Introduction

The Department for Business Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS) stated that their priority in 2022–2023 was to lead Britain’s recovery post Covid-19, by supporting the performance and growth of small and medium enterprises (SMEs). To achieve this, a UK government funded national training programme, called Help to Grow Management (HtGM) was introduced in the March 2021 Spring Budget (Department for Business Energy & Industrial Strategy (BEIS), 2022), aimed to improve leadership, management skills and firm level productivity for SMEs post-Covid-19 recovery. The programme provides education and training to address gaps in business knowledge and is delivered by the Small Business Charter schools, acting as a conduit between business and government interventions. A second round of the programme commenced in April 2025, continuing support for SME growth in the light of increasing competition, globalised trading and technological advancements.

SMEs play a crucial role in the economy as important contributors towards a knowledge-based economy, where targeted initiatives have a positive impact at individual level and the wider locality in which they operate (Clifton, Huggins, Morgan & Thompson, Reference Clifton, Huggins, Morgan and Thompson2015). However, the SME sector is characterised with less work-based provision and participation in government training schemes (Jones, Beynon, Pickernell & Packham, Reference Jones, Beynon, Pickernell and Packham2013) compared to larger organisations. SME policy programmes typically focus on growth (Autio, Kronlund & Kovalainen, Reference Autio, Kronlund and Kovalainen2007; OECD, 2010); therefore, successive UK governments have provided various policies and programmes to support SMEs, but provision is still noted as an issue (Clifton et al., Reference Clifton, Huggins, Morgan and Thompson2015). To enhance competitiveness and growth requires funding and human resource support, and this poses significant challenges for SMEs. Moreover, developing their growth potential can be difficult as they are not a homogeneous group, demonstrating different characteristics and requirements, such as sector, industry, size, or maturity, which influences how their organisation will learn (Short, 2019). Hence, as learning is a multi-dimensional approach that leads to changes in behaviour and/or increased skill levels (Stabile & Ritchie, Reference Stabile and Ritchie2013), any formal training programme designed to be beneficial for SMEs must meet their specific needs in an appropriate and accessible manner (Clifton et al., Reference Clifton, Huggins, Morgan and Thompson2015; Kmecova & Gavura, Reference Kmecova and Gavura2024).

The challenge for HtGM is to provide a formal, growth-oriented training programme that has a positive impact on improved performance and growth in the context of SME business. The dominant learning method for SME programmes is experience-based learning (Bager, Jensen, Nielsen & Larsen, Reference Bager, Jensen, Nielsen and Larsen2015), but this must be supplemented with formal training, as SME manager competences remain lower that those managers in larger companies (OECD, 2010). Quarterly and yearly reports by the Department for Business and Trade (DBT), working in partnership with the Institute for Employment Studies (IES) provide a comprehensive review on how the HtGM aims and objectives have been met. Nevertheless, although there is some self-reporting from qualitative evidence and case study examples from business school providers, there is an absence of empirical research that explores tangible and intangible benefits attributed to the support programme as a result of participation (Singerman & Voytek, Reference Singerman and Voytek2023). Consequently, this is needed to validate the DBT's findings to ensure that the programme’s rationale and delivery methods are meeting the requirements of SME needs and supporting their objectives and priorities for growth. Therefore, this qualitative study provides self-reported data as a comparative, exploratory approach that will add to our understanding of whether the programme has an impact on, and has satisfied SMEs needs on how to upskill for growth.

This research study aims to examine how the HtGM programme has supported improvements to SMEs' own management practices (Ton, van Rijn & Pamuk, Reference Ton, van Rijn and Pamuk2023) and how the government’s intention to develop their strategic leadership skills, increase resilience, innovation, and growth within their organisations (SBC, Reference Costin, O’Brien and Hynes2025) has been realised. Motivated by the need to verify the evaluation report findings, this study’s qualitative findings are triangulated with the DBT data, adding in-depth observations to the independent evaluations conducted by Ipsos for the DBT and IES. This will provide a more comprehensive understanding of the programme’s training methods, initiatives and outcomes, so that improvements can be recommended for future impact.

Two research questions are examined:

1. How has HtGM training supported the development of knowledge, skills, and confidence for SME leadership capability?

2. To what extent has HtGM increased awareness of SMEs’ business performance and long-term growth plans as a result of their participation in the programme?

The paper is presented as follows. First, literature on SME management training and their economic importance for growth is discussed. Second, the HtGM training programme is briefly described to provide context for comparative purposes. Third, the sample and qualitative methodology used for data collection and thematic analysis highlights how the design provides key insights of individual and business level development outcomes. Fourth, findings illustrate whether this study’s results, compared to the HtGM programme evaluation and progress reports, have a significant impact on the development and effectiveness of the intended outcomes. Finally, the conclusion, contributions, and implications for policy and practice are discussed with recommendations made for future research.

Literature review

SMEs are defined by the UK government as a business employing 0–249 people, including sole traders, with less than or equal to £44 m in annual turnover or a balance sheet total of less than or equal to £38m (GOV.UK, 2025). SMEs represent about 90% of all businesses and more than 50% of employment worldwide, contributing up to 40% of national income (GDP) in emerging economies (World Bank, 2024). Notably, they are crucial for local economic development, supporting financial resources, services and technologies that can address global challenges (McKinsey & Company, 2022). Yet, despite the fact that there is a large body of literature that demonstrates how training enhances workforce capability and how it has a positive influence on business performance (Atiase, Wang & Mahmood, Reference Atiase, Wang and Mahmood2023; Bager et al., Reference Bager, Jensen, Nielsen and Larsen2015; Idris, Saridakis & Johnstone, Reference Idris, Saridakis and Johnstone2023; Jones et al., Reference Jones, Beynon, Pickernell and Packham2013; Moon, Birchall, Williams & Vrasidas, Reference Moon, Birchall, Williams and Vrasidas2005), training development continues to be a challenge for SMEs.

Managerial training can be defined as ‘the systematic acquisition of concepts, skills, and attitudes by managers to increase their performance and give a competitive advantage to the SME’ (Atiase et al., Reference Atiase, Wang and Mahmood2023, p1808). Particularly at managerial level, training improves the effectiveness of decision-making and ability to create competitive advantage for SMEs (Sahni, Reference Sahni2020). Organisations that invest in structured training programmes frequently exceed productivity, innovation and employer satisfaction, compared to similar businesses (Noe, Clarke & Klein, Reference Noe, Clarke and Klein2014). Yet for SMEs, a lack of resources required for managing innovation, marketing and training can act as a barrier to growth (Clifton et al., Reference Clifton, Huggins, Morgan and Thompson2015; Moon et al., Reference Moon, Birchall, Williams and Vrasidas2005). Notably, Westhead and Storey (Reference Westhead and Storey1996) demonstrate that resources limit a small firms’ ability to engage in management training, despite a positive correlation between training and the bottom-line performance of small firms. Moreover, recent studies (Idris et al., Reference Idris, Saridakis and Johnstone2023; Panagiotakopoulos, Reference Panagiotakopoulos2020) indicate a positive relationship between management training and small firm performance. Evidence from the HtGM evaluation reports also suggest a link between management training and improved performance. This infers that SMEs should strive to participate in self-development initiatives, despite a perceived lack of added value (Bager et al., Reference Bager, Jensen, Nielsen and Larsen2015), or contextual challenges on how it will be implemented (Clifton et al., Reference Clifton, Huggins, Morgan and Thompson2015).

