Impact statement

With the increasing use of biodegradable plastics, it is urgent to elucidate the effects of microplastics released from these materials on soil carbon cycling. By employing metagenomic sequencing, we found PBAT microplastics accelerated NAG decomposition in soils, by selecting for microbial taxa capable of utilizing both PBAT and NAG. The results demonstrated that carbon-rich BMPs may promote the turnover of amino sugars/microbial necromass to meet microbial N demand, particularly in the soil with a low inorganic N level. This work provides insights into the influence of BMPs on N-containing organic matter stability in soil.

Introduction

With the increase of global plastic production, microplastic pollution caused by plastic fragmentation has become a global environmental issue. Microplastics (MPs) refer to plastics with a diameter of ≤5 mm (Thompson et al., Reference Thompson, Olsen, Mitchell, Davis, Rowland, John and Russell2004), which enter the soil environment through various pathways, such as atmospheric deposition, agricultural film and organic fertilizer application, and wastewater irrigation (Guo et al., Reference Guo, Huang, Xiang, Wang, Li, Li and Wong2020; Lang et al., Reference Lang, Wang, Yang, Zhu, Zhang, Ouyang and Guo2022; Tun et al., Reference Tun, Kunisue, Tanabe, Prudente, Subramanian, Sudaryanto and Nakata2022). MPs can alter soil physicochemical properties, reshape microbial communities and disturb nutrient cycling, posing uncertain threats to soil health and organic carbon stability (Rillig et al., Reference Rillig, AAdS, Lehmann and Klumper2019; Chen et al., Reference Chen, Cao, Zhang, Chen, Liu, Ning and Li2024; Song et al., Reference Song, Liu, Han, Li, Xu, Xi and Lin2024; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Xie, Li, Dong, Li, Guo and Zhou2024). Biodegradable plastics are promising alternatives to conventional plastics (Qin et al., Reference Qin, Chen, Song, Shen, Cao, Yang and Gong2021; Zhou et al., Reference Zhou, Jia, Brown, Yang, Zeng, Jones and Zang2023), whose production is increasing gradually, with polylactic acid (PLA), poly(butylene adipate-co-terephthalate) (PBAT) and polyhydroxyalanoates (PHA) having the highest production capacity (EuropeanBioplastics, 2024). Now, emerging evidence suggests that incomplete degradation of biodegradable plastics can lead to MPs accumulation in the environment (Wei et al., Reference Wei, Bohlén, Lindblad, Hedenqvist and Hakonen2021; Hao et al., Reference Hao, Min, Ju, Zeng, Xu, Li and Shi2024). Due to the relatively high degradability of biodegradable microplastics (BMPs), they are reported to exert a greater impact on soil ecosystem than conventional MPs in a given time frame (Rauscher et al., Reference Rauscher, Meyer, Jakobs, Bartnick, Lueders and Lehndorff2023; Shi et al., Reference Shi, Wang, Peng, Fan, Zhang, Wang and Wang2023). Recently, the environmental effect of BMPs has become a new research focus.

Soil organic matter (SOM) consists primarily of carbohydrates (e.g., simple sugars, starch, cellulose and hemicellulose), N-containing compounds (e.g., proteins and chitin), lignin, fat-soluble substances (e.g., resins and waxes) and some unknown compounds (Paul, Reference Paul2016). As the major terrestrial carbon pool, SOM plays pivotal roles in sustaining soil fertility, enhancing soil aggregation, stimulating microbial activity and mitigating climate change (Hoffland et al., Reference Hoffland, Kuyper, Comans and Creamer2020; Smith et al., Reference Smith, Soussana, Angers, Schipper, Chenu, Rasse and Klumpp2020; Whalen et al., Reference Whalen, Grandy, Sokol, Keiluweit, Ernakovich, Smith and Frey2022). While BMPs contain a large amount of labile carbon, their presence may interfere with SOM mineralization, leading to enhanced greenhouse gas emissions (Lin et al., Reference Lin, Cheng, Kumar, Zhang, Yu, Hui and Shan2025). In the context of accelerated global climate change and increasing recognition of the importance of soil health, it is imperative to enhance our understanding of how BMPs inputs affect SOM decomposition.

While some studies report a negative priming effect of biodegradable macro- and micro-plastics on SOM decomposition, in more cases a positive priming effect is observed (Guliyev et al., Reference Guliyev, Tanunchai, Udovenko, Menyailo, Glaser, Purahong and Blagodatskaya2023; Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Liu, Lin, Kumar, Jia, Tian and Zhu2023; Li et al., Reference Li, Yan, Wang, Ma, Li and Jia2024; Xiao et al., Reference Xiao, Liu, Wang, Xue, Liu, Yu and Yao2024). For instance, in a 18-month field study, PLA films reduced soil organic carbon by 6.4% while increased CO2 emissions by 70.2%, clearly demonstrating a positive priming effect (Hao et al., Reference Hao, Min, Ju, Zeng, Xu, Li and Shi2024). Current research, however, is mainly focused on overall SOM content, leaving significant knowledge gaps regarding component-specific responses. Our previous research revealed that PBAT MPs enhanced the decomposition capacity of SOM components such as hemicellulose, lignin and chitin according to functional gene analysis, and that “N mining” mechanism likely played an essential role in enhanced carbon emission (Chang et al., Reference Chang, Chen, Fu, Zhou, Hua, Zhu, Li and He2024); there is also studies showing BMPs can stimulate enzymes associated with N-containing organic matter metabolism (Zou et al., Reference Zou, Yu, Wang, Liu and Lynch2025). However, still little is known about the effect of BMPs on the absolute content and decomposition process of key N-containing compounds.

Moreover, the mechanisms by which MPs influence SOM decomposition involve the following two aspects: 1) MPs alter soil permeability (Lozano et al., Reference Lozano, Lehnert, Linck, Lehmann and Rillig2021), aggregate stability and carbon flow between aggregates (Li et al., Reference Li, Yan, Zou, Li, Wang, Ma and Jia2025), as well as the content of particulate- and mineral-associated organic carbon (Shi et al., Reference Shi, Tanentzap, Sun, Wang, Xing, Rillig and Wang2025), thereby affecting the stability of soil carbon pool. 2) MPs may serve as new carbon source and habitats, modifying the composition and function of microbiota (Brown et al., Reference Brown, Chadwick, Zang, Graf, Liu, Wang and Jones2023; Liu et al., Reference Liu, Feng, Shen and Zhu2023). In terms of the latter mechanism, BMPs have been reported to enrich microbial genera with diverse C and N metabolic functions (Hu et al., Reference Hu, Gu, Sun, Wang, Liu, Yu and Wang2023), but the relationship between BMPs degraders and SOM degraders remains elusive. We speculate that carbon-rich BMPs would favor degraders capable of obtaining N from SOM, which directly drive changes in N-containing SOM decomposition. Amino sugars, primarily derived from microbial residues and metabolism, are important N-containing compounds in soil (Roberts and Jones, Reference Roberts and Jones2012; Yang et al., Reference Yang, Xie and Ma2023). N-acetylglucosamine (NAG) which is the monomer of chitin and structural component of bacterial and fungal cell walls, is the most common amino sugar (Zeglin et al., Reference Zeglin, Kluber and Myrold2013). Thus, studying the impact of BMPs on NAG degradation and associated microbial changes could provide valuable insights into the response of N-containing SOM components to BMPs.

