Introduction

The 2011 triple disaster of 3/11, comprising an earthquake, tsunami, and nuclear accident, profoundly affected Japanese society, inspiring numerous films and documentaries.Footnote 1 Amid a plethora of cultural responses to the event, Himizu (Reference Sono2012) was released. In this film, the Japanese director Sono Shion, who is distinctive for highlighting the contradictions within Japanese society in sharp and provocative ways, portrays the struggles of Sumida (played by Sometani Shōta), a boy subject to neglect and violence following 3/11, along with his classmate Chazawa (played by Nikaidō Fumi). Sumida, who lives in a dilapidated boat shop, is abandoned by his mother, severely abused by his father, and gradually alienated from the classroom that emphasizes hope and social bonds. Chazawa is also a victim of serious domestic violence, but she is not welcome anywhere. Sumida eventually leaves school, and Chazawa follows him to live in the boat shop.

Broadly, the film deals with the trauma that disasters inflict on young people and follows the model of a coming-of-age narrative about two adolescents who strive to protect themselves in a society in crisis. This paper, however, is less interested in story and genre than in two specific, cinematically rich settings in the film: the classroom and Sumida’s house. These places accrue strategic and symbolic significance when set against the government-led discourse on national recovery and the social norms (or politics of culture) of wa (和, social harmony), sontaku (忖度, anticipatory obedience), kizuna (絆, emotional bonds), and gaman (我慢, endurance), which collide and reveal cracks and tensions in the aftermath of the triple disaster. The slogans that echoed across Japan after the disaster, such as “ganbare Nippon” (Hang in there, Japan) and “ganbare Tōhoku,” synecdochized the state-led language and narrative of recovery. But for some disaster victims, there were violent demands for impossible endurance.Footnote 2 This implicit repression pervades and contorts the spaces of the classroom and Sumida’s house, and through spatial analysis, this paper will illuminate it.

In service of this, this paper uses Michel Foucault’s concept of “heterotopia” as a theoretical framework. Heterotopia refers to an exceptional conceptual space, wherein rules and logic that differ from the conventional social order operate. It is a space where different functions and norms are juxtaposed and cannot be fully explained by or integrated into the existing order (Foucault Reference Foucault1967). In this “other” place, “all the other real arrangements that can be found within society are simultaneously represented, challenged, and overturned” (Young Reference Young1998). In Himizu, the classroom and Sumida’s house, after the disaster cannot be reduced to a single meaning or function: in them, the resistance and deviation of marginalized subjects interact across material and affective dimensions. Therefore, heterotopia may serve as the most suitable theoretical framework for analyzing these juxtapositions and disruptions of order, as well as exceptions that fall outside existing norms. This concept is also crucial for uncovering sociopolitical contradictions embedded in specific sites: an epistemological challenge to universalized discourses and conventions about space. One question it raises is how effective the affirmative slogans of national recovery and normative social expectations, such as wa, sontaku, kizuna, and gaman, actually are for disaster victims to whom the state has not guaranteed even minimal housing stability. A heterotopia’s lens overlays the normalcy for which Japanese society strives with the lived experiences of disaster victims, so that we can discern the discrepancy between these values and their consequences. As much as heterotopia pertains to our conceptual understanding of space, it manifests strongly in specific locations such as prisons, hospitals, and schools. Therefore, this paper differentiates the concepts of “place” and “space.” As a minimal theorem, I use the word “place” to refer to the concrete, material locus upon which power, affect, and social forces converge, and “space” to conceptualize a network of dynamic, immaterial relations and structures.

This approach to Himizu will contribute to academic discourse by considering large-scale disasters through the lens of heterotopia; however, it is a controversial film in terms of its direction and reception. Initially, Himizu aimed to faithfully adapt Furuya Minoru’s original manga of the same name (Reference Furuya2001), narrativizing the anxieties of Japanese youth in the early 2000s.Footnote 3 However, following the triple disaster of 3/11, in an interview with Mastered, Sono asserted that “after the earthquake, I could not go on filming as if nothing had happened,” and urgently reconstructed his material to address the resonances between disaster trauma and both interpersonal and structural violence (2012).

This significantly altered narrative met with criticism. A key controversy was the on-site filming in Miyagi Prefecture, a disaster-stricken area, just two months after 3/11.Footnote 4 Sono described it as “a courageous decision and a responsibility” (Sono Reference Sono2012a: 122), adding that “the miserable scene unfolding before my eyes gave me a realistic sense of déjà vu, stirring more tension than guilt, which played a greater role” (Kimura Reference Kimura2013: 155). He further argued that “in documentaries, both the narrator and the interviewees speak in the past tense, which inevitably forces a kind of objectivity. But fiction allows the ability to go further—to step deeper into the experience.”Footnote 5 Despite his claim that it was an inevitable direction born of artistic intent, Sono himself acknowledged that the decision was subject to criticism (2012: 123). Specifically, filming in the disaster area right after the earthquake provoked a sensitive reaction from many people, especially in a context where the bereaved had yet to fully process their emotions. Critics such as Yoshida Morumotto and filmmaker Matsue Tetsuaki likewise point out that there was a backlash against Sono entering the disaster zone and creating a film more quickly than anyone else (2012: 192). Sono endeavored to criticize his society in real time through the heterotopic space of the disaster site; yet this attempt was criticized as ethically irresponsible, prioritizing artistic freedom over the affective needs of victims and local communities in Miyagi Prefecture.

