Disclaimer: The views expressed in this publication are those of invited contributors and not necessarily those of the Institute and Faculty of Actuaries. The Institute and Faculty of Actuaries do not endorse any of the views stated, nor any claims or representations made in this publication and accept no responsibility or liability to any person for loss or damage suffered as a consequence of their placing reliance upon any view, claim or representation made in this publication. The information and expressions of opinion contained in this publication are not intended to be a comprehensive study, nor to provide actuarial advice or advice of any nature and should not be treated as a substitute for specific advice concerning individual situations. On no account may any part of this publication be reproduced without the written permission of the Institute and Faculty of Actuaries.

1. Introduction

1.1 Background

In December 2020 the Institute and Faculty of Actuaries (IFoA) published its Thematic Review Report titled Pensions: actuarial factors used to calculate benefits in UK pension schemes (Pensions-Thematic-Review (PDF) (actuaries.org.uk)) (the “Thematic Review”). A key recommendation from that report was further research into the way commutation rates are set, and the IFoA Commutation Rate Working Party was subsequently established in September 2021 to address the following:

-

The appropriate allowances to make for selection risk, market volatility, and other common criteria in use in the determination of commutation rates.

-

How frequent and when should commutation rates be reviewed.

-

How actuaries should present their review of commutation rates to trustees or other decision-makers.

The intended audience is members of the IFoA who are involved in setting and advising on commutation rates. There will undoubtedly be a wide range of views and reasonable outcomes for commutation rates depending on scheme circumstances. Throughout the discussions and drafting of this paper, our primary objective was not to create guidance for members of the profession. Rather, it was to stimulate debate by exploring the topic and current practices, in order to help actuaries formulate their advice to clients.

The basic premise followed throughout much of this paper is to consider the commutation rate from first principles to determine an appropriate starting point, and then consider reasons why, and the circumstances when it may be appropriate to depart from that starting point (or when it may not be appropriate to). This worked well in many instances, but less well for others where the impact on commutation rates is more nuanced or scheme specific.

As noted above, the working party is keen that their findings should not be too directive for members of the profession. However, we recognised that there are certain areas where we do wish to express a view. One such area was the typical level of commutation rates and the extent to which they represented fair value to the pension scheme member. At the risk of generalising, there is often a noticeable disconnect between the commutation rates offered and the best estimate value. In the broadest of terms, the working party’s view is that across the UK’s defined benefit landscape, commutation rates should be reviewed in the context of providing fair value for members. Where actuaries recommend or are asked to support setting rates at lower levels, the rationale for doing so, and impact on members, should be made very clear to the decision-makers.

There is, however, an inevitable tension between pension scheme members and the sponsors of the scheme. To the extent that commutation rates are improved for the benefit of scheme members, that is a corresponding cost that must ultimately be borne by sponsors of UK defined benefit pension schemes. This tension has arguably become more pronounced because of certain liability measures (e.g., technical provisions or statutory corporate accounting) including an allowance for members commuting some of their retirement pension on the prevailing commutation rate. To the extent that commutation rates are improved, it often has a direct bearing on the funding/accounting liability values, as well as the longer-term cost.

The working party does not expect the reader to agree with everything said in the paper, but does hope the paper helps actuaries in formulating the advice they give to their clients and in exercising their professional judgement.

1.2 Scope of the Paper

We held regular discussions and meetings over the period from September 2021 to March 2023 and findings have been based on the prevailing legislative regime in that period. The Thematic Review raised several areas for further deliberation, and indeed as part of our discussion we also identified several further questions that could be considered when looking at commutation rates. However, the focus of our review has been solely on the commutation of defined benefit pensions as provided by occupational private sector pension schemes in the UK.

Within our scope we have only considered commutation rates in the context of their use when converting defined benefit pensions into a pension commencement lump sum at a member’s retirement date. There are several other contexts in which commutation rates may be used (including, for example, conversion of full pension into a trivial or serious ill-health lump sum). We have not considered these in any detail as part of our discussions, and as such our views cannot be assumed to directly apply to these contexts.

There were other recommendations in the Thematic Review, such as collating industry-wide benchmarking. These were not in the scope of the working party review and are not covered in this paper. We appreciate that the topic of commutation rates has many facets, and indeed others within the actuarial profession may wish to consider wider elements of the application of commutation rates. We hope this paper serves to complement any future debates on this topic.

1.3 Executive Summary and Conclusions

In Section 3 we comment on the appropriate allowance to make for various criteria in setting commutation rates. To determine this, we first explored what an appropriate starting point should look like, before considering reasons why an actuary’s advice on commutation rates might differ from that starting point. Our conclusions were:

-

The starting point for a commutation rate should be to calculate it in line with the scheme’s cash equivalent transfer value (“CETV”) basis, both in terms of actuarial assumptions and the methodology. In their advice, actuaries should consider providing justification where the recommended commutation rates deviate from this starting point and quantify these differences from both the scheme’s perspective and the perspective of example members.

