Introduction

The idea that elected representatives in democracies should adopt decisions ‘in the interest of the represented’ (Pitkin Reference Pitkin1967: 209) is key to the understanding of political representation. To examine whether this ideal is fulfilled in practice, a voluminous literature has investigated the linkage between the behaviour of elected representatives and the opinion of their citizens (e.g. Jones et al. Reference Jones, Larsen‐Price and Wilkerson2009; Lax & Phillips Reference Lax and Phillips2012; Monroe Reference Monroe1998; Stimson et al. Reference Stimson, Mackuen and Erikson1995, Wlezien Reference Wlezien1995; Wlezien & Soroka Reference Wlezien and Soroka2012). Lately, we have seen an increased focus on examining potential inequalities in the representation of different subsets of the population (e.g. Bartels Reference Bartels2018; Elsässer et al. Reference Elsässer, Hense and Schäfer2017; Gilens Reference Gilens2012; Gilens & Page Reference Gilens and Page2014; Peters & Ensink Reference Peters and Ensink2014). In addition, scholars have examined the factors explaining variation in the strength of the opinion–policy linkage, such as the role of political institutions and issue characteristics (e.g. Bevan & Jennings Reference Bevan and Jennings2014, Monroe Reference Monroe1998; Rasmussen et al. Reference Rasmussen, Reher and Toshkov2019; Wlezien & Soroka Reference Wlezien and Soroka2012). Much less attention has been paid to how organised interests affect the linkage between public opinion and policy.Footnote 1 This may seem surprising since the extent to which organised interests affect this linkage speaks to important discussions about their role in democratic governance in both the academic literature and the public debate on whether to regulate their behaviour.

On the one hand, sceptical voices in both the interest group literature and the press shed critical light on the role of organised interests in policy‐making. Organised interests are portrayed as likely to distort the opinion–policy linkage by convincing decision‐makers to take action countering the will of the public for the sake of satisfying special interests (e.g. Olson Reference Olson1971; Schattschneider Reference Schattschneider1960). On the other hand, pluralist voices argue that organised interests may serve to reinforce the linkage by giving voice to public demands for policy change (e.g. Truman Reference Truman1951). Some have even seen organised interests as having the potential to act as a mechanism linking opinion and policy by serving as a transmission belt for channelling the wishes of the public to the decision‐makers (Furlong & Kerwin Reference Furlong and Kerwin2005; Rasmussen et al. Reference Rasmussen, Carroll and Lowery2014).

This study examines whether and when preference alignment between organised interests and the public affects whether policy is congruent with the majority of the public. We draw on public opinion, interest group and public policy literature and theorise that interest group positions influence the weight decision‐makers attach to citizen preferences when making policy decisions. When groups and the public are aligned, the likelihood that the public gets the policy it prefers should generally be higher. However, we expect interest group support to matter most when the public has an interest in changing an existing policy status quo on a policy issue. Changing a policy away from the existing state of affairs is likely to be more difficult than keeping it, since it frequently involves persuading gatekeepers of existing policies to overcome crucial barriers to change (Baumgartner et al. Reference Baumgartner, Berry, Hojnacki, Kimball and Leech2009; Varone et al. Reference Varone, Ingold and Jordain2017). All things equal, alignment between the public and interest groups should therefore make the greatest difference for whether the public gets what it wants when status quo bias must be overcome in order for policy to be consistent with its preferences.

Our study is conducted by linking information on the opinion of organised interests with information on public opinion and detailed coding of policy outcomes on a high number of policy issues. We draw on in‐depth media content analysis of policy debates on 160 Danish and German policy issues on which the population was polled in the period 1998–2010. The polls measure attitudes towards specific policy changes such as the introduction of a new type of tax, change of an existing traffic rule or initiation of an infrastructure project. For each issue, we systematically identify the organised interests that mobilised on the issue, their policy positions and the final policy outcome to determine whether group opinion affects whether policy ends up being congruent with public opinion. To allow sufficient time for new policies to enter the legislative agenda and/or get adopted, we follow each issue until policy change happened or a maximum of four years (for a similar approach, see Gilens Reference Gilens2012).

In contrast to the previous studies looking at group impact on the opinion–policy linkage, we go beyond mapping the opinion of a small set of powerful groups (Gilens Reference Gilens2012; Lax & Phillips Reference Lax and Phillips2012) or relying on counts of interest groups as proxies of group pressure (Bevan & Rasmussen Reference Bevan and Rasmussen2020; De Bruycker & Rasmussen Reference De Bruycker and Rasmussen2021; Gray et al. Reference Gray, Lowery, Fellowes and McAtee2004; Klüver & Pickup Reference Klüver and Pickup2019). Instead, we conduct a detailed media content analysis of the positions of actors in debates on our policy issues. Rather than assuming that certain types of groups defend specific interests (see, e.g., Lax & Phillips Reference Lax and Phillips2012; Klüver & Pickup Reference Klüver and Pickup2019), we measure the policy positions advocated by the organised interests in the media. Our study is thus the first to examine interest group influence on opinion–policy congruence using measures of group opinion from a comprehensive, bottom‐up sample of groups actually appearing on policy issues in the media.

