1. Introduction

Who has the authority to create money in the United States? At first glance, the answer is simple: Article I of the US Constitution grants Congress the power to “coin money and regulate its value.” In practice, however, Congress has often relinquished this responsibility, outsourcing monetary authority to private banks and shareholders.Footnote 1 One has to look no further than the Civil War and Reconstruction to see this outsourcing at play: while the Civil War took the Union off the domestic gold standard and onto a fiat money system, by the end of the 1870s, the United States was back on the gold standard and had created a new system of nationally chartered banks to help augment the money supply and cheaply finance government debt. In doing so, the United States had created an early version of its hybrid public–private monetary system—one in which private banks issued money secured by public debt.Footnote 2 These shifts were not only controversial, but they also had important effects on the American economy. The ensuing Gilded Age era was marked by frequent banking panics that threatened to bring down the broader economy.Footnote 3

While economists, historians, and legal scholars have written extensively on the origins of money creation, political scientists, outside of a handful of works in American Political Development (APD), have neglected the topic.Footnote 4 This is surprising in part because our current era has seen the resurgence of political debate on the nature and origins of money, as a variety of new forms of digital cryptocurrencies have exploded in popularity and as core institutions like independent central banks have come under attack.Footnote 5 However, this resurgence in popular interest in money should not be treated as an aberration. Monetary debates for much of US history were not esoteric conversations among economists in Washington, DC, and elite universities. Instead, they were the driving force for popular political movements such as those led by William Jennings Bryan and the western populists who fought to minimize concentrated financial power, monetize silver, and end the deflation (decline in prices) created by the gold standard. The debates over these different forms of money became deeply ingrained in our popular culture, whether we realize it or not. Other authors have noted the striking similarities between the Western populists’ struggle over monetary policy in the late nineteenth-century and the symbols in L. Frank Baum’s The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, written in 1900: a pair of powerful silver slippers (later changed to ruby), a yellow (seemingly golden) brick road, an emerald (green) city housing the levers of power, all situated amidst a grand conflict between eastern and western powers.Footnote 6

The underlying conflict in these debates—the conflict over the authority to create money—is related to a central theme in APD: the expansion or reduction of public authority.Footnote 7 Those who supported expanding federal greenbacks (fiat money), for example, sought to establish democratic, public authority over the money supply, while “goldbugs” sought to tie the hands of government and cede monetary control to banks and financial institutions.Footnote 8 From that vantage point, I seek to answer two main questions about the period that have not been fully resolved by existing scholarship: (1) Why did the United States return to the gold standard in 1879? (2) Why did the subsequent public–private monetary system lead to monetary instability and crisis? After detailing the limits of existing scholarship, I offer my own theory, called “Elite Entanglement,” which integrates both state-centered and business power theories to explain monetary outsourcing and financial instability. In applying this APD lens to monetary policy debates, I seek to encourage political science scholarship to think of monetary policy in political terms—as societal conflicts involving the power to create money.

There is a substantial disjuncture between scholarship on Civil War and Reconstruction monetary policy. Existing scholarship sees Civil War monetary policy as mostly a function of Republican Party state-building: both the issuance of federal greenbacks and the new National Bank system were examples of state expansion either through direct monetary issuance or, in the latter’s case, a way to help the federal government borrow cheaply while simultaneously federalizing banking policy.Footnote 9 Within Reconstruction scholarship, though, the predominant political science model for understanding monetary policy voting is the model of economic development.Footnote 10 Bensel (1991) finds that more economically “developed” areas—especially the capital-rich Northeast, which held high concentrations of financial interests—were more likely to support government retrenchment from monetary policy and the return to the gold standard.Footnote 11 However, as I detail in this paper, while the economic development model can explain Congressional voting in the early phase of Reconstruction, it cannot explain the voting on the act that returned the United States to the gold standard, the Resumption Act of 1875.Footnote 12 Republicans, after years of being split internally on monetary policy votes geographically, were able to negotiate a deal that perpetuated the national bank system while also returning the United States to the gold standard.

That there are different interpretations of Civil War and Reconstruction monetary policy is not inherently problematic. However, I argue that we can better understand this puzzle—why voting on the return to the gold standard did not follow the economic development model—by fusing the dominant approaches found in each period. To do that, I introduce the theory of “Elite Entanglement.” In short, Elite Entanglement argues that American financial institutions have been shaped not only by the preferences of financial elites but also by the state’s fiscal imperatives. More specifically, the theory details how the confluence of the state’s interests in cheap finance, along with financial elites’ interests in debt monetization, has produced fragile financial systems that have been harmful to the American public. While most political science approaches emphasize the role that private interests play in encouraging deregulation and outsourcing, the theory of Elite Entanglement argues that scholars must also consider the state’s interests in cheap financing to properly understand the historical construction of the United States’ monetary system. While private financial interests play a role in curtailing state growth and lobby to maintain their infrastructural role in money creation, these interests are not sufficient to explain new forms of money.Footnote 13 Instead, the state’s interest in cheap financing leads to the creation of public–private monetary systems, which allow for the private creation of money in exchange for cheap public debt.

Key to this explanation is the creation of the national bank system in 1863: a hybrid, public–private monetary regime created as a way to replace more direct forms of state expansion, such as federal greenbacks. The national bank system played a key role in both centralizing the banking system of the United States and providing the government with cheap borrowing during wartime. While the national bank system had “arisen to serve the state,” the institutional connections to the Republican Party that were forged at its creation had important downstream political consequences.Footnote 14 Most importantly, the national bank system acted as a bridge between a party that was heavily divided along economic lines, with one pro-statist faction and another antistatist faction. I argue that the way Republicans were able to negotiate the agreement to return to the gold standard across levels of economic development was through the perpetuation (and expansion) of the national banking system. This compromise in the Resumption Act of 1875 between the two factions was made possible because the national bank system was an outsourced form of state expansion, satisfying both wings of the party. Midwestern and Southern Republicans could claim to have signed a bill that would expand the currency, and Northeastern Republicans could claim to have signed a bill that would return the United States to the gold standard.

However, as I detail, this Republican compromise had important effects on the financial system. Because government debt underpinned national banknote issuance, and because the return to the gold standard limited the quantity of public debt available, banks began to rely more heavily on deposit creation, which was highly fragile and susceptible to bank runs in moments of low confidence. The switch from national banknotes to bank deposits (both state and national banks) created the fragile Gilded Age financial system. I next provide an overview of these different forms of money and their effects on the financial system, and further detail the theory of Elite Entanglement.