Given that PBAT is a widely used biodegradable polymer in packaging and agriculture (EuropeanBioplastics, 2024), the effects of PBAT BMPs on NAG degradation in soil were investigated. By combining NAG quantification and metagenomic sequencing, this study aimed to explore the response of NAG decomposition process to PBAT BMPs in two soils with different N availability and to identify microbial taxa involved in NAG and PBAT degradation and their relationship. The findings help to assess the ecological consequences of BMPs input on SOM stability.

Materials and methods

Soil, microplastics and reagents

Two agricultural soils from Nanjing, Jiangsu Province, China (31°53’N, 118°40′E) and Yingtan, Jiangxi Province, China (28°12’N, 116°55′E) with similar pH (5.02 and 5.60) but differing available N levels were used, named as NJ and YT, respectively. The annual average temperatures of the two regions are 15.4 °C and 17.6 °C, respectively. Soils were air-dried, sieved (20-mesh), and stored at ambient temperature. Basic properties of two soils can be found in Supplementary Table S1.

PBAT particles with no additives were manufactured by BASF (Germany). They were sieved to obtain the 20–80 μm fraction, washed with ultrapure water, and dried at 40 °C. Polymer type identification by Fourier transform infrared spectra is shown in Supplementary Figure S1. NAG powder with a purity of ≥98% was purchased from Shanghai Aladdin Bio-Chemical Technology Co., Ltd.

Soil experiment

Microcosm experiment was carried out to examine the effect of PBAT BMPs on NAG decomposition in the two soils. Before use, air-dried soils were placed in beakers, to which deionized water was added to adjust soil moisture to 60% of maximum water holding capacity (WHC). They were pre-incubated in the dark at 25 °C (in an incubator) for 1 week to restore microbial activity. Then, soils were slightly air-dried to lower soil moisture to approximately 40% WHC and were homogenized before mixing with MPs. For NJ soil, PBAT was added at concentrations of 0%, 0.2%, 0.5% and 1% (w/w), while 0% and 0.5% for YT soil, as soil microplastic concentrations range from 0.0055% in nature areas to 6.7% in highly polluted industrial soils (Rillig, Reference Rillig2018). In total, there were 72 samples, with triplicates per treatment and four sampling time points.

The experiment was conducted in 50 mL glass beakers with 30 g soil and PBAT BMPs (dry weight), which were covered with perforated foil and incubated at 25 °C in the dark. Soil moisture was maintained at 60% of WHC. On day 9, the foil was removed to allow water evaporation (approximately 3 mL of water loss). At day 10, NAG solution (3 mL) was added to achieve a final concentration of 0.2% (w/w) in soil. The soils were then further incubated for 40 h (according to the pre-experiment), and rapid consumption of NAG or other amino sugars within one to a few days by soil microorganisms were also recorded in previous studies (Roberts and Jones, Reference Roberts and Jones2012; Shimoi et al., Reference Shimoi, Honma, Kurematsu, Iwasaki, Kotsuchibashi, Wakikawa and Saito2020). Sampling was performed at day 10 (pre-NAG addition) and at 0, 24 and 40 h post-NAG addition. Fresh soils were used for measurement of NAG, available N, microbial biomass carbon (MBC) and microbial biomass nitrogen (MBN), while soils stored at −80 °C for subsequent metagenomic sequencing.

Determination of NAG content in soil

Soil NAG content was quantified using the 3,5-dinitrosalicylic acid (DNS) method (Su et al., Reference Su, Xia and Yao2003). Fresh soil samples (1.0 g) were extracted with 5 mL ultrapure water, which was shaken at 200 rpm for 1 h. After centrifugation and filtration, 0.5 mL of the diluted water extract was mixed with 3.0 mL DNS reagent and 50 μL of 10 M NaOH solution. The mixture was then heated for 5 min in boiling water and cooled immediately. The absorbance was measured at 520 nm. For some samples, the Elson-Morgan colorimetric method, commonly used for amino sugar quantification (Su et al., Reference Su, Xia and Yao2003), was also applied to validate NAG content changes.

Determination of available N and microbial biomass

Soil available N content was quantified using the KCl extraction-colorimetric method (Paliaga et al., Reference Paliaga, Badalucco, Ciaramitaro, Chillura Martino, Gelsomino, Kandeler and Laudicina2025). MBC and MBN contents were determined using the chloroform fumigation-K2SO4 method (Xiao et al., Reference Xiao, Ye, Xiao, Chen, Zhang and Wang2019).

Soil metagenomic sequencing analysis

Metagenomic analysis was conducted for Control and 0.5P treatments at 24 h after NAG addition (when NAG degradation showed great differences between treatments). Microbial phylotypes are reported to respond immediately to labile carbon substrates (Li et al., Reference Li, Kravchenko, Cupples, Guber, Kuzyakov, Robertson and Blagodatskaya2024). Soil genomic DNA was extracted using the FastDNA® SPIN Kit (MP Biomedicals, USA), followed by mechanical fragmentation to an average size of 400 bp. Sequencing libraries were prepared with the NEBNext® Ultra™ DNA Library Prep Kit and subjected to 2 × 150 bp paired-end sequencing on the Illumina NovaSeq X Plus platform at Genesky Biotechnologies Inc., Shanghai, China, generating approximately 10 Gb high-quality data per sample. To facilitate comparison between treatments, gene abundance was normalized as transcripts per million (TPM) (Uritskiy et al., Reference Uritskiy, DiRuggiero and Taylor2018). Data processing parameters are shown in Text S2. Raw sequencing data were deposited into the NCBI SRA database (Accession number: PRJNA1251448).

Functional gene involved in PBAT degradation was analyzed by aligning protein sequences against the customized PBAT hydrolase database (Supplementary Table S2) using DIAMOND (v2.0.15), with minimum 60% amino acid identity, e-value cutoff of 1 × 10−5 and alignment length ≥ 50 residues (Han et al., Reference Han, Teng, Wang, Ren, Wang, Luo and Christie2021). Taxonomic annotation was performed against the NCBI NR database (Segata et al., Reference Segata, Waldron, Ballarini, Narasimhan, Jousson and Huttenhower2012; Buchfink et al., Reference Buchfink, Xie and Huson2015).