Management training for SMEs

Human capital theory and managerial capability development proposes that investing in an educational programme for upskilling managers and leaders of small businesses will assist SMEs in achieving competitor advantage and long-term sustainability, by improving an employee’s capability to perform tasks. The human capital theory (Becker, Reference Becker1993) highlights the role that employee skills and abilities play, developed through training and education. Regarded as SMEs ‘main and valuable assets’ (Kmecova & Gavura, Reference Kmecova and Gavura2024, p. 52, targeted training and development programmes promote the development of new knowledge required for competitive advantage (Li, Su & Zhang, Reference Li, Su and Zhang2018). However, Barbosa (Reference Barbosa2020) proposes that both cognitive and non-cognitive skills are required to achieve this, noting that the capability of the manager changes the emphasis from the resources that SMEs have, and can access, to how these resources are used effectively to develop a skilled workforce (Atiase et al., Reference Atiase, Wang and Mahmood2023). As competences become leadership capabilities through training and practice, formal training, such as HtGM, provides the foundational knowledge framework for development.

Government training interventions typically focus on developing a skilled workforce for economic benefit (Devins, Gold, Johnson & Holden, Reference Devins, Gold, Johnson and Holden2005). Generally, performance improvements are measured via enhanced productivity, quality, labour turnover, and financial results. For HtGM, the report evaluations show similar measures. However, Jones et al. (Reference Jones, Beynon, Pickernell and Packham2013) argue that there is still disagreement on which form of training has the greatest impact, citing that more research is needed to explore methods and their impact. In addition, they conclude that government training programmes are typically perceived by owner managers as lacking in value. Furthermore, weak links from training to performance make investment in the programme unattractive (Storey, Reference Storey2004). Thus, government interventions must address these issues if they wish to achieve effective outcomes.

Despite the fact that SMEs may not fully appreciate the benefits training brings to productivity and profitability measures (Aragon-Sanchez, Barba-Aragon & Sanz-Valle, Reference Aragon-Sanchez, Barba-Aragon and Sanz-Valle2003), research by Idris et al. (Reference Idris, Saridakis and Johnstone2023) shows that on and off-the-job training is significant and positively related to SMEs' perceived actual and intended performance. In addition, research conducted by Panagiotakopoulos (Reference Panagiotakopoulos2020) indicates that ‘small firms managed by a well-trained owner/manager seem to have better organisational performance’ (p. 255). This highlights the importance of management training for improving performance.

Effective leadership measures encompass the competency model (Boyatzis, Reference Boyatzis1982; Ulrich, Reference Ulrich, Hesselbein, Goldsmith and Beckhard1997), which identifies key competences for managing effective leadership and superior organisational performance. Research suggests that effective leadership necessitates an integration of multiple competences, such as problem-solving skills, social judgement, and specialised knowledge, which directly influences the quality of decision-making and organisational performance. However, developing managerial competences to support effective leadership behaviours through training must be clearly aligned to managerial positions and behaviours. Consequently, as competencies become capabilities through leadership practice, experience, and effective action, the HtGM programme must be comprehensively evaluated to ensure outputs have the required transformative impact post-completion (Policy Exchange, 2023).

SMEs and growth

SME growth depends upon substantive growth capabilities (Koryak et al., Reference Koryak, Mole, Lockett, Hayton, Ucbasaran and Hodgkinson2015) and growth-oriented actions and processes, such as market penetration, innovation, internationalisation, and new product development (Wright, Roper, Hart & Carter, Reference Wright, Roper, Hart and Carter2015). Limited resources, access to funding, digital transformation, and new frontier technologies are typical challenges for today’s SME leaders and managers. The HtGM training outcomes are designed to improve strategic leadership and management skills, with improved confidence for leading business and an increased awareness of productivity and growth. This suggests that SMEs must be agile, flexible, and innovative (Costin, O’Brien & Hynes, Reference Costin, O’Brien and Hynes2022), demonstrating skills and competences that enables them to operate in demanding environments.

Small business growth is extensively researched by scholars, covering a multitude of topic areas, such as fast growth (Du & Bonner, Reference Du and Bonner2017), financing growth (Owen, Botelho, Hussain & Anwar, Reference Owen, Botelho, Hussain and Anwar2023), growth as a multidimensional process (Salder, Gilman & Ghikas, Reference Salder, Gilman and Ghikas2020), consequences of growth (Freel & Gordon, Reference Freel and Gordon2022), and SME performance support (Pouka & Biwolé, Reference Pouka and Biwolé2024). However, the increasing focus on sustainability, innovation, and technological advancements, as well as business networking (Paterson, Gallota & Baranova, Reference Paterson, Gallota and Baranova2023), including internationalisation and collaborative innovation (Audretsch & Guenther, Reference Audretsch and Guenther2023), emphasises the importance of acquiring new knowledge, skills, and abilities, to meet the demands of leading and managing change in a challenging environment. Furthermore, developing networking capabilities and managing firm performance (Wegner, Foguesatto & Zuliani, Reference Wegner, Foguesatto and Zuliani2023) may be beyond the day-to-day reach of some SME businesses, so training programmes provide a pipeline for networking opportunities and social interaction support.

Advances in technology mean that SMEs must have the capability to be dynamic and flexible, responding quickly to changes in the business environment, resulting in the increase of jobs, the economy and the quality of life (Gegenfurtner, Knogler & Schwab, Reference Gegenfurtner, Knogler and Schwab2020). Training is regarded as an important contributor towards boosting a firm’s human capital capabilities and organisational knowledge (Idris et al., Reference Idris, Saridakis and Johnstone2023) and one of the most important determinants of SME performance, growth, and survivability (Atiase et al., Reference Atiase, Wang and Mahmood2023). In addition, training can be considered ‘as an investment in human capital’ (Tharenou, Saks & Moore, Reference Tharenou, Saks and Moore2007, p.253), where knowledge, skills, and abilities acquired through training support positive outcomes at organisational level, creating competitive advantage for strategic growth (Sahni, Reference Sahni2020). As prior research demonstrates that supporting SME growth through innovation or leadership and management development schemes is effective (Wright et al., Reference Wright, Roper, Hart and Carter2015, p4), the HtGM programme requires empirical research to assess and confirm effectiveness.

