Introduction

Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD) is a severe psychiatric condition defined by pronounced impulsivity, instability in interpersonal relationships, self-image, and affect, typically manifesting in early adulthood as quick actions taken without regard for consequences (American Psychiatric Association, 2022). Prevalence estimates range from 0.19% to 2.31% in the general population (Volkert, Gablonski, & Rabung, Reference Volkert, Gablonski and Rabung2018), but BPD is more commonly diagnosed in clinical settings, reaching up to 25% in inpatient populations (Choi-Kain, Sahin, & Traynor, Reference Choi-Kain, Sahin and Traynor2022). Individuals with BPD face significant psychosocial challenges and an increased risk of premature death, largely due to suicide (Temes, Frankenburg, Fitzmaurice, & Zanarini, Reference Temes, Frankenburg, Fitzmaurice and Zanarini2019), with mortality rates as high as 8% to 10% – 50 times greater than in the general population (Leichsenring, Leibing, Kruse, New, & Leweke, Reference Leichsenring, Leibing, Kruse, New and Leweke2011). Impulsivity, a core feature of BPD, plays a critical role in reckless behaviors that can negatively impact overall well-being (Hall & Moran, Reference Hall and Moran2019) and is a well-established predictor of both suicidal behavior and the lethality of suicide attempts (Gvion, Reference Gvion2018). Given that a history of previous nonfatal suicide attempts is a strong risk factor for subsequent suicide mortality (Christiansen & Jensen, Reference Christiansen and Jensen2007; Demesmaeker, Chazard, Hoang, Vaiva, & Amad, Reference Demesmaeker, Chazard, Hoang, Vaiva and Amad2022; Geulayov et al., Reference Geulayov, Kapur, Turnbull, Clements, Waters, Ness, Townsend and Hawton2016; Large, Sharma, Cannon, Ryan, & Nielssen, Reference Large, Sharma, Cannon, Ryan and Nielssen2011), addressing impulsivity is essential for effective prevention strategies. Although impulsivity is a transdiagnostic construct involved in multiple psychiatric disorders (Hook et al., Reference Hook, Grant, Ioannidis, Tiego, Yücel, Wilkinson and Chamberlain2021), including attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD), substance use and addictive disorders, there is still no consensus on its precise definition. One of the most widely accepted definitions is that of Barratt (Reference Barratt1959), who described it as ‘a predisposition to act quickly in response to internal and external stimuli in an unplanned manner, without sufficient forethought or consideration of consequences’ (see Supplementary Material Glossary Box 1). This definition frames impulsivity as a multidimensional trait encompassing cognitive, behavioral, and planning components. Moeller, Barratt, Dougherty, Schmitz, and Swann (Reference Moeller, Barratt, Dougherty, Schmitz and Swann2001) further refined this conceptualization by distinguishing between trait impulsivity – understood as a stable, enduring tendency to behave impulsively – and state impulsivity, which refers to transient, context-dependent expressions of impulsive behavior that can fluctuate based on emotional, cognitive, or physiological factors. While trait impulsivity is typically captured through self-report measures, such as the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale (BIS) (Patton, Stanford, & Barratt, Reference Patton, Stanford and Barratt1995), state impulsivity is assessed using performance-based tasks (Figure 1). Recent neuroimaging studies have identified a common right-lateralized frontoparietal network involved in diverse forms of inhibition – including emotional, behavioral, and memory-related control – while also highlighting task-specific patterns of activation across domains (Depue, Orr, Smolker, Naaz, & Banich, Reference Depue, Orr, Smolker, Naaz and Banich2016). This underscores the importance of distinguishing between inhibitory subtypes, particularly in clinical research.

Figure 1. Schematic representation of the impulsivity construct. Adapted from (Dick et al., Reference Dick, Smith, Olausson, Mitchell, Leeman, O’Malley and Sher2010; Kang et al., Reference Kang, Hernández, Rahman, Voigt and Malvaso2022; López-Caneda et al., Reference López-Caneda, Rodríguez Holguín, Cadaveira, Corral and Doallo2014; Moeller et al., Reference Moeller, Barratt, Dougherty, Schmitz and Swann2001; Sharma et al., Reference Sharma, Markon and Clark2014; Strickland & Johnson, Reference Strickland and Johnson2021; Tiego et al., Reference Tiego, Testa, Bellgrove, Pantelis and Whittle2018; Zhong et al., Reference Zhong, Chen, Zhong, Rezapour, Haghparast, Jiang, Su, Yuan, Robbins, Du and Zhao2025).

Despite the widespread use of the term, some researchers argue that impulsivity lacks coherence as a singular construct, as traits and states grouped under this umbrella – such as response inhibition, delay discounting, and decision-making – are often uncorrelated and no singular neurobehavioral mechanism has been identified to unify these domains (Johnson, Bixter, & Luhmann, Reference Johnson, Bixter and Luhmann2020; Strickland & Johnson, Reference Strickland and Johnson2021). Instead, researchers advocate for distinguishing between key constructs like inattention, response inhibition, impulsive decision-making, and cognitive shifting (Sharma, Markon, & Clark, Reference Sharma, Markon and Clark2014; Strickland & Johnson, Reference Strickland and Johnson2021).

Among these facets, response inhibition – often referred to as inhibitory control (Dick et al., Reference Dick, Smith, Olausson, Mitchell, Leeman, O’Malley and Sher2010) – is one of the most studied components of impulsivity (Bari & Robbins, Reference Bari and Robbins2013). Inhibitory control includes both cognitive and motor components (Kang, Hernández, Rahman, Voigt, & Malvaso, Reference Kang, Hernández, Rahman, Voigt and Malvaso2022; Tiego, Testa, Bellgrove, Pantelis, & Whittle, Reference Tiego, Testa, Bellgrove, Pantelis and Whittle2018). Cognitive inhibitory control can be evaluated through tasks like the Stroop (Reference Stroop1935), Simon (Simon & Rudell, Reference Simon and Rudell1967), Flanker (Eriksen & Eriksen, Reference Eriksen and Eriksen1974), and antisaccade (Munoz & Everling, Reference Munoz and Everling2004), which require resolving interference between competing representations or suppressing irrelevant information. In contrast, the assessment of motor inhibitory control is more straightforward through widely used paradigms such as the Stop-Signal Task (SST) (Logan & Cowan, Reference Logan and Cowan1984) and the Go/No-Go Task (GNGT) (Donders, Reference Donders1969) (Figure. 1). Motor inhibitory control refers to the ability to withhold or suppress inappropriate or irrelevant actions (López-Caneda, Rodríguez Holguín, Cadaveira, Corral, & Doallo, Reference López-Caneda, Rodríguez Holguín, Cadaveira, Corral and Doallo2014) (see Supplementary Material Glossary Box 1). Although tasks measuring cognitive inhibition typically include a motor output (such as pressing a key), they are not designed to isolate the motor inhibition process itself. Rather, they target the suppression of competing representations or responses under conditions of cognitive conflict. In contrast, SST and GNGT are specifically structured to measure the ability to inhibit or cancel a motor response, making them better suited for assessing motor impulsivity in BPD. Motor inhibitory control is often regarded as easier to quantify in experimental settings than cognitive inhibition, as it targets a more constrained behavioral domain. While both cognitive and motor inhibition arise from partially overlapping neural mechanisms (Wessel & Anderson, Reference Wessel and Anderson2023), particularly within the prefrontal cortex, neuroimaging studies have demonstrated that they also rely on distinct neural circuits, depending on the nature of the inhibitory demand (Depue et al., Reference Depue, Orr, Smolker, Naaz and Banich2016; Mirabella & Montalti, Reference Mirabella and Montalti2025, Montalti & Mirabella, Reference Montalti and Mirabella2023). This distinction is critical when evaluating specific forms of impulsivity in clinical populations.

Importantly, motor inhibitory control is particularly relevant in BPD because it is closely linked to reckless and risky behaviors, such as self-harm and aggression. Studies suggest that deficits in motor inhibitory control are associated with heightened impulsive aggression and real-world behavioral dyscontrol (Carpiniello, Lai, Pirarba, Sardu, & Pinna, Reference Carpiniello, Lai, Pirarba, Sardu and Pinna2011; McCloskey et al., Reference McCloskey, New, Siever, Goodman, Koenigsberg, Flory and Coccaro2009). For example, non-suicidal self-injury has been linked to impaired inhibition in the negative emotional condition of the SST (Allen & Hooley, Reference Allen and Hooley2015). Indeed, while impulsive behaviors often arise in emotional contexts or under reward-driven conditions (urgency and sensation-seeking facets of impulsivity) (Billieux, Gay, Rochat, & Van der Linden, Reference Billieux, Gay, Rochat and Van der Linden2010; Whiteside & Lynam, Reference Whiteside and Lynam2001), problematic externalizing behaviors in BPD ultimately manifest as overt motor actions (e.g., intentionally breaking objects, hitting someone, or cutting oneself) (Sansone et al., Reference Sansone and Sansone2013). Therefore, assessing deficits in impulsive action (inhibition of a prepotent motor response), provides a complementary perspective for understanding impulsivity (Bari & Robbins, Reference Bari and Robbins2013; MacKillop et al., Reference MacKillop, Weafer, Gray, Oshri, Palmer and de Wit2016). Compared to impulsive choice, which relates more to risk-taking and gratification delay, motor impulsivity is directly tied to impulsive action, making it a critical component in understanding high-risk behaviors in BPD.

