Introduction

Major depressive disorder (MDD) is the leading cause of disability among psychiatric disorders (Vos et al., Reference Vos, Lim, Abbafati, Abbas, Abbasi, Abbasifard, Abbasi-Kangevari, Abbastabar, Abd-Allah, Abdelalim, Abdollahi, Abdollahpour, Abolhassani, Aboyans, Abrams, Abreu, Abrigo, Abu-Raddad, Abushouk and Murray2020). MDD affects cognition, motivation, emotion regulation, and motor functions, along with neurovegetative symptoms (American Psychiatric Association, 2022). A core symptom is anhedonia – the reduced ability or lack of reactivity to pleasurable stimuli (Der-Avakian & Markou, Reference Der-Avakian and Markou2012) – which is linked to greater depression severity (Spijker, Bijl, De Graaf, & Nolen, Reference Spijker, Bijl, De Graaf and Nolen2001), poorer responses to psychotherapeutic and pharmacological treatments (Uher et al., Reference Uher, Perlis, Henigsberg, Zobel, Rietschel, Mors, Hauser, Dernovsek, Souery, Bajs, Maier, Aitchison, Farmer and McGuffin2012), and delayed remission (McMakin et al., Reference McMakin, Olino, Porta, Dietz, Emslie, Clarke, Wagner, Asarnow, Ryan, Birmaher, Shamseddeen, Mayes, Kennard, Spirito, Keller, Lynch, Dickerson and Brent2012).

Mounting evidence links depression and anhedonia to disruptions in reward functioning (e.g. Der-Avakian & Markou, Reference Der-Avakian and Markou2012; Pizzagalli, Reference Pizzagalli2014, Reference Pizzagalli2022). Studies using the Probabilistic Reward Task (PRT), a signal-detection task assessing individuals’ ability to respond to and learn from rewards, show that individuals with depression exhibit reduced response bias toward the most frequently rewarded stimulus (Pizzagalli, Iosifescu, Hallett, Ratner, & Fava, Reference Pizzagalli, Iosifescu, Hallett, Ratner and Fava2008; Pizzagalli, Jahn, & O’Shea, Reference Pizzagalli, Jahn and O’Shea2005). This diminished reward response correlates with greater anhedonia severity (Bogdan & Pizzagalli, Reference Bogdan and Pizzagalli2006) and is mirrored by a larger feedback-related negativity (FRN, Santesso et al., Reference Santesso, Dillon, Birk, Holmes, Goetz, Bogdan and Pizzagalli2008). This event-related potential (ERP) component, typically observed ~200–300 ms post-feedback at fronto-central electrodes (Miltner, Braun, & Coles, Reference Miltner, Braun and Coles1997), has been increasingly reconceptualized as feedback-related positivity (FRP). This shift in reconceptualization reflects evidence that the apparent ‘negativity’ actually mirrors a diminished reward-related positivity in response to unfavorable outcomes (Kujawa, Smith, Luhmann, & Hajcak, Reference Kujawa, Smith, Luhmann and Hajcak2013; Proudfit, Reference Proudfit2015; Weinberg, Riesel, & Proudfit, Reference Weinberg, Riesel and Proudfit2014). Accordingly, in the present study, we refer to the variation in FRN amplitude as the FRP, consistent with prior depression research (e.g. Bogdan, Santesso, Fagerness, Perlis, & Pizzagalli, Reference Bogdan, Santesso, Fagerness, Perlis and Pizzagalli2011; Whitton et al., Reference Whitton, Kakani, Foti, Van’t Veer, Haile, Crowley and Pizzagalli2016). The FRP originates from the dorsal anterior cingulate cortex and is associated with mesocorticolimbic BOLD activity (Carlson, Foti, Mujica-Parodi, Harmon-Jones, & Hajcak, Reference Carlson, Foti, Mujica-Parodi, Harmon-Jones and Hajcak2011) and dopamine signaling (Holroyd & Coles, Reference Holroyd and Coles2002; Santesso et al., Reference Santesso, Evins, Frank, Schetter, Bogdan and Pizzagalli2009). In healthy individuals, the largest reward learning on the PRT corresponds to larger FRP (i.e. less negative FRN) to rich reward feedback (Santesso et al., Reference Santesso, Dillon, Birk, Holmes, Goetz, Bogdan and Pizzagalli2008).

Notably, reward deficits in individuals with MDD are often viewed as trait-like characteristics (Kuhn et al., Reference Kuhn, Palermo, Pagnier, Blank, Steinberger, Long, Nowicki, Cooper, Treadway, Frank and Pizzagalli2025; Pechtel, Dutra, Goetz, & Pizzagalli, Reference Pechtel, Dutra, Goetz and Pizzagalli2013; Weinberg & Shankman, Reference Weinberg and Shankman2017). However, there is growing evidence that these deficits exhibit state sensitivity, fluctuating in response to contextual factors such as stress (Bogdan et al., Reference Bogdan, Santesso, Fagerness, Perlis and Pizzagalli2011; Bogdan & Pizzagalli, Reference Bogdan and Pizzagalli2006) and cognitive-affective processes such as rumination (Schettino et al., Reference Schettino, Ghezzi, Ang, Duda, Fagioli, Mennin, Pizzagalli and Ottaviani2021).