2. Defining money and specifying the theory

One reason for the lack of work on this subject in political science is related to its inherent complexity. Monetary debates are confusing and require a high level of technical expertise. Most people in the present era may not even be familiar with the notion that there are different forms of money, public and private. Yet this diversity in money was plain to see for those who lived in nineteenth-century America. In fact, most of the money handled by everyday Americans was privately issued money—banks issued their own notes (called “banknotes”) which could be redeemed for hard currency like gold. Yet as detailed later in this article, the federal government stepped in at various points in US history, such as the Civil War, to issue its own public money (called “greenbacks” in this era). Lastly, there were also hybrid “public–private” forms of money, such as national banknotes. National banknotes were created by private banks but only through the purchase of federal government bonds, which guaranteed their value. Which sector, public or private, or both, had the authority to create money was a key point of contestation. Policymakers were aware of these distinctions in the origins of money, with some defending public money creation and others defending private money creation. Some, like Senator John Sherman, eventually defended these hybrid forms of public–private money, arguing, “the public faith of a nation alone is not sufficient to maintain a paper currency.”Footnote 15

To simplify these different forms of money, I have adapted a 2 × 2 typology from Pozsar (2014) and Murau (2017) (Table 1).Footnote 16 The left half of Table 1 represents “public credit money,” where the primary issuer or backer is the state, and the right side of Table 1 represents “private credit money,” where the issuer is a private entity, sometimes with public assets as collateral and sometimes not. Starting from the top left, pure public money is the money issued by a public institution. This could include both specie (gold or silver) or fiat notes like federal greenbacks. The top right corner of Table 1 describes “public–private money,” which is issued by private institutions, and while it is not backstopped by a public institution explicitly, it uses public assets (e.g. government debt) as collateral.Footnote 17 As I describe in more detail later, national banknotes with government securities as collateral fit this form of money. Lastly, in the bottom right corner, there is “pure private money,” which refers to monetary claims issued by a private institution with private assets as collateral—for example, state banknotes or deposits, or national bank deposits in the Gilded Age. Scholars have noted that pure private money, because it is issued with private assets as collateral, has the potential to be unstable.Footnote 18 A drop in the value of the private assets underpinning the deposit issuance can create the conditions for a bank panic or run.

Table 1. Typology of Money

The theory of Elite Entanglement describes the political-economic process of the changes in these forms of money during the Civil War and Reconstruction and is broken down into four main parts: state expansion, outsourcing, fiscal retrenchment, and financial destabilization.Footnote 19 Through these four processes, I detail how key American financial institutions were shaped by both the preferences of financial elites as well as the state’s fiscal imperatives.

In phase one of the theory, a fiscal crisis prompts the state to expand its authority over economic exchange by printing money (creating “pure public money” like federal greenbacks).Footnote 20 At this stage, financial interests prefer that the government borrow, and they pressure the state to return to borrowing and to borrow at market prices. Despite this pressure, the state seeks to maintain cheap borrowing in whatever way possible, as the crisis conditions demand high state spending for survival. To maintain cheap borrowing despite ceasing to issue pure public money, the state fragments the financial system through the creation of a new public–private monetary system in which private actors create money and use public debt as collateral. Basing private note issuance on the purchase of public debt increases the market for government debt, driving down its price. The result is that the state ceases to issue pure public money, but through its new public–private monetary system, it gains access to cheap borrowing. This “entanglement” between state and financial elites has important downstream political and economic consequences.

Post-crisis, stability in the government debt market becomes essential as a drop in the value of government debt now threatens the new public–private monetary system because public debt acts as the collateral for note issuance. Maintaining the value of government debt encourages fiscal retrenchment and austerity, providing ample fiscal space post-crisis. At this point, cheap borrowing is no longer tantamount to state survival, and voting on monetary policy is driven primarily by economic interests instead of state imperatives. However, the public–private monetary system built during the crisis remains in place. Over time, fiscal retrenchment provokes a class-based fracture within political parties and produces economic instability.Footnote 21 In response to this economic instability, party leaders leverage the public–private monetary system to resolve intercoalitional disputes, further linking private benefit with public debt. Over time, if the total amount of public assets declines, public–private money is replaced with pure private money, which can destabilize the financial system. I next describe these steps in the context of the Civil War and Reconstruction before reviewing in more detail existing literature.

To meet the fiscal crisis of the Civil War, the Union printed nearly $450 million worth of federal greenbacks. This forced the United States off the international gold standard and onto a fiat money standard. As federal “greenbacks” were liabilities of the US Congress (had to be accepted for taxes), they were pure public money and represented a form of state expansion. Yet Congress faced frequent opposition from entrenched financial elites over the issuance of greenbacks. After three separate issuances of greenbacks by Congress, Treasury Secretary Salmon Chase devised a new fiscal strategy. While most state bankers preferred that Congress return to the old system of government borrowing from state banks, Chase crafted a plan to create a new national banking system. The proposal would create a new system of federally chartered banks that could issue uniform national banknotes secured only by the purchase of federal government debt.

With the aid of the lobbying of financial interests with preexisting ties to government finance, such as Henry and Jay Cooke, who were instrumental in convincing Congressional Republicans like John Sherman to support the act, the National Bank Act was passed in February of 1863. There were no more issuances of greenbacks after its passage. By connecting banknote issuance to lending to the government, this increased demand for government debt, which would drive down government borrowing costs at a crucial time in the war.Footnote 22 In effect, the United States had outsourced money creation to private entities through the creation of a public–private monetary system. While certain financial interests helped pressure legislators into supporting the new banking system, the state’s interest in cheap borrowing played a central role in the creation of the new system.

At the end of the war, 66.1 percent of war spending had been financed by loans, 20.1 percent by tax revenue, and 13.8 percent by greenbacks.Footnote 23 Because so much of war spending had been financed by loans from the national bank system, the nation’s monetary system now partially depended on the value of government debt. The stability (and appreciation) of the government debt market, as well as a return to the gold standard, became a priority in the early phase of Reconstruction. Both goals required fiscal retrenchment, maintaining government surpluses (higher taxes than spending), and diminishing the money supply. Retrenchment during the early phase of Reconstruction was primarily supported by the capital-rich Northeast and was not a particularly partisan issue.Footnote 24 Over time, though, federal retrenchment had a few major effects on the Reconstruction economy: (1) the declining availability of federal bonds pushed investors, such as Jay and Henry Cooke, to private speculation in railroad bonds, and (2) as federal spending decreased on noninterest-based expenses, government support for major infrastructure projects like railroads dried up. Looking to replace lost revenue from government debt, the new national bank of Jay and Henry Cooke invested heavily in the Northern Pacific Railway. Yet the Northern Pacific, which had built lines far in advance of actual settlement, went bankrupt in 1873. The collapse of the Northern Pacific triggered the collapse of the Cookes’ bank, bringing down with it the broader economy.Footnote 25

The political response to the Panic of 1873 was far from straightforward: the Republican Party remained split on monetary policy issues across areas of high and low economic development. The Northeast preferred a quick return to the gold standard, while the Midwest and South preferred maintaining a more flexible greenback standard. After nearly a year of internal party warring over the money issue, the Republican Party struck a compromise in 1874 and 1875 that resulted in the return of the gold standard with the expansion of the national bank system. Unlike previous voting on monetary policy in Reconstruction, the Resumption Act of 1875 was a party-line vote across levels of economic development and thus cannot be explained by the economic development model. The national bank system was key to this compromise, both economically and politically: first, with declining government revenue from the depression, the US Treasury did not have enough gold to commit to resumption. The government would have to go back to the bond market to borrow in order to build gold reserves, and the expansion of the national bank system would play a key role in enabling that cheap borrowing.Footnote 26 Second, eliminating the limits on the national bank currency helped unify the party politically as it gave the less economically developed but pro-statist wing of the Republican Party justification for voting for the Resumption Act.Footnote 27

While politically appealing, this Republican compromise increased financial instability. The return to the gold standard prevented the United States from running persistent fiscal deficits. Yet because national banks relied on the purchase of federal government debt, over time, most national banks switched to issuing bank deposits instead. Deposits were not backed by government debt and had a destabilizing effect on the financial system.