Our findings show that the policy positions voiced by organised interests in the media affect the likelihood that decision‐makers will translate the public's policy preferences into policy. The effect is, however, contingent on whether the public supports changing or maintaining the status quo. The public majority is only strengthened by group support (or weakened by group opposition) in cases where it supports policy change. In the remaining cases where the public prefers keeping the existing state of affairs on an issue, group positions do not matter. Our findings underline the value of paying attention to the interplay between public opinion and organised interests in studies of collective decision‐making and have important implications for our understanding of the role of organised groups in representative democracies.

The opinion–policy linkage

A voluminous literature has shown that government agendas and policy are generally responsive to the demands of their electorate (e.g. Bevan & Jennings Reference Bevan and Jennings2014; Chaqués & Palau Reference Chaqués and Palau2011; Jones & Baumgartner Reference Jones and Baumgartner2004; Jones et al. Reference Jones, Larsen‐Price and Wilkerson2009; Peters & Ensink Reference Peters and Ensink2014; Stimson et al. Reference Stimson, Mackuen and Erikson1995; Wlezien Reference Wlezien1995; Wlezien & Soroka Reference Wlezien and Soroka2012). However, it has also been pointed out that actual congruence between policy and the majority of the public may be far from perfect, and that it varies for different segments of the population and between policy issues (e.g. Brooks Reference Brooks1985; Gilens Reference Gilens2012; Gilens & Page Reference Gilens and Page2014; Lax & Phillips Reference Lax and Phillips2012; Monroe Reference Monroe1979, Reference Monroe1998; Rasmussen et al. Reference Rasmusen, Reher and Toshkov2019).

The role of organised interests has received comparatively little attention in this literature. Some studies integrate organised interests, but do not examine whether these actors affect the opinion–policy linkage. As an example, Jacoby and Schneider (Reference Jacoby and Schneider2001) demonstrate that not only citizens but also organised interests affect government spending in the US states (see also Schneider & Jacoby Reference Schneider, Jacoby and Cohen2006). Similarly, Gilens and Page (Reference Gilens and Page2014) find evidence that the net alignment of powerful organised interests affects the likelihood of policy change on US policy issues. Other studies cast a more critical view on the role of groups. Burstein's study (Reference Burstein2014) of the effect of public opinion and organised interests on US bills, finds little evidence that groups influence policy adoption. Moreover, a recent time series analysis of the influence of media advocacy and public opinion on the dynamics of policy‐making in Sweden raises doubt that any of the two have a strong impact (Rasmussen et al. Reference Rasmussen, Romeijn and Toshkov2018b).

The few studies that go beyond looking at the individual effects of groups and opinion on policy and examine the effect of organised interests on the opinion–policy linkage also find mixed evidence. Some studies use group counts as an indicator of group pressure. As an example, Gray et al. (Reference Gray, Lowery, Fellowes and McAtee2004) incorporate measures of the interest group population and find a small, but positive effect of the size of the interest group community on the relationship between opinion and policy liberalism in the US states in one of the two years examined (Gray et al. Reference Gray, Lowery, Fellowes and McAtee2004). Similarly, Bevan and Rasmussen (Reference Bevan and Rasmussen2020) find that the density of voluntary associations only strengthens the linkage between citizen priorities and policy agendas at the early stage of the policy process. Other studies take a similar approach incorporating either the level of associational engagement (Rasmussen & Reher Reference Rasmussen and Reher2019) or the numbers of organised interests per policy area/issue (Klüver & Pickup Reference Klüver and Pickup2019; De Bruycker Reference De Bruycker2020) into their opinion–policy models.Footnote 2

Instead of associational engagement and group counts, two recent US studies examine whether the alignment of groups affects the opinion–policy relationship. Lax and Phillips find that congruence between the opinion majority and policy on policy issues in the US states is highest if a powerful interest group supports majority opinion (Lax & Phillips Reference Lax and Phillips2012). However, Gilens does not find evidence that the opinion of a selection of influential groups affects the impact of opinion on his policy issues (2012). Both studies focus on the most powerful groups. While Lax and Phillips use the mere presence of specific types of powerful groups in state interest group populations as an indicator of group lobbying in favour/against a policy, Gilens’ measure is based on the public stances of up to 43 powerful US interest groups on the issues.

In this study, we address three shortcomings of the existing literature. First, we focus on how alignment between the public and interest groups influence the opinion–policy linkage, which few existing studies have done. Second, we expand on the relatively crude indicators of groups used in existing research going beyond counts of interest group populations or the opinion of a small subset of groups expected to be the most powerful. Third, we add an important element to the theoretical story by not only considering whether alignment of groups and the public affects this linkage but how its effect varies depending on whether the public supports changing the status quo.

Theoretical framework: Organised interests and opinion–policy congruence

The relationship between voters and decision‐makers can be conceived as a principal–agent relationship (Powell Reference Powell2000). As principals, voters delegate decision‐making authority to elected representatives for a fixed period. Representatives, as agents of their voters, are supposed to act in line with the interests of their principals. Through regularly held elections, citizens can reward or punish their elected representatives based on their performance in office (e.g. Fiorina Reference Fiorina1981; Key Reference Key1966). Assuming that decision‐makers care about re‐election to enjoy the perks of office such as power, prestige and material benefits (Riker Reference Riker1962; Strøm Reference Strøm1990; Strøm & Müller Reference Strøm and Müller1999), they have strong incentives to pay attention to the demands of their voters. However, decision‐makers are not only exposed to voters, but also subject to a wide variety of other constraints.