Statistical analysis

Data are shown as mean values ± standard deviation. Differences in soil parameters between treatments were analyzed by t-test or ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test. SPSS 26.0 software was used for statistical analysis, and p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Effect of PBAT BMPs on NAG decomposition

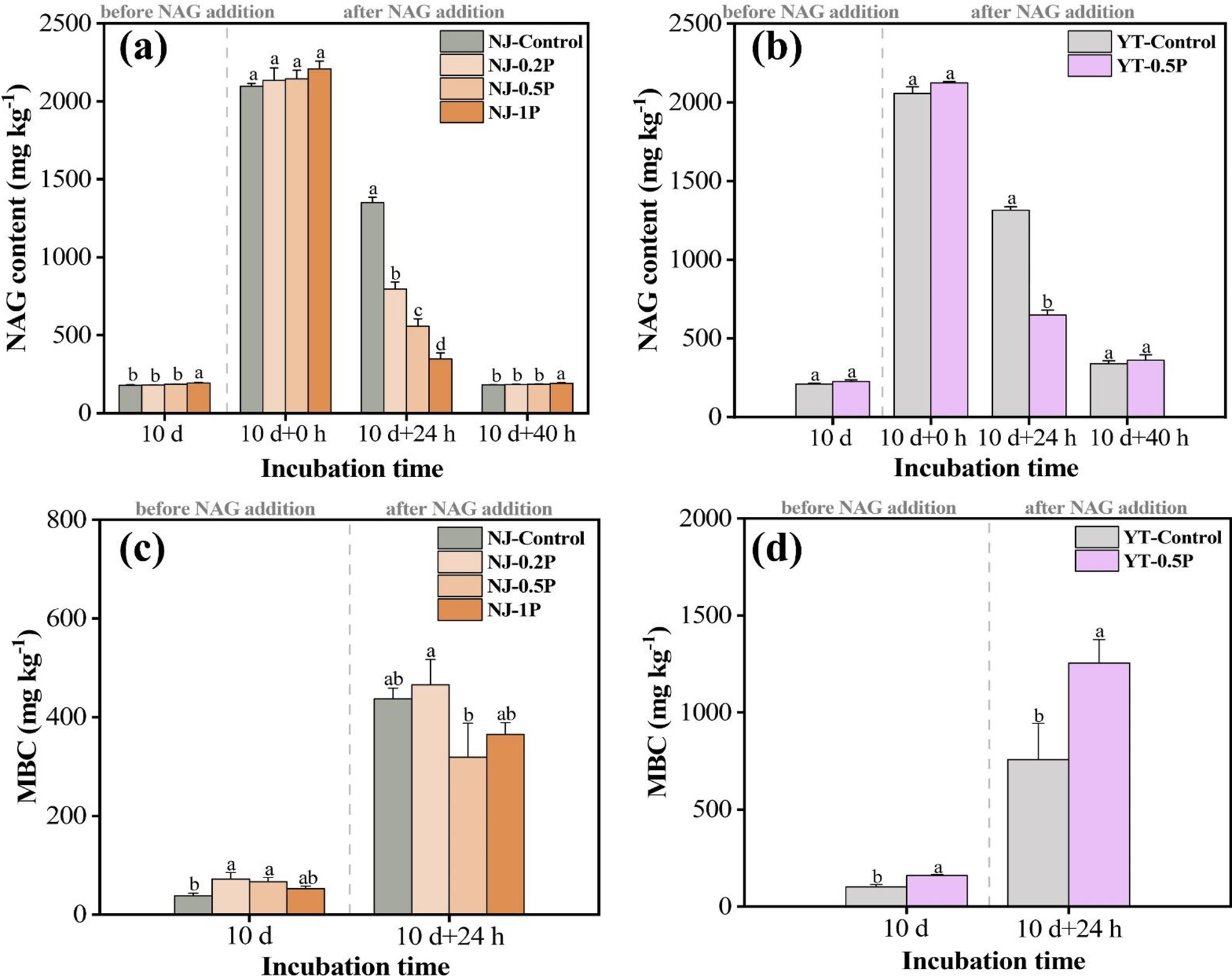

As shown in Figure 1, the background contents of NAG (in soluble form not chitin form) in NJ and YT soils were approximately 200 mg kg−1, and the dynamic equilibrium between microbial NAG production and consumption processes resulted in comparable levels between control and PBAT treatments. To facilitate studying the effect of PBAT BMPs on NAG degradation, soils were supplemented with 2000 mg kg−1 of extra NAG. At 0 h, the NAG content in each soil, after subtracting the background value, was consistent with the theoretical value (2000 mg kg−1), validating the method used for NAG quantification. After 24 h, residual NAG became significantly lower in PBAT-treated soils compared to control soils (0.5% PBAT decreased NAG by about 50%), indicating its degradation was enhanced by PBAT BMPs. Furthermore, NAG degradation in NJ soil exhibited a PBAT concentration-dependent effect, with higher concentrations of PBAT resulting in higher NAG degradation (Supplementary Table S3). By 40 h, the added NAG in all treatments had nearly been depleted, returning to levels close to the background values.

Figure 1. Soil NAG (a and b) and MBC content (c and d). NJ and YT represent Nanjing soil and Yingtan soil, respectively. Control, 0.2P, 0.5P and 1P represent soils with 0%, 0.2%, 0.5% and 1% PBAT BMPs, respectively. Different lowercase letters at the same sampling time indicate significant difference between treatments (p < 0.05). Subsequent graphs are labeled accordingly.

In the supplementary experiment, we compared the effects of PBAT and polyethylene (PE) MPs. Non-biodegradable PE had a much less profound impact on NAG decomposition at equal concentration/size, and lower NAG content in PBAT-treated soils was also confirmed by the Elson-Morgan method (Supplementary Figure S2). The results indicated that PBAT primarily affected soil microorganisms and NAG decomposition through degradation, rather than through modifying soil physical properties by acting as solid particles.

Effect of PBAT BMPs on available nitrogen content

Before NAG addition, the carbon-rich polymer PBAT was found to significantly reduce the NH4+-N and NO3−-N content in both soils (Supplementary Figure S3). After the addition of NAG solution for 24 h, available N content in both soils increased significantly, which could be attributed to the release of inorganic N (e.g., ammonium) from NAG decomposition. At 24 h, PBAT exhibited concentration-dependent regulation of ammonium dynamics in NJ soil, with 0.2% reducing NH4+-N content, 0.5% demonstrating no effects, while 1.0% raising NH4+-N content. It was possibly due to the fact that PBAT promoted NAG decomposition, releasing more inorganic N and compensating for the N immobilized by microbes in PBAT-treated soils. In YT soil, where the background value of available N was low, 0.5% PBAT significantly reduced the content of both ammonium and nitrate nitrogen, suggesting the inorganic N released during NAG degradation was reutilized by microbes.