-

There are a number of good reasons to deviate from that starting point, although many common reasons used, such as selection, are often used without (in our view) adequate justification. We comment on a number of potential reasons to deviate from our suggested starting point in turn, including when in our view they are appropriate to use, and when they are not. These include allowance for selection risk, allowance for de-risking, funding position, covenant strength, intergenerational fairness, market/industry practice, and others.

In Sections 4 and 5 we discuss how frequently and when commutation rates should be reviewed:

-

In line with the Thematic Review paper we agree that 3 years should be the maximum time between reviews, and indeed where commutation rates are not market-related (i.e., updated at least quarterly) actuaries should consider performing a high-level review of commutation rates annually.

-

Market-related commutation rates should also be considered, especially in periods of volatile market conditions.

-

There are good arguments to review commutation terms either following or during a valuation and we comment on their relative advantages and disadvantages. Reviews should also be carried out when there has been a material change in circumstance.

In Section 6 we cover how actuaries should present their review of commutation rates to trustees or other decision-makers. Here our conclusions include:

-

An actuary’s advice on commutation rates should satisfy the Technical Actuarial Standards (TASs). The focus should be on clear and concise advice, with information required to take key decisions clearly set out.

-

Where actuarial certification of rates is required, certification should be clearly provided in writing.

-

Actuaries should illustrate the impact on members of changes in terms, including on the member’s pension commencement lump sum and residual scheme pension.

1.4 Acknowledgements

The working party would like to thank the following for their support and contributions:

-

Alison Pollock (Shadow for Pensions Research Sub-Committee)

-

David Gordon (author of Thematic Review Report titled Pensions: actuarial factors used to calculate benefits in UK pension schemes)

-

The Institute and Faculty of Actuaries’ Pensions Committee and Pensions Research Sub-Committee

2. The Appropriate Allowances to Make for Selection Risk, Market Volatility, and Other Common Criteria in Use in the Determination of Commutation Rates

2.1 Introduction

We first considered the approach to setting a commutation rate if starting from a blank sheet of paper (Section 2.2). We then considered reasons why an actuary might depart from our suggested starting point in the advice they provide trustees or sponsors on commutation rates or when setting it themselves (Section 3). We recognise that in practice each scheme will have a different practical starting point depending on the commutation rates currently in force.

2.2 Given a Blank Sheet of Paper, How Would You Set a Commutation Rate?

We believe that the starting point for a commutation rate should be to calculate it in line with fair value for the pension given up, which in most cases would be consistent with the scheme’s “CETV” basis, both in terms of actuarial assumptions and the methodology.

We discussed the transfer value requirements as being present to ensure members receive fair value for pension given up, and as such this also seemed the most sensible start point for commutation rates, despite no such explicit requirements for commutation to offer fair value in legislation. Although this difference in legislation is important, in our view it is reasonable to assume that members would typically expect to receive fair value for pension converted to cash, and we also view this expectation as a reasonable one. We note that such concepts of fair value are also present in legislation for other options such as early retirement pensions, and as such there does not seem to be a good reason to treat commutation differently.

Fair value also ensures members are not unduly or unwittingly losing value by taking this option, noting that very few members would be able to understand or challenge the terms on which commutation rates are set.

Consistency with other actuarial factors is important and, in particular, consistency between commutation and the CETV basis is sensible given both terms are used to convert defined benefit pension into a capital lump sum, potentially offering two concurrent and comparable options as a member approaches retirement. We note that CETV terms are market-related and typically update on a monthly basis, and commutation terms typically reviewed less frequently, in many cases only once every 3 years. We discuss the pros and cons of market-related commutation terms in Section 4.3, noting that there can be good reasons to review commutation rates less frequently than CETVs. We are aware that some schemes may have a CETV basis set above best estimate levels – this is covered further in Section 3.

Based on the above we could not see a good argument for anything other than broadly best estimate of the cost of the scheme providing the benefit. We did however consider other possibilities, including but not limited to:

-

Technical provisions cost of the benefit given up. As technical provisions are required to incorporate prudence, and are primarily used as a basis for sponsors to fund schemes, this did not seem relevant as a value for individual members.

-

An even stronger measure, such as the “buyout” cost of the benefits given up (i.e., the cost of securing those benefits with a third-party insurer), or the costs calculated on a “gilts flat” discounting basis. If commutation rates were set in this way, then when members exercised the commutation option it would cause a funding strain against the scheme and reduce the security of the remaining members’ benefits – this would not seem appropriate.

Further detail of our suggested start point is set out in Table 1.

Table 1. Suggested starting point

There are a number of considerations as to why actuaries’ advice on commutation rates might in practice be different to the suggested starting position as described above. These are covered in Section 3. Throughout the rest of this paper we use the term “starting point” when referring to our suggested starting point as described above.