Emerging evidence supports the existence of a domain-general inhibitory control system, underpinned by partially overlapping neural substrates involved in suppressing both motor and cognitive processes, with key roles played by the right dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC), right inferior frontal cortex (IFC), pre-supplementary motor area (SMA), and the subthalamic nucleus (Apšvalka, Ferreira, Schmitz, Rowe, & Anderson, Reference Apšvalka, Ferreira, Schmitz, Rowe and Anderson2022; Castiglione, Wagner, Anderson, & Aron, Reference Castiglione, Wagner, Anderson and Aron2019; Guo, Schmitz, Mur, Ferreira, & Anderson, Reference Guo, Schmitz, Mur, Ferreira and Anderson2018). The rIFC, rDLPFC, and pre-SMA, well-established hubs in motor inhibition tasks such as the SST, also play critical roles in suppressing cognitive processes, as observed in paradigms like the Think-No-Think (TNT) task (Aron, Herz, Brown, Forstmann, & Zaghloul, Reference Aron, Herz, Brown, Forstmann and Zaghloul2016; Castiglione et al., Reference Castiglione, Wagner, Anderson and Aron2019). This shared architecture suggests that motor inhibition may serve as a tractable proxy for broader inhibitory control capacities. Notably, BPD has been associated with both structural and functional alterations in several of these regions, including the rIFC (Jacob et al., Reference Jacob, Zvonik, Kamphausen, Sebastian, Maier, Philipsen, Elst, Lieb and Tüscher2013; Rossi et al., Reference Rossi, Lanfredi, Pievani, Boccardi, Rasser, Thompson, Cavedo, Cotelli, Rosini, Beneduce, Bignotti, Magni, Rillosi, Magnaldi, Cobelli, Rossi and Frisoni2015; Yang, Hu, Zeng, Tan, & Cheng, Reference Yang, Hu, Zeng, Tan and Cheng2016) and pre-SMA (Albert et al., Reference Albert, López-Martín, Arza, Palomares, Hoyos, Carretié, Díaz-Marsá and Carrasco2019), further supporting the relevance of investigating inhibitory control impairments in this population.

Although the SST and GNGT are often used interchangeably, they measure distinct inhibitory processes. The GNGT measures action restraint, requiring participants to respond to frequent ‘Go’ stimuli while withholding responses to infrequent ‘No-Go’ stimuli (Figure. 2). Performance on the GNGT is typically evaluated using two key measures: commission errors (CE) – which reflect incorrect responses to ’no-go’ signals, with higher error rates indicating weaker inhibitory control (Schachar et al., Reference Schachar, Logan, Robaey, Chen, Ickowicz and Barr2007) – and reaction times (RT) on go trials, defined as the time between stimulus onset and the initiation of movement (Benedetti et al., Reference Benedetti, Gavazzi, Giovannelli, Bravi, Giganti, Minciacchi, Mascalchi, Cincotta and Viggiano2020). Longer RTs suggest slower motor response initiation following stimulus presentation. In contrast, the SST assesses action cancellation, requiring participants to suppress an already initiated response when presented with a ‘Stop’ signal (Figure 2). Performance is quantified using the Stop-Signal Reaction Time (SSRT), which is an estimate of the time required to inhibit a prepotent or already initiated motor response following the presentation of a stop signal. A longer SSRT reflects poorer inhibitory control (Verbruggen et al., Reference Verbruggen, Aron, Band, Beste, Bissett, Brockett, Brown, Chamberlain, Chambers, Colonius, Colzato, Corneil, Coxon, Dupuis, Eagle, Garavan, Greenhouse, Heathcote, Huster and Boehler2019). The key difference between the two tasks is the timing of the inhibitory cue relative to the ‘Go’ signal: In the GNGT, a proportion of the stimuli are replaced with a no-go stimulus (0 ms), while in the SST, the go stimulus is always shown first, but may then be followed by a stop stimulus after a short stop signal delay (SSD) (approximately 300 ms) (Raud, Westerhausen, Dooley, & Huster, Reference Raud, Westerhausen, Dooley and Huster2020).

Figure 2. Illustration of the Go/No-Go task (GNGT) and the Stop-Signal Task (SST). The GNGT requires participants to respond to frequent ‘Go’ stimuli while withholding responses to infrequent ‘No-Go’ stimuli. The SST requires participants to suppress an already initiated response when presented with a ‘Stop’ signal. SSD: Stop Signal Delay.

Findings regarding the extent and specific nature of inhibitory control deficits in BPD remain inconsistent. Some studies report significant impairments in tasks like the SST and GNGT among individuals with BPD compared to HCs, highlighting deficits in motor inhibitory control (Sebastian et al., Reference Sebastian, Jung, Krause-Utz, Lieb, Schmahl and Tüscher2014). However, other studies report that motor components may not be uniformly impaired in BPD (Stanford et al., Reference Stanford, Mathias, Dougherty, Lake, Anderson and Patton2009) and suggest that deficits may vary depending on task parameters (Silbersweig et al., Reference Silbersweig, Clarkin, Goldstein, Kernberg, Tuescher, Levy, Brendel, Pan, Beutel, Pavony, Epstein, Lenzenweger, Thomas, Posner and Stern2007). For instance, Yang et al. (Reference Yang, Liu, Peng, Liu, Chu, Zheng, Cao and Yi2021) found that BPD patients showed impaired inhibition in response to angry faces during an emotional SST, but their performance did not differ from that of HCs when responding to neutral faces. These findings suggest that the presence of emotionally salient stimuli may specifically disrupt motor inhibitory control in BPD. Taken together, these discrepancies underscore the need for a comprehensive synthesis and analysis of quantitative findings to better understand the relationship between BPD and motor inhibitory control, particularly as measured by standardized neuropsychological paradigms like the SST and GNGT.

This meta-analysis investigated motor inhibitory control in adults with BPD, focusing on performance in the SST and GNGT. We hypothesized that BPD patients would exhibit significant deficits in motor inhibitory control compared to HCs, which the SST and GNGT could capture.

In light of the variability in the existing literature, we aimed to investigate whether these discrepancies arise from differences in study quality or the validity of the tasks used. Given the potential moderating effects of emotion, sex, and age on inhibitory control, we also explored these factors to better understand the variability in findings. Furthermore, we investigated whether trait impulsivity, as measured by BIS-11 subscales, is linked to performance on inhibitory control tasks (SST and GNGT). We adhered to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (Page et al., Reference Page, McKenzie, Bossuyt, Boutron, Hoffmann, Mulrow, Shamseer, Tetzlaff, Akl, Brennan, Chou, Glanville, Grimshaw, Hróbjartsson, Lalu, Li, Loder, Mayo-Wilson, McDonald and Moher2021) to address this. We pre-registered this meta-analysis in the PROSPERO database (PROSPERO ID: CRD42024570632). The analysis included 37 datasets from 35 articles, providing a comprehensive sample for evaluating motor inhibitory control deficits in BPD patients compared to HCs. Additionally, we performed a thorough quality assessment of the included studies, assessing their overall quality (Kmet, Lee, & Cook, Reference Kmet, Lee and Cook2004) and the validity of the tasks administered (Verbruggen et al., Reference Verbruggen, Aron, Band, Beste, Bissett, Brockett, Brown, Chamberlain, Chambers, Colonius, Colzato, Corneil, Coxon, Dupuis, Eagle, Garavan, Greenhouse, Heathcote, Huster and Boehler2019). This approach enabled us to examine the influence of differing methodological frameworks on motor inhibitory control outcomes and explore their potential connections with clinical measures of impulsivity.

Methods

Eligibility criteria

The criteria for study selection were as follows: 1. Participants were adult patients (18+); 2. Studies included at least one group of patients with BPD according to the DSM criteria (5th edition or earlier) or the ICD criteria (11th edition or earlier) and a healthy control (HC) group. 3. Experimental task: motor inhibitory control performance needed to be assessed using the SST or the GNGT. 4. Outcome measures: For the GNGT, either the reaction time on Go trials or the number of commission errors, and for the SST, the Stop Signal Reaction Time (SSRT) must be reported to calculate standardized mean differences (Cohen’s d). Authors were contacted to provide outcomes of interest if they were not reported. 5. Other criteria: Full-length articles had to be written in English and published or accepted for publication in peer-reviewed journals from 2000 onwards. Conversely, studies were excluded if they met any of the following criteria: 1. Inclusion of only healthy controls (HC) or clinical populations without a BPD group. 2. Samples composed entirely of minors (<18 years old), regardless of diagnosis. 3. Use of atypical SST paradigms (e.g., dual tasks or selective SSTs) or other tasks such as the Conners’ Continuous Performance Test II, which assess cognitive rather than motor inhibitory control. 4. Publication in languages other than English or French. 5. Article not published or accepted in peer-reviewed journals between 2000 and 2025 (e.g., reviews, meta-analyses, posters, comments, book chapters). 6. Duplicate publications. 7. Non-empirical dissertations (e.g., MSc or PhD theses). 8. Animal studies. 9. Lack of required outcome measures of interest (authors were contacted to retrieve missing outcomes, when applicable). 10. Study protocols or articles not in full-length (e.g., abstracts only).