Rumination is another central feature of depressive symptomatology contributing to the onset, maintenance, and poor prognosis of MDD and has been defined as a state of repetitive and passive focus on depressive symptoms and their possible causes and consequences (Nolen-Hoeksema, Wisco, & Lyubomirsky, Reference Nolen-Hoeksema, Wisco and Lyubomirsky2008). Recently, rumination and related processes (e.g. worry, trauma-related memories) have been conceptualized as sharing core dimensions, including intrusiveness, repetitiveness, and uncontrollability. These features are collectively termed repetitive negative thinking (RNT, Ehring & Watkins, Reference Ehring and Watkins2008). Evidence suggests that RNT’s transdiagnostic dimensions may be more predictive of depression and anxiety disorders than disorder-specific features (Spinhoven, Drost, van Hemert, & Penninx, Reference Spinhoven, Drost, van Hemert and Penninx2015; Spinhoven, van Hemert, & Penninx, Reference Spinhoven, van Hemert and Penninx2018).

RNT is thought to prolong the cognitive representation of environmental stressors and their associated physiological stress responses (Brosschot, Gerin, & Thayer, Reference Brosschot, Gerin and Thayer2006; Ottaviani et al., Reference Ottaviani, Thayer, Verkuil, Lonigro, Medea, Couyoumdjian and Brosschot2016). Notably, blunted reward responses may stem from dysfunctional stress-reward systems’ interactions (Pizzagalli, Reference Pizzagalli2014) via medial prefrontal cortex dopamine release and increased ventral tegmental area excitability (Cabib, Ventura, & Puglisi-Allegra, Reference Cabib, Ventura and Puglisi-Allegra2002; Cao et al., Reference Cao, Covington, Friedman, Wilkinson, Walsh, Cooper, Nestler and Han2010; Lowes et al., Reference Lowes, Chamberlin, Kretsge, Holt, Abbas, Park, Yusufova, Bretton, Firdous, Enikolopov, Gordon and Harris2021), ultimately leading to reduced functionality in mesolimbic striatal regions. Human studies have linked trait rumination to heightened mesocortical activity (Erdman et al., Reference Erdman, Abend, Jalon, Artzi, Gazit, Avirame, Ais, Levokovitz, Gilboa-Schechtman, Hendler and Harel2020; Lin et al., Reference Lin, Liu, Qiu, Yang, Yang, Tian, Wang, Zhang, Bai and Xu2024), yet the state-dependent effects of RNT on reward processing are understudied.

It is plausible that RNT disrupts behavior by interfering with reward system functionality. However, it remains unclear whether core deficits in anhedonia (i.e. reward functioning) and rumination are mechanistically related in individuals with depressive symptomatology. Whitmer, Frank, and Gotlib (Reference Whitmer, Frank and Gotlib2012) found that rumination increased sensitivity to reward probabilities in both depressed and nondepressed individuals. Conversely, Hitchcock et al. (Reference Hitchcock, Forman, Rothstein, Zhang, Kounios, Niv and Sims2022) reported reduced reinforcement learning performance during state rumination, independent of any concomitant reduction in attentional span. Other studies have found limited evidence of a direct pathophysiological relationship between state rumination and anhedonia-related reward deficits (Forthman et al., Reference Forthman, Kuplicki, Yeh, Khalsa, Paulus and Guinjoan2023; Park et al., Reference Park, Kirlic, Kuplicki, Paulus, Guinjoan, Aupperle, Bodurka, Khalsa, Savitz, Stewart and Victor2022; Schettino et al., Reference Schettino, Ghezzi, Ang, Duda, Fagioli, Mennin, Pizzagalli and Ottaviani2021).

Given the contrasting evidence, the present study employed a randomized controlled within-subjects multilevel design to examine the experimental effects of inducing state RNT on behavioral and electrophysiological reward-related markers in individuals with varying depressive symptomatology severity. Specifically, the effects of an experimentally induced RNT condition on reward response bias and the concomitant modulation of FRP amplitude were compared to those of an active control condition. We further investigated whether the RNT condition affected reward processing as a function of depressive symptom severity, focusing on the development of reward response bias and associated FRP amplitude to reward feedback. Finally, we assessed whether the RNT condition specifically modulated FRP amplitude to reward feedback without affecting other ERP components (i.e. N100 and P300).

Materials and methods

Participants

Participants are undergraduate students from Sapienza University of Rome. The sample included participants with varying severity of depression based on their scores on the Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II, Beck, Steer, & Brown, Reference Beck, Steer and Brown1996). Based on clinical cut-off scores for depression, participants scoring below 10 on the BDI-II were assigned to the Low DEP group (minimal depressive symptoms), while those scoring above 20 were assigned to the High DEP group (i.e. moderate-to-severe depressive symptoms) (Beck et al., Reference Beck, Steer and Brown1996). Participants with BDI-II scores between 10 and 19 (mild depressive symptoms) were excluded. See Supplement S1 for exclusion criteria and power analyses. The study received ethical approval from the Institutional Review Board of the Department of Psychology (Ref. N. 740/2020), Sapienza University of Rome.