These processes—state expansion, outsourcing, fiscal retrenchment, and financial destabilization—are overlaid onto the monetary typology presented above and shown in Table 2 below. As can be seen in the table, these processes result in a switch from pure public money to public–private money to pure private money over time. Lastly, Figure 1 below shows the actual changes in these various money forms as a percentage of the money stock from 1860 to 1890. As the Figure shows, state expansion in the early phase of the Civil War led to an increase in pure public money through the creation of federal greenbacks, and the commensurate decline in pure private money as a percentage of the total money stock. However, with the creation of the national bank system in 1863, public–private money began to grow, reaching nearly 20 percent of the money stock by 1865, while the quantity of pure public money (greenbacks and gold) declined. However, as state retrenchment occurred throughout the 1870s and 1880s—most notably with the return of the gold standard in 1879—public forms of money (both pure public and public–private), diminished in favor of pure private money forms. Private bank deposits again became the dominant monetary instrument in the US economy in the Gilded Age. Bank deposits, because they lacked any connection to public collateral, were relatively fragile and played a key role in the financial instability common in the Gilded Age. Deposits only gained public protection after a series of severe bank runs crippled the broader economy during the Great Depression. I next provide a broader review of existing literature, followed by an overview of my data and methods for this article, before presenting the empirical findings.

Figure 1. Composition of Public and Private Money, 1860–1890.Footnote 34

Table 2. Elite Entanglement in the Civil War and Reconstruction

3. Existing literature

Existing scholarship on fiscal, monetary, and banking policy in the Civil War finds that the Republican Party played an important role in centralizing state authority.Footnote 28 Bensel (1991) highlights that with the secession of the South and the outbreak of the war, the Republican Party took over state functions to such a degree that the state and the Republican Party were “essentially the same thing.”Footnote 29 The influence of private interests in guiding Civil War economic policy within the Republican Party has received less attention, though some emphasize the influence of financial elites on banking policy.Footnote 30 Scholars also note how state expansion resulted from the diminished structural power of traditionally powerful economic actors, such as those in the financial industry.Footnote 31

In work on Reconstruction, most scholars attempt to answer why the US abandoned state expansion efforts from the Civil War in returning to the gold standard in 1879. Explanations are more diverse than scholarship on Civil War economic policy and range from the development of “sectionalism” and regional competition within parties, to the material interests of financiers and manufacturers in the highly developed Northeast, to voter ignorance and autonomous elite action, to the role of ideas among policymakers.Footnote 32 Of particular importance for APD scholarship, Bensel (1991) argues that highly “developed” areas—areas with high levels of manufacturing and financial resources and interests primarily—were instrumental in attaining state retrenchment and the return to the gold standard. Bensel (1991) and Sanders (1999) also emphasize how agricultural areas, especially in the Midwest and South, were much more likely to be sympathetic to greenbacks and to going off the deflationary gold standard.Footnote 33 However, Bensel (1991) does not test the votes during the period of 1874–1875, in which the actual voting on returning to the gold standard occurred.Footnote 35 If Bensel’s (1991) theory of economic development in predicting state retrenchment in monetary policy is correct, we would see that highly developed areas (mostly the wealthy Northeast) would support the return to the gold standard, while the less developed Midwest and South would oppose the return to the gold standard.

Other accounts emphasize international factors. The predominant approach within International Political Economy (IPE) scholarship on Reconstruction monetary policy is the “open economy” model.Footnote 36 In short, Frieden (2014) argues that domestic interest groups’ positions on monetary policy were determined by their position in an international “open” economy. For example, those interests that favored a stable exchange rate (“internationally oriented commercial and financial interests” such as merchants and financial institutions) would have preferred a gold standard as opposed to a fluctuating exchange rate dependent on fiat money.Footnote 37 Frieden (2014) also notes that some manufacturing interests had a different view. Producers that faced little import competition and were primarily focused on domestic trading, such as farmers and those in the iron and steel industries, would have preferred a more flexible exchange rate.Footnote 38 Other manufacturing interests, such as New England textile manufacturers in cotton and wool, were more supportive of the return to the gold standard. This was because the textile industry in the United States had been around much longer and was much more developed in international markets than the more nascent iron and steel industries. Furthermore, because of their heavy reliance on international trade, they preferred a more stable exchange rate.Footnote 39

Alternative “realist” IPE approaches, which emphasize the power of hegemonic nations in the international political system, have less explanatory power in the period according to existing literature.Footnote 40 In particular, existing research does not find that Great Britain used its status as monetary hegemon to compel the United States to return to the gold standard in 1875, or much at all throughout Reconstruction.Footnote 41 One problem relates to the issue of variation: realist theories would have to show that hegemonic leadership changed throughout the period to match the varied voting structure on monetary policy in the United States discussed above. On the lack of hegemonic leadership by the British in the late 1860s and early 1870s in regard to the monetary standard, Gallarotti writes, “Time and time again Britain had an opportunity to bring about a regime which was in its interest, and time and time again it failed to do so… Had it exercised even the most minimal hegemony, something might have been consummated at any one of the conferences. But it didn’t. In fact, its actions more often served as an obstacle to cooperation.”Footnote 42

Both Bensel’s (1991) and Frieden’s (2014) theories fit within the broader APD and American Political Economy scholarship on how the United States’ fragmented political institutions have affected US state-building over time. In short, because of the US’s extreme institutional fragmentation, private, organized interests in the United States enjoy a privileged policymaking position.Footnote 43 The high number of veto points within the American political system, as well as the varied state-level regulatory landscape, allows for more opportunities for contestation. Highly organized and well-resourced interests are able to navigate this landscape much more effectively than individual citizens—a process referred to as “regulatory arbitrage.”Footnote 44 In more simple terms, private interests are able to outmaneuver the public in key policy areas because the high number of checks and balances within the American political system requires sustained attention and resources, which organized interests have and ordinary citizens do not.Footnote 45

As I detail in this article, both the economic development model as well as the open economy model have value for part of the Reconstruction experience, but they cannot explain the actual act that would return the United States to the gold standard. In particular, the two accounts have trouble explaining the switch of the Republican Party from state expansion in monetary policy to retrenchment throughout the period.Footnote 46 While the Republican Party remained a “developmental” party throughout the rest of the twentieth-century in other issue areas, scholars view the switch to return to the gold standard in 1875 as an act explicitly designed to minimize the central state’s power.Footnote 47 Bensel (1991) writes on the subject: “Resumption of the gold standard was an anti-statist development... the monetary regime imposed by specie payments placed control over the supply of currency beyond the reach of the central state.”Footnote 48

I argue that the theory of Elite Entanglement offers a way forward for existing scholarship because it integrates both state-centered and business power theories in explaining monetary policy outsourcing and financial instability. More broadly, existing scholarship does not attempt to incorporate the issue of financial instability in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries into its discussion of Reconstruction economic policy. I next provide an overview of how the historical institutional lens of the state is a useful one in studying monetary and fiscal policy and how I incorporate it into my theory.

