Introduction

During the Second World War, Slovenia was marked by a civil war between the anti-communist units collaborating with the occupying German and Italian forces and the communist-oriented partisan movement (Nose, Reference Nose2017). In addition to the crimes committed by the occupiers and their collaborators, whose victims have a place in collective memory and memorial landscape since 1945, Slovenia is home to around 700 concealed individual and mass graves where victims killed by the partisan movement are buried, and their memory supressed (Ferenc, Reference Ferenc2018; Dežman, Reference Dežman and Dežman2021a: 63; see also Jamnik, Reference Jamnik, Groen, Márquez-Grant and Janaway2015; Dežman, Reference Dežman2019a, Reference Dežman2021b).

Most of the smaller mass and individual graves date to the time of the Second World War, while the largest graves were created in the post-war period in 1945. In May 1945, groups of soldiers and civilians, opponents of the partisan movement and communist ideas, retreated primarily to Austria, hoping to find safety there or to transit to Italy from the camp at Viktring near Klagenfurt, Austria. However, between 27 and 31 May 1945, the British Army returned to Slovenia (among others) a large part of the Slovenian Home Guard (Slovensko domobranstvo) and civilians, handing them over to the Yugoslav Army, i.e. the former Partisan Army, or National Liberation Army, restructured into the Yugoslav Army on 1 March 1945 (Klanjšček, Reference Klanjšček1978: 907; Ferenc, Reference Ferenc2018: 77–78). After their arrival in prisoner of war (POW) camps, Slovenes, Croats, Serbs, and many others were taken to execution sites and killed. It is estimated that around 15,000 Slovenes and about 85,000 people of other nationalities, mostly Croats, were killed in these massacres (Dežman, Reference Dežman and Dežman2019b: 115–34). Among the largest killing sites is the anti-tank ditch in Tezno near Maribor, estimated to contain the remains of around 15,000 victims (Ferenc, Reference Ferenc2012: 568). Among already investigated mass graves, Huda Jama stands out with 1410 excavated victims (Košir & Leben Seljak, Reference Košir, Leben Seljak and Dežman2019a: 221), the partially excavated anti-tank ditch near Mostec with 534 victims (Košir & Leben Seljak, Reference Košir, Leben Seljak and Dežman2021a: 214; Reference Košir and Leben Seljak2024), the mass grave of Košnica near Celje with 306 or 307 excavated victims (Rozman et al., Reference Rozman, Josipovič, Kot, Djokić, Leben Seljak, Košir and Dežman2019: 490), and Brezno 3 with 258–60 victims (Košir & Leben Seljak, Reference Košir, Leben Seljak and Dežman2021b: 176). Currently, the largest grave that has been examined, and the largest confirmed grave of Slovenes, is Jama pod Macesnovo gorico (the cave under Macesnova gorica hereafter), which was investigated in stages between 2004 and 2022.

The Cave Under Macesnova Gorica

The cave under Macesnova gorica is situated in south-eastern Slovenia, within the karstic plateau of Kočevski Rog. The cave is located along the Kočevje-Rog road, approximately 12 km from Kočevje (Figure 1A), within the old dry karstic valley of Koprivniško podolje, which extends from Stari Log north-westwards past Trnovec (at an altitude of 582 m asl), continuing south-eastwards towards Rajhenav (662 m asl) and Koprivnik (620 m asl).

Figure 1. Location of Kočevje (A), the cave under Kren (B) and the cave under Macesnova gorica (C).

The karstic region where the limestone cave is situated (Figure 1C), has undergone significant geological changes in the past, including tectonic shifts as well as weathering and erosion of the interior. The formation of the cave is associated with the collapse of a once larger cave shaped by an underground river (Mihevc, Reference Mihevc and Dežman2021: 160). The cave is one of the known mass grave sites in Kočevski Rog that has become synonymous with extrajudicial post-war executions. According to oral tradition, Slovenian victims were supposedly buried in the cave under Kren, approximately 4 km distant (Figure 1B). This cave served as a central memorial site for all Slovenians killed by the partisan movement after the war’s end, as it was widely believed to be the largest burial site of Slovenian victims. However, fieldwork conducted in 2004 refuted this (Ferenc, Reference Ferenc, Ferenc and Petkovšek2006), as only objects related to the Croatian and Chetnik armies were discovered in the vicinity of the cave. This was further confirmed by archaeological investigations around the cave under Kren in 2017 and 2019 (Košir, Reference Košir and Dežman2019a, Reference Košir and Dežman2021), which found no evidence of Slovenian victims.

