Introduction

The idea of partnership working having multiple levels was first coined by Sherry Arnstein in the 1960s when she constructed the ladder of citizen participation (Arnstein, Reference Arnstein1969). Arnstein’s ladder consisted of eight rungs, representing increasing levels of citizen agency, control, and power (Arnstein, Reference Arnstein1969). The eight rungs are divided into three broad categories of participatory power moving from: nonparticipation, tokenism to citizen control. The bottom two rungs consist of manipulation and therapy which are categorised as forms of nonparticipation where one group has no say on what concerns them (Norton, Reference Norton2021). In the middle lies three rungs: informing, consultation, and placation which are categorised under tokenistic practices. Although the individual is involved in decisions that concern them, they are not seen as equal (Norton, Reference Norton2021). The top three rungs: partnership, delegation, and citizen control are all categorised under citizen control. These three rungs represent the highest level of involvement/participation (Norton, Reference Norton2022). In addition, the top rung: citizen control, represents a state of involvement where a person takes over control of their own life and thus places the usual decision maker in a position of no power or control. In mental health terms, it signifies a state where service users completely overtake the system that they are actors in (Norton, Reference Norton2022). Of particular interest to this study is the alteration of the top two rungs of Arnstein’s ladder to that of co-design and co-production (The New Economics Foundation, 2013).

Within the participation literature, co-production is an umbrella term (McLean et al. Reference McLean, Carden, Aiken, Armstrong, Bray, Cassidy, Daub, Di Ruggiero, Fierro, Gagnon, Hutchinson, Kislov, Kothari, Kreindler, McCutcheon, Reszel, Scarrow and Graham2023). There are a number of reasons for this, including the inability of scholars to come up with a universal definition for the term, the concepts’ short but complex history as well as the many facets/mechanisms of action that are associated with it (Nabatchi et al. Reference Nabatchi, Sicilia and Sancino2017). For the purposes of this paper, we will utilise Norton’s (Reference Norton2022) definition as a basis to situate this work. Here, co-production involves:

the creation and continuous development of a dialogical space where all stakeholders, including service users, family members, carers, supporters and service providers enter a collaborative partnership with the aim of not only improving their own care but also that of service provision.

(Norton, Reference Norton2022, 27).

Ostrom, an American economist, originally coined the term co-production (Alford, Reference Alford2014). The term was first used within the public sector to support Ostrom in explaining why when police walked the streets of Boston that crime reduced dramatically compared to when police patrolled the streets using motor vehicles. Since then, in the five decades since its first conceptualisation, interest in the term has waxed and waned (Robert et al. Reference Robert, Donetto, Masterson and Kjellstrom2024). This is evident as co-production crossed interdisciplinary lines to that of law (Cahn, Reference Cahn2000) management (Loeffler & Bovaird, Reference Loeffler and Bovaird2021) user involvement (Beresford, Reference Beresford2021) and finally to where we see it today being used in mental health services as a key element of personal recovery (Health Service Executive, 2018, 2024; Norton, Reference Norton2022).

Like that of co-production, the personal recovery movement has also endured a short but turbulent history. Taking influence from the civil rights movement in the 1960/70’s, personal recovery was poorly defined until William A. Anthony defined it in 1993. Here, Anthony states that recovery is:

a deeply personal, unique process of changing one’s attitudes, values, feelings, goals, skills and/or roles. It is a way of living a satisfying, hopeful, and contributing life even with the limitations caused by illness. Recovery involves the development of new meaning and purpose in one’s life as one grows beyond the catastrophic effects of mental illness.

(Anthony, Reference Anthony1993, 21)

However, within an Irish context, personal recovery as a movement was not taken seriously until sometime after “A Vision for Change” was published (Department of Health, 2006). Despite being the first Irish policy to reference personal recovery, it took until 2014 for Irish services to develop a pilot initiative for recovery known as “Advancing Recovery in Ireland,” (ARI) (Health Service Executive, 2016). ARI attempted to implement personal recovery through the implementation of the top ten challenges for recovery oriented services devised by Julie Repper and colleagues. An initiative which was later named ImROC [Implementing Recovery through Organisational Change] (ImROC, n.d.). However, before this, in 2011, the College of Psychiatrists of Ireland commenced a pilot user involvement initiative known as REFOCUS.

The Recovery Experience Forum of Carers and Users of Services (REFOCUS) committee is an independent, not-for-profit group that forms an integral element of the College of Psychiatrists in Ireland. It is a committee composed of those with lived and familial experiences of mental health service use along with both trainee and consultant psychiatrists who come together “… to inform and guide psychiatrists towards the highest standards in training, ongoing competence and day-to-day practice” (College of Psychiatrist of Ireland, 2024). This diversity is spread across equally within the forum with eight members assigned to each role: service user representative, carer representative, and psychiatry representative. The committee’s work is two-fold – (1) contributing to and enhancing the training of future psychiatrists whilst (2) identifying mechanisms to improve mental health services through co-production. REFOCUS convenes once a quarter and this allows members the opportunity to debate on issues, contribute tangibly to research activities, co-produce, and publish college papers and present at college conferences. In so doing, recognising the power and influence of lived experience in college affairs. Although service users are involved in various committees within psychiatric bodies internationally – see for example service user/carer involvement of accreditation in the Royal College of Psychiatrists – no set forum is available. In addition, to the best of the authors’ knowledge, no qualitative research has been produced to review service user/carer involvement in such forums. Now that REFOCUS is in its fifteenth year (2025), it continues to evolve and strengthen its remit of embedding lived expertise in all college activities. However, within an Irish context, we are still unaware as to how involvement in partnership working and co-production with psychiatrists and the local psychiatrist accredited body impacts on all stakeholders involved in REFOCUS.