3. Why Might Commutation Rates in Practice be Set at a Different Level from the Suggested Starting Point?

3.1 Introduction

We have explored a number of potential reasons why a departure from the starting point might be considered, under the following headings:

-

Member-related issues including communications

-

Scheme-related financial issues

-

Practical considerations

-

Comparison with other factors

-

Legal and tax considerations

As a general rule, in our view, approaches for calculating a commutation rate should be consistent between each review. In particular, it would not be appropriate to change the method of calculation with no justification other than simply that the new method produces a lower or higher commutation rate.

3.2 Member-Related Issues Including Communications

3.2.1 Selection risk

Selection risk is a common reason given for setting commutation rates below our suggested starting point. The argument is that members in poorer health who are expected not to live as long as those in normal health could select against the scheme as they take a larger pension commencement lump sum.

We would consider this to be an appropriate reason to deviate from the starting point if the actuary can quantify selection against the specific scheme, for example by having evidence that members in poorer health take larger pension commencement lump sums. Where there is evidence that selection is present, we believe it may be appropriate to adjust the mortality assumptions to allow for selection against the scheme. We could not see any rationale for adjusting any of the other assumptions for selection. Where a reduction is made for selection, actuaries should in all cases highlight to clients what is implicitly being assumed about a scheme’s membership in order to justify such a reduction.

For example, if making a 10% reduction to commutation rates for selection, we have calculated using typical assumptions that in a typical scheme where 80% of members commute, this is equivalent to effectively assuming that life expectancy in retirement is more than 10 years lower for those who commute compared to those who do not. This is equivalent to typical mortality scaling of 200% for members who do commute versus 45% for those who do not, when applied to a typical mortality base table. In most cases we would not expect this to be a reasonable assumption, and it certainly should not be used without sound justification.

We do not consider it appropriate to use selection risk as a justification to move away from the starting point if the majority of scheme members take the maximum (or near maximum) pension commencement lump sum when it is offered, regardless of their health status – it seems difficult to draw a conclusion that members are actively selecting against the scheme. Anecdotal evidence should not be used as a justification of selection.

We also note that there is limited evidence that members can accurately predict their own life expectancy. Therefore, even if members’ intention is to select against the scheme, this may not be borne out in practice. A paper commissioned by the Society of Actuaries suggested that there is a slight tendency to underestimate life expectancy by a median of 2.0 years 1 (Greenwald & Associates, 2020).

To justify a proposal to reduce commutation terms for selection risk, a scheme actuary would need to determine if there is a correlation between deaths at younger ages and members who commuted larger amounts. We considered available data sources and could not find any industry-wide data to use to analyse selection risk. Therefore, the working party determined that each individual scheme would need to consider this issue based on their scheme data. This may only be available for the largest schemes who hold sufficient historical data.

3.2.2 Member communication

In our view, an actuary could advise on simplifying the commutation rates to avoid extensive numbers of rates (e.g., unisex terms, same rates recommended for similar pension increase types). However, there is a limit here and, in our view, it is not appropriate to materially change the value of the option to members.

Concerns over communication and potential complaints should not be used as a justification to not reduce commutation rates (particularly if the starting point is lower than the current commutation rates). Other member option factors change and can reduce (e.g., transfer values). In our experience there is little evidence of member complaints when commutation rates similarly reduce.

It would be interesting to consider whether members are less likely to take the commutation option when they have multiple tranches of benefit, and/or the propensity for members to take the commutation option when rates have been “harder to communicate” – we were not aware of any data supporting this, but larger individual schemes may be able to explore this.

3.2.3 Member retirement planning

If commutation rates are market-related it could be appropriate to fix them for a period (e.g., CETV guarantee period of 3 months) to aid member retirement planning. However, we do not think it is appropriate to use simpler member retirement planning as a reason to not increase rates for several years despite changes in financial conditions and/or scheme circumstances. Data on member complaints for commutation rates changing between quotation and payment and whether members actually change their choice when the commutation rates change could be used to justify the deviation from the starting point.

3.2.4 Intergenerational fairness

We believe that, absent any change in circumstances, actuaries should use the same principles to advise on setting rates over time, so, for example, if historically rates have been set as best estimate it would be appropriate to keep the same principle. Trustees may want to avoid a cliff-edge in rates between different generations so it may be appropriate for an actuary to advise to adjust towards the starting point in stages rather than in one single move. We do not think this should be used as a justification for keeping commutation rates permanently lower than the starting point. In considering this issue, actuaries may want to consider the scheme’s historical commutation rates and the market conditions underlying those rates as well as any historical rules (and legal advice) if there have been any changes.

3.2.5 Pension commencement lump sum is an option

It is often noted that commutation is an option available to members (which they do not need to take). We do not believe it is appropriate to consider the optionality (or otherwise) of the commutation benefit when deciding on the appropriate rates to be used, given how commonly members opt for this benefit.