Clinical scales

A set of questionnaires assessing sociodemographic (i.e. sex assigned at birth, age, ethnic identification, and level of education); lifestyle; and clinical information (i.e. alcohol and nicotine consumption, physical activity, and medications use) were administered. Besides the BDI-II, participants completed the Snaith–Hamilton Pleasure Scale (Snaith et al., Reference Snaith, Hamilton, Morley, Humayan, Hargreaves and Trigwell1995); the Ruminative Response Scale (RRS, Nolen-Hoeksema, Reference Nolen-Hoeksema1991); the Perseverative Thinking Questionnaire (PTQ, Ehring et al., Reference Ehring, Zetsche, Weidacker, Wahl, Schönfeld and Ehlers2011); and the Penn State Worry Questionnaire (Meyer, Miller, Metzger, & Borkovec, Reference Meyer, Miller, Metzger and Borkovec1990) (Supplementary S2).

Experimental design and procedure

The study used a randomized, controlled, within-subject design (Figure 1A). Participants were instructed to avoid consuming coffee or alcohol 1 hour prior to their experimental session. A 64-channel electroencephalography (EEG) cap was then applied to record electrophysiological activity from the scalp. Participants underwent, in random order, a 2-min experimental induction condition to elicit RNT and a 2-min active control condition where they described neutral pictures (see below). After each condition, participants performed the PRT, which lasted 21 min each. The entire experiment lasted 90 min, with a 15-min break in between sessions during which they were only allowed to drink water. Participants were then debriefed and compensated with the money they won during the PRT.

Figure 1. Experimental timeline of the study design (A). Participants underwent both the experimental and control conditions in a randomized order on the same day, with a 15-min break between sessions, during which they were only allowed to drink water. During the experimental condition, participants underwent the repetitive negative thinking induction, while during the control condition they underwent a corresponding active control induction. Visual analogue scales (VASs) were administered before, after, and at the end of each condition. EEG was registered from the scalp throughout the experiment. Feedback-related positivity (FRP) was detected after the reward feedback presentation to the rich stimulus, while N100 and P300 were detected after the presentation of the rich stimulus in the probabilistic reward task (PRT, B). The PRT required participants to respond to two different stimuli (long or short mouth or nose) presented on the screen, by pressing ‘m’ or ‘v’ buttons on the keyboard. Responses were followed by either a blank screen (non-reinforced trials) or by visual feedback indicating that they had won 20 cents (reinforced trials). One of the two stimuli was rewarded 3:1 time more frequently (i.e. the rich stimulus) than the other (i.e. the lean stimulus). The primary behavioral outcome variable in the PRT is the reward response bias, which is a signal detection-based measure of systematic preference to choose the most frequently rewarded stimulus.

RNT induction paradigm and control condition

Participants underwent a validated 2-min experimental induction condition aimed at eliciting RNT (e.g. Makovac et al., Reference Makovac, Meeten, Watson, Herman, Garfinkel, Critchley and Ottaviani2016) and a 2-min active control condition where they described a series of affectively neutral pictures. For the RNT condition, participants received the following instruction: ‘Next, I would ask you to recall an episode that has happened in the past or something that may happen in the future; an event or an image that often intrudes in your mind repeatedly without you wanting it to. Please, take as much time as you need to recall such an episode in detail, for example considering its possible causes, consequences, and your feelings about it. Press the button whenever you are ready. Now, I ask you to tell me about that episode or image’ (Supplementary Table S2 for qualitative descriptions of the thematic content generated during the induction).

For the active control condition, participants were instructed as follows: ‘Next, I would ask you to focus on the pictures that will be presented on the screen. Please take as much time as you need to focus on the pictures in detail, for example, on aspects such as shape, color, and the arrangement of flowers or trees within the picture. Press the button whenever you are ready. Now, I ask you to describe these pictures’ (Supplementary S3).

Visual Analogue Scales

The content-independent features of RNT (adapted from the PTQ) were assessed in both conditions by the following four separated 100-point visual analogue scales (VASs): ‘Right now, how much are you: (1) distracted by your thoughts (i.e. past memories, future worries, personal problems)? (distraction); (2) having these thoughts go through your mind repeatedly? (repetitiveness)’; (3) having these thoughts come to mind without wanting them to? (intrusiveness); (4) stuck on these issues and unable to move on? (being stuck).’ These VASs were administered at rest, before and after the experimental/control condition and at the end of the PRT/EEG sessions (Figure 1A).

Probabilistic Reward Task

The PRT assesses participants’ ability to adjust their behavior based on rewards, providing objective measures of reward learning (e.g. Pizzagalli et al., Reference Pizzagalli, Jahn and O’Shea2005).To minimize carry-over effects, two different versions of the PRT (mouth and nose) were administered before and after the experimental manipulation. Each run included three blocks of 100 trials. On each trial (Figure 1B), participants decided whether a long or short stimulus (mouth/nose) was presented on a cartoon face by pressing the ‘m’ or ‘v’ button on the keyboard. In reinforced trials, correct responses triggered visual feedback indicating a 20-cent reward; in nonreinforced trials, only a blank screen appeared. Unbeknownst to the participant, one stimulus (‘rich’) was rewarded three times more frequently than the other (‘lean’). The stimulus (mouth/nose) that was rewarded more frequently, the keys pressed for the short or the long mouth/nose, and the total rewards received were counterbalanced between and within participants, resulting in eight different combinations (Supplementary Table S1). The primary behavioral outcome variable was response bias, a signal detection-based measure of systematic preference for the most frequently rewarded stimulus (Supplementary S4). Control analyses included discriminability (Supplementary S5), accuracy, and reaction time (Supplementary S6).