4. A historical institutional approach

This paper’s approach is broadly informed by the field of historical institutionalism—a tradition that encourages studying the effects of existing institutions on the preferences of political actors.Footnote 49 Such institutions can be both physical (e.g. organizations and bureaucracies) or intangible (e.g. rules and procedures).Footnote 50 Historical institutionalists typically argue that policy preference formation is endogenous, in that existing institutions provide strong incentives for actors to behave a certain way and thus are themselves causal forces over time.Footnote 51 This approach is often counterposed with the “behaviorist” school within political science, in which scholars study political preferences and behavior (often below the elite level) to see how those preferences and behaviors affect the construction of political institutions.Footnote 52 Historical institutionalists instead suggest that institutions, by reorienting and incentivizing certain behaviors, may outlive those individuals (and their associated interests) that created them. This process is often referred to as path dependence or increasing returns.Footnote 53 In simple terms, while behaviorists emphasize how people’s preferences create policies, institutionalists emphasize the reverse: how policies create (or affect) preferences. As such, historical institutionalists emphasize the stickiness or inertia of institutions.Footnote 54

One key institution for historical institutionalists is the “state”—an organization that claims sovereignty over territory and people and encompasses legal, administrative, and coercive capacities.Footnote 55 Historical institutionalists view the state as an actor in its own right in the political sphere.Footnote 56 In that sense, the state is something distinct from parties, governing coalitions, or the government. Krasner (1984) provides a helpful metaphor, suggesting that the behaviorist and pluralist approaches in political science see the state as a sort of cash register, which neutrally adds up different interests in civil society without imputing its own preferences or biases.Footnote 57 Yet historical institutionalists insist that the state does have its own interests that bias the way private interests are represented in government.Footnote 58 Building on this view, this paper argues that the state’s semi-autonomous interest in cheap government borrowing has influenced the construction of fiscal and monetary institutions throughout US history.

Yet how does one operationalize the state in a nineteenth-century historical study? Furthermore, how can a researcher be confident that the state’s interest in cheap government borrowing is something analytically separate from pluralist interest representation in political parties? The difficulty here is compounded by the fact that state capacity was minimal in the Civil War and Reconstruction era.Footnote 59 As a state of “courts and parties,” state-building was much more a product of political party objectives than in later eras in which state agencies “forged” their own autonomy.Footnote 60 Bensel (1991) finds a similar overlap between the state and political parties. Because of the Republican Party’s dominance in the era, Bensel (1991) concludes, “From 1861 to 1877, the American state and the Republican party were essentially the same thing.”Footnote 61 In short, this paper agrees with this assessment for the Civil War. Because maintaining war spending was essential to state survival during the war, this paper argues that Republican Party interests in enabling fiscal flexibility were a proxy for state interests.Footnote 62

To gain leverage on disentangling state, partisan, and interest group influence, I conduct both historical qualitative research as well as quantitative testing of key roll-call votes in monetary policy. First, through qualitative historical research, I process-trace the origins of key fiscal and monetary policy proposals. In this process tracing research, if policy proposals originate primarily from state elites and receive opposition or relative ambivalence from powerful interests within the party’s coalition, I argue that one can reasonably conclude that the policy originated from the state’s interests as opposed to civil society or partisan-attached interest groups. There is, of course, an element of subjectivity with this type of analysis, which is unavoidable. However, to more robustly test the role of private interests in fiscal and monetary policy, I also conduct a series of logistic regression analyses of roll-call votes based on political and economic data. In those tests, if Republican Party partisanship is a powerful predictor of voting in the Civil War, whereas economic statistics representing key private interests are not, combined with qualitative research that suggests that state elites were the original source of that proposal, that would suggest that the state’s interests influenced the policy process.

After the Civil War, the near-complete overlap between state and party interests began to erode as the acute fiscal crisis passed. Cheap borrowing to allow for state spending was no longer tantamount to the survival of the Union. Furthermore, there emerged both interparty factional disputes over monetary policy, and partisan competition with resurgent Democrats. At this point, party-line voting no longer signified state interests but instead signified partisan competition. Yet the institutions that were created during the Civil War to serve the state—such as the national bank system—remained. While the national bank system was originally created to serve the state’s need for cheap financing, it increasingly provided benefits to the Republican Party’s core constituency.Footnote 63 In that sense, the state’s interests had become embedded in the partisan-institutional framework of Reconstruction, and as I detail, provided the Republican Party key leverage in the compromise of 1875, which returned the United States to the gold standard.

5. Data and methods: historical case study with roll-call vote analyses

A historical case study was the most appropriate research design for this project for a few reasons. Scholars have acknowledged that America’s public–private hybrid monetary regime remains understudied and undertheorized, especially within political science.Footnote 64 While others have studied the effects of institutions like the Federal Reserve on political outcomes, there has been little extant political science work on the historical construction of US monetary policy regimes.Footnote 65 Case studies, in their iterative approach to exploratory research, are adept at theory building as well as the identification of causal mechanisms that this subfield requires.Footnote 66 Case study research is typically performed through what is formally called process tracing. Process tracing involves identifying key actors, institutions, ideas, or other variables in the time period of interest and tracing their behavior and interaction over time to explain key outcomes. It involves taking “snapshots” of the proposed variables over time to see how they affect each other and assess the relative weights of each. In other words, process tracing requires gaining deep contextual knowledge of the attitudes, constraints, and goals of policymakers in their own time periods.

In addition to qualitative historical research, I also collected a variety of economic data and conducted a series of Logistic regression analyses to test existing explanations and the theory of Elite Entanglement. While process tracing and historical-qualitative research can help researchers conceptualize eras and cases more accurately, as well as provide limited theory testing through identification of causal processes, quantitative analyses of roll-call votes can augment such methods. Existing scholarship identifies the role of partisan, manufacturing, financial, and agricultural interests as influential in determining Congressional voting on monetary policy.Footnote 67 For the Civil War section, I operationalized manufacturing and agricultural interests through data collected from the 1860 Census: the number of manufacturing establishments in a district or state per 100 people and total farms in a district or state per 100 people. To measure financial interests, I used a dataset on aggregate statistics of state banks in 1860.Footnote 68 I also include a variable measuring the district and state percentage of the population Black to account for the possibility that state expansion in monetary policy was interpreted as a threat to the existing racial hierarchy, as is often shown throughout US history.Footnote 69 Lastly, I include party variables. Because existing scholarship identifies the Republican Party as synonymous with the state during the Civil War and much of Reconstruction, I operationalize state interests with a Republican dummy variable. These data were collected at the county level and aggregated to Congressional districts to allow testing of votes in the House of Representatives.Footnote 70 See Table 3 below for an overview of my variables during the Civil War. The exact list of districts included in these regressions can be found in the Appendix.

Table 3. Variables During the Civil War Era

During the Civil War, I expect that the state, operationalized through the Republican Party, will be supportive of measures that enable cheap spending, either through issuing currency or through cheap borrowing. Therefore, in votes related to enabling the creation of pure public money or a public–private monetary system, I expect that Republican members will be more likely to vote in favor. Second, I expect that districts with more state banks per 1,000 people will be less likely to vote for these measures, as they prefer to maintain their infrastructural role in intermediating state debt.

The variables are similar in Reconstruction with a few changes. Because of the creation of the national banking system in 1863, financial interests now encompassed both state banks and national banks. Therefore, I collected statistics on national banks in 1870 (number of banks in a district per 1,000 people).Footnote 71 Second, to understand how divides within manufacturing interests might have been affected by international exchange rate consequences of different monetary regimes, I also collected Census statistics on the number of manufacturers employed in cotton, wool, iron and steel industries per capita.Footnote 72 Lastly, because the acute crisis of the Civil War had passed and partisan competition eventually returned, in Reconstruction, I consider Republican Party partisanship to represent partisan as opposed to state interests. See Table 4 below for an overview of my variables in Reconstruction.