3.2.6 Existence of defined contribution (DC) benefits

Where there is an option to convert DC or additional voluntary contributions (AVC) benefits into a scheme DB pension it may be appropriate to have consistency between commutation rates and conversion terms. In all other situations we do not believe it is appropriate to consider existence of DC or AVC benefits when advising on or setting commutation rates. Depending on member choices this would affect the percentage of defined benefit pension commuted but should not affect the terms for converting defined benefit pension to cash.

3.3 Scheme-Related Financial Issues

3.3.1 Scheme funding level

If the scheme is particularly underfunded on the actuarial basis underlying the starting point, then it may be appropriate to reduce rates (similarly CETVs can be reduced for underfunding). In most cases we would think it appropriate that members should be informed that the commutation rate has been reduced for underfunding.

However, we note that members may have less choice around when to retire (usually close to normal retirement age) whereas there is more flexibility around when to take a transfer and therefore it may not be appropriate to adjust commutation rates downwards for underfunding. While this may be complicated by the emerging trend of CETVs being offered at retirement, unless CETVs are reduced it is hard to argue underfunding as a reason to reduce commutation rates. Before making any allowance for underfunding, actuaries should assess the funding level of the scheme on the same basis as the assumptions underlying the starting point for commutation rates.

3.3.2 Strength of sponsor covenant

The strength of the sponsor covenant should be considered along with the scheme’s funding level (see Section 3.2.1). If the covenant is weak and the scheme is underfunded, then commutation rates could be reduced below the starting point. However, similar arguments to those in Section 3.2.1 apply, noting members have less choice around when to retire.

3.3.3 Funding (or accounting) cost of increasing rates (too much too quickly)

If current rates are considerably below those that have been calculated as the starting point, then a large one-off increase (or reduction) may be deemed unfair in creating a sudden change in benefit value and may have a significant one-off impact on funding (or accounting) cost, which may be undesirable. It may therefore be deemed appropriate to “pre-plan” to increase/reduce rates in a number of steps. However, this is not appropriate to use as a justification not to recognise what a “fair” rate would be.

Given the increased focus on long-term targets and a “low dependency” position in the new funding regime, funding cost should be considered more widely than technical provisions. We note that improvements in commutation rates would not impact the long-term funding target where there is no allowance for commutation, including if the long-term funding target is buyout. In considering this issue, actuaries could consider the funding level of the scheme allowing for increased commutation rates and the additional contributions that would be required under any schedule of contribution agreement with the sponsor – combined with evidence of (un)affordability.

3.3.4 Allowance for de-risking

We considered in detail the issue of how and when to make allowance for changes in investment strategy in commutation rates (e.g., where a scheme has reduced risk and hence reduced expected return, and/or has plans to do so in future). We recognise that there are a range of views in this area, including among the members of the working party. We also note that the new DB Funding Code requires schemes to set a low dependency target and a de-risking plan to get there. We believe that the comments in this Section remain relevant in this context. We split our comments in this area into allowance for de-risking to date (i.e., past investment strategy changes) and allowance for future de-risking (i.e., planned future investment strategy changes).

Allowance for de-risking to date: in most cases it would be appropriate for advice to reflect the current investment strategy including any de-risking to date. This is analogous to CETV regulations that require trustees to provide at least the best estimate of the amount required to make provision in the scheme, having “regard to the scheme’s investment strategy” (though noting that no such legislative requirement exists for commutation rates).

There may be exceptions to this, for example where a specific agreement has been made between trustees and sponsors regarding commutation rates being calculated on a different assumed investment strategy (e.g., before de-risking took place). However, in these cases actuaries should be able to justify their advice to their client, noting that clients and indeed members may question why there is a difference in the assumed investment strategy between commutation rates and CETVs. However, actuaries should not disregard de-risking to date in calculation of commutation rates unless there is sound justification to do so.

Allowance for future de-risking: where future de-risking is theoretical, not formally documented, and/or is contingent on future events, then it is reasonable to not reflect it in commutation rates. However, in these cases such de-risking would often not be allowed for in CETVs either, and hence not in the starting point for commutation rates. Any departure from the CETV approach should be justified.

When considering either de-risking to date or future de-risking, it may be reasonable to assume a different construction of discount rate (e.g., using a single discount rate rather than pre- and post-retirement rates) for commutation rates compared with CETVs or calculation of technical provisions, where this is justified (e.g., due to the specific demographic subset of members taking each option being different to one another and/or different to the scheme as a whole).

Where future de-risking is formally documented and not contingent on future events or experience, it would be appropriate in most cases for it to also be reflected in commutation rates, unless there is sound justification to not do so. In all cases discount rate construction should not be different for commutation rates compared with CETVs without sound justification.

In considering whether to deviate from the starting point, actuaries could consider the scheme’s investment strategy including planned future changes and how and whether this has been documented, as well as any de-risking history or historical agreement between trustees and sponsors on de-risking.