Some of the rare survivors of the massacres have left some information about the details of the events prior the execution and about the execution at the cave under Macesnova gorica. According to their testimonies, bound victims were beaten with wooden sticks and other tools on their way to the execution site (see Tolstoj et al., Reference Tolstoj, Klepec and Kovač1991). Milan Zajec also stated that partisans used wires about 60 cm long to tie up prisoners, and the captives were untied and retied near the cave after being stripped (Zajec, cited in Ižanec, Reference Ižanec1965: 191–201). Such information was crucial for the interpretation of certain archaeological findings.

Archaeological Investigations of the Cave under Macesnova Gorica

The initial exploration in 2004 of the area around the cave under Macesnova gorica was suggested by the criminal police superintendent Pavel Jamnik and conducted by the historian Mitja Ferenc along with history students. According to the published data, they discovered approximately 45 kg of various objects in the sinkhole next to the cave (Ferenc, Reference Ferenc2005: 96–98, Reference Ferenc, Ferenc and Petkovšek2006: 161–62). A more systematic approach was undertaken in 2017 by the archaeological team of the archaeological company Avgusta, which conducted excavations of the sinkhole area and a metal detector survey of the broader area around the cave (Košir, Reference Košir and Dežman2019b, Reference Košir2019c). The purpose of the survey was to retrieve the remaining discarded items from the sinkhole and to explore the surrounding area to reconstruct the events and the path taken by the victims to the execution site. A combination of a metal detector survey and quadrant excavation with soil sieving was used at the location of the sinkhole (Figure 2). The area of the sinkhole was divided into quadrants measuring 2 × 2 m and excavated. Thus, a total of 204 m2 were examined in detail (Košir, Reference Košir and Dežman2019b: 513–16). In the vicinity of the cave and sinkhole, a metal detector survey with precise coordinates of the findings was undertaken, covering a total area of approximately 5.1 hectares. A total of 477 objects at 241 locations was thus discovered and documented (Košir, Reference Košir and Dežman2019b: 516–17).

Figure 2. Excavation of the sinkhole in 2017.

From August to October 2019, as part of the preparations for the exhumation of human remains from the cave—intended to retrieve the remains and determine the victims’ sex, age, cause of death, nationality, and possible identity, along with a reconstruction of the events during the massacre itself—construction and preparatory work were carried out by a private contractor (Rozman & Leben Seljak, Reference Rozman and Leben Seljak2019; see also Rozman, Reference Rozman and Dežman2024). Vegetation around and inside the shaft (the vertical part of the cave labelled ‘cave/mass grave’ on Figure 3 and henceforth described as the pit) was first removed, followed by mechanical removal of the western part of the hill over 4–5 m, creating a larger manoeuvring area for future excavation. During this initial work, approximately 1000 m³ of rocks were removed until the first human remains appeared. In the course of excavation, it was found that the rock or debris cone, under which the human remains lay, extended deeper towards the walls of the cave, which widened into a more bell-shaped form towards the bottom. At a depth of about 10 m below today’s entrance, the first human remains were discovered in the south-western part of the pit, along with some personal items and the remnants of electrical detonators. Approximately 10 vertical metres of rocky and gravelly material were estimated to have been removed by that time.

Figure 3. Activity areas of the execution site, based on the distribution of objects and topography.

Alongside the construction work, the area around the pit was prepared for further excavations of human remains, which took place in 2022. Due to extremely challenging conditions, the cave environment, and the expected presence of unexploded ordnance, the excavation was carried out using a method that was comparable to an archaeological excavation, i.e. that stratigraphic excavation was followed whenever possible. At the top of the cave, a concrete platform was first constructed on the western side of the access slope to accommodate a 21-ton excavator with an attached cable and a 1 m³ bucket for lifting material from the cave, where a smaller 2.5-ton excavator was stationed. During preparatory work in 2019, it was found that human remains were located at multiple sites and at various depths (see below), but clear stratification or a sequence of bone deposition and rock material was not identifiable. After each phase of exposing the human remains, photogrammetric imaging of smaller spatial units was conducted, along with documentation of the situation. The records were transferred to digital space, thus allowing for additional spatial analyses to aid understanding the events of that time.

