (2014) |

N (2019) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Less than 3000 |

911 |

645 |

389 |

466 |

|

|

Income middle class |

3000–5000 |

1,730 |

1,437 |

972 |

932 |

|

5001–7000 |

1,528 |

1,312 |

1,019 |

1,002 |

|

|

7001–9000 |

837 |

786 |

787 |

810 |

|

|

9001–11000 |

484 |

420 |

523 |

604 |

|

|

11,001–15000 |

262 |

281 |

392 |

500 |

|

|

more than 15,000 |

136 |

140 |

260 |

435 |

|

|

Valid responses |

4095 |

3535 |

2778 |

2744 |

|

|

Do not know |

612 |

406 |

595 |

||

|

No answer |

910 |

1,063 |

784 |

253 |

|

|

Total |

7,410 |

6,490 |

5,721 |

5,002 |

|

|

Disposable income (CHF): |

6,101 |

6,650 |

7,176 |

6,609 |

|

|

70% of disposable income (Nguyen & Romy, Reference Nguyen and Romy2017) |

4,271 |

4,655 |

5,023 |

4,626 |

|

|

150% of disposable income (Nguyen & Romy, Reference Nguyen and Romy2017) |

9,152 |

9,975 |

10,764 |

9,914 |

|

|

Percentage income middle class in population (based only on income) |

69.6 |

70.4 |

64.0 |

57.8 |

|

|

Percentage middle class in the population (based on income middle class and employment above 50%) |

31.7 |

23.6 |

37.6 |

33.0 |

|

The middle class is often regarded as a crucial reservoir for volunteering (Bradford et al., Reference Bradford, Hills and Johnston2016; Dean, Reference Dean2016, Reference Dean2021; Emrich & Pierdzioch, Reference Emrich and Pierdzioch2015; Hustinx et al., Reference Hustinx, Grubb, Rameder and Shachar2022; Seabe & Burger, Reference Seabe and Burger2022). Other studies report only minor differences in volunteering across income groups (Dawson, Baker, & Dowell, Reference Dawson, Baker and Dowell2019; Eimhjellen, Reference Eimhjellen2022), not because of the income itself but because of a lack of social infrastructure and relationships (Lim & Laurence, Reference Lim and Laurence2015).

We anticipate two contradictory effects of belonging to the middle class on volunteering. On the one hand, the time constraints associated with occupational commitments might hinder volunteer participation (Sundeen et al., Reference Sundeen, Raskoff and Garcia2007). On the other hand, having access to sufficient resources, a characteristic often attributed to the middle class, could facilitate greater involvement (Wilhide et al., Reference Wilhide, Peeples and Kouyate2016), and opportunities to develop the skills and confidence associated with leadership might also increase the willingness of the middle class to volunteer (Bradford et al., Reference Bradford, Hills and Johnston2016). These resources enable the purchase of services (e.g., transport or childcare) that free up time for volunteering, which should not be a problem for the middle class. This positive relationship between wealth and generosity is highlighted by reviews by Wiepking and Bekkers (Reference Wiepking and Bekkers2012), Emrich and Pierdzioch (Reference Emrich and Pierdzioch2015), and Korndörfer et al. (Reference Korndörfer, Egloff and Schmukle2015). Meyer and Rameder (Reference Meyer and Rameder2022) show that individual circumstances and resources influence individuals’ types of volunteering and that volunteering mirrors economic and social inequalities.

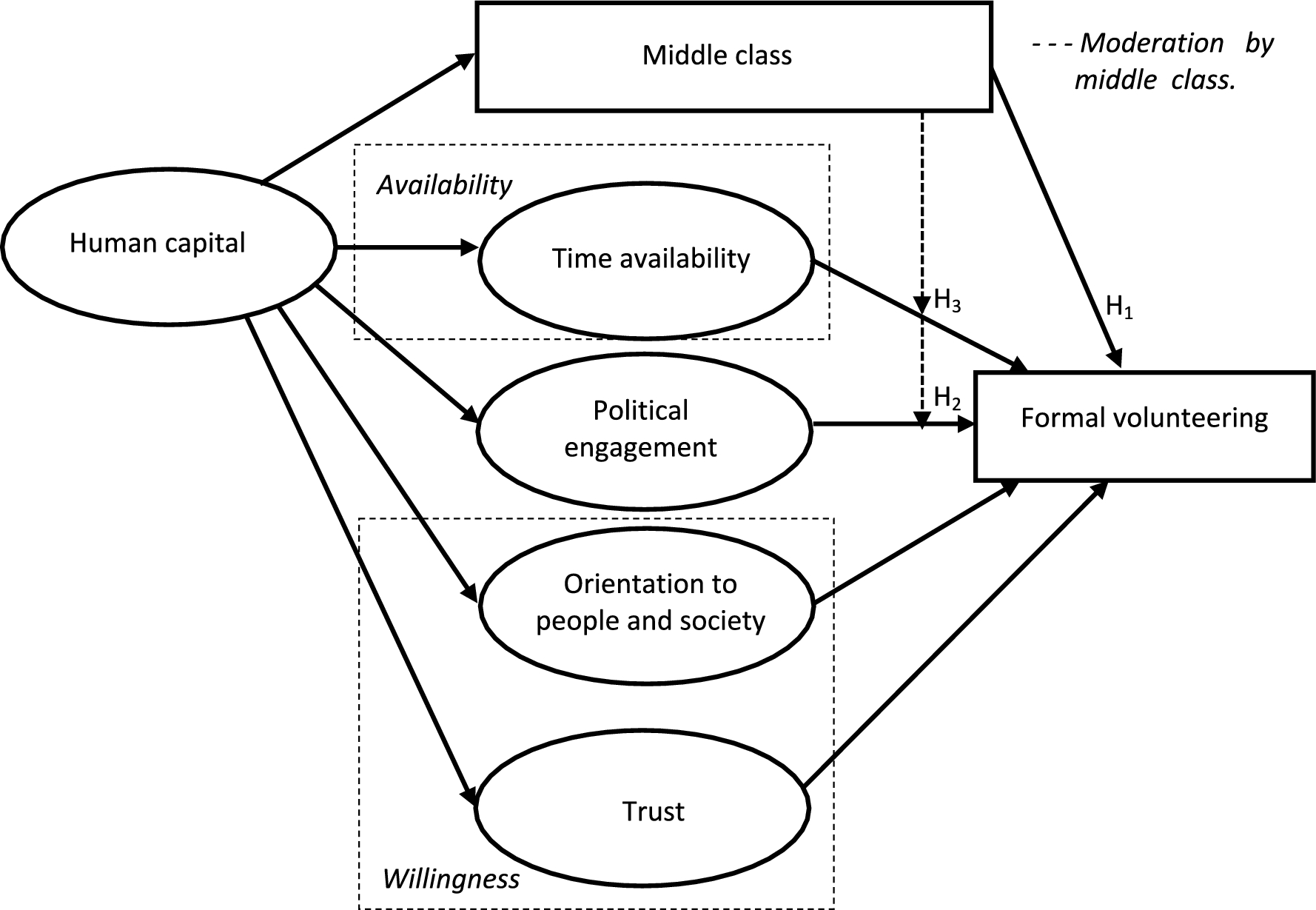

Accordingly, we propose and examine Hypothesis H1, which states that belonging to the middle class positively influences participation in formal volunteering (see Fig. 1 in the Data and methods section).