Another controversy pertained to the regionalism of the disaster. Himizu obscures the sociopolitical context of each disaster by conflating the areas affected by the earthquake and tsunami with those impacted by the Fukushima nuclear accident, without any clear distinction (Thouny Reference Thouny2015: 21). Sono explained that he did not want to create a psychological distance between the audience and the film by specifying the location of the disaster (Sono Reference Sono2012: 122). However, Sono later acknowledged that combining distinct disaster zones in Himizu had led to confusion, an issue he addressed during the production of The Land of Hope (Kibō no kuni Reference Sono2012) (Kimura Reference Kimura2013: 155 and Thouny Reference Thouny2015: 21).Footnote 6

More specifically, Himizu includes extensive footage of the ruins caused by tsunamis and earthquakes, while narratively emphasizing the isolation and social stigma faced by disaster victims left in the radioactively contaminated Fukushima area under the control of the Japanese government and TEPCO. This chronological and geographical merging inelegantly conflates and oversimplifies the aftermaths of natural and manmade disasters, the spatial experiences of their victims, and their political contexts. A further issue casting a long shadow over all of Sono’s filmography is the revelation of sexual assault allegations made against the director.Footnote 7 These allegations have complicated the critical reception of his work. The reports first appeared in the Japanese weekly magazine Shūkan Josei, and no criminal charges or convictions have followed. Sono later apologized for his “lack of awareness as a film director” and “lack of consideration for those around [him],” while also claiming that the reports contained “many points that differ from the facts.” He subsequently filed a defamation lawsuit against the publisher of Shūkan Josei, which was settled in December 2023; the online articles in question were deleted entirely.Footnote 8

Against the backdrop of these claims, the way Sono’s filmmaking is characterized by “making violent and extravagant generic crossovers” and “testing the viewer’s taste” sits particularly uneasily (Jacobsson Reference Jacobsson2020: 171). Himizu embodies this confrontational style, which pervades the classroom and Sumida’s house and, in different ways, forcibly transforms these spaces into heterotopias. The classroom functions as a heterotopia amid a reinforced dominant ideology and beneath a veneer of normalcy, while Sumida’s house is transformed into a heterotopia through the collapse of everyday order. These spatial transformations, marked by rupture and excess, also reflect the violence and extravagance that Jacobsson identifies as central to Sono’s uncompromising style.

With this in mind, this paper uses the heterotopia of deviation, which sits among the six principles of heterotopia established by Foucault: (1) crisis and deviation, (2) displacement, (3) juxtaposition, (4) time, (5) opening and closing, and (6) illusion and compensation (Foucault Reference Foucault1967; Noor-ul-Ain, Sajjad and Ayesha Perveen Reference Noor-ul-Ain and Ayesha2019). First, I will examine the role of classrooms as ideological state apparatus (ISA) where normative and nationalistic values are reinforced following a disaster, analyzing how Sumida’s resistance transforms this classroom into a heterotopia of deviance. Next, I will turn my attention to Sumida’s house, considering how the presence of socially marginalized and excluded characters reconfigures it as a mixed heterotopia. Finally, I will summarize how the concept of heterotopia enhances our understanding of the complexities of place and enables us to critique the limitations of state-led reconstruction narratives.

The classroom: from an ISA space to a Heterotopia of deviance

According to Louis Althusser et al. (1969/Reference Althusser2009), educational institutions play a central role in the ideological state apparatus (ISA), systematically instilling and reproducing the dominant ideology (309–334). In the classroom, ideology is active on an imminent, quotidian, and personal level, and nationalist values and norms are systematically assimilated under social and structural pressure. In Sumida’s classroom, the teacher (played by Yashiba Toshihiro), an authoritative figure in the school, faithfully adheres to the logic of the ISA. His first method, as part of an effort to boost the morale of his disheartened students and alleviate the classroom atmosphere after the disaster, is to criticize the media coverage of the disaster. He speaks coercively with high authority, asking, “Why should we accept an overload of information as given?” Although nominally a question, this remark constitutes a complaint regarding the official news coverage about the dangers of radioactivity, the contamination of soil and oceans, and the vulnerable status of disaster victims. This reflects his concern that adverse news reports could undermine the government approach, embodied in its slogans, aimed at national recovery.