EEG acquisition

Continuous EEG was recorded (band-pass filter: 0.05–100 Hz; sampling rate: 500 Hz) using a BrainVision actiCHamp System (BrainProducts GmbH, Germany) with a set of 64 Ag/AgCl electrodes placed according to the 10/20 system and referenced to an electrode placed at the frontocentral (FCz) site with a cephalic (forehead) location as the ground. The vertical electrooculogram was recorded from the right eye using an infraorbital electrode. Horizontal eye movements were derived from electrodes near the outer canthi of the eyes. Electrode impedances were maintained below 5 kΩ.

EEG analysis

Data were processed using Brain Vision Analyzer (Brain Products GmbH, Germany). A band-pass filter (0.1–40 Hz) was applied offline using an eighth-order Butterworth infinite-impulse response filter to decrease noise. All electrodes were referenced to the FCz electrode during data acquisition and rereferenced offline to the average of electrodes. Spherical spline topographic interpolation was used when necessary to handle noisy or missing channels, and a semiautomatic artifact-rejection method was used to remove muscle activity or other artifacts (Perrin, Pernier, Bertnard, Giard, & Echallier, Reference Perrin, Pernier, Bertnard, Giard and Echallier1987). An ocular independent component analysis was performed to eliminate artifacts related to eye movements, such as blinks and saccades. Components representing these ocular artifacts were identified and removed. EEG epochs were extracted beginning 200 ms before and ending 800 ms after the reward feedback presentation to the rich stimulus (i.e. the stimulus associated with the most frequent reward) on correct trials during Blocks 1 and 3 following previous works (e.g. Bogdan et al., Reference Bogdan, Santesso, Fagerness, Perlis and Pizzagalli2011; Whitton et al., Reference Whitton, Kakani, Foti, Van’t Veer, Haile, Crowley and Pizzagalli2016). The FRP was scored manually for each subject at each site using a prestimulus baseline between −200 and 0 ms. The FRP was defined as the maximal peak occurring 200–400 ms after reward feedback presentation at fronto-central midline scalp sites, namely frontocentral (FCz), frontal (Fz), and central (Cz), where the FRP amplitude is typically largest (Gehring & Willoughby, Reference Gehring and Willoughby2002; Sambrook & Goslin, Reference Sambrook and Goslin2015). Based on previous findings (Pechtel et al., Reference Pechtel, Dutra, Goetz and Pizzagalli2013; Santesso et al., Reference Santesso, Dillon, Birk, Holmes, Goetz, Bogdan and Pizzagalli2008), we did not expect the induction to differentially affect FRP amplitudes to reward feedback across the three scalp sites. To determine whether the electrophysiological effects of RNT induction were specifically related to reward-related information processing, the N100 and P300 amplitudes time-locked to the rich stimuli were also analyzed (Supplementary S7). These ERPs inform on perceptual and attention allocation stages of information processing, respectively.

Data analysis

Independent sample t-tests and chi-square analysis were performed to rule out preexisting group differences and potential confounders (i.e. body mass index, age, smoking). Preliminary checks confirmed that the assumptions of normality, linearity, and homogeneity of variances were met.

To evaluate the effectiveness of the RNT induction, mixed-model ANOVAs were conducted with Condition (RNT, Control) as a within-subjects factor, Group (High vs. Low DEP) as a between-subjects factor, and ΔVAS scores (postinduction minus preinduction) as the dependent variables.

PRT data were quality checked per established criteria (Pizzagalli, Jahn, & O’Shea Reference Pizzagalli, Jahn and O’Shea2005). The effect of the RNT induction (vs. control induction condition) on response bias was analyzed using mixed ANOVA with Condition (RNT, Control); Block (1–3) as within-subject factors; and Group (High, Low DEP) as between-subjects factor.

To examine the effects of the RNT induction on the FRP amplitude, a mixed ANOVA was conducted with Condition (RNT, Control) and Site (Fz, FCz, Cz) as within-subjects factors and Group (High vs. Low DEP) as between-subjects factor. Consistent with previous work, this primary analysis was done on the resulting FRP amplitude at Block 3 following PRT reinforcement schedule (Bogdan et al., Reference Bogdan, Santesso, Fagerness, Perlis and Pizzagalli2011; Santesso et al., Reference Santesso, Dillon, Birk, Holmes, Goetz, Bogdan and Pizzagalli2008). In addition, a secondary analysis tested FRP changes over time using separate mixed ANOVAs for each site with Condition (RNT, Control) and Learning Phase (early: Block 1, late: Block 3) as within-subjects factor and Group (High vs. Low DEP) as between-subjects factor. Simple effects analyses (Bonferroni-corrected) followed significant effects involving Condition. Statistical significance was determined based on 95% confidence intervals (CIs) of the marginal mean differences and corrected-p values.

Spearman’s correlations were used to test for associations between electrophysiological, behavioral, and subjective responses under the RNT induction.

Results

Data from one participant did not pass the quality check for the PRT analyses and was excluded, resulting in a final sample of 61 participants. Additionally, seven participants had poor quality EEG data due to external noise and electrode artifacts, so the EEG analyses were conducted on a subsample of 54 subjects.