The Help to Grow Management Programme

The HtGM provides tailored learning to meet SMEs’ business needs, specifically for a growth action plan (GAP), underpinned by sustainability and inclusivity. This serves as a catalyst for change and addresses a growing conversation how to foster inclusivity and equitable growth (Minzner, Reference Minzner2020). The overall objective for any policy programme is to generate additionality, as defined by Auerswald (Reference Auerswald, Audretsch, Grilo and Thurik2007) where ‘[…] government involvement results in actions being taken that would not have been taken otherwise by private actors in the absence of policy’ (p. 30). As HtGM supports the acquisition of the skills and knowledge required for decision-making (Atiase et al., Reference Atiase, Wang and Mahmood2023), it supports output additionality (Buisseret, Cameron & Georghiou, Reference Buisseret, Cameron and Georghiou1995), evidenced as improvements in the firm’s performance. In additionality terms, changes in personal and professional behaviours can also be attributed to programme participation.

Designed, developed and delivered by experts from UK Higher Education Business Schools, it is a 12-week, formal off-the-job training programme of business specific content, with 1-2-1 business mentoring, small peer group sessions and an alumni network (SBC, Reference Clifton, Huggins, Morgan and Thompson2024). Overall, the modules address a range of topics, for example, strategy, innovation, digital adoption, finance, and operational practice. A diverse range of value-added learning activities, frequently as self-directed learning or as on-the-job application provides access to business knowledge aligned to the strategic growth plan (GAP), for implementing changes to business strategy or operations. The programme is 90% government subsidised, with businesses paying £750 per participant (SBC, Reference Clifton, Huggins, Morgan and Thompson2024). Applicants must work for an SME based in the UK, employ between 5 and 249 employees, be operating for more than one year and a member of the senior leadership team with direct reporting (SBC, Reference Clifton, Huggins, Morgan and Thompson2024). Typically, businesses come from a broad range of industry sectors, where half of all registered businesses have traded for 1–10 years and more than a third between 11 and 30 years (Department for Business & Trade [DBT], 2024).

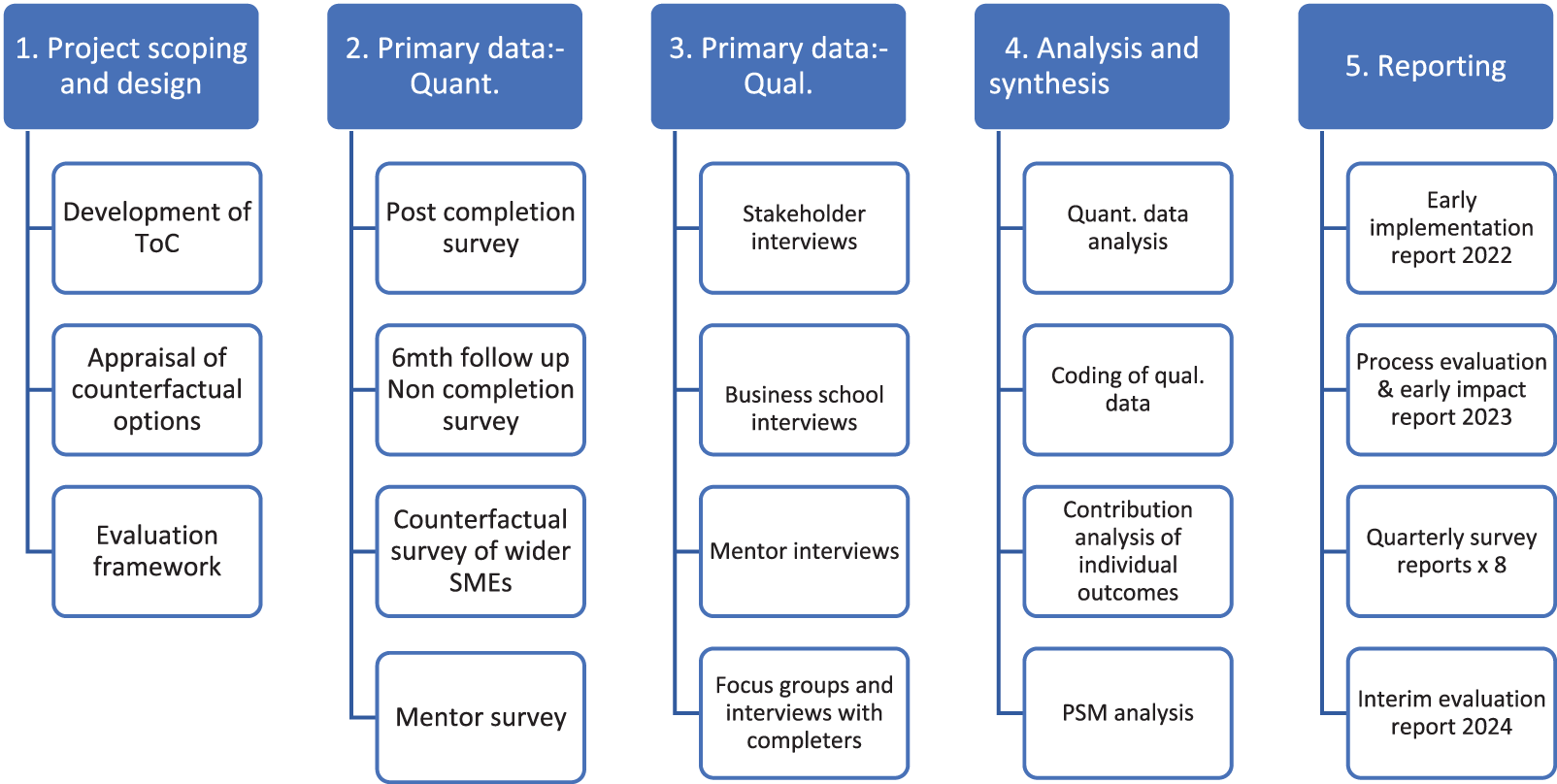

The government’s evaluation reports synthesise primary quantitative and qualitative data, based on an evaluation of their individual and business hypotheses to assess the programme effectiveness (see appendix 1). These reports follow the Theory of Change (ToC) model, developed during the initial scoping and design phase in December 2020–21 (Department for Business & Trade (DBT), 2024a), as shown in Fig. 1.