Search strategy

An electronic search was conducted up to November 12, 2024, in the following publication databases: PubMed, Science Direct, Web of Science, and PsycInfo. The first 200 results in Google Scholar were screened to further enhance recall (Bramer, Rethlefsen, Kleijnen, & Franco, Reference Bramer, Rethlefsen, Kleijnen and Franco2017). The syntax used is presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Databases, search terms and references found on November 12, 2024

Study selection

Study selection was conducted independently by two authors (NB and AST) through a two-step process: (1) an initial screening of titles and abstracts based on the previously established inclusion criteria and (2) a thorough review of the full texts of the remaining studies to evaluate their eligibility. In the event of disagreement, studies were reviewed by other team members and discussed until consensus was reached.

Data extraction and outcomes

Data extraction was performed independently by two authors (AST and LMP). For studies with insufficient data for the meta-analysis, the authors were contacted to obtain the missing information. The primary outcomes, reaction time of Go trials or the number of commission errors for the GNGT or the SSRT for the SST, were extracted separately for patients and controls. Key potentially confounding variables, such as age and sex ratio, were also extracted and systematically tabulated for each study. Two more raters (NB and WV) performed a quality check to ensure data extraction accuracy. The team reviewed disagreements until a consensus was reached.

Quality and task validity assessments

The quality of the included studies was assessed using the Standard Quality Assessment Criteria for Evaluating Primary Research Papers (Kmet et al., Reference Kmet, Lee and Cook2004). Each study was evaluated against 14 criteria: (1) objective sufficiently described; (2) Study design evident and appropriate; (3) Method of subject/comparison group selection described and appropriate; (4) Subject and comparison group characteristics sufficiently described; (5) interventional and random allocation, if possible, was sufficiently described; (6) interventional and blinding of investigators, if possible, was reported; (7) interventional and blinding of subjects, if possible, was reported; (8) Outcome (s) well defined and robust to measurement bias; (9) sufficient sample size; (10) Analytic methods described and appropriate; (11) Some estimate of variance is reported for the main results; (12) Controlled for confounding; (13) Results reported in sufficient detail; (14) Conclusions supported by the results.

Each criterion was rated on a 3-point scale: 2 for criteria fully met, 1 for partially met, and 0 for not met. A summary score for each study was calculated using the formula: (actual score/potential maximum score) * 100, where the potential maximum score accounted for criteria deemed not applicable (NA). Scores were expressed on a linear scale from 0 to 100 and categorized into three quality levels: low (≤ 49), moderate (50–74), and high (≥ 75).

For studies involving SST, two investigators (NB and EP) independently rated both study quality and the validity of the SST. The validity assessment was conducted following the consensus guide developed by Verbruggen et al. (Reference Verbruggen, Aron, Band, Beste, Bissett, Brockett, Brown, Chamberlain, Chambers, Colonius, Colzato, Corneil, Coxon, Dupuis, Eagle, Garavan, Greenhouse, Heathcote, Huster and Boehler2019), which outlines 12 recommendations for designing a robust SST. Four key criteria from the guide were adapted into dichotomous items (i.e., criterion met or not met). Missing information was treated as criterion not fulfilled. SST validity was then categorized as follows: low validity (< 3 criteria met), moderate validity (3 criteria met), and high validity (4 criteria met) (further details provided in the Supplementary Material). This method has previously been used in a recent meta-analysis on inhibitory control in adult ADHD patients (Senkowski et al., Reference Senkowski, Ziegler, Singh, Heinz, He, Silk and Lorenz2024).

Conversely, the lack of a standardized consensus guide for designing GNGTs presented challenges for evaluating their quality. To address this limitation, we developed an 8-item evaluation grid based on insights from existing literature (Cyders & Coskunpinar, Reference Cyders and Coskunpinar2011, Reference Cyders and Coskunpinar2012; Friedman & Miyake, Reference Friedman and Miyake2004; Nigg, Reference Nigg2000; Wessel, Reference Wessel2018). Each item was weighted equally, with 1 point assigned per item, resulting in a maximum possible score of 8 points (further details provided in the Supplementary Material). Two investigators (NB and LC) independently evaluated both the overall quality of the studies and the validity of the GNGT design using this grid. Discrepancies were resolved through team discussion. A calibration session was conducted to increase inter-rater reliability. During this session, the two raters applied the assessments to 4 articles, which facilitated the identification of potential sources of disagreement and establishing rules for the assessment. The overall validity of the GNGT was then categorized as follows: low validity (≤ 2 criteria met), moderate validity (3–4 criteria met), and high validity (≥ 5 criteria met). To ensure the accuracy of the validity ratings, we reviewed supplementary materials when available and contacted corresponding authors for clarification when key task details were missing or unclear.

Notably, the quality assessment was not used to determine study eligibility. Instead, it was conducted to provide context for interpreting the findings and ensuring transparency in the evaluation process.

Meta-analysis model

Quantitative analyses were conducted using the R programming language and the Metafor package (version 3.2.1; Viechtbauer, Reference Viechtbauer2010). To estimate the overall motor inhibitory control performance in BPD, a random-effects model was applied to compute pooled effect sizes (Cohen’s d) for key outcomes, including reaction time on Go trials, commission errors on the GNGT, and the SSRT for the SST. This approach accounts for variability across studies (sample characteristics, task protocols, and methodological designs). This model provides a more generalizable estimate by assuming that the true effect size varies across studies. Between-study variance was estimated using restricted maximum likelihood (REML), an unbiased and efficient method for variance estimation.

A mixed-effects model was used to further investigate specific dimensions of motor inhibitory control, integrating moderator variables to explore potential sources of heterogeneity. Moderators were treated as fixed effects, while between-study variability was accounted for within a random-effects framework. This allowed for an analysis of whether specific study characteristics systematically influenced motor inhibitory control outcomes while maintaining generalizability across studies.

To better understand the influence of inhibitory control dimensions, we performed analyses based on correlational coefficients, applying Fisher’s Z transformation to stabilize variance and normalize correlation coefficient distributions. This transformation ensures comparability across studies by addressing the non-linearity of raw correlation coefficients and reducing biases in meta-analytic aggregation.

Effect size estimates were reported alongside key meta-analytic statistics: I 2, which quantifies the proportion of total variability attributable to between-study differences; τ 2 (tau-squared), which estimates absolute between-study variance; and Q-tests, which assess overall heterogeneity. Statistical significance was determined using p-values.

For studies reporting F-values from ANOVA analyses, we included only those with a single degree of freedom for the numerator to ensure accurate effect size estimation. When raw data (mean and standard deviation) were available, Cohen’s d was calculated between BPD and HC group. In cases where effect sizes were derived from correlation coefficients, Fisher’s Z transformations were used to improve interpretability.

Following data extraction, a random-effects model with a maximum likelihood estimator was computed to account for between-study variability, providing a more conservative estimate of the composite effect size. This random-effects model provided a pooled Cohen’s d effect size for SSRT, commission errors, and reaction times on Go trials, comparing BPD and HC groups across studies. Additionally, Egger’s test was conducted to assess potential publication bias and evaluate funnel plot asymmetry through weighted regression.

In addition to the primary analyses, we examined moderator effects – both categorical and continuous – using a mixed-effects model. To examine demographic factors, we included moderators such as sex and age. We also performed similar analyses to investigate the influence of task type (neutral vs. emotional), article quality, task validity, and BIS-11 subscales, where available. The results were reported with I 2 values to assess residual heterogeneity, QE-tests for overall heterogeneity, and QM-tests for the omnibus test of coefficients, along with corresponding confidence intervals and p-values. We reexamined funnel plot asymmetry and potential publication bias using Egger’s test to ensure a thorough evaluation of bias. We also conducted moderation analyses using the BIS-11 total score. These exploratory results are reported in the supplementary material.

Finally, a multilevel meta-analysis was conducted to further investigate the two GNGT outcomes: CE and RT. The overall effects of CE and RT were first assessed using a weighted multilevel model, which accounted for the potential variability between studies, ensuring that the results would be robust across different research designs. Egger’s test for publication bias was then conducted to assess the symmetry of the funnel plot. Additionally, a regression test for funnel plot asymmetry was performed to further evaluate the presence of publication bias in the multilevel model.

Results

Study selection

The electronic search yielded 789 articles: 65 from PubMed, 465 from ScienceDirect, 157 from Web of Science, and 102 from PsycInfo (Figure 3).

Figure 3. PRISMA flowchart of the study selection process. *other publication types (reviews, meta-analyses, posters, commentaries, editorials, letters to the editor, short communications, erratum/corrections).

Duplicate results (n = 183) were identified and removed through manual inspection by two independent authors (NB and AST), resulting in a total of 606 studies. Eight studies reported insufficient statistical values for the meta-analysis, and authors were contacted. We received data from two studies, which were then assessed for eligibility.

Screening of titles and abstracts, followed by full-text screening, led to the exclusion of 565 articles for the following reasons: they did not include a BPD group (n = 86), they did not include a HC group (n = 8), involved minors (n = 10), did not utilize an SST/GNGT paradigm (n = 87), were written in languages other than English (n = 4), were not published or accepted for publication in peer-reviewed journals during the period 2000–2025 or categorized as other publication types (reviews, meta-analyses, posters, commentaries, editorials, letters to the editor, short communications, erratum/corrections) (n = 355), were non-empirical dissertations (e.g., MSc or PhD Thesis) (n = 5), were animal studies (n = 2), were study protocols or not full-length articles (n = 5), and articles based on the same dataset as an already included article (n = 3).

