Issues in national politics in 2004

While the war in Iraq dominated the national political debates in many countries in 2003, in 2004 the invasion and its aftermath were on the political agenda in only a handful of countries including Australia, Denmark, Japan, Spain, the United Kingdom and the United States. In the United States, in particular, politics (and indeed most of the presidential election campaign) concentrated on issues of national security and the war on terror. Iraq continued to be associated with the operations of Al‐Qaeda, despite the absence of evidence to substantiate this claim. In most other partners of the ‘coalition of the willing’ the debate focused primarily on the desirability of the continued deployment of troops in Iraq. In the United Kingdom, the government faced external scrutiny over its insensitivity in the handling of an intelligence report on the weapons of mass destruction that ultimately led to the suicide of government scientist Dr Kelly. Events took a dramatic turn in Spain, when just three days before the general elections an Al‐Qaeda‐related network planted a series of bombs in commuter trains, killing nearly 200 people and injuring over a thousand more. On assuming office, the new Socialist government almost immediately withdrew Spanish troops from Iraq.

For the members of the now enlarged European Union (EU), 2004 3 was the year of elections to the European Parliament (EP). In most of the 25 Member States, domestic issues dominated the campaigns and the European elections were little more than second order national elections. Enthusiasm for Europe was at best lukewarm. Turnout was low in the new post‐communist Member States in particular. Slovakia recorded the lowest participation rate, with only 16.9 per cent. In Malta and Cyprus, by contrast, turnout reached high levels of 82.4 and 71.2 per cent, respectively. The lowest turnout in the older democracies was recorded in the Netherlands (39.3 per cent) and the highest in Luxembourg (91.3 per cent) and Belgium (90.8 per cent), both of which have compulsory voting. With the ratification of the treaty approaching, the newly drafted EU constitution – previously notoriously absent from the political debate – appeared as a contentious issue in Denmark, France, Ireland, Luxembourg, Sweden and the United Kingdom. In Austria, Belgium, Germany and the Netherlands, the further enlargement of the EU was a subject of discussion, with concerns raised over the future membership of Turkey.

The reform of the labour market, the welfare state and the public sector continued to be important issues. Ageing populations were a matter of interest nearly everywhere, and negotiations about pension system reform in particular were prominent this year in many countries including Austria, the Czech Republic, Japan, Luxembourg, Norway and Slovakia. Unemployment was a major concern in Finland, Germany, Latvia, Lithuania, Malta, Poland and Sweden, with the older EU members anxious about an influx of cheap labour from the new Member States. Germany, Greece, Hungary, Italy, Japan, Malta, Luxembourg, Sweden and the United States continued to be troubled by economic recession, inflation and budget deficits. Countries in the euro‐zone often struggled to comply with the criteria of the Maastricht Treaty.

Issues of immigration and asylum surfaced in Austria, Germany, Sweden and the United Kingdom, in part in relation to the question of whether or not to impose restrictions on immigration for the new EU Member States to protect domestic employment. Questions of citizenship were important in Hungary, Ireland, Slovakia and Slovenia, each organising a referendum on the issue, as well as in Luxembourg. The politics of ethnic and religious minorities continued to constitute a major concern for the Netherlands, New Zealand, Slovakia and Slovenia. In the Netherlands, the problems of multiculturalism culminated in the assassination of the controversial film producer Theo van Gogh, presumably stimulated by his criticism of the position of women in Islam. Political and financial scandals now seem part of ordinary politics and were prominent this year in Belgium, Canada, Estonia, Greece, Hungary, Israel, Italy, Lithuania (following the successful impeachment of the president), Malta and Poland.

