1 INTRODUCTION

Consider the first-order autoregressive process

where we condition on the initial value

![]() $x_{0}=0$

,

$x_{0}=0$

,

![]() $\{\varepsilon _{t}\}$

is a sequence of independent N

$\{\varepsilon _{t}\}$

is a sequence of independent N

![]() $(0,\sigma ^{2})$

, and the parameters

$(0,\sigma ^{2})$

, and the parameters

![]() $\left ( \alpha ,\sigma ^{2}\right ) $

lie unrestrictedly in

$\left ( \alpha ,\sigma ^{2}\right ) $

lie unrestrictedly in

![]() $\mathbb {R}\times \mathbb {R}_{+}$

. A basis for the minimal sufficient statistic is

$\mathbb {R}\times \mathbb {R}_{+}$

. A basis for the minimal sufficient statistic is

where

![]() $z_{1}^{2}\leq z_{2}z_{3}$

. The exact density of commonly used statistics for this model can be obtained once the exact joint density of

$z_{1}^{2}\leq z_{2}z_{3}$

. The exact density of commonly used statistics for this model can be obtained once the exact joint density of

![]() $ {\boldsymbol {z}}$

is determined, and this is derived in the article. These density functions are valid for general

$ {\boldsymbol {z}}$

is determined, and this is derived in the article. These density functions are valid for general

![]() $\alpha \in \mathbb {R}$

and

$\alpha \in \mathbb {R}$

and

![]() $T>3$

, not just

$T>3$

, not just

![]() $ \left \vert \alpha \right \vert =1$

and

$ \left \vert \alpha \right \vert =1$

and

![]() $T=\infty $

. Even for the latter (limiting) case, there are still gaps in the literature where the density does not have a convergent expression for some positive values of

$T=\infty $

. Even for the latter (limiting) case, there are still gaps in the literature where the density does not have a convergent expression for some positive values of

![]() $ z_{1}/z_{2}$

and for all positive values of the Studentized t-ratio [see page 1068 of Abadir (Reference Abadir1993b) for the former, and Abadir (Reference Abadir1995) and Dietrich (Reference Dietrich2001) for the latter].

$ z_{1}/z_{2}$

and for all positive values of the Studentized t-ratio [see page 1068 of Abadir (Reference Abadir1993b) for the former, and Abadir (Reference Abadir1995) and Dietrich (Reference Dietrich2001) for the latter].

Any representation of the sufficient statistic can be written as an invertible function of the basis

![]() ${\boldsymbol {z}}$

, and one that will be used in the derivations is

${\boldsymbol {z}}$

, and one that will be used in the derivations is

![]() $\widetilde {{\boldsymbol {z}}}:=\left ( \tilde {z}_{1},\tilde {z}_{2},\tilde {z} _{3}\right ) ^{\prime }$

with

$\widetilde {{\boldsymbol {z}}}:=\left ( \tilde {z}_{1},\tilde {z}_{2},\tilde {z} _{3}\right ) ^{\prime }$

with

$$ \begin{align*} \tilde{z}_{1}& :=z_{1}+\alpha z_{2}=\sum\nolimits_{t=1}^{T}x_{t-1}\left( \varepsilon _{t}+\alpha x_{t-1}\right) =\sum\nolimits_{t=1}^{T}x_{t-1}x_{t} \\ \tilde{z}_{2}& :=z_{2}=\sum\nolimits_{t=1}^{T}x_{t-1}^{2} \\ \tilde{z}_{3}& :=\frac{1}{2}z_{3}+\alpha z_{1}-\frac{1-\alpha ^{2}}{2}z_{2}= \frac{1}{2}\left( \sum\nolimits_{t=1}^{T}\left( \alpha x_{t-1}+\varepsilon _{t}\right) ^{2}-\sum\nolimits_{t=1}^{T}x_{t-1}^{2}\right)\\& \phantom{:}=\frac{1}{2} \left( x_{T}^{2}-x_{0}^{2}\right) =\frac{1}{2}x_{T}^{2}, \end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*} \tilde{z}_{1}& :=z_{1}+\alpha z_{2}=\sum\nolimits_{t=1}^{T}x_{t-1}\left( \varepsilon _{t}+\alpha x_{t-1}\right) =\sum\nolimits_{t=1}^{T}x_{t-1}x_{t} \\ \tilde{z}_{2}& :=z_{2}=\sum\nolimits_{t=1}^{T}x_{t-1}^{2} \\ \tilde{z}_{3}& :=\frac{1}{2}z_{3}+\alpha z_{1}-\frac{1-\alpha ^{2}}{2}z_{2}= \frac{1}{2}\left( \sum\nolimits_{t=1}^{T}\left( \alpha x_{t-1}+\varepsilon _{t}\right) ^{2}-\sum\nolimits_{t=1}^{T}x_{t-1}^{2}\right)\\& \phantom{:}=\frac{1}{2} \left( x_{T}^{2}-x_{0}^{2}\right) =\frac{1}{2}x_{T}^{2}, \end{align*} $$

where

![]() $\tilde {z}_{1}$

is an odd function of

$\tilde {z}_{1}$

is an odd function of

![]() $\alpha $

, and

$\alpha $

, and

![]() $\tilde {z}_{2}, \tilde {z}_{3}$

are positive almost surely. The components of

$\tilde {z}_{2}, \tilde {z}_{3}$

are positive almost surely. The components of

![]() $\widetilde {{\boldsymbol {z}}} $

are observable. Also,

$\widetilde {{\boldsymbol {z}}} $

are observable. Also,

$$ \begin{align} \frac{\tilde{z}_{1}^{2}}{\tilde{z}_{2}\left( \tilde{z}_{2}+2\tilde{z} _{3}\right) }=\frac{\left( \sum_{t=1}^{T}x_{t-1}x_{t}\right) ^{2}}{ \sum_{t=1}^{T}x_{t-1}^{2}\sum_{t=1}^{T}x_{t}^{2}}\in \left( 0,1\right) \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} \frac{\tilde{z}_{1}^{2}}{\tilde{z}_{2}\left( \tilde{z}_{2}+2\tilde{z} _{3}\right) }=\frac{\left( \sum_{t=1}^{T}x_{t-1}x_{t}\right) ^{2}}{ \sum_{t=1}^{T}x_{t-1}^{2}\sum_{t=1}^{T}x_{t}^{2}}\in \left( 0,1\right) \end{align} $$

almost surely.

Here, the density function of

![]() ${\boldsymbol {z}}$

is given in a convergent and numerically efficient series. The terms of the series are all determined explicitly, and require no further solution of any recurrence relation. Our formula is easy to calculate numerically; for example, it took less than a second on a typical laptop to calculate the density at any point in the parameter space for any

${\boldsymbol {z}}$

is given in a convergent and numerically efficient series. The terms of the series are all determined explicitly, and require no further solution of any recurrence relation. Our formula is easy to calculate numerically; for example, it took less than a second on a typical laptop to calculate the density at any point in the parameter space for any

![]() ${\boldsymbol {z}}$

or

${\boldsymbol {z}}$

or

![]() $\widetilde {{\boldsymbol {z}}}$

, and just a few seconds to calculate the whole density. Moreover, the formula for the density of

$\widetilde {{\boldsymbol {z}}}$

, and just a few seconds to calculate the whole density. Moreover, the formula for the density of

![]() $ {\boldsymbol {z}} $

can be used to derive the marginal density of general functions of

$ {\boldsymbol {z}} $

can be used to derive the marginal density of general functions of

![]() ${\boldsymbol {z}}$

, and we apply this to obtain the density of the autocorrelation coefficient and its Studentized t-ratio. Furthermore, unlike in the limiting case in Abadir (Reference Abadir1995), it would not have been possible to find a simple integral to compute numerically for the density of

${\boldsymbol {z}}$

, and we apply this to obtain the density of the autocorrelation coefficient and its Studentized t-ratio. Furthermore, unlike in the limiting case in Abadir (Reference Abadir1995), it would not have been possible to find a simple integral to compute numerically for the density of

![]() $\mathrm {t}>0$

for

$\mathrm {t}>0$

for

![]() $T<\infty $

, as this integral would be divergent: the explicit solution of this integral is achieved by analytic continuation (from complex analysis) thus resolving this convergence problem and giving an explicit answer in addition.

$T<\infty $

, as this integral would be divergent: the explicit solution of this integral is achieved by analytic continuation (from complex analysis) thus resolving this convergence problem and giving an explicit answer in addition.

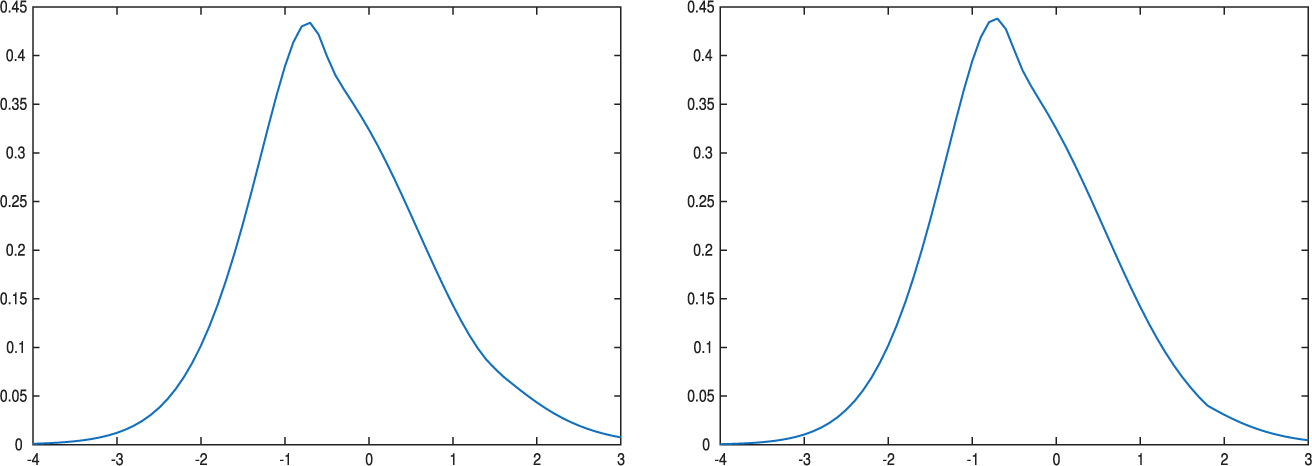

This article also demonstrates how to resolve a general problem in statistical distribution theory, well beyond the specific case of autoregressive models. In multidimensional inversions of characteristic functions, there can be a subspace of the domain of integration where the integrand takes a limiting functional form that is different as we approach this subspace. The resulting inversion produces erroneous features, such as visible spikes when the formula is calculated (see Figure 3 below for an illustration). This problem applies to the theoretical derivation, as well as direct numerical integration in the inversion formula, and is not an artifact of numerical computations. This problem was identified but unsolved in Abadir and Rockinger (Reference Abadir and Rockinger1997). The solution here uses analytic continuation to reformulate the multiple integrals of the Fourier inversion and subsequent marginalization of the joint density. Because it is difficult to get an overview of the problem in advance, a discussion of the methodology that is used to resolve such a problem is left until the problem is treated and solved in the current setup (see the end of Section 4 for this general discussion).

The derivations used in this article require knowledge of some complex analysis (mainly for Section 2) and elements of the theory of special functions; e.g., see Spiegel (Reference Spiegel1981) and Erdélyi (Reference Erdélyi1953, Reference Erdélyi1955) [or Abadir (Reference Abadir1999) for a simple introduction], respectively. The literature on unit roots is vast, but less so when it comes to exact explicit density functions and the highly non-normal shape that they take for (1), even in the stationary case

![]() $\left \vert \alpha \right \vert <1$

when

$\left \vert \alpha \right \vert <1$

when

![]() $T<\infty $

. Some key papers are White (Reference White1958, Reference White1959), Anderson (Reference Anderson1959), Dickey and Fuller (Reference Dickey and Fuller1979, Reference Dickey and Fuller1981), Evans and Savin (Reference Evans and Savin1981), Chan and Wei (Reference Chan and Wei1987), Phillips (Reference Phillips1987a, Reference Phillips1987b), Perron (Reference Perron1991), and Larsson (Reference Larsson1995). The plan of the article is as follows. Section 2 derives the joint density of

$T<\infty $

. Some key papers are White (Reference White1958, Reference White1959), Anderson (Reference Anderson1959), Dickey and Fuller (Reference Dickey and Fuller1979, Reference Dickey and Fuller1981), Evans and Savin (Reference Evans and Savin1981), Chan and Wei (Reference Chan and Wei1987), Phillips (Reference Phillips1987a, Reference Phillips1987b), Perron (Reference Perron1991), and Larsson (Reference Larsson1995). The plan of the article is as follows. Section 2 derives the joint density of

![]() ${\boldsymbol {z}}$

. This is then applied to obtaining the finite-sample density of the least-squares estimator

${\boldsymbol {z}}$

. This is then applied to obtaining the finite-sample density of the least-squares estimator

![]() $\hat {\alpha }$

of

$\hat {\alpha }$

of

![]() $ \alpha $

in Section 3 for any

$ \alpha $

in Section 3 for any

![]() $\alpha ,T$

. Another application of the joint density is worked out in Section 4, where we derive the density of the Studentized t-ratio (including the case of

$\alpha ,T$

. Another application of the joint density is worked out in Section 4, where we derive the density of the Studentized t-ratio (including the case of

![]() $\mathrm {t}>0$

) for testing

$\mathrm {t}>0$

) for testing

![]() $\alpha =1$

. Section 5 contains the derivations for these two applications. The final section concludes. In addition, a sample MATLAB code to calculate quantiles and p-values for

$\alpha =1$

. Section 5 contains the derivations for these two applications. The final section concludes. In addition, a sample MATLAB code to calculate quantiles and p-values for

![]() $\hat { \alpha }$

is available in the Supplementary Material, to show how quickly and accurately c.d.f.s can be calculated for p-values and quantiles, through the exact finite-sample formulas derived here. In addition to the efficient numerical features, analytical features of the densities are now possible and give insights into the behavior of

$\hat { \alpha }$

is available in the Supplementary Material, to show how quickly and accurately c.d.f.s can be calculated for p-values and quantiles, through the exact finite-sample formulas derived here. In addition to the efficient numerical features, analytical features of the densities are now possible and give insights into the behavior of

![]() $\hat {\alpha }$

and tests based on it in finite samples.