An important factor, which might affect whether decision‐makers pay attention to public opinion, is the role of organised interests. Governments are regularly confronted with the policy demands of a multitude of organised interests ranging from traditional membership associations, such as business and labour associations, to citizen groups, firms and expert organisations. These groups aggregate and articulate a wide variety of societal interests, such as the interests of automobile producers, farmers or consumers and employ a wide variety of lobbying strategies in order to achieve their policy objectives (e.g. Baumgartner et al. Reference Baumgartner, Berry, Hojnacki, Kimball and Leech2009; Giger & Klüver Reference Giger and Klüver2016; Klüver Reference Klüver2013; Mahoney Reference Mahoney2008; Witko Reference Witko2006).

Organised interests may both make it easier and harder for governments to pay attention to citizen attitudes. In some circumstances, organised interests may have the potential to stimulate the opinion–policy linkage and act as a transmission belt between voters and policy‐makers (e.g. Furlong & Kerwin Reference Furlong and Kerwin2005; Rasmussen et al. Reference Rasmussen, Carroll and Lowery2014). In other cases, their aim is to decrease the attention of policy‐makers to citizens.

We focus on the signal decision‐makers receive from groups in the media, which is an important arena for all types of interest groups when it comes to signalling their views to group supporters and policymakers. By appearing in the media, groups signal commitment to their goals vis‐à‐vis their supporters from which they extract essential resources for survival. Although groups may sometimes prefer to stay out of the media, they typically spend abundant resources on achieving media visibility and figure prominently in the news (Binderkrantz et al. Reference Binderkrantz, Chaqués and Halpin2017; Kollman Reference Kollman1998).Footnote 3 Following this, our argument is that the extent to which decision‐makers pay attention to a given level of public support for policy change depends on the signal they receive from organised interests concerning the desirability of a given policy change in the media.

We argue that the alignment of groups influence the weight decision‐makers attach to citizen preferences. When deciding whether to adopt specific policy changes, decision‐makers have to weigh the benefits of responding to the public against the likelihood of receiving important resources from organised interests. When the positions of the majorities of the public and organised interests do not align, decision‐makers may refrain from being responsive to public opinion fearing this would lead to strong group opposition. For instance, decision‐makers might avoid subjecting firms to tighter regulation that enjoys broad popular support in the population, when that regulation is strongly opposed by the organised interests on the issue.

The role of organised interests affects the calculus of politicians through several mechanisms. First, organised interests can signal support from (important) constituencies that are more likely to care about the issue and can adjust their voting behaviour more than the average citizen. Often groups will thus represent relatively intensely held preferences since their members and supporters care what politicians do on the issues that involve them. Second, politicians might discount the importance of responding to public opinion if they risk losing access to important resources crucial for policy development as well as re‐election. Conversely, the prospects of expanding their resource base when they respond to citizen preferences on policy alternatives that enjoy interest group support might increase their likelihood of translating citizen wishes into policy.

The resources offered by organised interests to policy‐makers include technical information, campaign contributions, economic power and legitimacy (Bouwen Reference Bouwen2004; Broscheid & Coen Reference Broscheid and Coen2007; Burstein Reference Burstein2014; Klüver Reference Klüver2013). Organised interests can, for example, help decision‐makers acquire important, specialised issue‐relevant technical expertise and provide them with crucial information about the preferences of their constituencies (e.g. Austen‐Smith Reference Austen‐Smith1993; Hall & Deardorff Reference Hall and Deardorff2006; Klüver Reference Klüver2013). Having access to technical information is important for decision‐makers, who are frequently confronted with a multitude of highly complex policy proposals. The need to obtain support for electoral campaigns from organised interests is another important resource that can help explain why the opinion of groups counts for decision‐makers when deciding how strongly to weigh public opinion (e.g. Giger & Klüver Reference Giger and Klüver2016; Witko Reference Witko2006).

Importantly, these different resources may not only ensure that organised interests have an independent impact on what policy‐makers decide but may weigh in on their decisions whether to pay attention to the opinion of the public majority. The reason is that the resources which groups offer decision‐makers may be so important for the decision‐makers that the prospects of gaining (losing) them might increase (decrease) the likelihood that decision‐makers will respond to public opinion. Therefore, our first hypothesis argues that policy congruence with the public majority is higher when lobbying by the bulk of the organised interests coincides with the view of the public. For policy‐makers, this setup presents a situation where the most favourable line of action is to comply with demands raised by organised interests and supported by the public. This will both increase their chances of re‐election and ensure that organised interests support them with crucial resources:

H1: The probability of opinion–policy congruence is higher when organised interests on an issue support the public majority.