The changing composition of cabinets

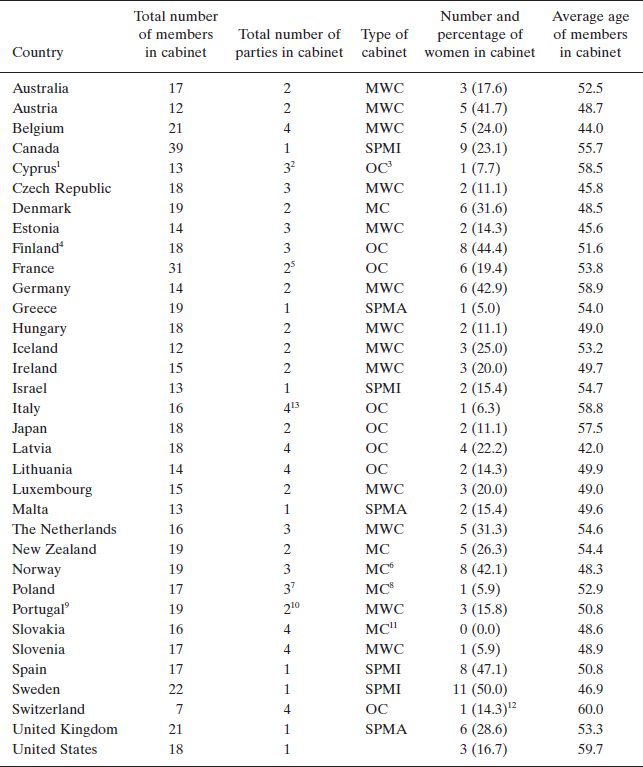

Figures on the composition of the cabinets as they were at the end of 2004 are summarised in Table 1.

Table 1. Number of parties in cabinets, type of cabinet and age and gender of cabinet members on 31 December 2004

Notes: 1 Figures for Greek Cypriot cabinet. 2 Plus four independents. 3 Erratum to 2003: Cabinet is OC. 4 Erratum to 2003: The Finnish cabinet on 31 December 2003 consisted of three parties and included eight women (44.4 per cent). 5 Plus one independent. 6 Erratum to 2001–2003: Cabinet is MC. 7 Plus eight independents. 8 Erratum to 2003: On 1 January 2003, the Polish cabinet was an OC with three parties, and on 31 December 2003 the cabinet was an MC with two parties. 9 Figures for 2 December (resignation cabinet). 10 Plus one independent. 11 Erratum to 2003: The Slovak cabinet on 31 December 2003 was an MC. 12 Erratum to 2003: The Swiss cabinet on 31 December 2003 included one woman (14.3%). SPMA=single‐party majority government. SPMI=single‐party minority government. MWC=minimum‐winning coalition. MC=minority coalition. OC=oversized coalition. 13 Plus 4 independents.

In 2004, there was small reduction in the number of minimum‐winning coalitions. At the end of the year, 13 governments had this format, with an additional three having single‐party majority governments (which are by definition minimum‐winning). These figures were down from 2003, when 14 of the 33 parliamentary or quasi‐presidential democracies in that year's Yearbook had a minimum winning coalition while five had a single party majority government.Footnote 1 The governments in both Latvia and Lithuania changed from minimum‐winning to oversized coalitions, while in Slovenia the new minimum‐winning cabinet replaced the previously oversized coalition. The number of oversized coalitions in 2004 remained stable at eight; the number of minority coalitions remained at five. In 2003, Sweden was the only country with a single‐party minority government; at the end of 2004, there were four countries with this government format. In Canada, the Liberal Party lost its majority status in Parliament after the general elections and continued as a minority government; the conservative majority government in Spain lost the elections to the Socialist Party, which, however, failed to obtain a parliamentary majority; in Israel, the coalition partners of Likud abandoned the government, leaving the cabinet as a single‐party minority government. The number of single‐party governments now stands at seven – or just over 21 per cent – compared to six in 2003.

The proportion of women included in cabinets increased in 11 countries, including some quite substantial increases in Austria and again in Spain, where, as in the previous year, the number of women in cabinet doubled. Most increases were caused by the addition of new female ministers, the notable exception being Israel, where the actual number of women in the government went down (from 3 to 2) but their proportion increased (from 13.0 to 15.4) as a result of a significant decrease in the size of the cabinet (from 23 to 13). Sweden remains the country with the highest proportion of women and is also the only country with a complete gender balance in cabinet. The proportion of women in cabinet fell in 11 countries, in most cases (with the exception of the Czech Republic and Hungary) as a result of a reduction of the actual number of women. For the third year running, Slovakia is the only country included in the Yearbook to have no women in cabinet.