Effect of PBAT BMPs on MBC and MBN content

Soil MBC dynamics exhibited distinct patterns in response to PBAT and NAG treatments (Figure 1). Before NAG addition, PBAT significantly increased the MBC content of both soils. After an incubation with 0.2% NAG for 24 h, dramatic MBC increases were recorded, which increased from 38–72 to 318–465 mg kg−1 in NJ soil and from 101–160 to 758–1,254 mg kg−1 in YT soil. By comparing the effect of adding NAG solution and adding pure water, we confirmed that MBC increase was mainly driven by NAG degradation (Supplementary Figure S4). The presence of PBAT showed little effect on MBC in NJ soil (p > 0.05), whereas it significantly increased MBC content by 65% in YT soil (p < 0.05), demonstrating a soil-type dependent effect.

Before NAG addition, MBN was very low in both soils (nearly zero), possibly due to a rapid decrease in soil moisture leading to fewer living microbial cells and MBN is usually lower than MBC. After adding 0.2% NAG solution for 24 h, MBN content increased substantially in both soils, especially in YT soil (Supplementary Figure S5), being consistent with the trend of MBC changes. For YT soil, MBN content in the 0.5% PBAT treatment was twofold greater than that of the control, while similar MBN levels were observed among treatments for NJ soil (Supplementary Figure S5). The above results suggest that PBAT promoted the synthesis of new biomass from NAG in YT soil but not in NJ soil.

Effect of PBAT BMPs on soil microbial community composition and functional genes

Overall microbial community composition of soil

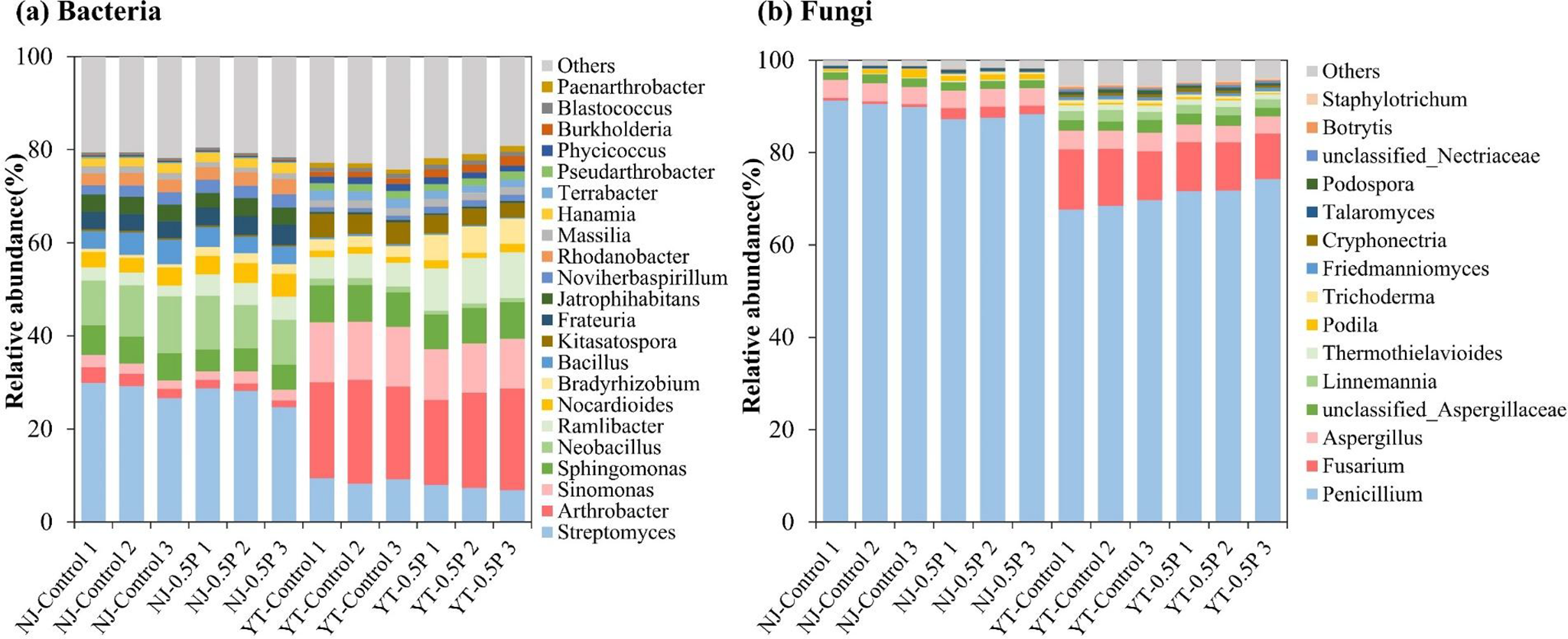

Metagenomic analysis showed that bacteria were the dominant microbial component in both soils (after the incubation with NAG solution for 24 h), being consistent with previous research (Zhu et al., Reference Zhu, Doyle, Zhu, Zhou, Gu and Gao2020; Han et al., Reference Han, Teng, Wang, Ren, Wang, Luo and Christie2021). As shown in Figure 2 and Supplementary Tables S4-S5, the most abundant bacterial genera in NJ soil were Streptomyces, Sphingomonas and Neobacillus, while in YT soil they were Streptomyces, Arthrobacter and Sinomonas. Fungal communities in both soils were overwhelmingly comprised of Penicillium, Fusarium and Aspergillus, representing 85%–95% of total fungal abundance. PBAT BMPs induced similar bacterial alterations in both soils when compared to the control, significantly (p < 0.01) increasing the relative abundance of Bradyrhizobium, Noviherbaspirillum and Ramlibacter. Conversely, fungal responses to PBAT were differing in the two soils: Penicillium abundance decreased substantially (p < 0.05) in NJ soil while increased in YT soil, in comparison to the control.

Figure 2. Relative abundances of bacterial (a) and fungal (b) communities at the genus level across different treatments (with three replicates).