It is important to note that alignment between majorities of the public and organised interests may occur because they had similar preferences all along, whereas in other cases it occurs because they may have successfully affected the positions of each other (for the literature on the link between groups and public opinion, see e.g. Dür Reference Dür2019; McEntire et al. Reference McEntire, Leiby and Krain2015, Flöthe & Rasmussen Reference Flöthe and Rasmussen2019; Page et al. Reference Page, Shapiro and Dempsey1987). Our study is not designed to examine whether such influence is happening. Instead, our purpose is to examine whether and under which conditions alignment matters irrespective of whether alignment is a priori or not. We expect that the public's value of being aligned with the interest group community on an issue is likely to depend on the obstacles it faces in realising its preferred policy. Most notably, policy positions that require change from the status quo (i.e. the existing state of affairs on an issue) are more difficult to attain.Footnote 4 For a number of reasons, status quo bias is a persistent feature of policy‐making. Experimental studies have, for example, shown that individuals tend to stick to the status quo and have pointed to a number of possible explanations (Samuelson & Zeckhauser Reference Samuelson and Zeckhauser1988). In the case of legislators, cognitive biases towards changing the status quo may, for example, lead them to keep what they know. Even when the public prefers policy changes decision‐makers may therefore not run the risk of adopting the changes, especially not when transition costs are involved. Changing the status quo further requires that the necessary majorities are found in political systems and that gatekeepers of existing policies are persuaded to adopt the changes Reference Varone, Ingold and Jordain(Varone et. al. 2017). This involves organised interests protecting a preferred status quo from change (Baumgartner et al. Reference Baumgartner, Berry, Hojnacki, Kimball and Leech2009). Not surprisingly, US research has therefore pointed out that a major reason for lack of congruence between majority public opinion and policy is exactly the challenge involved in changing policy. It has been found that opinion–policy congruence is higher when the public wants to preserve rather than change the status quo (Monroe, Reference Monroe1979; Reference Monroe1998).

We expect that the public is more likely to depend on being aligned with organised interests in those circumstances where it is hardest for it to influence policy‐making on its own and when opposition from groups may be most harmful, that is when it supports policy change. In such cases, having a public majority supporting change might not in itself provide sufficient ‘leverage’ to get policy adopted and the additional support of groups might be crucial for decision‐makers to be receptive to the views of the citizens. In contrast, in the cases where the public wants to keep the status quo, it may make less of a difference whether groups are also against policy change, since considerable status quo bias makes policy adoption less likely in such cases anyhow. Our second hypothesis therefore suggests that the value for the public of having groups on its side is conditional upon whether it is interested in preserving the status quo or adopting change.

H2: Alignment between the public and interest groups is more likely to increase the probability of opinion–policy congruence in cases where the public majority is interested in changing policy than when it supports keeping the status quo.

Analysis design

Our analysis is based on a pooled sample of 160 specific policy issues in Denmark and Germany for which we have polling data on public opinion and on which media coverage included information about the positions of organised interests. The inclusion of two countries allows us to arrive at a sufficiently large sample of specific issues where public opinion has been measured. Both Denmark and Germany are advanced democratic countries with established systems of interest representation and therefore well‐suited for testing our theoretical arguments. Importantly, the two countries share a number of features that might affect the ability and the incentives of politicians to respond to both media lobbying and public opinion: Both have neo‐corporatist state‐society structures, use proportional electoral systems and tend to be governed by coalition governments. At the same time, they differ with respect to the vertical and horizontal separation of powers with Denmark being a unitary state with a unicameral legislature and Germany having a federal, bicameral structure. Organised interest might potentially exert a greater impact on the extent to which policy‐makers act in line with public opinion in the more complex German institutional system. Here the flow of information between citizens and policy‐makers might be less smooth than in a unitary system (Rasmussen et al. Reference Rasmusen, Reher and Toshkov2019). German policy makers serve divergent communities and are likely to be faced with higher levels of status quo bias in decision‐making structures due to the stronger separation of powers. At the same, organised interests may enjoy additional access points to decision‐makers in the German federal, bicameral system compared to the Danish unitary, unicameral one.

The policy issues stem from polls conducted by Gallup in Denmark and the Politbarometer in Germany in the period 1998–2010, fulfilling two important selection criteria. First, they ask respondents to indicate whether they support making changes in the status quo of specific policies. Second, they fall under national (as opposed to subnational or European Union) policy competence. For example, one of the German issues asks whether wealth taxation should be introduced and a Danish one asks whether military service should stop being mandatory. By setting 2010 as the cut‐off point for the collection of polling data, we make sure that all items in the sample can be followed in a similar period of time in order to examine whether the specific policy change mentioned in the public opinion question was subsequently enacted.Footnote 5 In line with recent research on the United States, we determined whether policy enactment took place within a four‐year period (see Gilens Reference Gilens2012; Gilens & Page Reference Gilens and Page2014). Four years is thus the maximum length of the observation period for a given issue. Using this time frame allows for a timely relationship between our measures of public opinion and policy change as possible while not missing substantial numbers of policy changes (see Online Appendix A for more details). To code whether policy changed, coders relied on official government websites, newspaper archives, legislative databases and information from organised interests. We included the same number of issues from each country in the study to ensure an equally weighted sample of issues.Footnote 6 Our full dataset therefore consists of all the 102 German Politbarometer items from the period that fulfilled the mentioned selection criteria and 102 Danish items, randomly sampled by year from 211 eligible Gallup questions.

Our issues cannot be seen as a random sample of whatever a latent universe of policy issues might look like. Relying on opinion polls probably means that our issues are more salient than average, which might increase the likelihood that politicians are responsive to public opinion (see Burstein Reference Burstein2014). Importantly, however, this does not mean that we would also be more likely to find an impact of groups on the opinion–policy linkage, which is the focus here. Hence, saliency may both benefit and weaken the impact of organised interests depending on whether they are aligned with the public. When groups and the public want the same policy, saliency might be beneficial for groups to put pressure on policy‐makers but in cases where groups are trying to block the public from either keeping or changing the status quo, it might be best to keep saliency low. Moreover, even if opinion polls cannot be regarded as an unbiased sampling frame of the latent population of policy issues, other approaches to sampling issues – for example relying on legislative proposals, issues in the media or asking groups to name issues – are likely to present other types of biases (for discussion, see Rasmussen et al. Reference Rasmussen, Mäder and Reher2018a). In our case, having issues representing a certain degree of saliency has the advantage that it becomes ‘plausible that average citizens may have real opinions and may exert some political influence’ (Gilens & Page Reference Gilens and Page2014: 568). At the same time, our large issue samples display considerable variation in media saliency allowing us to control for saliency in the analyses.