With an increase of only a few months, the average age of cabinet members changed very little compared to last year. At the end of 2004, Switzerland was the country with the oldest cabinet, with an average age of 60.0, replacing long time number one Japan, which is now placed, with an average age of only 57.5, sixth in the age ranking, after not only Switzerland, but also the United States (59.7), Germany (58.9), Italy (58.8) and Cyprus (58.5). Latvia continues to have the youngest cabinet, although the gap between the new and old democracies might be closing. With an average of 42.0 years the Latvian government has aged almost two years compared to last year, although it is still younger than the youngest cabinet in the older democracies (Belgium, with an average of 44.0).

The format of the Yearbook

The data on issues and on the composition of cabinets form only a part of the information gathered in this Yearbook, which covers the period from 1 January 2004 to 31 December 2004. As in the earlier editions, each country report is broken down into a number of sections, with an emphasis on the inclusion of comparable, systematic data.

In preparing each volume, a detailed outline of the headings under which material was to be gathered was provided to each of the authors of the country reports. This outline can be summarised as follows:

-

1 National election results

-

1.1 General elections to the (Lower House of) Parliament

-

1.2 Presidential elections (popular elections only)

-

1.3 Elections to the European Parliament

-

1.4 Changes in the composition of the Upper House

-

1.5 Analysis of the election(s)

-

-

2 Cabinets

-

2.1 Cabinet composition

-

2.1.1 Party composition

-

2.1.2 Cabinet members

-

-

2.2 Changes in the cabinet

-

2.2.1 Resignation, or end of cabinet

-

2.2.2 New cabinet

-

-

2.3 Changes in the cabinet (personnel changes, etc.)

-

2.4 Analysis of cabinet changes

-

-

3 Results of national referenda

-

4 Institutional changes

-

5 Issues in national politics

At the same time, it is obviously the case that not all of these headings will necessarily be relevant to every country in every year. In any one year, for example, it is likely that only a minority of countries will have held general elections, while an even smaller set of countries will be likely to have held national referenda or to have undergone major institutional changes. Elections to the EP obviously only occur in Member States of the EU. In the subsequent reports, therefore, the absence of a heading simply indicates the lack of relevance of that particular topic. On the other hand, there are some headings that are always relevant, and will always be included. Finally, for ease of presentation, reports under some of the headings have been collapsed together, as, for instance, when the report of a general election also incorporates an analysis of the formation of a new government as well as a discussion of the issues in national politics.