Table 4. Variables During Reconstruction Era

The economic development model of monetary policy suggests that voting on the Resumption Act would be based on regional cleavages, with the highly industrialized and capital-rich Northeast favoring a return to the gold standard and the agricultural and capital-poor Midwest and South opposing a return to gold. The open economy model suggests small differences within regions based on various industries’ positioning within the global economy. I show how these expectations do hold for votes on monetary policy leading up to late 1874, but the models cannot explain the actual return to the gold standard in the Resumption Act of 1875. In terms of the significance of these hypotheses for my theory, if private actors were the ones driving retrenchment, we would see manufacturing and financial interests as the main variables affecting voting on the Resumption Act of 1875. However, if partisan actors were the ones driving voting on the return to the gold standard and the expansion of the national banking system, we would see partisan attachment as the main variable affecting voting on the Resumption Act.

6. Antebellum finance

What we take for granted in our modern era, is not necessarily monetary stability, but monetary simplicity. Instead of dealing with one currency that fluctuates mildly over time, Americans in the mid-nineteenth-century had to learn about and transact with many different types of currencies of which they had limited knowledge. This period, beginning in 1837 after the abolishment of the Second Bank of the United States and lasting until 1863, is often referred to as the era of “Free Banking.”Footnote 73 “Free Banking” did not mean that there was no government oversight or regulation, but instead that one did not necessarily need explicit government approval (charter) to open a bank. Regulations varied from state to state, but in many states, anyone who had sufficient capital could open a bank and issue their own notes after depositing some capital with the state banking authority.Footnote 74 Private banknotes, for example, had to be redeemable in the official monetary standard of the time, typically gold or silver. However, these notes were not guaranteed in any fashion—such as the way most deposits in commercial bank accounts have been since the 1930s. If the bank collapsed, so did the value of the notes. Banks that played hard and fast with the rules, perhaps operating with fewer backing assets than required, were sometimes referred to as “Wildcat” banks.Footnote 75 Often operating in remote locations, where the “wildcats roamed,” the banks’ physical inaccessibility made it less likely people would come to redeem notes, thus affording them greater leeway in capital requirements.Footnote 76

Thus in the antebellum period, Americans could be presented with a variety of private banknotes in everyday transactions. In the estimation of John Sherman, Republican Senator and later Secretary of the Treasury, there were 1,642 banks established by the different regulations of 28 states. In Sherman’s opinion, this diversity in regulation made it “impossible to have uniform national currency.”Footnote 77 While local newspapers would attempt to provide information about the health and capitalization of banks, and which notes were trading at a discount, there was only so much that could be done to keep people fully informed. With so many different types of banknotes, counterfeiting was prevalent, and notes diminished in value the further they got from the bank of origin.Footnote 78 It was difficult for someone to know the quality of a banknote they received as payment that was issued in another state, which frequently led to negotiations on the value of the note.Footnote 79 In short, this chaotic banking landscape led to a highly inefficient form of exchange. Some states had greater success than others in regulating their banks, such as New York. Other states, such as Michigan, had a higher prevalence of so-called “Wildcat” banks, leading to persistent banking failures throughout the period.Footnote 80

Yet while this system of state banks was inefficient and produced banking panics such as in 1837 and 1857, there was a low likelihood of an overhaul of the existing financial architecture. Despite the system’s problems, with the failure of the Second Bank of the United States during Andrew Jackson’s presidency, as well as the broader Jacksonian bank war, there was little political will for systemic change. Democrats were suspicious of any increase of federal power, whether that was due to slavery or in banking policy. Over time, certain banks collapsed, perhaps because they lacked sufficient capital or were caught in a run, but outside of a few larger panics, the system of free banking worked as advertised. Individuals were free to judge which banks were reliable, and which were not. Thus, entering the Civil War, the financial system, while flawed, had a low likelihood of dramatic overhaul outside of extreme circumstances.

7. State expansion: the creation of the federal greenback

At the outbreak of war in April 1861, the Union’s fiscal position was poor. The Treasury was facing a $65 million deficit with declining customs revenue, as the South refused to allow the Union to collect duties from Southern ports.Footnote 81 Unable to wait for Congress to pass new taxes and tariffs, Treasury Secretary Salmon P. Chase first looked to Northeastern banks to fill the government’s coffers.Footnote 82 The loan negotiations in the summer of 1861 went poorly, exacerbating existing tension between Secretary Chase and the Northeastern banking elite.Footnote 83 Chase’s proposed borrowing terms (which were partially determined by Congress) were significantly below the market rate of interest, which frustrated the bankers.Footnote 84 Yet Chase, feeling that the government should not be beholden to private interests during wartime, reportedly told the bankers:

I hope you will find that you can take the loans required on terms which can be admitted. If not I must go back to Washington and issue notes for circulation….[even] [i]f we have to put out paper until it takes a thousand dollars to buy a breakfast.Footnote 85

Chase’s threat to the bankers to issue currency partially reflected his personal stubbornness, but it was also reflective of the change in the balance of power that the war had brought on.Footnote 86 Because of the war, the government had a more compelling reason to resort to extraordinary means of finance. Though $50 million was eventually loaned to the government, with two more optional loans of the same amount possible, both sides were frustrated with the negotiations.Footnote 87 This tension with state bankers further connected Secretary Chase to financier Jay Cooke, whose brother Henry, a newspaper editor in Ohio, had supported Chase’s political career.Footnote 88 In September 1861, Chase appointed Cooke to be a subscription agent of the Treasury Department, tasked with popularizing and selling government securities to the masses, not just to large Eastern banks.Footnote 89

The Union did not fare well early in the war, which encouraged the hoarding of gold instead of its recycling to banks. The result was that Eastern city banks lost gold reserves rapidly throughout the fall of 1861. Despite declining private gold reserves, even in December 1861, Chase still preferred financing war spending through borrowing instead of issuing currency. In his December report, Chase proposed a new national bank system in which a new system of national banks could issue a uniform national currency only with the purchase of federal bonds and their deposit with a federal agency.Footnote 90 The proposed system would create “captive demand” for federal debt, as national banks could use federal government debt as security for issuing their own national banknotes to be used by the public.Footnote 91 Returning to the typology of money mentioned above, Chase’s national bank plan was plainly a public–private monetary system—one in which private banknotes would be issued based on public collateral.

Despite Chase’s grand plans for financial system overhaul, by late December, banks were forced to end gold payments, which meant that they were not able to exchange depositor funds for gold.Footnote 92 The situation in the Treasury also became dire. Revenue from the new taxes passed in the summer of 1861, including the nation’s first income tax, was not due yet, and the army struggled to supply its growing ranks: the Treasury, as Richardson (1997) notes, was “empty.”Footnote 93

Some Republican leaders in the House seemed favorable to Chase’s national bank plan, but the severity of the fiscal crisis forced them to change course and find something that would provide more immediate revenue: currency issuance. Ways and Means Committee member Elbridge Spaulding (R-NY) proposed the Legal Tender Act, which would issue $150 million of US notes. Spaulding argued that Chase’s national bank plan “could not be passed and made available quickly enough to meet the crisis then pressing upon the government for money to sustain the army and navy.”Footnote 94 The switch was made in part because the bank bill faced strong opposition from state banks, and that “hesitancy and delay… would have been fatal.”Footnote 95 Republican Congressional leaders lobbied Chase for his support of the Legal Tender Act in exchange for pushing the national bank plan later on.Footnote 96 In a letter from Secretary Chase to William Cullen Bryant of the New York Post on February 4, 1862, Secretary Chase noted that his support of fiat currency “is only however, on condition that… a uniform banking system be authorized… securing at once a uniform and convertible currency… and creating a demand for national securities which will sustain their market value and facilitate loans.”Footnote 97