It is important to note that LeGris, Links, van Reekum, Tannock, and Toplak (Reference LeGris, Links, van Reekum, Tannock and Toplak2012) and LeGris, Toplak, and Links (Reference LeGris, Toplak and Links2014) reported identical SSRTs, derived from the same experimental session and the same sample of participants. The same applies to Linhartová et al. (Reference Linhartová, Látalová, Barteček, Širůček, Theiner, Ejova, Hlavatá, Kóša, Jeřábková, Bareš and Kašpárek2020) and Linhartová et al. (Reference Linhartová, Širůček, Ejova, Barteček, Theiner and Kašpárek2021), as well as Soloff, White, Omari, Ramaseshan, and Diwadkar (Reference Soloff, White, Omari, Ramaseshan and Diwadkar2015) and Soloff, Abraham, Ramaseshan, Burgess, and Diwadkar (Reference Soloff, Abraham, Ramaseshan, Burgess and Diwadkar2017): in these cases, only the first article was included. Van Eijk et al. (Reference Van Eijk, Sebastian, Krause-Utz, Cackowski, Demirakca, Biedermann, Lieb, Bohus, Schmahl, Ende and Tüscher2015) also conducted both an SST and a GNGT. For Yang et al. (Reference Yang, Liu, Peng, Liu, Chu, Zheng, Cao and Yi2021), they performed two SSTs: one neutral and one emotional.

Screening of reference lists did not reveal any additional articles. Consequently, a total of 35 publications with 37 datasets – 11 SST and 26 GNGT – were included in the meta-analysis. Sample characteristics for all included studies are shown in Tables 2 and 3.

Table 2. Characteristics, summary information of methods, and results of included SST studies

Table 3. Characteristics, summary information of methods and results of included GNGT studies: commission errors and reaction times on Go trials

Overview of included studies

The selected studies encompass a mix of inpatient, outpatient, and community samples, providing a comprehensive assessment of inhibitory control deficits across different populations (Tables 2 and 3). The studies varied in sample size, ranging from small-scale investigations with fewer than 25 participants (De Vidovich et al., Reference De Vidovich, Muffatti, Monaco, Caramia, Broglia, Caverzasi, Barale and D’Angelo2016; Dinn et al., Reference Dinn, Harris, Aycicegi, Greene, Kirkley and Reilly2004; Leyton et al., Reference Leyton, Okazawa, Diksic, Paris, Rosa, Mzengeza, Young, Blier and Benkelfat2001; Ruchsow et al., Reference Ruchsow, Walter, Buchheim, Martius, Spitzer, Kächele, Grön and Kiefer2006; Völlm et al., Reference Völlm, Richardson, Stirling, Elliott, Dolan, Chaudhry, Del Ben, McKie, Anderson and Deakin2004) to larger studies with over 100 participants (Rubio et al., Reference Rubio, Jiménez, Rodríguez-Jiménez, Martínez, Iribarren, Jiménez-Arriero, Ponce and Avila2007; Ruocco et al., Reference Ruocco, Rodrigo, Lam, Ledochowski, Chang, Wright and McMain2021; Thomsen, Ruocco, Carcone, Mathiesen, & Simonsen, Reference Thomsen, Ruocco, Carcone, Mathiesen and Simonsen2017).

Participant demographics indicate a broad representation in terms of sex. While some studies included only female BPD participants (Cane, Carcone, Gardhouse, Lee, & Ruocco, Reference Cane, Carcone, Gardhouse, Lee and Ruocco2023; Carvalho Fernando et al., Reference Carvalho Fernando, Beblo, Schlosser, Terfehr, Wolf, Otte, Löwe, Spitzer, Driessen and Wingenfeld2013; Dinn et al., Reference Dinn, Harris, Aycicegi, Greene, Kirkley and Reilly2004; Ernst et al., Reference Ernst, Mohr, Schött, Rickmeyer, Fischmann, Leuzinger-Bohleber, Weiß and Grabhorn2018; Jacob et al., Reference Jacob, Gutz, Bader, Lieb, Tüscher and Stahl2010, Reference Jacob, Zvonik, Kamphausen, Sebastian, Maier, Philipsen, Elst, Lieb and Tüscher2013; Kaiser et al., Reference Kaiser, Roth, Rentrop, Friederich, Bender and Weisbrod2008; LeGris et al., Reference LeGris, Links, van Reekum, Tannock and Toplak2012; Michopoulos et al., Reference Michopoulos, Tournikioti, Paraschakis, Karavia, Gournellis, Smyrnis and Ferentinos2021; Mortensen, Rasmussen, & Håberg, Reference Mortensen, Rasmussen and Håberg2010; Ramos-Loyo et al., Reference Ramos-Loyo, Juárez-García, Llamas-Alonso, Angulo-Chavira, Romo-Vázquez and Vélez-Pérez2021; Rentrop et al., Reference Rentrop, Backenstrass, Jaentsch, Kaiser, Roth, Unger, Weisbrod and Renneberg2007; Thomsen et al., Reference Thomsen, Ruocco, Carcone, Mathiesen and Simonsen2017; Van Eijk et al., Reference Van Eijk, Sebastian, Krause-Utz, Cackowski, Demirakca, Biedermann, Lieb, Bohus, Schmahl, Ende and Tüscher2015; van Zutphen et al., Reference van Zutphen, Siep, Jacob, Domes, Sprenger, Willenborg, Goebel, Tüscher and Arntz2020; Wang et al., Reference Wang, van Eijk, Demirakca, Sack, Krause-Utz, Cackowski, Schmahl and Ende2017), two studies included only male BPD participants (Rubio et al., Reference Rubio, Jiménez, Rodríguez-Jiménez, Martínez, Iribarren, Jiménez-Arriero, Ponce and Avila2007; Völlm et al., Reference Völlm, Richardson, Stirling, Elliott, Dolan, Chaudhry, Del Ben, McKie, Anderson and Deakin2004). All studies recruited young to middle-aged adults.

Information on psychiatric comorbidities was systematically extracted and is presented in Tables 2 and 3. Additional details are provided in the Supplementary Material. All SST studies utilized neutral stimuli (Go: arrows, shapes, words, or letters; Stop: auditory or other visual cues), except for Yang et al. (Reference Yang, Liu, Peng, Liu, Chu, Zheng, Cao and Yi2021), who, in addition to the neutral condition, also administered an emotional condition (Go: emotional faces; Stop: color change) (Table 2).

For GNGT studies, some incorporated emotional or linguistic components to evaluate the influence of affective processing on inhibitory control (Carvalho Fernando et al., Reference Carvalho Fernando, Beblo, Schlosser, Terfehr, Wolf, Otte, Löwe, Spitzer, Driessen and Wingenfeld2013; Jacob et al., Reference Jacob, Zvonik, Kamphausen, Sebastian, Maier, Philipsen, Elst, Lieb and Tüscher2013; Silbersweig et al., Reference Silbersweig, Clarkin, Goldstein, Kernberg, Tuescher, Levy, Brendel, Pan, Beutel, Pavony, Epstein, Lenzenweger, Thomas, Posner and Stern2007; Sinke, Wollmer, Kneer, Kahl, & Kruger, Reference Sinke, Wollmer, Kneer, Kahl and Kruger2017; van Zutphen et al., Reference van Zutphen, Siep, Jacob, Domes, Sprenger, Willenborg, Goebel, Tüscher and Arntz2020) (Table 3).

SST and GNGT designs also varied, with differences in Go/Stop and Go/No-Go trial ratios, the nature of stop signals (e.g., auditory vs. visual), and other task parameters, contributing to variability in findings and influencing cross-study comparability.

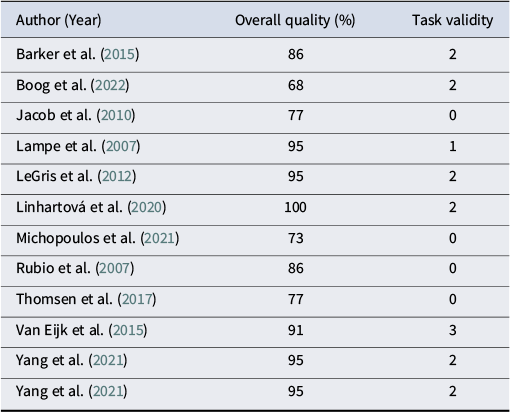

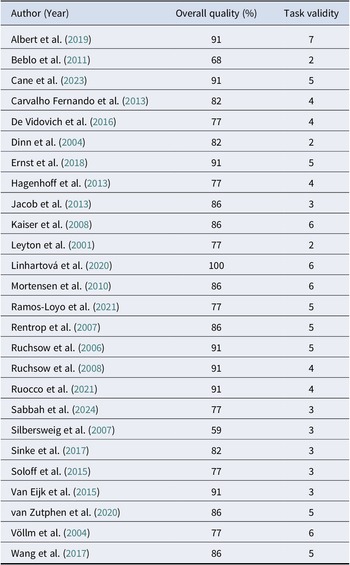

Quality assessment and task validity

Overall, all studies scored a high methodological rating (≥ 75), except for two SST studies, Boog et al. (Reference Boog, Dugonjic, Arntz, Goudriaan, Wetering and Franken2022) and Michopoulos et al. (Reference Michopoulos, Tournikioti, Paraschakis, Karavia, Gournellis, Smyrnis and Ferentinos2021), which scored 68 and 73, respectively, and two GNGT studies, Beblo et al. (Reference Beblo, Mensebach, Wingenfeld, Rullkoetter, Schlosser and Driessen2011) and Silbersweig et al. (Reference Silbersweig, Clarkin, Goldstein, Kernberg, Tuescher, Levy, Brendel, Pan, Beutel, Pavony, Epstein, Lenzenweger, Thomas, Posner and Stern2007), which scored 68 and 59, respectively (Tables 4 and 5).