Figure 1. Overview of interim impact evaluation activities for the HtGM programme

Based on five interrelated pillars – activities, outputs, individual outcomes, business outcomes and longer-term impacts, the data facilitates hypothesis development on casual pathways and mechanisms between pillars at individual and firm level (Department for Business & Trade [DBT], 2024a), reporting outcomes and programme effectiveness for both levels. This study draws on report evidence collected by the DBT in partnership with IES: quarterly progress updates, specifically July–September 2023 Update#6 2024 (Department for Business & Trade [DBT], 2024), update January–March 2025 (Department for Business & Trade [DBT], 2025) and the ‘End of Year 3 Interim Impact Evaluation report’ (Department for Business & Trade [DBT], 2024a).

Method

Research approach

An inductive qualitative design was chosen to explore individual and business outcomes, supporting the relevance of quantitative studies and their applicability to programme implementors and policy makers (Jimenez et al., Reference Jimenez, Waddington, Goel, Prost, Pullin, White and Narain2018). Qualitative designs are particularly useful for identifying experiences associated with a programme’s learning, application and outcomes, providing insights into the complex ‘missing middle’ between the programme implementation and measured outcomes and impact (Garbarino & Holland, Reference Garbarino and Holland2009). They also address the ‘how’ and ‘why’ questions and are useful to understand human experiences in contextual settings, explaining outcomes as a dynamic process, rather than as a static outcome from quantitative surveys.

Sample, data collection, and analysis

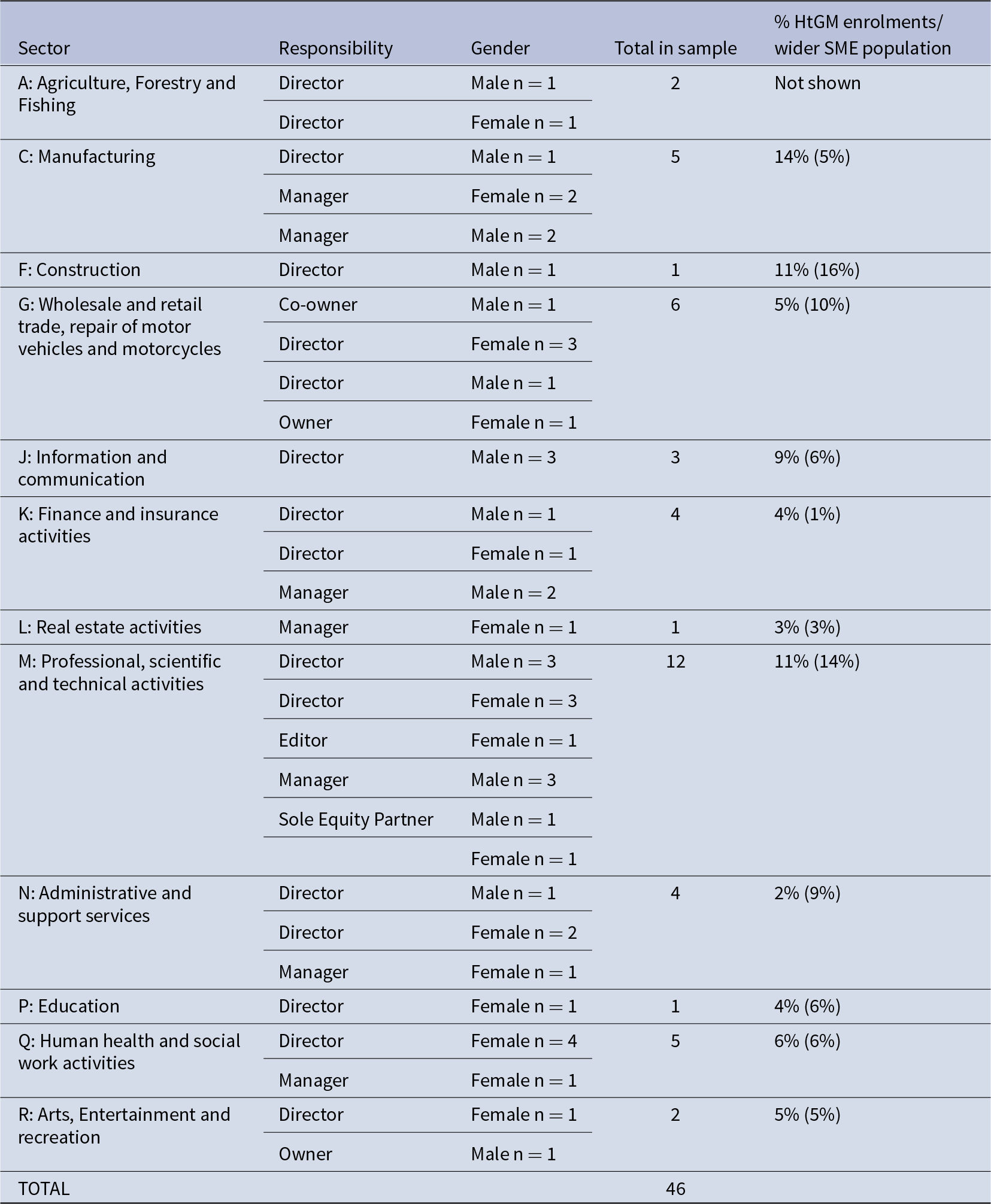

Purposive sampling was applied to meet the eligibility criteria of the programme; participants were an owner, manager or leader of a SME with less than 250 employees and had completed the programme delivered by a business school in the East Midlands (EM) region, which represents 7% of UK SME business population, (Department for Business & Trade [DBT], 2024). Completers were defined as attending at least 9 of 12 modules and were a reporting member of the senior leadership team. Each cohort, comprising of small, local and regional businesses was approached and 46 managers agreed to participate in the study, representing 24% of the total enrolled on the programme and 38% of completions (see Table 1).

Table 1. HtGM programme cohort enrolment details 2021–2024

Source: Author’s own work.

Data were collected during the period 2021–2024, including a short survey of participants’ socio-demographic information (see appendix 2) and their motivation for enrolling (see appendix 3). This provides insight on the participants’ perceived value for enrolling on the course. Typically, HtGM data shows businesses with 1–10 years in operation at 49% enrolment and 11–30 years as 37% enrolment (Department for Business & Trade [DBT], 2024), not dissimilar to this study’s enrolment figures. The Standard Industrial Classification (2007) for self-selected registration to Companies House was compared to HtGM sector registrations of the wider SME population, shown in Table 2. Although sector specific enrolment data from the DBT indicates service and manufacturing as the highest percentage take-up (16% and 14%, respectively) (Department for Business & Trade [DBT], 2024a), this is not represented in this study’s sample. The East Midlands region has a diverse economy with several important sectors, namely advanced manufacturing, transport and logistics, retail and renewable green energy, so this evidence was surprising and not similar to the HtGM enrolment data.