$\hat {\alpha }$

and tests based on it in finite samples.

We write the change of a variable of integration which maps

![]() $u\mapsto v:=h\left ( u\right ) $

in the inverse-mapping form

$u\mapsto v:=h\left ( u\right ) $

in the inverse-mapping form

![]() $u\leftrightarrow h^{-1}\left ( v\right ) $

, whereby u is replaced by

$u\leftrightarrow h^{-1}\left ( v\right ) $

, whereby u is replaced by

![]() $h^{-1}\left ( v\right ) $

in the integrand. We use

$h^{-1}\left ( v\right ) $

in the integrand. We use

![]() $\Gamma \left ( \nu \right ) $

to denote the gamma (generalized factorial) function,

$\Gamma \left ( \nu \right ) $

to denote the gamma (generalized factorial) function,

![]() $\mathrm {B}\left ( \nu _{1},\nu _{2}\right ) :=\Gamma \left ( \nu _{1}\right ) \Gamma \left ( \nu _{2}\right ) /\Gamma \left ( \nu _{1}+\nu _{2}\right ) $

the beta function,

$\mathrm {B}\left ( \nu _{1},\nu _{2}\right ) :=\Gamma \left ( \nu _{1}\right ) \Gamma \left ( \nu _{2}\right ) /\Gamma \left ( \nu _{1}+\nu _{2}\right ) $

the beta function,

![]() $\left ( \nu \right ) _{n}:=\Gamma \left ( \nu +n\right ) /\Gamma \left ( \nu \right ) =\prod \nolimits _{i=0}^{n-1}\left ( \nu +i\right ) $

the Pochhammer (forward permutation) symbol, and

$\left ( \nu \right ) _{n}:=\Gamma \left ( \nu +n\right ) /\Gamma \left ( \nu \right ) =\prod \nolimits _{i=0}^{n-1}\left ( \nu +i\right ) $

the Pochhammer (forward permutation) symbol, and

![]() $_{p}F_{q}$

the generalized hypergeometric series whose special case

$_{p}F_{q}$

the generalized hypergeometric series whose special case

![]() $_{2}F_{1}$

(which was the first to be analyzed before its generalization) is due to Gauss. The generalized

$_{2}F_{1}$

(which was the first to be analyzed before its generalization) is due to Gauss. The generalized

![]() $_{p}F_{q}$

includes exponential, binomial, trigonometric, and most functions (and their inverses) that we use regularly. Three results that will be used freely are Legendre’s duplication formula

$_{p}F_{q}$

includes exponential, binomial, trigonometric, and most functions (and their inverses) that we use regularly. Three results that will be used freely are Legendre’s duplication formula

$$ \begin{align} \Gamma \left( 2\nu \right) = \frac{2^{2\nu -1}}{\sqrt{\pi }} \Gamma \left( \nu \right) \Gamma \left( \nu +\frac{1}{2}\right) , \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} \Gamma \left( 2\nu \right) = \frac{2^{2\nu -1}}{\sqrt{\pi }} \Gamma \left( \nu \right) \Gamma \left( \nu +\frac{1}{2}\right) , \end{align} $$

Euler’s reflection formula

and Euler’s transformations of the Gauss

![]() $_{2}F_{1}$

as

$_{2}F_{1}$

as

$$ \begin{align} _{2}F_{1}\left( a,b;c;w\right) &\equiv \left( 1-w\right) ^{c-a-b}\,_{2}F_{1}\left( c-a,c-b;c;w\right)\nonumber\\& \equiv \left( 1-w\right) ^{-a}\,_{2}F_{1}\left( a,c-b;c;\frac{w}{w-1}\right) , \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} _{2}F_{1}\left( a,b;c;w\right) &\equiv \left( 1-w\right) ^{c-a-b}\,_{2}F_{1}\left( c-a,c-b;c;w\right)\nonumber\\& \equiv \left( 1-w\right) ^{-a}\,_{2}F_{1}\left( a,c-b;c;\frac{w}{w-1}\right) , \end{align} $$

where the second transformation is also known as Pfaff’s transformation. The integral representations of

![]() $_{2}F_{1}$

are standard and used freely here. The formulas for analytic continuation of

$_{2}F_{1}$

are standard and used freely here. The formulas for analytic continuation of

![]() $_{2}F_{1}$

are available on pages 108–109 of volume 1 of Erdélyi (Reference Erdélyi1953) and page 454 of volume 3 of Prudnikov, Brychkov, and Marichev (Reference Prudnikov, Brychkov and Marichev1986); see also the addition theorems in Section 6.7 of volume 3 of Prudnikov et al. (Reference Prudnikov, Brychkov and Marichev1986).

$_{2}F_{1}$

are available on pages 108–109 of volume 1 of Erdélyi (Reference Erdélyi1953) and page 454 of volume 3 of Prudnikov, Brychkov, and Marichev (Reference Prudnikov, Brychkov and Marichev1986); see also the addition theorems in Section 6.7 of volume 3 of Prudnikov et al. (Reference Prudnikov, Brychkov and Marichev1986).

2 THE JOINT DENSITY OF

${\boldsymbol {{z}}}$

${\boldsymbol {{z}}}$

Let

![]() $\varphi \left ( v_{1},v_{2},v_{3}\right ) :=\operatorname {E}\left [ \exp \left ( v_{1}z_{1}+v_{2}z_{2}+v_{3}z_{3}\right ) \right ] $

be the moment generating function of

$\varphi \left ( v_{1},v_{2},v_{3}\right ) :=\operatorname {E}\left [ \exp \left ( v_{1}z_{1}+v_{2}z_{2}+v_{3}z_{3}\right ) \right ] $

be the moment generating function of

![]() ${\boldsymbol {z}}$

. By Fourier inversion, the joint density is

${\boldsymbol {z}}$

. By Fourier inversion, the joint density is

$$ \begin{align*} f_{{\boldsymbol{z}}}\left( {\boldsymbol{w}}\right) &=\frac{1}{\left( 2\pi \right) ^{3}}\int_{\mathbb{R}^{3}} \mathrm{e}^{-\mathrm{i} v_{1}w_{1}-\mathrm{i} v_{2}w_{2}-\mathrm{i} v_{3}w_{3}}\varphi \left( \mathrm{i} v_{1}, \mathrm{i} v_{2},\mathrm{i} v_{3}\right) \,\mathrm{d}\left( v_{1},v_{2},v_{3}\right) \\ &=\frac{1}{\left( 2\pi \mathrm{i}\right) ^{3}}\int_{\left( \mathrm{i}\mathbb{R}\right) ^{3}}\mathrm{e} ^{v_{1}w_{1}+v_{2}w_{2}+v_{3}w_{3}}\varphi \left( -v_{1},-v_{2},-v_{3}\right) \,\mathrm{d}\left( v_{1},v_{2},v_{3}\right) , \end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*} f_{{\boldsymbol{z}}}\left( {\boldsymbol{w}}\right) &=\frac{1}{\left( 2\pi \right) ^{3}}\int_{\mathbb{R}^{3}} \mathrm{e}^{-\mathrm{i} v_{1}w_{1}-\mathrm{i} v_{2}w_{2}-\mathrm{i} v_{3}w_{3}}\varphi \left( \mathrm{i} v_{1}, \mathrm{i} v_{2},\mathrm{i} v_{3}\right) \,\mathrm{d}\left( v_{1},v_{2},v_{3}\right) \\ &=\frac{1}{\left( 2\pi \mathrm{i}\right) ^{3}}\int_{\left( \mathrm{i}\mathbb{R}\right) ^{3}}\mathrm{e} ^{v_{1}w_{1}+v_{2}w_{2}+v_{3}w_{3}}\varphi \left( -v_{1},-v_{2},-v_{3}\right) \,\mathrm{d}\left( v_{1},v_{2},v_{3}\right) , \end{align*} $$

where

![]() ${\boldsymbol {w}}$

is the realization (or density’s evaluation point) of

${\boldsymbol {w}}$

is the realization (or density’s evaluation point) of

![]() ${\boldsymbol {z}}$

, and similarly for

${\boldsymbol {z}}$

, and similarly for

![]() $\widetilde {{\boldsymbol {w}}}$

and

$\widetilde {{\boldsymbol {w}}}$

and

![]() $\widetilde {{\boldsymbol {z}}}$

later on,

$\widetilde {{\boldsymbol {z}}}$

later on,

![]() $\mathrm {d} (v_{1},v_{2},v_{3})$

is the product of the differentials, and

$\mathrm {d} (v_{1},v_{2},v_{3})$

is the product of the differentials, and

![]() $\mathrm {i}$

is the imaginary unit (principal value of

$\mathrm {i}$

is the imaginary unit (principal value of

![]() $\sqrt {-1}$

). Without loss of generality, to simplify the exposition, we will set

$\sqrt {-1}$

). Without loss of generality, to simplify the exposition, we will set

![]() $\sigma =1$

; the variates can be normalized by

$\sigma =1$

; the variates can be normalized by

![]() $\sigma $

otherwise. This was seen in Abadir and Larsson (Reference Abadir and Larsson1996), whose Theorem 2.3 can be specialized to give

$\sigma $

otherwise. This was seen in Abadir and Larsson (Reference Abadir and Larsson1996), whose Theorem 2.3 can be specialized to give

$$ \begin{align*} &\varphi \left( -v_{1},-v_{2},-v_{3}\right)\\&\quad =\sqrt{c}\left( \left( \frac{c-d}{ 2}+v_{3}\right) \left( 1+d+c\right) ^{T}+\left( \frac{c+d}{2}-v_{3}\right) \left( 1+d-c\right) ^{T}\right) ^{-\frac{1}{2}}, \end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*} &\varphi \left( -v_{1},-v_{2},-v_{3}\right)\\&\quad =\sqrt{c}\left( \left( \frac{c-d}{ 2}+v_{3}\right) \left( 1+d+c\right) ^{T}+\left( \frac{c+d}{2}-v_{3}\right) \left( 1+d-c\right) ^{T}\right) ^{-\frac{1}{2}}, \end{align*} $$

where

$$ \begin{align} \beta _{\pm }& :=\frac{1\pm \alpha ^{2}}{2},\quad \quad \left( \beta \equiv \beta _{+}\in \lbrack \tfrac{1}{2},\infty ),\ \beta _{-}\in (-\infty ,\tfrac{ 1}{2}]\right) , \notag \\ d& :=v_{2}+2\beta v_{3}-\alpha v_{1}-\beta _{-}, \notag \\ c& :=\sqrt{\left( d+1\right) ^{2}-\left( v_{1}-2\alpha v_{3}-\alpha \right) ^{2}}; \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} \beta _{\pm }& :=\frac{1\pm \alpha ^{2}}{2},\quad \quad \left( \beta \equiv \beta _{+}\in \lbrack \tfrac{1}{2},\infty ),\ \beta _{-}\in (-\infty ,\tfrac{ 1}{2}]\right) , \notag \\ d& :=v_{2}+2\beta v_{3}-\alpha v_{1}-\beta _{-}, \notag \\ c& :=\sqrt{\left( d+1\right) ^{2}-\left( v_{1}-2\alpha v_{3}-\alpha \right) ^{2}}; \end{align} $$

see White (Reference White1958) for the original idea, where the moment generating function of only the first two components of

![]() ${\boldsymbol {z}}$

are worked out (subject to a minor typo), as normalizing the third component by T gives the asymptotically nonrandom limit of

${\boldsymbol {z}}$

are worked out (subject to a minor typo), as normalizing the third component by T gives the asymptotically nonrandom limit of

![]() $\sigma ^{2}$

. Here, we need to consider all three components of the sufficient statistic for finite samples, e.g., for the case of the Studentized t-ratio.

$\sigma ^{2}$

. Here, we need to consider all three components of the sufficient statistic for finite samples, e.g., for the case of the Studentized t-ratio.