Fig. 1 Tested model

H1: Belonging to the middle class increases the likelihood of becoming a volunteer.

Social Capital Framing Volunteering

Social capital shaped by socialization and individual traits lays the foundation for willingness to volunteer. Trust, shared norms, and strong social networks, framing social capital size, strongly relate to and support collective and prosocial actions (Brown & Ferris, Reference Brown and Ferris2007; Dang et al., Reference Dang, Seemann, Lindenmeier and Saliterer2022; Lim & Laurence, Reference Lim and Laurence2015; Putnam, Reference Putnam2000), although Brown and Ferris (Reference Brown and Ferris2007) note that altruistic behavior differs for those with different norm- or trust-based social capital. A study by Putnam (Reference Putnam1993) shows that regions’ better economic performance correlates with a higher density of membership in associations. Social capital consists of two components—bonding (among people belonging to a specific group) and bridging (among various groups of people) social capital, while the latter is more likely to bear positive effects to society (Coffé & Geys, Reference Coffé and Geys2007). because it is more cohesive across various groups.

Socialization, through identity, values, networks, and a sense of belonging to a community or group, fosters a supportive environment for volunteering (Grönlund, Reference Grönlund2011) through social contact and the possibility of volunteering (Rotolo & Wilson, Reference Rotolo and Wilson2012). Societies with higher mutual trust feature higher levels of generosity (Chambré, Reference Chambré and M.2020). At the organizational level, investments in social capital increase the willingness to volunteer and may thus reduce the need for other resources (Schnurbein, Reference Schnurbein2013). Furthermore, individuals with prosocial attitudes and values are more motivated and more likely to volunteer (Dang et al., Reference Dang, Seemann, Lindenmeier and Saliterer2022; Shantz et al., Reference Shantz, Saksida and Alfes2014).

Intrinsic motivation is a key factor in fostering a willingness to volunteer (Kim et al., Reference Kim, Fredline and Cuskelly2018). Positive experiences and interactions with others increase volunteers’ willingness to engage repeatedly (Zanin et al., Reference Zanin, Hanna and Martinez2022) and inspire others to volunteer (Güntert et al., Reference Güntert, Neufeind and Wehner2015; Lee et al., Reference Lee, Kim and Koo2016), despite the current trend toward more episodic forms of volunteering (Chambré, Reference Chambré and M.2020).

Aligned with this perspective, we consider an orientation toward society and individuals as an integral aspect of the willingness to volunteer; this includes a positive disposition toward others, reflecting a commitment to help and uphold values, and toward society at large, indicating a sense of community belonging and an interest in societal development. Einolf and Yung (Reference Einolf and Yung2018) reported that for volunteers dedicating ten or more hours weekly to a nonprofit organization (NPO), personal values are crucial for such deep engagement, and these individuals often volunteer without needing an invitation. Moreover, solidarity relations based on symmetrical reciprocity support decisions to volunteer (Georgeou & Haas, Reference Georgeou and Haas2019; Lough, Reference Lough2017).

Additionally, we consider trust a pivotal element in volunteer engagement, serving as a cornerstone of social capital (Putnam, Reference Putnam1993, Reference Putnam2000), alongside norms and mutual support; this encompasses general trust in people and institutions (Kneidinger, Reference Kneidinger2010, p. 25). In comparison to others, those with a high degree of social capital and trust are better equipped to address challenges (Hollenstein, Reference Hollenstein2013, p. 46), and leveraging social capital to mobilize other resources.

Political Engagement

When bonding social capital significantly exceeds bridging social capital, public political engagement can polarize society and lead to adversarial relationships with different groups, grounded in varying moral meanings and roles in society (Evers & von Essen, Reference Evers and von Essen2019). Therefore, we include active interest in politics, participation in referenda, and voting in elections as reflections of political engagement as separate factors from the orientation toward society; we do this because opinion-based identity and moral convictions predict volunteering, whereas efficacy beliefs and anger predict only political engagement (Kende et al., Reference Kende, Lantos, Belinszky, Csaba and Lukács2017).

Rimmerman (Reference Rimmerman and A.2011, p. 28) and Bolton (Reference Bolton2015, p. 24) note that the middle class, owing to their educational background, may feel more empowered to express political views. Additionally, their engagement often results in disproportionate benefits from public services (Hastings & Matthews, Reference Hastings and Matthews2015). Hence, while political engagement may be greater within the middle class, it does not necessarily translate into increased volunteering. Moreover, political interest itself is only one facet of political engagement, providing an important motivation for engagement, but it strongly depends on personality, ability, and political issues (Bolton, Reference Bolton2015, p. 60). Thus, we propose Hypothesis 2:

H2:

Political engagement moderated by belonging to the middle class increases formal volunteering.

Human Capital as a Factor Influencing Volunteering

Human capital theory posits that investments in education, training, health, relationships and support within family are akin to investments in physical capital because they increase an individual's productivity (Becker, Reference Becker1993). This framework has profoundly influenced the way researchers view education and its role in economic development, including its role in volunteering (see the importance of education for volunteering in Brown & Ferris, Reference Brown and Ferris2007).

Human capital forms a basis for volunteering. Volunteers require relevant knowledge and skills to contribute effectively to an NPO (Brown & Ferris, Reference Brown and Ferris2007; Hager & Brudney, Reference Hager and Brudney2011; Haski-Leventhal et al., Reference Haski-Leventhal, Meijs, Lockstone-Binney, Holmes and Oppenheimer2018). This relates to both the volunteers’ level of educational attainment and the training provided by NPOs to meet their particular needs and expectations (Studer & von Schnurbein, Reference Studer and von Schnurbein2013).

Possessing human capital—such as skills, knowledge, and experience—not only increases the likelihood of belonging to the middle class but also enhances the propensity to volunteer (Chambré, Reference Chambré and M.2020). This concept presumes that individuals have resources at their disposal for volunteering (Einolf & Yung, Reference Einolf and Yung2018).

Human capital can help overcome barriers to volunteering. Sundeen et al. (Reference Sundeen, Raskoff and Garcia2007) identify several obstacles, including poor health, transportation challenges (e.g., not owning a car), costs associated with volunteering (e.g., fuel or internet access (Piatak, Dietz, & McKeever, Reference Piatak, Dietz and McKeever2019; Wilhide et al., Reference Wilhide, Peeples and Kouyate2016), or a mismatch between skills and NPO activities), and a lack of information about NPO volunteer needs. Human capital addresses these challenges by providing resources for health care, material assets, training opportunities, and skills in finding relevant information.