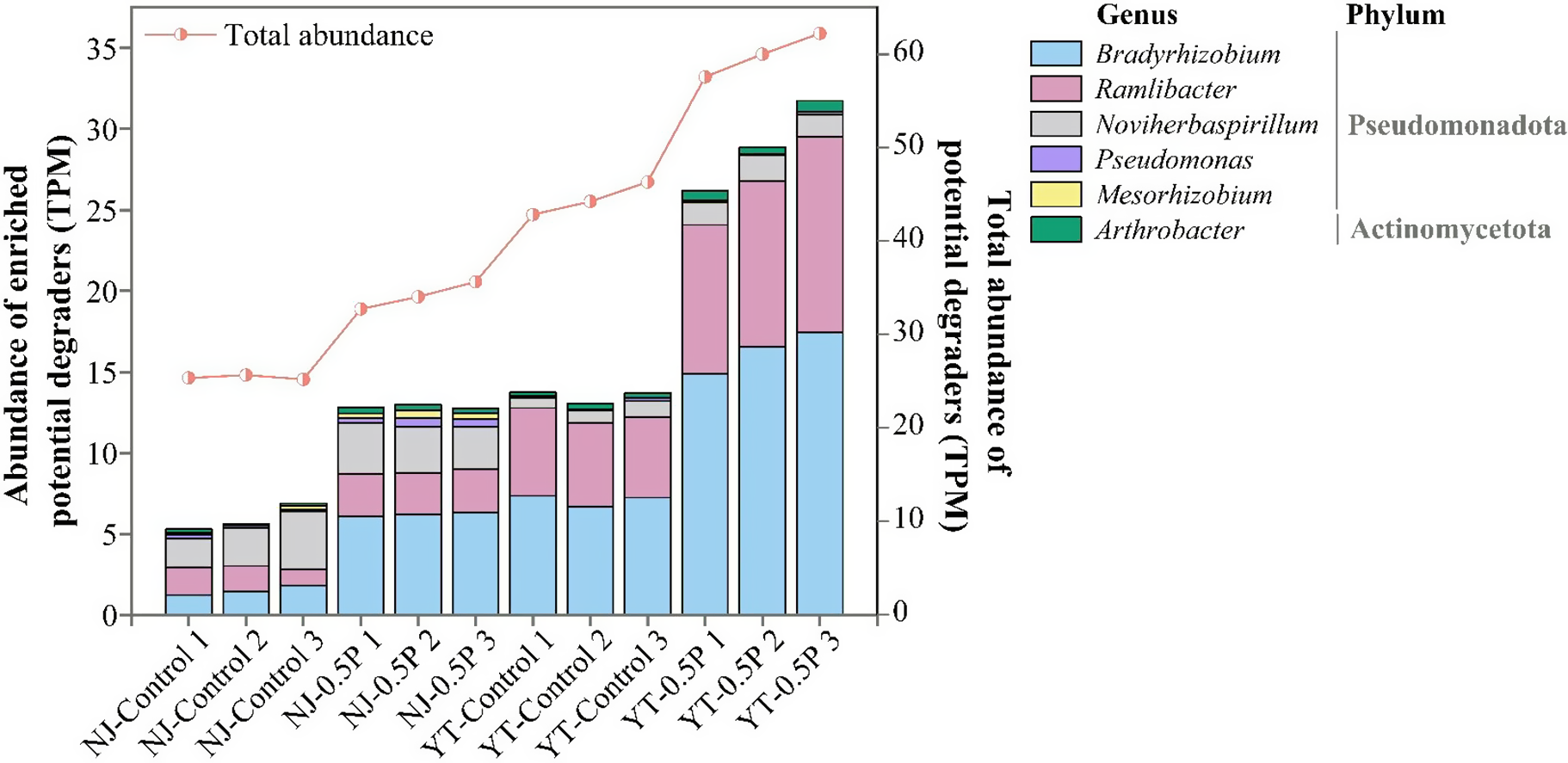

Abundance and taxonomic annotation of PBAT hydrolase genes

Microbial taxa responsible for PBAT degradation in NJ and YT soils were analyzed by aligning sequencing data against 37 reported PBAT hydrolase sequences presented in Supplementary Table S2. The results are shown in Figure 3. PBAT caused a significant (p < 0.05) increase in the relative abundances of PBAT hydrolase genes, by 34.4% in NJ soil and 34.8% in YT soil compared to the corresponding controls, indicating that microorganisms capable of degrading PBAT were enriched in both soils. In two types of soil, the primary PBAT degraders significantly enriched (as compared to the control) were identified to be Bradyrhizobium, Ramlibacter, Noviherbaspirillum, Pseudomonas and Mesorhizobium from the Pseudomonadota phylum and Arthrobacter under the Actinomycetota phylum. Notably, Bradyrhizobium showed remarkable abundance increase (by 181.2% and 81.8% in NJ and YT soils, respectively) in response to PBAT compared with the control soil (p < 0.01). Specific response of these taxa in the two soils can be found in Supplementary Table S6. Fungal contribution was minimal, with scant hydrolase sequences being affiliated with Penicillium in NJ soil but unaffected by PBAT.

Figure 3. Relative abundance of potential PBAT degraders in soil (three replicates for each treatment).

Additionally, we observed significant upregulation of terephthalic acid (PBAT monomer) catabolism genes (tphA2 and tphA3) in PBAT-treated soils. These genes were predominantly associated with Ramlibacter (Supplementary Figure S6), indicating that some genera were involved in the degradation of both PBAT polymer and its metabolite.