We gather information about the positions of the interest group community in the media by conducting a search for organised interests on the selected policy issues mentioned in two main broadsheet newspapers per country. We used Süddeutsche Zeitung (SZ) and Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung (FAZ) in Germany and Politiken and Jyllands‐Posten in Denmark. Having one right‐leaning and one left‐leaning newspaper per country allows us to control for the possibility that newspapers with different political orientations prioritise coverage of certain groups differently. Organised interests in the newspapers were identified searching electronically for articles that refer specifically to the selected policy issues.

For each of our public opinion items, we drew a random sample of newspaper articles, the size of which was individually calculated for each policy issue in order to fulfil a common and predefined margin of error. Online Appendix A provides further details about the sampling procedure requiring student assistants to read approximately 7,500 articles. After the sample of articles was defined, student assistants were trained to code claims by organised interests in order to measure the policy positions advocated by the organised interests, active on the selected policy issues. Taking not only into account which organised interests mobilised, but also their policy positions is important to understand in which direction organised interests pushed governments (see also Giger & Klüver Reference Giger and Klüver2016).

Despite significant advances in automated coding, we opted for human coding as the most reliable option for identifying and coding statements by organised interests. The coders identified statements by actors on policy issues and recorded the position of the actor on the policy issue and the type of actor.Footnote 7 We use a behavioural definition of organised interests (Baroni et al. Reference Baroni, Carroll, Chalmers, Marquez and Rasmussen2014) including not only organised interests representing members and supporters (e.g. business associations and citizen groups), but also firms and expert organisations. Importantly, this definition also includes formal associations as part of broader social movements (see, e.g., Heaney & Rojas Reference Heaney and Rojas2014). Yet, we exclude individual advocates and actors running for office or representing the political system itself, that is political parties, party officials and civil servants (see Online Appendix B for a list of actor types).

The media is only one arena that comes with specific properties. Relying on newspaper coverage introduces a certain bias in the sample of organised interests as the most important players and those that use highly visible lobbying strategies (e.g. protests or demonstrations) will be more likely to be included in the sample. Smaller organised interests only representing a niche sector of little public importance and a handful of supporters may be less likely to receive attention from journalists. In conclusion, we do not claim to identify the full sample of organised interests mobilised, but we are confident that relying on newspaper coverage allows concentrating on (a) the most important players and (b) those organised interests that use publicly visible strategies.Footnote 8

The dependent variable in our models is opinion–policy congruence, that is whether policy is aligned with the public opinion majority. First, we examine whether the likelihood of opinion–policy congruence is affected by alignment of the public & organised interests, that is whether a majority of the groups are aligned with the public opinion majority (H1). The share of organised interests on an issue supporting change is calculated from the unique actors expressing a position on an issue. It considers organised interests for which we could determine whether they supported or opposed a given policy change. Second, we examine whether the effect of the alignment of the public & organised interests varies depending on whether the majority of public is in favour of changing the status quo by interacting the two (H2). Since our dependent variable is dichotomous, we use logistic regressions.

Our models include a number of control variables. First, we include a variable measuring media saliency. On the one hand, media attention to an issue may make it easier for legislators to receive information about public preferences and pressure them to respond to public preferences (e.g. Lax & Phillips Reference Lax and Phillips2012; Page & Shapiro Reference Page and Shapiro1983). On the other hand, issues where governments adopt unpopular policies may also trigger a lot of media attention, in which case saliency could negatively condition the opinion–policy linkage. We measure media saliency by counting the average number of articles per day about an issue during its observation period in the four newspapers coded. We also control for the number of actors for which we have coded statements to test whether the volume rather than the alignment of organised interests affects policy representation. Both of these are logged since we expect decreasing returns to scale on policy representation as both newsmedia coverage and actor mobilisation increase, and both variables are positively skewed.Footnote 9 We also control for the size of the opinion majority. The latter indicates how large the public majority on an issue is irrespective of whether it supports or opposes change. Hence, we would expect that, the more united the public is, the higher the likelihood that policy is aligned with the public majority (Lax & Phillips Reference Lax and Phillips2012; Rasmussen et al. Reference Rasmusen, Reher and Toshkov2019). Finally, we include fixed effects for year, country and policy type of the issues in all models to control for unobserved heterogeneity between them with respect to these dimensions. For the latter, we use Lowi's (Reference Lowi1972) distinction between distributive, redistributive, regulatory and constituent policies. His main argument is that ‘policies determine politics’ leading to variation in patterns of conflict between issues, which might also affect their level of opinion–policy congruence. Online Appendix C provides summary statistics for our variables.