Aim of study

Given this gap in knowledge, the aim of this present study is to explore committee members’ perceptions of REFOCUS, their involvement, the impact this membership has had on their recovery orientation whilst also identifying opportunities for the future growth and development. For this paper, the methodology used will be autoethnography, which is useful in gathering the unique perspectives of the authors who are also members of REFOCUS in relation to several key factors that impact the committee’s role as a change agent within the College of Psychiatrists of Ireland.

Methods

Autoethnography is a qualitative research method that allows authors to report on social phenomena in a very personalised manner, drawing on their experiences as evidence within qualitative inquiry (Wall, Reference Wall2006). It was first introduced by the work of Heider in the 1970s and has grown in popularity since (Chang, Reference Chang2016). It is reported as a reliable and evidence-based research method as it takes from the fields of ethnography and autobiography to allow researchers’ reflexivity and subjectivity to be uncovered and utilised during the research process (Norton et al. Reference Norton, Griffin, Collins, Clark and Browne2023; Ramalho-de-Oliveira, Reference Ramalho-de-Oliveita2020). Due to the enhanced insider focus of the methodology, autoethnography as an evidence base is highly biased towards the world view of the researcher (Norton et al. Reference Norton, Griffin, Collins, Clark and Browne2023). However, it is praised for obtaining knowledge that is otherwise difficult to extract (Moberg, Reference Moberg2022). This is possible as in effect, personal narratives from researchers are intertwined with elements from our culture and wider society in order to create new knowledge (Chang. Reference Chang2016; Ellis et al. Reference Ellis, Adams and Bochner2011). In this way, it differs from reflective practice due to such philosophical intertwining that occurs only in autoethnography. As such, autoethnography usually sits within the realm of social constructionism as an epistemological position and an interpretivist ontology. However, there are several ethical and methodological challenges with this approach, with a lack of a singular method of applying autoethnography being significantly problematic (Norton et al. Reference Norton, Griffin, Collins, Clark and Browne2023). Despite this, for the purposes of this paper, we will utilise Adams et al’s. (Reference Adams, Jones and Ellie2015) approach which applies autoethnography through a six staged process including:

-

1. Foreground personal experiences in research and writing,

-

2. Illustration of sense-making processes,

-

3. Reflexivity,

-

4. Illustration of insider knowledge of cultural phenomena/experiences,

-

5. Description and critique of cultural norms, experiences, and practices,

-

6. Reciprocal responses for audiences.

(Adams et al. Reference Adams, Jones and Ellie2015).

These stages/phases are now discussed followed by the ethical considerations for this method.

Foreground personal experiences in research and writing

The first phase focuses on the personal experiences of the phenomenon under investigation (Adams et al. Reference Adams, Jones and Ellie2015). In this case being involved in and experiences of REFOCUS. During which, the researcher describes aspects of REFOCUS that they wish to explore further (Adams et al. Reference Adams, Jones and Ellie2015). For this study, this occurs through background questioning regarding both their understanding of what REFOCUS does and also descriptively documenting what occurs in a typical meeting of REFOCUS. As a result of this exercise one’s personal feelings and beliefs around the phenomenon is realised (Norton et al. Reference Norton, Griffin, Collins, Clark and Browne2023).

Illustration of sense-making processes

The second stage explores the experiences discussed in stage one in order to make sense of these experiences (Adams et al. Reference Adams, Jones and Ellie2015; Norton et al. Reference Norton, Griffin, Collins, Clark and Browne2023). Here, begins the process of intertwining these said experiences with that of culture and policy within the wider organisation that REFOCUS is part of: The College of Psychiatrists in Ireland, so that a gap in knowledge is identified (Adams et al. Reference Adams, Jones and Ellie2015). Like stage one, this happens in practice through further questioning of the experiences mentioned with help from an interview topic guide (Appendix A) (Norton et al. Reference Norton, Griffin, Collins, Clark and Browne2023).

Reflexivity

The third stage: reflexivity is important as it involves further sense making of the everyday practices of both REFOCUS and the College of Psychiatrists in Ireland to establish if REFOCUS actually makes a difference to everyday college business. This involves examining where REFOCUS and those involved in same sit on the hierarchy of power, which is carried out to allow for scrutiny between the organisational culture of the college and REFOCUS members (Adams et al. Reference Adams, Jones and Ellie2015). This occurs in practice through reflective questioning as to service user/carer/psychiatrist involvement and the influence of REFOCUS as a body within the everyday business of the College of Psychiatrist of Ireland.