Consider the integrand, and in particular, the variables

![]() $c,d,v_{3}-d/2$

. To make the integral tractable, first, we transform

$c,d,v_{3}-d/2$

. To make the integral tractable, first, we transform

![]() $\left ( v_{1}-2\alpha v_{3}-\alpha \right ) ^{2}$

into a function depending only on the variable of integration

$\left ( v_{1}-2\alpha v_{3}-\alpha \right ) ^{2}$

into a function depending only on the variable of integration

![]() $v_{1}$

, then the resulting new d into a function of

$v_{1}$

, then the resulting new d into a function of

![]() $v_{2}$

only. This is achieved by the successive transformations replacing (inverse-mapping)

$v_{2}$

only. This is achieved by the successive transformations replacing (inverse-mapping)

![]() $v_{1}\leftrightarrow v_{1}+2\alpha v_{3}$

, then

$v_{1}\leftrightarrow v_{1}+2\alpha v_{3}$

, then

![]() $ v_{2}\leftrightarrow v_{2}+\alpha v_{1}-2v_{3}\beta _{-}$

[where

$ v_{2}\leftrightarrow v_{2}+\alpha v_{1}-2v_{3}\beta _{-}$

[where

![]() $\beta _{-}=\beta -\alpha ^{2}$

from its definition in (6)], and finally

$\beta _{-}=\beta -\alpha ^{2}$

from its definition in (6)], and finally

![]() $ v_{3}\leftrightarrow v_{3}+v_{2}/2$

. This gives

$ v_{3}\leftrightarrow v_{3}+v_{2}/2$

. This gives

$$ \begin{align}& f_{{\boldsymbol{z}}}\left( {\boldsymbol{w}}\right) =\frac{1}{\left( 2\pi \mathrm{i}\right) ^{3}} \int_{\left( \mathrm{i}\mathbb{R}\right) ^{3}}\mathrm{e}^{v_{1}\tilde{w}_{1}+v_{2}\left( w_{2}+ \tilde{w}_{3}\right) +2v_{3}\tilde{w}_{3}} \notag \\ &\quad\sqrt{c}\left( \left( \frac{c+\beta _{-}}{2}+v_{3}\right) \left( 1+d+c\right) ^{T}+\left( \frac{c-\beta _{-}}{2}-v_{3}\right) \left( 1+d-c\right) ^{T}\!\right) ^{-\frac{1}{2}}\mathrm{d}\!\left( v_{1},v_{2},v_{3}\right), \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align}& f_{{\boldsymbol{z}}}\left( {\boldsymbol{w}}\right) =\frac{1}{\left( 2\pi \mathrm{i}\right) ^{3}} \int_{\left( \mathrm{i}\mathbb{R}\right) ^{3}}\mathrm{e}^{v_{1}\tilde{w}_{1}+v_{2}\left( w_{2}+ \tilde{w}_{3}\right) +2v_{3}\tilde{w}_{3}} \notag \\ &\quad\sqrt{c}\left( \left( \frac{c+\beta _{-}}{2}+v_{3}\right) \left( 1+d+c\right) ^{T}+\left( \frac{c-\beta _{-}}{2}-v_{3}\right) \left( 1+d-c\right) ^{T}\!\right) ^{-\frac{1}{2}}\mathrm{d}\!\left( v_{1},v_{2},v_{3}\right), \end{align} $$

where now

Readers not interested in complex analysis can skip the next two paragraphs and go to the statement of Theorem 1 below.

It is straightforward to integrate

![]() $v_{3}$

out by using the binomial expansion (twice) and exploiting the linearity of the integration operator. Since

$v_{3}$

out by using the binomial expansion (twice) and exploiting the linearity of the integration operator. Since

![]() $\varphi \left ( .\right ) $

is analytic in the neighborhood of the origin, the path of integration with respect to

$\varphi \left ( .\right ) $

is analytic in the neighborhood of the origin, the path of integration with respect to

![]() $v_{3}$

is deformed (by the Cauchy–Goursat theorem) into

$v_{3}$

is deformed (by the Cauchy–Goursat theorem) into

![]() $\mathcal {P}$

which lies to the right of the singularities of the integrand [see Abadir (Reference Abadir1993b) for details on such paths] and

$\mathcal {P}$

which lies to the right of the singularities of the integrand [see Abadir (Reference Abadir1993b) for details on such paths] and

$$ \begin{align*} f_{{\boldsymbol{z}}}\left( {\boldsymbol{w}}\right) &=\frac{1}{\left( 2\pi \mathrm{i}\right) ^{3}} \sum_{j=0}^{\infty }\binom{j-\frac{1}{2}}{j}\int_{\left( \mathrm{i}\mathbb{R}\right) ^{2}} \frac{\left( 1+d-c\right) ^{Tj}}{\left( 1+d+c\right) ^{T\left( j+\frac{1}{2} \right) }}\sqrt{c}\mathrm{e}^{v_{1}\tilde{w}_{1}+v_{2}\left( w_{2}+\tilde{w} _{3}\right) } \\ &\quad \int_{\mathcal{P}}\left( \frac{c+\beta _{-}}{2}+v_{3}\right) ^{-j-\frac{1}{ 2}}\left( -c+\frac{c+\beta _{-}}{2}+v_{3}\right) ^{j}\mathrm{e}^{2v_{3}\tilde{w}_{3}} \mathrm{d}\left( v_{3},v_{1},v_{2}\right) \\&=\frac{1}{\left( 2\pi \mathrm{i}\right) ^{3}}\sum_{j=0}^{\infty }\binom{j-\frac{1 }{2}}{j}\sum_{\ell =0}^{j}\binom{j}{\ell }\left( -1\right) ^{\ell }\\&\quad \int_{\left( \mathrm{i}\mathbb{R}\right) ^{2}}\frac{\left( 1+d-c\right) ^{Tj}}{\left( 1+d+c\right) ^{T\left( j+\frac{1}{2}\right) }}c^{\ell +\frac{1}{2}}\mathrm{e}^{v_{1} \tilde{w}_{1}+v_{2}\left( w_{2}+\tilde{w}_{3}\right) } \\ &\quad \int_{\mathcal{P}}\left( \frac{c+\beta _{-}}{2}+v_{3}\right) ^{-\ell - \frac{1}{2}}\mathrm{e}^{2v_{3}\tilde{w}_{3}}\mathrm{d}\left( v_{3},v_{1},v_{2}\right) \\ &=\frac{1}{\left( 2\pi \mathrm{i}\right) ^{2}\sqrt{2\tilde{w}_{3}}} \sum_{j=0}^{\infty }\binom{j-\frac{1}{2}}{j}\sum_{\ell =0}^{j}\binom{j}{\ell }\frac{\left( -2\tilde{w}_{3}\right) ^{\ell }}{\Gamma \left( \ell +\frac{1}{2 }\right) } \\ &\quad \int_{\left( \mathrm{i}\mathbb{R}\right) ^{2}}\frac{\left( 1+d-c\right) ^{Tj}}{\left( 1+d+c\right) ^{T\left( j+\frac{1}{2}\right) }}c^{\ell +\frac{1}{2}}\mathrm{e}^{v_{1} \tilde{w}_{1}+v_{2}\left( w_{2}+\tilde{w}_{3}\right) }\mathrm{e}^{-(c+\beta _{-}) \tilde{w}_{3}}\mathrm{d}\left( v_{1},v_{2}\right) , \end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*} f_{{\boldsymbol{z}}}\left( {\boldsymbol{w}}\right) &=\frac{1}{\left( 2\pi \mathrm{i}\right) ^{3}} \sum_{j=0}^{\infty }\binom{j-\frac{1}{2}}{j}\int_{\left( \mathrm{i}\mathbb{R}\right) ^{2}} \frac{\left( 1+d-c\right) ^{Tj}}{\left( 1+d+c\right) ^{T\left( j+\frac{1}{2} \right) }}\sqrt{c}\mathrm{e}^{v_{1}\tilde{w}_{1}+v_{2}\left( w_{2}+\tilde{w} _{3}\right) } \\ &\quad \int_{\mathcal{P}}\left( \frac{c+\beta _{-}}{2}+v_{3}\right) ^{-j-\frac{1}{ 2}}\left( -c+\frac{c+\beta _{-}}{2}+v_{3}\right) ^{j}\mathrm{e}^{2v_{3}\tilde{w}_{3}} \mathrm{d}\left( v_{3},v_{1},v_{2}\right) \\&=\frac{1}{\left( 2\pi \mathrm{i}\right) ^{3}}\sum_{j=0}^{\infty }\binom{j-\frac{1 }{2}}{j}\sum_{\ell =0}^{j}\binom{j}{\ell }\left( -1\right) ^{\ell }\\&\quad \int_{\left( \mathrm{i}\mathbb{R}\right) ^{2}}\frac{\left( 1+d-c\right) ^{Tj}}{\left( 1+d+c\right) ^{T\left( j+\frac{1}{2}\right) }}c^{\ell +\frac{1}{2}}\mathrm{e}^{v_{1} \tilde{w}_{1}+v_{2}\left( w_{2}+\tilde{w}_{3}\right) } \\ &\quad \int_{\mathcal{P}}\left( \frac{c+\beta _{-}}{2}+v_{3}\right) ^{-\ell - \frac{1}{2}}\mathrm{e}^{2v_{3}\tilde{w}_{3}}\mathrm{d}\left( v_{3},v_{1},v_{2}\right) \\ &=\frac{1}{\left( 2\pi \mathrm{i}\right) ^{2}\sqrt{2\tilde{w}_{3}}} \sum_{j=0}^{\infty }\binom{j-\frac{1}{2}}{j}\sum_{\ell =0}^{j}\binom{j}{\ell }\frac{\left( -2\tilde{w}_{3}\right) ^{\ell }}{\Gamma \left( \ell +\frac{1}{2 }\right) } \\ &\quad \int_{\left( \mathrm{i}\mathbb{R}\right) ^{2}}\frac{\left( 1+d-c\right) ^{Tj}}{\left( 1+d+c\right) ^{T\left( j+\frac{1}{2}\right) }}c^{\ell +\frac{1}{2}}\mathrm{e}^{v_{1} \tilde{w}_{1}+v_{2}\left( w_{2}+\tilde{w}_{3}\right) }\mathrm{e}^{-(c+\beta _{-}) \tilde{w}_{3}}\mathrm{d}\left( v_{1},v_{2}\right) , \end{align*} $$

where we use an elementary Laplace inversion by, e.g., simplifying page 11 of volume 5 of Prudnikov, Brychkov, and Marichev (Reference Prudnikov, Brychkov and Marichev1992) and using the Kummer function’s reduction

![]() $ _{1}F_{1}(a;a;w)=\exp (w)$

.

$ _{1}F_{1}(a;a;w)=\exp (w)$

.

The integrand for

![]() $v_{1},v_{2}$

has two classes of singularities, the branch points defined by

$v_{1},v_{2}$

has two classes of singularities, the branch points defined by

![]() $c=0$

and singularities defined by

$c=0$

and singularities defined by

![]() $c=-d-1$

. Using (8), these translate to the points defined by either of

$c=-d-1$

. Using (8), these translate to the points defined by either of

![]() $v_{2}+\beta =\pm \left ( v_{1}-\alpha \right ) $

or

$v_{2}+\beta =\pm \left ( v_{1}-\alpha \right ) $

or

![]() $v_{1}=\alpha $

. When

$v_{1}=\alpha $

. When

![]() $\alpha \neq 0$

, the latter point is not possible along the path of integration

$\alpha \neq 0$

, the latter point is not possible along the path of integration

![]() $v_{1}\in \mathrm {i} \mathbb {R}$

; and when

$v_{1}\in \mathrm {i} \mathbb {R}$

; and when

![]() $\alpha =0$

, the point

$\alpha =0$

, the point

![]() $v_{1}=0$

is a removable singularity of the moment generating function (yielding the marginal moment generating function for

$v_{1}=0$

is a removable singularity of the moment generating function (yielding the marginal moment generating function for

![]() $z_{1},z_{3}$

). The singularities affecting the integral are therefore exclusively the branch points satisfying

$z_{1},z_{3}$

). The singularities affecting the integral are therefore exclusively the branch points satisfying

and their real parts are negative. This allows the path of integration with respect to

![]() $v_{2}$

to be deformed into

$v_{2}$

to be deformed into

![]() $\mathcal {P}$

, an arbitrary path that lies to the right of the branch points in the complex plane for

$\mathcal {P}$

, an arbitrary path that lies to the right of the branch points in the complex plane for

![]() $v_{2}$

. This arbitrary path is unaffected by the change of variable

$v_{2}$

. This arbitrary path is unaffected by the change of variable

![]() $ v_{2}\leftrightarrow v_{2}-\beta $

(so that

$ v_{2}\leftrightarrow v_{2}-\beta $

(so that

![]() $d+1\leftrightarrow v_{2}$

). Furthermore, (arbitrary)

$d+1\leftrightarrow v_{2}$

). Furthermore, (arbitrary)