Table 2. Sample characteristics of participants according to standard industrial classification of economic activities 2021–2024 and HtGM enrolment figures

Note: DBT data shows sector enrolments and wider SME population as a %.

Source/s: SIC codes, ONS, (2023), DBT (Department for Business & Trade [DBT], 2024a) and author’s own work.

Recorded interview sessions were held online using MS Teams and lasted between 30 and 45 minutes. Expectations of the HtGM programme hypotheses were explored in depth (see appendix 1). Other questions were asked on the relevance of module content to business application and personal or professional development outcomes.

Thematic analysis (Saldaña, Reference Saldaña2021) generated themes using NVivo 14 software for analysis. The process began with first-order coding after reading and re-reading transcripts, allocating blocks of text or phrases to the first codes, then combining and merging similar perceptions from participants until the content was saturated. Thirty-six codes were assigned labels and descriptors. Next, first order codes were aggregated into second order categories based on emerging themes and patterns, then aggregated into final themes (Saldaña, Reference Saldaña2021) to form a data structure (see Table 3). This process develops a schematic representation of the findings, demonstrating analysis from real data to conceptual abstraction (Saldaña, Reference Saldaña2021).

Table 3. Data structure of first and second order categories with final key themes

Source: Author’s own work.

Three main themes were identified: (1) Leading a business, (2) Developing leadership capabilities, and (3) Creating a knowledge sharing environment, representing similar content to that presented in DBT’s hypotheses proposals (see appendix 1). This was reassuring and to improve analysis and establish consistency with theoretical interpretation, topics noted in the HtGM evaluation reports were cross-checked with the data and themes to ensure consistency.

Results

Developing knowledge and skills for managerial competence

Exploring the first research question, ‘How has the HtGM training programme supported the development of knowledge, skills and confidence for leadership capability’ shows that the programme enhanced participants’ knowledge of strategic management (Panagiotakopoulos, Reference Panagiotakopoulos2020), developed managerial competences and encouraged reflection on current practice. Insights from the DBT focus group reports (Department for Business & Trade [DBT], 2024) also note that the programme provided opportunities to take time away from the day-to-day-operations, providing a focus for strategic thinking and planning. As commented by a manager in this study:

I think one of the first things I thought was probably to take a step back and actually look at why we’re doing that. You know, I think when you’re doing something every day, it just becomes that habit. You don’t really understand actually what? Why are we doing that?

For many participants, the programme advanced understanding on how to lead a business in a competitive environment, noting an urgency to move on from their status quo. This is similar to comments made by programme completers in the DBT study when reviewing their vision/mission statement as a catalyst for change (Department for Business & Trade [DBT], 2024a). As one director in this study observed:

I think we tend to think, oh, things are a little bit stagnant. What can we do now? What can we do to move things on a bit?

For others however, it was about identifying knowledge gaps, such as technology advancements, digital adoption requirements or financial understanding, regarded as essential managerial competencies.. SMEs often lack financial expertise, awareness and confidence in obtaining sources of funding (Wright et al., Reference Wright, Roper, Hart and Carter2015), so this was not unexpected. The most recent DBT quarterly report (Department for Business & Trade [DBT], 2025) shows that 74% of HtGM completers gained confidence in leading and managing their business. Comments made in this study’s interviews by a director and manager confirm this, but confidence was gained in different areas:

[…] at the minute I’m learning the finances of the business, which might sound silly after being in business for this long, but money is not something that is my strong point […] So, as I said, I’ve kind of been winging it. So, I think until I can understand the finances better and be more confident in making decisions of where to put money […]

When you’re in a business, you can’t see the wood for the trees. Sometimes you think you have the answers and you go along and you implement things and you live and learn by that. Some things work, some things don’t. I think every business would say the same, but what this [course] gives you is the confidence. It gives you a structure that you can easily follow.

Developing confidence and soft skills for leadership capability

For programme effectiveness at a business level, the DBT interim report found that 91% of completers reported improved leadership and management of their business (Department for Business & Trade [DBT], 2024a). Although the DBT report cites that SME leaders have significantly greater confidence in their firm’s ability to lead through change and uncertainty when compared to similar SMEs in the wider UK economy, there is no specific survey result that measures this confidence level. It is presented as evidence from in-depth interviews and focus groups as ‘suggests that HtGM leads to improvements in SMEs leaders’ confidence by validating existing ideas, giving them the conviction of implement these ideas and self-efficacy’ (Department for Business & Trade [DBT], 2024a, Chapter 5). As strategic thinking requires individuals to synthesise information and look at the business from alternative perspectives, it is surprising that confidence development and soft skills are not included in the programme evaluation as a specific outcome metric. In this study it was noted that collaboration and conversations with others were useful modalities for developing confidence. As stated by a manager:

[…] and it’s good to talk to your peers because everybody on the course has really, I suppose, give or take the same issues as yourself. And you know the confidence it gives you because you think, well, actually, yeah, yeah, I’m on the right lines here because my other peers are saying the same thing and they think the same as me, because you do find you are in your little bubble as a small business.

In addition, confidence in a leadership role develops from group participation as well as feedback on their role as leaders (Söderhjelm, Larsson, Sandahl, Björklund & Palm, Reference Söderhjelm, Larsson, Sandahl, Björklund and Palm2018), which in turn will enhance manager capability. Both this study’s findings and the DBT’s 6-month survey findings (83% of completers) suggest improved relationships develop between leadership and the wider team as a result of participation in the programme. In addition, business strategy and change requires flexibility and dynamic adaptation (Surya et al., Reference Surya, Menne, Sabhan, Suriani, Bubakar and Idris2021) and leadership capabilities, acquired from informal practice and team contribution. As noted in this study, these were refined and developed in the workplace or evaluated in the peer group sessions through reflection and feedback. Application requires certain technical skills and the ability to perform the task, so these activities facilitated how new knowledge and skills are converted into leadership capability over the duration of the programme and can be reinforced post completion. Comments from the participants provided many examples of individual and business level outcomes, where new competencies and skills were developed as inputs and capabilities as outcomes. As one co-owner stated:

[…] and obviously with the Help to Grow there are lots and lots of ideas to take in and I’m …it’s that sense of yes, focusing on what it's gonna be, you know, most effective but feasible in terms of what we can actually, you know implement […]

The softer skills of leadership, such as communication, interpersonal skills, time management, and life skills were deemed significant in the DBT evaluation report, and required for developing relationships as a source of support (82% feeling better supported for decision making and 72% less isolated in their role as a leader; Department for Business & Trade [DBT], 2024a). In addition, as prior research notes, co-operation networks also provide access to knowledge and innovation resources (Pereira & Franco, Reference Pereira and Franco2022), considered important for sustainability and long-term growth. In particular, this study’s findings stress the importance of developing relationships, holding conversations with others and networking to be significant for developing leadership capabilities, as well as reinforcing learning and knowledge exchange back in the business. As noted by a director:

I might pick up the phone and go, I’ve got this idea and I’m really struggling with it. What do you think? I mean, I’m bouncing it around, so you might get a completely different view because they’re not in it like I am.