Illustration of insider knowledge of cultural phenomena/experiences

Within this stage, an examination of the participants role within REFOCUS occurs in order to explore how participants can become agents of change within the wider system. As such, the stage allows individual participants to document what they feel needs to be achieved for change in procedure and practice to become a reality. Questioning here involves asking participants what they need to do to make this a reality based on their insider/outsider position to the organisation. During which, it is important to note the non-verbal silent cues as these are all evidence that can be used to further enhance interpretation (Adams et al. Reference Adams, Jones and Ellie2015).

Description and critique of cultural norms, experiences, and practices

This stage is similar to the Illustration of Sense-Making Processes stage as it critiques the culture of the organisation, but this time through the lens of the new norms created as part of the process (Adams et al. Reference Adams, Jones and Ellie2015). In practice, this is documented by asking participants if this change was to occur, how would the system and its actors react and as a result if this further warrants a cultural shift (Norton et al. Reference Norton, Griffin, Collins, Clark and Browne2023). Participants are also encouraged to identify what aspect of culture needs to change for the work of REFOCUS to not be tokenistic (Adams et al. Reference Adams, Jones and Ellie2015).

Reciprocal responses for audience

The last stage is achieved through participant engagement and critical discussion with others during the process (Adams et al. Reference Adams, Jones and Ellie2015). Despite making no real impact on the interview topic guide itself (Appendix A), it is marked as a stage as active participation and relationship building are key to the processes success (Norton et al. Reference Norton, Griffin, Collins, Clark and Browne2023).

The situation of the authors in the autoethnographical process

In order to achieve our aim, expertise from the group was sought. Such experts included (MJN, MR, MMcL, CB, CO’C, GB, and HK). Each of which has varying degrees of expertise when it comes to REFOCUS and recovery within the College of Psychiatrists of Ireland. MMcL is a consultant psychiatrist and co-chair of the college’s REFOCUS committee, CO’C is a trainee psychiatrist in the greater Dublin area. HK works for the College of Psychiatrists of Ireland and is secretary of the college’s REFOCUS committee. The remaining experts (MJN, MR, CB, and GB) are all members of REFOCUS and utilise their various lived experiences of service use, supporting loved one’s in their service use and recovery in order to enhance the work of the College of Psychiatrists of Ireland as both a professional body and influencer regarding the ongoing education of trainee and consultant psychiatrists in the Republic of Ireland.

In order to carry out the study, MJN created an interview topic guide based on the above autoethnographical steps (Norton et al. Reference Norton, Griffin, Collins, Clark and Browne2023) (See Appendix below). After which, the formation of a focus group which included all the above named authors of this paper and an interview was organised and conducted over the platform Zoom. This was a requirement as the participants were all geographically situated in different parts of the country (Republic of Ireland) and as such, it was deemed unfeasible for these participants to travel for the purposes of a focus group interview.

Ethical concerns with autoethnography

Autoethnography is considered “ethically messy,” springing into action ethical dilemmas as they relate to the use of the self in the research process (Dahal & Luitel, Reference Dahal and Luitel2022; Sparkes, Reference Sparkes2024). Like other research methodologies, ethical consideration should be given to issues pertaining to informed consent, confidentiality, risk of harm to self or others along with issues regarding data storage, protection and destruction. However, other ethical concerns can arise when using the self in research. Such challenges include the risk of triggering repressed thinking styles and memories (Chatham-Carpenter, Reference Chatham-Carpenter2010). This may result in the resurgence of symptoms of mental ill health that may go unchecked due to the researcher’s dual role as both researcher and participant. Additionally, violation of internal confidentiality to the self can occur in autoethnography (Tolich, Reference Tolich2010). This is ethically concerning as autoethnography can cause individuals to overshare leading to potential vulnerability and further distress. However, given these concerns, the authors sought ethical approval from the Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland research ethics committee which was granted on August 08th 2024 (REC No: 202407002).

Data analysis

Once these experiences were gathered and corroborated with the video file, a process of reflexive thematic analysis occurred (Braun & Clarke, Reference Braun and Clarke2006, Reference Bruan and Clarke2019, Reference Braun and Clarke2022, Reference Braun and Clarke2024, Reference Braun and Clarke2024a). This reflective process involved six phases including familiarisation with the data set, coding the data, generating initial themes, reviewing and developing themes, refining, defining and naming themes, and finally producing the report (Norton, Reference Norton2024). In practice this involved two of the authors (MJN, CB) taking the transcript and reading it several times in order to gather the main themes that can then be used for discussion within the text. For reliability and validity purposes, MJN and CB then met once themes were created to ensure that they identified similar themes to one another. Any disagreements were first debated and if a consensus was still not met, the transcript was then shared with another author (MMcL) who made the final decision regarding themes. During this process, MJN, CB, and MMcL all noted their own biases and preconceived ideas on the subject matter and through a process of memo writing, ensured that their analysis was as free as possible from human bias.