![]() $\mathcal {P}$

can be chosen in such a way that the path implied by

$\mathcal {P}$

can be chosen in such a way that the path implied by

![]() $v_{1}\leftrightarrow \mathrm {i} v_{1}+\alpha $

can be deformed to

$v_{1}\leftrightarrow \mathrm {i} v_{1}+\alpha $

can be deformed to

![]() $ \mathbb {R}$

. Combining both transformations and using

$ \mathbb {R}$

. Combining both transformations and using

![]() $\beta +\beta _{-}=1$

,

$\beta +\beta _{-}=1$

,

$$ \begin{align*} f_{{\boldsymbol{z}}}\left( {\boldsymbol{w}}\right) &=\frac{1}{\left( 2\pi \right) ^{2}\mathrm{i}\sqrt{2 \tilde{w}_{3}}}\mathrm{e}^{\alpha \tilde{w}_{1}-\beta w_{2}-\tilde{w} _{3}}\sum_{j=0}^{\infty }\binom{j-\frac{1}{2}}{j}\sum_{\ell =0}^{j}\binom{j}{ \ell }\frac{\left( -2\tilde{w}_{3}\right) ^{\ell }}{\Gamma \left( \ell + \frac{1}{2}\right) } \\ &\!\!\!\!\!\int_{\mathcal{P}}\int_{\mathbb{R}}\frac{\left( v_{2}-\sqrt{v_{2}^{2}+v_{1}^{2}} \right) ^{Tj}}{\left( v_{2}+\sqrt{v_{2}^{2}+v_{1}^{2}}\right) ^{T\left( j+ \frac{1}{2}\right) }}\left( v_{2}^{2}+v_{1}^{2}\right) ^{\frac{\ell }{2}+ \frac{1}{4}}\mathrm{e}^{\mathrm{i} v_{1}\tilde{w}_{1}+v_{2}\left( w_{2}+\tilde{w} _{3}\right) -\tilde{w}_{3}\sqrt{v_{2}^{2}+v_{1}^{2}}}\mathrm{d}\left( v_{1},v_{2}\right) , \end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*} f_{{\boldsymbol{z}}}\left( {\boldsymbol{w}}\right) &=\frac{1}{\left( 2\pi \right) ^{2}\mathrm{i}\sqrt{2 \tilde{w}_{3}}}\mathrm{e}^{\alpha \tilde{w}_{1}-\beta w_{2}-\tilde{w} _{3}}\sum_{j=0}^{\infty }\binom{j-\frac{1}{2}}{j}\sum_{\ell =0}^{j}\binom{j}{ \ell }\frac{\left( -2\tilde{w}_{3}\right) ^{\ell }}{\Gamma \left( \ell + \frac{1}{2}\right) } \\ &\!\!\!\!\!\int_{\mathcal{P}}\int_{\mathbb{R}}\frac{\left( v_{2}-\sqrt{v_{2}^{2}+v_{1}^{2}} \right) ^{Tj}}{\left( v_{2}+\sqrt{v_{2}^{2}+v_{1}^{2}}\right) ^{T\left( j+ \frac{1}{2}\right) }}\left( v_{2}^{2}+v_{1}^{2}\right) ^{\frac{\ell }{2}+ \frac{1}{4}}\mathrm{e}^{\mathrm{i} v_{1}\tilde{w}_{1}+v_{2}\left( w_{2}+\tilde{w} _{3}\right) -\tilde{w}_{3}\sqrt{v_{2}^{2}+v_{1}^{2}}}\mathrm{d}\left( v_{1},v_{2}\right) , \end{align*} $$

where we can use

![]() $\int _{\mathbb {R}}=2\int _{\mathbb {R}_{+}}$

since the integrand is an even function of

$\int _{\mathbb {R}}=2\int _{\mathbb {R}_{+}}$

since the integrand is an even function of

![]() $v_{1}$

. Furthermore, expanding

$v_{1}$

. Furthermore, expanding

![]() $((v_{2}^{2}+v_{1}^{2})^{1/2})^{\ell +3/2}$

in the neighborhood of the numerator of the displayed fraction, and using

$((v_{2}^{2}+v_{1}^{2})^{1/2})^{\ell +3/2}$

in the neighborhood of the numerator of the displayed fraction, and using

![]() $ (a-b)/(a+b)=(a^{2}-b^{2})/(a+b)^{2}$

,

$ (a-b)/(a+b)=(a^{2}-b^{2})/(a+b)^{2}$

,

$$ \begin{align*} f_{{\boldsymbol{z}}}\left( {\boldsymbol{w}}\right) &=\frac{1}{8\pi ^{2}\mathrm{i}\sqrt{\tilde{w}_{3}}}\mathrm{e} ^{\alpha \tilde{w}_{1}-\beta w_{2}-\tilde{w}_{3}}\sum_{j=0}^{\infty }\binom{ j-\frac{1}{2}}{j}\left( -1\right) ^{Tj}\sum_{\ell =0}^{j}\binom{j}{\ell } \frac{\left( -\tilde{w}_{3}\right) ^{\ell }}{\Gamma \left( \ell +\frac{1}{2} \right) }\sum_{k=0}^{\infty }\binom{\ell +\frac{3}{2}}{k} \\ &\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\int_{\mathbb{R}_{+}}\int_{\mathcal{P}}\frac{v_{1}^{2Tj+2k}\cos \left( v_{1} \tilde{w}_{1}\right) }{\left( \sqrt{v_{2}^{2}+v_{1}^{2}}+v_{2}\right) ^{T\left( 2j+\frac{1}{2}\right) +2k-\ell -\frac{3}{2}}\sqrt{ v_{2}^{2}+v_{1}^{2}}}\mathrm{e}^{v_{2}w_{2}-\tilde{w}_{3}\left( \sqrt{ v_{2}^{2}+v_{1}^{2}}-v_{2}\right) }\mathrm{d}\left( v_{2},v_{1}\right) \end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*} f_{{\boldsymbol{z}}}\left( {\boldsymbol{w}}\right) &=\frac{1}{8\pi ^{2}\mathrm{i}\sqrt{\tilde{w}_{3}}}\mathrm{e} ^{\alpha \tilde{w}_{1}-\beta w_{2}-\tilde{w}_{3}}\sum_{j=0}^{\infty }\binom{ j-\frac{1}{2}}{j}\left( -1\right) ^{Tj}\sum_{\ell =0}^{j}\binom{j}{\ell } \frac{\left( -\tilde{w}_{3}\right) ^{\ell }}{\Gamma \left( \ell +\frac{1}{2} \right) }\sum_{k=0}^{\infty }\binom{\ell +\frac{3}{2}}{k} \\ &\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\int_{\mathbb{R}_{+}}\int_{\mathcal{P}}\frac{v_{1}^{2Tj+2k}\cos \left( v_{1} \tilde{w}_{1}\right) }{\left( \sqrt{v_{2}^{2}+v_{1}^{2}}+v_{2}\right) ^{T\left( 2j+\frac{1}{2}\right) +2k-\ell -\frac{3}{2}}\sqrt{ v_{2}^{2}+v_{1}^{2}}}\mathrm{e}^{v_{2}w_{2}-\tilde{w}_{3}\left( \sqrt{ v_{2}^{2}+v_{1}^{2}}-v_{2}\right) }\mathrm{d}\left( v_{2},v_{1}\right) \end{align*} $$

after reversing the order of integration. After a correction of page 64 of volume 5 of Prudnikov et al. (Reference Prudnikov, Brychkov and Marichev1992) [missing

![]() $\exp \left ( ap\right ) $

], we have the inversion

$\exp \left ( ap\right ) $

], we have the inversion

$$ \begin{align*} f_{{\boldsymbol{z}}}\left( {\boldsymbol{w}}\right) &=\frac{1}{4\pi \sqrt{\tilde{w}_{3}}}\mathrm{e}^{\alpha \tilde{w}_{1}-\beta w_{2}-\tilde{w}_{3}}\sum_{j=0}^{\infty }\binom{j-\frac{1 }{2}}{j}\left( -1\right) ^{Tj}\sum_{\ell =0}^{j}\binom{j}{\ell }\frac{\left( -\tilde{w}_{3}\right) ^{\ell }}{\Gamma \left( \ell +\frac{1}{2}\right) } \sum_{k=0}^{\infty }\binom{\ell +\frac{3}{2}}{k} \\ &\quad\left( \frac{w_{2}}{w_{2}+2\tilde{w}_{3}}\right) ^{T\left( j+\frac{1}{4} \right) +k-\frac{\ell }{2}-\frac{3}{4}}\int_{\mathbb{R}_{+}}v_{1}^{\ell +\frac{3-T}{ 2}}\\&\quad \cos \left( v_{1}\tilde{w}_{1}\right) J_{T\left( 2j+\frac{1}{2}\right) +2k-\ell -\frac{3}{2}}\left( v_{1}\sqrt{w_{2}\left( w_{2}+2\tilde{w} _{3}\right) }\right) \mathrm{d}v_{1}, \end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*} f_{{\boldsymbol{z}}}\left( {\boldsymbol{w}}\right) &=\frac{1}{4\pi \sqrt{\tilde{w}_{3}}}\mathrm{e}^{\alpha \tilde{w}_{1}-\beta w_{2}-\tilde{w}_{3}}\sum_{j=0}^{\infty }\binom{j-\frac{1 }{2}}{j}\left( -1\right) ^{Tj}\sum_{\ell =0}^{j}\binom{j}{\ell }\frac{\left( -\tilde{w}_{3}\right) ^{\ell }}{\Gamma \left( \ell +\frac{1}{2}\right) } \sum_{k=0}^{\infty }\binom{\ell +\frac{3}{2}}{k} \\ &\quad\left( \frac{w_{2}}{w_{2}+2\tilde{w}_{3}}\right) ^{T\left( j+\frac{1}{4} \right) +k-\frac{\ell }{2}-\frac{3}{4}}\int_{\mathbb{R}_{+}}v_{1}^{\ell +\frac{3-T}{ 2}}\\&\quad \cos \left( v_{1}\tilde{w}_{1}\right) J_{T\left( 2j+\frac{1}{2}\right) +2k-\ell -\frac{3}{2}}\left( v_{1}\sqrt{w_{2}\left( w_{2}+2\tilde{w} _{3}\right) }\right) \mathrm{d}v_{1}, \end{align*} $$

where

![]() $J_{.}\left ( .\right ) $

is the Bessel function of the first kind.

$J_{.}\left ( .\right ) $

is the Bessel function of the first kind.

The final integral, a Mellin transform, is obtained by page 192 of volume 2 of Prudnikov et al. (Reference Prudnikov, Brychkov and Marichev1986) and, bearing in mind (2), we get the following result.

Theorem 1. The density of

![]() ${\boldsymbol {z}}$

is

${\boldsymbol {z}}$

is

$$ \begin{align} f_{{\boldsymbol{z}}}\left( {\boldsymbol{w}}\right) &=\frac{\left( w_{2}/2\right) ^{\frac{T}{2}-2}}{ 4\pi \sqrt{2\tilde{w}_{3}\left( w_{2}+2\tilde{w}_{3}\right) }}\mathrm{e}^{\alpha \tilde{w}_{1}-\beta w_{2}-\tilde{w}_{3}}\sum_{j=0}^{\infty }\binom{j-\frac{1 }{2}}{j}\left( -\frac{w_{2}}{w_{2}+2\tilde{w}_{3}}\right) ^{Tj} \notag \\ &\quad\sum_{\ell =0}^{j}\binom{j}{\ell }\frac{\left( -2\tilde{w} _{3}/w_{2}\right) ^{\ell }}{\Gamma \left( \ell +\frac{1}{2}\right) } \sum_{k=0}^{\infty }\binom{\ell +\frac{3}{2}}{k}\frac{\Gamma \left( Tj+k+ \frac{1}{2}\right) }{\Gamma \left( T\left( j+\frac{1}{2}\right) +k-\ell -1\right) }\left( \frac{w_{2}}{w_{2}+2\tilde{w}_{3}}\right) ^{k} \notag \\ &\quad\,_{2}F_{1}\left( -T\left( j+\frac{1}{2}\right) -k+\ell +2,Tj+k+\frac{1}{2} ;\frac{1}{2};\frac{\tilde{w}_{1}^{2}}{w_{2}\left( w_{2}+2\tilde{w} _{3}\right) }\right). \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} f_{{\boldsymbol{z}}}\left( {\boldsymbol{w}}\right) &=\frac{\left( w_{2}/2\right) ^{\frac{T}{2}-2}}{ 4\pi \sqrt{2\tilde{w}_{3}\left( w_{2}+2\tilde{w}_{3}\right) }}\mathrm{e}^{\alpha \tilde{w}_{1}-\beta w_{2}-\tilde{w}_{3}}\sum_{j=0}^{\infty }\binom{j-\frac{1 }{2}}{j}\left( -\frac{w_{2}}{w_{2}+2\tilde{w}_{3}}\right) ^{Tj} \notag \\ &\quad\sum_{\ell =0}^{j}\binom{j}{\ell }\frac{\left( -2\tilde{w} _{3}/w_{2}\right) ^{\ell }}{\Gamma \left( \ell +\frac{1}{2}\right) } \sum_{k=0}^{\infty }\binom{\ell +\frac{3}{2}}{k}\frac{\Gamma \left( Tj+k+ \frac{1}{2}\right) }{\Gamma \left( T\left( j+\frac{1}{2}\right) +k-\ell -1\right) }\left( \frac{w_{2}}{w_{2}+2\tilde{w}_{3}}\right) ^{k} \notag \\ &\quad\,_{2}F_{1}\left( -T\left( j+\frac{1}{2}\right) -k+\ell +2,Tj+k+\frac{1}{2} ;\frac{1}{2};\frac{\tilde{w}_{1}^{2}}{w_{2}\left( w_{2}+2\tilde{w} _{3}\right) }\right). \end{align} $$