Table 4. Quality assessment of SST studies

Table 5. Quality assessment of GNGT studies

In terms of task validity, all SST studies had low task validity (≤ 2 criteria met), except for one (Van Eijk et al., Reference Van Eijk, Sebastian, Krause-Utz, Cackowski, Demirakca, Biedermann, Lieb, Bohus, Schmahl, Ende and Tüscher2015), which had a moderate quality (3 criteria met). In contrast, GNGT studies demonstrated wider variability: three studies had low task validity (Beblo et al., Reference Beblo, Mensebach, Wingenfeld, Rullkoetter, Schlosser and Driessen2011; Dinn et al., Reference Dinn, Harris, Aycicegi, Greene, Kirkley and Reilly2004; Leyton et al., Reference Leyton, Okazawa, Diksic, Paris, Rosa, Mzengeza, Young, Blier and Benkelfat2001), ten had moderate task validity (Carvalho Fernando et al., Reference Carvalho Fernando, Beblo, Schlosser, Terfehr, Wolf, Otte, Löwe, Spitzer, Driessen and Wingenfeld2013; De Vidovich et al., Reference De Vidovich, Muffatti, Monaco, Caramia, Broglia, Caverzasi, Barale and D’Angelo2016; Hagenhoff et al., Reference Hagenhoff, Franzen, Koppe, Baer, Scheibel, Sammer, Gallhofer and Lis2013; Jacob et al., Reference Jacob, Zvonik, Kamphausen, Sebastian, Maier, Philipsen, Elst, Lieb and Tüscher2013; Ruchsow et al., Reference Ruchsow, Groen, Kiefer, Buchheim, Walter, Martius, Reiter, Hermle, Spitzer, Ebert and Falkenstein2008; Ruocco et al., Reference Ruocco, Rodrigo, Lam, Ledochowski, Chang, Wright and McMain2021; Sabbah, Mottaghi, Ghaedi, & Ghalandari, Reference Sabbah, Mottaghi, Ghaedi and Ghalandari2024; Silbersweig et al., Reference Silbersweig, Clarkin, Goldstein, Kernberg, Tuescher, Levy, Brendel, Pan, Beutel, Pavony, Epstein, Lenzenweger, Thomas, Posner and Stern2007; Sinke et al., Reference Sinke, Wollmer, Kneer, Kahl and Kruger2017; Van Eijk et al., Reference Van Eijk, Sebastian, Krause-Utz, Cackowski, Demirakca, Biedermann, Lieb, Bohus, Schmahl, Ende and Tüscher2015). Twelve had high task validity, ranging from 5 to 7 criteria met (Albert et al., Reference Albert, López-Martín, Arza, Palomares, Hoyos, Carretié, Díaz-Marsá and Carrasco2019; Cane et al., Reference Cane, Carcone, Gardhouse, Lee and Ruocco2023; Ernst et al., Reference Ernst, Mohr, Schött, Rickmeyer, Fischmann, Leuzinger-Bohleber, Weiß and Grabhorn2018; Kaiser et al., Reference Kaiser, Roth, Rentrop, Friederich, Bender and Weisbrod2008; Linhartová et al., Reference Linhartová, Látalová, Barteček, Širůček, Theiner, Ejova, Hlavatá, Kóša, Jeřábková, Bareš and Kašpárek2020; Mortensen et al., Reference Mortensen, Rasmussen and Håberg2010; Ramos-Loyo et al., Reference Ramos-Loyo, Juárez-García, Llamas-Alonso, Angulo-Chavira, Romo-Vázquez and Vélez-Pérez2021; Rentrop et al., Reference Rentrop, Backenstrass, Jaentsch, Kaiser, Roth, Unger, Weisbrod and Renneberg2007; Ruchsow et al., Reference Ruchsow, Walter, Buchheim, Martius, Spitzer, Kächele, Grön and Kiefer2006; van Zutphen et al., Reference van Zutphen, Siep, Jacob, Domes, Sprenger, Willenborg, Goebel, Tüscher and Arntz2020; Völlm et al., Reference Völlm, Richardson, Stirling, Elliott, Dolan, Chaudhry, Del Ben, McKie, Anderson and Deakin2004; Wang et al., Reference Wang, van Eijk, Demirakca, Sack, Krause-Utz, Cackowski, Schmahl and Ende2017). This variability made comparability between studies challenging.

Meta-analysis of stop-signal task performance: stop-signal reaction time (SSRT)

The meta-analysis on SSRT included 12 studies comparing BPD and HC groups. The analysis indicated a small-to-moderate motor inhibitory control impairment in BPD patients compared to HC (Cohen’s d = 0.30; 95% CI: 0.15 to 0.45; p < 0.0001; I 2 = 2.28%; Figure 4). Q-test reported low heterogeneity (Q (11) = 11.30, p = 0.418). The non-significant effect on Egger’s test suggested a symmetrical forest plot and absence of publication bias ( t = 0.6114, p = 0.5546; Figure 7A).

Figure 4. Forest plot for the meta-analysis on Stop-Signal Reaction Time.

Multilevel meta-analysis of Go/No-Go Task performance: commission errors and reaction times

The analysis of commission errors (CE) in the GNGT included 22 studies. A random-effects model revealed a moderate-to-large inhibitory control deficit in BPD patients compared to HC (Cohen’s d = 0.49; 95% CI: 0.23 to 0.75; p = 0.0002; I2 = 74.30%; Figure 5), reflecting increased impulsive responses and poorer inhibitory control in the BPD group. The Q-test for heterogeneity was significant (Q(21) = 77.77, p < 0.0001), indicating that methodological or sample-related differences may be contributing to the observed variance. Egger’s test found no evidence of publication bias (t = 1.64, p = 0.12; Figure 7B).

Figure 5. Forest plot for the meta-analysis on Commission Errors.

The analysis of reaction times (RT) on Go trials, based on 20 studies, showed no significant differences between BPD and HC participants (Cohen’s d = -0.13; 95% CI: -0.43 to 0.17; p = 0.38; Figure 6). However, heterogeneity was high (I 2 = 79.14%), suggesting considerable variability in effect sizes across studies. The Q-test for heterogeneity confirmed this (Q(19) = 79.95, p < 0.0001). Similarly, Egger’s test did not indicate publication bias (t = 0.50, p = 0.63; Figure 7C).

Figure 6. Forest plot for the meta-analysis on Reaction Times on Go trials.

Figure 7. A–D: Funnel plot for the meta-analysis on (A) Stop-Signal Reaction Time, (B) Commission errors, (C) Reaction Times on Go trials, and (D) multilevel meta-analysis.

In the multilevel meta-analysis, the overall moderator test was significant (QM(2) = 13.03, p = 0.0015). The effect of CE remained significant, with BPD participants showing poorer inhibitory control compared to HC (Cohen’s d = 0.46; 95% CI: 0.21 to 0.71; p = 0.0003; Figure 8). In contrast, there was no significant group difference in RT (Cohen’s d = –0.14; 95% CI: –0.43 to 0.16; p = 0.36; Figure 8). The Q-test remained significant (QE(40) = 157.71, p < 0.0001), indicating meaningful variability across studies. Furthermore, the regression test for funnel plot asymmetry in the multilevel model showed no significant bias (t = 1.4629, df = 39, p = 0.1515), further supporting the robustness of the results (Figure 7D). Figure 9 presents the effect sizes (Cohen’s d) from individual studies examining CE and RT. Overall, effect sizes for CE (depicted in blue) are predominantly positive, indicating that BPD participants tend to commit more errors than HC – consistent with impaired inhibitory control. In contrast, effect sizes for RT (in orange) are more variable, with some studies reporting slower responses in BPD participants (positive effects), and others showing faster responses (negative effects), potentially reflecting impulsive or premature responding. The red dashed line marks the average effect across all studies, suggesting a small-to-moderate overall difference between groups.

Figure 8. Forest plot for the multilevel meta-analysis on GNGT outcomes: Commission Errors (CE) and Reaction Times on Go trials (RT).

Figure 9. Study-Level Effect Sizes (Cohen’s d) for GNGT outcomes: Commission Errors (CE) and Reaction Times on Go trials (RT). Effect sizes for CE and RT are depicted in blue and orange respectively. positive effects indicate slower responses in BPD participants while negative effects reflect faster responses. The red dashed line marks the average effect across all studies.