Furthermore, human capital increases the likelihood of being invited to volunteer, as NPOs recognize the value of potential volunteer resources, or these individuals proactively seek volunteer opportunities; this includes the availability of time, organizational skills, financial resources, social connections, and expertise to perform volunteer tasks efficiently (see the definition and operationalization of human capital in Forbes & Zampelli, Reference Forbes and Zampelli2014).

Several characteristics of human capital play a role in volunteering. Educational attainment increase the likelihood that individuals will volunteer (Son & Wilson, Reference Son and Wilson2011, Reference Son and Wilson2012) (see Fig. 1 for the model and Annex 1 for the operationalization of human capital in our research). The items constituting human capital include education, or employment status (Sundeen et al., Reference Sundeen, Raskoff and Garcia2007); support of the family and friends operationalized through the size of the household and length of residence in one place (as place attachment positively influences civic responsibility, in Dang et al., Reference Dang, Seemann, Lindenmeier and Saliterer2022); age (as proxy variable for experience, Klevmarken & Quigley, Reference Klevmarken and Quigley1976).

Volunteers require accessible resources for their volunteer activities. These resources include time—the most critical resource—along with financial resources, the framework provided by NPOs (Sundeen et al., Reference Sundeen, Raskoff and Garcia2007), and information about volunteering opportunities to guide potential volunteers.

The most frequently cited barrier to volunteering is a lack of time, followed by a reluctance to volunteer and poor health. Nonvolunteers often attribute their lacking engagement to time constraints, although they face similar time limitations to those of active volunteers (Haski-Leventhal et al., Reference Haski-Leventhal, Meijs, Lockstone-Binney, Holmes and Oppenheimer2018; Sundeen et al., Reference Sundeen, Raskoff and Garcia2007).

Hypothesis H3 examines resource availability (Hager & Brudney, Reference Hager and Brudney2011), status theory and a resource-based approach to volunteering. This hypothesis states that human capital positively determines volunteering through time availability (see Fig. 1). Einolf and Yung (Reference Einolf and Yung2018) note that retired people have more time and extensive work experience and that unemployed individuals also have greater time availability for volunteering (Seabe & Burger, Reference Seabe and Burger2022). Conversely, employed individuals typically have less free time for volunteer activities. Therefore, having nonwork time—working less than half-time (50% of the available working time), retirement, unemployment, or employer support for volunteer activities—creates a pool of time that can be dedicated to volunteering.

H3:

Amount of available time moderated by belonging to the middle class increases formal volunteering.

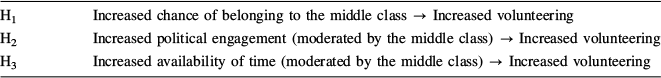

We summarize the hypotheses in Table 2 and Fig. 1.

Table 2 Summary of hypotheses

|

H1 |

Increased chance of belonging to the middle class → Increased volunteering |

|

H2 |

Increased political engagement (moderated by the middle class) → Increased volunteering |

|

H3 |

Increased availability of time (moderated by the middle class) → Increased volunteering |

Data and Methods

Data

We used data from four rounds of the Swiss Volunteering Survey financed by the Swiss Society for the Common Good (Freitag et al., Reference Freitag, Manatschal, Ackermann and Ackermann2016; Freitag et al., Reference Freitag, Steffen and Bühlmann2006; Lamprecht et al., Reference Lamprecht, Fischer and Stamm2020; Stadelmann-Steffen et al., Reference Stadelmann-Steffen, Traunmüller, Gundelach and Freitag2010). These datasets are publicly available in the FORS database (https://forscenter.ch).

The Swiss Volunteering Survey was carried out in 2006, 2009, 2014, and 2019. As these surveys encompass four distinct samples, they do not represent panel data. However, all four surveys contained the same groups of questions with little variation. The subgroups of questions cover (i) living arrangements, trust, and political attitudes; (ii) segmentation of formal and informal volunteering; (iii) motivation and incentives for volunteering; and (iv) sociodemographic information. The core of each survey contains the same questions, allowing for comparisons at different time points.

From the list of questions on the Swiss Volunteering Survey, we used the variables from all the respondents’ answers to define the constructs in the models (see Annex 1). The data from the surveys sometimes differ in how they were collected (see differences in Annex 1). During processing, we used all the relevant available variables across all the survey data collection (Freitag et al., Reference Freitag, Manatschal, Ackermann and Ackermann2016; Freitag et al., Reference Freitag, Steffen and Bühlmann2006; Lamprecht et al., Reference Lamprecht, Fischer and Stamm2020; Stadelmann-Steffen et al., Reference Stadelmann-Steffen, Traunmüller, Gundelach and Freitag2010), fitting theoretically to the constructs tested in the models. Some variables were not present in all the survey years. Thus, in some cases, the constructs are defined slightly differently.

Methods

To examine the causal relationships between middle-class status and volunteering and to assess the impact of willingness and availability mediated by human and social capital dispositions, we employed structural equation modeling in its partial least squares form (PLS–SEM). This analysis was conducted via selected variables from the Swiss Volunteering Survey dataset (see Annex 1 for details).

The PLS–SEM approach is particularly well suited for research dealing with complex constructs and indirect relationships, as is the case in our study. PLS-SEM is used to analyze latent constructs within a model to uncover causal relationships, including both mediating and moderating effects (for methodological information, see Hair, Hult, Ringle, and Sarstedt (Reference Hair, Hult, Ringle and Sarstedt2014); or Mehmetoglu and Venturini (Reference Mehmetoglu and Venturini2021). In our analysis, we aimed to test the model in Fig. 1.

We classified individuals as volunteers if they had engaged in volunteering activities either within the last four weeks or at any point before that. We created reflective latent variables, represented by ovals, for human capital, time availability, orientation toward society and people, trust, and political engagement. The initial configuration of these constructs is detailed in Annex 1, while the composition following model optimization is outlined in Table 4. Additionally, we integrated two single-item variables, represented as rectangles, into our models: affiliation with the middle class and engagement in formal volunteering.

For our analysis, we used the plssem package in STATA 17 SE (Venturini & Mehmetoglu, Reference Venturini and Mehmetoglu2019) to standardize the variables used as items when estimating latent constructs. This package estimated the model in three steps. First, latent variable scores were iteratively estimated for each latent variable. We used bootstrapping to estimate the reflective latent variables by applying 7,500 iterations for each latent construct with the imputation of missing values (using the k-means nearest neighbor for imputation). This method is well suited for multivariate datasets where missing values occur across several variables. By considering the multidimensional space formed by these variables, k-means nearest neighbor imputation can find the closest set of complete cases to a case with missing values, ensuring a more contextually relevant imputation. Second, we estimated the measurement model parameters (weights/loadings). Third, the package applied regression analysis via the ordinary least squares method to estimate the effects between the variables in the model.