We found statements on the positions of organised interests in the media articles on 160 of our 204 issues (94 in Germany and 66 in Denmark). Since we need information about actual group positions to test our hypotheses and do not have theoretical grounds for making assumptions about group opinion in cases without group information, our analysis is conducted for these 160 cases. Yet, Online Appendix D shows that we do not have reason to suspect that this biases our results. Comparing the 160 cases to the remaining 44 cases without interest group information, a chi‐square test does not find a significant difference in opinion–policy congruence (see Table D1 in the Online Appendix) between the two subsamples.

Analysis

We present a descriptive overview of the frequency of policy change in our data in Table 1 for the four possible combinations of issues where policy change is either supported or opposed by majorities of the public and/or the organised interests.

Table 1. Frequency of policy change for different preference configurations (percentages in parentheses)

Notes: Positions refer to the majority view of the two communities on an issue. Numbers in bold indicate the cases where the policy is congruent with the preferences of the public.

Overall, policy was congruent with the majority of the public in 86 of the 160 cases with interest group information available (i.e. 54 per cent) in our dataset. Importantly, we have a sizable number of cases where the two communities disagree (68 out of the 160 cases), providing us with ample variation to test whether alignment matters. The data reveal some support for the expectation in hypothesis 1 that, when majorities of groups and the public are aligned, policy is more likely to be congruent with majority public opinion (χ2, = 3.17, p = 0.075). When the public and the groups defend the same position, policy is aligned with public opinion in 55 (i.e. 60 per cent) of the cases. In the cases where they are not aligned, policy is in line with the position of the majority of the public in 31 (i.e. 46 per cent) of the cases.

It is, however, also evident that this effect is driven by the cases where the public is in favour of policy change. In support of hypothesis 2, the public is more dependent on being aligned with interest groups in the cases in which it supports change. In our dataset, policy is congruent with public opinion in a higher share of cases when both the public and interest groups support policy change (64 per cent) than when only the public supports change (37 per cent) (χ2, = 7.14, p = 0.008). In contrast, there is no significant difference in the frequency of policy congruence with public opinion between the scenarios where only the public or both majorities of the public and the interest groups oppose change (χ2 = 0.519, p = 0. 471).

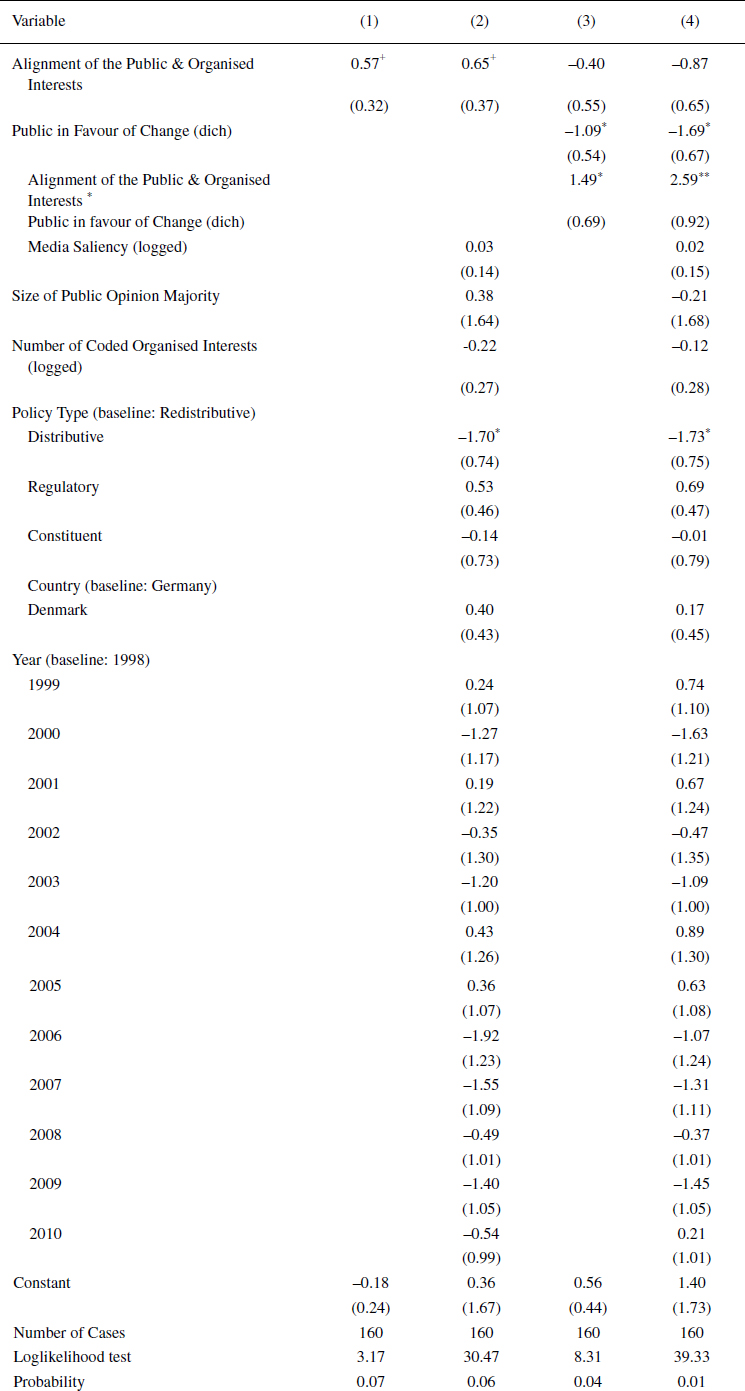

In a next step, we present our statistical models allowing us to control for additional factors when examining these relationships. In the logistic regression of opinion–policy congruence reported in Table 2, congruence is higher when a majority of the organised interests support the public opinion majority as expected in hypothesis 1. The predicted probability of congruence is 60 per cent when a majority of organised interests side with the opinion majority compared to 46 per cent when this is not the case (calculated based on Model 2). However, the effect is only marginally significant at the 0.10 level.