Moderator analyses

Age and sex differences

Age was a significant predictor of SST performance. The meta-analysis revealed a positive association between age and SSRT (β = 0.0256, p = 0.0310), indicating that older participants exhibited longer SSRTs, reflecting poorer inhibitory control. Notably, no significant residual heterogeneity was detected (I 2 = 0.00%), suggesting that the relationship between age and SSRT was consistent across studies. In the GNGT, a significant association was found between age and reaction time on Go trials (β = 0.0600, p = 0.0367). Older participants had slower reaction times on Go trials, suggesting that age is associated with slower response execution. In contrast, commission errors (CE) were not significantly associated with age (β = 0.0306, p = 0.5263), indicating no clear age-related trend in the accuracy of response inhibition.

The role of sex as a moderator of motor inhibitory control performance was explored across all outcomes. In SSRT, the analysis did not yield a significant effect (QM(1) = 0.92, p = 0.34), suggesting that response inhibition impairments in BPD are comparable between males and females. However, in commission errors (incorrect response rate to No-Go trials), sex showed a trend-level effect (QM(1) = 3.26, p = 0.071), with some indication of a potentially lower rate of commission errors in females compared to males, though this result did not reach statistical significance. The model accounted for 24.16% of heterogeneity (R2 = 24.16%), with residual heterogeneity remaining substantial (I2 = 68.27%, QE(19) = 62.47, p < 0.0001). This finding suggests that while sex may influence performance differences between groups, other unexplored factors also contribute to variability.

For reaction times on Go trials, sex did not significantly moderate performance (QM(1) = 2.16, p = 0.14), indicating that response speed differences in BPD are not influenced by sex.

Task type (neutral vs. emotional stimuli)

The impact of task type – whether the task involved neutral or emotional stimuli – was examined across all three outcomes. For SSRT, the moderator analysis showed no significant effect (QM(1) = 1.55, p = 0.21), indicating that response inhibition deficits in BPD were present regardless of the emotional content of the task. Similarly, in commission errors, no significant effect of task type was found (QM(1) = 0.42, p = 0.52), suggesting that emotional context did not substantially alter incorrect response rates on No-Go trials in the GNGT. The same was true for reaction times on Go trials, where no significant effect was observed (QM(1) = 0.90, p = 0.34). These findings suggest that inhibitory control deficits in BPD, as measured by these tasks, are relatively consistent regardless of whether the task involves emotionally charged or neutral stimuli.

Article quality

To assess whether study rigor influenced the results, article quality was examined as a moderator. No significant effect was observed for SSRT (QM(1) = 0.98, p = 0.32), indicating that methodological differences did not drive the consistency of response inhibition deficits across the studies. Similarly, commission errors and reaction times on Go trials showed no significant moderation by article quality (QM(1) = 0.12, p = 0.73 and QM(1) = 0.44, p = 0.51, respectively). These findings indicate that methodological differences across studies did not substantially affect the results, reinforcing the robustness of the overall conclusions.

Task validity

The validity of the tasks used to measure inhibitory control was also examined. For SSRT, task validity did not significantly moderate the results (QM(1) = 2.76, p = 0.097), indicating that differences in task implementation did not have a strong influence on the estimated deficits. Similarly, commission errors were not significantly influenced by task validity (QM(1) = 0.28, p = 0.594). For reaction times on Go trials, task validity showed a non-significant trend toward significance (QM(1) = 3.25, p = 0.07), suggesting that differences in task implementation may partially account for the variability in reported response speeds between BPD and HC groups. Although not reaching statistical significance, this pattern indicates that more rigorous or standardized task designs could potentially reduce heterogeneity in RT outcomes.

Meta-analysis of the relationship between task performance and self-reported impulsivity

Association between BIS-11 subscales and SST performance

The mixed-effects model (k = 7) revealed no significant association between the motor impulsivity BIS-11 subscale and SSRT (β = -0.0071, SE = 0.0151, p = 0.6376). Residual heterogeneity was moderate (τ 2 = 0.0419, I 2 = 35.12%). Similarly, no significant association was found between the cognitive impulsivity BIS-11 subscale and SSRT (β = 0.0032, SE = 0.0161, p = 0.8399). Residual heterogeneity was moderate (τ 2 = 0.0465, I 2 = 37.57%).

Association between BIS-11 subscales and GNGT performance

No significant association was observed between the motor impulsivity BIS-11 subscale and commission errors (β = −0.1336, SE = 0.0988, p = 0.1762). Notably, residual heterogeneity was negligible (τ 2 = 0, I 2 = 0.00%). The analysis indicated no significant association between the cognitive impulsivity BIS-11 subscale and commission errors (β = −0.0389, SE = 0.0276, p = 0.1587), with negligible residual heterogeneity (τ 2 = 0, I 2 = 0.00%).

As for RT on Go trials, there was no significant association between the motor impulsivity BIS-11 subscale and reaction times (β = −0.0587, SE = 0.1539, p = 0.7029), with negligible residual heterogeneity (τ 2 = 0, I 2 = 0.00%). Similarly, no significant association was found between the cognitive impulsivity BIS-11 subscale and reaction times (β = −0.0251, SE = 0.0303, p = 0.4082), with negligible residual heterogeneity (τ 2 = 0, I 2 = 0.00%).

Discussion

This study is the first meta-analysis to investigate motor inhibitory control deficits – a key aspect of impulsivity – in BPD, using data from both the Stop-Signal Task and the Go/No-Go Task. It also explores how self-reported impulsivity relates to task-based performance. The findings demonstrate that motor impulsivity is higher in individuals with BPD than in healthy controls, with a small to moderate effect size. However, results concerning emotional components challenge common assumptions about BPD, as they do not appear to moderate motor impulsivity. Furthermore, no significant correlation was observed between self-reported impulsivity measures and performance on these neuropsychological tasks.

Inhibitory control deficits measured by stop-signal and Go/No-Go tasks

Data from 12 studies comparing SSRT in BPD and HC revealed slight inhibitory control deficits in BPD, as expressed by prolonged SSRTs. However, the effect size was small to moderate (d=0.30) and results were highly consistent across included studies. In comparison, a broader meta-analysis examining various psychiatric conditions that did not include BPD found medium deficits in SSRT for ADHD (g = 0.62), OCD (g = 0.77), and Schizophrenia (SCZ) (g = 0.69) (Lipszyc & Schachar, Reference Lipszyc and Schachar2010). This suggests that while BPD is associated with inhibitory control deficits, the extent of these deficits measurable by SST is smaller than those observed in ADHD, OCD, and SCZ.

Furthermore, we evaluated SST validity based on the recommendations of Verbruggen et al. (Reference Verbruggen, Aron, Band, Beste, Bissett, Brockett, Brown, Chamberlain, Chambers, Colonius, Colzato, Corneil, Coxon, Dupuis, Eagle, Garavan, Greenhouse, Heathcote, Huster and Boehler2019) in a recent consensus paper, thus enhancing the reliability of our findings. Despite most studies having low task validity, this did not significantly influence SSRT measures.

The analysis of commission errors and reaction times in the GNGT included 22 and 20 studies, respectively. BPD patients showed significantly higher commission errors than HCs but did not significantly differ in reaction times on Go trials. Heterogeneity was high, suggesting considerable variability in study results. Contrary to the SST, there are no clear guidelines for assessing GNGT validity, which makes assessment challenging. Our meta-analysis supports commission errors, but not reaction times on Go trials, as more reliable measures for assessing inhibitory control deficits in adult BPD. This aligns with a meta-analysis that examined GNGT performance across various psychiatric disorders and found that increased commission errors are indicative of impaired response inhibition, a characteristic observed in multiple psychopathologies (Wright, Lipszyc, Dupuis, Thayapararajah, & Schachar, Reference Wright, Lipszyc, Dupuis, Thayapararajah and Schachar2014).

Overall, our findings confirm significant deficits in inhibitory control among BPD patients, consistent with previous research that has reported moderate to large impairments across multiple cognitive domains (D’Iorio, Di Benedetto, & Santangelo, Reference D’Iorio, Di Benedetto and Santangelo2024), including inhibition (D’Iorio et al., Reference D’Iorio, Di Benedetto and Santangelo2024; Unoka & Richman, Reference Unoka and Richman2016). These results also align with broader studies indicating that inhibitory control deficits are common across various psychiatric conditions. Impaired inhibitory control has been observed in bipolar disorder (Wan, Pei, Zhang, & Gao, Reference Wan, Pei, Zhang and Gao2024), gambling disorder (Hodgins & Holub, Reference Hodgins and Holub2015), eating disorders (Claudat, Simpson, Bohrer, & Bongiornio, Reference Claudat, Simpson, Bohrer, Bongiornio, Patel and Preedy2021), and substance use disorders (Hayes, Herlinger, Paterson, & Lingford-Hughes, Reference Hayes, Herlinger, Paterson and Lingford-Hughes2020), supporting the idea that these deficits may be a shared feature of impulsivity-related psychopathology. Therefore, targeting inhibitory control could have wide-reaching clinical benefits beyond BPD alone.

Moderator and multilevel analyses

The results of this meta-analysis indicate that age significantly influences inhibitory control in BPD, but its effects vary depending on the task used to assess it. In the SST, the SSRT increased with age, suggesting a decline in inhibitory control. However, the GNGT revealed longer reaction times on Go trials for older adults, but commission errors did not increase, indicating that while response execution slowed, inhibitory accuracy remained unchanged. In other words, although there was an age-related delay in response execution among older BPD patients, their precision and accuracy did not deteriorate.