From a systemic perspective, our research reveals that more fundamental changes (with an awareness of the limitations of internal validity to test only separated effects in each dataset) may affect the success of NPOs in attracting middle-class volunteers.

Figure 1 illustrates the overarching structure of our model. The definitions of the latent constructs may vary across the four Swiss Volunteering Survey datasets (see Annex 1 and Annex 2) depending on the available variables and the final configuration of the model being tested.

By comparing data from the four surveys, we identified changes in volunteer engagement over the 2006–2019 period. We employed two operational definitions of the middle class. The first, called the income middle class, delineates three categories on the basis of income: low-income, middle-class, and high-income (as defined in the literature review section). The second definition, employment middle class, combines income with being at least 50% employed. In the second definition, our focus was solely on the influence of the employment middle class on volunteering. This employment-based classification also hints at the presence of five additional social groups beyond the employment middle class, each with unique income and employment characteristics (e.g., individuals with low incomes but stable employment or with middle-class incomes but without stable employment). This comparison enabled us to explore potential shifts in volunteering patterns within Swiss society. The datasets offered a significant advantage due to their large size, ensuring a statistically representative sample of the Swiss population.

Results and Discussion

Descriptive Statistics

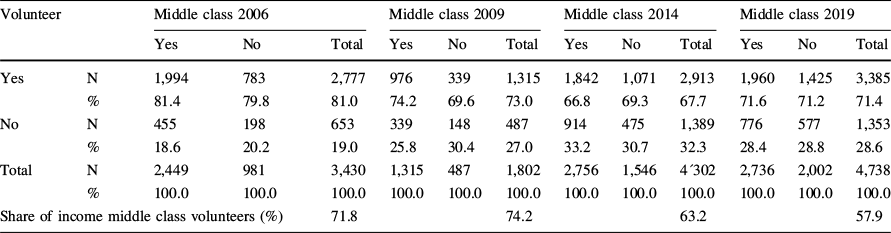

First, we compared the prevalence of volunteering within the income middle class to that in other social classes. Table 3 reveals that the income middle class consistently had higher volunteering rates than did the other classes for most years. The proportion of volunteers from the income middle class decreased from 81.4% in 2006 to 66.8% in 2014 but subsequently increased (a similar pattern as in the UK, Lim & Laurence, Reference Lim and Laurence2015), similar to other classes. Furthermore, the representation of the income middle class within the volunteer group decreased (as indicated in the last row of Table 3) but consistently contributed the majority of volunteers. Samochowiec, Thalmann, and Müller (Reference Samochowiec, Thalmann and Müller2018) attribute the decline in volunteering to technological advancements and societal shifts within Swiss society. For example, work-related commuting distances have increased (as shown in Annex 2), diminishing individuals' connection to their local communities. Conversely, there has been a notable increase in environmental engagement among youth; this aligns with the findings of Chambré (Reference Chambré and M.2020), who notes that volunteering intensity changes over time, usually in response to natural disasters or societal inputs.

Table 3 Comparison of volunteering in the income middle class with other classes.