3.3.5 Proximity to a buyout transaction

Where a scheme is close to full buy-in/buyout it might be appropriate to advise on aligning commutation rates to insurer terms. We note that this is particularly relevant where scheme terms are fixed for a period and where there has been a significant change in market conditions since the commutation rates were last updated, given that insurer terms are generally market related. The scheme’s transfer values may already allow for a movement towards an insurer’s transfer value basis so this may already be reflected in the starting point for commutation rates.

However, there may be some judgement on how close a scheme is to buy-in/buyout. If at the point the scheme is expected to meet the long-term objective of buyout and still has deferred members, it may be appropriate to align terms with insurer terms sooner. If there is no intention of buying out the scheme, or if it is not expected that there will be any deferred members at the point of buyout, then it would be difficult to use this as a justification for moving away from the starting point. Actuaries could consider insurer commutation rates if these are available.

3.3.6 Where the CETV basis is set to provide greater value than best estimate

If the scheme’s CETV basis is set to provide greater value than best estimate, actuaries could consider advising commutation rates to be on a best estimate basis, which would be below the value of CETVs offered. If this is the case, any differences between the commutation rates and the CETV basis should be highlighted to decision-makers, and potentially to members. The decision-maker may wish for the commutation rates to be consistent with the scheme’s CETVs in any case.

3.3.7 Climate risk

Considerations for climate risk should be appropriately allowed for in setting the commutation assumptions but there are no other implications specifically relating to climate risk.

3.4 Practical Considerations

3.4.1 Ease of administration

The form the commutation rate may take could be influenced by administration system constraints, for example whether the same commutation rate is used for all tranches of benefits or if using unisex rates which could lead to a difference with the starting point. Any administration constraints should not influence the derivation of the assumptions used in setting the commutation rates apart, from in the way described above. For example, where you have multiple pension increases it is reasonable to combine similar increases (e.g., CPI capped at 5% pa and RPI capped at 5% pa).

The order in which pension is commuted (e.g., uniformly across all tranches or tranche-by-tranche) should be considered – this is often based on past practice. If there is a tranche-by-tranche order, then this may need to be considered in any combining of commutation rates. In formulating advice, the actuary could consider instances of administration errors or additional costs if using different commutation rates for different tranches.

3.4.2 Cost of calculation/implementation

This should not affect the assumptions used but may impact how the commutation rates are derived in practice. The method used to derive the commutation rates may be simplified because of the cost of calculation, for example using single-equivalent rate assumptions instead of a full yield curve or vice versa.

A change in administrator may prompt a commutation rate review as different administrators will use different systems with different flexibilities and constraints. Any additional costs of calculation or implementation should be considered in the context of potential impacts on member benefits from using a simplified approach.

3.4.3 Averaging/smoothing market conditions over a period of time when setting factors

To avoid unusual market behaviour, or reduce volatility, it may be appropriate to average/smooth market conditions over a suitable period when setting rates, as opposed to reflecting those at a set point in time. It would not be appropriate to change the way in which market conditions are reflected each time rates are reviewed without justification.

In particular, once practice has been established, it would not be appropriate to change the methodology without justification (e.g., if the period over which the averaging of market conditions took place is changed, or if such averaging is introduced/removed, then the advice provided should explain why these changes have been made). Actuaries should consider whether previous commutation rates have been based on averaging of market conditions.

3.5 Comparison with Other Factors

3.5.1 Market/industry practice

Many decision-makers typically focus on how their scheme’s commutation rates compare to other schemes when considering updates to terms – known as benchmarking analysis. Benchmarking terms may be appropriate when comparing between two schemes in the same covenant group with similar benefits and investment strategies.

Some decision-makers are reassured to see that their commutation rates (actual or proposed) are in keeping with market practice, even if they acknowledge that the rates are below a best estimate level. In these situations, both the starting point and proposed commutation rates should be compared to the benchmarking, and any limitations of the benchmarking data should be made clear. Given differences in benefits, investment strategy, covenant, and date of review, among others, benchmarking data can often be misleading. Actuaries should deliver their advice on commutation rates according to the scheme’s own circumstances (benefits, investment strategy, covenant, etc.) and not by benchmarking.

We believe that benchmarking data is not appropriate in and of itself as a justification for actuaries to advise that rates should be set lower than starting point. However, decision-makers and stakeholders may take it into account. Widespread use of benchmarking carries risks such as herding behaviour and group-think. There is also a risk that decisions are made based on out-of-date data, as any industry-wide changes could take many years to be reflected in benchmarking data.

3.5.2 Comparison with open market annuity rates

It is hard to see justification to align scheme terms with open market annuity rates given likely differences in covenant/investment strategy of provider versus scheme.

3.5.3 Comparison with self-sufficiency (long-term target/low dependency) rates

Given low dependency is likely to be a relevant measure for a scheme (perhaps even a secondary funding target), it is useful for trustees or decision-makers to have comparator information on how actual terms compare with terms on this measure. However, again, it is hard to see a justification to align scheme terms with low dependency terms, given that basis is likely to incorporate a higher prudence margin, and given funding position and investment strategy may not yet be aligned with the low dependency position.