Results

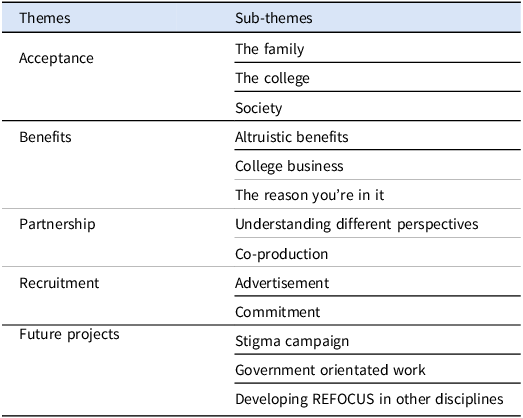

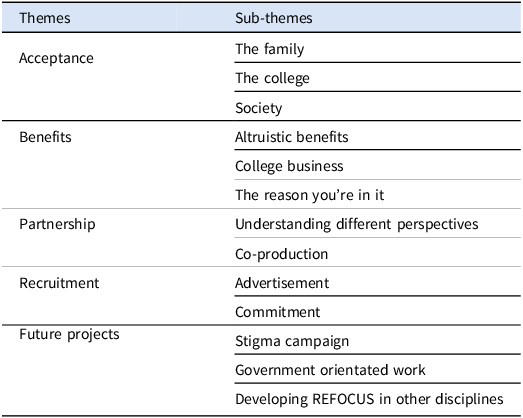

From a possible fourteen autoethnographic accounts, only seven authors (MJN, MR, MMcL, CB, CO’C, GB, HK) were available at time of focus group to give their accounts. This was as a result of work commitments and an inaccessibility of some to internet technology at day of focus group. From the seven autoethnographic accounts captured, five broad themes and several sub-themes were constructed (See Table 1) and are now presented.

Table 1. List of themes and sub-themes

Acceptance

In this study, participants discussed acceptance within a number of domains: “the family,” “the college” itself, and finally from wider “society,” which are now discussed.

The family

Mainly family member participants touched on this sub-theme of acceptance. Here they noted how that “in society (their loved one) is defined (in a certain way because they g)et into trouble and people just (see) his behaviour (as) really odd.” This leads to labelling the individual “mad, (which) really upsets (this individual)” as they begin to “think (about) the future” that their loved one will never have because of their illness. All of which can lead to the family member finding “it very difficult to accept (their) son’s illness.” This, as later discussed with a service user GB can lead to families keeping the illness in house and “hid(ing it) behind walls and bars.” In this analogy, the walls and bars are used to describe the metaphorical walls and bars erected by the family unit in order to protect the individual and themselves from further stigmatisation by society.

The college

Despite the non-acceptance of mental illness within the family, participants found solace in the college’s REFOCUS committee. For one participant they found REFOCUS as “positive forward thinking.” They also noted that the committee were a “very open group [full of] people (with) different opinions, (which led to) some very interesting discussions.” In particular, participants found that “the sharing of everyone’s story and everyone’s situation” to be particularly helpful as they can see how individuals, like psychiatrists were “doing their best for them, and … wanting (them)to improve.” However, this acceptance of the voice and experiences of service users and carers was not always evidence as “the college had barriers … that REFOCUS (had to) overcome.” Such barriers included “sit(ting) on campus,” “s(itting) with college members,” and “ask(ing) permission for writing papers.” Overcoming these barriers was noted by one participant as “one of the biggest achievements of REFOCUS.” Now, REFOCUS is accepted as part of college business so much that “the college president has attended meetings.”

Further work between the college and REFOCUS has further strengthened the relationship between both parties with “REFOCUS (being seen as) colleagues rather (than) something that was a barrier or some sort of obstacle, you know.” This realisation has caused “many psychiatrists (to) come on board with REFOCUS.” In this sense, now that REFOCUS is “10 years (old)” and because of the work of “just a few psychiatrists (like Anne])Jeffers,” as well as “Harry and Andrea for setting the scene.” REFOCUS has “earned its place at the college table.” In practice this involves REFOCUS’s co-chair “attend(ing) meetings with college as (a) committee member,” “visiting the Central Mental Hospital, (attending) the annual spring conference (and giving) a talk (to delegates).” For new, trainees coming on stream, this engagement with REFOCUS is seen as normal practice:

Yeah. And I suppose it’s interesting hearing from GB, because I suppose I’ve only been a trainee for a few years now, and it’s interesting to hear that I suppose it was a bit of a battle at the start, because my, I suppose my understanding of the colleges relationship with REFOCUS. But, like I said, I’ve only been a trainee for a few years. So has always been very much that REFOCUS was our very respected kind of group in the same way that any of the faculties, or any of the other sort of components of the college would be, you know, asked for their opinion, and look for around pieces to do with changing training, curriculum, all that sort of stuff.

For others, particularly from a lay perspective, service users and carers feel accepted into REFOCUS to such an extent that one participant stated that they “see them much more as my tribe now.” This is evident in the way service users and family members also utilise this space as a mechanism to safely off-load their worries and concerns in the presence of peers as well as the psychiatrists within the group:

Sometimes you feel very isolated and you can’t. You can’t keep talking about, you know, to your family or friend, you know, because sometimes it can become upsetting. And it’s like everything you just. You know, when you have a group there, that’s they really understand what’s happening with mental health. And you know, when they understand really about what happens in people’s lives when you have mental health problems that was really helpful, too. you know,

The society

GB, a gentleman who has used the services for “nearly 50 years now” has noted improvements in the services offered in that time scale. He goes on to suggest that at the beginning services “were poor, (but they have) develop(ed) in the last 10 or 20 years.” For GB, he now lives in hope that “the day will come where my schizophrenia will be acceptable.” However, it is well noted in participant responses that “This stigma of mental health is still there, no matter what people … say.” GB tells us of an example where stigma is rife, even in other parts of medicine:

I’ve seen the rejection on people’s faces when I’ve mentioned that I’ve schizophrenia. Very rarely do I mention it. especially in the workplace. You don’t do that otherwise. I mean, I’ve gone to my GP. And he said, you don’t want me to put down schizophrenia on the medical. I’ve been unwell at times. You don’t want me to put that down. Where would you get the GP. Don’t want you to put down what’s wrong with you? What you’re suffering for like, because he knows most of the workplace isn’t safe for that like.