The teacher repeatedly reminds his students of their hereditary pride as Japanese people, aiming to inspire emotive patriotism in a confined environment where strict discipline is in effect. As a result, his classroom becomes permeated with ideologies, resulting in the students’ being unconsciously molded into ideological subjects (Althusser 1969). The teacher remarks:

The disaster has devastated Japan. Young people have never known their own country in turmoil. But we will do our best to pull ourselves together. It was a huge accident that you could not imagine […]. It was hard to accept reality. That is what it means to be Japanese! Japan experienced distress that nobody in the world has experienced. Now we Japanese are rising [emphasis mine] from the rubble, […]. We rose from the ashes of WW2 and became the world’s largest aid donor. After March 11, we needed aid again. Since the disaster, I have been thinking about what I can do. I had a vision. It was your face.

He hails individual students with the collective identity of “Japanese.” If the individual recognizes himself in this nomination, then he identifies as an ideological subject called “Japanese” and gains the qualification to internalize the emotions (pride) and actions (efforts to rebuild) definitional of that subject. This represents the core process of subject formation in the context of “interpellation” that Althusser describes (1969). The teacher’s close juxtaposition of expressions of destabilization such as “you could not imagine” and “devastated” with assertions about “rising” and “doing our best” attempts to resolve the anxiety of the victims of the unresolved disaster, and he interpolates national pride and unity as the rhetorical and affective bridge between their anxious, destabilized state and the “rising” recovery. Rather than engaging in discussions about their unrecovered trauma from the disaster, students absorb the expectation of “perfect recovery,” a unified and positive assertion that places the onus on their attitude, behavior and ideological loyalty. The students’ tacit compliance resonates with the traditional Japanese concept of wa (social harmony, 和), which emphasizes maintaining peace and stability within a group. The official explanation provided by the Japanese government for this term, considered a social norm and behavioral principle in Japanese society as a way to avoid conflict and prioritize peace, is “to imagine an atmosphere in which a group of people can comfortably and amicably coexist” (The Government of Japan, wa 2014). Although wa is recognized as a virtue of harmony and stability, it also serves as a controlling norm that suppresses conflict and standardizes group emotions. The students’ quietness in reaction to the teacher’s persistent message of hope exemplifies the effective role of wa in Sumida’s classroom.

However, unlike other students, Sumida exhibits a nonconformist attitude, which ruptures the classroom order dominated by the national ideology and turns the space into a “heterotopia of deviance.” This Foucauldian phrase refers to spaces where individuals whose behavior deviates from the required mean or norm are placed (Foucault Reference Foucault and Miskowiec1986). While Foucault’s examples emphasize purpose-built institutions such as prisons or asylums, in the case of Himizu’s classroom, Sumida’s challenge temporarily suspends its “normal” operation. It turns it into a space where deviance emerges, exposing the oppressive structure underneath. This transition does not alter the physical structure or institutional purpose of the classroom. Instead, the ideological function previously performed by the space is disrupted, and it is reconstituted into a space with exceptional latent characteristics.

At this point, the heterotopia of deviance foments tension, which is closer to unpredictable anxiety, in opposition to the affect that the teacher intentionally created in order to encourage patriotism. Furthermore, Sumida’s deviation illustrates that the more tightly organized a space is with discipline and control, the more evident even small deviant interventions are, easily revealing the vulnerability of the space. As the teacher highlights the aspirational unified strength of the Japanese people, Sumida exclaims, “Not everyone’s rising.” In response, the teacher approaches Sumida quickly, his expression displeased. This is a typical way in which teachers use their power to manage “entrance and exclusion” (Wood n.d.) and gestures obliquely toward the culture of corporal punishment still present in East Asian education systems (Kim Reference Kim2016: 111).

The teacher touches Sumida, lightly tugging his hair, showing his obvious displeasure at Sumida’s resistance to his claims. Although not the barbaric corporal punishment made illegal in the late 1940s in Japan, the teacher’s touch is rough and discomfiting (Kim Reference Kim2016: 111). While maintaining a smile, the teacher’s objective is to humiliate Sumida (Kim Reference Kim2016: 111–112). The public humiliation exemplifies the ISA’s disciplinary mechanism, which simultaneously disciplines the transgressive subject and imposes ideological subjugation upon the other students as witnesses.