Differences in clinical and sociodemographic variables between groups at baseline

Table 1 shows the mean and standard deviations for clinical and sociodemographic variables, as well as subjective levels of RNT at baseline. The High DEP group differed from the Low DEP group in sex distribution; thus, all subsequent analyses controlled for sex assigned at birth. The High DEP group reported significantly higher scores on the (1) brooding and depression subscales of the RRS, (2) PTQ, and (3) PSWQ, indicating a higher dispositional tendency to RNT. This pattern was also evident at the state level, as indicated by VAS scores at baseline, with participants in the High DEP group reporting higher levels of distraction, more intrusive, repetitive, and persistent thoughts.

Table 1. Sociodemographic, clinical, and baseline characteristic of the sample

Note: Mean (SD) ± standard deviations are reported for all variables; BDI, Beck Depression Inventory; High DEP, individuals characterized by moderate/severe depression according to the Beck Depression Inventory-II; Low DEP, individuals characterized by minimal depression according to the Beck Depression Inventory-II; PSWQ, Penn State Worry Questionnaire; PTQ, Perseverative Thinking Questionnaire; RRS, Ruminative Response Scale; SHAPS, Snaith–Hamilton Pleasure Scale; VAS, Visual Analogue Scales.

Effects of the induction on self-reported measures of RNT in individuals with High and Low DEP

Main effects of Condition emerged for Δ distraction (F(1,55) = 62.20, p < .001, ηp 2 = .51); Δ repetitiveness (F(1,53) = 102.69, p < .001, ηp 2 = .65); Δ intrusiveness (F(1,53) = 56.64, p < .001, ηp 2 = .51), and Δ stuck (F(1,49) = 56.62, p < .001, ηp 2 = .53). Both High and Low DEP groups showed increased levels of VAS ratings in the RNT compared to the control condition (mean differencedistraction = 40.32, 95% CI = [30.08, 50.56], p < .001, Figure 2A; mean differencerepetitiveness = 40.54, 95% CI = [32.26, 48.56], p < .001, Figure 2B; mean differenceintrusiveness = 29.50; 95% CI = [21.64, 37.36], p < .001, Figure 2C; mean differencestuck = 31.21, 95% CI = [22.87, 39.54], p < .001, Figure 2D). Ancillary analyses were additionally performed to assess whether group differences between participants with high and low levels of depression could be explained by the type of content generated in response to the RNT induction instructions (Supplementary S11 for full details; see also Supplementary Table S2).

Figure 2. Visual analogue scales (VAS) rating changes for distraction (A), repetitiveness (B), intrusiveness (C), and stuck (D) during repetitive negative thinking and active control conditions in individuals with High versus Low DEP. Note: Error bars denote mean standard errors. High DEP, individuals characterized by moderate/severe depression according to Beck Depression Inventory-II scores, Low DEP, individuals characterized by minimal depression according to Beck Depression Inventory-II scores.

Effects of the induction on PRT performance in individuals with High and Low DEP

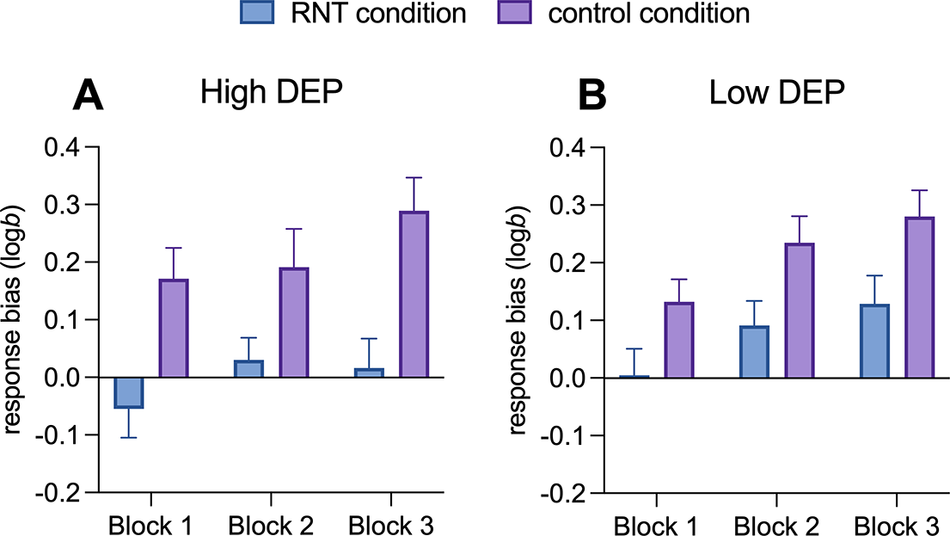

For the effects of the induction on PRT performance, a main effect of Block (F(1,116) = 12.08; p < .001, ηp 2 = .17) and a main effect of Condition (F(1,58) = 14.42; p < .001, ηp 2 = .20) emerged. Simple main effects analyses indicated that response bias increased from Block 1 to Block 3, with Block 1 showing a significantly lower response bias compared to Block 2 (mean difference = −0.08, 95% CI = [−0.15, −0.02], p = .027) and Block 3 (mean difference = −0.12, 95% CI = [−0.18, −0.06], p < .001). With respect to the main effect of Condition, simple main effects analyses indicated that the RNT induction reduced the response bias compared to the control condition (mean difference = −0.16, 95% CI = [−0.25, −0.08], p < .001, Figure 3A and B). No other significant effects emerged (all ps > 0.05).