|

Volunteer |

Middle class 2006 |

Middle class 2009 |

Middle class 2014 |

Middle class 2019 |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Yes |

No |

Total |

Yes |

No |

Total |

Yes |

No |

Total |

Yes |

No |

Total |

||

|

Yes |

N |

1,994 |

783 |

2,777 |

976 |

339 |

1,315 |

1,842 |

1,071 |

2,913 |

1,960 |

1,425 |

3,385 |

|

% |

81.4 |

79.8 |

81.0 |

74.2 |

69.6 |

73.0 |

66.8 |

69.3 |

67.7 |

71.6 |

71.2 |

71.4 |

|

|

No |

N |

455 |

198 |

653 |

339 |

148 |

487 |

914 |

475 |

1,389 |

776 |

577 |

1,353 |

|

% |

18.6 |

20.2 |

19.0 |

25.8 |

30.4 |

27.0 |

33.2 |

30.7 |

32.3 |

28.4 |

28.8 |

28.6 |

|

|

Total |

N |

2,449 |

981 |

3,430 |

1,315 |

487 |

1,802 |

2,756 |

1,546 |

4´302 |

2,736 |

2,002 |

4,738 |

|

% |

100.0 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

|

|

Share of income middle class volunteers (%) |

71.8 |

74.2 |

63.2 |

57.9 |

|||||||||

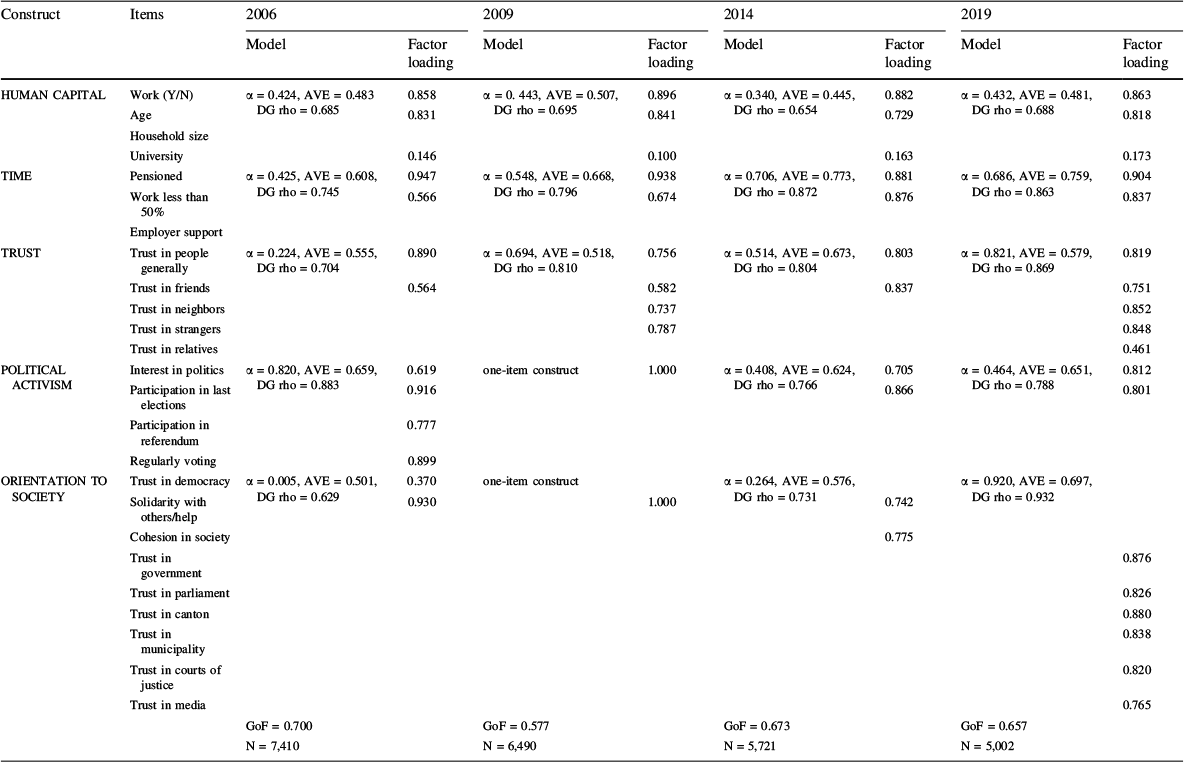

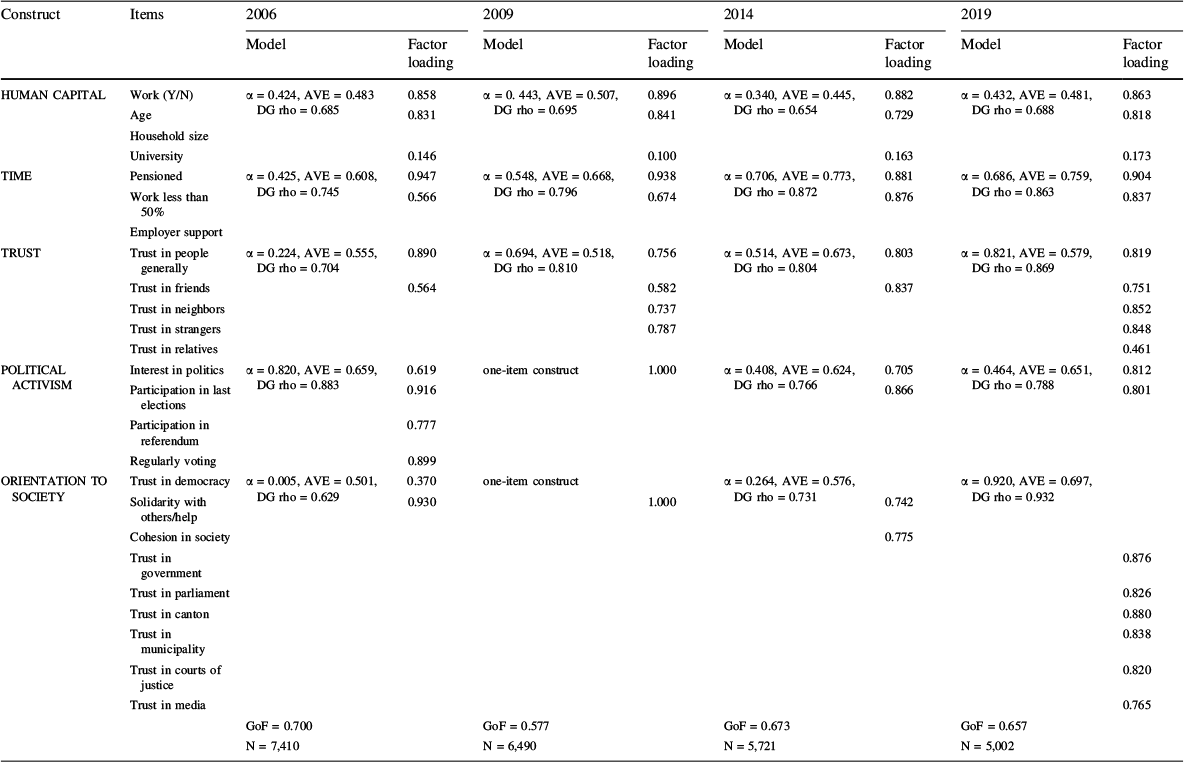

Second, we briefly describe the consistency and reliability of the model constructs. Table 4 shows the variables we used in the constructs and their quality measured via Cronbach's alpha and Dillon–Goldstein's rho. When using Cronbach's alpha, we assumed that all the items were equally important, while this condition was relaxed for Dillon–Goldstein's rho. Additionally, we faced a trade-off between including theoretically justified variables in the models at the cost of weakening the models or focusing on selecting variables with a strong association with the latent constructs, even if a relatively small number remained in the models. We chose the latter approach applied in iterative steps, in which we sequentially eliminated variables with the lowest contribution to the latent variables until the composition of a given latent variable met the basic statistical conditions of PLS–SEM. The exception was university education in the latent construct of human capital. The original list of theoretically justified variables can be compared to the remaining variables in the models in Table 4 and Annex 1 (and Annex 4 for the employment middle class). We dropped most of the items to improve the reliability and validity of the model. In the case of human capital, we left university attainment in the model at the cost of reducing the overall reliability of the model, as we consider education an essential item for defining human capital.