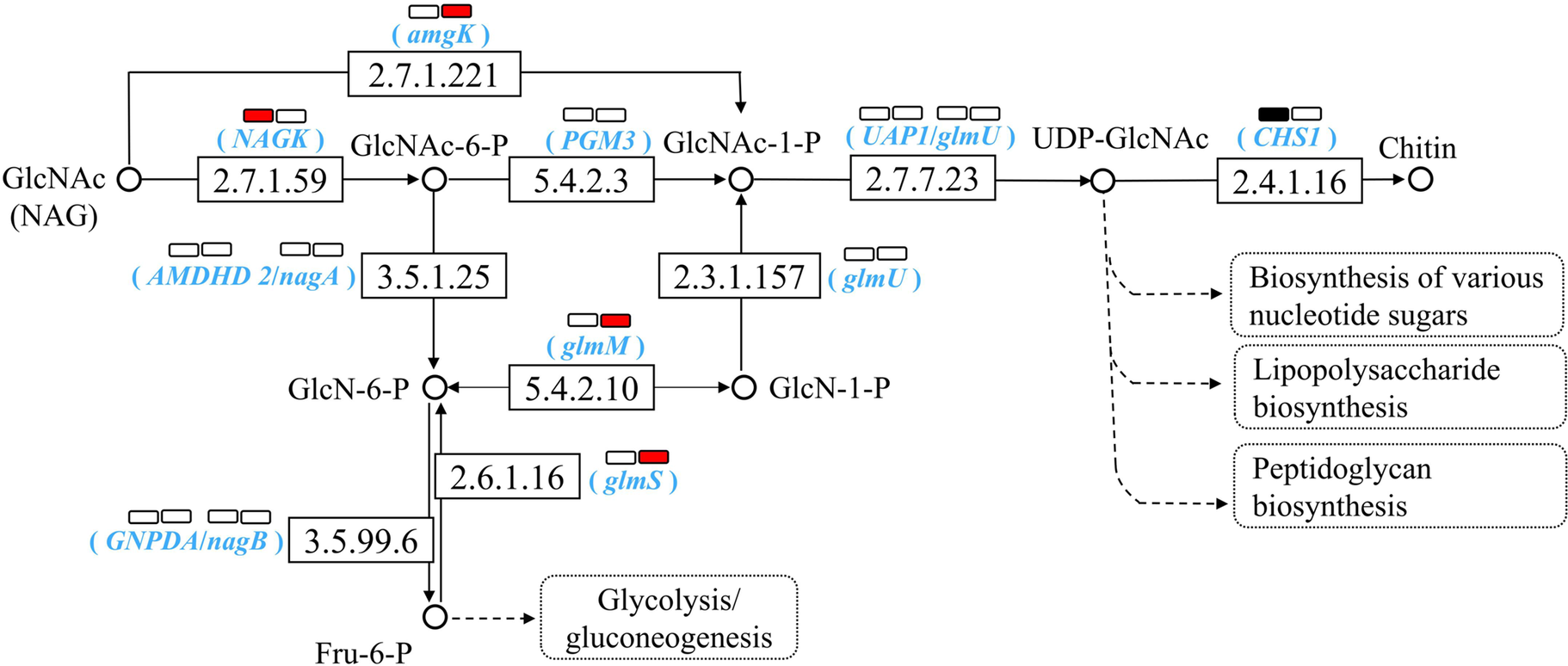

Abundance and taxonomic annotation of NAG degradation genes

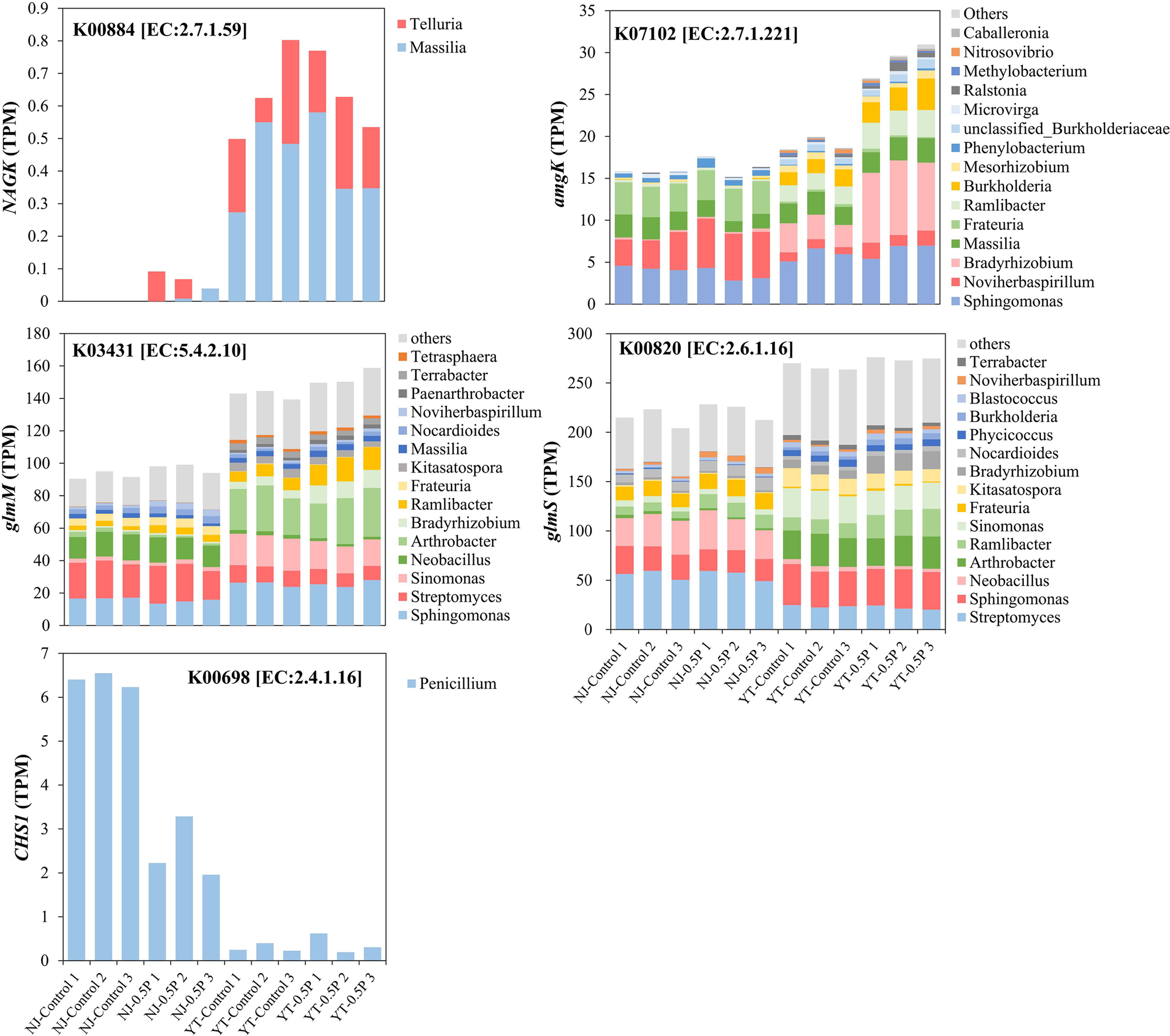

Analysis of NAG metabolic pathways based on KEGG database showed soil-specific PBAT effects (Figure 4). In YT soil, PBAT significantly upregulated key metabolic genes including amgK (mediating direct NAG phosphorylation to GlcNAc-1-P), glmS (mediating the conversion of Fru-6-P to GlcN-6-P) and glmM (mediating GlcN-6-P isomerization to GlcN-1-P for microbial biomass synthesis). Conversely, in NJ soil, PBAT upregulated NAGK gene which catalyzes the transformation of NAG to GlcNAc-6-P, coupled with a significant downregulation of chitin synthase (CHS1). The results are in line with the enhanced NAG degradation in both soils and the increase of microbial biomass only in YT soil upon PBAT addition.

Figure 4. Effect of PBAT BMPs on NAG metabolism pathways based on KEGG PATHWAY Database. The number in the box represents the EC number of the enzyme, while corresponding genes are shown in parentheses. The two rectangles above represent NJ (left) and YT (right) soils. In each soil, the red color of the rectangle indicates a significant upregulation of the corresponding gene after PBAT addition, the black color indicates a significant downregulation, while the white color denotes no significant change.