After recording individual situations, manual excavation of the human remains followed. Due to the extensive damage and intermingling of the human remains, it was not possible to identify each skeleton morphologically. On site, we set up a working space for cleaning the human remains, primarily to facilitate the work of the anthropologist analysing the remains. In addition to bones, all discovered objects were cleaned with water to help interpret and possibly identify the victims.

On the work platform outside the cave, a temporary covered and illuminated space was set up for the anthropological analysis in the field. Standard inspection of human skeletal remains and anthropometric morphological methods were used. The minimum number of skeletons, sex, age, height, and any pathological changes were determined. Right femora were stored for possible future DNA analysis, as the storage of entire right femora, and not just smaller samples, is a requirement of the Ministry of Defence that funded the research and the Commission of the Government of the Republic of Slovenia for solving the issues of concealed burial sites. Subsequently, the human remains were transported to a temporary location, waiting for a proper reburial. On 28 October 2022, at the excavation site, the fieldwork concluded with a symbolic wreath-laying ceremony for the victims and a press conference to inform the public about preliminary findings.

Results

Definition of the execution area

The execution area could primarily be reconstructed based on the natural terrain and the distribution of the objects discovered (Košir, Reference Košir2019c: 241). Among the various findings in the vicinity of the cave, seventy-one items of personal belongings and clothing accessories were discovered in 2017. Personal items included coins, fragments of spectacles, a comb, a crucifix, and a ring with initials. Additionally, uniform buttons, various buckles, and other components of military equipment were found. This could be tied to the testimonies of survivors about the beatings on the way towards the execution sites (Tolstoj et al., Reference Tolstoj, Klepec and Kovač1991). In this chaos, it can be imagined that many prisoners lost some of their items. Short fragments of thick wires were found in the area between the sinkhole and the cave, interpreted as parts of wires that broke when untying or tying the victims. Bundles of wires, around 70 cm long and prepared for use, were also discovered near the present road leading from Kočevje.

Based on the above-mentioned objects, it was possible to infer the direction from which and the route along which the victims were led to the cave (Figure 3). The presence of unused wire along the road suggests that trucks with captives stopped somewhere near the present junction towards the cave or slightly further east along the path. Approximately 70 m south-east of the cave, an area with concentrations of personal items and wires, as well as some cartridge cases, bullets, and cartridges, are thought to indicate the path leading to the cave. Given the significant quantity of finds at this location, it is likely that victims were also detained here before being brought to the cave area, where undressing and executions took place (see Figure 3). The path partially corresponds to an old path evident in the terrain and in LiDAR scanning, and the findings suggest that the shortest possible access to the cave was chosen. Remains of lime discovered in the same area indicate that it was used to cover the bodies inside the cave, which is further supported by lime residues found in the cave in 2022.

Near the cave, we found numerous cartridge cases and bullets, cartridges, cartridge clips, and parts of hand grenades. They were predominantly cartridge cases and bullets of 9 × 19 mm calibre, used for various types of pistols and submachine guns. Cartridge cases of 7.92 × 57 mm calibre for various rifles and machine guns were also present. Based on the finds of cartridge clips, it was evident that the perpetrators also used Mauser C96 pistols of 9 mm calibre. Cartridge cases were also discovered around the cave itself, on and along the path between the cave and the sinkhole (see also Košir, Reference Košir2019c: 232–38).

The cave and the mass grave

The current entrance (Figure 4) or perimeter of the cave opens at an elevation of between 614 m and 624 m asl, where the funnel-shaped part initially slopes gently, then transitions steeply into a vertical wall, measuring approximately 13 × 9 m. In determining the original size of the cave’s entrance, we partially relied on images (obtained from the National Collection of Aerial Photography in Edinburgh) from the Royal Air Force, which flew over and photographed the area in July 1944. The aerial photograph shows the cave amidst younger tree growth and shrubbery, along with the road that still exists today. The image analysis indicates that the entrance measured approximately 8–9 × 4–5 m.

Figure 4. View from the excavation site towards the entrance of the cave taken in 2022.

The north-western wall in the cave is fairly vertical and smooth, while the uneven, cone-shaped bottom, together with layers of gravel and human remains, gradually expands towards the north-eastern, south-eastern, and south-western sides. The irregularly shaped base of the cave measured approximately 108 m² at the beginning of the investigation in 2019, at an elevation of 612–607 m asl. By 2022, after the preparatory work had been completed, the area measured approximately 136 m², at an elevation between 605 m and 600 m asl.