Table 4 Descriptive statistics for the tested models for income middle class

|

Construct |

Items |

2006 |

2009 |

2014 |

2019 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Model |

Factor loading |

Model |

Factor loading |

Model |

Factor loading |

Model |

Factor loading |

||

|

HUMAN CAPITAL |

Work (Y/N) |

α = 0.424, AVE = 0.483 DG rho = 0.685 |

0.858 |

α = 0. 443, AVE = 0.507, DG rho = 0.695 |

0.896 |

α = 0.340, AVE = 0.445, DG rho = 0.654 |

0.882 |

α = 0.432, AVE = 0.481, DG rho = 0.688 |

0.863 |

|

Age |

0.831 |

0.841 |

0.729 |

0.818 |

|||||

|

Household size |

|||||||||

|

University |

0.146 |

0.100 |

0.163 |

0.173 |

|||||

|

TIME |

Pensioned |

α = 0.425, AVE = 0.608, DG rho = 0.745 |

0.947 |

α = 0.548, AVE = 0.668, DG rho = 0.796 |

0.938 |

α = 0.706, AVE = 0.773, DG rho = 0.872 |

0.881 |

α = 0.686, AVE = 0.759, DG rho = 0.863 |

0.904 |

|

Work less than 50% |

0.566 |

0.674 |

0.876 |

0.837 |

|||||

|

Employer support |

|||||||||

|

TRUST |

Trust in people generally |

α = 0.224, AVE = 0.555, DG rho = 0.704 |

0.890 |

α = 0.694, AVE = 0.518, DG rho = 0.810 |

0.756 |

α = 0.514, AVE = 0.673, DG rho = 0.804 |

0.803 |

α = 0.821, AVE = 0.579, DG rho = 0.869 |

0.819 |

|

Trust in friends |

0.564 |

0.582 |

0.837 |

0.751 |

|||||

|

Trust in neighbors |

0.737 |

0.852 |

|||||||

|

Trust in strangers |

0.787 |

0.848 |

|||||||

|

Trust in relatives |

0.461 |

||||||||

|

POLITICAL ACTIVISM |

Interest in politics |

α = 0.820, AVE = 0.659, DG rho = 0.883 |

0.619 |

one-item construct |

1.000 |

α = 0.408, AVE = 0.624, DG rho = 0.766 |

0.705 |

α = 0.464, AVE = 0.651, DG rho = 0.788 |

0.812 |

|

Participation in last elections |

0.916 |

0.866 |

0.801 |

||||||

|

Participation in referendum |

0.777 |

||||||||

|

Regularly voting |

0.899 |

||||||||

|

ORIENTATION TO SOCIETY |

Trust in democracy |

α = 0.005, AVE = 0.501, DG rho = 0.629 |

0.370 |

one-item construct |

α = 0.264, AVE = 0.576, DG rho = 0.731 |

α = 0.920, AVE = 0.697, DG rho = 0.932 |

|||

|

Solidarity with others/help |

0.930 |

1.000 |

0.742 |

||||||

|

Cohesion in society |

0.775 |

||||||||

|

Trust in government |

0.876 |

||||||||

|

Trust in parliament |

0.826 |

||||||||

|

Trust in canton |

0.880 |

||||||||

|

Trust in municipality |

0.838 |

||||||||

|

Trust in courts of justice |

0.820 |

||||||||

|

Trust in media |

0.765 |

||||||||

|

GoF = 0.700 N = 7,410 |

GoF = 0.577 N = 6,490 |

GoF = 0.673 N = 5,721 |

GoF = 0.657 N = 5,002 |

||||||

Reliability measures (α = Cronbach’s alpha, DG rho = Dillon-Goldstein’s rho); AVE = Average Variance Explained; GoF = Relative Goodness of Fit; see Annex 4 for results for the middle class defined by income and sound employment

The reliability of the constructs was reasonable. In only five of 18 cases was Dillon–Goldstein's rho below 0.7 (see Table 4, and five of 18 for the employment middle class in Annex 1), whereas Cronbach's alpha was almost always below the threshold of 0.7. Accordingly, we did not assume that all the items were equally important, whereas Dillon–Goldstein's rho confirmed the reliability of the constructs under the condition of unequal importance of the items (Mehmetoglu & Venturini, Reference Mehmetoglu and Venturini2021).

Information on the average variance captured by the construct in its associated items (AVE) was higher than the required value of 0.5 in 11 of 18 constructs (one of those did not fit the requirement, as a university degree was included as an item within them, and three of 18 for the employment middle class model). The models achieved acceptable values of the relative goodness of fit (one quarter were above 0.7 for the middle-class income model but were always almost 0.7; three models met the requirements for the middle-class employment model).

Role of Human Capital in Volunteering

We demonstrated that human capital and employment are crucial in influencing both middle-class status and volunteering rates. The effect of human capital on time availability was partly negative in our analyses for the income middle class (where employment was not a factor in defining human capital), as was the case for the employment middle class; this suggests that individuals with greater human capital tend to work more, resulting in less free time. Our models supported this, showing that employment and age (as a proxy for experience) were significant contributors to the human capital latent variable (see Table 4 for the income middle class and Annex 1 for the employment middle class). This observation aligns with research on how unemployment can lead to diminished interest in social activities and a sense of stigmatization (see Dougherty et al., Reference Dougherty, Rick and Moore2017; Lobo, Reference Lobo2018). Human capital highlights the significance of experience, represented by the variable age. In the model addressing income middle-class affiliation, age and stable employment emerged as key factors supporting this affiliation (see Tables 4 and 5). Generally, individuals within the middle class possess significant human capital.

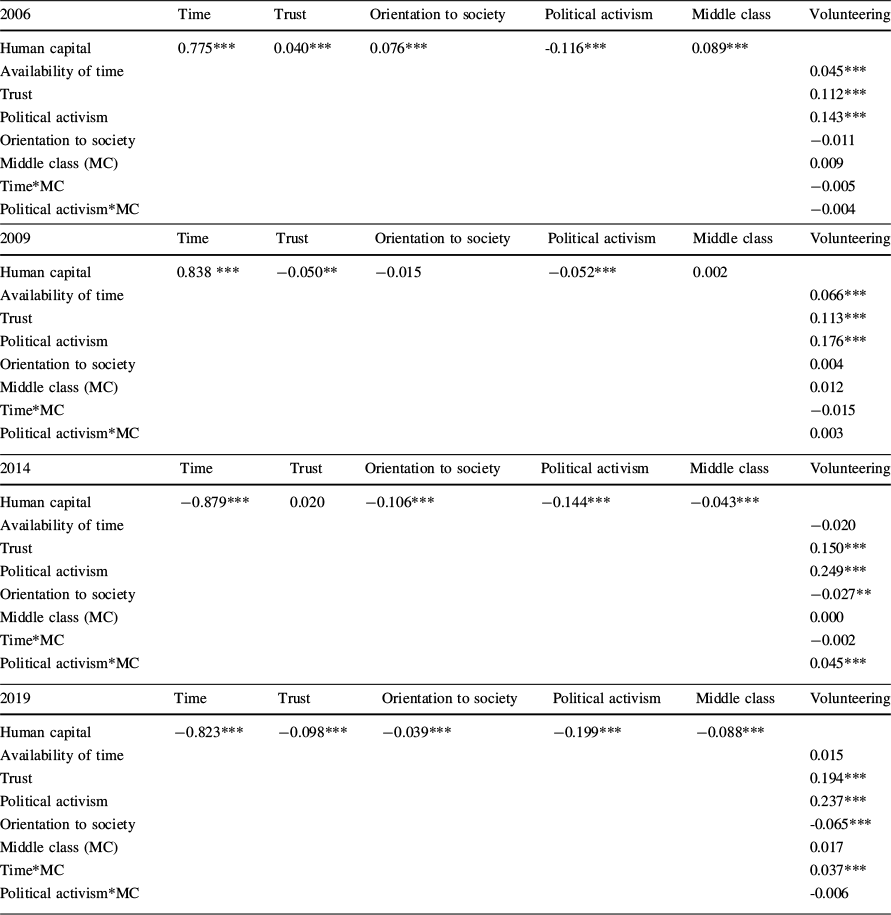

Table 5 Estimates of the effects of latent constructs on volunteering (income middle class)

|

2006 |

Time |

Trust |

Orientation to society |

Political activism |

Middle class |

Volunteering |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Human capital |

0.775*** |

0.040*** |

0.076*** |

-0.116*** |

0.089*** |

|

|

Availability of time |

0.045*** |

|||||

|

Trust |

0.112*** |

|||||

|

Political activism |

0.143*** |

|||||

|

Orientation to society |

−0.011 |

|||||

|

Middle class (MC) |

0.009 |

|||||

|

Time*MC |

−0.005 |

|||||

|

Political activism*MC |

−0.004 |

|

2009 |

Time |

Trust |

Orientation to society |

Political activism |

Middle class |

Volunteering |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Human capital |