3.5.4 Comparison with the Pension Protection Fund (“PPF”)’s own commutation rates

We do not believe a comparison with PPF commutation rates is appropriate in general as:

-

PPF benefits are different to the scheme benefits being given up for cash

-

Where covenant is relatively strong and/or funding is materially over 100% on PPF basis, PPF rates do not seem a relevant comparator

-

Existence of the PPF should not in general influence scheme strategy and member option terms

3.6 Legal and Tax Considerations

3.6.1 Powers to set terms under the rules

The scheme rules will direct who has the power to set commutation rates – be it the trustees, sponsor, or actuary, or indeed some combination of these. Where the explicit power sits with the actuary and/or there is a requirement, for example, the actuary to certify the rate as reasonable, then that requirement needs to be reflected in the resulting rates. However, we would not expect this to be a reason to depart from a best estimate starting point.

In theory, the balance of powers in the trust deed and rules will make it clear who is responsible for setting commutation rates, noting that it could be any one of the sponsor, the trustees or the scheme actuary, or any combination of them. It is then up to that party (or parties) to determine the final level of commutation rates. Using the framework described in this paper, that would firstly involve the scheme actuary determining the starting point for the commutation rates. Based on the balance of powers in the rules, the decision-maker(s) can then decide the relative weight they wish to put on the various considerations raised in this paper. In practice we recognise that the decision-making is not always so clear cut, and that some permutations of the balance of powers can present more challenges than others.

Our view is that although the powers in the rules may impact the outcome of the commutation rates, they should not affect the starting point for the actuary’s advice to the trustee or sponsor. The powers in the rules may influence how wide the range of reasonable outcomes is. Where the actuary has no responsibility for setting or certifying the commutation rates, their advice should set out the proposed rates, but then the decision-maker may decide to depart from that. Where the actuary has an explicit responsibility for setting or certifying commutation rates, they must have regard to it. In some cases, it may be appropriate for the trustees and/or the actuary to take legal advice on the wording of the scheme rules.

3.6.2 Tax status of pension commencement lump sum (PCLS)

Typically, 25% of the value of pension benefits can be taken as a tax-free lump sum (the PCLS). However, this tax advantage is not relevant to setting commutation rates as tax status is individual for each member. In addition, the lump sum is usually described to members as tax-free, so in our view it is hard to justify subsequently depriving the member of the tax benefit through adjusted terms. It is a political decision as to whether to tax the pension commencement lump sum or not.

3.6.3 Considered as part of the benefit structure

If the sponsor has the unilateral power to set commutation rates, then the sponsor may consider them to be an extension of scheme benefits, and therefore may not agree that a CETV “fair value” approach is necessary. In these cases, we would still expect the actuary to highlight what a best estimate rate would be and to advise on what would (and would not) in their view be a reasonable departure from this.

Where the balance of power sits with the trustees and/or the actuary, or if there is an over-riding requirement for the actuary to certify the reasonableness of the commutation rates, viewing commutation as part of the benefit structure is not an appropriate justification to depart from the starting point.

3.6.4 Where commutation rates are hardcoded in the rules

In some situations the commutation rates are hardcoded in the rules. If the hardcoded commutation rates deviated significantly from the starting point the actuary should highlight this to their client. And in some circumstances the actuary may wish to raise with their client if they wish to consider a change in the scheme rules or discretionary increase/augmentation of the commutation rates set out in the rules.

4. How Frequent and When Should Commutation Rates be Reviewed?

4.1 Introduction

For the purposes of this paper we have interpreted a commutation rate review to be when the trustee or other decision-maker commissions actuarial advice to consider the principles and assumptions used to derive the scheme’s commutation rates. We would not consider a pre-agreed formulaic update of the commutation rates for market conditions to constitute a commutation rate review.

4.2 How Frequent Should Commutation Rates be Reviewed?

We strongly agree with the Thematic Review paper that 3 years should be seen as the maximum time between reviews, rather than the default 2 (Gordon, 2020), especially where commutation rates are not updated regularly (e.g., every 3 months) for changes in market conditions. Performing an annual high-level commutation rate review would be appropriate in most circumstances, subject to some of the points set out below. Such a review could take place alongside production of an Annual Actuarial Report where appropriate.

Frequency of review is likely to be dependent on whether the scheme’s commutation rates are market-related or fixed, and whether there have been changes in financial conditions or other scheme circumstances. At the previous commutation rate review, the trustees or decision-makers may have pre-agreed some events that would trigger a commutation rate review, for example de-risking the scheme’s investment strategy or other significant market movements.