Taxonomic annotation of NAG degradation genes revealed that Streptomyces, Sphingomonas and Arthrobacter are primary NAG-degrading bacteria (Figure 5), which have been reported to degrade NAG effectively (Nothaft et al., Reference Nothaft, Dresel, Willimek, Mahr, Niederweis and Titgemeyer2003; Mazurkewich et al., Reference Mazurkewich, Brott, Kimber and Seah2016; See Too et al., Reference See Too, Ee, Lim, Convey, Pearce, Mohidin and Chan2017). PBAT BMPs enriched the following genera that were involved in NAG metabolism: Noviherbaspirillum and Ramlibacter in NJ soil, and Bradyrhizobium, Burkholderia and Ramlibacter in YT soil (Figure 5 and Supplementary Table S7). While Burkholderia’s capacity to degrade NAG has been documented (Uroz et al., Reference Uroz, Courty, Pierrat, Peter, Buée, Turpault and Frey-Klett2013), Bradyrhizobium represented a novel candidate. Its phylogenetic relatives Rhizobium and Mesorhizobium are known NAG degraders (Uroz et al., Reference Uroz, Courty, Pierrat, Peter, Buée, Turpault and Frey-Klett2013). Of the four enriched NAG-degrading genera, three were also identified as PBAT degraders, including Bradyrhizobium, Noviherbaspirillum and Ramlibacter (Figure 3), suggesting dual metabolic capacity. Our study links PBAT degraders to NAG metabolism, highlighting their pivotal roles in BMPs-induced alterations in SOM decomposition.

Figure 5. Taxonomic annotation of NAG degradation genes that were affected by PBAT (each treatment with three replicates). The corresponding KO and EC numbers are also shown.

Discussion

Effect of PBAT BMPs on NAG decomposition and transformation

Recent reports show BMPs having a priming effect on the decomposition of soil organic carbon (Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Pei, Zhao, Shan, Zheng, Xu and Wang2023; Lu et al., Reference Lu, Zhang, Sun, Han and Chen2025), but their effects on the transformation of essential SOM components remain unclear. In this study, we found PBAT BMPs significantly enhanced NAG degradation in two soils of different origin. Since NAG mainly originates from microbial residues, the result aligns with a recent report showing PLA BMPs reduced soil microbial residue content (Yang et al., Reference Yang, Ma, Yu, Lv and Tan2025). Collectively, the findings suggest BMPs could accelerate the decomposition of N-containing organic compounds in soil. With respect to NAG transformation pathway, we observed soil-specific responses to PBAT BMPs input, which was related to N availability.

In YT soil with a low background value of available N (6.2 mg kg−1), compared to the control, 0.5% PBAT significantly reduced available N while substantially increasing MBC and MBN after NAG addition. Metagenomic analysis revealed that PBAT upregulated the pathways for the generation of GlcNAc-1-P (key intermediate for chitin and peptidoglycan biosynthesis) from NAG and Fru-6-P, as indicated by increased abundance of amgK, glmS and glmM genes. By looking deeper into the peptidoglycan biosynthesis pathway, we did find an upregulation of genes which mediate the initial steps of peptidoglycan synthesis from UDP-GlcNAc (metabolite of GlcNAc-1-P) (Supplementary Figure S7). These results demonstrated that PBAT BMPs enhanced the transformation of NAG toward synthesizing new microbial biomass. It was possibly because under N deficient conditions the degradation of BMPs (rich in carbon) would exacerbate microbial demand for N (Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Peng, Gao, Wu, Zhang, Wang and Chen2024; Shi et al., Reference Shi, Zhang, Sun, Peng, Wang and Wang2025), and thus the extra NAG (rich in N) decomposed in the presence of PBAT was preferentially used for microbial growth. According to the N mining theory, when carbon availability is high, microorganisms can decompose SOM for additional N at the expense of consuming carbon as energy source (Wang and Kuzyakov, Reference Wang and Kuzyakov2024). Therefore, PBAT-enhanced NAG degradation may result in the consumption of extra organic carbon, thus leading to higher carbon emission. This was supported by a higher CO2 emission in the 0.5P treatment than in the control within 24 h after adding NAG solution (data not shown). The results imply PBAT accelerating the turnover of amino sugars accompanied by a higher carbon emission.

In NJ soil with a high background value of available N (127 mg kg−1), PBAT showed no significant effects on available N, MBC or MBN after adding NAG solution for 24 h. Analysis of NAG metabolic functional gene abundance revealed that PBAT upregulated NAGK (catalyzing the initial phosphorylation step in NAG catabolism) while downregulating CSH1 (involved in chitin synthesis). The results indicated the extra NAG phosphorylated in response to PBAT may enter the glycolysis pathway to generate energy or accumulate as metabolites, rather than utilized for biomass synthesis. This was possibly because in NJ soil microbial growth was not limited by N availability, the extra NAG degraded (or the N released) in the presence of PBAT was not incorporated into microbial biomass. Previous studies also show that N availability modifies the effects of carbon-rich compound or polymers on microbial growth and SOM decomposition (Liao et al., Reference Liao, Tian and Liu2020; Lu et al., Reference Lu, Zhang, Sun, Han and Chen2025). Of course, in addition to N levels, the two soils also differed in soil texture and microbial community composition, which may contribute to the discrepancy of soil-dependent PBAT effects. By comparing the effects of PBAT on NAG degradation and available N in YT soils with or without adjusting available N to the level of NJ soil in a supplementary experiment, we found that N availability is an important factor. As shown in Supplementary Figure S9, 0.5% PBAT BMPs stimulated NAG degradation to a similar extent in YT soil and YT soil with N fertilizer, but it caused a significant (p < 0.05) decrease in ammonium and nitrate only in the YT soil with low N levels, not in the YT soil amended with N fertilizer. The result is in accordance with the effects of PBAT in YT soil and NJ soil in Supplementary Figure S3, indicating N availability modulates the effects of BMPs in soil ecosystems.

Additionally, we noted that for NJ soil (prior to the addition of NAG), 1% PBAT BMPs decreased available N by <10% in the current study while by >90% at 10 d in our previous study (Chang et al., Reference Chang, Chen, Fu, Zhou, Hua, Zhu, Li and He2024). The variation could be attributed to the higher temperature (30 °C) in the former study, possibly resulting in higher PBAT degradation and higher microbial demand for N; moreover, different batches of PBAT MPs were used. The influence of microplastic property and soil temperature on PBAT degradation and its ecological impact requires further investigation.

Relationship between PBAT degraders and NAG degraders

MPs can alter soil microbial communities and functions via physical or biological factor-driven processes (Liu et al., Reference Liu, Suo, Wang, Chen, Wang, Yang and Liu2025; Vainberg et al., Reference Vainberg, Abakumov and Nizamutdinov2025). In this study, PBAT BMPs were proven to affect NAG degradation mainly via its biodegradation-driven process, by comparing its effect with recalcitrant PE MPs. Studies have shown that, high concentrations of BMPs usually exert a greater effect on soil microbiota and nutrient cycling (Thompson et al., Reference Thompson, Courtene-Jones, Boucher, Pahl, Raubenheimer and Koelmans2024; Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Zhu, Zhang, Müller, Wang and Jiang2024). This could explain the faster NAG degradation observed in soils with higher PBAT concentrations in Figure 1.