Finding a black-coloured layer, initially observed on the steep north-western side of the cave, and later, as greater depths were reached, forming a ring-shaped layer extending in all directions within the cone, was a significant discovery. It turned out to be a humus-rich layer of leaves and branches mixed with soil that was present at the bottom of the cave at the time of the executions, roughly indicating the size of the opening of the entrance to the cave. On this layer, some of the first human remains that fell into the cave at the beginning of the massacres were recorded. The semicircular ring-shaped layer, measuring 4.5 × 9 m, was observed along the north-western wall at an elevation of 602 m asl, then continued down the cone in all directions to an elevation of approximately 598 m asl, where it measured approximately 6 × 12 m. Given the steep slope of the cave floor (with an inclination between 40° and 45°), we infer that the layer on the bottom indicates a slightly wider area, encompassing not only the original perimeter of the cave but slightly beyond. Therefore, we estimate its size to be somewhere between 35 and 40 m², which is less than half that of the current opening (Figure 4).

During the discovery and exposure of the remains, a layer of lime mixed with various objects was already visible in the initial stages of our investigations; the perpetrators are likely to have sprinkled this lime at the end of their deed to mask the smell. They also discarded several munitions, including unexploded ones, which were carefully handled by an Explosive Ordnance Disposal unit. The discovery of unexploded ordnance also corresponds to the testimonies of survivors, who mentioned blasting and the use of hand grenades during and after the killings (Tolstoj et al., Reference Tolstoj, Klepec and Kovač1991). Soon after the excavation began, we realized that all these activities had severely damaged the bodies of the deceased. Moreover, the subsequent extensive blasting in c. 1960 caused even greater destruction of the scene (Mihevc, Reference Mihevc and Dežman2021). All the skeletons within the radius of the original cave’s vertical descent were almost completely destroyed during the blasting of the cave, while those outside the descent area were much less damaged. The conical shape of the cave floor caused the bodies to move and mix with each other during their fall and decomposition, making the morphological identification and separation of individual skeletons very difficult or impossible.

The highest-lying human remains (602 m asl), mixed with gravel and rock, indicated only the peak of the victims’ cone, which in the compacted part extended down to an elevation between 594 and 595 m asl (Figure 5). At this depth, the final extent of the human remains spread in semicircular area over approximately 330 m². Outside the central area beneath the entrance, the victims were recorded furthest towards the south-west, approximately 20 m from the vertical descent, and 15 m towards the north-east and south. The area of the cave containing all human remains measured 470 m², while the entire cave, after recording, measures approximately 800 m². The cross-section of the pile of human remains, among which were also rocks that landed on the bodies due to the explosion of hand grenades, was documented over a height of 8 m. The findings suggest that the victims are likely to have been thrown into the cave from a height between 615 and 618 m asl from the northern or north-western side. We could not obtain more precise data since the blasting of the cave’s entrance changed the current entrance considerably.

Figure 5. Cross-section of the cave and the deposit of human remains.

Graphics by permission of R. Bremec.

The first victims, who were pushed into the cave, were located at the natural base of the cave at the site of the entry point and their remains extended downwards to the extreme areas of the cone’s spread. In the upper part, the victims were buried under a layer of gravel and rocks up to 0.5 m thick, which had fallen from the cave walls when the cave was blasted. In the lower part, this layer was more than 1 m thick.

In the lateral passages of the cave, we found the remains of victims who had survived the fall and attempted to find an exit there (Figure 6). They eventually died there from injuries or starvation. The survivors sought refuge in the extreme areas, passages, niches, rocky ledges, or chambers, where they were not visible from above and safe from hand grenades and gunfire. Among them, twenty-three people sought refuge in the far western ‘hall’; one was found in a niche in the north-western wall, two were discovered in a passage along the north-western side, and two behind a large rocky pillar along the north-eastern side (Figures 6 & 7). Among the survivors were possibly five people who later succumbed on the way out on a rocky overhang on the north-western side of the cave. They lay in a small ‘shelter’ on a rocky ledge just a few metres from the top of the cave. The situation we discovered may perhaps be compared to the testimony of a survivor, France Dejak, who said he escaped the cave through a rocky chute in the cave’s wall (Dejak, Reference Dejak1991). Since similar morphological features were not found elsewhere in the cave in the direction of the exit, this correlation seems quite likely. In total, at least forty-six people appear to have survived the execution and fall but later failed to escape. Despite the fact that the remains of these individuals were mostly in more remote parts of the cave that were not buried under blasted material, it was not possible to identify them individually, as flooding and animal activity displaced the skeletons substantially.