Behavioral slowing in older adults has been observed in various RT tasks (Cuypers et al., Reference Cuypers, Thijs, Duque, Swinnen, Levin and Meesen2013; Hunter, Thompson, & Adams, Reference Hunter, Thompson and Adams2001), including GNGT (Fujiyama, Tandonnet, & Summers, Reference Fujiyama, Tandonnet and Summers2011), and has been explained by an age-related decline in the ability of motor commands to effectively recruit the alpha motoneuron pool (Fujiyama et al., Reference Fujiyama, Tandonnet and Summers2011). However, the relationship between age and inhibition remains controversial. While some studies report impaired motor inhibitory control with age (Allen et al., Reference Allen, Johnson, Burke, Sammon, Wu, Kramer, Wu, Schatten, Armey and Hooley2021), others provide more nuanced findings. For instance, Sebastian et al. (Reference Sebastian, Baldermann, Feige, Katzev, Scheller, Hellwig, Lieb, Weiller, Tüscher and Klöppel2013) found that, in a simple GNGT, aging was associated with increased activation in the core inhibitory network, including the inferior frontal gyrus (IFG), right middle frontal gyrus, pre-supplementary motor area (pre-SMA), and basal ganglia, as well as in parietal areas. In contrast, in the SST – the most demanding of the tasks – aging was associated with decreased activation. This suggests that as the inhibitory load increases, older adults engage additional regions of the inhibitory network. However, when the load exceeds their compensatory capacity, performance declines, reflecting reduced activation in these areas.

Further research has indicated that older adults exhibit altered brain activation patterns, such as hypoactivation in the right IFC, pre-SMA, and basal ganglia. Despite these changes, their ability to inhibit responses in the SST was not significantly worse than that of younger adults (Coxon et al., Reference Coxon, Goble, Leunissen, Van Impe, Wenderoth and Swinnen2016). This suggests that inhibitory control deficits in older adults are linked to less efficient recruitment of cortical and subcortical regions. Consequently, older individuals may rely on different neural mechanisms or brain regions to achieve similar performance.

Sex showed a trend-level effect for commission errors, indicating a potential difference in incorrect responses on No-Go trials between males and females, though not reaching significance. Task type (neutral vs. emotional) and article quality did not significantly moderate any of the outcomes, suggesting that the main findings are stable across studies with varying designs and methodological rigor. Finally, task validity showed a non-significant trend toward influencing reaction times on Go trials in GNGT, implying that differences in task implementation could potentially affect how response speed is measured in BPD. These findings suggest that inhibitory control impairments in BPD are largely consistent across different task types, sex, and study quality but that task validity may influence how reaction time differences are interpreted in the GNGT, warranting careful consideration.

The results of the multilevel meta-analysis point to a pattern where CE may offer a more reliable marker of inhibitory control difficulties in individuals with BPD. Most studies reported positive effect sizes, suggesting that BPD participants tend to make more errors than HCs – a finding that echoes previous work linking psychopathology with challenges in withholding automatic or inappropriate responses (Wright et al., Reference Wright, Lipszyc, Dupuis, Thayapararajah and Schachar2014). RT, by contrast, showed more variability across studies. Some reported slower responses, while others found faster – or potentially impulsive – reaction patterns in the BPD group. This inconsistency could be shaped by differences in task design, sample characteristics, or cognitive strategies used during the task. Although the average effect size across studies falls in the small-to-moderate range, it also highlights how complex and context-dependent RT can be as a measure of impulsivity. Overall, while CE appears to be a more stable indicator of inhibitory control across studies, RT may capture different facets of behavior that require more careful interpretation.

Association between task performance and self-reported impulsivity

We also examined the relationship between self-reported impulsivity, as measured by the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale (BIS) subscales, and behavioral measures of inhibitory control in BPD patients, as measured by SST and GNGT performance. We found no significant associations between the BIS-11 motor and cognitive subscales and performance metrics from the SST and GNGT, including SSRT, commission errors, and reaction times. Potential explanations may include that self-report measures capture trait impulsivity, whereas SST and GNGT assess state-dependent, task-specific inhibitory control (Figure 1). Furthermore, BPD patients might lack insight into their own impulsivity, resulting in weak correlations between self-reported and behavioral measures.

These results align with previous research suggesting a dissociation between self-reported impulsivity and behavioral measures of inhibitory control. For instance, a meta-analysis by Cyders and Coskunpinar (Reference Cyders and Coskunpinar2011) found that self-report measures of impulsivity were only weakly correlated with behavioral measures. Similarly, research on 195 undergraduate students has shown that self-report and behavioral measures of impulsivity seem to assess different underlying constructs, with little overlap between them (Barnhart & Buelow, Reference Barnhart and Buelow2017).

In the context of psychiatric populations, a meta-analysis on the implication of impulsivity in self-harm and suicidal behavior in young people has shown that self-report measures of impulsivity and behaviors such as self-harm and suicidal behaviors are weakly associated, while neurocognitive measures of impulsivity show a medium to large effect size in relation to these behaviors (McHugh et al., Reference McHugh, Chun Lee, Hermens, Corderoy, Large and Hickie2019). Consequently, the results of the meta-analysis indicate that the GNGT and SST are particularly relevant for assessing motor impulsivity in BPD patients, as both tasks measure deficits in motor inhibition, which is a key component of impulsivity that may contribute to suicidal and parasuicidal behaviors in this population.

Taken together, these findings suggest that self-report and behavioral measures of impulsivity may capture distinct aspects of impulsive behavior, highlighting the importance of utilizing multiple assessment methods to gain a comprehensive understanding of impulsivity.

Emotional context and inhibitory control in BPD

While emotion dysregulation is a hallmark of BPD, our meta-analysis did not reveal a significant moderating effect of emotional task variants on inhibitory control performance. This result may seem counterintuitive, especially given the widespread assumption that inhibitory control deteriorates under emotional distress in BPD populations. Several plausible explanations warrant consideration.

First, the emotional manipulations used in studies included in our meta-analysis were highly heterogeneous. Recent work by Mirabella and Montalti (Reference Mirabella and Montalti2025) emphasize that the emotional relevance of the task is a critical moderator of behavioral outcomes. Emotional stimuli that are task-relevant (i.e., where participants must explicitly process or respond to emotional content) are more likely to impact response inhibition than task-irrelevant stimuli (Calbi et al., Reference Calbi, Montalti, Pederzani, Arcuri, Umiltà, Gallese and Mirabella2022; Mancini, Falciati, Maioli, & Mirabella, Reference Mancini, Falciati, Maioli and Mirabella2020; Mauersberger, Blaison, & Hess, Reference Mauersberger, Blaison and Hess2024; Mirabella, Reference Mirabella2023; Mirabella, Grassi, Mezzarobba, & Bernardis, Reference Mirabella, Grassi, Mezzarobba and Bernardis2023). Many of the included studies employed covert emotional manipulations (e.g., background emotional faces), which may not have elicited sufficiently strong affective responses to disrupt inhibitory performance. Furthermore, the specificity of emotional content may matter: individualized, personally salient emotional cues or interpersonal scenarios might better capture the dysregulatory contexts most relevant to BPD symptoms than standardized stimuli.

Second, recent experimental evidence indicates that emotional effects on SSRT can be artifactually inflated or obscured depending on how inhibition is estimated. Coccaro et al. (Reference Coccaro, Maffei, Kleffner, Carolan, Vallesi, D’Adamo and Liotti2024) demonstrated that mean-based SSRT calculations, which are still commonly used in the field, are highly sensitive to strategic slowing and skewed RT distributions that are likely in emotionally loaded conditions. Emotional interference was significant only when using the mean method, which is now recognized to overestimate SSRT. In contrast, more robust methods, such as the integration approach recommended by the Stop-Signal Task consensus guidelines (Verbruggen et al., Reference Verbruggen, Aron, Band, Beste, Bissett, Brockett, Brown, Chamberlain, Chambers, Colonius, Colzato, Corneil, Coxon, Dupuis, Eagle, Garavan, Greenhouse, Heathcote, Huster and Boehler2019, revealed no effect of emotions on inhibition. These methodological inconsistencies may partly account for why our moderator analysis did not yield significant results, even though smaller-sample studies using less rigorous SSRT calculations sometimes report emotional interference.

Third, the type of emotional manipulation, whether incidental or induced, may differentially impact response inhibition. Coccaro et al. (Reference Coccaro, Maffei, Kleffner, Carolan, Vallesi, D’Adamo and Liotti2024) incorporated a state-dependent manipulation (frustration induction) alongside facial expressions, finding that the emotional context modulated response strategies during go trials (e.g., increased omissions, strategic slowing), but did not affect SSRT when properly estimated. This suggests that emotion may shift task engagement and proactive control strategies rather than directly impair reactive inhibition. Our findings may reflect similar compensatory adjustments, which mask differences in SSRT between emotional and neutral conditions.

Additionally, it is important to consider the potential confounding role of comorbidities. ADHD, for instance, is frequently comorbid with BPD and independently associated with deficits in motor inhibition. If comorbid conditions were not systematically assessed or controlled across studies, they could have contributed to variability in inhibitory performance irrespective of emotional manipulations. While we have extracted and reported whether each study evaluated or excluded comorbidities (see Supplementary Tables S1–S2), the inconsistent handling of these factors likely introduced noise that limited our ability to detect moderator effects.