Table 2. Opinion–policy congruence (Is policy congruent with the public opinion majority?) (logistic regression co‐efficients with SEs in parentheses and p‐values)

± p < 0.10,

* p < 0.05.

Models 3 and 4 add an interaction between the variables alignment of the public & organised interests and public in favour of change to determine whether the impact of groups and the public being on the same side on an issue varies depending on whether the public wants to preserve or change the status quo. In line with hypothesis 2, there is a positive interaction between the two variables indicating that opinion–policy congruence is more likely to be affected by alignment between the public and groups when the public supports policy change.

The effect is illustrated in Figure 1. We find that congruence is lower when the public wants change and the organised interests do not, whereas in all other instances, congruence is roughly the same. In line with H2, this indicates that whether organised interests and the public are aligned only makes a significant difference for the likelihood of opinion–policy congruence when the public supports changing policy. In these cases, the predicted probability of opinion–policy congruence with the public opinion majority is 68 (±12) per cent when the public enjoys support from the majority of the organised interests whereas it is 34 (±13) per cent in the remaining cases (Model 4). In contrast, the confidence intervals are widely overlapping when the public supports preserving the status quo, indicating that the extent to which the public is aligned with groups in such cases does not matter. In other words, the key to understanding the role of alignment between groups and the public is whether the public favours a policy change or not. While groups do not matter for the likelihood of opinion–policy alignment when the public is against policy change, alignment with groups is an important asset when status quo bias must be overcome for the public to obtain its preferred policy. Similarly, if the public is in favour of change, while the interest group community favours the status quo, the effect of interest group lobbying may harm the public.

Figure 1. Effect of alignment between groups and public opinion on predicted probability of congruence when the public supports the status quo and policy change (based on Model 4)

The control variables present several interesting findings. Neither the number of organised interests coded nor media saliency increase opinion–policy congruence. In contrast to what we saw in previous research on the US states (Lax & Phillips Reference Lax and Phillips2012), there is no significant impact of the size of the public opinion majority on the likelihood of opinion–policy congruence on our 160 issues. The level of opinion–policy congruence is also not significantly different in the two countries even if they experience different degrees of decentralisation and that the clarity of responsibility might be weaker in federal than unitary systems (Rasmussen et al. Reference Rasmusen, Reher and Toshkov2019). Instead, distributive issues display lower opinion–policy congruence scores than the other policy types. The pressure on decision‐makers to respond to public opinion on these issues may be lower, since such issues have been seen as characterised by a low overall degree of contestation (Lowi Reference Lowi1972). The loglikelihood tests reveal that the best fitting model is Model 4 with a critical value for the chi‐square statistic of 39.33 (df = 22) corresponding to a p‐value of 0.01.

Robustness

Our results are robust to a number of alternative specifications. We included all control variables simultaneously in Models 2 and 4 to control for the various potential factors that might affect opinion–policy congruence. However, the alignment between groups and the public in Model 2 and the interaction between alignment and the public's position in Model 4 remain significant at the 0.10 and 0.05 levels, respectively, when including each control one at a time. We also ran robustness checks excluding the nine cases where the share of citizens supporting policy change is between 47.5 and 52.5 per cent to take uncertainty in the polls into account (see Online Appendix E). These alternative specifications underline the main message. Without these cases, the overall alignment between groups and the public drops further in level of significance but the interaction between alignment and the public's position remains significant. The same picture emerges when we run models calculating the share of the public, not only among respondents expressing an opinion, but including those who answered ‘don't know’ (see Online Appendix F).Footnote 10 The findings are also robust to running our models with alternative policy measures to Lowi's policy types, that is (a reduced version of) the main topics of the comparative agendas projectFootnote 11 or a classification whether costs and benefits of policies are primarily carried by the public or specific interests (see Online Appendix G).

Splitting the samples by country (see Online Appendix H) shows that there is only a significant main effect of advocacy support for public opinion on opinion–policy congruence in the German cases (and in the smaller Danish sample the effect is estimated as negative, but statistically indistinguishable from zero). In both systems, the interaction between alignment and the public's position is positive as expected in hypothesis two but it is only significant in the larger German sample. The differences we observe may be related to the lower likelihood of estimating effects with sufficient precision in our two subsamples, which vary in size (Germany: 94 cases, Denmark: 66 cases). As indicated in our analysis design, they may also result from the fact that groups can potentially make a greater difference in either supporting or weakening public opinion in the German bicameral context where status quo bias can be expected to be higher. Policy action may be harder to achieve where policy‐makers serve divergent communities and there are additional access points for organised interests than in the Danish unicameral system. Nevertheless, whether the conditioning impact of organised interests varies between political systems deserves further attention in future research as data for a higher number of countries becomes available. We also ran a robustness check controlling for alignment between public opinion and government parties for Germany, for which we were able to obtain data from Romeijn (Reference Romeijn2020) and Toshkov et al. (Reference Toshkov, Mäder and Rasmussen2020) on the position of the government parties on the issues. Models H3 and H4 in Online Appendix H show that, while opinion–policy congruence is higher when the majorities of the public and the government want the same, alignment between groups and the public still matters. If anything, the results with respect to the latter look stronger when including this control variable.