Then, we further investigated the microbial taxa involved in PBAT and NAG degradation. Taxonomic annotation of functional genes revealed that potential PBAT MPs degraders were primarily bacterial members, consistent with a previous study focusing on PBAT film (Han et al., Reference Han, Teng, Wang, Ren, Wang, Luo and Christie2021). Here, we call it potential degraders, as the information is based on DNA sequences of reported PBAT hydrolase not pure cultures/clones whose metabolic activity could be confirmed. Potential PBAT degraders enriched were mainly from the genera Bradyrhizobium, Noviherbaspirillum and Ramlibacter, which belong to the Pseudomonadales (formerly Proteobacteria). Strains within the Pseudomonadales play a pivotal role in utilizing various monosaccharides and complex polysaccharides, and in efficiently degrading aliphatic and aromatic hydrocarbons (Fan et al., Reference Fan, Gong, Wu, Zhao, Qiao, Wang and Yang2019; Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Zhang, Ouyang, Li, Luo, Li and Yan2021). Currently, only a few studies have identified potential PBAT degraders in complex environments like soil and sediment. With the aid of metagenomic sequencing, the former two studies also documented the predominant role of Pseudomonadota (Han et al., Reference Han, Teng, Wang, Ren, Wang, Luo and Christie2021; Lv et al., Reference Lv, Li, Zhao and Shao2024). Although not yet confirmed to possess PBAT degradation capacity, Bradyrhizobium and Ramlibacter have been reported to enrich in PBAT plastisphere (Han, Reference Han, Teng, Wang, Ren, Wang, Luo and Christie2021; Hu et al., Reference Hu, Gu, Sun, Wang, Liu, Yu and Wang2023). The relative abundance of Bradyrhizobium was higher in YT soil than in NJ soil, possibly due to the low available N content in YT soil, given that it is also well-known as N-fixing bacteria (Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Liu, Lin, Kumar, Jia, Tian and Zhu2023). Since the two soils also differed in other properties such as conductivity, clay content and land use type (Supplementary Table S1), their influence cannot be ruled out. While some studies observe fungal colonization on polyester surface (Kim and Rhee, Reference Kim and Rhee2003; Zumstein et al., Reference Zumstein, Schintlmeister, Nelson, Baumgartner, Woebken, Wagner and Sander2018; Hyde et al., Reference Hyde, Xu, Rapior, Jeewon, Lumyong, Niego and Stadler2019; Yamamoto-Tamura et al., Reference Yamamoto-Tamura, Hoshino, Tsuboi, Huang, Kishimoto-Mo, Sameshima-Yamashita and Kitamoto2020), our results showed few PBAT-hydrolase sequences affiliating with fungi. This discrepancy may be due to differences in the microorganisms capable of degrading polyester under different soil conditions.

Interestingly, three enriched PBAT-degrading genera (Bradyrhizobium, Noviherbaspirillum and Ramlibacter) were also major NAG degraders stimulated by PBAT BMPs, particularly in YT soil with low N availability. These findings supported our hypothesis that PBAT degradation selected for microorganisms that can simultaneously utilize BMPs as carbon source and N-containing organic matter (e.g. NAG) as N source. It means that enriched BMPs degraders directly drive changes in N-rich amino sugar decomposition, when soil N availability is low. In NJ soil with a high available N content, PBAT enhanced NAG degradation by stimulating Telluria/Massilia (catalyzing the initial degradation step) and Noviherbaspirillum (Figure 5). It is still unclear why PBAT BMPs stimulated the NAG-utilizing taxa like Telluria/Massilia. A theory called “stoichiometric decomposition” was previously proposed for the priming effect of carbon input on native SOM under nutrient-rich conditions (high microbial activity under proper C/N ratios is beneficial for SOM decomposition) (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Senbayram, Blagodatsky, Myachina, Dittert, Lin and Kuzyakov2014). Thus, it was possible that PBAT input created favorable conditions for these taxa responsible for NAG degradation.

Furthermore, among the potential PBAT degraders, Bradyrhizobium and Ramlibacter are known to contain N-fixing strains (Hu et al., Reference Hu, Gu, Sun, Wang, Liu, Yu and Wang2023; Zhong et al., Reference Zhong, Hu, Hu, Xu, Zhang and Ning2024). And, in our study, functional genes involved in N fixation was significantly increased by PBAT MPs compared to the control in YT soil (Supplementary Figure S8). These results suggest a potential association between PBAT degradation and soil nitrogen fixation process. Previously, Hu et al. (Reference Hu, Gu, Sun, Wang, Liu, Yu and Wang2023) also reported that in comparison to the bulk soil, the plastisphere of PBAT-based BMPs stimulated the processes of N fixation, as revealed by metagenomic sequencing. In that study, high-quality genome of Ramlibacter strains (which were also more abundant in BMPs-amended soils compare to the control soil) were obtained, providing genetic evidence for their metabolic capacities of N fixation. Collectively, the results further support the hypothesis that BMPs may enrich the microorganisms that could obtain mineral nitrogen from the surrounding environment to sustain their own growth.

Conclusions

To conclude, PBAT BMPs promoted the degradation of NAG in soils, potentially accelerating the turnover of microbial residues. N availability regulated the effect of BMPs on soil microbiota and the transformation of NAG. In the soil with low N availability, enhanced NAG degradation was preferentially utilized for biomass synthesis, while in the soil with high N availability, the extra NAG degraded may be present in the form of inorganic N or metabolized to generate energy rather than being incorporated into microbial biomass. This work also established a link between BMPs degraders and NAG metabolism, providing insights into how BMPs affect the decomposition of N-containing organic matter and thereby the stability of SOM. The study also has limitations. In future studies, 13C- and 15N-labeled chitin can be used to trace the allocation of released C and N, and the regulation effect of N availability also warrants further research, to fully understand the effect of BMPs on the turnover of microbial residues and soil carbon pool. In addition, this study was conducted in a laboratory microcosm system with a relatively short incubation period, and the concentrations of PBAT MPs was set at 0.2–1.0% (w/w) to simulate a high-pollution scenario in agricultural soils, rendering the effect at lower concentrations unknown. Further research examining the impact of BMPs at <0.2% (w/w) on soil organic matter dynamics over a longer period and through field trials would greatly help evaluate their real and long-term effects.

Open peer review

To view the open peer review materials for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/plc.2026.10040.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at http://doi.org/10.1017/plc.2026.10040.

Data availability statement

Data will be made available on request.

Acknowledgements

We thank our editors and anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments and suggestions on this article.

Author contribution

Yifan Zhao: Investigation, writing—original draft. Sha Chang: Investigation, data curation, methodology, writing—review & editing. Ya Li: writing—review & editing. Fengxiao Zhu: Conceptualization, writing—review & editing, funding acquisition. Shiyin Li: Writing—review & editing. Huan He: Writing—review & editing.

Financial support

This work was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant number 42277031).

Competing interests

All authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this article.

Comments

No accompanying comment.