Most supporters of the currency issuance plan in Congress, including John Sherman (R-OH), acknowledged that printing fiat money was a wartime necessity to fund the army—a last resort.Footnote 98 Bankers were broadly opposed to the issuance of fiat money, which they considered irresponsible and a harbinger of financial ruin.Footnote 99 A group of New York City bankers led by James Gallatin lobbied Chase and the Lincoln administration against issuing legal tender notes in January 1862.Footnote 100 Overall, though, bankers were more mixed in their opposition to greenbacks than to Chase’s national bank system, which they more uniformly opposed.Footnote 101

In the end, the Republicans that passed the legal tender bill—with the blessing of Secretary Chase and the Lincoln administration—were strange bedfellows. Hammond writes, “It is also remarkable how little common interest, economic or regional, the innovators had; for they included, especially in their leadership, both Easterners with important business interests—Alley, Hooper, Spaulding, Stevens—and Western extremists—Bingham and Kellogg—whose constituents were mostly agrarian.”Footnote 102 What brought these disparate factions together within the Republican Party was not the economic interests of their constituents but the exigencies of war and the state’s need for cheap financing. On February 25, 1862, the Legal Tender Act was passed, issuing $150 million United States notes (greenbacks). Democrats, for the most part, voted against the Legal Tender Act.

In Table 5 below, I present two logistic regression models of Congressional voting on the Legal Tender Act of 1862, which issued $150 million greenbacks. Because party was operationalized as a series of dummy variables (Republican or not, Democrat or not), and because my theory predicts that being a Republican increases the likelihood of voting in favor of the bill, Republican serves as the reference category in the logistic regression. In short, that means that parties listed in the regression analysis should be interpreted as the effect of that party membership compared to being a Republican. For example, in Table 5 below, which shows House and Senate voting on the Legal Tender Act, Democrats were significantly less likely to vote for the Legal Tender Act compared to Republicans. Similarly, Republicans were more likely to vote for the act compared to those in the Union party. There was some mixed significance for the effect of financial interests on Congressional voting. In the House, districts with more state banks were somewhat less likely to support the Legal Tender Act, though that was significant only at the p < 0.1 level. It was not significant in the Senate. The other economic variables, total farms per 100 people, the share of the district population Black, and total manufacturing establishments per 100 people did not significantly affect voting.

Table 5. House and Senate Voting on the Legal Tender Act of 1862

Note:

* p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

With the issuance of $150 million greenbacks to finance war spending in February of 1862, the Union took itself off the international gold standard and assumed more direct public control over the money supply. Greenbacks were an example of pure public money—they were direct liabilities of the federal government. While the Republican Party played an important role in the bundling of various financial measures into a coherent package, I have shown how the origins of the greenback policy came primarily from the state’s fiscal crisis that arose in late 1861 rather than through the demands of partisan associated groups.

8. Outsourcing: the creation of the national bank system

Despite the passage of a revised internal revenue law and a second legal tender issue of another $150 million greenbacks in July, the Union again began to run out of money in late 1862. In response, Secretary Chase again proposed his plan of a “national currency”—a system of national banks that would replace the state banking institutions. However, the state banking elite remained strongly opposed to Chase’s plan.Footnote 103 In July 1862, Chase enlisted Samuel Hooper (R-MA) in the House and Senator John Sherman (R-OH) in the Senate to push the plan in Congress.Footnote 104 Yet at this juncture, Sherman did not seem to be fully sold on Chase’s plan. While Sherman disapproved of the state banking system, arguing that private note issue by state-chartered institutions was inefficient and potentially unconstitutional, he did not believe that the solution was to replace them with nationally chartered institutions that could issue currency.Footnote 105 Instead, Sherman suggested that government fiat currency should serve as the replacement for state bank issuance during wartime. In November of 1862, Sherman wrote to his brother William Tecumseh, at that point a Brigadier General in the Union Army, writing:

My remedy for paper money is, by taxation, to destroy the banks and confine the issue to Government paper. Let this only issue, as it is found to be difficult to negotiate the bonds of the government. As a matter of course there will be a time come when this or any scheme of paper money will lead to bankruptcy, but that is the result of war and not of any particular plan of finance.Footnote 106

Thus, even in late 1862, Sherman was more in favor of federal greenbacks than a national bank currency as a replacement for state banknotes. While Chase’s plan did not progress far through Congress in the summer of 1862, in December, the administration renewed its push for the bill.Footnote 107 President Lincoln supported it in his own message to Congress on December 1, 1862, and Chase turned to lobby Jay Cooke for his support. Originally, Cooke had disapproved of the national bank plan because “he was unwilling ‘to make war upon the state banking system’ and offend the bankers who were helping him sell federal bonds.”Footnote 108 However, by December, Chase had convinced Cooke to help him push the plan in Congress. It was a calculated risk for Jay Cooke—while he risked upsetting the very individuals he helped sell bonds to, the passage of the national bank bill would ensure even greater borrowing, thus ensuring more responsibility for Cooke in getting subscriptions.

Even with Jay Cooke’s conversion to supporting the bill, prospects in Congress still looked slim. On January 5, 1863, Sherman introduced a tax on state banking circulation but did not sponsor the corresponding national bank plan. On the House side, Samuel Hooper (R-MA) introduced the authorization for a national banking system based on the purchase of government bonds on January 7.Footnote 109 However, based on Sherman’s speeches in the Senate, he still remained unconvinced about Chase’s broader plan of replacing state bank issue with national bank issue, saying, “The purpose of this bill is to induce the banks of the United States to withdraw their bank paper in order to substitute for it a national currency, or rather the national currency we have already adopted.”Footnote 110 As in November of 1862, Sherman was focused on replacing state bank issues with more federal greenbacks, being the only national currency in existence thus far.

At this point, administration pressure on members of Congress to pass the national bank bill increased. President Lincoln wrote a letter to both houses of Congress on January 19, urging the passage of the bill.Footnote 111 Secretary Chase turned to the Cookes to lobby the bill through Congress. The Cookes focused their advocacy on Senator Sherman, which turned out to be successful.Footnote 112 In a letter to his wife at around this time, Sherman wrote:

Chase appealed to me through Cooke to remodel the bill to satisfy my views and take charge of it in the Senate. The appeal was of such a character that I could not resist, although I foresaw the difficulties and danger of defeat. When I made the speech on taxation of state bank bills, I had not determined what to do, but carefully avoided any reference to the National Bank bill. That speech brought me into correspondence with bankers and others, and while giving me some reputation, compelled me to study the preference between government and bank currency and led me to the conviction that it was a public duty to risk a defeat on the Bank Bill.Footnote 113

Even with Sherman’s conversion, the bill’s success was not guaranteed. State banks were broadly opposed to the bill.Footnote 114 In late January and early February of 1863, Sherman and the Cookes went on a pressure campaign in public newspapers to gain a broader base of support for the bill.Footnote 115 The bill eventually passed in February of 1863 in a narrow vote in the House and Senate.Footnote 116 Many scholars attribute its passage to the pressure campaign in the media by the Cookes and Sherman.Footnote 117 Sherman himself, in a letter to his brother on March 20 of 1863, remarked that he can “claim the paternity of the Bank Law.”Footnote 118

Table 6 below shows the logistic regression analyses of Congressional voting on the National Bank bill. As expected, Republicans were more likely to vote for the bill than Democrats and Union party members in the House, and Republicans were more likely to vote for the bill than Democrats in the Senate. Districts with more state banks per 1,000 people were less likely to vote for the bill in the House, though there was no significant effect in the Senate, perhaps due to the low N.