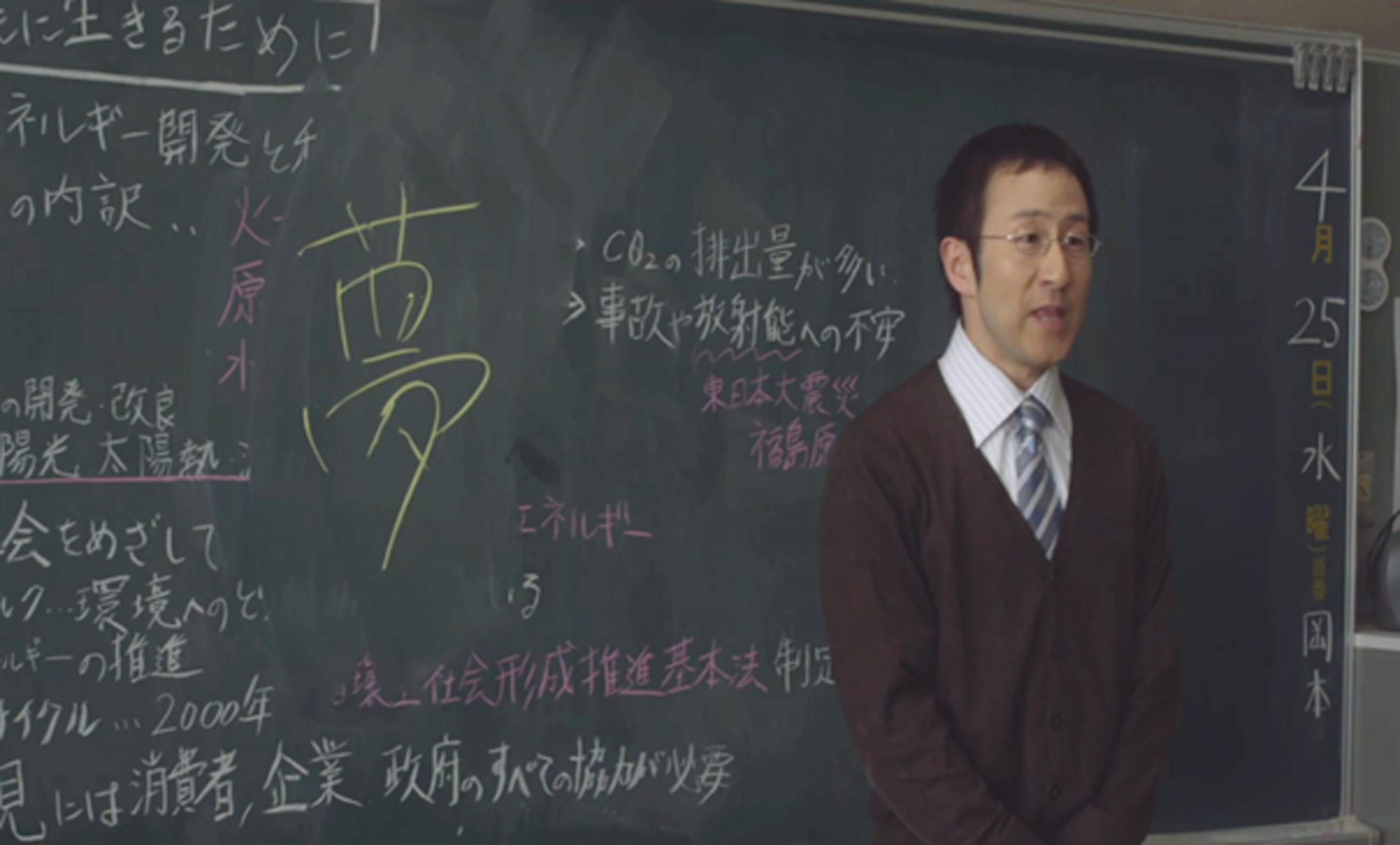

The teacher shouts at everyone, “People have to learn not to look down when living their lives. As Sumida’s family runs a boat business, ambition might not play a big part in his life. He might be an exception. But remember, every single one of you is special. Each of you is a flower like no other. There is no such thing as ordinary.” He concludes by telling Sumida, “Sumida! Don’t give up; have a dream!” Then he asks Sumida to repeat after him, “I am a one-of-a-kind flower, unique in all the world” (sekai ni hitotsu dake no hana). The camera focuses on the teacher sneering at Sumida as he stands in front of the blackboard, on which the character for “dream” (yume) is written largely, dominating the visual field. Refusing this call to be “one of a kind,” Sumida retorts, “Ordinary is the best!” (futsū saikō!). This resolute declaration rejects state-mandated optimism in favor of a path of deviation. Sumida willfully excludes himself from “the ideal Japanese” category by challenging the teacher’s idealistic opinions and disrupting the order of wa.