Figure 3. Development of response bias from Block 1 to Block 3 during repetitive negative thinking versus active control conditions in individuals with high (A) versus low DEP (B). Note: Error bars denote mean standard errors. RNT, repetitive negative thinking; High DEP, individuals characterized by moderate/severe depression according to Beck Depression Inventory-II scores, Low DEP, individuals characterized by minimal depression according to Beck Depression Inventory-II scores.

No effects on discriminability emerged, indicating that response bias effects were not influenced by participants’ ability to discriminate between the big and little mouths or by task difficulty (Supplementary S8 and Figure S1). Higher accuracy and faster reaction times for the rich compared to the lean stimulus were observed only in the control condition (Supplementary S9 and Figure S1).

Effects of the induction on FRP in individuals with High and Low DEP

For the effects of the induction on FRP amplitude to reward feedback during Block 3, a significant Group by Condition interaction was found for FRP (F(1,48) = 6.13; p = .016, ηp 2 = .11). Simple main effects analyses indicated that the interaction effect was due to smaller FRP amplitude (i.e. more negative) for the High DEP in the RNT condition relative to the control condition (mean difference = −1.33, 95% CI = [−2.52, −0.15], p = .027), but not for the Low DEP (mean difference = 0.49, 95% CI = [−1.37, 0.39], p = .269). No other significant effects emerged from this analysis.

For the effects of the induction on the temporal evolution of the FRP to reward feedback, a significant Group by Condition interaction emerged for FCz (F(1,48) = 6.00; p = .018, ηp 2 = .10) and Fz (F(1,48) = 5 59; p = .022, ηp 2 = .10) and marginally for Cz (F(1,48) = 3.22; p = .079, ηp 2 = .07). Simple main effects analyses revealed that the interaction effect was due to smaller FRP amplitude at both sites for the High DEP in the RNT condition relative to the control condition (mean difference FCz = −2.61, 95% CI = [−4.89, −0.32], p = .013, p = .025; mean difference Fz = −1.52, 95% CI = [−2.75, −0.29], p = .016, Figure 4) but not for the Low DEP (mean difference FCz = 0.87, 95% CI = [−0.82, 2.57], p = .306; mean difference Fz = 0.29, 95% CI = [−0.62, 1.21], p = .522). In addition, a marginally significant Condition by Learning Phase interaction emerged for Fz (F(1,48) = 3.90; p = .054, ηp 2 = .07). FRP amplitude was smaller under RNT relative to the control condition in Block 1 (mean difference = −1.01, 95% CI = [−1.91, −0.11], p = .028) but not in Block 3 (mean difference = −0.21, 95% CI = [−1.04, −0.61], p = .604). No other significant effects emerged (all ps > 0.05). No main effects or significant interaction emerged for N100 and P300 (Supplementary S10 and Figure S2).

Figure 4. Topographic maps of the FRP FCz (A) and Fz (B) amplitude waving from 200 to 400 ms after the reward feedback presentation to the rich stimulus on correct trials during Block 3 for the repetitive negative thinking and active control conditions in individuals with High and Low DEP. Histogram of the averaged FRP amplitude in response to reward feedback during Block 3 for the repetitive negative thinking and control conditions in individuals with high (C and E) and low (D and F) DEP. Note: Error bars denote mean standard errors. RNT, repetitive negative thinking; High DEP, individuals characterized by moderate/severe depression according to Beck Depression Inventory-II scores, Low DEP, individuals characterized by minimal depression according to Beck Depression Inventory-II scores.

Correlations between electrophysiological, behavioral, and subjective responses to the PRT after the RNT induction

Correlations were conducted between FRP amplitude at FCz and Fz in Block 3, changes in reward response bias, and the severity of the subjective response to RNT for a total number of five pairwise correlations. Reward response bias change was calculated as the difference between response bias in Blocks 3 and 1, where positive values indicate greater reward learning (e.g. Bogdan & Pizzagalli, Reference Bogdan and Pizzagalli2006). The severity of the subjective response to RNT was computed as the sum of ΔVASs. Significant correlations emerged between FRP amplitude at the Fz site in Block 3 and (i) changes in reward response bias, rho = −0.31, p = .024, Figure 5A) and (ii) the severity of subjective response to RNT induction (rho = −0.28, p = .042, Figure 5B), indicating that a smaller FRP amplitude (i.e. more negative) correlates with a smaller reward response bias and a greater severity of subjective response to RNT. However, these analyses did not survive multiple comparison correction using Benjamini–Hochberg false discovery rate test.

Figure 5. Scatterplots of the correlation between FRP Fz site amplitude and change scores in response bias (A) and severity of the subjective response to the RNT induction (B). Note: Change scores in response bias are calculated as response bias during Block 3 minus response bias during Block 1. The severity of subjective response to the RNT is calculated as the sum of ΔVASs (i.e. change scores on the VAS post-manipulation minus scores premanipulation for each VAS, i.e. distraction, repetitiveness, intrusiveness, and stuck).

Discussion

Anhedonia and rumination are two clinically relevant hallmarks of the depressive phenotype. Although these symptoms may interact to sustain adverse depression-related outcomes (e.g. Rutherford, McDougle, & Joormann, Reference Rutherford, McDougle and Joormann2023), relatively few studies have examined the mechanisms driving this interaction and its effects. This study concurrently examined behavioral and electrophysiological markers of reward learning in individuals with high and low depressive symptom severity during an experimentally induced state of RNT.