This stigma experienced by GB with his GP does not only impact service users as the service providers in the room also noted “stigma on our health professions.” Particularly those in “certain specialties (that) come under a lot of particular fire,” such as psychiatry. For those in REFOCUS, a role shift occurs whereby service users and family members become the “advocat(es for these) professionals.” Such stigmatisation of the profession by society and other specialities in medicine can result in “some … clinicians … leav(ing)” their posts.”

Benefits

Participants in this study noted a number of ways in which being involved in REFOCUS could benefit not only themselves but the whole psychiatry movement. These benefits are categorised into three sub-themes: “altruistic benefits,” “college business,” and “the reason you’re in it.” These benefit categories are now discussed.

Altruistic benefits

Participants have noted a reciprocal process in being involved in REFOCUS, so much so that they suggest that “we probably get more back from being involved in the group than we give.” In addition, being involved in REFOCUS from a service users/family member perspective has “empowered (them) to do stuff that (they) wouldn’t normally do” like “standing up in front of a crowd” at a conference. Not only this, involvement in REFOCUS has allowed one to dream of reaching one’s full potential by “reaching into stuff that potential that you never would ever have used or been able to use like.” All of which allows the individual to look at REFOCUS as a source of respect and “optimism” that has arisen from the “pessimism” inflicted on an individual by their illness. GB describes how his involvement in REFOCUS has allowed him to face the inpatient psychiatric environment again, but from a place of safety and learning rather than fear of the unknown:

…you know, learning about the Central Mental Hospital and all the services it has to offer has really been an enlightenment. It’s calmed me down where I don’t like. When I was in the hospital, like it was a bad time like where I was put in a panic cell. And you know the experience was bad. But going to the Central Mental Hospital, which had, you know, which is probably even has people of fears of like that. It just washed away all those… bad memories like.

Another positive aspect of REFOCUS has been the ability “to share things with people” through the processes of peer support. This was noted by another individual who mentioned how REFOCUS acted as a catalyst that allowed them to share “stuff from the psychiatrist” in an “open forum consultation.” Such sharing resulted in “a lot of empathy and support (that) happen(ed) at the same time (as) a lot of crack (and jokes) in the group.” HK noted how “impressively open” REFOCUS members were with their lived experience. He recalls an example where MJN shared his story for a video on “the diagnosis project” and how this was both “so insightful” to hear as well as reflective of how “people just feel safe enough to be that open.” The power of peer support for one participant was that realisation that he/she/they will not have to “feel isolated” and suffer alone anymore:

The first few times I went to the meetings as well, and you know there’s all the supports put in place, but it does rise a lot of things to the surface. But it basically gives you somewhere to go with those feelings. You know, it’s not all about yourself. And one of my, you know what I mean it. There’s an agency there, there’s a support network. And you feel you know, the shame as well of being the self-centeredness as a service user. You know what I mean. You get so sick of yourself. You know the mental thing. It’s such an internal you know you must. You won’t rest from us, you know. Why would you want to go to a meeting where you’re gonna spend more time talking about it. But this is the structure and the what happens in those meetings? It’s quite transformative, and it gives you some. And you know, as an adult service user. It gives you some place to put some of those emotions.

College business

Participants in this study identified how REFOCUS “has influenced training and conferences, particularly … for our trainee doctors.” In terms of influencing training, one participant noted how REFOCUS “ma(de) sure that the (service user/carer) viewpoint (is) the lens that we’re looking through.” This according to GB is also about ensuring the mistakes of the past are not repeated:

I thought the focus for me was an enlightenment of change. Like, you know, we’re like, I’ve been in the system as a service user since 1975. And there was slow change like it was just mechanical meetings with the psychiatrists every 6 months, and your medication the same questions asked like there was no engagement. Where in your personal life, what was going on in your life, and all like. And the REFOCUS has kind of. I’ve attended meetings with young psychiatrists, trainees, psychiatrists, and they’ve listened and asked questions, and all where the whole hierarchical position as a psychiatrist has come down to the level of the service user …

For family members, such involvement in education is carried out in order to “pass on stuff as a family member and explain how you feel as well because of what you’re seeing, what your family member is going through.” However, they also identified how “the role that REFOCUS has also … in what goes on with the college, …with legislation, and all the … pieces that go on (around) the country (regarding) mental health.” All of which is useful for service users and family members in particular to “better understanding …what’s going on behind the scenes” whilst “meeting different people from different backgrounds.” Seeing what happens behind the scenes allows service users “to see the bigger picture. It’s not just about you know me as a service user.” This bigger picture is not one sided. In fact service users get to see how psychiatrists are trained and the administration involved in that which all benefited the service user by “makes me much more aware of things.” All of which allows conversations with stakeholders to happen “on a human level.” However, there is an acknowledgement for CO’C, a trainee psychiatrist, that “the challeng(ing) element is trying to do that every day and trying to actually bring it in every day.” Regardless of this, REFOCUS has been noted as a mechanism that is “trying to do something about it and be supportive to people and change the way people look at mental health.” More recent examples of this, as noted by participants includes “this … piece of research,” “the diagnosis projects videos,” “visit(ing) the National Forensic Mental Health Service in Portland” and debating “the new Mental Health Act.”