In this context, Sumida is the subject who breaks the wa but is also the destroyer of sontaku, (anticipatory obedience, 忖度), another of the elements of the Japanese identity tied to the ethos of wa. It refers to avoiding making claims that differ from the group’s so as not to stand out. Here, I mention wa and sontaku because Sumida’s deviation goes beyond merely breaking classroom rules: it challenges a broader social dynamic of emotional management, which is particularly pronounced in Japanese classrooms. The concepts of wa and sontaku, emphasizing harmony and self-censorship, are most evident in educational institutions; yet they also manifest in different forms and serve varied functions in settings including, but not limited to, corporate and bureaucratic environments. Sumida’s outburst can be seen as a radical act that stirs cultural taboos and posits fractures within the existing order, with Sumida functioning as the “deviant subject.” For Foucault, the category of the “deviant subject” refers to individuals constructed as deviations from norms. For instance, he points to the historico-discursive emergence of the “homosexual” as “a species,” in contrast to “homosexuality’” as an aberrant act (Foucault Reference Foucault1978: 43), thereby revealing how normative structures produce certain subjects as “other.” Reading Sumida in that light underscores that his resistance constitutes a reconfiguring of the classroom as a heterotopia where normative educational discourse is challenged.

Consequently, Sumida’s bravery in seeking mental liberation in opposition to the imposed order of the classroom is the inciting act of the film and is framed as admirable. Among his classmates, Chazawa in particular becomes captivated by Sumida’s defiance. This fascination perhaps reflects their shared experiences of domestic violence. However, they channel their responses to trauma in fundamentally different directions. While Sumida’s resistance will ultimately exteriorize as lethal violence against his father, Chazawa endures her abuse without resorting to violence, instead funneling her energy into supporting Sumida. Chazawa interprets Sumida’s anxiety as a struggle for life, as she may otherwise fear that the self she projects onto him would also collapse. This is because, as someone who is also enduring domestic violence, Chazawa must read Sumida’s resistance as a will to survive; otherwise, the hope for survival she invests in him would collapse along with her own. Chazawa’s obsessive and excessive behavior toward Sumida may make her appear unstable or unreliable, but in fact, she is a mature figure who serves as a compass, guiding Sumida to choose life over self-destruction.

Nevertheless, her support cannot expunge the deeper reality that Sumida’s resistance is rooted in profound existential anxiety, which ultimately manifests in destructive ways. As I will explain further in the next section, we will come to understand Sumida through Chazawa as a complex and problematic figure, at the boundary between resistance and violence, irreducible to either a hero or an antagonist. By the end of the film, we come to a fuller realization of what he means by “ordinary is the best.” Sumida does not want to be a “special person” who perseveres through hardship and sacrifice after the disaster; instead, he aspires to live as an “ordinary person”’ free from violence and coercion. As we will soon learn, Sumida’s wish is not easily fulfilled.

This paper now turns its eyes to Sumida’s house to observe how kizuna (emotional bonds) and gaman (endurance) function in a community of marginalized and excluded people. Sumida’s house is a complicated space in which three types of heterotopias—heterotopias of deviation, crisis, and compensation—interrelate. While I begin by examining how Sumida’s house functions as a heterotopia of deviance and crisis, the analysis will place the greatest emphasis on its role as a heterotopia of compensation. By doing so, I will explore how kizuna and gaman operate within the heterotopia of compensation. This analysis will elucidate how communities affected by disasters develop alternative forms of solidarity that simultaneously challenge and accommodate official narratives of national resilience. These tensions illuminate the complex interrelationships between state ideology and the lived experiences of marginalized populations.

Figure 1: Sumida in Himizu (Sono Shion Reference Sono2012). Photo credit: The New York Times (2014).

Figure 2: Screenshot of the classroom scene in Himizu (Reference Sono2012). Photo credit: Author.

The shanty house and the blue canvas shelter: heterotopia of crisis and heterotopia of deviation

“What do I wish for? Well, how can I say this, now that our lives have been saved from the tsunami, I hope nobody wants to end their own life. And it would be great for everybody to be able to work and get a place built to live in. That’s all” —Minani Sanriku (cited in Onaga et al. Reference Onaga2021: 488).

Figure 3: Sumida’s house and the disaster victims are isolated on a downhill slope. Photo Credit: Official Himizu Facebook page. Source: Facebook, https://www.facebook.com/photo/?fbid=364926853538257&set=ecnf.100075528087711.

Figure 4: The disaster victims’ blue canvas shelter. Photo Credit: Official Himizu Facebook page.

One of the most striking visuals in Himizu is Sumida’s shanty house, which serves as both the boat rental shop that sustains his livelihood, and his personal residence. It is also where the film’s intentions to address the devastation of the disaster are most clearly revealed. Surrounded by a lake next to the downhill road, far from the town, the makeshift house is crudely constructed with a poorly lit interior where Sumida, a middle school student who needs care and protection, must watch as his parents are severely abused and neglected by the state and community. This is Sumida’s only sanctuary, yet it also functions as a space in which he grapples with ongoing depression and anxiety. The complexity of Sumida’s house, where conflicting purposes coexist, is lucidly illustrated through the theoretical lens of heterotopia. More specifically, Sumida’s house is where the heterotopia of crisis (thesis), the heterotopia of deviation (antithesis), and the heterotopia of compensation (synthesis) interact in a dialectic.