Figure 6. Plan of the cave floor and areas with human remains. The arrows point to the remains of the victims that initially survived the fall and later died in the cave’s tunnels.

Graphics by permission of R. Bremec.

Figure 7. Human remains in the south-westernmost part of the cave (A) and remains displaced by water activity and scavengers of an individual that survived the fall and sought refuge in the eastern tunnel (B).

Graphics by permission of R. Bremec.

The victims

The anthropological analysis of the human remains (Leben Seljak, Reference Leben Seljak and Dežman2024) found that there was a minimum of 3403 victims, most probably around 3450, but no more than 3500. The minimum number of individuals is based on the number of femora (left, right, and undetermined). Based on comparisons of bone preservation in the upper and lower parts of the cave, it was determined that around ten per cent of the femora may have been destroyed in the upper part of the cave by blasting (Leben Seljak, Reference Leben Seljak and Dežman2024: 142, 144). Differences in numbers are due to bone fragmentation, caused mainly by repeated blasting and rocks and boulders falling on the victims. Bone fragmentation was significantly greater at the point of entry into the cave than in the side areas. The victims were all male, although in one or two cases the possibility of females cannot be ruled out. Based on the state of ossification of the collarbones, it was evident that around 1000 males were younger than 25 years old, and the same number were older. Based on the pelvic bones, half of the victims were older than 23 years old, and fifteen per cent were younger. Of these, at least 254 were younger than 20 years old. There were no victims younger than 15 years old. Considering their tall stature, dental hygiene, and dental prosthetics, Leben Seljak (Reference Leben Seljak and Dežman2024: 150) concluded that many of the males were likely to have come from a better-off segment of the population.

The predominant injuries, especially to the occipital skull bones, were gunshot wounds but, because of the fragmentary preservation of the skulls, only 414 gunshot wounds were recorded (Figure 8). Of these, 393 were on the occipitals, clearly indicating the method of execution. There were also thirty-three gunshot wounds documented on the bones of the torso, thirty-one on the pelvis, and some on the femora and other bones. There were also noticeable injuries that occurred during life, including some that could be associated with wartime injuries such as fractures caused by gunshot or explosion. Six individuals were amputees: one had an arm amputation and five had leg amputations (Leben Seljak, Reference Leben Seljak and Dežman2024: 149).

Figure 8. Gunshot wounds and amputations. A: bullet trajectory from the back to the front of the skull; B, C: exit bullet wound on a skull; D: entry bullet wound on a femur; E: part of the exit bullet wound on a pelvis; F: bullet lodged in a vertebra; G: surgical wire, grown onto amputated bone; H: amputated femur.

The objects

The excavations yielded a large quantity of objects, which are associated with the victims of the massacre and the perpetrators (Košir, Reference Košir and Dežman2024). In general, the remains of clothing, footwear, and personal items were identified as belonging to the victims (Figure 9). Some of the personal and utilitarian items could have belonged to Yugoslav Army soldiers and were possibly lost near the edge of the cave or ended up in the cave in other ways, but, given that we cannot determine ownership, these items were categorized merely as personal items.

Figure 9. Selected objects from the cave. A: cap insignia of Slovenian Home Guard (missing a Carniola eagle); B: Slovenian pilgrimage badges; C: part of a Slovenian newspaper dated 13 May 1945; D: Italian canteen model 1935 with two-colour camouflage paint; E: gold crucifix ring; F: pair of wedding rings; G: orthodox cross; H: part of a leg prosthesis.

All remnants of ammunition and explosive materials were linked to the perpetrators of the massacres and the people involved in the blasting of the cave. Accordingly, the various objects were classified as military, civilian, or undetermined. The last category mainly includes everyday items such as mirrors, smoking accessories, personal hygiene items, coins and wallets, rosaries, other religious artefacts, and similar items that do not have either a military or civilian connotation.