The RNT condition, compared to the active control condition, resulted in significantly lower reward-related responses at both behavioral and electrophysiological levels. Behaviorally, participants showed lower response bias toward the more frequently rewarded stimuli, suggesting that engendering RNT blunts reward learning, namely the ability to adjust behavior based on reward. This effect appeared to be particularly pronounced in individuals with high scores on the BDI-II and emerged in the context of no condition-related differences in discriminability (e.g. participants were not simply more distracted in the RNT relative to control condition). These findings are consistent with prior research showing decreased reward response bias in individuals with MDD, linked to their depressive symptoms’ severity, particularly anhedonia (i.e. Pizzagalli et al., Reference Pizzagalli, Jahn and O’Shea2005). Interestingly, in the current study, while all participants developed a response bias during the control condition, this pattern was disrupted under RNT, indicating that reward learning deficits, often seen as trait-like in depression, may also fluctuate in response to RNT patterns such as rumination.

Notably, and as mentioned above, analyses on discriminability scores revealed no significant differences between the RNT and control conditions or between groups, suggesting no global effects of RNT and depression severity on task difficulty. Analyses of accuracy and reaction time revealed increased scores for the rich stimulus type only during the control condition, suggesting that a specific impairment of reward-related behavior may occur during an RNT state.

Given that RNT is hypothesized to trigger and prolong physiological stress responses (e.g. Ottaviani, Reference Ottaviani2018), our findings align with evidence showing that acute stress blunts various aspects of reward processing (Schettino et al., Reference Schettino, Tarmati, Castellano, Gigli, Carnevali, Cabib, Ottaviani and Orsini2024, for a recent meta-analysis). These include reduced reward responsiveness and learning (Bogdan & Pizzagalli, Reference Bogdan and Pizzagalli2006) and other related subdomains, extensively investigated in relation to anhedonia, such as lower effort expenditure (Treadway, Bossaller, Shelton, & Zald, Reference Treadway, Bossaller, Shelton and Zald2012) and diminished motivation for goal-directed behaviors (Grahek, Shenhav, Musslick, Krebs, & Koster, Reference Grahek, Shenhav, Musslick, Krebs and Koster2019). Preclinical studies similarly show that repeated stress induces anhedonic-like behaviors in animals (Schettino et al., Reference Schettino, Tarmati, Castellano, Gigli, Carnevali, Cabib, Ottaviani and Orsini2024, for a meta-analysis). The RNT induction employed here mirrors stress-induction paradigms that evoke physiological activation through recall of personally relevant events (Ottaviani et al., Reference Ottaviani, Thayer, Verkuil, Lonigro, Medea, Couyoumdjian and Brosschot2016, for a meta-analysis). Although subjective response severity to the induction, in terms of these characteristics, was not linked to changes in response bias, it correlated with blunted ERP amplitude to reward feedback, suggesting that RNT’s pathophysiological impact on reward processing may be more evident at neural than behavioral levels.

Critically, electrophysiological analyses revealed smaller FRP to reward feedback presentation during RNT relative to the control condition, particularly in individuals with high BDI-II scores. These effects were not accompanied by changes in N100 and P300 amplitudes, suggesting a specific impact of RNT on cortical responses to reward feedback. Notably, smaller FRP amplitude to reward feedback has been found in individuals with current (Foti, Carlson, Sauder, & Proudfit, Reference Foti, Carlson, Sauder and Proudfit2014) and remitted depression (Whitton et al., Reference Whitton, Kakani, Foti, Van’t Veer, Haile, Crowley and Pizzagalli2016) and correlates with suicidal ideation (Klumpp et al., Reference Klumpp, Bauer, Glazer, Macdonald-Gagnon, Feurer, Duffecy, Medrano, Craske, Phan and Shankman2023). We extended this literature by showing that an RNT state may acutely dampen FRP amplitude in individuals with high severity of depressive symptoms. This negative deflection, reflecting diminished reward-related positivity for reward outcomes that are worse than expected (Proudfit, Reference Proudfit2015; Walsh & Anderson, Reference Walsh and Anderson2012), may indicate a mismatch between reward expectations and outcome in individuals with depression. Supporting this, ecological data have linked momentary RNT with reduced sensitivity to reward despite intact motivation to pursue them (Schettino et al., Reference Schettino, Ghezzi, Ang, Duda, Fagioli, Mennin, Pizzagalli and Ottaviani2021). Similarly, individuals with MDD show heightened anticipatory yet blunted consummatory reward network responses, potentially driven by rumination (Dichter, Kozink, McClernon, & Smoski, Reference Dichter, Kozink, McClernon and Smoski2012). In this regard, smaller variations in FRP amplitude have been previously linked to reduced activation within the reward brain network, particularly in the ventral striatum, anterior cingulate cortex, and midfrontal cortex (Becker, Nitsch, Miltner, & Straube, Reference Becker, Nitsch, Miltner and Straube2014; Carlson et al., Reference Carlson, Foti, Mujica-Parodi, Harmon-Jones and Hajcak2011). Additionally, FRP amplitude (and underlying midfrontal activation) appeared responsive to pharmacologic manipulation hypothesized to reduce phasic striatal dopaminergic responses (Santesso et al., Reference Santesso, Evins, Frank, Schetter, Bogdan and Pizzagalli2009). Taken together, our findings indicate that state-level RNT can transiently worsen neural reward deficits typically considered trait-like in MDD, suggesting a dynamic interplay between cognitive states and enduring vulnerabilities. However, it remains unclear whether these observed deficits in reward learning are a direct consequence of the RNT interference within the neural reward systems, or if, alternatively, rumination primarily amplifies preexisting deficits characteristic of MDD.