The reason you’re in it

REFOCUS, particularly for the psychiatrists within the group, is a reminder as to why they do what they do. CO’C states how one can “get caught up in all the work day to day, like as a trainee, and your exams and all that kind of stuff, and you kind of forget the reason why you’re in it.” When such individuals engage with REFOCUS, it “helps (them) to just recognise that (humanity) again… to see (it) more clearly, (and recognise) that we’re all the same.” For service users, being involved in REFOCUS allows them to someway “better the services … for someone else.” Particularly for the next generation of service users to engage with services:

The fact that you can kind of bring back them years to someone else, and all that information that you’ve gathered up about your illness and about. And you have a way of sharing it like true to focus. You know you can. You can benefit other people like young people, especially like, you know that it’s just a reward. I get the reward. But I also know that I’m giving something back like, you know, which is just so. So it’s not all about myself anymore,

Partnership

In this study, partnership working was identified as an important theme to participants. In the context of this paper, the theme partnership is further subdivided into two sub-themes: “understanding different perspectives” and “co-production,” which are now presented.

Understanding different perspectives

The agenda for meetings within REFOCUS is not made up by the College of Psychiatrist of Ireland alone. Instead one participant noted how REFOCUS is “an open forum” that is not rigid in terms of agenda structure. Instead, this same participant describes how “everyone gets their opportunity to sort of suggesting. Say, I think it’d be great if we worked on this, or I think we need more education around this piece.” However, despite this sense of equal engagement and flexibility, there is a focus to “refocus the conversation around” service users and family members. This in turn creates “a safe space for us all to be able to share what the focus means (to) our own personal focus.” CO’C also adds to this suggesting that even psychiatrists have a lived experience through their personal and professional life to bring to the table at REFOCUS meetings also:

you know I do think we all have lived experience, you know. I’m very lucky. I haven’t had major mental illness, but I have huge lived experience of family members and friends, and through my work I meet all these people. You know. So, although I haven’t been in the position of being ill myself, you know we all bring our own lived experience to it. I think that’s probably to me the key part about the group.

Co-production

Co-production in this instance begins with the name REFOCUS as “it’s kind of like focusing on the service user and family members and carers and the psychiatrists.” The idea behind REFOCUS is simple. It is about “everyone sitting around and … build(ing) up relationship(s).” Although everyone brings “very different experiences” to REFOCUS, the commonality is that “we want to make things better.” This shared focus has allowed for “discussions (to be) open and respectful” and stakeholders to see all sides of the conversation:

the psychiatrist side their opinions and their barriers that they have to overcome. And then I can see that also the cares like, you know. So you’re seeing a whole fully rounded view of the of the people involved.

For CB, a new service user representative on REFOCUS, she “notic(ed a) really interesting blend of the three cohorts, how they inform each other, and ultimately how (this) inform(s) psychiatry and improve practices.”

Recruitment

The theme recruitment refers to the ability and mechanisms by which REFOCUS is advertised and promoted within a mental health context. It is divided into two sub-themes which include: “advertisement” and “commitment.” Each are now discussed.

Advertisement

For participants, the mechanisms whereby they first encountered REFOCUS were through either “nominat(ion) by an association” or via the internet. However, until this first encounter participants “didn’t know … what it was going to be about.” In addition, for CO’C, a student first of medicine and then of psychiatry, she noted how as trainees, she “hadn’t heard (of) REFOCUS prior to starting (her speciality) training (in psychiatry).” However, despite this, there is an acknowledgement that “the word (is) spread[ing] slowly but gradually out to the college.” Once recruited to the committee, CB noted the procedures and tone created by the college before the commencement of the first meeting:

It was very clear. The ground rules, and you know, and there’s a lot of information before you join the group. but it it’s very subtle. You know what I mean. I feel that the way the group was convened. But also, you know, there’s a lot of time taken into when you join that you know it. It’s made. Everything’s made very clear. And that’s it’s very respectful. You really get that? The tone from the very beginning, and that does make a difference, and it kind of sets the scene.

Commitment

Of particular note from participants is the level of commitment involved in joining and contributing tangibly to REFOCUS. For our co-chair MMcL, this commitment includes “sign(ing) up to … meetings regularly (and) responding to circulars that come through an email.” In addition, part of this commitment is “to practice the … message th(at) REFOCUS wants to give out.” This includes in social engagements held by the college like “… talk(ing) at … seminars.”

Future projects

The final theme was that of future projects. This theme examines the various future projects that REFOCUS can get involved with based on college values and group commitments. The theme future projects has several sub-themes including: “stigma campaign,” “government orientated work” and “developing REFOCUS in other disciplines.”