The Gauss series

![]() $_{2}F_{1}$

in (9) is a finite series when T is even. Euler’s first transformation gives

$_{2}F_{1}$

in (9) is a finite series when T is even. Euler’s first transformation gives

$$ \begin{align} f_{{\boldsymbol{z}}}\left( {\boldsymbol{w}}\right) &=\frac{\left( \frac{w_{2}}{2}-\frac{\tilde{w} _{1}^{2}}{2\left( w_{2}+2\tilde{w}_{3}\right) }\right) ^{\frac{T}{2}-2}}{ 4\pi \sqrt{2\tilde{w}_{3}\left( w_{2}+2\tilde{w}_{3}\right) }}\mathrm{e}^{\alpha \tilde{w}_{1}-\beta w_{2}-\tilde{w}_{3}}\sum_{j=0}^{\infty }\binom{j-\frac{1 }{2}}{j} \left( -\frac{w_{2}}{w_{2}+2\tilde{w}_{3}}\right) ^{Tj}\sum_{\ell =0}^{j}\binom{j}{\ell } \notag \\ &\quad\frac{1}{\Gamma \left( \ell +\frac{1}{2}\right) }\left( -\frac{2\tilde{w} _{3}\left( w_{2}+2\tilde{w}_{3}\right) }{w_{2}\left( w_{2}+2\tilde{w} _{3}\right) -\tilde{w}_{1}^{2}}\right) ^{\ell } \sum_{k=0}^{\infty }\binom{ \ell +\frac{3}{2}}{k}\nonumber\\&\quad\frac{\Gamma \left( Tj+k+\frac{1}{2}\right) }{\Gamma \left( T\left( j+\frac{1}{2}\right) +k-\ell -1\right) }\left( \frac{w_{2}}{ w_{2}+2\tilde{w}_{3}}\right) ^{k} \notag \\ &\quad{}_{2}F_{1}\left( -Tj-k,T\left( j+\frac{1}{2}\right) +k-\ell -\frac{3}{2}; \frac{1}{2};\frac{\tilde{w}_{1}^{2}}{w_{2}\left( w_{2}+2\tilde{w}_{3}\right) }\right), \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} f_{{\boldsymbol{z}}}\left( {\boldsymbol{w}}\right) &=\frac{\left( \frac{w_{2}}{2}-\frac{\tilde{w} _{1}^{2}}{2\left( w_{2}+2\tilde{w}_{3}\right) }\right) ^{\frac{T}{2}-2}}{ 4\pi \sqrt{2\tilde{w}_{3}\left( w_{2}+2\tilde{w}_{3}\right) }}\mathrm{e}^{\alpha \tilde{w}_{1}-\beta w_{2}-\tilde{w}_{3}}\sum_{j=0}^{\infty }\binom{j-\frac{1 }{2}}{j} \left( -\frac{w_{2}}{w_{2}+2\tilde{w}_{3}}\right) ^{Tj}\sum_{\ell =0}^{j}\binom{j}{\ell } \notag \\ &\quad\frac{1}{\Gamma \left( \ell +\frac{1}{2}\right) }\left( -\frac{2\tilde{w} _{3}\left( w_{2}+2\tilde{w}_{3}\right) }{w_{2}\left( w_{2}+2\tilde{w} _{3}\right) -\tilde{w}_{1}^{2}}\right) ^{\ell } \sum_{k=0}^{\infty }\binom{ \ell +\frac{3}{2}}{k}\nonumber\\&\quad\frac{\Gamma \left( Tj+k+\frac{1}{2}\right) }{\Gamma \left( T\left( j+\frac{1}{2}\right) +k-\ell -1\right) }\left( \frac{w_{2}}{ w_{2}+2\tilde{w}_{3}}\right) ^{k} \notag \\ &\quad{}_{2}F_{1}\left( -Tj-k,T\left( j+\frac{1}{2}\right) +k-\ell -\frac{3}{2}; \frac{1}{2};\frac{\tilde{w}_{1}^{2}}{w_{2}\left( w_{2}+2\tilde{w}_{3}\right) }\right), \end{align} $$

which has

![]() $_{2}F_{1}$

as a finite sum for any T. The sum

$_{2}F_{1}$

as a finite sum for any T. The sum

![]() $\sum _{j}$

converges exponentially fast in j (typically only a couple of terms) while

$\sum _{j}$

converges exponentially fast in j (typically only a couple of terms) while

![]() $\sum _{\ell }$

is a finite series whose number of terms is bounded by a small j. For large k,

$\sum _{\ell }$

is a finite series whose number of terms is bounded by a small j. For large k,

![]() $\sum _{k}$

is an alternating series with diminishing terms, which is therefore convergent. The argument of the exponential term is

$\sum _{k}$

is an alternating series with diminishing terms, which is therefore convergent. The argument of the exponential term is

![]() $\alpha \tilde {w}_{1}-\beta w_{2}-\tilde {w}_{3}=-w_{3}/2$

, and it is the only component of the sufficient statistic

z

whose asymptotic normalization (by T) would not depend on

$\alpha \tilde {w}_{1}-\beta w_{2}-\tilde {w}_{3}=-w_{3}/2$

, and it is the only component of the sufficient statistic

z

whose asymptotic normalization (by T) would not depend on

![]() $\alpha $

.

$\alpha $

.

As is standard in series representations, and illustrated by (9) and (10) representing the same density, the form for

![]() $f_{{\boldsymbol {z}}}\left ( {\boldsymbol {w}} \right ) $

is not unique. Here, we have presented the most efficient one for a broad range of likely parameter (T and

$f_{{\boldsymbol {z}}}\left ( {\boldsymbol {w}} \right ) $

is not unique. Here, we have presented the most efficient one for a broad range of likely parameter (T and

![]() $\alpha $

) and argument (

$\alpha $

) and argument (

![]() ${\boldsymbol {w}}$

) values, trying to keep a form that is statistically interpretable (e.g., in terms of

${\boldsymbol {w}}$

) values, trying to keep a form that is statistically interpretable (e.g., in terms of

![]() $w_{2}+2\tilde {w}_{3}$

). To illustrate, for the case of extreme parameter values, letting

$w_{2}+2\tilde {w}_{3}$

). To illustrate, for the case of extreme parameter values, letting

$$ \begin{align*} \lambda :=1-\frac{\tilde{w}_{1}^{2}}{w_{2}\left( w_{2}+2\tilde{w}_{3}\right) }, \end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*} \lambda :=1-\frac{\tilde{w}_{1}^{2}}{w_{2}\left( w_{2}+2\tilde{w}_{3}\right) }, \end{align*} $$

when

![]() $\lambda \rightarrow 0,$

the theorem’s formula for the joint density becomes less efficient; so assuming T is odd, analytic continuation of

$\lambda \rightarrow 0,$

the theorem’s formula for the joint density becomes less efficient; so assuming T is odd, analytic continuation of

![]() $ _{2}F_{1}$

gives

$ _{2}F_{1}$

gives

$$ \begin{align} f_{{\boldsymbol{z}}}\left( {\boldsymbol{w}}\right) &=\frac{\left( \lambda w_{2}/2\right) ^{\frac{T}{2} -2}}{4\pi \sqrt{2\pi \tilde{w}_{3}\left( w_{2}+2\tilde{w}_{3}\right) }}\mathrm{e} ^{\alpha \tilde{w}_{1}-\beta w_{2}-\tilde{w}_{3}}\sum_{j=0}^{\infty }\binom{ j-\frac{1}{2}}{j}\left( \frac{w_{2}}{w_{2}+2\tilde{w}_{3}}\right) ^{Tj}\nonumber\\&\quad\sum_{\ell =0}^{j}\binom{j}{\ell }\frac{\Gamma \left( \frac{1}{2}-\ell \right) }{\Gamma \left( \frac{T}{2}-\ell -1\right) } \left( \frac{2\tilde{w}_{3}}{\lambda w_{2}}\right) ^{\ell }\sum_{k=0}^{\infty }\binom{\ell +\frac{3}{2}}{k}\left( -\frac{w_{2}}{w_{2}+2 \tilde{w}_{3}}\right) ^{k}\notag \\ &\quad {}_{2}F_{1}\left( -Tj-k,T\left( j+\frac{1}{2} \right) +k-\ell -\frac{3}{2};\frac{T}{2}-\ell -1;\lambda \right) .\qquad \quad \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} f_{{\boldsymbol{z}}}\left( {\boldsymbol{w}}\right) &=\frac{\left( \lambda w_{2}/2\right) ^{\frac{T}{2} -2}}{4\pi \sqrt{2\pi \tilde{w}_{3}\left( w_{2}+2\tilde{w}_{3}\right) }}\mathrm{e} ^{\alpha \tilde{w}_{1}-\beta w_{2}-\tilde{w}_{3}}\sum_{j=0}^{\infty }\binom{ j-\frac{1}{2}}{j}\left( \frac{w_{2}}{w_{2}+2\tilde{w}_{3}}\right) ^{Tj}\nonumber\\&\quad\sum_{\ell =0}^{j}\binom{j}{\ell }\frac{\Gamma \left( \frac{1}{2}-\ell \right) }{\Gamma \left( \frac{T}{2}-\ell -1\right) } \left( \frac{2\tilde{w}_{3}}{\lambda w_{2}}\right) ^{\ell }\sum_{k=0}^{\infty }\binom{\ell +\frac{3}{2}}{k}\left( -\frac{w_{2}}{w_{2}+2 \tilde{w}_{3}}\right) ^{k}\notag \\ &\quad {}_{2}F_{1}\left( -Tj-k,T\left( j+\frac{1}{2} \right) +k-\ell -\frac{3}{2};\frac{T}{2}-\ell -1;\lambda \right) .\qquad \quad \end{align} $$

Notice that this expression is now valid for any T, odd or otherwise, in spite of the earlier assumption of T odd to get (11) whose resulting

![]() $_{2}F_{1}$

is now a finite series for any T.

$_{2}F_{1}$

is now a finite series for any T.

3 THE DENSITY FUNCTION OF

$\hat { \alpha }$

$\hat { \alpha }$

The least-squares estimator

![]() $\hat {\alpha }$

can be written as

$\hat {\alpha }$

can be written as

![]() $\tilde {z} _{1}/z_{2}$

. Then, by the transformation theorem, we have the joint density of

$\tilde {z} _{1}/z_{2}$

. Then, by the transformation theorem, we have the joint density of

![]() $\left ( \hat {\alpha },z_{2},\tilde {z}_{3}\right ) $

from (9) as

$\left ( \hat {\alpha },z_{2},\tilde {z}_{3}\right ) $

from (9) as

$$ \begin{align*} &\frac{2^{1-\frac{T}{2}}}{\pi }\sum_{j=0}^{\infty }\binom{j-\frac{1}{2}}{j} \left( -1\right) ^{Tj}\sum_{\ell =0}^{j}\binom{j}{\ell }\frac{\left( -1\right) ^{\ell }}{\Gamma \left( \ell +\frac{1}{2}\right) } \sum_{k=0}^{\infty }\binom{\ell +\frac{3}{2}}{k}\frac{\Gamma \left( Tj+k+ \frac{1}{2}\right) }{\Gamma \left( T\left( j+\frac{1}{2}\right) +k-\ell -1\right) } \\&\quad\mathrm{e}^{\left( \alpha \hat{\alpha}-\beta \right) w_{2}-\tilde{w}_{3}}\frac{ w_{2}^{T\left( j+\frac{1}{2}\right) +k-\ell -1}\left( 2\tilde{w}_{3}\right) ^{\ell -\frac{1}{2}}}{\left( w_{2}+2\tilde{w}_{3}\right) ^{Tj+k+\frac{1}{2}}} \nonumber\\&\quad {}_{2}F_{1}\left( -T\left( j+\frac{1}{2}\right) -k+\ell +2,Tj+k+\frac{1}{2}; \frac{1}{2};\frac{\hat{\alpha}^{2}w_{2}}{w_{2}+2\tilde{w}_{3}}\right) , \end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*} &\frac{2^{1-\frac{T}{2}}}{\pi }\sum_{j=0}^{\infty }\binom{j-\frac{1}{2}}{j} \left( -1\right) ^{Tj}\sum_{\ell =0}^{j}\binom{j}{\ell }\frac{\left( -1\right) ^{\ell }}{\Gamma \left( \ell +\frac{1}{2}\right) } \sum_{k=0}^{\infty }\binom{\ell +\frac{3}{2}}{k}\frac{\Gamma \left( Tj+k+ \frac{1}{2}\right) }{\Gamma \left( T\left( j+\frac{1}{2}\right) +k-\ell -1\right) } \\&\quad\mathrm{e}^{\left( \alpha \hat{\alpha}-\beta \right) w_{2}-\tilde{w}_{3}}\frac{ w_{2}^{T\left( j+\frac{1}{2}\right) +k-\ell -1}\left( 2\tilde{w}_{3}\right) ^{\ell -\frac{1}{2}}}{\left( w_{2}+2\tilde{w}_{3}\right) ^{Tj+k+\frac{1}{2}}} \nonumber\\&\quad {}_{2}F_{1}\left( -T\left( j+\frac{1}{2}\right) -k+\ell +2,Tj+k+\frac{1}{2}; \frac{1}{2};\frac{\hat{\alpha}^{2}w_{2}}{w_{2}+2\tilde{w}_{3}}\right) , \end{align*} $$

where

![]() $\left ( \alpha \hat {\alpha }-\beta \right ) w_{2}-\tilde {w} _{3}=-w_{3}/2<0$

and we use a sleight of notation by writing

$\left ( \alpha \hat {\alpha }-\beta \right ) w_{2}-\tilde {w} _{3}=-w_{3}/2<0$

and we use a sleight of notation by writing

![]() $\hat {\alpha }$

for both the estimator and its realization (which should not lead to ambiguity in this context). To obtain the marginal density of

$\hat {\alpha }$

for both the estimator and its realization (which should not lead to ambiguity in this context). To obtain the marginal density of

![]() $\hat {\alpha }$

, we integrate out

$\hat {\alpha }$

, we integrate out

![]() $w_{2}\in \mathbb {R}_{+}$

and

$w_{2}\in \mathbb {R}_{+}$

and

![]() $\tilde {w}_{3}\in \mathbb {R}_{+}$

subject to the constraint from (2) that the argument of Gauss’ function is less than 1. By the change of variable

$\tilde {w}_{3}\in \mathbb {R}_{+}$

subject to the constraint from (2) that the argument of Gauss’ function is less than 1. By the change of variable