Mentoring and the diffusion of knowledge

The diffusion of knowledge is a programme effectiveness business outcome in the interim evaluation report (Department for Business & Trade [DBT], 2024) and the quarterly review (Department for Business & Trade [DBT], 2025). Significantly, 91% programme completers had shared what they had learned or gained from the programme with others in their business (Department for Business & Trade [DBT], 2025). In addition, this is used as a significant outcome and impact measurement; to a great extent, 37% have shared with others and 54% to some extent (Department for Business & Trade [DBT], 2025). Data were collected at the 6-month follow-up survey but this study’s findings suggests that diffusion commences at the onset of the programme, where newly acquired knowledge is shared, either as informal discussion, or formalised through presentations and special interest groups in the business. As noted by Wright et al. (Reference Wright, Roper, Hart and Carter2015), dynamic capabilities are positively related to firm performance and that prior qualitative evidence suggests this is linked to capability development. A study by Mathur (Reference Mathur2025) posits that managers should focus more on capability reinforcement than on resource transformation. As capability is a source for sustainable competitive advantage, the dissemination of knowledge during and after the course helps to embed organisational learning at team/individual level and how to execute the growth plan metrics for improved performance. As explained by a director:

[…] we go through each stage and you know, with whoever it may be. So, whether it’s just the management team or you know, some of the bits like the core values you know it’s well, OK, we’ll get all our staff, get them into three groups and then you can see the overriding things from each group which you know, it’s a good idea, you know if people think that’s your value, then, in every single thing.

Supporting the DBT’s findings across all reviews, the role of the mentor and peer group sessions play an important part in this knowledge exchange, encouraging reflective practice. The report evaluations also note mentoring as highly valued support, with participants using their mentoring relationships to build on the topics taught in the HtGM curriculum, as well as seeking advice on other business issues (Department for Business & Trade [DBT], 2024a). Overall, mentoring motivated participants to review and reflect on their organisation’s key capabilities and competences and how they could implement growth plans. Moreover, this study demonstrates how mentor relationships facilitate valuable knowledge transfer and skill development as a collaborative relationship, allowing knowledge and expertise exchange as a co-construction process (Pouka & Biwolé, Reference Pouka and Biwolé2024), thus enhancing leadership capability and confidence. As commented by a manager, this developed a greater sense self-awareness and of their business:

[…] I had a mentoring session a couple of days ago as well, and I think it’s not until you know, you start talking back over things that you realise probably as well how much you’ve actually taken in, and how much it’s making you think about (business) […]

Increasing awareness of business performance and long-term growth outcomes

The second research question, ‘To what extent has the programme increased awareness of their business’s performance and long-term growth as a result of their participation in the programme’ highlighted that annual turnover, employee numbers or sales targets were common metrics for growth, compared to the programme’s focus on productivity and efficiency metrics for operational effectiveness, and how metrics can be improved relative to the GAP. Similar to the DBT reports, additional insights into improvements, such as cash flow and internal staff processes were mentioned. A few managers noted efficiency improvements, but only one director cited key performance indicators (KPIs) as a metric:

…I’ve been putting together my SMART goals back to the business about how I want to achieve my KPIs, my targets that I’ve been given. But not only how I’m gonna achieve mine, but how I’m gonna support the additional senior team to achieve theirs using my KPIs. Um, but we do have a plan to grow. We want to, it is more of the same that we do now, so it’s more about keeping our current products, which we are good at, and then putting them out to new customers.

A significant outcome of the DBT was comparable with this study’s findings, that is, the proportion of SME leaders who completed the GAP was noted in the evaluation report as lower than expected. In this study, participants found it difficult to complete the GAP on a weekly basis and to keep it moving forward, relative to the module content. The latest DBT progress report also shows that the target of 90% has still never been reached and the most recent quarter (Y4Q4) shows a decrease from 76% to 69% (Department for Business & Trade [DBT], 2025). This study’s data suggests that the weekly tasks (module attendance, workbook, peer group session and reflection) made heavy demands on self-directed study time and that GAP action plans frequently conflicted with pressing demands on return-to-work post study. As succinctly noted by one director:

Well, we haven’t got a written strategy, but it’s OK. Well, that’s quite a broad thing to state, or mission, vision, that we haven’t got any, you know? OK, well, yeah. So, what I’ve done is I’ve sort of, I’ve filled the bits in that I can […]

The DBT’s data for Y4Q4, states that over two-thirds (69%) of all post-completion survey respondents said they had produced a GAP (Department for Business & Trade [DBT], 2025). However, this study’s findings showed that post completion, participants had still not implemented their planned actions, suggesting that although the GAP was completed (as it is part of the programme curriculum), it was not yet applied. As stated by a director:

[…] but this is one of the things that we’re planning to do as a result of the course. (what) we’ve been doing is actually, you know, is looking at establishing more leads […]

This suggests that SME growth was perceived as challenging, especially when dealing with external issues and internal resource constraints. Furthermore, different participants had different growth ambitions, highlighting the heterogenous nature of mixed cohort groups and the complexities of training small business leaders with different experiences and knowledge from different sectors and who were at different positions on the growth curve.

So, it’s a big challenge now, because we are not fighting some small market, we fight with the big companies, with the big brand names, and it’s really tough to do it when your growth is organic. And yes, we invest every cent inside the company – that’s why we have some internal resources, but it’s not enough when you go to global business and compete with global brands.

Comments from this study’s participants do support the programme as a value-added activity overall, having a positive impact on a range of business outcomes, comparable with similar results shown in the DBT report (Department for Business & Trade [DBT], 2024a, 2025). However, follow-up sessions post-completion were proposed, suggesting that the GAP task was more difficult than realised and support sessions are needed to guide implementation:

I think one of the key learning points is that there will (have) be a check in. To have that access, and I’m thinking here […] a month afterwards to go, how are you finding it now? Is this still relevant? Has this supported you with your business, you know, is there anything else we can help you with? Obviously, that helps us as a business.

This infers that the perceived benefits initiated by the programme may drop off overtime, illustrating that although formal training programmes are beneficial with some immediate positive impacts achieved, there is still a need for a long-term, systematic approach to demonstrate improved performance.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to explore how the HtGM programme supports the development of knowledge, skills, and leadership capabilities to implement long-term strategic growth plans, as perceived by participants who have completed the HtGM programme.