Altogether, our findings align with growing skepticism about the robustness of emotion-induced inhibitory deficits in BPD when examined using traditional SST paradigms. This does not mean that emotion has no impact, but rather that the field must move toward more ecologically valid, methodologically rigorous paradigms (Barakat et al., Reference Barakat, Dechant, Poulet, Cailhol, Brunelin, Friehs and Neige2025). Future studies should prioritize task-relevant emotional conditions, participant-specific emotional cues, and robust SSRT estimation methods. They should also explicitly evaluate comorbid conditions and explore how emotional context modulates not just inhibition per se, but the broader cognitive control strategies that individuals deploy in high-arousal or frustrating environments.

Limitations & future directions

While this meta-analysis offers important insights into inhibitory control deficits in BPD, several limitations should be considered.

First, substantial variability was observed across studies in Go/No-Go commission errors and reaction times. This high heterogeneity may stem from differences in task parameters, sample characteristics, or methodological variations, such as discrepancies in stimulus timing, response deadlines, or definitions of commission errors. To enhance comparability across studies, future research should prioritize standardizing task implementations. It is also worth noting that potentially valuable outcomes, like omission errors, were rarely included in the data. Incorporating additional SST and GNGT metrics could offer a fuller picture of inhibitory control difficulties in individuals with BPD. To partly address these discrepancies, we developed a task validity scoring system that captured key methodological features known to influence task reliability. Moderator analyses revealed that task validity showed a trend toward influencing Go trial reaction times, suggesting that differences in task implementation may partially contribute to variability in response speed across studies. In contrast, task validity did not significantly moderate SSRT or commission errors, indicating that these outcomes were relatively unaffected by methodological variation as captured by our scoring system. Unfortunately, the lack of consistent and detailed reporting across studies limited our ability to systematically compare specific task features – such as stop-signal modality or feedback timing – and to identify which variations produce the most reliable effects. Future studies should adopt standardized task protocols and reporting checklists to enhance replicability and facilitate meaningful comparisons across experimental designs. Incomplete or inconsistent reporting of task parameters limited our ability to score some studies with full confidence, despite attempts to verify details through supplementary materials and author correspondence.

Second, the inclusion of studies with diverse clinical populations and comorbid conditions may have influenced the results. Many BPD participants had comorbid disorders – such as major depressive disorder or substance use disorders – and were often taking medications, all of which can independently affect inhibitory control. While this reflects the clinical reality of BPD, it makes it harder to isolate BPD-specific effects. For example, ADHD, which frequently co-occurs with BPD, is also associated with pronounced motor impulsivity (Senkowski et al., Reference Senkowski, Ziegler, Singh, Heinz, He, Silk and Lorenz2024) and may have contributed to the observed effects. Most studies included in this meta-analysis did not provide sufficient information on comorbidities or medication status. Therefore, future studies should aim to better control for comorbidities and medication use to clarify the unique contribution of BPD to inhibitory control deficits.

Third, the choice of self-report impulsivity measures for moderation analyses was constrained by the availability of data across studies. Although the UPPS-P scale provides a more comprehensive and multidimensional assessment of impulsivity – and is arguably more appropriate in the context of BPD (Peters, Upton, & Baer, Reference Peters, Upton and Baer2013) – it was reported in only two SST studies and three GNGT studies in our dataset. This limited availability made it infeasible to conduct meaningful or representative moderation analyses with UPPS-P scores. Consequently, we relied on the BIS-11, which was the most commonly reported self-report measure. Future meta-analytic work would benefit from more consistent use of psychometrically robust impulsivity measures such as the UPPS-P to better characterize how specific impulsivity dimensions relate to inhibitory control performance in BPD.

Fourth, most studies relied solely on behavioral measures of inhibitory control, limiting the ability to explore underlying neurobiological mechanisms. Incorporating neuroimaging techniques (e.g., fMRI, EEG) or psychophysiological measures could provide deeper insights into the neural circuits involved in inhibitory control deficits in BPD.

Fifth, even though Egger’s test did not indicate publication bias for any measures, it remains a potential concern. The existence of unpublished studies with null findings could influence the overall effect size estimates. Future research should prioritize pre-registration and open data practices to reduce potential reporting biases.

Although BPD typically emerges during adolescence or early adulthood, the mean participant age in our meta-analysis was 28.2 years in the BPD group and 28.4 years in the healthy control group. This reflects a broader trend in the literature, as most included studies focused on adult populations and excluded minors due to ethical, methodological, or logistical constraints. As a result, our findings may not fully capture the developmental trajectory of inhibitory control deficits in BPD. Some evidence suggests that impulsivity decreases with age (Steinberg et al., Reference Steinberg, Albert, Cauffman, Banich, Graham and Woolard2008), likely reflecting the slow development of brain regions involved in inhibitory control, particularly the prefrontal cortex (Blakemore & Robbins, Reference Blakemore and Robbins2012). Consistent with this, our moderator analyses showed that older samples tended to exhibit longer SSRTs and longer reaction times on Go trials in GNGT, which aligns with normative age-related declines in motor processing speed. Interestingly, commission errors did not increase with age, suggesting that inhibitory accuracy may remain relatively preserved in adulthood – possibly due to compensatory strategies or increased cognitive control with age. Longitudinal studies tracking inhibitory control from adolescence into adulthood in individuals with BPD are needed to clarify how these deficits evolve over time and whether early interventions might alter their trajectory.

Finally, the effect sizes observed – particularly for SSRT (d = 0.30) – were relatively small, suggesting that while inhibitory control deficits are present, they may not be as pronounced as previously thought. Further research is needed to explore whether specific BPD subgroups (e.g., those with higher impulsivity or self-harm behaviors) exhibit more severe impairments and examine the extent to which inhibitory control deficits impact daily functioning.

Strengths and clinical implications

Despite these limitations, this meta-analysis provides strong evidence for inhibitory control deficits in BPD, particularly in Go/No-Go commission errors. The analysis included a large dataset (n = 38) to provide more robust effect size estimates. Additionally, incorporating both SST and GNGT allowed for a more nuanced understanding of motor inhibitory control, thereby distinguishing between deficits in withholding an action (GNGT) and canceling an already initiated one (SST). The greater deficits observed in the GNGT may indicate that BPD patients struggle more with withholding responses, meaning they find it harder to anticipate and prevent inappropriate actions before they occur. From a neurocognitive perspective, the differential sensitivity of these tasks likely reflects distinct underlying neural mechanisms (Raud et al., Reference Raud, Westerhausen, Dooley and Huster2020).

From a clinical standpoint, the findings highlight the Go/No-Go Task as a particularly sensitive measure of inhibitory control deficits in BPD. This task could serve as a useful tool in assessing impulsivity, tracking treatment progress, and personalizing interventions. Although SST and GNGT are not diagnostic tools per se, they offer standardized, performance-based metrics of motor inhibitory control that may assist clinicians in identifying at-risk individuals and evaluating treatment-related changes. As part of a multimodal assessment strategy, they may also help in patient stratification or tracking cognitive markers of impulsivity over time. Their integration into clinical trials and digital assessment platforms could enhance the precision of interventions targeting impulsivity in BPD.

Furthermore, investigating the shared neural substrates of motor and cognitive inhibition is crucial for understanding inhibitory deficits in impulsivity-related disorders such as BPD. Given that impulsivity is a core feature of BPD, impairments in domain-general inhibitory control may manifest not only as difficulties in action stopping but also in cognitive regulation, such as intrusive thoughts or emotional dysregulation. The results of this meta-analysis demonstrated that BPD patients exhibit deficits in SST and GNGT performance, reflecting compromised motor inhibition, but similar impairments in cognitive inhibition tasks (Sala et al., Reference Sala, Caverzasi, Marraffini, De Vidovich, Lazzaretti, d’Allio, Isola, Balestrieri, D’Angelo, Thyrion, Scagnelli, Barale and Brambilla2009) could further elucidate the underlying neurocognitive dysfunctions in this population. A meta-analysis on cognitive inhibitory control in psychiatric disorders reported compromised cognitive inhibition in anxiety and depression patients (Stramaccia, Meyer, Rischer, Fawcett, & Benoit, Reference Stramaccia, Meyer, Rischer, Fawcett and Benoit2021). Understanding this domain-general mechanism has broad implications, from refining models of impulsivity to developing targeted interventions that enhance inhibitory control across multiple domains.

Therapeutically, these results emphasize the need to target inhibitory control deficits in treatment approaches. Interventions such as cognitive remediation therapy, dialectical behavior therapy, and impulse control training could help strengthen inhibitory control and reduce impulsive behaviors in BPD. Additionally, emerging non-invasive brain stimulation techniques show promise in modulating neural circuits associated with impulsivity and other core symptoms (Brevet-Aeby, Brunelin, Iceta, Padovan, & Poulet, Reference Brevet-Aeby, Brunelin, Iceta, Padovan and Poulet2016), potentially serving as a complementary approach to improving inhibitory control in BPD (Lisoni et al., Reference Lisoni, Barlati, Deste, Ceraso, Nibbio, Baldacci and Vita2022).

Conclusion