There are also some practical aspects that should be considered, such as:

-

Competing projects reducing time available and possibly enthusiasm for annual high-level commutation rate reviews

-

Additional costs from carrying out additional reviews

-

Time from start to finish of a review. Some triennial factor reviews can become quite drawn out because of multiple decision-makers (e.g., trustee and sponsor required to agree). This could make annual reviews obsolete if the next review starts before the previous one has even been implemented due to delays in decision making.

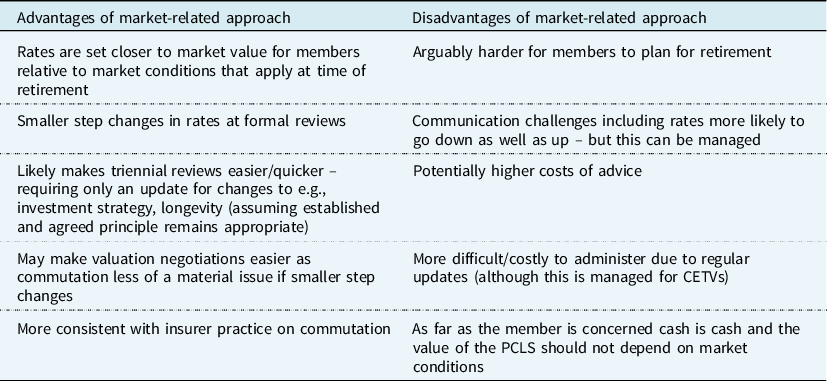

4.3 Market-Related Factors

In general, we would encourage greater consideration for market-related factors, noting the following advantages and disadvantages for market-related commutation rates relative to commutation rates that are fixed between reviews (triennial, annual, or otherwise) (Table 2).

Table 2. Advantages and disadvantages for market-related commutation rates

If commutation rates are market-related or update more regularly, thought will be needed as to whether rates used in retirement quotes are guaranteed for a period (in a similar way to that for transfer values) and the approach to member communications. This was highlighted by the challenges faced in relation to the September and October 2022 market volatility where there were sharp increases in gilt yields.

5. When Should Commutation Rates be Reviewed?

5.1 Introduction

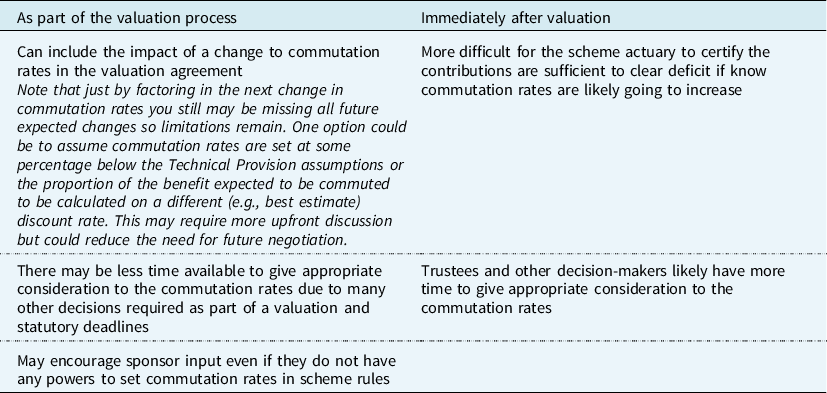

We suggest that there are two obvious times to perform the triennial review of commutation rates (although as noted above we suggest that commutation rates are reviewed more regularly than every 3 years). These times are either as part of the valuation process or immediately after a valuation.

5.2 Further Detail

Further interim reviews should also be undertaken following material events, such as change in covenant, change in investment strategy, or significant change in financial conditions. The relative pros and cons of reviewing terms during or after a valuation include the following (Table 3):

Table 3. Pros and cons of reviewing terms during or after a valuation

6. How Actuaries Should Present Their Review of Commutation Rates to Trustees or Other Decision-Makers

6.1 Introduction

The relevant TASs (TAS 100 in its current form and the soon-to-be effective version 2.0, and TAS 300) already provide actuaries with standards that should be followed when advising on actuarial work, including a review of commutation rates. We do not cover all TAS requirements in this Section and in particular our comments should not be taken as a recommendation to depart from these standards – rather our comments are intended to complement the TASs.

Overall, actuaries should ensure that their advice on commutation rates is clear and concise. It must contain sufficient information to allow the trustees and other decision-makers to reach an appropriate conclusion. As such, actuaries must ensure they consider all information that could affect any decisions and ensure that key information is highlighted appropriately.

6.2 Key Areas

6.2.1 Starting point versus proposed rates

Within their advice, we believe that an actuary should explain their starting point for setting the rates, and then set out clearly any reasons for moving away from this. These reasons could include those covered in Section 3 of this paper.

6.2.2 Member impact

Any change in the commutation rates underlying a scheme will affect monetary value that a member receives as part of their pension commencement lump sum and residual pension. Within their advice, we believe that an actuary should illustrate the impact that changing the commutation rates will have on the amounts received by a typical member. This could be shown in monetary or percentage terms. The actuary should highlight the difference in the amounts received under the current rates, the starting point, and the proposed rates.