0.838 *** |

−0.050** |

−0.015 |

−0.052*** |

0.002 |

|

|

Availability of time |

0.066*** |

|||||

|

Trust |

0.113*** |

|||||

|

Political activism |

0.176*** |

|||||

|

Orientation to society |

0.004 |

|||||

|

Middle class (MC) |

0.012 |

|||||

|

Time*MC |

−0.015 |

|||||

|

Political activism*MC |

0.003 |

|

2014 |

Time |

Trust |

Orientation to society |

Political activism |

Middle class |

Volunteering |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Human capital |

−0.879*** |

0.020 |

−0.106*** |

−0.144*** |

−0.043*** |

|

|

Availability of time |

−0.020 |

|||||

|

Trust |

0.150*** |

|||||

|

Political activism |

0.249*** |

|||||

|

Orientation to society |

−0.027** |

|||||

|

Middle class (MC) |

0.000 |

|||||

|

Time*MC |

−0.002 |

|||||

|

Political activism*MC |

0.045*** |

|

2019 |

Time |

Trust |

Orientation to society |

Political activism |

Middle class |

Volunteering |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Human capital |

−0.823*** |

−0.098*** |

−0.039*** |

−0.199*** |

−0.088*** |

|

|

Availability of time |

0.015 |

|||||

|

Trust |

0.194*** |

|||||

|

Political activism |

0.237*** |

|||||

|

Orientation to society |

-0.065*** |

|||||

|

Middle class (MC) |

0.017 |

|||||

|

Time*MC |

0.037*** |

|||||

|

Political activism*MC |

-0.006 |

Significance levels: *p < 0.1, **p < 0.05, ***p < 0.01. Results for middle class defined by income and sound employment are reported in Annex 5

In our models, the impact of human capital on volunteering was indirect, mediated by the availability of resources (such as time), an orientation toward others and society, and trust in people (which influences the willingness to volunteer). The analysis confirmed the direct and positive effect of time availability on volunteering for both models (see the income middle class model in Table 5, although in the case of the employment middle class, there was only one positive and significant estimation, while the others were negative but insignificant).

From this viewpoint, it is understandable why nonprofit organizations (NPOs) target potential volunteers from the middle class, who are perceived to possess high human capital (Dean, Reference Dean2016, Reference Dean2021). These individuals typically have resources at their disposal. NPOs seek support not only in the form of charitable donations but also through volunteering. However, for the middle class, time is a scarce resource. Individuals with greater human capital and stable employment usually have adequate financial means (confirmed by the review of Wiepking & Bekkers, Reference Wiepking and Bekkers2012) but face time constraints due to work obligations. This finding aligns with other studies that explore the availability of both income and time (e. g., Grizzle, Reference Grizzle2015); thus, it was confirmed that the predominant barrier to volunteering is the absence of time (Haski-Leventhal et al., Reference Haski-Leventhal, Meijs, Lockstone-Binney, Holmes and Oppenheimer2018; Sundeen et al., Reference Sundeen, Raskoff and Garcia2007). To gain more time, people can better organize their daily schedules. NPOs can help potential volunteers with time management. However, mutual trust needs to be built for such a concept to be successful (we discuss trust in the next section).

Social Capital and Volunteering

We identified a strong link between trust and volunteering engagement, highlighting its critical role in fostering social capital and encouraging generosity. Specifically, our findings indicate a positive relationship between trust and the likelihood of volunteering among individuals across all the examined datasets (see Table 5 and Annex 5). This finding underscores the pivotal role of trust in building social capital and promoting altruistic behavior (Brown & Ferris, Reference Brown and Ferris2007; Chambré, Reference Chambré and M.2020).

Moreover, our research underscores the importance of trust in promoting volunteer involvement, establishing it as a cornerstone of social capital, in line with Putnam (Reference Putnam1993, Reference Putnam2000) and Brown and Ferris (Reference Brown and Ferris2007). This concept includes widespread trust in both fellow citizens and institutional structures (Hollenstein, Reference Hollenstein2013, p. 46; Kneidinger, Reference Kneidinger2010, p. 25).

Our findings across both middle-class definitions confirm that social capital related to trust involves the extent to which individuals trust not only those close to them, such as friends, family, and neighbors (similarly to Lim & Laurence, Reference Lim and Laurence2015), but also strangers; it also involves the frequency of social interactions and the degree to which individuals are open, communicative, and welcoming in engaging with others. This finding has implications for increasing volunteering for NPOs, suggesting the importance of building trust. It especially concerns local neighborhoods, where such activities have a better chance of success in building resilient communities (see the role of philanthropy in identifying social problems and addressing them in Brown & Ferris, Reference Brown and Ferris2007).

The decline in general trust in institutions in Switzerland during the latter half of the 2010s (gfs.bern, 2019, p. 15) suggests that as confidence in institutions wanes, people may increasingly rely on personal relationships and local communities for trust and support (trust in institutions in the construct orientation toward society dropped out in samples from 2006, 2009, and 2014). This shift aligns with the notion that trust in familiar individuals is greater than that in strangers (Bleck et al., Reference Bleck, Bonan, Lemay-Boucher and Sarr2024; Karashiali et al., Reference Karashiali, Konstantinou, Christodoulou, Kyprianidou, Nicolaou, Karekla and Kassianos2023) and institutions, although trust in institutions is often linked to overall trust in people (Sønderskov & Dinesen, Reference Sønderskov and Dinesen2015).

Our findings concerning the influence of orientation toward society on volunteering were mixed. Most of the estimates for these effects on volunteering were not statistically significant, and the direction of these effects varied across the datasets (see Table 5 and Annex 5 for details).

The other items related to societal orientation had a minimal impact on the latent variable of orientation toward society for both the income and employment middle class.

Our results, therefore, emphasize the critical role of the willingness to volunteer and particularly the significance of trust. Our findings on individual approaches to helping others, especially trust in others, confirmed previous research in this field (Ackermann, Reference Ackermann2019; Einolf & Yung, Reference Einolf and Yung2018; Shantz et al., Reference Shantz, Saksida and Alfes2014).

Political engagement emerged as a strong, direct predictor of formal volunteering. In all the datasets examined, its association with formal volunteering was positive and significant, underscoring the tendency for activists to collaborate within associations and contribute to formal volunteering efforts. Interest in politics was a particularly strong driver of active participation.

Middle Class and Volunteering

We did not directly confirm H1, regarding whether belonging to the middle class increases the likelihood of becoming a volunteer. The findings were statistically inconclusive, albeit trending positively for the income middle class, and remained ambiguous for the employment middle class. Nonetheless, the data consistently showed a positive trend across all years for the income middle class and in half of the assessments for the employment middle class (these results were very similar to those of Korndörfer et al. (Reference Korndörfer, Egloff and Schmukle2015), who note that the negative effect of social class on prosociality may not be as robust as expected).