Figure 5: Screenshot of Sumida’s mother looking at two disaster victims. Photo credit: Author.

Foucault defines heterotopias of crisis as privileged or forbidden spaces reserved for individuals considered to be in a state of crisis within a given society, such as adolescents, pregnant women, or the elderly. Although it does not fully align with the traditional, colloquial understanding of crisis, this definition underscores the significance of Sumida’s house. As mentioned in the previous classroom analysis, the heterotopia of deviance refers to a space where individuals who deviate from societal norms are placed (Foucault Reference Foucault and Miskowiec1986: 08). However, in this house, the function of the home is overturned, social norms disintegrate, and the heterotopias of crisis and deviation overlap. What stands out here is that “home” is regarded as one of the most representative spaces of everyday life (topia) in Foucault’s framework. Heterotopias are typically understood as exceptional spaces set apart from the spaces of everyday life, but in Himizu, the home becomes a heterotopia that embodies exception and destructiveness.

Sumida’s house no longer functions as a proper home. Instead, this space drives Sumida into a state of intense anxiety and crisis stemming from the threats of loan sharks, his mother’s indifference, and his father’s severe violence. In this context, the house operates as a failed heterotopia of crisis: rather than providing refuge during a transitional period, it perpetuates and intensifies the crisis. At the same time, the house functions as a paradigmatic heterotopia of deviation when it becomes the site of Sumida’s patricide, an act of extreme transgression. Repeated abuse and violence eventually compel Sumida to criminality. In this way, the house remains a precarious place that fails to address the crisis and instead perpetuates it by exacerbating and displacing it into acts of deviation.

Thus, Sumida’s house emblematizes how an ordinary topia loses its protective function and deteriorates into a paradoxical heterotopia, where the logics of crisis and deviation interplay. Sumida, seemingly attempting to address the chaos of abuse and violence in his home, permits disaster victims to reside in front of his house and fosters an ideal order through his bond with them. The space where such values are realized is in front of Sumida’s house, which serves as a physical and symbolic boundary. This liminal space can be understood as a heterotopia of compensation. In this case, it is an exceptional and highly contingent site that constructs an alternative, meticulously ordered reality to compensate for the disorder and absence in the real world.

The disaster victims fashion makeshift shelters out of blue tarpaulins in the yard, gradually transforming the exterior into a fragile but functioning communal space. Together with Sumida, they undertake small yet significant acts of resilience: collecting discarded oil drums, cleaning them, and repurposing them into improvised bathtubs. These gestures not only provide the basic means of hygiene, but also evoke the cultural significance of communal bathing as a restorative practice in Japan. Meanwhile, Chazawa works to revive Sumida’s boat rental business, creating promotional materials and temporarily running the establishment in an effort to reanimate the operation. In sharp contrast, the boathouse interior collapses into disorder, as Sumida’s self-hatred erupts into destructive gestures, most strikingly after killing his father, when he covers his body with paint in a moment of psychological disintegration. Perhaps Sumida’s destructive gesticulations are paradoxical attempts to impose order upon the chaos of self-hatred and psychological disintegration that followed his unethical act.

The exterior thus embodies the possibility of solidarity and improvised order, while the interior deteriorates into a site of self-destruction. This exterior space serves as a physical and symbolic boundary between the outside world and Sumida’s psychological atrophy.

Consequently, a single place (Sumida’s house) simultaneously accommodates two mutually negating worlds: hell and sanctuary. This is the enigmatic power of heterotopia. The house is both a site of deviance and the place where efforts to compensate for that deviance occur. This complex spatial arrangement thus functions as a heterotopia of compensation, which refers to an exceptional space that performs the function of supplementing and purifying the deficiencies and chaos of the real world. In the first sequence of Himizu, Sumida’s room is filled with news reports about residents unable to return to their hometowns owing to the detection of radioactive materials in Fukushima. We learn that this news relates to the story of five disaster victims who will soon settle in Sumida’s house. Unlike Sumida’s parents, those protecting him are disaster victims and homeless individuals who have lost everything in the disaster: Yoruno, Kenichi, Maa-kun, and the Tamura couple. Each of them has erected a shabby shelter using blue tarpaulins just outside Sumida’s house.