![]() $w_{2}/\left ( w_{2}+2\tilde {w} _{3}\right ) \leftrightarrow u$

or

$w_{2}/\left ( w_{2}+2\tilde {w} _{3}\right ) \leftrightarrow u$

or

![]() $w_{2}\leftrightarrow 2\tilde {w} _{3}u/\left ( 1-u\right ) $

, the marginal density of

$w_{2}\leftrightarrow 2\tilde {w} _{3}u/\left ( 1-u\right ) $

, the marginal density of

![]() $\hat {\alpha }$

is

$\hat {\alpha }$

is

$$ \begin{align*} f\left( \hat{\alpha}\right) &=\frac{1}{\pi }\sum_{j=0}^{\infty }\binom{j- \frac{1}{2}}{j}\left( -1\right) ^{Tj}\sum_{\ell =0}^{j}\binom{j}{\ell }\frac{ \left( -1\right) ^{\ell }}{\Gamma \left( \ell +\frac{1}{2}\right) } \sum_{k=0}^{\infty }\binom{\ell +\frac{3}{2}}{k}\nonumber\\&\quad\frac{\Gamma \left( Tj+k+ \frac{1}{2}\right) }{\Gamma \left( T\left( j+\frac{1}{2}\right) +k-\ell -1\right) }\int_{0}^{\theta }\int_{\mathbb{R}_{+}}\tilde{w}_{3}^{\frac{T}{2}-1} \\&\quad \exp \left[ -\left( 1-\tfrac{2\left( \alpha \hat{\alpha}-\beta \right) u}{ 1-u}\right) \tilde{w}_{3}\right] \frac{u^{T\left( j+\frac{1}{2}\right) +k-\ell -1}}{\left( 1-u\right) ^{\frac{T+1}{2}-\ell }}\nonumber\\&\quad{}_{2}F_{1}\left( -T\left( j+\tfrac{1}{2}\right) -k+\ell +2,Tj+k+\tfrac{1}{2};\tfrac{1}{2}; \hat{\alpha}^{2}u\right) \mathrm{d}\tilde{w}_{3}\mathrm{d}u, \end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*} f\left( \hat{\alpha}\right) &=\frac{1}{\pi }\sum_{j=0}^{\infty }\binom{j- \frac{1}{2}}{j}\left( -1\right) ^{Tj}\sum_{\ell =0}^{j}\binom{j}{\ell }\frac{ \left( -1\right) ^{\ell }}{\Gamma \left( \ell +\frac{1}{2}\right) } \sum_{k=0}^{\infty }\binom{\ell +\frac{3}{2}}{k}\nonumber\\&\quad\frac{\Gamma \left( Tj+k+ \frac{1}{2}\right) }{\Gamma \left( T\left( j+\frac{1}{2}\right) +k-\ell -1\right) }\int_{0}^{\theta }\int_{\mathbb{R}_{+}}\tilde{w}_{3}^{\frac{T}{2}-1} \\&\quad \exp \left[ -\left( 1-\tfrac{2\left( \alpha \hat{\alpha}-\beta \right) u}{ 1-u}\right) \tilde{w}_{3}\right] \frac{u^{T\left( j+\frac{1}{2}\right) +k-\ell -1}}{\left( 1-u\right) ^{\frac{T+1}{2}-\ell }}\nonumber\\&\quad{}_{2}F_{1}\left( -T\left( j+\tfrac{1}{2}\right) -k+\ell +2,Tj+k+\tfrac{1}{2};\tfrac{1}{2}; \hat{\alpha}^{2}u\right) \mathrm{d}\tilde{w}_{3}\mathrm{d}u, \end{align*} $$

where

![]() $\theta :=\min \left ( \hat {\alpha }^{-2},1\right ) $

. It is straightforward to marginalize the density with respect to

$\theta :=\min \left ( \hat {\alpha }^{-2},1\right ) $

. It is straightforward to marginalize the density with respect to

![]() $\tilde {w}_{3}\in \mathbb {R}_{+}$

by using the integral definition of the gamma function, and

$\tilde {w}_{3}\in \mathbb {R}_{+}$

by using the integral definition of the gamma function, and

$$ \begin{align} &f\left( \hat{\alpha}\right) =\frac{\Gamma \left( \frac{T}{2}\right) }{\pi } \sum_{j=0}^{\infty }\binom{j-\frac{1}{2}}{j}\left( -1\right) ^{Tj}\sum_{\ell =0}^{j}\binom{j}{\ell }\frac{\left( -1\right) ^{\ell }}{\Gamma \left( \ell + \frac{1}{2}\right) }\sum_{k=0}^{\infty }\binom{\ell +\frac{3}{2}}{k}\nonumber\\&\qquad\quad\frac{ \Gamma \left( Tj+k+\frac{1}{2}\right) }{\Gamma \left( T\left( j+\frac{1}{2} \right) +k-\ell -1\right) } \notag \\ &\int_{0}^{\theta }\frac{u^{T\left( j+\frac{1}{2}\right) +k-\ell -1}\left( 1-u\right) ^{\ell -\frac{1}{2}}\,_{2}F_{1}\left( -T\left( j+\frac{1}{2} \right) -k+\ell +2,Tj+k+\frac{1}{2};\frac{1}{2};\hat{\alpha}^{2}u\right) }{ \left( 1+\alpha \left( \alpha -2\hat{\alpha}\right) u\right) ^{\frac{T}{2}}} \mathrm{d}u,\quad \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} &f\left( \hat{\alpha}\right) =\frac{\Gamma \left( \frac{T}{2}\right) }{\pi } \sum_{j=0}^{\infty }\binom{j-\frac{1}{2}}{j}\left( -1\right) ^{Tj}\sum_{\ell =0}^{j}\binom{j}{\ell }\frac{\left( -1\right) ^{\ell }}{\Gamma \left( \ell + \frac{1}{2}\right) }\sum_{k=0}^{\infty }\binom{\ell +\frac{3}{2}}{k}\nonumber\\&\qquad\quad\frac{ \Gamma \left( Tj+k+\frac{1}{2}\right) }{\Gamma \left( T\left( j+\frac{1}{2} \right) +k-\ell -1\right) } \notag \\ &\int_{0}^{\theta }\frac{u^{T\left( j+\frac{1}{2}\right) +k-\ell -1}\left( 1-u\right) ^{\ell -\frac{1}{2}}\,_{2}F_{1}\left( -T\left( j+\frac{1}{2} \right) -k+\ell +2,Tj+k+\frac{1}{2};\frac{1}{2};\hat{\alpha}^{2}u\right) }{ \left( 1+\alpha \left( \alpha -2\hat{\alpha}\right) u\right) ^{\frac{T}{2}}} \mathrm{d}u,\quad \end{align} $$

where

![]() $2\beta -2\alpha \hat {\alpha }-1=\alpha \left ( \alpha -2\hat {\alpha } \right ) $

has been used. For T even,

$2\beta -2\alpha \hat {\alpha }-1=\alpha \left ( \alpha -2\hat {\alpha } \right ) $

has been used. For T even,

![]() $_{2}F_{1}$

terminates. Analytic continuation gives a terminating series for all T as

$_{2}F_{1}$

terminates. Analytic continuation gives a terminating series for all T as

$$ \begin{align*} &\frac{\Gamma \left( Tj+k+\frac{1}{2}\right) \,_{2}F_{1}\left( -T\left( j+ \frac{1}{2}\right) -k+\ell +2,Tj+k+\frac{1}{2};\frac{1}{2};\hat{\alpha} ^{2}u\right) }{\Gamma \left( T\left( j+\frac{1}{2}\right) +k-\ell -1\right) } \\ &=\frac{\sqrt{\pi }\left( {-}1\right) ^{Tj+k}\left( 1{-}\hat{\alpha} ^{2}u\right) ^{\frac{T}{2}-\ell -2}\,_{2}F_{1}\left( -Tj-k,T\left( j+\frac{1 }{2}\right) {+}k{-}\ell {-}\frac{3}{2}; \frac{T}{2}{-}\ell {-}1;1{-}\hat{ \alpha}^{2}u\right) }{\Gamma \left( \frac{T}{2}-\ell -1\right) }, \end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*} &\frac{\Gamma \left( Tj+k+\frac{1}{2}\right) \,_{2}F_{1}\left( -T\left( j+ \frac{1}{2}\right) -k+\ell +2,Tj+k+\frac{1}{2};\frac{1}{2};\hat{\alpha} ^{2}u\right) }{\Gamma \left( T\left( j+\frac{1}{2}\right) +k-\ell -1\right) } \\ &=\frac{\sqrt{\pi }\left( {-}1\right) ^{Tj+k}\left( 1{-}\hat{\alpha} ^{2}u\right) ^{\frac{T}{2}-\ell -2}\,_{2}F_{1}\left( -Tj-k,T\left( j+\frac{1 }{2}\right) {+}k{-}\ell {-}\frac{3}{2}; \frac{T}{2}{-}\ell {-}1;1{-}\hat{ \alpha}^{2}u\right) }{\Gamma \left( \frac{T}{2}-\ell -1\right) }, \end{align*} $$

where we have also used Euler’s reflection formula. Hence,

$$ \begin{align} f\left( \hat{\alpha}\right) &=\frac{\Gamma \left( \frac{T}{2}\right) }{ \sqrt{\pi }}\sum_{j=0}^{\infty }\binom{j-\frac{1}{2}}{j}\sum_{\ell =0}^{j} \binom{j}{\ell }\frac{\left( -1\right) ^{\ell }}{\Gamma \left( \ell +\frac{1 }{2}\right) \Gamma \left( \frac{T}{2}-\ell -1\right) }\nonumber\\&\quad\sum_{k=0}^{\infty } \binom{\ell +\frac{3}{2}}{k}\left( -1\right) ^{k}\int_{0}^{\theta }u^{T\left( j+\frac{1}{2}\right) +k-\ell -1} \notag \\ &\quad \frac{\left( 1-u\right) ^{\ell -\frac{1}{2}}\left( 1-\hat{\alpha} ^{2}u\right) ^{\frac{T}{2}-\ell -2}\,_{2}F_{1} \left( -Tj-k,T\left( j+\frac{1 }{2}\right) +k-\ell -\frac{3}{2};\frac{T}{2}-\ell -1;1-\hat{\alpha} ^{2}u\right)}{\left( 1+\alpha \left( \alpha -2\hat{\alpha}\right) u\right) ^{\frac{T}{2}}}\mathrm{d}u \notag \\ & =\frac{\Gamma \left( \frac{T}{2}\right) }{\sqrt{\pi }}\sum_{j=0}^{\infty } \binom{j-\frac{1}{2}}{j}\sum_{\ell =0}^{j}\binom{j}{\ell }\frac{\left( -1\right) ^{\ell }}{\Gamma \left( \ell +\frac{1}{2}\right) \Gamma \left( \frac{T}{2}-\ell -1\right) }\nonumber\\&\quad\sum_{k=0}^{\infty }\binom{\ell +\frac{3}{2}}{k} \left( -1\right) ^{k}\sum_{m=0}^{Tj+k}\binom{Tj+k}{m} \frac{\left( T\left( j+\frac{1}{2}\right) +k-\ell -\frac{3}{2}\right) _{m} }{\left( \frac{T}{2}-\ell -1\right) _{m}\left( -1\right) ^{m}}\notag \\ &\quad \int_{0}^{\theta }\frac{u^{T\left( j+\frac{1}{2}\right) +k-\ell -1}\left( 1-u\right) ^{\ell -\frac{1}{2}}\left( 1-\hat{\alpha}^{2}u\right) ^{\frac{T}{2 }+m-\ell -2}}{\left( \left( \alpha -\hat{\alpha}\right) ^{2}u+\left( 1-\hat{ \alpha}^{2}u\right) \right) ^{\frac{T}{2}}}\mathrm{d}u. \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} f\left( \hat{\alpha}\right) &=\frac{\Gamma \left( \frac{T}{2}\right) }{ \sqrt{\pi }}\sum_{j=0}^{\infty }\binom{j-\frac{1}{2}}{j}\sum_{\ell =0}^{j} \binom{j}{\ell }\frac{\left( -1\right) ^{\ell }}{\Gamma \left( \ell +\frac{1 }{2}\right) \Gamma \left( \frac{T}{2}-\ell -1\right) }\nonumber\\&\quad\sum_{k=0}^{\infty } \binom{\ell +\frac{3}{2}}{k}\left( -1\right) ^{k}\int_{0}^{\theta }u^{T\left( j+\frac{1}{2}\right) +k-\ell -1} \notag \\ &\quad \frac{\left( 1-u\right) ^{\ell -\frac{1}{2}}\left( 1-\hat{\alpha} ^{2}u\right) ^{\frac{T}{2}-\ell -2}\,_{2}F_{1} \left( -Tj-k,T\left( j+\frac{1 }{2}\right) +k-\ell -\frac{3}{2};\frac{T}{2}-\ell -1;1-\hat{\alpha} ^{2}u\right)}{\left( 1+\alpha \left( \alpha -2\hat{\alpha}\right) u\right) ^{\frac{T}{2}}}\mathrm{d}u \notag \\ & =\frac{\Gamma \left( \frac{T}{2}\right) }{\sqrt{\pi }}\sum_{j=0}^{\infty } \binom{j-\frac{1}{2}}{j}\sum_{\ell =0}^{j}\binom{j}{\ell }\frac{\left( -1\right) ^{\ell }}{\Gamma \left( \ell +\frac{1}{2}\right) \Gamma \left( \frac{T}{2}-\ell -1\right) }\nonumber\\&\quad\sum_{k=0}^{\infty }\binom{\ell +\frac{3}{2}}{k} \left( -1\right) ^{k}\sum_{m=0}^{Tj+k}\binom{Tj+k}{m} \frac{\left( T\left( j+\frac{1}{2}\right) +k-\ell -\frac{3}{2}\right) _{m} }{\left( \frac{T}{2}-\ell -1\right) _{m}\left( -1\right) ^{m}}\notag \\ &\quad \int_{0}^{\theta }\frac{u^{T\left( j+\frac{1}{2}\right) +k-\ell -1}\left( 1-u\right) ^{\ell -\frac{1}{2}}\left( 1-\hat{\alpha}^{2}u\right) ^{\frac{T}{2 }+m-\ell -2}}{\left( \left( \alpha -\hat{\alpha}\right) ^{2}u+\left( 1-\hat{ \alpha}^{2}u\right) \right) ^{\frac{T}{2}}}\mathrm{d}u. \end{align} $$

Considering the two cases of

![]() $\theta \equiv \min \left ( \hat {\alpha } ^{-2},1\right ) $

, which depend on the magnitude of

$\theta \equiv \min \left ( \hat {\alpha } ^{-2},1\right ) $

, which depend on the magnitude of

![]() $\hat {\alpha }$

rather than

$\hat {\alpha }$

rather than

![]() $\alpha $

, Section 5 contains the derivations that lead to the following result.