Table 6. House and Senate Voting on the National Bank Act of 1863

Note:

* p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

These findings provide additional support for the notion that the National Bank Act was a product primarily of state interests in maintaining cheap borrowing against the wishes of entrenched financial elites (state bankers). While Henry and Jay Cooke, financial elites who had close connections to government finance, played a key role in the bill’s passage, it is important not to overstate their influence. Secretary Chase had to first convince them to back the bill before they helped him successfully lobby John Sherman.

The newly created national bank system created “captive demand” for federal debt, as national banks could use federal government debt as security for issuing their own national banknotes to be used by the public.Footnote 119 While there were limits placed on the total number of notes allowed to be issued by national banks, the new system was deeply connected to government finance: by 1875, 63 percent of the portfolios of New York City national banks would be invested in US bonds.Footnote 120 The notes of national banks effectively replaced the federal greenback as both a monetary instrument and a source of financing for the federal government. The federal government had outsourced monetary creation, changing the monetary instrument from pure public money to public–private money.

The hybrid, public–private nature of the National Bank system was common knowledge for policymakers at the time. For some, like Senator John Sherman, this public–private partnership was an advantage of the system, arguing that “[t]here must be a combination between the interests of private individuals and the government” for a functional monetary system.Footnote 121 Yet others disliked this connection between the state and private interests, suggesting that state credit was being used to enrich financial elites. Congressman James Beck (D-KY) later referred to the system as “an odious monopoly, an unjust and iniquitous waste of public money and public credit to enrich the pets and partisans of the Administration.”Footnote 122 Congressman David Mellish (R-NY) similarly commented that “[t]he issue of national currency through the banks constitutes a subsidy at the expense of the Federal Treasury and for the benefit of the banks in its practical operation.”Footnote 123 This political conflict over who had the authority to create money would only become more acute during Reconstruction.

9. Fiscal retrenchment: reconstruction, the pursuit of gold, and the panic of 1873

In this section, I detail how the end of the Civil War changed the primary cleavage on which monetary policy was fought. With the end of the fiscal crisis, monetary policy was no longer driven by acute state imperatives but instead became driven by nonpartisan, regional coalitions based on material economic conditions. Second, I detail how the outsourcing of monetary authority to the national banking system during the Civil War encouraged fiscal retrenchment in the early phase of Reconstruction. The connection between outsourcing and fiscal retrenchment was simple: because the national bank system tied banknote issuance to the value of government debt, any drop in its value could threaten the foundation upon which notes were issued. Thus, maintaining the stability of the government debt market became a high priority. This was accomplished through fiscal retrenchment—cutting federal spending to ensure a government surplus to pay down the debt.

Fiscal retrenchment had important consequences on the Reconstruction political and economic system: (1) as noninterest-based federal spending decreased, government support for major infrastructure projects, like railroads, dried up. Politically, this conflict pitted the capital and credit-rich Northeast against the capital and credit-poor Midwest and South, and encouraged the development of a class-based fracture within Reconstruction politics, and (2) the declining availability of federal bonds pushed investors, such as Jay and Henry Cooke, to private speculation in railroad bonds. In 1873, the new national bank of Jay and Henry Cooke, which had invested heavily in the failing Northern Pacific Railway, went bankrupt, bringing down with it the broader economy.Footnote 124

After the war, the nation’s new currency rested on the value of government bonds. This meant that any significant decline in the value of government debt would be problematic for the monetary system. On the importance of the bond market to the financial system in Reconstruction, Bensel writes, “[T]he only operating requirement was that the budget of the U.S. government exhibit a fairly substantial and consistent surplus. Such a surplus allowed the Treasury to retire bonds in a gradually improving market because the debt itself was continually decreasing in size.”Footnote 125 National bank investors sought not just stability in the bond market, but appreciation of their investments, and that appreciation would only come through fiscal responsibility.

Appreciation of the value of government debt through federal government surplus went hand in hand with the broader goal of returning to the gold standard. In order to return to gold, the country had to be able to “redeem” (exchange) its currency in gold at the internationally agreed-upon ratio, which would require shrinking the money supply. Because of the issuance of fiat currency during the war, the money supply had swelled to make redeeming gold at the pre–Civil War rate of $20.67 per gold ounce impossible. Between 1864 and 1865, it took between 2 and 3 greenbacks to purchase one gold dollar.Footnote 126 Maintaining a federal government surplus in the postwar period would enable the Secretary of the Treasury to diminish the money supply by retiring currency as it came in.

There were also important international considerations for returning to gold. For an industrializing nation, the pull to be on a gold standard was strong; its pegged exchange rates allowed predictability in international trade, which would increase investment from abroad.Footnote 127 It was “sound” money according to most international elites. This was because a credible commitment to the gold standard provided a signal to other countries (wealthy foreign investors in particular) that debt purchases and investments would not be subject to wild fluctuations through the state.Footnote 128 Markets that adhered to the gold standard had lower rates of interest on loans from the “core” wealthy Western European countries, like Great Britain.Footnote 129 Flandreau (1996), for example, shows how network effects compelled many European countries in the early 1870s to go from a bimetallic gold and silver standard to demonetizing silver and therefore being on a monometallic gold standard.

However, the politics of these European countries’ decisions were quite different from those of the United States, as the United States was on a fiat money standard instead of a bimetallic standard. International network effects likely help explain the demonetization of silver in 1873 in the United States, as silver’s demonetization in Europe would have led to a massive influx of cheap silver, but it has a harder time explaining the politics of going from a fiat money standard back to a metallic standard. Furthermore, silver demonetization in the United States in 1873 was uncontroversial in comparison to the conflict over greenbacks and gold.Footnote 130 The lack of controversy over silver demonetization may sound strange to those who are familiar with the late twentieth-century populist movement, but it was only after the fight over greenbacks had been lost in 1875 that soft money representatives realized they had lost an opportunity to inflate the currency with silver.Footnote 131 At that point, the uncontroversial demonetization of 1873 became, retrospectively, the “Crime of '73.”Footnote 132

The return to gold and retrenchment more broadly were hotly contested topics. Pegging one’s currency to a commodity limited domestic monetary policy autonomy. In this era, it meant allowing Britain (the monetary hegemon) to “play a role in determining American economic conditions.”Footnote 133 As Frieden (2014) explains, the United States in 1865 sat at the midpoint between the “core” and the “periphery” in international development. While the United States was ideologically sympathetic to the industrialized nations of Western Europe (most of whom were on a gold standard), it had a production profile (of predominantly agrarian exports) more akin to less developed countries like Latin America, Russia, and Japan—many of whom stayed off the gold standard for much longer.Footnote 134

Japan is an instructive case. Like Europe, Japan had a bimetallic gold and silver standard in the early 1870s but chose not to demonetize silver. Because of the cheap influx of silver from abroad, gold coin disappeared, and Japan, from that point on, remained on a de facto silver standard. In 1872, in an attempt to modernize their banking system and support cheap government borrowing, the Meiji regime installed a system of national banks upon the recommendation of its Vice-Minister of Finance, Ito Hirobumi, who had been studying financial systems in the United States.Footnote 135 Japan’s system, similar to the US, allowed national banks to issue a unified national currency based on the purchase of government debt. Japan did not return to a gold standard until 1897.Footnote 136

Complicating matters further was the fact that most elites recognized the tremendous potential of the American economy coming out of the war. The United States was at the precipice of another industrial revolution, with nascent but growing industries in oil, steel, and railroads, with Wall Street as their financier.Footnote 137 The Robber Barons of the Gilded Age were just beginning to build their empires in the 1860s and 1870s: J.P. Morgan started J.P. Morgan and Co in New York City in 1861, a 31 year old John D. Rockefeller started the Standard Oil Company in Cleveland in 1870, and Andrew Mellon started at his father’s bank in Pittsburgh in 1873.Footnote 138 The shift from a political economy of republicanism—one in which production is organized around small entrepreneurs—to the political economy of corporate capitalism was just beginning in earnest.