Overall, this study’s findings broadly match those of the 2024 and 2025 DBT evaluation reports, supporting their evidence that 91% of programme completers had learned or gained something from their engagement, related to improved leadership and management skills (Department for Business & Trade [DBT], 2024a). Participants from all cohorts in this study identified new knowledge as a range of topics on the factors that drive growth. This aligns with the DBT evidence, where SME leaders reported that their firms have good capabilities and experience across a breadth of areas, improving up to six months after HtGM completion (Department for Business & Trade [DBT], 2025). The study’s aggregate themes from the thematic analysis, leading a business, developing leadership capabilities and creating a knowledge sharing environment also broadly align to the DBT hypotheses, confirming similarity and consistency across studies.

This study’s qualitative analysis provides some deeper insights of the programme’s outcomes. As the HtGM improves confidence, skills and knowledge for key management and leadership practices, HtGM supports the development of leadership capability, providing a foundation for achieving competitive advantage (Kmecova & Gavura, Reference Kmecova and Gavura2024). In this programme, hard skills were observed as overt behaviours (Söderhjelm et al., Reference Söderhjelm, Larsson, Sandahl, Björklund and Palm2018), but interpersonal skills, soft skills and confidence require a participatory delivery approach and were observed during peer group sessions and one-to-one mentoring, confirming the value these activities bring to the programme. Referring to human capital theory (Becker, Reference Becker1993), HtGM does provide the appropriate content and opportunity for developing managers’ knowledge, as the curriculum continues to be comprehensive and relevant, despite a structured delivery. However, predicting competency development for leadership requires blending core managerial skills with essential soft skills, such self-awareness, communication, and emotional intelligence and soft skills were not explicitly taught elements of the curriculum and not mentioned in depth by any of the participants. Nevertheless, soft skills and problem-solving abilities derived from training will enhance managerial effectiveness (Atiase et al., Reference Atiase, Wang and Mahmood2023: Crosbie, Reference Crosbie2005), but for HtGM, these may not always be observable, as peer group sessions and mentoring are mostly online. This indicates a weakness in the HtGM design for soft skill development.

Self-reported measures showed a higher percentage rating 6-months later compared to post-completion survey, for example, understanding the effectiveness of operational processes and how they could be improved increased from 64% to 74% (Department for Business & Trade [DBT], 2025). This observation of the government’s data indicates the benefits of a longitudinal profile to assess effectiveness. As there is evidence to suggest that adult development is a function of experience, the programme facilitates knowledge transfer from training to practice (Autio et al., Reference Autio, Kronlund and Kovalainen2007), albeit over time. The DBT survey data 6-months later may provide a clearer impact of growth metrics as benefits accrue post completion, but there is still a lack of specific performance metrics identified in the DBT reports.

This study’s findings, however, do show that to be effective, a leader must balance the acquisition of new knowledge and self-development with relationship development (Crosbie, Reference Crosbie2005; Wegner et al., Reference Wegner, Foguesatto and Zuliani2023). As proposed by Barbosa (Reference Barbosa2020), developing soft skills and managing relationships promotes managerial capability, as it helps to build a skilled workforce for competitive advantage (Atiase et al., Reference Atiase, Wang and Mahmood2023). This study’s findings indicate that developing communication and interpersonal skills, through networking and programme participation supported capability, alongside the diffusion of knowledge in the organisation through team work. The ability to talk, share and discuss, facilitated a high degree of practice sharing across business (Policy Exchange, 2023), improving self-confidence and self-awareness.

There is plenty of prior evidence to suggest that formal training programmes, including government interventions, are not having the desired impact on SME business performance as expected (Idris et al., Reference Idris, Saridakis and Johnstone2023; Jones et al., Reference Jones, Beynon, Pickernell and Packham2013; Ton et al., Reference Ton, van Rijn and Pamuk2023). In terms of growth and the financial cost of investment in training, results may not provide an immediate positive financial impact for SMEs (Kmecova & Gavura, Reference Kmecova and Gavura2024). Hence, the government cost to support HtGM is an effective hook to capture leaders that might otherwise not engage or lack financial commitment. Furthermore, other research suggests that internal (on-the-job) and external (off-the-job) training does enhance business performance, but in different ways (Idris et al., Reference Idris, Saridakis and Johnstone2023; Jones et al., Reference Jones, Beynon, Pickernell and Packham2013). More general training through government provision may deliver a “doing things differently” or “doing different things” approach’ (Jones et al., Reference Jones, Beynon, Pickernell and Packham2013, p. 74). The HtGM design appears to be a good fit using different modalities and activities for SME provision in the current hybrid climate.

However, despite this observation, there are no clear links between growth and improved performance metrics identified from the DBT reviews or that emerged from this study. Prior research notes limited evidence of a link between the training activity and organisation (Idris et al., Reference Idris, Saridakis and Johnstone2023). Qualitative evidence from this study supports the diffusion of knowledge, as new knowledge shared with others in the organisation, but the impact this has on organisational performance remains unexplored.

Furthermore, despite the fact that over two-thirds (69%) of all post-completion survey respondents in the latest progress report had produced a GAP for their business (Department for Business & Trade [DBT], 2025), only a sales metric was used to show an improvement as a result of programme participation (85% SME leaders HtGM participation resulted in increased sales; Department for Business & Trade [DBT], 2025). This lack of factual, statistical data based on the proposed measures described in the interim report (including cost savings and increased headcount) appears to be a missed opportunity to clarify performance improvements as added value for SMEs. Critics point out that existing research has not focused on the link between training activity and the organisation, but more on time and effort (Idris et al., Reference Idris, Saridakis and Johnstone2023). This study’s findings suggest that managers were more comfortable continuing with their own established metrics than using those proposed for the GAP. Significantly, there are no metrics provided for GAP implementation in the DBT evaluation reports.

In particular, as discussed in the Interim Impact report findings (Department for Business & Trade [DBT], 2024a), engagement with the GAP was lower than expected and this study’s findings highlight similar challenges as noted in the report. Growth was viewed by managers as future focussed, and a lack of strategic planning for future growth was observed in the participants’ approach to completing the GAP. However, the relationship between mentoring and implementation of a growth plan appears significant, as noted by Crehan et al. (Reference Crehan, Duane and Kelliher2025). Thus, additional mentoring post completion would ensure GAP implementation was ongoing.