The film employs flashbacks to depict abandoned containers floating on the lake, evoking the trauma of these disaster victims. Those who have lost everything face fear and memories of loss. The film thus highlights the miserable situation of homeless disaster victims. It is Sumida who provides these five disaster victims with a place to live and water for bathing, not the Japanese government, local community, charities, or any global nonprofit organizations. At the same time, though a young boy without societal authority, Sumida wields more power over these victims than any other institution or individual because he helps them survive. We see here that disasters enforce social class and affirm hierarchical structures, but also create opportunities to disrupt them.Footnote 9

These five adults are well aware of the power dynamics established by the disaster, displaying submissive and servile attitudes toward those around them in order to survive. Meanwhile, the institutions that possess the resources to assist them, such as the government, local communities, and charitable organizations, either deliberately refrain from intervening or are ineffective in their response, thereby consolidating their authority through inaction. This withholding of aid constitutes a distinct form and tactic of power. Despite the urgent need for public intervention, government-led recovery frameworks squeeze citizens into narrow emotional norms such as kizuna and gaman. These emotional tactics effectively prevent criticism or opposition by compelling victims to endure their pain secretly. These two terms, along with ganbare, served as idealized values during the national recovery process after the triple disaster of 3/11 (Morris-Suzuki Reference Morris-Suzuki2017: 79–83; Mihic Reference Mihic2020: 12–16). First, gaman is understood as a traditional emotional norm that values restraint and patience, particularly in Japanese society. It often acts as an unspoken control mechanism that suppresses an individual’s emotional expression while maintaining order. In The Power of Gaman, T.R. Reid connects the Japanese approach to disaster recovery with the notion of gaman, emphasizing their quiet determination, long-term planning, and stoic commitment to rebuilding (Reference Reid2011: 28).

The term kizuna, which refers to the connections or bonds between people, describes the extraordinary collaborative efforts of the Japanese people, offered as a way to understand the Tōhoku people’s sense of “stoicism, resilience, and law-abiding behavior” (Tipton Reference Tipton2016: 260). Julian Littler (Reference Littler2019) explores how this term functions in Japanese society, defining it as “the idea that individuals should show patience and perseverance when facing unexpected or difficult situations, and by doing so maintain harmonious social ties.” This kind of simplistic outside observation of Japanese people and their culture has prevailed following the disaster, starting with the literary scholar, Donald Keene, who admired the Japanese for their patient response to the disaster so much that he decided to live as a Japanese citizen. “[…] I was impressed that Japanese people were calm even after the earthquake, tsunami, and the nuclear accident […] I want to die as a Japanese person” (cited in Yabuuchi Reference Yabuuchi2019). This bold declaration from a globally recognized American scholar resonates with Sumida’s teacher’s pride in the Japanese people who, in his mind, are inherently stoic and strong in the face of disaster.

In this context, Himizu elucidates how gaman and kizuna, as national community values, obscured inequality and exclusion following the disaster. The character who most clearly demonstrates the emptiness of kizuna is Sumida’s mother (played by Watanabe Makiko). She perceives the disaster victims who fled Fukushima as “others” whom she wishes never to encounter. When Sumida gets into an argument with his mother’s boyfriend, the considerate disaster victims Kenichi and Maa-kun are concerned, asking, “What’s going on? Are you okay?” As they approach and try to help Sumida, his mother glares at them and shouts, “Go away!”

She asks Sumida in an irritable voice, “Do you let them use our bath? You know, do you let those people use our bath when I’m not here? They might be radioactive. No way.” Her fear of radiation is, in some ways, a very common reaction. She is indifferent to the scientific fact that radiation is not a transmissible virus. This misconception transforms the boathouse into a heterotopia of deviation. The fear of contamination fosters a binary logic that categorizes bodies and spaces as either “pure” or “polluted,” thereby reshaping social relationships and legitimizing the physical segregation of disaster victims from the mainstream community. In this way, Sumida’s mother explicitly excludes the disaster victims from the ideal of kizuna by turning away from them, despite their being her neighbors. In the final scene of this sequence, the mother completely abandons Sumida, leaving only a little money and a note that ironically contains the word ganbare, the very principle of endurance that, as discussed earlier, serves to mask state neglect while placing the burden of resilience on individuals. Her abandonment, coupled with this hollow encouragement, exemplifies how ganbare functions as a substitute for genuine support or institutional responsibility. For her, the boat shop is a heterotopia that is not a refuge, but rather a place that isolates and excludes her from flourishing society, a radioactive space in which she cannot bear to linger.

Her suspicion that these victims are radioactive is another example of the scapegoating mechanism (Girard Reference Girard1986, Reference Girard1987). Indeed, people residing in areas affected by radiation contamination have been subjected to resentment and hostility in the aftermath of the triple disaster, including intolerance and prejudice against people from the Tōhoku region and its surrounding areas. Moreover, everyday social discrimination, and the numerous lawsuits filed by displaced people against the government, attest to the state’s abandonment of many disaster victims (Jobin Reference Jobin2020).