Stigma campaign

HK highlighted the need for “a campaign on stigma.” He continues by suggesting “a video campaign around misconceptions around mental illness” where REFOCUS members could speak about “the relationship with your psychiatrist, or … maybe spending time in a facility or … your experience where the public perception might be way off the reality.” HK adds to this suggesting if a series like “24 hours in A&E” could be done for psychiatry where “people see how … psychiatrists work” so that we could “educate the public on (how the) psychiatrists work” and change the narrative currently evident around mental health and psychiatry. An example of the current narrative includes:

hear(ing) stories of how the services and they blame the psychiatrists, how they, you know when there is a homicide and the system missed. They could have stopped the homicide three years before. They were told by the psychiatrists that there is a case in England now at the present that would have said. A news where they could have stopped the homicide three years before. If they’d listen to the psychiatrist, you know.

Such negativity surrounding the profession has led to a drop in individuals choosing the “specialty … as a career.”

Government orientated work

Other work that REFOCUS could be involved in is getting “government’s input into mental health, which (at present, is) very lacking.” Such work involves “influenc(ing) legislation,” “meet(ing government to advocate) for … funding,” and assigning a member “spec(ifaclly) designated to be at the meetings with Government” on behalf of the REFOCUS committee. Additionally, REFOCUS could work with governmental agencies to prevent psychiatrist who train here from leaving the country:

But the fact at all. It’s like everything in Ireland at the moment, like teachers and hospital workers, nurses and doctors, that they’re all being trained here, but yet they’re all leaving the country, and we have such a lack. Of you know, good people, that the good psychiatrists and good doctors and everything. And I suppose my thing is, I get really annoyed at the Government over this and what you know I mean, they don’t seem to appreciate what people actually do. you know, in their daily life, in their work.

Developing REFOCUS in other disciplines

As suggested by a participant, the REFOCUS initiative seems to work quite well and therefore should be expanded to other professional bodies. REFOCUS could be used as a model to develop more service user/family member inclusion in the professional training and work of professional bodies into the future:

I think, as a process that as a structure works quite well. It’d be interesting to see if it would be something that could be used elsewhere. You know, other colleges or other organized, … training organizations. Could you use it as a model?

Discussion

To the best of the authors’ knowledge, this paper represents the first empirical investigation of REFOCUS and its involvement with the College of Psychiatrists of Ireland. As a result, the paper serves as a benchmark for other professional bodies, inclusive of the college, in further building on the work carried out by REFOCUS members in the future so that more user involvement and co-production can occur at a national, professional body level.

However, despite the need for this study, it has raised a concern in regards to the consistent presence of stigma – both internalised and external – evident within the mental health system today. This is not a surprising finding considering how mental health has been and continues to be stigmatised today (Ahad et al. Reference Ahad, Sanchez-Gonzalez and Junquera2023; Corrigan & Watson Reference Corrigan and Watson2002; World Health Organisation, 2024). However, what is surprising is how in depth this concept is within individual REFOCUS members’ as well as within the discipline of medicine. In our study, GB highlighted both the internal and external stigma experienced by him throughout his half century utilising services. GB described how other disciplines, like general practice medicine, suggesting not to have the words schizophrenia mentioned on his reports due to the doctor’s fear of poor employment prospects for GB. Consequently, internalised stigma was also mentioned by GB when he discussed REFOCUS’s visit to the Central Mental Hospital and the fear he exhibited as a result due to historical narratives of psychiatry. Interestingly, psychiatry as a speciality was also the subject of stigmatising behaviour from within medicine itself. This is not a new development. Shi et al. (Reference Shi, Li and Fan2023), being one of a number of authors who have started a conversation on this very issue. Despite this, a trainee psychiatrist, CO’C highlighted that we all, no matter what class, no matter what position we take all have lived experience of some kind. She goes on to explain her position suggesting that everyone knows someone who has been impacted by mental health, whether it be personal lived experience, the experience of friends or familial lived experience and as such, stigma should not be still present within mental health discourse. Despite the words of CO’C, the results of this paper all suggest that stigma is still a major issue within mental health service provision today and is something that this study calls for future investigation into in order to focus on this further, particularly interdisciplinary stigma evident towards psychiatry. In addition, HK suggests that in addressing stigma at a college level, that the college should work with REFOCUS on a stigma reduction campaign and utilise the assets of REFOCUS to reduce the rate of internalised, externalised, and interdisciplinary stigma evident within current mental health discourse.

Despite the issues of stigma, no other negative aspects of collaborative working were noted by participants. The first benefit for those in REFOCUS was the informal peer support that takes place between members at quarterly meetings. Informal peer support describes a phenomenon where individuals from different backgrounds support and listen to each other based on the similarity of their lived experiences (Mental Health Commission of Canada, 2024). In the case of REFOCUS members, the informal peer support exhibited was reciprocal in nature and resulted in individuals feeling that they no longer have to go and suffer alone. This notion of mental health causing an individual to suffer alone is not only a result of stigma, but for many illnesses noted in psychiatry, this element forms part of the psychopathology of disease (Mushtaq et al. Reference Mushtaq, Shoib, Shah and Mushtaq2014). As such, the findings of this paper suggests that the informal peer support exhibited by members has an unknown therapeutic benefit to those engaged in peer support activity as it reduces the element of isolation from the psychopathology of mental disease in this cohort. This reduction in isolation is noted not just here but also in the wider peer support literature regardless of type examined (Bravata et al. Reference Bravata, Kim, Russell, Goldman and Pace2023).