6.2.3 Impact on scheme funding

Any change in commutation rates will also have an impact on scheme funding. If commutation has been allowed for in the Technical Provisions, long-term target, or other secondary funding basis, then any change in rates will have an immediate impact on a scheme’s funding position. Where this is the case, it would be preferable to consider the impact of changing rates during the valuation process, as set out in Section 5, to allow the impact to be captured as part of the funding discussions. If this is not possible, the actuary should also show the impact on scheme funding as part of their advice. This is particularly important when a sponsor covenant is weak or under stress, as a change in commutation rates could affect the required pace of funding.

Even where commutation is not allowed for explicitly in a scheme’s funding basis/bases, any change in commutation rates will still have an impact on funding – any increase/decrease in factors will increase/reduce the cost of delivering benefits and the time to reach full funding, all else being equal (though noting a change in commutation rates can change take-up so in practice there is more nuance here). This should be highlighted to clients (trustees or sponsors).

We believe that actuaries should also have regard to a scheme’s long-term target when providing advice on commutation rates. In particular, they should highlight what impact any change in rates may have on the likelihood of a scheme achieving that long-term target and timescales. Actuaries advising sponsors on commutation should also highlight any accounting impact as is relevant.

6.2.4 Basis and factors

Within the advice the actuary should include sufficient detail that would allow an independent advisor to replicate the commutation rates. This would include the underlying key assumptions, as well as a table of the rates themselves. This can be included as an appendix if preferred.

6.2.5 Rules and powers

Within their advice, an actuary should be clear on who has the power to set the commutation rates, who needs to be consulted, and what the role of the actuary is (if any).

If the actuary is required to certify the commutation rates then they should provide their certification in writing. If the eventual rates to be implemented differ from those in the actuary’s initial advice, then we believe a separate written certification of the final rates should be documented and form a component part of the overall advice on commutation rates.

Even if not required to formally certify, in our view it is good practice for an actuary to comment on whether the proposed factors fall within a range that they believe to be reasonable and could in theory certify if required. This gives the trustee and/or sponsor additional comfort or highlights where the terms are outside what the actuary considers to be the reasonable range.

6.2.6 Methods of communication/behavioural considerations

When presenting their advice, we believe actuaries should have regard to how their client may wish to receive any advice and recommendation, and what impact this could have on the decision being taken.

For example:

-

Some decision-makers prefer to be taken through the “story”, others prefer to focus only on key decisions and impacts

-

Some decision-makers may prefer to be given different options and make their own choice; others may prefer a single recommendation

-

A range of recommended rates could be shared rather than a single table

-

Some decision-makers may find a decision easier to take when set in context of something similar – for example the funding cost of an increase in commutation rates compared with the funding cost of changing a different assumption.

-

Some decision-makers may prefer a series of smaller changes to commutation rates rather than a large one-off change.

6.2.7 Actuary advising the sponsor (rather than the trustee)

For the avoidance of doubt, while the style of advice may differ if an actuary is advising the sponsor rather than the trustee, we believe that the recommendations in this paper still apply.

6.2.8 Other

There are a number of other factors that actuaries may consider appropriate to include in advice depending on a decision-maker’s specific circumstances. A number of these are referenced in the Thematic Review. In determining what to include, we believe that having overall regard to the requirement to provide “sufficient information” is key – actuaries should ask themselves whether a user reading their advice and any previous reports’ references, where relevant, would be able to make an informed decision.

7. Conclusion

Our aim in producing this paper is to stimulate debate on this topic and challenging current practices, in order to help members formulate their advice on commutation rates to clients.

To summarise, our conclusions and proposed next steps for actuaries advising on defined benefit pension scheme commutation rates are as follows:

-

Consider the appropriateness of the starting point for a commutation rate to be in line with the scheme’s “CETV” basis, and include any justifications for moving away from this starting point.

-

There are a number of good reasons to deviate from that starting point and we believe actuaries should provide adequate justification when doing so. For example, actuaries should quantify the selection risk observed in their scheme if using this as a justification.

-

In line with the Thematic Review paper we agree that 3 years should be the maximum time between reviews, and, indeed, where commutation rates are not market-related (i.e. updated at least quarterly) actuaries should consider performing a high-level review of commutation rates annually.

-

Market-related commutation rates should also be considered, especially in periods of volatile market conditions.

-

There are good arguments to review commutation rates either following or during a valuation. Reviews should also be carried out when there has been a material change in circumstance with these material changes defined up front.

-

An actuary’s advice on commutation rates should satisfy the TASs. The focus should be on clear and concise advice, with information required to take key decisions clearly set out.

-

Where actuarial certification of terms is required, certification should be clearly provided in writing.

-

Actuaries should illustrate the impact on members of changes in terms, including on the member’s pension commencement lump sum and residual scheme pension.