$\alpha $

, Section 5 contains the derivations that lead to the following result.

Theorem 2. The density of

![]() $\hat {\alpha }$

is, for

$\hat {\alpha }$

is, for

![]() $\hat {\alpha }^{2}<1,$

$\hat {\alpha }^{2}<1,$

$$ \begin{align} f\left( \hat{\alpha}\right) &=\frac{\Gamma \left( \frac{T}{2}\right) \left( 1-\hat{\alpha}^{2}\right) ^{\frac{T-3}{2}}}{\sqrt{\pi }\left( 1-\hat{\alpha} ^{2}+\left( \alpha -\hat{\alpha}\right) ^{2}\right) ^{\frac{T}{2}}} \sum_{j=0}^{\infty }\binom{j-\frac{1}{2}}{j}\nonumber\\&\quad\sum_{\ell =0}^{j}\binom{j}{\ell }\frac{\mathrm{B}\left( \ell +\frac{1}{2},T\left( j+\frac{1}{2}\right) -\ell \right) \left( -1\right) ^{\ell }}{\Gamma \left( \ell +\frac{1}{2}\right) \Gamma \left( \frac{T}{2}-\ell -1\right) } \notag \\ &\quad \sum_{k=0}^{\infty }\binom{\ell +\frac{3}{2}}{k}\frac{\left( T\left( j+ \frac{1}{2}\right) -\ell \right) _{k}\left( -1\right) ^{k}}{\left( T\left( j+ \frac{1}{2}\right) +\frac{1}{2}\right) _{k}}\nonumber\\&\quad \sum_{n=0}^{\infty }\binom{-\ell -\frac{1}{2}}{n}\frac{\left( T\left( j+\frac{1}{2}\right) +k-\ell -\frac{3}{2 }\right) _{n}\left( -\hat{\alpha}^{2}\right) ^{n}}{\left( T\left( j+\frac{1}{ 2}\right) +k+\frac{1}{2}\right) _{n}} \notag \\ &\quad \,_{2}F_{1}\left( \begin{array}{r} -Tj-k,T\left( j+\frac{1}{2}\right) +k+n-\ell -\frac{3}{2}; \\ \frac{T}{2}-\ell -1; \end{array} 1-\hat{\alpha}^{2}\right) \nonumber\\&\quad {}_{2}F_{1}\left( \begin{array}{r} \frac{T}{2},\ell +n+\frac{1}{2}; \\ T\left( j+\frac{1}{2}\right) +k+n+\frac{1}{2}; \end{array} \frac{\left( \alpha -\hat{\alpha}\right) ^{2}}{\left( \alpha -\hat{\alpha} \right) ^{2}+1-\hat{\alpha}^{2}}\right) , \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} f\left( \hat{\alpha}\right) &=\frac{\Gamma \left( \frac{T}{2}\right) \left( 1-\hat{\alpha}^{2}\right) ^{\frac{T-3}{2}}}{\sqrt{\pi }\left( 1-\hat{\alpha} ^{2}+\left( \alpha -\hat{\alpha}\right) ^{2}\right) ^{\frac{T}{2}}} \sum_{j=0}^{\infty }\binom{j-\frac{1}{2}}{j}\nonumber\\&\quad\sum_{\ell =0}^{j}\binom{j}{\ell }\frac{\mathrm{B}\left( \ell +\frac{1}{2},T\left( j+\frac{1}{2}\right) -\ell \right) \left( -1\right) ^{\ell }}{\Gamma \left( \ell +\frac{1}{2}\right) \Gamma \left( \frac{T}{2}-\ell -1\right) } \notag \\ &\quad \sum_{k=0}^{\infty }\binom{\ell +\frac{3}{2}}{k}\frac{\left( T\left( j+ \frac{1}{2}\right) -\ell \right) _{k}\left( -1\right) ^{k}}{\left( T\left( j+ \frac{1}{2}\right) +\frac{1}{2}\right) _{k}}\nonumber\\&\quad \sum_{n=0}^{\infty }\binom{-\ell -\frac{1}{2}}{n}\frac{\left( T\left( j+\frac{1}{2}\right) +k-\ell -\frac{3}{2 }\right) _{n}\left( -\hat{\alpha}^{2}\right) ^{n}}{\left( T\left( j+\frac{1}{ 2}\right) +k+\frac{1}{2}\right) _{n}} \notag \\ &\quad \,_{2}F_{1}\left( \begin{array}{r} -Tj-k,T\left( j+\frac{1}{2}\right) +k+n-\ell -\frac{3}{2}; \\ \frac{T}{2}-\ell -1; \end{array} 1-\hat{\alpha}^{2}\right) \nonumber\\&\quad {}_{2}F_{1}\left( \begin{array}{r} \frac{T}{2},\ell +n+\frac{1}{2}; \\ T\left( j+\frac{1}{2}\right) +k+n+\frac{1}{2}; \end{array} \frac{\left( \alpha -\hat{\alpha}\right) ^{2}}{\left( \alpha -\hat{\alpha} \right) ^{2}+1-\hat{\alpha}^{2}}\right) , \end{align} $$

for

![]() $\hat {\alpha }^{2}>1,$

$\hat {\alpha }^{2}>1,$

$$ \begin{align} f\left( \hat{\alpha}\right) &=\frac{4}{T\left( 1-\hat{\alpha}^{-2}\right) ^{ \frac{3}{2}}\left\vert 2\hat{\alpha}\right\vert ^{T}}\sum_{j=0}^{\infty } \binom{j-\frac{1}{2}}{j}\left( 4\hat{\alpha}^{2}\right) ^{-Tj}\sum_{\ell =0}^{j}\binom{j}{\ell }\frac{\left( -4\hat{\alpha}^{2}\right) ^{\ell }}{ \mathrm{B}\left( \ell +\frac{1}{2},\frac{T+1}{2}-\ell \right) } \notag \\ &\quad\sum_{k=0}^{\infty }\binom{\ell +\frac{3}{2}}{k}\frac{\left( T\left( 2j+1\right) +2k-2\ell -3\right) _{3}}{\left( -4\hat{\alpha}^{2}\right) ^{k}}\nonumber\\&\quad \sum_{n=0}^{\infty }\frac{\left( T\left( 2j+1\right) +2k+n-2\ell -1\right) _{n}}{n!\left( 4\hat{\alpha}^{2}\right) ^{n}\left( T\left( 2j+1\right) +2k+2n-2\ell -3\right) _{2}} \notag \\&\quad\,_{3}F_{2}\left( \begin{array}{r} \frac{T}{2},T\left( j+\frac{1}{2}\right) +k-\ell ,T\left( j+\frac{1}{2} \right) +k-\ell +\frac{1}{2}; \\ \frac{T+1}{2}-\ell ,T\left( 2j+1\right) +2k+n-2\ell -1; \end{array} 1-\frac{\left( \hat{\alpha}-\alpha \right) ^{2}}{\hat{\alpha}^{2}-1}\right) , \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} f\left( \hat{\alpha}\right) &=\frac{4}{T\left( 1-\hat{\alpha}^{-2}\right) ^{ \frac{3}{2}}\left\vert 2\hat{\alpha}\right\vert ^{T}}\sum_{j=0}^{\infty } \binom{j-\frac{1}{2}}{j}\left( 4\hat{\alpha}^{2}\right) ^{-Tj}\sum_{\ell =0}^{j}\binom{j}{\ell }\frac{\left( -4\hat{\alpha}^{2}\right) ^{\ell }}{ \mathrm{B}\left( \ell +\frac{1}{2},\frac{T+1}{2}-\ell \right) } \notag \\ &\quad\sum_{k=0}^{\infty }\binom{\ell +\frac{3}{2}}{k}\frac{\left( T\left( 2j+1\right) +2k-2\ell -3\right) _{3}}{\left( -4\hat{\alpha}^{2}\right) ^{k}}\nonumber\\&\quad \sum_{n=0}^{\infty }\frac{\left( T\left( 2j+1\right) +2k+n-2\ell -1\right) _{n}}{n!\left( 4\hat{\alpha}^{2}\right) ^{n}\left( T\left( 2j+1\right) +2k+2n-2\ell -3\right) _{2}} \notag \\&\quad\,_{3}F_{2}\left( \begin{array}{r} \frac{T}{2},T\left( j+\frac{1}{2}\right) +k-\ell ,T\left( j+\frac{1}{2} \right) +k-\ell +\frac{1}{2}; \\ \frac{T+1}{2}-\ell ,T\left( 2j+1\right) +2k+n-2\ell -1; \end{array} 1-\frac{\left( \hat{\alpha}-\alpha \right) ^{2}}{\hat{\alpha}^{2}-1}\right) , \end{align} $$

and, for points in the neighborhood of

![]() $\hat {\alpha }^{2}=1,$

$\hat {\alpha }^{2}=1,$

$$ \begin{align} f\left( \hat{\alpha}\right) =\frac{1}{\pi \mathrm{B}\left( \frac{3}{2},\frac{ T-3}{2}\right) }\int_{0}^{\theta }\int_{0}^{1}\frac{\sqrt{\tilde{u}}\left( u\left( 1-\tilde{v}\right) \right) ^{\frac{3}{2}}\left( 4u\tilde{u}v\left( 1-v\right) +\frac{\left( 1-u\right) \left( 1-\tilde{v}\right) }{1-\tilde{v} ^{-T}}\right) ^{\frac{T-5}{2}}}{\sqrt{1-u}\sqrt{1-\tilde{v}^{T}}\left( \tilde{u}+\left( \alpha -\hat{\alpha}\right) ^{2}u\right) ^{\frac{T}{2}}} \mathrm{d}v\mathrm{d}u \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} f\left( \hat{\alpha}\right) =\frac{1}{\pi \mathrm{B}\left( \frac{3}{2},\frac{ T-3}{2}\right) }\int_{0}^{\theta }\int_{0}^{1}\frac{\sqrt{\tilde{u}}\left( u\left( 1-\tilde{v}\right) \right) ^{\frac{3}{2}}\left( 4u\tilde{u}v\left( 1-v\right) +\frac{\left( 1-u\right) \left( 1-\tilde{v}\right) }{1-\tilde{v} ^{-T}}\right) ^{\frac{T-5}{2}}}{\sqrt{1-u}\sqrt{1-\tilde{v}^{T}}\left( \tilde{u}+\left( \alpha -\hat{\alpha}\right) ^{2}u\right) ^{\frac{T}{2}}} \mathrm{d}v\mathrm{d}u \end{align} $$

with

![]() $\theta :=\min \left ( \hat {\alpha }^{-2},1\right ) $

,

$\theta :=\min \left ( \hat {\alpha }^{-2},1\right ) $

,

![]() $\tilde {u}:=1-\hat { \alpha }^{2}u,$

and

$\tilde {u}:=1-\hat { \alpha }^{2}u,$

and

![]() $\tilde {v}:=u\tilde {u}\left ( \sqrt {\tilde {u}^{-1}-1}+\mathrm {i} \right ) ^{2}\Big ( 1-2 \left ( 1+\mathrm {i}\sqrt {\tilde {u}^{-1}-1}\right ) \tilde {u} v\Big ) ^{2}$

.

$\tilde {v}:=u\tilde {u}\left ( \sqrt {\tilde {u}^{-1}-1}+\mathrm {i} \right ) ^{2}\Big ( 1-2 \left ( 1+\mathrm {i}\sqrt {\tilde {u}^{-1}-1}\right ) \tilde {u} v\Big ) ^{2}$

.

A few remarks are in order:

-

1. All the

$_{2}F_{1}$

functions above have argument less than

$_{2}F_{1}$

functions above have argument less than

$1$

. Whenever the argument is less than or equal to

$1$

. Whenever the argument is less than or equal to

$-1$

, this can be mapped to

$-1$

, this can be mapped to

$ \left [ \frac {1}{2},1\right ) $

by means of Euler’s second transformation, so that the straightforward expansion of the function can be used directly without recourse to special computational routines, although these are readily available and built into packages like MATLAB, Mathematica, Maple, and others. Similar comments apply to

$ \left [ \frac {1}{2},1\right ) $

by means of Euler’s second transformation, so that the straightforward expansion of the function can be used directly without recourse to special computational routines, although these are readily available and built into packages like MATLAB, Mathematica, Maple, and others. Similar comments apply to

$_{3}F_{2}$

, and these packages also readily handle imaginary numbers like in

$_{3}F_{2}$

, and these packages also readily handle imaginary numbers like in

$\tilde {v}$

of (16) whose integral gives a real-valued

$\tilde {v}$

of (16) whose integral gives a real-valued

$f(\hat {\alpha })$

because this is an exact (not approximate) expression of the density function.