The present findings warrant careful consideration for several reasons. First, contrary to expectations, no group differences in response bias emerged during the control condition, despite higher depressive symptoms in the High DEP group. One possibility is that the control induction unexpectedly enhanced positive affect or behavioral activation in this group. The control condition was designed to isolate the specific features of RNT by controlling for other potentially confounding factors, such as a general state of physiological activation or increased memory load. Notably, ancillary analyses indicated that individuals with depressive symptoms tended to engage in RNT at a more abstract level of construal compared to those without depressive symptoms. However, we lack information on potential group differences in the control condition, which may have been influenced by individual variability in visual imagery ability. Future studies should therefore incorporate qualitative assessments of participants’ subjective experiences during both RNT and control inductions to better characterize group-related differences in the cognitive and experiential processes underpinning RNT effects on reward processing. Second, there was a disproportionate number of male and female participants in the High and Low DEP groups, with fewer male participants in the High DEP group. While such gender differences could have influenced the results, this imbalance is commonly encountered in depression studies (e.g. Li, Zhang, Cai, et al., Reference Li, Zhang, Cai, Zheng, Pang and Lou2023). Importantly, sex assigned at birth did not emerge as a significant predictor in any of the analyses.

Conclusions

Collectively, these findings suggest that transient cognitive states, such as RNT, may have pathophysiological and state-dependent effects, temporarily worsening or unmasking the reward-processing deficits commonly observed in individuals with MDD. This state sensitivity highlights the potential that targeting RNT could help restore reward processing. Supporting this idea, evidence suggests that behavioral activation or cognitive restructuring – core components of rumination-focused therapy (Watkins et al., Reference Watkins, Mullan, Wingrove, Rimes, Steiner, Bathurst, Eastman and Scott2011) – may not only improve mood but also enhance reward learning and neural responsiveness (Craske, Dunn, Meuret, Rizvi, & Taylor, Reference Craske, Dunn, Meuret, Rizvi and Taylor2024; Dichter et al., Reference Dichter, Felder, Petty, Bizzell, Ernst and Smoski2009; Kryza-Lacombe et al., Reference Kryza-Lacombe, Pearson, Lyubomirsky, Stein, Wiggins and Taylor2021), ultimately help alleviate anhedonia (Webb, Murray, Tierney, Forbes, & Pizzagalli, Reference Webb, Murray, Tierney, Forbes and Pizzagalli2023). These findings also support the development of dynamic or momentary interventions (e.g. mobile health tools or ecological momentary interventions) that monitor RNT (Funk, Kopf-Beck, Watkins, & Ehring, Reference Funk, Kopf-Beck, Watkins and Ehring2023) and deliver real-time strategies to disrupt it before it cascades into deeper reward dysregulation. Finally, as the FRP effect was more pronounced in individuals with higher BDI scores, this highlights the need for stratified interventions targeting those most vulnerable to reward-blunting effects from cognitive stressors.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at http://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291725102778.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Aishwarya Suresh Dangat, Valeria Gigli, Federica Guidetti, Virginia Spagnuolo, and Viola Tabacco, for their contributions to data collection.

Author contribution

Conceptualization: MS, CO, and SF. Methodology: MS, AM, YSA, CO, DAP, and SF. Formal Analysis: MS, AM, and YSA. Investigation: AM, DB, and IC. Writing – Original Draft preparation: MS and AM. Writing – Review & Editing: MS, YSA, DAP, CO, and SF. Supervision: CO, SF, and DAP. Project Administration: CO and SF.

Funding statement

This study was funded by PRIN 2022 “Targeting attentional biases in depression: A longitudinal multimodal neuroimaging investigation” (Project Code: 2022YLTSWF; CUP: F53D23004910006; PI: SF). MS was partially supported by Sapienza University of Rome (AR223188B3133F0E). DAP was partially supported by National Institute of Mental Health grants 5R37 MH068376. CO was partially supported by PRIN 2022 PNRR “Sex differences in brain-heart pathways: A translational precision-based approach to depression” (Project Code: P202299A2Y; CUP: B53D23030140001).

Competing interests

Over the past 3 years, DAP has received consulting fees from Arrowhead Pharmaceuticals, Boehringer Ingelheim, Compass Pathways, Engrail Therapeutics, Neumora Therapeutics (formerly BlackThorn Therapeutics), Neurocrine Biosciences, Neuroscience Software, Sage Therapeutics, Sama Therapeutics, and Takeda; he has received honoraria from the American Psychological Association, Psychonomic Society and Springer (for editorial work) and from Alkermes; he has received research funding from the BIRD Foundation, Brain and Behavior Research Foundation, Dana Foundation, DARPA, Millennium Pharmaceuticals, NIMH and Wellcome Leap MCPsych; he has received stock options from Compass Pathways, Engrail Therapeutics, Neumora Therapeutics, and Neuroscience Software. No funding from these entities was used to support the current work, and all views expressed are solely those of the authors. The other authors declare no competing financial interests.