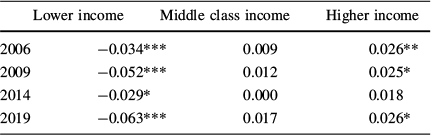

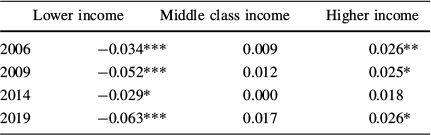

To explore H1 indirectly, we extended our analysis by including other socioeconomic groups. The comparison detailed in Table 6 juxtaposes volunteer participation rates between the income middle class and other classes. These findings align with the theoretical perspective that lower-income groups possess less human capital and are less involved in volunteering activities, whereas higher-income groups, with more human capital, participate more actively in volunteering (Dean, Reference Dean2016, Reference Dean2021; Hustinx et al., Reference Hustinx, Grubb, Rameder and Shachar2022; Korndörfer et al., Reference Korndörfer, Egloff and Schmukle2015; Seabe & Burger, Reference Seabe and Burger2022). Moreover, as Lim and Laurence (Reference Lim and Laurence2015) note, in societies with a concentration of less wealthy people, there is a lack of institutional infrastructure for volunteering.

Table 6 Comparison of volunteering across societal classes

|

Lower income |

Middle class income |

Higher income |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

2006 |

−0.034*** |

0.009 |

0.026** |

|||

|

2009 |

−0.052*** |

0.012 |

0.025* |

|||

|

2014 |

−0.029* |

0.000 |

0.018 |

|||

|

2019 |

−0.063*** |

0.017 |

0.026* |

|||

Significance levels: *p < 0.1, **p < 0.05, ***p < 0.01

The analysis underlines the significant role of the income middle class in volunteering. For individuals with lower incomes, the estimates were consistently negative and significant across all the datasets, indicating less involvement in volunteering. In contrast, the results for high-income individuals were mixed: positive in three datasets but negative in one, suggesting that while income level is a crucial factor in volunteer engagement (Dawson et al., Reference Dawson, Baker and Dowell2019) within the income middle class and lower-income groups (Dean, Reference Dean2016, Reference Dean2021; Hustinx et al., Reference Hustinx, Grubb, Rameder and Shachar2022; Seabe & Burger, Reference Seabe and Burger2022), the relationship between higher income levels and volunteering compared with the rest of the population remains uncertain (Eimhjellen, Reference Eimhjellen2022).

The influence of the income middle class on formal volunteering across all four periods was modest but showed an increasing trend in volunteering rates, increasing from 0.009 in 2006 to 0.017 in 2019, although it decreased in 2014.

Comparing results across different definitions of the middle class revealed an intriguing observation: the likelihood of volunteering was greater among the income middle class than among the employment middle class. This finding suggests that individuals with a middle-class income level who are not heavily engaged in employment are more likely to volunteer, likely because of greater availability of time and resources.

With respect to Hypothesis H2, which concerned the moderating effect of political engagement within the middle class on volunteering, the estimations provided mixed results for the income middle class, whereas nearly all the tests indicated a negative moderating effect of the employment middle class, suggesting that politically engaged middle-class individuals are less inclined to volunteer, although these findings are not statistically significant. This inconclusive result neither confirms nor rejects the expectation that the expected empowered middle class tends to express its political will and involvement in political activism (see Bolton, Reference Bolton2015, p. 24; Rimmerman, Reference Rimmerman and A.2011, p. 28).

For Hypothesis H3, concerning the moderating effect of time availability within the middle class on volunteering, the estimates for both definitions indicated that the middle class is less likely to volunteer, despite the lack of statistical significance.

Conclusions

In our research, we aimed to answer the following questions: how important is the middle class to volunteering in Switzerland, and did the engagement of the middle class in volunteering change over time?

Our study contributes to the understanding of volunteering in three ways. First, the middle class is an essential source of formal volunteers compared with other social classes. Although the share of volunteers from the middle class decreased over the 14 years covered by the surveyed samples, more than half of Swiss volunteers still belong to this class. Moreover, most estimates of the effect of belonging to the middle class on volunteering are positive (although statistically insignificant).

The second aspect highlights the role of the middle class in volunteering compared with other classes. The importance of the middle class is evident, especially in comparison with people with lower income; the estimates of lower-income individuals' contribution to volunteering were consistently negative.

Our results reveal a positive, though insignificant, relationship between the middle class and volunteering. The main reason for this result is the defining factor in the middle class—having a good job that limits one’s time to volunteer. Nevertheless, middle-class individuals can organize their schedules to free up at least some time. NPOs may be advised to help potential volunteers organize their schedules. Thus, the training of volunteers might be accompanied by time management programs to help volunteers better organize their available time.

Third, among the key factors influencing the availability and willingness of the middle class to volunteer is trust. Trust increases people’s likelihood of becoming volunteers. This factor is a constant in the role of the middle class in volunteering. Thus, NPOs and other stakeholders that collaborate with volunteers should invest in building trust among people, which will increase rates of volunteering in the long term. The second contributing aspect is political engagement, which concerns primarily organizations that are actively involved in advocacy and have a greater chance of attracting volunteers when asking them to engage.

We are aware of the limitations of our research. We tested volunteering in four periods, but the same set of variables used to construct latent variables was not available for all of them. This issue mainly concerns the latent variables of orientation toward others and society. Although we suppressed some of the items when optimizing the validity of the models, the models in four years would still need to apply the same items in the constructs all the time.

The second issue concerns the definition of belonging to the middle class. We used two definitions that helped us apply the same approach to all four data samples and distinguish the middle class defined based on income only from the middle class defined by a combination of income and employment. However, the income categories did not precisely follow those used in theoretical definitions of the middle class. Thus, further research should aim to precisely define the middle class and its relationship with volunteering through resources and collecting panel data, as our research is based on four separate datasets.

As our datasets covered up to the year 2019, we see the potential for further research on the consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic on formal volunteering. Research has shown that many people volunteered informally and spontaneously during the lockdown phase of the pandemic. Nevertheless, the question is how the pandemic influenced the long-term willingness to volunteer, especially in a formal setting. Given the analysis by Trautwein et al. (Reference Trautwein, Liberatore, Lindenmeier and von Schnurbein2020), satisfaction with crisis volunteering led to a greater willingness to volunteer long-term. This finding confirms the changing landscape of volunteering described by (Chambré, Reference Chambré and M.2020) but needs more elaboration to determine whether it is sustainable in the long term.

A second avenue for further research is a more detailed analysis of the volunteer engagement of the middle class. Our approach to defining the middle class is limited by the available data. Thus, better sociodemographic information could help in the development of a more robust framework.

The third potential future research area concerns the relationship between formal and informal volunteering across social classes.

Finally, we call for research on the different forms of volunteering, such as cyber- or episodic volunteering. These new forms are becoming increasingly important but need to be fully covered by conventional questionnaires on volunteering.

Funding

Open access funding provided by University of Basel. Freiwillige Akademische Gesellschaft