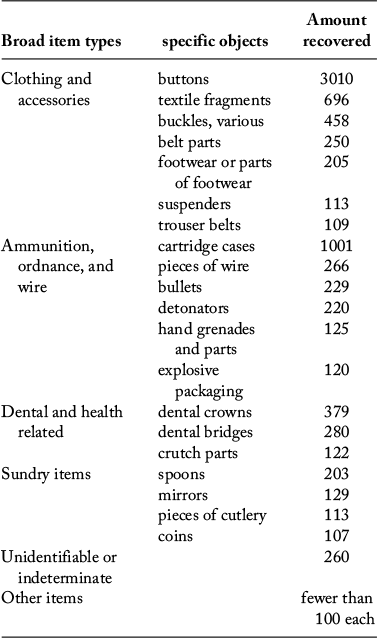

Where possible, the origin of the items was attributed, either to the country of manufacture or to the military forces that primarily used such items. It is important to emphasize that the origin in most cases does not indicate the origin of the victims, as, for example, German uniforms were used by various armed forces, including the partisan forces and later the Yugoslav Army. On the other hand, certain military insignia or other items can be associated with specific armed units, allowing us to identify more precisely the origin of some victims. However, items that had a narrow range of use, especially that came from outside the country of origin, are the most helpful for identifying the origin of the victims. For example, pilgrimage badges with Slovenian inscriptions and other objects related to Slovenian religious centres such as the Basilica of St Mary Help of Christians in Brezje were probably rarely worn by foreigners, although that possibility exists in individual cases. Almost a third of the items (3037 pieces, thirty per cent) could be attributed to a specific origin, while seventy per cent (7247 pieces) remained without a determined origin; the percentage of items with a specific origin may be higher if all cartridge cases were professionally cleaned to decipher head stamps but this was beyond the scope of our research. Some items could easily be attributed to a specific origin, while the origin of others is questionable or presumed. Among the finds (Table 1), those from Germany predominate (2016 pieces, seventy per cent), followed by Italian, British, Yugoslav, and Slovenian objects. Serbian, Croatian Austro-Hungarian, French Soviet, Hungarian, and American items each account for less than one per cent, and single finds can be attributed to other locations. In total, 10,284 items were discovered and documented (for a selection, see Figure 9). Among them were 316 unexploded ordnance items, which were removed and destroyed by an Explosive Ordnance Disposal unit. Dental crowns and bridges that fell out of jawbones were also counted among the objects but those still attached to the human remains were left in position, waiting for reburial. Among the items recovered (Table 2), the objects range from buttons (3010 pieces), followed by cartridge cases (1001 pieces) down to coins (107 pieces). Unidentifiable or indeterminate pieces numbered 260, and other categories were represented by fewer than 100 pieces each.

Table 1. Origin of items recovered at the cave under Macesnova gorica.

Table 2. Summary of items recovered at the cave under Macesnova gorica.

Concealment of the Crime

The witness testimonies and the archaeological evidence relating to human remains, personal objects, post-Second World War objects, gunshot wounds to the back of the heads of the victims, and wires associated with ligatures of the victims, and indicate that we are dealing with a mass execution, committed after the end of the Second World War. As the victims were POWs, it is clear that the Hague Conventions of 1899 and 1907 were violated. The killings can be seen as a crime against humanity or a war crime. Crimes against humanity consist of physical, contextual, and mental elements and they must involve large-scale violence in terms of the number of victims, a large geographical area where the violence is conducted, or the systematic nature of the violence (UNOGPRP, Crimes against humanity, n.d.). As shown by historical and archaeological evidence, the cave under Macesnova gorica is undoubtedly a site where such a crime was committed.

After the massacre, efforts were made to conceal this crime. This is indicated by burnt and charred items belonging to the victims, which were discovered in a nearby sinkhole, as well as equipment, primarily mess tins, canteens, and eating utensils, which were discarded into the cave after the executions. Numerous remains are also associated with explosive charges, which are likely to have been used to blast the cave’s entrance. A total of 120 pieces of tin packaging of British origin were found (the actual fragments were much more numerous), which contained gun cotton. Additionally, forty-eight intact explosive charges were discovered and removed by an Explosive Ordnance Disposal unit. Among other items related to explosive materials, there were also nine pieces of fuse cord, sixteen pieces of detonating cord, three wooden reels for detonating cord or fuse cord, 218 electrical detonators, two Italian mortar rounds mod. 35 Brixia, nine 47 mm artillery shells, various igniters, detonators, and explosive charges.

Moreover, the blasting of the cave continued as late as around 1960 (Mihevc, Reference Mihevc and Dežman2021), indicating that the need to conceal the crime persisted for a considerable period into the post-war era. Our data show that the cave was filled with approximately 1800 m³ of rock, which was excavated in 2022, along with an additional 1000 m³ removed as part of preparatory construction work in 2019.