$f(\hat {\alpha })$

because this is an exact (not approximate) expression of the density function. -

2. The case

$\hat {\alpha }=\alpha =\pm 1$

leads to a removable singularity in the moment generating function, which remains in the expansions here. At such a point, interpolation around

$\hat {\alpha }=\alpha =\pm 1$

leads to a removable singularity in the moment generating function, which remains in the expansions here. At such a point, interpolation around

$\hat {\alpha }=\alpha =\pm 1$

should be used instead, as a simple way to compute the limit. Alternatively, (16) is used in the computations below for

$\hat {\alpha }=\alpha =\pm 1$

should be used instead, as a simple way to compute the limit. Alternatively, (16) is used in the computations below for

$\hat {\alpha }^{2}=1$

and to confirm the values obtained for the density from both (14) and (15) as

$\hat {\alpha }^{2}=1$

and to confirm the values obtained for the density from both (14) and (15) as

$\hat {\alpha }^{2}$

approaches 1 where the series-representation formulas become numerically inefficient. Although a series expansion is obtainable, this double-integral was found to be very efficient and can be used in general in the neighborhood of

$\hat {\alpha }^{2}$

approaches 1 where the series-representation formulas become numerically inefficient. Although a series expansion is obtainable, this double-integral was found to be very efficient and can be used in general in the neighborhood of

$\hat {\alpha } ^{2}=1$

. See also Evans and Savin (Reference Evans and Savin1981) for an alternative formulation in terms of an integral and a derivative. In the limiting case of

$\hat {\alpha } ^{2}=1$

. See also Evans and Savin (Reference Evans and Savin1981) for an alternative formulation in terms of an integral and a derivative. In the limiting case of

$T\rightarrow \infty $

for

$T\rightarrow \infty $

for

$\left \vert \alpha \right \vert =1$

, Rao (Reference Rao1978) gives an integral representation that takes one page (his page 186) to list.

$\left \vert \alpha \right \vert =1$

, Rao (Reference Rao1978) gives an integral representation that takes one page (his page 186) to list. -

3. The sum in j (hence

$\sum _{\ell =0}^{j}$

also) is very efficient, converging exponentially fast in j and typically requiring only a couple of terms. The exception to this is when we take T down to the edge of the restriction

$\sum _{\ell =0}^{j}$

also) is very efficient, converging exponentially fast in j and typically requiring only a couple of terms. The exception to this is when we take T down to the edge of the restriction

$T>3$

, making the series [but not (16)] numerically inefficient and unstable. In practice, it is recommended that care be taken when

$T>3$

, making the series [but not (16)] numerically inefficient and unstable. In practice, it is recommended that care be taken when

$T<10$

. Moreover, if a high precision of the calculation is required for such small T, further analytic continuation could be needed in the theorem to prevent the denominator parameter of

$T<10$

. Moreover, if a high precision of the calculation is required for such small T, further analytic continuation could be needed in the theorem to prevent the denominator parameter of

$_{2}F_{1}$

becoming a negative integer or zero.

$_{2}F_{1}$

becoming a negative integer or zero. -

4. For (14),

$\,_{2}F_{1}\left ( ;;1-\hat {\alpha }^{2}\right ) $

is a finite series and, as

$\,_{2}F_{1}\left ( ;;1-\hat {\alpha }^{2}\right ) $

is a finite series and, as

$n\rightarrow \infty $

, by

$n\rightarrow \infty $

, by $$ \begin{align*} \,_{2}F_{1}\left( \begin{array}{r} \frac{T}{2},\ell +n+\frac{1}{2}; \\ T\left( j+\frac{1}{2}\right) +k+n+\frac{1}{2}; \end{array} \frac{\left( \alpha -\hat{\alpha}\right) ^{2}}{\left( \alpha -\hat{\alpha} \right) ^{2}+1-\hat{\alpha}^{2}}\right) \rightarrow \left( \frac{1-\hat{ \alpha}^{2}}{1-\hat{\alpha}^{2}+\left( \alpha -\hat{\alpha}\right) ^{2}} \right) ^{-T/2} \end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*} \,_{2}F_{1}\left( \begin{array}{r} \frac{T}{2},\ell +n+\frac{1}{2}; \\ T\left( j+\frac{1}{2}\right) +k+n+\frac{1}{2}; \end{array} \frac{\left( \alpha -\hat{\alpha}\right) ^{2}}{\left( \alpha -\hat{\alpha} \right) ^{2}+1-\hat{\alpha}^{2}}\right) \rightarrow \left( \frac{1-\hat{ \alpha}^{2}}{1-\hat{\alpha}^{2}+\left( \alpha -\hat{\alpha}\right) ^{2}} \right) ^{-T/2} \end{align*} $$

$_{1}F_{0}(a;w)=(1-w)^{-a}$

, hence,

$_{1}F_{0}(a;w)=(1-w)^{-a}$

, hence,

$\sum _{k}$

is convergent when

$\sum _{k}$

is convergent when

$\hat { \alpha }\neq 0$

. When

$\hat { \alpha }\neq 0$

. When

$\hat {\alpha }=0$

, the

$\hat {\alpha }=0$

, the

$_{2}F_{1}\left ( ;;1\right ) $

becomes a ratio of gamma functions [see (23)] and (17)by expanding the other

$_{2}F_{1}\left ( ;;1\right ) $

becomes a ratio of gamma functions [see (23)] and (17)by expanding the other $$ \begin{align} f\left( 0\right) &=\frac{1}{\pi \left( 1+\alpha ^{2}\right) ^{\frac{T}{2}}} \sum_{j=0}^{\infty }\binom{j-\frac{1}{2}}{j}\mathrm{B}\left( \frac{T}{2},Tj+\frac{1}{2}\right) \left( -1\right) ^{Tj}\sum_{\ell =0}^{j} \binom{j}{\ell }\left( -1\right) ^{\ell } \notag \\ &\quad\sum_{n=0}^{\infty }\frac{\left( \frac{T}{2}\right) _{n}\left( \ell +\frac{ 1}{2}\right) _{n}\left( T\left( j+\frac{1}{2}\right) -\ell -1\right) }{ \left( T\left( j+\frac{1}{2}\right) +\frac{1}{2}\right) _{n}n!}\left( \frac{ \alpha ^{2}}{1+\alpha ^{2}}\right) ^{n} \notag \\ &\quad\,_{3}F_{2}\left( \begin{array}{r} -\ell -\frac{3}{2}, Tj+\frac{1}{2},T\left( j+\frac{1}{2}\right) -\ell; \\ T\left( j+\frac{1}{2}\right) +n+\frac{1}{2},T\left( j+\frac{1}{2}\right) -\ell -1; \end{array} -1\right) \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} f\left( 0\right) &=\frac{1}{\pi \left( 1+\alpha ^{2}\right) ^{\frac{T}{2}}} \sum_{j=0}^{\infty }\binom{j-\frac{1}{2}}{j}\mathrm{B}\left( \frac{T}{2},Tj+\frac{1}{2}\right) \left( -1\right) ^{Tj}\sum_{\ell =0}^{j} \binom{j}{\ell }\left( -1\right) ^{\ell } \notag \\ &\quad\sum_{n=0}^{\infty }\frac{\left( \frac{T}{2}\right) _{n}\left( \ell +\frac{ 1}{2}\right) _{n}\left( T\left( j+\frac{1}{2}\right) -\ell -1\right) }{ \left( T\left( j+\frac{1}{2}\right) +\frac{1}{2}\right) _{n}n!}\left( \frac{ \alpha ^{2}}{1+\alpha ^{2}}\right) ^{n} \notag \\ &\quad\,_{3}F_{2}\left( \begin{array}{r} -\ell -\frac{3}{2}, Tj+\frac{1}{2},T\left( j+\frac{1}{2}\right) -\ell; \\ T\left( j+\frac{1}{2}\right) +n+\frac{1}{2},T\left( j+\frac{1}{2}\right) -\ell -1; \end{array} -1\right) \end{align} $$

$ {}_{2}F_{1} $

and subsequently collecting the sum in k. The same analysis for

$ {}_{2}F_{1} $

and subsequently collecting the sum in k. The same analysis for

$ n\rightarrow \infty $

shows convergence in (17).

$ n\rightarrow \infty $

shows convergence in (17).

-

5. For (15), as

$n\rightarrow \infty $

, we have

$n\rightarrow \infty $

, we have

$ _{3}F_{2}\rightarrow 1$

and

$ _{3}F_{2}\rightarrow 1$

and

$\sum _{n}$

becomes the quadratic case with

$\sum _{n}$

becomes the quadratic case with $$ \begin{align*} _{2}F_{1}\left( a,a+\frac{1}{2};2a+2;\hat{\alpha}^{-2}\right) &=\left( 1- \hat{\alpha}^{-2}\right) ^{\frac{3}{2}}\,_{2}F_{1}\left( b,b+\frac{1}{2} ;2b-1;\hat{\alpha}^{-2}\right) \\ &=\left( 1-\hat{\alpha}^{-2}\right) ^{\frac{3}{2}}\frac{\xi -\left( 2a+1\right) \left( \xi -2\right) }{\left( 2a+2\right) \left( 2-\xi \right) ^{3}}\xi ^{2a+3} \end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*} _{2}F_{1}\left( a,a+\frac{1}{2};2a+2;\hat{\alpha}^{-2}\right) &=\left( 1- \hat{\alpha}^{-2}\right) ^{\frac{3}{2}}\,_{2}F_{1}\left( b,b+\frac{1}{2} ;2b-1;\hat{\alpha}^{-2}\right) \\ &=\left( 1-\hat{\alpha}^{-2}\right) ^{\frac{3}{2}}\frac{\xi -\left( 2a+1\right) \left( \xi -2\right) }{\left( 2a+2\right) \left( 2-\xi \right) ^{3}}\xi ^{2a+3} \end{align*} $$

$b:=a+\frac {3}{2}$

and

$b:=a+\frac {3}{2}$

and

$\hat {\alpha }^{-2}=4\left ( \xi -1\right ) /\xi ^{2}$

(or

$\hat {\alpha }^{-2}=4\left ( \xi -1\right ) /\xi ^{2}$

(or

$\xi =2\hat {\alpha }^{2}\pm 2\hat {\alpha }^{2}\sqrt {1-\hat {\alpha } ^{-2}}$

and taking the solution for a positive density) by page 460 of volume 3 of Prudnikov et al. (Reference Prudnikov, Brychkov and Marichev1986). For small

$\xi =2\hat {\alpha }^{2}\pm 2\hat {\alpha }^{2}\sqrt {1-\hat {\alpha } ^{-2}}$

and taking the solution for a positive density) by page 460 of volume 3 of Prudnikov et al. (Reference Prudnikov, Brychkov and Marichev1986). For small

$T,$

the formula is slower to converge as

$T,$

the formula is slower to converge as

$ \hat {\alpha }^{2}\rightarrow 1^{+}$

when

$ \hat {\alpha }^{2}\rightarrow 1^{+}$

when

$\alpha =1$

, but is fine for

$\alpha =1$

, but is fine for

$\alpha $

smaller, unlike (14) which converges fast everywhere. The speed of convergence of (15) improves as T increases. Formula (16) was used instead of (15) for

$\alpha $

smaller, unlike (14) which converges fast everywhere. The speed of convergence of (15) improves as T increases. Formula (16) was used instead of (15) for

$\hat { \alpha }^{2}$

up to 1.04 below, where the two formulas are efficiently calculated and give the same value of the density.

$\hat { \alpha }^{2}$

up to 1.04 below, where the two formulas are efficiently calculated and give the same value of the density.

-

6. When

$\alpha ^{2}<1$

, Taniguchi (Reference Taniguchi1991) and Marsh (Reference Marsh2001) find that Fisher’s z transformation (18)achieves approximate normality for the estimator. Such transformations fall within the sub-class of Gauss hypergeometric series having parameters

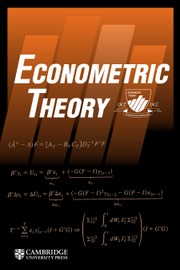

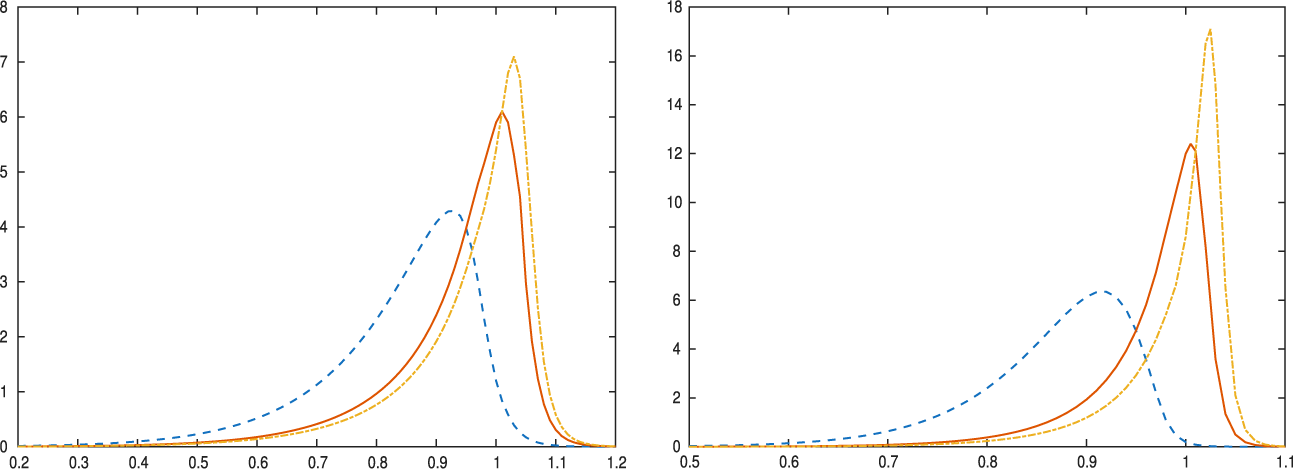

$\alpha ^{2}<1$