A central theme in this paper is that of partnership working and to a lesser extent co-production. Through working with psychiatrists within REFOCUS, individual service users and family members begin to see the bigger picture. In other words, they get to see the organisational and professional restrictions imposed on them in day-to-day operations of the mental health services. They also get to see the human side of the profession of psychiatry – trying to practice a recovery, human rights based approach within a traditional hierarchical archaic system. This does not occur by accident, in fact through working together in partnership, the hierarchical boundaries naturally evident in the therapeutic relationship starts to break down. However, the authors’ of this present paper question whether these hierarchical barriers are indeed broken or whether through partnership working, that the level where service users and carers sit is actually raised to meet that of the psychiatrist. This requires further theoretical investigation to identify the mechanism of action that occurs here. Regardless, this approach seems to be positive as CB, a service user representative of REFOCUS now describing the psychiatrists on REFOCUS as part of her tribe.

Finally, the findings of this paper has highlighted how participation in REFOCUS for service users and carers have allowed them to reach some of their recovery goals as they relate to CHIME – particularly in terms of identity and meaning and purpose. CHIME is an acronym created by Leamy et al. (Reference Leamy, Bird, Le Boutillier, Williams and Slade2011) in order to describe the central tenets of personal recovery. In terms of the two aspects of CHIME achieved through REFOCUS: identity, meaning and purpose – both of these were most evident in both past and future activity. Such as discussing the reform of the Mental Health Act, involvement in discussions at a governmental level relating to mental health and through the already mentioned stigma campaign. Future study should examine in more theoretical depth how much more closely aligned participation in REFOCUS is to the acronym CHIME and indeed to that of the personal recovery movement.

Limitations of study

As mentioned previously, this study represents the first to the authors’ knowledge to focus on REFOCUS and its working relationship with the College of Psychiatrists of Ireland. Although this provides valuable knowledge as it pertains to the inner workings and benefits of REFOCUS for all stakeholders involved, the study cannot begeneralisable to other contexts due to the subjective, interpretivist mechanisms of the work. Given this lack of generalisability, this paper now calls for a quantitative investigation in order to establish how these findings compare to data gathered through validated scales.

In addition, the use of an autoethnographic approach also brings with it a limitation which by nature of use, is evident in this study. Autoethnography by its very nature is highly biased towards the worldview of the authors of this study (Poerwandari, Reference Poerwandari2021). However, this was necessary to allow us to investigate the worldview of REFOCUS members as it pertains to their experiences of co-production and partnership working. Again, this limits generalisability of the findings to other population. As such, future qualitative studies on REFOCUS should aim to use a methodology that is less biased towards the worldview of the authors as evident here.

Conclusion

This study presents the first attempt to explore the role and impact of REFOCUS on those who make up its membership. Through a process of autoethnography, a number of themes and sub-themes were constructed focusing on areas including stigma, informal peer support, user involvement, and recovery. In essence, despite the continuous presence of stigma within and external to the individual, REFOCUS provided participants with an identity and reason to live and use their lived experiences for the betterment of mental health services and the future training of psychiatrists. The study also found that REFOCUS has a positive impact on both college business, governmental legislation and indeed on the training of future psychiatrists. Despite this, there are several limitations relating to the methodology used as well as of the participants chosen to contribute their experiences to the paper. As such, future research should try and utilise less biased methods to confirm or reject conclusions raised from this present study.

Funding statement

The study received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial, or not-for-profit sector.

Competing interests

We declare that all the authors in this study are members of the College of Psychiatrists of Ireland REFOCUS Group.

Ethical standards

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committee on human experimentation with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008. The authors assert that ethical approval for publication of this research paper has been provided by RCSI University of Medicine and Health Science (REC No. 202407002).

Appendix A. Interview topic guide

Foreground personal experiences in research and writing

-

Describe the current activities of REFOCUS?

-

What happens in a typical meeting of REFOCUS? What are the key parts?

Illustration of sense-making processes

-

What was the initial reaction by the College of Psychiatrists of Ireland to service user/family member involvement in college activity? Has this reaction changed? If so, how?

-

Do you believe the College of Psychiatrists of Ireland respects and values the work of REFOCUS? If so, how?

-

Do you feel there is a gap in the involvement of REFOCUS in college business? If so, what is this gap?

Reflexivity

-

Do you feel that REFOCUS is a necessary component of college business? If so, how?

-

How does your involvement in REFOCUS impact on your identity as a service user/family member/psychiatrist?

-

How is your lived experience (lived, familial, professional) utilised in REFOCUS?

-

What are the benefits/challenges to REFOCUS for you personally and for the wider college setting?

-

If REFOCUS can change one thing in college business, what would that be? Why?

Illustration of insider knowledge of cultural phenomena/experiences

-

What do you think needs to be done to effect this change to college business?

-

How can your role as a service user/family member/psychiatry rep on the committee influence this change?

Description and critique of cultural norms, experiences and practices

-

If this change was to occur, how would the college react to this change in your opinion?

Reciprocal responses for audiences.

-

Is there anything else you would like to add?