Conclusion

This paper adds to debates concerning the effect of public opinion and organised interests on public policy (e.g. Bevan & Rasmussen Reference Bevan and Rasmussen2020; Gilens & Page Reference Gilens and Page2014; Lax & Phillips Reference Lax and Phillips2012). Specifically, we linked organised interests to policy representation by studying how the alignment of organised interests affects whether governmental decision‐makers adopt policies that represent the opinion of the public in a novel study of 160 policy issues in Germany and Denmark. Our analyses supported our expectations that the alignment of public opinion and organised interests matters for understanding the formation of public policy.

Key to our findings is whether the public wants to preserve or change the status quo. We showed that having support (opposition) from the group community is primarily an asset (disadvantage) for the public when it is interested in overcoming potential status quo bias and changing policy. In cases where the public wants to preserve the status quo, the opinion of the group community does not affect the likelihood that policy ends up reflecting its policy positions. These findings are robust to controlling for media saliency as well as other factors that may affect the opinion–policy linkage.

They contribute to the long‐standing debate about the democratic role of organised interests in the literature on interest groups and political representation. Our results show that organised interests have the potential to play a positive role in transmitting the views of the public to decision makers and stimulate responsiveness when they are aligned with citizens and citizens wish to change the status quo. Yet, the other side of the coin is that the absence of lobbying on behalf of the majority position in these cases may serve to suppress the opinion–policy linkage. Depending on the representativeness of organised interests on a policy issue, it may be both comforting and worrying that, whether citizens get what they want, depends on whether they agree with organised interests. Yet, normative defenders of populistic democracy may be keen to learn that it is primarily in the cases where the public is up against status quo bias and aims at changing policies that group opinion is important. In these cases, whether organised interests and the public are aligned can affect whether the public wins or loses.

These findings have implications for several literatures. The fact that public opinion and interest groups can in some situations affect the ability of each other to affect public policy underlines the value of moving away from the predominant practice of studying these explanatory factors in separate communities of scholarship (Burstein Reference Burstein2003, Reference Burstein2014). They also underline the value of linking these areas of scholarship to agenda‐setting theory since alignment between the public and organised interests varies in importance depending on whether the public majority has a preference for changing or keeping the existing policy.

Focusing on media coverage to identify organised interests that mobilised on an issue had several advantages. First, we were able to code the policy positions advocated by organised interests for a large number of policy issues that go back in time, in a reliable way, without being dependent on the memory of respondents in elite interviews. Second, we were not dependent on being able to collect information about stakeholders from formal tools of access on the issues (such as written and oral consultations), which were not used consistently on all issues. Third, rather than restricting ourselves to actual policy proposals tabled (see, e.g. Burstein Reference Burstein2014) we could include issues in our sample, which were never formally introduced by governments or lawmakers.

Yet, despite the advantages of relying on media coverage, there is scope in future studies for expanding our approach to the lobbying efforts made by organised interests in other arenas. This would make it possible to shed light on the respective role of insider contacts to decision‐makers and outsider strategies such as media lobbying (e.g. Holyoke Reference Holyoke2003; Holyoke et al. Reference Holyoke, Brown and Henig2012). Also, follow‐up studies should scrutinise whether and how groups and the public are able to influence each other. Experimental designs offer great potential in this respect and will help in drawing more fine‐grained normative implications of our results. Hence, the fact that we cannot rule out that alignment of groups and the public occurs because of mutual influence between the two, complicates our ability to draw one‐sided normative conclusions based on our findings.

Finally, while we have made an important step forward by presenting the first analyses of the effect of the interest group alignment on the link between public opinion and collective decision‐making outside the United States, future research should extend our analyses beyond Germany and Denmark. Even though these countries share many similarities with other established democracies, there is scope for further comparative research to test the external validity of our findings.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Jeroen Romeijn, Linda Flöthe, Lars Mäder, Stefanie Reher, Wiebke Junk and Dimiter Toshkov for invaluable advice and their substantial role in the larger GovLis project. The paper also benefited from comments received during the ECPR conference in Oslo in 2017, the annual meetings of the American Political Science Association in 2017, the Midwest Political Science Association in 2018 and the Comparative Agendas Project in 2019 as well as from presentations at the University of Geneva, Harvard University, the University of Texas at Austin, Leiden University and the University of Copenhagen. In particular, we are grateful to Frank Baumgartner, Adriana Bunea, Paul Burstein, Marcel Hanegraaff, Michael Heaney, Raimondas Ibenskas, Torben Iversen, Noam Lupu, Yvette Peters, Gijs Shumacher and Chris Wlezien for comments on earlier drafts. Finally we would also like to thank Benjamin Egerod, Miriam Katharina Hess, Simon Hill, Martin Laursen, Steffen Mauritz and Mathias Østergaard for research assistance. Our research received financial support from Sapere Aude Grant 0602–02642B from the Danish Council for Independent Research and VIDI Grant 452‐12‐008 from the Dutch NWO.

Online Appendix

Additional supporting information may be found in the Online Appendix section at the end of the article:

Supplementary Material