Policymakers in Reconstruction recognized the precarity of the situation—a fast-growing economy combined with the need to shrink the money supply to support the bond market and return to gold. Senator John Sherman wrote to his brother William Tecumseh on this subject near the end of the war on November 10, 1865:”

The truth is, the close of the war with our resources unimpaired gives an elevation, a scope to the ideas of leading capitalists, far higher than anything ever undertaken in this country before. They talk of millions as confidently as formerly of thousands. No doubt the contraction that must soon come will explode merely visionary schemes, but many vast undertakings will be executed.Footnote 139

“Contraction”—meaning the shrinking of the money supply to resume the gold standard—became the keyword in Congress in this phase of Reconstruction. The United States had two main options to enact “contraction”: (1) shrink the money supply to enable quick resumption and (2) keep the money supply stable while the economy grew around it. While John Sherman preferred the latter, most members of Congress preferred the former.

Within “contraction,” there were two options for shrinking the money supply: (1) run a federal government surplus and allow the Treasury to redeem or destroy some of the collected notes, and/or (2) allow the Treasury secretary to sell bonds in exchange for greenbacks. By 1866, the first part of this plan was already underway—the end of the war meant that there was significant federal government retrenchment through a reduction in military spending. A recalcitrant South, opposed to giving Black Americans their civil rights, delayed this process, yet a substantial reduction in government spending occurred in 1866. From 1865 to 1866, the expenses of the federal government were cut down by more than half (from nearly $1.3 billion in 1865 to just over $500 million in 1866). With taxes (tariffs especially) still close to their war highs, the federal government surplus was over $37 million that year, and rose to $133 million in the following year.Footnote 140 This rapid reduction of the national debt was applauded by the Treasury in its 1866 report, “The idea that a national debt can be anything else than a burden… a mortgage upon the property and industry of the people—is fortunately not an American idea.”Footnote 141 To accomplish the second part of the plan, Congress passed the Contraction Act of 1866, which empowered Secretary of the Treasury Hugh McCulloch to contract the money supply by selling bonds and retiring greenbacks by $10 million in the first six months and not more than $4 million a month after that.

In the end, Sherman’s concerns about “contraction” were validated. Outcry from the public and from business leaders over depressed economic conditions led the policy to be abandoned just a year later in 1867. The anti-contraction sentiment was particularly strong among citizens’ groups. Of the 172 petitions related to contraction from a citizens group, in which a position about contraction could be ascertained, 171 of them were in favor of repealing or ending the policy of contraction.Footnote 142

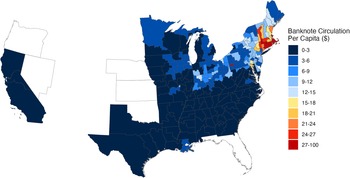

The fault line in monetary policy votes, unlike southern Reconstruction and civil rights, was not partisan but geographical.Footnote 143 The highly developed, capital-intensive Northeast had easy access to credit and an excess of currency, while the comparatively underdeveloped Midwest and South had neither. There was a large overlap between banknote circulation and manufacturing per capita (correlation = .85)—both were concentrated in the Northeast, with deficits in the Midwest and the South. Figure 2 below shows the average banknote circulation per capita in 1870, and Figure 3 shows the number of individuals employed in manufacturing per capita.Footnote 144 Bensel (1991) shows that for much of Reconstruction, monetary policy votes were decided on these geographical lines, determined by different levels of economic development. Highly developed areas supported the return to the gold standard more than lower developed areas, which at this stage in US history, was mostly a function of geographic region.

Figure 2. Banknote Circulation Per Capita 1870.

Figure 3. Individuals Employed in Manufacturing Per Capita 1870.

At this point, it may be useful to return to a larger question on the relationship between industrialization (and those who supported it) and the monetary standard. Why did capital and credit-rich areas support the gold standard in the first place? Why did capital and credit-poor areas support a flexible greenback standard? While structural and material at heart, these questions involved broader normative visions of what the economy should be.Footnote 145 The first vision, represented by capital and credit-poor areas, was of a republican economy—one in which production was organized around small entrepreneurs and landowners. The other was a vision of a corporate capitalist economy—one in which production was organized around fewer, larger firms or corporations in each economic sector.

These two competing visions of the economy demanded very different monetary systems. The republican economy—advocated for by the later “anti-monopolist” movement—required that money primarily function as a means of exchange.Footnote 146 This vision of the economy would be based on a decentralized network of small entrepreneurs, who, according to James Livingston, were more interested in “maintaining their standing as freeholders than in enlarging their claims on income and property.”Footnote 147 Thus, demand for money in this vision of the economy was essentially equivalent to demand for goods and services and therefore, did not place much emphasis on money’s role as a “store of value” as we now commonly understand it. A flexible monetary standard based on the needs of trade and exchange—greenbacks—would suffice.

The vision of a corporate capitalist economy—one in which production was organized around a few large firms in each economic sector—demanded a monetary system in which assets could be stored and saved with stable values to promote investment. Because corporate capitalism required a higher level of savings for investment, demand for money did not necessarily mean immediate demand for goods. Money’s function in this economy was both as a means of exchange but also as a stable store of value.Footnote 148 The proponents of this vision of the economy strongly preferred the gold standard, as it ensured a more stable monetary system over time. These debates soon became intertwined with class-based conflict, as the emerging upper class also strongly preferred a gold standard.Footnote 149

But how did these interests manifest politically? In short, varying levels of economic development did not match up well with political party boundaries at the time. The party system instead was based around opposition to (or support for) slavery. For example, the Republican Party at the start of Reconstruction, which controlled most of the North, was split between Eastern and Western factions on the money question.Footnote 150 Figure 4 shows the banknote circulation per capita by party in 1870. As can be seen in Figure 4, both parties were spread across the different regions. This structural difference made it difficult for parties to agree internally on a financial policy. Instead, cross-party, regional coalitions began to form. For example, northeastern Republicans and Democrats were generally in favor of a quick return to the gold standard, and supported contracting the currency, while midwestern Republicans and Democrats were more hesitant (most of the South had not rejoined the Union as of 1866).

Figure 4. Banknote Circulation Per Capita by Party 1870.

History gives us the benefit of hindsight. We know now that the corporate capitalist vision of the economy, based around a gold standard, won out.Footnote 151 Yet this victory did not seem certain to capitalists at the time. On capitalists’ insecurity in nineteenth-century American politics, Livingston writes:

[M]ost capitalists of the late nineteenth century did not see their eventual triumph as inevitable. Until the last few years of the century, indeed, they felt almost powerless to create a future in which their services and function would be recognized as legitimate. From their standpoint in the late 1800s, ‘ruinous competition,’ overproduction, and price deflation had created a secular trend toward a stationary state, in which profit incentives and their civilizing corollaries would disappear.Footnote 152