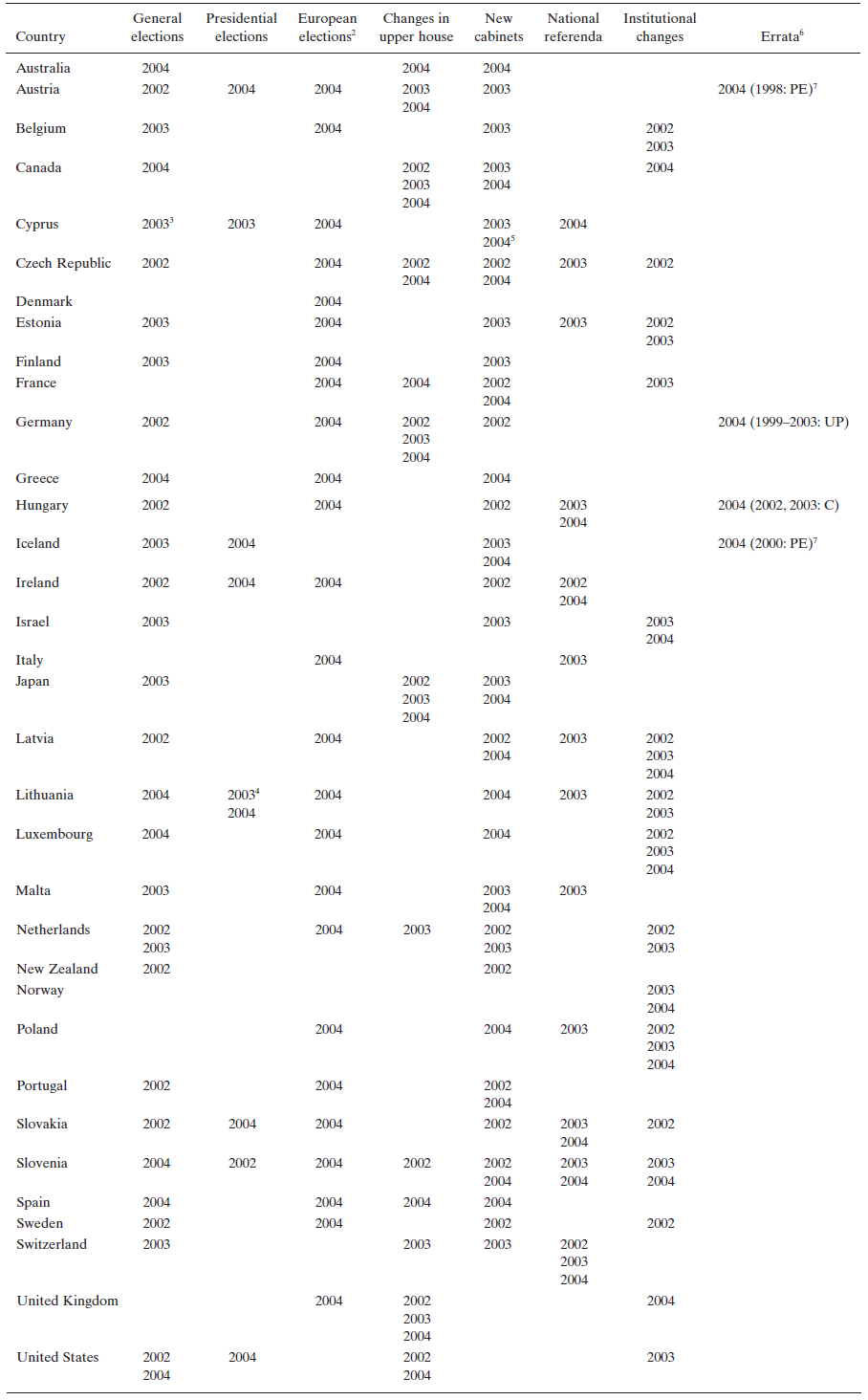

As far as developments in 2004 are concerned, all of the country reports include information regarding cabinet composition and issues in national politics. Relevant data under the more ‘variable’ headings (i.e., under those headings that are not necessarily relevant to each country), on the other hand, are reported for the following countries:

General elections to the Lower House of Parliament:

Australia, Canada, Greece, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Slovenia, Spain, United States

Presidential elections:

Austria, Iceland, Ireland, Lithuania, Slovakia, United States

Elections to the European Parliament:

Austria, Belgium, Cyprus, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malta, Netherlands, Poland, Portugal, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, United Kingdom

Changes in the composition of the Upper House of Parliament:

Australia, Austria, Canada, Czech Republic, France, Germany, Japan, Spain, United Kingdom, United States

New cabinets:

Australia, Canada, Cyprus (Turkish Cypriot cabinet), Czech Republic, France, Greece, Iceland, Japan, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malta, Poland, Portugal, Slovenia, Spain

Results of national referenda:

Cyprus, Hungary, Ireland, Slovakia, Slovenia, Switzerland

Institutional changes:

Canada, Israel, Latvia, Luxembourg, Norway, Poland, Slovenia, United Kingdom

Table 2. ‘Variable’ headings, 20041

Notes: 1For a cumulative index, 1991–2001, see Katz & Koole (2002: 890–895). 2 Direct elections to the European Parliament. 3 Elections in the ‘Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus’. 4 Second round of presidential elections. 5Turkish Cypriot cabinet. 6 PE = presidential elections; UP = changes in upper house; C = cabinets. 7Omitted from cumulative index in Katz & Koole (2002).