The film increases the tension within the heterotopia by presenting radioactivity as a powerful invisible divider in three ways. Firstly, the interior of Sumida’s house, which was swept away by the catastrophe, is rearranged according to the social class assigned by radioactivity. Secondly, in this rearranged place, the conventional rhetoric of Japan’s unique values cannot function as a source of hope or comfort. And thirdly, the extreme fear of invisible radioactivity, which the human eye can never discern, generates hostility rather than sympathy. Despite his mother’s concerns, Sumida embodies the original concept of kizuna by providing the disaster victims with hospitality. However, for Sumida, kizuna is not a universal concept, but operates conditionally only in a certain kind of heterotopia—a heterotopia of compensation (that is, the space inhabited by the disaster victims). For instance, Chazawa makes consistent efforts to establish a bond with Sumida through kindness and care, yet Sumida responds with violence, rejecting her kizuna and shunning emotionally intimate relationships. On the other hand, although Chazawa, like Sumida, is a victim of severe domestic violence, she contrasts with him by longing for an emotional connection with others. Sumida’s violence against Chazawa primarily occurs in his house, which as a heterotopia of deviation, is constantly reproducing and exacerbating violence toward others. Despite the clearly violent nature of their interactions, some critics downplay the significance of gendered power in Himizu. For example, Kawamura Yūtarō (2012) considers the violence inflicted on Sumida by his father and loan sharks to be serious. However, he compares the ongoing violence between Chazawa and Sumida to be “playful roughhousing between small animals (小動物のジャレ合いに近い, shōdōbutsu no jareai ni chikai)” or “a sign of sexual immaturity (性的未熟を感じてしまう, seiteki mijuku o kanjite shimau),” trivializing and romanticizing Sumida’s violence (2012: 74). By overlooking Chazawa’s suffering, we as critics risk perpetuating the permissibility of gendered violence in contemporary society.

In fact, contrary to the romantic claims of Kawamura, perhaps the only moment when Sumida accepts Chazawa’s outreach is near the end of the film, when she urges him to confess to the patricide. However, the kizuna between Sumida and Chazawa never evolves into a reciprocal relationship. Nevertheless, Chazawa practices gaman by not leaving Sumida’s side, and the disaster victims exhibit the same attitude by silently enduring the insults directed at them by Sumida’s mother. For all of them, gaman serves more as a survival strategy than an ethical virtue: Chazawa, abandoned by her parents, has nowhere to go to except Sumida’s house, and nor do the five disaster victims. Therefore, their survival will not be guaranteed anywhere if they lack endurance. Eventually, Sumida’s mother abandons this house, while the connection between Sumida and the disaster victims endures. However, the fact that this relationship is maintained solely by Sumida’s will exposes the inherent fragility of emotional arrangements built on idealized norms.

Conclusion

This article examined the classroom and house in Himizu through Michel Foucault’s concept of heterotopia. These cinematic places demonstrate that the Japanese social norms of wa, sontaku, kizuna, and gaman do not necessarily function as communal values, but at times operate as mechanisms of oppression and exclusion. Here, the triple disaster of 3/11 is the condition that enables heterotopia to function, the driving force that established the spatial opposition structure, and the key mechanism that reveals the dynamics of integration and exclusion. The classroom, which functions as a tool for the reproduction of national ideology, forces the internalization of Japanese norms and emotional order, and the house thoroughly isolates Sumida through repeated violence. At the same time, the house is also a locus of temporary solidarity, but such bonds do not overcome the power structure that dominates the space. In this way, the classroom and the house function as spaces where different operations of power intersect with oppression and violence. As a result, Sumida becomes the agent of violence victimizing Chazawa. In conclusion, this analysis urges us to perceive post-disaster life not as a teleological recovery narrative aimed at a specific goal, but as a struggle to sustain everyday life. Here, Sumida’s declaration that “Ordinary is the best” is a desperate demand for society to guarantee the minimum rights necessary to survive simply ordinarily, rather than imposing grand narratives of heroic overcoming or communal sacrifice on individuals. By doing this, the film highlights that recognizing the marginalized voices drowned out by the dominant narrative of national recovery is the first step toward authentic solidarity and real national recovery.

Acknowledgements

I am profoundly grateful to Professor Rhee Joo-yeon at Penn State University for her invaluable guidance and constructive feedback, which significantly shaped the development of this manuscript. I would also like to thank Joe Venable and Brian Bergstrom for their insightful comments. My sincere appreciation goes to the two anonymous reviewers, whose rigorous and thoughtful feedback substantially strengthened this work. Finally, I appreciate the generous support of the journal editor, Professor Tristan R. Grunow, throughout the revision process.

Competing interests

This manuscript is based on research undertaken for the author’s doctoral dissertation. However, although both works address the same film, they approach the material from distinct perspectives. The author declares no conflicts of interest and received no funding for this work.

Mi-Young Gu is a PhD candidate at the Graduate School of International Culture and Communication Studies, Waseda University. Her research investigates how contemporary Korean and Japanese cinema portray state, ideological, and capitalist violence, framing these dynamics as dystopian landscapes. Before pursuing academia, she worked for over a decade as a recording engineer in Korea’s music industry. Future research examines visual and sound technologies in Korean and Japanese contexts.