Discussion

The objects from the excavations in 2022 of the cave under Macesnova gorica can, at least in part, outline the events of June 1945 and later. About eighty per cent of the finds can be linked to the victims, indicating their affiliation with various armed formations, partially also reflecting their nationality. The remaining twenty per cent of items are associated with the perpetrators of the massacre and the process of killing and blasting the cave to conceal the crime. In relation to the victims’ belongings, let us note that, according to testimonies (see Žajdela, Reference Žajdela1990; Tolstoj et al., Reference Tolstoj, Klepec and Kovač1991), their equipment was already confiscated in Kočevje or elsewhere, and that they were stripped naked or in their underwear at the edge of the cave before being shot and their bodies fell into the grave. Nevertheless, the studies of the nearby sinkhole in 2004 and 2017 (Ferenc, Reference Ferenc, Ferenc and Petkovšek2006; Košir, Reference Košir and Dežman2019a) revealed that many prisoners still had small personal and utility items with them, and stripping and confiscating items did occur to some extent at the edge of the cave before execution. This is evidenced by numerous objects found in the sinkhole, some partially damaged by fire, indicating that clothes and other items were burnt (Košir, Reference Košir and Dežman2019a: 514). In some cases, larger pieces of equipment in the pit, such as canteens and mess tins, can be interpreted as having been thrown into the pit during cleanup after the massacre, as a significant portion of such items was recovered in the upper layers of the cave’s fill. Based on the number and type of items, it can be argued that some individuals were likely to have been stripped down to their underwear, while others were in uniform, while still having some personal and utility items, and other pieces of military equipment. Certainly, some individuals were also bound with wire.

The execution was mostly carried out using weapons chambered in 9 × 19 mm calibre ammunition, either semi-automatic or automatic to a lesser extent. The discovery of magazines for German submachine guns models MP38, MP40, or MP41 suggests that automatic weapons were used, while numerous stripper clips for Mauser C96 pistols in 9 mm calibre indicate that such pistols were employed, as were numerous pistols with 9×19 mm calibre ammunition. In the cave, Italian ammunition and cartridge cases for the 10.35 × 23 mm calibre Bodeo mod. 1889 revolver were also discovered. On the other hand, rifles chambered in 7.92 × 57 mm calibre were used to a lesser extent. Individual stripper clips for five rounds suggest that rifles of Mauser system were employed. Some cartridge cases of calibre 7.62 × 25 mm or 7.63 × 25 mm were also found but, due to poor preservation, they could not be distinguished from each other. If they were of 7.62 × 25 mm calibre, it indicates the use of a Soviet TT30 or TT33 pistol, or less probably one of the Soviet submachine guns of the same calibre. If they were of 7.63 × 25mm calibre, it would indicate the use of a Mauser C96 pistol in this calibre. Remnants of British .303 calibre ammunition show that British rifles or machine guns were used. Italian Carcano rifles chambered in 6.5 mm calibre were used least, represented by only six cases of this calibre. Among pistol ammunition, there were also two cases of 7.65 × 17 mm calibre, which were used by various pistols of that time. The diversity of the ammunition components recovered indicates that different weapons were used and suggests that multiple shooters were involved in the massacre.

The survivors among the Home Guard members mention that Yugoslavian Army soldiers threw hand grenades into the cave during the massacre to kill the wounded victims (Žajdela, Reference Žajdela1990: 54). This is supported by numerous remnants of exploded and unexploded hand grenades. Among the findings, a drill for drilling holes in rock for the purpose of blasting also stands out. Among the finds, the fragments of newspapers that could be dated show that the massacre took place after the end of the Second World War.

In contrast to the items belonging to the perpetrators, which are known to have been members of the Yugoslav Army, the items belonging to the victims suggest their affiliation with various armed forces. Yet, among the 8254 items recovered, only a few definitively indicate the affiliation of individual victims. Based on Slovenian religious artefacts and Slovenian Home Guard insignia, we can confidently assert that Slovenians and members of the Slovenian Home Guard were among the victims. Slovenian names and surnames on some items also suggest Slovenian victims. Among the victims, there were certainly at least seven members of the German armed forces, as evidenced by their identification tags. Despite being soldiers of the German Army, these individuals could have been Slovenian or of any other nationality. The presence of buttons with the inscription NDH (Nezavisna država Hrvatska or Independent State of Croatia), suggests the possible presence of a small number of Croatian victims.