Satisfaction of the mentoring element of the programme was high, supporting the government’s positive responses (Department for Business & Trade [DBT], 2024). Significantly, this study’s findings showed that the delivery structure was well received and the module topics were applicable to their business and when matched, managed and facilitated knowledge and expertise exchange as a co-construction process (Pouka & Biwolé, Reference Pouka and Biwolé2024; Crehan et al., Reference Crehan, Duane and Kelliher2025). This and peer group discussion suggests that the participants’ comments on their self-confidence development are similar to the survey responses for feeling ‘less isolated’ (Department for Business & Trade [DBT], 2024). Importantly, a key study outcome showed that SME leaders became more strategically confident in leading and managing their business after completing the programme, in some cases, taking on a different or more responsible role. Confidence development has been shown to stem from group membership, workshop activities and peer group sessions (Söderhjelm et al., Reference Söderhjelm, Larsson, Sandahl, Björklund and Palm2018; Crehen et al., Reference Crehan, Duane and Kelliher2025). This study’s qualitative evidence also showed that mentoring encouraged review and reflection on self and the organisation, as well as support and guidance for growth plans, similar to the DBT report (Department for Business & Trade [DBT], 2024a) outcomes.

An important outcome of this study’s qualitative analysis highlighted the use of educational training for diffusion of knowledge. This finding is important for economic development, as it improves business knowledge and understanding, identification of future opportunities, and facilitates effective resources management (Koryak et al., Reference Koryak, Mole, Lockett, Hayton, Ucbasaran and Hodgkinson2015). It also highlights the benefits of intervention and support for organisational development. Thus, upskilling leaders with new knowledge influences their ability to access resources and create dynamic capabilities. This allows exploitation and growth (Koryak et al., Reference Koryak, Mole, Lockett, Hayton, Ucbasaran and Hodgkinson2015) and how new resources can be used effectively to develop a skilled workforce for innovation and competitiveness (Atiase et al., Reference Atiase, Wang and Mahmood2023; Barbosa, Reference Barbosa2020). The Interim Impact report (Department for Business & Trade [DBT], 2024a) noted that 90% of SME leaders had shared what they had learned in the short term, similar to this study’s findings. Notably, a key outcome of this study was how the value of peer group sessions and networking with others in business improved transferable and leadership skills (Atiase et al., Reference Atiase, Wang and Mahmood2023), encouraging cross-collaboration and sharing insights with other employees and stakeholders.

Conclusions and recommendations

This study’s findings demonstrate the programme’s benefits for SMEs and broadly support the DBT's quantitative survey data, offering evidence that improving leadership skills and competences positively impact on upskilling and planning SMEs strategic growth. Results also provide greater detail around the complexity and interrelatedness of the content and their application as perceived by the participants. It is crucial that empirical research builds confidence in this programme investment, in order to continue to influence the actions of business support programmes and policy makers. Key outcomes highlight the importance of self-confidence for facilitating learning and implementation, networking and mentoring for disseminating knowledge, and structuring growth plans and opportunities for cross collaboration with others for knowledge exchange. However, further understanding on how business metrics are used by SMEs for growth would aid the transformative process. In addition, some follow-up options would ensure that implementation of these and future growth plans are not side-lined post programme completion.

From a policy perspective, The HtGM programme has attracted a diverse range of SME leaders from the wider business population. Going forward, it is recommended that the government continues to offer this programme for SMEs, ensuring a long-term commitment for small business support. In addition, a follow-up course for implementing and monitoring the GAP is recommended for post HtGM completion, providing GAP performance metrics that demonstrate the longer-term effectiveness of the programme. GAP evidence as performance metrics will provide policy makers with evidence and as a consequence, will improve their understanding of the heterogeneous nature of SME business growth, thus continuing to meet SMEs’ specific needs in an appropriate and accessible manner.

From a training perspective, this programme is designed to develop managerial competences and leadership capabilities of SMEs. To build on the existing programme content and delivery, this study recommends that first, curriculum improvements should include soft skill development for leadership practice and second, as the mentoring support package enhances reflective practice and supports self-confidence, it must remain an integral part of the programme, Finally, further support for business leaders post-programme completion would ensure longevity of implementation. The design and delivery of the programme is a critical pipeline for SME leadership development and improved productivity. Investment in these recommendations supports the DBT’s aims and objectives for individual and business level training outcomes that are conducive to improving SME growth.

Contributions, limitations, and future research

This study makes three contributions: first, the diffusion of knowledge facilitates the adoption of external knowledge and how this can be integrated to support a learning organisation, enabling future growth for a knowledge-based economy. Thus, HtGM reinforces the importance of developing SME business knowledge through cross-collaboration and networks for improved leadership and workforce engagement, typically needed for determining competitive potential and added value for customers. Second, from a theoretical perspective, HtGM enhances and develops the skills and capabilities required for small business strategic leadership development. Typically, competency frameworks are common to management training research. Leadership capability theory offers an alternative framework which arguably is more aligned to the future of work in innovative and technological transformative SME settings, requiring skilled cognitive and non-cognitive abilities for employee engagement in hybrid settings. Third, this study provides original and empirical evidence on how practice-led research in the context of HtGM provides a greater understanding of programme value. It also demonstrates how self-reported perceptions can be used to provide a deeper understanding of the effectiveness of a business training programme, and for triangulating survey with interview data responses for improving validity.

However, there are some limitations to this study. Reliance is based on a single case and self-reported outcomes, so should be interpreted with caution, as results are likely to be subject to recall bias, where memories of past events and perceptions may be inaccurate or incomplete. This threatens study validity, so interviews were kept short to minimise this. Triangulation with the DBT survey data, combining self-report interview data with the survey data helps to verify the accuracy of recalled information and strengthens the overall credibility and validity of research findings. Furthermore, including SME sector and structural specific indicators would improve the relevance of the data and highlight key differences between sectors.

Finally, future work can extend findings using cross-case comparisons, providing a more holistic understanding of the programme’s long-term value for meeting individual and business level outcomes. This relationship can be examined using qualitative findings from other business schools to demonstrate the effectiveness of the programmes for developing leadership competency and capability. Longitudinal studies should also be employed to examine GAP performance, providing evidence of performance improvements and metrics over a period of time, particularly post GAP implementation.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to express her gratitude to all participants for their time, engagement, and contribution towards the research study.

Competing interests

The author is employed by De Montfort University and has delivered some of the module content of the Help to Grow Management Programme for the university.

Appendix 1. Impact evaluation approach: hypotheses for individual and business outcomes

Source: Ipsos & Department for Business & Trade (DBT) (2024a).

Appendix 2. Additional socio-demographic information from MS Teams survey

Appendix 3. Survey question responses for ‘Please describe your motivation for choosing to study on the H2GM programme’

Source: Author’s own work.

Marian Evans is a Senior Lecturer in Entrepreneurship, Enterprise, and Executive Education at Leicester Castle Business School, De Montfort University. Her main interest is related to entrepreneurship, innovation, and small business growth, developed from her own practitioner experience and a passion for undertaking research that is meaningful for practice. Marian also has published research on higher degree apprenticeship work-based learning, in particular, senior leadership and the tripartite relationship, for example, Education + Training, Higher Education, Skills and Work-Based Learning, and Team Performance Management.