More precise conclusions based on the items are currently not possible. In most cases, the victims were dressed in German uniforms, but this is not a precise indicator of the victims’ affiliation, as various armed forces wore such uniforms. However, the mixture of German and Italian clothing along with German and Italian military equipment suggests that the victims included indeed members of the Slovenian Home Guard, as well as some individuals from other armed formations.

An important portion of the objects retrieved were personalized, as soldiers often marked their equipment, such as canteens, mess tins, and utensils, with their initials, various symbols, patterns, or even full names. Such inscriptions were either engraved or stamped into the surface of aluminium items or scratched into the paint of military gear. Full names or surnames are rare, as abbreviations predominate. Given the extremely large number of victims and extensive lists of the deceased, it is impossible to identify the owners from abbreviations alone. In rare cases, however, surnames and names allow us to identify the former owners of some items with a high degree of certainty. An item with the name and surname of a former owner does not, however, necessarily mean that this person is among the victims. Objects could have been used secondarily by other individuals who, for various reasons, may have had and used items belonging to others. Among the items with inscriptions, a German canteen stands out, bearing the surname ŠEGA. In the list of prisoners of the Šentvid concentration camp, only one person with such a surname exists. Zvonimir Šega, a Home Guard soldier from the village of Goriča was born on 20 December 1925, died in the Kočevski Rog, according to the records of Second World War victims. On one of the German mess tins, the name JANEZ ZUPAN is engraved, but this name cannot be found in the list of prisoners from the Šentvid camp. In the records of Second World War victims, several individuals with this name who died in June 1945 can be found, making it impossible to determine to which Zupan it refers. The same uncertainty applies to Janez Hrovat, who signed the lid of a German mess tin and scratched the image of a cross alongside his name. This inscription might refer to either Janez Hrovat, a Home Guard soldier from Kal born in 1912, or Janez Hrovat from Brezov Dol, born in 1902. The owner of the lid of the German mess tin, engraved with LAVRIČ D, is more clearly identifiable, as the list of prisoners in Šentvid and the records of Second World War victims mentions Dominik Lavrič, from Šmihel pri Žužemberku, born on 4 December 1926, and whose place of death is listed as Kočevski Rog. Another possible (but less likely) candidate, not found on the Šentvid prisoner list, is Danijel Lavrič from Gabrje, who died in June 1945, but the place of death is not recorded (Košir, Reference Košir and Dežman2024: 248).

Among the fully inscribed names is KARL KLOIMSTEIN, engraved on one of the mirrors. A person with this name could not be found on any lists or in the search engine for fallen German soldiers. Further research would also be necessary to ascertain the affiliation of the pair of wedding rings with the inscriptions ‘Katica 9. VIII. 1940’ and ‘Miro 9. VIII. 1940’. Based on the records and the appropriate age for marriage in 1940, it might refer to Miroslav Kljun or Miroslav Seibitz, as both were married. The latter is listed as having died on 25 July 1945 in Podutik, or disappeared there (Košir, Reference Košir and Dežman2024: 248; for more about the cave under Macesnova gorica, see Dežman, Reference Dežman2024).

Conclusion

The investigation of the execution site and mass grave in the cave under Macesnova gorica represents just one of numerous excavations of wartime and post-war mass graves in Slovenia that have been conducted over the past two decades. Nevertheless, it stands as the most extensive exhumation of post-Second World War execution victims to date (i.e. 2025). Archaeological data obtained through various research methods, from metal detector surveys and excavations of discarded items to archaeological excavations within the cave itself, have yielded significant results. These findings shed light on the poorly understood, and sometimes completely unknown, aspects of such a difficult heritage in Slovenia.

Given the scope of the work, the extremely difficult working conditions, and the exceptionally large number of human remains discovered, it is imperative that information about such investigations be disseminated beyond Slovenia. Regardless of the political connotations associated with such research, archaeological work is an important endeavour that contributes to a more respectful treatment of the victims of modern conflicts, bringing insights into their fate, origins, and even potential personal identification. In some cases, it also contributes to ensuring proper burial for all victims, irrespective of their religious, political, or other beliefs.

AcknowledgementS

The excavation of the gravesite was funded by the War Veterans and Military Heritage Directorate at the Ministry of Defence.